Abstract

Background

Local anaesthetic nerve block is an important modality for pain management in labour. Pudendal and paracervical block (PCB) are most commonly performed local anaesthetic nerve blocks which have been used for decades.

Objectives

To establish the efficacy and safety of local anaesthetic nerve blocks for pain relief in labour.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (28 February 2012).

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) assessing pain management in labour with the use of local anaesthetic nerve blocks. We did not include results from quasi‐RCTs.

Data collection and analysis

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, two review authors extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we consulted a third person. We entered and analysed data using Review Manager software and checked for accuracy.

Main results

We found 41 trials for consideration of inclusion into this review. We included only 12 RCTs (1549 participants) of unclear quality. We excluded 29 studies (30 reports). The majority of excluded studies were not relevant to this review, and a few were not randomised.

Local anaesthetic nerve block versus placebo or no treatment

We found that more women were satisfied with pain relief after local anaesthetic nerve block (in particular 2% lidocaine PCB) than after placebo (one study, 198 participants, risk ratio (RR) 32.31, 95% confidence interval (CI) 10.60 to 98.54). Local anaesthetic nerve block was associated with more side effects (one study, 200 participants, RR 29.0, 95% CI 1.75 to 479.61).

Local anaesthetic nerve block (in particular, PCB) versus opioid

Local anaesthetic nerve block (in particular, PCB) in comparison with opioid (in particular, intramuscular pethidine or fentanyl patient‐controlled analgesia) was found to be more effective for pain relief (one study, 109 participants, RR 2.52, 95% CI 1.65 to 3.83) and was not associated with an increased rate of assisted vaginal birth (two studies, 129 participants, RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.87) or with an increased caesarean section rate (two studies, 129 participants, RR 0.23, 95% CI 0.03 to 1.87).

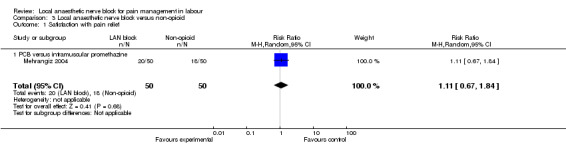

Local anaesthetic nerve block versus non‐opioid agents

Satisfaction with pain relief and rate of caesarean sections were found to be the same in women receiving local anaesthetic nerve block and non‐opioid agents (one study, 100 participants, RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.84; RR 2.0, 95% CI 0.19 to 21.36, respectively). More women who received non‐opioid agent in comparison with women who received local anaesthetic nerve block required additional interventions for pain relief (one study, 100 participants, RR 0.06, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.25).

Local anaesthetic nerve block using different anaesthetic agents

There was no difference in pain relief satisfaction, assisted vaginal birth, caesarean section, side effects for mother, Apgar score or admission to the neonatal intensive care unit between different anaesthetic agents, e.g. bupivacaine, carbocaine, lidocaine, chloroprocaine.

Authors' conclusions

Local anaesthetic nerve blocks are more effective than placebo, opioid and non‐opioid analgesia for pain management in labour based on RCTs of unclear quality and limited numbers. Side effects are more common after local anaesthetic nerve blocks in comparison with placebo. Different local anaesthetic agents used for pain relief provide similar satisfaction with pain relief. Further high‐quality studies are needed to confirm the findings, to assess other outcomes and to compare local anaesthetic nerve blocks with various modalities for pain relief in labour.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Pregnancy; Anesthetics, Local; Anesthesia, Obstetrical; Anesthesia, Obstetrical/methods; Fentanyl; Labor Pain; Labor Pain/therapy; Meperidine; Nerve Block; Nerve Block/methods; Pain Management; Pain Management/methods; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Local anaesthetic nerve block for pain management in labour

Most women find labour painful, although a few do not. Women who give birth more than once, can find very different levels of pain in their different labours. Women generally seek ways to help themselves cope with the labour, and some women look for additional help to manage the pain.

We looked at different types of local anaesthetic nerve block for control of pain in labour. We considered the paracervical block, which is an injection of local anaesthetic solution around the cervix, mostly used during the first stage of labour. Also, we looked at the pudendal block, which is an injection of local anaesthetic solution in the area of pudendal nerve in the pelvis, and is generally used in the second stage of labour.

We found 12 studies involving 1549 women. The studies were small and not of good quality and so we are not sure of the findings. The data suggested that both these local anaesthetics were more effective for pain relief than placebo. There was no difference in regards to pain relief with the use of different local anaesthetic solutions when performing local anaesthetic nerve blocks. Side effects of decreased fetal heart rate, giddiness, sweating and tingling in legs lasted only a short time and were reported in one study of local anaesthetic nerve blocks versus placebo.

Further good‐quality studies are needed to confirm the findings, to assess other outcomes and compare local anaesthetic nerve blocks with other forms of pain relief in labour.

Background

Local anaesthesia has been widely used for pain relief in labour. There are several local modalities available to achieve pain relief in labour such as paracervical block and pudendal block. Paracervical block (injection of local anaesthetic into the cervix) is administered in the first stage of labour to relieve the pain of uterine contractions. Pudendal block (injection of local anaesthetic into the area of pudendal nerve through vaginal wall) is used in the second stage of labour for pain relief, especially prior to instrumental deliveries.

Local anaesthesia is an alternative to other pain relief options in labour such as epidural block, especially when the latter is contraindicated or unavailable.

It is important to establish the efficacy of local anaesthetic modalities used for pain relief in labour, as well as the maternal and fetal side effects, to be able to recommend its wider use.

Description of the condition

Labour is associated with pain of various intensity, which is likely to be the most severe pain that a woman experiences in her lifetime (Melzack 1984). The pain experienced in labour is affected by the processing of multiple physiological and psychosocial factors (Lowe 2002; Simkin 2004). Perceptions of labour pain intensity vary. Very occasionally women feel no pain in labour and give birth unexpectedly (Gaskin 2003).

Pain originates from different sites during the process of labour and delivery. In the first stage of labour pain occurs during contractions, is visceral or cramp‐like in nature, originates in the uterus and cervix, and is produced by distention of uterine and cervical mechanoreceptors (pressure receptors) and by ischaemia (lack of tissue oxygenation) of uterine and cervical tissues. The pain signal enters the spinal cord after traversing the T10, T11, T12, and L1 white rami communicantes. In addition to the uterus, labour pain can be referred to the abdominal wall, lumbosacral region, iliac crests, gluteal areas, and thighs. Transition refers to the shift from the late first stage (7 cm to 10 cm cervical dilation) to the second stage of labour (full dilatation). Transition is associated with greater nociceptive input as the woman begins to experience somatic pain from vaginal distention. In the second stage of labour, somatic pain occurs from distention of the vagina, perineum, and pelvic floor. Stretching of the pelvic ligaments is the hallmark of the second stage of labour. The pain signal is transmitted to the spinal cord via three sacral nerves (S2, S3 and S4), which comprise the pudendal nerve. Second stage pain is more severe than first stage pain and is characterised by a combination of visceral pain from uterine contractions and cervical stretching and somatic pain from distention of vaginal and perineal tissues. In addition, the woman experiences rectal pressure and an urge to 'push' and expel the fetus as the presenting part descends into the pelvic outlet.

Description of the intervention

Local anaesthetic nerve blocks for pain relief in labour.

Paracervical block

A paracervical block is performed by infiltration of local anaesthetic into the lateral fornix. The direction of the needle has to be slightly lateral to the cervix and fetal head to avoid puncturing the fetus. When the needle guide is properly positioned, the needle is inserted through the guide, taking care not to extend more than 5 mm beyond the tip of the guide. The injection's depth is usually no more than 3 mm to decrease the risk of complications, such as fetal bradycardia (Thorp 1998). The injections are performed at the positions four and eight o'clock to avoid vascular areas.The syringe containing 10 mL of anaesthetic is attached to the needle and, if no blood is aspirated, 5 mL of anaesthetic are injected slowly into the vaginal submucosa, between contractions. After waiting three minutes, the same procedure is performed on the opposite side (Vidaeff 2010).

Pudendal block

A pudendal block is performed by injection of local anaesthetic around the trunk of the pudendal nerve, which is located behind the sacrospinous ligament. Using transvaginal approach, the ischial spines are palpated posterolateral to the vaginal sidewall. The sacrospinous ligament is a firm band running medially and posteriorly from the ischial spine to the sacrum. The needle guide with the needle and syringe containing anaesthetic are inserted so the tip lies against the vaginal mucosa about 1 cm medial and posterior to the ischial spine. When the needle guide is properly positioned, the needle is pushed beyond its tip and through the vaginal mucosa into the sacrospinous ligament. After aspirating to confirm the absence of an intravascular location, 3 mL of local anaesthetic are injected into the ligament. The needle is then advanced slightly until the sensation of resistance caused by the ligament is lost. The needle should now be lodged in the loose areolar tissue behind the ligament where the pudendal nerve is located. Aspiration is again performed to confirm the absence of an intravascular position (the pudendal and inferior gluteal vessels lie adjacent to the pudendal nerve), and then the remaining 7 mL of anaesthetic are injected. The procedure is repeated on the contralateral side (Vidaeff 2010).

Local anaesthetic agents

The local anaesthetics used for infiltrative analgesia in obstetrics include bupivacaine or marcaine, lidocaine or xylocaine, carbocaine or mepivacaine, chloroprocaine or nesacaine (Salts 1976; Schierup 1988).

How the intervention might work

Paracervical infiltration interrupts the visceral sensory fibres of the lower uterus, cervix, and upper vagina (T10‐L1) as they pass through the uterovaginal plexus (Frankenhauser's plexus, i.e. nerves innervating uterus, vagina, clitoris) on each side of the cervix, but does not affect the motor pathways. Therefore, progression of labour should not be significantly affected. Motor function is also not affected, so the women can mobilise, which is advantageous to the labour progress. However, fetal bradycardia is the main concern associated with this technique, which has made its use unpopular (Gibbs 1986; Palomaki 2005a).

Pudendal block is a form of analgesia used in the second stage of labour, predominantly when instrumental delivery is performed. During descent of the presenting part of the fetus in the second stage of labour, the primary focus of pain is in the lower vagina, perineum and vulva, which are innervated from sacral nerve roots two, three and four via the pudendal nerve. Infiltration of local anaesthetic around the trunk of the pudendal nerve at the level of ischial spines leads to analgesia of these areas. Prior to the widespread use of epidural analgesia in obstetrics, pudendal blocks were the preferred analgesic technique for delivery. Pudendal blocks are also used to supplement epidural labour analgesia, which occasionally may have some sacral sparring. Pudendal blocks are rarely associated with complications such as haematoma and infection at the site of injection, ischial paraesthesias and systemic toxicity due to intravascular administration. Neonatal toxicity is extremely rare and has resulted in complete recovery in a recent case report (Pages 2008). These blocks are of a value in cases with contraindications to neuraxial anaesthesia, such as bleeding disorders or infection, or in places where epidural anaesthesia is unavailable. There are concerns with the efficacy of pudendal block, as it is ineffective on one side in 10% to 50% of cases (Schierup 1988).

Another safety concern with the use of local anaesthetic nerve blocks is systemic effects such as excessive sedation, generalised convulsions, and cardiovascular collapse due to intravascular injection. Allergic reactions to local anaesthetics, as well as local side effects such as hematoma or infection at the site of injection, are rare.

Why it is important to do this review

It is important to establish the efficacy of local anaesthetic modalities used for pain management in labour, as well as the maternal and fetal side effects, to be able to recommend its wider use. These techniques are often used and it is essential to determine which techniques are more effective and safer.

It is important to know if women are satisfied with such pain relief options in labour.

This review is one in a series of Cochrane reviews examining pain management in labour. These reviews contribute to an overview of systematic reviews of pain management for women in labour (Jones 2011b), and share a generic protocol (Jones 2011a).

Objectives

To establish the efficacy and safety of local anaesthetic nerve blocks for pain relief in labour.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included only randomised controlled trials (RCTs). We did not include results from quasi‐RCTs in the analyses but we discussed them in the text if little other evidence was available. In future updates, we will only include studies published in an abstract form if they satisfy the inclusion criteria.

Types of participants

Women in labour requesting pain relief. This includes women in high‐risk groups, e.g. preterm labour or following induction of labour. We used subgroup analysis for any possible differences in the effect of interventions in these groups.

Types of interventions

This review is one in a series of Cochrane reviews examining pain management in labour. These reviews contribute to an overview of systematic reviews of interventions for pain management in labour, and share a generic protocol. To avoid duplication the different methods of pain relief have been listed in a specific order, from one to 15. Individual reviews focusing on particular interventions include comparisons with only the intervention above it on the list. Methods of pain management identified in the future will be added to the end of the list. The current list is as follows.

Placebo/no treatment.

Hypnosis (Madden 2011).

Biofeedback (Barragán 2011)

Intracutaneous or subcutaneous sterile water injection (Derry 2012).

Immersion in water (Cluett 2009).

Aromatherapy (Smith 2011a).

Relaxation techniques (yoga, music, audio) (Smith 2011d).

Acupuncture or acupressure (Smith 2011c).

Manual methods (massage, reflexology) (Smith 2011b).

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) (Dowswell 2009).

Inhaled analgesia (Klomp 2011).

Opioids (Ullman 2010).

Non‐opioid drugs (Othman 2011).

Local anaesthetic nerve blocks (this review).

Epidural (including combined spinal epidural) (Anim‐Somuah 2011; Simmons 2007).

Accordingly, this review will include comparisons of any type of local anaesthetic nerve block compared with any other type of local anaesthetic nerve block, as well as: local anaesthetic nerve block compared with: 1. placebo/no treatment; 2. hypnosis; 3. biofeedback; 4. intracutaneous or subcutaneous sterile water injection; 5. immersion in water; 6. aromatherapy; 7. relaxation techniques (yoga, music, audio); 8. acupuncture or acupressure; 9. manual methods (massage, reflexology); 10. TENS; 11. inhaled analgesia; 12. opioids; and 13. non‐opioid drugs.

Types of outcome measures

This review is one in a series of Cochrane reviews examining pain management in labour. These reviews contribute to an overview of systematic reviews of interventions for pain management in labour, and share a generic protocol. The following list of primary outcomes are the ones which are common to all the reviews.

Primary outcomes

Effects of interventions

Pain intensity (as defined by trialists)

Satisfaction with pain relief (as defined by trialists)

Sense of control in labour (as defined by trialists)

Satisfaction with childbirth experience (as defined by trialists)

Safety of interventions

Effect (negative) on mother/baby interaction

Breastfeeding (at specified time points)

Assisted vaginal birth

Caesarean section

Side effects (for mother ‐ vaginal haematoma, infection, pruritis, cardio‐vascular compromise, anaphylactic shock and baby ‐ fetal distress or signs of toxicity (hypotonia, apnoea, cyanosis, seizures))

Admission to special care baby unit/neonatal intensive care unit (as defined by trialists)

Apgar score less than seven at five minutes

Poor infant outcomes at long‐term follow‐up (as defined by trialists)

Other outcomes

Cost (as defined by trialists)

Secondary outcomes

Number of women after 10 minutes from the time of local anaesthesia experiencing satisfactory pain relief

Mean time from performing local anaesthesia to the time women felt the level of pain relief was satisfactory

Mean time taken to administer local anaesthesia

Number of women requiring an additional intervention for pain relief at any time after local anaesthesia

Mean time from performing local anaesthesia to delivery

Number of women with third‐ and fourth‐degree perineal tears

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We contacted the Trials Search Co‐ordinator to search the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register (28 February 2012).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

weekly searches of EMBASE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE and EMBASE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies we identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we consulted a third person.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, two review authors extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we consulted a third person. We entered data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2011) and checked for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we attempted to contact the authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed the risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreement by discussion or by involving a third assessor.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at a low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding would be unlikely to affect results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion, where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, we re‐included missing data in the analyses which we undertook.

We will assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated' analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it was clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review had been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes had been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest were reported incompletely and so could not be used; study failed to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We described for each included study any important concerns we have about other possible sources of bias.

We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

low risk of other bias;

high risk of other bias;

unclear whether there is risk of other bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at a high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it likely to impact on the findings. We planned to explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ seeSensitivity analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

For continuous data, we used the mean difference where outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. We planned to use the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measured the same outcome, but used different methods.

Ordinal data

For ordinal data measured on scales (e.g. pain measured on visual analogue scales), we planned to analyse as continuous data and the intervention effect expressed as a difference in means or standardised difference in means. For ordinal data (e.g. satisfaction with pain relief) measured on shorter ordinal scales (e.g. excellent, very good, good), we analysed as dichotomous data by combining categories (e.g. excellent and very good) and expressed the intervention effect using risk ratios.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We had intended to include cluster‐randomised trials in the analyses along with individually randomised trials. Their sample sizes would have been adjusted using the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Section 16.3.4, Higgins 2011) using an estimate of the intracluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial or from a study of a similar population. If we had used ICCs from other sources, we would have reported this and conducted sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we had identified both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials, we planned to synthesise the relevant information. We would have considered it reasonable to combine the results from both if there was little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit was considered to be unlikely.

We would also have acknowledged heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and performed a sensitivity or subgroup analysis to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit. We did not include cross‐over trials.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we noted levels of attrition. We planned to explore the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by using sensitivity analysis. We planned to exclude trials with more than 20% of missing data from the analysis.

For all outcomes, we carried out analyses, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis; i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses, and analysed all participants in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was to be the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the T², I² and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if the I² was greater than 30% and either the T² was greater than zero, or there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

If there had been 10 or more studies in the meta‐analysis, we planned to investigate reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We would have assessed funnel plot asymmetry visually, and used formal tests for funnel plot asymmetry. For continuous outcomes, we would have used the test proposed by Egger 1997, and for dichotomous outcomes, we would have used the test proposed by Harbord 2006. If asymmetry was detected in any of these tests or was suggested by a visual assessment, we planned to perform exploratory analyses to investigate it.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2011). We used fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it was reasonable to assume that studies were estimating the same underlying treatment effect: i.e. where trials were examining the same intervention, and we judged that the trials’ populations and methods were sufficiently similar. Where there was clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differed between trials, or if we detected substantial statistical heterogeneity, we used random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary if an average treatment effect across trials was considered clinically meaningful.

Where we used random‐effects analyses, we presented the results as the average treatment effect with its 95% confidence interval, and the estimates of T² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to carry out the following subgroup analyses.

Spontaneous labour versus induced labour.

Primiparous versus multiparous.

Term versus preterm birth.

Continuous support in labour versus no continuous support.

Pudendal block versus paracervical block.

We used the following outcomes in subgroup analysis, classifying whole trials by interaction tests as described by Deeks 2001.

Satisfaction with pain relief (as defined by trialists).

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform sensitivity analyses for the aspects of the review that might affect the results.

We planned to use the following outcomes in sensitivity analysis.

Satisfaction with pain relief (as defined by trialists).

Effect (negative) of intervention on mother or baby.

Results

Description of studies

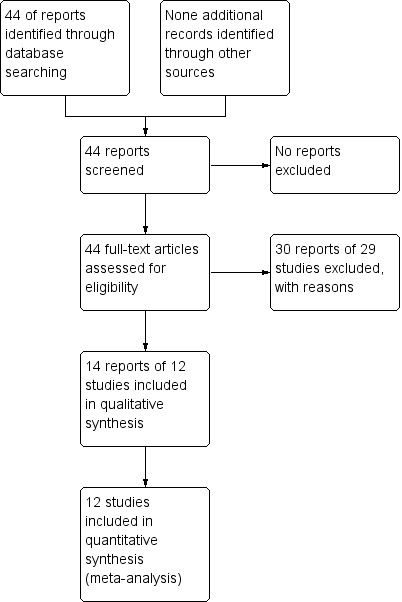

Twelve randomised‐controlled trials (including 1549 participants) were included in this review (Figure 1). One study compared local anaesthetic nerve block (PCB) to placebo (Shravage 2001). None of the studies compared paracervical block with pudendal block. Two studies compared PCB with opioids (Jensen 1984; Nikkola 2000) and one study with non‐opioids (Mehrangiz 2004).

1.

Study flow diagram.

One study compared PCB with 1% lidocaine with PCB with chloroprocaine (Weiss 1983); two studies 0.25% bupivacaine with 2% chloroprocaine (Belfrage 1983; Nesheim 1983); one study 0.25% bupivacaine with 1% carbocaine (Hoekegard 1969); one study 0.25 bupivacaine and 0.125% bupivacaine (Nieminen 1997); one study racemic bupivacaine and levobupivacaine (Palomaki 2005a); one study 1% carbocaine with and without adrenaline (Schierup 1988); and one study immediate and delayed injection of 1% lidocaine (Van Dorsten 1981). Only five studies comparing different agents for local anaesthetic nerve block reported on the primary outcome of this review (Belfrage 1983; Hoekegard 1969; Nesheim 1983; Palomaki 2005a; Weiss 1983).

All included studies have methodological shortcomings, e.g. limited number of participants, high risk of bias.

We excluded 29 trials for the following reasons: 13 studies assessed methods of pain relief unrelated to this review (Bridenbaugh 1969; Bridenbaugh 1977; Gunther 1969; Gunther 1972; Jacob 1962; Johnson 1957; Junttila 2009; Kuah 1968; Leighton 1999; Pace 2004; Pearce 1982, Peterson 1961Ulmsten 1980); five studies were not randomised (Fischer 1971; Palomaki 2005b; Pitkin 1963; Seeds 1962; Westholm 1970); three studies were quasi‐randomised (Hutchins 1980; Langhoff‐Roos 1985; Nabhan 2009); five studies assessed only neonatal neurobehavioural effects of local anaesthetic block but did not assess pain relief in labour (Jenssen 1973; Jenssen 1975; Merkow 1980; Nesheim 1979; Teramo 1969); and one study had a large number of missing data (Nyirjesy 1963). Finally, two studies (Kujansuu 1987; Manninen 2000) were excluded because this review is one in a series of Cochrane reviews which contribute to an overview of systematic reviews of pain management for women in labour (Jones 2011b) and share a generic protocol (Jones 2011a). In order to comply with the generic protocol, which has specific inclusion criteria relating to comparison interventions so as to avoid overlap between different reviews, two trials (Kujansuu 1987; Manninen 2000) have been assigned to the epidural review (Anim‐Somuah 2011).

Results of the search

The search of the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register retrieved 44 trials reports. We included 14 reports of 12 studies and excluded 30 reports of 29 studies (Figure 1).

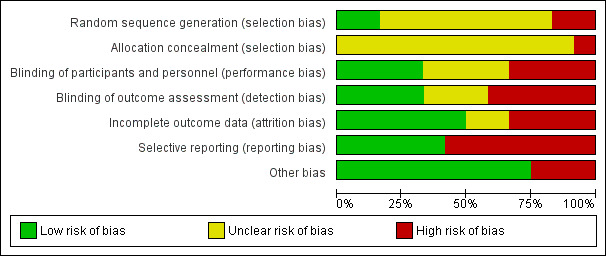

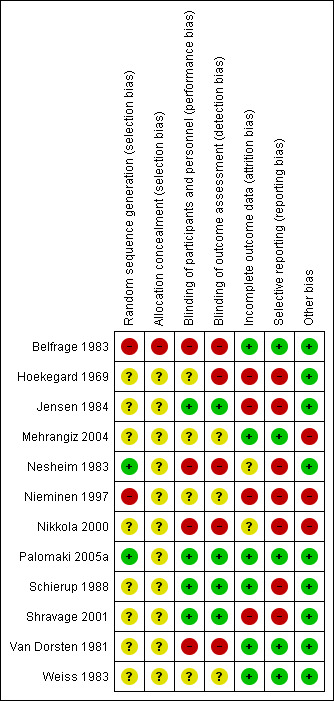

Risk of bias in included studies

All included studies had a high risk of bias (Figure 2; Figure 3).

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

The random sequence generation bias was high in two studies (Belfrage 1983; Nieminen 1997), unclear in eight studies (Hoekegard 1969; Jensen 1984; Mehrangiz 2004; Nikkola 2000; Schierup 1988; Shravage 2001; Van Dorsten 1981; Weiss 1983), and low in two studies (Nesheim 1983; Palomaki 2005a). Twelve studies did not provide information on allocation concealment and one study was at high risk of bias (Belfrage 1983). Four studies were blinded (Jensen 1984; Palomaki 2005a; Schierup 1988; Shravage 2001); blinding information was not given in four studies (Hoekegard 1969; Mehrangiz 2004; Nieminen 1997; Weiss 1983). Four studies were not blinded (Belfrage 1983; Nesheim 1983; Nikkola 2000; Van Dorsten 1981).

Four studies had a high risk of bias for incomplete outcome data (Hoekegard 1969; Jensen 1984; Nieminen 1997; Shravage 2001). Seven studies had a high risk of selective reporting bias (Hoekegard 1969; Jensen 1984; Nesheim 1983; Nieminen 1997; Nikkola 2000; Schierup 1988; Shravage 2001).

Effects of interventions

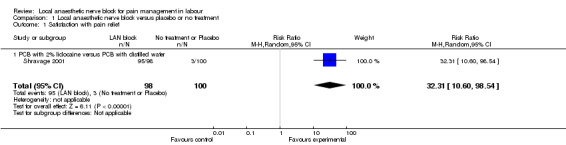

Local anaesthetic nerve block versus placebo

Primary outcomes

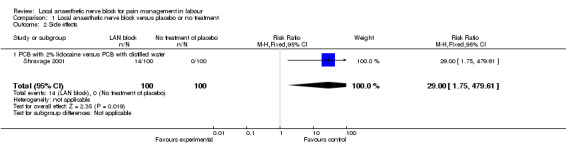

Local anaesthetic nerve block (in particular 2% lidocaine PCB) was more effective then placebo in relation to satisfaction with pain relief (one study, 198 participants, risk ratio (RR) 32.31, 95% confidence interval (CI) 10.60 to 98.54; Analysis 1.1) and was associated with more side effects (one study, 200 participants, RR 29.0, 95% CI 1.75 to 479.61; Analysis 1.2). Side effects reported in this study included nine cases of transient fetal bradycardia, and five women complained of giddiness, sweating and tingling in the lower limbs for a short period of time Shravage 2001.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Local anaesthetic nerve block versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 1 Satisfaction with pain relief.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Local anaesthetic nerve block versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 2 Side effects.

No data were reported for the primary outcomes of pain intensity (as defined by trialists); sense of control in labour (as defined by trialists); satisfaction with childbirth experience (as defined by trialists); effect (negative) on mother/baby interaction; breastfeeding (at specified time points); assisted vaginal birth, caesarean section; admission to special care baby unit/neonatal intensive care unit (as defined by trialists); an Apgar score less than seven at five minutes; poor infant outcomes at long‐term follow‐up (as defined by trialists); and cost (as defined by trialists).

Secondary outcomes

No data were reported for the secondary outcomes of the number of women after 10 minutes from the time of local anaesthesia experiencing satisfactory pain relief; mean time from performing local anaesthesia to the time women felt the level of pain relief was satisfactory; mean time taken to administer local anaesthesia; the number of women requiring an additional intervention for pain relief at any time after local anaesthesia; mean time from performing local anaesthesia to delivery; and the number of women with third‐ and fourth‐degree perineal tears in this group.

Local anaesthetic nerve block versus opioid

Primary outcomes

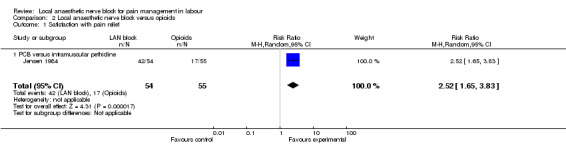

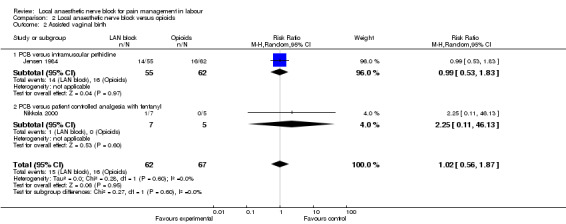

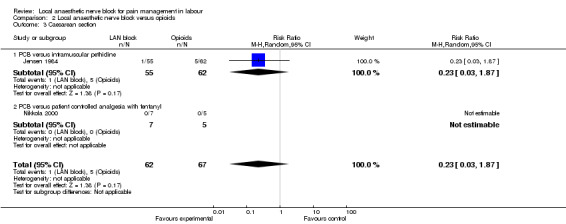

Local anaesthetic nerve block (in particular, PCB) in comparison with opioid (in particular, intramuscular pethidine or fentanyl patient‐controlled analgesia) was more effective for pain relief (one study, 109 participants, RR 2.52, 95% CI 1.65 to 3.83; Analysis 2.1) and was not associated with an increased rate of assisted vaginal birth (two studies, 129 participants, RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.87; Analysis 2.2) or an increased caesarean section rate (two studies, 129 participants, RR 0.23, 95% CI 0.03 to 1.87; Analysis 2.3). None of the babies had an Apgar score less than seven at five minutes (two studies, 122 participants; Analysis 2.4).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Local anaesthetic nerve block versus opioids, Outcome 1 Satisfaction with pain relief.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Local anaesthetic nerve block versus opioids, Outcome 2 Assisted vaginal birth.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Local anaesthetic nerve block versus opioids, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

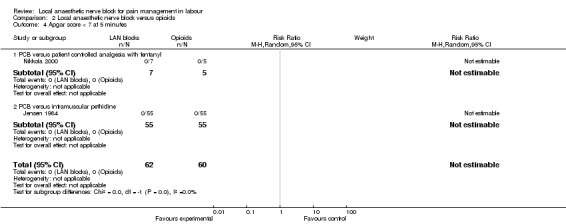

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Local anaesthetic nerve block versus opioids, Outcome 4 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

No data were reported for the primary outcomes sense of control in labour (as defined by trialists); satisfaction with childbirth experience (as defined by trialists); effect (negative) on mother/baby interaction; breastfeeding (at specified time points); admission to special care baby unit/neonatal intensive care unit (as defined by trialists); an Apgar score less than seven at five minutes; poor infant outcomes at long‐term follow‐up (as defined by trialists); cost (as defined by trialists); and side effects.

Secondary outcomes

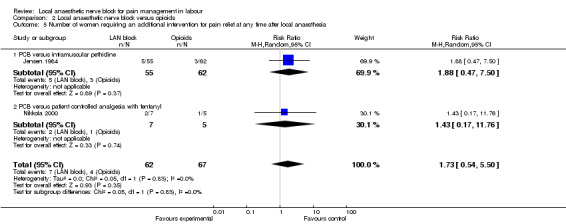

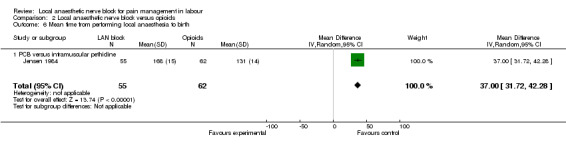

The number of women requiring additional intervention for pain relief at any time after local anaesthesia did not differ between women who received local anaesthetic nerve block or opioids (two studies, 129 participants, RR 1.73, 95% CI 0.54 to 5.50; Analysis 2.5). Mean time from receiving pain relief to birth was faster in women who received opioids in comparison with women who received local anaesthetic block (one study, 117 participants, RR 37.0, 95% CI 31.72 to 42.28; Analysis 2.6).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Local anaesthetic nerve block versus opioids, Outcome 5 Number of women requiring an additional intervention for pain relief at any time after local anaesthesia.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Local anaesthetic nerve block versus opioids, Outcome 6 Mean time from performing local anaesthesia to birth.

No data were reported for the secondary outcomes of the number of women after 10 minutes from the time of local anaesthesia experiencing satisfactory pain relief; mean time from performing local anaesthesia to the time women felt the level of pain relief was satisfactory; mean time taken to administer local anaesthesia; and the number of women with third‐ and fourth‐degree perineal tears in this group.

Local anaesthetic nerve block versus non‐opioid

Primary outcomes

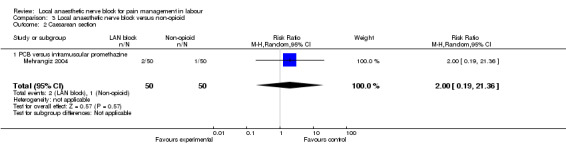

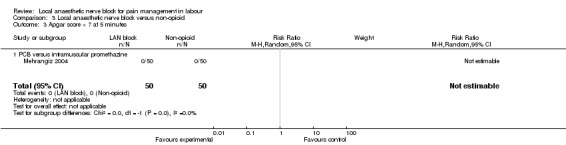

Satisfaction with pain relief and rate of caesarean sections were found to be the same in women receiving local anaesthetic nerve block and in women receiving a non‐opioid agent (one study, 100 participants, RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.84; Analysis 3.1; RR 2.0, 95% CI 0.19 to 21.36; Analysis 3.2, respectively). None of the babies had an Apgar score less than seven at five minutes (one study, 100 participants; Analysis 3.3).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Local anaesthetic nerve block versus non‐opioid, Outcome 1 Satisfaction with pain relief.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Local anaesthetic nerve block versus non‐opioid, Outcome 2 Caesarean section.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Local anaesthetic nerve block versus non‐opioid, Outcome 3 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

No data were reported for the primary outcomes of pain intensity (as defined by trialists); satisfaction with pain relief; sense of control in labour (as defined by trialists); satisfaction with childbirth experience (as defined by trialists); side effects; effect (negative) on mother/baby interaction; breastfeeding (at specified time points); assisted vaginal birth; admission to special care baby unit/neonatal intensive care unit (as defined by trialists); poor infant outcomes at long‐term follow‐up (as defined by trialists); and cost (as defined by trialists).

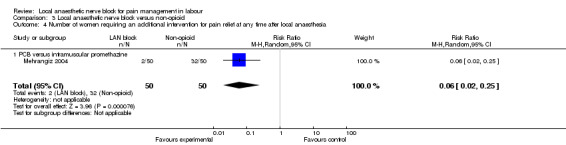

Secondary outcomes

More women who received non‐opioid agent in comparison with women who received local anaesthetic nerve block required additional intervention for pain relief (one study, 100 participants, RR 0.06, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.25; Analysis 3.4).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Local anaesthetic nerve block versus non‐opioid, Outcome 4 Number of women requiring an additional intervention for pain relief at any time after local anaesthesia.

No data were reported for the secondary outcomes of the number of women after 10 minutes from the time of local anaesthesia experiencing satisfactory pain relief; mean time from performing local anaesthesia to the time women felt the level of pain relief was satisfactory; mean time taken to administer local anaesthesia; mean time from performing local anaesthesia to delivery; and the number of women with third‐ and fourth‐degree perineal tears in this group.

Local anaesthetic nerve block versus different agent of anaesthetic nerve block:

a. Local anaesthetic nerve block with lidocaine versus chloroprocaine

Primary outcomes

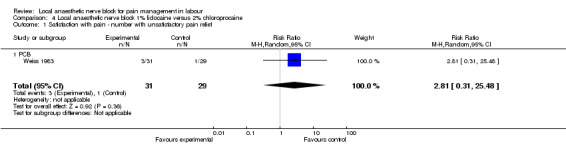

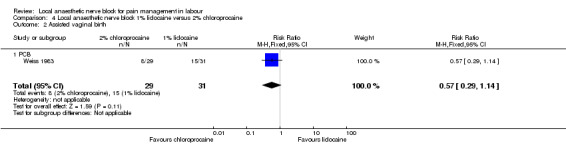

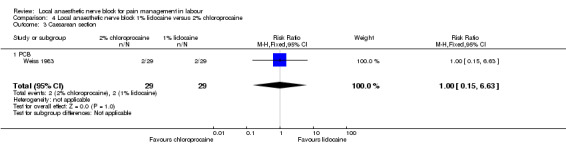

No difference was detected in pain relief satisfaction (defined as number of women having unsatisfactory pain relief) (one study, 60 participants, RR 2.81, 95% CI 0.31 to 25.48; Analysis 4.1), assisted vaginal birth (one study, 60 participants, RR 0.57, 95% CI 0.29 to 1.14; Analysis 4.2) or caesarean section (one study, 58 participants, RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.15 to 6.63; Analysis 4.3) between women who received lidocaine or chloroprocaine in PCB.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Local anaesthetic nerve block 1% lidocaine versus 2% chloroprocaine, Outcome 1 Satisfaction with pain ‐ number with unsatisfactory pain relief.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Local anaesthetic nerve block 1% lidocaine versus 2% chloroprocaine, Outcome 2 Assisted vaginal birth.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Local anaesthetic nerve block 1% lidocaine versus 2% chloroprocaine, Outcome 3 Caesarean section.

No data were reported for the primary outcomes of pain intensity (as defined by trialists); sense of control in labour (as defined by trialists); satisfaction with childbirth experience (as defined by trialists); effect (negative) on mother/baby interaction; breastfeeding (at specified time points); admission to special care baby unit/neonatal intensive care unit (as defined by trialists); an Apgar score less than seven at five minutes; poor infant outcomes at long‐term follow‐up (as defined by trialists); and cost (as defined by trialists).

Secondary outcomes

No data were reported for the secondary outcomes of the number of women after 10 minutes from the time of local anaesthesia experiencing satisfactory pain relief; mean time from performing local anaesthesia to the time women felt the level of pain relief was satisfactory; mean time taken to administer local anaesthesia; the number of women requiring an additional intervention for pain relief at any time after local anaesthesia; mean time from performing local anaesthesia to delivery; and the number of women with third‐ and fourth‐degree perineal tears in this group.

b. Local anaesthetic nerve block with bupivacaine versus another local anaesthetic agent (e.g. chloroprocaine, carbocaine)

Primary outcomes

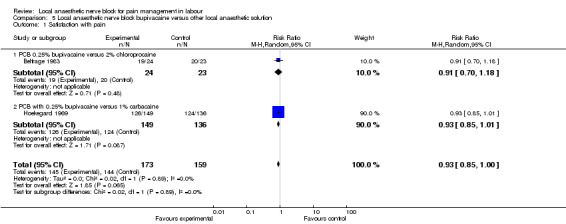

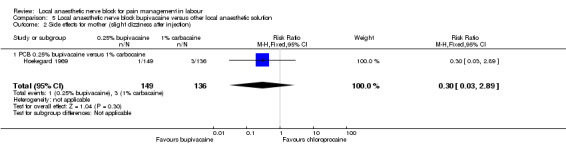

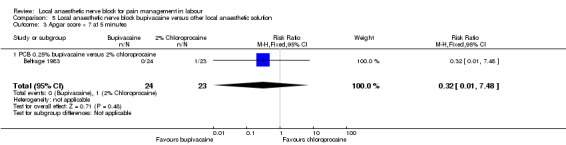

No difference was detected in pain relief satisfaction between women who received bupivacaine or chloroprocaine or carbocaine in PCB (two studies, 332 participants, RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.00; Analysis 5.1). There was also no difference in side effects for the mother (dizziness after injection) between women who received bupivacaine or carbocaine (one study, 285 participants, RR 0.30, 95% CI 0.03 to 2.89; Analysis 5.2) or in babies having Apgar scores less than seven at five minutes between women who received bupivacaine or chloroprocaine (one study, 47 participants, RR 0.32, 95% CI 0.01 to 7.48; Analysis 5.3).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Local anaesthetic nerve block bupivacaine versus other local anaesthetic solution, Outcome 1 Satisfaction with pain.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Local anaesthetic nerve block bupivacaine versus other local anaesthetic solution, Outcome 2 Side effects for mother (slight dizziness after injection).

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Local anaesthetic nerve block bupivacaine versus other local anaesthetic solution, Outcome 3 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

No data were reported for the primary outcomes of pain intensity (as defined by trialists); sense of control in labour (as defined by trialists); assisted vaginal birth; caesarean section; satisfaction with childbirth experience (as defined by trialists); effect (negative) on mother/baby interaction; breastfeeding (at specified time points); number of babies admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit; poor infant outcomes at long‐term follow‐up (as defined by trialists); and cost (as defined by trialists).

Secondary outcomes

No data were reported for secondary outcomes of the number of women after 10 minutes from the time of local anaesthesia experiencing satisfactory pain relief; in number of women requiring an additional intervention for pain relief at any time after local anaesthesia; mean time from performing local anaesthesia to the time women felt the level of pain relief was satisfactory; mean time taken to administer local anaesthesia; mean time from performing local anaesthesia to delivery; and the number of women with third‐ and fourth‐degree perineal tears in this group.

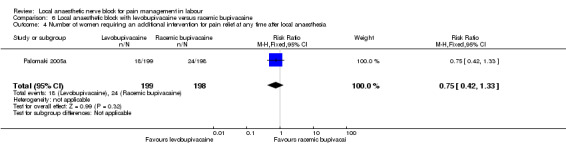

c. Local anaesthetic nerve block with levobupivacaine versus racemic bupivacaine

Primary outcomes

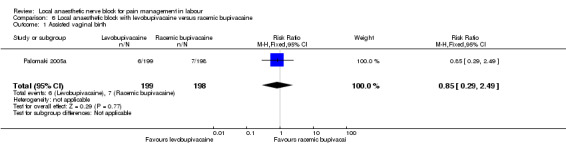

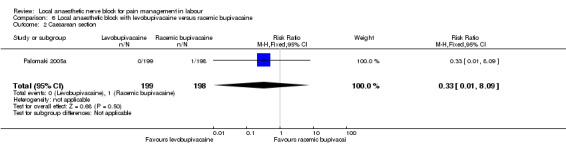

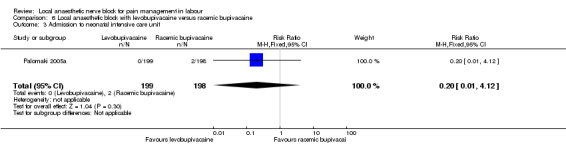

No difference was detected in assisted vaginal birth (one study, 397 participants, RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.29 to 2.49; Analysis 6.1) or caesarean section (one study, 397 participants, RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.01 to 8.09; Analysis 6.2) between women who received levobupivacaine or racemic bupivacaine in PCB. No difference was detected in babies admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit between women who received levobupivacaine or racemic bupivacaine in PCB (one study, 397 participants, RR 0.20, 95% CI 0.01 to 4.12; Analysis 6.3).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Local anaesthetic block with levobupivacaine versus racemic bupivacaine, Outcome 1 Assisted vaginal birth.

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Local anaesthetic block with levobupivacaine versus racemic bupivacaine, Outcome 2 Caesarean section.

6.3. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Local anaesthetic block with levobupivacaine versus racemic bupivacaine, Outcome 3 Admission to neonatal intensive care unit.

No data were reported for the primary outcomes of pain intensity (as defined by trialists); pain relief satisfaction; sense of control in labour (as defined by trialists); satisfaction with childbirth experience (as defined by trialists); effect (negative) on mother/baby interaction; side effects for the mother; breastfeeding (at specified time points); Apgar scores; poor infant outcomes at long‐term follow‐up (as defined by trialists); and cost (as defined by trialists).

Secondary outcomes

No difference was detected in number of women requiring an additional intervention for pain relief at any time after local anaesthesia between women who received levobupivacaine or racemic bupivacaine in PCB (one study, 397 participants, RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.42 to 1.33; Analysis 6.4).

6.4. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Local anaesthetic block with levobupivacaine versus racemic bupivacaine, Outcome 4 Number of women requiring an additional intervention for pain relief at any time after local anaesthesia.

No data were reported for secondary outcomes of the number of women after 10 minutes from the time of local anaesthesia experiencing satisfactory pain relief; mean time from performing local anaesthesia to the time women felt the level of pain relief was satisfactory; mean time taken to administer local anaesthesia; mean time from performing local anaesthesia to delivery; and the number of women with third‐ and fourth‐degree perineal tears in this group.

Discussion

Local anaesthetic nerve block is a common modality for pain management in labour. Although its use became less common in the high‐income countries due to the implementation of epidural block facilities on labour wards, it is still a useful method of pain relief in labour, especially for women with contraindications to epidural block (coagulopathy, sepsis), for women who wish to stay mobile during labour and in settings where there is no access to epidural service in labour.

We found a number of small studies on local anaesthetic nerve blocks of unclear quality, which reported only on a few outcomes.

The primary outcome initially established for this review, e.g. pain intensity (as defined by trialists) was not possible to assess as the majority of included studies did not report on this outcome or did not report upon it in a suitable format (Nesheim 1983; Nieminen 1997; Nikkola 2000; Palomaki 2005a). We decided to use satisfaction with pain relief as the primary outcome for the analysis. We found that local anaesthetic nerve blocks are more effective than placebo, opioid and non‐opioid agents for pain management in labour based on randomised controlled trials of unclear quality and limited numbers.

Reported side effects (transient fetal bradycardia, giddiness, sweating and tingling in the lower limbs) were only minor and more commonly occurred after local anaesthetic nerve blocks than after placebo. There were no significant adverse neonatal effects (based on an Apgar score of less than seven at five minutes) observed with the use of local anaesthetic nerve blocks.

Several local anaesthetic agents used for local anaesthetic nerve blocks were compared (lidocaine, chloroprocaine, carbocaine, bupivacaine). All of them had the same effect on pain relief.

All included studies assessed paracervical block (PCB), except one assessing pudendal block. The technique of performing PCB was consistent between included studies.

Participants of all included studies were healthy women at term with singleton pregnancies and cephalic presentation.

There were no studies to compare local anaesthetic nerve blocks with other local anaesthetic nerve blocks, hypnosis, biofeedback, sterile water injection, immersion in water, aromatherapy, relaxation techniques, acupuncture or acupressure, manual methods, inhaled analgesia. The included studies did not report outcomes separately for women in spontaneous and induced labour, women with and without continuous support in labour. Participants of all studies had full‐term pregnancies, therefore, the effects of local anaesthetic nerve blocks on preterm labour could not be assessed.

Effects on mother/baby interaction and breastfeeding were not reported in any of the included studies and should be assessed in future randomised controlled trials.

Further high‐quality studies are needed to confirm the findings, to assess other outcomes and compare local anaesthetic nerve blocks with modalities for pain relief in labour.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Subject to methodological shortcomings, local anaesthetic nerve blocks are more effective than placebo, opioid and non‐opioid agents for pain management of labour based on randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of unclear quality and limited numbers. Different local anaesthetic agents used for local anaesthetic nerve blocks provide similar satisfaction with pain relief. The safety of local anaesthetic nerve blocks is unclear from the currently available evidence.

Implications for research.

Because of the risk of bias in all included studies, adequately sized, blinded, RCTs are needed to confirm the findings of this review. Further research is needed to examine the use of local anaesthetic nerve blocks in different subgroups, e.g. women with spontaneous versus induced labour, primiparous versus multiparous, term versus preterm birth, women with and without continuous support in labour, and to compare the use of local anaesthetic nerve blocks with other modalities of pain relief in labour. Further trials are needed to assess the mother/baby interaction on breastfeeding.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 25 September 2015 | Amended | We have corrected two typographical errors. |

Acknowledgements

Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group team for technical support in preparation of review.

Leanne Jones for assistance with editor's and reviewers' edits.

As part of the pre‐publication editorial process, this review has been commented on by two peers (an editor and referee who is external to the editorial team), a member of the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's international panel of consumers and the Group's Statistical Adviser.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Local anaesthetic nerve block versus placebo or no treatment.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Satisfaction with pain relief | 1 | 198 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 32.31 [10.60, 98.54] |

| 1.1 PCB with 2% lidocaine versus PCB with distilled water | 1 | 198 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 32.31 [10.60, 98.54] |

| 2 Side effects | 1 | 200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 29.0 [1.75, 479.61] |

| 2.1 PCB with 2% lidocaine versus PCB with distilled water | 1 | 200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 29.0 [1.75, 479.61] |

Comparison 2. Local anaesthetic nerve block versus opioids.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Satisfaction with pain relief | 1 | 109 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.52 [1.65, 3.83] |

| 1.1 PCB versus intramuscular pethidine | 1 | 109 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.52 [1.65, 3.83] |

| 2 Assisted vaginal birth | 2 | 129 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.56, 1.87] |

| 2.1 PCB versus intramuscular pethidine | 1 | 117 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.53, 1.83] |

| 2.2 PCB versus patient controlled analgesia with fentanyl | 1 | 12 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.25 [0.11, 46.13] |

| 3 Caesarean section | 2 | 129 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.23 [0.03, 1.87] |

| 3.1 PCB versus intramuscular pethidine | 1 | 117 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.23 [0.03, 1.87] |

| 3.2 PCB versus patient controlled analgesia with fentanyl | 1 | 12 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 2 | 122 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4.1 PCB versus patient controlled analgesia with fentanyl | 1 | 12 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4.2 PCB versus intramuscular pethidine | 1 | 110 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5 Number of women requiring an additional intervention for pain relief at any time after local anaesthesia | 2 | 129 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.73 [0.54, 5.50] |

| 5.1 PCB versus intramuscular pethidine | 1 | 117 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.88 [0.47, 7.50] |

| 5.2 PCB versus patient controlled analgesia with fentanyl | 1 | 12 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.43 [0.17, 11.76] |

| 6 Mean time from performing local anaesthesia to birth | 1 | 117 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 37.0 [31.72, 42.28] |

| 6.1 PCB versus intramuscular pethidine | 1 | 117 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 37.0 [31.72, 42.28] |

Comparison 3. Local anaesthetic nerve block versus non‐opioid.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Satisfaction with pain relief | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.11 [0.67, 1.84] |

| 1.1 PCB versus intramuscular promethazine | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.11 [0.67, 1.84] |

| 2 Caesarean section | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.0 [0.19, 21.36] |

| 2.1 PCB versus intramuscular promethazine | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.0 [0.19, 21.36] |

| 3 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3.1 PCB versus intramuscular promethazine | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4 Number of women requiring an additional intervention for pain relief at any time after local anaesthesia | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.06 [0.02, 0.25] |

| 4.1 PCB versus intramuscular promethazine | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.06 [0.02, 0.25] |

Comparison 4. Local anaesthetic nerve block 1% lidocaine versus 2% chloroprocaine.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Satisfaction with pain ‐ number with unsatisfactory pain relief | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.81 [0.31, 25.48] |

| 1.1 PCB | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.81 [0.31, 25.48] |

| 2 Assisted vaginal birth | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.57 [0.29, 1.14] |

| 2.1 PCB | 1 | 60 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.57 [0.29, 1.14] |

| 3 Caesarean section | 1 | 58 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.15, 6.63] |

| 3.1 PCB | 1 | 58 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.15, 6.63] |

Comparison 5. Local anaesthetic nerve block bupivacaine versus other local anaesthetic solution.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Satisfaction with pain | 2 | 332 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.85, 1.00] |

| 1.1 PCB 0.25% bupivacaine versus 2% chloroprocaine | 1 | 47 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.70, 1.18] |

| 1.2 PCB with 0.25% bupivacaine versus 1% carbacaine | 1 | 285 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.85, 1.01] |

| 2 Side effects for mother (slight dizziness after injection) | 1 | 285 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.30 [0.03, 2.89] |

| 2.1 PCB 0.25% bupivacaine versus 1% carbocaine | 1 | 285 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.30 [0.03, 2.89] |

| 3 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 1 | 47 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.32 [0.01, 7.48] |

| 3.1 PCB 0.25% bupivacaine versus 2% chloroprocaine | 1 | 47 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.32 [0.01, 7.48] |

Comparison 6. Local anaesthetic block with levobupivacaine versus racemic bupivacaine.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Assisted vaginal birth | 1 | 397 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.29, 2.49] |

| 2 Caesarean section | 1 | 397 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.01, 8.09] |

| 3 Admission to neonatal intensive care unit | 1 | 397 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.20 [0.01, 4.12] |

| 4 Number of women requiring an additional intervention for pain relief at any time after local anaesthesia | 1 | 397 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.42, 1.33] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Belfrage 1983.

| Methods | Randomised, e.g. "paracervical block was randomly administered". | |

| Participants | 47 women in labour at 38‐42 weeks with normal pregnancy. All infants delivered vaginally in cephalic presentation. | |

| Interventions | PCB was administered at cervical dilatation of 6‐7 cm with 12 mL of 2% chloroprocaine or 0.25% bupivacaine at the 4, 5, 6, 8 o'clock positions at the depth 2‐4 mm. | |

| Outcomes | The onset and duration of the block were evaluated by an anaesthetist. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | "Patients were randomly assigned" to the intervention. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | None. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not blinded. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not blinded. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Data complete. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | None identified. |

| Other bias | Low risk | None identified. |

Hoekegard 1969.

| Methods | Randomised. | |

| Participants | 216 primigravidas in the first stage of labour. | |

| Interventions | PCB was administered with 0.25% bupivacaine with epinephrine 1:400,000 or 1% carbocaine with epinephrine 1:400,000 10 mL on each side. | |

| Outcomes | Duration of analgesia, serious side effects, fetal bradycardia. | |

| Notes | 3 infants died without any relationship to paracervical anaesthesia according to the authors. No details on causes of death were given. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not blinded. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not blinded. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | 90 cases were excluded in the data analysis of the duration of anaesthesia because the authors considered the recurrence of pain in these cases to be related to the head descent. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | See above. |

| Other bias | Low risk | None identified. |

Jensen 1984.

| Methods | Randomised double‐blinded. | |

| Participants | 117 primiparous women with uncomplicated term pregnancy, regular painful contractions necessitating analgesia, clear amniotic fluid, normal cardiotocogram and cervix dilated to 3‐5 cm. | |

| Interventions | PCB with 0.25% bupivacaine 12 mL and intramuscular injection of normal saline or PCB with normal saline and intramuscular injection of 1.5 mL (75 mg) of meperidine (pethidine). The depth of PCB injection was 3 mm. | |

| Outcomes | Satisfaction with pain, umbilical cord pH, Apgar score at 1 and 5 minutes. | |

| Notes | Pain score of 8 women who were missing (7 in pethidine group and 1 in PCB group). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Participants and personnel were blinded. Placebo was used in both groups. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Blinded. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Pain score of 8 women were missing (7 in pethidine group and 1 in PCB group). |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Pain score of 8 women were missing (7 in pethidine group and 1 in PCB group) |

| Other bias | Low risk | None identified. |

Mehrangiz 2004.

| Methods | Randomised. | |

| Participants | 100 women with uncomplicated term pregnancies in established early labour. 42% of women were primigravidae. Women with uteroplacental insufficiency, diabetes, gestational hypertension, malpresentation, chronic hypertension were excluded. Selected patients were at 4‐5 cm cervical dilatation and had contractions. The visual pain scale was performed and the patients with score 8‐10 were included in the study. | |

| Interventions | Group 1 ‐ Promethazine 25 mg intramuscularly every 3 hours. Group 2 ‐ PCB and promethazine when needed. |

|

| Outcomes | Time onset of analgesia, mean time of pain free interval and parity, neonatal outcome, effect on fetal heart rate, degree of pain relief, mean labour progress, the rate of caesarean section, Apgar scores. | |

| Notes | The description of intervention was limited. The solution, concentration and dosage used for PCB were not named in the paper. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "Randomly divided." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | In the abstract authors mentioned that "double blinding" was performed, however there are no further details. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | In the abstract authors mentioned that "double blinding" was performed, however there are no further details. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Data complete. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | No bias identified. |

| Other bias | High risk | The description of intervention was limited. The solution, concentration and dosage used for PCB were not named in the paper. |

Nesheim 1983.

| Methods | Randomised. | |

| Participants | 115 women in labour at 4‐6 cm cervical dilatation. | |

| Interventions | PCB was administered with Kobac needle at the 3, 4.30, 7.30, 9 o'clock positions. Group 1 (n = 43) ‐ 0.25% 20 mL bupivacaine. Group 2 (n = 22) ‐ 0.25% 20 mL bupivacaine with adrenaline 1:400,000. Group 3 (n = 28) ‐ 2% 20 mL chloroprocaine. Group 4 (n = 22) ‐ 2% 20 mL chloroprocaine with adrenaline 1:400,000. All blocks were given by either of 2 experienced obstetricians. |

|

| Outcomes | Pain relief on 10 cm visual analogue scale ‐ patient was asked a few minutes after she received the block to indicate the degree of pain she had before and after receiving the block. Duration of the block, time from PCB to fully dilatation, use of oxytocin, birthweight, Apgar score and method of delivery. |

|

| Notes | No outcomes assessed in our review were reported in this study. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation was done by tossing a coin twice, e.g. the first toss determined which anaesthetic, the second toss whether adrenalin should be used. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not blinded. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not blinded. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Complete data. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | The authors reported Apgar score below 9 (not conventional 7) at 5 minutes, which is most likely underreporting of negative effect of intervention. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other bias identified. |

Nieminen 1997.

| Methods | Randomised double‐blind. | |

| Participants | 93 women with uncomplicated pregnancies at 37‐42 weeks of gestation in active labour, cephalic presentation. | |

| Interventions | PCB was administered by Kobac needle by injecting with 0.25% 10 mL of bupivacaine (group 1) or 0.125% 10 mL of bupivacaine (group 2) at the 3 and 9 o'clock positions (5 mL on each side) at the depth of 3‐4 mm. | |

| Outcomes | Pain intensity assessed with visual analogue scale, fetal heart rate pattern, side effects. | |

| Notes | Due to the expiry time of the bupivacaine solutions the distribution of the patients became 52 in group 1 and 48 in group 2. 1 infant's Apgar score was not reported due to congenital cardiac failure. This study assessed different concentration of the local anaesthetic agent and if reported pain intensity or satisfaction with pain relief outcome could have been included in the subgroup analysis, however, these outcomes were not reported in this study. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Randomisation method was not described. The authors state that based on previous study 50 patients were selected to be included. Due to the expiry date of bupivacaine solution the distribution of the patients became 52 in group 1 and 48 in group 2. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | 3 patients from group 2 were excluded because only injection to 1 side of the cervix could be performed before the delivery. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | 1 infant's Apgar score was not reported due to congenital cardiac failure. |

| Other bias | High risk | The drugs were supplied in coded vials. The code was opened only after pain intensity and fetal heart rate patterns were analysed. It is not clear if this happened before or after randomisation. |

Nikkola 2000.

| Methods | Randomised. | |

| Participants | 12 healthy multipara women with uncomplicated pregnancies at 37 and more gestational weeks, in labour, age 20‐36 years, with no chronic diseases, no regular use of any medication. | |

| Interventions | Group 1 ‐ patient controlled analgesia with intravenous fentanyl. If effect was poor the rescue analgesia with PCB was offered. Group 2 ‐ PCB 10 mL 0.25% bupivacaine. |

|

| Outcomes | Maternal ‐ maternal SpO2, heart rate, blood pressure, subjective pain with 100 mm visual analogue scale, subjective side effects. Fetal ‐ cardiotocogram, umbilical artery and vein blood samples for fentanyl determinations and acid‐base balance, Apgar score, blood pressure, adaptive capacity scoring system, neonatal well‐being using static‐charge‐sensitive bed (gives information on sleep states, respiration, cardiac function, body movements) for 12 hours. |

|

| Notes | The study was interrupted because 1 baby in the fentanyl group had a significant decrease in oxyhaemoglobin saturation (SpO2) to 59%, which was considered to be a residual effect of fentanyl and was treated with naloxone. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not blinded. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not blinded. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Complete data. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | The study was interrupted due to a side effect in fentanyl group. |

| Other bias | High risk | Small number of subjects in the study. |

Palomaki 2005a.

| Methods | Randomised. | |

| Participants | 397 women with normal pregnancy and normal latent phase of labour age 18‐40 years, singleton, cephalic presentation, at 37‐42 weeks' gestation, normal cardiotocogram before PCB, ruptured membranes, cervical dilatation 3‐7 cm, no fetopelvic disproportion, no chronic maternal illnesses. | |

| Interventions | PCB was administered with Kobac needle at the 3, 4, 8, 9 o'clock positions in the lateral fornix of the vagina at the depth of 3‐4 mm. | |

| Outcomes | The intrauterine pressure, Apgar score, cord artery acid‐base balance, clinical outcome, analgesic effect of the block measured with visual analogue scale, median time from PCB to delivery, the type of delivery (spontaneous, vacuum extraction, caesarean section), admission to neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). | |

| Notes | Non‐randomised pilot study to characterise the use of levobupivacaine in PCB, which included 40 women, was initially undertaken. Racemic bupivacaine was compared to levobupivacaine. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated randomisation. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Blinded. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Blinded. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Complete data. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | None identified. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other bias were identified. |

Schierup 1988.

| Methods | Randomised double‐blinded. | |

| Participants | 150 women with normal pregnancies. | |

| Interventions | Pudendal block with 1% carbocaine 20 mL with adrenaline 5 mcg/mL or without adrenaline. | |

| Outcomes | Clinical efficacy of the block with the skin prick, Apgar scores at 1 and 5 minutes, the use of methylergometrin or oxytocin, maternal blood pressure after delivery, block‐delivery interval. | |

| Notes | This study assessed the same local anaesthetic agent used with and without adrenaline. None of the outcomes reported were included in this review. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomisation method was not described ("randomly allocated"). |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Blinded. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Blinded. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Data complete. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Only Apgar score at 5 minutes > 9, > 5 were reported and not conventional < 7. |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other bias identified. |

Shravage 2001.

| Methods | Randomised. | |

| Participants | 200 women with uncomplicated pregnancies in established early labour. | |

| Interventions | PCB was administered with 2% lidocaine 20 mL or 20 mL of distilled water at the 2, 5, 7, 11 o'clock positions in the lateral vaginal fornix. | |

| Outcomes | Duration of mean active phase of labour, second stage of labour, third stage of labour, rate of cervical dilatation, mean injection‐delivery interval, degree of pain relief, effect on fetal heart rate, Apgar score at 5 minutes. | |

| Notes | Although mean time from performing local anaesthesia to delivery was provided, standard deviations were not mentioned and, therefore, we could not include data on this outcome. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomisation method was not described ("randomly allotted"). |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Blinded. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Blinded. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Data on degree of pain relief are missing on 2 subjects in lidocaine PCB group. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Only Apgar score at 5 minutes < 4, 5‐7, > 8 were reported and not conventional < 7. |