Abstract

A series of 12 Staphylococcus aureus strains of various genetic backgrounds, methicillin resistance levels, and autolytic activities were subjected to selection for the glycopeptide-intermediate S. aureus (GISA) susceptibility phenotype on increasing concentrations of vancomycin. Six strains acquired the phenotype rapidly, two did so slowly, and four failed to do so. The vancomycin MICs for the GISA strains ranged from 4 to 16 μg/ml, were stable to 20 nonselective passages, and expressed resistance homogeneously. Neither ease of acquisition of the GISA phenotype nor the MIC attained correlated with methicillin resistance hetero- versus homogeneity or autolytic deficiency or sufficiency. Oxacillin MICs were generally unchanged between parent and GISA strains, although the mec members of both isogenic methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant pairs acquired the GISA phenotype more rapidly and to higher MICs than did their susceptible counterparts. Transmission electron microscopy revealed that the GISA strains appeared normal in the absence of vancomycin but had thickened and diffuse cell walls when grown with vancomycin at one-half the MIC. Common features among GISAs were reduced doubling times, decreased lysostaphin susceptibilities, and reduced whole-cell and zymographic autolytic activities in the absence of vancomycin. This, with surface hydrophobicity differences, indicated that even in the absence of vancomycin the GISA cell walls differed from those of the parents. Autolytic activities were further reduced by the inclusion of vancomycin in whole-cell and zymographic studies. The six least vancomycin-susceptible GISA strains exhibited an increased capacity to remove vancomycin from the medium versus their parent lines. This study suggests that while some elements of the GISA phenotype are strain specific, many are common to the phenotype although their expression is influenced by genetic background. GISA strains with similar glycopeptide MICs may express individual components of the phenotype to different extents.

Staphylococcus aureus is one of the most common causes of both nosocomial and community-acquired infections, which had high rates of mortality in the preantibiotic era (35). In addition to its virulence, S. aureus has a proclivity for the acquisition of resistance elements to a wide range of antibiotic classes. The glycopeptide antibiotic vancomycin is often the sole remaining antibiotic effective against S. aureus infections (24). As such, the acquisition of glycopeptide resistance by S. aureus has been anticipated with apprehension (4).

Clinical isolation and laboratory selection of low-level glycopeptide resistance in coagulase-negative staphylococci, primarily S. epidermidis and S. haemolyticus, has been recognized since the 1980s (29). In 1990 Kaatz et al. (16) reported the in vivo selection of low-level resistance to teicoplanin, a glycopeptide not currently approved for clinical use in the United States, in methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA). Subsequently, Daum et al. (6) propagated a clinically isolated methicillin-sensitive S. aureus on incrementally increasing concentrations of vancomycin to produce strain 523k, for which the MICs of vancomycin and teicoplanin are 8 μg/ml. Strain 523k has a thickened cell wall and increased cell diameter and a reduced susceptibility to lysostaphin. This isolate exhibits intermediate resistance by National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) guidelines (20) and has been termed a glycopeptide-intermediate S. aureus (GISA).

The first reported clinical GISA strain, described by Hiramatsu in Japan in 1997, was from a surgical-site nosocomial infection in a 4-month-old that had received 41 days of vancomycin treatment (15). For this isolate, Mu50, the MIC of vancomycin was 8 μg/ml, and it had a thickened cell wall and increased autolytic activities, notably in the atl gene products as visualized on autolysin zymograms (11). Later, the same researchers reported the isolation of the second clinical GISA strain, Mu3, for which the vancomycin MIC was 3 μg/ml (14). Mu3 expresses vancomycin resistance heterogeneously and plating on 8 μg of vancomycin per ml yields clones with resistances identical to that of the homogeneous Mu50. Mu50 and Mu3 are both homogeneous methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), for which the oxacillin MICs were 128 μg/ml (33). In 1997 two clinically isolated GISA strains were reported in the United States, an MRSA from Michigan and an MSSA from New Jersey, both from patients that had received prolonged vancomycin therapy; for both strains the vancomycin MICs were 8 μg/ml (5). The Michigan isolate expresses vancomycin resistance homogeneously, while the New Jersey isolate does so heterogeneously (E. Hershberger, J. R. Aeschlimann, T. Moldovan, and M. J. Ryback, Abstr. 98th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol 1998, abstr. E-173a, 1998).

Sieradzki and Tomasz (31) isolated GISA VM from MRSA COL in vitro by passage selection. COL is a homogeneous MRSA strain for which the methicillin MIC is 800 μg/ml and the vancomycin MIC is 1.5 μg/ml, while for VM the MICs of methicillin and vancomycin are 1.5 and 100 μg/ml, respectively. Relative to COL, VM has a decreased susceptibility to lysostaphin and an increased capacity to remove vancomycin from the growth medium. VM also has an increased doubling time, decreased autolytic activities, and an enlarged and distorted cell wall morphology, but only when vancomycin is included in the growth medium. Only minor changes are apparent on autolysin zymograms under these conditions. Recently, the GISA mutant TNM with similar properties was isolated from COL with passage selection on teicoplanin (32).

The mechanism of high-level vancomycin resistance in enterococci is well understood and is mediated by the van genes which result in the generation of d-alanyl-d-lactate muropeptide stem termini in peptidoglycan precursor molecules, for which vancomycin has a binding affinity that is several orders of magnitude lower than that for the normal d-alanyl-d-alanine termini (13). While plasmid-encoded van genes have been shown to function in S. aureus following in vitro transfer (22), van genes are absent from all clinically isolated and laboratory-selected GISA strains examined so far (34). It appears that GISA resistance is intrinsic, deriving from the accumulation of mutations and not due to genetic exchange.

The GISA mutants described thus far have common features that include thickened cell walls and altered autolytic activities, but these traits can be expressed differently between strains. Sieradzki and Tomasz (31) have suggested that the resistance mechanism is based on the overproduction and accumulation (in part through reduced autolytic activity) of cell wall material, and thus free d-alanyl-d-alanine binding sites, sequestering vancomycin distant from its target at the plasma membrane. Hiramatsu proposes a “false-target hypothesis,” which is similar to the Tomasz hypothesis in that overproduced free binding sites shield the critical targets of glycopeptides. Hiramatsu suggests that the increased autolytic activities observed in Mu50 and Mu3 reflect an increased cell wall turnover mechanism which excises material to which glycopeptides are bound, replacing it with new free d-alanyl-d-alanine binding sites (13). There is some evidence to suggest that the production of small quantities of abnormal peptidoglycan precursors and interpeptide bridges are involved in the resistance mechanism (2).

Only a few GISA strains are well characterized, and it is difficult to distinguish common mechanistic elements from traits that are due to strain-specific characteristics or are related to the conditions under which the mutants are selected. Analysis of clinical isolates is often further impeded by the lack of glycopeptide-sensitive parent strains (GSSA) for comparison purposes and an absence of a history of genetic and biochemical characterization. Additionally, reports of the effects of the acquisition of the GISA phenotype on methicillin resistance expression in MRSA differs greatly between GISA strains (31, 33).

We have subjected a panel of 12 well-characterized laboratory S. aureus strains to passage selection with vancomycin. These strains included isogenic methicillin-susceptible and -resistant pairs, homogeneously and heterogeneously resistant MRSA strains, strains with reduced autolytic activities, and two lines of a single strain that were propagated separately in different laboratories for nearly a decade. The intent of this study is to identify those features of the GISA phenotype that are common to the resistance mechanism versus those that are strain specific, to examine the relationship between methicillin resistance expression and the acquisition and expression of the GISA phenotype, and to investigate the association between autolysis and the GISA resistance mechanism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

All strains used in this study and their relevant characteristics are described in Table 1. The strains were stored at −20°C in 30% (vol/vol) glycerol and periodically streaked out onto tryptic soy agar (TSA; Difco) to provide working plates that were stored at 4°C. Lyt-1 and SH108 were grown in the presence of 20 μg of erythromycin per ml. Tryptic soy broth (TSB; Difco) was used for liquid cultures unless otherwise stated; these were grown at 37°C with shaking at 250 rpm. Cultures on TSA were grown at 37°C.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this studya

| Strain | Parent strain background | Ease of acquisition of the GISA phenotype | Source or Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| BB255 | Mcs, isogenic to BB270 | 10 | |

| BB255V3 | Rapid: two cycles in 2 wk | This study | |

| BB270 | Mcr (he) | 10 | |

| BB270V5 | Rapid: three cycles in 1 wk | This study | |

| BB270V15 | Rapid: five cycles in 5 wk | This study | |

| SC4 | Mcs, isogenic to SC4mecC5 | Failed to acquire phenotype | 10 |

| SC4mecC5 | Mcr (he) | Failed to acquire phenotype | 10 |

| 13136p−m− | Mcs, isogenic to 13136p−m+ | 3 | |

| 13136p−m−V5 | Rapid: two cycles in 1 wk | This study | |

| 13136p−m+ | Mcr (he) | 3 | |

| 13136p−m+V5 | Rapid: two cycles in 1 wk | This study | |

| 13136p−m+V20 | Rapid: five cycles in 5 wk | This study | |

| SH108 | Mcs, autolysis-deficient (atl mutant) | 9 | |

| SH108V5 | Rapid: four cycles in 4 wk | This study | |

| RN450 | Mcs, 8325-4, isogenic to Lyt-1 | Failed to acquire phenotype | 18 |

| Lyt-1 | Mcs, autolysis deficient | Failed to acquire phenotype | 18 |

| BB399 | Mcr (ho), DU4916 | 10 | |

| BB399V5 | Slow: five cycles in 5 wk | This study | |

| BB399V12 | Slow: seven cycles in 8 wk | This study | |

| BB568 | Mcr (ho), COL | 10 | |

| BB568V5 | Rapid: five cycles in 5 wk | This study | |

| BB568V15 | Rapid: five cycles in 5 wk | This study | |

| COL | Mcr (ho) | 28 | |

| COLV5 | Slow: five cycles in 7 wk | This study | |

| COLV10 | Slow: seven cycles in 11 wk | This study |

Abbreviations: Mcs and Mcr, methicillin susceptible and resistant; he and ho, hetero- and homogeneous; VX, concentration of vancomycin (in micrograms per milliliter) on which strains were maintained; cycle, growth in liquid medium and then growth on solid medium containing the same concentration of vancomycin.

Selection of the GISA phenotype.

Strains were grown in 4 ml of TSB in the presence of vancomycin at 1 to 2 μg/ml or more above the MIC for a given strain at 37°C with shaking (250 rpm) until turbid growth was observed (1 to 7 days). The cultures were diluted by factors of 10−1, 10−3, 10−5, and 10−7, and the dilutions were plated each in four 10-μl droplets and one 50-μl aliquot (spread with a glass rod) on TSA containing the same concentration of vancomycin as the broth cultures. Plates were incubated at 37°C until colonies formed (1 to 7 days). Mutants were picked from dilutions at which colony counts yielded identical calculations of CFU per milliliter with both the 10- and 50-μl platings, and the cycle of broth and then agar growth was repeated with a higher concentration of vancomycin.

MIC determinations.

MICs of oxacillin were determined according to NCCLS guidelines with 96-well microtiter plates containing twofold serial dilutions of oxacillin in TSB into which overnight cultures were added to a final concentration of 5 × 105 CFU/ml (21). The plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h, and the lowest concentration of oxacillin at which there was no visible growth was considered the MIC. MICs of glycopeptides were performed in a similar fashion, except with 0, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, and 16 μg of vancomycin and 0, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 16, and 20 μg of teicoplanin per ml in place of a standard serial dilution. Glycopeptide MICs were read at 24 and 48 h, and the 48-h results are presented in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Relevant antibiotic susceptibilities of parent and GISA strainsa

| Strain | MIC (μg/ml)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MICOX | MICTC | MICVM | MBCVM | |

| BB255 | 0.375 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 8.0 |

| BB255V3 | 0.375 | 6.0 | 4.0 | 8.0 |

| BB270 | 100.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 8.0 |

| BB270V5 | 100.0 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 32.0 |

| BB270V15 | 100.0 | 16.0 | 12.0 | 64.0 |

| SC4 | 0.75 | ND | 1.0 | ND |

| SC4mecC5 | 25.0 | ND | 1.0 | ND |

| 13136p−m− | 0.75 | ND | 1.0 | ND |

| 13136p−m−V5 | 3.0 | 6.0 | 4.0 | 8.0 |

| 13136p−m+ | 50.0 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 8.0 |

| 13136p−m+V5 | 100.0 | 6.0 | 8.0 | 16.0 |

| 13136p−m+V20 | 100.0 | 20.0 | 16.0 | 64.0 |

| SH108 | 0.375 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 |

| SH108V5 | 0.375 | 10.0 | 6.0 | 16.0 |

| RN450 | 0.375 | ND | 1.0 | ND |

| Lyt-1 | 0.375 | ND | 2.0 | ND |

| BB399 | 400.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 8.0 |

| BB399V5 | 400.0 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 16.0 |

| BB399V12 | 400.0 | 16.0 | 12.0 | 32.0 |

| BB568 | 400.0 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 8.0 |

| BB568V5 | 400.0 | 12.0 | 8.0 | 32.0 |

| BB568V15 | 400.0 | 20.0 | 12.0 | 32.0 |

| COL | 400.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 8.0 |

| COLV5 | 800.0 | 8.0 | 6.0 | 8.0 |

| COLV10 | 800.0 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 32.0 |

Abbreviations: OX, oxacillin; TC, teicoplanin; VM, vancomycin; ND, not determined.

MBC determinations.

The procedure for determining the MBCs was derived from that of Debbia et al. (7). Each strain required five test tubes containing 5 × 105 CFU in 1 ml of TSB and vancomycin concentrations covering five steps in a twofold serial dilution. These were incubated stationary for 24 h at 37°C, after which 10 μl from each tube without visible growth was plated out. Colonies were counted after 24 h at 37°C and the MBC was considered the concentration of vancomycin giving ≤5 colonies per droplet (≤0.1% survival).

Population analyses.

Population analyses were performed as described for GISA phenotype selection with four 10-μl droplets per dilution, for which the CFU values were averaged. TSB cultures were diluted to a concentration of 109 CFU/ml, and subsequent dilutions were plated on increasing concentrations of oxacillin or vancomycin. Colonies were counted at from 24 to 96 h.

Electron microscopy.

Samples were prepared for examination by transmission electron microscopy as described by Mani et al. (17). Mid-exponential-phase cells were harvested, fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde, and postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide and then 1% aqueous uranyl acetate. Following dehydration, the samples were embedded in Epon 812, and thin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate.

Hydrophobicity assessments.

Cell hydrophobicity was assayed as described by Reifsteck et al. (26), with slight modification. Briefly, strains were grown for 18 to 24 h in 25 ml of TSB in 50-ml Erlenmeyer flasks at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm, and 20 μg of erythromycin per ml was included with the SH108 strains. GISA strains COLV10 and SH108V5 were assayed after growth in the presence or absence of 2 and 3 μg vancomycin per ml, respectively. Cells were harvested by centrifugation (10,800 × g, 10 min, 4°C), washed twice with cold distilled water, and resuspended in phosphate-urea-magnesium buffer to an optical density at 500 nm (OD500) of 0.5. This suspension was distributed in 4.8-ml aliquots into 15-by-150-mm test tubes to which 0.0 to 0.8 ml of hydrocarbon (n-hexadecane or p-xylene) was added. After vortexing for 30 s, the samples were left undisturbed at room temperature for 20 min before the OD500 of the lower (aqueous) layer was determined.

Lysostaphin susceptibility assays.

The assay was modified from the procedure of Daum et al. (6). From an overnight culture, 5 × 107 CFU was microfuged (16,000 × g, 8 min), the cells were washed once in 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and the cells were then resuspended in 455 μl of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA; pH 8.0). A colony count was performed as described above with 10-μl droplets except that 10−2, 10−4, and 10−6 dilutions in PBS were plated. DNase I (Sigma) was added to a concentration of 20 μg/ml, and lysostaphin (Sigma) was added to a concentration of 16 μg/ml. Then the tubes were vortexed and incubated stationary for 30 min at 37°C. The tubes were then placed on ice, and the colony counts were repeated. Colony counts after 24 and 48 h of incubation at 37°C were compared as an efficiency of plating (EOP) to rate strain susceptibilities.

Whole-cell autolysis assays.

Assays were performed as previously described (10). Cultures in 100 ml of PYK, started with a 2% inoculum from a 5 ml of PYK overnight culture, were grown to an OD600 of 0.7 at 37°C with shaking at 250 rpm. After one wash with cold water (8,200 × g, 4°C, 15 min), cells were resuspended in 100 ml of 0.05 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.2) containing 0.05% Triton X-100. An initial OD600 reading was taken, the flask was incubated at 37°C with shaking (250 rpm), and subsequent readings were taken every 30 min for 4.5 h.

Zymography.

Zymographic analyses were performed as described elsewhere (18). An overnight culture was used to inoculate 100 ml of PYK medium and allowed to grow to an OD600 of 0.7 at 37°C with shaking at 250 rpm. GISA strains were grown with or without vancomycin present at a concentration of one-half the MIC. The cells were centrifuged (8,200 × g, 4°C, 10 min), washed once with 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2), and resuspended in 200 μl of the buffer. Autolysins were extracted by six freeze-thaw cycles (−80°C for 1 h and then 37°C for 10 min), yielding equivalent concentrations of protein from parent and GISA strains. The suspension was microfuged (16,000 × g, 10 min), and 15 μl of the supernatant was heated in a boiling water bath with an equal volume of gel loading buffer for 3 min. For electrophoresis, 1.7 μg of extracted protein was loaded into each well of a 15% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel that included 0.2% (wt/vol) crude S. aureus cell walls, which was then incubated at 37°C in renaturation buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0] and 1% Triton X-100). The gel was stained with 1% methylene blue in 0.01% KOH and destained in deionized water. Autolytic bands were observed as clearings in the gel.

Vancomycin absorption bioassays.

Assessment of vancomycin removal from the medium by whole cells was derived from the methodology of Sieradzki and Tomasz (31). Overnight culture diluted to 108 CFU/ml and 64 μg of vancomycin per ml in a total volume of 2 ml of TSB was vortexed and incubated stationary for 24 h at 37°C. From this, 1.5 ml was microfuged (16,000 × g, 8 min), and the supernatant filter sterilized into a fresh, sterile microfuge tube by using a 3-mm cellulose-acetate (0.45-μm-pore-size) syringe filter. These filtrates were used as presumptive 64-μg/ml vancomycin stocks for determining MICs as described above with the control strain RN450. Apparent differences between the results of these MICs and controls provided rough estimates for the amount of vancomycin absorbed by the cells during incubation.

RESULTS

Selection of GISA mutants.

Table 1 displays the parent strains and their GISA derivatives. The number associated with GISA strains, such as V5, refers to the vancomycin concentration at which they were maintained and not to the MIC values. The GISA phenotype was acquired to various levels of resistance by 8 of the 12 parent lines through stepwise passage selection on increasing concentrations of vancomycin. Two pairs of isogenic strains, (i) SC4 and MRSA SC4mecC5 and (ii) RN450 and autolysis-deficient Lyt-1, did not acquire the GISA phenotype. Of those strains that did, some were able to acquire it more rapidly than others. Ease of acquisition is presented in liquid-growth–solid-growth cycles, and attention should be paid to the vancomycin MICs attained (Table 2) to appreciate the difference between strains that rapidly and slowly acquire the phenotype. Two isogenic MSSA-MRSA pairs, BB255 and BB270, and 13136p−m− and 13136p−m+, acquired the GISA phenotype, and in both cases higher vancomycin MICs were required for the MRSA member than for its MSSA counterpart (Table 2). However, one of the two COL lines maintained in a different laboratory (BB568) rapidly acquired the phenotype and to a higher MIC than did the slowly acquiring strain COL. The highest vancomycin resistance level shown for a given strain indicates a point beyond which the vancomycin MIC could not be increased after a reasonable attempt to do so.

Susceptibility characteristics of GISA strains.

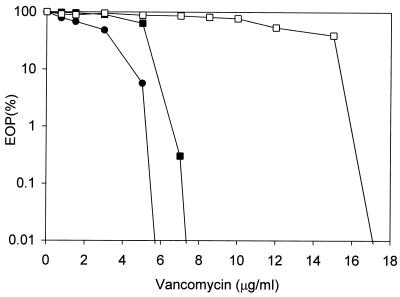

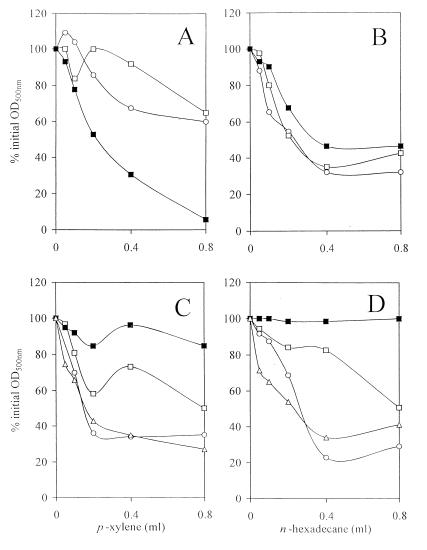

It can be seen in Table 2 that the MICs of vancomycin for the GISA strains ranged from 4 to 16 μg/ml. The resistance was generally stable after plating on nonselective medium 20 times, which typically produced a 2-μg/ml reduction in the vancomycin MICs (data not presented). The strains concomitantly acquired resistance to another glycopeptide, teicoplanin, and its MICs were generally 2 to 4 μg/ml higher than those of vancomycin. MBCs of vancomycin were two to five times greater than its MICs. The oxacillin MICs of the GISA strains typically remained unchanged from those of the parents, although several expressed slight increases. There seemed to be no correlation between homogeneity and heterogeneity of methicillin resistance in MRSA parents, or of the presence of autolysis deficiency mutations (SH108 and Lyt-1) or naturally low autolytic activity (BB399), and the acquisition or expression of the GISA phenotype. Population analyses with vancomycin revealed uniformly homogeneous expression in strains for which the vancomycin MICs were both higher and lower. Figure 1 shows the population analysis profiles of the 13136 series GISA strains, which were representative of the strains used in this study. For 13136p−m+V20 the vancomycin MIC was clearly higher than for 13136p−m+V5, which was in turn higher than that for MSSA 13136p−m−V5; but none of these strains had highly resistant subpopulations characteristic of heterogeneity.

FIG. 1.

Population analysis profiles of the 13136 series GISA strains on vancomycin. Symbols: ●, MSSA derivative 13136p−m−V5; ■, MRSA derivatives 13136p−m+V5; □, 13136p−m+V20. Overnight cultures were standardized to 109 CFU/ml, diluted, and plated on arithmetically increasing concentrations of vancomycin as described in Materials and Methods.

GISA growth rates.

GISA strains grew more slowly than their parents, as reflected by the doubling times (Table 3). Doubling times increased as progressively higher vancomycin MICs were selected. These growth rate decreases did not correlate with vancomycin MIC increases in a linear fashion. Some strains, such as BB399, showed similar increases in doubling times between parent and moderately resistant GISA strains (BB399V5) and between these and more highly resistant GISA strains (BB399V12). In the 13136p−m+ series, a large increase in doubling time occurred between the parent and 13136p−m+V5, while relatively little occurred during the selection of 13136p−m+V20 from 13136p−m+V5. The two COL lines, BB568 and COL, had nearly identical growth rate reduction patterns.

TABLE 3.

Doubling times, whole-cell autolytic activities, lysostaphin susceptibilities, and capacities to remove vancomycin from the medium of parent and GISA strains

| Strain | Doubling time (h) | Autolytic activitya (%) | Lysostaphin susceptibilityb (EOP [%]) | Vancomycin absorptionc (μg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BB255 | 0.76 | 11 | ||

| BB255V3 | 0.78 | 18 | ||

| BB270 | 0.88 | 11 | 0.028 | 1 |

| BB270V5 | 1.03 | 45 | ||

| BB270V15 | 1.19 | 65 | 2.15 | 3 |

| 13136p−m− | 0.65 | 14 | 0.0028 | |

| 13136p−m−V5 | 0.77 | 22 | 8.86 | |

| 13136p−m+ | 0.94 | 16 | 0.005 | 1 |

| 13136p−m+V5 | 1.34 | 60 | ||

| 13136p−m+V20 | 1.38 | 67 | 74.0 | 7 |

| SH108 | 0.68 | 59 | 7.9 | 1 |

| SH108V5 | 0.90 | 79 | 2.3 | 5 |

| BB399 | 0.65 | 29 | 2.52 | 2 |

| BB399V5 | 0.80 | 27 | ||

| BB399V12 | 0.96 | 78 | 0.49 | 5 |

| BB568 | 0.75 | 15 | 0.41 | 2 |

| BB568V5 | 0.83 | 20 | ||

| BB568V15 | 0.97 | 20 | 10.96 | 8 |

| COL | 0.75 | 23 | 0.32 | 2 |

| COLV5 | 0.84 | 21 | ||

| COLV10 | 0.96 | 28 | 7.72 | 5 |

Expressed as percent remaining OD600 at 4.5 h after resuspension of culture in assay buffer.

Expressed as EOP (%) remaining after treatment with lysostaphin.

Vancomycin removed from the medium by 108 CFU/ml after a 24-h incubation.

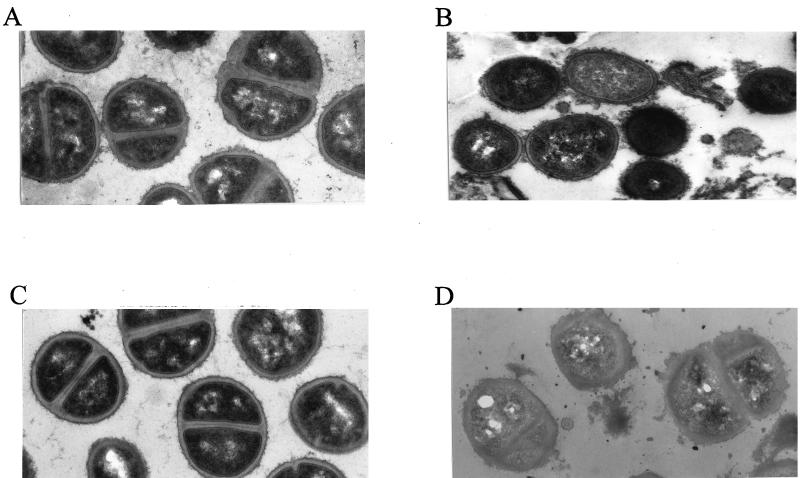

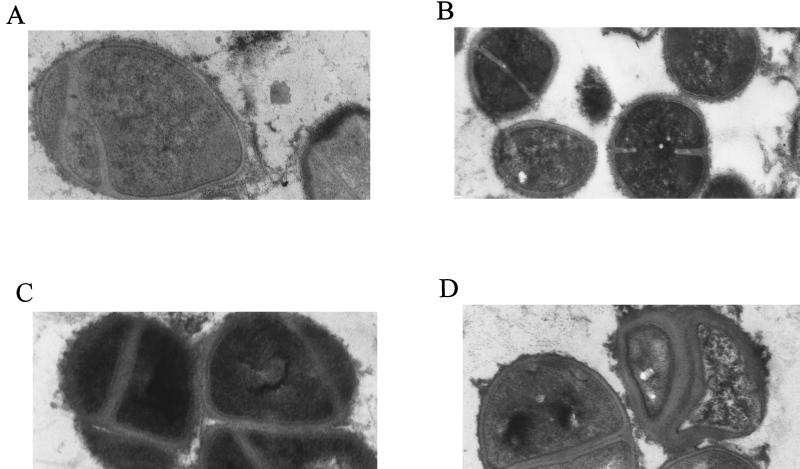

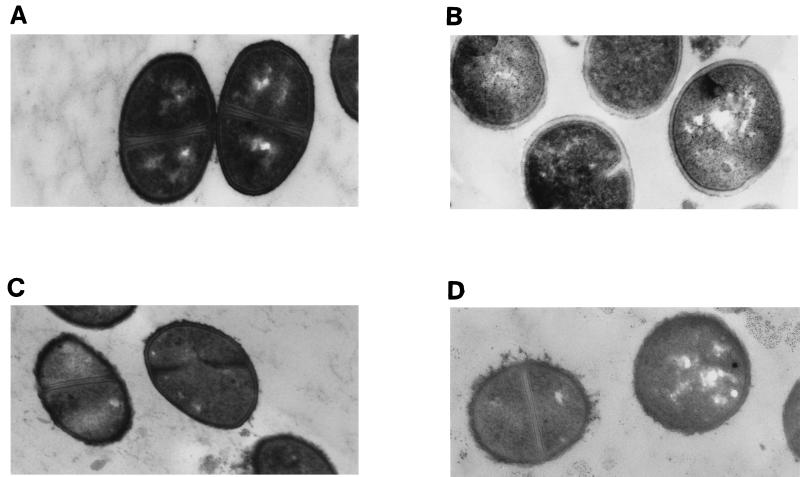

Cell wall morphologies.

Electron micrographs of parent strain 13136p−m+ and GISA derivative 13136p−m+V20 grown in the presence or absence of one-half the MICs of vancomycin for each strain (8 and 0.75 μg/ml, respectively) are shown in Fig. 2. Without vancomycin present, the GISA and parent strains appeared to be identical with respect to cell diameter, cell wall thickness, and cell wall morphology. With vancomycin present, the cell wall of the mutant became thickened and diffuse, with an uneven (or roughened) surface. The cell wall surface of parent 13136p−m+ also became somewhat diffuse when grown in the presence of vancomycin. The cell wall surface of atl mutant strain SH108 was rough in comparison to autolysis-sufficient S. aureus, such as strain 13136p−m+, as was previously reported (9), and appeared equally rough when grown in the presence of vancomycin at one-half its MIC (1.0 μg/ml). GISA SH108V5 had a cell wall surface that appeared to be more uneven than that of the parent when grown in the absence of vancomycin due to the presence of additional diffuse material (Fig. 3). Growth in the presence of vancomycin at one-half the MIC (3 μg/ml) exacerbated the uneven morphology of the surface of SH108V5, but only some cells exhibited thickened cell walls to the extent seen in other GISAs grown in the presence of vancomycin. MSSA-derived BB255V3, which is among the least resistant of the GISA strains, appeared to be identical to the parent BB255 in the absence of vancomycin. Cell wall morphologies of parent BB255 grown in the presence or absence of one-half the MIC of vancomycin (0.5 μg/ml) appeared to be identical. With 2 μg of vancomycin per ml in the growth medium, BB255V3 had a diffuse cell wall but it was not thickened as were those of more highly resistant GISA strains in the presence of vancomycin (Fig. 4).

FIG. 2.

Appearance of MRSA parent strain 13136p−m+ grown in the absence (A) or presence (B) of 0.75 μg of vancomycin per ml (i.e., one-half the MIC) and of the GISA derivative 13136p−m+V20 grown in the absence (C) or presence (D) of 8 μg of vancomycin per ml (i.e., one-half the MIC). All cultures were grown to an OD600 of 0.6 in TSB prior to processing for transmission electron microscopic examination. Magnification, ×24,000.

FIG. 3.

Appearance of atl mutant MSSA parent strain SH108 grown in the absence (A) or presence (B) of 1.0 μg of vancomycin per ml (i.e., one-half the MIC) and of GISA derivative SH108V5 grown in the absence (C) or presence (D) of 3 μg of vancomycin per ml (i.e., one-half the MIC). Magnification, ×24,000.

FIG. 4.

Appearance of MSSA parent strain BB255 grown in the absence (A) or presence (B) of 0.5 μg of vancomycin per ml (i.e., one-half the MIC) and of GISA derivative BB255V3 grown in the absence (C) or presence (D) of 2 μg of vancomycin per ml (i.e., one-half the MIC). Magnification, ×32,000.

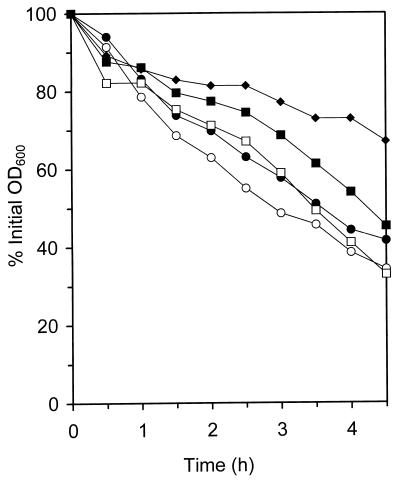

Cell surface hydrophobicities.

Differences among strains in cell surface hydrophobicities were measured as cell partitioning between aqueous and hydrocarbon phases. The results are presented graphically in Fig. 5. Variations in partitioning profiles between buffer and either p-xylene or n-hexadecane indicate cell surface differences between COL, COLV10, and COLV10 grown in the presence of vancomycin (Fig. 5A and B). Similarly, cell surface differences are indicated between RN450 (autolysis sufficient), SH108, SH108V5, and SH108V5 strains grown with vancomycin present (Fig. 5C and D).

FIG. 5.

Hydrophobicity assessments of parent and GISA strains. The remaining OD following differential cell partitioning between hydrocarbon and aqueous layers was plotted against volume of hydrocarbon added. Lower percent initial OD600 values reflect increased hydrophobicities. MRSA parent strain COL (○) and GISA derivative COLV10 grown in the absence (□) or presence (■) of 2 μg of vancomycin per ml were assayed with hydrocarbons p-xylene (A) or n-hexadecane (B). MSSA autolysis-sufficient strain RN450 (▵), MSSA atl mutant SH108 (○), and its GISA derivative SH108V5 grown in the absence (□) or presence (■) of 3 μg of vancomycin per ml were likewise assayed with p-xylene (C) or n-hexadecane (D) as described in Materials and Methods.

Lysostaphin susceptibilities.

A decreased susceptibility to lysostaphin was shown by five of the seven most resistant GISA strains versus their GSSA parents (Table 3). The EOP (values for these GISAs was 1 to 3 orders of magnitude higher following treatment with lysostaphin than those of the parent strains. The two exceptions were SH108 and BB399, which had the lowest autolytic levels of any strains from which GISA strains were selected. The EOP values for these parents was greater than those for their respective mutants, but the differences were within an order of magnitude.

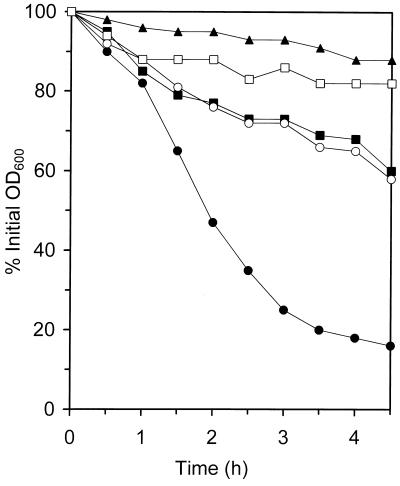

Whole-cell autolytic activities.

Selection for increasingly higher vancomycin MICs produced decreased autolytic activities, which are presented in Table 3 as the percent initial OD600 remaining for flasks of cells suspended in buffer after 4.5 h of shaking at 37°C. Some strains lost very little whole-cell autolytic activity upon acquisition of the GISA phenotype, such as the two COL lines, while most lost a significant amount, such as BB270. Autolytic profiles are shown in Fig. 6 for the 13136p−m+ and SH108 series of strains, demonstrating the decreased autolytic activity associated with the GISA phenotype acquisition. Figure 7 shows the effects that the presence of one-half of the vancomycin MIC for COLV10 had on COL and COLV10 autolytic activities, which were representative of the entire panel of parents and GISA strains. As stated, there was little difference in the autolytic activities of these two strains. The presence of vancomycin at a concentration of 4 μg/ml (one-half the vancomycin MIC for COLV10) in the assay buffer of either strain reduced autolytic activities, with that for COLV10 reduced slightly more than that for COL. Vancomycin in the growth medium of COLV10 resulted in a considerable further reduction.

FIG. 6.

Whole-cell autolytic activity profiles of parent and GISA strains. The profiles MRSA parent strain 13136p−m+ (●), its GISA derivatives 13136p−m+V5 (■) and 13136p−m+V20 (▴), and MSSA atl mutant parent SH108 (○) and its GISA derivative SH108V5 (□) were determined. Autolysis was monitored as a decrease in OD and is presented as a percentage of the initial OD600 determined just after resuspension in lysis buffer.

FIG. 7.

The effect of vancomycin on COL and COLV10 whole-cell autolytic activity profiles. The parent line COL was grown in TSB and then assayed in the absence (○) or presence (●) of 4 μg of vancomycin per ml in the assay buffer. GISA COLV10 was grown and assayed in the absence of vancomycin (□), grown in the absence of vancomycin and assayed in the presence of 4 μg of vancomycin per ml (■), or grown in the presence of 4 μg vancomycin per ml and then assayed in its absence (⧫).

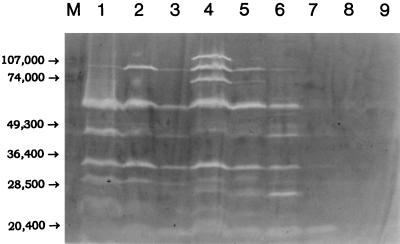

Autolysin profiles.

A zymographic analysis of the autolysins of parent strains BB255, COL, and SH108 and their GISA derivatives BB255V3, COLV10, and SH108V5 (grown in the presence or absence of vancomycin) is presented in Fig. 8. BB255 and COL expressed 9 to 11 discernible bands (peptidoglycan hydrolases), while SH108 produced only one major band, the lytM gene product (25). BB255V3, for which the vancomycin MIC was only slightly above that for the parent strain, had an autolysin profile that only differed from the that of the parent by a few variations in band intensities when grown in the absence of vancomycin. When grown with vancomycin present, the band intensities decreased substantially. COLV10 showed greatly reduced band intensities versus parent strain COL in the absence of vancomycin, and when grown in the presence of vancomycin the band intensities were further reduced. Two of the autolysins whose expression was reduced by the inclusion of vancomycin in the growth media of BB255V3 and COLV10 correspond to the atl gene products, the 51-kDa endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase and the 62-kDa N-acetylmuramoyl-l-alanine amidase (23). SH108V5 expressed only very faint autolytic bands in either the presence or the absence of vancomycin and had lost nearly all of the LytM activity present in the parent strain.

FIG. 8.

Autolysin zymogram of parent strains and GISA derivatives grown in the absence or presence of vancomycin. Lane M, prestained molecular mass markers (in daltons); lanes 1 to 9, autolysins of parent strains, GISA derivatives, and GISA strains grown in the presence vancomycin at a concentration of one-half the MIC, visualized as bands of lytic activity (clearings) in gels containing 0.2% (wt/vol) crude RN450 cell walls as substrate. Lane 1, BB255; lane 2, BB255V3; lane 3, BB255V3 grown in the presence of 2 μg of vancomycin per ml; lane 4, COL; lane 5, COLV10; lane 6, COLV10 grown in the presence of 4 μg of vancomycin per ml; lane 7, SH108; lane 8, SH108V5; lane 9, SH108V5 grown in the presence of 3 μg of vancomycin per ml.

Vancomycin removal from the medium.

A bioassay to compare the capacities of the most highly resistant GISA strains to remove vancomycin from the medium to those of the parent strains was performed, and the results are presented in Table 3. The GISA strains removed 2 to 8 μg more vancomycin per ml than their parents had, although there was no direct correlation between the amount removed and the vancomycin MIC. The capacity of BB270V15 to remove vancomycin from the medium was the lowest of the GISA strains assayed, though the vancomycin MIC and MBC for this strain were among the highest of the GISA panel. Colonies could not be produced by any strain after the 24-h incubation in 64 μg/ml (data not presented).

DISCUSSION

Isogenic MRSA-MSSA pairs and the two COL lines served as tools for the identification of strain-specific GISA characteristics, and the inclusion of strains from disparate genetic backgrounds in this study allowed common GISA elements to be recognized. Such observations would not have been possible with one or two sets of strains or if the GSSA parent strains were not available for study. Ease of acquisition of the GISA phenotype appeared to be a strain-specific trait, as isogenic pairs always behaved identically in this respect. The difference in ease of acquisition between the two COL lines suggested that this trait can vary due to relatively minor genetic differences. That all four strains failing to acquire the GISA phenotype were members of two sets of isogenic pairs and that relatively high levels of resistance were selected in both COL lines implied that the level of resistance that could be easily selected was also strain specific. Finally, the similar whole-cell autolytic activity responses of the two COL lines to selection for increasingly higher vancomycin MICs suggested that a strain-specific component was involved in this trait as well.

With both sets of isogenic MRSA-MSSA pairs (BB270-BB255 and 13136p−m+-13136p−m−), a higher level of glycopeptide resistance was selected in the MRSA member. The implication that MRSA strains are more amenable to the acquisition of the GISA phenotype than MSSA strains was intriguing, as it suggests some interaction between the mec determinant and the GISA resistance mechanism. Oxacillin-resistant S. haemolyticus strains were noted to possess an increased potential for the development of teicoplanin resistance versus oxacillin susceptible strains in several studies (1). Increased penicillin-binding protein (PBP) production has been reported in GISA strains (19), with PBP2a cited as overproduced in some instances (15). We have shown that there was no correlation between high-level (homogeneous) and low-level (heterogeneous) methicillin resistance expression and the ease of acquisition of the GISA phenotype, but cellular levels of PBP2a do not correlate with levels of methicillin resistance expression (8). Additionally, none of the MRSA strains in this study demonstrated a reduction in methicillin MIC upon acquisition of the GISA phenotype, in contrast to that observed in the passage-selected COL-derived GISA strains of Sieradzki and Tomasz (31, 32). That five of six MRSA strains were able to develop MICs of vancomycin comparable to the clinical GISA strains currently causing concern suggested that many other MRSA strains are capable of this as well. Conversely, the inability to select the GISA phenotype in an MRSA strain and in three MSSA strains suggests that the GISA phenotype is not an inevitable outcome of prolonged glycopeptide treatment of S. aureus infections.

A number of GISA traits were apparently not strain specific but were common to the phenotype at least to some extent. These included resistance level stability to passage on nonselective medium, decreased growth rate, concomitant acquisition of teicoplanin resistance, an increased capacity to remove vancomycin from the medium, abnormal cell wall morphology, and resistance to lysostaphin. All of these features have been reported in other GISA strains, although they are not always expressed in the same fashion. The acquisition of teicoplanin resistance has been observed to precede that of resistance to vancomycin in some isolates (13), but this was not observed in isolates from the early stages of step selection in this study, as represented by BB255V3 (Table 2). Staphylococci are generally more resistant to teicoplanin than to vancomycin (1), and this was borne out in our GISA strains, for which the MICs of teicoplanin were 2 to 4 μg/ml higher than those of vancomycin. The thickened and uneven cell wall morphology of our GISA strains was strikingly similar to that of Tomasz's passage-selected VM mutant, which also had reduced lysostaphin susceptibility, decreased autolytic activity, and an increased capacity to remove vancomycin from the medium. However, that mutant, derived from a COL line not used in this study, only expressed reduced autolytic activity and growth rate in the presence of vancomycin. Rotun et al. (27) reported a clinical GISA isolate with a reduced growth rate in the absence of vancomycin, but its autolytic activities and cell wall morphology were not described. Mutant VM lost almost all of its methicillin resistance expression, expressed its vancomycin resistance heterogeneously, and had no major alterations in autolysin banding patterns on zymograms. Some of this may reflect strain-specific differences between VM and the two COL lines in this study, which behaved differently from one another with respect to ease of GISA phenotype acquisition. From the description of its isolation, VM seems to have acquired the GISA phenotype rapidly (31), versus the apparent slowly acquiring 523k strain from Daum's laboratory (6). For VM the vancomycin MIC is 100 μg/ml (31), while such a level could not be selected for in our lines.

The laboratory isolate of Daum and the clinical isolates of Hiramatsu have thickened cell walls even in the absence of vancomycin (11). The cell walls of these GISA strains have relatively smooth surfaces. These “even-walled” GISA strains are in sharp contrast to the “uneven-walled” GISA strains selected in this study which, like Tomasz's mutant VM, had much thicker cell walls with very rough surfaces. Although have been no reports on the cell wall morphologies of the Michigan or New Jersey clinical isolates, a clinical GISA has recently been isolated that exhibits the uneven-walled morphology when grown in the presence of vancomycin (30). The cell walls of our isolates in the absence of vancomycin appeared to be the same as those of the parents in micrographs but clearly were not, as demonstrated by differences in autolytic activities, growth rates, lysostaphin susceptibilities, and hydrophobicity studies between parent and GISA strains in the absence of vancomycin. These results suggest that the cell walls of the GISAs have an altered composition compared to the parent strains and that the thickening and unevenness (apparently produced by a buildup of cell wall material) is in response to the presence of the glycopeptide.

Parent strain 13136p−m+ had a rough cell wall surface when grown in the presence of vancomycin, but the parent strain BB255 did not. This suggests that the genetic background of 13136p−m+ enabled it to express this GISA-associated trait which, although not imparting resistance, may have allowed for the rapid selection of a relatively high vancomycin MIC (16 μg/ml), while BB255 did not progress beyond the 4-μg/ml vancomycin MIC for BB255V3 during selection. However, the concentration of vancomycin in the growth medium was not the sole determinant of whether a given strain, parent or GISA, could grow in that medium. Growth was not observed at half the MIC of vancomycin if the inoculum was sufficiently dilute. The absence of a roughened cell wall in BB255 grown in the presence of 0.5 μg of vancomycin per ml may have been due to the ratio of cell wall material to vancomycin molecules. A vancomycin concentration of more than 0.5 μg/ml, but less than the MIC of 1.0 μg/ml, might have prompted the expression of a roughened cell wall given the inoculum used to start the culture, which was later processed for transmission electron microscopy. Any slight roughening of parent SH108 cell walls by growth in one-half the MIC of vancomycin was not discernible due to the diffuse nature of the cell walls of this autolysis-deficient mutant.

Altered autolytic activities are always associated with the GISA phenotype. Hiramatsu's clinical isolates express increased autolytic activities, but Daum's passage-selected even-walled GISA strain expresses reduced autolytic activities (R. S. Daum and S. Boyle-Vavra, personal communication). The uneven-walled GISA strains of this study and from Tomasz's laboratory also express decreased autolytic activities. The Michigan and New Jersey clinical isolates have whole-cell autolytic activities comparable to those of the GISA strains selected in this study (unpublished data). Reduced autolytic activity may contribute to the accumulation of cell wall material observed in conjunction with the uneven-walled GISA morphology (31). This is presumably associated with the increased capacity to bind vancomycin observed with intact cells of VM and strains in this study and with purified peptidoglycan alone from both VM and Mu50 (12, 31). It is difficult to hypothesize as to what contribution autolytic activity alteration makes toward the development of the even-walled morphology given the contradictory observations of Hiramatsu and Daum. The zymographic analysis of several of the present study's GISA strains, which compared the unrelated COL and BB255 series of strains, showed a general decrease in peptidoglycan hydrolase production with the acquisition of higher-level glycopeptide resistance (i.e., COLV10), including the atl gene products reported by Hiramatsu as expressing increased activities in Mu50.

The atl mutant GISA SH108V5 expressed very little autolytic activity in either the presence or the absence of vancomycin, yet its doubling time was comparable to those of other GISA strains for which the vancomycin MICs were similar. The whole-cell autolysis activity reductions for BB255V3 and COLV10 were similar and relatively minor in comparison to most of the other GISA strains. However, zymography indicated that COLV10 expressed considerably less overall autolytic activity than did BB255V3. The explanation probably lies in the poorly understood autolytic redundancy of staphylococci, whereby cells produce a large number of autolytic enzymes and yet grow normally in the absence of most of these activities (18). Autolysis assays utilizing protein recovered, quantified, and concentrated from parent and GISA strains grown in the presence or absence of vancomycin indicated that strains grown in the presence of vancomycin produced reduced levels of autolysins as opposed to an increased release of these enzymes into the medium (data not presented).

It has not gone without notice that in spite of the varied genetic backgrounds of the strains employed in this study, all of the GISA strains selected were of the uneven-walled type, have reduced autolytic activities, and express glycopeptide resistance in an exclusively homogeneous manner. The increments between antibiotic dilutions used for glycopeptide MICs were reduced at the lower concentrations in an effort to detect heterogeneity of resistance expression. No heterogeneously resistant GISA strains were found, even among strains for which the vancomycin MICs near those for the parent strains, where heterogeneity has been observed in other isolates (14). It is possible that some of the features common among the GISA strains in this study were common by virtue of the selection conditions. The selection methodology we employed has the advantage of allowing the monitoring of the inoculum effect known to be associated with vancomycin (1). Since cells are present in different concentrations in 10-μl droplets and a spread-out 50-μl aliquot, the inoculum effect is no longer significant when both platings yield identical calculations of CFU per milliliter for the original dilution. Daum used a different passage methodology relying on extensive dilution in a different medium than utilized in this study (6), and Tomasz's passage methodology included methicillin in the selective medium in addition to vancomycin (31). Neither of these procedures allowed the inoculum effect to be monitored during the selection process. The in vivo-selected clinical isolates, even those isolated from the same individual, could also have experienced very different environments during selection by prolonged vancomycin therapy. Heterogeneity of glycopeptide resistance expression may be a selection methodology-dependent trait. Tomasz's GISA (VM) strain expresses glycopeptide resistance heterogeneously, as does Hiramatsu's low-level resistance isolate (Mu3) and the New Jersey clinical isolate. Hiramatsu's high-level resistance isolate, Mu50, the Michigan clinical isolate, and all of the strains in this study express glycopeptide resistance in a homogeneous manner.

Cell wall alterations, autolytic activity changes, and the removal of vancomycin from the medium all suggest a common basis for the GISA resistance mechanism. Yet these common traits are not necessarily expressed in similar fashions and may vary in their functional roles as well. The GISA phenotype seems to arise from the accumulation of mutations. It is possible that there exists a pool of potential mutations, not all of which are required for the acquisition of the phenotype. Two different GISA strains selected under different conditions may accumulate different combinations of mutations and yet express common GISA traits and show similar vancomycin MICs. Additionally, the genetic background of a given strain may predispose it toward the accumulation of certain combinations of mutations over others.

The results of this study did not indicate a specific, stepwise sequence of GISA traits accumulated as increasingly greater resistance levels were selected. Instead, increased expression of these traits was observed during the selection process. Increased doubling times and capacities to remove vancomycin from the medium, and reductions in autolytic activities and lysostaphin susceptibilities were usually all present in GISA strains with both higher and lower glycopeptide resistances but were generally expressed to a greater extent in those strains for which the MICs were higher. In contrast to Hiramatsu's Mu3 and Mu50, our GISA strains with low-level resistance, such as BB255V3, expressed cell wall thickening, but to a lesser extent than did the high-level GISAs such as 13136p−m+V20. It is unknown if this is due to differences between the uneven- and even-walled morphologies or if it is due to differences in selection methodology (as the uneven- versus even-walled morphology itself may be). Our GISA strains provide us with a panel of strains for further investigation of the vancomycin resistance mechanism, including cell wall composition, peptidoglycan pool precursor analysis, PBP profiles, and cytoplasmic membrane protein profiles.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported in part by grant 1 R15 AI43027-01 from the National Institutes of Health to Brian J. Wilkinson.

REFERENCES

- 1.Biavasco F, Giovanetti E, Montanari M P, Lupidi R, Varaldo P E. Development of in-vitro resistance to glycopeptide antibiotics: assessment in staphylococci of different species. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1991;27:71–79. doi: 10.1093/jac/27.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Billot-Klein D, Shlaes D, Bryant D, Bell D, Legrand R, Gutmann L, van Heijenoort J. Presence of UDP-N-acetylmuramyl-hexapeptides and -heptapeptides in enterococci and staphylococci after treatment with ramoplanin, tunicamycin, or vancomycin. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4684–4688. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.15.4684-4688.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown D F J, Reynolds P E. Intrinsic resistance to β-lactam antibiotics in Staphylococcus aureus. FEBS Lett. 1980;76:275–278. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(80)80455-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control. Reduced susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus to vancomycin—Japan, 1996. Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 1997;46:624–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control. Update: Staphylococcus aureus with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin—United States, 1997. Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 1997;46:813–815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daum R S, Gupta S, Sabbagh R, Milewski W M. Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus isolates with decreased susceptibility to vancomycin and teicoplanin: isolation and purification of a constitutively produced protein associated with decreased susceptibility. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:1066–1072. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.5.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Debbia E, Varaldo P E, Schito G C. In vitro activity of imipenem against enterococci and staphylococci and evidence for high rates of synergism with teicoplanin, fosfomycin, and rifampin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986;30:813–815. doi: 10.1128/aac.30.5.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Lencastre H M, DeJonge B L M, Matthews P R, Tomasz A. Molecular aspects of methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1994;33:7–24. doi: 10.1093/jac/33.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foster S J. Molecular characterization and functional analysis of the major autolysin of Staphylococcus aureus 8325/4. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5723–5725. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.19.5723-5725.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gustafson J E, Berger-Bächi B, Strassle A, Wilkinson B J. Autolysis of methicillin-resistant and -susceptible Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:566–572. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.3.566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanaki H, Kuwahara-Arai K, Boyle-Vavra S, Daum R S, Labischinski H, Hiramatsu K. Activated cell-wall synthesis is associated with vancomycin resistance in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clinical strains Mu3 and Mu50. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;42:199–209. doi: 10.1093/jac/42.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanaki H, Labischinski H, Inaba Y, Kondo N, Murakami H, Hiramatsu K. Increase in glutamine-non-amidated muropeptides in the peptidoglycan of vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain Mu50. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;42:315–320. doi: 10.1093/jac/42.3.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiramatsu K. Vancomycin resistance in staphylococci. Drug Res Updates. 1998;1:135–150. doi: 10.1016/s1368-7646(98)80029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hiramatsu K, Aritaka N, Hanaki H, Kawasaki S, Hosoda Y, Hori S, Fukuchi Y, Kobayashi I. Dissemination in Japanese hospitals of strains of Staphylococcus aureus heterogeneously resistant to vancomycin. Lancet. 1997;350:1670–1673. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)07324-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hiramatsu K, Hanaki H, Ino T, Yabuta K, Oguri T, Tenover F C. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clinical strain with reduced vancomycin susceptibility. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;40:135–136. doi: 10.1093/jac/40.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaatz G W, Seo S M, Dorman N J, Lerner S A. Emergence of teicoplanin resistance during therapy of Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis. J Infect Dis. 1990;162:103–108. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mani N, Baddour L M, Offutt D Q, Vijaranakul U, Nadakavukaren M J, Jayaswal R K. Autolysis-defective mutant of Staphylococcus aureus: pathological considerations, genetic mapping, and electron microscopic studies. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1406–1409. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.4.1406-1409.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mani N, Tobin P, Jayaswal R K. Isolation and characterization of autolysis-defective mutants of Staphylococcus aureus created by Tn917-lacZ mutagenesis. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1493–1499. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.5.1493-1499.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moreira B, Boyle-Vavra S, DeJonge B L M, Daum R S. Increased production of penicillin-binding protein 2, increased detection of other penicillin-binding proteins, and decreased coagulase activity associated with glycopeptide resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1788–1793. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.8.1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. 4th ed. 1997. Approved standard M7-A4. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Villanova, Pa. [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. 2nd ed. 1990. Approved standard M7-A2. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Villanova, Pa. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noble W C, Virani Z, Cree R G A. Co-transfer of vancomycin and other resistance genes from Enterococcus faecalis NCTC 12201 to Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;93:195–198. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90528-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oshida T, Sugai M, Komatsuzawa H, Hong Y-M, Suginaka H, Tomasz A. A Staphylococcus aureus autolysin that has an N-acetylmuramoyl-l-alanine amidase domain and an endo-N-acetylglucosaminidase domain: cloning, sequence analysis, and characterization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:285–289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.1.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paulsen I T, Firth N, Skurray R A. Resistance to antimicrobial agents other than β-lactams. In: Crossley K B, Archer G L, editors. The staphylococci in human disease. New York, N.Y: Churchill Livingstone; 1997. pp. 175–212. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramadurai L, Jayaswal R K. Molecular cloning, sequencing, and expression of lytM, a unique autolytic gene of Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3625–3631. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.11.3625-3631.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reifsteck F, Wee S, Wilkinson B J. Hydrophobicity-hydrophilicity of staphylococci. J Med Microbiol. 1987;24:65–73. doi: 10.1099/00222615-24-1-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rotun S S, McMath V, Schoonmaker D J, Maupin P S, Tenover F C, Hill B C, Ackman D M. Staphylococcus aureus with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin isolated from a patient with fatal bacteremia. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:147–149. doi: 10.3201/eid0501.990118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sabath L D, Wallace S J, Byers K, Toftegaard I. Resistance of Staphylococcus aureus to penicillins and cephalosporins: reversal of intrinsic resistance with some chelating agents. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1974;236:435–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1974.tb41508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwalbe R S, Stapleton J T, Gilligan P H. Vancomycin-resistant staphylococcus. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:766–768. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198709173171212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sieradzki K, Roberts R B, Haber S W, Tomasz A. The development of vancomycin resistance in a patient with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:517–523. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902183400704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sieradzki K, Tomasz A. Inhibition of cell wall turnover and autolysis by vancomycin in a highly vancomycin-resistant mutant of Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2557–2566. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.8.2557-2566.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sieradzki K, Tomasz A. Suppression of glycopeptide resistance in a highly teicoplanin-resistant mutant of Staphylococcus aureus by transposon inactivation of genes involved in cell wall synthesis. Microb Drug Res. 1998;4:159–168. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1998.4.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanaka M, Wada N, Kurosaka S M, Chiba M, Sato K, Hiramatsu K. In-vitro activity of DU-6859a against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates with reduced susceptibilities to vancomycin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;42:552–553. doi: 10.1093/jac/42.4.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tenover F C, Lancaster M V, Hill B C, Steward C D, Stocker S A, Hancock G A, O'Hara C M, Clark N C, Hiramatsu K. Characterization of staphylococci with reduced susceptibilities to vancomycin and other glycopeptides. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1020–1027. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.4.1020-1027.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wenzel R P, Nettleman M D, Jones R N, Pfaller M A. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: implications for the 1990s and effective control measures. Am J Med. 1991;91(Suppl. 3B):2215–2275. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(91)90372-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]