Key Points

Participants who identified as female and Black reported more thorough discussions of dialysis than transplant.

Participants with low incomes and education reported more thorough discussions of dialysis than transplant.

Keywords: clinical nephrology, chronic kidney disease, dialysis, renal replacement therapy, transplant

Introduction

Patients with CKD often transition to RRT unprepared, leaving little time to consider kidney transplantation before initiating dialysis (1). Engaging patients in shared and informed decision-making (SDM) about RRT before they initiate dialysis is widely advocated (2–4), because SDM is associated with improved adherence, increased knowledge, and overall better health outcomes (5,6). Early discussions of RRT options and their relative advantages and disadvantages are critical to effective SDM, yet they may not occur equitably among groups, particularly among those with historically poorer access to kidney transplantation, such as racial and ethnic minorities and women (7,8). We assessed patient perceptions of RRT discussions among a diverse sample of patients with advanced CKD who had not yet initiated RRT. Our primary objective was to identify potential disparities in patients’ perceived completeness of discussions among those who reported having discussions with their nephrologist.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis of data obtained from a subset of participants who participated in the Talking About Living Kidney Donation (TALK) trial. Among the 130 TALK participants, 82 reported having discussions about RRT with their nephrologist and were asked questions about their perceived completeness of these discussions. TALK was a randomized controlled trial (NCT00932334) completed in 2011 (9). The main trial studied the effectiveness of an education and social worker intervention for improving pursuit of living donor kidney transplantation among individuals receiving care for advanced, progressive CKD at academic and community-based nephrology practices in Baltimore, Maryland. All study protocols were approved by the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and Duke University Institutional Review Boards.

At study enrollment, participants provided sociodemographic information (age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, annual household income, employment, and marital status) and information about their nephrology care (time in nephrology care and frequency of nephrology visits) via a telephone questionnaire administered by trained research staff. We assessed participants’ comorbidity using an adapted version of the Charlson Comorbidity Index (10) and their eGFR by chart review.

We measured participants’ perceived SDM experience by asking questions about the extent and quality of their RRT discussions with nephrologists. We asked participants to assess the extent of their RRT discussions: (1) “To what extent has your kidney doctor explained to you about dialysis?” and (2) “To what extent has your kidney doctor explained to you about transplant? (Not at all, a little, mostly, completely, or don’t know).” We asked participants to assess the quality of their RRT discussions by asking them whether they and their nephrologists discussed how dialysis and transplant could differentially affect: (1) quality of life, (2) life expectancy, (3) finances, (4) their family’s wellbeing, and (5) need for help from family and friends (yes or no). We summed affirmative responses to assess the number of topics discussed, which ranged from 0 (none discussed) to 5 (all discussed).

We described differences in the extent of participants’ RRT discussions and the number of RRT topics participants reported discussing according to their sociodemographic and clinical characteristics using Fisher’s exact tests and Mann–Whitney tests. We also described the proportion of participants who reported they “mostly” or “completely” (versus “a little” or “not at all”) discussed dialysis or transplant among sociodemographic subgroups (i.e., among female and male participants separately, among Black and non-Black participants separately, among participants with less than or equal to high school education and greater than high school education separately, among participants with ≤US$20,000 and >US$20,000 annual household income separately). We report the absolute percent difference between “mostly” or “completely” discussing transplant, and “mostly” or “completely” discussing dialysis within each sociodemographic subgroup. All analyses were performed using R 4.0.2 (R Core Team 2020, Vienna, Austria), and all hypothesis tests were two-sided with no multiple testing adjustment.

Results

Of the 130 participants enrolled in the TALK trial, 82 reported they discussed RRT with their nephrologists. Those reporting they discussed RRT with their nephrologists had a median and interquartile range (IQR) age of 58 (IQR, 50–65) years. Approximately half of participants were Black, female, had a high school education or less, or were retired. A quarter of participants had a yearly household income ≤US$20,000. Participants received nephrology care for a median of 24 (IQR, 12–60) months, and 40% reported visiting their nephrologists at least every 3 months. Their median Charlson Comorbidity Index was 2 (IQR, 1–4), and their median eGFR was 25 (IQR, 20–29) ml/min per 1.73 m2 (Table 1). Those who reported they discussed RRT with their nephrologists were slightly younger (median 58 versus 62 years), but were otherwise not significantly different from those who reported not discussing RRT.

Table 1.

Participant sociodemographic and clinical characteristics by their reported extent of discussions with their nephrologists about dialysis or transplant

| Characteristics | Discussed Dialysis (n=82) | Discussed Transplant (n=82) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Did Not Discuss RRT | Discussed RRT | Not at All/ A Little | Mostly/ Completely | P Value | Not at All/ A Little | Mostly/ Completely | P Value | |

| (n=130) | (n=48) | (n=82) | (n=31) | (n=51) | (n=47) | (n=35) | |||

| Age, yr, median (IQR) | 60 (52–65) | 62 (58–66) | 58 (50–65) | 60 (51–65) | 56 (51–65) | 0.44 | 59 (52–66) | 56 (48–61) | 0.11 |

| Sex | 0.17 | <0.01 | |||||||

| Female | 78 (60) | 31 (65) | 47 (57) | 21 (68) | 26 (51) | 34 (72) | 13 (37) | ||

| Male | 52 (40) | 17 (35) | 35 (43) | 10 (32) | 25 (49) | 13 (28) | 22 (63) | ||

| Race and ethnicity | 0.07 | 0.51 | |||||||

| Black | 62 (48) | 19 (40) | 43 (52) | 12 (39) | 31 (61) | 23 (49) | 20 (57) | ||

| Not Black | 68 (52) | 29 (60) | 39 (48) | 19 (61) | 20 (39) | 24 (51) | 15 (43) | ||

| Education | 0.01 | 0.37 | |||||||

| High school or less | 64 (49) | 25 (52) | 39 (48) | 9 (29) | 30 (59) | 20 (43) | 19 (54) | ||

| Some college or more | 66 (51) | 23 (48) | 43 (52) | 22 (71) | 21 (41) | 27 (57) | 16 (46) | ||

| Income, US$ | 0.11 | 0.29 | |||||||

| ≤20,000 | 35 (27) | 14 (29) | 21 (26) | 4 (13) | 17 (33) | 14 (30) | 7 (20) | ||

| > 20,000 | 86 (66) | 33 (69) | 53 (66) | 23 (74) | 30 (59) | 27 (57) | 26 (74) | ||

| Refused to answer/don’t know | 9 (7) | 1 (2) | 8 (10) | 4 (13) | 4 (8) | 6 (13) | 2 (6) | ||

| Employment | 0.50 | 0.66 | |||||||

| Not retired | 64 (49) | 20 (42) | 44 (54) | 15 (48) | 29 (57) | 24 (51) | 20 (57) | ||

| Retired | 66 (51) | 28 (58) | 38 (46) | 16 (52) | 22 (43) | 23 (49) | 15 (43) | ||

| Married/living with partner | 0.10 | 0.48 | |||||||

| Yes | 79 (61) | 25 (52) | 54 (66) | 24 (77) | 30 (59) | 29 (62) | 25 (71) | ||

| eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2), median (IQR)a | 26 (21–30) | 28 (22–33) | 25 (20–29) | 27 (24–30) | 21 (20–28) | 0.11 | 26 (21–29) | 22 (20–30) | 0.63 |

| CKD stagea | 0.57 | 0.82 | |||||||

| Stage 2 (eGFR ≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | ||

| Stage 3a (eGFR ≥45 to 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 1 (3) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | ||

| Stage 3b (eGFR ≥30 to 45 ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 19 (15) | 11 (23) | 8 (10) | 5 (16) | 3 (6) | 4 (9) | 4 (11) | ||

| Stage 4 (eGFR ≥15 to 30 ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 55 (42) | 20 (42) | 35 (43) | 12 (39) | 23 (45) | 21 (45) | 14 (40) | ||

| Stage 5 (eGFR <15 ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 6 (5) | 1 (2) | 5 (6) | 2 (6) | 3 (6) | 2 (4) | 3 (9) | ||

| Missing | 47 (36) | 16 (33) | 31 (38) | 11 (35) | 20 (39) | 19 (40) | 12 (34) | ||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, median (IQR) | 2 (1–4) | 2 (2–4) | 2 (1–4) | 2 (0–3) | 3 (2–5) | 0.02 | 2 (0–4) | 2 (1–5) | 0.65 |

| Diabetes, yes | 76 (58) | 28 (58) | 48 (59) | 16 (52) | 32 (63) | 0.36 | 27 (57) | 21 (60) | >0.99 |

| Time in nephrology care, months, median (IQR) | 24 (12–48) | 24 (10–36) | 24 (12–60) | 33 (14–84) | 24 (12–48) | 0.14 | 24 (12–78) | 24 (12–48) | 0.58 |

| Frequency of nephrology visits | <0.01 | 0.01 | |||||||

| At least once a month | 18 (14) | 2 (4) | 16 (20) | 1 (3) | 15 (29) | 5 (11) | 11 (31) | ||

| At least every 2 months | 12 (9) | 2 (4) | 10 (12) | 3 (10) | 7 (14) | 5 (11) | 5 (14) | ||

| At least every 3 months | 59 (45) | 26 (54) | 33 (40) | 11 (35) | 22 (43) | 17 (36) | 16 (46) | ||

| At least every 6 months | 26 (20) | 11 (23) | 15 (18) | 13 (42) | 2 (4) | 14 (30) | 1 (3) | ||

| Once a year | 9 (7) | 4 (8) | 5 (6) | 3 (10) | 2 (4) | 3 (6) | 2 (6) | ||

| Whenever there’s a problem | 3 (2) | 1 (2) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | ||

| Refused to answer/don’t know | 3(2) | 2 (4) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | ||

IQR, interquartile range.

Among n=51 participants with available data.

Over half (62%) of participants reported that they “mostly” or “completely” discussed dialysis, whereas fewer than half (43%) reported they “mostly” or “completely” discussed transplant. Both transplant and dialysis were “mostly” or “completely” discussed by 41% of participants. The extent of participants’ discussions with their nephrologists about dialysis or transplant varied across sociodemographic groups and by clinical characteristics. Participants who “mostly” or “completely” discussed dialysis with their nephrologists tended to have less education, report more frequent nephrology visits, and have a higher median Charlson Comorbidity Index. Participants who “mostly” or “completely” discussed transplant tended to be male and report more frequent nephrology visits (Table 1).

Overall, only half of participants reported they discussed how dialysis and transplant would differentially affect their quality of life (50%), and fewer than half discussed effects on their length of life (34%), need for help from family and friends (29%), their family’s wellbeing (28%), and their finances (13%). Over a third (38%) of participants discussed none of these topics, whereas only 7% discussed all five. The median number of topics discussed did not differ by sociodemographic groups. Participants who reported visiting their nephrologist at least once a month discussed more topics (median, 2; IQR, 1–4) than those who reported visiting their nephrologist less frequently, for example, at least every 6 months (median, 0; IQR, 0–1) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Median number of topics (range 0–5) pertaining to differences between dialysis and transplant that participants reported discussing with their nephrologists

| Characteristics | Number of Topics Discussed | |

|---|---|---|

| Median (Interquartile Range) | P Value | |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||

| Sex | 0.12 | |

| Female | 1 (0–2) | |

| Male | 1 (0–4) | |

| Race and ethnicity | 0.20 | |

| Black | 1 (0–4) | |

| Not Black | 1 (0–3) | |

| Education | 0.21 | |

| High school or less | 1 (0–4) | |

| Some college or more | 1 (0–2) | |

| Income, US$ | 0.25 | |

| ≤20,000 | 1 (0–1) | |

| >20,000 | 1 (0–3) | |

| Refused to answer/don’t know | 1 (0–2) | |

| Employment | 0.53 | |

| Not retired | 1 (0–3) | |

| Retired | 1 (0–3) | |

| Clinical characteristics | ||

| CKD stage | 0.63 | |

| Stage 2 (eGFR ≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 4 (4–4) | |

| Stage 3a (eGFR ≥45 to 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 2 (1–3) | |

| Stage 3b (eGFR ≥30 to 45 ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 0 (0–2) | |

| Stage 4 (eGFR ≥15 to 30 ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 1 (0–3) | |

| Stage 5 (eGFR <15 ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 1 (1–2) | |

| Missing | 1 (0–3) | |

| Diabetes | 0.73 | |

| Yes | 1 (0–3) | |

| No | 1 (0–3) | |

| Frequency of nephrology visits | 0.01 | |

| At least once a month | 2 (1–4) | |

| At least every 2 months | 2 (0–4) | |

| At least every 3 months | 1 (0–3) | |

| At least every 6 months | 0 (0–1) | |

| Once a year | 0 (0–1) | |

| Whenever there’s a problem | 0 (0–0) | |

| Don’t know | 0 (0–0) | |

IQR, interquartile range.

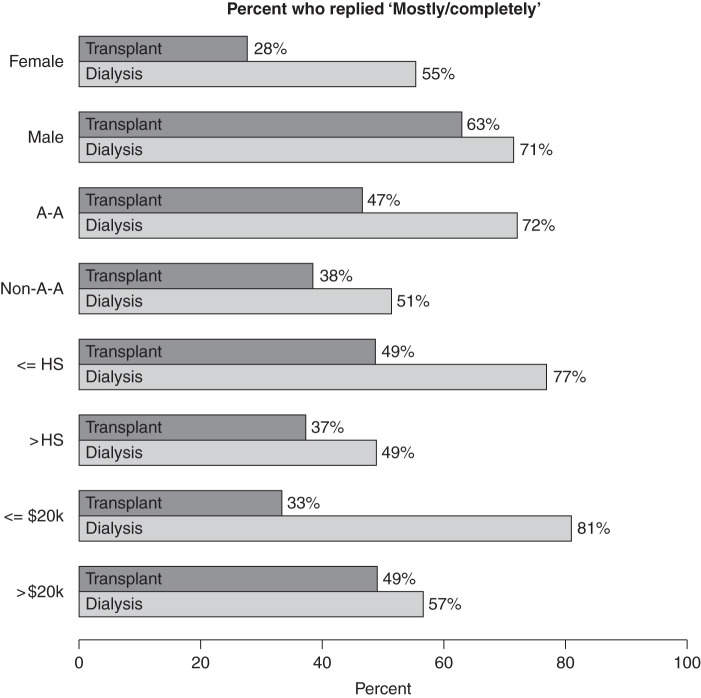

Within sociodemographic subgroups, the difference between the proportion of participants who thoroughly discussed dialysis versus the proportion who thoroughly discussed transplant was greatest among individuals with an annual income ≤US$20,000 (48% difference), followed by those with high school or less education (28% difference), females (27% difference), and Black participants (25% difference). In contrast, there was a minimal difference among those with at least some college education (12% difference), non-Black participants (13% difference), males (8% difference), and those with an annual income >US$20,000 (8% difference) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Percentage of participants who reported they “mostly” or “completely” (versus “a little” or “not at all”) discussed dialysis or transplant by sociodemographic groups, among participants who discussed RRT (n=82). A-A, Black; HS, high school.

Discussion

Among a diverse group of individuals with advanced CKD who had not yet initiated RRT, we found that individuals with low income and education and participants who identified as female and Black reported more extensive discussions of dialysis than transplant. Fewer than half of participants reported they “mostly” or “completely” discussed both treatments with their nephrologists, and participants were more likely to report they discussed both treatments if they identified as male (versus female). Few participants discussed how transplant and dialysis might differentially affect their quality of life, life expectancy, finances, or need for help from family and friends.

Without early discussions that effectively present all options for RRT and their differences, patients cannot engage in SDM and are less prepared to make treatment decisions that align with their values. We found that more participants reported thorough dialysis discussions than reported thorough transplant discussions, suggesting patients may not have equal opportunities to consider transplant as a treatment before they develop kidney failure (11,12). Differences in the extent of discussions about dialysis and transplant among groups that have poorer access to kidney transplants (e.g., Black patients, female patients, and individuals with a low income) suggest early patient-physician discussions about RRT options may be a modifiable contributor to inequities in kidney transplants.

Among all study participants, we found that discussions touched on few differences in key patient-centered aspects of treatment between dialysis and transplantation. This finding is in line with prior studies that have documented low awareness of CKD among primary care patients at risk for CKD progression and poor CKD-related discussion quality (13,14). Therefore, greater emphasis on effective SDM in nephrology care is needed to address these important gaps in patient-provider communication that exist at earlier stages of CKD care.

We conducted this descriptive analysis among a small sample of participants from a single geographic region, which may limit the generalizability of our findings. Our data were collected in 2011, and recent policies advocating improved SDM in kidney care, such as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services' Kidney Care Choices Model, may impact how nephrologists currently discuss RRT with their patients (4). In recent years, greater emphasis has also been placed on discussions about conservative care (15), and these discussions are not captured in this study. Nonetheless, we are unaware of other studies examining early RRT discussions as potential determinants of kidney transplant disparities. Our findings highlight the need to examine SDM practices more closely, and to study their potential contributions to disparities in transplant among different demographic subgroups among the general public.

Disclosures

D. Mohottige reports having other interests/relationships as an National Kidney Foundation Health Equity Advisory Committee member. L.E. Boulware reports receiving honoraria from Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program and various universities for visiting professorships; reports being a scientific advisor or member of the Association for Clinical and Translational Science, Journal of the American Medical Association Editorial Board, Journal of the American Medical Association Network Online Editorial Board, and Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars National Advisory Committee. L. McElroy reports having consultancy agreements with, and receiving honoraria from, Osaka Pharmaceuticals; reports receiving research funding from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities under Award Number U54MD012530 and a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development Award; reports being a scientific advisor or member of the Editorial Boards of the Annals of Surgery Open and Clinical Transplantation. P.L. Ephraim reports having consultancy agreements with Stony Run Consulting. S. Peskoe reports having other interests/relationships as a Journal of the American Medical Association Network Open Statistical Reviewer. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This work was funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration grant R39OT07537 and the National Institute on Aging grant K01AG070284 (to N.D.).

Acknowledgments

The funders had no role in the conceptualization, design, conduct, or interpretation of the study.

Footnotes

See related editorial, “A Critical Role for Shared Decision-Making about Referral and Evaluation for Kidney Transplant,” on pages 14–16.

Author Contributions

T. Barrett, L. Boulware, and P. Ephraim conceptualized the study; T. Barrett, L. Boulware, C. Davenport, P. Ephraim, and S. Peskoe were responsible for the formal analysis; T. Barrett wrote the original draft; L. Boulware, C. Davenport, N. DePasquale, P. Ephraim, L. McElroy, D. Mohottige, and S. Peskoe reviewed and edited the manuscript.

References

- 1.Hassan R, Akbari A, Brown PA, Hiremath S, Brimble KS, Molnar AO: Risk factors for unplanned dialysis initiation: A systematic review of the literature. Can J Kidney Health Dis 6: 2054358119831684, 2019. 10.1177/2054358119831684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Working Group . KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guidelines for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Available at https://kdigo.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/KDIGO_2012_CKD_GL.pdf. Accessed June 1, 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Department of Health and Human Services : Advancing American kidney health, 2019. Available at: https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/private/pdf/262046/AdvancingAmericanKidneyHealth.pdf. Accessed June 1, 2021

- 4.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services : Kidney Care Choices (KCC) Model. Available at: https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/kidney-care-choices-kcc-model. Accessed June 1, 2021.

- 5.Shay LA, Lafata JE: Where is the evidence? A systematic review of shared decision making and patient outcomes. Med Decis Making 35: 114–131, 2015. 10.1177/0272989X14551638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hughes TM, Merath K, Chen Q, Sun S, Palmer E, Idrees JJ, Okunrintemi V, Squires M, Beal EW, Pawlik TM: Association of shared decision-making on patient-reported health outcomes and healthcare utilization. Am J Surg 216: 7–12, 2018. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2018.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Purnell TS, Luo X, Cooper LA, Massie AB, Kucirka LM, Henderson ML, Gordon EJ, Crews DC, Boulware LE, Segev DL: Association of race and ethnicity with live donor kidney t ransplantation in the United States From 1995 to 2014. JAMA 319: 49–61, 2018. 10.1001/jama.2017.19152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carrero JJ, Hecking M, Chesnaye NC, Jager KJ: Sex and gender disparities in the epidemiology and outcomes of chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 14: 151–164, 2018. 10.1038/nrneph.2017.181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boulware LE, Hill-Briggs F, Kraus ES, Melancon JK, Falcone B, Ephraim PL, Jaar BG, Gimenez L, Choi M, Senga M, Kolotos M, Lewis-Boyer L, Cook C, Light L, DePasquale N, Noletto T, Powe NR: Effectiveness of educational and social worker interventions to activate patients’ discussion and pursuit of preemptive living donor kidney transplantation: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Kidney Dis 61: 476–486, 2013. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.08.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katz JN, Chang LC, Sangha O, Fossel AH, Bates DW: Can comorbidity be measured by questionnaire rather than medical record review? Med Care 34: 73–84, 1996. 10.1097/00005650-199601000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jay CL, Dean PG, Helmick RA, Stegall MD: Reassessing preemptive kidney transplantation in the United States: Are we making progress? Transplantation 100: 1120–1127, 2016. 10.1097/TP.0000000000000944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.King KL, Husain SA, Jin Z, Brennan C, Mohan S: Trends in disparities in preemptive kidney transplantation in the United States. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 1500–1511, 2019. 10.2215/CJN.03140319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greer RC, Cooper LA, Crews DC, Powe NR, Boulware LE: Quality of patient-physician discussions about CKD in primary care: A cross-sectional study. Am J Kidney Dis 57: 583–591, 2011. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.08.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy KA, Greer RC, Roter DL, Crews DC, Ephraim PL, Carson KA, Cooper LA, Albert MC, Boulware LE: Awareness and discussions about chronic kidney disease among African-Americans with chronic kidney disease and hypertension: A mixed methods study. J Gen Intern Med 35: 298–306, 2019. 10.1007/s11606-019-05540-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ladin K, Pandya R, Kannam A, Loke R, Oskoui T, Perrone RD, Meyer KB, Weiner DE, Wong JB: Discussing conservative management with older patients with CKD: An interview study of nephrologists. Am J Kidney Dis 71: 627–635, 2018. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.11.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]