ABSTRACT

Introduction

A new UK medical postgraduate curriculum prompted the creation of a novel national medical postgraduate ‘boot camp’. An enhanced simulation-based mastery learning (SBML) methodology was created to deliver procedural skills teaching within this national boot camp. This study aimed to explore the impact of SBML in a UK medical boot camp.

Methods

One-hundred and two Scottish medical trainees attended a 3-day boot camp starting in August 2019. The novel enhanced SBML pathway entailed online pre-learning resources, deliberate practice, and simulation assessment and feedback. Data were gathered via pre- and post-boot camp questionnaires and assessment checklists.

Results

The vast majority of learners achieved the required standard of performance. Learners reported increased skill confidence levels, including skills not performed at the boot camp.

Conclusion

An enhanced SBML methodology in a boot camp model enabled streamlined, standardised procedural skill teaching to a national cohort of junior doctors. Training curricular competencies were achieved alongside increased skill confidence.

KEYWORDS: medical education, internal medicine, procedural skills, junior doctor, boot camp

Introduction

Competence in invasive procedural skills is required to progress through postgraduate medical training, but such procedures present potential risks to patients.1,2 To mitigate these risks, junior doctors need the appropriate training and opportunities to develop their procedural skills. Postgraduate medical trainees have reported difficulties in obtaining sufficient experience of procedural skills due to changes in work scheduling, clinical service demands and reduced specialty opportunities.3–7 This negatively impacts on their ability to achieve curricular requirements and adequate expertise in procedural skills. If trainees are unable to perform procedural skills, this also has patient safety implications as it may cause delays in diagnosis and treatment.8

The traditional adage of ‘see one, do one, teach one’ for medical procedural skill education is now regarded as sub-optimal and outdated.9 Simulation-based mastery learning (SBML) has a strong evidence base supporting its use in procedural skill acquisition.10 SBML is founded upon the principles of competency-based education whereby all learners attain a standardised level of achievement for the assessed skill. The traditional SBML methodology typically consists of three phases: learner pre-testing to establish baseline skill; an educational phase incorporating training, tutor demonstration and learner deliberate practice; and learner re-testing to establish skill competency.11 SBML methodology has been used mostly in American learner populations, with minimal literature describing its use in the UK. Building upon the established USA-based SBML methodology, the Medical Education Directorate of NHS Lothian has implemented an enhanced SBML pathway.12,13 The initial NHS Lothian adapted programme removed the pre-test component and teaching during the session, and replaced this with asynchronous pre-learning resources. These materials provide the learner with procedural and conceptual (technical and non-technical) knowledge prior to physical rehearsal of the skill and must be completed prior to the SBML procedural skills laboratory session.

In August 2019, a new curriculum was introduced in the UK for all physician trainees, named Internal Medicine Training (IMT).1 This training programme typically commences 2 years after medical school graduation, following the 2-year mandatory Foundation Programme. Trainees in the prior training scheme described difficult clinical transition into the role, due to increasing clinical responsibilities without supportive training.3,4,6,7,14 The 2019 IMT curriculum mandates a range of procedural skill competencies, with evidence of training at simulation-laboratory level required by the end of the first year.1 Simulation has been shown to be previously unavailable for medical trainees in some UK regions.4

To improve training and address some of the new curriculum requirements, Scotland implemented a novel, national IMT ‘boot camp’ that embraced simulation and workshop methodology. Educational boot camp programmes are recognised as effective and efficient tools for acquisition of clinical skills, knowledge and confidence due to their rich, intensive learning environments. They are particularly valuable for challenging transition stages in clinical careers.14–16 Most boot camps occur outside the UK, but some have recently been successfully implemented for UK and Irish surgical trainees.16 At the time of writing, the authors were unaware of any previous medical boot camps in the UK, or of the use of SBML in existing boot camps.

The NHS Lothian SBML pathway was further adapted for the national medical boot camp. The enhanced blended principles of SBML methodology included the established asynchronous pre-learning, but also introduced synchronous peer-assisted deliberate practice immediately prior to assessment and peer learning observation in a 2:1 learner to teacher ratio at each station.12 The enhanced SBML was piloted in the boot camp to deliver mastery learning in four procedural skills: lumbar puncture (LP), ascitic aspiration and drain (ascitic procedures), and intercostal drain (ICD) to all Scottish medical trainees. To our knowledge, this is the first use of SBML in any UK national postgraduate initiative.

Study aims

To identify the learning needs of postgraduate medical trainees in Scotland in relation to procedural skills.

To explore the educational value of an enhanced SBML methodology embedded within a boot camp model in relation to trainees’ learning needs.

Methods

The boot camp

All 106 Scottish IMT trainees were invited to attend a 3-day immersive boot camp that was delivered as six sessions, between August 2019 and January 2020, at the Scottish Centre for Simulation and Clinical Human Factors at Forth Valley Royal Hospital, Larbert, UK. Approximately 18 trainees attended each 3-day boot camp. Faculty varied at each boot camp, and included a range of consultants, specialty registrars and teaching fellows. Trainee attendance was strongly encouraged and study leave to attend was facilitated by NHS Education for Scotland.

Each boot camp day involved three parallel 2-hour strands: SBML of procedural skills, immersive simulated acute care scenarios and communication workshops. Day 1 also included a 60-minute session on aseptic technique that involved a video-based tutorial and hands-on rehearsal with facilitator feedback. A comprehensive guide and schedule of the IMT boot camp is available on the Scotland Deanery website.17

Questionnaire and analysis

Each learner completed pre- and post-boot camp questionnaires (supplementary material S1 and S2). The pre-event questionnaire identified key individual learning needs for the boot camp (free text) and previous experience of the individual procedures. The questionnaires also measured pre- and post-event ratings of confidence using a Likert scale (1 = not at all confident to 7 = completely confident) for procedures performed at boot camp (LP, ascitic procedures and ICD) and ‘control procedures’ not taught at boot camp (nasogastric tube insertion and central venous catheterisation).

The free-text key learning needs were assessed for themed content: general mention of practical procedural skills and individually named procedures (LP, ascitic procedures and ICD). The pre- and post-event confidence data were matched and statistically analysed via a paired t-test. As this included multiple hypotheses testing across different procedures, a Bonferroni correction was applied to adjust the significance threshold to p<0.008.

Simulation-based mastery learning

The novel enhanced SBML pathway included mandatory asynchronous pre-learning materials, peer-assisted deliberate practice, checklist-based assessment and simultaneous peer observation. The pre-learning materials consisted of comprehensive reading packs (detailing non-technical aspects including safety and decision-making considerations) and videos demonstrating each skill; these were hosted on NHS Lothian open access Medical Education Directorate website.13 All learners were advised of the mandatory pre-learning components several weeks prior to their course.

The in-person training was a 2-hour session for each skill. One tutor worked with two learners at an anatomical simulation model, with three sets of tutors/learners within each session. Each session started with peer-assisted deliberate practice, with the tutor observing and assisting as required. Each learner was then assessed and given feedback, with the partner observing.

Assessment was performed using the NHS Lothian SBML checklist (supplementary material S3) with set minimum passing standards for each skill. Each procedure checklist was created and standard set by subject matter experts using mastery-modified Angoff methodology.18 This involves, for each item of an agreed checklist, experts imagining a group of well-prepared learners and considering what proportion of this group would ‘pass’ the item. Following discussion of individual responses within the expert group, each expert submits their final answers and a mean score of the items in the checklist becomes the overall ‘pass’ score. Each procedure checklist follows an NHS Lothian mastery standardised framework with the phases ‘preparation, assistance and positioning’, ‘procedural pause’, ‘asepsis and anaesthetic’, ‘insertion’, ‘anchoring and dressing’ and ‘completion’. Learners could have a repeat attempt under observation if they failed the first assessment and time allowed. The trainees who did not achieve the required level of competency were supported to attend further simulation opportunities in their local area. Those achieving the mastery standard were recorded after each session and sent certified evidence post-boot camp. Successful learners were encouraged to subsequently perform the procedures in clinical practice, under direct supervision.

The study was approved by the NHS Education for Scotland Research Ethics Service, reference number NES/Res/14/20/Med. All data were anonymised prior to analysis and trainees were free to withdraw from the study at any time.

Results

One-hundred and two trainees attended the boot camp. One questionnaire was incomplete, giving 101 complete data sets. Of these, 56 (55%) learners identified as women, 43 (43%) identified as men with the remainder (n=2) preferring not to categorise their gender. Eighty-five per cent of learners were aged between 24–29 years old, 14% were between 30–35 years old and 1% were aged over 36 years old.

Learning needs in relation to procedural skills

The pre-boot camp questionnaire included a free-text box for learners to state their key learning aim for the boot camp. Ninety-three per cent of learners described a personal learning need that included procedural skills. A proportion of learners named specific skills: 24% mentioned ICD, 8% LP and 6% ascitic procedures.

Table 1 shows the percentage of learners who had performed each procedure prior to attendance at boot camp, categorised in groups. Of the procedures taught at boot camp (LP, ascitic procedures and ICD), 7% of the learners had never performed any of them on real patients prior to boot camp. A further 25% reported that they had not done any procedure more than three times. Trainees reported the least experience with ICDs: over 75% had never inserted one. LP was the most commonly performed procedure, with 33% having performed it seven or more times prior to boot camp.

Table 1.

Each procedure performed in clinical practice (% of total) by learners prior to boot camp, n=101

| Never | 1–3 times | 4–6 times | 7–10 times | >10 times | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performed at boot camp | |||||

| Lumbar puncture | 13 | 31 | 24 | 12 | 21 |

| Ascitic aspiration | 31 | 40 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Ascitic drain | 40 | 32 | 13 | 6 | 10 |

| Intercostal drain | 76 | 20 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Not performed at boot camp | |||||

| Nasogastric tube | 9 | 49 | 21 | 5 | 17 |

| Central venous catheterisation | 76 | 17 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

The educational value of SBML

All learners met the required mastery standard for LP and ascitic procedures, with 96% achieving the required level for ICD.

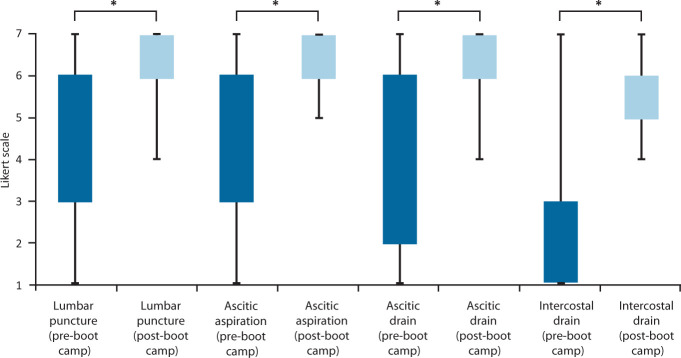

Fig 1 and Table 2 show the means of the self-reported confidence of the learners. Learners showed significantly increased skill-specific confidence levels for all procedures performed in boot camp (p<0.001; t-test). ICD had the lowest pre-boot camp confidence level at 2.4±1.3 but this increased significantly to 5.9±0.9 post-boot camp (p<0.001). For procedures not taught at boot camp, central venous catheterisation also showed significant improvement in post-confidence (2.18±1.9; p=0.004) and nasogastric tube insertion showed improvement.

Fig 1.

Learner confidence levels pre- and post-simulation-based mastery learning procedural session. The ‘box’ indicates the interquartile range and the ‘whiskers’ show the full range of results. * = p<0.001.

Table 2.

Self-reported confidence pre- and post-boot camp (Likert scale)

| Mean (SD) pre-boot camp | Mean (SD) post-boot camp | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Performed at boot camp | |||

| Lumbar puncture | 4.58 (1.8) | 6.32 (0.8) | <0.001 |

| Ascitic aspiration | 4.57 (1.9) | 6.55 (0.6) | <0.001 |

| Ascitic drain | 4.00 (2.0) | 6.35 (0.7) | <0.001 |

| Intercostal drain | 2.40 (1.3) | 5.90 (0.9) | <0.001 |

| Not performed at boot camp | |||

| Nasogastric tube | 5.32 (1.7) | 5.59 (1.6) | 0.343 |

| Central venous catheterisation | 2.10 (1.5) | 2.81 (1.9) | 0.004 |

SD = standard deviation.

Discussion

This study describes the procedural learning needs of postgraduate medical trainees in Scotland, and the educational impact of an enhanced SBML pathway embedded within a boot camp model. It is the first study to describe such findings in the context of a national medical boot camp. Procedural skills are key components in doctors’ skillsets, but UK medical trainees have previously reported limited opportunities to perform procedures.3,4 With very few exceptions, learners achieved the training programme curricular requirements and gained confidence in the taught skills.

In a boot camp with a wide-ranging curriculum, the majority of learners stated that their personal key learning objective was to improve their procedural skills. There was a wide range of trainee exposure to different procedural skills prior to boot camp, with nearly a third having had minimal clinical exposure to the skills covered. They had less experience with the more clinically complex procedures. The range in procedural experience seen in this study perhaps reflects the leaners’ varied clinical experience; some may have come directly from the UK foundation training, or they may have worked in a range of clinical posts for several years prior to commencing IMT. Even within the compulsory Foundation Programme, each doctor obtains varied clinical experience and opportunity to practise procedural skills. This may depend on the specialty, available patients, and time available to observe or to attempt the procedures.

Multiple studies have shown a variation in junior doctor procedural skill exposure and at more senior levels of training.4–6,19–21 A recent UK-wide survey of 871 IMT-level trainees found that, even by the end of their 2-year programme, 20% had never performed abdominal drains independently and 57% had never performed ICD insertion independently.4 Our findings correlate with this; ICDs had the lowest pre-boot camp confidence level and lowest level of clinical experience. ICDs are acknowledged to have greater potential clinical risks and, as a result, have become more limited in availability for trainees.22

A follow-up report by the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh to the UK survey findings listed possible solutions to help increase exposure of medical trainees to clinical skills.3 In the report, the onus is placed on trainees to arrange and capitalise on opportunities, arguably applying additional pressure to an already stressful role. Some trainees have implemented innovative short-term adaptations to assist with the acquisition of procedural skills.23,24 However, a centrally organised and supported teaching programme, such as this boot camp, is key to ensure accessible and standardised training for all.

The learners reported statistically significant increased confidence in all the procedural skills performed at boot camp. Learners then progressed into the clinical environment, boosted with confidence, re-accessible resources and a standardised foundation of knowledge and skill, to then be able to perform the procedure clinically under supervision. Trainees were provided with evidence of competency for their training portfolio after attending the boot camp. No other boot camp or SBML sessions in the literature provide curricular evidence for the procedural skill learning achievement. Providing certification should provide assurance for the trainees, knowing that they have acquired the curricular requirement for their end-of-year assessment; focus can then instead return to furthering clinical competency.

Interestingly, learners also reported increased confidence in skills not taught or performed at boot camp (Table 2), with significant increase found for central venous catheterisation. Given the complexity of the boot camp model, it cannot be said for certain what has contributed to these results. It could be argued that the overall immersive experience of a 3-day boot camp, with collegiality and global confidence boosting, has created increased general self-confidence in all aspects of the role. However, it is possible that the increase in confidence in skills not directly taught is a product of the enhanced SBML methodology that provides a robust and transferrable framework for skill acquisition and rehearsal.

The concept of skill transfer between procedural skills is not well explored in the literature. Transfer of learning is the application of skills learnt in one situation to another context.25 It is assumed that the learner will transfer aspects learnt into their subsequent experiences.26 In simulation research, this is usually the skill transfer from simulation to clinical practice; transfer between skills is not yet explored.25 Current contemporary instructional design for procedural skills tends to focus on how to deliver the technical aspect of the skill, rather than its context. Cheung et al have investigated how to gain maximal educational impact from SBML, including examining skill retention and transfer.26,27 Conceptual knowledge has been consistently shown to underlie expertise development and skill transfer.26 They found that teaching procedural skills with conceptual (‘why’) as well as procedural (‘how’) knowledge increases learner retention and skill transfer.27 Issenberg et al state that repetition and defined outcomes help to facilitate learning in SBML.28 Marker et al also reported that final-year medical students found that structured tools from simulation teaching helped them to feel more prepared for clinical practice.29

The enhanced SBML methodology in the boot camp has introduced components that have added conceptual understanding and a structured tool for procedural skills. The mandatory pre-learning materials emphasise conceptual and safety aspects relevant to every skill, prior to commencing the technical element. The enhanced SBML method also introduces a standardised checklist that divides each procedural skill into identical sections that also emphasise non-technical and safety aspects of the skill. The consistent framework approach to each skill lessens the cognitive load and provides a transferable structure that can be applied to any procedure. Each day at boot camp builds on knowledge and complexity, allowing repetition and reinforced learning of the standardised framework throughout the boot camp. There may be an unconscious transfer of knowledge and skills when repeatedly using this structured SBML framework approach at boot camp.

Limitations

As different tutors assisted each day, there may be inter-rater differences; this has since been mitigated with the implementation of a standardised faculty development pathway. Self-reported confidence levels are used and it is recognised that such ratings do not reflect competence.21 However, we measure self-reported confidence on a simulation model. It is intended to provide our trainees with confidence and a structured approach to optimise attainment of procedural skills on a model, to then facilitate the transition to real clinical practice. It is not meant as a replacement to real clinical experience, nor as a measurement of clinical competency. We instead use passing the standardised assessment as the measurement of their simulation-based competence. It is likely that possessing increased confidence and accessible educational resources will ease the progression to clinical situations.

Future work

Further studies will follow-up these learners and their performance of these procedures following boot camp. Kerins et al have performed a qualitative study exploring the factors that influence the transfer of learning from boot camp to the clinical workplace.30 Further studies are investigating the individual change in confidence following boot camp, as well as the subsequent opportunities for clinical practice. Importantly, as data collection for this study was completed before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is acknowledged that the pandemic has likely disrupted trainees’ clinical placements and procedural experience. In response to this, booster skill sessions have been introduced and the impact of these on skill maintenance is being studied. Future work should also explore the translation of this learning into real-life performance of skills and the associated clinical impact in terms of patient, economic and healthcare organisational outcomes.

Conclusion

Medical trainees have learning needs requiring experience in procedural skills. A novel, national boot camp facilitated over 100 medical trainees to attain simulation-based curricular requirements on mandatory procedural skills. The boot camp used enhanced SBML methodology to provide a supported and structured approach for learning procedural skills. Learner confidence increased in all procedures covered at boot camp and extended to some procedures not included. This suggests some elements of the standardised methodology may be transferrable across a range of procedural skills. Overall, the programme has provided medical doctors in training with centrally-organised opportunities to learn procedural skills in a safe environment.

Summary

What is known?

UK postgraduate medical trainees are describing difficulty in attaining experience in clinical procedures.

Boot camps are rich learning programmes to facilitate acquisition of skills, knowledge and confidence. These often feature simulation to enhance learning for trainees.

Simulation-based mastery learning (SBML) is a wellestablished methodology that facilitates the acquisition of procedural skills; but it is not widely used in the UK.

What is the question?

To identify the learning needs of postgraduate medical trainees in Scotland in relation to procedural skills.

To explore the educational value of an enhanced SBML methodology embedded within a boot camp model in relation to trainees' learning needs.

What was found?

Ninety-three per cent of the learners reported a learning need for procedural skills.

A national cohort of UK junior doctor demonstrated simulation-based competency in a range of complex procedural skills via this methodology.

These learners reported significantly increased confidence in procedural skills as well as others not directly taught at boot camp.

The learners also obtained training curricular requirements on procedural skills.

What is the implication for practice now?

This is the first reported national postgraduate medical boot camp.

The standardised SBML approach provides a structured technical and non-technical approach for any procedural skill.

Our data support the role of SBML for procedural skill acquisition for UK-based trainees.

Supplementary material

Additional supplementary material may be found in the online version of this article at www.rcpjournals.org/clinmedicine:

S1 – Pre-boot camp questionnaire.

S2 – Post-boot camp questionnaire.

S3 – NHS Lothian simulation-based mastery learning checklist: ascitic aspiration skill.

References

- 1.Joint Royal Colleges of Physicians Training Board . Curriculum for internal medicine: stage 1 training. JRCPTB, 2019. www.jrcptb.org.uk/sites/default/files/IM_Curriculum_Sept2519.pdf [Accessed 17 April 2021]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akram AR, Hartung TK. Intercostal chest drains: A wake-up call from the National Patient Safety Agency rapid response report. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2009;39:117–20. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tasker F, Dacombe P, Goddard AF, Burr B. Improving core medical training - Innovative and feasible ideas to better training. Clin Med 2014;14:612–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tasker F, Newbery N, Burr B, Goddard AF. Survey of core medical trainees in the United Kingdom 2013 - Inconsistencies in training experience and competing with service demands. Clin Med 2014;14:149–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lim CT, Gibbs V, Lim CS. Invasive medical procedure skills amongst Foundation Year Doctors - a questionnaire study. JRSM Open 2014;5:2054270414527934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mason NC, Chaudhuri E, Newbery N, Goddard AF. Training in general medicine - Are juniors getting enough experience? Clin Med 2013;13:434–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Royal College of Physicians . The medical registrar: Empowering the unsung heroes of patient care. RCP, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sonnenberg A, Crain BR. Scheduling medical procedures: How one single delay begets multiple subsequent delays. J Theor Med 2005;6:235–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lenchus JD. End of the “see one, do one, teach one” era: The next generation of invasive bedside procedural instruction. J Am Osteopath Assoc 2010;110:340–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McGaghie WC, Issenberg SB, Cohen ER, Barsuk JH, Wayne DB. Does simulation-based medical education with deliberate practice yield better results than traditional clinical education? A meta-analytic comparative review of the evidence. Acad Med 2011;86:706–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barsuk JH, Cohen ER, Caprio T, McGaghie WC, Simuni T, Wayne DB. Simulation-based education with mastery learning improves residents’ lumbar puncture skills. Neurology 2012;79:132–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scahill EL, Oliver NG, Tallentire VR, Edgar S, Tiernan JF. An enhanced approach to simulation-based mastery learning: optimising the educational impact of a novel, National Postgraduate Medical Boot Camp. Adv Simul 2021;6:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Medical Education Directorate . The mastery skills pathway. MED, 2020. www.med.scot.nhs.uk/simulation/the-mastery-programme [Accessed 15 November 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cleland J, Patey R, Thomas I, Walker K, O’Connor P, Russ S. Supporting transitions in medical career pathways: the role of simulation-based education. Adv Simul 2016;1:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blackmore C, Austin J, Lopushinsky SR, Donnon T. Effects of postgraduate medical education “boot camps” on clinical skills, knowledge, and confidence: a meta-analysis. J Grad Med Educ 2014;6:643–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walker KG, Blackhall VI, Hogg ME, Watson AJM. Eight years of Scottish surgical boot camps: how we do it now. J Surg Educ 2020;77:235–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tallentire V. IMT1 boot camp information for trainees. Scotland Deanery, 2021. www.scotlanddeanery.nhs.scot/trainee-information/internal-medicine-training-imt-simulation-programme/imt1-boot-camp-information [Accessed 21 November 2021]. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barsuk JH, Cohen ER, Wayne DB, McGaghie WC, Yudkowsky R. A comparison of approaches for mastery learning standard setting. Acad Med 2018;93:1079–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garrood T, Iyer A, Gray K, et al. A structured course teaching junior doctors invasive medical procedures results in sustained improvements in self-reported confidence. Clin Med 2010;10:464–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vijayakumar B, Kitt J, Hynes G, Millette S, Fitzpatrick M. Procedural skills training for medical registrars – is it needed? FHJ 2020;7(Suppl 1):s110–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Connick RM, Connick P, Klotsas AE, Tsagkaraki PA, Gkrania-Klotsas E. Procedural confidence in hospital based practitioners: Implications for the training and practice of doctors at all grades. BMC Med Educ 2009;9:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corcoran JP, Hallifax RJ, Talwar A, Psallidas I, Sykes A, Rahman NM. Intercostal chest drain insertion by general physicians: Attitudes, experience and implications for training, service and patient safety. Postgrad Med J 2015;91:244–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shafei R. Better training, better care: medical procedures training initiative. BMJ Qual Improv Reports 2014;2:u203119.w1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nana M, Morgan H. Improving ‘The Core’ aspects of medical training: a trainee-led innovation. FHJ 2020;7:90–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamstra SJ, Brydges R, Hatala R, Zendejas B, Cook DA. Reconsidering fidelity in simulation-based training. Acad Med 2014;89:387–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheung JJH, Kulasegaram KM, Woods NN, Brydges R. Why content and cognition matter: integrating conceptual knowledge to support simulation-based procedural skills transfer. J Gen Intern Med 2019;34:969–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheung JJH, Kulasegaram KM, Woods NN, et al. Knowing how and knowing why: testing the effect of instruction designed for cognitive integration on procedural skills transfer. Adv Heal Sci Educ 2018;23:61–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Issenberg SB, Mcgaghie WC, Petrusa ER, Gordon DL, Scalese RJ. Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: a BEME systematic review. Med Teach 2005;27:1,10–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marker S, Mohr M, Østergaard D. Simulation-based training of junior doctors in handling critically ill patients facilitates the transition to clinical practice: an interview study. BMC Med Educ 2019;19:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kerins J, Smith SE, Stirling SA, Wakeling J, Tallentire VR. Transfer of training from an internal medicine boot camp to the workplace: enhancing and hindering factors. BMC Med Educ 2021;21:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]