Abstract

Heartburn and acid regurgitation are the typical symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux. Despite the availability of several treatment options, antacids remain the mainstay treatment for gastroesophageal reflux-related symptoms based on their efficacy, safety, and over-the-counter availability. Antacids are generally recommended for adults and children at least 12 years old, and the FDA recommends antacids as the first-line treatment for heartburn in pregnancy. This narrative review summarizes the mechanism, features, and limitations related to different antacid ingredients and techniques available to study the acid neutralization and buffering capacity of antacid formulations. Using supporting clinical evidence for different antacid ingredients, it also discusses the importance of antacids as OTC medicines and first-line therapies for heartburn, particularly in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic, in which reliance on self-care has increased. The review will also assist pharmacists and other healthcare professionals in helping individuals with heartburn to make informed self-care decisions and educating them to ensure that antacids are used in an optimal, safe, and effective manner.

Keywords: Antacid, heartburn, acid regurgitation, gastrointestinal reflux disease, acid-neutralizing technique, self-care

Introduction

Heartburn is an uncomfortable, burning feeling in the chest, behind the breastbone, or in the upper part of the abdomen that sometimes spreads to the throat. 1 It is specifically related to the reflux of gastric acid through the lower esophageal sphincter, which is a typical symptom of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Some patients with GERD might also present with atypical symptoms (e.g., epigastric fullness/pressure/pain, dyspepsia, nausea, bloating, belching) and extra-esophageal symptoms (chronic cough, bronchospasm, wheezing, hoarseness, sore throat, asthma, laryngitis, dental erosions). GERD has been classified into three stages based on the frequency of symptoms: stage I (≤3 episodes per week), stage II (>3 times per week), and stage III (daily symptoms). Symptoms are more commonly observed after meals, and they worsen in recumbent positions.

Antacids comprise a major class of over-the-counter (OTC) medicines sold globally, and consumers with acid indigestion and heartburn spend billions of dollars on these non-prescription medications in search of relief. 2 Antacids provide symptomatic relief from heartburn, hyperacidity, acid indigestion, GERD and upset stomach associated with these conditions. 3 Antacids act by neutralizing excess hydrochloric acid (HCl) in gastric juice and inhibit the proteolytic enzyme pepsin. 4 An antacid that increases gastric pH from 1.5 to 3.5 can reduce the concentration of gastric acid by 100-fold. 5 A few studies reported that some antacids can be safely used during pregnancy owing to their local action rather than systemic effects.6,7

The effectiveness of each antacid depends on its neutralizing and buffering capacity. Manufacturers of antacids often reformulate some products to improve their palatability and organoleptic properties for a better consumer experience. Thus, several antacid products are available in the market, each claiming a relative advantage over one another, baffling physicians and the public with choices. The decision to select an antacid can be made according to the acid-neutralizing capacity (ANC), which can differ significantly, but it is unfortunately not stated on product labels. 8 An antacid can also be selected by considering its buffering capacity to maintain gastric pH above 3.5 for a considerable duration. This narrative review provides background and context for the current understanding of antacids and their roles in treating heartburn, practical considerations for clinical practice as well as techniques available to study the ANC and buffering capacity of antacid formulations, and the benefits and drawbacks of methods used. This narrative will also assist pharmacists and other healthcare professionals in helping individuals with heartburn make informed self-care decisions as well as educating them to ensure that antacids are used in an optimal, safe, and effective manner, particularly in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic, in which reliance on self-care has increased.

Materials and methods

The databases Medline, Embase, and Google Scholar were searched for relevant studies using combinations of the following basic and Medical Subject Headings terms: “antacid,” “sodium bicarbonate,” “calcium carbonate,’ “magnesium carbonate,” “magnesium hydroxide,” “aluminum hydroxide,” “acid-neutralizing capacity,” “heartburn,” “gastroesophageal reflux disease,” “GERD,” and “gastric acidity.”

Epidemiology of GERD

In 2020, a meta-analysis of 96 studies from 37 countries reported the global pooled prevalence of GERD as 13.98%, with significant differences identified between regions and countries. In Asia, the estimated rate was 12.92%, versus 19.55% in North America and 14.12% in Europe. 9 Similarly, a previous study also estimated lower prevalence rates of GERD in Asia than in Western countries (10% vs. 14.1%–21.3%). 10 On the contrary, the actual prevalence of GERD in Asia is much higher and similar to that reported in Western countries, but is difficult to determine because of the lack of an exact word for heartburn in some Asian languages, the potential for patient self-treatment, and variation in diagnostic practices and definitions for heartburn and GERD. 11 For instance, the experience, understanding, and reporting of heartburn varied significantly among racial groups. The prevalence of heartburn was higher among African Americans (46.1%) and Caucasians (34.6%) but exceedingly low among East Asians (2.6%). 12 In addition, a group of experts who participated in a Delphi-based study on the management of GERD in the Asia–Pacific region reached a consensus that the prevalence rates of GERD in Asia are increasing. 13

From 2006 to 2016, there has been a significant increase in the proportion of younger patients with GERD, especially within the age range of 30 to 39 years (15–19, 0.2%; 20–29, 2.4%; 30–39, 3.2%; 40–49, 2.8%; 50–59, 2.5%; 60–69, 0.8%, all P < 0.001). 14 Rising obesity and unhealthy dietary patterns might be some of the reasons behind this increased prevalence of GERD in the younger population. 15

It has been estimated that at least weekly symptoms of GERD are most commonly observed among residents of North America (19.8%), followed by residents of Europe (15.2%), the Middle East (14.4%), and East Asia (5.2%). 16 In Australia, approximately 11.3% of the population has chronic GERD. 17 Some studies indicated that GERD symptoms are more prevalent in men than in women; however, evidence is conflicting, and the predominance in men cannot be reliably determined using current data. Nevertheless, complications from GERD do appear to be more prevalent in men. 16

Impact of COVID-19 lockdown periods on gastrointestinal symptoms

Lockdowns have brought significant lifestyle changes. Sedentary lifestyles, remote working, boredom, and anxiety evoked by COVID-19 lockdowns have a direct effect on individuals’ eating behaviors. Significant (P < 0.001) increases in meals consumed, binge eating, snacking, and unhealthy food consumption have been observed during COVID-19-related home confinement. 18 An Italian Internet-based survey among medical students analyzing gastrointestinal symptoms before and during the COVID-19 lockdown period reported an increased prevalence of heartburn (P < 0.001) and indigestion symptoms (P < 0.001) during the lockdown period because of changed dietary habits and anxiety symptoms. 19 Similarly, a cross-sectional survey comparing the prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms in the Bulgarian adult population before and during the COVID-19 lockdown period reported increased rates of overall gastrointestinal symptoms (68.9% vs. 56.0%, P < 0.001), functional dyspepsia (18.3% vs. 12.7%, P < 0.001), and heartburn (31.7% vs. 26.2%, P = 0.002). 20

Frequently used terms for heartburn

Heartburn is a commonly used but frequently misunderstood word. There is no direct translation for the word heartburn in most languages. It is likely that some meaning may be lost in translation such that the word-for-word translation may carry a completely different meaning. The lack of an exact word for heartburn might contribute to low symptom reporting and a consequently low rate of diagnosis.21,22

Heartburn is often associated with a sour taste in the back of the mouth with or without regurgitation of the refluxate. Heartburn has many synonyms, including “acid indigestion,” “acid regurgitation,” “sour stomach,” “hyperacidity,” and simply “acidity.” Heartburn is usually described as burning discomfort experienced behind the breastbone. Patients describe heartburn as a “burning sensation in esophagus, stomach, throat, trachea,” “a burning feeling rising from the stomach or lower chest up towards the neck,” “a burning, warm or acid sensation in the epigastrium, substernal area, or both,” “a burning feeling in epigastrium rises through the chest in substernal area,” or simply “a feeling of fullness or discomfort in epigastrium”.22 –26 In 2018, Clarrett and Hachem defined heartburn as a burning sensation in the chest that radiates toward the mouth because of acid reflux into the esophagus. 27 The terms “burning,” “hot,” and “acidic” are typically used by patients unless the symptoms become so intense that pain is experienced. 28

Antacids as a mainstay intervention for reflux symptoms

Acid suppression is the backbone for treating heartburn and other reflux symptoms. The World Gastroenterology Organization developed guidelines for the community-based management of common gastrointestinal symptoms recommending antacids, alginates, and histamine H2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) as appropriate OTC treatment options for infrequent, mild, or moderate symptoms of heartburn. 29 Antacids provide rapid, but temporary and short-term relief of heartburn. Currently, antacid therapy is recommended for mild gastroesophageal reflux symptoms, whereas proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) is recommended for severe symptoms. 30 A position statement from the Indian Society of Gastroenterology on GERD management in adults also recommended PPIs in patients with frequent or severe symptoms. 31 Clinical studies demonstrated that antacid formulations containing sodium bicarbonate, calcium carbonate, aluminum hydroxide, or magnesium hydroxide/carbonate provide significant symptomatic relief against heartburn (Table 1).

Table 1.

Design, intervention (antacid salts), and findings of studies conducted among patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease-related conditions.

| Authors | Study design | Intervention (s) | Treatment protocol | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Johnson and Suralik, 2009 51 | Randomized, open-label, crossover study | One dose (powder form) of a sodium bicarbonate (2.32 g) and citric acid (2.18 g) combination dissolved in water versus water alone | – Interventions were provided at visit 2 or alternatively at visit 3 before breakfast– Doses was separated by a washout period of 36 to 48 hours | – Treatment with a sodium bicarbonate and citric acid combination resulted in a statistically significant change in pH from baseline in 6 seconds, compared with 18 seconds for water. |

| Walker et al., 2015 77 | Phase III, randomized study | Immediate-release omeprazole plus sodium bicarbonate (one dose [20 mg] per day) versus standard enteric coated omeprazole (one dose [20 mg] per day) | – When required, interventions were provided for a period of 3 days during the 14-day study period | – Immediate-release omeprazole plus sodium bicarbonate provided significant relief of heartburn associated with GERD within 0 to 30 minutes. |

| Orbelo et al., 2015 78 | Open-label, prospective, randomized clinical trial | One sachet in 15 to 30 mL of water per day of an omeprazole and sodium bicarbonate combination | – The intervention was provided daily for eight weeks either • in the morning, i.e., 20 to 60 minutes prior to a meal or • at night, i.e., immediately prior to sleep | – The once-daily dose, taken in the morning or at night, effectively reversed severe reflux esophagitis and improved GERD symptoms. |

| Higuera-de-la-Tijera, 2018 79 | Systematic review of studies published since 2000 | Omeprazole and sodium bicarbonate combination versus omeprazole | NRa | – The combination produced a sustained response and sustained total relief in patients with GERD. |

| Sulz et al., 2007 80 | Open, randomized, placebo-controlled trial | Two tablets of a calcium carbonate (680 mg) and magnesium carbonate (80 mg) combination versus magaldrate gel (800 mg) versus placebo | – Interventions were provided after an overnight fast of at least 10 hours on 3 different days– The scheduled days were separated by a washout period of 4 days | – Both the antacid tablet and gel achieved the target pH (>3.0) during the first 30 minutes. |

| Collings et al., 2002 81 | Single-blind, four-treatment cross-over study | Two pellets of calcium carbonate chewing gum (300 mg and 450 mg) versus two chewable tablets of calcium carbonate (500 mg) versus a swallowed placebo capsule | – Interventions were provided 30 minutes after a meal in all four sessions | – Both gums decreased heartburn for 120 minutes compared with placebo.– The higher gum dose decreased heartburn more strongly than chewable antacids up to 120 minutes.– Antacid gums provided faster and more prolonged symptom relief and pH control than chewable antacids. |

| Rodriguez-Stanley et al., 2004 82 | Prospective clinical study | Two chewable tablets of calcium carbonate (1500 mg each) | NAb | – Calcium carbonate improved the motor function of the esophagus in patients with heartburn, thereby improving acid clearance from the esophagus and into the stomach. |

| Robinson et al., 2001 83 | Randomized, four-way crossover study | Ranitidine (75 mg) versus a chewable calcium carbonate (420 mg), ranitidine, and calcium carbonate combination versus placebo | – Interventions were provided 1 hour after a meal– Subjects underwent a 7- to 10-day washout period between each treatment | – The combination was more effective in reducing meal-induced gastric and esophageal acidity as well as heartburn severity. |

| Ohning et al., 2000 84 | Open, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, four-treatment cross-over study | Famotidine (10 mg), calcium carbonate (800 mg), and magnesium hydroxide (165 mg) combination versus ranitidine (75 mg), calcium carbonate (1000 mg) versus placebo | – Subjects consumed a peptone meal both 60 and 15 minutes prior to treatment, and then 2.5 and 6 hours after treatment | – The combination provided superior control of gastric acidity than either antacids or histamine-type-2 receptor antagonists alone. |

| Walsh et al., 2000 85 | Open (observer-blinded), randomized, placebo-controlled four-period crossover design | Famotidine (10 mg), calcium carbonate (800 mg), and magnesium hydroxide (165 mg) combination versus ranitidine (75 mg) and calcium carbonate (1000 mg) combination versus placebo | – Subjects consumed peptone meal both 60 and 15 minutes prior to treatment and then 2.5 and 6 hours after treatment | – The combination reduced gastric acidity more quickly than ranitidine and continued to control gastric acidity for a longer period than calcium carbonate. |

| Robinson et al., 2002 86 | Randomized, crossover, placebo-controlled study | Chewable (750, 1500, or 3000 mg) calcium carbonate tablets versus swallowable (750, 1500, or 3000 mg) calcium carbonate tablets versus placebo | – Interventions were provided 60 minutes after dinner– The study period was separated by washout period of at least 24 hours | – The onset of action on esophageal pH was similar for all antacids (30–35 minutes). – Chewable tablets and effervescent bicarbonate had relatively long durations of action (esophagus, 40–45 min; stomach, 100–180 min); conversely, swallowable tablets had little effect. |

| Feldman, 1996 87 | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial | Two calcium carbonate antacid tablets (1000 mg) versus one famotidine tablet (10 mg) | – Interventions were provided 60 minutes after the test meal– Two identical meals were consumed 2.5 and 6.0 hours after the medication was given | – The onset of action of calcium carbonate was 30 minutes, versus 90 minutes for famotidine. – The duration of action of calcium carbonate was 60 minutes, versus 540 minutes for famotidine. |

| Netzer et al., 1998 88 | Double-blind, placebo-controlled, four-way crossover study | Two tablets of a calcium carbonate (680 mg) and magnesium carbonate (80 mg) combination versus one tablet of ranitidine (75 mg) versus one tablet of famotidine (10 mg) versus placebo | – Interventions were provided after an overnight fast | – The onset of action, for raising pH to >3 was 5.8 minutes for calcium–magnesium carbonate, 64.9 minutes for ranitidine, 70.1 minutes for famotidine, and 240.0 minutes for placebo.– The percentage of time with pH >3.0 was 10.4% for calcium–magnesium carbonate, 61.4% for ranitidine, 56.6% for famotidine, and 1.4% for placebo. |

| Levine et al., 2004 89 | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel group study | Famotidine (10 mg), calcium carbonate (800 mg), and magnesium hydroxide (165 mg) combination (FACT) versus famotidine (10 mg; FAM) versus calcium carbonate (800 mg) and magnesium hydroxide (165 mg) combination versus placebo | NAb | – Onset of symptom relief was significantly faster with FACT than with FAM (P = 0.001) or placebo (P < 0.001).– Patients with heartburn who received FACT were 1.60- and 2.15-fold more likely to maintain adequate relief at a later time point than those on antacid and placebo, respectively.– The duration of the effect was significantly longer with FACT than with antacid or placebo (P < 0.001).– The proportion of episodes relieved for at least 7 hours was greater with FACT (70.0%) than with antacid (58.5%) or placebo (51.4%). |

| Decktor et al., 1995 90 | Single-blind, three-way crossover design | Two chewable tablets of an aluminum hydroxide (800 mg), magnesium hydroxide (800 mg), and simethicone (80 mg) combination (AMH) versus calcium carbonate (1.5 g) | – Interventions were provided 60 minutes after dinner | – The onset of action was faster with AMH tablets than with calcium carbonate tablets.– The duration of the antacid action of AMH in the esophagus was 82 minutes, versus 60 minutes for calcium carbonate (P < 0.05).– In the stomach, AMH tablets raised gastric pH significantly compared with placebo (with a duration of action of 26 minutes), but the same was not observed for calcium carbonate. |

| Parente et al., 1995 91 | Double-blind randomized, multicenter study | Aluminum phosphate gel (11 g) five times a day versus ranitidine (300 mg) once daily | – Interventions were provided for 6 weeks | – Ranitidine proved more effective than aluminum phosphate in reducing the frequency and severity of daytime pain attributable to duodenal ulcer. |

| Weberg and Berstad, 1989 92 | Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled,crossover trial | One chewable antacid tablet (containing 1100 mg of aluminum hydroxide and magnesium carbonate in a co-dried gel) versus a matching placebo | – Interventions were provided four times daily– One tablet each was received 60 minutes after the three main meals and one was given at bedtime.– After 2 weeks of treatment, the patients were switched over to the alternative treatment for another 2 weeks– Treatment periods were not separated by any ‘washout interval’ | – Antacid treatment provided significant lower global symptomatic scores, less acid regurgitation, and fewer days and nights with heartburn. |

| Farup et al., 1990 93 | Double-blind randomized, placebo-controlled,multicenter study | One chewable antacid tablet (containing 1100 mg of aluminum hydroxide and magnesium carbonate in a co-dried gel) four times daily versus one cimetidine (400 mg) tablet twice daily versus a matching placebo | – One antacid tablet each was received 60 min after the three main meals and one was given at bedtime for 8 weeks | – Both antacids and cimetidine significantly reduced symptoms associated with reflux esophagitis compared with placebo. – During the first and second halves of the study, antacid consumption significantly improved the global assessment score versus cimetidine. |

| Graham and Patterson, 1983 94 | Double-blind, parallel-treatment study | 15-mL doses of aluminum hydroxide and magnesium hydroxide combined liquid antacid versus an identical appearing placebo | – Interventions were provided seven times daily, i.e., 1 and 3 hours after each meal (three in total) and at bedtime for five weeks | – Both the antacid and placebo significantly reduced the severity and frequency of heartburn. – The time to reproduce heartburn was increased by both antacid and placebo therapy. |

| Meteerattanapipat and Phupong, 2017 95 | Randomized double-blind controlled trial | 10 mL of alginate-based reflux suppressant (500 mg of sodium alginate, 267 mg of sodium bicarbonate, and 160 mg of calcium carbonate) versus 5 mL of magnesium-aluminum antacid gel (120 mg of magnesium hydroxide and 220 mg of aluminum hydroxide) | – Interventions were provided three times after a meal and before bedtime for 2 weeks | – No difference in the improvement of heartburn frequency, 50% reduction of the frequency of heartburn, improvement of heartburn intensity, and 50% reduction of heartburn intensity during pregnancy. |

aNot relevant because the article was a systematic review of different clinical studies.

bThe data were not available in the published article.

Antacids alone or in combination with PPIs/H2RAs have displayed superiority over placebo/active comparator in various randomized control trials of the treatment of hyperacidity/acid indigestion or GERD-related heartburn and upset stomach (Table 1). However, a discussion on PPIs and H2RAs will not be within the scope of this review article. In addition, a 2009 US community-based survey found that of 42.1% of patients with GERD symptoms who supplemented their PPI treatment with other GERD-related medications, 95.1% used OTC medications. 32 Among OTC medicine users, antacids were the most commonly chosen treatments (84.7% of patients). Antacids are generally considered to have a good safety profile, but high doses and chronic consumption can cause acid rebound through either gastrin release or the direct effect of antacids on parietal cells. 33

Criteria for calling any product an ‘antacid’

Antacids are compared quantitatively in terms of ANC, defined as the number of milliequivalents (mEq) of HCl required to maintain 1 mL of an antacid suspension at pH 3 for 2 h in vitro. According to the FDA, the active antacid ingredient(s) must contribute 25% of the total ANC of the product, and the finished product must contain at least 5 mEq of ANC as measured by the procedure provided in the United States Pharmacopeia 23/National Formulary 18. 34

Impact of heartburn on quality of life and the relevance of antacids in self-care

According to the Genval workshop report, a negative impact on health-related well-being is a criterion for reflux disease when heartburn occurs 2 or more days a week. 35 Studies revealed a significant decrease in well-being with increases in the symptom frequency of heartburn.36 –38 Patients with heartburn had work-related interferences, eating or drinking problems, sleep interruption, and severely impaired daily activity. 39 Nocturnal heartburn, found in 54 ± 22% of patients with GERD, can lead to poor sleep quality followed by sleep arousal, daytime fatigue, and impaired work productivity. 40 Treatment of heartburn symptoms has been significantly associated with improvement in quality of life.41,42 Based on this finding, the World Gastroenterology Organization suggests that the primary goals for self-treating frequent heartburn are the complete symptomatic relief and restoration of quality of life. 29 The reduction of heartburn symptoms is significantly associated with improved quality of life, with the greatest impact on psychological well-being and physical functioning. 41 The use of antacids alone or in combination with other therapies has produced improvements in vitality, physical and social function, and emotional well-being in patients with heartburn.43 –45 Thus, appropriate antacid use can improve health-related quality of life by ameliorating gastroesophageal reflux symptoms.

The World Health Organization defines self-care as “the ability of individuals, families and communities to promote health, prevent disease, maintain health, and to cope with illness and disability with or without the support of a healthcare provider,” which includes non-drug self-treatment and self-medication.46,47 Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, self-care and self-management are even more critical aspects of the evolving healthcare system to manage self-recognized minor ailments such as heartburn and acid regurgitation. The demand for antacids and various OTC medicines has increased because these treatments have proven appropriate for addressing the unmet needs of consumers. 48

This adds to the importance of optimal interfacing between health systems and sites of healthcare delivery. Pharmacists play a vital role in assisting patients to choose self-care approaches and select optimal OTC medicines. Pharmacists can advise consumers on the safe and effective use of antacids, reinforce directions provided by the product labeling, help cease inappropriate use of antacids, and address their interactions with other medications.

Practical considerations in the use of antacids

The following factors must be considered by healthcare professionals when prescribing/suggesting an antacid:

Pros and cons of various antacids ingredients

Supporting body of evidence

Impact in special populations

Comorbidities and concomitant medications

ANC

Buffering capacity

Risk of rebound acidity

Antacid ingredients: mechanisms to clinical evidence

Antacid products come in powder, tablets, or liquids dosage forms. Antacids contain salts of magnesium, aluminum, calcium, sodium, carbon, or bismuth in their formulations. The combination of two salts, such as magnesium and aluminum, form the principal composition of most antacids. 49 With normally prescribed doses, antacids raise gastric pH significantly; however, the onset of action depends on the dose, dosage forms, and extent of chewing (for tablets). For example, powder forms of antacids exhibit a faster onset of action than liquid forms. 50 Effervescent powder forms of sodium bicarbonate antacids can start neutralizing acid in a few seconds. 51 Antacids have a duration of action of 20 to 60 minutes when ingested on an empty stomach. After a meal, approximately 45 mEq/hour HCl is secreted. A single dose of 156 mEq of antacid given 1 hour after a meal neutralizes the acid for up to 2 hours. 52 The ANC of different formulations of antacids is highly variable. Powder and liquid preparations of antacids usually have higher ANCs than tablets. 53

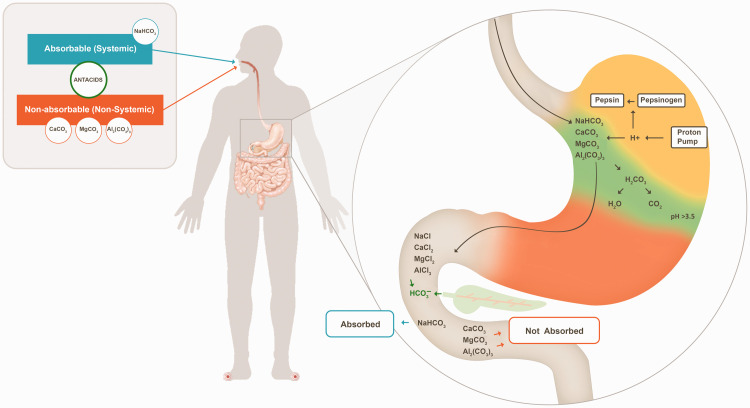

Antacids have been classified into two classes: systemic or absorbable and non-systemic or non-absorbable antacids. Absorbable antacids are readily absorbed into the systemic circulation, and they can produce systemic electrolytic alterations as well as alkalosis (e.g., sodium bicarbonate). Non-absorbable antacids such as aluminum hydroxide, aluminum phosphate, calcium carbonate, and magnesium hydroxide are not absorbed to a significant extent; e.g., only 15% to 30% of calcium and 5% to 10% of magnesium are absorbed from their respective antacid formulations.54 –56

Each antacid ingredient has a unique mechanism with the ultimate goal of acid neutralization (Figure 1). Ingredients with different features and limitations provide options to physicians for addressing the intra- and intersubject variability of patients. The features and limitations of various antacid ingredients are presented in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Effects of different antacid ingredients on gastric acid. The representative figure presents the mechanism of carbonate salts only. Other antacid salts were discussed in the article. Most of the gastric acid (approximately 45 mEq/h) is secreted across the apical membrane of the stomach through a proton pump (H+/K+ ATPase) after meal consumption. The carbonate salt of antacids binds to H+ ions from gastric hydrochloric acid to produce chloride salts (calcium chloride, sodium chloride, magnesium chloride, and aluminum chloride), carbon dioxide, and water. This decreases H+ concentrations in the stomach, thus raising the pH. The orange region denotes the acidic environment of the stomach, the green region denotes the antacid-mediated neutralization/adsorption of gastric acid, and the yellow region denotes alkalized/neutralized gastric acid. In the alkaline conditions of the small intestine, soluble calcium chloride, sodium chloride, magnesium chloride, and aluminum chloride are converted back to their carbonate salts. The sodium bicarbonate rapidly empties into the small intestine, where it is absorbed; thus, it is considered an absorbable antacid. Calcium carbonate, magnesium carbonate, and aluminum carbonate are excreted with the stool, decreasing their absorption; thus, they are considered non-absorbable antacids.

Table 2.

Features and limitations of different types of antacid salts.

| Saltsa |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium | Sodium | Magnesium | Aluminum | |

| Speciesb | Carbonate | Bicarbonate, citrate | Hydroxide, carbonate, oxide, trisilicate | Hydroxide, carbonate, phosphate, glycinate |

| Category | Non-absorbable | Absorbable | Non-absorbable | Non-absorbable |

| ANC (mEq/15 mL)c | 58 | 17 | 35 | 29 |

| Maximum daily dosage limit (mEq)d | 160 | 200 (≤60 years old) and 100 (>60 years or older) | 50 | NA |

| Limitations | • Constipation and flatulence• Systemic alkalosis and hypercalcemia on long term use• Occasional milk-alkali syndrome in patients taking more than the recommended dose | • Non-serious, stomach/gut irritations that could cause gas or bloating | • Dose-related diarrhea• Flushing• Hypotension• Vasodilation• Hypermagnesemia | • Hypomagnesemia• Hypophosphatemia• Constipation• Anemia |

| FDA category for antacid use in pregnancye | None | None | None | None |

| Contraindications | ||||

| Renal impairment | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Hepatic impairment | No | Yes | No | No |

| Allergy to the antacid ingredient(s) in the formulation | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Others | • Patients with hypercalcemia, hypercalciuria, nephrocalcinosis, and nephrolithiasis• Patients on a low-phosphate diet | • Patients on a sodium- restricted diet, e.g., those with hypertension or congestive heart failure | • Patients with severe diarrhea • Patients with neuromuscular disease such as myasthenia gravis | • Patients with constipation |

aA salt is a chemical compound consisting of an ionic assembly of positively charged cations and negatively charged anions. The specific salts of active pharmaceutical ingredients are often formed to achieve desirable formulation properties. 96

bChemical species are specific forms of a particular element, such as an atom, molecule, ion, or radical. For example, chloride is an ionic species. 97

cThe potency of an antacid is generally expressed in terms of its ANC, which is defined as the number of mEq of 1 N HCl that are brought to pH 3.5 in 15 minutes (or 60 minutes in some tests) by a unit dose of the antacid preparation. 98

dAs per the federal register of the US FDA 99

eAntacids carry a FDA pregnancy category of None (N), meaning these drugs have not been classified by the FDA. 65

mEq, milliequivalents; ANC, acid-neutralizing capacity.

Calcium carbonate: Calcium carbonate reacts with gastric HCl to produce calcium chloride, carbon dioxide, and water. Calcium ions decrease heartburn symptoms by stimulating peristalsis in the esophagus and moving the acid into the stomach. Carbonate anions bind to free protons (H+) from HCl, hence decreasing H+ concentrations in the stomach and raising pH. In the alkaline conditions of the small intestine, soluble calcium chloride is converted back to calcium carbonate followed by excretion in stool, decreasing its absorption. 55

Sodium bicarbonate: Sodium bicarbonate, a rapidly acting antacid, reacts rapidly with gastric HCl in the stomach to produce sodium chloride, carbon dioxide, and water. Excess bicarbonate rapidly empties into the small intestine, where it is then absorbed. Sodium bicarbonate is often combined with citric acid. This combination reacts immediately with water to produce sodium citrate solution with the concomitant liberation of carbon dioxide. Sodium citrate is a fast-acting acid neutralizer that in suitable doses can raise stomach pH.

Magnesium salts: Magnesium hydroxide reacts rapidly with gastric HCl to produce magnesium chloride and water. Magnesium carbonate reacts with gastric HCl to produce magnesium chloride, carbon dioxide, and water. Magnesium trisilicate dissolves slowly, and reacts with gastric HCl to produce magnesium chloride, silicon dioxide, and water.

Aluminum salts: Aluminum hydroxide reacts with gastric HCl to produce aluminum chloride and water. Aluminum carbonate reacts with gastric HCl to produce aluminum chloride, carbon dioxide, and water. Aluminum phosphate reacts with gastric HCl to produce aluminum chloride and phosphoric acid.

Pepsin and bile acid inhibition activity

Pepsin is a proteinase that is produced from the inactive form pepsinogen by the parietal cells of the gastric mucosa, whereas bile acid is a digestive liquid produced by the liver.

Pepsin is activated at pH 1 to 2, and it has limited activity when the pH is around 3.5 to 5. 57 Glyco- and tauro-conjugated bile acids have been reported to be harmful to the esophageal mucosa at acidic pH (pH <4 and even down to pH 2 for tauro-conjugated bile acids). 58 In patients with reflux disease, both pepsin and bile acids have been found in the esophageal reflux. 59 Pepsin in the refluxate disrupts the esophageal mucosal barrier by acting on the epithelial cell surface, whereas bile acids achieve the same effect by diffusing into cells and damaging them. 60 Thus, the activity of pepsin and bile acids should be limited to prevent such damage. In 1971, an in vitro experiment by Kuruvilla revealed high anti-peptic activity (82% and 81%, respectively) for both magnesium carbonate and calcium carbonate. 61 In addition, aluminum and calcium antacids appear to adsorb pepsin and reduce its activity more strongly than would be predicted by pH changes alone. 62 Antacids such as magnesium and aluminum hydroxide can bind to bile salts, but magnesium hydroxide binds to bile salts at a much lesser extent than aluminum hydroxide.52,63 Thus, antacids are used as add-on treatments for gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, and esophagitis.

Special populations

Management of heartburn during pregnancy

Heartburn is a common consequence of pregnancy. Prior research presented the prevalence of heartburn as 22% in the first trimester, 39% in the second trimester, and 60% to 72% in the third trimester. 64 Increases in the levels of female sex hormones such as progesterone can reduce lower esophageal sphincter pressure. The step-up algorithm, starting with dietary changes and lifestyle modifications, should be used to manage heartburn during pregnancy. Antacids carry an FDA pregnancy category of none (N), which means these drugs have not been classified by the FDA. 65 Antacids are recommended as first-line treatments for heartburn in pregnancy when lifestyle modifications fail. If symptoms persist despite antacid use, then H2RAs can be used, excluding nizatidine because it has been found to be teratogenic in animal studies. All PPIs and H2RAs are FDA category B drugs, excluding omeprazole, which is an FDA category C drug. PPIs are reserved for women with complicated GERD or intractable symptoms. Approximately 30% to 50% of pregnant patients with symptoms will never need to “step-up” therapy from antacids. Although magnesium-, calcium-, and aluminum-containing antacids display good safety profiles during pregnancy, they should not be used for long-term therapy or in large doses.66,67 Treatments containing sodium bicarbonate should be avoided in pregnancy because of risks of fluid overload as well as maternal and fetal metabolic alkalosis risks (Table 2).

Management of gastroesophageal reflux in children

Infants normally experience gastroesophageal reflux symptoms that peak at 4 months of age because of physiological factors, and these events resolve over time. Antacids are not useful in infants with reflux symptoms, but they may be considered for short-term use in older children (12 years and older) to relieve heartburn.68,69 If regurgitation becomes frequent, then lifestyle changes, postural therapy, and thickened feedings should be considered.70,71

Comorbidities and concomitant medications

Similarly as any other medicines, antacids can potentially cause drug–drug interactions, especially in patients with comorbidities such as renal or hepatic impairment in those taking concurrent medications without medical supervision. Antacids can influence the rate and/or extent of absorption of concurrently administered drugs with pH-sensitive release from a dosage form, pH-dependent stability, or pH-dependent solubility by increasing gastric pH. 72

ANC and reliability of the in vitro test used

ANC, stated in mEq, is the amount of acid that can be neutralized using one standard dose of an antacid. The most effective antacids should have a high ANC that can be estimated by back titration through in vitro experiments. 73 The back titration method, a static test, is useful for comparing the level of neutralization achievable by a range of antacids, but it does not consider their rate of reaction. At least three variables, namely gastric secretion, gastric emptying, and the acid-consuming capacity, influence the efficacy of an antacid in vivo. The impact of the former two variables cannot be determined by back titration. However, more sophisticated in vitro models (e.g., dynamic simulators) can both measure all of these variables and offer a faster and more ethical alternative to studies in animals and humans. 74 According to the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use, the therapeutic equivalence of locally acting gastrointestinal products can be demonstrated using these in vitro or in vivo methods, provided they have been proven to accurately reflect in vivo drug release and availability at the sites of action. 75 The type of studies required to demonstrate equivalence should be determined via careful consideration of the product characteristics, mechanism of action, underlying disease being treated, validity of any in vitro or in vivo studies, the effects of any excipients, and differences in dose delivery systems.

Buffering capacity and reliability of the in vitro test used

Various in vitro tests have been developed to evaluate the buffering capacity of antacids. These tests include pH-stat titration and continuous acid challenge tests such as the Rossett–Rice method, the Simulator of the Human Intestinal Microbial Ecosystem (SHIME®), and the TNO Simulated Gastro-intestinal Tract Model 1 (TIM-1). These tests are dynamic, and they provide a more precise measure of antacid reactivity. pH-stat titration provides an accurate estimation of the rate at which the antacid is reacting under in vitro or fixed conditions, but it provides little information of its in vivo behavior.

By contrast, continuous acid challenge tests can serve as predictors of in vivo behavior. These tests are generally used to measure maximum pH achieved by an antacid, its duration of action, and the amount of antacid that will be lost if gastric emptying is simulated. The gastric emptying rate is an important factor for slowly reacting antacids such as magnesium trisilicate. The Rossett–Rice test is an acid neutralizing dynamic assay used as a standard to evaluate or compare the in vitro efficacy of antacid formulations. Using the Rossett–Rice test, Deepika et al. reported that the pH of acidic content was increased to 3.5 significantly faster and pH ≥3.5 was retained for a longer period with a sodium bicarbonate, sodium carbonate, and citric acid combination than with an aluminum hydroxide, magnesium hydrochloride, and simethicone combination. 50 The SHIME® apparatus mimics the physiological and microbiological conditions of the human gastrointestinal tract. The apparatus is the conglomeration of five reactors simulating different processes that occur in the human gastrointestinal tract. The steps required for food uptake and digestion in the stomach and small intestine are simulated by the first two reactors, whereas the other three compartments represent the ascending, transverse, and descending colon, respectively. 76 TIM-1 is a computer-controlled, dynamic, multi-compartmental system that simulates all physiological processes of the human upper gastrointestinal tract (lumen of the stomach and small intestine). 74 It offers relatively easy manipulation, reproducibility (no biological variation) and, most importantly, accuracy compared with in vivo techniques.

Summary

Antacids are widely used globally for the treatment of symptoms of acid-reflux related conditions. Despite their rapid action and good safety profile, antacids with a high ANC and good buffering capacity are required for the efficient management of these conditions. The ANC and buffering capacity can be measured using well-established test methods, thus making them predictive of the clinical effectiveness of antacid preparations in relieving gastrointestinal symptoms. For these reasons, providing the ANC and buffering capacity on labels as previously suggested could help ensure the quality, efficacy, and value of antacids. Nevertheless, the potential for adverse effects or drug interactions exists. Awareness of these possibilities is important because patients often fail to inform their physicians about antacid use unless specifically asked. Self-care and self-management are critical aspects of the evolving healthcare system in managing self-recognized minor ailments such as heartburn and acid regurgitation. To support this, pharmacists, the most accessible healthcare professionals, can improve patients’ awareness about antacid therapy and its related possibilities through counseling and education.

Acknowledgements

Syed Obaidur Rahman, Rajiv Kumar, and Nitu Bansal from WNS Global Services provided editorial and medical writing assistance with funding from GSK Consumer Healthcare.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: All authors are employees of GSK Consumer Healthcare.

Funding: Not applicable

ORCID iD: Prashant Narang https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2023-8839

References

- 1.Phupong V, Hanprasertpong T. Interventions for heartburn in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015: Cd011379. 2015/09/20. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD011379.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mandel KG, Daggy BP, Brodie DA, et al. Review article: alginate-raft formulations in the treatment of heartburn and acid reflux. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2000; 14: 669–690. 2000/06/10. DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mbatchou VC, Nabayire KO, Akuoko YJCS. Vernonia amygdalina Leaf: Unveiling its antacid and carminative properties In Vitro. Current Science 2017; 3: 148–155. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peterson WL, Sturdevant RA, Frankl HD, et al. Healing of duodenal ulcer with an antacid regimen. N Engl J Med 1977; 297: 341–345. 1977/08/18. DOI: 10.1056/nejm197708182970701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dajani EZ, Dajani NE, Shahwan TG. Over-the-Counter Drugs. In: Johnson LR (eds), Encyclopaedia of Gastroenterology Elsevier Science 2004: 16–33.

- 6.Van Marrewijk CJ, Mujakovic S, Fransen GA, et al. Effect and cost-effectiveness of step-up versus step-down treatment with antacids, H2-receptor antagonists, and proton pump inhibitors in patients with new onset dyspepsia (DIAMOND study): a primary-care-based randomised controlled trial. Lancet (London, England) 2009; 373: 215–225. 2009/01/20. DOI: 10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60070-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ching CK, Lam SK. Antacids. Indications and limitations. Drugs 1994; 47: 305–317. 1994/02/01. DOI: 10.2165/00003495-199447020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacob S, Shirwaikar A, Anoop S, et al. Acid neutralization capacity and cost-effectiveness of antacids sold in various retail pharmacies in the United Arab Emirates. Hamdan Medical Journal 2016; 9: 137. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nirwan JS, Hasan SS, Babar ZU, et al. Global Prevalence and Risk Factors of Gastro-oesophageal Reflux Disease (GORD): Systematic Review with Meta-analysis. Scientific reports 2020; 10: 5814. 2020/04/04. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-020-62795-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eusebi LH, Ratnakumaran R, Yuan Y, et al. Global prevalence of, and risk factors for, gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms: a meta-analysis. Gut 2018; 67: 430–440. 2017/02/25. DOI: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kellerman R, Kintanar T. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Primary care 2017; 44: 561–573. 2017/11/15. DOI: 10.1016/j.pop.2017.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spechler SJ, Jain SK, Tendler DA, et al. Racial differences in the frequency of symptoms and complications of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002; 16: 1795–1800. 2002/09/25. DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fock KM, Talley N, Goh KL, et al. Asia-Pacific consensus on the management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: an update focusing on refractory reflux disease and Barrett's oesophagus. Gut 2016; 65: 1402–1415. 2016/06/05. DOI: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-311715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamasaki T, Hemond C, Eisa M, et al. The Changing Epidemiology of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: Are Patients Getting Younger? J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2018; 24: 559–569. 2018/10/24. DOI: 10.5056/jnm18140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Savarino E, Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, et al. Expert consensus document: Advances in the physiological assessment and diagnosis of GERD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017; 14: 665–676. 2017/09/28. DOI: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rubenstein JH, Inadomi JM, Scheiman J, et al. Association between Helicobacter pylori and Barrett's esophagus, erosive esophagitis, and gastroesophageal reflux symptoms. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 12: 239–245. 2013/08/31. DOI: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harrison C, Henderson J, Miller G, et al. The prevalence of diagnosed chronic conditions and multimorbidity in Australia: A method for estimating population prevalence from general practice patient encounter data. PloS one 2017; 12: e0172935. 2017/03/10. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ammar A, Brach M, Trabelsi K, et al. Effects of COVID-19 Home Confinement on Eating Behaviour and Physical Activity: Results of the ECLB-COVID19 International Online Survey. Nutrients 2020; 12: 1583. 2020/06/03. DOI: 10.3390/nu12061583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abenavoli L, Cinaglia P, Lombardo G, et al. Anxiety and Gastrointestinal Symptoms Related to COVID-19 during Italian Lockdown. J Clin Med 2021; 10: 1221. 2021/04/04. DOI: 10.3390/jcm1006 1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakov R, Dimitrova-Yurukova D, Snegarova V, et al. Increased prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms and disorders of gut-brain interaction during the COVID-19 pandemic: An internet-based survey. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2021; 34: e14197. 2021/06/20. DOI: 10.1111/nmo.14197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rajendra S, Alahuddin S. Racial differences in the prevalence of heartburn. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004; 19: 375–376. 2004/02/27. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spechler SJ. Clinical practice. Barrett's Esophagus. The New England journal of medicine 2002; 346: 836–842. 2002/03/15. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMcp012118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhatia SJ, Reddy DN, Ghoshal UC, et al. Epidemiology and symptom profile of gastroesophageal reflux in the Indian population: report of the Indian Society of Gastroenterology Task Force. Indian J Gastroenterol 2011; 30: 118–127. 2011/07/28. DOI: 10.1007/s12664-011-0112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones R, Ballard K. Healthcare seeking in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a qualitative study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008; 20: 269–275. 2008/03/13. DOI: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282f2a5bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mansour-Ghanaei F, Joukar F, Atshani SM, et al. The epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a survey on the prevalence and the associated factors in a random sample of the general population in the Northern part of Iran. Int J Mol Epidemiol Genet 2013; 4: 175–182. 2013/09/21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mostaghni A, Mehrabani D, Khademolhosseini F, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of gastroesophageal reflux disease in Qashqai migrating nomads, southern Iran. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15: 961–965. 2009/02/28. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.15.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clarrett DM, Hachem C. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD). Mo Med 2018; 115: 214–218. 2018/09/20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DeVault KRJPG, Toolkit HBR. Heartburn, Regurgitation, and Chest Pain. Practical Gastroenterology and Hepatology Board Review Toolkit 2016: 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Gastroenterology Organisation Global Guidelines. A Global Perspective on Heartburn, Constipation, Bloating, and Abdominal Pain/Discomfort, www.worldgastroenterology.org/guidelines/global-guidelines/common-gi-symptoms/common-gi-symptoms-english (2013, accessed 14 August 2021).

- 30.Rohof WO, Bennink RJ, Boeckxstaens GE. Proton pump inhibitors reduce the size and acidity of the acid pocket in the stomach. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 12: 1101–1107.e1101. 2014/04/15. DOI: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhatia SJ, Makharia GK, Abraham P, et al. Indian consensus on gastroesophageal reflux disease in adults: A position statement of the Indian Society of Gastroenterology. Indian J Gastroenterol 2019; 38: 411–440. 2019/12/06. DOI: 10.1007/s12664-019-00979-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chey WD, Mody RR, Wu EQ, et al. Treatment patterns and symptom control in patients with GERD: US community-based survey. Curr Med Res Opin 2009; 25: 1869–1878. 2009/06/18. DOI: 10.1185/03007990903035745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holtermüller KH, Dehdaschti M. Antacids and hormones. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl 1982; 75: 24–31. 1982/01/01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.CFR - Code of Federal Regulations Title 21. Antacid active ingredients, www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?CFRPart=331&showFR=1 (2020, accessed 08 July 2021).

- 35.Dent J, Brun J, Fendrick A, et al. An evidence-based appraisal of reflux disease management–the Genval Workshop Report. Gut 1999; 44: S1–16. 2000/03/31. DOI: 10.1136/gut.44.2008.s1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaplan-Machlis B, Spiegler GE, Revicki DA. Health-related quality of life in primary care patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Ann Pharmacother 1999; 33: 1032–1036. 1999/10/26. DOI: 10.1345/aph.18424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Revicki DA, Zodet MW, Joshua-Gotlib S, et al. Health-related quality of life improves with treatment-related GERD symptom resolution after adjusting for baseline severity. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2003; 1: 73. 2003/12/03. DOI: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wiklund I, Carlsson J, Vakil N. Gastroesophageal reflux symptoms and well-being in a random sample of the general population of a Swedish community. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101: 18–28. 2006/01/13. DOI: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee SW, Lien HC, Lee TY, et al. Heartburn and regurgitation have different impacts on life quality of patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20: 12277–12282. 2014/09/19. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i34.12277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gerson LB, Fass R. A systematic review of the definitions, prevalence, and response to treatment of nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009; 7: 372–378. quiz 367. 2008/12/30. DOI: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Revicki DA, Crawley JA, Zodet MW, et al. Complete resolution of heartburn symptoms and health-related quality of life in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1999; 13: 1621–1630. 1999/12/14. DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Velanovich V. Quality of life and severity of symptoms in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a clinical review. Eur J Surg 2000; 166: 516–525. 2000/08/31. DOI: 10.1080/110241500750008565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Revicki DA, Wood M, Maton PN, et al. The impact of gastroesophageal reflux disease on health-related quality of life. Am J Med 1998; 104: 252–258. 1998/04/29. DOI: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00354-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Earnest D, Robinson M, Rodriguez-Stanley S, et al. Managing heartburn at the ‘base' of the GERD ‘iceberg': effervescent ranitidine 150 mg b.d. provides faster and better heartburn relief than antacids. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2000; 14: 911–918. 2000/07/25. DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lai IR, Wu MS, Lin JT. Prospective, randomized, and active controlled study of the efficacy of alginic acid and antacid in the treatment of patients with endoscopy-negative reflux disease. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12: 747–754. 2006/03/08. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i5.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.World Health organization. Guidelines for the Regulatory Assessment of Medicinal Products for use in Self-Medication, apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/66154/WHO_EDM_QSM_00.1_eng.pdf (2000, accessed 16 September 2021).

- 47.World Health organization. What do we mean by self-care?, www.who.int/reproductivehealth/self-care-interventions/definitions/en/ (2021, accessed 16 September 2021).

- 48.The New York Times. For a nation on edge, antacids become hard to find, www.nytimes.com/2020/12/08/business/virus-tums-pepcid-hard-to-find.html (2020, accessed 10 September 2021).

- 49.Bennett P, Brown M. Clinical pharmacology, 10th edn. Edinburgh: Churchill livingstone. Elsevier, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aggarwal D, Patel S, Santoro A. In-vitro characterization of the acid-neutralizing capacity of ENO® Regular and other commercially-available antacids. Gazzetta Medica Italiana Archivio per le Scienze Mediche 2017; 176: 486–487. DOI: 10.23736/S0393-3660.16.03421-5. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Johnson SM, Suralik JJPG. A Comparison of the Effect of Regular Eno® and Placebo on Intragastric pH. Practical Gastroenterology 2009: 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cheraghali AM. Application for the removal of “Antacids” from the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines, https://www.who.int/selection_medicines/committees/expert/18/applications/Antacids_deletion.pdf (accessed 16 January 2022).

- 53.Katakam P, Tantosh N, Aleshy A, et al . A comparative study of the acid neutralizing capacity of various commercially available antacid formulations in Libya. Libyan journal of medical research 2010; 7: 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Houshia OJ, AbuEid M, Zaid O, et al. Assessment of the value of the antacid contents of selected palestinian plants. American Journal of Chemistry 2012; 2: 322–325. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mejia A, Kraft WK. Acid peptic diseases: pharmacological approach to treatment. Expert review of clinical pharmacology 2009; 2: 295–314. 2009/05/01. DOI: 10.1586/ecp.09.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Van Tonningen MR. Gastrointestinal and antilipidemic agents and spasmolytics. Drugs During Pregnancy and Lactation. Elsevier, 2007, pp.94–122.

- 57.Dipiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, et al. Pharmacotherapy: a pathophysiologic approach, ed. McGraw-Hill Medical, New York, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bechi P, Cianchi F, Mazzanti R, et al. Reflux and pH:‘alkaline’components are not neutralized by gastric pH variations. Diseases of the Esophagus 2000; 13: 51–55. DOI: 10.1046/j.1442-2050.2000.00063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Woodland P, Sifrim DJBp. The refluxate: the impact of its magnitude, composition and distribution. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2010; 24: 861–871. DOI: 10.1016/j.bpg.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bardhan KD, Strugala V, Dettmar PW. Reflux revisited: advancing the role of pepsin. Int J Otolaryngol 2012; 2012: 646901. DOI: 10.1155/2012/646901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kuruvilla JT. Antipeptic activity of antacids. Gut 1971; 12: 897–898. 1971/11/01. DOI: 10.1136/gut.12.11.897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fordtran JS, Collyns JA. Antacid pharmacology in duodenal ulcer. Effect of antacids on postcibal gastric acidity and peptic activity. N Engl J Med 1966; 274: 921–927. 1966/04/28. DOI: 10.1056/nejm196604282741701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Clain JE, Malagelada J-R, Chadwick VS, et al. Binding properties in vitro of antacids for conjugated bile acids. Gastroenterology 1977; 73: 556–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vazquez JC. Heartburn in pregnancy. BMJ clinical evidence 2015; 2015: 1411. 2015/09/09. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thélin CS, Richter JE. Review article: the management of heartburn during pregnancy and lactation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2020; 51: 421–434. 2020/01/18. DOI: 10.1111/apt.15611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fellows H, Dalton H. Gastrointestinal drugs. Side Effects of Drugs Annual. 4th ed. Elsevier, 2008, p.51.

- 67.Mahadevan U. Gastrointestinal medications in pregnancy. Best practice & research Clinical gastroenterology 2007; 21: 849–877. 2007/09/25. DOI: 10.1016/j.bpg.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Leung AK, Hon KL. Gastroesophageal reflux in children: an updated review. Drugs in context 2019; 8: 212591. 2019/07/02. DOI: 10.7573/dic.212591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rosen R, Vandenplas Y, Singendonk M, et al. Pediatric Gastroesophageal Reflux Clinical Practice Guidelines: Joint Recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2018; 66: 516–554. 2018/02/23. DOI: 10.1097/mpg.0000000000001889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jawdeh EG, Martin RJ. Neonatal apnea and gastroesophageal reflux (GER): is there a problem? Early human development 2013; 89: S14–S16. 2013/07/03. DOI: 10.1016/s0378-3782(13)70005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rostas SE, McPherson C. Acid Suppression for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Infants. Neonatal network: NN 2018; 37: 33–41. 2018/02/14. DOI: 10.1891/0730-0832.37.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Patel D, Bertz R, Ren S, et al. A Systematic Review of Gastric Acid-Reducing Agent-Mediated Drug-Drug Interactions with Orally Administered Medications. Clin Pharmacokinet 2020; 59: 447–462. 2019/12/04. DOI: 10.1007/s40262-019-00844-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ayensu I, Bekoe SO, Adu JK, et al. Evaluation of acid neutralizing and buffering capacities of selected antacids in Ghana. Scientific African 2020; 8: e00347. DOI: 10.1016/j.sciaf.2020.e00347. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Verhoeckx K, Cotter P, López-Expósito I, et al. (eds) The Impact of Food Bioactives on Health: in vitro and ex vivo models. Cham (CH): Springer Copyright; 2015, PMID: 29787039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.European medicines agency. Guideline on equivalence studies for the demonstration of therapeutic equivalence for locally applied, locally acting products in the gastrointestinal tract, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-equivalence-studies-demonstration-therapeutic-equivalence-locally-applied-locally-acting_en.pdf (2018, July 05 September 2021).

- 76.Voropaiev M, Nock D. Onset of acid-neutralizing action of a calcium/magnesium carbonate-based antacid using an artificial stomach model: an in vitro evaluation. BMC gastroenterology 2021; 21: 112. 2021/03/08. DOI: 10.1186/s12876-021-01687-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Walker D, Ng Kwet Shing R, Jones D, et al. Challenges of correlating pH change with relief of clinical symptoms in gastro esophageal reflux disease: a phase III, randomized study of Zegerid versus Losec. PloS one 2015; 10: e0116308. 2015/02/24. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Orbelo DM, Enders FT, Romero Y, et al. Once-daily omeprazole/sodium bicarbonate heals severe refractory reflux esophagitis with morning or nighttime dosing. Digestive diseases and sciences 2015; 60: 146–162. 2014/01/23. DOI: 10.1007/s10620-013-3017-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Higuera-de-la-Tijera F. Efficacy of omeprazole/sodium bicarbonate treatment in gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Medwave 2018; 18: e7179. 2018/03/17. DOI: 10.5867/medwave.2018.02.7179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sulz MC, Manz M, Grob P, et al. Comparison of two antacid preparations on intragastric acidity–a two-centre open randomised cross-over placebo-controlled trial. Digestion 2007; 75: 69–73. 2007/05/15. DOI: 10.1159/000102627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Collings KL, Rodriguez-Stanley S, Proskin HM, et al. Clinical effectiveness of a new antacid chewing gum on heartburn and oesophageal pH control. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002; 16: 2029–2035. 2002/11/28. DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rodriguez-Stanley S, Ahmed T, Zubaidi S, et al. Calcium carbonate antacids alter esophageal motility in heartburn sufferers. Digestive diseases and sciences 2004; 49: 1862–1867. 2005/01/05. DOI: 10.1007/s10620-004-9584-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Robinson M, Rodriguez-Stanley S, Ciociola AA, et al. Synergy between low-dose ranitidine and antacid in decreasing gastric and oesophageal acidity and relieving meal-induced heartburn. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics 2001; 15: 1365–1374. 2001/09/13. DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.01058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ohning G, Walsh J, Thomas D, et al. Famotidine/antacid combination is superior in overall control of gastric acid output compared to ranitidine 75 mg or calcium carbonate 1000 mg. Practical Gastroenterology 2000; 24: 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Walsh J, Thomas D, Decktor D, et al. A comparison of famotidine/antacid combination (FACT) vs. ranitidine 75 mg or calcium carbonate 1000 mg on human gastric acid secretion. The American journal of gastroenterology 2000; 95: 2455. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Robinson M, Rodriguez-Stanley S, Miner PB, et al. Effects of antacid formulation on postprandial oesophageal acidity in patients with a history of episodic heartburn. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics 2002; 16: 435–443. 2002/03/06. DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Feldman M. Comparison of the effects of over-the-counter famotidine and calcium carbonate antacid on postprandial gastric acid. A randomized controlled trial. Jama 1996; 275: 1428–1431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Netzer P, Brabetz-Höfliger A, Bründler R, et al . Comparison of the effect of the antacid Rennie versus low-dose H. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics 1998; 12: 337–342. DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1998.00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Levine JG, Murakami A, Furtek C, et al. Famotidine/antacid combination tablets are more effective for the treatment of heartburn than either component alone: 4. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology 2004; 99: S2. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Decktor DL, Robinson M, Maton PN, et al. Effects of Aluminum/Magnesium Hydroxide and Calcium Carbonate on Esophageal and Gastric pH in Subjects with Heartburn. American journal of therapeutics 1995; 2: 546–552. 1995/08/01. DOI: 10.1097/00045391-199508000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Parente F, Bianchi Porro G, Canali A, et al. Double-blind randomized, multicenter study comparing aluminium phosphate gel with rantitidine in the short-term treatment of duodenal ulcer. Hepato-gastroenterology 1995; 42: 95–99. 1995/04/01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Weberg R, Berstad A. Symptomatic effect of a low-dose antacid regimen in reflux oesophagitis. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology 1989; 24: 401–406. 1989/05/01. DOI: 10.3109/00365528909093066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Farup PG, Weberg R, Berstad A, et al. Low-dose antacids versus 400 mg cimetidine twice daily for reflux oesophagitis. A comparative, placebo-controlled, multicentre study. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology 1990; 25: 315–320. 1990/03/01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Graham DY, Patterson DJ. Double-blind comparison of liquid antacid and placebo in the treatment of symptomatic reflux esophagitis. Digestive diseases and sciences 1983; 28: 559–563. 1983/06/01. DOI: 10.1007/bf01308159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Meteerattanapipat P, Phupong V. Efficacy of alginate-based reflux suppressant and magnesium-aluminium antacid gel for treatment of heartburn in pregnancy: a randomized double-blind controlled trial. Scientific reports 2017; 7: 44830. 2017/03/21. DOI: 10.1038/srep44830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gupta D, Bhatia D, Dave V, et al. Salts of therapeutic agents: chemical, physicochemical, and biological considerations. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 2018; 23: 1719. DOI: 10.3390/molecules23071719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.IUPAC Goldbook. Chemical species, https://goldbook.iupac.org/terms/view/CT01038 (2019, accessed 16 January 2022).

- 98.Parakh R, Patil N. Anaesthetic antacids: a review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic efficacy. International Journal of Research in Medical Sciences 2018; 6: 383–393. DOI: 10.18203/2320-6012.ijrms20180005. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Food and drug administration, department of health, education, and welfare. Antacid products for over-the-counter (OTC) human use, https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/fedreg/fr039/fr039108/fr039108.pdf#page=78 (1974, accessed 17 January 2022).