Abstract

Although the Uniform Determination of Death Act (UDDA) has served as a model statute for 40 years, there is a growing recognition that the law must be updated. One issue being considered by the Uniform Law Commission's Drafting Committee to revise the UDDA is whether the text “all functions of the entire brain, including the brainstem” should be changed. Some argue that the absence of diabetes insipidus indicates that some brain functioning continues in many individuals who otherwise meet the “accepted medical standards” like the American Academy of Neurology's. The concern is that the legal criteria and the medical standards used to determine death by neurologic criteria are not aligned. We argue for the revision of the UDDA to more accurately specify legal criteria that align with the medical standards: brain injury leading to permanent loss of the capacity for consciousness, the ability to breathe spontaneously, and brainstem reflexes. We term these criteria neurorespiratory criteria and show that they are well-supported in the literature for physiologic and social reasons justifying their use in the law.

Introduction

At the end of the 1970s, neurologic criteria for death were recognized in roughly half of the United States, resulting in a confusing legal landscape. To achieve uniformity across state lines and alignment of the law with medical practice, the President's Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavior Research recommended state legislators adopt the Uniform Determination of Death Act (UDDA)1:

An individual who has sustained either irreversible cessation of circulatory and respiratory functions or irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brainstem, is dead. A determination of death must be made in accordance with accepted medical standards.

Although it has served as a model statute for 40 years, and has been embraced in whole or in part throughout the United States,2 there is a growing recognition that the UDDA must be updated.3-5 The Uniform Law Commission recently approved a Study Committee's recommendation to form a Drafting Committee that should submit its proposed UDDA revisions by July 2023. Meanwhile, Nevada, Oklahoma, and Texas have already moved to amend their own UDDA statutes (NV. A.B. 424 [2017], Okla. H.B. 1896 [2021], Tex. H.B. 4,329 [2021]). Contentious aspects of the UDDA include interpretation of the phrases “all functions of the entire brain” (vs some specific set of functions) and “accepted medical standards” (should they be specifically named?) and whether accommodations are needed to address religious or principled objections to determining death by neurologic criteria (DNC).6-9 Here, we propose a solution to the alleged inconsistency between the meaning of “all functions of the entire brain” and “accepted medical standards” by transitioning from an anatomical approach to DNC to a functional approach, like the approach to death by circulatory criteria. This change will align the law with medical practice, bolster confidence among examiners in the reliability of the currently accepted medical standards, and transparently communicate to the public what the standards are expected to assess.

The currently accepted medical standards for DNC (published by the American Academy of Neurology in 2010 and the Society of Critical Care Medicine, American Academy of Pediatrics, and Child Neurology Society in 2011)10-12 require documentation of an injury that explains the loss of brain function, the exclusion of confounding conditions, and a clinical examination that demonstrates unarousable unresponsiveness, brainstem areflexia, and apnea. Some argue that the absence of diabetes insipidus in many individuals who meet these standards indicates that some functions of the brain continue after pronouncement of death, namely those in the neurosecretory hypothalamus that regulate salt and water balance.13,14 With this in mind, a Nature editorial argued, “The time has come for a serious discussion on redrafting laws that push doctors towards a form of deceit.”15(p570) To align the law with practice, either the “accepted medical standards” must include a more demanding set of tests that exclude neurosecretory functioning or the text requiring cessation of “all functions of the entire brain” must be revised.16,17

At some level, the criteria used to determine death must be a matter of convention and consensus.18,19 The relevant question is not whether any brain functions remain, but rather whether those functions contradict a determination of death. Unlike consciousness, responsiveness, or spontaneous respiratory effort, outside of a discussion about the phrase “all functions of the entire brain,” the presence of neurosecretory functioning is not recognized as a contradiction to determination of death.20-25 While we welcome further debate on its significance, we see no reason to reject the recommendations of consensus statements like that of the World Brain Death Project26 that the persistence of neurosecretory function is consistent with DNC.

Therefore, we support revision of the UDDA to more accurately specify legal criteria that align with the medical standards: brain injury leading to permanent loss of (a) the capacity for consciousness, (b) the ability to breathe spontaneously, and (c) brainstem reflexes.3,4 We term these amended criteria “neurorespiratory criteria.” We recognize that there may be different and competing reasons to believe why neurorespiratory criteria are appropriate, as there is even disagreement about this among ourselves, but we all agree that the law would be more clearly aligned with practice if the phrase “all functions of the entire brain” were replaced with language clearly specifying neurorespiratory criteria. The use of neurorespiratory criteria is well-supported in the literature for physiologic and social reasons, justifying its use in the law.

Worldwide Support for Neurorespiratory Criteria

The motivation to declare DNC arose in the context of the critical care setting in which some ventilator-dependent patients were found to be comatose, lacked the capacity to initiate breathing, and no longer had reflexes that mediate pupillary reaction to bright light, spontaneous eye-tracking of objects when the head is abruptly turned, and cough or gag responses.27 According to the 1981 President's Commission's report,1 which articulated justifications for the UDDA, neurologic criteria for death, like circulatory criteria, provide sufficient evidence for the death of the patient and are to be used if there is reason to believe circulatory functioning does not reliably indicate the presence of life.

Many of the arguments made by the President's Commission in Defining Death1 are consistent with the neurorespiratory criterion. The “whole-brain” formulation never meant that every neuron had to fail; rather, it was meant to contrast with the so-called “higher brain” formulation, according to which the permanent loss of consciousness alone is decisive for determining death. “What is missing in the dead,” the drafters argued, “is a cluster of attributes, all of which form part of an organism's responsiveness to its internal and external environment.”1(p36) The relevant “cluster of attributes” becomes clearer in their explanation of the language of “all functions of the entire brain, including the brainstem:”

Thus, if one is conscious or spontaneously breathes, one is not dead. While not explicitly stated, the implication is that if the cause of brain injury is known and confounding factors like hypothermia or drug intoxication are excluded, then permanent loss of the capacities for consciousness and the drive to breathe clinically indicate the permanent loss of the relevant “cluster of attributes” necessary for an organism to live.1(p36)

These attributes are clearly affirmed in the United Kingdom by the Academy of Royal Medical Colleges' A Code of Practice for the Diagnosis and Confirmation of Death28: “when the brain-stem has been damaged in such a way, and to such a degree, that its integrative functions (which include the neural control of cardiac and pulmonary function and consciousness) are irreversibly destroyed, death of the individual has occurred.”28(p13) As to the definition of death, the Academy of Royal Medical Colleges asserts that:

The relationship between the destruction of the brainstem's “integrative functions” and the irreversible loss of the capacities for consciousness and the drive to breathe could not be clearer. Supporters of the brainstem formulation of DNC in the United Kingdom have maintained for decades that neurorespiratory criteria are philosophically and culturally accepted, not only because of their critical importance for continued life, but also because they represent at the neurophysiologic level the departure of the “conscious soul” and the “breath of life.”29,30

The President's Council on Bioethics' 2008 white paper Controversies in the Determination of Death is another landmark document that supports neurorespiratory criteria.31 After reviewing the criticisms of the 1981 President's Commission's report, the majority view of the President's Council (“Position Two”) was that DNC should be accepted as a way to determine the loss of the organism's capacity to perform its “vital work.”31(p60) The authors noted that the loss of the organism's capacity to engage in need-driven interaction with its environment, sensing what it needs (oxygen) and acting to meet those needs (striving to take in air), is what marks the end of the organism.32 This vital activity was explicitly operationalized in terms of neurorespiratory criteria: “If there are no signs of consciousness and if spontaneous breathing is absent and if the best clinical judgment is that these neurophysiologic facts cannot be reversed, Position Two would lead us to conclude that a once-living patient has now died” (emphasis original).32(p64) Like the UK model, Position Two further says, “From a philosophical-biological perspective, it becomes clear that a human being with a destroyed brainstem has lost the functional capacities that define organismic life.”32(p66) Although the authors did not recommend changing the law to a “brainstem-only” formulation, they did clearly recommend using neurorespiratory criteria to determine what they call “total brain failure” (or DNC).33(p12)

Further support for neurorespiratory criteria can be adduced from 2 other representative professional societies. The Canadian Medical Association's 2006 report on the neurologic determination of death34 recommends that the “concept and definition of neurologic death” be defined “as the irreversible loss of the capacity for consciousness combined with the irreversible loss of all brain stem functions [named elsewhere in the document], including the capacity to breathe."34(p3) The WHO's 2012 statement on death criteria says, “Death occurs when there is permanent loss of capacity for consciousness and loss of all brainstem functions.”35(p31) Although the capacity to breathe is not explicitly mentioned, its loss is implied as they recognize that “respiratory arrest” is “secondary to the loss of brainstem function.”35(p13)

The most recent highly influential publication to acknowledge neurorespiratory criteria is the World Brain Death Project (2020), an international consensus statement endorsed by 5 world federations and numerous medical societies. The members recommended that neurologic criteria for death be defined as “the complete and permanent loss of brain function as defined by an unresponsive coma with loss of capacity for consciousness, brainstem reflexes, and the ability to breathe independently.”26(p1081)

The President's Commission, the Royal Medical Colleges, the President's Council, the Canadian Medical Association, the WHO, and the World Brain Death Project all highlighted the importance of brainstem functioning for the capacities of consciousness and spontaneous breathing. The overlap of functions attributable to the brainstem nuclei—emotion, wakefulness and sleep, basic attention, and consciousness itself—are essential for the homeostatic balance of a living organism.36 The principal nuclei involved in modulating cortical activation lie in the upper pons and midbrain, but lower brainstem structures have been also implicated. Detailed examination of the functions of all clinically accessible brainstem nuclei increases certainty that the functions of consciousness and spontaneous breathing have been permanently lost.

Advantages of Neurorespiratory Criteria

We recognize that there can be varying philosophical, religious, cultural, metaphysical, or biological views on when death occurs, but it is necessary for the law to clearly stipulate legal criteria for determining death and for these criteria to align with medical standards.6 As we have demonstrated, neurorespiratory criteria, which have the advantage of basing the determination of death on the loss of key vital functioning rather than anatomical mortality (e.g., “whole-brain death,” “brainstem death,” “cardiac death”) or the presence of cellular electrical activity, are widely accepted and should be incorporated into the UDDA.

When the neurorespiratory criteria are satisfied, they afford just as bright a line between life and death as the accepted medical standards for circulatory criteria. Although this “bright line” is constructed for important social purposes (determining when the grieving process begins, when a marriage ends, when life insurance pays out, when constitutional rights no longer apply, when multiple vital organs can be procured, when requests for autopsy are initiated, and when plans for burial begin39), it is rooted in observable facts, enabling confidence in the determination and the ability to make the distinction between life and death in a timely and efficient manner.34

Although additional revisions to the UDDA are necessary to address other concerns, such as whether the law should specify the medical standards themselves rather than loosely referring to “accepted medical standards,” or whether accommodations are needed to address religious or principled objections to DNC, we recommend that the first sentence of the UDDA be revised to reference cessation of neurorespiratory functions to bring the law in alignment with practice. Rather than require “irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brainstem,” the UDDA should instead require “brain injury leading to permanent loss of (a) the capacity for consciousness, (b) the ability to breathe spontaneously, and (c) brainstem reflexes.”

Glossary

- DNC

death by neurologic criteria

- UDDA

Uniform Determination of Death Act

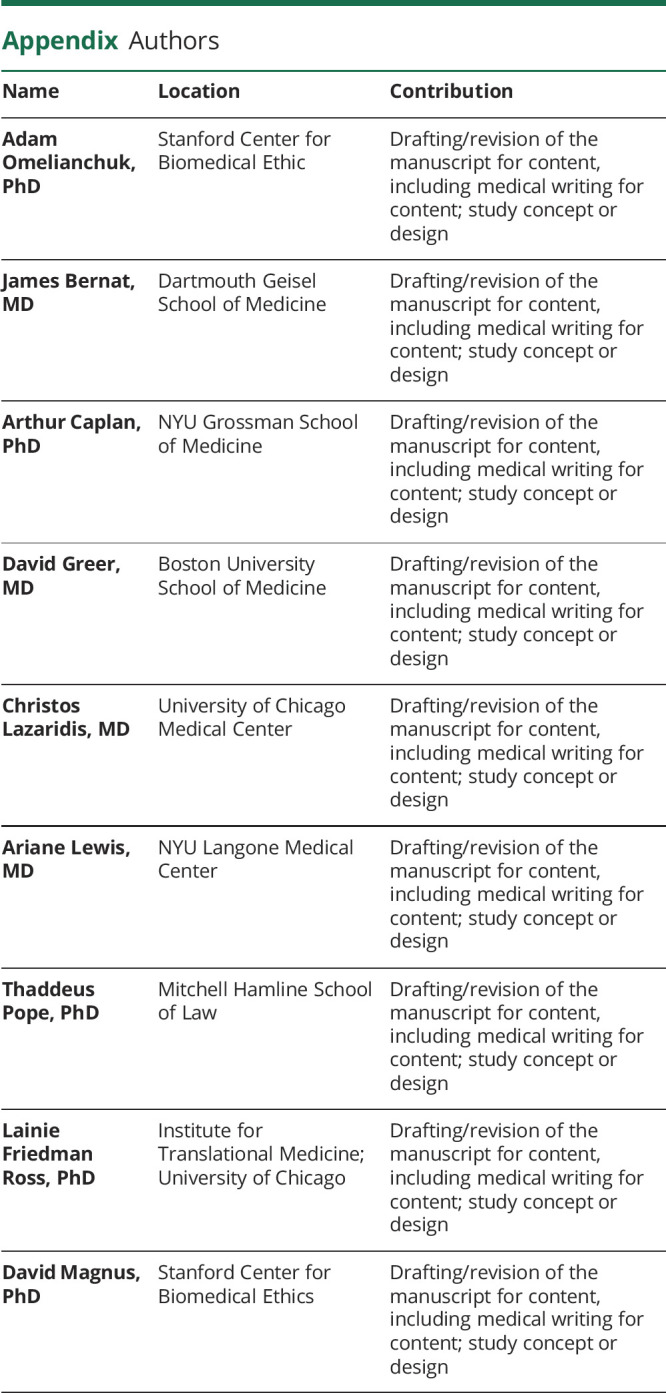

Appendix. Authors

Footnotes

Podcast: NPub.org/Podcast9813

Study Funding

The authors report no targeted funding.

Disclosure

All authors except Dr. Lazaridis are observers participating in drafting of the revision of the Uniform Declaration of Death Act by the Uniform Law Commission. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research. Defining death: medical, legal and ethical issues in the determination of death. President's Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewis A, Cahn-Fuller K, Caplan A. Shouldn't dead be dead? The search for a uniform definition of death. J L Med Ethics. 2017;45:112-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewis A, Bonnie RJ, Pope T, et al. Determination of death by neurologic criteria in the United States: the case for revising the Uniform Determination of Death Act. J L Med Ethics. 2019;47(4_suppl):9-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewis A, Bonnie RJ, Pope T. It's time to revise the Uniform Determination of Death Act. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:143-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shewmon DA. Statement in support of revising the Uniform Determination of Death Act and in opposition to a proposed revision. J Med Philos. Epub 2021 May 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pope T. Brain death and the law: hard cases and legal challenges. Hastings Cent Rep. 2018;48(suppl 4):S46-S48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis A, Greer D. Current controversies in brain death determination. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13(8):505-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olick RS. Brain death, religious freedom, and public policy: New Jersey's landmark legislative initiative. Kennedy Inst Ethics J. 1991;1(4):275-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson LSM. The case for reasonable accommodation of conscientious objections to declarations of brain death. Bioethical Inq. 2016;13:105-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wijdicks EF, Varelas PN, Gronseth GS, Greer DM. Evidence-based guideline update: determining brain death in adults: report of the quality standards subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2010;74(23):1911-1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakagawa TA, Ashwal S, Mathur M, et al. Guidelines for the determination of brain death in infants and children: an update of the 1987 Task Force recommendations. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(9):2139-2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewis A, Bernat JL, Blosser S, et al. An interdisciplinary response to contemporary concerns about brain death determination. Neurology. 2018;90(9):423-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nair-Collins M, Northrup J, Olcese J. Hypothalamic-pituitary function in brain death: a review. J Intens Care Med. 2014;31:41-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halevy A, Brody B. Brain death: reconciling definitions, criteria, and tests. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(6):519-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delimiting death. Nature. 2009;461:570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernat JL, Dalle Ave AL. Aligning the criterion and tests for brain death. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 2019;28(4):635-641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dalle Ave AL, Bernat JL. Inconsistencies between the criterion and tests for brain death. J Intens Care Med. 2020;35:772-780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Capron AM, Kass LR. Statutory definition of the standards for determining human death: an appraisal and a proposal. U Penn Law Rev. 1972;121:87. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Capron AM. Death, Definition and Determination of: II: Legal Issues in Pronouncing Death. In: Post SG, ed. Encyclopedia of Bioethics, 3rd ed. Macmillan Reference; 2004:608-615. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schrader H, Krogness K, Aakvaag A, Sortland O, Purvis K. Changes of pituitary hormones in brain death. Acta Neurochir. 1980;52(3-4):239-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Outwater KM, Rockoff MA. Diabetes insipidus accompanying brain death in children. Neurology. 1984;34(9):1243-1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fiser DH, Jimenez JF, Wrape V, Woody R. Diabetes insipidus in children with brain death. Crit Care Med. 1987;15(6):551-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arita K, Uozumi T, Oki S, Ohtani M, Taguchi H, Morio M. Hypothalamic pituitary function in brain death patients from blood pituitary hormones and hypothalamic hormones. No Shinkei Geka. 1988;16:1163-1171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sugimoto T, Sakano T, Kinoshita Y, Masui M, Yoshioka T. Morphological and functional alterations of the hypothalamic-pituitary system in brain death with long-term bodily living. Acta Neurochir. 1992;115(1-2):31-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brandt SA, Angstwurm H. The relevance of irreversible loss of brain function as a reliable sign of death. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115(41):675-681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greer DM, Shemie SD, Lewis A, et al. Determination of brain death/death by neurologic criteria: the World Brain Death Project. JAMA. 2020;324(11):1078-1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beecher HK, Adams RD, Barger AC. A definition of irreversible coma: report of the ad hoc committee of the Harvard Medical School to examine the definition of brain death. JAMA. 1968;205:337-340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Academy of Royal Medical Colleges. A Code of Practice for the Diagnosis and Confirmation of Death [online]. Academy of Royal Medical Colleges; 2008:1-42. Accessed June 4, 2021. aomrc.org.uk/reports-guidance/ukdec-reports-and-guidance/code-practice-diagnosis-confirmation-death/ [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pallis C, Harley DH. ABC of Brainstem Death, 2nd ed. BMJ Publishing Group; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pallis C. On the brainstem criterion of death. In: Youngner SJ, Arnold RM, Schapiro R, eds. The Definition of Death. John Hopkins University Press; 1999:93-100. [Google Scholar]

- 31.President’s Council on Bioethics. Controversies in the determination of death: a white paper of the President's Council on Bioethics. President's Council on Bioethics; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rubenstein A. What and when is death? The New Atlantis. 2009;29-45. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wijdicks EF. The transatlantic divide over brain death determination and the debate. Brain. 2012;135(Pt 4):1321-1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shemie SD, Doig C, Dickens B, et al. Severe brain injury to neurological determination of death: Canadian forum recommendations. CMAJ. 2006;174(6):S1-S13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.World Health Organization. International Guidelines for the Determination of Death: Phase I [online]. Canadian Blood Services; 2012. Accessed June 7, 2021. who.int/patientsafety/montreal-forum-report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parvizi J, Damasio A. Consciousness and the brainstem. Cognition. 2001;79(1-2):135-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Truog RD. Defining death: making sense of the case of Jahi Mcmath. JAMA. 2018;319:1859-1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khushf G. A matter of respect: a defense of the dead donor rule and of a “whole-brain” criterion for determination of death. J Med Philos. 2010;35:330-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Magnus D. A defense of the dead donor rule. Hastings Cent Rep. 2018;48:S36-S38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]