Abstract

Purpose:

This paper reports findings from a randomized controlled trial of a front-end diversion program for prison-bound individuals with property crime convictions, concurrent substance use problems, and no prior violent crime convictions.

Methods:

Two counties in Oregon participated in the trial, labeled “County A” and “County B.” Across counties, 272 individuals (mean age = 32.7 years; 67.6% male) were recruited and randomized to receive either the diversion program (Senate Bill 416 [SB416]) or probation as usual (PAU). The primary outcome was recidivism, defined as any arrest, conviction, or incarceration for a new crime within three years of diversion from prison.

Results:

In County A, SB416 did not outperform PAU on any recidivism outcome. However, in County B, SB416 yielded significantly greater improvements across various configurations of the arrest, conviction, and incarceration outcomes, relative to PAU.

Conclusions:

SB416 can yield reduced recidivism when implemented in a setting like County B, which when compared to County A, had fewer justice system resources and a limited history of cross-system collaboration. More research on SB416 is needed, including an examination of its mechanisms of change and its cost-effectiveness relative to standard criminal justice system processing.

Keywords: Diversion, Property crime, Substance use, Randomized controlled trial

1. Introduction

This report describes results from a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of a front-end diversion program for prison-bound individuals with prior property crime convictions, concurrent substance use problems, and no prior violent crime convictions. Over the past two decades in the United States, front-end diversion initiatives for specialized populations have become increasingly common. The popularity of these programs stems from concerns about burgeoning incarceration costs, prison overcrowding, and a growing emphasis on rehabilitative efforts within justice-system programming. In front-end diversion initiatives, individuals plead guilty to a charge and agree to engage in community-based services (e.g., intensive supervision, substance use treatment) in lieu of incarceration (Porter, 2010). Individuals with histories of non-violent property crime are a common target of these initiatives for two reasons. First, this group represents one-fifth to one-quarter of all individuals currently incarcerated in the United States (Carson, 2020). Second, data indicate that most criminal behavior exhibited by non-violent property offenders is related to substance use, such as seeking illicit drugs or obtaining resources illegally (i.e., via burglary or theft) to fund their use of drugs (Bronson, Stroop, Zimmer, & Berzofsky, 2017; Hayhurst et al., 2017; Vaugh, 2011; White & Gorman, 2000). Therefore, it is hypothesized that the most effective method of reducing criminal recidivism in this group might be via delivery of substance use treatment. Further, it is assumed that such treatment might be best delivered in the offenders’ natural environment, so it is positioned to address the individual-, family-, peer-, and neighborhood-related factors contributing to their use of illicit drugs. This assumption is supported by research linking community drug treatment engagement with reductions in crime (Bukten et al., 2011; Cox & Comiskey, 2011; Gossop, Marsden, Stewart, & Rolfe, 2000). Further, by decreasing reliance on incarceration as a punishment, such diversion programs have potential to decrease justice system costs (diversion programs typically cost less than incarceration) while also reducing prison overcrowding (Porter, 2010).

Comprehensive literature reviews indicate that diversion programs are generally effective at reducing substance use and/or recidivism relative to standard criminal justice system processing (Harvey, Shakeshaft, Hetherington, Sannibale, & Mattick, 2007; Hayhurst et al., 2019; Lange, Rehm, & Popova, 2011; Marlowe, 2010). At the same time, these reviews note that almost all studies of diversion programs lack strong methodological rigor. Indeed, existing studies are characterized by: (1) quasi-experimental or no control group designs, (2) small sample sizes, (3) high attrition rates, (4) lack of objective data on key outcomes, (5) relatively brief follow-up periods, and/or (6) reliance on completer versus intention-to-treat analyses (Harvey et al., 2007; Hayhurst et al., 2019; Lange et al., 2011). Thus, to enhance the rigor of work in this area, reviewers have called for randomized controlled evaluations of diversion programs with sound methodological features. Consistent with that call, the authors of this paper completed an RCT of Oregon’s Senate Bill (SB) 416 diversion program, which addresses all of the abovementioned methodological weaknesses. The details of SB416, and the genesis of the RCT, are described next.

Oregon’s SB416 program is a front-end prison diversion initiative for non-violent, repeat felony property offenders who have a substance use problem and motivation to change their behavior. SB416 was developed by state leaders seeking an alternative to prison for individuals who were committing property crimes, at least in part, to support their use of substances. In Oregon, guidelines for repeat felony property offenses mandate a prison sentence (i.e., presumptive prison). However, SB416 assumes that this population would be better served by resources in their local community, and that such diversion from prison would yield cost savings to the state. At the same time, state leaders believed that diversion should be reserved for individuals who demonstrate motivation to eliminate their substance use and offending behavior. Since the dispositional departure from a presumptive prison sentence would need to include a recommendation by a county’s District Attorney (DA), but the assessment of motivation would need to be conducted by Community Corrections (CC), SB416 requires a partnership to be developed between the DA and CC in a county, as well as other key system-level collaborators. Oregon’s Criminal Justice Commission (CJC) provided initial seed funding to develop and pilot SB416 in a single county that had a history of such partnering and was seeking to implement the diversion program. Results from that pilot were promising, and the CJC subsequently obtained funding from the Bureau of Justice Assistance to evaluate SB416 in a full-scale RCT. The DA of a second county requested that SB416 be brought there and agreed to be part of the study. The CJC contracted with the authors to conduct the RCT. To ensure consistent delivery of SB416 across the two counties, the authors first collaborated with the program developers to create an SB416 protocol manual, with a specified list of key stakeholders, clear program mission, detailed description of program delivery procedures, and well-defined outcomes.

1.1. SB416 stakeholders and mission

SB416 stakeholders include the Office of the DA, CC (known in some counties as Parole and Probation), the Courts, substance use treatment providers, and peer recovery mentoring services. The mission of SB416 is to reduce recidivism and protect the public by holding non-violent property offenders accountable to engage in intensive community supervision and case management, substance use treatment programming, and peer mentoring services, as well as providing direct access to employment services, housing, education, and transportation. This mission is driven by four core principles. (1) Stakeholders approach program participants with cross-system collaborative procedures to promote accountability and rehabilitation, within the legal limits of each stakeholder’s purview, working together to keep participants engaged in programming. (2) Stakeholders prioritize evidence-based decision making and programming. (3) Stakeholders establish clear roles and expectations, with the aim of building mutual trust that the other stakeholders in SB416 will execute their roles effectively. (4) Stakeholders communicate frequently to stay informed of each participant’s progress and collaborate on making decisions regarding each participant.

1.2. SB416 delivery

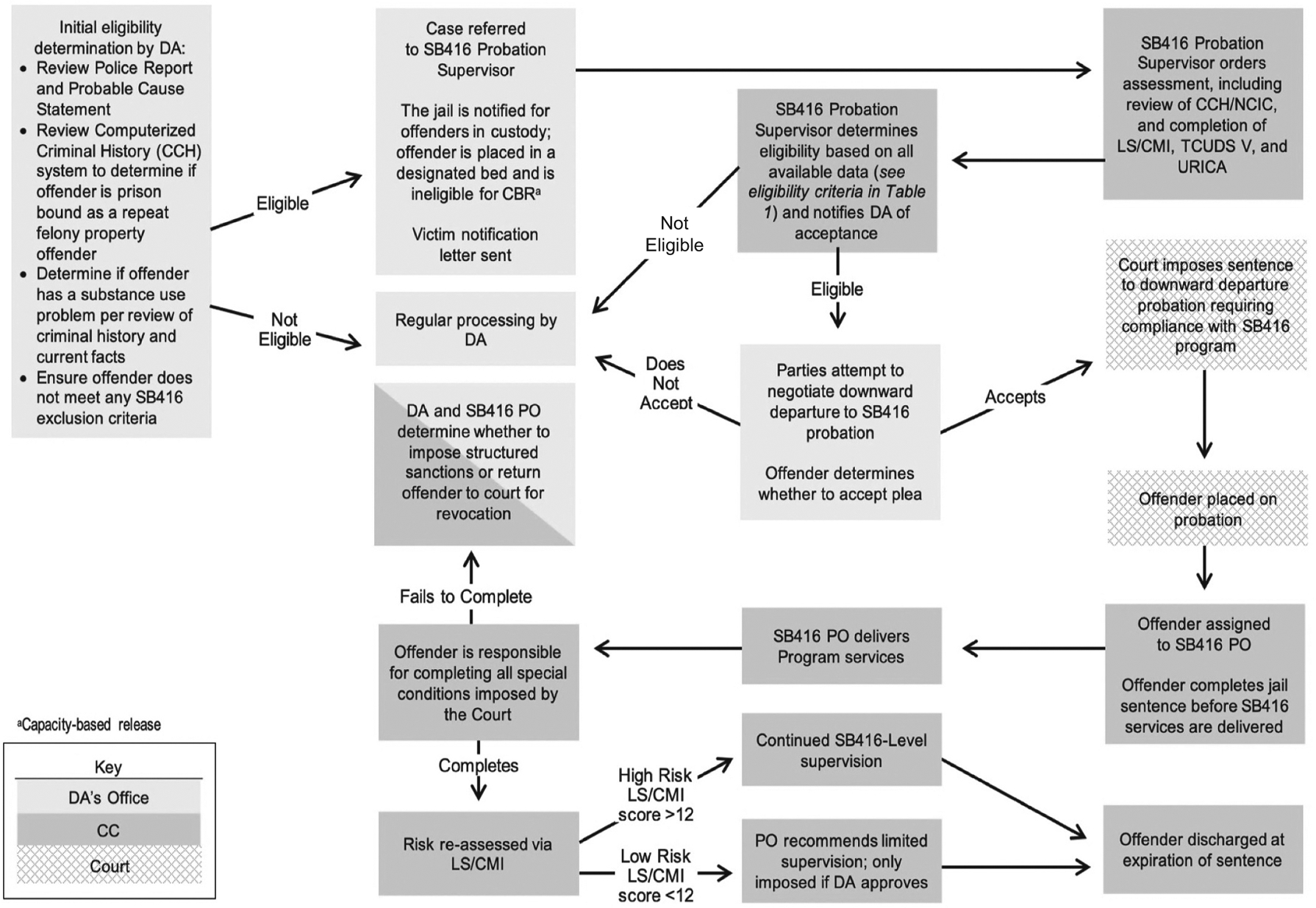

The process by which SB416 participants are identified by the DA, assessed for eligibility by CC, sentenced by the Court, and ultimately provided with program-level services is illustrated in Fig. 1 and summarized below.

Fig. 1.

Oregon Senate Bill (SB) 416 Program: Flow Diagram.

Note. DA= District Attorney, CC = Community Corrections, PO = Probation Officer, NCIC = National Crime Information Center, ISIS = Integrated Supervision Information System, LS/CMI = Level of Service/Case Management Inventory, TCUDS V = Texas Christian University Drug Screen V, URICA = University of Rhode Island Change Assessment.

1.2.1. Initial eligibility determination and case referral

The DA’s Office plays the role of gatekeeper by identifying candidates who satisfy the program’s inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Table 1). Once the DA’s Office deems an individual as potentially eligible, a referral is sent to an SB416 probation supervisor to coordinate an eligibility assessment. If the candidate is in custody and agrees (with legal counsel) to be considered for SB416, s/he is designated as ineligible for capacity-based release while assessment and determination of eligibility is conducted, and CC’s assessment is commenced as quickly as possible. In addition, the DA sends a letter to the victim(s) in the case notifying them about the candidate’s consideration for SB416.

Table 1.

Oregon Senate Bill (SB) 416 Program Eligibility Criteria.

| Inclusion Criteria |

|

| Automatic Exclusion Criteria |

|

| Other Considerations in Determining Ineligibility (Note: The following are not “rule outs” but, if present, are considered carefully before deeming an individual eligible) |

|

1.2.2. CC eligibility assessment

An intake coordinator at CC assesses candidates to determine their appropriateness. These assessments are completed within seven days of DA referral and include the following: (a) review of the candidate’s Computerized Criminal History (CCH)/National Crime Information Center (NCIC) file for statewide and out-of-state crimes; (b) Level of Service/Case Management Inventory (LS/CMI; Andrews, Bonta, & Wormith, 2004) to determine criminogenic risk factors; (c) University of Rhode Island Change Assessment (URICA; McConnaughy, Prochaska, & Velicer, 1983) to determine motivation for behavior change; and the (d) Texas Christian University Drug Screen V (TCUDS V; Institute of Behavioral Research, 2020) to determine severity of the candidate’s substance use. Based on all available information, the SB416 probation supervisor makes the final determination on whether the candidate is eligible for SB416 and conveys this decision to the DA.

1.2.3. Plea negotiations

When a candidate is deemed eligible for SB416, this determination is communicated to the individual’s defense attorney. The parties attempt to negotiate a downward departure to probation rather than prison time. If an agreement is reached, the individual pleads guilty to the charges s/he is required to plead to pursuant to the offer and proceeds to sentencing by the Court. Following sentencing, the individual completes his/her jail sentence, which begins at the point of arrest and initial booking at the jail, before SB416 services are initiated.

1.2.4. Supervision

All SB416 participants receive enhanced supervision from a dedicated probation officer (PO) with specialized training in the Effective Practices in Community Supervision (EPICS) model (Smith, Schweitzer, Labrecque, & Latessa, 2012). This nationally disseminated supervision approach, developed by the University of Cincinnati Corrections Institute, targets the needs of offenders using highly structured social learning and cognitive behavioral techniques. Thus, the SB416 PO must undergo training (generally 3 days), followed by a coaching period (generally 6 months) and ongoing quality assurance checks (i.e., audiotape reviews and feedback) to ensure s/he delivers EPICS with high fidelity.

Immediately after a participant is accepted into the SB416 program, the SB416 PO makes contact and holds a session. Like with all contacts, the EPICS model is used, and the focus is on identifying the criminogenic risk factors for the individual and methods for effectively addressing those factors. Besides the mandatory substance abuse treatment and the work of the SB416 mentor (described below), any employment, housing, education, and transportation needs are addressed using a case management approach. As such, and consistent with recommendations from experts (e.g., Caudy et al., 2015; Taxman, Caudy, & Pattavina, 2013), SB416 services are tailored to the participant’s specific criminogenic needs. This is preferred over a more rigid approach, where everyone receives the exact same intervention.

The SB416 PO’s caseload is capped at 60 cases to allow for regular contact with participants. The minimum number of contacts follows the requirement for probation services for medium/high risk offenders, which is 7 in-person contacts/6 months for medium-risk offenders and 15 in-person contacts/6 months for high-risk offenders. Periodic home visits also are required for medium and high-risk offenders, as well as when there are community complaints. Contacts never go below policy minimums; however, the SB416 PO often has more frequent contact initially, sometimes even daily contact for cases with high criminogenic risk factors. Participants sometimes ask for greater accountability or contact, and that is always accommodated. Frequency is reduced (but not below policy minimums) as SB416 participants demonstrate that they are compliant with all aspects of treatment, obtain and maintain employment, and sustain drug abstinence.

Throughout supervision, the SB416 PO actively collaborates with the DA’s Office. This includes providing updates on SB416 cases when problems arise or when information is requested. Email communication is the most frequent mode of contact, although in-person meetings and phone calls occur. As described below, the SB416 PO communicates weekly or more frequently with the treatment provider and mentors, so the PO has detailed information about each participant’s progress and special circumstances. This information is used by the DA to make appropriate decisions for ensuring community safety and participant accountability, while promoting participant rehabilitation.

Probation violations by SB416 participants are sanctioned swiftly following a structured sanctions grid that is used by all POs in Oregon. For example, 3–5 days in custody might be recommended for repeated substance use. The PO relies on administrative warrants to address minor violations. Other sanctions typically used are increasing frequency of PO contact and writing essays. In the event of a new law violation, the PO and DA collaborate to determine next steps. The decision to file an Order to Show Cause and return the case to Court is decided by the DA. Typically, this decision is based on the severity of the new crime, repeating the same crimes as prior to SB416 enrollment, the participant not taking accountability, and/or the participant’s motivation to change. The decision to revoke is ultimately decided by the Court. Conversely, when SB416 participants successfully complete all conditions imposed by the Court, they might be moved to limited supervision (pending DA approval and a “low risk” score on the LS/CMI) until expiration of their probation sentence.

1.2.5. Treatment

All SB416 participants receive treatment from a substance use provider in their community. Treatment costs are paid through insurance or contracted by CC. The provider is not required to implement a specific intervention; however, services must be classified as evidence-based by a reputable professional organization (e.g., Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, National Institute on Drug Abuse) and focus on both substance use and criminogenic risks. Treatment begins within 5–7 days of program start (or for participants in custody, 5–7 days after their release). Each treatment plan is developed in accordance with criteria established by the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM; Rastegar & Fingerhood, 2020), and also includes consideration of Risk-Need-Responsivity (RNR; Andrews, Bonta, & Wormith, 2011) and LS/CMI factors. Occasionally, SB416 participants require partial hospitalization (ASAM level 2.5) or placement in an inpatient/residential facility (ASAM level 3.5 or higher), although this is rare. More commonly, participants qualify for intensive outpatient treatment (ASAM level 2.1), with a typical service consisting of 3 group sessions per week; at least 1 individual session per month; and regular urine drug testing, with the frequency of testing ranging from 2 to 4 times per month to multiple times per week depending on the participant’s use history and substance(s) of choice.

The PO and treatment provider communicate weekly via phone, email, and/or in-person. In addition, the provider submits a summary on each SB416 participant on a monthly basis. The goal of these communications is to provide updates on case progress and to allow the PO and provider to collaboratively address problems, such as missed appointments or positive urine drug screens. SB416 participants complete treatment once they have met the goals on their treatment plan. Although those goals will vary across clients, participants must generally meet the following: (a) attendance at a minimum of 80% of treatment appointments (individual and group) during the last 90 days of treatment; (b) completion of all treatment assignments; (c) abstinence as documented by observed drug screens for a minimum of the last 90 days of treatment; (d) completion of a relapse prevention plan; and (e) confirmation by the PO that the participant has demonstrated improved behavioral functioning as evidenced by no probation violations and engagement in school, work, and/or other prosocial activities.

1.2.6. Mentoring

SB416 participants are assigned a mentor of the same gender. These are paraprofessionals who, at a minimum, have a high school diploma/GED and have been designated as a Certified Recovery Mentor by the Addiction Counselor Certification Board of Oregon. Mentors might be employed by the substance abuse treatment provider or by another agency in the community. The mentor makes initial contact with the SB416 participant 1–2 days after program entry to establish rapport and identify the participant’s needs in key domains (e.g., housing, food, clothing, transportation, employment, health care). After the primary needs are identified, the mentor meets regularly with the participant (often 2–3 times per week at first) to address those needs through informational resources and community referrals. In addition, once the participant initiates substance use treatment, the mentor engages in activities aimed at enhancing the likelihood of positive outcomes. Specifically, the mentor transports the participant to the initial clinic intake appointment, attends regular staffing meetings with the clinical team, and assists the team in developing treatment plans and intervention strategies. The mentor ensures participants attend all treatment sessions and provides access to transportation to those sessions as needed. In addition, the mentor supports the work of the treatment provider by continuously encouraging participants to utilize their drug avoidance and refusal skills, and also by finding opportunities to model pro-social thinking and behavior. Of importance, the mentor is in frequent communication with the treatment provider and SB416 PO. These communications occur weekly via phone, email, and/or in-person, and can also take place more frequently as needed. SB416 mentoring concludes at the end of treatment.

1.2.7. Targeted outcomes

The primary goal of SB416 is reduced recidivism, defined in accordance with SB 366 Section 1 (2015) (codified in Oregon Revised Statutes [ORS] 423.557). As used in that section, recidivism refers to any arrest, conviction, or incarceration for a new crime within three years of prison release or the point of diversion from prison.

1.3. Current study

An RCT of SB416 was conducted by researchers independent of SB416 developers and the individuals delivering the program. As noted, two Oregon counties participated, hereafter referred to as “County A” and “County B.” Across both counties, the RCT compared SB416 to probation as usual (PAU) for medium/high risk offenders, with randomization at the participant level. Archival arrest, conviction, and incarceration records for approximately three years post-randomization were obtained from state databases. Study hypotheses were as follows:

Participants receiving SB416 will exhibit a lower likelihood of arrest, conviction, and incarceration relative to participants receiving PAU.

Participants receiving SB416 will exhibit a lower count of arrests, convictions, and convictions leading to incarceration relative to participants receiving PAU.

Participants receiving SB416 will exhibit greater time to arrest, conviction, and incarceration relative to participants receiving PAU.

2. Method

2.1. Participants and recruitment

Study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the authors’ institution. Recruitment for the RCT began in November 2015 and ended in November 2019. To prevent coercion, recruitment occurred after the participant had been provided a downward departure sentence and was placed on probation (i.e., the candidate also had already been deemed eligible for possible participation in SB416 [see Table 1 and Fig. 1]). Staff working within CC at Counties A and B were trained in research ethics and learned how to explain the RCT and solicit informed consent. The CC staff described the study in detail, emphasized the voluntary nature of participation, and indicated that participants could terminate involvement in the study at any time. Specifically, individuals were consenting (a) to be randomized to SB416 or standard PAU for medium/high risk offenders and (b) to allow their justice-related records to be used in the study. Importantly, participation or refusal to participate did not affect the individual’s sentence; the downward departure sentence had already been implemented and was not contingent on study participation.

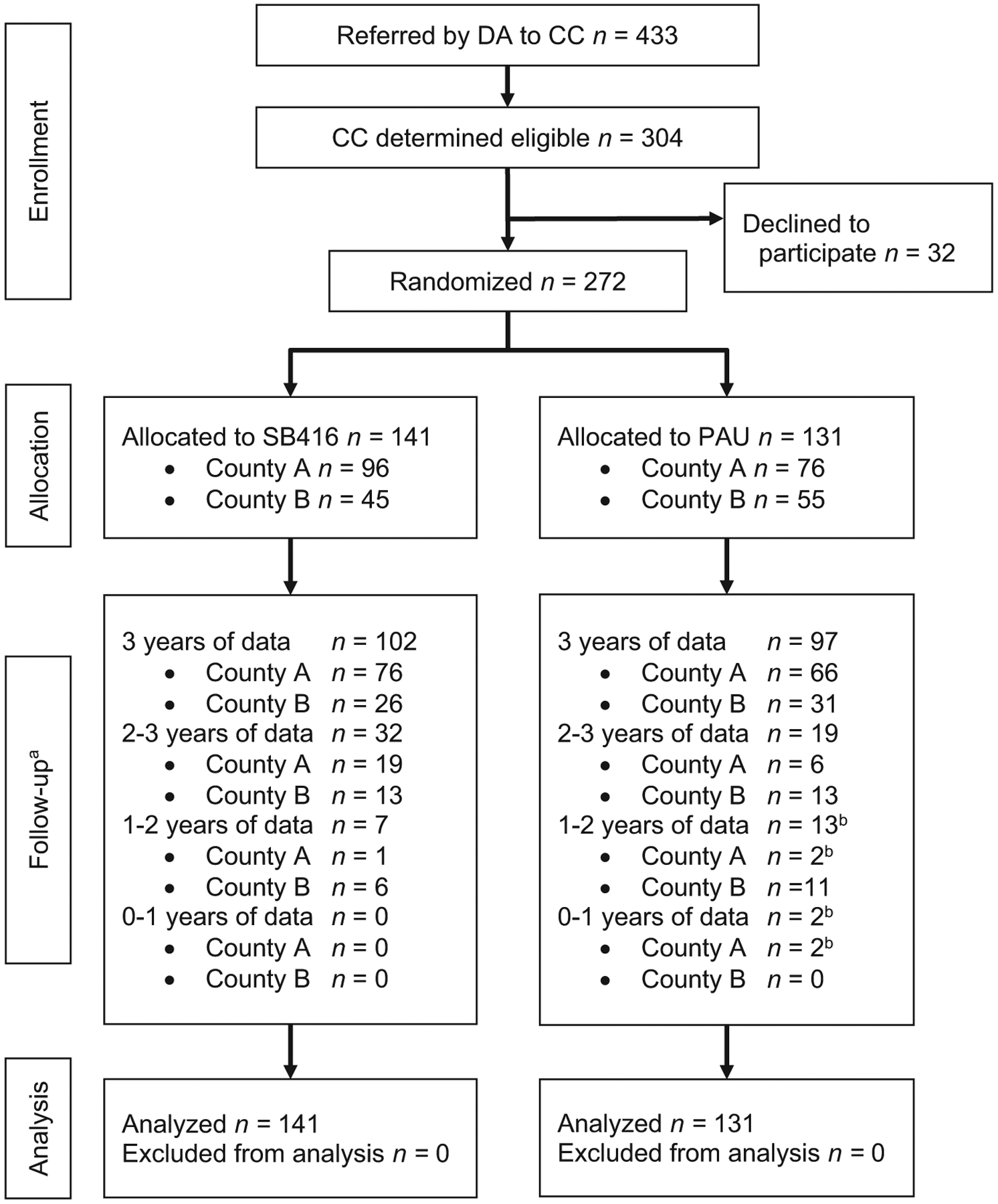

Fig. 2 depicts the flow from participant recruitment through data analysis. Of 433 individuals referred by the DA, 129 were found not eligible by CC’s assessment (see above description of SB416 process). Of the 304 eligible, 32 declined and 272 were enrolled (89.5% recruitment rate). All 272 participants were included in the data analysis.

Fig. 2.

CONSORT Participant Flow Diagram.

Note. SB416= Oregon Senate Bill (SB) 416 Program. PAU = Probation as Usual. DA = District Attorney. CC = Community Corrections.

aFollow-up length for arrest data is reported; due to a slight difference in retrieval date for conviction and incarceration data, the 1–2 year, 2–3 year, and 3 year numbers differ slightly (i.e., by a range of 1–6 participants). bParticipants with less than 3 years follow-up data due to death: 1–2 years, n = 1; 0–1 years, n = 2.

Overall, study participants were 18–58 years of age (M = 32.7, SD = 9.1), and 67.6% were reported to be male. Race/ethnicity was reported as 77.9% White, 14.0% Latinx, 5.5% Black/African American, 1.8% Native American, and 0.7% Asian. County A participants (n = 172) were 18–58 years of age (M = 32.9, SD = 9.3), and 70.3% were reported to be male. Race/ethnicity in County A was reported as 69.8% White, 19.2% Latinx, 7.0% Black/African American, 2.9% Native American, and 1.2% Asian. County B participants (n = 100) were 19–58 years of age (M = 32.3, SD = 8.9), and 63.0% were reported to be male. Race/ethnicity in County B was reported as 92.0% White, 5.0% Latinx, and 3.0% Black/African American.

In Oregon, the Public Safety Checklist (PSC; https://risktool.ocjc.state.or.us/psc/) is used to assess the probability that an offender will be re-convicted of a felony within three years of prison release or the point of diversion from prison. This actuarial risk assessment tool, developed via a collaboration between the Oregon Department of Corrections and the Oregon CJC, uses offender characteristics (e.g., age, sex, severity of current crime, number of prior arrests) to predict recidivism. In a large validation study involving 350,000 offenders in Oregon, the PSC yielded an area under the curve score of 0.70, indicating high predictive validity. PSC scores can range from 0% to 100% and cut-points are specified for individuals at low (0%–24%), medium (25%–37%), and high (38%–100%) recidivism risk. For the 272 individuals participating in this RCT, the overall mean PSC score was 42% (SD = 16), reflecting high risk for recidivism. For County A participants, the mean PSC score was 43% (SD = 15), and for County B participants, the mean PSC score was 41% (SD = 16).

2.2. Randomization procedure

Participants were allocated to SB416 or PAU via urn randomization. The urn was used to achieve balance across the intervention conditions on key factors: 1) sex (male v. female); 2) age (18–26 v. 27+); and 3) LS/CMI score (medium v. high). Following informed consent, CC staff remotely accessed the randomization utility via VPN, entered the participant’s status on each factor, and ran the program to determine condition assignment. Participants were informed of condition at that time and subsequently assigned to a PO in the corresponding condition. Access of the randomization utility, randomization results, and CC records were audited by the authors regularly to ensure adherence to procedures. As shown in Table 2, the urn successfully yielded non-significant differences in the randomization factors by condition.

Table 2.

Distribution of randomization factors by condition.

| PAU | SB416 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| County A | |||

| Sex: Male | 71% | 70% | 0.857 |

| Age: 27+ | 70% | 68% | 0.775 |

| LS/CMI: High Risk | 86% | 81% | 0.451 |

| County B | |||

| Sex: Male | 60% | 67% | 0.489 |

| Age: 27+ | 66% | 69% | 0.715 |

| LS/CMI: High Risk | 96% | 96% | 0.839 |

| Overall | |||

| Sex: Male | 66% | 69% | 0.672 |

| Age: 27+ | 68% | 68% | 0.910 |

| LS/CMI: High Risk | 90% | 86% | 0.640 |

Note. Randomization factors were either dichotomous or dichotomized prior to randomization, including sex (male v. female), age (18–26 v. 27+ years), and Level of Service/Case Management Inventory (LS/CMI) score (medium v. high risk). Significance tests compared PAU and SB416 within County A, within County B, and then across both counties via estimated marginal means. Logistic regression models for each randomization factor included main effects for County, Condition, and the interaction between County and Condition.

2.3. Intervention conditions

The SB416 program was described previously, and a manual is available from the authors. The control condition was PAU for medium/high risk offenders. That is, the control condition was typical probation services that would be delivered to individuals deemed by CC to be at medium or high risk for recidivism. As with SB416, this risk level requires a minimum of 7 in-person contacts/6 months for medium-risk offenders and 15 in-person contacts/6 months for high-risk offenders and periodic home visits. The SB416 PO did not supervise PAU participants, and vice versa. In both counties, PAU participants had access to the same treatment services as SB416 participants, but the PAU participants’ POs provided less coordination for attendance and treatment participation. Control participants in the two counties also had access to mentoring, but it was not mandatory, and the mentors were not specialized SB416 mentors. For PAU, POs have access to the same sanctions grid (see above), but often have less information to guide decisions than SB416 POs, because they are not in regular communication with mentors and treatment staff.

2.4. Outcomes

Study data were not collected directly from participants. Instead, archival records of recidivism were provided by the Oregon CJC. The recidivism outcome was evaluated independently for arrests, convictions, and incarcerations, and for each of these, there were three versions of the outcome: (1) a dichotomous recidivism status (0 = No Recidivism, 1 = Recidivism), (2) a count of recidivism events, and (3) time to the first occurrence of the event (scaled in months). Of note, the data retrieval date varied slightly across data sources, which meant that the time at risk for recidivism also varied (see Data Analysis Strategy). However, for all outcomes, the maximum time at risk was limited to three years in accordance with the state definition. Described next are the three data sources for the recidivism outcomes.

2.4.1. Arrests

Arrest data were retrieved from the Oregon Law Enforcement Data System (LEDS). The data included the number of days to each arrest following randomization. Also included was the pre-randomization, lifetime count of arrests.

2.4.2. Convictions

Conviction data were retrieved from the Oregon Circuit Court data system. Recidivism was defined as a misdemeanor or felony conviction for a new crime. Pre- and post-randomization convictions were identified using the offense date associated with each conviction.

2.4.3. Incarcerations

Incarceration data were retrieved from the Oregon Department of Corrections. Because SB416 is a prison diversion program, recidivism could include incarceration for a new crime or for a revocation. Pre- and post-randomization incarcerations were identified based on the prison admission date. Only two participants had more than one prison admission during follow-up, and because of this, the count outcome for incarceration reflects the number of convictions associated with the incarceration. Additionally, the incarceration data included the crime date(s) and conviction date(s) associated with each prison admission. From this, two versions of incarceration outcomes were created, one for all prison admissions post-randomization (regardless of crime date), and the other limited to prison admissions for crime dates that were post-randomization (i.e., for new crimes committed post-randomization). This was important because a subset of participants recruited into the study were subsequently incarcerated for crimes that had been committed prior to study entry and randomization; typically, these were historical crimes that had been committed outside of Counties A and B. To illustrate this, the rate of incarceration recidivism was 57% when based on all prison admissions, but when limited only to new crimes that followed randomization, the rate of recidivism decreased to 32%.

2.5. Data analysis strategy

2.5.1. Primary analyses

2.5.1.1. Data structure and model formulation.

The data were structured with 272 participants nested in one of two counties (County A, County B). All participants were randomized to PAU or SB416. Intention-to-treat analyses were performed, with each participant retained in the randomly allocated condition regardless of participation in the condition. Related to this, with the outcome data retrieved from archival sources, there was no loss to follow-up (see Fig. 2). For the primary analyses, each outcome had two versions: dichotomous (i.e., Did it occur?) and count (i.e., How many times did it occur?). Dichotomous outcomes were analyzed according to a binary logistic distribution (logit link), and the estimated effects included odds ratios (ORs; i.e., exp[β]) and predicted probabilities (i.e., OR/[1 + OR]). Count outcomes were analyzed according to a negative binomial distribution (log link), and the estimated effects included event rate ratios (ERs; i.e., exp[β]). The analyses were implemented as generalized linear models using SPSS software (IBM Corp., 2017).

For each outcome, two models were performed to test for: (1) an overall effect of SB416 across the two counties and (2) an effect of SB416 within each county. The first model included a dummy-coded indicator for intervention condition (0 = PAU, 1 = SB416). The second included the condition indicator, county indicator (0 = County A, 1 = County B), and the interaction of condition and county. In this model, the effect of SB416 in County A was estimated by the condition term (main effect), and the effect for County B was obtained as a pairwise comparison of estimated marginal means (EMMs). Finally, it is important to note that this model formulation provides a direct comparison of the two counties; however, this was not of primary interest and the corresponding results (i.e., interaction term) should not be interpreted without considerable supporting context.

2.5.1.2. Adjusting for each participant’s time at risk for recidivism.

Participants varied in their time at risk—or their “opportunity”—for recidivism, and this was important to consider in the statistical analyses. This variability came from two sources. First, because participants were recruited on a rolling basis, those recruited later in the RCT had a follow-up that was shorter than the intended three-year recidivism period (see Fig. 2). Specifically, across outcomes, 69% to 73% of the sample had the full three-year follow-up (which varied due to different data retrieval dates), and of those with less than three years of data, the median follow-up was 2.3 years (SD = 0.6). Second, participants who were incarcerated at some point during follow-up had reduced opportunity for further recidivism. For instance, after removing time incarcerated, the median duration of the follow-up period decreased from 3.0 years (SD = 0.5) to 2.0 years (SD = 0.9). Because of this variability, it was important to adjust the statistical models for each participant’s total time at risk for recidivism—this provides a more accurate overall estimate of recidivism. Two versions of the exposure adjustment (i.e., “offset”) were computed. The first version was the number of years (natural log transformed) between each participant’s randomization date and the data retrieval date for each outcome (with a maximum of three years). The second version started with the participant’s length of follow-up but also removed the duration of incarceration for participants who were incarcerated. For each outcome, a separate model was performed with the two exposure variables. The exposure terms have two effects on interpretation. First, they align participants with respect to their risk of recidivism (e.g., a participant arrested two times in one year of follow-up would not be assumed to be the same as a participant arrested two times in three years of follow-up). Second, the exposure terms rescale model estimates so that, instead of reflecting the entire three-year recidivism period, the estimates reflect a yearly log-odds (dichotomous) or log rate (count) of recidivism. This is a commonly used, and highly flexible, method for accommodating variability in time at risk.

2.5.2. Secondary analyses

Secondary analyses evaluated the effect of SB416 on time to recidivism, specifically, time to the first occurrence of an arrest, conviction, incarceration, or incarceration for a new crime committed post-randomization. The analyses were implemented as Cox regression models in SPSS. For each type of recidivism, the time variable was defined as the number of months from randomization to the first recidivism event or, for participants without recidivism, the number of months in the follow-up period. The event variable was a dummy-coded indicator for each participant’s recidivism status (0 = No, 1 = Yes). The initial model included the dummy-coded condition indicator (0 = PAU, 1 = SB416), and the next model added a dummy-coded indicator for county (0 = County A, 1 = County B), as well as the interaction between county and condition. As with the primary analyses, the interaction term was not the main focus and should not be interpreted without additional context. Instead, the main focus was the effect of SB416 relative to PAU within each of the two counties. To obtain the statistical significance test for the effect of SB416 in County B (i.e., the non-reference county), the model was re-estimated with the reference group reverse coded (i.e., 0 = County B, 1 = County A). The effect of SB416 was estimated by the log hazard rate, and statistical significance was based on the Wald test statistic. The hazard ratio (HR; i.e., exp[β]) was used to characterize the monthly difference in the rate of recidivism for SB416 relative to PAU, with HRs below 1.0 indicating the percentage reduction in recidivism for the SB416 group (i.e., 100 × [HR – 1]).

2.5.3. Summary of the data analysis strategy

The analyses focus on three types of recidivism outcomes—arrests, convictions, and incarcerations—and for each, SB416 and PAU are compared in three ways: The first model tests for a difference in the likelihood of recidivism occurring (i.e., a dichotomous outcome, analyzed using binary logistic regression). The second model tests for a difference in the number of times the recidivism outcome occurred (i.e., a count outcome, analyzed using negative binomial regression). The third model tests for a difference in the time to recidivism (i.e., a time-to-event outcome, analyzed using Cox regression models). For the first two models, it was important to adjust for participants having different lengths of time at risk for recidivism, and to do that, two adjustments were applied. One considered the actual amount of time between each participant’s randomization date and the date of data retrieval (with a maximum of 3 years), and the other also adjusted for the amount of time the participant was incarcerated during follow-up. For the incarceration outcome, there was one additional consideration. One version of the outcome included all prison admissions that followed randomization, regardless of the associated crime date and conviction date. The other version only included prison admissions for crime dates that followed randomization. Across the arrest, conviction, and incarceration outcomes, the analyses focused on comparing SB416 and PAU within each of the two counties, and direct comparison of the two counties is not appropriate with the current data.

3. Results

Table 3 reports the descriptive statistics for recidivism outcomes by county.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics for recidivism outcomes by county and condition.

| Outcome by County | Any Recidivism | Count of Recidivism Events | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAU | SB416 | PAU | SB416 | |||||||||

| % | % | M | Mdn | SD | Min | Max | M | Mdn | SD | Min | Max | |

| Arrest | ||||||||||||

| County A | 71 | 73 | 1.68 | 1.00 | 1.66 | 0 | 6 | 1.80 | 1.50 | 1.65 | 0 | 7 |

| County B | 55 | 42 | 0.89 | 1.00 | 1.07 | 0 | 5 | 0.69 | 0.00 | 1.06 | 0 | 5 |

| Conviction | ||||||||||||

| County A | 68 | 65 | 1.66 | 1.00 | 1.66 | 0 | 7 | 1.99 | 1.00 | 2.35 | 0 | 10 |

| County B | 45 | 33 | 1.25 | 0.00 | 1.96 | 0 | 8 | 0.58 | 0.00 | 1.01 | 0 | 4 |

| Incarceration (All) | ||||||||||||

| County A | 50 | 51 | 1.55 | 0.50 | 2.13 | 0 | 9 | 1.70 | 1.00 | 2.69 | 0 | 19 |

| County B | 71 | 64 | 2.73 | 2.00 | 3.37 | 0 | 19 | 1.89 | 1.00 | 2.89 | 0 | 13 |

| Incarceration (New Crime) | ||||||||||||

| County A | 34 | 35 | 0.49 | 0.00 | 0.77 | 0 | 3 | 0.68 | 1.00 | 1.16 | 0 | 6 |

| County B | 35 | 16 | 0.75 | 0.00 | 1.48 | 0 | 7 | 0.27 | 0.00 | 0.75 | 0 | 4 |

Note. SB416= Oregon Senate Bill (SB) 416 Program. PAU = Probation as Usual. The Incarceration (All) outcome is based on all incarceration dates that followed randomization, regardless of the associated crime date (i.e., crimes could have been committed prior to randomization). The Incarceration (New Crime) outcome is based on incarcerations for crime dates that followed randomization.

3.1. Likelihood and count of recidivism

The primary analyses address the effect of SB416 on the likelihood of recidivism and the number of times it occurred. This answers the questions: Was SB416 associated with a lower likelihood of arrest, conviction, or incarceration within 3 years of randomization? Was SB416 associated with fewer arrests, convictions, or incarcerations (i.e., convictions leading to an incarceration) within 3 years of randomization? To address these questions, the analyses considered participants’ time at risk for recidivism in two ways. In the first, the model adjusted for the length of each participant’s follow-up period, and in the second, it also adjusted for the amount of time each participant was incarcerated.

3.1.1. Arrest recidivism

3.1.1.1. Adjusted for length of follow-up.

Results are reported in the top section of Table 4. Overall (i.e., when not considering the effect of county), SB416 and PAU did not differ significantly on the likelihood of arrest or count of arrests during the follow-up period. Similarly, within County A and within County B, SB416 and PAU did not differ significantly.

Table 4.

Regression Estimates for the Effect of SB416 on Arrest Recidivism.

| Any Arresta | Count of Arrestsb | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est. | SE | p | OR | 95% CIOR | Est. | SE | p | ER | 95% CIER | |

| Adjusted for Length of Follow-Upc | ||||||||||

| Overall Effect | ||||||||||

| Intercept | −0.382 | 0.185 | 0.039 | 0.68 | [0.48, 0.98] | −0.707 | 0.116 | <0.001 | 0.49 | [0.39, 0.62] |

| SB416 | −0.109 | 0.255 | 0.668 | 0.90 | [0.54, 1.48] | 0.025 | 0.160 | 0.875 | 1.03 | [0.75, 1.40] |

| Effect by County | ||||||||||

| Intercept | −0.087 | 0.260 | 0.737 | 0.92 | [0.55, 1.52] | −0.534 | 0.146 | <0.001 | 0.59 | [0.44, 0.78] |

| SB416 | 0.020 | 0.347 | 0.955 | 1.02 | [0.52, 2.01] | 0.057 | 0.194 | 0.768 | 1.06 | [0.72, 1.55] |

| County B | −0.648 | 0.377 | 0.085 | 0.52 | [0.25, 1.09] | −0.497 | 0.246 | 0.043 | 0.61 | [0.38, 0.98] |

| SB416 × County B | −0.570 | 0.536 | 0.287 | 0.57 | [0.20, 1.62] | −0.401 | 0.363 | 0.269 | 0.67 | [0.33, 1.36] |

| EMM: County Bd | ||||||||||

| SB416 vs. PAU | −0.107 | 0.079 | 0.173 | 0.58 | e | −0.104 | 0.092 | 0.260 | 0.71 | e |

| Adjusted for Length of Follow-Up and Time Incarceratedf | ||||||||||

| Overall Effect | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 0.249 | 0.195 | 0.200 | 1.28 | [0.88, 1.88] | −0.103 | 0.121 | 0.393 | 0.90 | [0.71, 1.14] |

| SB416 | −0.279 | 0.266 | 0.294 | 0.76 | [0.45, 1.27] | −0.081 | 0.166 | 0.627 | 0.92 | [0.67, 1.28] |

| Effect by County | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 0.379 | 0.268 | 0.157 | 1.46 | [0.86, 2.47] | −0.034 | 0.151 | 0.822 | 0.97 | [0.72, 1.30] |

| SB416 | −0.037 | 0.357 | 0.918 | 0.96 | [0.48, 1.94] | 0.011 | 0.200 | 0.956 | 1.01 | [0.68, 1.50] |

| County B | −0.284 | 0.394 | 0.470 | 0.75 | [0.35, 1.63] | −0.201 | 0.256 | 0.433 | 0.82 | [0.50, 1.35] |

| SB416 × County B | −0.794 | 0.556 | 0.154 | 0.45 | [0.15, 1.35] | −0.515 | 0.376 | 0.170 | 0.60 | [0.29, 1.25] |

| EMM: County Bd | ||||||||||

| SB416 vs. PAU | −0.200 | 0.100 | 0.045 | 0.44 | e | −0.313 | 0.200 | 0.117 | 0.60 | e |

Note. SB416 = Oregon Senate Bill (SB) 416 Program. PAU = Probation as Usual. For Overall Effect, SB416 is the estimated intervention effect across both counties. For Effect by County, SB416 is the estimated effect within County A. Within County B, the effect of SB416 is provided by the Estimated Marginal Mean (EMM).

Binary logistic regression model (logit link).

Negative binomial regression model (log link).

Natural log transformed exposure term for length of follow-up.

EMM = Estimated Marginal Mean; the difference in probability/count between SB416 and PAU in County B.

95% CIs for OR/ER could not be computed; the formulation did not estimate the SE for the between-group difference in log odds/log event rate.

Natural log transformed exposure term that removes time incarcerated from length of follow-up.

3.1.1.2. Adjusted for length of follow-up and time incarcerated.

Results are reported in the bottom section of Table 4. Overall, SB416 and PAU did not differ significantly on the likelihood or count of arrests during follow-up. The same was true within County A. For County B, SB416 had a significantly lower likelihood of arrest recidivism, with a yearly probability of 32%, versus 52% for PAU (OR = 0.44). However, the two groups did not differ on the count of arrests.

3.1.1.3. Arrest summary.

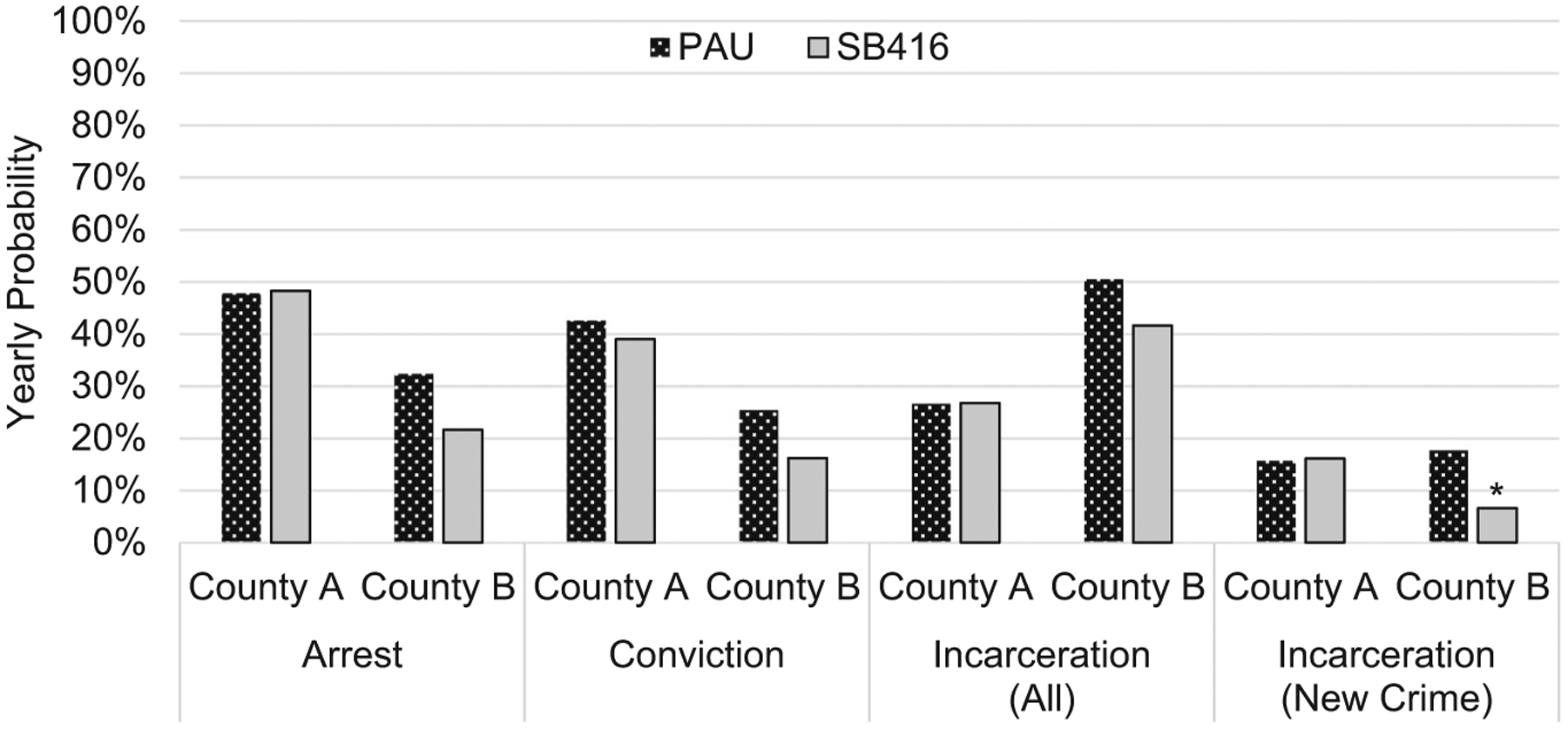

When only adjusting for each participant’s length of follow-up, SB416 did not have a significant effect on arrest recidivism, and with one exception, the same was true when also adjusting for time incarcerated. The exception was for County B, and when adjusting for time incarcerated, SB416 had a significantly lower likelihood of arrest recidivism compared to PAU. The outcomes for SB416 and PAU within each county are illustrated in Figs. 3–6.

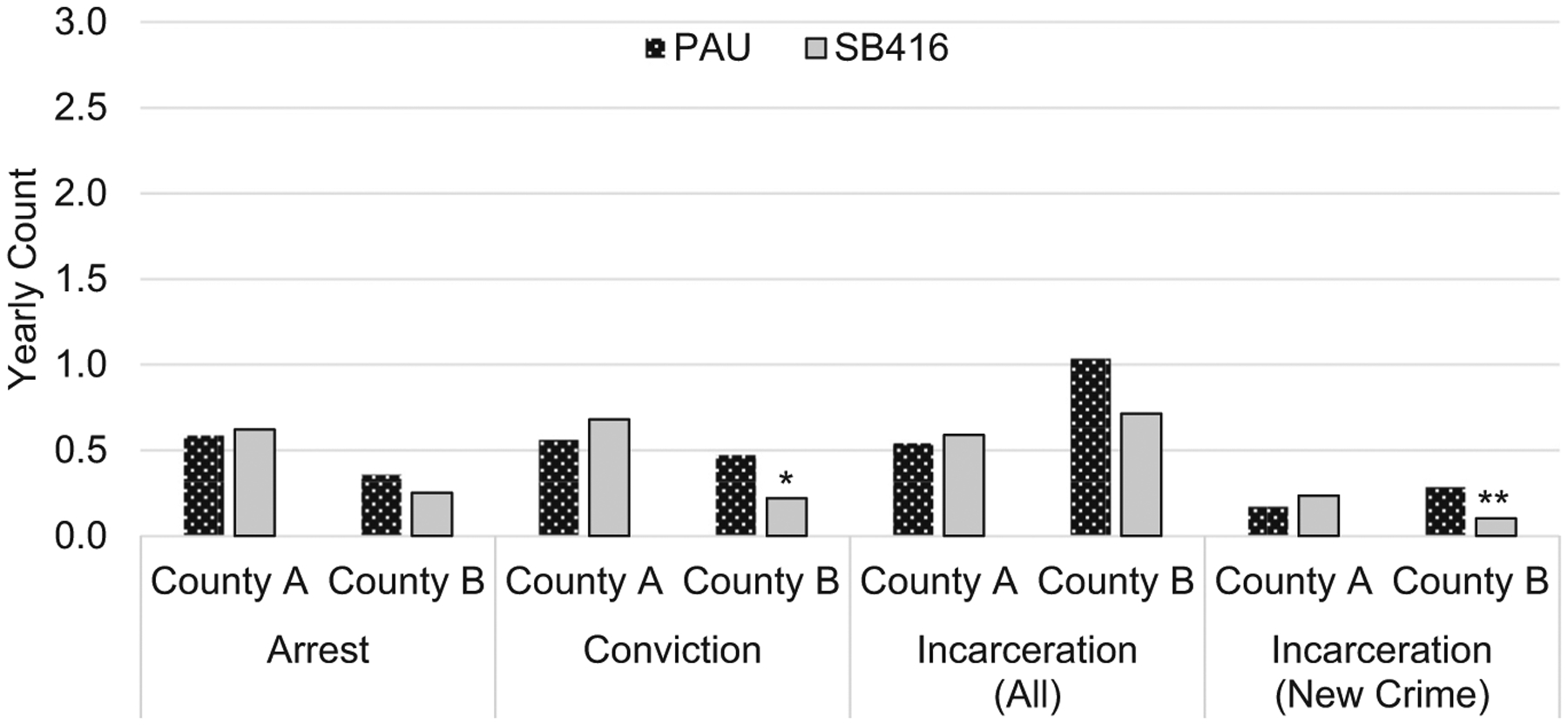

Fig. 3.

Yearly Probability of Recidivism by County and Condition (Adjusted for Length of Follow-up).

Note. SB416 = Oregon Senate Bill (SB) 416 Program. PAU = Probation as Usual. The figure displays predicted yearly probabilities of recidivism by county and intervention condition. The estimates are based on a binary logistic regression model (logit link) with a natural log transformed exposure term to adjust for each participant’s length of follow-up. The Incarceration (All) outcome is based on all incarceration dates that followed randomization, regardless of the associated crime date. The Incarceration (New Crime) outcome is based on incarcerations for crime dates that followed randomization.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

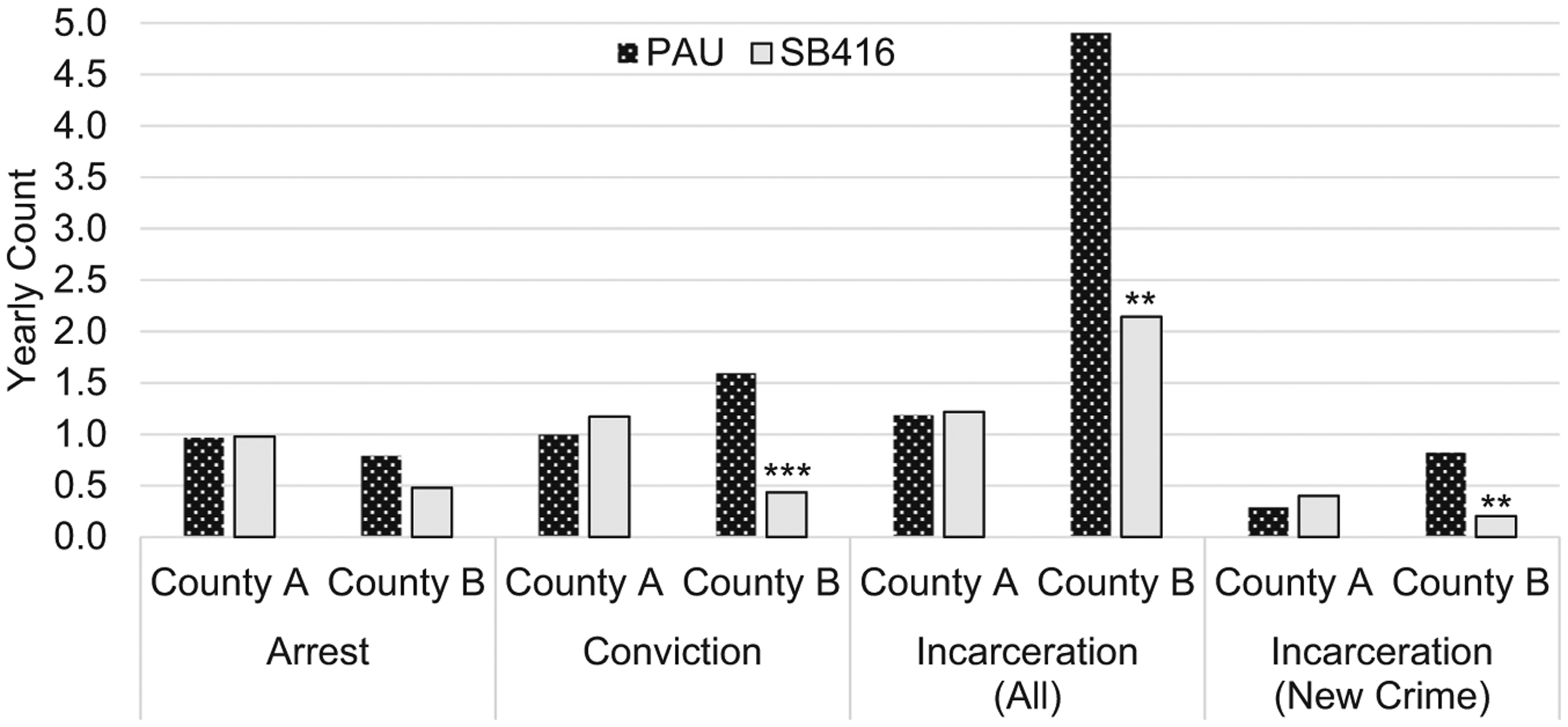

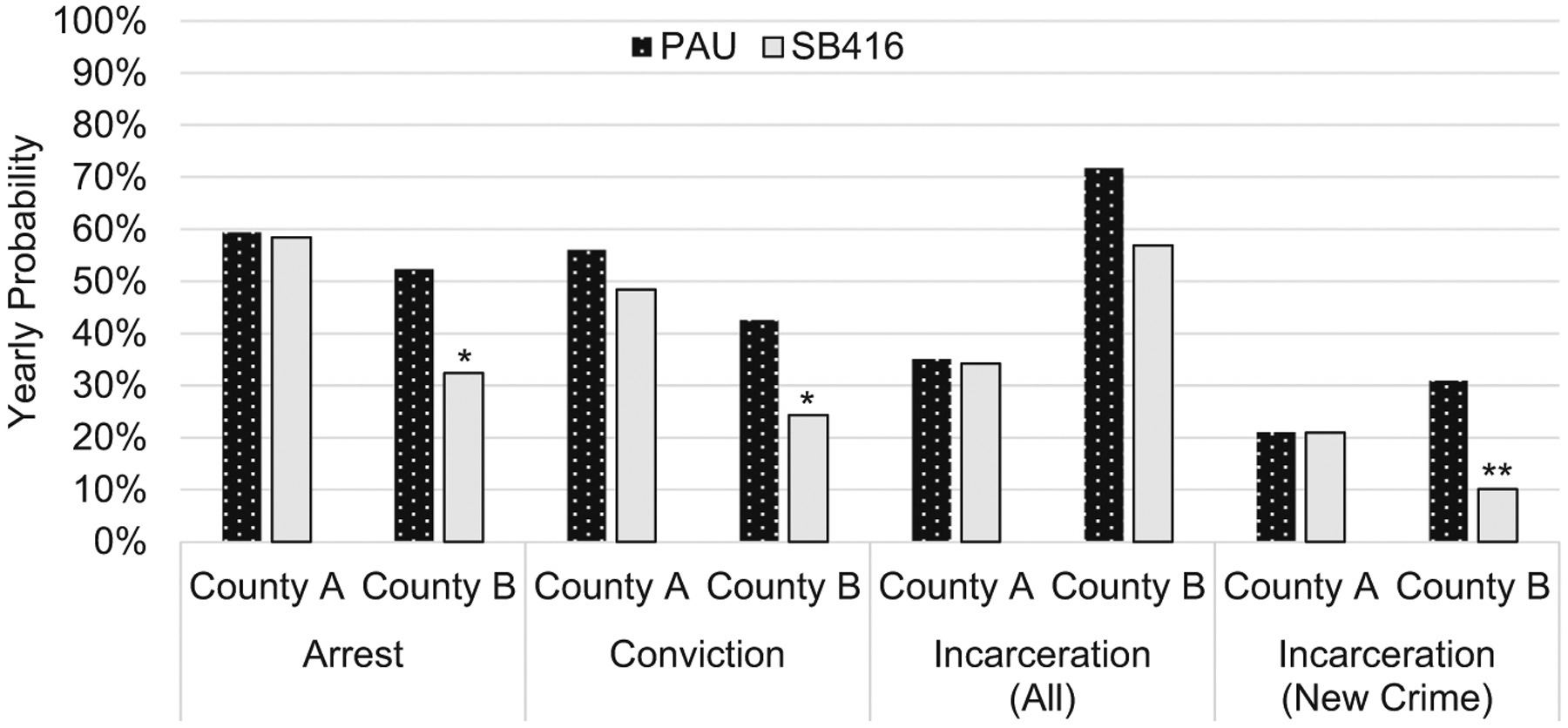

Fig. 6.

Yearly Count of Recidivism Events by County and Condition (Adjusted for Length of Follow-Up and Time Incarcerated).

Note. SB416 = Oregon Senate Bill (SB) 416 Program. PAU = Probation as Usual. The figure displays predicted yearly count of recidivism by county and intervention condition. The estimates are based on a negative binomial regression model (log link) with a natural log transformed exposure term to adjust for each participant’s length of follow-up and time incarcerated. The incarceration outcomes reflect the count of convictions associated with the incarceration. The Incarceration (All) outcome is based on all incarceration dates that followed randomization, regardless of the associated crime date. The Incarceration (New Crime) outcome is based on incarcerations for crime dates that followed randomization.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

3.1.2. Conviction recidivism

3.1.2.1. Adjusted for length of follow-up.

Results are reported in the top section of Table 5. Overall, SB416 and PAU did not differ significantly on the likelihood or count of convictions during the follow-up period, and the same was true within County A. Within County B, the groups did not differ on the likelihood of recidivism, but SB416 had a significantly lower count of convictions, with a predicted yearly count of 0.22, versus 0.47 for PAU (ER = 0.47).

Table 5.

Regression Estimates for the Effect of SB416 on Conviction Recidivism

| Any Convictiona | Count of Convictionsb | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est. | SE | p | OR | 95% CIOR | Est. | SE | p | ER | 95% CIER | |

| Adjusted for Length of Follow-Upc | ||||||||||

| Overall Effect | ||||||||||

| Intercept | −0.638 | 0.179 | <0.001 | 0.53 | [0.37, 0.75] | −0.644 | 0.113 | <0.001 | 0.53 | [0.42, 0.66] |

| SB416 | −0.191 | 0.246 | 0.439 | 0.83 | [0.51, 1.34] | 0.025 | 0.157 | 0.871 | 1.03 | [0.75, 1.39] |

| Effect by County | ||||||||||

| Intercept | −0.298 | 0.247 | 0.227 | 0.74 | [0.46, 1.20] | −0.578 | 0.145 | <0.001 | 0.56 | [0.42, 0.75] |

| SB416 | −0.148 | 0.327 | 0.651 | 0.86 | [0.45, 1.64] | 0.193 | 0.192 | 0.315 | 1.21 | [0.83, 1.77] |

| County B | −0.779 | 0.368 | 0.035 | 0.46 | [0.22, 0.94] | −0.172 | 0.233 | 0.460 | 0.84 | [0.53, 1.33] |

| SB416 × County B | −0.421 | 0.532 | 0.428 | 0.66 | [0.23, 1.86] | −0.957 | 0.362 | 0.008 | 0.38 | [0.19, 0.78] |

| EMM: County Bd | ||||||||||

| SB416 vs. PAU | −0.092 | 0.067 | 0.170 | 0.57 | e | −0.250 | 0.102 | 0.013 | 0.47 | e |

| Adjusted for Length of Follow-Up and Time Incarceratedf | ||||||||||

| Overall Effect | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 0.003 | 0.190 | 0.985 | 1.00 | [0.69, 1.45] | 0.176 | 0.122 | 0.151 | 1.19 | [0.94, 1.51] |

| SB416 | −0.404 | 0.258 | 0.117 | 0.67 | [0.40, 1.11] | −0.216 | 0.166 | 0.193 | 0.81 | [0.58, 1.12] |

| Effect by County | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 0.243 | 0.261 | 0.353 | 1.27 | [0.76, 2.13] | −0.002 | 0.152 | 0.988 | 1.00 | [0.74, 1.34] |

| SB416 | −0.306 | 0.341 | 0.371 | 0.74 | [0.38, 1.44] | 0.159 | 0.199 | 0.424 | 1.17 | [0.79, 1.73] |

| County B | −0.539 | 0.388 | 0.165 | 0.58 | [0.27, 1.25] | 0.470 | 0.250 | 0.060 | 1.60 | [0.98, 2.61] |

| SB416 × County B | −0.533 | 0.553 | 0.335 | 0.59 | [0.20, 1.74] | −1.461 | 0.382 | <0.001 | 0.23 | [0.11, 0.49] |

| EMM: County Bd | ||||||||||

| SB416 vs. PAU | −0.180 | 0.093 | 0.048 | 0.43 | e | −1.160 | 0.336 | <0.001 | 0.27 | e |

Note. SB416= Oregon Senate Bill (SB) 416 Program. PAU = Probation as Usual. For Overall Effect, SB416 is the estimated intervention effect across both counties. For Effect by County, SB416 is the estimated effect within County A. Within County B, the effect of SB416 is provided by the Estimated Marginal Mean (EMM).

Binary logistic regression model (logit link).

Negative binomial regression model (log link).

Natural log transformed exposure term for length of follow-up.

EMM = Estimated Marginal Mean; the difference in probability/count between SB416 and PAU in County B.

95% CIs for OR/ER could not be computed; the formulation did not estimate the SE for the between-group difference in log odds/log event rate.

Natural log transformed exposure term that removes time incarcerated from length of follow-up.

3.1.2.2. Adjusted for length of follow-up and time incarcerated.

Results are reported in the bottom section of Table 5. Overall, SB416 and PAU did not differ significantly on the likelihood or count of convictions during the follow-up period, which was also true within County A. However, within County B, SB416 and PAU differed significantly on both outcomes. For SB416, the predicted yearly probability was 24%, versus 43% for PAU (OR = 0.43), and SB416 had a predicted yearly count of 0.43 convictions, versus 1.59 for PAU (ER = 0.27).

3.1.2.3. Conviction summary.

In County A, SB416 and PAU did not differ significantly on conviction recidivism. However, in County B, SB416 had a significantly lower count of convictions, which held for both types of adjustments. Further, when adjusting for length of follow-up and time incarcerated, SB416 had a significantly lower likelihood of conviction recidivism (see Figs. 3–6).

3.1.3. Incarceration recidivism

There were two versions of each incarceration outcome, one that was based on all prison admissions post-randomization and one that focused on prison admissions for new crimes committed post-randomization. For each of these, separate models adjusted for length of follow-up and for time incarcerated.

3.1.3.1. Adjusted for length of follow-up

3.1.3.1.1. All Prison admissions post-randomization.

Results are reported in the top section of Table 6. Overall, SB416 and PAU did not differ significantly on the likelihood of incarceration or the count of convictions leading to an incarceration. Similarly, within each county, SB416 and PAU did not differ significantly.

Table 6.

Regression Estimates for the Effect of SB416 on Incarceration Recidivism (All Incarcerations Following Randomization).

| Any Incarcerationa | Count of Convictions per Incarcerationb | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est. | SE | p | OR | 95% CIOR | Est. | SE | p | ER | 95% CIER | |

| Adjusted for Length of Follow-Upc | ||||||||||

| Overall Effect | ||||||||||

| Intercept | −0.596 | 0.180 | <0.001 | 0.55 | [0.39, 0.78] | −0.294 | 0.107 | 0.006 | 0.75 | [0.60, 0.92] |

| SB416 | −0.203 | 0.248 | 0.413 | 0.82 | [0.50, 1.33] | −0.171 | 0.151 | 0.256 | 0.84 | [0.63, 1.13] |

| Effect by County | ||||||||||

| Intercept | −1.014 | 0.232 | <0.001 | 0.36 | [0.23, 0.57] | −0.613 | 0.148 | <0.001 | 0.54 | [0.41, 0.72] |

| SB416 | 0.008 | 0.310 | 0.980 | 1.01 | [0.55, 1.85] | 0.084 | 0.196 | 0.667 | 1.09 | [0.74, 1.60] |

| County B | 1.035 | 0.379 | 0.006 | 2.82 | [1.34, 5.92] | 0.647 | 0.217 | 0.003 | 1.91 | [1.25, 2.92] |

| SB416 × County B | −0.366 | 0.533 | 0.492 | 0.69 | [0.24, 1.97] | −0.454 | 0.313 | 0.147 | 0.63 | [0.34, 1.17] |

| EMM: County Bd | ||||||||||

| SB416 vs. PAU | −0.089 | 0.107 | 0.406 | 0.70 | e | −0.320 | 0.211 | 0.129 | 0.69 | e |

| Adjusted for Length of Follow-Up and Time Incarceratedf | ||||||||||

| Overall Effect | ||||||||||

| Intercept | 0.005 | 0.190 | 0.980 | 1.00 | [0.69, 1.46] | 0.885 | 0.116 | <0.001 | 2.42 | [1.93, 3.04] |

| SB416 | −0.374 | 0.258 | 0.148 | 0.69 | [0.41, 1.14] | −0.505 | 0.161 | 0.002 | 0.60 | [0.44, 0.83] |

| Effect by County | ||||||||||

| Intercept | −0.615 | 0.240 | 0.010 | 0.54 | [0.34, 0.87] | 0.170 | 0.155 | 0.273 | 1.19 | [0.87, 1.61] |

| SB416 | −0.038 | 0.319 | 0.904 | 0.96 | [0.52, 1.80] | 0.027 | 0.205 | 0.897 | 1.03 | [0.69, 1.53] |

| County B | 1.546 | 0.398 | <0.001 | 4.69 | [2.15, 10.24] | 1.420 | 0.230 | <0.001 | 4.14 | [2.64, 6.50] |

| SB416 × County B | −0.615 | 0.557 | 0.270 | 0.54 | [0.18, 1.61] | −0.855 | 0.332 | 0.010 | 0.43 | [0.22, 0.82] |

| EMM: County Bd | ||||||||||

| SB416 vs. PAU | −0.148 | 0.103 | 0.151 | 0.52 | e | −2.760 | 0.936 | 0.003 | 0.44 | e |

Note. SB416 = Oregon Senate Bill (SB) 416 Program. PAU = Probation as Usual. For Overall Effect, SB416 is the estimated intervention effect across both counties. For Effect by County, SB416 is the estimated effect within County A. Within County B, the effect of SB416 is provided by the Estimated Marginal Mean (EMM).

Binary logistic regression model (logit link).

Negative binomial regression model (log link).

Natural log transformed exposure term for length of follow-up.

EMM = Estimated Marginal Mean; the difference in probability/count between SB416 and PAU in County B.

95% CIs for OR/ER could not be computed; the formulation did not estimate the SE for the between-group difference in log odds/log event rate.

Natural log transformed exposure term that removes time incarcerated from length of follow-up.

3.1.3.1.2. Prison admissions for new crimes post-randomization.

Results are reported in the top section of Table 7. Overall, SB416 and PAU did not differ significantly on incarceration outcomes, and the same was true within County A. Within County B, SB416 had a significantly lower likelihood of incarceration and count of convictions leading to an incarceration. Specifically, for SB416, the predicted yearly probability of incarceration was 7%, versus 18% for PAU (OR = 0.33), and the yearly count of convictions leading to an incarceration was 0.10, versus 0.28 for PAU (ER = 0.36).

Table 7.

Regression Estimates for the Effect of SB416 on Incarceration Recidivism (Incarcerations for Crimes Following Randomization)

| Any Incarcerationa | Count of Convictions per Incarcerationb | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est. | SE | p | OR | 95% CIOR | Est. | SE | p | ER | 95% CIER | |

| Adjusted for Length of Follow-Upc | ||||||||||

| Overall Effect | ||||||||||

| Intercept | −1.622 | 0.186 | <0.001 | 0.20 | [0.14, 0.28] | −1.530 | 0.144 | <0.001 | 0.22 | [0.16, 0.29] |

| SB416 | −0.289 | 0.263 | 0.271 | 0.75 | [0.45, 1.25] | −0.104 | 0.202 | 0.608 | 0.90 | [0.61, 1.34] |

| Effect by County | ||||||||||

| Intercept | −1.681 | 0.244 | <0.001 | 0.19 | [0.12, 0.30] | −1.770 | 0.201 | <0.001 | 0.17 | [0.11, 0.25] |

| SB416 | 0.031 | 0.324 | 0.925 | 1.03 | [0.55, 1.95] | 0.320 | 0.258 | 0.214 | 1.38 | [0.83, 2.28] |

| County B | 0.142 | 0.376 | 0.705 | 1.15 | [0.55, 2.41] | 0.510 | 0.289 | 0.078 | 1.67 | [0.94, 2.94] |

| SB416 × County B | −1.142 | 0.597 | 0.056 | 0.32 | [0.10, 1.03] | −1.330 | 0.465 | 0.004 | 0.26 | [0.11, 0.66] |

| EMM: County Bd | ||||||||||

| SB416 vs. PAU | −0.110 | 0.049 | 0.023 | 0.33 | e | −0.180 | 0.068 | 0.008 | 0.36 | e |

| Adjusted for Length of Follow-Up and Time Incarceratedf | ||||||||||

| Overall Effect | ||||||||||

| Intercept | −1.115 | 0.192 | <0.001 | 0.33 | [0.22, 0.48] | −0.780 | 0.152 | <0.001 | 0.46 | [0.34, 0.62] |

| SB416 | −0.428 | 0.270 | 0.113 | 0.65 | [0.38, 1.11] | −0.286 | 0.211 | 0.176 | 0.75 | [0.50, 1.14] |

| Effect by County | ||||||||||

| Intercept | −1.321 | 0.250 | <0.001 | 0.27 | [0.16, 0.44] | −1.242 | 0.208 | <0.001 | 0.29 | [0.19, 0.43] |

| SB416 | −0.005 | 0.331 | 0.987 | 0.99 | [0.52, 1.90] | 0.321 | 0.266 | 0.227 | 1.38 | [0.82, 2.32] |

| County B | 0.518 | 0.388 | 0.183 | 1.68 | [0.78, 3.59] | 1.047 | 0.305 | <0.001 | 2.85 | [1.57, 5.18] |

| SB416 × County B | −1.379 | 0.611 | 0.024 | 0.25 | [0.08, 0.84] | −1.727 | 0.485 | <0.001 | 0.18 | [0.07, 0.46] |

| EMM: County Bd | ||||||||||

| SB416 vs. PAU | −0.210 | 0.074 | 0.005 | 0.25 | e | −0.620 | 0.196 | 0.002 | 0.25 | e |

Note. SB416 = Oregon Senate Bill (SB) 416 Program. PAU = Probation as Usual. For Overall Effect, SB416 is the estimated intervention effect across both counties. For Effect by County, SB416 is the estimated effect within County A. Within County B, the effect of SB416 is provided by the Estimated Marginal Mean (EMM).

Binary logistic regression model (logit link).

Negative binomial regression model (log link).

Natural log transformed exposure term for length of follow-up.

EMM = Estimated Marginal Mean; the difference in probability/count between SB416 and PAU in County B.

95% CIs for OR/ER could not be computed; the formulation did not estimate the SE for the between-group difference in log odds/log event rate.

Natural log transformed exposure term that removes time incarcerated from length of follow-up.

3.1.3.2. Adjusted for length of follow-up and time incarcerated

3.1.3.2.1. All Prison admissions post-randomization.

Results are reported in the bottom section of Table 6. Overall, SB416 and PAU did not differ significantly on the likelihood of incarceration. However, the groups differed significantly on the count of convictions leading to an incarceration, with SB416 having a predicted yearly count of 1.46, and PAU having a count of 2.42 (ER = 0.60). Within County A, the groups did not differ significantly on the likelihood of incarceration or count of convictions leading to an incarceration. Within County B, the groups did not differ significantly on the likelihood of incarceration, but they did differ significantly on the count of convictions leading to an incarceration. The predicted yearly count for SB416 was 2.14, and for PAU, it was 4.9 (ER = 0.44).

3.1.3.2.2. Prison admissions for new crimes post-randomization.

Results are reported in the bottom section of Table 7. Overall, SB416 and PAU did not differ significantly on the likelihood of incarceration or count of convictions leading to an incarceration, and the same was true within County A. Within County B, SB416 had a significantly lower likelihood of incarceration and count of convictions leading to an incarceration. Specifically, for SB416, the predicted yearly probability of incarceration was 10%, versus 31% for PAU (OR = 0.25), and the count of convictions leading to an incarceration was 0.20, versus 0.82 for PAU (ER = 0.25).

3.1.3.3. Incarceration summary.

There was an overall effect of SB416 (i. e., not considering county) when adjusting for time incarcerated, with the count of all convictions leading to an incarceration (regardless of crime date) being significantly lower for SB416 compared to PAU. Within County B, SB416 had a lower likelihood of incarceration and count of convictions leading to an incarceration when based on new crimes following randomization, whether adjusting for the length of follow-up or adjusting for time incarcerated (see Figs. 3–6). When the outcome was based on all incarcerations (i.e., even if the associated crime date preceded randomization), there was one effect in County B, with SB416 having a lower count of convictions leading to an incarceration.

3.2. Time to recidivism

The secondary analyses focus on time to recidivism, answering the question: Was SB416 associated with a decrease in the rate of recidivism for arrests, convictions, or incarcerations?

3.2.1. Arrest recidivism

In the Cox proportional hazards model for time to arrest recidivism, across models, there were no statistically significant differences between SB416 and PAU. Overall, SB416 was associated with a 5% decrease in the rate of arrest recidivism, β = −0.055, SE = 0.152, Wald = 0.133, p = .716, HR = 0.95, 95% CIHR = [0.70, 1.28]. When comparing SB416 and PAU within each county, SB416 in County A was associated with a 1% decrease in the rate of arrest recidivism, β = −0.012, SE = 0.181, Wald = 0.004, p = .948, HR = 0.99, 95% CIHR = [0.69, 1.41]. In County B, SB416 was associated with a 30% decrease in the rate of arrest recidivism, β = −0.356, SE = 0.293, Wald = 1.476, p = .224, HR = 0.70, 95% CIHR = [0.39, 1.24].

3.2.2. Conviction recidivism

There were no statistically significant differences between SB416 and PAU in the time to conviction recidivism. Overall, SB416 was associated with a 9% decrease in the rate of conviction recidivism, β = −0.098, SE = 0.161, Wald = 0.372, p = .542, HR = 0.91, 95% CIHR = [0.66, 1.24]. When comparing the groups within each county, SB416 in County A was associated with a 6% decrease in the rate of conviction recidivism, β = −0.065, SE = 0.188, Wald = 0.118, p = .731, HR = 0.94, 95% CIHR = [0.65, 1.36]. In County B, SB416 was associated with a 34% decrease in the rate of conviction recidivism, β = −0.412, SE = 0.327, Wald = 1.593, p = .207, HR = 0.66, 95% CIHR = [0.35, 1.26].

3.2.3. Incarceration recidivism

3.2.3.1. All Prison admissions post-randomization.

There were no statistically significant differences between SB416 and PAU in the time to any incarceration post-randomization (i.e., for crimes committed either before or after randomization). Overall, SB416 was associated with a 13% decrease in the rate of incarceration recidivism, β = −0.140, SE = 0.161, Wald = 0.757, p = .384, HR = 0.87, 95% CIHR = [0.63, 1.19]. When comparing SB416 and PAU within each county, SB416 in County A was associated with a 1% decrease in the rate of incarceration recidivism, β = −0.006, SE = 0.216, Wald = 0.001, p = .979, HR = 0.99, 95% CIHR = [0.65, 1.52]. In County B, SB416 was associated with a 16% decrease in the rate of incarceration recidivism, β = −0.175, SE = 0.246, Wald = 0.508, p = .476, HR = 0.84, 95% CIHR = [0.52, 1.36].

3.2.3.2. Prison admissions for new crimes post-randomization.

Overall, SB416 and PAU did not differ significantly on the time to incarceration for crime dates following randomization, β = −0.305, SE = 0.216, Wald = 1.992, p = .158, HR = 0.74, 95% CIHR = [0.48, 1.13]. When comparing the two groups within each county, the difference between SB416 and PAU in County A was not statistically significant, with SB416 associated with a 2% decrease in the rate of incarceration recidivism, β = −0.006, SE = 0.261, Wald = 0.001, p = .981, HR = 0.99, 95% CIHR = [0.60, 1.66]. In County B, there was a statistically significant difference between SB416 and PAU. Specifically, SB416 was associated with a 66% decrease in the rate of incarceration recidivism for a crime date following randomization, β = −1.070, SE = 0.443, Wald = 5.844, p = .016, HR = 0.34, 95% CIHR = [0.14, 0.82].

4. Discussion

This paper reports findings from an RCT of a front-end diversion program for prison-bound individuals with prior property crime convictions, concurrent substance use problems, and no prior violent crime convictions. The results from this trial provide partial support for the study hypotheses. There was limited evidence of an overall SB416 intervention effect, and in County A, SB416 did not outperform PAU on any of the recidivism outcomes. However, for County B, multiple intervention effects were observed. That is, for County B and when adjustments were made for participants’ time at risk, SB416 yielded significantly greater improvements across various configurations of the arrest, conviction, and incarceration outcomes, relative to PAU. These findings add to the existing evidence base on the effectiveness of diversion programming compared to more typical justice system processing (Harvey et al., 2007; Hayhurst et al., 2019; Lange et al., 2011).

Potential explanations were considered for the differential impact of SB416 in Counties A and B. Study participants from the two counties were similar with regard to demographic characteristics and PSC scores (i.e., risk for recidivism). Thus, offender-specific variables did not appear to play a role in the differential findings. However, a few countyspecific variables seem relevant. First, although County A had fewer residents than County B when this trial began in 2015 (i.e., 284,834 vs. 322,959, respectively), County A had a much greater resourced CC department. Indeed, in Fiscal Year (FY) 2015–2016, County A had a CC operating budget of $15,103,223 and 79 full-time positions. However, in that same FY, County B had a CC operating budget of $8,888,380 and 50 full-time positions. This difference had implications for PO caseload size in the two counties. With more resources and personnel, CC in County A was able to set a maximum caseload size of 60 probationers for all of its POs, and this applied to POs delivering both SB416 and PAU in the present trial. Indeed, the typical caseload size for POs in County A was 55 to 60 cases. In contrast, CC in County B did not have a caseload maximum. When this RCT began, the CC Director in County B made a special exception to cap the SB416 PO caseload at 60 cases (to match SB416 in County A), but for the POs delivering PAU in County B, typical caseloads ranged between 80 and 100 cases. Exceedingly high caseloads jeopardize a PO’s ability to provide regular support and supervision to probationers and increase the chances of cases “falling through the cracks.” This raises questions about the potential relevance of caseload size for observing an SB416 intervention effect in County B, but not in County A. Perhaps the intervention effect in County B is at least partly driven by the caseload size difference across the SB416 and PAU conditions in that particular county, whereas in County A the caseloads were low and the same for both conditions.

Of note, past research has shown that intensive supervision can actually lead to equivalent or even higher rates of recidivism compared to standard probation. For example, Hyatt and Barnes’ (2017) well-conducted RCT found intensive supervision probation did not prevent arrests or charges, and actually produced more technical violations and incarcerations compared to standard probation. This is consistent with prior research (e.g., Boyle, Ragusa-Salerno, Lanterman, & Fleisch, 2013; Gendreau, Goggin, Cullen, & Andrews, 2000; Hennigan, Kolnick, Tian, Maxson, & Poplawski, 2010). Further, technical violations of probation tend to produce longer lengths of incarceration (Roth, Kajeepeta, & Boldin, 2021). Conversely, a study that compared a lower intensity of supervision (for individuals who are at low risk for recidivism) to standard probation showed no difference in new offending and a reduction in technical violations (Barnes, Hyatt, Ahlman, & Kent, 2012). Thus, it would appear that having lower caseloads and thus more time to monitor each probationer would lead to more observations of transgressions. It also could be that more intensive supervision requirements impact a probationer’s daily functioning, interfering with scheduling and activities that would allow them to build social capital to move on from a criminal lifestyle. Overwhelmingly, research has shown that increasing probation intensity does not result in improved criminal justice outcomes and is more expensive, and in some instances, it may increase recidivism (Doleac, 2018).

With this context established, one would expect that SB416 in County B, in which caseloads were lower than in the control condition, would result in higher recidivism. Indeed, it appears paradoxical that the group with more intensive supervision in this RCT did not have higher rates of recidivism and even defied the odds and had significantly lower recidivism than standard probation (in which caseloads were higher, so there was less monitoring). This feat might be due to the “hybrid” approach to probation supervision that SB416 takes. As Hyatt and Barnes (2017) describe: “a hybrid approach reduces offending through exposure to therapeutic interventions, and not due to the increased intensity of supervision contacts.” While this depiction is not entirely true of SB416 (i.e., lower caseloads meant more probation contact), the SB416 team emphasized enforcement as well as behavioral management and social work ideals. Thus, the SB416 PO was in frequent contact with probationers, but with the intent to be supportive rather than to “catch” individuals doing wrong. Indeed, probation offices appear to be moving in this direction (Grattet, Nguyen, Bird, & Goss, 2018). Of note, however, a prior study of this hybrid approach for probationers with substance use problems, a similar population to the one in our trial, found no significant difference in outcomes compared to standard probation (Guydish et al., 2011). In PAU for County B, higher caseloads in standard probation would have presumably made it harder to detect transgressions, which according to prior research should have resulted in equivalent or even lower recidivism; however, we found an intervention effect of lower recidivism for SB416 where supervision was more intense.

A second potential explanation for the findings pertains to the investigators’ observation of a difference in how the DA and CC stakeholders in Counties A and B worked with one another. A critical element of SB416 involves close collaboration between the DA and CC departments. Ideally, this takes the form of regular communication between DAs and POs regarding offender progress so that decisions can be made rapidly about rewards/sanctions or other interventions. When this trial began, County A already had a long and well-established history of such cross-system collaboration. In fact, this style of partnership appeared to be the norm in County A, and it was applied to all cases on supervision, not just those participating in the SB416 program. In contrast, County B did not have a history of effective collaboration between its DA and CC departments prior to the start of this trial. To the contrary, the departments had a strained relationship characterized by mistrust and limited communication. Admittedly, the DA department for County A was well-resourced (84 full-time positions) compared to County B (64 full-time positions); combined with a more resourced CC department and a lower population (see above), County A DAs and POs were potentially afforded more availability for collaboration compared to County B. County B’s participation in the RCT brought about a large change in this regard, but that change was condition specific. That is, in County B, oversight on all SB416 cases was concentrated under a single DA (to replicate the SB416 program procedures in County A), and that DA communicated regularly (via phone, email, and in-person) with the SB416 PO (again, to replicate the SB416 program procedures). Over the first 6–12 months of the trial, the SB416 procedures generated a strong working relationship between the SB416 DA and PO in County B, bolstered by shared goals (community safety and offender rehabilitation), mutual respect, and transparent communication. However, the same cannot be said for the DAs and POs working with the PAU cases in County B; those DAs and POs rarely communicated with one another, and a degree of mistrust persisted. This was likely due to County B being under-resourced for effective collaboration to occur. This collaboration difference might have contributed to the detection of an intervention effect in County B, but not in County A. Perhaps the intervention effect in County B is partly due to the marked difference in DA and PO collaboration across the SB416 and PAU conditions in that county, whereas in County A collaboration was high and similar for both conditions. In sum, these considerations suggest that reduced caseload size and enhanced collaboration between the DA and PO, even in the face of a department being under-resourced, might be key ingredients for achieving SB416 intervention effects.

Past studies of diversion programs are characterized by varied methodological weaknesses (Harvey et al., 2007; Hayhurst et al., 2019; Lange et al., 2011). The current study enhances the rigor of research in this area via its (1) RCT design, (2) moderately large sample size, (3) high participant recruitment rate, (4) manualized intervention protocol, (5) well-defined and objective outcome variables, (6) lengthy follow up period, and (7) use of intention-to-treat analyses. The successful completion of this trial speaks to the feasibility of conducting RCTs of diversion programs in partnership with real-world justice systems and in community-based settings. Thus, this study might serve as a model for others aiming to apply rigorous RCT methodology to the evaluation of other similar diversion initiatives.

Of course, the findings from this trial need to be interpreted in light of a few limitations. First, although appropriate analytic methods were used to accommodate variability in each participant’s time at risk for recidivism, the study would have been stronger if all participants had a full three-year follow-up window. Second, due to budget constraints, this study did not collect information on which participants were assigned to which POs in the PAU condition. Future studies should consider doing so in order to empirically test whether variation in caseload size across POs has an impact on outcomes. Third, to ensure strong fidelity of SB416 implementation, the intervention was manualized with structured decision trees, checklists, and forms. However, the use of more objective and ongoing fidelity monitoring methods was beyond the budget for this trial. In County A, the SB416 program had been implemented for a number of years, while in County B it was new. The field of Implementation Science has established that an unintentional shift in implementation can occur over time, known as “program drift,” which can lead to a decrease in program effectiveness (Chambers, Glasgow, & Stange, 2013). However, some degree of acceptable modification is expected for local contexts, without impacting the core aspects of a program that would lead to effectiveness (Wiltsey Stirman, Baumann, & Miller, 2019). We have no reason to suspect that County A’s fidelity had waned over time. Further, we have no reason to believe that SB416 program contacts differed by county. Indeed, both counties adhered to Oregon State policy on the minimum number of contacts for probation services. Similarly, the substance use treatment providers in both counties strictly followed ASAM recommendations for treatment dosage. Mentorship contacts varied somewhat depending on participant needs, although across both counties, the typical number of contacts was 2–3 times per week. Nevertheless, our study was unable to rule-out potential county-level differences in these areas. Thus, future studies should incorporate stronger fidelity monitoring methods, including measurement of service contacts via archival records and measurement of program delivery via observed interactions between SB416 participants and program staff (i.e., POs, treatment providers, and mentors).

4.1. Conclusions and implications

Findings from this RCT suggest that an amalgamation of countyspecific factors might make a difference for SB416 to achieve an effect. Specifically, it appears this program can yield reduced recidivism when implemented in a setting characterized at baseline as having low justice system resources (and as a result, high PO caseload sizes) and limited cross-system collaboration. Indeed, within County B where an intervention effect was observed, the SB416 condition adopted a low caseload and emphasized strong stakeholder collaboration, which was a dramatic departure from the standard operating procedures in that county. The absence of a similar intervention effect in County A might be due to the fact that POs in both the SB416 and control conditions already had low caseloads and a good history of stakeholder collaboration when this study began. Anecdotally, CC leaders in County A noted that the collaborative spirit in their office was a byproduct of having implemented SB416 for several years prior to the start of this trial. That is, because strong collaboration was perceived as beneficial for SB416 cases, CC in County A gradually began reinforcing this approach for all of its POs. This raises an important question: Is the full SB416 program necessary for reducing recidivism or does (a) better funding that allows for lower caseload sizes and (b) an emphasis on strong stakeholder collaboration suffice? Future research is needed to answer this question.