Abstract

Replication-coupled DNA repair and damage tolerance mechanisms overcome replication stress challenges and complete DNA synthesis. These pathways include fork reversal, translesion synthesis, and repriming by specialized polymerases such as PRIMPOL. Here, we investigated how these pathways are used and regulated in response to varying replication stresses. Blocking lagging-strand priming using a POLα inhibitor slows both leading- and lagging-strand synthesis due in part to RAD51-, HLTF-, and ZRANB3-mediated, but SMARCAL1-independent, fork reversal. ATR is activated, but CHK1 signaling is dampened compared to stalling both the leading and lagging strands with hydroxyurea. Increasing CHK1 activation by overexpressing CLASPIN in POLα-inhibited cells promotes replication elongation through PRIMPOL-dependent repriming. CHK1 phosphorylates PRIMPOL to promote repriming irrespective of the type of replication stress, and this phosphorylation is important for cellular resistance to DNA damage. However, PRIMPOL activation comes at the expense of single-strand gap formation, and constitutive PRIMPOL activity results in reduced cell fitness.

The replication checkpoint regulates DNA repriming to promote optimal outcomes to replication obstacles.

INTRODUCTION

Replication stress tolerance pathways including fork reversal, translesion synthesis (TLS), and repriming by PRIMPOL facilitate completion of DNA synthesis when replication forks encounter obstacles like DNA damage that cause polymerase stalling. Fork reversal catalyzed by the motor enzymes SMARCAL1, ZRANB3, and HLTF in cooperation with the recombinase RAD51 slows replication and may promote template switching or excision repair (1). TLS polymerases can use the damaged template for synthesis and bypass DNA lesions, thereby facilitating replication fork progression (2). PRIMPOL promotes DNA repriming downstream of a lesion or replication block to facilitate fork restart following ultraviolet (UV) damage and is important for interstrand cross-link traverse (3–7). Other studies indicate that PRIMPOL can act as a TLS polymerase in the presence of bulky adducts, prevents RNA-DNA hybrid (R-loop) formation, and is important for tolerance of G4-quadruplex accumulation by repriming downstream from this obstacle (8–10).

While all three replication stress tolerance mechanisms can help complete DNA synthesis, they yield different outcomes. Fork reversal may promote error-free repair or bypass, but reversed forks are potential targets of nucleases that can generate unwanted nascent strand resection or fork cleavage (11, 12). TLS often results in mutations (2). Repriming leaves a single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) gap that can be prone to breakage or accumulation of lesions that form more readily in ssDNA (13). Thus, which pathway operates has important consequences for genome stability. These pathways also act in response to many cancer therapeutic agents, thereby determining the efficacy of these treatments (14).

We were interested in understanding the regulatory mechanisms controlling these pathways and whether the type of replication stress might influence which mechanism(s) operates. Previous studies found that fork reversal is a near-universal response to replication stress in human cells (15) and identified important functions for the ATR replication stress response pathway in regulating reversal in part through phosphorylation of SMARCAL1 (12, 16). ATR also regulates repriming through transcriptional induction of PRIMPOL (17). We expected that additional regulatory mechanisms are likely needed to generate optimal outcomes.

We found that inhibition of DNA polymerase α (POLα) using the selective inhibitor CD437 (18) rapidly reduces both lagging- and leading-strand synthesis within minutes of treatment, indicating coupling of leading-strand synthesis to repriming of the lagging strand. Fork slowing is partly dependent on RAD51, ZRANB3, and HLTF, suggesting that some fork reversal is involved. However, slowing is independent of SMARCAL1, providing evidence that differences in substrate specificity underlie the need for multiple fork reversal enzymes. PRIMPOL repriming does not appear to substitute for POLα on the lagging strand under these conditions, although it is recruited to chromatin. Although ATR is active, CHK1 is activated less by Polα inhibition than replication stress induced by hydroxyurea (HU) that blocks both leading- and lagging-strand polymerases through nucleotide depletion. In these circumstances, CHK1 activation can be increased by overexpressing the CHK1 mediator CLASPIN. Unexpectedly, this perturbation also causes a CHK1-dependent increase in fork speed due to engagement and activation of PRIMPOL on the leading-strand template. CHK1 directly phosphorylates PRIMPOL at S255 both in vitro and in cells, and this phosphorylation is required for PRIMPOL repriming activity. This regulation also happens in response to HU, cisplatin, and UV treatment, indicating that it is independent of the type of replication stress. Repriming facilitates increased DNA synthesis but at the expense of generating ssDNA gaps. Furthermore, cells expressing constitutively active PRIMPOL in which S255 is replaced with a phosphomimetic mutant exhibit reduced growth, while cells expressing a nonphosphorylatable mutant are hypersensitive to DNA damage. These results reveal important mechanisms for how replication stress tolerance pathways are regulated to promote optimal cellular outcomes.

RESULTS

Inhibiting lagging-strand synthesis immediately slows leading-strand synthesis

Blocks to lagging-strand synthesis generally would not be expected to stall helicase movement or Polε synthesis on the leading strand (19–21). However, treating cells with a Polα-specific inhibitor (CD437) even for a short time caused rapid slowing of replication fork progression, from 915 ± 21 base pairs per minute to 625 ± 14 base pairs per minute with only 5 min of CD437 treatment (Fig. 1A). Both leading- and lagging-strand synthesis must be slowed since continued DNA synthesis on either one or both strands would look indistinguishable in the DNA combing assay. By 30 min of treatment, replication elongation decreased by over 50% irrespective of the cell type tested (Fig. 1A and fig. S1A).

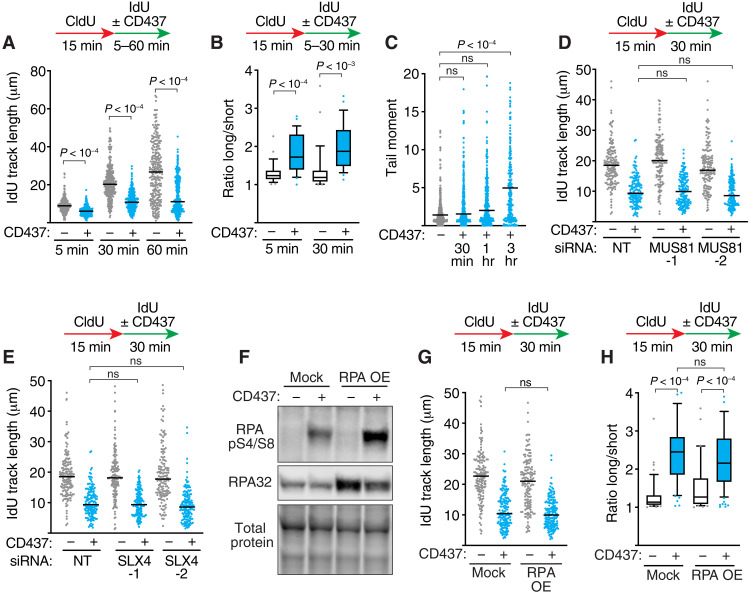

Fig. 1. POLα inhibition rapidly slows replication elongation.

(A) HCT116 cells were labeled with CldU and IdU and treated with 5 μM CD437 for the indicated times before DNA combing. Individual IdU fiber lengths are plotted. Median is indicated. (B) Fork asymmetry ratios (long fiber/short fiber) in untreated or HCT116 cells treated for 5 or 30 min with 5 μM CD437. (C) Neutral comet assay of HCT116 cells treated with 5 μM CD437 for the indicated times. (D and E) DNA combing of HCT116 cells transfected with nontargeting (siNT), MUS81, or SLX4 small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) and treated with 5 μM CD437. The same siNT control was used for both experiments in (D) and (E) since the experiments were completed at the same time. (F) Immunoblot of HCT116 cells with or without RPA overexpression (RPA OE; all three subunits) and treated with 5 μM CD437 for 30 min. (G) DNA combing of HCT116 cells overexpressing RPA and treated with 5 μM CD437. (H) Fork asymmetry ratios (long fiber/short fiber) from HCT116 cells with or without RPA overexpression treated for 30 min with 5 μM CD437. P values were derived from analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunn’s multiple comparisons post-test in all panels. Box and whiskers plots show the median value with 25th to 75th percentiles. All experiments were completed at least three times with similar results. ns, not significant.

In addition to slowing, 5 min of CD437 treatment caused a large increase in replication fork asymmetry (Fig. 1B). Asymmetric replication forks can result when one of the forks originating from an origin of replication collapses and generates a double-strand break (DSB). However, DSBs were not detectable by a neutral comet assay until at least 1 hour of Polα inhibition (Fig. 1C). The failure to detect breaks at earlier time points is unlikely to simply be because of insufficient assay sensitivity since we can detect DSBs under other conditions with lower levels of asymmetry (22). Instead, the rapid fork slowing and fork asymmetry at early time points after CD437 are likely due to differential pausing of DNA synthesis of bidirectional forks and not breakage. Consistent with this conclusion, DNA synthesis rates are not rescued by inactivating either the MUS81 nuclease or SLX4 nuclease scaffold that cleaves replication forks in response to genotoxic stress (Fig. 1, D and E, and fig. S1, B and C) (12, 23). A previous report found that Polα inhibition exhausts the ssDNA binding protein RPA within an hour, yielding replication catastrophe (24). However, overexpression of RPA did not rescue the replication fork speed or asymmetry observed at 30 min, suggesting that the shorter treatment times did not cause RPA exhaustion (Fig. 1, F to H). These data suggest that leading-strand synthesis is tightly coupled to repriming of lagging strands, and DSBs are a later consequence of lagging-strand interference.

Fork slowing in response to lagging-strand replication stress is partially due to fork reversal

Past studies indicate that fork slowing in response to genotoxic stress by multiple agents including camptothecin, mitomycin C, and UV is often due to fork reversal (25). To test whether fork reversal is responsible for the fork slowing when lagging-strand synthesis is inhibited, we silenced RAD51 that is required for reversal (15). RAD51 silencing causes a small (~20%) but consistent increase in fork speeds in CD437-treated cells (Fig. 2, A and B, and fig. S1D). In addition, depleting two fork reversal DNA translocases, ZRANB3 or HLTF, independently or knocking out all three translocases, ZRANB3, HLTF, and SMARCAL1 (TripleΔ), modestly increased fork speeds (Fig. 2C and fig. S1E). These data suggest that fork reversal contributes a small amount to the fork slowing caused by POLα inhibition. However, silencing SMARCAL1 alone with small interfering RNA (siRNA) or inactivating it by CRISPR-Cas9–mediated gene editing did not prevent fork slowing (Fig. 2D and fig. S1, D, F, and G). The involvement of ZRANB3 and HLTF, but not SMARCAL1, suggests that one reason that there are multiple fork reversal enzymes in cells is that they act on different stalled fork structures. This conclusion is consistent with biochemical data that showed that SMARCAL1 acts preferentially on forks with leading-strand template ssDNA bound by RPA and is inhibited by RPA bound to ssDNA on the lagging-strand template, whereas HLTF and ZRANB3 do not exhibit this preference (26, 27).

Fig. 2. Fork slowing in response to lagging-strand stress is partially due to fork reversal.

(A to D) DNA combing assays performed in HCT116 cells transfected with the indicated siRNAs and labeled with CldU (15 min) and IdU (30 min). Cells were treated with 5 μM CD437 for 30 min during the IdU labeling as indicated. Representative experiments are presented in (A), (C), and (D), with P values derived from ANOVA with Dunn’s multiple comparisons post-test. The individual mean values from 10 experiments are shown in (B) in which values were normalized to the nontargeting (NT) control. The line and error bars are the mean of the means ± SEM. P value was derived from Mann-Whitney test.

CLASPIN overexpression and CHK1 activation increase fork speeds during lagging-strand replication stress

We next examined the signaling consequences of interfering with lagging-strand priming. The DNA damage response kinase ATR is activated by CD437 treatment as revealed by robust RPA32 S4/S8 and S33 phosphorylation, and a modest amount of CHK1 phosphorylation (Fig. 3, A and B). In contrast to CD437, 30 min of HU treatment causes robust CHK1 phosphorylation but undetectable levels of RPA32 phosphorylation.

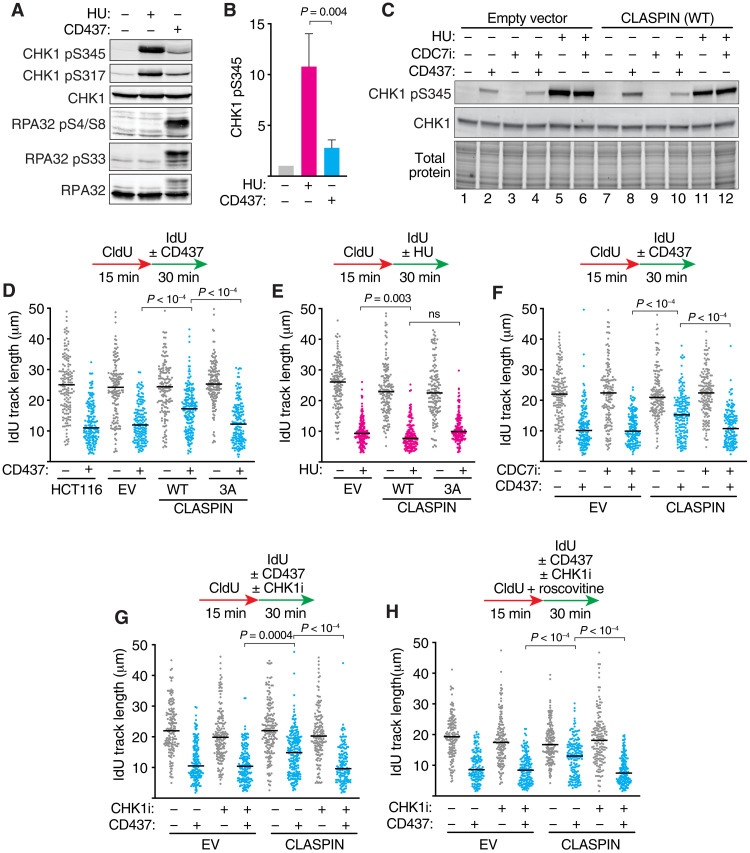

Fig. 3. CLASPIN overexpression and CHK1 activation promote DNA synthesis during lagging-strand stress.

(A) Immunoblots of protein lysates of HCT116 cells treated with 3 mM HU or 5 μM CD437 for 30 min. (B) CHK1 pS345 signal was quantitated from three experiments. P value was derived from ANOVA with Holm-Šídák multiple comparisons post-test. (C) Immunoblots of HCT116 cells overexpressing an empty vector (EV) or CLASPIN and treated with 5 μM CD437 and 20 μM CDC7 inhibitor for 30 min where indicated. (D to H) DNA combing of HCT116 overexpressing WT or triple-alanine mutant CLASPIN (3A). Cells were labeled with CldU (15 min) and IdU (30 min) and treated with either 5 μM CD437 or 50 μM HU during the IdU labeling period where indicated. CDC7 inhibitor (CDC7i; 20 μM), CHK1 inhibitor (CHK1i; 2 μM), or roscovitine (10 μM) was added during the IdU labeling period where indicated. All panels show a representative of at least two biological replicates. P values were derived from ANOVA with Dunn’s multiple comparisons post-test.

ATR-dependent CHK1 phosphorylation depends on CLASPIN, whereas RPA32 phosphorylation does not (28). In addition, CLASPIN and the yeast homolog Mrc1 maintain replication fork progression and fork stability at stalled forks, and coordinate the leading-strand polymerase with the helicase (29–33). Therefore, we hypothesized that reduced CLASPIN function at a CD437-challenged replication fork may account for the blunted CHK1 activation and slowed leading-strand synthesis in response to lagging-strand interference. To test this possibility, we generated cell lines that overexpress CLASPIN. Consistent with our prediction, CLASPIN overexpression modestly but consistently elevates CHK1 phosphorylation when Polα is inhibited (Fig. 3C and fig. S2, B and C). In contrast, it does not affect CHK1 phosphorylation in response to HU (Fig. 3C, compare lanes 5 and 11). We also generated cell lines overexpressing a triple-alanine (T916A, S945A, S982A) CLASPIN mutant that is unable to bind and facilitate CHK1 activation (34–36). Both wild-type (WT) and mutant CLASPIN cell lines have similar CLASPIN expression levels (fig. S2A); however, CHK1 activation is not elevated when the CLASPIN 3A mutant is expressed (fig. S2, B and C).

Overexpression of WT CLASPIN, but not the 3A mutant, increases elongation rates in CD437-treated cells, suggesting that its ability to activate CHK1 in these circumstances can promote fork progression (Fig. 3D). In contrast, CLASPIN overexpression did not increase elongation rates in cells treated with HU (Fig. 3E).

CLASPIN-dependent CHK1 activation is dependent on the CDC7 kinase, which phosphorylates the CHK1-binding domain of CLASPIN (37). CHK1 activation in CD437-treated cells is reduced when CDC7 is inhibited (Fig. 3C and fig. S2C). Furthermore, CDC7 inhibition reduces the elevated CHK1 phosphorylation caused by WT CLASPIN overexpression but has no effect in cells overexpressing the CLASPIN 3A mutant (fig. S2C). CDC7 inhibition also abolishes the increase in replication fork speed observed in CLASPIN-overexpressing cells, further tying this rescue to the ability of CLASPIN to promote CHK1 activation (Fig. 3F).

We next directly tested whether CHK1 signaling is needed for the increase in fork speeds generated by CLASPIN overexpression in CD437-treated cells. Acute inhibition of CHK1 with the small-molecule inhibitor MK-8776 prevents the increased DNA replication elongation rates in these circumstances (Fig. 3G). CHK1 inhibition prevents the increase in fork speed regardless of whether unscheduled origin firing is induced by CHK inhibition since the results are the same when initiation is blocked using the cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor roscovitine (Fig. 3H) (38). Together, these data indicate that increasing activation of CHK1 during lagging-strand synthesis inhibition increases DNA replication elongation speed.

The CLASPIN-CHK1 signaling axis promotes PRIMPOL-dependent replication fork progression

One way fork speeds can be increased in the presence of replication stress is to engage the repriming polymerase PRIMPOL (17, 39). Therefore, we tested whether PRIMPOL is required for the increased fork speeds when CLASPIN is overexpressed. PRIMPOL inactivation abolishes the replication fork speed increase caused by CLASPIN overexpression in cells treated with POLα inhibitor (Fig. 4, A and B). We next used a modified DNA combing assay that incorporates an S1 nuclease digestion step (17). In this assay, if ssDNA gaps are present on both the leading and lagging strand during the second nucleoside analog labeling period, the fibers will be digested by S1 nuclease, resulting in smaller fiber track lengths. If, however, ssDNA exists only on one strand, the track lengths will be similar to undigested samples. In cells treated with CD437 inhibitor alone, elongating DNA fibers are S1 nuclease resistant, consistent with ssDNA gaps only being present on the lagging-strand template and perhaps lacking of engagement of PRIMPOL. In contrast, the elongating DNA fibers are sensitive to S1 nuclease in cells overexpressing CLASPIN and treated with Polα inhibitor (Fig. 4C). These results are consistent with PRIMPOL acting on the leading strand in these circumstances, yielding an increased fork progression rate at the expense of generating leading-strand ssDNA replication gaps.

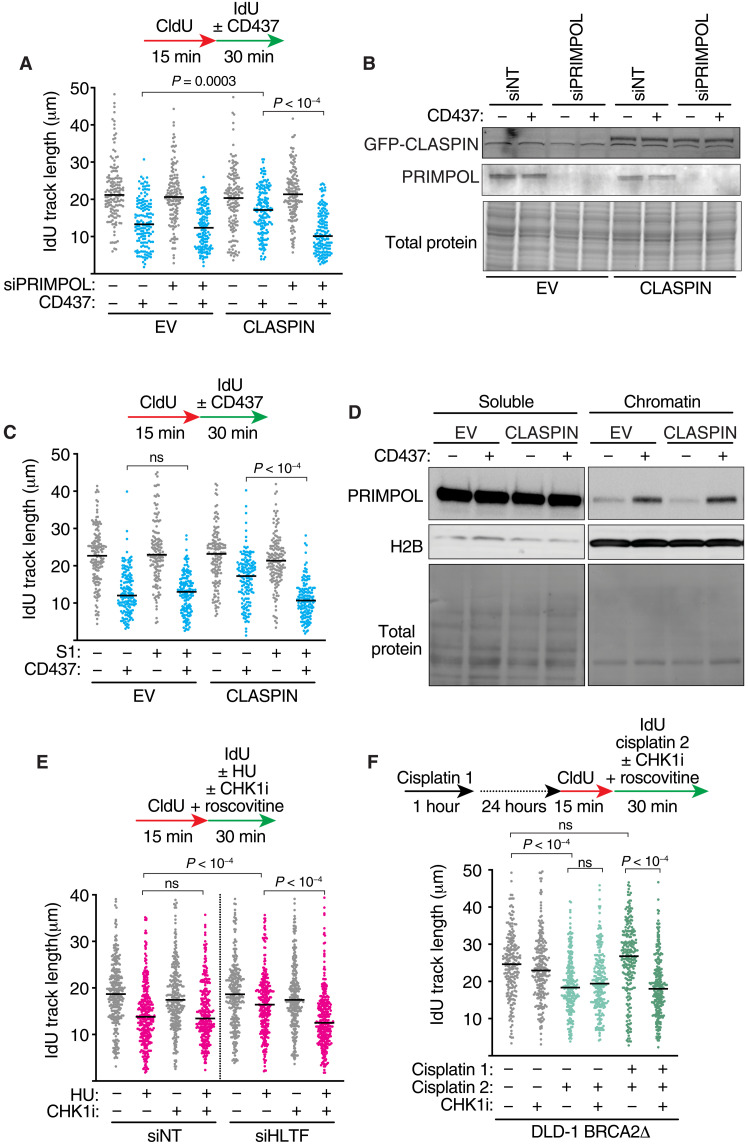

Fig. 4. CLASPIN-CHK1 signaling drives PRIMPOL-dependent repriming to increase fork speeds and generate ssDNA gaps.

(A and B) HCT116 cells expressing an EV or CLASPIN were transfected with nontargeting or PRIMPOL siRNAs and treated with 5 μM CD437 for 30 min as indicated before (A) DNA combing or (B) immunoblotting of cell lysates. (C) DNA combing was completed in HCT116 cells expressing an EV or CLASPIN as in (A), except DNA samples were treated with S1 nuclease before combing where indicated. (D) Immunoblot of CLASPIN-overexpressing cells after chromatin fractionation. Cells were treated with 5 μM CD437 for 30 min where indicated. (E) DNA combing was completed after transfection of HCT116 cells with the indicated siRNAs. HU (50 μM), CHK1i (2 μM), and roscovitine (10 μM) were added during the IdU labeling period, as indicated. (F) DNA combing was completed in DLD-1 BRCA2Δ cells after treatment with cisplatin, CHK1i, and roscovitine, as indicated. Cisplatin at 50 μM and 150 μM was used in the first and second treatments, respectively. P values were derived from ANOVA with Dunn’s multiple comparisons post-test for all DNA combing experiments.

PRIMPOL is recruited to chromatin in CD437-treated cells irrespective of CLASPIN overexpression (Fig. 4D), but the S1 nuclease data indicate that PRIMPOL is only engaged when CHK1 activity is increased by CLASPIN overexpression, suggesting that CHK1 may regulate PRIMPOL activity. To test whether this is a general feature of PRIMPOL repriming regulation or specific to CD437-treated cells, we examined two other circumstances in which repriming is active. PRIMPOL repriming is favored in HU-treated cells when the fork reversal translocase HLTF is inactivated, yielding increased fork speeds and ssDNA gaps (39). As previously observed, HLTF suppression results in an increase in fork speed in response to HU-induced replication stress (Fig. 4E and fig. S3A). This increase in DNA synthesis is prevented by CHK1 inhibition, suggesting that in this circumstance PRIMPOL function is also CHK1 dependent. Cells were treated with roscovitine in this experiment to prevent CHK1 inhibition from causing unscheduled origin firing.

PRIMPOL is also reported to be used when BRCA2-deficient cells are treated with a two-dose regimen of the chemotherapeutic agent cisplatin (17). In these circumstances, the activation of the PRIMPOL repriming pathway over fork reversal was found to be caused by ATR-dependent transcriptional induction of PRIMPOL expression (17). As expected, we found an increase in fork speed in BRCA2-deficient DLD-1 colorectal adenocarcinoma cells pretreated with cisplatin 24 hours before performing the molecular combing assay in the presence of a second cisplatin treatment (Fig. 4F). However, coincubation with CHK1 inhibitor only during the second dose prevents the increase in replication fork speed (Fig. 4F), indicating that CHK1 is needed for PRIMPOL repriming activity in these circumstances. CHK1 inhibition does not alter expression levels of PRIMPOL in the 30-min time frame in which the drug was administered (fig. S3B). Together, these data indicate that CHK1 signaling is required for PRIMPOL repriming activity irrespective of the type of replication stress.

CHK1 phosphorylates PRIMPOL to promote PRIMPOL repriming activity

To understand the mechanism by which CHK1 regulates PRIMPOL, we searched for CHK1 phosphorylation motifs (R-X-X-S) in the PRIMPOL sequence (40). Human PRIMPOL contains a putative CHK1 phosphorylation consensus site at amino acid residue S255 that resides within a region of undefined structure in PRIMPOL (41). This motif is conserved among nonrodent, placental mammals (Fig. 5A), and S255 phosphorylation has been observed in phospho-proteomic datasets (42, 43).

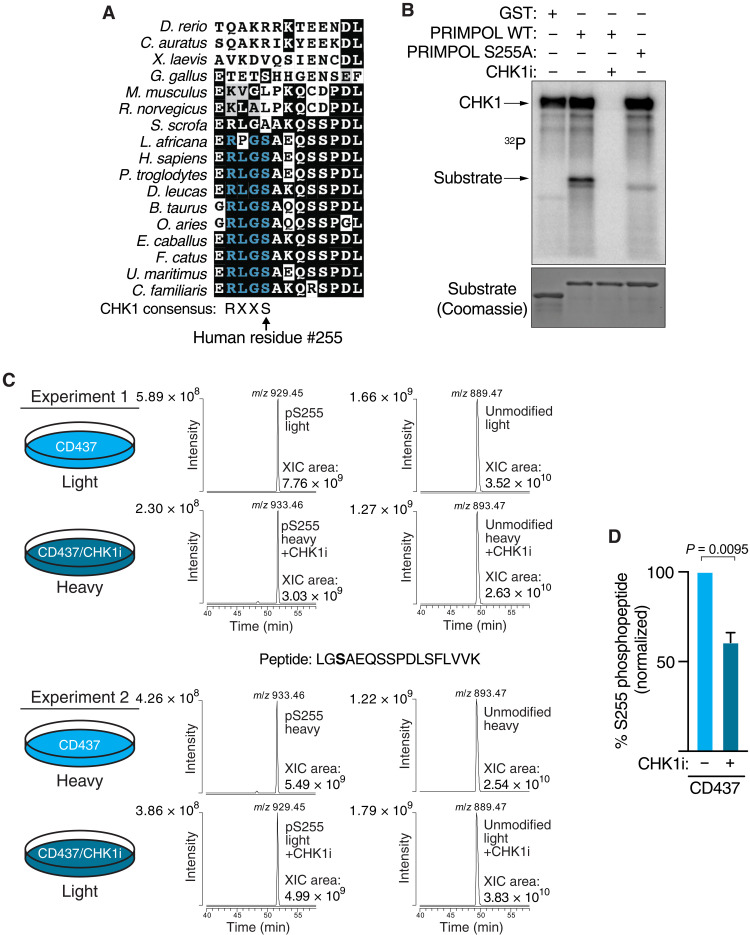

Fig. 5. CHK1 phosphorylates PRIMPOL on serine-255.

(A) Sequence alignment of PRIMPOL at putative CHK1 phosphorylation consensus site (R-X-X-S). (B) Kinase assay of purified full-length CHK1 with GST, GST-PRIMPOL peptide, or GST-PRIMPOL-S255 peptide substrates. CHK1i (10 μM) was added to the reaction where indicated. (C) Immunoprecipitation of PRIMPOL with SILAC MS was performed in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells labeled with either light or heavy amino acid isotopes and treated with 5 μM CD437 with and without 2 μM CHK1i (MK-8776). Extracted ion chromatograms (XICs) for unmodified and S255 phosphorylated PRIMPOL peptide were generated for observed precursor ions in SILAC label-swapped replicate experiments. Peak areas (XIC area) from XICs were used to calculate abundance of the unmodified and S255 phosphorylated PRIMPOL peptides. (D) Graph shows the relative abundance of the PRIMPOL phospho-S255 peptide in the absence and presence of CHK1i. P value was derived from Student’s t test.

To test whether PRIMPOL S255 is a direct target of CHK1, we performed in vitro kinase assays using a PRIMPOL fragment containing S255 as the substrate. CHK1 autophosphorylates itself and phosphorylates the WT PRIMPOL peptide fused to glutathione S-transferase (GST) (Fig. 5B). In contrast, it does not phosphorylate GST protein alone and mutation of the PRIMPOL peptide to change S255 to alanine largely eliminates phosphorylation (Fig. 5B). In addition, a CHK1 kinase inhibitor blocks S255 phosphorylation.

To determine whether CHK1 phosphorylates PRIMPOL in human cells, we used stable isotope labeling of amino acids in cell culture and immunoprecipitation followed by quantitative mass spectrometry (SILAC-IP-MS) to examine S255 phosphorylation. We were able to detect PRIMPOL S255 phosphorylation by MS when PRIMPOL was isolated from cells treated with CD437. Phosphorylation was reduced by ~40% when cells were treated with CHK1 inhibitor (Fig. 5, C and D), indicating that this phosphorylation is at least partly CHK1 dependent.

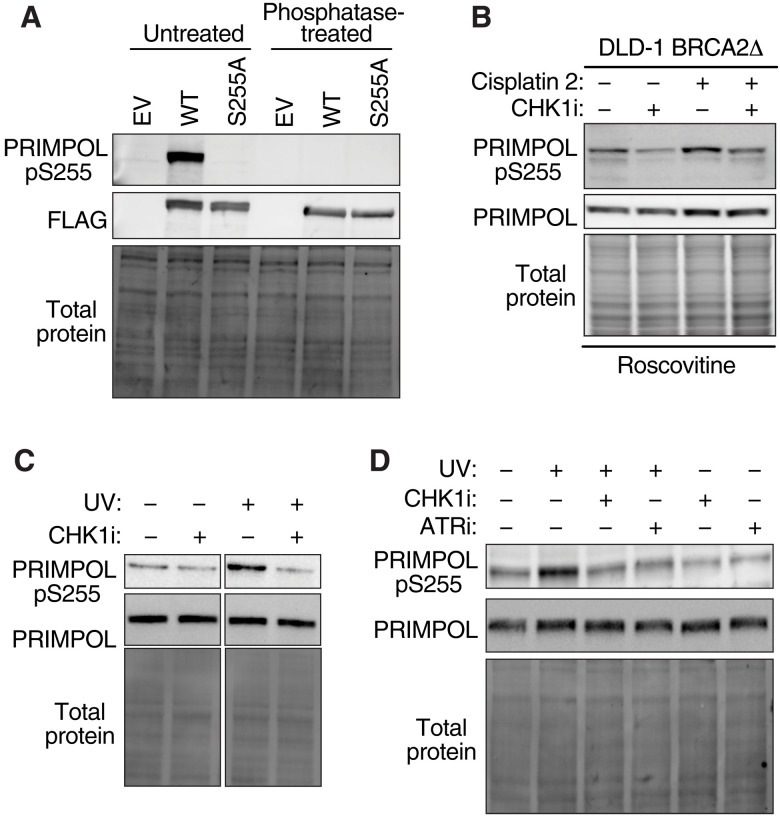

Next, we raised a phosphopeptide-specific antibody to PRIMPOL pS255 to further confirm and characterize S255 phosphorylation. This antibody recognizes WT PRIMPOL, but not the S255A mutant on immunoblots (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, antibody recognition was abolished by treating lysates with lambda phosphatase, indicating that it is selective to PRIMPOL phosphorylated on S255 (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6. PRIMPOL is phosphorylated on S255 in response to genotoxic stress.

(A) Immunoblotting of cell lysates obtained from HEK293Ts overexpressing EV, WT PRIMPOL, or PRIMPOL S255A. Lysates were treated with lambda phosphatase where indicated. (B) Immunoblotting of cell lysates in DLD-1 BRCA2Δ cells after treatment with cisplatin, 2 μM CHK1i, and 10 μM roscovitine, as indicated. Cisplatin at 50 μM (1 hour) and 150 μM (30 min) was used in the first and second treatments, respectively, to mimic the DNA combing experiments. (C) Immunoblot demonstrating increased phosphorylation of PRIMPOL S255 following UV treatment (20 J/m2) and 2-hour incubation. Cells were treated with CHK1i, where indicated, for the last 30 min of the incubation period. Cropped images were taken from the same immunoblot to remove intervening lanes. (D) Immunoblotting of cell lysates in S-phase synchronized HCT116 cells 2 hours after UV treatment. Cells were treated with 2 μM CHK1i or 1 μM ATR inhibitor (ATRi), as indicated, for the last 30 min before harvesting.

To determine whether S255 of PRIMPOL is phosphorylated under conditions in which PRIMPOL is active, we examined BRCA2-deficient cells treated with the two-dose regimen of cisplatin, which transcriptionally up-regulates PRIMPOL (17). We observed both an increase in total levels of PRIMPOL and S255 phosphorylated PRIMPOL (Fig. 6B). PRIMPOL phosphorylation in this circumstance is partially dependent on CHK1 kinase activity (Fig. 6B).

Previous studies indicate that PRIMPOL is important for DNA damage tolerance in response to UV photoproducts (4, 5, 44). UV treatment of cells also increases S255 phosphorylation of PRIMPOL, and this increase in phosphorylation is partially dependent on CHK1 kinase and ATR activity (Fig. 6, C and D). No increase of total PRIMPOL was observed under these conditions. These data confirm that PRIMPOL is actively phosphorylated upon genotoxic stress, and the phosphorylation is, in part, due to CHK1 kinase activity, although another kinase may also be involved since CHK1 inhibition did not fully eliminate S255 phosphorylation.

Phosphorylation of S255 promotes PRIMPOL repriming activity

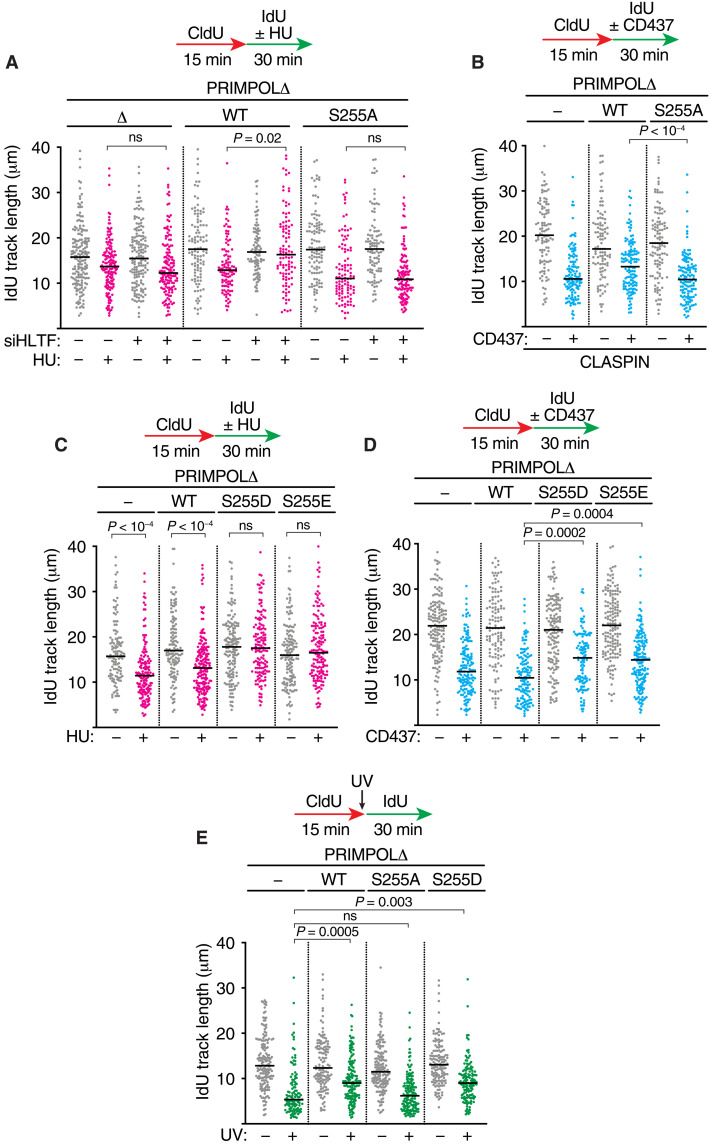

To determine whether S255 phosphorylation is required for PRIMPOL repriming activity, we complemented PRIMPOL knockout (PRIMPOLΔ) cells with either WT PRIMPOL or a S255A nonphosphorylatable mutant. Both WT PRIMPOL and PRIMPOL S255A are expressed at similar levels (fig. S3C). As expected, silencing HLTF in the cells complemented with WT PRIMPOL made the forks resistant to HU-induced slowing due to PRIMPOL repriming (Fig. 7A). In contrast, PRIMPOL S255A was unable to promote an increase in fork speed after HLTF silencing in HU-treated cells (Fig. 7A). In addition, WT PRIMPOL, but not the PRIMPOL S255A protein, facilitated increased elongation rates in CD437-treated cells overexpressing CLASPIN (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7. CHK1 phosphorylation of PRIMPOL on serine-255 is required for repriming.

(A to E) DNA combing was completed in PRIMPOLΔ cells complemented with WT, S255A, S255D, or S255E PRIMPOL. Cells in (A) were transfected with nontargeting or HLTF siRNAs, while cells in (B) were transfected with cDNAs to overexpress WT CLASPIN. (A to D) HU (50 μM) or CD437 (5 μM) was added during the IdU labeling period. (E) Cells were exposed to UV (20 J/m2) before IdU labeling. P values were derived from ANOVA with Dunn’s multiple comparisons post-test. All experiments were completed at least twice.

To further confirm that S255 phosphorylation promotes PRIMPOL repriming, we tested phosphomimetic mutants. As would be predicted whether S255 phosphorylation activates PRIMPOL, expression of either an S255D or PRIMPOL 2S55E mutant in PRIMPOLΔ cells prevents fork slowing and generates ssDNA gaps in response to HU treatment (Fig. 7C and fig. S3D).

Constitutive activation of the S255 phosphomimetic mutants was further confirmed by examining fork movement in response to CD437 in PRIMPOLΔ cells complemented with PRIMPOL mutants. Expression of the phosphomimetic mutants is sufficient to drive faster replication elongation rates even without CLASPIN overexpression under these conditions, as would be predicted if they are constitutively active (Fig. 7D). Furthermore, WT and S255D PRIMPOL maintain higher replication fork speed following UV challenge than the nonphosphorylatable mutant S255A (Fig. 7E). Thus, S255 phosphorylation promotes PRIMPOL-dependent repriming in response to DNA damage or other obstacles that slow replication fork movement.

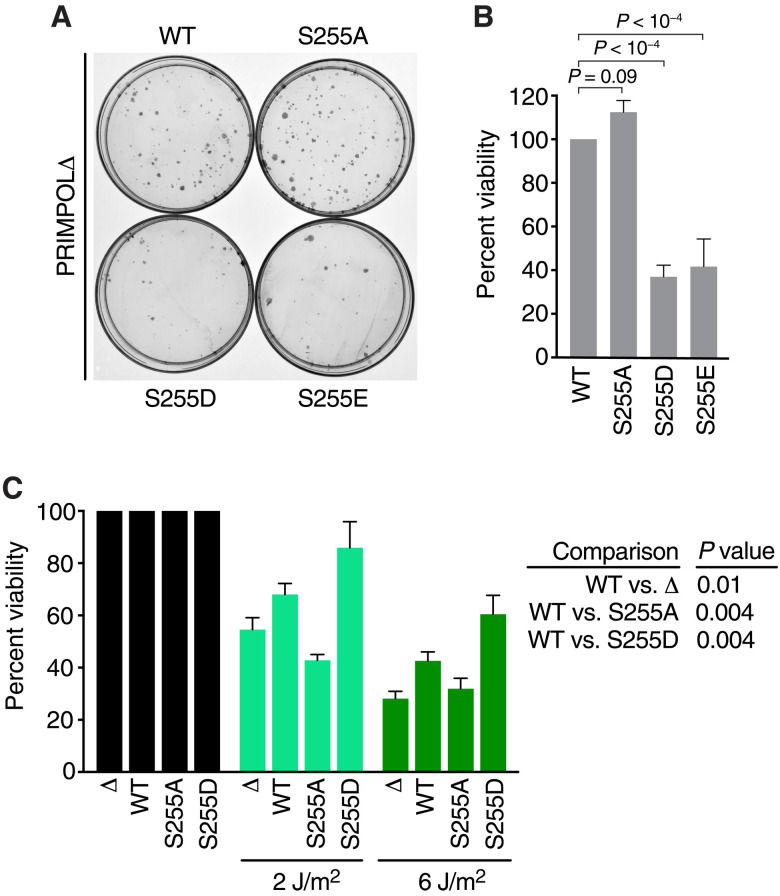

To understand the consequences of this phosphorylation-dependent regulation of PRIMPOL, we examined the viability of cells expressing the PRIMPOL mutant proteins. Overexpression of the constitutively active, phosphomimetic PRIMPOL S255D and S255E proteins caused reduced cell growth and a reduced ability to form colonies in comparison to expression of either WT or the S255A PRIMPOL (Fig. 8, A and B). As observed previously, PRIMPOL-deficient cells are hypersensitive to UV-induced DNA damage (4, 5, 44). Expression of WT PRIMPOL, but not the S255A mutant, restored some UV resistance to these cells (Fig. 8C). Furthermore, despite causing reduced viability in the absence of replication stress, the S255D phosphomimetic mutant further reduced UV sensitivity compared to the WT PRIMPOL protein (Fig. 8C). Thus, while CHK1-dependent, PRIMPOL-mediated repriming is important to facilitate completion of DNA synthesis and cell viability in the presence of replication stress, it must be regulated to maintain cell fitness.

Fig. 8. Expression of phosphomimetic mutants of PRIMPOL S255 reduces undamaged cell fitness but increases resistance to DNA damage.

(A and B) Representative images and quantitation of a clonogenic survival assays in PRIMPOLΔ cells transfected with expression plasmids encoding WT, S255A, S255D, or S255E PRIMPOL. P values were derived from ANOVA with Holm-Šídák multiple comparisons post-test. (C) Quantitation of a clonogenic survival assays in PRIMPOLΔ cells stably expressing WT, S255A, or S255D PRIMPOL proteins and treated with UV as indicated. P values were derived from ANOVA with Holm-Šídák multiple comparisons post-test.

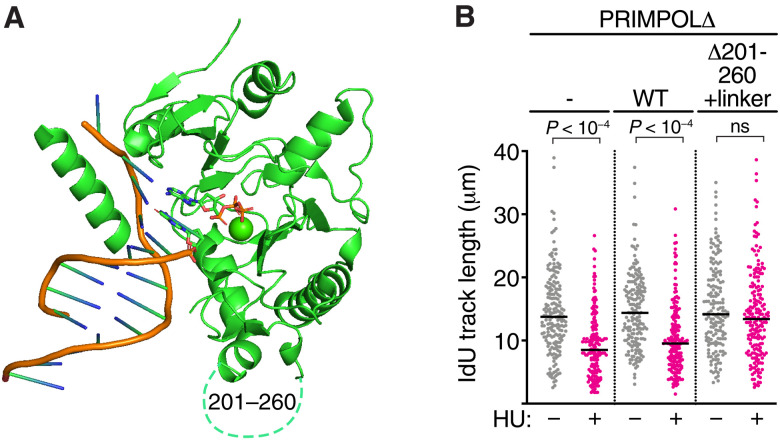

S255 phosphorylation prevents inhibition by a disordered region of PRIMPOL

Neither ATR nor CHK1 kinase activity is required to recruit PRIMPOL to chromatin. Combined treatments with both UV and CHK1 or ATR inhibitors leads to an increase in PRIMPOL in the chromatin fraction (fig. S3, E and F) likely because of an increase in RPA-coated ssDNA that previously was shown to recruit PRIMPOL to stalled forks (45, 46).

S255 resides within a region of PRIMPOL (residues 201 to 260) that is predicted to be disordered and is not visible in previously published crystal structures (Fig. 9A) (41). We hypothesized that this loop may inhibit repriming activity and phosphorylation of the loop relieves this inhibition. To test this hypothesis, we complemented PRIMPOLΔ cells with the mutant PRIMPOL (Δ201-260+linker) in which the entire loop is replaced with a flexible linker. Consistent with our hypothesis, the PRIMPOLΔ201-260+linker protein prevents replication fork slowing during HU treatment even without HLTF silencing—phenocopying what is observed with the PRIMPOL phosphomimetic mutants (Fig. 9B and fig. S3H). This result suggests that the disordered linker containing S255 acts as an inhibitory motif for PRIMPOL repriming activity.

Fig. 9. The disordered region of human PRIMPOL containing S255 inhibits its activity.

(A) Structure of human PRIMPOL (Protein Data Bank: 5L2X) highlighting the disordered region (amino acids 201 to 260) that is not visible in the crystal structure. (B) DNA combing was completed in PRIMPOLΔ cells complemented with WT and 201-260Δ-linker treated with 50 μM HU for 30 min during the IdU labeling period. P values were derived from ANOVA with Dunn’s multiple comparisons post-test.

DISCUSSION

Replication stress tolerance pathways including fork reversal, TLS, and repriming ensure that DNA synthesis is completed, but come with different potential costs to genome stability. We discovered a mechanism by which a core component of the S-phase checkpoint, CHK1, promotes the PRIMPOL repriming pathway. Our study shows that PRIMPOL is phosphorylated by CHK1 both in vitro and in cells. This phosphorylation is needed for PRIMPOL activity in multiple replication stress response contexts. This regulation increases cellular resistance to DNA damage that stalls replication while preventing an imbalance in activities leading to reduced cellular fitness that results from overactive PRIMPOL.

CHK1 regulation of PRIMPOL is one of several mechanisms regulating repriming. PRIMPOL is recruited to DNA by RPA, which also regulates its repriming activity (7, 45, 46). PRIMPOL protein stability is maintained by the stress response–regulated deubiquitylase USP36 (47). Polymerase δ–interacting protein 2 (PolDIP2) stimulates PRIMPOL-mediated DNA synthesis (48). PRIMPOL can also be transcriptionally up-regulated in an ATR-dependent manner, and it is regulated through the cell cycle by phosphorylation of the kinase PLK1 (17, 43).

Presumably, these multiple layers of regulation prevent unwanted repriming, leading to an accumulation of ssDNA gaps behind the replication fork. Although continued replication is imperative, persistent ssDNA gaps could potentially exhaust RPA and increase genome instability. The reduced growth rate of cells expressing only the S255D or S255E phosphomimetic PRIMPOL mutants illustrates the importance of only activating repriming under specific replication stress conditions. These mutants induce repriming even under conditions where fork reversal should be predominant, thereby generating ssDNA gaps that otherwise would be avoided. Furthermore, cells expressing only a nonphosphorylatable PRIMPOL mutant phenocopy PRIMPOL loss, are hypersensitive to DNA damage, and fail to sustain replication fork elongation under conditions where PRIMPOL should be active.

Our data also suggest that the disordered loop containing S255 acts to inhibit PRIMPOL since removing the loop entirely and replacing it with a flexible linker leads to constitutive PRIMPOL activity similar to the phosphomimetic mutants. Exactly how phosphorylation alters the inhibitory action of this region remains to be determined. This region of PRIMPOL is poorly evolutionarily conserved. Rodent PRIMPOL proteins do not contain S255, and the disordered region is considerably shortened, suggesting alternative mechanisms of PRIMPOL regulation other than CHK1-dependent phosphorylation in other species.

Both the MS and phosphopeptide-specific antibody analyses show that inhibiting CHK1 does not fully eliminate S255 phosphorylation. Furthermore, while phosphorylation is increased in cells treated with replication stress and DNA damaging agents, some phosphorylation is present even under untreated conditions where PRIMPOL should not be active. Thus, further studies will be needed to understand how phosphorylation of this loop is regulated and how it alters PRIMPOL activity.

Our results also reveal that leading-strand synthesis depends on continued repriming of the lagging strand. This is consistent with another recent study that also found that Polα inhibition slows replication, but it attributed the slowing to replication catastrophe and RPA exhaustion (24). Our results indicate that replication elongation rates decrease rapidly (within 5 min of inhibitor addition) before RPA exhaustion or DSB formation. Most of the slowing we observe may be due to intrinsic coupling of leading- and lagging-strand synthesis, but some is due to fork reversal. When Polα is inhibited, RAD51, ZRANB3, and HLTF cooperate to modestly slow replication elongation; however, SMARCAL1 is not required for this effect. A lack of function for SMARCAL1 in this context is consistent with the biochemical preference of SMARCAL1 (26). On the other hand, HLTF has substrate specificity for 3′ ssDNA ends, a potential structure generated by inhibiting Polα (27, 49). Thus, substrate specificity provides at least a partial explanation for why there are multiple related fork reversal enzymes in human cells.

When an obstacle to synthesis is a DNA lesion on the lagging-strand template, repriming by POLα should allow continued fork progression (20, 21, 50). However, our data suggest that PRIMPOL is incapable of performing this repriming reaction when POLα itself is inhibited since silencing PRIMPOL does not alter replication fork elongation rates in CD437-treated cells. The lack of function of PRIMPOL in this situation is also partly due to a dampened CHK1 signaling response. Increasing CHK1 activity by overexpressing CLASPIN allows PRIMPOL to reprime the leading strand in the presence of POLα inhibitor and increase elongation rates while generating leading-strand gaps. Whether any additional synthesis happens on the lagging strand in this context is unknown.

CHK1 regulation of PRIMPOL and the phosphorylation of S255 are also important in response to replication stress induced by cisplatin, HU, and UV. This result is consistent with the observation that CHK1 is required for fork progression following UV damage (51). CHK1 likely regulates PRIMPOL in other contexts as well. PRIMPOL is not only an active polymerase in the nucleus but also important for mitochondrial replication and maintenance of mitochondrial DNA copy number (6, 52). CHK1 down-regulation results in mitochondrial defects (53), which could be partly due to the lack of PRIMPOL activation. Further studies will be needed to test this hypothesis and learn whether CHK1 phosphorylates PRIMPOL to promote its other functions such as lesion bypass synthesis and ICL (interstrand crosslink) traverse.

In conclusion, we used Polα inhibitor as a tool to study the replication stress response and DNA tolerance pathways from the context of lagging-strand synthesis inhibition. In addition to obtaining new insights into the coupling of lagging and leading-strand synthesis and the selective action of fork reversal enzymes, we also discovered that CHK1 phosphorylates PRIMPOL at serine-255 to promote PRIMPOL repriming activity and fork elongation. Further studies of these replication stress tolerance pathways will allow a better understanding of when each pathway is used, as well as their consequences for genome stability and cell survival, and potentially inform how to best use cancer therapies like ATR and CHK1 inhibitors that interfere with their regulation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines

HCT116 cells were cultured in McCoy’s 5A supplemented with 7.5% fetal bovine serum (FBS). U2OS, U2OS PRIMPOL knockout (PRIMPOLΔ), HeLa, human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T, and GP-293 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 7.5% FBS. hTERT-RPE1 cells were cultured in DMEM:F12 supplemented with 7.5% FBS. DLD-1 BRCA2 knockout (BRCA2Δ) cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium with 7.5% FBS. HEK293T cells for MS experiments were cultured in SILAC-compatible DMEM + 7.5% dialyzed FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, catalog no. A33822; R&D Systems, catalog no. S12850H), supplemented with either isotopically light or heavy 13C6, 15N2 lysine, and 13C6,15N4 arginine. Cells were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2 with humidity. All cell lines were regularly tested for mycoplasma and verified using short tandem repeat profiling. U2OS, HeLa, HEK293T, and hTERT-RPE1 cells are female. HCT116 cells are male. U2OS PRIMPOLΔ cells were provided by A. Vindigni.

Generation of CLASPIN and PRIMPOL overexpression stable cell lines

GP-293 cells were transfected with virus expression and p-VSVG with polyethylenimine (1 mg/ml, 6 μl/μg DNA) for retroviral packaging. Seventy-two hours after transfection, HCT116 cells or U2OS PRIMPOLΔ cells were infected with viral particles collected from GP-293 supernatants. HCT116- or U2OS PRIMPOLΔ–infected cells were selected with G418 (500 μg/ml). HCT116 CLASPIN overexpression cells were subsequently sorted for the top 10% green fluorescent protein (GFP)–positive cells using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS).

Cell transfections

Plasmid transfections were performed with Fugene 6 (pLEGFP-Flag-NLS, pLEGFP-Flag-NLS-CLASPIN, pLEGFP-Flag-NLS-CLASPIN-3A, pLEGFP-Flag-NLS-PRIMPOL, pLEGFP-Flag-NLS-PRIMPOL S255A, pLEGFP-Flag-NLS-PRIMPOL S255D, or pLEGFP-Flag-NLS-PRIMPOL S255E). siRNA transfections were performed with Dharmafect-1 (Dharmacon).

Plasmids

pcDNA3.1-FLAG-Claspin was obtained from AddGene (catalog no. 12659). Claspin was cloned into pLEGFP-Flag-NLS (pDC1161) to generate pLEGFP-Flag-NLS-CLASPIN (pKPM08). pLEGFP-Flag-NLS-CLASPIN-3A (pKPM11) was generated by Gibson assembly. The PRIMPOL complementary DNA (cDNA) was made by J. Méndez and obtained from A. Vindigni. WT (pKPM13), S255A (pKMP15), S255D (pKPM18), S255E (pKPM19), and 210-260Δ-linker (pKPM31) were cloned into pLEGFP-Flag-NLS. The linker used was a 16–amino acid XTEN linker (SGSETPGTSESATPES) (54, 55). WT-2X PRIMPOL (residues 248 to 262) and S255A-2X PRIMPOL were cloned into pBG101 (6X-HIS, GST) (pKPM22 and pKPM24). pAcGFP-C1-AcGFP-RPA3-P2A-RPA1-P2A-RPA2 was obtained from J. Lukas. All plasmids were confirmed with sequencing.

siRNAs and antibodies

siRNAs were obtained from Qiagen, Ambion, or Dharmacon as specified. The following siRNAs were used: AllStars Negative Control siRNA (Qiagen, catalog no. 1027281), MUS81 (Dharmacon, catalog nos. J-016143-10 and J-016143-11), SLX4 (Ambion, catalog nos. s39052 and s39054), RAD51 (Dharmacon, catalog nos. J-003530-11-0002 and J-003530-12-0002), HLTF (Dharmacon, catalog nos. J-006448-06-0002, J-006448-07-0002, J-006448-08-0002, and J-006448-09-0002), ZRANB3 (Ambion, catalog no. s38488), SMARCAL1 (Dharmacon, catalog no. J-013058-06-0002), and PRIMPOL (Dharmacon, catalog nos. J-016804-17-0002, J-016804-18-0002, J-016804-19-0002, and J-016804-20-0002).

The following antibodies were used: custom PRIMPOL pS255 antibody raised against LERLG(pS)AEQSS peptide (Bethyl Laboratories), pCHK1 S345 (Cell Signaling, catalog no. CS2348), pCHK1 S317 (Cell Signaling, catalog no. CS2344), CHK1 (Santa Cruz, catalog no. sc-8408), FLAG (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog no. F7425), GFP (Abcam, catalog no. ab290), HLTF (Abcam, catalog no. ab183042), MUS81 (Abcam, catalog no. ab14387), PRIMPOL (Custom, Mendez Lab), RAD51 (Abcam, catalog no. ab63801), RPA32 S4/S8 (Bethyl Laboratories, catalog no. A300-245A), RPA32 S33 (Bethyl Laboratories, catalog no. A300-246A), RPA32 (Abcam, catalog no. ab2175), SLX4 (Bethyl Laboratories, catalog no. A302-269A-1), SMARCAL1 (Bethyl Laboratories, catalog no. A301-616A), ZRANB3 (Bethyl Laboratories, catalog no. A303-033A), Goat anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor Plus 488 (Life Technologies, catalog no. A32723), Goat anti-Rat IgG (H+L) Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 594 (Life Technologies, catalog no. A11007), Goat anti-Rat IgG (H+L) Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, HRP Anti-Rat (Thermo Fisher Scientific, catalog no. A10549), IRDye 800CW Goat anti-Mouse IgG Secondary Antibody (Licor, catalog no. 926-32210), and StarBright Blue 700 Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (Bio-Rad, catalog no. 12004161).

Immunoblots

Whole-cell lysates were generated using IGEPAL lysis buffer [50 mM tris (pH 7.4), 200 mM NaCl, 1% Igepal CA-630, 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.5)] containing sodium fluoride (1 mM), sodium vanadate (1 mM), protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF; 1 mM), 25 U of Pierce Universal Nuclease, 1 mM MgCl2, or PhoSTOP phosphatase inhibitors (Roche). Samples were analyzed by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and immunoblotting. The ATR inhibitor VX-970 was used at 1 μM where indicated. Samples were treated with lambda phosphatase (New England Biolabs, catalog no. P0753S; 400 U) for 30 min at 30°C.

Chromatin fractionation

Cells were synchronized overnight with thymidine (2 mM), and fresh medium was placed on the cells in the morning for 2 hours. Cells were counted, harvested, resuspended in buffer A [100 mM NaCl, 300 mM sucrose, 3 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Pipes (pH 6.8), 1 mM EGTA, 0.2% Triton X-100, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 1 mM NaF, 1 mM Na2VO3, and 1× Roche cOmplete Mini Protease Inhibitor], and centrifuged, and the supernatant was collected as the soluble fraction. The pellet was washed once with buffer A, and the nuclei were lysed with buffer B [50 mM tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM NaF, 1 mM Na2VO3, and 1× Roche cOmplete Mini Protease Inhibitor]. The 2× sample buffer was added to each sample and then boiled. Samples were sonicated for 30 cycles (30 s on, 30 s off) or until solubilized in a Diagenode Bioruptor water bath sonicator. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

DNA molecular combing

Cells were labeled with 20 μM CldU (5-chloro-2’-deoxyuridine) (Sigma-Aldrich, C6891) followed by 100 μM IdU (5-Iodo-2’-deoxyuridine) (Sigma-Aldrich, l7125), for the time indicated, with or without 5 μM CD437, 2 μM CHK1 inhibitor (MK-8776), or 10 μM roscovitine or as indicated (Tocris, catalog no. 1549; Selleckchem, catalog no. S2735; Tocris, catalog no. 13-321-0). Approximately 400,000 cells were embedded in 1.5% low-melting agarose plugs in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and digested overnight in 0.1% sarkosyl, proteinase K (2 mg/ml), and 50 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) at 50°C. Plugs were washed in TE (10mM Tris pH=8.0, 1mM EDTA) transferred to 100 mM MES (pH 5.7), melted at 68°C, and digested with 1.5 U of β-agarase overnight at 42°C. DNA was combed onto silanized coverslips (Microsurfaces Inc., Custom) using a Genomic Vision combing apparatus. The DNA was stained with antibodies that recognize IdU and CldU (Abcam, catalog no. ab6326; BD, catalog no. 347580) for 1 hour, washed in PBS, and probed with secondary antibodies for 45 min. Images were obtained using a 40× oil objective (Nikon Eclipse Ti). Analysis of fiber lengths was performed using Nikon Elements software.

DNA molecular combing S1 nuclease assay

Cells were treated as in the DNA molecular combing assay above. After TE washes, residual proteinase K was inactivated with 1 mM PMSF. Plugs were washed once and switched to 1× S1 nuclease buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, catalog no. EN0321). Plugs were switched to fresh S1 nuclease buffer, and S1 nuclease (10 U) was added. Plugs were incubated for 2 hours at 37°C. The reaction was immediately quenched with 50 mM EDTA. Plugs were washed in TE (pH 8.0) once with 50 mM EDTA and then transferred to 100 mM MES (pH 5.7) before continuing the DNA molecular combing protocol.

Neutral comet assay

Trevigen CometAssay ESII system was used to detect DNA DSBs, and the assay was performed as per the manufacturer’s instructions (Trevigen). Tail moments were scored using the open-source Fiji and OpenComet software (56, 57) .

GST purification

GST-tagged proteins from pBG101 vectors were purified from ArcticExpress Escherichia coli (Agilent Technologies). Bacterial pellets were resuspended in NET buffer [25 mM tris (pH 8), 50 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol, 1× Roche cOmplete Mini EDTA-free protease inhibitor, and 1 mM DTT] and sonicated. Triton X-100 was added to a final concentration of 1%, and lysates were incubated on ice for 30 min. Following centrifugation, the cleared supernatant was incubated with glutathione-Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare, catalog no. 17-0756-01) for 2 hours at 4°C. Beads were washed three times with NET buffer containing 1% Triton X-100, and bound proteins were recovered with elution buffer [10 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 15 mM glutathione, 1× Roche cOmplete Mini EDTA-free protease inhibitor, and 1 mM DTT]. Purified proteins were dialyzed into 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, and 1× Roche cOmplete Mini EDTA-free protease inhibitor.

In vitro kinase assay

CHK1 kinase (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog no. 14-346) was incubated with 1 to 1.6 μg of GST-HIS, GST-HIS-2X-PRIMPOL WT (KKLERLGSAEQSSPDKKLERLGSAEQSSPD), or GST-HIS-2X-PRIMPOL-S255A (KKLERLGAAEQSSPDKKLERLGAAEQSSPD) proteins,10 μM adenosine triphosphate (ATP), and 27.8 nM [γ-32P]ATP for 20 min at 30°C with gentle agitation. CHK1 inhibitor (MK-8776; 10 μM) or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added where indicated. Reactions were stopped by addition of 2× SDS sample buffer before SDS-PAGE and detection by Coomassie staining. Substrate phosphorylation was detected by a GE Typhoon phosphorimager.

Mass spectrometry

HEK293T cells labeled with light or heavy amino acids were transfected with pLEGFP-Flag-NLS-PRIMPOL. After 48 hours, cells were synchronized overnight in 2 mM thymidine, released for 2 hours into normal growth medium, and then treated with CD437 and/or CHK1 inhibitor (MK-8776). Replicate label-swapped experiments were performed. Cells cultured with light amino acids were untreated, and heavy-labeled cells were treated with MK-8776 in one replicate, while heavy-labeled cells were untreated and light cells were treated in the second. Cells were counted, and equal numbers of heavy and light cells were mixed and lysed in CHAPS lysis buffer [50 mM tris (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 0.75% CHAPS, 1 mM DTT, 1× Roche cOmplete Mini Protease Inhibitor (catalog no. 4693159001), 1× Roche PhosStop (catalog no. 4906845001), and Pierce Universal Nuclease (catalog no. 88700)] for 1 hour. Immunoprecipitation was performed with FLAG magnetic beads (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog no. M8823). Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Coomassie-stained PRIMPOL bands were excised, diced into 1-mm3 cubes, and destained in 25% MeCN in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate.

Peptide preparation and MS analyses were performed essentially as described previously (58). Bands were reduced in 10 mM DTT at 55°C for 45 min, followed by cysteine carbamidomethylation with 55 mM iodoacetamide at room temperature in the dark for 45 min. Gel pieces were then rinsed with 25% MeCN followed by 50% MeCN in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate and dehydrated for 10 min in 100% MeCN. Solvent was removed, and proteins were digested with trypsin (10 ng/μl) in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate overnight at 37°C. Peptides were extracted with iterative 50-μl volumes of 0.1% formic acid and 5% MeCN, followed by 25% MeCN and 50% MeCN, and dried by SpeedVac centrifugation. Peptides were reconstituted in 0.1% formic acid for analysis by liquid chromatography (LC)–coupled MS/MS. First, an analytical column (360 μm outside diameter × 100 μm inside diameter) was packed with 20 cm of C18 reversed-phase material (Jupiter, 3 μm beads, 300 Å, Phenomenex) directly into a laser-pulled emitter tip. Peptides were loaded onto the capillary reversed-phase analytical column using a Dionex Ultimate 3000 nanoLC and autosampler. Mobile phases were composed of 0.1% formic acid, 99.9% water (solvent A) and 0.1% formic acid, 99.9% acetonitrile (solvent B). Peptides were gradient-eluted at a flow rate of 350 nl/min over 90 min. The gradient consisted of the following: 2 to 40% B for 70 min, 40 to 95% B for 5 min, 95% B for 1 min, 95 to 2% B for 1 min, and 2% B for 10 min (column reequilibration). Eluted peptides were analyzed on a Q Exactive Plus mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), equipped with a nanoelectrospray ionization source. The instrument method consisted of MS1 using an MS AGC target value of 3 × 106, followed by both data-dependent and PRM (parallel reaction monitoring) scan events. The method consisted of 10 MS/MS scans of the most abundant ions detected in the preceding MS scan, followed by PRM scan events for specific mass/charge ratio (m/z) values corresponding to the light and heavy SILAC-labeled PRIMPOL peptide LGSAEQSSPDLSFLVVK. Targeted m/z values corresponded to both unmodified and singly phosphorylated peptide forms. The MS2 AGC target was set to 1 × 105, HCD (high-energy collisional dissociation) collision energy was set to 26 NCE (normalized collisional energy), and peptide match and isotope exclusion were enabled. For identification of peptides, tandem mass spectra were searched with Sequest (Thermo Fisher Scientific) against a human database created from the UniProtKB protein database (www.uniprot.org). Variable modifications included +15.9949 on Met (oxidation), +57.0214 on Cys (carbamidomethylation), and +79.9663 on Ser, Thr, and Tyr (phosphorylation). Search results were assembled using Scaffold 4.3.2 (Proteome Software). Extracted ion chromatograms (XICs) for the PRIMPOL peptide LGSAEQSSPDLSFLVVK were generated using calculated m/z values of the observed (doubly and triply protonated) precursor ions, using a 10 ppm (parts per million) tolerance of the theoretical values. The integrated area under each XIC peak was determined in Xcalibur QualBrowser software, and the percent relative abundance of the phosphorylated peptide was calculated as a percentage of the total area obtained for both unmodified and phosphorylated peptide forms. These percentages were calculated independently for both light- and heavy-labeled SILAC peptide forms in each of the two replicate (label-swapped) experiments.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were completed using Prism 9 (GraphPad). A Mann-Whitney nonparametric test was used when comparing two samples. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was used when comparing more than two groups followed by a Holm-Šídák or Dunn’s post-test. No statistical methods or criteria were used to estimate sample size or to include/exclude samples. Multiple siRNAs, multiple clones, and multiple cell lines were analyzed to confirm that results were not caused by off-target effects or clonal variations. Unless otherwise stated, all experiments were performed at least twice, and representative experiments are shown.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Dewar and C. Lovejoy for helpful discussions and A. Vindigni, J. Méndez, and J. Lukas for providing reagents.

Funding: This work was supported by the NIH (grants R01CA239161 to D.C. and 5T32CA009582 and 1F32GM136096 to K.P.M.M.) and the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (to D.C.).

Author contributions: Conceptualization: D.C., K.P.M.M., and V.T. Methodology: K.P.M.M., D.C., V.T., M.L., and K.L.R. Investigation: K.P.M.M., V.T., R.Z., A.K., M.L., and K.L.R. Data analysis: K.P.M.M. and D.C. Data interpretation: K.P.M.M., D.C., and V.T. Writing—original draft: K.P.M.M. and D.C. Writing—review and editing: K.P.M.M., V.T., A.K., and D.C.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. The MS proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD027918.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S3

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Cortez D., Replication-coupled DNA repair. Mol. Cell 74, 866–876 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sale J. E., Competition, collaboration and coordination—Determining how cells bypass DNA damage. J. Cell Sci. 125, 1633–1643 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gonzalez-Acosta D., Blanco-Romero E., Ubieto-Capella P., Mutreja K., Míguez S., Llanos S., García F., Muñoz J., Blanco L., Lopes M., Méndez J., PrimPol-mediated repriming facilitates replication traverse of DNA interstrand crosslinks. EMBO J. 40, e106355 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mourón S., Rodriguez-Acebes S., Martínez-Jiménez M. I., García-Gómez S., Chocrón S., Blanco L., Méndez J., Repriming of DNA synthesis at stalled replication forks by human PrimPol. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 20, 1383–1389 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bianchi J., Rudd S. G., Jozwiakowski S. K., Bailey L. J., Soura V., Taylor E., Stevanovic I., Green A. J., Stracker T. H., Lindsay H. D., Doherty A. J., PrimPol bypasses UV photoproducts during eukaryotic chromosomal DNA replication. Mol. Cell 52, 566–573 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcia-Gomez S., Reyes A., Martínez-Jiménez M. I., Sandra Chocrón E., Mourón S., Terrados G., Powell C., Salido E., Méndez J., Holt I. J., Blanco L., PrimPol, an archaic primase/polymerase operating in human cells. Mol. Cell 52, 541–553 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wan L., Lou J., Xia Y., Su B., Liu T., Cui J., Sun Y., Lou H., Huang J., hPrimpol1/CCDC111 is a human DNA primase-polymerase required for the maintenance of genome integrity. EMBO Rep. 14, 1104–1112 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piberger A. L., Bowry A., Kelly R. D. W., Walker A. K., González-Acosta D., Bailey L. J., Doherty A. J., Méndez J., Morris J. R., Bryant H. E., Petermann E., PrimPol-dependent single-stranded gap formation mediates homologous recombination at bulky DNA adducts. Nat. Commun. 11, 5863 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Svikovic S., Crisp A., Tan-Wong S. M., Guilliam T. A., Doherty A. J., Proudfoot N. J., Guilbaud G., Sale J. E., R-loop formation during S phase is restricted by PrimPol-mediated repriming. EMBO J. 38, e99793 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schiavone D., Jozwiakowski S. K., Romanello M., Guilbaud G., Guilliam T. A., Bailey L. J., Sale J. E., Doherty A. J., PrimPol is required for replicative tolerance of G quadruplexes in vertebrate cells. Mol. Cell 61, 161–169 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schlacher K., Christ N., Siaud N., Egashira A., Wu H., Jasin M., Double-strand break repair-independent role for BRCA2 in blocking stalled replication fork degradation by MRE11. Cell 145, 529–542 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Couch F. B., Bansbach C. E., Driscoll R., Luzwick J. W., Glick G. G., Bétous R., Carroll C. M., Jung S. Y., Qin J., Cimprich K. A., Cortez D., ATR phosphorylates SMARCAL1 to prevent replication fork collapse. Genes Dev. 27, 1610–1623 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quinet A., Tirman S., Cybulla E., Meroni A., Vindigni A., To skip or not to skip: Choosing repriming to tolerate DNA damage. Mol. Cell 81, 649–658 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berti M., Cortez D., Lopes M., The plasticity of DNA replication forks in response to clinically relevant genotoxic stress. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 633–651 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zellweger R., Dalcher D., Mutreja K., Berti M., Schmid J. A., Herrador R., Vindigni A., Lopes M., Rad51-mediated replication fork reversal is a global response to genotoxic treatments in human cells. J. Cell Biol. 208, 563–579 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mutreja K., Krietsch J., Hess J., Ursich S., Berti M., Roessler F. K., Zellweger R., Patra M., Gasser G., Lopes M., ATR-mediated global fork slowing and reversal assist fork traverse and prevent chromosomal breakage at DNA interstrand cross-links. Cell Rep. 24, 2629–2642.e5 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quinet A., Tirman S., Jackson J., Šviković S., Lemaçon D., Carvajal-Maldonado D., González-Acosta D., Vessoni A. T., Cybulla E., Wood M., Tavis S., Batista L. F. Z., Méndez J., Sale J. E., Vindigni A., PRIMPOL-mediated adaptive response suppresses replication fork reversal in BRCA-deficient cells. Mol. Cell 77, 461–474.e9 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han T., Goralski M., Capota E., Padrick S. B., Kim J., Xie Y., Nijhawan D., The antitumor toxin CD437 is a direct inhibitor of DNA polymerase α. Nat. Chem. Biol. 12, 511–515 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fu Y. V., Yardimci H., Long D. T., Ho T. V., Guainazzi A., Bermudez V. P., Hurwitz J., van Oijen A., Schärer O. D., Walter J. C., Selective bypass of a lagging strand roadblock by the eukaryotic replicative DNA helicase. Cell 146, 931–941 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higuchi K., Katayama T., Iwai S., Hidaka M., Horiuchi T., Maki H., Fate of DNA replication fork encountering a single DNA lesion during oriC plasmid DNA replication in vitro. Genes Cells 8, 437–449 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taylor M. R. G., Yeeles J. T. P., The initial response of a eukaryotic replisome to DNA damage. Mol. Cell 70, 1067–1080.e12 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dungrawala H., Bhat K. P., Meur R. L., Chazin W. J., Ding X., Sharan S. K., Wessel S. R., Sathe A. A., Zhao R., Cortez D., RADX promotes genome stability and modulates chemosensitivity by regulating RAD51 at replication forks. Mol. Cell 67, 374–386.e5 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanada K., Budzowska M., Davies S. L., van Drunen E., Onizawa H., Beverloo H. B., Maas A., Essers J., Hickson I. D., Kanaar R., The structure-specific endonuclease Mus81 contributes to replication restart by generating double-strand DNA breaks. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 1096–1104 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ercilla A., Benada J., Amitash S., Zonderland G., Baldi G., Somyajit K., Ochs F., Costanzo V., Lukas J., Toledo L., Physiological tolerance to ssDNA enables strand uncoupling during DNA replication. Cell Rep. 30, 2416–2429.e7 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vujanovic M., Krietsch J., Raso M. C., Terraneo N., Zellweger R., Schmid J. A., Taglialatela A., Huang J.-W., Holland C. L., Zwicky K., Herrador R., Jacobs H., Cortez D., Ciccia A., Penengo L., Lopes M., Replication fork slowing and reversal upon DNA damage require PCNA polyubiquitination and ZRANB3 DNA translocase activity. Mol. Cell 67, 882–890.e5 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Betous R., Couch F. B., Mason A. C., Eichman B. F., Manosas M., Cortez D., Substrate-selective repair and restart of replication forks by DNA translocases. Cell Rep. 3, 1958–1969 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chavez D. A., Greer B. H., Eichman B. F., The HIRAN domain of helicase-like transcription factor positions the DNA translocase motor to drive efficient DNA fork regression. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 8484–8494 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumagai A., Dunphy W. G., Claspin, a novel protein required for the activation of Chk1 during a DNA replication checkpoint response in Xenopus egg extracts. Mol. Cell 6, 839–849 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petermann E., Helleday T., Caldecott K. W., Claspin promotes normal replication fork rates in human cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 2373–2378 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scorah J., McGowan C. H., Claspin and Chk1 regulate replication fork stability by different mechanisms. Cell Cycle 8, 1036–1043 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bando M., Katou Y., Komata M., Tanaka H., Itoh T., Sutani T., Shirahige K., Csm3, Tof1, and Mrc1 form a heterotrimeric mediator complex that associates with DNA replication forks. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 34355–34365 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bianco J. N., Bergoglio V., Lin Y.-L., Pillaire M.-J., Schmitz A.-L., Gilhodes J., Lusque A., Mazières J., Lacroix-Triki M., Roumeliotis T. I., Choudhary J., Moreaux J., Hoffmann J.-S., Tourrière H., Pasero P., Overexpression of Claspin and Timeless protects cancer cells from replication stress in a checkpoint-independent manner. Nat. Commun. 10, 910 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gambus A., Jones R. C., Sanchez-Diaz A., Kanemaki M., van Deursen F., Edmondson R. D., Labib K., GINS maintains association of Cdc45 with MCM in replisome progression complexes at eukaryotic DNA replication forks. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 358–366 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumagai A., Dunphy W. G., Repeated phosphopeptide motifs in Claspin mediate the regulated binding of Chk1. Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 161–165 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chini C. C. S., Chen J., Repeated phosphopeptide motifs in human Claspin are phosphorylated by Chk1 and mediate Claspin function. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 33276–33282 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clarke C. A. L., Clarke P. R., DNA-dependent phosphorylation of Chk1 and Claspin in a human cell-free system. Biochem. J. 388, 705–712 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang C. C., Kato H., Shindo M., Masai H., Cdc7 activates replication checkpoint by phosphorylating the Chk1-binding domain of Claspin in human cells. eLife 8, e50796 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moiseeva T. N., Yin Y., Calderon M. J., Qian C., Schamus-Haynes S., Sugitani N., Osmanbeyoglu H. U., Rothenberg E., Watkins S. C., Bakkenist C. J., An ATR and CHK1 kinase signaling mechanism that limits origin firing during unperturbed DNA replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 13374–13383 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bai G., Kermi C., Stoy H., Schiltz C. J., Bacal J., Zaino A. M., Kyle Hadden M., Eichman B. F., Lopes M., Cimprich K. A., HLTF promotes fork reversal, limiting replication stress resistance and preventing multiple mechanisms of unrestrained DNA synthesis. Mol. Cell 78, 1237–1251.e7 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blasius M., Forment J. V., Thakkar N., Wagner S. A., Choudhary C., Jackson S. P., A phospho-proteomic screen identifies substrates of the checkpoint kinase Chk1. Genome Biol. 12, R78 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rechkoblit O., Gupta Y. K., Malik R., Rajashankar K. R., Johnson R. E., Prakash L., Prakash S., Aggarwal A. K., Structure and mechanism of human PrimPol, a DNA polymerase with primase activity. Sci. Adv. 2, e1601317 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hornbeck P. V., Zhang B., Murray B., Kornhauser J. M., Latham V., Skrzypek E., PhosphoSitePlus, 2014: Mutations, PTMs and recalibrations. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, D512–D520 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bailey L. J., Teague R., Kolesar P., Bainbridge L. J., Lindsay H. D., Doherty A. J., PLK1 regulates the PrimPol damage tolerance pathway during the cell cycle. Sci. Adv. 7, eabh1004 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kobayashi K., Guilliam T. A., Tsuda M., Yamamoto J., Bailey L. J., Iwai S., Takeda S., Doherty A. J., Hirota K., Repriming by PrimPol is critical for DNA replication restart downstream of lesions and chain-terminating nucleosides. Cell Cycle 15, 1997–2008 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martinez-Jimenez M. I., Lahera A., Blanco L., Human PrimPol activity is enhanced by RPA. Sci. Rep. 7, 783 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guilliam T. A., Brissett N. C., Ehlinger A., Keen B. A., Kolesar P., Taylor E. M., Bailey L. J., Lindsay H. D., Chazin W. J., Doherty A. J., Molecular basis for PrimPol recruitment to replication forks by RPA. Nat. Commun. 8, 15222 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yan Y., Xu Z., Huang J., Guo G., Gao M., Kim W., Zeng X., Kloeber J. A., Zhu Q., Zhao F., Luo K., Lou Z., The deubiquitinase USP36 regulates DNA replication stress and confers therapeutic resistance through PrimPol stabilization. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 12711–12726 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kasho K., Stojkovič G., Velázquez-Ruiz C., Martínez-Jiménez M. I., Doimo M., Laurent T., Berner A., Pérez-Rivera A. E., Jenninger L., Blanco L., Wanrooij S., A unique arginine cluster in PolDIP2 enhances nucleotide binding and DNA synthesis by PrimPol. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, 2179–2191 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kile A. C., Chavez D. A., Bacal J., Eldirany S., Korzhnev D. M., Bezsonova I., Eichman B. F., Cimprich K. A., HLTF’s ancient HIRAN domain binds 3′ DNA ends to drive replication fork reversal. Mol. Cell 58, 1090–1100 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taylor M. R. G., Yeeles J. T. P., Dynamics of replication fork progression following helicase-polymerase uncoupling in eukaryotes. J. Mol. Biol. 431, 2040–2049 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Elvers I., Hagenkort A., Johansson F., Djureinovic T., Lagerqvist A., Schultz N., Stoimenov I., Erixon K., Helleday T., CHK1 activity is required for continuous replication fork elongation but not stabilization of post-replicative gaps after UV irradiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 8440–8448 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bailey L. J., Bianchi J., Doherty A. J., PrimPol is required for the maintenance of efficient nuclear and mitochondrial DNA replication in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, 4026–4038 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rodier G., Kirsh O., Baraibar M., Houlès T., Lacroix M., Delpech H., Hatchi E., Arnould S., Severac D., Dubois E., Caramel J., Julien E., Friguet B., le Cam L., Sardet C., The transcription factor E4F1 coordinates CHK1-dependent checkpoint and mitochondrial functions. Cell Rep. 11, 220–233 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schellenberger V., Wang C.-W., Geething N. C., Spink B. J., Campbell A., To W., Scholle M. D., Yin Y., Yao Y., Bogin O., Cleland J. L., Silverman J., Stemmer W. P. C., A recombinant polypeptide extends the in vivo half-life of peptides and proteins in a tunable manner. Nat. Biotechnol. 27, 1186–1190 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guilinger J. P., Thompson D. B., Liu D. R., Fusion of catalytically inactive Cas9 to FokI nuclease improves the specificity of genome modification. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 577–582 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gyori B. M., Venkatachalam G., Thiagarajan P. S., Hsu D., Clement M. V., OpenComet: An automated tool for comet assay image analysis. Redox Biol. 2, 457–465 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schindelin J., Arganda-Carreras I., Frise E., Kaynig V., Longair M., Pietzsch T., Preibisch S., Rueden C., Saalfeld S., Schmid B., Tinevez J.-Y., White D. J., Hartenstein V., Eliceiri K., Tomancak P., Cardona A., Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang Q., Higginbotham J. N., Jeppesen D. K., Yang Y.-P., Li W., McKinley E. T., Graves-Deal R., Ping J., Britain C. M., Dorsett K. A., Hartman C. L., Ford D. A., Allen R. M., Vickers K. C., Liu Q., Franklin J. L., Bellis S. L., Coffey R. J., Transfer of functional cargo in exomeres. Cell Rep. 27, 940–954.e6 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figs. S1 to S3