PURPOSE

Promising single-agent activity from sotorasib and adagrasib in KRASG12C-mutant tumors has provided clinical evidence of effective KRAS signaling inhibition. However, comprehensive analysis of KRAS-variant prevalence, genomic alterations, and the relationship between KRAS and immuno-oncology biomarkers is lacking.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Retrospective analysis of deidentified records from 79,004 patients with various cancers who underwent next-generation sequencing was performed. Fisher's exact test evaluated the association between cancer subtypes and KRAS variants. Logistic regression assessed KRASG12C comutations with other oncogenes and the association between KRAS variants and immuno-oncology biomarkers.

RESULTS

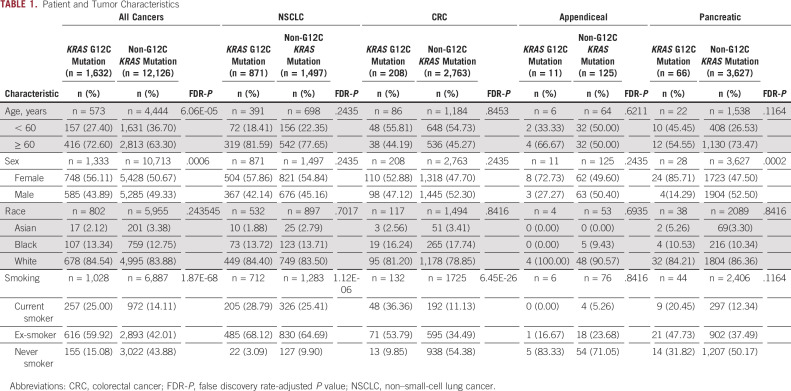

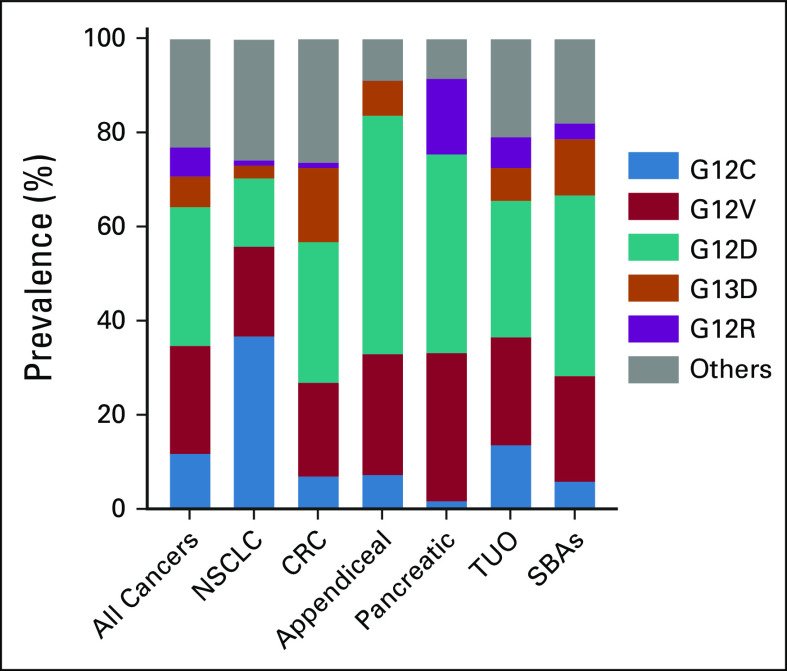

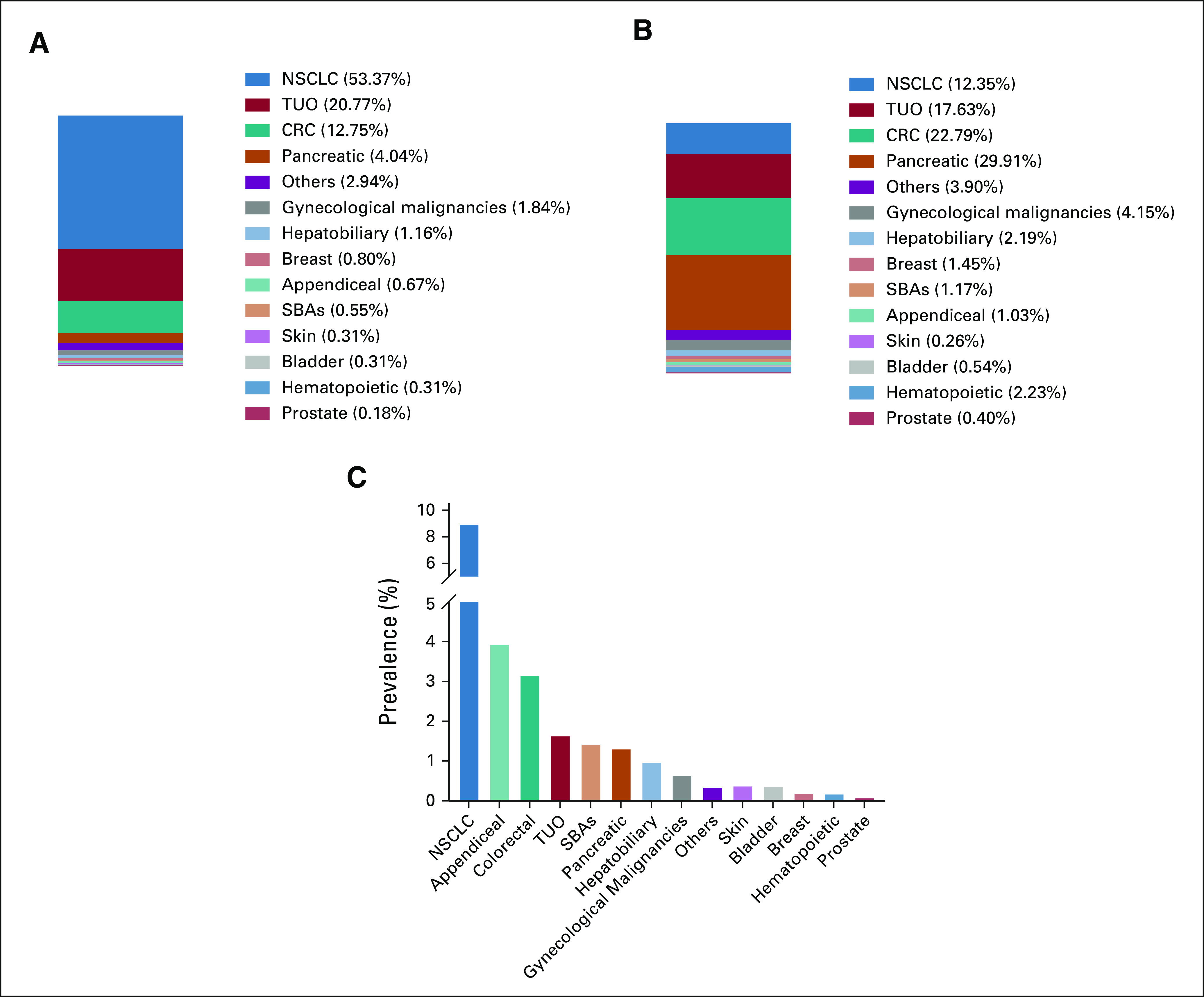

Of the 79,004 samples assessed, 13,758 (17.4%) harbored KRAS mutations, with 1,632 (11.9%) harboring KRASG12C and 12,126 (88.1%) harboring other KRAS variants (KRASnon-G12C). Compared with KRASnon-G12C across all tumor subtypes, KRASG12C was more prevalent in females (56% v 51%, false discovery rate-adjusted P value [FDR-P] = .0006), current or prior smokers (85% v 56%, FDR-P < .0001), and patients age > 60 years (73% v 63%, FDR-P ≤ .0001). The most frequent KRAS variants across all subtypes were G12D (29.5%), G12V (23.0%), G12C (11.9%), G13D (6.5%), and G12R (6.2%). KRASG12C was most prevalent in patients with non–small-cell lung cancer (9%), appendiceal (3.9%), colorectal (3.2%), tumor of unknown origin (1.6%), small bowel (1.43%), and pancreatic (1.3%) cancers. Compared with KRASnon-G12C-mutated, KRASG12C-mutated tumors were significantly associated with tumor mutational burden-high status (17.9% v 8.4%, odds ratio [OR] = 2.38; FDR-P < .0001). KRASG12C-mutated tumors exhibited a distinct comutation profile from KRASnon-G12C-mutated tumors, including higher comutations of STK11 (20.59% v 5.95%, OR = 4.10; FDR-P < .01) and KEAP1 (15.38% v 4.61%, OR = 3.76; FDR-P < .01).

CONCLUSION

This study presents the first large-scale, pan-cancer genomic characterization of KRASG12C. The KRASG12C mutation was more prevalent in females and older patients and appeared to be associated with smoking status. KRASG12C tumors exhibited a distinct comutation profile and were associated with tumor mutational burden-high status.

INTRODUCTION

Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS) is the most common driver oncogene in human cancers; it is an essential mediator of tumor cell growth and survival1 and is often associated with poor outcomes.2,3 More than three decades of efforts to target KRAS downstream signaling pathways in KRAS-mutated cancers have largely been ineffective.4

CONTEXT

Key Objective

What is the prevalence of KRASG12C and associated genomic alterations, and what is the relationship between KRASG12C mutation status and immune-related biomarkers?

Knowledge Generated

Among 79,004 patients, KRASG12C was more often identified in females, current or prior smokers, and older patients. KRASG12C was most prevalent in patients with non–small-cell lung cancer, appendiceal, colorectal, tumor of unknown origin, small bowel, and pancreatic cancers. KRASG12C tumors were genomically distinct from KRASnon-G12C tumors, including variations in STK11, KEAP1, and other gene frequencies. TMB-high was strongly associated with tumors harboring KRASG12C.

Relevance

KRASG12C tumors exhibited a distinct comutation profile from KRASnon-G12C tumors. Additionally, tumor mutational burden-high status was associated with KRASG12C tumors, suggesting a potential role for combination strategies with immunotherapy. These results may guide future therapeutic strategies.

The recent development of KRASG12C-selective inhibitors of GTP binding—locking KRAS in an inactive state5,6—established a foundation for the development of inhibitors suitable for clinical testing and reignited interest in this historically undruggable target. Promising single-agent activity from AMG510 (sotorasib) and MRTX849 (adagrasib) in KRASG12C-mutant tumors, especially in non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and colorectal cancer (CRC), has provided the first clinical evidence of KRAS-mutant tumor inhibition7-9 and led to the subsequent US Food and Drug Administration breakthrough therapy designation for sotorasib in locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC. Four other KRASG12C inhibitors (JNJ-74699157, JDQ443, GDC-6036, and LY3499446) have now entered the clinic.

Beyond single-gene alterations such as KRASG12C, there are various broad genomic biomarkers associated with treatment response or resistance in patients with cancer, many of which are interrelated. Recent evidence suggests clinically relevant interactions between RAS mutations and immuno-oncology (IO) biomarkers.10,11 However, the extent of relationships between microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H)/mismatch repair deficient status, tumor mutational burden (TMB), programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1), and KRAS mutations remains unclear.

Here, we analyzed next-generation sequencing (NGS) data from patients with various cancer subtypes to characterize the prevalence of KRASG12C and other KRAS variants, identify associated genomic alterations, and describe the relationship between KRAS mutation status and IO biomarkers, which may provide guidance for future therapeutic strategies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical Data

Clinical data were extracted from the Tempus Labs (Chicago, IL) real-world oncology database, as previously described12 (Data Supplement).

NGS Profiling of Tumor Samples

Tumor samples were clinically profiled at a College of American Pathologists-accredited, Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments-certified laboratory (Tempus Labs, Chicago, IL) using a single platform. Tissue-based NGS with the Tempus xT laboratory developed test was performed on DNA and RNA isolated from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor samples using the NovaSeq and HiSeq platforms (Illumina, San Diego, CA), similar to previously described methods12,13 (Data Supplement).

IO Markers

Records included for assessment of IO biomarkers were restricted to baseline tissue samples profiled with the Tempus xT assay. TMB, MSI, and PD-L1 expression analyses are reported in the Data Supplement.14,15

Statistical Analysis

Chi-square tests were used to evaluate associations between KRASG12C status and patient demographic variables. Logistic regression analyzed associations between cancer subtypes and KRAS variants, associations between KRAS variants and IO biomarkers, and comutations between KRAS G12C and other oncogenes. To control false discovery rate (FDR) because of multiple testing, the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure16 was used to calculate FDR-adjusted P value (FDR-P), with FDR-P < .05 considered statistically significant. All analyses were completed with SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Ethics Statement

All data were deidentified in accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act before investigation and granted institutional review board oversight exemption (Pro00042950).

RESULTS

Patient and Tumor Characteristics

From 79,004 tumor samples analyzed, 13,758 KRAS-mutated tumors were identified from various cancer types (Data Supplement). Of these, 1,632 (11.9%) tumors harbored the KRASG12C variant while 12,126 harbored other KRAS variants (KRASnon-G12C; Table 1 and Data Supplement). An overview of demographics and clinical characteristics stratified by KRASG12C mutation status is summarized in Table 1. When compared with KRASnon-G12C across all tumor subtypes, KRASG12C was more often identified in females (56% v 51%; FDR-P = .0006), current or prior smokers (85% v 56%; FDR-P < .0001), and patients older than 60 years (73% v 63%; FDR-P < .0001).

TABLE 1.

Patient and Tumor Characteristics

KRAS-Variant Distribution

The most frequent KRAS variants across all tumors analyzed were G12D (29.5%), G12V (23.0%), G12C (11.9%), G13D (6.5%), and G12R (6.2%). However, the distribution of KRAS variants significantly differed by cancer type (Fig 1 and Data Supplement).

FIG 1.

Prevalence of KRAS variants by tumor subtype. Most common KRAS mutation variants observed in all KRAS-mutated tumors (n = 13,758) and subtypes. CRC, colorectal cancer; NSCLC, non–small-cell lung cancer; SBA, small bowel adenocarcinoma; TUO, tumor of unknown origin.

Within the KRASG12C-mutated cohort, NSCLC had the highest prevalence (53%), followed by tumors of unknown origin (TUO; 21%) and CRC (13%; Fig 2A). In contrast, within the KRASnon-G12C cohort, pancreatic tumors had the highest KRAS mutation prevalence (30%), followed by CRC (23%) and TUO (18%; Fig 2B). A complete list of pan-cancer KRAS-variant distribution is presented in the Data Supplement.

FIG 2.

Frequency of KRASG12C and KRASnon-G12C by cancer subtypes. (A) Distribution of 1,632 patients with confirmed KRASG12C by tumor subtype. (B) Distribution of 12,126 patients with other confirmed KRAS variants (KRASnon-G12C) by tumor subtype. Cancer subtype distribution was significantly different between G12C and non-G12C KRAS mutation groups (P < .0001). (C) Frequency of KRASG12C mutations in 14 cancer types. CRC, colorectal cancer; NSCLC, non–small-cell lung cancer; SBA, small bowel adenocarcinoma; TUO, tumor of unknown origin.

KRASG12C Distribution

Cancer subtype distribution was significantly different between KRASG12C and KRASnon-G12C mutation groups (P < .0001; Fig 2C). KRASG12C was most prevalent in patients with NSCLC (8.9%), appendiceal cancer (3.9%), CRC (3.2%), TUO (1.6%), small bowel adenocarcinomas (1.4%), and pancreatic cancer (1.3%). Hepatobiliary, hematopoietic, breast, bladder, prostate, and skin cancers had a KRASG12C frequency rate of < 1% each.

In NSCLC, KRASG12C was mostly associated with adenocarcinoma histology compared with squamous cell carcinoma (92.4% v 3.4%, P < .0001). Smoking status was also associated with the presence of G12C among patients with NSCLC harboring KRAS variants (FDR-P < .0001). In CRC, no differences were observed based on age, sex, or race when comparing the KRASG12C versus KRASnon-G12C populations, but smoking status was associated with KRASG12C (FDR-P < .0001).

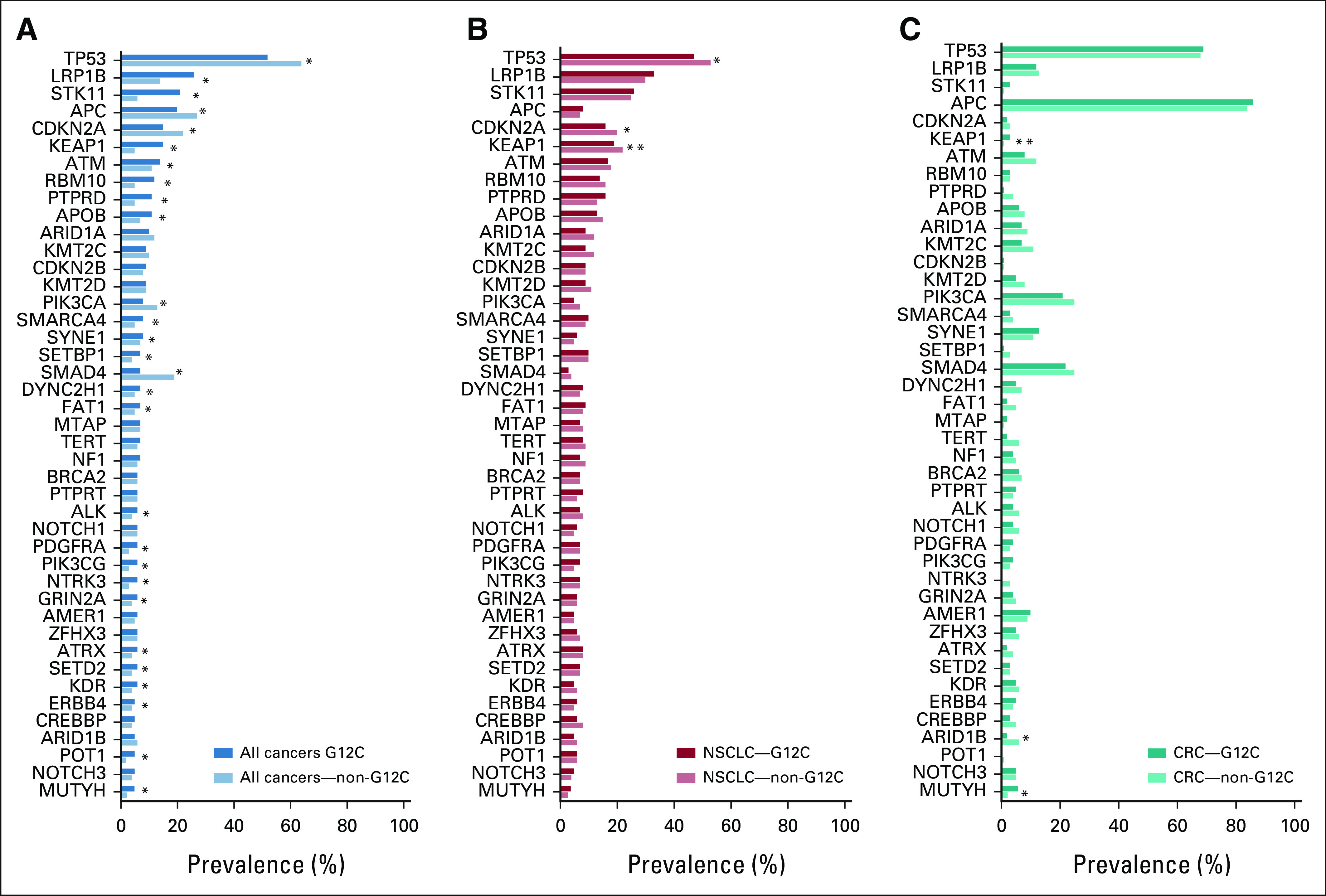

Association Between KRASG12C Mutations and Mutations in Other Oncogenes

Among patients with a confirmed KRAS mutation, tumors harboring KRASG12C exhibited a distinct comutation profile compared with those with KRASnon-G12C mutations (Fig 3).

FIG 3.

Comparison of oncogenic comutations for KRASG12C and KRASnon-G12C cohorts. Comparison of comutations identified in the KRASG12C- and KRASnon-G12C-mutated cohorts. Comutations altered in more than 5% of patients with a confirmed KRAS mutation were included and are shown by subgroups: (A) all cancers, (B) NSCLC, and (C) CRC. Logistic regression was used to calculate the OR and 95% CIs (Data Supplement). FDR-P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Some comutations with KRASG12C in all cancers could be caused by coenrichment of the oncogene mutation and KRASG12C mutation in NSCLC, as described in the Results section. Careful interpretation of the analysis results using the Data Supplement is recommended. *Significant G12C status (KRASG12C and KRASnon-G12C) effect on the mutation of the oncogene in the subgroup (all cancers or NSCLC or CRC) at FDR-P < .05. **Significant G12C status (KRASG12C and KRASnon-G12C) × cancer subtype (NSCLC or CRC) interaction effect on the mutation of the oncogene at FDR-P < .05. CRC, colorectal cancer; FDR-P, false discovery rate-adjusted P value; NSCLC, non–small-cell lung cancer; OR, odds ratio.

For instance, STK11 (20.59% v 5.95%, odds ratio [OR] = 4.10), KEAP1 (15.38% v 4.61%, OR = 3.76), and MUTYH (4.96% v 2.35%, OR = 2.17) were more frequently mutated in KRASG12C-mutant tumors across all cancer types (P < .001 and FDR-P < .01 for all comparisons). Meanwhile, SMAD4 (7.23% v 19.05%, OR = 0.33), TP53 (52.39% v 64.25%, OR = 0.61), CDKN2A (15.44% v 22.37%, OR = 0.63), and PIK3CA (8.03% v 12.59%, OR = 0.61) were less frequently mutated in KRASG12C compared with KRASnon-G12C-mutant tumors (P < .0001 and FDR-P < .0001 for all comparisons). Notably, although none of the tumors harboring KRASG12C exhibited BRAFV600E comutations, BRAFnon-V600E comutations were observed in 3.1% of KRASG12C-mutant tumors. Since some other mutations (eg, STK11 and KEAP1) are enriched in NSCLC and the KRASG12C mutation is also enriched in NSCLC, the association between these genes and KRASG12C may be caused by the coenrichment in NSCLC rather than a true association across all tumors. Therefore, to rule out comutation because of coenrichment in NSCLC, we further stratified the comutation analysis according to patients with and without NSCLC (Data Supplement).

In CRC, MUTYH (5.77% v 2.28%, OR = 2.62, P = .005 and FDR-P = .027) and ARID1B (1.92% v 6.26%, OR = 0.29, P = .009, and FDR-P = .042) mutational frequencies were significantly different between tumors with KRASG12C versus KRASnon-G12C mutations.

Several genes were found to have significant subtype effects, meaning prevalence of the oncogene mutation was significantly different across cancer subtypes. However, the KRASG12C effect was not significantly different between NSCLC and CRC for most oncogenes evaluated, with only KEAP1 exhibiting different comutation patterns between NSCLC and CRC (FDR-P < .05). A full list of comutations by cancer type is presented in the Data Supplement.

Association Between KRAS-Mutated Versus KRAS Wild-Type Tumors and IO Biomarkers

We examined the association between KRAS mutation status and IO biomarkers (Data Supplement). Compared with KRAS-wild-type (WT) tumors, TMB-high status was less frequent in KRAS-mutated tumors both in the overall cohort (9.48% v 10.51%, OR = 0.89, and FDR-P = .004) and in the CRC cohort (4.68 v 10.34%, OR = 0.43, and FDR-P < .0001). This association was not observed when considering only NSCLC tumors. A similar association was observed between MSI-H and KRAS mutational status both in the overall cohort and CRC. Conversely, in NSCLC, high PD-L1 expression was more frequently observed in KRAS-mutated tumors compared with KRAS-WT (65.3% v 58.5%, OR = 1.34, and FDR-P = .0002).

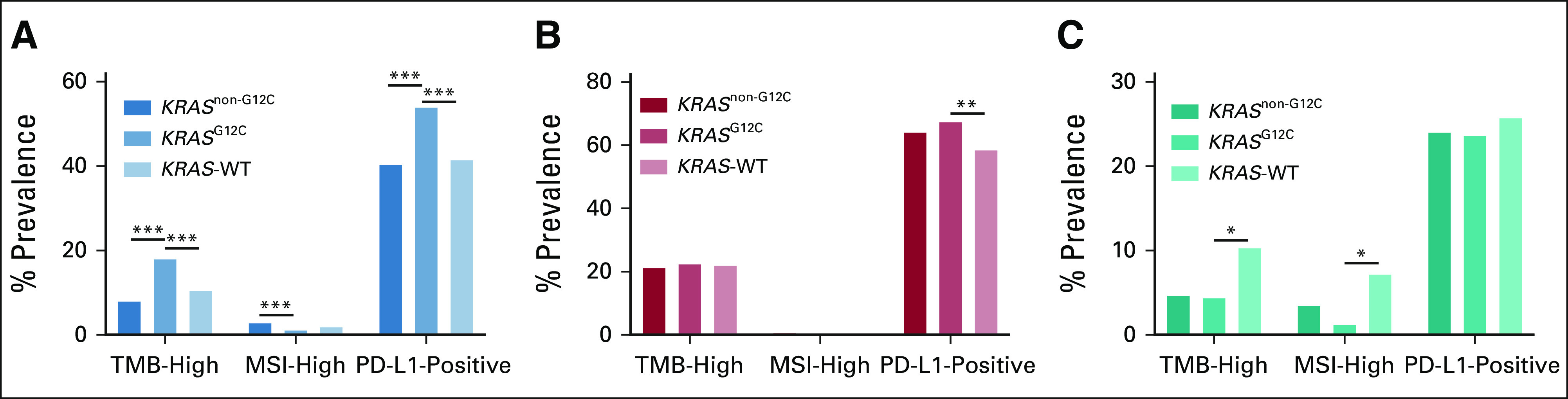

The Association Between KRASG12C, KRASnon-G12C, KRAS WT, and IO Biomarkers

We further stratified the IO biomarker analysis by separating KRASG12C-mutated tumors from those harboring KRASnon-G12C mutations. The relationships between KRAS mutational status (KRASG12C mutations, KRASnon-G12C mutations, and KRAS WT) and IO biomarkers are reported in the Data Supplement. Overall, the frequency of TMB-high status was found to be significantly different between the three KRAS mutation groups (FDR-P < .0001). TMB-high status was more frequently associated with KRASG12C compared with KRAS-WT (17.9% v 10.51%, OR = 1.86) and KRASnon-G12C mutations (17.9% v 8.4%, OR = 2.38) and less frequent in KRASnon-G12C–mutated compared with KRAS-WT tumors (8.40% v 10.51%, OR = 0.78). In CRC, TMB-high status was less frequent in both KRASG12C- and KRASnon-G12C-mutated tumors compared with KRAS-WT tumors (4.40% and 4.70% v 10.34%, OR = 0.3992 and 0.4271, and FDR-P < .0001). The association between TMB-high and KRAS mutation status was not significant when considering only NSCLC (Data Supplement).

A significant association was observed between PD-L1 expression levels and the three KRAS groups (FDR-P < .0001) when including all cancer types. High expression was more frequently associated with KRASG12C compared with KRAS-WT (53.96% v 41.50%, OR = 1.65) and KRASnon-G12C-mutant tumors (53.96% v 40.40%, OR = 1.73) and less frequent in KRASnon-G12C compared with KRAS-WT tumors (40.40% v 41.50%, OR = 0.96). However, in a stratified analysis separately considering patients with and without NSCLC, the high expression of PD-L1 was not significantly different between KRASG12C and KRASnon-G12C mutations in either NSCLC (OR = 1.16, FDR-P = .38) or non-NSCLC tumors (OR = 1.01, FDR-P = .95), suggesting that the significant association between PD-L1 and KRASG12C observed in all cancers was likely due to coenrichment in NSCLC.

In NSCLC, high PD-L1 expression was more frequent in both KRASG12C- and KRASnon-G12C-mutated tumors compared with KRAS-WT tumors (67.53% and 64.17% v 58.54%, OR = 1.47 and 1.27, and FDR-P = .0017 and .0123). A nonsignificant association between high PD-L1 expression and KRAS mutation status was seen in CRC (Fig 4).

FIG 4.

Evaluation of immune biomarkers by KRASG12C, KRASnon-G12C, and KRAS WT. Comparison of TMB-high (defined as > 10 mut/Mb), high PD-L1 expression, and MSI-high cases across three KRAS cohorts (KRASG12C, KRASnon-G12C, and KRAS-WT). The association between PD-L1 and KRASG12C in all cancers could be caused by coenrichment of PD-L1–positive and KRASG12C mutation in NSCLC, as described in the Results section: (A) all cancers, (B) NSCLC, and (C) CRC. FDR-P < .05 was considered statistically significant. ***FDR-P < .0001; **FDR-P ≥ .0001 and FDR-P < .01; *FDR-P ≥ .01 and FDR-P < .05. CRC, colorectal cancer; FDR-P, false discovery rate-adjusted P value; MSI, microsatellite instability; mut/Mb, mutations per megabase; NSCLC, non–small-cell lung cancer; PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1; TMB, tumor mutational burden; WT, wild-type.

Finally, MSI-H status was significantly different across the three KRAS groups in the overall population (FDR-P < .0001). MSI-H was less frequently associated with KRASG12C compared with KRAS-WT (1.17% v 1.92%, OR = 0.63) and KRASnon-G12C-mutated tumors (1.17% v 2.86%, OR = 0.39) and more frequently associated with KRASnon-G12C-mutated when compared with KRAS-WT tumors (2.86% v 1.92%, OR = 1.59; Data Supplement).

DISCUSSION

Despite being the most frequently mutated oncogene in human cancers, therapeutic targeting of KRAS-driven tumors remains a formidable challenge. Several promising KRASG12C inhibitors have now entered the clinic and combination strategies with chemotherapy, immune checkpoint inhibitors, anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) antibodies, and pan-KRAS targeting agents (eg, SOS1 and SHP2 inhibitors) are being explored—holding the potential for transforming clinical management of KRAS-mutated solid tumors. Hence, understanding variations in KRAS mutational frequencies, clinicopathological characteristics, and comutations for KRASG12C tumors across cancer types, as well as their interplay with predictors of response to immune checkpoint inhibitors, may advance the clinical development of KRASG12C inhibitors.

In the current study, we observed distinct patterns in KRAS mutations where the position and type of substitution varied between different cancers. KRASG12C was most frequent in NSCLC and TUOs, suggesting that a large proportion of these TUOs may have originated from the lung. The prevalence within individual cancer subtypes observed in our study was similar to findings from the The Cancer Genome Atlas data set (NCI GDC data portal, v29.0)16 and a recently published study.17

The association between cancer type and KRAS mutational status can be partially explained by tissue-specific differential exposure to mutagens such as tobacco smoke. For example, in lung cancer, the G:C → T:A transversion causing the G12C mutation is predominantly seen in smokers while never smokers are more likely to have a transition mutation (G:C→A:T).18,19 In NSCLC tumors, the KRASG12C variant was almost exclusively detected in tissue from current or former smokers. More intriguing, however, was the striking enrichment of KRASG12C mutations in patients with CRC with a smoking history, which to our knowledge has not been previously reported. Among all CRC cases with KRASG12C mutations, 90% were in current or former smokers while only 46% of KRASnon-G12C mutations were associated with smoking. There was a similar trend in pancreatic cancer (68% v 50%), but the power of this observation is limited by the small number of KRASG12C-mutant cases. Similar to lung cancer, cigarette smoking is linked to an increased risk for CRC albeit with a much more modest association, which likely reflects the tissue-specific differences in exposure to individual tobacco mutagens and the lower prevalence of KRASG12C mutations in CRC.20,21 Accumulating evidence indicates that the smoking-related risk in CRC may be limited to molecularly defined subsets, with several studies reporting that smoking is associated with increased risk of BRAF-mutated and MSI-H CRC but not BRAF-WT, MSS, or KRAS-mutant tumors.22-26 Previous studies26-28 have not found an overall association between smoking variables and CRC tumors with transversion or transition mutations in KRAS; however, these studies are limited by the small number of patients who had identified KRAS mutations, challenges with the accuracy of tobacco use documented in medical records, and lack of post hoc analyses correlating smoking status with discrete KRAS point mutations. Given that KRAS mutations are all not created equal, where various mutations have been shown to impart unique biochemical effect and different oncogenic signaling, it is plausible that the causal link to tobacco may be limited to certain KRAS mutations.

Direct KRASG12C inhibitors undoubtedly represent a major leap forward for the treatment of KRAS-mutant cancers; however, a predicted challenge to their clinical development is the high degree of biological heterogeneity in these tumors, which is likely to affect therapeutic response to KRAS inhibition. In NSCLC, objective response rates from early-phase studies with KRASG12C inhibitors were lower than agents targeting EGFR-activating mutations or ALK-RET fusions.29,30 This suggests greater biological diversity and oncogenic pathway redundancy in KRASG12C-mutant tumors compared with tumors driven by other oncogenes. Furthermore, co-occurrence of KRAS mutations with other oncogenes such as TP53 and CDKN2A in various cancers, KEAP1 and STK11 in lung adenocarcinoma, or APC and PIK3CA in CRC, may influence therapeutic response.31,32 Overall, we found significantly higher comutation rates between KRASG12C and several other oncogenes compared with KRASnon-G12C-mutant tumors, although these differences were not observed in the NSCLC and CRC cohorts. Specifically, we observed similar comutation patterns between KRASG12C- and KRASnon-G12C-mutant NSCLC for key oncogenes LRP1B, STK11, KEAP1, and CDKN2A but a lower comutation rate with TP53. Lung cancer cells with KRAS/LRP1B comutation have been reported to be sensitive to HSP90 inhibitors,31 and tumors with KRAS/TP53 comutation have demonstrated increased PD-L1 expression and a remarkable clinical benefit to pembrolizumab.33 Additionally, preclinical work with adagrasib suggests that KRASG12C- /STK11-mutated NSCLC could be targeted with a combination of KRASG12C inhibition and an RTK or mTOR inhibitor, whereas KRASG12C- /CDKN2A-mutated NSCLC could be more effectively treated by combination with a CDK4/6 inhibitor.34 Collectively, this suggests that the role of comutation should be considered in clinical trials targeting KRASG12C-mutant tumors.

In the phase I clinical trial, the overall response rate in CRC with sotorasib alone was limited at 7.1%. The results of progression-free survival in CRC were also worse than those observed in NSCLC.35 Consistent with this, Amodio et al36 observed that KRASG12C inhibitors produce less profound and more transient inhibition of KRAS downstream signaling in CRC compared with NSCLC models. Akin to targeting BRAFV600E CRC with BRAF inhibitors, EGFR signaling rebound was also found to be the dominant mechanism of CRC resistance to KRASG12C inhibition. Of clinical relevance, targeting both EGFR and KRASG12C was highly effective in preclinical CRC models. This combinatorial approach is currently being explored in several phase I-III trials (NCT04793958, NCT04449874, NCT03785249, and NCT04185883). As with most targeted treatments, primary or acquired resistance to these combination therapies will be the rule rather the exception. Understanding comutation patterns in KRASG12C-mutant CRC may shed light on further therapeutic strategies. Here, similar to other reports,37,38 we observed a statistically significant association between KRASG12C and MUTYH (5.8% v 2.3%, OR: 2.62 [1.26-5.01]) and between KRASG12C and ARID1B (1.9% v 6.3%, OR: 0.29 [0.08-0.78], compared with KRASnon-G12C-mutant CRC. However, we did not observe a lower comutation rate for NOTCH3 or PIK3CA in KRASG12C-mutated CRC, as reported recently by Henry et al.39 In our cohort, PIK3CA mutations were found in 21% of KRASG12C-mutated CRC. Cotargeting PI3K and MEK/ERK signaling in KRAS-mutant tumors has emerged as a promising therapeutic strategy in preclinical studies, but successful clinical development of this combination has been hampered by dose-limiting toxicities.40

There has been substantial interest in the interaction between specific molecular changes and the immune system. Despite the strong association with smoking, we did not observe a difference in the frequency of TMB-high tumors between KRASG12C-mutant, KRASnon-G12C-mutant, and KRAS-WT NSCLC; in fact, we found a surprisingly lower frequency of TMB-high status in KRASG12C-mutant compared with KRAS-WT CRC. Overall, KRASG12C tumors had higher frequencies of PD-L1 positivity than KRASnon-G12C-mutant and KRAS-WT tumors. In NSCLC, the higher frequency was maintained when comparing KRASG12C and KRAS-WT tumors. Arbor et al recently reported a higher median PD-L1 expression in KRASG12C- vs. KRASnon-G12C-mutated NSCLC, but similar to our study, the proportion of patients with PD-L1–positive expression (TPS ≥ 1%) was similar in KRASG12C- and KRASnon-G12C-mutated patients.18 Preclinical models demonstrated that treating KRASG12C-mutant tumors with sotorasib resulted in proinflammatory tumor microenvironments that were highly responsive to immune checkpoint inhibition (ICI),41 underpinning the rationale for ongoing trials combining KRASG12C inhibitors and ICI (NCT04613596, NCT03785249, NCT04185883, and NCT04449874). Whether dual KRASG12C and ICI will be more efficacious than ICI alone in PD-L1–positive KRASG12C-mutant NSCLC remains to be seen.

Treatment and outcome data were not available for the entirety of this data set, limiting the correlation between molecular subsets and treatment-specific outcomes. There was also missing information on patient age and race, which may limit the power to detect any statistical difference in these variables between KRASG12C- and KRASnon-G12C–mutated cancers. We used a TMB cutoff of 10 mut/Mb to define TMB-high versus TMB-low across all tumor types, but the optimal threshold to identify a cancer as TMB-high for ICI treatment selection remains the subject of much debate.

In conclusion, to our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive analysis of KRASG12C distribution, associated comutations, PD-L1 expression levels, and TMB in a pan-cancer data set. KRASG12C mutation rates varied widely among different cancer types. Tumor mutational burden-high was strongly associated with tumors harboring KRASG12C, which could potentially help identify additional responders to ICI plus KRASG12C inhibitor combination treatment. These findings provide baseline data for the prevalence of molecular and histologic parameters potentially associated with responsiveness to KRASG12C inhibitors in several malignancies.

Mohamed E. Salem

Consulting or Advisory Role: Taiho Pharmaceutical, Exelixis, Bristol Myers Squibb, Exelixis, QED Therapeutics, Novartis, Pfizer

Speakers' Bureau: Taiho Pharmaceutical, Daiichi Sankyo/Astra Zeneca, BMS, Merck

Sherif M. El-Refai

Employment: Tempus

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Tempus

Axel Grothey

Honoraria: Elsevier, Aptitude Health, IMEDEX

Consulting or Advisory Role: Genentech/Roche, Bayer (Inst), Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst), Lilly (Inst), Boston Biomedical (Inst), Amgen (Inst), Array BioPharma (Inst), Daiichi Sankyo (Inst), OBI Pharma

Research Funding: Genentech/Roche (Inst), Bayer (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Eisai (Inst), Lilly (Inst), Boston Biomedical (Inst), Daiichi Sankyo (Inst), Array BioPharma (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Genentech/Roche, Bayer

Thomas J. George

Consulting or Advisory Role: Tempus, Pfizer

Research Funding: Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst), Merck (Inst), AstraZeneca/MedImmune (Inst), Lilly (Inst), Bayer (Inst), Incyte (Inst), Ipsen (Inst), Seattle Genetics (Inst), Genentech (Inst), Astellas Pharma (Inst), BioMed Valley Discoveries (Inst), GlaxoSmithKline (Inst),

Open Payments Link: https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/physician/321938

Jimmy J. Hwang

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Caris Centers of Excellence, Pfizer, QED Therapeutics, Deciphera, Incyte

Speakers' Bureau: Bristol Myers Squibb, Deciphera, Incyte

Research Funding: Caris Centers of Excellence (Inst), Boehringer Ingelheim (Inst).

Bert O'Neil

Employment: Lilly, Tempus

Honoraria: AstraZeneca

Alexander S. Barrett

Employment: Tempus

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Tempus

Derek Raghavan

Consulting or Advisory Role: Gerson Lehrman Group, Caris Life Sciences (Inst).

Eric Van Cutsem

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bayer, Lilly, Roche, SERVIER, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Merck KGaA, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Halozyme, Array BioPharma, Biocartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Daiichi Sankyo, Pierre Fabre, Sirtex Medical, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Incyte, Astellas Pharma

Research Funding: amgen (Inst), Bayer (Inst), Boehringer Ingelheim (Inst), Lilly (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Roche (Inst), Celgene (Inst), Ipsen (Inst), Merck (Inst), Merck KGaA (Inst), SERVIER (Inst), Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst).

Josep Tabernero

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Lilly, MSD, Merck Serono, Novartis, Sanofi, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Peptomyc, Chugai Pharma, Pfizer, Seattle Genetics, Array BioPharma, AstraZeneca, Genentech, Menarini, Servier, HalioDx, F. Hoffmann LaRoche, Mirati Therapeutics, Pierre Fabre, Tessa Therapeutics, TheraMyc, Daiichi Sankyo, Samsung Bioepis, IQvia, Ikena Oncology, Merus, Neophore, Orion Biotechnology, Hutchison MediPharma, Avvinity, Scandion Oncology, Ona Therapeutics, Sotio Biotech, Inspirna Inc

Other Relationship: Imedex, Medscape, MJH Life Sciences, Peerview, Physicans' Education Resource

Jeanne Tie

Honoraria: SERVIER, Inivata

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca/MedImmune, Bristol Myers Squibb, Pierre Fabre, MSD Oncology, Inivata, Haystack Oncology

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

DATA SHARING STATEMENT

A data sharing statement provided by the authors is available with this article at DOI https://doi.org/10.1200/PO.21.00245.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Mohamed E. Salem, Sherif M. El-Refai, Derek Raghavan, Josep Tabernero, Jeanne Tie

Administrative support: Mohamed E. Salem, Derek Raghavan

Collection and assembly of data: Mohamed E. Salem, Sherif M. El-Refai, Wei Sha, Alberto Puccini, Alexander S. Barrett

Data analysis and interpretation: Mohamed E. Salem, Sherif M. El-Refai, Wei Sha, Alberto Puccini, Axel Grothey, Thomas J. George, Jimmy J. Hwang, Bert O'Neil, Alexander S. Barrett, Kunal C. Kadakia, Laura W. Musselwhite, Eric Van Cutsem, Josep Tabernero, Jeanne Tie

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

Provision of study materials or patients: Mohamed E. Salem, Sherif M. El-Refai, Jimmy J. Hwang, Josep Tabernero

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/po/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Mohamed E. Salem

Consulting or Advisory Role: Taiho Pharmaceutical, Exelixis, Bristol Myers Squibb, Exelixis, QED Therapeutics, Novartis, Pfizer

Speakers' Bureau: Taiho Pharmaceutical, Daiichi Sankyo/Astra Zeneca, BMS, Merck

Sherif M. El-Refai

Employment: Tempus

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Tempus

Axel Grothey

Honoraria: Elsevier, Aptitude Health, IMEDEX

Consulting or Advisory Role: Genentech/Roche, Bayer (Inst), Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst), Lilly (Inst), Boston Biomedical (Inst), Amgen (Inst), Array BioPharma (Inst), Daiichi Sankyo (Inst), OBI Pharma

Research Funding: Genentech/Roche (Inst), Bayer (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Eisai (Inst), Lilly (Inst), Boston Biomedical (Inst), Daiichi Sankyo (Inst), Array BioPharma (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Genentech/Roche, Bayer

Thomas J. George

Consulting or Advisory Role: Tempus, Pfizer

Research Funding: Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst), Merck (Inst), AstraZeneca/MedImmune (Inst), Lilly (Inst), Bayer (Inst), Incyte (Inst), Ipsen (Inst), Seattle Genetics (Inst), Genentech (Inst), Astellas Pharma (Inst), BioMed Valley Discoveries (Inst), GlaxoSmithKline (Inst),

Open Payments Link: https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/physician/321938

Jimmy J. Hwang

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Caris Centers of Excellence, Pfizer, QED Therapeutics, Deciphera, Incyte

Speakers' Bureau: Bristol Myers Squibb, Deciphera, Incyte

Research Funding: Caris Centers of Excellence (Inst), Boehringer Ingelheim (Inst).

Bert O'Neil

Employment: Lilly, Tempus

Honoraria: AstraZeneca

Alexander S. Barrett

Employment: Tempus

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Tempus

Derek Raghavan

Consulting or Advisory Role: Gerson Lehrman Group, Caris Life Sciences (Inst).

Eric Van Cutsem

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bayer, Lilly, Roche, SERVIER, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Merck KGaA, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Halozyme, Array BioPharma, Biocartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Daiichi Sankyo, Pierre Fabre, Sirtex Medical, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Incyte, Astellas Pharma

Research Funding: amgen (Inst), Bayer (Inst), Boehringer Ingelheim (Inst), Lilly (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Roche (Inst), Celgene (Inst), Ipsen (Inst), Merck (Inst), Merck KGaA (Inst), SERVIER (Inst), Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst).

Josep Tabernero

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Lilly, MSD, Merck Serono, Novartis, Sanofi, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Peptomyc, Chugai Pharma, Pfizer, Seattle Genetics, Array BioPharma, AstraZeneca, Genentech, Menarini, Servier, HalioDx, F. Hoffmann LaRoche, Mirati Therapeutics, Pierre Fabre, Tessa Therapeutics, TheraMyc, Daiichi Sankyo, Samsung Bioepis, IQvia, Ikena Oncology, Merus, Neophore, Orion Biotechnology, Hutchison MediPharma, Avvinity, Scandion Oncology, Ona Therapeutics, Sotio Biotech, Inspirna Inc

Other Relationship: Imedex, Medscape, MJH Life Sciences, Peerview, Physicans' Education Resource

Jeanne Tie

Honoraria: SERVIER, Inivata

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca/MedImmune, Bristol Myers Squibb, Pierre Fabre, MSD Oncology, Inivata, Haystack Oncology

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1. Downward J. Targeting RAS signalling pathways in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:11–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Martin P, Leighl NB, Tsao MS, et al. KRAS mutations as prognostic and predictive markers in non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:530–542. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318283d958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lievre A, Bachet JB, Le Corre D, et al. KRAS mutation status is predictive of response to cetuximab therapy in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3992–3995. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cox AD, Fesik SW, Kimmelman AC, et al. Drugging the undruggable RAS: Mission possible? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13:828–851. doi: 10.1038/nrd4389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ostrem JM, Peters U, et al. Inhibitors allosterically control GTP affinity and effector interactions. Nature. 2013;503:548–551. doi: 10.1038/nature12796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ostrem JM, Shokat KM. Direct small-molecule inhibitors of KRAS: From structural insights to mechanism-based design. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15:771–785. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hong DS, Fakih MG, Strickler JH, et al. KRASG12C inhibition with sotorasib in advanced solid tumors. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1207–1217. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1917239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jänne PA, Rybkin II, Spira AI, et al. KRYSTAL-1: Activity and safety of adagrasib (MRTX849) in advanced/metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring KRASG12C mutation. Eur J Cancer. 2020;138:S1–S2. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Johnson ML, Ou SHI, Barve M, et al. KRYSTAL-1: Activity and safety of adagrasib (MRTX849) in patients with colorectal cancer (CRC) and other solid tumors harboring a KRASG12C mutation. Eur J Cancer. 2020;138:S2. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Andre T, Shiu KK, Kim TW, et al. Pembrolizumab in microsatellite-instability-high advanced colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2207–2218. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2017699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sun L, Tan M, Cohen RB, et al. Association between KRAS variant status and outcomes with first-line immune checkpoint inhibitor-based therapy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:937–939. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.0546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fernandes LE, Epstein CG, Bobe AM, et al. Real-world evidence of diagnostic testing and treatment patterns in US patients with breast cancer with implications for treatment biomarkers from RNA sequencing data. Clin Breast Cancer. 2020;21:e340–e361. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2020.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Beaubier N, Bontrager M, Huether R, et al. Integrated genomic profiling expands clinical options for patients with cancer. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37:1351–1360. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0259-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Beaubier N, Tell R, Lau D, et al. Clinical validation of the tempus xT next-generation targeted oncology sequencing assay. Oncotarget. 2019;10:2384–2396. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.26797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lozac’hmeur A, Hafez A, Perera J, et al. Microsatellite instability detection with cell-free DNA next-generation sequencing. Cancer. 2019;7:5. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhang Z, Hernandez K, Savage J, et al. Uniform genomic data analysis in the NCI genomic data commons. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1226. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21254-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Araujo LH, Souza BM, Leite LR, et al. Molecular profile of KRASG12C-mutant colorectal and non-small-cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 2021;21:193. doi: 10.1186/s12885-021-07884-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Arbour KC, Rizvi H, Plodkowski AJ, et al. Treatment outcomes and clinical characteristics of patients with KRAS-G12C-mutant non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27:2209–2215. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-4023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Riely GJ, Kris MG, Rosenbaum D, et al. Frequency and distinctive spectrum of KRAS mutations in never smokers with lung adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5731–5734. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Botteri E, Iodice S, Bagnardi V, et al. Smoking and colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300:2765–2778. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tsoi KK, Pau CY, Wu WK, et al. Cigarette smoking and the risk of colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:682–688.e1-5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Limsui D, Vierkant RA, Tillmans LS, et al. Cigarette smoking and colorectal cancer risk by molecularly defined subtypes. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:1012–1022. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Slattery ML, Curtin K, Anderson K, et al. Associations between cigarette smoking, lifestyle factors, and microsatellite instability in colon tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1831–1836. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.22.1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Samowitz WS, Albertsen H, Sweeney C, et al. Association of smoking, CpG island methylator phenotype, and V600E BRAF mutations in colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1731–1738. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Samadder NJ, Vierkant RA, Tillmans LS, et al. Cigarette smoking and colorectal cancer risk by KRAS mutation status among older women. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:782–789. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Weijenberg MP, Aardening PW, de Kok TM, et al. Cigarette smoking and KRAS oncogene mutations in sporadic colorectal cancer: Results from the Netherlands Cohort Study. Mutat Res. 2008;652:54–64. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Slattery ML, Anderson K, Curtin K, et al. Lifestyle factors and Ki-ras mutations in colon cancer tumors. Mutat Res. 2001;483:73–81. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(01)00228-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Diergaarde B, Vrieling A, van Kraats AA, et al. Cigarette smoking and genetic alterations in sporadic colon carcinomas. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:565–571. doi: 10.1093/carcin/24.3.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Berge EM, Doebele RC. Targeted therapies in non-small cell lung cancer: Emerging oncogene targets following the success of epidermal growth factor receptor. Semin Oncol. 2014;41:110–125. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Drilon A, Oxnard GR, Tan DSW, et al. Efficacy of selpercatinib in RET fusion-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:813–824. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2005653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Skoulidis F, Byers LA, Diao L, et al. Co-occurring genomic alterations define major subsets of KRAS-mutant lung adenocarcinoma with distinct biology, immune profiles, and therapeutic vulnerabilities. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:860–877. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. The Cancer Genome Atlas Network Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487:330–337. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dong ZY, Zhong WZ, Zhang XC, et al. Potential predictive value of TP53 and KRAS mutation status for response to PD-1 blockade immunotherapy in lung adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:3012–3024. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hallin J, Engstrom LD, Hargis L, et al. The KRASG12C inhibitor MRTX849 provides insight toward therapeutic susceptibility of KRAS-mutant cancers in mouse models and patients. Cancer Discov. 2020;10:54–71. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fakih M, Desai J, Kuboki Y, et al. CodeBreak 100: Activity of AMG 510, a novel small molecule inhibitor of KRASG12C, in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:4018. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Amodio V, Yaeger R, Arcella P, et al. EGFR blockade reverts resistance to KRASG12C inhibition in colorectal cancer. Cancer Discov. 2020;10:1129–1139. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jones S, Lambert S, Williams GT, et al. Increased frequency of the k-ras G12C mutation in MYH polyposis colorectal adenomas. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:1591–1593. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Viel A, Bruselles A, Meccia E, et al. A specific mutational signature associated with DNA 8-oxoguanine persistence in MUTYH-defective colorectal cancer. EBioMedicine. 2017;20:39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Henry JT, Coker O, Chowdhury S, et al. Comprehensive clinical and molecular characterization of KRASG12C-mutant colorectal cancer. JCO Precis Oncol. 2021:613–621. doi: 10.1200/PO.20.00256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ebi H, Faber AC, Engelman JA, et al. Not just gRASping at flaws: Finding vulnerabilities to develop novel therapies for treating KRAS mutant cancers. Cancer Sci. 2014;105:499–505. doi: 10.1111/cas.12383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Canon J, Rex K, Saiki AY, et al. The clinical KRASG12C inhibitor AMG 510 drives anti-tumour immunity. Nature. 2019;575:217–223. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1694-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

A data sharing statement provided by the authors is available with this article at DOI https://doi.org/10.1200/PO.21.00245.