Abstract

When a total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is implanted using the traditional mechanical alignment technique, this typically results in a straight leg, independently of pre-operative or even pre-arthrotic varus or valgus alignment. With mechanical alignment, we distinguish between 2 different alignment techniques: ligament balancing and bony referencing according to bony skeletal landmarks. In ligament balanced technique beside the straight mechanical axis, the prosthesis is implanted at 90° to the latter. The rotational alignment of the femur is set according to the ligament tension. In the skeletal referenced technique, the rotation of the femur is also set according to bony skeletal landmarks. As a variation of this technique, the prosthesis can be implanted with anatomical alignment. In this technique, the medial slope of the joint line of 3° in the frontal plane is respected during the implantation of TKA. Both techniques result in comparable long-term results with survival rates of almost 80% after 25 years. On the other hand, 15 – 20% of TKA patients report dissatisfaction with their clinical result. For more than 10 years now, the kinematic TKA alignment concept has been developed with the goal to achieve implantation that is adapted to the individual anatomy of the patient. The advocates of this technique expect better function of TKA. This strategy aims to reconstruct the pre-arthrotic anatomy of a given patient while preserving the existing joint line and the mechanical axis without performing ligamentary release. Studies have shown that the function of the prothesis is at least that good as in the conventional techniques. Long-term results are still sparse, but initial studies show that TKA implanted using the kinematic alignment technique exhibit comparable 10-year-survival rates to those implanted using the traditional mechanical alignment technique. Future studies need to show the limitations of this new technique and to identify patients who will or will not significantly benefit from this technique.

Key words: knee arthroplasty, mechanical alignment, gap balancing, measured resection, kinematic alignment

Introduction

Knee arthroplasty is a successful procedure and has been performed in Germany some 170 000 times in 2017 (unicompartmental and bicompartmental) 1 . However, many studies report that 10 – 20% of patients are dissatisfied with their total knee arthroplasty (TKA) 2 , 3 , 4 . Among other things, these patients report pain during exercise, recurrent swelling, stiffness, and feelings of instability when climbing stairs 5 . The fields of implant design 6 and TKA accuracy through navigation or personalised cutting guides 7 have seen many developments in recent years to improve this outcome. Although navigation has increased the accuracy of TKA, the clinical outcome has not improved 8 . Consequently, the alignment concepts for leg axis and joint lines have been reconsidered and refined in recent years.

Definition of Leg Axis, Joint Lines and Ligament Tension for the Knee Joint

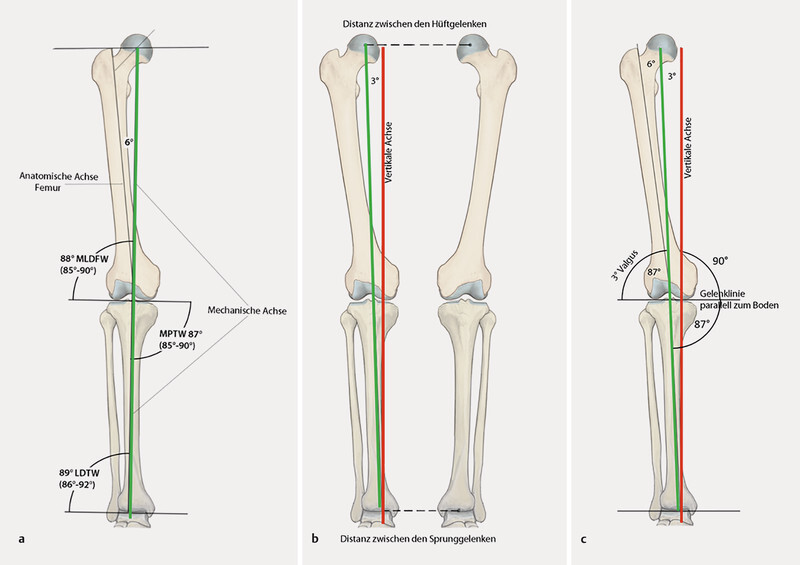

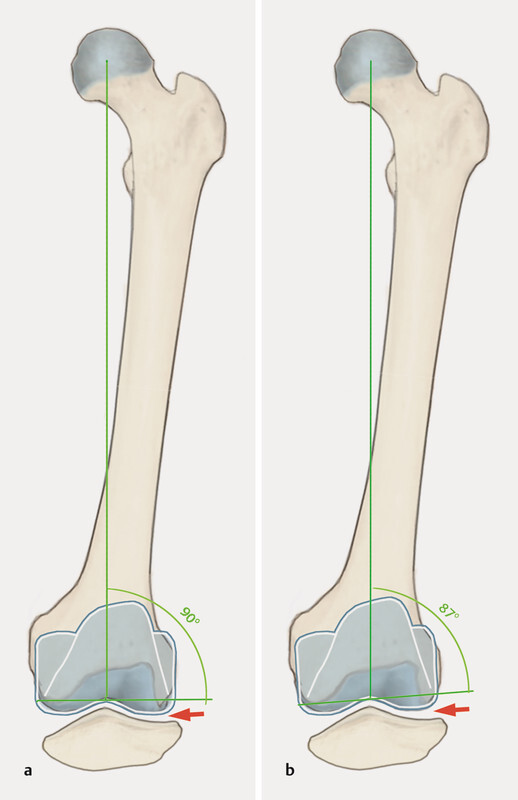

Knowledge of the leg axes and joint lines is indispensable for understanding the individual alignment techniques in knee arthroplasty 9 . The mechanical leg axis is defined as the angle between the mechanical axis of the femur (centre of femoral head–centre of knee joint) and the tibia (centre of knee joint–centre of ankle joint). An interesting note is that in healthy volunteers the mechanical leg axis in the frontal plane on average has about 1° of varus deformity. In addition, men are more likely to have varus legs; according to the literature, a varus deformity of 3° and more is seen in 33%, and 4.5° and more, in 21% of men 10 , 11 . The mechanical axis of the femur runs at an angle of about 5°-7° to the anatomical axis of the femur. The tibiofemoral joint line is not perpendicular to the leg axis, but slopes lateromediad by 3° on average. As a result, the angle between the mechanical axis of the femur and the joint line is not 90° either, but rather 88° on average when measured lateromediad (LDFA–lateral distal femoral angle). Likewise, the medial proximal tibial angle (MPTA) is not 90° either, but averages 87°. These angles have recently been confirmed, but vary greatly between individuals 12 . The difference of about 1° is compensated by the ankle joint, which on average is at 89° to the mechanical axis ( Fig. 1 a ). Recently, Hirschmann suggested a classification of the knee joints according to the three angles above. A neutral leg axis with an MPTA of 87° and an LDFA of 87°, with large variations, is most common 12 . Women tend to have a slightly valgus alignment with a smaller MPTA, while men are more likely to have a slightly more varus tibia resulting in the entire leg axis being varus 13 .

Fig. 1.

a Illustration of the axes and joint lines in the frontal plane of the lower extremity relevant in knee arthroplasty. The joint line is not perpendicular to the mechanical axis (green) but inclines mediad by 3° on average. b When walking, the mechanical axis of the leg is at an angle of 3° to the vertical axis (red), as the ankle joints are closer together than the hip joints. Thus, the mechanical axis of the leg is not perpendicular to the ground. c This ensures that the joint line, which slopes mediad by 3°, parallels the ground when walking. LDFA: lateral distal femoral angle, MPTA: medial proximal tibial angle, LDTA: lateral distal tibial angle. Illustration by R. Himmelhan copyright P. Weber and H. Gollwitzer

When walking, the ankle joint does not line up exactly below the hip joint in the frontal plane, but somewhat further mediad, and this results in an angle of approx. 3° to the mechanical axis ( Fig. 1 b ). This causes the joint line of the knee to parallel to the ground when walking ( Fig. 1 c ) 14 .

In the sagittal axis the tibial slope must be taken into account. This describes the angle between the tibial plateau and the axis of the tibia and is 8° on average for the native knee joint, but varies regularly between 0° and 15° 15 , 16 , 17 .

The physiological ligament tension at the knee joint also varies from person to person and differs in flexion and extension. In flexion in particular, there is an increased laxity of the knee joint on varus stress compared to the medial side and compared to extension 18 . This relative laxity of the lateral ligament complex in flexion is essential for physiological flexion with medial pivoting of the femoral condyle and lateral roll back.

Mechanical Alignment of the Knee Arthroplasty

With his “total condylar knee prosthesis” John Insall propagated the concept of mechanical alignment in knee arthroplasty. He sought to achieve a straight leg axis and an alignment of the femoral and tibial components perpendicular to it, regardless of the deformity. This concept supposedly resulted in uniform lateral and medial loading of the polyethylene 19 . As a result of the early implant failure due to varus placement of the tibial component with older polyethylene inserts and increased wear, the goal was to improve material survival 20 . These considerations were also based on in vitro studies, which demonstrated uniform loading on the insert and under the tibial component when resection was performed perpendicular to the mechanical axis of the tibia and femur 21 .

Mechanical alignment of the knee arthroplasty promotes two techniques:

Ligament balancing, also called “tibia first” or “gap balancing”

Bone referenced (anatomical), also called “femur first” or “measured resection” in minor variants

In recent years, these techniques have been refined further and many surgeons employ hybrid techniques 22 , 23 .

Surgical technique with ligament balancing

Surgery in ligament balancing follows the principles of mechanical alignment and aims to ensure a straight leg axis. Rotational alignment of the femur is based on ligament tension in flexion. The objective is an extension/flexion gap with medial and lateral symmetry. After osteophyte resection (as with any technique), the first surgical step is to resect the tibia perpendicular to the mechanical axis of the tibia shaft (intra-/extramedullary alignment). After intramedullary femoral alignment, the cutting guide for resection of the distal femur is positioned such that the resection is performed perpendicular to the mechanical axis of the femur. This is followed by checking the ligament tension and performing a ligament release on the contracted side, if necessary. The release is continued until the gap is symmetrical with the mechanical leg axis. The cutting guide for the anterior and posterior femoral cut is attached with intramedullary alignment and the rotation of the femoral component adjusts via the ligament tension of the flexion gap. Ligament tensioners may be used here. After anterior and posterior femoral resection, the prosthesis is implanted.

Surgical technique with bony referenced

The intramedullary alignment for resection of the distal femur perpendicular to the mechanical axis of the femur is performed first. The rotation of the femoral component is aligned parallel to the surgical transepicondylar axis or by means of the posterior condyles, with 3° external rotation relative to them 22 , 24 ( Fig. 2 ), which is also known as “measured resection”. This is followed by resection of the tibia perpendicular to the tibial axis. The flexion and extension gaps and the leg axis are then checked. In case of an asymmetrical gap in the varus-valgus alignment, the contracted ligaments are released gradually until the gaps are symmetrical with the straight leg axis. If the flexion and extension gaps are asymmetrical, this has to be corrected by releasing the posterior capsule or by further resection of the distal or posterior femur 25 .

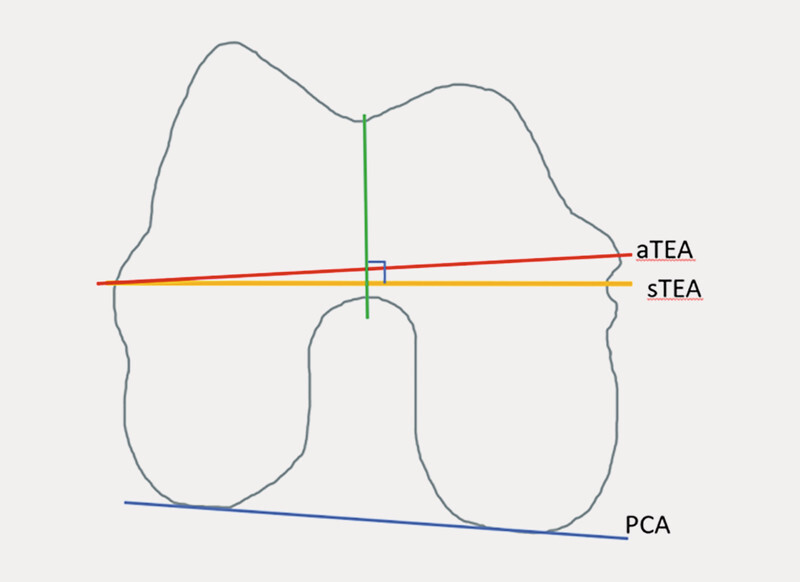

Fig. 2.

Adjusting the rotation of the femoral component (right knee, view of the femur from inferior). With the femur first technique, the implanted prosthesis parallels the surgical transepicondylar axis (sTEA). As a rule, sTEA is used today, which references the sulcus medially, and not aTEA because sTEA reflects more closely the kinematics of the knee joint 57 . On average, it is rotated laterad by 3° compared to the PCA (posterior condyle axis). The Whiteside axis (green), which connects the most inferior point of the trochlea with the most inferior point of the notch, may be used as another reference. The notch is usually perpendicular to the sTEA. Source: P. Weber

Surgical technique with bony referenced – anatomical alignment

As one variant of the standard surgical technique with mechanical alignment, in anatomical alignment, the prosthesis is implanted such that its bearing surface follows the joint line and slopes mediad by 3°. This technique was originally advocated by Hungerford 26 , 27 . For the femur, the distal resection parallels the joint line (sloping mediad by 3°) such that this will restore the lateral distal femoral angle (LDFA). The tibia, too, is resected according to the original joint line sloping inferiorly and mediad by 3°, such that the medial proximal tibial angle is restored, or it is slightly adapted to adjust the leg axis to 180°. The rotation of the femoral component is set to parallel the posterior condyles (PCA, posterior condyle axis) 24 , 28 . This is followed by checking the extension and flexion gaps and performing a soft tissue release as with the other techniques. The release can be challenging because with a previously balanced flexion gap a release on the medial structures in extension can lead to a lax medial flexion gap. This then requires a further release to establish symmetrical conditions and is often difficult to perform 22 .

With the techniques above, which seek to achieve mechanical alignment of the TKA, it can simply be summarised that in TKA with measured resection, the resected bone is replaced and the ligaments are adapted such that the leg is mechanically straightened. In TKA with ligament balancing, ligament tracking is retained and the articulating surfaces are placed where they are guided by the new ligament tracking; the leg axis should be straight postoperatively, which often requires ligament release. With the mechanical alignment technique, which often requires a more extensive release, this carries the risk of iatrogenic ligament injury 29 . With ligament balancing, there is the risk of femoral internal rotation, especially in valgus deformity.

Ligament release

The gradual ligament release has already been described quite often and will therefore only be briefly discussed here 30 . It is important to remember which medial and lateral structures in which position of the knee joint (extension and flexion) are responsible for stability. Medially in extension, it is the superficial and deep fibres of the medial collateral ligament and to a lesser extent the pes anserinus. In flexion, it is mainly the superficial fibres of the medial collateral ligament. Laterally in extension, it is the lateral collateral ligament, the posterolateral capsule, the iliotibial band (at the Gerdy tubercle), less the popliteus tendon and the lateral gastrocnemius tendon. In flexion, the iliotibial tract and the capsule do not provide any substantial stability, but here the other structures mentioned are significant. Once the location of the contracture has been analysed, the corresponding fibres must be released step by step by notching (pie-crusting technique) or gradual detachment at the base 30 .

Kinematic alignment

Kinematic alignment has been promoted and developed over the past 10 years, especially by Stephen Howell, and is based on the technique of measured resection and is known as “true measured resection” 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 . The objective of the kinematic alignment of the prosthesis is to restore the patientʼs native knee kinematics as they existed before the osteoarthritis. This restores the individual joint lines (tibiofemoral) and the natural leg axis. To this end, just enough bone and cartilage is resected distally, posteriorly and tibially, taking into account the worn off cartilage which will be replaced by the TKA components. Usually, the ligaments are not released, only the osteophytes are resected. This procedure restores the ligament tension in all flexion positions to that of the patientʼs native knee joint. Patellar tracking is also usually physiological, as the natural Q angle is restored.

Several techniques for this procedure have been published 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 . The techniques initially published were performed with instruments customized to the patient and designed according to preoperative MRI. Today, there are robot assisted surgical techniques but also those with traditional instruments. Preoperative diagnostic radiography including leg axis is adequate for planning purposes.

The procedure starts with dissection of the femur. The femoral resection of the distal varus-valgus alignment takes into account the anatomical joint line and the cartilage wear to restore the patientʼs LDFA ( Fig. 1 ). This angle can be measured during planning and then restored through appropriate intramedullary alignment. The thickness of the resected cartilage can be reliably checked, as the femoral cartilage is about 2 mm thick and the required resection thickness can be calculated accordingly 37 . The rotation is aligned according to the posterior condyles parallel to the PCA, with the following posterior and anterior cut respecting the cartilage wear.

The tibia is also resected parallel to the joint line, taking into account cartilage wear. Any existing asymmetries in ligament tension require ligament release or are corrected by additional resection at the tibia. Asymmetries between lateral and medial are corrected by appropriate varus or valgus correction, asymmetries between the extension and flexion gaps are offset by increasing or decreasing the tibial slope. The concept of kinematic alignment accepts and even aspires to a physiologically lax lateral flexion gap. With the subsequent trial implants, patella tracking is usually central as the Q angle and femoral alignment have been physiologically preserved according to the rotational axis of the patella 31 . Through kinematic prosthesis alignment, the leg axis is restored to its prearthrotic position, and thus the leg axis is left with a varus or valgus deformity ( Fig. 3 ). This is also based on the idea that the causes of axial deviation are often located outside the joint and therefore cannot be remedied physiologically by intraarticular correction.

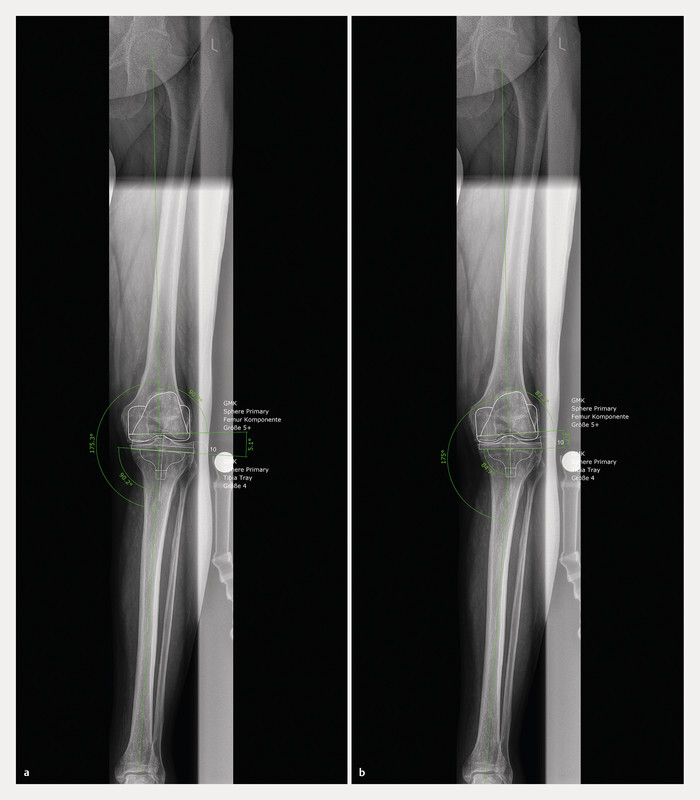

Fig. 3.

Leg axis radiograph of a patient with medial osteoarthritis of the knee and a varus deformity of 5°. a Planning of TKA with mechanical alignment: the tibial and femoral components are inserted with an LDFA and MPTA of 90°. As a result, the varus deformity is corrected by 5.1° resulting in a straight leg axis. This will probably require a medial ligament release. Postoperatively, the joint line will be perpendicular to the leg axis, thus changing by more than 5° due to the surgery. To adjust the flexion gap, this change in the joint line must be compensated either by appropriate ligament release or lateral rotation of the femoral component. b Planning of TKA with kinematic alignment in the same patient. The implanted TKA will keep the LDFA of 87.2° as well as the MPTA of 84.7°. This will correct the varus deformity by 2.7° and leave a varus of 2.5° as it was with the patient before the osteoarthritis. Ligament release will not be necessary, the joint line will be restored as before the surgery, and the rotation of the femoral component will remain unchanged.

Restricted kinematic alignment

Strict kinematic alignment also tolerates greater valgus and varus deformities of more than 5°. Some working groups using kinematic alignment view this critically, as there are no long-term results for such “axis deviations”. This resulted in the development of a so-called “restricted kinematic alignment”. Here, TKAs are implanted with kinematic alignment, with an LDFA and MPFA between 85° and 95° and a postoperative leg axis of ± 3° maximum. In all cases exceeding these values, the angles are corrected until they are within the range of “restricted kinematic alignment” 36 , 38 .

Adjusted mechanical alignment and functional alignment

Other techniques are currently reported, which also attempt to restore the natural kinematics of the knee joint. Put simply, these seek to leave a small measure of residual deformity. Unlike in kinematic alignment, the bony position is corrected if there are major deviations from the traditional target values in mechanical alignment. This supposedly ensures that the position of the TKA does not deviate significantly from these target values. With adjusted mechanical alignment (amA), the tibia is also inserted perpendicular to the tibial axis, as with traditional mechanical alignment. Adjusting the femur to slight varus or valgus angle will leave a small residual deformity. However, deviations of more than 3° varus or valgus are corrected 39 , 40 . Some proponents of this technique have reported good results, but so far only retrospectively and without a control group 39 .

In functional alignment, a slight varus or valgus deformity also remains, but the goal is to establish a leg axis of ± 3° as well. A leg axis with small varus or valgus deformity is obtained by leaving the femur or tibia in varus or valgus alignment, although it is not specified when which corrections are made 41 . This technique demonstrated good results in a trial without control group and is currently being evaluated in an ongoing trial comparing it with mechanical alignment 42 , 43 .

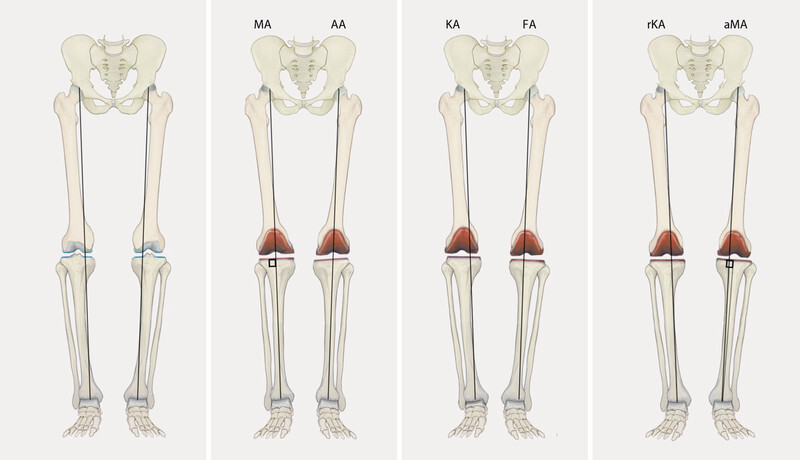

Table 1 presents the target values for the leg axes and the various values for the different techniques. Fig. 4 illustrates the various alignment techniques in the coronal plane.

Table 1 Overview of the various target values for the individual alignment techniques.

| Ligament balancing | Bony referenced | Mechanical alignment (anatomical) | Kinematic alignment (KA) | Restricted kinematic alignment | Adjusted mechanical alignment | Functional alignment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abbreviations: LDFA: lateral distal femoral angle. MPTA: medial proximal tibial angle, TEA: transepicondylar axis, PCA: posterior condylar axis. | |||||||

| Leg axis | 180° | 180° | 180° | Restoration of the patientʼs native leg axis | As in KA, 180 ± 3° max. | 180 ± 3° (leaving a small varus/valgus angle) | 180 ± 3° (leaving a small varus/valgus angle) |

| LDFA | 90° | 90° | 87° | Individual prearthrotic restoration | As in KA, 90 ±–5° max. | 90 ± 3° | 90 ± 3° |

| MPTA | 90° | 90° | 87° | Individual prearthrotic restoration | As in KA, 90 ± − 5° max. | 90° | 90 ± 3° |

| Femoral rotation | By ligament tension on flexion | Paralleling the TEA | Paralleling the PCA | Paralleling the PCA | Paralleling the PCA | Undefined | By ligament tension on flexion, in a corridor of ± 3° to the TEA |

Fig. 4.

Illustration of the various alignment techniques described in the text based on a knee joint with 6° varus deformity. (MA: mechanical alignment, AA: anatomical alignment, KA: kinematic alignment, FA: functional alignment, rKA: restricted kinematic alignment, aMA: adjusted mechanical alignment). Illustration by R. Himmelhan copyright P. Weber and H. Gollwitzer

Pros and Cons of the Various Alignments

The discussion whether the tibial component should be implanted first followed by ligament-guided alignment of the femoral component, or whether the implantation should be performed anatomically, and thus the femur resected first with bony referencing, has been going on for decades. A recent metaanalysis with data from more than 2500 patients did not yield any difference between the techniques in terms of clinical scores and complications 44 . However, both techniques agree that a straight leg axis should be restored with a maximum deviation of ± 3°. Reliable long-term outcome is available for both techniques, and the prosthesis materials and designs have been developed to last long when mechanically aligned. And the instruments have been designed to allow safe mechanically aligned arthroplasty.

In recent years, however, the dogma of the required straight leg with a mechanical axis between ± 3° after knee arthroplasty has been called into question. On the one hand, Bellemans was able to show that only a small percentage of people have a neutral mechanical alignment and that on average the mechanical leg axis at 1.2° varus angle. 33% of men have a varus leg axis of more than 3°. The implantation of TKAs with traditional mechanical alignment always requires a release of the medial collateral ligament in these patients. For these patients, the authors therefore recommend leaving a small degree of varus deformity 10 . On the other hand, a trial at the Mayo Clinic with more than 15 years of follow-up demonstrated that the revision rate of knee joints within the ± 3° target range was comparable to those outside this corridor 45 . Insall himself already noted in 1988 that the concept of the mechanical axis does not do justice to every patient and therefore only represents a “compromise” 46 . The rate of 15 – 20%, presented above, of patients dissatisfied with their TKA, was seen in patients with mechanical alignment. Especially in the patients with constitutional varus deformity described by Bellemans, mechanical alignment of the arthroplasty will result in hyperextension of the medial collateral ligament, which may become symptomatic, and intraoperative release may be difficult to dose 10 . Table 2 lists these pros and cons (after 28 ).

Table 2 Pros and cons of mechanical alignment.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

|

|

Among other things, these developments led to kinematic alignment. Howell was one of the first users and reported very good clinical outcomes in follow-up trials 32 , 33 . Critics of this technique warned that deviation from the perpendicular alignment of the tibia to the mechanical axis could result in early failure 47 . However, several trials were able to confirm that, at least in the medium run, patients with “varus” or “valgus” deviation did not display higher revision rates 32 , 48 . This is because the joint line sloping mediad parallels the ground when walking, as then the distance between the ankle joints is smaller than between the hips. As a result, the load on the tibia during walking becomes physiological again. In addition, kinematic alignment in the varus knee reduces the knee adduction moment compared to mechanical alignment, and this also reduces implant loading 49 .

Personalised implants might be interesting in this context as their different implant and insert thickness restores the patientʼs native joint line. The tibial component can then be implanted perpendicular to the leg axis. It should be noted, however, that certain personalised implants are only approved for the restoration of a neutral leg axis, and thus personalised restoration of the leg axis is not possible with all custom implants.

Since the femoral component is not implanted in 3° external rotation to the transepicondylar axis, increased patellar complaints were predicted for kinematic alignment. However, a very low rate of revision due to patellar problems has been reported (13 patients from a pool of over 3,000 patients) 50 . Initially, this revision rate is surprisingly low, probably due to several factors. Firstly, the Q angle is restored physiologically during kinematic alignment, since the tibial tuberosity remains unchanged during surgery, due to the joint line sloping mediad, and is not lateralised as in mechanical alignment. On the other hand, femoral positioning according to the joint line allows physiological “saddling” of the patella, and the lateral condyle does not move distad ( Fig. 5 ). Another working group was able to demonstrate that intraoperative lateral release was needed in only 2% of cases 38 . With regard to these good outcomes regarding patella function, it should be noted that there have not yet been any trials explicitly following up the outcomes in patients with marked lateralisation or dysplasia of the patella who have undergone TKA with kinematic alignment.

Fig. 5.

a The figure illustrates a TKA with mechanical alignment and an LDFA of 90° and patellar position in flexion. b Prosthesis with kinematic alignment and an LDFA of 87° with the patella in flexion. It can be seen that on flexion the valgus restoration of the LDFA presses the lateral patella less distad than in mechanical alignment. Illustration by R. Himmelhan copyright P. Weber and H. Gollwitzer

A potentially significant benefit of personalised implants is the independent restoration of the trochlea and posterior femoral condyles. In case of a hypoplastic trochlea with lateralised patella, the kinematic alignment of the femoral shield using the posterior condyles can result in a lateralised patella. Personalised implants could direct the anterior femoral shield slightly with external rotation according to the patientʼs anatomy, thus restoring the latter. This may be one option to enable better patellar tracking in dysplasia without having to change the flexion gap by external rotation of the femoral component.

The first published ten-year follow-up reported very low failure rates for kinematic alignment with a survival rate of 97.5% 51 . Several comparative trials have been published in recent years. Some of them, including some randomised trials, showed a benefit in knee function with kinematic alignment. A few trials could not find any differences between the techniques, but kinematic alignment was not inferior in any of the studies. In summary, several metaanalyses demonstrated a benefit for kinematic alignment in terms of clinical scores and flexion 52 , 53 , 54 . Most recently, a metaanalysis was published that included only randomised controlled trials. It is important to note that this analysis did not include a trial from the group led by Howell, the developer of the technique. Better outcomes regarding function, flexion and operating time for kinematic alignment were demonstrated 55 .

When analysing the kinematic alignment technique, however, it must be critically noted that only few long-term results are available, and that it has recently been demonstrated that the 25-year survival rate for TKAs with traditional alignment is 82% 56 . Nor is the question resolved to what extent the native anatomy of the patient should be restored, or when some correction of the anatomy might be appropriate. Whether, for example, a TKA with a leg axis of 6 – 7° valgus deformity will function for a long time is quite uncertain. Until these questions are solved, the techniques of so-called “restricted kinematic alignment” may be useful. For instance, Venditolli et al. recommend TKA according to the native anatomy if in planning the leg axis has a residual valgus or varus deformity of up to 3°; otherwise corrections are recommended until the prosthesis is within this range. They recommend the same approach for the alignment of the femoral and tibial components (LDFA and MPTA), where varus and valgus deviations of 5° maximum from the 90° axis should be tolerated 36 . These recommendations are rather cautious, particularly in view of the fact that VanLommel et al. were able to demonstrate as early as 2013 that patients with varus knee had the best clinical outcome, if their postoperative leg axis was between 3° and 6° varus compared to 0 – 3° varus 39 . However, the technique of “restricted kinematic alignment” could be useful from a medico-legal perspective. Until it is clear which malalignments may be left as they are, the restricted kinematic alignment is currently “safer” because it only leaves small varus or valgus deformities. The same is true for functional alignment, although the data on this is still quite limited 41 . In the case of kinematic alignment, it is advisable to inform the patient preoperatively about leaving him/her with a slight valgus or varus knee. Table 3 lists the pros and cons of kinematic alignment (after 28 ).

Table 3 Pros and cons of kinematic alignment.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

|

|

Conclusion and Outlook

Total knee arthroplasty is safely possible with both bony referencing and ligament balancing. Pursuing a straight leg axis regardless of the baseline situation results in high patient satisfaction and reliable long-term outcome. The outcome in the trials published to date on kinematic alignment of the TKA based on the native anatomy of the patient is at least equivalent in the short and medium run. Restoring the prearthrotic state restores the physiological ligament tension and usually renders a release of the ligament structures unnecessary, with this technique leaving a physiologically somewhat lax lateral flexion gap. Leaving a moderate valgus or varus deformity does not increase the revision rate, at least not in the medium term. The long-term outcome is still open, but it appears that restoring the native anatomy of the patient will play a role in future knee arthroplasties. Future studies are required to reveal the limitations of this new technique and identify those patients who may benefit significantly from kinematic alignment.

However, restoring the patientʼs native anatomy is sometimes difficult to accomplish with the traditional instruments available. It is easier to position a tibia perpendicular to the axis than to restore an angle of 3 – 4° varus deformity. In future, robotics and personalised cutting guides will not only help strive for this precise alignment, but also to achieve it 42 . Only then can the techniques restoring the native anatomy and the conventional techniques be compared exactly, as is being studied in current trials 43 . The conventional alignment techniques cannot yet achieve precise alignment in all cases, which makes it even more difficult to compare the outcome of the various techniques.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest/Interessenkonflikt Both authors are consultants for Medacta, Castel San Pietro, Switzerland./Die Autoren sind Berater für Medacta, Castel San Pietro, Schweiz.

References/Literatur

- 1.Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss Qualitätsreport 2017 Berlin: IQTIG – Institut für Qualitätssicherung und Transparenz im Gesundheitswesen; 2018. Im Internet (Stand: 10.01.2020):https://iqtig.org/downloads/berichte/2017/IQTIG_Qualitaetsreport-2017_2018_09_21.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams D P, OʼBrien S, Doran E. Early postoperative predictors of satisfaction following total knee arthroplasty. doi:10.1016/j.knee.2013.05.011. Knee. 2013;20:442–446. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2013.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parvizi J, Nunley R M, Berend K R. High level of residual symptoms in young patients after total knee arthroplasty. doi:10.1007/s11999-013-3229-7. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:133–137. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3229-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nam D, Nunley R M, Barrack R L. Patient dissatisfaction following total knee replacement: a growing concern? doi:10.1302/0301-620X.96B11.34152. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B:96–100. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.96B11.34152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Worner M, Springorum H R, Craiovan B. [Painful total knee arthroplasty. A treatment algorithm] doi:10.1007/s00132-013-2192-z. Orthopade. 2014;43:440–447. doi: 10.1007/s00132-013-2192-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calliess T, Savov P, Ettinger M. [Current Knee Arthroplasty Designs and Kinematics: Differences in Radii, Conformity and Pivoting] doi:10.1055/a-0623-2867. Z Orthop Unfall. 2018;156:704–710. doi: 10.1055/a-0623-2867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thienpont E, Schwab P E, Fennema P. A systematic review and meta-analysis of patient-specific instrumentation for improving alignment of the components in total knee replacement. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.96B8.33747. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B:1052–1061. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.96B8.33747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng T, Zhao S, Peng X. Does computer-assisted surgery improve postoperative leg alignment and implant positioning following total knee arthroplasty? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials? doi:10.1007/s00167-011-1588-8. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20:1307–1322. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1588-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paley D, Tetsworth K. Mechanical axis deviation of the lower limbs. Preoperative planning of uniapical angular deformities of the tibia or femur. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;(280):48–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bellemans J, Colyn W, Vandenneucker H. The Chitranjan Ranawat award: is neutral mechanical alignment normal for all patients? The concept of constitutional varus. doi:10.1007/s11999-011-1936-5. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:45–53. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1936-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirschmann M T, Hess S, Behrend H. Phenotyping of hip-knee-ankle angle in young non-osteoarthritic knees provides better understanding of native alignment variability. doi:10.1007/s00167-019-05507-1. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27:1378–1384. doi: 10.1007/s00167-019-05507-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirschmann M T, Moser L B, Amsler F. Phenotyping the knee in young non-osteoarthritic knees shows a wide distribution of femoral and tibial coronal alignment. doi:10.1007/s00167-019-05508-0. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27:1385–1393. doi: 10.1007/s00167-019-05508-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirschmann M T, Moser L B, Amsler F. Functional knee phenotypes: a novel classification for phenotyping the coronal lower limb alignment based on the native alignment in young non-osteoarthritic patients. doi:10.1007/s00167-019-05509-z. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27:1394–1402. doi: 10.1007/s00167-019-05509-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paley D. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2002. Principles of Deformity Correction. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Utzschneider S, Goettinger M, Weber P. Development and validation of a new method for the radiologic measurement of the tibial slope. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19:1643–1648. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1414-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Boer J J, Blankevoort L, Kingma I. In vitro study of inter-individual variation in posterior slope in the knee joint. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2009;24:488–492. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faschingbauer M, Sgroi M, Juchems M. Can the tibial slope be measured on lateral knee radiographs? doi:10.1007/s00167-014-2864-1. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22:3163–3167. doi: 10.1007/s00167-014-2864-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tokuhara Y, Kadoya Y, Nakagawa S. The flexion gap in normal knees. An MRI study. doi:10.1302/0301-620x.86b8.15246. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:1133–1136. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.86b8.15246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Insall J N, Binazzi R, Soudry M. Total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985;(192):13–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vail T L, Lang J E. New York: Elsevier; 2017. Surgical Techniques and Instrumentation in total Knee Arthroplasty; pp. 1665–1721. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsu H P, Garg A, Walker P S. Effect of knee component alignment on tibial load distribution with clinical correlation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;(248):135–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sheth N P, Husain A, Nelson C L. Surgical Techniques for Total Knee Arthroplasty: Measured Resection, Gap Balancing, and Hybrid. doi:10.5435/JAAOS-D-14-00320. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2017;25:499–508. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-14-00320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Widmer K H, Zich A. [Ligament-controlled positioning of the knee prosthesis components] doi:10.1007/s00132-015-3099-7. Orthopade. 2015;44:275–281. doi: 10.1007/s00132-015-3099-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berger R A, Crossett L S, Jacobs J J. Malrotation causing patellofemoral complications after total knee arthroplasty. doi:10.1097/00003086-199811000-00021. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;(356):144–153. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199811000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirschner S G, Günther K P. München: Elsevier; 2016. Endoprothetik Kniegelenk; p. 552. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hungerford D S, Krackow K A, Kenna R V. Cementless total knee replacement in patients 50 years old and under. Orthop Clin North Am. 1989;20:131–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hungerford D S, Krackow K A. Total joint arthroplasty of the knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985;(192):23–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mercuri J J, Pepper A M, Werner J A. Gap Balancing, Measured Resection, and Kinematic Alignment: How, When, and Why? doi:10.2106/JBJS.RVW.18.00026. JBJS Rev. 2019;7:e2. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.18.00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Motififard M, Sheikhbahaei E, Piri Ardakani M. Intraoperative repair for iatrogenic MCL tear due to medial pie-crusting in TKA yields satisfactory mid-term outcomes. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00167-020-06126-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whiteside L A. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2004. Ligament Balancing: Weichteilmanagement in der Knieendoprothetik. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Calliess T, Ettinger M, Stukenborg-Colsmann C.[Kinematic alignment in total knee arthroplasty: Concept, evidence base and limitations] Orthopade 201544282–286.288doi:10.1007/s00132-015-3077-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Howell S M, Howell S J, Kuznik K T. Does a kinematically aligned total knee arthroplasty restore function without failure regardless of alignment category? doi:10.1007/s11999-012-2613-z. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471:1000–1007. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2613-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Howell S M, Hodapp E E, Vernace J V. Are undesirable contact kinematics minimized after kinematically aligned total knee arthroplasty? An intersurgeon analysis of consecutive patients. doi:10.1007/s00167-012-2220-2. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthroscopy. 2013;21:2281–2287. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-2220-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Howell S M, Kuznik K, Hull M L. Results of an initial experience with custom-fit positioning total knee arthroplasty in a series of 48 patients. Orthopedics. 2008;31:857–863. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20080901-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Calliess T, Ettinger M, Savov P. Individualized alignment in total knee arthroplasty using image-based robotic assistance: Video article. doi:10.1007/s00132-018-3637-1. Orthopade. 2018;47:871–879. doi: 10.1007/s00132-018-3637-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Almaawi A M, Hutt J RB, Masse V. The Impact of Mechanical and Restricted Kinematic Alignment on Knee Anatomy in Total Knee Arthroplasty. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2017.02.028. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32:2133–2140. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nam D, Lin K M, Howell S M. Femoral bone and cartilage wear is predictable at 0 degrees and 90 degrees in the osteoarthritic knee treated with total knee arthroplasty. doi:10.1007/s00167-014-3080-8. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthroscopy. 2014;22:2975–2981. doi: 10.1007/s00167-014-3080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hutt J R, LeBlanc M A, Masse V. Kinematic TKA using navigation: Surgical technique and initial results. doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2015.11.010. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2016;102:99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2015.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vanlommel L, Vanlommel J, Claes S. Slight undercorrection following total knee arthroplasty results in superior clinical outcomes in varus knees. doi:10.1007/s00167-013-2481-4. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21:2325–2330. doi: 10.1007/s00167-013-2481-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Riviere C, Iranpour F, Auvinet E. Alignment options for total knee arthroplasty: A systematic review. doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2017.07.010. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2017;103:1047–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2017.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oussedik S, Abdel M P, Victor J. Alignment in total knee arthroplasty. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.102B3.BJJ-2019-1729. Bone Joint J. 2020;102-B:276–279. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.102B3.BJJ-2019-1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kayani B, Haddad F S. Robotic total knee arthroplasty: clinical outcomes and directions for future research. doi:10.1302/2046-3758.810.BJR-2019-0175. Bone Joint Res. 2019;8:438–442. doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.810.BJR-2019-0175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kayani B, Konan S, Tahmassebi J. A prospective double-blinded randomised control trial comparing robotic arm-assisted functionally aligned total knee arthroplasty versus robotic arm-assisted mechanically aligned total knee arthroplasty. doi:10.1186/s13063-020-4123-8. Trials. 2020;21:194. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-4123-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li S, Luo X, Wang P. Clinical Outcomes of Gap Balancing vs. Measured Resection in Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Involving 2259 Subjects. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2018.03.015. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:2684–2693. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2018.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parratte S, Pagnano M W, Trousdale R T. Effect of postoperative mechanical axis alignment on the fifteen-year survival of modern, cemented total knee replacements. doi:10.2106/JBJS.I.01398. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:2143–2149. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Insall J N. Presidential address to The Knee Society. Choices and compromises in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;(226):43–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Srivastava A, Lee G Y, Steklov N. Effect of tibial component varus on wear in total knee arthroplasty. doi:10.1016/j.knee.2011.11.003. Knee. 2012;19:560–563. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hutt J, Masse V, Lavigne M. Functional joint line obliquity after kinematic total knee arthroplasty. doi:10.1007/s00264-015-2733-7. Int Orthop. 2016;40:29–34. doi: 10.1007/s00264-015-2733-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Niki Y, Nagura T, Nagai K. Kinematically aligned total knee arthroplasty reduces knee adduction moment more than mechanically aligned total knee arthroplasty. doi:10.1007/s00167-017-4788-z. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26:1629–1635. doi: 10.1007/s00167-017-4788-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nedopil A J, Howell S M, Hull M L. What clinical characteristics and radiographic parameters are associated with patellofemoral instability after kinematically aligned total knee arthroplasty? doi:10.1007/s00264-016-3287-z. Int Orthop. 2017;41:283–291. doi: 10.1007/s00264-016-3287-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Howell S M, Shelton T J, Hull M L. Implant Survival and Function Ten Years After Kinematically Aligned Total Knee Arthroplasty. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2018.07.020. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:3678–3684. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2018.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takahashi T, Ansari J, Pandit H G. Kinematically Aligned Total Knee Arthroplasty or Mechanically Aligned Total Knee Arthroplasty. doi:10.1055/s-0038-1632378. J Knee Surg. 2018;31:999–1006. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1632378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yoon J R, Han S B, Jee M K. Comparison of kinematic and mechanical alignment techniques in primary total knee arthroplasty: A meta-analysis. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000008157. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e8157. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000008157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee Y S, Howell S M, Won Y Y. Kinematic alignment is a possible alternative to mechanical alignment in total knee arthroplasty. doi:10.1007/s00167-017-4558-y. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25:3467–3479. doi: 10.1007/s00167-017-4558-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xu J, Cao J Y, Luong J K. Kinematic versus mechanical alignment for primary total knee replacement: A systematic review and meta-analysis. doi:10.1016/j.jor.2019.02.008. J Orthop. 2019;16:151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2019.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Evans J T, Walker R W, Evans J P. How long does a knee replacement last? A systematic review and meta-analysis of case series and national registry reports with more than 15 years of follow-up. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32531-5. Lancet. 2019;393:655–663. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32531-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Victor J. Rotational alignment of the distal femur: a literature review. doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2009.04.011. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2009;95:365–372. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]