Abstract

The activities of gemifloxacin compared to those of nine other agents was tested against a range of penicillin-susceptible and -resistant pneumococci by agar dilution, microdilution, time-kill, and post-antibiotic effect (PAE) methods. Against 64 penicillin-susceptible, 68 penicillin-intermediate, and 75 penicillin-resistant pneumococci (all quinolone susceptible), agar dilution MIC50s (MICs at which 50% of isolates are inhibited)/MIC90s (in micrograms per milliliter) were as follows: gemifloxacin, 0.03/0.06; ciprofloxacin, 1.0/4.0; levofloxacin, 1.0/2.0; sparfloxacin, 0.5/1.0; grepafloxacin, 0.125/0.5; trovafloxacin, 0.125/0.25; amoxicillin, 0.016/0.06 (penicillin-susceptible isolates), 0.125/1.0 (penicillin-intermediate isolates), and 2.0/4.0 (penicillin-resistant isolates); cefuroxime, 0.03/0.25 (penicillin-susceptible isolates), 0.5/2.0 (penicillin-intermediate isolates), and 8.0/16.0 (penicillin-resistant isolates); azithromycin, 0.125/0.5 (penicillin-susceptible isolates), 0.125/>128.0 (penicillin-intermediate isolates), and 4.0/>128.0 (penicillin-resistant isolates); and clarithromycin, 0.03/0.06 (penicillin-susceptible isolates), 0.03/32.0 (penicillin-intermediate isolates), and 2.0/>128.0 (penicillin-resistant isolates). Against 28 strains with ciprofloxacin MICs of ≥8 μg/ml, gemifloxacin had the lowest MICs (0.03 to 1.0 μg/ml; MIC90, 0.5 μg/ml), compared with MICs ranging between 0.25 and >32.0 μg/ml (MIC90s of 4.0 to >32.0 μg/ml) for other quinolones. Resistance in these 28 strains was associated with mutations in parC, gyrA, parE, and/or gyrB or efflux, with some strains having multiple resistance mechanisms. For 12 penicillin-susceptible and -resistant pneumococcal strains (2 quinolone resistant), time-kill results showed that levofloxacin at the MIC, gemifloxacin and sparfloxacin at two times the MIC, and ciprofloxacin, grepafloxacin, and trovafloxacin at four times the MIC were bactericidal for all strains after 24 h. Gemifloxacin was uniformly bactericidal after 24 h at ≤0.5 μg/ml. Various degrees of 90 and 99% killing by all quinolones were detected after 3 h. Gemifloxacin and trovafloxacin were both bactericidal at two times the MIC for the two quinolone-resistant pneumococci. Amoxicillin at two times the MIC and cefuroxime at four times the MIC were uniformly bactericidal after 24 h, with some degree of killing at earlier time points. Macrolides gave slower killing against the seven susceptible strains tested, with 99.9% killing of all strains at two to four times the MIC after 24 h. PAEs for five quinolone-susceptible strains were similar (0.3 to 3.0 h) for all quinolones, and significant quinolone PAEs were found for the quinolone-resistant strain.

The incidence of pneumococci resistant to penicillin G and other β-lactam and non-β-lactam compounds has increased worldwide at an alarming rate, including in the United States. Major foci of infections presently include South Africa, Spain, Central and Eastern Europe, and parts of Asia (1, 9, 10, 13, 14). In the United States a recent survey has shown an increase in resistance to penicillin from <5% before 1989 (including <0.02% of isolates for which MICs were ≥2.0 μg/ml) to 6.6% in 1991 to 1992 (with 1.3% of isolates for which MICs were ≥2.0 μg/ml) (3). In another, more recent survey, 23.6% (360) of 1,527 clinically significant pneumococcal isolates were not susceptible to penicillin (8). It is also important to note the high rates of isolation of penicillin-intermediate and -resistant pneumococci (approximately 30%) in middle ear fluids from patients with refractory otitis media, compared to other isolation sites (2). The problem of drug-resistant pneumococci is compounded by the ability of resistant clones to spread from country to country and from continent to continent (16, 17).

There is an urgent need for oral compounds for outpatient treatment of otitis media and respiratory tract infections caused by penicillin-intermediate and -resistant pneumococci (9, 10, 13, 14). Available quinolones such as ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin yield moderate in vitro activity against pneumococci, with MICs clustering around the breakpoints (22, 25, 26). Gemifloxacin (SB 265805; LB 20304a) is a new broad-spectrum fluoronaphthyridone carboxylic acid with a novel pyrrolidone substituent (5, 12, 19). Previous preliminary studies (5, 12, 19) have shown that this compound is very active against pneumococci. This study further examined the antipneumococcal activity of gemifloxacin compared to those of ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, sparfloxacin, grepafloxacin, trovafloxacin, amoxicillin, cefuroxime, azithromycin, and clarithromycin by (i) agar dilution testing of 235 quinolone-susceptible and -resistant strains, (ii) examination of resistance mechanisms in quinolone-resistant strains, (iii) time-kill testing of 12 strains, and (iv) examination of the postantibiotic effects (PAEs) of drugs against 6 strains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria.

For determination of agar dilution MICs, quinolone-susceptible pneumococci comprised 64 penicillin-susceptible (MICs, ≤0.06 μg/ml), 68 penicillin-intermediate (MICs, 0.125 to 1.0 μg/ml), and 75 penicillin-resistant (MICs, 2.0 to 16.0 μg/ml) strains (all quinolone susceptible [ciprofloxacin MICs of ≤4.0 μg/ml]). All susceptible strains, and some intermediate and resistant strains, were recent United States isolates. The remainder of the intermediate and resistant strains were isolated in South Africa, Spain, France, Central and Eastern Europe, and Korea. Additionally, 28 strains for which ciprofloxacin MICs were ≥8 μg/ml (obtained from the Alexander Project collection via D. Felmingham and R. Grüneberg, London, United Kingdom) were tested by agar dilution. Although the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) has not defined streptococcal (or pneumococcal) breakpoints for ciprofloxacin, a strain for which the ciprofloxacin MIC is ≥8.0 μg/ml is considered highly resistant for the purposes of these studies.

Additionally, those strains which were not susceptible to ciprofloxacin were tested for mutations in parC, gyrA, parE, and gyrB (20) and for efflux mechanism (4). For time-kill studies, four penicillin-susceptible, four penicillin-intermediate, and four penicillin-resistant strains (two quinolone resistant) were tested, while for PAE studies, five quinolone-susceptible strains and one quinolone-resistant strains were studied.

Antimicrobials and MIC testing.

Gemifloxacin susceptibility powder was obtained from SmithKline Beecham Laboratories, Harlow, United Kingdom; other antimicrobials were obtained from their respective manufacturers. Agar dilution methods were used with 235 strains as described previously (13, 14), using Mueller-Hinton agar (BBL Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, Md.) supplemented with 5% whole (unlysed) sheep blood. Plates were incubated for 20 h in ambient air (13, 14). It is recognized that agar dilution is not recommended by NCCLS for pneumococcal susceptibility testing. However, (i) we feel that agar dilution should be the “gold standard” for evaluation of new compounds, and (ii) our group has utilized this method for many years, and we are confident of its accuracy and reproducibility (7, 13, 14, 22, 23, 25, 26). In all of our studies, agar dilution MICs against pneumococci have been either identical or within one dilution of those obtained by broth microdilution. Standard quality controls, including Streptococcus pneumoniae ATCC 49619, were included in each agar dilution run and yielded results identical to those recommended for these strains by broth microdilution.

Broth MICs for 12 strains tested by time-kill studies and 6 strains tested by PAE studies were performed according to NCCLS recommendations (18) using cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth with 5% lysed defibrinated horse blood. Standard quality control strains, including S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619, were included in each run of agar and broth dilution MICs. Because in time-kill and PAE studies tests were performed in broth, we thought it more accurate to utilize broth microdilution MICs in these cases. In any event, agar dilution MICs were identical to those obtained by broth microdilution in every instance.

Time-kill testing.

For time-kill studies, glass tubes containing 5 ml of cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (Difco) plus 5% lysed horse blood with doubling antibiotic concentrations were inoculated with 5 × 105 to 5 × 106 CFU/ml and incubated at 35°C in a shaking water bath. Antibiotic concentrations were chosen to comprise three doubling dilutions above and three dilutions below the agar dilution MIC. Growth controls with inoculum but no antibiotic were included with each experiment (21, 24).

Lysed horse blood was prepared as described previously (21). The bacterial inoculum was prepared by suspending growth from an overnight blood agar plate in Mueller-Hinton broth until the turbidity matched a no. 1 McFarland standard. Dilutions required to obtain the correct inoculum (5 × 105 to 5 × 106 CFU/ml) were determined by prior viability studies using each strain (21, 24).

To inoculate each tube of serially diluted antibiotic, 50 μl of diluted inoculum was delivered by pipette beneath the surface of the broth. The tubes were then vortexed and plated for viability counts within 10 min (approximately 0.2 h). The original inoculum was determined by using the untreated growth control. Only tubes containing an initial inoculum within the range of 5 × 105 to 5 × 106 CFU/ml were acceptable (21, 24).

Viability counts of antibiotic-containing suspensions were performed by plating 10-fold dilutions of 0.1-ml aliquots from each tube in sterile Mueller-Hinton broth onto Trypticase soy agar–5% sheep blood agar plates (BBL). Recovery plates were incubated for up to 72 h. Colony counts were performed on plates yielding 30 to 300 colonies. The lower limit of sensitivity of colony counts was 300 CFU/ml (21, 24).

Time-kill assays were analyzed by determining the numbers of strains which yielded a Δlog10 CFU per milliliter of −1, −2, and −3 at 0, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h, compared to counts at 0 h. Antimicrobials were considered bactericidal at the lowest concentration that reduced the original inoculum by ≥3 log10 CFU/ml (99.9%) at each of the time points and were considered bacteriostatic if the inoculum was reduced by 0 to <3 log10 CFU/ml. With the sensitivity threshold and inocula used in these studies, no problems were encountered in delineating 99.9% killing, when present. The problem of bacterial carryover was addressed by dilution as described previously (21, 24). For macrolide time-kill testing, only strains for which MICs of ≤4.0 μg/ml were tested.

PAE testing.

The PAE (6) was determined by the viable plate count method, using Mueller-Hinton broth supplemented with 5% lysed horse blood when testing pneumococci. The PAE was induced by exposure to 10 times the MIC for 1 h (6, 27, 28). Additionally, the one quinolone-resistant strain was exposed at quinolone concentrations of five times the MIC. Tubes containing 5 ml of broth with antibiotic were inoculated with approximately 5 × 106 CFU/ml. Growth controls with inoculum but no antibiotic were included with each experiment. Tubes were placed in a shaking water bath at 35°C for 1 h. At the end of the exposure period, cultures were diluted 1:1,000 to remove antibiotic. A control containing bacteria preexposed to antibiotic at a concentration of 0.01 times the MIC was also prepared (27, 28).

Viability counts were determined before exposure and immediately after dilution (0 h) and then every 2 h until the tube turbidity reached a no. 1 McFarland standard. Inocula were prepared by suspending growth from an overnight blood agar plate in broth until the turbidity matched a no. 1 McFarland standard and then diluting to yield an suspension of approximately 5 × 106 CFU/ml (27, 28).

The PAE was defined as T − C, where T is the time required for viability counts of an antibiotic-exposed culture to increase by 1 log10 unit above counts immediately after dilution and C is the corresponding time for the growth control. For each experiment, viability counts (log10 CFU per milliliter) were plotted against time, and results were expressed as the means from two separate assays (6).

PCR of quinolone resistance determinants and DNA sequence analysis.

PCR was used to amplify parC, parE, gyrA, and gyrB by using primers and cycling conditions described by Pan et al. (20). Template DNA for PCR was prepared using a Prep-A-Gene kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) as recommended by the manufacturer. After amplification, PCR products were purified from excess primers and nucleotides with a QIAquick PCR purification kit as recommended by the manufacturer (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.) and sequenced directly using an Applied Biosystems model 373A DNA sequencer. Products from strains with mutations widely described in the literature (e.g., Ser79-Tyr or -Phe in ParC and Ser83-Tyr or -Phe in GyrA) were sequenced once in the forward direction. Products from strains with no mutations in any of the above-mentioned genes or with a previously undescribed mutation were sequenced twice in the forward direction and once in the reverse direction, using products of independent PCRs (7).

Determination of efflux mechanism.

MICs were determined in the presence and absence of 10 μg of reserpine (Sigma Chemicals, St. Louis, Mo.) per ml as described previously (4, 7). Strains for which the ciprofloxacin MIC was at least a twofold lower in the presence of reserpine were then tested against the other quinolones in the presence of reserpine. Tests were repeated three times (4, 7).

RESULTS

Results of agar dilution MIC testing of the 207 strains for which ciprofloxacin MICs were ≤4.0 μg/ml are presented in Table 1. As can be seen, gemifloxacin had the lowest MICs of all quinolones tested, with a range of ≤0.008 to 0.25 μg/ml, followed by trovafloxacin, grepafloxacin, sparfloxacin, levofloxacin, and ciprofloxacin. MICs of amoxicillin, cefuroxime, azithromycin, and clarithromycin rose with those of penicillin G (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Agar dilution MICs for 207 quinolone-susceptible pneumococcal strainsa

| Drug and strain typeb | MIC range (μg/ml) | MIC50 (μg/ml) | MIC90 (μg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Penicillin | |||

| Penicillin S | ≤0.008–0.06 | 0.016 | 0.03 |

| Penicillin I | 0.125–1.0 | 0.25 | 1.0 |

| Penicillin R | 2.0–16.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| Gemifloxacin | |||

| Penicillin S | ≤0.008–0.125 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Penicillin I | ≤0.008–0.25 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| Penicillin R | 0.004–0.125 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| Ciprofloxacin | |||

| Penicillin S | 0.25–4.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 |

| Penicillin I | 0.25–4.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 |

| Penicillin R | 0.5–4.0 | 1.0 | 4.0 |

| Levofloxacin | |||

| Penicillin S | 0.125–4.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 |

| Penicillin I | 0.5–4.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 |

| Penicillin R | 1.0–2.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 |

| Sparfloxacin | |||

| Penicillin S | ≤0.03–1.0 | 0.5 | 1.0 |

| Penicillin I | 0.06–2.0 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Penicillin R | 0.06–1.0 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Grepafloxacin | |||

| Penicillin S | ≤0.03–1.0 | 0.125 | 0.5 |

| Penicillin I | ≤0.03–0.5 | 0.125 | 0.5 |

| Penicillin R | ≤0.03–0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| Trovafloxacin | |||

| Penicillin S | 0.03–0.5 | 0.125 | 0.25 |

| Penicillin I | 0.016–1.0 | 0.125 | 0.25 |

| Penicillin R | 0.03–0.25 | 0.125 | 0.25 |

| Amoxicillin | |||

| Penicillin S | ≤0.008–0.25 | 0.016 | 0.06 |

| Penicillin I | 0.016–4.0 | 0.125 | 1.0 |

| Penicillin R | 0.5–8.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 |

| Cefuroxime | |||

| Penicillin S | ≤0.008–2.0 | 0.03 | 0.25 |

| Penicillin I | 0.125–8.0 | 0.5 | 2.0 |

| Penicillin R | 0.5–32.0 | 8.0 | 16.0 |

| Azithromycin | |||

| Penicillin S | ≤0.008–>128.0 | 0.125 | 0.5 |

| Penicillin I | ≤0.008–>128.0 | 0.125 | >128.0 |

| Penicillin R | 0.03–>128.0 | 4.0 | >128.0 |

| Clarithromycin | |||

| Penicillin S | ≤0.008–>128.0 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| Penicillin I | ≤0.008–>128.0 | 0.03 | 32.0 |

| Penicillin R | 0.008–>128.0 | 2.0 | >128.0 |

Strains with ciprofloxacin MICs of ≤4.0 μg/ml.

S, susceptible; I, intermediate; R, resistant.

Against 28 strains, for which ciprofloxacin MICs were ≥8 μg/ml, gemifloxacin had the lowest MICs (0.03 to 1.0 μg/ml; MIC at which 90% of isolates are inhibited [MIC90], 0.5 μg/ml), compared with MICs ranging between 0.25 and >32.0 μg/ml (MIC90s, 4.0 to >32.0 μg/ml) for the other quinolones, with trovafloxacin, grepafloxacin, sparfloxacin, and levofloxacin, in ascending order, giving the next lowest MICs (Table 2). Mechanisms of quinolone resistance are presented in Tables 3 and 4. As can be seen, increased quinolone MICs were associated with mutations in the quinolone resistance-determining region of ParC, GyrA, ParE, and/or GyrB. Mutations in ParC were S79-F or -Y, D83-N, R95-C, or K137-N. Mutations in GyrA were S81-A, -C, -F, or -Y; E85-K; or S114-G. Twenty-one strains had a mutation in ParE at D435-N or I460-V. Only two strains had a mutation in GyrB at D435-N or E474-K. Twenty-one strains had a total of three or four mutations in the quinolone resistance-determining regions of ParC, GyrA, ParE, and GyrB (Table 3). Among these 21 strains, all were resistant to ciprofloxacin (MICs, ≥8 μg/ml), with increased MICs (NCCLS) for levofloxacin (MICs, ≥4 μg/ml) and sparfloxacin (MICs, ≥1 μg/ml); for 20 of these strains grepafloxacin MICs were increased (≥1 μg/ml), and for 11 of the strains trovafloxacin MICs were increased (≥2 μg/ml). However, gemifloxacin MICs were ≤0.5 μg/ml for 19 of the strains (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Quinolone agar dilution MICs for 28 pneumococcal strains not susceptible to ciprofloxacina

| Quinolone | MIC range (μg/ml) | MIC50 (μg/ml) | MIC90 (μg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gemifloxacin | 0.03–1.0 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 8.0–>32.0 | 16.0 | >32.0 |

| Levofloxacin | 4.0–>32.0 | 16.0 | >32.0 |

| Sparfloxacin | 0.25–>32.0 | 8.0 | 16.0 |

| Grepafloxacin | 0.5–16.0 | 4.0 | 8.0 |

| Trovafloxacin | 0.25–8.0 | 1.0 | 4.0 |

Strains with ciprofloxacin MICs of ≥8.0 μg/ml.

TABLE 3.

Correlation of quinolone MIC and mutation in quinolone-resistant pneumococcal strains

| Strain | MIC (μg/ml) of:

|

Mutation(s) in:

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gemifloxacin | Ciprofloxacin | Levofloxacin | Sparfloxacin | Grepafloxacin | Trovafloxacin | ParC | ParE | GyrA | GyrB | |

| 1 | 0.03 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 2 | S79-F, K137-N | I460-V | S81-F | None |

| 2 | 0.06 | 8 | 4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25 | S79-Y | I460-V | None | None |

| 3 | 0.06 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.25 | D83-N | I460-V | S81-F | None |

| 4 | 0.06 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0.25 | S79-F, K137-N | I460-V | S81-F | None |

| 5 | 0.125 | 8 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 0.25 | R95-C | D435-N | S81-F | None |

| 6 | 0.125 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 2 | S79-Y, K137-N | I460-V | E85-K | None |

| 7 | 0.125 | 8 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | None | I460-V | None | None |

| 8 | 0.125 | 8 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | S79-Y | None | None | None |

| 9 | 0.125 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 1 | S79-Y | None | None | None |

| 10 | 0.125 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 | S79-F | I460-V | S81-C | None |

| 11 | 0.125 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 1 | S79-F | I460-V | S81-F | None |

| 12 | 0.125 | >32 | 16 | 1 | 4 | 1 | S79-F | I460-V | None | D435-N |

| 13 | 0.25 | 16 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 1 | S79-F, K137-N | I460-V | None | E474-K |

| 14 | 0.25 | 16 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 1 | S79-F, K137-N | I460-V | S81-F | None |

| 15 | 0.25 | 16 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 1 | S79-F, K137-N | I460-V | S81-F | None |

| 16 | 0.25 | 16 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | S79-F | I460-V | S81-F | None |

| 17 | 0.25 | 16 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | D83-N | None | S81-F | None |

| 18 | 0.25 | 16 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | S79-F | I460-V | S81-F | None |

| 19 | 0.25 | 16 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | S79-F | I460-V | S81-F | None |

| 20 | 0.25 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | S79-F, K137-N | I460-V | E85-K | None |

| 21 | 0.25 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 1 | S79-F, K137-N | I460-V | S81-F | None |

| 22 | 0.25 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | S79-F | I460-V | S81-Y | None |

| 23 | 0.25 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 8 | 2 | S79-Y | None | S81-A | None |

| 24 | 0.5 | 32 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 4 | S79-F, K137-N | I460-V | S81-F | None |

| 25 | 0.5 | 32 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 4 | D83-G, N91-D | None | S81-F | None |

| 26 | 0.5 | >32 | >32 | >32 | 8 | 4 | S79-F | None | S81-Y | None |

| 27 | 1 | >32 | >32 | >32 | 16 | 8 | S79-Y | I460-V | S81-F | None |

| 28 | 1 | >32 | >32 | >32 | 16 | 8 | D83-G, N91-D | None | S81-F, S114-G | None |

TABLE 4.

Efflux mechanisms in pneumococci not susceptible to ciprofloxacin

| Strain | Dilution decreasea with:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gemifloxacin | Ciprofloxacin | Levofloxacin | Sparfloxacin | Grepafloxacin | Trovafloxacin | |

| 1 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| 2 | 8 | |||||

| 3 | ||||||

| 4 | ||||||

| 5 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | ||

| 6 | 2 | |||||

| 7 | 2 | 4 | 2 | |||

| 8 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| 9 | 4 | 8 | ||||

| 10 | 2 | |||||

| 11 | 2 | 16 | 4 | |||

| 12 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | ||

| 13 | 2 | |||||

| 14 | ||||||

| 15 | ||||||

| 16 | 2 | 4 | ||||

| 17 | 2 | 4 | ||||

| 18 | 2 | |||||

| 19 | 2 | |||||

| 20 | 2 | |||||

| 21 | 2 | |||||

| 22 | 2 | |||||

| 23 | 2 | 8 | 2 | |||

| 24 | 2 | |||||

| 25 | 2 | 4 | 2 | |||

| 26 | 2 | 4 | 2 | |||

| 27 | ||||||

| 28 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 2 | ||

Number of dilutions decrease after incubation with reserpine (see Materials and Methods).

In the presence of reserpine, ciprofloxacin MICs were lower (2 to 16 times) for 23 strains, gemifloxacin MICs were lower (2 to 4 times) for 13 strains, levofloxacin MICs were lower (2 to 4 times) for 7 strains, grepafloxacin MICs were lower (2 times) for 3 strains, and sparfloxacin MICs were lower (2 times) for 1 strain, suggesting that an efflux mechanism contributed to the raised MICs in some cases. Five, five, and three strains had an efflux mechanism to two, three, and four drugs, respectively (Table 4).

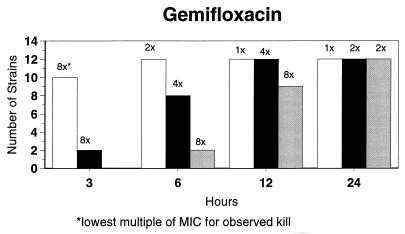

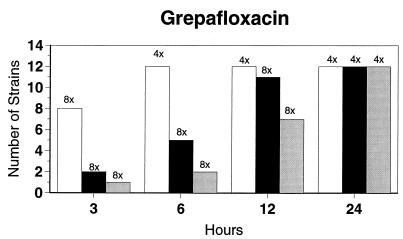

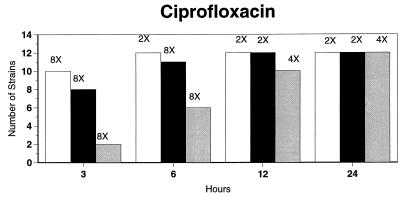

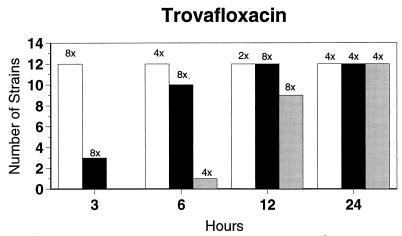

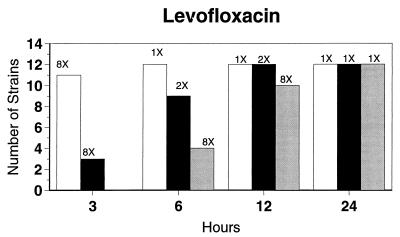

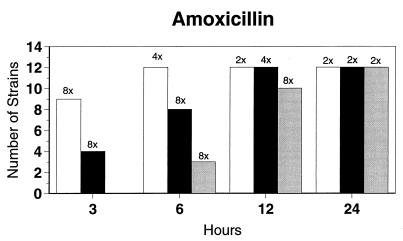

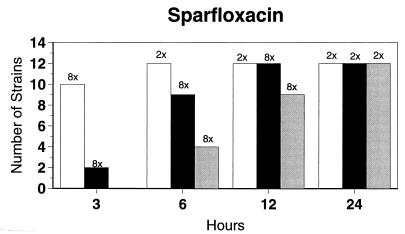

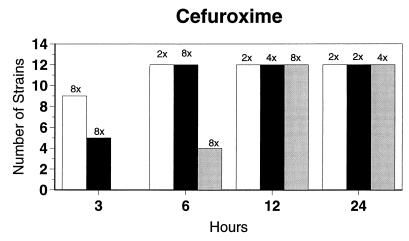

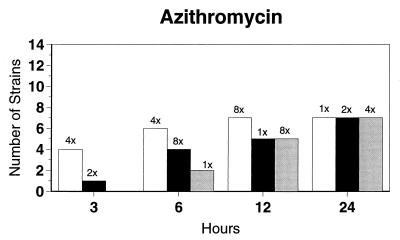

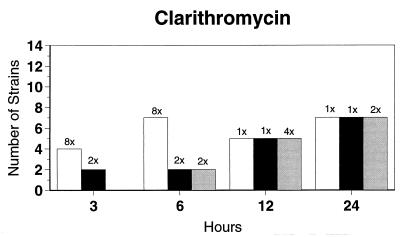

Broth microdilution MIC results for the 12 strains tested by time-kill studies are presented in Table 5. Microdilution MICs were all within one dilution of agar MICs. For the two quinolone-resistant strains (both penicillin susceptible), gemifloxacin broth microdilution MICs were 0.5 and 0.25 μg/ml, respectively. The time-kill results (Fig. 1) showed that levofloxacin at the MIC, gemifloxacin and sparfloxacin at two times the MIC, and ciprofloxacin, grepafloxacin, and trovafloxacin at four times the MIC were bactericidal after 24 h. Various degrees of 90 and 99% killing by all quinolones were detected after 3 h. Gemifloxacin and trovafloxacin were both bactericidal at two times the MIC for the two quinolone-resistant pneumococcal strains; other quinolones were bactericidal against these two strains after 24 h at the MIC, two times the MIC, or four times the MIC. Gemifloxacin was uniformly bactericidal after 24 h at ≤0.5 μg/ml. Amoxicillin at two times the MIC and cefuroxime at four times the MIC were bactericidal after 24 h, with some degree of killing at earlier time points. By contrast, macrolides gave slower killing against the seven susceptible strains tested, with 99.9% killing of all strains at two to four times the MIC after 24 h.

TABLE 5.

Microdilution MICs for 12 pneumococcal strains tested by time-kill studies

| Drug | MIC (μg/ml) for straina:

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (S) | 2 (S) | 3 (S)b | 4 (S)b | 5 (I) | 6 (I) | 7 (I) | 8 (I) | 9 (R) | 10 (I) | 11 (R) | 12 (R) | |

| Penicillin G | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.5 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| Gemifloxacin | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.03 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.03 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.03 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 1 | 0.5 | 32 | 32 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Levofloxacin | 2 | 1 | 32 | 32 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Sparfloxacin | 0.125 | 0.25 | 32 | 16 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| Grepafloxacin | 0.06 | 0.06 | 16 | 8 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.25 |

| Trovafloxacin | 0.06 | 0.06 | 8 | 4 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.125 |

| Amoxicillin | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.03 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.06 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Cefuroxime | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 2 | 0.5 | 4 | 2 |

| Azithromycin | 0.008 | 0.06 | >64 | 0.125 | >64 | 0.03 | 0.125 | 0.125 | >64 | >64 | 0.125 | >64 |

| Clarithromycin | 0.008 | 0.03 | >64 | 0.03 | 32 | 0.008 | 0.016 | 0.03 | >64 | >64 | 0.03 | >64 |

S, penicillin susceptible; I, penicillin intermediate; R, penicillin resistant.

Quinolone resistant.

FIG. 1.

Time-kill studies of 12 strains, showing the number of strains exhibiting a decrease of 1 (open bars), 2 (solid bars), or 3 (shaded bars) log10 CFU/ml compared to 0 h. The lowest multiple of the MIC that showed the observed kill for the maximum of strains is indicated above each bar. Note that only seven strains were tested with macrolides by time-kill methods, as five strains were macrolide resistant.

For the five quinolone-susceptible strains tested for PAE, MICs obtained by microdilution were similar to those obtained by agar dilution, with gemifloxacin having MICs of 0.25 μg/ml against the quinolone-resistant strain (the MICs of other quinolones were 4 to 32 μg/ml). PAEs (in hours; at 10 times the MIC) for the five quinolone-susceptible strains ranged between 0.4 and 1.6 for gemifloxacin, 0.5 and 1.5 for ciprofloxacin, 0.9 and 2.3 for levofloxacin, 0.3 and 1.1 for sparfloxacin, 0.3 and 0.9 for grepafloxacin, and 1.3 and 3.0 for trovafloxacin. At five times the MIC, PAEs (hours) for the quinolone-resistant strain were 0.9 (gemifloxacin), 3.7 (ciprofloxacin), 1.3 (levofloxacin), 1.5 (sparfloxacin), 1.5 (grepafloxacin), and 1.3 trovafloxacin. PAEs (hours) for nonquinolone compounds at 10 times the MIC in all six strains ranged between 0.3 and 5.8 (amoxicillin), 0.8 and 2.9 (cefuroxime), 1.3 and 3.0 (azithromycin), and 1.8 and 4.5 (clarithromycin).

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have shown gemifloxacin to be 32- to 64-fold more active than ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, sparfloxacin, and trovafloxacin against methicillin-susceptible and -resistant Staphylococcus aureus, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis, and S. pneumoniae. Gemifloxacin was also highly active against most members of the family Enterobacteriaceae, with activity more potent than those of sparfloxacin and ofloxacin and comparable to that of ciprofloxacin. Gemifloxacin was the most active agent against gram-positive species resistant to other quinolones and glycopeptides. Gemifloxacin has variable activity against anaerobes and is very active against the gram-positive group (5, 12, 19).

In our study, gemifloxacin had the lowest quinolone MICs against all pneumococcal strains tested, followed by trovafloxacin, grepafloxacin, sparfloxacin, levofloxacin, and ciprofloxacin. MICs were similar to those described previously (5, 12, 19). Additionally, gemifloxacin had significantly lower MICs against highly quinolone-resistant pneumococci, irrespective of quinolone resistance mechanism. This was the case for mutants with mutations in both parC and gyrA, strains which have previously been shown to be highly resistant to other quinolones, as well as for strains with an efflux mechanism (4, 20). MICs of nonquinolone agents were similar to those described previously (13, 14, 23).

Gemifloxacin also showed good killing against the 12 strains tested, including the two quinolone-resistant strains. At ≤0.5 μg/ml, gemifloxacin was bactericidal against all 12 strains. Killing rates relative to MICs were similar to those of other quinolones, with significant killing occurring earlier than with β-lactams and macrolides. Kill kinetics of quinolone and nonquinolone compounds in our study were similar to those described previously (21, 24, 29). Gemifloxacin also gave, together with the other quinolones tested, significant PAEs against all six strains tested, including the one quinolone-resistant strain. The higher ciprofloxacin PAE at both exposure concentrations should be interpreted together with an MIC of 32 μg/ml: concentrations of 5 and 10 times the MIC are not clinically achievable. PAE values for quinolones and macrolides were similar to those described previously (11, 15, 27, 28).

In summary, gemifloxacin was the most potent quinolone tested by MIC and time-kill studies against both quinolone-susceptible and -resistant pneumococci and, similar to other quinolones, gave PAEs against quinolone-susceptible strains. The incidence of quinolone-resistant pneumococci is presently very low. However, this situation may change with the introduction of broad-spectrum quinolones into clinical practice, and in particular in the pediatric population, leading to selection of quinolone-resistant strains (7). Additionally, if the incidence of quinolone-resistant pneumococci increases, gemifloxacin will be a well-placed therapeutic option. Gemifloxacin is a promising new antipneumococcal agent, irrespective of the strains' susceptibility to quinolones and other agents. Clinical studies will be necessary in order to validate this hypothesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a grant from SmithKline Beecham Laboratories Collegeville, Pa.

We thank D. Felmingham and R. Grüneberg (GR Micro, London, United Kingdom) for kind provision of quinolone-resistant pneumococci from their Alexander Project collection.

REFERENCES

- 1.Appelbaum P C. Antimicrobial resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae—an overview. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:77–83. doi: 10.1093/clinids/15.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Block S, Harrison C J, Hedrick J A, Tyler R D, Smith R A, Keegan E, Chartrand S A. Penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in acute otitis media: risk factors, susceptibility patterns and antimicrobial management. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1995;14:751–759. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199509000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breiman R F, Butler J C, Tenover F C, Elliott J A, Facklam R R. Emergence of drug-resistant pneumococcal infections in the United States. JAMA. 1994;271:1831–1835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brenwald N P, Gill M J, Wise R. Prevalence of a putative efflux mechanism among fluoroquinolone-resistant clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2032–2035. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.8.2032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cormican M G, Jones R N. Antimicrobial activity and spectrum of LB 20304, a novel fluoronaphthyridone. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:204–211. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.1.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Craig W A, Gudmundsson S. Postantibiotic effect. In: Lorian V, editor. Antibiotics in laboratory medicine. Baltimore, Md: Williams and Wilkins; 1996. pp. 296–329. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies T A, Pankuch G A, Dewasse B E, Jacobs M R, Appelbaum P C. In vitro development of resistance to five quinolones and amoxicillin-clavulanate in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1177–1182. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.5.1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doern G V, Brueggemann A, Holley H P, Rauch A M. Antimicrobial resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae isolated from outpatients in the United States during the winter months of 1994 to 1995: results of a 30-center national surveillance study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1208–1213. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.5.1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedland I R, Istre G S. Management of penicillin-resistant pneumococcal infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992;11:433–435. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199206000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedland I R, McCracken G H., Jr Management of infections caused by antibiotic-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:377–382. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199408113310607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuursted K, Knudsen J D, Petersen M B, Poulsen R K, Rehm D. Comparative study of bactericidal activities, postantibiotic effects, and effects on bacterial virulence of penicillin G and six macrolides against Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:781–784. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.4.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hohl A F, Frei R, Pünter V, von Graevenitz A, Knapp C, Washington J, Johnson D, Jones R N. International multicenter investigation of LB20304, a new fluoronaphthyridone. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1998;4:280–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1998.tb00057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobs M R. Treatment and diagnosis of infections caused by drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:119–127. doi: 10.1093/clinids/15.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobs M R, Appelbaum P C. Antibiotic-resistant pneumococci. Rev Med Microbiol. 1995;6:77–93. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Licata L, Smith C E, Goldschmidt R M, Barrett J F, Frosco M. Comparison of the postantibiotic and postantibiotic sub-MIC effects of levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin on Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:950–955. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDougal L K, Facklam R, Reeves M, Hunter S, Swenson J M, Hill B C, Tenover F C. Analysis of multiply antimicrobial-resistant isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae from the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:2176–2184. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.10.2176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munoz R, Musser J M, Crain M, Briles D E, Marton A, Parkinson A J, Sorensen U, Tomasz A. Geographic distribution of penicillin-resistant clones of Streptococcus pneumoniae: characterization by penicillin-binding protein profile, surface protein A typing, and multilocus enzyme analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:112–118. doi: 10.1093/clinids/15.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. 3rd ed. 1997. Approved standard M7-A4. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oh J-I, Paek K-S, Ahn M-J, Kim M-Y, Hong C Y, Kim I-C, Kwak J-H. In vitro and in vivo evaluations of LB20304, a new fluoronaphthyridone. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1564–1568. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.6.1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pan X S, Ambler J, Mehtar S, Fisher L M. Involvement of topoisomerase IV and DNA gyrase as ciprofloxacin targets in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2321–2326. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.10.2321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pankuch G A, Jacobs M R, Appelbaum P C. Study of comparative antipneumococcal activities of penicillin G, RP 59500, erythromycin, sparfloxacin, ciprofloxacin and vancomycin by using time-kill methodology. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2065–2072. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.9.2065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pankuch G A, Jacobs M R, Appelbaum P C. Activity of CP 99,219 compared to DU-6859a, ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, levofloxacin, lomefloxacin, tosufloxacin, sparfloxacin and grepafloxacin against penicillin-susceptible and -resistant pneumococci. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1995;35:230–232. doi: 10.1093/jac/35.1.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pankuch G A, Jacobs M R, Appelbaum P C. Comparative activity of ampicillin, amoxycillin, amoxycillin/clavulanate and cefotaxime against 189 penicillin-susceptible and -resistant pneumococci. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1995;35:883–888. doi: 10.1093/jac/35.6.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pankuch G A, Lichtenberger C, Jacobs M R, Appelbaum P C. Antipneumococcal activities of RP 59500 (quinupristin/dalfopristin), penicillin G, erythromycin, and sparfloxacin determined by MIC and rapid time-kill methodologies. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1653–1656. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.7.1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spangler S K, Jacobs M R, Appelbaum P C. Susceptibilities of penicillin-susceptible and -resistant strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae to RP 59500, vancomycin, erythromycin, PD 131628, sparfloxacin, temafloxacin, Win 57273, ofloxacin, and ciprofloxacin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:856–859. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.4.856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spangler S K, Jacobs M R, Pankuch G A, Appelbaum P C. Susceptibility of 170 penicillin-susceptible and -resistant pneumococci to six oral cephalosporins, four quinolones, desacetylcefotaxime, Ro 23-9424 and RP 67829. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1993;31:273–280. doi: 10.1093/jac/31.2.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spangler S K, Lin G, Jacobs M R, Appelbaum P C. Postantibiotic effect of sanfetrinem compared with those of six other agents against 12 penicillin-susceptible and -resistant pneumococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2173–2176. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.10.2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spangler S K, Lin G, Jacobs M R, Appelbaum P C. Postantibiotic effect and postantibiotic sub-MIC effect of levofloxacin compared to those of ofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, azithromycin, and clarithromycin against 20 pneumococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1253–1255. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.5.1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Visalli M A, Jacobs M R, Appelbaum P C. MIC and time-kill study of DU-6859a, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, sparfloxacin, cefotaxime, imipenem, and vancomycin against nine penicillin-susceptible and -resistant pneumococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:362–366. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.2.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]