Abstract

Introduction

Posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF) has been widely used to treat various degenerative spinal diseases. However, surgical site infection (SSI) post-PLIF is often difficult to cure. This study aimed to clarify the difference in clinical course due to the causative organism and develop a treatment strategy for SSI post-PLIF.

Methods

Between January 2011 and March 2019, 581 PLIF surgeries were performed at our hospital. Deep SSI occurred in 14 patients who were followed up for more than 2 years. Causative bacterial species were diagnosed by preoperative puncture and/or intraoperative drainage or by tissue culture in 13 patients and by intradiscal puncture in one patient who underwent conservative treatment. Of the 13 patients who underwent surgeries for infection, 10 had Propionibacterium acnes (Group A; n = 4) or coagulase-negative Staphylococcus (CNS) (Group B; n = 6) as the causative bacterial species. Groups A and B were retrospectively compared in terms of age, sex, number of segments, presence of diabetes mellitus, operation time, blood loss, C-reactive protein on hematological examination, the elapsed time to diagnosis (ETD), the presence of clinical findings such as heat, redness, swelling, and discharge from the wound and healing time.

Results

All infections were eradicated with surgery except in one patient whose causative bacteria was CNS; cages were finally removed in 11 patients. There was a significant difference (P = 0.0105) in the ETD and clinical findings (P = 0.0476) between Groups A and B. Posterior one-stage simultaneous revision (POSSR) was performed in nine patients, of whom eight were cured and one required additional surgery.

Conclusions

The ETD and clinical findings were significantly different in SSI cases caused by different bacteria, which will be useful in predicting the causative bacteria in future cases. For the treatment of deep SSI post-PLIF, POSSR was effective.

Keywords: Posterior lumbar interbody fusion, Surgical site infection, Propionibacterium acnes, Coagulase-negative staphylococcus, Elapsed time to diagnosis

1. Introduction

Posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF) has been widely performed for degenerative spinal diseases with increasing application among the elderly population. As PLIF allows for the reconstruction of the anterior column through a posterior approach, achieving sagittal reconstruction and bone union is feasible.1,2 Thus, PLIF is used as a surgical treatment for spondylolisthesis, spinal canal stenosis, lumbar disc hernia, and other lumbar diseases. However, deep surgical site infection (SSI) post-PLIF is often difficult to eradicate. The most prominent location of an SSI post-PLIF is in the intradiscal space.1, 2, 3 Propionibacterium acnes and coagulase-negative Staphylococcus (CNS) are organisms that are frequently identified in patients with pediatric scoliosis treated with instrumented fusion.4, 5, 6, 7 Few studies have described deep SSIs caused by P. acnes in adult patients,8, 9, 10 and none distinguished the differences in clinical courses and symptoms in patients with infections caused by different species. In this retrospective study, we aimed to clarify these differences and develop a treatment strategy for deep SSI post-PLIF.

2. Materials and methods

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki. The institutional review board provided approval for this retrospective study, and the need for written informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study. This study was approved by our hospital ethics committee (approval code 1249).

Between January 2011 and March 2019, 581 PLIF surgeries were performed at our hospital. Deep SSI occurred in 14 patients who were followed up for >2 years. These infections are classified according to the criteria of the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.11 We defined superficial SSIs as those that extended to the skin and subcutaneous tissues but did not reach the muscle layer and that could be eradicated through debridement and secondary suturing under local anesthesia or through conservative treatment involving washing and dressing. Inclusion criteria were clinical and imaging diagnosis of lumbar degenerative disease (i.e., lumbar spondylolisthesis, lumbar spinal stenosis, lumbar disc herniation, and adjacent lesions), age >18 years, surgical treatment with PLIF, and presence of SSIs that were not obvious superficial SSIs and complete medical records as well as follow-up of at least 2 years. Exclusion criteria were preoperative diagnosis with discitis and patients with SSIs that were obvious superficial SSIs as mentioned earlier. All PLIFs were performed by surgeons at our hospital. Titanium pedicle screw system implants were used in all cases. The patients received intravenous antibiotic injection three times (before the skin incision and after 3 h and 6 h) on the day of PLIF and twice on the first day after PLIF. According to the patient's weight and renal function, the number and amount of intravenous antibiotic injections were adjusted. Cefazolin was used unless there was a history of allergies to cephem antibiotics.

In this study, we identified 14 patients (Table 1). PLIFs with polyetheretherketone cages were performed in 13 patients and with auto-iliac bone graft in one (No. 12) due to uncontrolled diabetes mellitus as per our experience. In the 13 patients who underwent operations for infection, the diagnosis of SSI was determined according to a preoperative puncture and/or the intraoperative drainage or tissue culture. One CNS patient (No. 9) who was treated with conservative treatment (intravenous antibiotics without surgery), infection was diagnosed by the culture from an intravertebral disc puncture under fluoroscopy performed before the administration of intravenous antibiotics. After C-reactive protein (CRP) was confirmed to be negative, intravenous antibiotics were administered for up to 1 week, followed by oral antibiotics for 4–6 weeks. Several patients were forced to discontinue the use of antibiotics owing to the side effects of intravenous antibiotics before CRP became completely negative; however, CRP did become negative eventually. If the causative organism was not identified, we used a broad-spectrum antibiotic and changed the antibiotic if it was deemed ineffective. All patients were followed up for at least 2 years, and bone union and recurrence of SSI by laboratory hematological data and X-ray images were evaluated.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of SSI in post-PLIF patients.

| No. | Age | Sex | DM | Clinical findings | No. of PLIF segments | Operation time | Blood loss | Microorganism | ETD | Therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 71 | M | + | + | 2 | 156 | 950 | MRCNS | 16 | I & D |

| 2 | 72 | M | – | + | 1 | 117 | 150 | MRCNS | 20 | I & D ASCR |

| 3 | 74 | M | – | – | 1 | 180 | 200 | MRCNS | 15 | POSSR |

| 4 | 64 | M | + | + | 2 | 157 | 300 | E. faecalis | 177 | PSSR PSCR |

| 5 | 77 | M | + | + | 1 | 420 | 600 | MSCNS MRCNS E. faecalis |

14 | POSSR |

| 6 | 78 | M | + | + | 1 | 131 | 150 | MSCNS | 29 | POSSR |

| 7 | 78 | F | – | – | 1 | 172 | 300 | P. acnes | 50 | POSSR |

| 8 | 64 | M | + | – | 1 | 130 | 400 | P. acnes | 42 | POSSR CSIS |

| 9 | 67 | M | – | – | 1 | 156 | 700 | MRCNS | 83 | conservative |

| 10 | 72 | M | – | – | 1 | 215 | 1600 | P. acnes | 33 | POSSR |

| 11 | 78 | M | + | – | 1 | 217 | 50 | P. acnes | 61 | POSSR |

| 12 | 69 | F | + | + | 1 | 125 | 216 | K. pneumoniae | 19 | I & D |

| 13 | 79 | M | – | + | 2 | 253 | 1050 | MRCNS | 12 | POSSR |

| 14 | 75 | F | – | + | 1 | 156 | 270 | MSSA | 12 | POSSR |

| Ave | 72.7 | 1.21 | 184.6 | 495.4 | 41.6 |

ASCR, anterior secondary cage removal; CSIS, closed suction irrigation system; DM, diabetes mellitus; E. faecalis, Enterococcus faecalis; ETD, elapsed time to diagnosis; I & D, irrigation and debridement; K. pneumoniae, Klebsiella pneumoniae; MRCNS, methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative Staphylococcus; MSCNS, methicillin-susceptible coagulase-negative Staphylococcus; MSSA, methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus; P. acnes, Propionibacterium acnes; PLIF, posterior lumbar interbody fusion; POSSR, posterior one-stage simultaneous revision; PSCR, posterior secondary cage removal; PSSR, pedicle screw system removal; SSI, surgical site infection.

Of the 13 patients who underwent surgery for SSI, 10 had P. acnes (Group A, n = 4, No. 7, 8, 10, and 11) or CNS (Group B, n = 6, No. 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, and 13) as the causative bacterial species. Age, sex, number of segments, presence of diabetes mellitus, operation time, blood loss, minimum value of CRP on hematological examination at >1 week after PLIF, the elapsed time to diagnosis (ETD), the presence of clinical findings such as heat, redness, swelling, and discharge from the wound, and the time from initial surgery for infection until CRP became negative (healing time) were retrospectively compared between the two groups.

3. Theory/calculation

Differences were statistically analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test for quantitative parameters and chi-squared tests for dichotomous parameters. The statistical software package StatView-J 5.0 (SAS institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for all calculations. Differences were considered significant when the P-value was <0.05.

4. Results

We identified 14 patients with SSI that were not obvious superficial SSIs (Table 1). The SSI was ultimately resolved in all cases. The average age of the patients who underwent PLIF was 72.7 years (range: 64–79 years). The patients included 11 males and 3 females, and 3 patients had 2 fusion segments while 11 patients had one fusion segment. Diabetes mellitus was present in seven patients. The average ETD was 41.6 days (range: 15–177 days). The causative bacterial species were as follows: methicillin-resistant CNS (MRCNS) (5 cases; No. 1, 2, 3, 9, and 13); methicillin-susceptible CNS (MSCNS) (1 case; No. 6); methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) (1 case; No. 14); a combination of Enterococcus faecalis, MRCNS, and MSCNS (1 case; No. 5); Klebsiella pneumoniae (1 case; No. 12); P. acnes (4 cases; No. 7, 8, 10, and 11); and E. faecalis alone (1 case; No. 4). The average period to achieve negative CRP laboratory test results after the first operation for infection was 74.4 days (range: 12–253 days). The average duration of intravenous antibiotics after the first surgery for infection was 53.8 days (range: 17–128 days). In all patients who underwent surgery for infection, the intraoperative findings revealed that the pus extended to the subfascia and that there was pus accumulation in the intervertebral space around the cages. Screw loosing was recorded in 2 patients (No. 4 and 11). Bone union was achieved in 13 patients. In one patient (No. 4), in whom bone union was not achieved, SSI was not cured, and a second surgery was performed to remove the cages after removing the pedicle screw system implants in the first surgery. Therefore, implant removal may have had a negative effect on bone union.

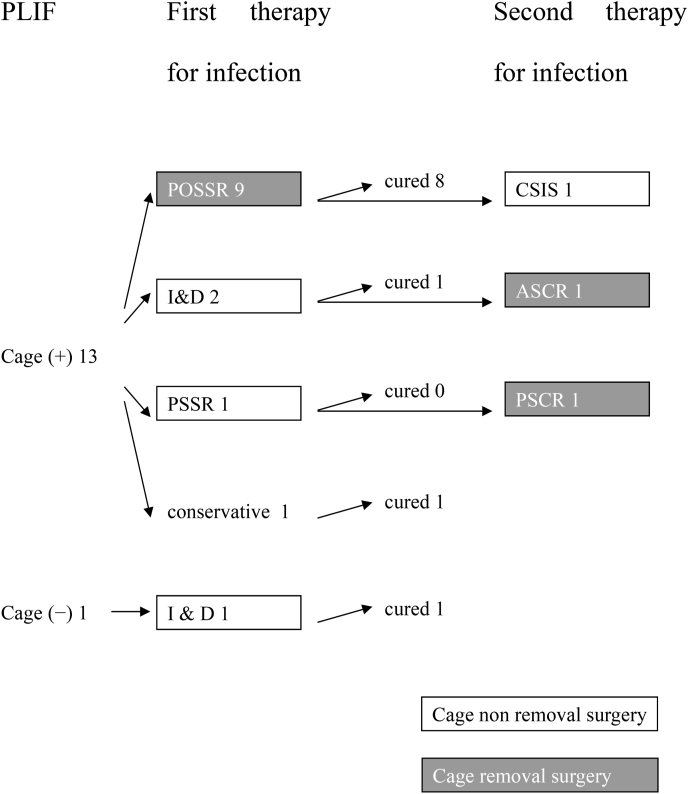

The treatment progression of the 14 patients is described in Fig. 1. In 13 patients, surgery was required to eradicate the infection. We ultimately performed surgeries to remove the cages in 11 patients (No. 2–8, 10, 11, 13, and 14) and pedicle screw implants in one patient (No. 4). In 10 of the 11 patients (No. 3–8, 10, 11, 13, and 14) we removed the cages with a posterior approach and by an anterior approach in one patient (No. 2). In posterior one-stage simultaneous revision (POSSR), the cages are removed and replaced with the autologous iliac bone blocks and the pedicle screw system is preserved. If the screws were loose, they were removed and inserted into the upper or lower normal pedicle. POSSR was performed in nine patients (No. 3, 5–8, 10, 11, 13, and 14) and a closed suction irrigation system (CSIS) with a second surgery was required in one patient (No. 8). In one patient (No. 11), two loose screws were removed. New screws were then inserted into the upper pedicles. In one patient (No. 1) who underwent a PLIF with cages, we eradicated the infection by irrigation and debridement (I & D) surgery. We were able to preserve the cages and pedicle screw system implants in that patient. In another patient (No. 12) who underwent PLIF with auto-bone only, only one I & D surgery was required, and the intradiscal auto-bone and pedicle screw system implants were preserved. In three patients (No. 2, 4, and 8), surgery for infection was required twice, and two (No. 2 and 4) had the cages preserved during the first surgery and removed during the second surgery. The other patient (No. 8) underwent POSSR first, but the SSI was not eradicated, and a second surgery was required for CSIS. The cage removal itself was not difficult. In one patient (No. 9) of SSI caused by MRCNS, no surgery was performed because intravenous antibiotic therapy started after the intradiscal puncture was effective for eradicating the infection.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart showing the treatment progression.

As shown in Table 2, of the 13 patients who underwent surgery for the SSI, 10 had P. acnes (Group A, n = 4, No. 7, 8, 10, and 11) or CNS (Group B, n = 6, No. 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, and 13) as the causative bacterial species. Between the two groups, there were no significant differences in age, sex, number of segments, diabetes mellitus, operation time, blood loss, minimum value of CRP on hematological examination at >1 week after PLIF or healing time; however, a significant difference (P = 0.011) in the ETD was observed between the two groups (Table 2). The presence of clinical findings such as heat, redness, swelling, and discharge from the wound was statistically significantly different between the two groups (P = 0.048; Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of groups A and B.

| Variable | Group A (n = 4) | Group B (n = 6) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 73 (64–78) | 75.1 (67–79) | 0.7491 |

| Sex (male/female) | 4/0 | 5/1 | 1 |

| No. of PLIF segments | 1 | 1.33 | 0.3938 |

| 1 | 4 | 4 | |

| 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| DM (−/+) | 2/2 | 3/3 | 1 |

| Operation time (min) | 183.5 (130–217) | 209.5 (117–420) | >0.9999 |

| Blood loss | 587.5 (50–1600) | 516.6 (150–1600) | >0.9999 |

| ETD | 46.5 (33–61) | 17.7 (12–29) | 0.0105 |

| Clinical findings (−/+) | 4/0 | 1/5 | 0.0476 |

| CRP | 0.343 (0.22–0.58) | 2.852 (0.15–7.21) | 0.0881 |

| Healing time (day) | 49 (20–86) | 112 (14–253) | 0.3938 |

Clinical findings, heat, redness, swelling, and discharge from the wound; CRP, minimum value of C-reactive protein on hematological examination at >1 week after posterior lumbar interbody fusion; Healing time, the period to achieve negative CRP laboratory test results after the first operation for infection; PLIF, posterior lumbar interbody fusion; ETD, elapsed time to diagnosis; DM diabetes mellitus.

Data analysis: Mann–Whitney U test.

5. Discussion

The incidence of SSI in instrumented PLIF ranges from 1.37% to 7.2%.1, 2, 3,8 These infections are classified according to the criteria of the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention into three groups: superficial incisional SSI, deep incisional SSI, and organ/space SSI, which involves any part of the body that was opened or manipulated during an operative procedure.11 The most common type of SSI in PLIF is spondylitis caused by infectious cages.1, 2, 3 However, it is difficult to distinguish from aseptic response9,12 and accurately determine the infectious range when diagnosing the SSI, and surgery may be required to eradicate the infection. It can be especially difficult to distinguish deep incisional SSI from organ/space SSI with magnetic resonance imaging and/or computed tomography images, which could contain artifacts caused by metal implants. Kanna et al. classified wound complications that occurred after transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion into 5 types, as follows: type 1 (suprafascial necrosis), type 2 (wound dehiscence), type 3 (pus around screws and rods), type 4 (bone marrow edema), and type 5 (pus in the disc space). They considered type 3 to deep SSI and types 4 and 5 to organ/space SSI. No causative organisms were identified in patients with types 4 and 5; however, they were identified in 9 of 10 type 3 patients. These observations indicated the possibility of metallurgical response to pedicle screw implant and cage.12 In this study, we identified 14 patients with SSI that were not obvious superficial incisional SSIs without distinguishing between deep incisional SSI and organ/space SSI.

Ultimately, all cases were diagnosed by the culture results although in 1 patient (No. 4), it took 177 days to diagnose the SSI despite suspecting the presence of infection. In many studies, the causative bacterial species could not be identified in some patients.1,2,4,6,7,9,10,12,13 The causative species in patient No. 9 was determined using the disc puncture method under fluoroscopy before starting intravenous antibiotic treatment. The causative species in the remaining 13 patients were determined through preoperative puncture and/or intraoperative drainage or via culturing. If anaerobic culture is not performed, SSI caused by an anaerobic bacterial species like P. acnes cannot be diagnosed. Lee et al. suggested that in some cases without anaerobic culture might be caused by P. acnes.1 In addition, Richards found that P. acnes required an extended duration (7–10 days) of incubation to be identified, and that if the final culture reading was completed at 72 h, the causative microorganism clearly could have been missed.4 Thus, it is important to investigate and identify the causative microbacterium for the successful treatment of SSIs.

The ETD is used to differentiate between early and late infections. Cutoff times of 90 days or 3 months have been used by some authors,1,13, 14, 15 and some recommend implant removal for late infections.1,14,16 Maruo and Berven treated 166 SSI cases after instrumented spinal surgery. They reported that a high rate of treatment failure occurred in cases of late infection.13 Hedequist et al. showed that debridement of a chronic infection without implant removal results in areas underneath the rods and spinal anchor points that are not thoroughly debrided, leaving behind pockets of infected tissue, and immediate implant replacement would lead to early reinfection because of the colonized tissue bed.14 However, Tokuhashi reported the conservative follow-up of a patient with an epidural abscess and discitis 1 year after an instrumented PLIF using a metal cage without surgical intervention.17 They described that the outcome was fortunate as the conservative treatment was unusual and was not recommended as standard treatment.17 Other studies stated that removal of the implants was not necessary in early infections.8,15,16

Sierra-Hoffman et al. reported that 17 (90%) of 19 patients were cured without instrumentation removal within 30 days of the onset of infection.16 Mirovsky et al. reported eight cases who were diagnosed with deep SSI after PLIF.8 In two patients, pedicle screw system implants were supplemented with rectangular cages or spacers, and in six patients, threaded cages were applied as stand-alone devices. All patients’ ETDs were within 90 days. They reported that none of the patients required instrumentation removal.8 In our study, 13 patients whose ETDs were within 90 days were cured without the removal of the pedicle screw implants. Only one patient (No. 4) whose ETD was 177 days underwent the removal of the pedicle screw system implants as the first surgery for infection. However, the SSI was not eradicated, and the cage removal surgery was performed as the second surgery for infection. In this case, the pedicle screws were loosened and removed prior to cage removal. It could not be determined whether the removal of the pedicle screw implant was necessary to control the infection.

Few studies have described the criteria for cage removal. Mirovsky et al. reported that cage removal is not necessary. They managed four of six patients who underwent surgery for deep SSI without cage removal, but they did have to reposition the PLIF cages in two patients.8 Lee et al. treated 20 patients whose infections were organ/space SSIs. When 4 weeks of intravenous antibiotics did not show any response, or when neurological symptoms developed due to instability, cage retropulsion, or epidural abscess, surgery was performed. In total, 10 patients underwent surgery, and 9 had cages removed and auto-bone blocks were grafted. In that study, the attempt to remove the cage in one case was not successful.1 Chang et al. treated 32 patients whose infections were organ/space SSI post-transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion and compared the radiographical and functional outcomes between those who underwent cage removal procedures and those who retained it. They suggested that the infected cage should be removed because the cage-retained group showed poorer outcomes.9 Liao et al. treated 28 patients with postoperative spondylodiscitis who underwent revision surgeries to salvage their infections. In this study, the cages of 7 patients could not be removed, but the instrumentation was extended on healthy vertebrae to suppress the SSI.10 The authors stated that providing additional spinal stability and fusion were the key points for the successful treatment of spondylitis.10 In our study, it was difficult to approach the cages in some cases, but it was not difficult to remove the cage itself because the infected cages did not unify with the bone. In our study, initially three patients (No. 1, 2, and 4) who had undergone an initial surgery for infection preserved the cages. We treated and healed the first patient (No. 1) by I & D and retained the cages and the pedicle screw implants. In two other patients (No. 2 and 4), we could not control the SSI while preserving the cages. We were unable to retain the cages in one patient (No. 2) whose ETD was 20 days and pedicle screw implant was not loose.

In case No. 4, which was the patient who had the pedicle screw implants and cages removed, bone union was not achieved. Mirovsky et al.8 and Liao et al.10 stated that stability imparted by the pedicle screw implants has been shown to play an important role in controlling infection and supporting bone union. From these experiences and previous reports, the therapeutic strategy of removing the cages as much as possible, grafting the primary auto-bone, and preserving the pedicle screw system (including removal of the loose screw, extension of the fixed range, and stabilization of the spine) when SSI after PLIF is diagnosed, except in cases of obvious superficial incisional SSI, is effective.

Few studies have described SSIs post-PLIF caused by P. acnes in adult patients. Maruo et al. reported 16 patients with SSIs caused by P. acnes after whole spine operations including decompression, fusion, tumor excisions, and removal and/or reimplantation of hardware.13 Mirovsky et al. described one SSI post-PLIF in an adult patient whose ETD was 37 days and the causative bacteria was P. acnes8; this ETD is similar to that of all patients in Group A in our study.

There were several limitations to this study. First, the number of cases was small. Second, all potential risk factors were not considered due to the retrospective design of the study.

6. Conclusions

POSSR is an effective treatment for deep SSI post-PLIF. There was a significant difference in the ETD and clinical findings among cases caused by different microbacterial species. These differences are useful in predicting the causative bacteria and allow for the selection of appropriate antibiotics before the culture results are available.

Funding sources

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributions

Koki Hosozawa, Yudai Tanaka, Koki Kishimoto, Kosuke Sakata: Investigation.

Hirokazu Iwata: Data curation and Formal analysis.

Seiji Okada: Validation.

Tsuyoshi Nakai: Project administration.

Institutional Ethical Committee approval

This study was approved by the Itami City Hospital ethics committee (approval code 1249).

Informed consent

The need for written informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Shigeko Nakamura, Email: shigeko50@hotmail.com.

Seiji Okada, Email: seokada@ort.med.osaka-u.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Lee J.S., Ahn D.K., Chang B.K., Lee J.I. Treatment of surgical site infection in posterior lumbar interbody fusion. Asian Spine J. 2015;9:841–848. doi: 10.4184/asj.2015.9.6.841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim J.H., Ahn D.K., Kim J.W., Kim G.W. Particular features of surgical site infection in posterior lumbar interbody fusion. Clin Orthop Surg. 2015;7:337–343. doi: 10.4055/cios.2015.7.3.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahn D.K., Park H.S., Choi D.J., et al. The difference of surgical site infection according to the methods of lumbar fusion surgery. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2012;25:E230–E234. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e31825c6f7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richards B.R., Emara K.M. Delayed infections after posterior TSRH spinal instrumentation for idiopathic scoliosis: revisited. Spine. 2001;26:1990–1996. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200109150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nandyala S.V., Schwend R.M. Prevalence of intraoperative tissue bacterial contamination in posterior pediatric spinal deformity surgery. Spine. 2013;38:E482–E486. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182893be1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hahn F., Zbinden R., Min K. Late implant infections caused by Propionibacterium acnes in scoliosis surgery. Eur Spine J. 2005;14:783–788. doi: 10.1007/s00586-004-0854-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ho C., Skaggs D.L., Weiss J.M., Tolo V.T. Management of infection after instrumented posterior spine fusion in pediatric scoliosis. Spine. 2007;32:2739–2744. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31815a5a86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mirovsky Y., Floman Y., Smorgick Y., et al. Management of deep wound infection after posterior lumbar interbody fusion with cages. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2007;20:127–131. doi: 10.1097/01.bsd.0000211266.66615.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang C.W., Fu T.S., Chen W.J., Chen C.W., Lai P.L., Chen S.H. Management of infected transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion cage in posterior degenerative lumbar spine surgery. World Neurosurg. 2019;126:e330–e341. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liao J.C., Chen W.J. Revision surgery for postoperative spondylodiscitis at cage level after posterior instrumented fusion in the lumbar spine-Anterior approach is not absolutely indicated. J Clin Med. 2020;9:3833. doi: 10.3390/jcm9123833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horan T.C., Gaynes R.P., Martone W.J., Jarvis W.R., Emori T.G. CDC definitions of nosocomial surgical site infections, 1992: a modification of CDC definitions of surgical wound infections. Am J Infect Control. 1992;20:271–274. doi: 10.1016/s0196-6553(05)80201-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanna R.M., Renjith K.R., Shetty A.P., Rajasekaran S. Classification and management algorithm for postoperative wound complications following transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. Asian Spine J. 2020;14:673–681. doi: 10.31616/asj.2019.0247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maruo K., Berven S.H. Outcome and treatment of postoperative spine surgical site infections: predictors of treatment success and failure. J Orthop Sci. 2014;19:398–404. doi: 10.1007/s00776-014-0545-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hedequist D., Haugen A., Hresko T., Emans J. Failure of attempted implant retention in spinal deformity delayed surgical site infections. Spine. 2009;34:60–64. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31818ed75e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerometta A., Rodriguez Olaverri J.C., Bitan F. Infections in spinal instrumentation. Int Orthop. 2012;36:457–464. doi: 10.1007/s00264-011-1426-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sierra-Hoffman M., Jinadatha C., Carpenter J.L., Rahm M. Postoperative instrumented spine infections: a retrospective review. South Med J. 2010;103:25–30. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181c4e00b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tokuhashi Y., Ajiro Y., Umezawa N. Conservative follow-up after epidural abscess and diskitis complicating instrumented metal interbody cage. Orthopedics. 2008;31:611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]