Key Points

Older age and delay between clinical onset of lupus nephritis and kidney biopsy were significantly correlated with baseline chronicity index.

Chronicity index and its components, but not activity index, were significantly associated with long-term impairment of kidney function.

Baseline serum creatinine, arterial hypertension, chronic glomerular lesions, and delay in kidney biopsy predicted kidney function impairment.

Keywords: glomerular and tubulointerstitial diseases, lupus nephritis, systemic lupus erythematosus

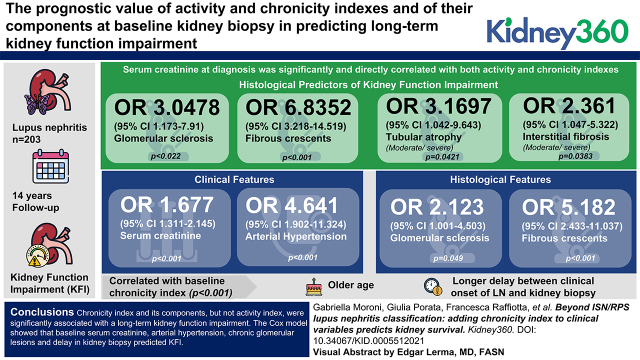

Visual Abstract

Abstract

Background

A renewed interest for activity and chronicity indices as predictors of lupus nephritis (LN) outcome has emerged. Revised National Institutes of Health activity and chronicity indices have been proposed to classify LN lesions, but they should be validated by future studies. The aims of this study were (1) to detect the histologic features associated with the development of kidney function impairment (KFI), and (2) to identify the best clinical-histologic model to predict KFI at time of kidney biopsy.

Methods

Patients with LN who had more than ten glomeruli per kidney biopsy specimen were admitted to the study. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression and Cox proportional hazards models were used to investigate whether activity and chronicity indices could predict KFI development.

Results

Among 203 participants with LN followed for 14 years, correlations were found between the activity index, and its components, and clinical-laboratory signs of active LN at baseline. The chronicity index was correlated with serum creatinine. Thus, serum creatinine was significantly and directly correlated with both activity and chronicity indices. In the multivariate analysis, glomerulosclerosis (OR, 3.05; 95% CI, 1.17 to 7.91; P=0.02) and fibrous crescents (OR, 6.84; 95% CI, 3.22 to 14.52; P<0.001) associated with either moderate/severe tubular atrophy (OR, 3.17; 95% CI, 1.04 to 9.64; P=0.04), or with interstitial fibrosis (OR, 2.36; 95% CI, 1.05 to 5.32; P=0.04), predicted KFI. Considering both clinical and histologic features, serum creatinine (OR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.31 to 2.15; P<0.001), arterial hypertension (OR, 4.64; 95% CI, 1.90 to 11.32; P<0.001), glomerulosclerosis (OR, 2.12; 95% CI, 1.00 to 4.50; P=0.05), and fibrous crescents (OR, 5.18; 95% CI, 2.43 to 11.04; P<0.001) independently predicted KFI. Older age (P<0.001) and longer delay between clinical onset of LN and kidney biopsy (P<0.001) were significantly correlated with baseline chronicity index.

Conclusions

The chronicity index and its components, but not the activity index, were significantly associated with an impairment of kidney function. The Cox model showed that serum creatinine, arterial hypertension, chronic glomerular lesions, and delay in kidney biopsy predicted KFI. These data reinforce the importance of timely kidney biopsy in LN.

Introduction

Lupus nephritis (LN), a common complication of SLE, is associated with a high risk of morbidity and mortality (1). Kidney biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosis and management of LN (2). In 2003, the International Society of Nephrology and Renal Pathology Society (ISN/RPS) updated the histologic classification of LN (3). This classification assessed only the glomerular pathology, but there is growing evidence that tubulointerstitial and vascular lesions are critical to define kidney prognosis. Over the last decades, advances in the therapeutic approach have improved the outcome of LN and mitigated the prognostic differences among histologic classes. At the same time, a renewed interest has arisen in the activity and chronicity indices, which were proposed years ago by Austin et al. (4–6). Several studies pointed out the importance of assessing activity and chronicity changes in all kidney compartments (7–10), and the Working Group for LN proposed to add the activity and chronicity indices to all classes of the ISN/RPS classification to improve the prognostic value of kidney biopsy (11). Among other changes, the working group suggested the separation of fibrinoid necrosis from karyorrhexis, and the association of karyorrhexis with neutrophil infiltration (11). The purposes of this retrospective, long-term study are (1) to define the association between the clinical features at presentation and the components of the activity and chronicity indices at basal kidney biopsy; and (2) to detect the histologic features associated with long-term kidney function impairment (KFI) and to identify the best model to predict KFI, considering both clinical and histologic features at time of kidney biopsy.

Materials and Methods

The inclusion criteria were (1) patients >16 years with SLE classified according to the American College of Rheumatology criteria (12); (2) patients who had kidney biopsy sample–proven LN, performed between January 1984 and December 2019, and with a follow-up >1 year; (3) patients whose kidney biopsy specimen included more than ten glomeruli for analysis by light microscopy and immunofluorescence.

Exclusion criteria comprised patients needing RRT at presentation or patients with inadequate kidney biopsy.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico di Milano (protocol number, 505_2019bis). Before biopsy, all participants signed an informed consent for the scientific use of their anonymized records. This study adheres to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

We considered the histologic diagnosis of LN, classified according to the ISN/RPS criteria, as the baseline of the study (3). Histologic diagnosis was assessed by two experienced nephrologists (G.B. and G.M.) on the basis of light microscopy, immunofluorescence (13), and on electron microscopy, when necessary; disagreements were adjudicated by consensus. As already reported (7), renal biopsies performed before 2002 were reclassified according to the last ISN/RPS classification (3). The activity and chronicity indices were estimated using a semiquantitative scoring system according to Austin et al. (4–6).

For the aims of the study, KFI was defined by a decrease in creatinine clearance (14) of ≥30% over the baseline, confirmed by at least three determinations for at least 3 months. Creatinine clearance was assessed by the Cockcroft and Gault formula (14). Nephrotic syndrome was defined as proteinuria >3.5 g/24 h, with hypoalbuminemia and hypercholesterolemia. Arterial hypertension was defined as systolic BP >140 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP >90 mm Hg in the sitting position (mean of three consecutive measurements). Table 1 reports the categorization of the histologic variables.

Table 1.

Details of histologic assessment

| Histological Features | Staining Intensity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1+ | 2+ | 3+ | |

| Light microscopy a | ||||

| Neutrophil infiltration | Absent | Mild (<25% of glomeruli) |

Moderate (25%–50% of glomeruli) |

Severe (>50% of glomeruli) |

| Endocapillary hypercellularity | ||||

| Hyaline deposits | ||||

| Cellular/fibrocellular crescents | ||||

| Fibrous crescents | ||||

| Fibrinoid necrosis | ||||

| Glomerulosclerosis | ||||

| Interstitial inflammation | Absent | Mild (<25% of the cortex) |

Moderate (25%–50% of the cortex) |

Severe (>50% of the cortex) |

| Interstitial fibrosis | ||||

| Tubular atrophy | ||||

| Immunofluorescence staining b | ||||

| IgG, IgA, IgM, C1q, C3, fibrinogen | Absent | Present | Present | Present |

Staining intensity was scored on a 0 to 3+ scale; deposits were considered present when the intensity was >1.

Specimens were fixed in 5% formalin. Stains used were hematoxylin and eosin, Periodic acid–Schiff, silver methenamine, and Masson trichrome/Acid Fuchsin Orange G.

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded kidney sections incubated with pronase (13).

We re-evaluated the terms “neutrophil infiltration” and “fibrinoid necrosis/karyorrhexis” according to the new proposal for histologic LN classification (11). Therefore, fibrinoid necrosis was considered alone, whereas karyorrhexis had to be associated with neutrophil infiltration. We retrospectively evaluated the immunofluorescence data and classified extraglomerular immune deposits as present or absent. We also specified if the deposits were localized in the tubular basement membrane, interstitial capillary wall, and/or small arteries.

The demographic, clinical, histologic, laboratory, and therapeutic variables, collected from the time of kidney biopsy to the last follow-up, were reported in a database (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical and histologic characteristics of 203 patients with lupus nephritis at kidney biopsy

| Characteristics | All Patients (n=203) | Patients Who Developed KFI (n=39) | Patients Who Did Not Develop KFI (n=164) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Months from SLE to lupus nephritis | 8.06 (0–61.6) | 3.9 (0–49.4) | 8.5 (0–70) | 0.04 |

| Months from renal manifestations to kidney biopsy | 3.12 (0.92–13.01) | 7.9 (1.6–32.6) | 2.6 (0.7–10.7) | 0.04a |

| Female/male, n | 177/26 | 33/6 | 144/20 | 0.59 |

| White/other race or ethnicity, n | 184/19 | 36/3 | 148/16 | 0.69 |

| Age at renal biopsy, yr | 32.4 (24.15–42.52) | 31.3 (24.1–39) | 33.9/24.5–47.6) | 0.35 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dl | 0.9 (0.7–1.4) | 1.5 (1.1–2.4) | 0.8 (0.7–1.2) | <0.001a |

| Creatinine clearance, ml/min | 80.45 (51.6–110.1) | 47 (30.15–74.9) | 88.5 (68.1–112.4) | <0.001a |

| Proteinuria, g/d | 3 (1.9–5) | 4.2 (3–5.6) | 2.9 (1.7–4.9) | 0.009a |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 102 (50) | 32 (82) | 70 (43) | <0.001a |

| ACE inhibitors, n (%) | 160 (79) | 34 (87) | 126 (77) | 0.16 |

| Urinary erythrocytes number per HPF | 11 (3–40) | 15 (4.3–40) | 10 (3–40) | 0.51 |

| Serum C3, mg/dl, (normal values >90 mg/dl) | 59 (46–79) | 56 (47.5–81) | 60 (46–78) | 0.97 |

| Serum C4, mg/dl, (normal values 10–40 mg/dl) | 10 (6–15) | 11 (5–18.3) | 10 (6–15) | 0.65 |

| Hematocrit, % | 34 (29–38) | 30 (28–37) | 34 (30–38) | 0.10 |

| Serum albumin, g/dl | 2.9 (2.4–3.5) | 2.6 (2.3–3.4) | 3 (2.5–3.5) | 0.10 |

| White blood cells, mmc | 5700 (3900–7540) | 6225 (5000–8450) | 5600 (3850–7500) | 0.50 |

| Platelets, µl | 239 (109–304) | 219,500 (175,250–303,750) | 246,000 (183,250–299,750) | 0.31 |

| Ab anti-dsDNA positivity, n (%) | 172 (88) | 32 (87) | 140 (88) | 0.61 |

| Ab anti-phospholipid, n (%) | 44 (23) | 7 (19) | 37 (24) | 0.53 |

| ENA positivity, % e | ||||

| Anti-SM | 23 | 19 | 24 | 0.79 |

| Anti-SSA | 36 | 32 | 36 | 0.89 |

| Anti-SSB | 15 | 16 | 15 | 0.97 |

| Anti-RNP | 28 | 24 | 29 | 0.63 |

| Clinical manifestations, % | ||||

| Skin | 62 | 63 | 61 | 0.92 |

| Arthralgias | 74 | 74 | 74 | 0.99 |

| Serositis | 25 | 33 | 23 | 0.35 |

| Cerebritis | 5 | 10 | 4 | 0.24 |

| Fever | 53 | 56 | 52 | 0.83 |

| Lymphadenopathy | 13 | 13 | 14 | 0.90 |

| Therapy | ||||

| Methylprednisolone pulses, n (%) | 169 (84) | 31 (82) | 138 (85) | 0.48 |

| IST induction, n (%) | 174 (87) | 32 (84) | 142 (88) | 0.45 |

| No-IST/CY/MMF/AZA/CsA/others, n | 25/99/43/19/4/9 | 6/18/3/6/0/5 | 19/81/40/13/4/4 | |

| Maintenance, n (%) | 120 (61) | 15 (40) | 105 (66) | 0.002a |

| No-IST/MMF/AZA/CsA/others, n | 77/71/38/10/1 | 23/9/5/1/0 | 54/62/33/9/1 | |

| Histologic characteristics | ||||

| Histologic class, n (%) | ||||

| II | 2 (0.9) | 0 | 2 (1) | 0.53 |

| III | 45 (22) | 5 (13) | 40 (24) | 0.12 |

| IV | 108 (53) | 26 (67) | 82 (50) | 0.06 |

| V | 48 (24) | 8 (21) | 40 (24) | 0.61 |

| Activity index score, n (%) | 6 (2–9) | 6 (2–9) | 6 (2–9) | 0.80 |

| Activity index >6 | 88 (43) | 17 (44) | 71 (43) | 0.99 |

| Endocapillary hypercellularityb | 133 (66) | 26 (67) | 107 (65) | 0.94 |

| Neutrophil infiltrationb | 153 (75) | 29 (74) | 124 (76) | 0.89 |

| Hyaline deposits/wire loopsb | 105 (52) | 25 (64) | 80 (49) | 0.09 |

| Cellular/fibrocellular crescentsc | 40 (20) | 9 (23) | 31 (19) | 0.56 |

| Fibrinoid necrosis/karyorrhexisc | 71 (35) | 8 (21) | 63 (38) | 0.04a |

| Interstitial inflammationb | 101 (50) | 25 (64) | 76 (46) | 0.05a |

| Chronicity index score, n (%) | 2 (1–3) | 3 (1–7) | 1 (1–3) | <0.001a |

| Chronicity index >2 | 70 (35) | 23 (59) | 47 (29) | <0.001a |

| Glomerulosclerosisc | 28 (14) | 14 (36) | 14 (9) | <0.001a |

| Fibrous crescentsc | 27 (13) | 13 (33) | 14 (9) | <0.001a |

| Tubular atrophyc | 14 (7) | 9 (23) | 5 (3) | <0.001a |

| Interstitial fibrosisc | 20 (10) | 13 (33) | 7 (4) | <0.001a |

| Neutrophil infiltration/karyorrhexisb | 152 (75) | 29 (74) | 123 (75) | 0.97 |

| Fibrinoid necrosisc | 45 (22) | 4 (10) | 41 (25) | 0.05a |

| Extraglomerular immune deposits, n positive (%) d | 95 (47) | 25 (64) | 70 (15) | 0.02a |

| Tubular basement deposits | 71 (35) | 16 (41) | 55 (34) | 0.38 |

| Interstitial capillary wall deposits | 18 (9) | 5 (13) | 13 (8) | 0.33 |

| Vascular deposits | 45 (22) | 15 (39) | 30 (18) | 0.006a |

If not otherwise specified, data are expressed as medians with interquartile ranges. KFI, kidney function impairment; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; HPF, high powered field; Ab, antibody; dsDNA, double-stranded DNA; ENA, extractable nuclear antigen; Anti-SM, anti-Smith autoantibodies; Anti-SSA, anti–Sjögren's-syndrome-related antigen A autoantibodies; Anti-SSB anti–Sjögren's-syndrome-related antigen B autoantibodies, Anti-RNP, anti-Ribonucleoprotein autoantibodies; IST, immunosuppressive therapy; CY, cyclophosphamide; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; AZA, azathioprine; CsA, cyclosporine.

P≤0.05; P values are evaluated with t test or nonparametric Wilcoxon test for independent samples and with chi-squared test between qualitative or dichotomized variables.

Variables were categorized as 0 versus 1+2+3, where 0, represents absent; 1, in <25% of glomeruli, or of interstitial or of tubular cortex; 2, from 25% to 50% of glomeruli, or of interstitial or of tubular cortex; 3, >50% of glomeruli, or of interstitial or of tubular cortex.

All of these variables were categorized as 0+1 versus 2+3.

Patients with extraglomerular immune deposits (%).

Data were not available in 34 patients.

After kidney biopsy, therapy was determined on the basis of histologic and clinical data. Patients were followed by a dedicated team in our unit: they were evaluated 1 month after the diagnosis, then every 2–3 months at 1 year, and every 3–6 months thereafter. At each follow-up visit, clinical, laboratory, and therapeutic data were regularly recorded until the last checkup in December 2020.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) because the distribution of most variables was not normal (according to the Shapiro normality test). For the same reason, the difference of continuous variables between groups was tested using the t test or nonparametric Wilcoxon test for independent samples. The chi-squared test was used to test associations between qualitative or dichotomized variables. The Fisher exact test was used instead of the chi-squared test when expected cell counts were five or less. The Kaplan–Meier estimate was used for survival. Linear multivariate regression of the demographic characteristics was used to determine the predictors of the activity and chronicity indices at baseline kidney biopsy. Cox proportional hazards models, both univariate and multivariate, were used to find the predictors of KFI development over time. The ISN/RPS histologic classes, activity and chronicity indices and all of their components, and clinical features at LN biopsy were tested as predictors of KFI development. Correction for possible confounders, i.e., the calendar year of biopsy, age, sex, and duration of LN before renal biopsy, was considered for all of the models.

Different dichotomizations of ordinal variables, ranging from zero to three, were tested (e.g., 0 versus 1–3, 0–1 versus 2–3) and the best dichotomization, according to its P value in the statistical models, was retained. Activity and chronicity indices were dichotomized according to their median values. The R statistical package has been used for all of the analyses (15).

Results

This study included 203 patients. The median (IQR) age of participants was 32.4 (24.15–42.52) years; 177 (87%) participants were females and 184 were White (91%). The clinical characteristics of the whole group at kidney biopsy are reported in Table 2. The median (IQR) serum creatinine was 0.9 (0.7–1.4) mg/dl, creatinine clearance was 80.45 (51.61–110.1) ml/min. Creatinine clearance was >60 ml/min in 138 (68%) participants, and it was <60 ml/min in 65 (32%) participants. Proteinuria >3.5 g/d and arterial hypertension were observed in 101 and 102 patients (50%), respectively. Most participants had LN class III (n=45; 22%), class IV (n=108; 53%), or class V (n=48; 24%).

The median (IQR) number of glomeruli was 20 (13–25). The median (IQR) activity index score was six (two to nine) and the median (IQR) chronicity index score was two (one to three).

After kidney biopsy, all patients received an induction therapy, which consisted of methylprednisolone pulses in 84% of patients, and the remaining patients were given oral prednisone. Cyclophosphamide or mycophenolate were added in 87% of patients. Maintenance therapy consisted of low-dose prednisone associated with azathioprine, mycophenolate, or cyclosporine in 62% of participants.

Because the treatment regimens used in LN have evolved during the follow-up of the study, in Supplemental Table 1 we reported changes in immunosuppressive therapy that occurred over the two established time spans (period one, years 1984–2001; period two, years 2002–2019). The rate of KFI was significantly higher in the first period (27 out of 94 patients; 29%) compared with the second period (12 out of 109 patients; 11%; P=0.001).

Of the 203 patients, 25 (12%) were lost to follow-up. The remaining 178 participants were followed up regularly and continued to adhere to prescriptions (the comparison between the clinical data at 1 year for these groups is reported in Supplemental Table 2).

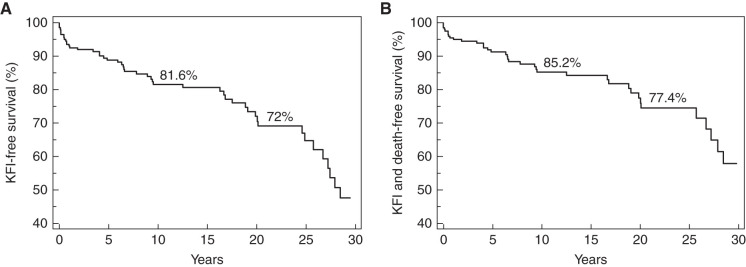

During a median (IQR) follow-up of 14.03 (4.94–20.67) years, kidney function became impaired in 39 (19%) patients in a median (IQR) of 6.6 (1.43–19.49) years after kidney biopsy, and 13 (33%) of these patients reached ESKD. KFI-free survival was 85% at 10 years and 77% at 20 years (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier kidney function impairment (KFI). (A)Free survival curve (A) and KFI and death-free survival curve (B) of the study population during the entire follow-up period.

Thirteen patients (6%) who did not develop KFI died after a median (IQR) of 11.43 (3.91–20.87) years; their causes of death were infections (three patients), cardiovascular accidents (five patients), and neoplasia (five patients). The KFI-free survival and deathfree survival were 82% and 72%, respectively, at 10 and at 20 years (Figure 1B).

Among the demographic variables, only the calendar year of biopsy (P=0.05) was weakly correlated with an activity index of more than six. On the basis of logistic regression analysis, older age (P<0.001) and longer delay between clinical onset of LN and kidney biopsy (P=0.001) were directly correlated with higher baseline chronicity index. In patients aged ≥30 years, the mean (±SD) chronicity index was 2.9 (±2.4), in comparison with 1.6 (±2.2) in those aged <30 years (P<0.001). When kidney biopsy was performed ≥3 or <3 months after the clinical LN onset, the respective mean chronicity index scores were 2.9 (±2.8) and 1.8 (±2; P=0.001).

Correlations between Clinical Features at Kidney Biopsy and Activity and Chronicity Indices

An activity index of more than six was significantly more frequent in class IV than in class III or V LN (Tables 3 and 4). Patients with an activity index of more than six had significantly higher serum creatinine and number of urine erythrocytes, and significantly lower levels of serum complement and hematocrit, compared with patients with an activity index of less than six. Similar correlations were observed for endocapillary hypercellularity, hyaline deposits, cellular crescents, and interstitial infiltration. In addition, hyaline deposits were also significantly associated with higher proteinuria and lower serum albumin levels. In comparison with the previous variable known as “neutrophil infiltration,” including karyorrhexis (11) within this variable still did not result in an association with serum creatinine, but it did have a significant correlation with proteinuria. In contrast, “fibrinoid necrosis” alone correlated with serum creatinine and with C3 (Supplemental Table 3).

Table 3.

Value of activity index in predicting clinical features at time of renal biopsy

| Clinical features and Lupus Nephritis Classes | Activity Index | Endocapillary Hypercellularity | Neutrophil Infiltration | Hyaline Deposits | Cellular Crescents | Fibrinoid Necrosis | Interstitial Infiltration | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤6 | >6 (43%) | 0 | >0 (66%) | 0 | >0 (75%) | 0 | >0 (52%) | ≤1 | >1 (20%) | ≤1 | >1 (35%) | 0 | >0 (50%) | |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dl | 1.1 (±1) | 1.4 (±1) | 1.2 (±1) | 1.3 (±1) | 1 (±1.1)a | 1.3 (±1)a | 1.1 (±1) | 1.4 (±1.1) | 1.2 (±0.9) | 1.7 (±1.3) | 1.2 (±1)a | 1.3 (±1)a | 1 (±1) | 1.5 (±1) |

| Proteinuria, g/24 h | 3.7 (±2.9)a | 4.4 (±3.8)a | 3.7 (±3)a | 4.2 (±3.5)a | 3.3 (±2.5)a | 4.2 (±3.5)a | 3.6 (±2.8) | 4.4 (±3.6) | 3.9 (±3.5)a | 4.2 (±2.4)a | 4.3 (±3.7)a | 3.5 (±2.3)a | 3.9 (±3.6)a | 4.1 (±2.9)a |

| Urinary erythrocytes, n/HPF | 17 (±25) | 32.6 (±32) | 13.1 (±25) | 29.8 (±31) | 10.6 (±25) | 28.4 (±30) | 17.2 (±28) | 30.6 (±30) | 22.2 (±29) | 32.3 (±31) | 20.2 (±28) | 31 (±32) | 20.4 (±29) | 28.3 (±30) |

| Serum albumin, mg/dl | 3 (±0.8)a | 2.8 (±0.6)a | 2.9 (±0.8)a | 2.9 (±0.7)a | 3.1 (±0.8)a | 2.9 (±0.7)a | 3 (±0.8) | 2.8 (±0.7) | 2.9 (±0.7)a | 2.8 (±0.6)a | 2.9 (±0.8)a | 3 (±0.7)a | 3 (±0.8)a | 2.8 (±0.7)a |

| C3, mg/dlb | 69.2 (±26) | 52.3 (±23) | 74.6 (±26) | 54.9 (±23) | 77.4 (±27) | 56.3 (±23) | 70.9 (±26) | 53.2 (±23) | 62.8 (±27)a | 56.5 (±22)a | 65.3 (±28) | 54.9 (±21) | 61.5 (±26) | 61.6 (±26) |

| C4, mg/dlb | 14.3 (±11) | 9.9 (±8.5) | 15.5 (±11) | 10.7 (±9) | 16.9 (±12) | 10.8 (±8.8) | 14.1 (±10) | 10.7 (±9.5) | 12.3 (±9.6)a | 12.6 (±12)a | 14 (±11) | 9.4 (±8) | 12.4 (±9.5)a | 12.2 (±11)a |

| Hematocrit, % | 35 (±7) | 32 (±5) | 35 (±7) | 33 (±5) | 37 (±6) | 32 (±6) | 35 (±7) | 32 (±5) | 34 (±6) | 32 (±5) | 34 (±6) | 32 (±5) | 34 (±6) | 33 (±6) |

| Class III, n (%) | 35 (30) | 10 (11) | 16 (23) | 29 (22) | 4 (8) | 41 (27) | 29 (30) | 16 (15) | 39 (24) | 6 (15) | 27 (20) | 18 (25) | 24 (24)a | 21 (21)a |

| Class IV, n (%) | 31 (27) | 77 (88) | 13 (19) | 95 (71) | 6 (12) | 102 (67) | 20 (20) | 88 (83) | 74 (45) | 34 (85) | 56 (42) | 52 (73) | 46 (45)a | 62 (61)a |

| Class V, n (%) | 47 (41) | 1 (1)c | 39 (56) | 9 (7) | 38 (76) | 10 (7) | 46 (47) | 2 (2) | 48 (29) | 0 | 47 (36) | 1 (1) | 30 (29)a | 18 (18)a |

(%) in the header row indicates the percentage of patients with the above-mentioned features. Values are expressed as mean (±SD), unless otherwise indicated.

Values indicate significant differences between the two compared groups (P<0.05), unless otherwise indicated by a footnote symbol. All of the histologic variables were evaluated as 0 if absent; 1+ if mild (in <25% of glomeruli and/or in tubulointerstitial area); 2+ if moderate (between 25% and <50% of glomeruli and/or in tubulointerstitial area); and 3+ if severe (in >50% of glomeruli and/or in tubulointerstitial area). HPF, high power field.

Nonsignificant differences between the two compared groups.

Normal value of C3 (normal values 90–180 mg/dl) and of C4 (normal values 10–40 mg/dl).

This patient had superimposed thrombotic microangiopathy.

Table 4.

Value of chronicity index and extraglomerular deposits in predicting clinical features at time of renal biopsy

| Clinical features and Lupus Nephritis Classes | Chronicity Index | Glomerulosclerosis | Fibrous Crescents | Tubular Atrophy | Interstitial Fibrosis | Extraglomerular Deposits | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤2 | >2 (35%) | ≤1 | >1 (14%) | ≤1 | >1 (13%) | ≤1 | >1 (7%) | ≤1 | >1 (10%) | No | Yes (46%) | |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dl | 1.1 (±1) | 1.5 (±1.2) | 1.2 (±0.9) | 1.8 (±1.5) | 1.2 (±1) | 1.7 (±1.3) | 1.2 (±0.9) | 2.5 (±1.8) | 1.2 (±0.9) | 2.1 (±1.6) | 1.1 (±0.8) | 1.5 (±1.3) |

| Proteinuria, g/24 h | 4.1 (±3.6)a | 3.8 (±2.8)a | 3.9 (±3.3)a | 4.5 (±3.2)a | 4.1 (±3.4)a | 3.7 (±2.6)a | 4.1 (±3.4)a | 3.7 (±2.2)a | 4.1 (±3.5)a | 3.7 (±1.9)a | 4.3 (±3.9)a | 3.7 (±2.5)a |

| Urinary erythrocytes, n/HPF | 24.9 (±32)a | 23.2 (±26)a | 24.7 (±31)a | 21.8 (±18)a | 24.6 (±30)a | 22.2 (±26)a | 24.5 (±30)a | 21.5 (±21)a | 25.1 (±31)a | 19.1 (±19)a | 19.8 (±29) | 29.4 (±31) |

| Serum albumin, mg/dl | 2.8 (±0.7)a | 3.1 (±0.8)a | 2.9 (±0.7)a | 2.9 (±0.8)a | 2.9 (±0.7)a | 3.1 (±0.8)a | 2.9 (±0.7)a | 3.1 (±0.8)a | 2.9 (±0.7)a | 3 (±0.8)a | 2.9 (±0.7)a | 2.9 (±0.8)a |

| C3, mg/dlb | 59 (±26) | 63.5 (±25) | 60.3 (±25)a | 68.8 (±29)a | 61.1 (±26)a | 64.5 (±26)a | 61.4 (±26)a | 64.2 (±31)a | 60.7 (±25)a | 66.6 (±32)a | 69.2 (±25) | 53.1 (±25) |

| C4, mg/dlb | 12.2 (±11)a | 12.5 (±8.1)a | 11.7 (±10) | 15.7 (±10) | 12.2 (±10)a | 12.8 (±9.4)a | 12.3 (±9.9)a | 12.8 (±12)a | 12 (±10)a | 14.2 (±10)a | 12.7 (±9.5)a | 11.9 (±11)a |

| Hematocrit, % | 34 (±6)a | 33 (±6)a | 34 (±6)a | 33 (±6)a | 34 (±6)a | 33 (±6)a | 34 (±6)a | 32 (±7)a | 34 (±6)a | 33 (±7)a | 35 (±7) | 32 (±5) |

| Class III, n (%) | 25 (19)a | 20 (29)a | 39 (22)a | 6 (21)a | 41 (23) | 4 (15) | 43 (23)a | 2 (14)a | 41 (22)a | 4 (20)a | 26 (24) | 19 (20) |

| Class IV, n (%) | 69 (52)a | 39 (56)a | 90 (51)a | 18 (64)a | 87 (49) | 21 (78) | 98 (52)a | 10 (71)a | 96 (53)a | 12 (60)a | 48 (44) | 60 (64) |

| Class V, n (%) | 37 (28)a | 11 (16)a | 44 (25)a | 4 (14)a | 46 (26) | 2 (7) | 46 (24)a | 2 (14)a | 44 (24)a | 4 (20)a | 33 (30) | 15 (16) |

(%) in the header row indicates the percentage of patients with the indicated features.

Values are expressed as mean (±SD), unless otherwise indicated. Values indicate significant differences between the two compared groups (P<0.05), unless otherwise indicated by a footnote symbol. All of the histologic variables were evaluated as 0 if absent; 1+ if mild (in <25% of glomeruli and/or in tubulointerstitial area); 2+ if moderate (between 25% and <50% of glomeruli and/or in tubulointerstitial area); and 3+ if severe (in >50% of glomeruli and/or in tubulointerstitial area). HPF, high power field.

Nonsignificant differences between the two compared groups.

Normal value of C3 (normal values 90–180 mg/dl) and of C4 (normal values 10–40 mg/dl).

As demonstrated for an activity index of more than six, there was also a significative direct correlation with serum creatinine for a chronicity index score of more than two, and all of its components. In addition, serum C3 and C4 levels were directly correlated with chronicity index.

The presence of extraglomerular deposits correlated with higher serum creatinine, a high number of urinary erythrocytes, and low C3 and hematocrit.

Histologic Predictors of KFI in the Long Term

Among the ISN/RPS histologic classes, only class IV LN showed a weak correlation with KFI in univariate analysis (P=0.05; Tables 2 and 5).

Table 5.

Histologic predictors of KFI: univariate and multivariate analysis

| Histogic Features | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis 1 | Multivariate Analysis 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | P Value | Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | P Value | Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | P Value | |

| Histologic classes III+IV versus II+V | 1.68 (0.77 to 3.68) | 0.20 | ||||

| Histologic class IV versus all of the other classes | 1.95 (1.01 to 3.78) | 0.05a | ||||

| Activity index ≤6 versus >6 | 1.08 (0.57 to 2.04) | 0.81 | ||||

| Endocapillary hypercellularityb | 1.14 (0.58 to 2.22) | 0.71 | ||||

| Neutrophil infiltrationb | 1.13 (0.55 to 2.32) | 0.74 | ||||

| Hyaline deposits/wire loopsb | 0.62 (0.32 to 1.19) | 0.15 | ||||

| Cellular/fibrocellular crescentc | 1.73 (0.81 to 3.67) | 0.16 | ||||

| Fibrinoid necrosis/ karyorrhexisc | 0.62 (0.28 to 1.35) | 0.23 | ||||

| Interstitial inflammationb | 2.21 (1.15 to 4.27) | 0.02a | ||||

| Interstitial inflammation in normal T-I areasb | 0.74 (0.33 to 1.69) | 0.68 | ||||

| Interstitial inflammation in presence of chronic T-I lesionsb | 3.15 (1.65 to 6.02) | <0.001a | ||||

| Neutrophil infiltration/ karyorrhexisb | 1.15 (0.56 to 2.37) | 0.39 | ||||

| Fibrinoid necrosisc | 0.48 (0.17 to 1.35) | 0.16 | ||||

| Chronicity index ≤2 versus >2 | 3.98 (2.08 to 7.62) | <0.001a | ||||

| Glomerulosclerosisc | 4.88 (2.49 to 9.54) | <0.001a | 3.05 (1.17 to 7.92) | 0.02 | 3.94 (1.84 to 8.43) | <0.001 |

| Fibrous crescentsc | 7.00 (3.43 to 14.26) | <0.001a | 6.84 (3.22 to 14.52) | <0.001 | 5.77 (2.57 to 12.94) | <0.001 |

| Tubular atrophyc | 9.30 (4.30 to 20.1) | <0.001a | 3.17 (1.04 to 9.64) | 0.04 | ||

| Interstitial fibrosisc | 7.27 (3.68 to 14.37) | <0.001a | 2.36 (1.05 to 5.32) | 0.038 | ||

| Extraglomerular deposits d | 2.00 (1.04 to 3.86) | 0.04a | ||||

| Tubular depositsd | 1.14 (0.60 to 2.16) | 0.69 | ||||

| Interstitial capillary wall depositsd | 1.69 (0.66 to 4.35) | 0.27 | ||||

| Vascular depositsd | 2.44 (1.27 to 4.68) | 0.007a | ||||

Likelihood ratio test used for multivariate analysis 1 (46.25 on 3 df; P<0.001) and for multivariate analysis 2 (46.17 on 3 df; P<0.001). KFI, kidney function impairment; T-I, tubulointerstitial.

P≤0.05.

These variables were categorized as 0 versus 1+2+3; where 0 scored if absent; 1+ if mild (in <25% of glomeruli and/or in tubulointerstitial cortex); 2+ if moderate (between 25% and <50% of glomeruli and/or in tubulointerstitial cortex); and 3+ if severe (in >50% of glomeruli and/or in tubulointerstitial cortex).

These variables were categorized as 0+1 versus 2+3.

These variables were categorized as present or absent.

The presence of interstitial inflammation (P=0.02) was the only component of the activity index that was associated with development of KFI in univariate analysis. However, when we evaluated separately interstitial infiltration in patients with or without interstitial chronic lesions, the correlation with KFI was only maintained when tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis were present (P<0.001), whereas the correlation was lost in the presence of normal cortex (P=0.68).

A chronicity index of more than two (P<0.001) and moderate/severe degree of glomerulosclerosis (P<0.001), fibrous crescents (P<0.001), tubular atrophy (P<0.001), interstitial fibrosis (P<0.001), presence of extraglomerular deposits (P=0.04), and vascular immune deposits (P=0.007) were significantly associated with KFI in univariate analysis.

In multivariate analysis, two models with the same power were associated with the development of KFI (likelihood ratio P<0.001 in both). Both models included moderate/severe glomerulosclerosis (model 1: odds ratio [OR], 3.05; 95% CI, 1.17 to 7.92; P=0.02; model 2: OR, 3.94; 95% CI, 1.84 to 8.43; P<0.001) and fibrous crescents (model 1: OR, 6.84; 95% CI, 3.22 to 14.52; P<0.001; model 2: OR, 5.77; 95% CI, 2.57 to 12.94; P<0.001). In the first model, glomerulosclerosis and fibrous crescents included moderate/severe tubular atrophy (OR, 3.17; 95% CI, 1.04 to 9.64; P=0.04), whereas glomerulosclerosis and fibrous crescents were associated with interstitial fibrosis (OR, 2.36; 95% CI, 1.05 to 5.32; P=0.04) in the second model. The quasi-equivalence of the two models can be explained by the strong correlation between tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis (r=0.66, P<0.001).

The histologic predictors of KFI in the subgroup of patients with class IV LN in univariate and multivariate analysis are reported in Supplemental Table 4. Similarly to what was observed in the whole group, in multivariate analysis, glomerulosclerosis (OR, 4.09; 95% CI, 1.55 to 10.78; P=0.005), fibrous crescents (OR, 4.27; 95% CI, 1.52 to 12.03; P=0.006), and interstitial fibrosis (OR, 3.23; 95% CI, 1.15 to 9.05; P=0.03) were independent predictors of KFI.

Clinical and Histologic Predictors of KFI

Among the clinical variables, serum creatinine (for any milligram per deciliter increase in serum creatinine, OR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.45 to 2.22; P<0.001); arterial hypertension (OR, 6.15; 95% CI, 2.60 to 14.58; P<0.001); and, among the possible confounders, months from clinical LN onset to kidney biopsy (for each month delay in performing renal biopsy, OR, 1.01; 95% CI, 1.00 to 1.01; P=0.02) were independent predictors of KFI in multivariate analysis (Table 6).

Table 6.

Clinical and histologic predictors of KFI: uUnivariate and multivariate analysis

| Predictors | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | P Value | Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | P Value | |

| Clinical predictors of KFI | ||||

| Serum creatinine, mg/dl | 1.91 (1.56 to 2.33) | <0.001 | 1.79 (1.45 to 2.22) | <0.001 |

| Creatinine clearance, ml/min | 0.98 (0.97 to 0.99) | <0.001 | ||

| Arterial hypertension | 8.62 (3.67 to 20.26) | <0.001 | 6.15 (2.60 to 14.58) | <0.001 |

| Hematocrit, % | 0.93 (0.88 to 0.98) | 0.005 | ||

| Serositis | 2.42 (1.23 to 4.77) | 0.01 | ||

| Months from LN onset to kidney biopsy | 1.01 (1.00 to 1.01) | 0.02 | ||

| Clinical and histologic predictors of KFI | ||||

| Serum creatinine, mg/dl | 1.68 (1.31 to 2.15) | <0.001 | ||

| Arterial hypertension | 4.64 (1.90 to 11.32) | <0.001 | ||

| Glomerulosclerosisa | 2.12 (1.00 to 4.50) | 0.05 | ||

| Fibrous crescentsa | 5.18 (2.43 to 11.04) | <0.001 | ||

| Months from LN onset to kidney biopsy | 1.01 (1.00 to 1.01) | 0.03 | ||

KFI, kidney function impairment; LN, lupus nephritis.

The histologic variables were categorized as 0 + 1 versus 2 + 3; where 0 is scored if absent; 1+ if mild (in <25% of glomeruli and/or in tubulointerstitial cortex); 2+ if moderate (between 25% and <50% of glomeruli and/or in tubulointerstitial cortex); and 3+ if severe (in >50% of glomeruli and/or in tubulointerstitial cortex).

Adding the histologic characteristic to the clinical data, in multivariate analysis, serum creatinine (for any milligram per deciliter increase in serum creatinine, OR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.31 to 2.15; P<0.001), arterial hypertension (OR, 4.64; 95% CI, 1.90 to 11.32; P<0.001), glomerulosclerosis (OR, 2.12; 95% CI, 1.00 to 4.50; P=0.05), fibrous crescents (OR, 5.18; 95% CI, 2.43 to 11.04; P<0.001), and months from LN onset to kidney biopsy (OR, 1.01; 95% CI, 1.00 to 1.01; P=0.03) were found to be independent predictors of KFI.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated whether the demographic characteristics of the population had an effect on the severity of activity and chronicity index scores at baseline kidney biopsy. No significant association was found between demographic parameters and activity index. Instead, we found that older age at biopsy and a longer time between onset of clinical renal signs and kidney biopsy were significantly correlated with the chronicity index. Previous studies reported that delay in starting treatment after clinical onset of LN significantly increases the probability of ESKD (16,17). We confirmed the deleterious effect of delayed biopsy on kidney function, and found a significant association between delay in performing a biopsy and increase in baseline chronicity index. This reinforces the importance of performing a biopsy as soon as any sign of kidney involvement appears. This point was also stressed by recent guidelines for LN (2).

One purpose of this study was to evaluate if the clinical renal manifestations were able to predict the type and severity of baseline histologic lesions. In univariate analysis, there was a strong correlation between laboratory signs of LN and the activity index and most of its components (Tables 3 and 4). Hyaline deposits had the best correlation with clinical activity. This is not surprising if one considers that LN is probably initiated by glomerular deposition of immune complexes containing nucleic acids (18).

However, both activity and chronicity indices were significantly and directly correlated with serum creatinine. This suggests that, in the presence of high serum creatinine, without a kidney biopsy, it is difficult to establish if the renal impairment is due to active or chronic lesions. In addition, proteinuria is not of help because this parameter did not correlate with activity nor with chronicity indices.

Our results, in line with recent guidelines (2), confirm that the kidney biopsy remains crucial for its diagnostic and prognostic value. The correlation between serum creatinine and chronicity index was also confirmed by Leatherwood et al. (19) and Broder et al. (20).

The correlation between serum creatinine and extraglomerular deposits was present in univariate analysis, but significance was lost in multivariate analysis. However, patients with extraglomerular deposits seemed to have a more active LN (higher urinary erythrocyte number, lower C3 and hematocrit), in agreement with Wang et al. (21), and in contrast to Hill et al. (22).

An important aim of this study was to define the value of baseline histologic features in predicting the development of KFI in the long term. Several studies evaluated, separately or together, the effect of interstitial inflammation (20,23–26), chronic tubulointerstitial lesions (19,20,23,24), and extraglomerular deposits (21,22,25,27) in predicting kidney outcome, but with conflicting results. In this study, class IV LN showed a weak association with KFI in univariate analysis, but this association was lost in multivariate analysis (Supplemental Table 4). Recent studies also reported the poor prognostic value of the ISN/RPS classification (7–10). Interstitial inflammation was the only element of the activity index that was associated with KFI in univariate analysis, but this association was not found during multivariate analysis. Our results are consistent with two previous studies (20,26). In three other studies, interstitial inflammation was an independent predictor of poor kidney outcome (23,24,28). Different criteria in the evaluation of interstitial infiltration may explain the discrepant results. As observed in kidney transplantation, interstitial inflammation in normal tubulointerstitial areas may be considered as an expression of active rejection, which can potentially respond to therapy. (26,29). Conversely, interstitial inflammation in areas with interstitial fibrosis/tubular atrophy is hardly reversible and is associated with poor kidney survival (30). In our study, interstitial infiltration lost the correlation with KFI if the tubulointerstitial area was normal, whereas the correlation with KFI was maintained with tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis. Thus, to better assess the prognostic value of interstitial inflammation, it is important to define the setting and the type of inflammatory components (11,23).

The correlation between interstitial inflammation and immune complexes in tubulointerstitium is controversial (25,31–33). No significant correlation was found between interstitial inflammation and extraglomerular immune deposits (data not shown), disproving the pathogenetic interdependence between the two lesions. The presence of extraglomerular immune complexes was associated with KFI in univariate analysis, but not in multivariate analysis (21). Thus, as already suggested by others (22,27), tubulointerstitial immune deposits play only a minor role in the progression of LN.

In this large cohort of patients with LN followed for a median of 14 years, all of the glomerular and tubulointerstitial components of the chronicity index were significantly associated with poor kidney survival in multivariate analysis.

The effect of tubulointerstitial chronic lesions on CKD was already outlined by many reports (19,20,23–25,28,34). However, only few studies evaluated simultaneously the effect of chronic glomerular and tubulointerstitial damage with conflicting results. Hsieh et al. (23) found that tubulointerstitial inflammation and fibrosis, but not glomerular injury, identified patients at risk of ESKD. In a multicenter Chinese study, interstitial inflammation, tubular atrophy, and interstitial fibrosis were the only independent risk factors of kidney outcome (24). In another study, the proportion of globally sclerotic glomeruli predicted kidney survival in univariate analysis but not in multivariate analysis (28).

Instead, in 105 patients followed for 9.9 years, fibrinoid necrosis, fibrous crescents, and interstitial fibrosis/tubular atrophy, together with kidney function and non-White race, predicted ESKD (35). The recent revision of the ISN/RPS classification was used to evaluate the outcome of 101 Chinese patients with LN followed for about 10 years. In multivariate analysis, fibrous crescents, tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis, and the National Institutes of Health chronicity index were independent risk factors for a composite renal outcome that includes eGFR reduction ≥30%, ESKD, and death (36).

These data and our results, obtained in a larger cohort and with a longer follow-up, can support the thesis that glomerulosclerosis and interstitial fibrosis are linked pathogenetically. Insufficient blood supply from damaged glomeruli causes chronic hypoxia, which releases IL-1 and IL-6, angiotensin II, and TGF-β, resulting in accumulation of extracellular matrix and fibrosis. The excessive deposition of extracellular matrix can replace functional parenchyma, release inflammatory mediators and reactive oxygen species, and induce epithelial-mesenchymal transition, eventually leading to interstitial fibrosis and chronic kidney failure (37–40). However, tubulointerstitial damage may lead to KFI through different mechanisms. An alternative mechanism for the development could rest on the in loco production of autoantibodies from lymphoid-like structures present in the interstitium (23). The divergent isotypes of antibodies deposited in the glomeruli and in the interstitium may validate this hypothesis (31). Regardless of the relationship between glomerular and tubulointerstitial damage, our data show that chronic glomerular and tubulointerstitial damage are both the determinants of kidney prognosis. However, we found that the best model for predicting KFI resulted from the combination of histologic and clinical characteristics at presentation. Moreover, adding activity and chronicity index to the ISN/RPS LN classification improves the prognostic value of kidney biopsy.

Our study has limitations due to its retrospective nature and extended follow-up period, over which the treatment regimens used in LN have evolved. Most participants were White, and these results cannot be extended to other races and ethnicities. Data were from a real-world LN cohort, and treatment and duration of follow-up were not standardized. Except for the re-evaluation of “fibrinoid/karyorrhexis necrosis” and “neutrophil infiltration,” we have not performed an evaluation of other changes of activity and chronicity indices proposed by the recent revision of the ISN/RPS classification (11). Larger prospective studies are needed to confirm these results.

Disclosures

G. Moroni reports having consultancy agreements with GlaxoSmithKline. L. Sacchi reports serving on the editorial boards of Artificial Intelligence in Medicine, BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, Journal of Biomedical Informatics, and PLOS One (as academic editor); and serving as chair for Società Scientifica Italiana di Informatica BioMedica (Italian Society of Biomedical Informatics). All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

None.

Footnotes

See related editorial, “Predicting Kidney Survival in Lupus Nephritis by Adding Clinical Data to Pathologic Features,” on pages 5–7.

Author Contributions

G. Banfi, M. Calatroni, C. Ponticelli, G. Porata, and F. Reggiani were responsible for visualization; G. Banfi, G. Moroni, and C. Ponticelli provided supervision; G. Banfi, G. Moroni, C. Ponticelli, G. Porata, S. Quaglini, and L. Sacchi were responsible for validation; G. Banfi, G. Moroni, G. Porata, and C. Ponticelli reviewed and edited the manuscript; V. Binda, G. Frontini, G. Moroni, G. Porata, S. Quaglini, F. Raffiotta, and L. Sacchi were responsible for data curation and formal analysis; V. Binda, G. Frontini, G. Moroni, G. Porata, and F. Raffiotta were responsible for investigation; G. Moroni and C. Ponticelli conceptualized the study; G. Moroni and G. Porata were responsible for methodology and resources; and G. Moroni, C. Ponticelli, and G. Porata wrote the original draft.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://kidney360.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.34067/KID.0005512021/-/DCSupplemental.

Change in immunosuppressive therapy in the different periods of the study. Download Supplemental Table 1, PDF file, 196 KB (195.4KB, pdf)

Clinical findings at one year in the 25 patients lost to follow-up and in the 178 who were followed until the end of the study. Download Supplemental Table 2, PDF file, 196 KB (195.4KB, pdf)

Comparison of correlations with clinical features at renal biopsy of old definitions of “neutrophil infiltration” and “fibrinoid necrosis karyorrhexis”, and the new definitions suggested by the recent revision of histological classification of LN “neutrophil infiltration/karyorrhexis” and “fibrinoid necrosis.” Download Supplemental Table 3, PDF file, 196 KB (195.4KB, pdf)

Histological predictors of KFI among histological features at renal biopsy in 108 patients with class IV lupus nephritis—univariate and multivariate analysis. Download Supplemental Table 4, PDF file, 196 KB (195.4KB, pdf)

References

- 1.Hanly JG, O’Keeffe AG, Su L, Urowitz MB, Romero-Diaz J, Gordon C, Bae SC, Bernatsky S, Clarke AE, Wallace DJ, Merrill JT, Isenberg DA, Rahman A, Ginzler EM, Fortin P, Gladman DD, Sanchez-Guerrero J, Petri M, Bruce IN, Dooley MA, Ramsey-Goldman R, Aranow C, Alarcón GS, Fessler BJ, Steinsson K, Nived O, Sturfelt GK, Manzi S, Khamashta MA, van Vollenhoven RF, Zoma AA, Ramos-Casals M, Ruiz-Irastorza G, Lim SS, Stoll T, Inanc M, Kalunian KC, Kamen DL, Maddison P, Peschken CA, Jacobsen S, Askanase A, Theriault C, Thompson K, Farewell V: The frequency and outcome of lupus nephritis: Results from an international inception cohort study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 55: 252–262, 2016. 10.1093/rheumatology/kev311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fanouriakis A, Kostopoulou M, Cheema K, Anders HJ, Aringer M, Bajema I, Boletis J, Frangou E, Houssiau FA, Hollis J, Karras A, Marchiori F, Marks SD, Moroni G, Mosca M, Parodis I, Praga M, Schneider M, Smolen JS, Tesar V, Trachana M, van Vollenhoven RF, Voskuyl AE, Teng YKO, van Leew B, Bertsias G, Jayne D, Boumpas DT: 2019 Update of the Joint European League Against Rheumatism and European Renal Association-European Dialysis and Transplant Association (EULAR/ERA-EDTA) recommendations for the management of lupus nephritis. Ann Rheum Dis 79: 713–723, 2020. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-216924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weening JJ, D’Agati VD, Schwartz MM, Seshan SV, Alpers CE, Appel GB, Balow JE, Bruijn JA, Cook T, Ferrario F, Fogo AB, Ginzler EM, Hebert L, Hill G, Hill P, Jennette JC, Kong NC, Lesavre P, Lockshin M, Looi LM, Makino H, Moura LA, Nagata M; International Society of Nephrology Working Group on the Classification of Lupus Nephritis; Renal Pathology Society Working Group on the Classification of Lupus Nephritis : The classification of glomerulonephritis in systemic lupus erythematosus revisited. Kidney Int 65: 521–530, 2004. 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00443.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Austin HA 3rd, Muenz LR, Joyce KM, Antonovych TA, Kullick ME, Klippel JH, Decker JL, Balow JE: Prognostic factors in lupus nephritis. Contribution of renal histologic data. Am J Med 75: 382–391, 1983. 10.1016/0002-9343(83)90338-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Austin HA 3rd, Muenz LR, Joyce KM, Antonovych TT, Balow JE: Diffuse proliferative lupus nephritis: Identification of specific pathologic features affecting renal outcome. Kidney Int 25: 689–695, 1984. 10.1038/ki.1984.75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Austin HA 3rd, Boumpas DT, Vaughan EM, Balow JE: Predicting renal outcomes in severe lupus nephritis: Contributions of clinical and histologic data. Kidney Int 45: 544–550, 1994. 10.1038/ki.1994.70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moroni G, Vercelloni PG, Quaglini S, Gatto M, Gianfreda D, Sacchi L, Raffiotta F, Zen M, Costantini G, Urban ML, Pieruzzi F, Messa P, Vaglio A, Sinico RA, Doria A: Changing patterns in clinical-histological presentation and renal outcome over the last five decades in a cohort of 499 patients with lupus nephritis. Ann Rheum Dis 77: 1318–1325, 2018. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moroni G, Gatto M, Tamborini F, Quaglini S, Radice F, Saccon F, Frontini G, Alberici F, Sacchi L, Binda V, Trezzi B, Vaglio A, Messa P, Sinico RA, Doria A: Lack of EULAR/ERA-EDTA response at 1 year predicts poor long-term renal outcome in patients with lupus nephritis. Ann Rheum Dis 79: 1077–1083, 2020. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-216965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kojo S, Sada KE, Kobayashi M, Maruyama M, Maeshima Y, Sugiyama H, Makino H: Clinical usefulness of a prognostic score in histological analysis of renal biopsy in patients with lupus nephritis. J Rheumatol 36: 2218–2223, 2009. 10.3899/jrheum.080793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwartz MM, Korbet SM, Lewis EJ; Collaborative Study Group : The prognosis and pathogenesis of severe lupus glomerulonephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 1298–1306, 2008. 10.1093/ndt/gfm775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bajema IM, Wilhelmus S, Alpers CE, Bruijn JA, Colvin RB, Cook HT, D’Agati VD, Ferrario F, Haas M, Jennette JC, Joh K, Nast CC, Noël LH, Rijnink EC, Roberts ISD, Seshan SV, Sethi S, Fogo AB: Revision of the International Society of Nephrology/Renal Pathology Society classification for lupus nephritis: Clarification of definitions, and modified National Institutes of Health activity and chronicity indices. Kidney Int 93: 789–796, 2018. 10.1016/j.kint.2017.11.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hochberg MC: Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 40: 1725, 1997. 10.1002/art.1780400928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fogazzi GB, Bajetta M, Banfi G, Mihatsch M: Comparison of immunofluorescent findings in kidney after snap-freezing and formalin fixation. Pathol Res Pract 185: 225–230, 1989. 10.1016/S0344-0338(89)80256-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cockcroft DW, Gault MH: Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron 16: 31–41, 1976. 10.1159/000180580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.R Development Core Team : R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2008. Available at: http://www.R-project.org. Accessed December 4, 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faurschou M, Starklint H, Halberg P, Jacobsen S: Prognostic factors in lupus nephritis: Diagnostic and therapeutic delay increases the risk of terminal renal failure. J Rheumatol 33: 1563–1569, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Esdaile JM, Joseph L, MacKenzie T, Kashgarian M, Hayslett JP: The benefit of early treatment with immunosuppressive agents in lupus nephritis. J Rheumatol 21: 2046–2051, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davidson A: What is damaging the kidney in lupus nephritis? Nat Rev Rheumatol 12: 143–153, 2016. 10.1038/nrrheum.2015.159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leatherwood C, Speyer CB, Feldman CH, D’Silva K, Gómez-Puerta JA, Hoover PJ, Waikar SS, McMahon GM, Rennke HG, Costenbader KH: Clinical characteristics and renal prognosis associated with interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy (IFTA) and vascular injury in lupus nephritis biopsies. Semin Arthritis Rheum 49: 396–404, 2019. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2019.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Broder A, Mowrey WB, Khan HN, Jovanovic B, Londono-Jimenez A, Izmirly P, Putterman C: Tubulointerstitial damage predicts end stage renal disease in lupus nephritis with preserved to moderately impaired renal function: A retrospective cohort study. Semin Arthritis Rheum 47: 545–551, 2018. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2017.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang H, Xu J, Zhang X, Ren YL, Cheng M, Guo ZL, Zhang JC, Cheng H, Xing GL, Wang SX, Yu F, Zhao MH: Tubular basement membrane immune complex deposition is associated with activity and progression of lupus nephritis: A large multicenter Chinese study. Lupus 27: 545–555, 2018. 10.1177/0961203317732407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hill GS, Delahousse M, Nochy D, Mandet C, Bariéty J: Proteinuria and tubulointerstitial lesions in lupus nephritis. Kidney Int 60: 1893–1903, 2001. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00017.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsieh C, Chang A, Brandt D, Guttikonda R, Utset TO, Clark MR: Predicting outcomes of lupus nephritis with tubulointerstitial inflammation and scarring. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 63: 865–874, 2011. 10.1002/acr.20441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu F, Wu LH, Tan Y, Li LH, Wang CL, Wang WK, Qu Z, Chen MH, Gao JJ, Li ZY, Zheng X, Ao J, Zhu SN, Wang SX, Zhao MH, Zou WZ, Liu G: Tubulointerstitial lesions of patients with lupus nephritis classified by the 2003 International Society of Nephrology and Renal Pathology Society system. Kidney Int 77: 820–829, 2010. 10.1038/ki.2010.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park MH, D’Agati V, Appel GB, Pirani CL: Tubulointerstitial disease in lupus nephritis: Relationship to immune deposits, interstitial inflammation, glomerular changes, renal function, and prognosis. Nephron 44: 309–319, 1986. 10.1159/000184012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alsuwaida AO: Interstitial inflammation and long-term renal outcomes in lupus nephritis. Lupus 22: 1446–1454, 2013. 10.1177/0961203313507986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koopman JJE, Rennke HG, Leatherwood C, Speyer CB, D’Silva K, McMahon GM, Waikar SS, Costenbader KH: Renal deposits of complement factors as predictors of end-stage renal disease and death in patients with lupus nephritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 59: 3751–3758, 2020. 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson PC, Kashgarian M, Moeckel G: Interstitial inflammation and interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy predict renal survival in lupus nephritis. Clin Kidney J 11: 207–218, 2018. 10.1093/ckj/sfx093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pagni F, Galimberti S, Galbiati E, Rebora P, Pietropaolo V, Pieruzzi F, Smith AJ, Ferrario F: Tubulointerstitial lesions in lupus nephritis: International multicentre study in a large cohort of patients with repeat biopsy. Nephrology (Carlton) 21: 35–45, 2016. 10.1111/nep.12555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mannon RB, Matas AJ, Grande J, Leduc R, Connett J, Kasiske B, Cecka JM, Gaston RS, Cosio F, Gourishankar S, Halloran PF, Hunsicker L, Rush D; DeKAF Investigators : Inflammation in areas of tubular atrophy in kidney allograft biopsies: A potent predictor of allograft failure. Am J Transplant 10: 2066–2073, 2010. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03240.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Satoskar AA, Brodsky SV, Nadasdy G, Bott C, Rovin B, Hebert L, Nadasdy T: Discrepancies in glomerular and tubulointerstitial/vascular immune complex IgG subclasses in lupus nephritis. Lupus 20: 1396–1403, 2011. 10.1177/0961203311416533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clark MR, Trotter K, Chang A: The pathogenesis and therapeutic implications of tubulointerstitial inflammation in human lupus nephritis. Semin Nephrol 35: 455–464, 2015. 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2015.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang A, Henderson SG, Brandt D, Liu N, Guttikonda R, Hsieh C, Kaverina N, Utset TO, Meehan SM, Quigg RJ, Meffre E, Clark MR: In situ B cell-mediated immune responses and tubulointerstitial inflammation in human lupus nephritis. J Immunol 186: 1849–1860, 2011. 10.4049/jimmunol.1001983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hachiya A, Karasawa M, Imaizumi T, Kato N, Katsuno T, Ishimoto T, Kosugi T, Tsuboi N, Maruyama S: The ISN/RPS 2016 classification predicts renal prognosis in patients with first-onset class III/IV lupus nephritis. Sci Rep 11: 1525, 2021. 10.1038/s41598-020-78972-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rijnink EC, Teng YKO, Wilhelmus S, Almekinders M, Wolterbeek R, Cransberg K, Bruijn JA, Bajema IM: Clinical and histopathologic characteristics associated with renal outcomes in lupus nephritis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 734–743, 2017. 10.2215/CJN.10601016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tao J, Wang H, Yu XJ, Tan Y, Yu F, Wang SX, Haas M, Glassock RJ, Zhao MH: A validation of the 2018 Revision of International Society of Nephrology/Renal Pathology Society classification for lupus nephritis: A cohort study from China. Am J Nephrol 51: 483–492, 2020. 10.1159/000507213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haase VH: Inflammation and hypoxia in the kidney: Friends or foes? Kidney Int 88: 213–215, 2015. 10.1038/ki.2015.89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamaguchi J, Tanaka T, Eto N, Nangaku M: Inflammation and hypoxia linked to renal injury by CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein δ. Kidney Int 88: 262–275, 2015. 10.1038/ki.2015.21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu BC, Tang TT, Lv LL, Lan HY: Renal tubule injury: A driving force toward chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 93: 568–579, 2018. 10.1016/j.kint.2017.09.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ponticelli C, Campise MR: The inflammatory state is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease and graft fibrosis in kidney transplantation. Kidney Int 100: 536–545, 2021. 10.1016/j.kint.2021.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Change in immunosuppressive therapy in the different periods of the study. Download Supplemental Table 1, PDF file, 196 KB (195.4KB, pdf)

Clinical findings at one year in the 25 patients lost to follow-up and in the 178 who were followed until the end of the study. Download Supplemental Table 2, PDF file, 196 KB (195.4KB, pdf)

Comparison of correlations with clinical features at renal biopsy of old definitions of “neutrophil infiltration” and “fibrinoid necrosis karyorrhexis”, and the new definitions suggested by the recent revision of histological classification of LN “neutrophil infiltration/karyorrhexis” and “fibrinoid necrosis.” Download Supplemental Table 3, PDF file, 196 KB (195.4KB, pdf)

Histological predictors of KFI among histological features at renal biopsy in 108 patients with class IV lupus nephritis—univariate and multivariate analysis. Download Supplemental Table 4, PDF file, 196 KB (195.4KB, pdf)