Abstract

Background:

Incapacitated rape (IR) is common in college and has been linked to heavier post-assault drinking and consequences, including blackouts. Following IR, college students may adjust their drinking in ways that are meant to increase perceived safety, such as enhancing situational control over one’s drinks through prepartying, or drinking before going out to a main social event. It is also possible that prepartying may influence risk related to IR. However, it is unclear whether or how prepartying and IR may be associated.

Methods:

To address these gaps, we sought to examine prepartying as both a risk factor and consequence of IR, including the reasons for prepartying. Across two studies (Study 1 N = 1,074; Study 2 N = 1,753) of college women and men, we examined associations between IR and prepartying motives, alcohol consumption, and alcohol-related blackouts.

Results:

Within the cross-sectional Study 1, negative binomial regressions revealed that having a history of IR was associated with more alcohol consumption and blackouts when prepartying. Within a multivariate model, past-year IR was associated with preparty motives related to interpersonal enhancement, intimate pursuit, and barriers to consumption, but not situational control. Within the prospective Study 2, a path model revealed that preparty drinking was a prospective predictor of IR in the following year, but past-year IR did not predict subsequent prepartying.

Conclusions:

Findings revealed a robust link between recent history of IR and prepartying regardless of gender. Prepartying was found to be a prospective risk factor for subsequent IR. Although more research is needed, addressing prepartying in alcohol interventions may be indicated to improve prevention of negative outcomes, including sexual assault.

Keywords: alcohol-involved sexual assault, drug- and alcohol-facilitated rape, pregaming, pre-drinking, heavy drinking

Introduction

Unwanted sexual experiences are common among college students; up to a third of college women (Fedina et al., 2018) and a quarter of college men (Forsman, 2017; Luetke et al., 2020) report an unwanted sexual experience. During college, the most common form of non-consensual sex experienced by both women (Krebs et al., 2009; Mohler-Kuo et al., 2004) and men (Luetke et al., 2020; Peterson et al., 2011; Waldner-Haugrud & Magruder, 1995) is when an individual is too intoxicated to consent due to substance use, known as incapacitated rape (IR). Heavy drinking among college women and men has been revealed to be both a risk factor and a consequence of IR (Kaysen et al., 2006). Yet, it is unclear whether or how other risky drinking patterns, such as prepartying, may influence risk related to IR. Information of this kind can assist in our understanding of relevant targets for prevention and intervention programs aimed at reducing heavy drinking and IR in college.

Given that substances must be involved for a sexual assault to meet criteria for IR, and the most common substance involved in IR is alcohol (Lawyer et al., 2010; Scott-Ham & Burton, 2005), it follows that alcohol use is commonly associated with risk for IR (Testa & Livingston, 2018). Prospective research among college students indicates that heavy drinking is a risk factor preceding IR (Kaysen et al., 2006) and heavy drinking tends to further escalate after IR (Kaysen et al., 2006; Norris et al., 2019). Although this research highlights that IR may lead to escalations in drinking to cope, recent work also indicates that IR may motivate some women to reduce their drinking. Among heavy-drinking college women, IR was linked to a greater readiness to change drinking behaviors (Jaffe, Blayney, et al., 2021). Similarly, IR was associated with self-reported reductions in drinking among a clinical sample of sexual assault survivors with posttraumatic stress disorder (Jaffe, Kaysen, et al., 2021). Survivors of IR may also change the manner in which they drink alcohol to increase their perceived safety. For example, students tend to report concern that their drink will be spiked if left unattended or if mixed by someone else (Burgess et al., 2009) despite evidence that drink spiking is exceedingly rare (Anderson et al., 2017). It is possible that such concerns may be heightened among individuals who have experienced IR in the past, and they may change the manner in which they drink to protect against this perceived risk. Indeed, Sell and Testa (2020) found that first-year college women with a history of sexual victimization were more likely to report bringing their own beverages to parties. It follows that drinking in controlled environments with one’s own beverages before going to parties or other events may also increase after IR, although this possibility has not yet been examined.

Prepartying, which is also known as front-loading, pre-drinking, pre-funking, pre-gaming, or pre-loading, involves drinking before going out to the main social event (for review, see Foster & Ferguson, 2014). Prepartying is a common drinking practice during college (Zamboanga & Olthuis, 2016) in both women and men (DeJong et al., 2010; Reed et al., 2011). In addition to increasing situational control over the type or quantity of alcohol consumed, students engage in prepartying for many reasons, including lower cost and greater access to alcohol. For example, students under age 21 may not be able to purchase alcohol at the main social event. Individuals may also be motivated to preparty in order to increase sociability or the likelihood of hooking up (Bachrach et al., 2012; Foster & Ferguson, 2014; Labhart & Kuntsche, 2017; LaBrie et al., 2012). Motives for prepartying appear to be distinct from general drinking motives (e.g., LaBrie et al., 2012) and have been found to predict the frequency and quantity of preparty drinking (Bachrach et al., 2012). Understanding who is at greater risk for prepartying and the motivations for doing so in the context of IR may be important to inform intervention efforts.

Regardless of motives, prepartying can result in negative outcomes. Specifically, this risky drinking practice is associated with heavier drinking, greater intoxication, and alcohol-related consequences (Kenney et al., 2010; LaBrie & Pedersen, 2008; Paves et al., 2012; Pederson & LaBrie, 2007), including blackouts (LaBrie et al., 2011), which in turn have been associated with risk for sexual revictimization (Valenstein-Mah et al., 2015). Thus, it is possible that prepartying may also increase risk for IR. Relatedly, college women who more frequently brought their own beverages to parties had a greater risk of subsequent sexual victimization (Sell & Testa, 2020). Thus, those with a history of IR may drink in ways that aim to increase safety, but inadvertently increase risk for consequences, including revictimization. This, however, has yet to be examined in relation to prepartying.

To address these gaps, we sought to examine prepartying as both a risk factor and consequence of IR among college women and men in two studies. In the first study, we examined cross-sectional associations between IR, prepartying behavior, and prepartying motives. Then, in the second study, we prospectively examined the link between IR and prepartying behavior across one year. Finally, although men experience non-ignorable rates of IR victimization (Peterson et al., 2011), most research on IR has focused on women and societal messages suggest women bear the burden of protecting their drinks in public. Thus, we also explored gender differences in associations between IR and prepartying. Clarifying how past experiences of IR affect the manner and motivations for risky drinking, which may in turn increase IR risk among women and men, is of critical importance for college prevention and intervention efforts targeting both IR and alcohol use.

Study 1: Cross-Sectional Study of Prepartying Motives

In Study 1, we evaluated the cross-sectional associations between IR and prepartying. Consistent with research revealing that individuals with a history of IR report heavier drinking and more alcohol-related consequences including blackouts than individuals without a history of IR (Kaysen et al., 2006; Marx et al., 2000; Nguyen et al., 2010; Voloshyna et al., 2018), we hypothesized that IR would be associated with more alcohol consumption and resulting blackouts when prepartying. Additionally, we hypothesized that a recent history of IR in the past year would be associated with prepartying specifically to increase safety through situational control while drinking. We also explored associations between IR and other prepartying motives, including prepartying to be social (i.e., interpersonal enhancement), to hookup (i.e., intimate pursuit), and in anticipation of barriers to consumption at the main social event. Finally, we explored whether associations between IR history and preparty drinks consumed, blackout frequency, and motives would differ between women and men.

Materials and Methods

Participants and Procedure

Participants in Study 1 were college students originally recruited for a randomized controlled trial (RCT) testing the efficacy of a norms-based alcohol harm-reduction intervention (Larimer et al., 2021). A random subset of students (N = 5,998) were invited into the study via email from two US universities: Campus 1 (n = 2,998 invited) is a large public university in the Pacific Northwest, and Campus 2 (n = 3,000 invited) is a mid-sized private university on the West Coast. In total, 2,767 (46.1%) completed the screening survey, 1,494 (54.0%) students met the inclusion criteria of one past-month heavy episodic drinking occasion (HED; 4+/5+ drinks for women/men), and 1,367 (91.5%) elected to enroll into the RCT. Participants were randomized to one of six conditions, including a minimal assessment control condition that entailed a shortened baseline survey, which did not assess prepartying. Thus, the 230 participants randomized to minimal assessment were not included in the current study, leaving a sample of 1,137 students. Note that data analyzed herein are from the baseline survey (the only survey with prepartying items) and are thus not subject to any treatment effects. Given the focus on gender and the importance of sex assigned at birth for interpreting alcohol consumption, two individuals identifying as transgender were excluded from analysis. Additionally, one participant was excluded for missing IR data. Because the majority of the sample reported a lifetime history of prepartying (94.7%), there were no differences in lifetime prepartying by IR, χ2(1) = 0.34, p = .561, and prepartying information was only assessed for those who had ever prepartied, 60 participants who had never prepartied were excluded from analyses.

The final analytic sample for Study 1 was 1,074 college students. Participants were on average 20.14 years old (SD = 1.36) and 63.8% were women. Regarding racial identity, 67.6% were White, 12.7% Asian, 11.4% multiracial, 2.6% Black/African American, 2.0% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, 0.5% American Indian/Alaskan Native, and 3.2% Other. Regarding sexual identity, 95.7% identified as straight/heterosexual, 2.0% bisexual, 1.6% gay/lesbian, and 0.7% questioning. Participants were compensated $15 for screening and $25 for baseline surveys. This RCT received institutional review board approval from both universities where data were collected, and no adverse outcomes were reported.

Measures

Incapacitated Rape.

One item from the Young Adult Alcohol Problems Screening Test (YAAPST; Hurlbut & Sher, 1992) was used to assess individual’s history of alcohol-related IR, consistent with past research (Jaffe, Blayney, et al., 2021; Kaysen et al., 2006; Nguyen et al., 2010). Specifically, participants were asked, “Have you ever been pressured or forced to have sex with someone because you were too drunk to prevent it?” For the current study, we focused on the presence of past-year IR as being most proximal to recent drinking behavior. Thus, responses were dichotomized such that history of past-year IR was indicated by a response of one, two, or three or more times in the past year (IR = 1) and no IR indicated by a response of no, never or yes, but not in the past year (IR = 0).

Prepartying Behavior.

Prepartying was defined for participants as “the consumption of alcohol prior to attending an event or activity [e.g., party, bar, concert] at which more alcohol may or may not be consumed” (LaBrie et al., 2012). Lifetime prepartying was assessed at baseline by asking if they have ever engaged in this behavior (response options: 0 = No, 1 = Yes). Those who said yes were then asked about past month (30-day) prepartying behavior, including how many days they engaged in prepartying, and how many drinks they consumed while prepartying (this value was winsorized at 3 standard deviations above the mean [12 drinks in the current sample]). To determine the number of drinks consumed while prepartying in the past month, the number of days prepartying was multiplied by the number of drinks typically consumed while prepartying for a quantity-frequency index.

To assess blackout frequency in the past month, participants who had prepartied in the past month were asked if they had ever blacked out (defined for participants as “you can’t remember all or part of the night”) on a night when they were prepartying (response options: 0 = No, 1 = Yes), and if yes, the number of times blacked out when prepartying in the past month (possible range: 0 to 30 times). One variable was computed to represent frequency of blackouts related to prepartying in the past month, where frequency was assumed to be zero for those with no past-month prepartying or no prepartying-related blackouts.

Prepartying Motives.

Prepartying motives were assessed using the Prepartying Motives Inventory (see LaBrie et al., 2012 for split-half psychometric analyses conducted within the current sample), a 16-item scale with various reasons why people engage in prepartying behaviors. Participants were asked to indicate to what extent they prepartied for each of the listed reasons with answer choices ranging from 1 = Almost Never/Never to 5 = Almost Always/Always. A mean score was computed for each of four subscales: Situational Control (e.g., “So I don’t have to worry about whether someone has tampered with the drinks at a party”; “So I don’t have to drink at the place where I’m going”; 4 items; α = .75), Interpersonal Enhancement (e.g., “To meet new people once I go out”; 6 items; α = .89), Intimate Pursuit (e.g., “To meet a potential dating partner once I go out”; 3 items; α = .82), and Barriers to Consumption (e.g., “Because alcohol may not be available or may be hard to get at the destination”; 3 items; α = .78).

Results

Descriptives

In all, 8.8% of participants reported a past-year IR (n = 95), including 9.8% of women (n = 67) and 7.2% of men (n = 28), χ2(1) = 2.05, p = .152. There was no difference in past-year IR by campus (Campus 1: 7.7%; Campus 2: 10.2%), χ2(1) = 2.07, p = .150. In the past month, 91.2% of participants reported prepartying, and 31.4% reported at least one blackout related to prepartying.

Unconditional Associations between IR and Prepartying

Bivariate differences (see Table 1) revealed past-year IR was associated with more alcohol consumption and more frequent blackouts when prepartying. Additionally, all prepartying motives were higher among individuals with a past-year IR.

Table 1.

Differences in Prepartying Behavior and Motives by History of Past-Year Incapacitated Rape

| Variable | Study 1 |

Study 2 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall N = 1,074 | Past-Year IR | p | Overall N = 1,751 | Past-Year IR at Baseline | p | |||

| No n = 979 | Yes n = 95 | No n = 1,636 | Yes n = 115 | |||||

| Concurrent Assessment | ||||||||

| Preparty drinks in past month | 21.44 (25.70) | 19.90 (22.95) | 37.38 (42.15) | <.001 | 15.70 (20.70) | 15.04 (19.21) | 25.17 (34.46) | .002 |

| Preparty blackouts in past month | 0.65 (1.40) | 0.55 (1.13) | 1.65 (2.78) | <.001 | 0.40 (1.04) | 0.37 (0.97) | 0.86 (1.65) | .002 |

| Situational control motives | 2.26 (0.96) | 2.24 (0.96) | 2.50 (0.96) | .013 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Interpersonal enhancement motives | 2.91 (1.03) | 2.88 (1.03) | 3.22 (1.02) | .002 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Intimate pursuit motives | 1.65 (0.87) | 1.59 (0.81) | 2.30 (1.15) | <.001 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Barriers to consumption motives | 2.53 (1.14) | 2.48 (1.12) | 3.06 (1.15) | <.001 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 12-Month Follow-up Assessment | ||||||||

| Past-year IR | -- | -- | -- | -- | 4.8% (72) | 4.2% (59) | 13.4% (13) | <.001 |

| Preparty drinks in past month | -- | -- | -- | -- | 11.25 (17.77) | 11.21 (17.99) | 11.81 (14.18) | .692 |

| Preparty blackouts in past month | -- | -- | -- | -- | 0.33 (0.95) | 0.32 (0.93) | 0.49 (1.14) | .150 |

Note. IR = Incapacitated Rape. Percentage or mean (standard deviation) are shown. P values reflect the significance of chi-square test of independence for Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables (i.e., past-year IR at follow-up) and Welch’s t-test for continuous variables (i.e., all other variables). Bolded values are significantly different at p < .05. One participant in Study 1 was missing data on blackout frequency. A different participant in Study 1 was missing data on two of four items within the situational control motives scale; thus, a mean value was not computed for this participant. Two participants in Study 2 were missing past-year IR data at baseline and excluded from examination of bivariate associations.

Conditional Associations and Gender Differences

Controlling for campus and age differences, we examined whether the association between IR and prepartying behavior differed by gender. Specifically, separate negative binomial regression analyses were estimated in R using the glm.nb function from the MASS package (Venables & Ripley, 2002) to predict past-month prepartying drinks (range: 0 to 240) and blackouts (range: 0 to 20). As shown in Table 2, IR was associated with 73% more preparty drinks and 180% more preparty blackouts in the past month. Men reported consuming 32% more drinks when prepartying than women. However, the association between IR and prepartying drinks or blackouts did not significantly differ by gender.

Table 2.

Cross-Sectional Predictors of Prepartying Drinks, Blackouts, and Motives in Study 1

| Preparty Drinks |

Preparty Blackouts |

Situational Control Motives |

Interpersonal Enhancement Motives |

Intimate Pursuit Motives |

Barriers to Consumption Motives |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | IRR | 95% CI | p | IRR | 95% CI | p | B | SE | p | B | SE | p | B | SE | p | B | SE | p |

| Campus (1 vs. 2) | 0.76 | 0.66 – 0.87 | <.001 | 0.80 | 0.62 – 1.03 | .075 | −0.27 | 0.06 | <.001 | −0.13 | 0.06 | .046 | −0.18 | 0.05 | .001 | −0.21 | 0.06 | .001 |

| Age | 0.88 | 0.84 – 0.93 | <.001 | 0.96 | 0.88 – 1.06 | .421 | −0.10 | 0.02 | <.001 | −0.13 | 0.02 | <.001 | −0.07 | 0.02 | .001 | −0.39 | 0.02 | <.001 |

| Gender (Man vs. Woman) | 1.32 | 1.14 – 1.52 | <.001 | 1.19 | 0.92 – 1.55 | .190 | −0.32 | 0.06 | <.001 | 0.05 | 0.07 | .498 | 0.45 | 0.06 | <.001 | −0.13 | 0.06 | .032 |

| IR (Yes vs. No) | 1.73 | 1.33 – 2.30 | <.001 | 2.80 | 1.82 – 4.44 | <.001 | 0.16 | 0.13 | .191 | 0.31 | 0.13 | .016 | 0.59 | 0.12 | <.001 | 0.43 | 0.14 | .001 |

| Gender * IR | 1.28 | 0.79 – 2.14 | .330 | 1.28 | 0.59 – 2.88 | .542 | 0.07 | 0.22 | .741 | −0.03 | 0.23 | .883 | 0.38 | 0.28 | .179 | 0.03 | 0.24 | .891 |

Note. Three separate models were estimated: (1) preparty drinks (N = 1,073), (2) preparty blackouts (N = 1,072), and (3) a multivariate model in which all motives (situational control, interpersonal enhancement, intimate pursuit, barriers to consumption) were allowed to covary (N = 1,073). One participant was missing data on age and therefore excluded from the models; another participant was missing data on blackouts. Standardized covariances (i.e., correlations) between prepartying motives ranged from .28 to .50 (all ps < .001). Bolded values are significantly different at p < .05.

Next, we examined whether the association between IR and prepartying motives differed by gender. Within a path model estimated via Mplus v.8.6 (Muthén & Muthén, 2021) and the MplusAutomation package in R (Hallquist & Wiley, 2018), all prepartying motives were included as outcomes allowed to covary (correlations ranged from .23 to .50, all ps < .001). Model results are also reported in Table 2. Controlling for campus and age, there was a main effect of past-year IR on greater motives for interpersonal enhancement, intimate pursuit, and barriers to consumption, but not situational control. Men reported lower situational control and barriers to consumption motives, but greater intimate pursuit motives. There was no IR-by-gender interaction on any prepartying motives.

Summary

Overall, Study 1 findings suggest IR was associated with more prepartying and the related consequence of blacking out. Although all motives were higher among individuals with IR in bivariate associations, multivariate tests allowing covariances between motives and controlling for campus, age, and gender revealed that past-year IR was not associated with situational control motives. Given the limits of cross-sectional data, this raises questions about whether prepartying increases as a safety behavior following IR as anticipated, or primarily serves as a risk factor for IR.

Study 2: Prospective Study of IR and Prepartying Behaviors

Building on Study 1, we examined prospective associations between IR and prepartying drinks and blackouts at two timepoints separated by 12 months in Study 2. Past findings on prospective associations between alcohol use and sexual assault have been mixed. Some studies have found support for reciprocal links such that alcohol use increases risk for sexual assault and sexual assault in turn increases risk for heavier alcohol use (Bryan et al., 2016; Kaysen et al., 2006), others indicate that drinking only increases risk for sexual assault (Dardis et al., 2021; Gidycz et al., 2007; McCauley et al., 2010; Mouilso et al., 2012; Testa & Livingston, 2000), and still others indicate sexual assault only leads to subsequent increases in alcohol use (Norris et al., 2019; Parks et al., 2014). Given these bidirectional associations between sexual assault and drinking over time, we hypothesized that past-year IR would be associated with more subsequent prepartying and related blackouts. Additionally, we hypothesized that alcohol consumption and blackout frequency related to prepartying would be associated with a greater risk for experiencing IR in the subsequent year.

Materials and Methods

Participants and Procedure

Participants in Study 2 were enrolled in a longitudinal RCT study examining relative efficacy of eight norms-based intervention conditions (LaBrie et al., 2013). The parent study invited 11,069 college students from the same two universities described in Study 1 to complete the screening survey (completed by 4,818 students [43.5%]). Inclusion criteria were at least one past-month HED occasion, and identifying as either Caucasian or Asian (to allow for the provision of personalized feedback with the normative referent as the same race/ethnicity). In total, 2,034 (42.2%) students were eligible, 1,831 (90.0%) completed baseline, and 1,7601 (96.1%) were ultimately randomized into one of 11 conditions including two control conditions, eight personalized normative feedback conditions with varying normative referents (e.g., same race/ethnicity), and one condition entailing a web-delivered Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS; Dimeff et al., 1999). Given the focus on gender and the importance of sex assigned at birth for interpreting alcohol consumption, 7 individuals identifying as transgender were excluded from analysis.

The final analytic sample was 1,753 college students. Participants were on average 19.93 years old (SD = 1.33), and 56.6% were women. Regarding racial identity, 76.1% were White and the remaining 23.9% were Asian. Regarding sexual identity, 96.5% identified as straight/heterosexual, 1.5% bisexual, 1.7% gay/lesbian, and 0.3% questioning. Although the parent study entailed several follow-ups, this secondary data analysis focuses only on baseline and 12-month follow-up data, as the item pertaining to IR asked about experiences over the past year. Participants were compensated $25 for baseline and $40 for the 12-month follow-up. The parent RCT received institutional review board approval from both universities where data were collected, and no adverse outcomes were reported.

Measures

Incapacitated Rape.

Past-year alcohol-related IR was assessed at baseline and the 12-month follow-up. The assessment and recoding of IR matched Study 1.

Prepartying Behavior.

As in Study 1, prepartying was first defined for participants. Then, all participants were asked how many days they engaged in prepartying in the past month, and how many drinks, on average, they typically consumed while prepartying (this value was winsorized at 3 standard deviations above the mean [9 drinks in the current sample]). The total number of drinks consumed while prepartying in the past month was computed by multiplying the number of days prepartying by the number of drinks typically consumed while prepartying. Past-month frequency of blackouts on nights when prepartying was also assessed in the same manner as in Study 1.

Results

Descriptives

At baseline, 6.6% of participants reported a past-year IR (n = 115), including 8.0% of women (n = 79) and 4.7% of men (n = 36), χ2(1) = 7.34, p = .007. There was no difference in past-year IR by campus (Campus 1: 6.3%; Campus 2: 7.0%), χ2(1) = 0.29, p = .589. In the past month, 81.3% reported prepartying on at least one day and 21.6% reported at least one blackout related to prepartying.

As described in detail elsewhere (LaBrie et al., 2013), 84.7% of participants were randomly assigned to an online alcohol intervention, with the remaining participants assigned to a control condition. Individuals assigned to treatment were overrepresented at Campus 1 (86.0%) relative to Campus 2 (82.3%), χ2(1) = 4.26, p = .039.2 However, assignment to treatment did not differ by baseline reports of past-year IR, past-month prepartying or blackouts, or gender (all ps > .153).

The majority of participants (85.6%) completed the 12-month follow-up assessment (n = 1,501). Follow-up rates at Campus 1 (87.1%) were higher than Campus 2 (83.1%), χ2(1) = 5.28, p = .022. There were no significant differences in follow-up rates by baseline reports of past-year IR, preparty drinks or blackouts, gender, or assignment to treatment (all ps > .173).

At the 12-month follow-up, 4.8% of participants reported a past-year IR (n = 72), including 4.8% of women (n = 41) and 4.8% of men (n = 31), χ2(1) < 0.001, p = .976. In the month before the follow-up, 68.8% prepartied on at least one day and 18.9% had a related blackout.

Unconditional Associations

Bivariate differences (see Table 1) revealed past-year IR was associated with more drinks consumed and more frequent blackouts when prepartying when assessed concurrently. However, there were no significant differences in follow-up reports of prepartying based on IR history at baseline. Additionally, Fisher’s exact test revealed that individuals who reported a past-year IR at baseline were more likely to report IR at follow-up (13.4%) than individuals who did not have a history at baseline (4.2%), p < .001.

Conditional Associations and Prospective Prediction

A path model was estimated in Mplus using MplusAutomation in R. Specifically, intent-to-treat analyses were conducted by using maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors (MLR) and allowing all exogenous variables to covary. Differences in the efficacy of treatment by IR status are reported elsewhere (Jaffe, Blayney, et al., 2021). Given that treatment differences were not a central focus here but may have led to differences in prepartying behaviors, we included a covariate to control for the receipt of any treatment (PNF or Web-BASICS). In addition, campus, age, and gender were included as covariates. Number of past-month prepartying drinks and frequency of past-month prepartying blackouts were considered count variables with negative binomial distributions at 12 months. History of any past-year IR at 12-months was considered categorical and modeled with a logit link.

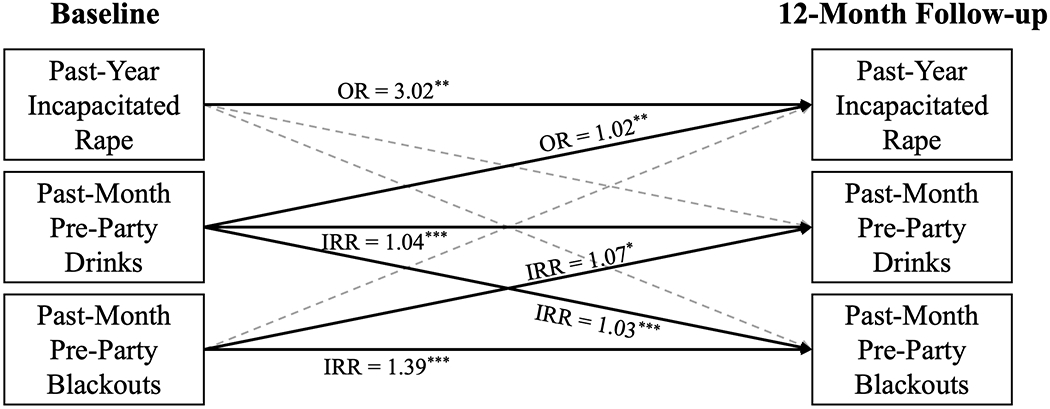

As shown in Table 3 and Figure 1, analyses revealed that risk for IR during the follow-up year was higher for individuals who indicated at baseline they had experienced a past-year IR and consumed more preparty drinks. Of note, gender was not a unique predictor of IR during the follow-up year. Preparty drinks and blackouts at baseline were both significant predictors of preparty drinks and blackouts at follow-up. There was not a significant effect of treatment on prepartying behavior, and men reported significantly more prepartying drinks at follow-up than women. After controlling for baseline prepartying behavior and covariates (campus, age, gender, and randomly assigned condition), IR at baseline was not a significant predictor of prepartying drinks or blackouts at follow-up.

Table 3.

Prospective Predictors of Preparty Drinks and Blackouts and IR in Study 2

| Follow-up Past-Year IR |

Preparty Drinks at Follow-Up |

Preparty Blackouts at Follow-up |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | OR | 95% CI | p | IRR | 95% CI | p | IRR | 95% CI | p |

| Campus (1 vs. 2) | 1.38 | 0.80 – 2.80 | .245 | 0.76 | 0.66 – 0.91 | <.001 | 0.87 | 0.66 – 1.24 | .317 |

| Age | 0.86 | 0.70 – 1.13 | .159 | 0.81 | 0.76 – 0.87 | <.001 | 0.78 | 0.70 – 0.90 | <.001 |

| Gender (Man vs. Woman) | 0.91 | 0.54 – 1.81 | .732 | 1.26 | 1.10 – 1.51 | .001 | 1.11 | 0.84 – 1.60 | .482 |

| Condition (Intervention vs. Control) | 1.33 | 0.63 – 3.56 | .456 | 0.83 | 0.68 – 1.06 | .048 | 0.79 | 0.57 – 1.22 | .166 |

| Baseline Past-Year IR | 3.02 | 1.54 – 7.31 | .001 | 0.92 | 0.67 – 1.42 | .635 | 1.01 | 0.66 – 1.79 | .961 |

| Baseline Preparty Drinks | 1.02 | 1.01 – 1.03 | .001 | 1.04 | 1.03 – 1.04 | <.001 | 1.03 | 1.02 – 1.04 | <.001 |

| Baseline Preparty Blackouts | 1.05 | 0.88 – 1.32 | .595 | 1.07 | 1.01 – 1.16 | .025 | 1.39 | 1.24 – 1.61 | <.001 |

Note. OR = odds ratio; IRR = incidence rate ratio; CI = confidence interval. All outcomes were estimated simultaneously in a single model (N = 1,753).

Figure 1.

Prospective Analysis of Prepartying Behaviors and IR in Study 2.

Note. OR = odds ratio; IRR = incidence rate ratio; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001. Gray dashed lines are non-significant. Baseline covariates of campus, age, gender, and condition were estimated, but are not depicted for simplicity. See Table 3 for full model results.

Discussion

This study is the first known investigation of the link between IR and prepartying. Two studies of college student drinkers from two US universities revealed a consistent pattern of findings. When assessed concurrently in both studies, past-year IR was associated with recent prepartying behavior, such that IR survivors reported more past-month drinks consumed in the context of prepartying and experienced blackouts more often than participants without a history of past-year IR. Extending prior work linking IR to alcohol use and consequences (Kaysen et al., 2006; Voloshyna et al., 2018), this finding suggests that IR has a particular association with risky drinking in anticipation of the main social event.

Study 1 also sheds light on reasons for prepartying in the context of recent IR. Concerns about drink spiking are high among college students, despite such occurrences being extremely rare (Burgess et al., 2009). We anticipated that a recent experience of IR may further sensitize college students to this fear, and in turn increase motivations to maintain situational control over one’s beverages by prepartying. Bivariate associations supported this hypothesis, such that situational control motives were significantly higher among participants with a past-year IR history than those without this history. However, after controlling for campus and gender differences, and allowing covariances between all motives, this association was no longer significant. It is notable, however, that women reported higher situational control motives than men, consistent with prior research documenting gender differences in general fear of crime as driven by fear of sexual assault (Ferraro, 1996; Prego-Meleiro et al., 2021), such that concern about drink spiking is more salient for women than men (Burgess et al., 2009). This suggests that concern about drink spiking and fear of sexual assault may still be an important motivator for prepartying, but gender is a more salient driver of this concern than IR history.

Beyond situational control, we explored other differences in prepartying motives. In both unconditional and conditional associations, individuals with a past-year IR history reported higher motivations for prepartying across all other motives, including to socialize (interpersonal enhancement), hookup (intimate pursuit), and avoid barriers to drinking at the main social event. Although this is the first known study to investigate prepartying motives in relation to IR, these findings can be interpreted in the larger context of research on drinking motives. For example, drinking to socialize has been associated with a history of IR (Bird et al., 2016; Marx et al., 2000). This link may reflect survivors’ attempt to overcome post-assault disruptions in social functioning (Resick et al., 1981) by using alcohol as a “social lubricant” (Monahan & Lannutti, 2000). Similarly, some survivors may experience anxiety in sexual situations after an assault and may be motivated to drink to reduce anxiety around sex (Bird et al., 2019). Beyond prepartying to navigate social situations, IR survivors also reported greater motivation to preparty out of concern about barriers to consumption at a main social event, even after controlling for age. This may reflect the relative importance of drinking for this sample of IR survivors, such that the threat of not being able to access alcohol at a main event leads to greater motivations to preparty. Of note, these motives were examined cross-sectionally and may have been heightened among this group of survivors long before the IR occurred. Thus, it is also possible that prepartying motives of interpersonal enhancement and intimate pursuit may have increased risk for drinking heavily within social and intimate settings. Because potential perpetrators may be encountered in these settings, prepartying as related to these motives may have increased risk for an IR. Thus, we turn to Study 2 to examine prospective associations between IR and prepartying next.

In Study 2, concurrent associations at baseline again supported a link between IR and prepartying. This suggests that, although Study 2 participants reported lighter prepartying behaviors than Study 1 participants on average, cross-sectional bivariate associations between IR and prepartying appeared to be consistent across studies. When prospective associations were examined in Study 2, a more nuanced picture emerged. Specifically, preparty drinking was found to be a prospective risk factor for IR, but IR was not associated with subsequent prepartying. Although others have reported reciprocal links between general alcohol use and sexual assault (Bryan et al., 2016; Kaysen et al., 2006), our findings are consistent with the majority of studies indicating that the most robust association is between drinking and risk for subsequent sexual assault (Dardis et al., 2021; Gidycz et al., 2007; McCauley et al., 2010; Mouilso et al., 2012; Testa & Livingston, 2000). Our findings also add generalizability by revealing findings extend to men (Kaysen et al., 2006), and specificity by highlighting an association between alcohol use and subsequent IR (Kaysen et al., 2006; McCauley et al., 2010). This is also the first known study to reveal that drinking specifically in the context of prepartying is a risk factor for subsequent IR. Nonetheless, few participants reported IR during the follow-up year, and additional research is needed to replicate findings in larger samples.

Of note, gender differences in IR were minimal, with a difference in prevalence at Study 2 baseline (8.0% women, 4.7% men), but not Study 2 follow-up (4.8% each) or Study 1 (9.8% women, 7.2% men). There were also no gender differences in associations between IR and more prepartying and related blackouts in Study 1, consistent with past work demonstrating cross-sectional associations between unwanted sexual contact and alcohol use and consequences in both college women and men (Larimer et al., 1999). Although this lack of a difference should be interpreted with some caution given the low base rates and subsequent small cell sizes, findings indicate the importance of understanding IR risk and recovery among college students of all genders. Future research is also needed to examine potential gender differences in the association between prepartying and sexual assault generally through the use of broader measures that assess sexual assault history in a gender-inclusive manner (e.g., Canan et al., 2020).

Limitations

Findings should be interpreted in the context of methodological limitations within this secondary analysis. First, assessment of IR was limited to a single item and should be more comprehensively assessed in future research. The prepartying motives examined were also limited in the current study, and could be expanded to motives assessed on other measures in the future (e.g., Pre-Gaming Motives; Bachrach et al., 2012; Pre-Drinking Motives Questionnaire; Labhart & Kuntsche, 2017). Second, in the prospective Study 2, the IR measure assessed past-year experiences, meaning we could only examine associations between baseline and a 12-month follow-up. Although regularly prepartying and consuming more drinks while prepartying was associated with IR in the following year, we anticipate the association between prepartying and IR risk is proximal within a given night. Event-level data are needed to better understand such risk. Similarly, this year-long follow-up may have been too long to observe more proximal changes in prepartying behavior after IR, so we suggest additional research to examine this possibility. Third, prepartying may be an indicator of heavy drinking in social contexts. Thus, we encourage future research to disentangle whether the context, manner, or motives for drinking are most predictive of IR risk to inform intervention efforts. Finally, caution should be used when generalizing findings. These analyses entailed a sample of relatively high-risk students with past-month HED for whom prepartying may be most likely; thus, results may not be applicable for light drinking or non-drinking students. Study 2 also excluded individuals who did not identify their race as White or Asian, and more diverse samples should be used to examine prospective associations in the future. Additionally, too few participants identified as transgender in the current studies to evaluate separately. Despite high rates of sexual victimization, IR in transgender and gender non-conforming young adults has been understudied (McCauley et al., 2018). We encourage oversampling this population to ensure representation in future research.

Conclusions

This was the first known study to show an association between IR and prepartying behaviors in college women and men. Although we anticipated IR would lead to increased concerns about safety when drinking and motivate subsequent prepartying, we found IR was cross-sectionally associated with preparty motivations to socialize, hookup, and anticipate barriers to consumption at a main social event – but not situational control. Further, alcohol use while prepartying increased risk for IR in the subsequent year, instead of the reverse. Findings highlight the need to address prepartying behaviors in alcohol-related interventions for college students to reduce risk for negative outcomes, including sexual assault.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; data collection and manuscript preparation were funded by R01/R37AA012547 (PI: Larimer); manuscript preparation was also supported by K08AA028546 (PI: Jaffe) and K99AA028777 (PI: Blayney). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Footnotes

The content of this paper has not been previously published, presented, or posted online. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Note that an additional 69 participants completed the baseline survey but encountered a survey programming error in randomization, so were not considered here. An additional 2 participants were excluded due to being research assistants in the lab.

The programming error in random assignment that led some participants to be excluded from analysis only affected Campus 1.

References

- Anderson LJ, Flynn A, & Pilgrim JL (2017). A global epidemiological perspective on the toxicology of drug-facilitated sexual assault: A systematic review. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 47, 46–54. 10.1016/j.jflm.2017.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachrach RL, Merrill JE, Bytschkow KM, & Read JP (2012). Development and initial validation of a measure of motives for pregaming in college students. Addictive Behaviors, 37(9), 1038–1045. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.04.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird ER, Stappenbeck CA, Neilson EC, Gulati NK, George WH, Cooper ML, & Davis KC (2019). Sexual victimization and sex-related drinking motives: how protective is emotion regulation? The Journal of Sex Research, 56(2), 156–165. 10.1080/00224499.2018.1517206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan AEB, Norris J, Abdallah DA, Stappenbeck CA, Morrison DM, Davis KC, George WH, Danube CL, & Zawacki T (2016). Longitudinal change in women’s sexual victimization experiences as a function of alcohol consumption and sexual victimization history: A latent transition analysis. Psychology of Violence, 6(2), 271–279. 10.1037/a0039411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess A, Donovan P, & Moore SE (2009). Embodying uncertainty? Understanding heightened risk perception of drink ‘spiking’. The British Journal of Criminology, 49(6), 848–862. 10.1093/bjc/azp049 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Canan SN, Jozkowski KN, Wiersma-Mosley J, Blunt-Vinti H, & Bradley M (2020). Validation of the sexual experience survey-short form revised using lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual women’s narratives of sexual violence. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(3), 1067–1083. 10.1007/s10508-019-01543-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dardis CM, Ullman SE, Rodriguez LM, Waterman EA, Dworkin ER, & Edwards KM (2021). Bidirectional associations between alcohol use and intimate partner violence and sexual assault victimization among college women. Addictive Behaviors, 116, 106833. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeJong W, DeRicco B, & Schneider SK (2010). Pregaming: An exploratory study of strategic drinking by college students in Pennsylvania. Journal of American College Health, 58(4), 307–316. 10.1080/07448480903380300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedina L, Holmes JL, & Backes BL (2018). Campus sexual assault: A systematic review of prevalence research from 2000 to 2015. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 19(1), 76–93. 10.1177/1524838016631129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro KF (1996). Women’s fear of victimization: Shadow of sexual assault? Social Forces, 75(2), 667–690. 10.1093/sf/75.2.667 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forsman RL (2017). Prevalence of sexual assault victimization among college men, aged 18–24: A review. Journal of Evidence-Informed Social Work, 14(6), 421–432. 10.1080/23761407.2017.1369204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster JH, & Ferguson C (2014). Alcohol ‘pre-loading’: A review of the literature. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 49(2), 213–226. 10.1093/alcalc/agt135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidycz CA, Loh C, Lobo T, Rich C, Lynn SJ, & Pashdag J (2007). Reciprocal relationships among alcohol use, risk perception, and sexual victimization: A prospective analysis. Journal of American College Health, 56(1), 5–14. 10.3200/JACH.56.1.5-14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallquist MN, & Wiley JF (2018). MplusAutomation: an R package for facilitating large-scale latent variable analyses in Mplus. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 25(4), 621–638. 10.1080/10705511.2017.1402334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlbut SC, & Sher KJ (1992). Young Adult Alcohol Problems Screening Test. PsycTESTS Dataset. 10.1037/t02795-000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe AE, Blayney JA, Graupensperger S, Stappenbeck CA, Bedard-Gilligan M, & Larimer M (2021). Personalized normative feedback for hazardous drinking among college women: Differential outcomes by history of incapacitated rape. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. Advance online publication. 10.1037/adb0000657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe AE, Kaysen D, Smith BN, Galovski T, & Resick PA (2021). Cognitive processing therapy for substance-involved sexual assault: Does an account help or hinder recovery? Journal of Traumatic Stress, 34(4), 864–871. 10.1002/jts.22674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaysen D, Neighbors C, Martell J, Fossos N, & Larimer ME (2006). Incapacitated rape and alcohol use: A prospective analysis. Addictive Behaviors, 31(10), 1820–1832. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.12.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney SR, Hummer JF, & LaBrie JW (2010). An examination of prepartying and drinking game playing during high school and their impact on alcohol-related risk upon entrance into college. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(9), 999–1011. 10.1007/s10964-009-9473-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Ruggiero KJ, Conoscenti LM, & McCauley JM (2007). Drug-facilitated, incapacitated, and forcible rape: A national study (NCJ 219181—Final Report). U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice. [Google Scholar]

- Krebs CP, Lindquist CH, Warner TD, Fisher BS, & Martin SL (2009). The differential risk factors of physically forced and alcohol-or other drug-enabled sexual assault among university women. Violence and Victims, 24(3), 302–321. 10.1891/0886-6708.24.3.302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labhart F, & Kuntsche E (2017). Development and validation of the predrinking motives questionnaire. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 47(3), 136–147. 10.1111/jasp.12419 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, & Pedersen ER (2008). Prepartying promotes heightened risk in the college environment: An event-level report. Addictive Behaviors, 33(7), 955–959. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Pedersen ER, Lac A, & Chithambo T (2012). Measuring college students’’ motives behind prepartying drinking: Development and validation of the prepartying motivations inventory. Addictive Behaviors, 37(8), 962–969. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Hummer J, Kenney S, Lac A, & Pedersen E (2011). Identifying factors that increase the likelihood for alcohol-induced blackouts in the prepartying context. Substance Use & Misuse, 46(8), 992–1002. 10.3109/10826084.2010.542229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Graupensperger S, Lewis MA, Cronce JM, Kilmer JR, Atkins DC, Lee CM, Garberson L, Walter T, Ghaidarov TM, Hummer JF, Neighbors C, & LaBrie JW (2021). Injunctive and descriptive norms feedback for college drinking prevention: Is the whole greater than the sum of its parts? [Manuscript submitted]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Lydum AR, Anderson BK, & Turner AP (1999). Male and female recipients of unwanted sexual contact in a college student sample: Prevalence rates, alcohol use, and depression symptoms. Sex Roles, 40(3), 295–308. 10.1023/A:1018807223378 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lawyer S, Resnick H, Bakanic V, Burkett T, & Kilpatrick D (2010). Forcible, drug-facilitated, and incapacitated rape and sexual assault among undergraduate women. Journal of American College Health, 58(5), 453–460. 10.1080/07448480903540515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luetke M, Giroux S, Herbenick D, Ludema C, & Rosenberg M (2020). High prevalence of sexual assault victimization experiences among university fraternity men. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. Advance online publication. 10.1177/0886260519900282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx BP, Nichols-Anderson C, Messman-Moore T, Miranda R Jr, & Porter C (2000). Alcohol consumption, outcome expectancies, and victimization status among female college students. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30(5), 1056–1070. 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2000.tb02510.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCauley HL, Coulter RW, Bogen KW, & Rothman EF (2018). Sexual assault risk and prevention among sexual and gender minority populations. In Orchowski LM & Gidycz CA (Eds.), Sexual assault risk reduction and resistance: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 333–352). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCauley JL, Ruggiero KJ, Resnick HS, & Kilpatrick DG (2010). Incapacitated, forcible, and drug/alcohol-facilitated rape in relation to binge drinking, marijuana use, and illicit drug use: A national survey. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 23(1), 132–140. 10.1002/jts.20489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore TL, & Long PJ (2003). The role of childhood sexual abuse sequelae in the sexual revictimization of women: An empirical review and theoretical reformulation. Clinical Psychology Review, 23(4), 537–571. 10.1016/S0272-7358(02)00203-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohler-Kuo M, Dowdall GW, Koss MP, & Wechsler H (2004). Correlates of rape while intoxicated in a national sample of college women. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 65(1), 37–45. 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monahan JL, & Lannutti PJ (2000). Alcohol as social lubricant: Alcohol myopia theory, social self-esteem, and social interaction. Human Communication Research, 26(2), 175–202. 10.1111/j.1468-2958.2000.tb00755.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mouilso ER, Fischer S, & Calhoun KS (2012). A prospective study of sexual assault and alcohol use among first-year college women. Violence and Victims, 27(1), 78–94. 10.1891/0886-6708.27.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998–2021). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen HV, Kaysen D, Dillworth TM, Brajcich M, & Larimer ME (2010). Incapacitated rape and alcohol use in White and Asian American college women. Violence Against Women, 16(8), 919–933. 10.1177/1077801210377470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris AL, Carey KB, Walsh JL, Shepardson RL, & Carey MP (2019). Longitudinal assessment of heavy alcohol use and incapacitated sexual assault: A cross-lagged analysis. Addictive Behaviors, 93, 198–203. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris AL, Carey KB, Walsh JL, Shepardson RL, & Carey MP (2019). Longitudinal assessment of heavy alcohol use and incapacitated sexual assault: A cross-lagged analysis. Addictive Behaviors, 93, 198–203. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.addbeh.2019.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks KA, Hsieh Y-P, Taggart C, & Bradizza CM (2014). A longitudinal analysis of drinking and victimization in college women: Is there a reciprocal relationship? Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 28(4), 943–951. 10.1037/a0036283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paves AP, Pedersen ER, Hummer JF, & LaBrie JW (2012). Prevalence, social contexts, and risks for prepartying among ethnically diverse college students. Addictive Behaviors, 37(7), 803–810. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen ER, & LaBrie J (2007). Partying before the party: Examining prepartying behavior among college students. Journal of American College Health, 56(3), 237–245. 10.3200/jach.56.3.237-246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen ER, & LaBrie J (2007). Partying before the party: Examining prepartying behavior among college students. Journal of American College Health, 56(3), 237–245. https://dx.doi.org/10.3200%2FJACH.56.3.237-246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson ZD, Voller EK, Polusny MA, & Murdoch M (2011). Prevalence and consequences of adult sexual assault of men: Review of empirical findings and state of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(1), 1–24. 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prego-Meleiro P, Montalvo G, Garcia-Ruiz C, Ortega-Ojeda F, Ruiz-Perez I, & Sordo L (2021). Gender-based differences in perceptions about sexual violence, equality and drug‑facilitated sexual assaults in nightlife contexts. Adicciones. Advance online publication. 10.20882/adicciones.1561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radomski S, Blayney JA, Prince MA, & Read JP (2016). PTSD and pregaming in college students: A risky practice for an at-risk group. Substance Use & Misuse, 51(8), 1034–1046. 10.3109/10826084.2016.1152497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed MB, Clapp JD, Weber M, Trim R, Lange J, & Shillington AM (2011). Predictors of partying prior to bar attendance and subsequent BrAC. Addictive Behaviors, 36(12), 1341–1343. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Calhoun KS, Atkeson BM, & Ellis EM (1981). Social adjustment in victims of sexual assault. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 49(5), 705–712. 10.1037/0022-006X.49.5.705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Ham M, & Burton FC (2005). Toxicological findings in cases of alleged drug-facilitated sexual assault in the United Kingdom over a 3-year period. Journal of Clinical Forensic Medicine, 12(4), 175–186. 10.1016/j.jcfm.2005.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sell NM, & Testa M (2020). Is bringing one’s own alcohol to parties protective or risky? A prospective examination of sexual victimization among first-year college women. Journal of American College Health. Advance online publication. 10.1080/07448481.2020.1791883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, & Livingston JA (2000). Alcohol and sexual aggression: Reciprocal relationships over time in a sample of high-risk women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 15(4), 413–427. 10.1177/088626000015004005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, & Livingston JA (2018). Women’s alcohol use and risk of sexual victimization: Implications for prevention. In Orchowski LM & Gidycz CA (Eds.), Sexual assault risk reduction and resistance: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 135–172). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Valenstein-Mah H, Larimer M, Zoellner L, & Kaysen D (2015). Blackout drinking predicts sexual revictimization in a college sample of binge-drinking women. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(5), 484–488. 10.1002/jts.22042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venables WN & Ripley BD (2002) Modern applied statistics with S (4th ed). New York. [Google Scholar]

- Voloshyna DM, Bonar EE, Cunningham RM, Ilgen MA, Blow FC, & Walton MA (2016). Blackouts among male and female youth seeking emergency department care. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 44(1), 129–139. 10.1080/00952990.2016.1265975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldner-Haugrud LK, & Magruder B (1995). Male and female sexual victimization in dating relationships: Gender differences in coercion techniques and outcomes. Violence and Victims, 10, 203–215. 10.1891/0886-6708.10.3.203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamboanga BL, & Olthuis JV (2016). What is pregaming and how prevalent is it among U.S. college students? An introduction to the special issue on pregaming. Substance Use & Misuse, 51(8), 953–960. 10.1080/10826084.2016.1187524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]