Description

A baby was delivered at 32 weeks’ gestation by caesarean section due to profound ascites (figures 1 and 2) with an estimated fetal weight of 6680 g. Isolated ascites had been identified at an otherwise normal 20-week anomaly scan. No cause was identified (no anaemia, negative TORCH (Toxoplasma, Rubella, Cytomegalovirus, Herpes Simplex and HIV) screen, protective serology) and maternal history was unremarkable.

Figure 1.

Neonate showing profound ascites.

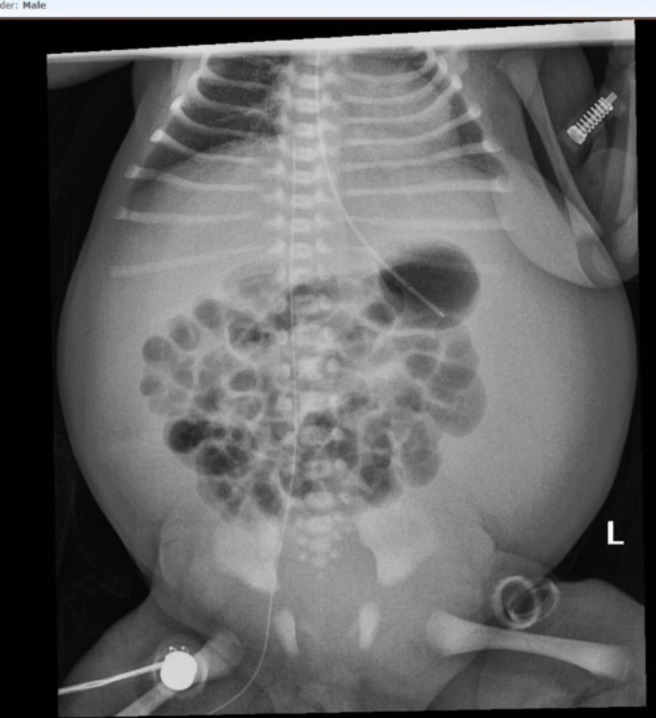

Figure 2.

X-ray showing extent of ascites and impact on lung volume.

Four hundred millilitres of ascites was drained intraoperatively and he was born in good condition but was subsequently intubated at 9 minutes of life due to respiratory distress. He was ventilated for a total of 8 days.

Analysis of the ascitic fluid showed a lymphocytic effusion, primarily T cells (chyle).

He was initially started on total parenteral nutrition. A hydrolysed preterm formula was introduced on day 4. This was subsequently switched to a formula low in long-chain triglycerides, which was steadily increased, with an interruption for a contrast study due to bilious aspirates.

The baby’s weight fell by 17% in the first fortnight with significant resolution of ascites over the 3 weeks before he was discharged to his local neonatal unit.

The cause of his chylous ascites remains unknown. All investigations, including karyotype, cranial ultrasounds and abdominal ultrasound, were normal. Echocardiogram on day 1 of life showed a structurally normal, but slightly hypertrophied, heart with a patent ductus arteriosus and patent foramen ovale. The baby is now well and thriving.

Congenital chylous ascites (CCA) is the accumulation of chyle (lymphatic fluid rich in triglycerides, particularly chylomicrons) in the peritoneal cavity in infants under 3 months. Diagnosis is made from analysis of the fluid. CCA is very rare, particularly as an isolated finding. Due to its rarity, there is no reported incidence or established gold standard management.

Chylous ascites can be secondary to many pathologies, particularly malignancies, trauma and surgical damage to the lymphatic system. CCA results from abnormalities of the abdominal lymphatic system.1 Obstructed lymphatic flow at lymphaticovenous and lympholymphatic channels raises intralacteal pressure causing subsequent extravasation2 while maldevelopment of the vessels may cause idiopathic ‘leaky lymphatics’.1–4

Initial treatment is conservative, with avoidance of long-chain triglycerides. This may mean keeping the baby nil by mouth with total parenteral nutrition or using formulas low in long-chain fatty acids. This aims to slow lymphatic flow and reduce intestinal secretions.1 Paracentesis can alleviate abdominal pressure and respiratory distress; however, drainage of large volumes of fluid should be done cautiously due to the resultant protein loss.

Octreotide, a somatostatin analogue, has been used to reduce lymphatic excretion of chyle. It is postulated to work through a reduction of splanchnic blood flow, intestinal motility and fat absorption.5 6

If a prolonged period of conservative measures is unsuccessful, surgery is sometimes required to identify and ligate a site of lymphatic leak.

Consequences of significant chyle leak into the peritoneum include malnutrition and immune deficiency, secondary to protein and lymphocyte loss.1

In summary, this is a case of severe, isolated, CCA requiring premature delivery of the baby with paracentesis during the caesarean section. The baby responded well to conservative management with an excellent outcome.

Learning points.

Isolated congenital ascites is rare. Congenital chylous ascites is especially rare meaning that there is no universal approach to management.

The underlying pathology is usually an abnormality of the abdominal lymphatic system—structural or functional—including raised intralacteal pressure due to obstructed drainage.

Management aims to reduce lymphatic leak. This is primarily through conservative means with avoidance of long-chain fatty acids ± paracentesis or ascitic drainage. Sometimes, however, surgery is required to identify and repair the source of chyle leakage.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Dr Leigh Dyet for reading the article and making suggestions.

Footnotes

Twitter: @drClaireEmma

Contributors: CES is the sole author of this article.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Case reports provide a valuable learning resource for the scientific community and can indicate areas of interest for future research. They should not be used in isolation to guide treatment choices or public health policy.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained from parent(s)/guardian(s).

References

- 1.Mouravas V, Dede O, Hatziioannidis H, et al. Diagnosis and management of congenital neonatal chylous ascites. Hippokratia 2012;16:175–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aalami OO, Allen DB, Organ CH. Chylous ascites: a collective review. Surgery 2000;128:761–78. 10.1067/msy.2000.109502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellini C, Ergaz Z, Radicioni M, et al. Congenital fetal and neonatal visceral chylous effusions: neonatal chylothorax and chylous ascites revisited. A multicenter retrospective study. Lymphology 2012;45:91–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolf DC. Ascites: overview, pathophysiology, etiology. Available: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article185777-overview [Accessed 10 Oct 2020].

- 5.Olivieri C, Nanni L, Masini L, et al. Successful management of congenital chylous ascites with early octreotide and total parenteral nutrition in a newborn. BMJ Case Rep 2012;2012. 10.1136/bcr-2012-006196. [Epub ahead of print: 25 Sep 2012]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhardwaj R, Vaziri H, Gautam A, et al. Chylous ascites: a review of pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Transl Hepatol 2018;6:1–9. 10.14218/JCTH.2017.00035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]