ABSTRACT

Flexible portfolio training (FPT) is a novel Royal College of Physicians’ training scheme developed in 2019 to tackle issues of burnout, retention and recruitment among medical registrars. Awareness of the FPT scheme may be lacking and this article intends to inform potential future FPT trainees and their supervisors.

Open to applicants at the time of appointment to higher specialty training, the FPT scheme protects up to 20% of total training time for trainees to pursue an area of interest in one of four pathways (medical education, quality improvement, clinical informatics and research) without extending time to achieve their certificate of completion of training (CCT). Training numbers remain limited and are only available in certain areas across England and Wales. This article explores the benefits of FPT including medical scholarship, flexibility of time and flexible development of personal learning outcomes and objectives and, crucially, improved wellbeing.

The experience of FPT trainees and example projects from those on the medical education pathway in the East Midlands suggest that the scheme can address some of the concerns identified in the future doctor report, potentially sustaining trainees through specialty training, preventing stress and burnout as well as propelling individuals towards lifelong and rewarding careers.

KEYWORDS: medical registrar, training, medical education, flexible portfolio training

Introduction

The job of the medical registrar has long been described as one of the hardest of all medical posts.1 While the reasons are numerous, individuals consistently report experiencing stress or burnout, with a significant impact on retention and recruitment within general internal medicine as well.2–4 There has been a reduction in the number of core medical trainees moving directly into registrar training, with personal life including burnout and mental health being one of the three main reasons for taking a break.5 The Royal College of Physicians (RCP) and Health Education England (HEE) have introduced flexible portfolio training (FPT) as an innovative response to preventing this attrition as well as protecting individual wellbeing.6 The essence of the scheme is quite simple: 20% of ‘training’ time is provided to undertake non-clinical activities such as research, clinical informatics, quality improvement or medical education.

Given that FPT is novel, awareness about it may be lacking, preventing trainees from considering the option as a viable alternative for them after having already invested a significant amount of training into becoming a consultant. Here, we describe FPT as a concept, as well as a training programme, and then focus on the medical education pathway in the East Midlands to demonstrate the diversity of opportunity available to trainees. The aim is to inform trainees, but also trainers who may be unaware of the scheme, and who may be supervising individuals that could benefit from the flexibility as part of their training programme.

Flexible portfolio training

Conventional higher specialty training programmes in the UK involve trainees working up to 48 hours per week on average, typically including shift work and night-time working. Since 2019, trainees on an FPT scheme have had up to 20% of total training programme time protected to develop a non-clinical interest of their choice. Training numbers on this pilot remain limited. Currently, there are four non-clinical themed pathways available across England and Wales: clinical informatics, medical education, quality improvement and research.7 Briefly, the clinical informatics pathway encourages digital literacy and innovation by analysing, designing, implementing and evaluating information and communication systems. The quality improvement pathway encourages trainees to design, manage and facilitate QI projects, and the research pathway may inspire a systematic review or generation of preliminary data for a research proposal. The medical education pathway will be discussed in greater depth later in this article. Themed pathways are paired with a clinical specialty in particular regions, with typically only one FPT placement offered to each participating specialty per year (Table 1). The RCP provides national support for the scheme through a growing library of resources, networking opportunities and themed online lectures.

Table 1.

List of available posts and their coupled specialties8

| Flexible portfolio training pathway theme | Deanery region | Specialties taking part |

|---|---|---|

| Medical education | East Midlands | Acute medicine Endocrinology Renal Respiratory |

| West Midlands | Acute medicine Endocrinology |

|

| Kent, Surrey and Sussex | Geriatric medicine | |

| Quality improvement | East of England | Acute medicine Geriatric medicine Renal |

| South west | Acute medicine Geriatric medicine Endocrinology Respiratory |

|

| Wales | Endocrinology | |

| Clinical informatics | North west | Geriatric medicine Endocrinology Gastroenterology Renal Respiratory Rheumatology |

| Wessex | Acute medicine Geriatric medicine Endocrinology Renal Respiratory Haematology |

|

| North east | Acute medicine Geriatric medicine Infectious diseases |

|

| Research | Yorkshire and Humber | Acute medicine Geriatric medicine Endocrinology |

Enrolment to the FPT scheme occurs at the time of appointment into higher specialty training through the national recruitment programme, where prospective applicants preferentially rank the FPT option during application. The majority of FPT posts are in ‘hard to recruit to’ regions and have had the desired effect of boosting trainee numbers locally.6 FPT is also only available to trainees pursuing dual accreditation in general internal medicine alongside their chosen clinical sub-specialty. Trainees create a personal development plan with their FPT supervisor at the start of each year and upload evidence to their e-portfolio of any presentations, documents or reflections, along with an FPT supervisor report and 360° feedback, which is reviewed at their annual review of competency progression (ARCP) to ensure engagement and progress within their FPT pathway. During the year, interim meetings should assess progress and facilitate exchange of formative feedback and reflections on learning. Should a trainee voluntarily wish to leave the FPT scheme, they can return to full-time standard clinical training in a similar way to a trainee returning from an out-of-programme experience (OOPE) following discussions with their supervisor.

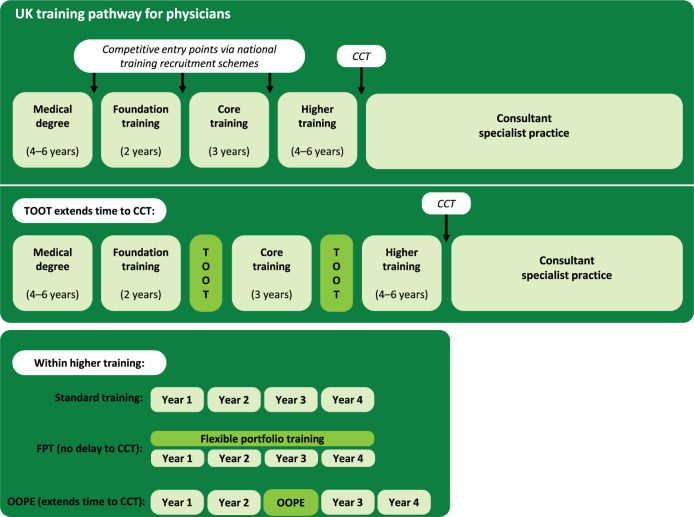

In comparison to other non-conventional training routes, there is no increase in total training time (Fig 1). Therefore, trainees are still expected to achieve all their clinical competencies, but in the remaining 80% of the standard training time. Trainees are also expected to provide a full contribution to on-call rotas including out-of-hours working. Therefore, potential FPT candidates should be organised and prepared to achieve all required competencies in a more limited time frame.

Fig 1.

Comparison of medical career pathways. CCT = certificate of completion of training; FPT = flexible portfolio training; OOPE = out-of-programme experience; TOOT = time out of training.

Less-than-full-time (LTFT) trainees can apply for FPT if they work 70% full-time equivalent (FTE) or more. Their complimentary pathway still occupies 20% FTE, therefore, their minimum contribution to clinical training would be 50% FTE. There are no implications on parental leave, as with specialty training, FPT is paused during maternity and paternity leave. The information provided is correct at the time of writing, however, as a pilot scheme still in its infancy, it is subject to change. For the most up-to-date guidance, please see the frequently asked questions (FAQs) section of the RCP website (www.rcplondon.ac.uk/education-practice/advice/flexible-portfolio-training-faqs).

Previously, trainees seeking development opportunities outside clinical training could take ‘time out of training’ (TOOT) in between different stages of their medical career or would have to gain permission for an OOPE. Such posts are often advertised as fellowships, though a variety of job titles can be used (Box 1). The exact professional development opportunities offered by fellowships vary by employing organisation, though often involve similar themes to FPT. However, unlike FPT, these standalone posts extend the time needed for trainees to achieve a certificate of completion of training (CCT; Fig 1). FPT also offers additional benefits over fellowship posts in that there is the opportunity to work with organisations for a longer period, given the duration of FPT in comparison.

Box 1.

Common job titles of time out of training and out-of-programme experience posts

| F3 doctor |

| Senior house officer |

| Trust grade |

| Staff grade |

| Middle grade doctor |

| Clinical fellow |

| Teaching fellow |

| Research fellow |

| Chief registrar |

| Specialty doctor |

Benefits of FPT training

Medical scholarship training

Medical scholarship capabilities are increasingly recognised as important for future doctors, and particularly general physicians.9,10 However, research has also identified a need for bringing greater clarity around the development of these capabilities within training programmes.4,11 The future doctor report commissioned by HEE identified these key medical scholarship skills as critical appraisal of evidence, clinical policy development, research, and lifelong learning, teaching and education, which all map onto the earlier themed pathways.11 Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the benefits of a workforce equipped with scholarship capabilities, namely individuals with the ability to continue critical frontline research alongside delivering safe and effective clinical care, and cross-disciplinary teams able to connect remotely and continue delivering education using a variety of innovative technologies.11

To employers and trusts

Trusts and employers may benefit from reduced rota gaps if they can recruit to FPT posts that may otherwise by vacant by offering more attractive training opportunities to applicants than the standard higher specialty training posts. FPT trainees are also likely to engage in work within their pathway that can benefit the trust through service improvements, innovative changes and improved patient care.7

Flexibility of time

A more flexible approach, in the way time is formally allocated across a training programme, allows trainees the autonomy to vary their personal time allocation and mitigate acute spikes in other workloads, such as around the time of professional exams when focusing on personal learning or during busy periods when working on their FPT project. Up to 20% of total training time can be taken for FPT work, which roughly equates to one day a week across the training programme offering trainees a continual dual focus throughout training.6 Alternatively, the scheme offers trainees the flexibility to take the equivalent time less frequently as larger blocks throughout the year if their project requires such an arrangement.

Flexibility of learning objectives

FPT is also an innovative way of individualising training and gives autonomy to trainees to personalise their learning for meeting their educational needs. The FPT component of the scheme encourages personal goal setting, a core skill for being able to engage in lifelong learning, reflective practice and high performance in general. In this regard, there is no pre-defined learning objectives, rather, individuals are empowered to self-identify potential outputs, use various strategies for achieving these and manage personal time accordingly for completing project tasks. Furthermore, conversations with educational supervisors are also different from traditional ones where there is more of a monologue from teacher to learner; instead, there is much more of a dialogue between both parties around a learners’ personal and professional development.

Flexibility of learning outcomes

As a consequence of flexible learning objectives, the range of acceptable learning outcomes can be equally broad. Trainees can complete a portfolio of small projects over successive years or develop a progressive programme of work over time. The existing grouping of themes across HEE regions enables both the development of a critical mass of local trainees and expertise, but also the opportunity for individuals to choose to work independently on projects or within teams. Likewise, the theming by region, rather than individual training hospital, allows the trainee to experience opportunities beyond traditional employer or institutional boundaries; for example, quality improvement projects can be scaled over a region rather than just across a single setting, and medical education projects can be cross-continuum including both under- and postgraduate training, rather than either one in isolation.

Wellbeing

One of the drivers for developing FPT was the rising number of trainees, in particular medical registrars, experiencing both stress and burnout, and the benefits described earlier all come together in a way that may improve wellbeing. An in-depth exploration of the experience of medical registrars revealed multiple challenges for individuals in the role.12 The benefit of 20% of protected project time balanced with 80% clinical time was hoped to improve both the way trainees functioned but also, crucially, the way they felt as medical registrars. In particular, a greater sense of self-perception, meaning and satisfaction was hoped from the programme as a whole, complementing a greater sense of connection to others, purpose and personal growth for the trainee themselves. Driving most of these benefits is likely to be the greater autonomy and control over themselves afforded to FPT trainees, especially when considering traditional training programmes offer little of these in comparison such as factors of choice of daily tasks, start–finish times and work–life balance in general.

Medical education and the East Midlands

There are three regions offering medical education themed FPT: East and West Midlands both with two cohorts so far since 2019, and Kent, Surrey and Sussex with one cohort since 2020. With each new intake, the number of new projects has increased, and existing projects have actively benefited from additional trainees, as well as individuals from near-peer mentoring of each other. Trainees in the East Midlands have benefited from a supportive approach from the HEE School of Medicine in the East Midlands. There is an FPT lead within the school to provide overall oversight at a programme level and pastoral support for personal and professional development to trainees at an individual level. In particular, trainees are given support to develop their own ideas for medical education innovations, and also deliver them region-wide by leveraging the FPT lead's professional network. Specifically related to medical education, FPT trainees are encouraged to go beyond just delivering teaching but consider first and foremost their development across the various roles of a teacher.13 With respect to projects, FPT trainees are supported to develop innovations that demonstrate awareness of curriculum design and technology-enhanced learning (Box 2).14

Box 3.

Examples of East Midlands' flexible portfolio training educational projects

| Creation of online open access educational resources including reading lists, and curriculum-mapped lecturer guides for regional teaching programmes. |

| ‘MEMcast’: a rolling educational podcast series including interviews with regional expert physicians. |

| Assisting the regional training programme director in implementing the new national internal medicine training stage 1 curriculum, replacing core medical training. |

| Working with local college tutors to develop a new simulation programme for general medicine procedural skills. |

| Engaging with the national director of IMPACT and assisting with a UK-wide curriculum redesign.14 |

| COVID-19 educational and wellbeing support programmes for redeployed workforce during the pandemic. |

FPT trainees may consider obtaining a formal postgraduate medical education qualification (eg a postgraduate certificate, diploma or Master's), however, registration is not automatic by virtue of being on the scheme. More and more trainees within FPT or, indeed, those trainees in teaching fellow posts enrol onto such programmes, however, pursuing a formal qualification may not be either desirable or suit the circumstances of the individual. That said, alignment of the FPT project and research conducted by the trainee as part of a Master's qualification can significantly enhance the both the quality and quantity of output for the trainee. Furthermore, collaborating with university medical education departments also provide trainees with further insights into academic medical careers and opportunities to engage in clinical education research.15 Finally, partnership with HEE East Midlands allows FPT trainees to develop themselves as future educational leaders demonstrating the power of this scheme to provide a complete training experience.

Conclusion

FPT is an innovative way of individualising postgraduate medical education and enabling trainees to self-direct their personal and professional development. FPT is different from conventional higher specialty training by protecting up to 20% of the total training programme time to develop a non-clinical interest. This allows parallel development of clinical and non-clinical interests. The four established themes include clinical informatics, medical education, quality improvement and research. FPT is offered alongside higher specialty training in general internal medicine. Arguably most importantly for the trainee, the scheme provides both autonomy and opportunity for individuals to self-direct their ongoing personal and professional development prior to obtaining their CCT. FPT is not just an ‘add-on’ or mechanism for providing extra-curricular experiences, but more natural evolution of training programmes for individuals with a strong sense of direction in their careers.

Successful FPT programmes are more likely when trainees are able to self-regulate their own learning underpinned by educational supervisors creating educational environments with sufficient support and opportunities. The experience of trainees is likely to be further enhanced where there is sufficient flexibility for the trainee to personalise training time around their individual personal and professional circumstances. The experience of FPT trainees and example projects in the East Midlands suggests the scheme can address some of the concerns identified in the future doctor report, potentially sustaining trainees through specialty training, preventing stress and burnout as well as propelling individuals towards lifelong and rewarding careers. There is evaluative research currently ongoing into the experiences of FPT programme. Further research will be required to demonstrate the long-term impact on retention and the mental wellbeing of FPT trainees.

References

- 1.Grant P, Goddard A. The role of the medical registrar. Clin Med 2012;12:12–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Public Health England . Facing the facts, shaping the future. PHE, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Health Education England . Enhancing junior doctors’ working lives: Annual progress report 2020. HEE, 2020. www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/EJDWL_Report_June%2020%20FINAL.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hautz SC, Hautz WE, Feufel MA, et al. What makes a doctor a scholar: a systematic review and content analysis of outcome frameworks. BMC Med Educ 2016;16:119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roycroft M, Abad-Madroñero J, Cochrane C, et al. ‘This is my vocation; is it worth it?’ Why do core medical trainees break from training? FHJ 2020;7(Suppl 1):S103–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Royal College of Physicians . Flexible portfolio training: A handbook for trainees and supervisors. RCP, 2020. www.rcplondon.ac.uk/file/25176/download [Google Scholar]

- 7.Royal College of Physicians . Flexible portfolio training. RCP. www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/flexible-portfolio-training [Google Scholar]

- 8.Royal College of Physicians . Flexible portfolio training pathways. RCP. www.rcplondon.ac.uk/file/25151/download [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shape of Training Review . Securing the future of excellent patient care: final report of the independent review. General Medical Council, 2013. www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/Shape_of_training_FINAL_Report.pdf_53977887.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reeve J. Scholarship-based medicine: teaching tomorrow's generalists why it's time to retire EBM. Br J Gen Pract 2018;68:390–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Health Education England . The future doctor programme. HEE. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaudhuri E, Mason NC, Logan S, Newbery N, Goddard AF. The medical registrar: Empowering the unsung heroes of patient care. Royal College of Physicians, 2013. www.rcplondon.ac.uk/file/medical-registrar-empowering-unsung-heroes-patient-care [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harden RM, Crosby J. AMEE Guide No 20: The good teacher is more than a lecturer - the twelve roles of the teacher. Med Teach 2000;22:334–7. [Google Scholar]

- 14.IMPACT . Ill medical patients’ acute care & treatment. IMPACT. [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Institute for Health Research . Clinical education incubator. NIHR, 2020. www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/clinical-education-incubator/24887 [Google Scholar]