Abstract

The coronavirus pandemic continues to hinder the ability of businesses to operate at full capacity. Vaccination offers a path for employees to return to work, and for businesses to resume full capacity, while protecting themselves, their fellow workers, and customers. Many employers reluctant to mandate vaccination for their employees are considering other ways to increase employee vaccination rates. Because much has been written about the ethics of vaccine mandates, we examine a related and less discussed topic: the ethics of encouragement strategies aimed at overcoming vaccine reluctance (which can be due to resistance, hesitance, misinformation, or inertia) to facilitate voluntary employee vaccination. While employment-based vaccine encouragement may raise privacy and autonomy concerns, and though some employers might hesitate to encourage employees to get vaccinated, our analysis suggests ethically acceptable ways to inform, encourage, strongly encourage, incentivize, and even subtly pressure employees to get vaccinated.

Keywords: Autonomy, COVID-19, Privacy, Vaccine encouragement, Vaccine incentives

Key messages

Employment-based vaccine encouragement can raise some privacy and autonomy concerns

Nevertheless, there are ethically acceptable ways to inform, encourage, incentivize, and even subtly pressure employees to get vaccinated

Employers should scale encouragement levels to the necessity of having vaccinated employees working in-person

Introduction

The coronavirus pandemic has hindered the ability of businesses to operate at full capacity because of threats of infection. Given that studies have shown vaccines provide strong protection against COVID-19 at high levels of safety [1], vaccination has offered a path for employees to return to work and for businesses to regain full capacity, while protecting themselves, their fellow workers, and customers. Although vaccination rates in the United States (US) initially rose quickly in the first half of 2021, vaccine uptake eventually slowed later that summer, leaving pockets of the country where vaccination rates remain low [2]. In the interest of accelerating the resumption of normal operations and increasing productivity, many employers have considered steps to increase the vaccination rates of their employees [3].

Key agencies like the Centers for Disease Control have issued some practical guidance about how to boost vaccination in the workplace [4, 5], and there has been a vigorous debate among bioethicists, policymakers and politicians about the ethics and propriety of institution-wide vaccine mandates [6, 7]. Outside of health and university settings, companies have been hesitant to mandate vaccination as a condition of employment [8]. Even after the US Labor Department’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration proposed (and then rescinded in January 2022) a vaccine and testing requirement, some companies remain reluctant to mandate vaccination unless forced to do so. This reluctance raises questions about the ethics of encouraging rather than mandating vaccination, a topic that has received considerably less attention. This Viewpoint explores the complex ethical contours of options for encouraging employee vaccination. We focus on strategies aimed at overcoming vaccine reluctance (which can be due to resistance, hesitance, misinformation, or inertia) to facilitate voluntary employee vaccination. We argue that while such practices may raise some privacy and autonomy concerns, there are ethically acceptable encouragement strategies available to employers.

Degrees of encouragement

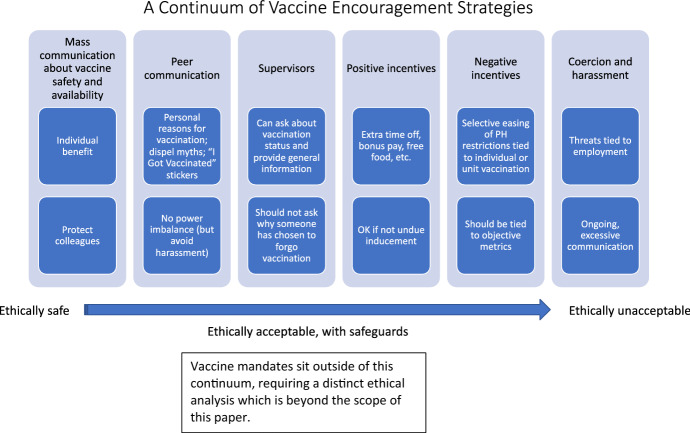

The extremes of the vaccination encouragement spectrum seem relatively straightforward (Fig. 1). At one end, it seems clearly acceptable for employers to distribute information to all employees about the benefits, safety, and availability of vaccines. Communication of this information could occur through emails distributed by leadership and supervisors of specific units. Given that employers have an interest in the health of their employees and can act as a conduit for reliable information, there are ethical reasons for places of employment to clearly communicate essential facts about the pandemic and vaccination, including evidence-based information about the individual, familial, workplace, and public health benefits of getting immunologic protection. This practice is ethical because disseminating scientifically accurate information poses no risk of harm to employees, who may benefit from reliable information. The employer is simply acting as a conduit for information; the employer is not asking the employee to take any action, nor is the employer imposing any negative consequences on any employee. Employers should ensure that the information is reliable, or at least comes from reliable sources. They should avoid promulgating information that is biased or skewed to the benefit of certain groups.

Fig. 1.

A continuum of vaccine encouragement strategies

It also seems clearly acceptable for employers to combine this information with explicit, but general, information about the benefits of seeking COVID-19 vaccination, if supported by the strength of the evidence regarding safety and efficacy of existing vaccines. These group communications could address not only the individual benefits of receiving one of the approved vaccines, but also should reiterate employees’ responsibilities to help protect others. For example, emails and other forms of communication could describe ways that vaccination can help ensure a safe work environment, help protect the health of co-workers, and reduce the spread of disease in the larger community. These communications can and should emphasize the importance of employees not becoming vectors of transmission and the value of participating in a common effort to protect themselves and their communities. Like general information about vaccination, general messages about the personal and community value of vaccination can be ethically appropriate because employees are free to ignore the information, as they would any other kind of general workplace communication unrelated to their direct duties or responsibilities (such as information about signing up for a voluntary workplace wellness program).

On the other end of the spectrum, broad vaccine mandates can be ethically appropriate when applied neutrally, with clear articulation about the consequences of not complying with the policy (for example, reassignment to different job area or tasks). In that circumstance, employees have a choice between getting vaccinated or accepting the consequences of a choice to remain unvaccinated. Employers have the right to specify many conditions of employment, particularly relating to creation of a safe work environment (such as prohibition of indoor smoking). Outside the context of a broad institution-wide mandate, it would be unethical for specific supervisors (or high-level employees without a supervisory role) to coerce or harass individual employees to get vaccinated. Encouragement rises to the level of harassment when it is excessive and ongoing to the point of creating “a work environment that would be intimidating, hostile, or offensive to reasonable people” [9]. In the context of supervisor and employee relationships, harassing actions involve a misuse of power imbalances that could create unacceptably hostile working conditions and undermine the voluntary nature of the vaccination.

Between appropriate provision of general information to groups of employees and inappropriate coercion or harassment of individuals, lie a variety of ethically acceptable ways for employers to encourage vaccination at both the individual and group level—with some important limits. At the group level, communications could go beyond general information about the pandemic and vaccine to positively encourage vaccination. Employers could include targeted statistics (such as 75% of the company or unit have been vaccinated) to spur competition or even implicitly embarrass vaccine resistors. Like general mass communication, these more specific mass communications seem ethically unproblematic, so long as the data do not permit the target audience to easily identify the unvaccinated individuals. If the communication achieves its objective ethically, the possibility of harassment or coercion is low. Any pressure an individual may feel to get vaccinated would result from diffuse membership in a group rather than a fear about consequences targeted to a particular person.

Group-level communication about the benefits of vaccination for individuals and the public is important, but it may be less effective than individual-level communication. Engaging trusted peers in more targeted efforts may be an effective way to communicate with vaccine-hesitant or misinformed portions of the workforce. This can take the form of ad hoc information and encouragement between peers, or a more formal effort where knowledgeable peers actively reach out to the wider workforce, specific groups, or particular unvaccinated individuals. In any of these forms, peers can help to dispel myths about vaccination and share their reasons for getting vaccinated.

Generally, peers engaging specific employees does not trigger concerns about employment-related harms because peers do not have supervisory authority over similarly situated colleagues. Conversations among peers about vaccination status are appropriate so long as these conversations do not become so intensive as to constitute harassment. Employers should not offer peers incentives for successfully convincing colleagues to get vaccinated; any kind of reward may create conditions for harassment of others.

There can be social consequences associated with peer communication about vaccination, such as stigma and ostracization of those not vaccinated. Individuals who choose to make the workplace less safe for others through their vaccine refusal should be able to foresee the possibility of this kind of social consequence, independent of peer engagement about the benefits of vaccination. Peers may communicate the reasons why they chose vaccination and their desire to work with individuals who are vaccinated based on their expectation for a safe work environment and to avoid responsibilities falling disproportionately on vaccinated employees who can safely return in-person. These points help employees clarify the benefits of vaccination to those who are vaccine-hesitant.

Supervisors may communicate with their supervisees about the general importance of vaccination at the individual or group level. Unless the employer has adopted an institution-wide vaccine mandate, to avoid even the impression of coercion any supervisors (or higher-level employees without a supervisory role) engaging in conversations about vaccination should make explicit that vaccination status will not affect employment status (including raises, promotions) or existing benefits (such as restricting paid leave). Supervisors may legitimately need to ask about individual vaccination status (and legitimate exemptions) to provide important information about vaccine rates in a particular unit. Certain questions, such as asking why someone is not vaccinated (or the reason for their exemption), may infringe on privacy as an employee may feel forced to disclose a medical condition or a particular religious belief. Thus, supervisors should not engage in follow-up discussions that may make an individual feel pressured to disclose personal information. This does not mean, however, that supervisors must immediately cut off a conversation after being told that an employee has not been vaccinated. If the employee is clearly amenable (if the person asks questions or requests assistance), the supervisor may ethically offer to provide information, answer questions or concerns, provide referrals to health care providers, and even facilitate arrangements for vaccination.

Some employees might worry that, despite explicit statements to the contrary, supervisors may use information learned about an employee’s vaccination status to make decisions about work assignments, raises, and promotions. Workplaces should have explicit policies to prohibit discriminatory employment decisions, but this does not preclude employers from making legitimate evidence-based policies about where to assign unvaccinated workers to minimize specific health risks. For example, employers could appropriately restrict unvaccinated health care personnel from working with high-risk patients. While worry about unjustified discrimination based on vaccination status is understandable, mere hypothetical concern about this possibility is not sufficient to warrant complete restriction of vaccine conversations between supervisors and employees.

Beyond encouragement based on sound information, strategies involving negative and positive incentives raise ethical concerns. There have been proposals to offer cash payment for vaccination [10]. Businesses could offer other incentives, including extra paid time off, free meals, spa services, or product discounts. Employers can structure such incentives to reward individuals directly or aim them at groups of employees to recognize their collective attainment of specific vaccination goals (for example, 75% of vaccination within a unit). They can be structured prospectively (applicable to future vaccinations only) or universally (available to people already vaccinated also). The latter is fairer and avoids a bad precedent: offering incentives only to people who have delayed vaccination could establish a norm of employees avoiding taking steps to advance workplace and public health unless and until offered incentives to do so [11].

Though there have been arguments made for [12] and against [13] the ethical acceptability of incentives, we view modest incentives as acceptable, unless they constitute an undue inducement. We stress that incentives resulting in individuals taking steps they would not otherwise have taken (deciding to get vaccinated) does not make them ‘undue.’ An incentive constitutes an undue inducement only when it “triggers irrational decision-making given the agent’s own settled (and reasonable) values and aims” [14]. That is, is the incentive so attractive that it interferes with individuals’ abilities to make reasoned assessments of the risks and benefits associated with the activity? While there is no consensus about the amount of money or in-kind benefit that might have this effect, participation in clinical trials may commonly offer compensation in the thousands of dollars. In that situation, risks and, hence, concern over the potential for undue inducement are greater. In contrast, the COVID vaccines approved for emergency use in the United States have been demonstrated to be highly efficacious and exceedingly safe, based on hundreds of millions of doses administered. Thus, it is extremely unlikely that commonly proposed incentives in the $100–200 range [15] would raise concern about individuals making decisions that are contrary to their interests.

Some employers are also exploring the idea of selectively easing public health restrictions, tied to individual vaccination status, or vaccination rates in units [3]. For example, an institution might allow certain sets of vaccinated employees back into the office or might allow a unit to utilize more relaxed masking practices. Though this strategy can be framed as a kind of positive incentive to get vaccinated, it might be understood as a form of implicit pressure on unvaccinated employees, many of whom may see selective loosening of restrictions as negatively impacting them. On an individual level, those who decide not to get vaccinated might feel disadvantaged in relation to their vaccinated peers. This could be particularly acute in a competitive work environment, where productivity and opportunities for advancement are unavoidably enhanced by working on site (for example, for lab-based biomedical researchers, teachers). When a policy is tied to group vaccination metrics, unvaccinated employees may feel implicit (or explicit) pressure from peers or supervisors to help the group meet its return-to-work goals. For example, in March 2021, Major League Baseball adopted a policy allowing for more small group activities and reduced mask usage, but only after vaccination of at least 85% of the on-field players and staff [16]. Despite worries about a perception of unfairness, we argue that the selective easing of public health restrictions is ethically appropriate when done transparently and tied to objective public health guidance. Employees who choose not to get vaccinated should not slow down the gradual normalization of the work environment as the pandemic slowly subsides.

Conclusions

While some employers might understandably feel hesitant to pressure employees to get vaccinated, our analysis suggests that it is often ethically acceptable to inform, encourage, strongly encourage, incentivize, and subtly pressure unvaccinated people to benefit them, the organization, and other employees. Of course, employers must allow employees to resist encouragement strategies; that is, employees should recognize they may say ‘no’ without important negative consequences. While most strategies discussed above seem relatively unproblematic, the line between resistible pressure and inappropriate harassment or coercion can cause confusion.

Rather than precisely define that line, we think a better approach is to scale encouragement levels to the necessity of having vaccinated employees working in-person. We believe employers can appropriately justify stronger encouragement strategies in a business that requires its employees to work in an environment with other employees present, or with members of the public. Promoting the safety of at-risk co-workers and the broader community is paramount and can support increasing targeted individual encouragement for employees who regularly come into contact with others. There are likely to be cases where unvaccinated employees must be reassigned to different tasks if their refusal to get vaccinated foreseeably endangers colleagues or customers. Conversely, when employees can efficiently complete their work remotely–at home or otherwise in isolation from others–employers may encourage them to get vaccinated for their own sake and the sake of their families and communities. Because vaccination of these employees will have less impact on the workplace, stronger encouragement measures by their employer are not warranted.

It is important to distinguish legal requirements from ethical considerations; given extensive employment regulations, vaccine encouragement might be an issue where law and ethics do not align. Particularly when legal precedents are not clear, companies may choose to focus on minimizing legal risks. While this is understandable, we believe employers should resist that instinct because ethically defensible vaccine encouragement strategies are available. Using them may help improve individual welfare, public health, and economic recovery from this unprecedented pandemic.

Acknowledgements

The views herein are the authors’ and do not represent the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services or the National Institutes of Health.

Biographies

Benjamin E. Berkman

JD, MPH, is a faculty member in the NIH Department of Bioethics, Bethesda, Maryland, USA.

Skye A. Miner

PhD, is an Associate Professor in the Department of Medical Humanities and Bioethics at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, Arkansas, USA.

David S. Wendler

PhD, is a faculty member in the NIH Department of Bioethics, Bethesda, Maryland, USA.

Christine Grady

MSN, PhD, is the Chief of the NIH Department of Bioethics, Bethesda, Maryland, USA.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center and the Intramural Research Program of the National Human Genome Research Institute.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Menni C, Klaser K, May A, Polidori L, Capdevila J, Louca P, Sudre CH, Nguyen LH, Drew DA, Merino J, Hu C. Vaccine side-effects and SARS-CoV-2 infection after vaccination in users of the COVID Symptom Study appin the UK: a prospective observational study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3830769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ivory D, Smith M, Lee J.C., Walker A.S., Gamio L, Holder J, Lu D, Watkins D, Hassan A, Allen J, Lemonides A, Bao B, Brown E, Burr A, Cahalan S, Craig M, De Jesus Y, Dupre B, Guggenheim B, Harvey B, Higgins L, Lim A, Matthews A.L., Moffat-Mowatt J, Pope L, Queen C.S., Rodriguez N, Ruderman J, Saldanha A, Thorp B, White K, Wong BG, Yoon J. See how vaccinations are going in your county and state. New York Times [Internet]. 2022 February 25 [cited 2022 February 25]; Interactive. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/covid-19-vaccine-doses.html

- 3.Mendez R. Most U.S. companies will require proof of Covid vaccination from employees, survey finds [Internet]. CNBC; 2021 April 29 [cited 2021 May 26]. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/04/29/most-us-companies-will-require-proof-of-covid-vaccination-from-employees-survey.html?campaign_id=154&emc=edit_cb_20210430&instance_id=30075&nl=coronavirus-briefing®i_id=81555328&segment_id=56986&te=1&user_id=f3f79d5d0bbf165ef86ec157fb530842

- 4.CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Essential Workers COVID-19 Vaccine Toolkit [Internet]. CDC; 2021 May 20 [cited 2021 May 26]. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/toolkits/essential-workers.html

- 5.CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Workplace Vaccination Program [Internet]. CDC; 2021 Nov. 4 [cited 2022 Feb. 25]. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/recommendations/essentialworker/workplace-vaccination-program.html

- 6.Reiss D.R., Cohen I.G., Shachar C. ‘Authorization’ status is a red herring when it comes to mandating Covid-19 vaccination [Internet]. STAT News; 2021 April 5 [cited 2021 May 26]. https://www.statnews.com/2021/04/05/authorization-status-covid-19-vaccine-red-herring-mandating-vaccination

- 7.Lynch H.F., Persad G. Yes, it’s legal for businesses and schools to require you to get a coronavirus vaccine. Washington Post [Internet]. 2021 May 4 [cited 2021 May 26]; Outlook. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2021/05/04/vaccine-mandate-legal-schools-businesses

- 8.Friedman G, Hirsch L. Health Advocate or Big Brother? Companies Weigh Requiring Vaccines. New York Times [Internet]. 2021 May 7 [cited 2021 May 26]; Business. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/07/business/companies-employees-vaccine-requirements.html

- 9.EEOC (U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission). Harassment [Internet]. EEOC; [cited 2021 May 26]. https://www.eeoc.gov/harassment

- 10.Reuters Staff. Amazon starts on-site COVID-19 vaccination for U.S. employees [Internet]. Reuters; 2021 March 25 [cited 2021 May 26]. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-amazon-com-vaccine/amazon-starts-on-site-covid-19-vaccination-for-u-s-employees-idUSKBN2BH317

- 11.Largent EA, Miller FG. Problems with paying people to be vaccinated against COVID-19. JAMA. 2021;325(6):534–535. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.27121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Savulescu J. Good reasons to vaccinate: mandatory or payment for risk? J Med Ethics. 2021;47(2):78–85. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2020-106821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rutschman AS, Wiemken TL. The case against monetary behavioral incentives in the context of COVID-19 vaccination. Harv Public Health Rev. 2021; 27.

- 14.Wertheimer A, Miller FG. Payment for research participation: a coercive offer? J Med Ethics. 2008;34(5):389–392. doi: 10.1136/jme.2007.021857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vavreck L. $100 as Incentive to Get a Shot? Experiment Suggests It Can Pay Off. New York Times [Internet]. 2021 May 4 [cited 2021 May 10]; TheUpshot. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/04/upshot/vaccine-incentive-experiment.html?referringSource=articleShare

- 16.Blum R. MLB to relax virus protocols when 85% on field vaccinated [Internet]. ABC News; 2021 March 29 [cited 2021 May 26]. https://abcnews.go.com/Sports/wireStory/mlb-relax-virus-protocols-85-field-vaccinated-76753731