Highlights

-

•

HIU can unfold and break down the aggregates of ISPP significantly.

-

•

HIU increased surface hydrophobicity and free sulfhydryl groups content of ISPP.

-

•

Rheology behavior of ISPP and ISSP/EWP was promoted by HIU treatment.

-

•

Reduction of the particle size induced by HIU improved emulsification of ISPP.

-

•

Stable secondary structure of ISPP improved gel strengthens and firmness.

Keywords: Ultrasonic modification, Emulsifying property, Gelling property, Rheology analysis

Abstract

The denaturation and lower solubility of commercial potato proteins generally limited their industrial application. Effects of high-intensity ultrasound (HIU) (200, 400, and 600 W) and treatment time (10, 20, and 30 min) on the physicochemical and functional properties of insoluble potato protein isolates (ISPP) were investigated. The results revealed that HIU treatment induced the unfolding and breakdown of macromolecular aggregates of ISPP, resulting in the exposure of hydrophobic and R–SH groups, and reduction of the particle size. These active groups contributed to the formation of a dense and uniform gel network of ISPP gel and insoluble potato proteins/egg white protein (ISPP/EWP) hybrid gel. Furthermore, the increase of solubility and surface hydrophobicity and the decrease of particle size improved the emulsifying property of ISPP. However, excessive HIU treatment reduced the emulsification and gelling properties of the ISPP. Meanwhile, HIU treatment changes the secondary structure of ISPP. It could be speculated that the formation of a stable secondary structure of ISPP initiated by cavitation and shearing effect might play a dominant role on gel strengthens and firmness. Meanwhile, the decrease in relative content of β-turn had a positive effect on the formation of small particle to improve emulsifying property of ISPP.

1. Introduction

Potato (Solanum tuberosum) proteins are the second highest protein content of crops per hectare, which have more nutritious than other plant proteins, such as wheat protein, characterized by high lysine content [1]. Potato proteins have some positive effects on human health, such as antibacterial effects [2], antioxidant effects [2], [3], and regulation of blood pressure and serum cholesterol [4], [5]. However, they gained less attention in the food industry, and were usually discarded as waste in potato starch processing. Moreover, the wastewater also called as potato fruit juice (PFJ), contains approximately 25 g potato protein in per kilogram PFJ [6], and around 5–12 m3 PFJ will be produced for per ton potato processed [7]. Therefore, collecting protein from PFJ for industrial utilization is meaningful. However, the commercial potato proteins usually obtained by acid precipitation and heat method (normally more than 90 °C), which will cause proteins denaturation and lower solubility [8]. The denaturized potato protein is not suitable for food formulations because of the bitter taste and lower solubility. Furthermore, when potato proteins are recovered by acid precipitation, they usually have a dark colour and a strong cooking flavor [9]. So that developing the functional properties of commercial potatoes protein is necessary to broaden their potential applications.

The solubility and functional properties of proteins can be enhanced and modified by applying various innovative non-thermal methods, such as high-intensity ultrasound [10], high pressure [11] and pulsed electric fields [12]. Amongst the processing approaches, high-intensity ultrasound (HIU) technology is a safe and environmentally friendly alternative for protein modification [10], [13]. HIU produces its effects in liquid media through acoustic cavitation. Ultrasounds are transmitted in the form of waves that alternately compress and stretch the molecular structure of the medium through which they pass. Tiny cavities (microbubbles) are produced during each “stretching” phase and are then collapsed violently in the subsequent cycles, creating enormous shear forces near the bubble. Such a jet causes damage to solid surfaces, leading to a decrease in particle size and dispersion throughout the medium [14]. At present, HIU is successfully applied to improve the emulsification, foaming, viscosity and gelation characteristics of proteins. For instance, a better emulsifying property of soybean protein, walnut protein and myofibrillar protein was obtained after HIU treatment [10], [13], [15]. The foaming ability of whey protein and the gelation property of soybean protein were enhanced by HIU treated [16].

This study aimed to investigate whether HIU treatment can improve the functional properties of insoluble potato protein isolates. The effects of varying HIU intensities (200, 400, and 600 W) and treat times (10, 20, and 30 min) on the secondary and tertiary structure of insoluble potato protein (ISPP) were determined by comparing their solubility, particle size distribution, surface hydrophobicity, and free sulfhydryl groups content. The relationship between structural and functional properties affecting the emulsification and gelation of the insoluble potato proteins isolates was subsequently discussed. Meanwhile, insoluble potato proteins/egg white protein (ISPP/EWP) hybrid gels were also prepared in this study, in which egg white protein (EWP) could covalently crosslink with the other protein improving the texture, stickiness, and elasticity of gels [17].

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Commercial potato protein isolates with 5.79 ± 0.05% w/w moisture, 85.21 ± 0.13% w/w protein content, 5.8 ± 0.2% w/w ash, and 1.47 ± 0.06% w/w carbohydrate content were purchased from Kaimeite Technology Ltd (Beijing, China). Egg white protein with 6.68 ± 0.05% w/w moisture, 83.19 ± 0.21% w/w protein content, 5.9 ± 0.2% w/w ash, and 1.12 ± 0.01% w/w carbohydrate content, was purchased from Kangde egg industry (Jiangsu, China). BCA Protein Assay Kits were purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific, Inc. (Shanghai, China). All other chemicals and reagents were of analytical grade and were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich LLC. (Shanghai, China).

2.2. Preparation of insolubilized protein

Potato proteins (20 g) were homogenized in 1000 mL of distilled water using a magnetic stirrer (500 rpm) at 25 °C for 12 h. The protein solution was then centrifuged at 10 000×g for 30 min at 4 °C (Beckman Coulter, Inc. CA, USA), followed by freeze-drying the precipitated proteins at −50 °C after three rounds of washing. The freeze-dried insolubilized potato protein (ISPP) was ground into powder and passed through a 70-mesh sieve for further processing. The composition of the ISPP was subsequently evaluated by SDS-PAGE. ISPP bands between 35 and 75 kDa, especially those at 45, 71, and 75 kDa, were dominant, indicating that patatin and others were the dominant fractions present in the ISPP [18]

2.3. Ultrasonic treatment

Ultrasonic treatments were performed using an ultrasonic processor (VCX800, Sonics & Materials Inc., Newtown, CT, USA) equipped with a 20 kHz ultrasonic probe (fuse size: 13 amps, sloblo). The ISPP powder was dispersed in distilled water at a concentration of 20 g/L (150 mL) and subjected to varying ultrasonic intensities (200, 400, and 600 W) for 20 min with a pulse time of 5 s and intermittent time of 5 s. The ISPP solutions were sonicated for varying times (10, 20, and 30 min) at 400 W and then placed in an ice bath to avoid overheating. Samples without ultrasonic treatment served as controls. All ultrasound-treated and untreated samples were freeze-dried and stored at 4 °C, awaiting further analysis.

2.4. Preparation of ISPP and ISPP/EWP hybrid gels

The ultrasound-treated and untreated ISPP samples were dissolved in distilled water (15% w/w) for ISPP gels preparation. The ultrasound-treated ISPP samples (400 W for 0, 10, 20, and 30 min) was mixed with EWP at a ratio of 1:1 and dissolved in distilled water (15% w/w) for ISPP/EWP hybrid gels preparation. The protein suspensions were magnetically stirred at 500 rpm for 8 h and then placed in a Thermomixer (Eppendorf, German) set at 85 °C for 30 min to gel. The ISPP gels and ISPP/EWP hybrid gels were subsequently stored at 4 °C for 12 h and then used for further water and oil holding capacities, texture, and scanning electron microscopy analysis.

2.5. Surface hydrophobicity (H0)

The surface hydrophobicity of samples was measured following the method described by Ibrahim et al. [19] with slight modifications. Sample solutions (1 mg/mL) of different ultrasonic treatments were mixed with phosphate buffer (10 mM, at pH 7.0) to dilute them to protein solutions with concentrations of 0.5, 0.1, 0.025, 0.005, and 0.001 mg/mL. The protein solutions were then centrifuged at 10 000×g for 20 min at 25 °C, followed by adding 30 μL of ANS (1-anilinonaphthalene-8-sulfonic acid) in phosphate buffer (10 mM, at pH 7.0) to 3 mL of the protein solutions with different concentrations. The fluorescence intensity of the mixtures was measured using a fluorescence spectrophotometer F-2500 (Hitachi, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) with excitation and emission wavelengths of 385 nm and 490 nm, respectively. The excitation and emission slits had a width of 2.5 nm.

2.6. Free sulfhydryl groups (R–SH)

The number of free sulfhydryl groups from samples was determined using the method described by Deng et al. [20] with some modifications. Protein samples (100 mg) were dispersed in 10 mL of sodium phosphate buffer (containing 1 mM EDTA, 1% SDS, at pH 8.0) and then centrifuged at 10 000×g for 10 min at 25 °C to obtain the supernatant. Ellman’s reagent solution (DTNB (5,5′-Dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid)) in Tris-Gly buffer, 4 mg/mL) (0.1 mL) was then added to 3 mL of the supernatant, followed by measuring of the absorbance of the resultant solution at 412 nm after 1 h of oscillation treatment at 25 °C. The supernatant of the same sample without Ellman’s reagent was used as a blank control. The total number of free sulfhydryl groups (μmol/g protein) was subsequently calculated using an extinction coefficient of 13 600 M−1cm−1.

2.7. Fluorescence spectroscopy

The fluorescence spectrum of ultrasound-treated and untreated ISPP was tested using a fluorescence spectrophotometer F-2500 (Hitachi, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The freeze-dried samples (10 mg) were dispersed in 20 mL of sodium phosphate buffer (10 mM, at pH 7.0) and extracted for 1 h at 25 °C. The protein solution was then centrifuged at 10 000×g for 15 min to obtain the supernatant. The fluorescence spectrum of the supernatant (3 mL) was subsequently determined under the following conditions: an excitation wavelength of 285 nm, a scanning range of 300–450 nm, an excitation and emission site width of 2.5 nm, and a scanning speed of 300 nm/min.

2.8. Fourier transforms infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

FTIR spectra were measured using a Thermo Nicolet 67 FTIR (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Madison, WI, USA). Sample (4 mg) was placed on the head of the ATR crystal (2 mm diameter), followed by the generation of spectra from the mid-infrared range from ca. 4000–400 cm−1 at a resolution of 4 cm−1. A total of 64 repetitive scans were accumulated and analyzed using OMNIC 8.0 software (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Madison, WI, USA) for each FTIR spectrum. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate and then averaged to one spectrum. Pre-processing methods including baseline correction, derivative, and Savitzky-Golay smoothing were also performed on the FTIR spectra.

2.9. Particle size distribution

The particle size distribution of the ultrasound-treated and untreated proteins was measured using a laser particle size analyzer S3500 (Malvern Instrument Ltd., UK). The protein samples (10 mg/mL) were dispersed in distilled water using a magnetic stirrer (500 rpm) for 2 h. 1 mL of diluted samples were placed into a measuring cell. The refractive index and absorption parameter was set at 1.322 and 0.1, respectively.

2.10. Protein solubility

Protein solubility was measured as described by Zhang et al. [21] with minor modifications. The ultrasound-treated and untreated proteins solutions (20 g/L) were centrifuged at 10 000×g for 20 min at 25 °C. The protein concentration of the supernatant was then measured using the BCA protein assay kit.

2.11. Rheology analysis

The viscoelasticity of ultrasound-treated and untreated proteins was measured using a rheometer (Physica MCR 301, Anton Paar, Graz, Austria), with parallel-plate geometries (diameter, 50 mm; 131 gap, 1 mm) as described by Zhang et al. [22]. The ISPP samples (15% w/v, in phosphate buffer at pH 7.0) were heated from 25 to 85 °C at a rate of 5 °C/min and then cooled to 25 °C under a fixed frequency at a range of 0.1–10 Hz and a constant deformation of 0.1%. Storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G″) changes caused by changing temperature were recorded to assess the rheological properties of the protein samples.

2.12. Emulsifying property

The emulsifying property of the samples was measured as described by Deng et al. [10] with minor modifications. The protein samples (3 mg) were homogenized with 27 mL deionized water, followed by emulsification of soy oil and sample solution in a ratio of 1:3 for 2 min using a high-speed homogenizer (CTK 10 K, Brookfield, USA) at 10,000 rpm/min.

The emulsification activity index (m2g−1) and emulsification stability index (min) of the samples were then calculated as follows:

where A0 is the absorbance of the sample at 0 min, A10 is the absorbance of the sample at 10 min, N is the dilution factor of 100, T is the constant 2.303, L is the light path of the colorimetric cell 1 cm, ∅ is the oil phase volume fraction (0.25), and C is the protein concentration before the emulsion is formed.

2.13. Water and oil holding capacities (WHC and OHC)

The WHC and OHC were determined as described by Zhang et al. [22] with some modifications. Freeze-dried protein gel samples (1.0 g) and 5 mL of deionized water (or oil) were placed in a pre-weighted centrifuge tube and vortexed for 5 min. They were left to stand at 25 °C for 30 min and then centrifuged at 10 000×g for 20 min to obtain the supernatant (water or oil).

The water and oil holding capacities of the samples were then calculated as follows:

where m1 is the mass of the sample, m2 is the mass of the centrifuge tube, and m3 is the total mass of the centrifuge tube and samples after removing the supernatant.

2.14. Texture analysis

The texture of the samples was analyzed using a texture analyzer (CTK 10 K, Brookfield, Berwyn, PA, USA). The gel samples were cut into rd 12.5 mm × h 12 mm and then compressed using a P/0.5R probe. The TPA parameters set were: a pre-test speed of 5 mm/s−1, test speed of 0.5 mm/s−1, post-test speed of 2 mm/s−1, 50% deformation, and a trigger force of 5.0 g. The analyses for each set of samples were repeated five times.

2.15. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The microstructure of the gel samples was observed using a scanning electron microscope (S-570, Hitachi, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at an accelerating voltage of 10 kV. The samples were coated with a thin gold film in a vacuum evaporator, and their X500 magnification images were subsequently obtained.

2.16. Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the SPSS statistical software (2017, IBM, New York, USA) and expressed as means of three replicates. The variance between the means was assessed by one-way ANOVA, with the significance threshold set at p < 0.05 (Duncan’s new multiple range test). All graphs were drawn using the Origin94 software (OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA, USA).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Surface hydrophobicity (H0)

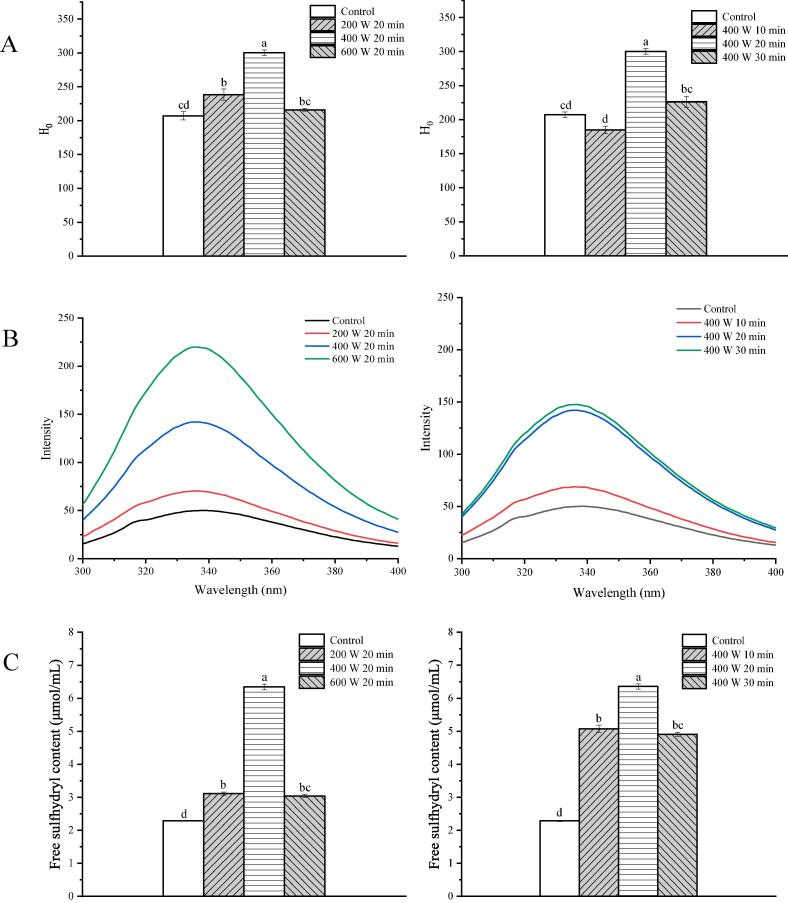

Surface hydrophobicity (H0) reflects the density of hydrophobic groups exposed on the surfaces of protein molecules. It monitors changes in the protein’s tertiary and quaternary structures. The H0 of ultrasound-treated samples was significantly higher than those of the control (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1A). Notably, the H0 of ISPP samples treated for 20 min significantly increased with an increase in the ultrasonic voltage from 200 to 400 W but decreased with voltage increment (600 W). The increase in H0 was attributed to the promotion of the breakdown of the macromolecular aggregates of ISPP upon cavitation and acoustic streaming, thereby exposing the partially buried interior hydrophobic groups [14], [23]. Meanwhile, it was another reason of the increase of H0 that the energy liberated during bubble collapse provided the energy of hydrophobic interaction [14]. Similar results have also obtained in pea protein and whey isolates [20], [24], showing that the quaternary structures of proteins were disrupted under HIU treatment. Moreover, the H0 of samples treated for 10 and 30 min decreased compared to samples treated for 20 min. The decrease in H0 for samples treated for 10 min was owing to the non-covalent aggregation of unstable aggregates in ISPP solution. And the decrease in H0 for samples treated with a high ultrasonic power and longer time (at 600 W, treated for 30 min) is attributed to the reformation of molecular aggregates caused by sonication [23].

Fig. 1.

Surface hydrophobicity (A), intrinsic fluorescence spectra (B) and free sulfhydryl groups content (C) of ISPP treated by HIU at different intensity and time. Different letters on the top of the column represent a significant difference (p < 0.05).

3.2. Fluorescence spectroscopy

Intrinsic fluorescence is a useful index of changes in the tertiary structure of proteins. It is based on the microenvironmental changes of tryptophan and tyrosine residues [25]. Fig. 1B shows the fluorescence intensity of the protein samples. The maximum fluorescence emission occurred at 336 nm without changes under different treatments. The fluorescence intensity of the treated samples increased with increasing sonication intensity and time compared to the control, indicating changes in the local microenvironments of tryptophan and tyrosine residues [26]. Changes in the tertiary structure of ISPP due to the sonication effect consequently buried tryptophan and tyrosine residues into hydrophobicity area, leading to an increase in the fluorescence intensity [14], [26]. The intrinsic fluorescence results were consistent with the surface hydrophobicity measurements, suggesting that sonication causes some structural changes in proteins.

3.3. Free sulfhydryl groups (R–SH) content

The cross-linking degree of proteins was quantified by determining the free R–SH group content. The R–SH group content of ISPP increased after ultrasound treatment (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1C). Notably, the surface sulfhydryl content increased significantly with the increasing ultrasound time and intensity. The increase is attributed to the breaking of disulfide bonds to form SH groups and the exposition of SH groups embedded inside upon HIU treatment. The cavitation phenomenon of HIU induces the action of shear forces and shock waves, which break disulfide bonds between domain and unfolding of aggregates [14]. However, high ultrasound power and long ultrasound time (600 W for 20 min and 400 W for 30 min) reduced the surface sulfhydryl content, a phenomenon attributed to the conversion of the free R–SH group to intra- and intermolecular disulfide bond linkage [23]. The increase of free R–SH group content indicated that the breakdown of the macromolecular aggregates of ISPP, and promoted the solubility of protein molecules, agreeing with the conclusion in Section 3.1 and 3.5. These results are similar to those of Amiri et al. [27] and Zhu et al. [13]. In contrast, some studies postulate that HIU processing reduces the R–SH contents of proteins [10]. For example, it has been reported that ultrasound treatment could generate free radicals and superoxide, which oxidize the free R–SH group to form sulfinic and sulfonic acid [25].

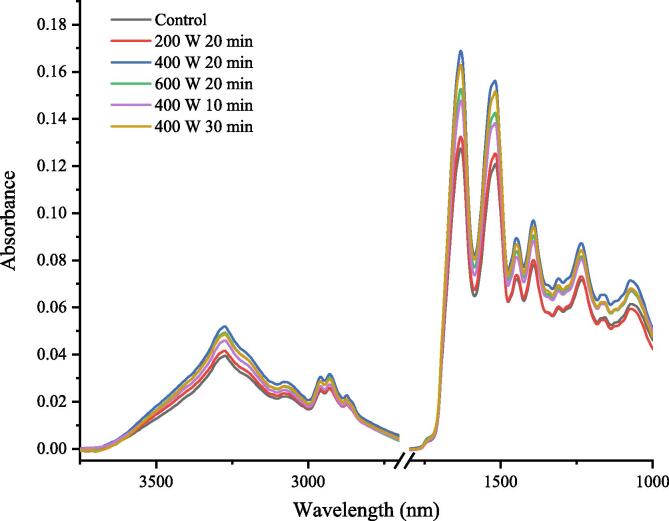

3.4. FTIR analysis

The functional properties of proteins are related to a complex series of structural changes that affect the protein network formation. Changes at secondary structure in proteins were determined by FTIR. The spectra are showed in Fig. 2. Compared with the control, cavitation brought by ultrasonic caused structural changes. Peaks absorption at 1615–1637 and 1682–1700 cm−1, 1646–1664 cm−1, 1637–165 cm−1, 1664–1681 cm−1 associated with β-sheet, α-helix, β-turn and random coil, respectively [25], [28]. The most notable secondary structural changes in ISPP were an increase around intensity between 1600 and 1700 cm−1, indicating an increase in the proportion of amide I band.

Fig. 2.

FTIR spectra of ISPP treated by HIU at different intensity and time.

As shown in Table 1, compared to the control, the relative content of α-helix and β-sheet increased and the relative content of random coil and β-turn decreased after HIU treatment. The cavitation effect caused by ultrasound changed the secondary structure of ISPP, resulting in the decomposition of random coil and β-turn and formation of α-helix and β-sheet. The higher content of α-helix and β-sheet provided a more stable structure of ISPP, leading to a higher temperature of thermal denaturation. High content of β-sheet might lead to the increase in hydrophobic interaction, which was the main driving force for protein folding, which would attribute to protein aggregation and gel formation, resulting in an improvement in gel texture [29].

Table 1.

Effect of HIU treatments on secondary structure of ISPP.

| Second structure (%) | Control | 20 min |

400 W |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 200 W | 400 W | 600 w | 10 min | 20 min | 30 min | ||

| α-helix | 22.30 ± 0.51b | 23.80 ± 0.19a | 23.52 ± 0.12a | 21.94 ± 0.23b | 23.64 ± 0.08a | 23.52 ± 0.08a | 23.51 ± 0.11a |

| β-sheet | 31.66 ± 0.11a | 31.37 ± 0.10b | 31.94 ± 0.18ab | 32.06 ± 0.09b | 31.8*5 ± 0.11a | 31.94 ± 0.06a | 32.53 ± 0.08a |

| β-turn | 10.97 ± 0.13a | 11.07 ± 0.26a | 10.53 ± 0.15b | 10.80 ± 0.07ab | 10.69 ± 0.18b | 10.53 ± 0.01b | 10.74 ± 0.02b |

| random coil | 35.07 ± 0.26a | 33.76 ± 0.33b | 34.01 ± 0.27b | 35.20 ± 0.22 a | 33.82 ± 0.03b | 34.01 ± 0.11b | 33.22 ± 0.04c |

All the data are the mean ± SD of three replicates. Mean followed by different letters in the same column differs significantly (p < 0.05).

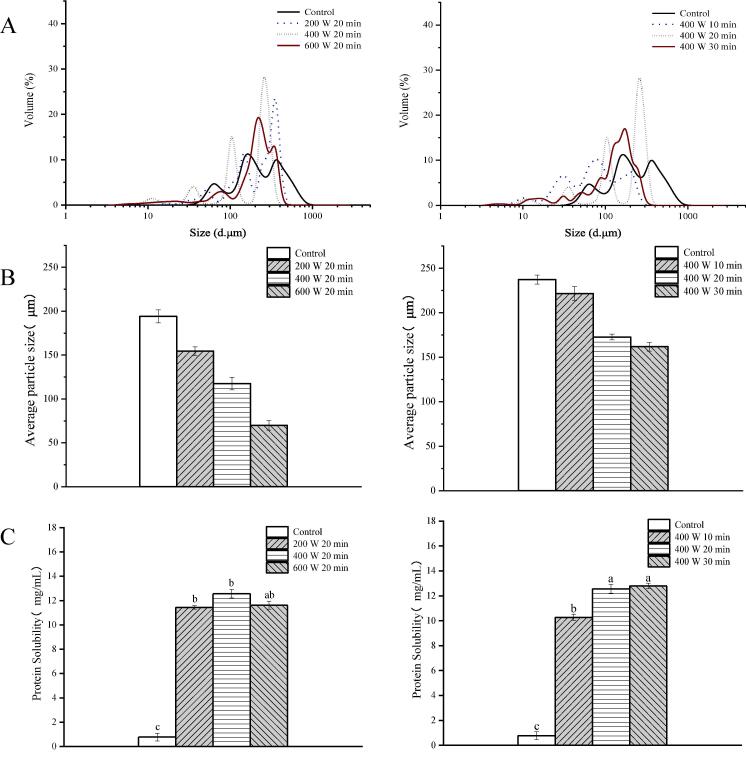

3.5. Particle size distribution

The particle size of a protein in a solution can affect its solubility, emulsification, and gelling properties [26]. Fig. 3A shows the particle size distribution of ultrasound-treated and untreated ISPP. Untreated ISPP exhibited a broad particle size distribution with three major peaks. The three peaks were separated more and slightly left-shifted after ultrasound treatments at 400 W for 10 min and 200 W for 20 min, indicating a decrease in the particle size of ISPP. The average particle size of ISPP became smaller and the peak value increased with increasing sonication power and time (from 200 to 400 W and 10 to 20 min). Ultrasound treatment significantly reduced the volume of the average particle size of ISPP by 8.72–54.03% (p < 0.05) compared to the untreated group (Fig. 3B). The reduction of the protein particles size was attributed to the aggregates unfolding and break-down by strong cavitation effect and high shear energy waves generated by the ultrasound [23]. However, a further increase of the ultrasound power to 600 W and treatment time to 30 min at 400 W slightly increased the particle size of ISPP. This observation was caused by the prolonged treatment, which increased the re-aggregation of protein particles by inducing the formation of other types of bonds [30]. From the result of free sulfhydryl groups content (Section 3.3), prolonged treatments could lead to the reduction of R–SH content, and this phenomenon might be resulted from the formation of disulfide bonds. Results of particle size agreed with studies on the effect of ultrasound treatment on soy proteins [31] and rapeseed proteins [32], which also showed the reduction of particle size.

Fig. 3.

Particle size distribution (A), average particle size (B) and protein solubility (C) of ISPP treated by HIU at different intensity and time. Different letters on the top of the column represent a significant difference (p < 0.05).

3.6. Protein solubility

The solubility of a protein affects its functional properties [23]. Fig. 3C shows the effect of ultrasound treatment on the solubility of ISPP. Ultrasound treatment at 400 W for 30 min enhanced the solubility of ISPP from 0.778 ± 0.311 mg/mL to 12.66 ± 0.412 mg/mL. Generally, the solubility of ISPP gradually increased (p < 0.05) with the enhancement of the processing power and the extension of the ultrasound time (Fig. 3C). HIU promoted the conformational changes in the protein structure, forming smaller aggregates of ISPP and exposing the hydrophilic regions to water, thus increasing the interaction area between the protein and water molecules [14]. This phenomenon changed the insoluble precipitates to soluble protein molecules. These results are consistent with those of a similar study by Deng et al. [10], in which an increase in the solubility of soy protein isolates after ultrasound treatment reduced the particle size, thus strengthening the protein-water interaction. However, ultrasound treatment at 600 W reduced the solubility of ISPP, possibly because of disulfide cross-linking and hydrophobic interactions, which led to the reformation of macromolecular aggregates causing the loss of protein solubility. Of note, the protein solubility results were in harmony with those of particle size and free sulfhydryl groups content. These results collectively suggest that ultrasound treatment affects the solubility of proteins by changing their structure, molecular size, and exposing their hydrophilic groups.

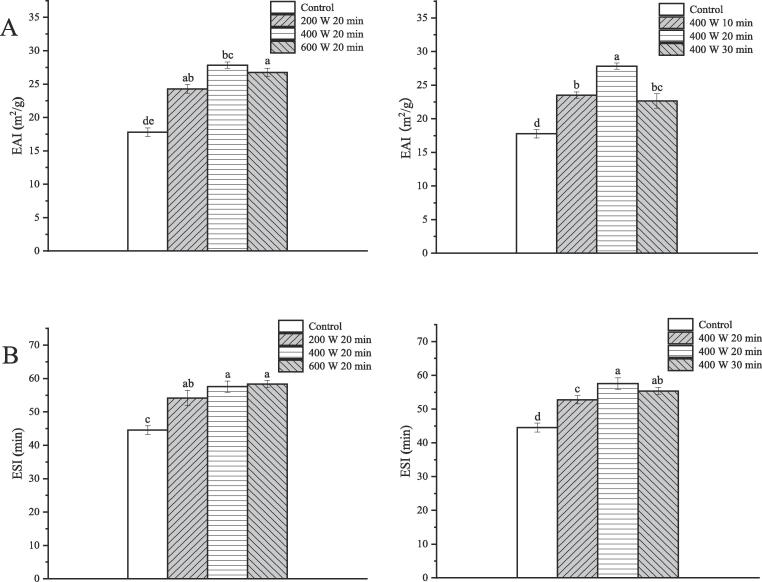

3.7. Emulsification properties

The emulsifying activity and emulsion stability indices were adopted to evaluate the emulsification properties of ISPP. As shown in Fig. 4, HIU processing had a positive effect on EAI and ESI (p < 0.05), indicating that sonication enhanced emulsion formation and stability of the ISPP. Notably, the emulsification properties of ISPP treated by HIU at 400 W for 20 min were the highest. In particular, the EAI and ESI increased to a maximum value of 27.83 m2/g and 57.58 min, respectively, for samples treated at 400 W for 20 min. The EAI of ultrasound-treated ISPP gradually increased with an increase in the ultrasound power from 100 to 400 W and ultrasound time from 10 to 20 min (p < 0.05). The enhancement of ESI of the ISPP was attributed to the formation of smaller droplets and changes in the surface chemistry of proteins induced by sonication. However, at higher treatment power (600 W) caused a slight decrease and no significant change (p > 0.05) in the EAI and ESI of the ISPP, respectively. In the same line, a longer treatment time (30 min) decreased EAI and ESI of the ISPP, possibly because of extensive proteins aggregation. The emulsification properties of proteins are positively correlated with their solubility, hydrophobicity, and conformational flexibility [33]. Of note, the results of emulsification properties of the ISPP agreed with those of ISPP solubility and H0.

Fig. 4.

Emulsifying activity index (EAI) (A) and emulsion stability index (ESI) (B) of ISPP treated by HIU at different intensity and time. Different letters on the top of the column represent a significant difference (p < 0.05).

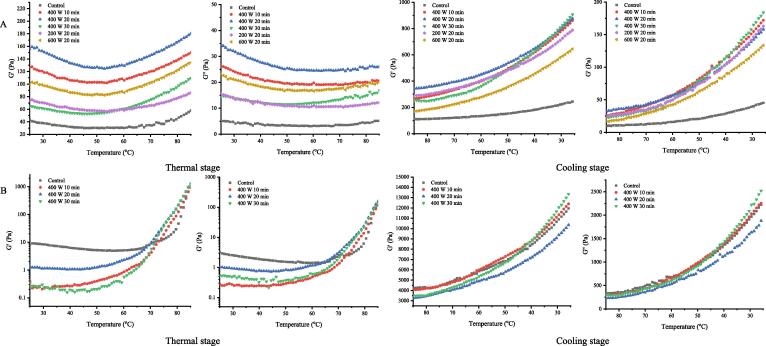

3.8. Rheological properties

Dynamic rheological measurements reflect the gelling ability of proteins [20]. Fig. 5A shows the storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G″) of the ISPP after ultrasonic treatment. The trend of G′ and G″ with temperature was similar in all the samples. All protein samples exhibited two regions during thermal processing: a slight decrease of G′ and G″ values between 25 and 50 °C, which is caused by an increase in the solution temperature. A second stage of increase in G′ and G″ values of all gel samples occurred when the temperature further increased from 50 to 85 °C resulted from the gelatinization at this period. This phenomenon might be due to the denaturation of protein and then hydrophobic groups exposed for gel formation [34]. During the thermal processing, the G′ of the ultrasound-treated ISPP samples is always higher than those of control. The temperature of minimum G′ was used to identify the start of protein gelatinization [35]. The ISPP treated with HIU at 200 and 400 W for 20 min exhibited a higher transition temperature, as 62.1 and 63.7, respectively, than others, which indicated that ultrasound treatment affected the reaction between water and proteins (ability of water-binding of proteins) [23].

Fig. 5.

Gelation storage modulus (G′) and frequency dependence of storage (G′) of ISPP and ISPP/EWP containing ISPP treated by HIU at different intensity and time.

During the cooling stage (from 85 to 25 °C), the G′ and G″ values of all samples kept increasing, resulting from the interaction of cross-link between proteins to establish a more stable gel network structure and the decrease in solution temperature [35]. Moreover, the G′ and G″ of the ISPP gradually increased with the enhancement of the ultrasonic processing power and time. The G′ values of all samples were higher than those of G″ at same temperature, suggesting that the gels have an elastic behavior rather than a viscous behavior [28], [35]. At the end of cooling stage, the G′end value of ISPP treated by HIU at 600 W for 20 min was the highest compared to others. In addition, the G′end value of ultrasound-treated ISPP was higher compared to untreated ISPP, indicating the HIU could effectively enhance the formation of ISPP gels [36]. Ultrasound treatment increases the elasticity of the sample gel, possibly because of the exposure of hydrophobic groups and free sulfhydryl groups, aiding in forming a more stable gel network structure [37]. The findings of this study were consistent with those of on pumpkin protein [38] and on soybean protein [39].

The impact of HIU on ISPP to form a hybrid gel was also analyzed in this study. The gel network formation of ISPP/EWP hybrid protein was studied using the dynamic oscillation test (temperature scanning). Fig. 5B shows the G′ and G″ of the ISPP/EWP hybrid gels. The G′ values of all mixture protein samples were higher than the G″ values, suggesting that the hybrid protein gels have an elastic behavior rather than a viscous behavior. The mixture protein with ultrasound treated ISPP showed similar trends of G′ and G″, where showed a slight decrease of G′ between 25 and 45 °C and further increase from 45 to 85 °C. The reason for the decline of G′ is same as G′ of ISPP, furthermore, EWP leads to a lower denaturation temperature of hybrid gels [17]. Compared with the control sample, the transition temperature of the hybrid gel system with ultrasound-treated ISPP is lower, indicating that HIU could lower the start temperature of hybrid protein gelatinization [40].

During the cooling stage (from 85 to 25 °C), the G′ and G″ values of all samples kept increasing, resulting from the interaction of cross-link between proteins to establish a more stable gel network structure [20]. The G′ and G″ curves of hybrid proteins containing ISPP after HIU treatment at 400 W for 10 and 30 min shared a close association with the control. Notably, the G′ and G″ of the hybrid protein with ISPP after HIU treatment at 400 W for 20 min were lower than others. At the end of cooling stage, the G′end value of hybrid protein containing ISPP after HIU treatment at 400 W for 30 min was the highest compared to others. Compared to the trend of G′ of ISPP gels only, the G′ of hybrid gel increased sharply with a higher G′end value indicating that EWP improved the hybrid gel strength.

3.9. Gelling properties

3.9.1. Texture profile analysis (TPA)

The strength and elasticity of the gel have an important influence on the tissue state and quality of the food. The results of the texture profile of gel samples indicated that ultrasonic treatment significantly improved the gel’s strength and elasticity of the ISPP (p < 0.05) (Table 2). The strength of the ISPP gels was increased and the elasticity of the ISPP gels first increased and then decreased with the extension of the ultrasonic treatment time and power. The reduction in particle size possibly led to a tighter and uniform network structure under thermal treatment, thus further enhanced the gel’s hardness and elasticity [20]. Interestingly, the texture profile results of the gel samples were consistent with those of protein solubility and particle size. The tertiary structural changes of ISPP attributed to HIU processing led to changes in the content of the free sulfhydryl group, which were converted into disulfide bonds under thermal treatment, thereby forming a denser protein gel network [41].

Table 2.

Texture properties of ISPP gels and ISPP/EWP hybrid gels containing ISPP with different ultrasonic treatments.

| Ultrasonic treatments |

gel strength (g) |

gel elasticity (%) |

gel strength (g) |

gel elasticity (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (min) | Power (W) | ICPP | ICPP | ICPP/EWP* | ICPP/EWP |

| 20 | 0 | 221.15 ± 12.47d | 77.52 ± 4.23c | ||

| 200 | 305.08 ± 20.34c | 84.51 ± 3.83b | |||

| 400 | 679.97 ± 31.7b | 93.11 ± 1.13a | |||

| 600 | 835.62 ± 21.76a | 80.05 ± 0.72bc | |||

| 0 | 400 | 221.15 ± 12.47d | 77.52 ± 4.23c | 882.54 ± 21.21d | 99.38 ± 0.2 cd |

| 10 | 415.75 ± 38.64c | 82.22 ± 2.98bc | 506.71 ± 22.31e | 99.01 ± 0.46 cd | |

| 20 | 679.97 ± 31.7b | 93.11 ± 1.13a | 597.07 ± 29.67f | 99.63 ± 0.04 cd | |

| 30 | 1047.86 ± 34.83a | 84.35 ± 3.70b | 871.93 ± 32.18d | 99.04 ± 0.49 cd | |

All the data are the mean ± SD of three replicates. Mean followed by different letters in the same column differs significantly (p < 0.05).

Notably, the gel strength of the ISPP/EWP hybrid gel decreased (p < 0.05), whereas its elasticity had no significant difference (p > 0.05) compared to the control hybrid gel sample. This phenomenon was attributed to the modification of the structural properties of ISPP, including particle size distribution, free sulfhydryl group content and surface hydrophobicity upon HIU treatment, which changed the interaction between two proteins.

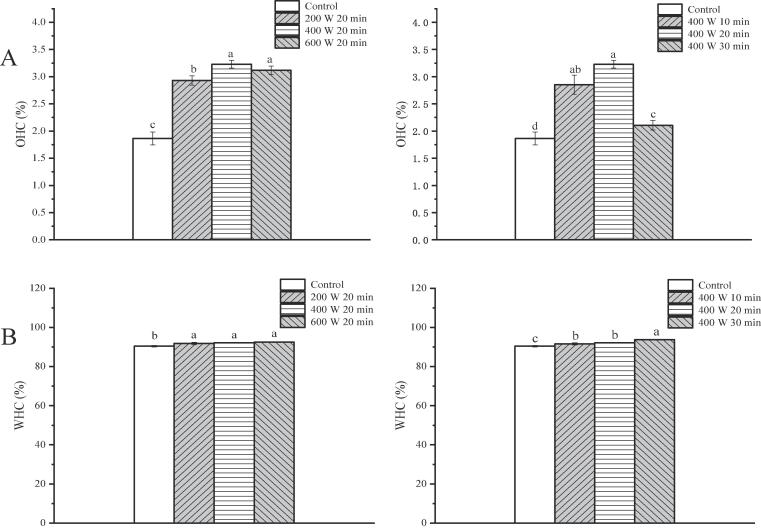

3.9.2. Water and oil holding capacities (WHC and OHC)

Oil absorption and water holding capacities of proteins are important in food technology. Fig. 6 shows the results of OHC and WHC of untreated and ultrasound-treated ISPP gels. The OHC of ultrasound-treated protein was increased (p < 0.05) from 1.86% to 3.23%, possibly because of larger ISPP aggregates broken down, which resulted in a larger specific surface area and exposure of the hydrophobic surface to the solvent [21], [25]. In addition, there was an increase in the content of the hydrophobic group in the ISPP, which provided interaction sites between proteins and lipids. However, there were no significant differences (p > 0.05) in the WHC of the ISPP between differentially HIU treated samples. Compared to the control, the water retention capacity slightly increased with an increase in the ultrasonic treatment intensity and time. A smaller particle size translates to smaller pores in the network, which is conducive to forming a denser and uniform network structure that locks in more water, thereby increasing the WHC of the gel [20]. A previous study reported that ultrasonic treatment enhanced the exposure of hydrophobic groups of the egg white protein and strengthened their interaction during heating, thereby improving the water retention of the hybrid gel [42].

Fig. 6.

Oil holding capacity (OHC) (A) and water holding capacity (WHC) (B) of ISPP treated by HIU at different intensity and time. Different letters on the top of the column represent a significant difference (p < 0.05).

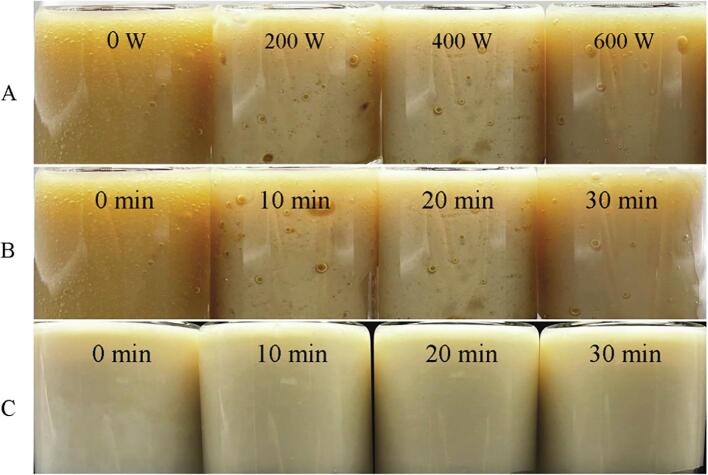

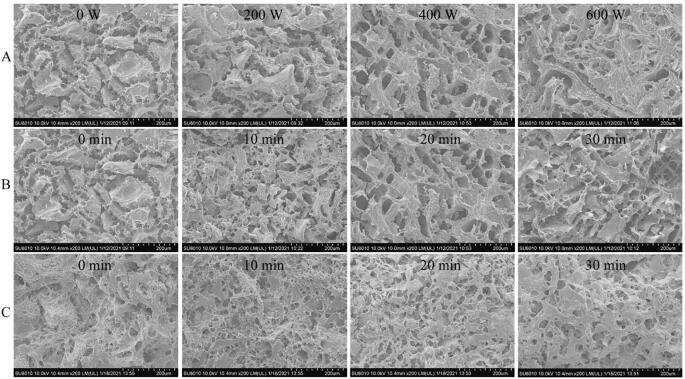

3.9.3. Microstructure analysis

Fig. 7, Fig. 8 show the photo and surface morphology of ISPP gels and ISPP/EWP hybrid gels prepared by ultrasonic treated and untreated ISPP, respectively. The ISPP gels are opaque, light yellow, rough, and have bubbles. In contrast, the ISPP/EWP hybrid gels are smoother and more uniform than the ISPP gels (Fig. 7). The surface morphology of the untreated ISPP had large holes and was uneven (Fig. 8). In contrast, the treated ISPP had denser and uniform pores on the surface, which became enhanced with the extension of the ultrasonic time and increase of the ultrasonic power. The differences in the microstructure between treated and untreated ISPP gels were primarily attributed to the increase in the content of hydrophobic and free sulfhydryl groups in the treated sample [39]. The increase promoted intermolecular interactions between the hydrophobic and free sulfhydryl groups, forming tighter and larger aggregates during heating.

Fig. 7.

Photos of ISPP gels and ISPP/EWP hybrid gels using untreated and ultrasonic treated ISPP. A: ISPP with ultrasonic treatment at different intensity for 20 min; B: ISPP with ultrasonic treatment at 400 W for different times; C: ISPP with ultrasonic treatment at 400 W for different times mixed with EWP at ratio of 1:1.

Fig. 8.

Scanning electron microscope images of ISPP gels and ISPP/EWP hybrid gels. A: ISPP with ultrasonic treatment at different intensity for 20 min; B: ISPP with ultrasonic treatment at 400 W for different times; C: ISPP with ultrasonic treatment at 400 W for different times mixed with EWP at ratio of 1:1.

The untreated ISPP/EWP hybrid gel had a loose structure, large pores, and uneven distribution. The uniformity of the ISPP/EWP hybrid gel first increased (from 10 to 20 min at 400 W) and then decreased, with the pores first becoming smaller and then larger as the ultrasonic time of ISPP increased.

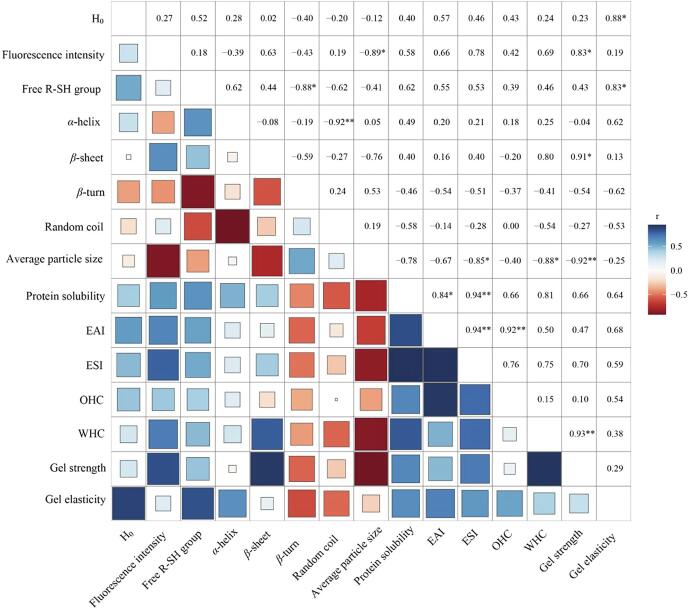

3.10. Correlation analysis

The correlation coefficient analysis was established to elucidate the relationship among the structural characteristics and functional properties. As shown in Fig. 9, H0 and free R–SH group content were positively correlated with gel elasticity (r = 0.88* and 0.83*, respectively). While the relative content of β-sheet was negatively correlated with gel elasticity (r = −0.62). There were highly negative correlations among tryptophan and tyrosine residues (fluorescence intensity), β-sheet and gel strength (r = 0.83* and 0.91*, respectively), which was consistent to the result of FTIR analysis and previous study about high content of β-sheet might lead to an improvement in gel characteristics [32]. Meanwhile, there was a positive correlation between gel strength and WHC, indicating ISPP gels with a high gel strength having a strong water retention capability. Fluorescence intensity and protein solubility were positively correlation to ESI and EAI (r = 0.75, 0.94**, respectively). The OHC of gels showed positive correlation with EAI (r = 0.92**), and WHC showed positive correlation with fluorescence intensity, β-sheet and protein solubility (r = 0.69, 0.8, and 0.81, respectively). Average particle size was negatively correlated with protein solubility, ESI, WHC and gel strength (r = −0.85*, −0.88*, and 0.92** respectively), which were widely reported [42]. There were highly negative correlations between β-turn and free R–SH group (r = −0.88*), random coil and α-helix (r = −0.92**), fluorescence intensity, β-sheet and average particle size (r = −0.89*, −0.76 respectively), random coil and protein solubility (r = −0.78).

Fig. 9.

Heat map based on properties of ISPP treated by HIU at different intensity and time. Blue indicates a high index value, and red indicates a low index value.

Under appropriate ultrasonic power and time, HIU treatment induces the unfolding and breakdown of macromolecular aggregates of ISPP resulting in the exposition of hydrophobic and R–SH groups, reduction in the particle size. Meanwhile, the decrease of relative content of β-turn indicated the partially unfolding of polypeptide chain, leading to the increase of free R–SH group. These active groups contributed to the formation of a dense and uniform gel network of ISPP and ISPP/EWP gel [41]. Furthermore, the increase of solubility and surface hydrophobicity and the decrease of particle size increasing ISPP’s EAI, ESI and OHC, correlating to the surface chemistry of protein droplet. Smaller aggregates of ISPP could expose more hydrophilic regions to water, thus increased the interaction area between the protein and water molecules, then increased the ESI, EAI and OHC [20].

4. Conclusion

HIU treatment changes the structure and improves the emulsification and gelation properties of insoluble potato proteins isolates. The cavitation and shearing caused by HIU treatment break down the large aggregations of protein, thus promoting the exposure of the hydrophobic groups on the molecule’s surface and alteration of the microenvironment of tryptophan and tyrosine residues. These modifications increase surface hydrophobicity, protein solubility, and a reduction in the particle size of ISPP, thus strengthening its emulsification property. Meanwhile, the exposition of hydrophobic and R–SH groups, reduction in the particle size contributed to the formation of a dense and uniform gel network of ISPP and ISPP/EWP hybrid gel. This study shows that high-intensity ultrasound can effectively improve the emulsification and gelling properties of insoluble potato proteins.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ruixuan Zhao: Methodology, Investigation, Software, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Xinshuo Liu: Methodology, Software, Investigation, Data curation. Wei Liu: Investigation, Software, Visualization. Qiannan Liu: Resources, Funding acquisition. Liang Zhang: Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. Honghai Hu: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program (CAAS-ASTIP-IFST-01); Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund (No. S2021JBKY-03); and the China Agriculture Research System of MOF and MARA (CARS-09-P27).

Contributor Information

Liang Zhang, Email: zhangliang19870314@163.com.

Honghai Hu, Email: huhonghai@caas.cn.

References

- 1.Hussain M., Qayum A., Xiuxiu Z., Liu L.u., Hussain K., Yue P., Yue S., Y.F Koko M., Hussain A., Li X. Potato protein: An emerging source of high quality and allergy free protein, and its possible future based products. Food Res. Int. 2021;148:110583. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2021.110583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mohamed A.A., Behiry S.I., Younes H.A., Ashmawy N.A., Salem M.Z.M., Márquez-Molina O., Barbabosa-Pilego A. Antibacterial activity of three essential oils and some monoterpenes against Ralstonia solanacearum phylotype II isolated from potato. Microb. Pathog. 2019;135:103604. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2019.103604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu W., Guan Y., Ji Y., Yang X. Effect of cutting styles on quality, antioxidant activity, membrane lipid peroxidation, and browning in fresh-cut potatoes. Food Biosci. 2021;44:101435. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aljuraiban G.S., Pertiwi K., Stamler J., Chan Q., Geleijnse J.M., Van Horn L., Daviglus M.L., Elliott P., Oude Griep L.M. Potato consumption, by preparation method and meal quality, with blood pressure and body mass index: The INTERMAP study. Clin. Nutr. 2020;39(10):3042–3048. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2020.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han K.-H., Kim S.-J., Shimada K.-I., Hashimoto N., Yamauchi H., Fukushima M. Purple potato flake reduces serum lipid profile in rats fed a cholesterol-rich diet. J. Funct. Foods. 2013;5(2):974–980. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pastuszewska B., Tuśnio A., Taciak M., Mazurczyk W. Variability in the composition of potato protein concentrate produced in different starch factories—A preliminary survey. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2009;154:260–264. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miedzianka J., Pęksa A., Pokora M., Rytel E., Tajner-Czopek A., Kita A. Improving the properties of fodder potato protein concentrate by enzymatic hydrolysis. Food Chem. 2014;159:512–518. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waglay A., Karboune S., Alli I. Potato protein isolates: Recovery and characterization of their properties. Food Chem. 2014;142:373–382. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zwijnenberg H.J., Kemperman A.J.B., Boerrigter M.E., Lotz M., Dijksterhuis J.F., Poulsen P.E., Koops G.-H. Native protein recovery from potato fruit juice by ultrafiltration. Desalination. 2002;144:331–334. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deng X., Ma Y., Lei Y., Zhu X., Zhang L., Hu L., Lu S., Guo X., Zhang J. Ultrasonic structural modification of myofibrillar proteins from Coregonus peled improves emulsification properties. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;76 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shkolnikov Lozober H., Okun Z., Shpigelman A. The impact of high-pressure homogenization on thermal gelation of Arthrospira platensis (Spirulina) protein concentrate. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2021;74 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang S., Sun L., Ju H., Bao Z., Zeng X.-A., Lin S. Research advances and application of pulsed electric field on proteins and peptides in food. Food Res. Int. 2021;139 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu Z., Zhu W., Yi J., Liu N., Cao Y., Lu J., Decker E.A., McClements D.J. Effects of sonication on the physicochemical and functional properties of walnut protein isolate. Food Res. Int. 2018;106:853–861. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lauterborn W., Mettin R. In: Power Ultrasonics. Gallego-Juárez J.A., Graff K.F., editors. Woodhead Publishing; Oxford: 2015. 3 - Acoustic cavitation: bubble dynamics in high-power ultrasonic fields; pp. 37–78. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang X., Chen X., Gong Y., Li Z., Guo Y., Yu D., Pan M. Emulsion gels stabilized by soybean protein isolate and pectin: Effects of high intensity ultrasound on the gel properties, stability and β-carotene digestive characteristics. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;79 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meng Y., Liang Z., Zhang C., Hao S., Han H., Du P., Li A., Shao H., Li C., Liu L. Ultrasonic modification of whey protein isolate: Implications for the structural and functional properties. LWT. 2021;152 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peng J., Zhu K.-X., Guo X.-N., Zhou H.-M. Egg white protein addition induces protein aggregation and fibrous structure formation of textured wheat gluten. Food Chem. 2022;371 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hussain M., Qayum A., Zhang X., Hao X., Liu L., Wang Y., Hussain K., Li X. Improvement in bioactive, functional, structural and digestibility of potato protein and its fraction patatin via ultra-sonication. LWT. 2021;148 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gülseren I., Güzey D., Bruce B.D., Weiss J. Structural and functional changes in ultrasonicated bovine serum albumin solutions. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2007;14:173–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen X., Zhao C., Guo M. Effects of high intensity ultrasound on acid-induced gelation properties of whey protein gel. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017;39:810–815. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang H., Chen G., Liu M., Mei X., Yu Q., Kan J. Effects of multi-frequency ultrasound on physicochemical properties, structural characteristics of gluten protein and the quality of noodle. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020;67 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Z., Chen X., Liu X., Liu W., Liu Q., Huang J., Zhang L., Hu H. Effect of salt ions on mixed gels of wheat gluten protein and potato isolate protein. LWT. 2022;154 [Google Scholar]

- 23.M. Soltani Firouz, 6 - Application of high-intensity ultrasound in food processing for improvement of food quality, in: F.J. Barba, G. Cravotto, F. Chemat, J.M.L. Rodriguez, P.E.S. Munekata (Eds.) Design and Optimization of Innovative Food Processing Techniques Assisted by Ultrasound, Academic Press, 2021, pp. 143-167.

- 24.Xiong T., Xiong W., Ge M., Xia J., Li B., Chen Y. Effect of high intensity ultrasound on structure and foaming properties of pea protein isolate. Food Res. Int. 2018;109:260–267. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang Z.H., Zhou H.M., Bai Y.P. Effects of vacuum ultrasonic treatment on the texture of vegetarian meatloaves made from textured wheat protein. Food Chem. 2021;361 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pezeshk S., Rezaei M., Hosseini H., Abdollahi M. Impact of pH-shift processing combined with ultrasonication on structural and functional properties of proteins isolated from rainbow trout by-products. Food Hydrocolloids. 2021;118:106768. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2021.106768. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amiri A., Sharifian P., Soltanizadeh N. Application of ultrasound treatment for improving the physicochemical, functional and rheological properties of myofibrillar proteins. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018;111:139–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.12.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xing T., Xu Y., Qi J., Xu X., Zhao X. Effect of high intensity ultrasound on the gelation properties of wooden breast meat with different NaCl contents. Food Chem. 2021;347 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu R., Zhao S.-M., Xie B.-J., Xiong S.-B. Contribution of protein conformation and intermolecular bonds to fish and pork gelation properties. Food Hydrocolloids. 2011;25:898–906. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koshani R., Jafari S.M. In: Nanoencapsulation of Food Ingredients by Specialized Equipment. Jafari S.M., editor. Academic Press; 2019. Chapter Eight - Production of food bioactive-loaded nanostructures by ultrasonication; pp. 391–448. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zou Y., Yang H., Li P.P., Zhang M.H., Zhang X.X., Xu W.M., Wang D.Y. Effect of different time of ultrasound treatment on physicochemical, thermal, and antioxidant properties of chicken plasma protein. Poult. Sci. 2019;98:1925–1933. doi: 10.3382/ps/pey502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li H., Hu Y., Zhao X., Wan W., Du X., Kong B., Xia X. Effects of different ultrasound powers on the structure and stability of protein from sea cucumber gonad. LWT. 2021;137 [Google Scholar]

- 33.S. Damodaran, K.L. Parkin, O.R. Fennema, Fennema's Food Chemistry.

- 34.Oliver G., Pritchard P.E. In: Food Colloids and Polymers. Dickinson E., Walstra P., editors. Woodhead Publishing; 2005. Rheology of the gel protein fraction of wheat flour; pp. 255–259. [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Vliet T. In: Hydrocolloids. Nishinari K., editor. Elsevier Science; Amsterdam: 2000. Structure and rheology of gels formed by aggregated protein particles; pp. 367–377. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller D.K., Acevedo N.C., Lonergan S.M., Sebranek J.G., Tarté R. Rheological characteristics of mechanically separated chicken and chicken breast trim myofibril solutions during thermal gelation. Food Chem. 2020;307 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vittayanont M., Vega-Warner V., Steffe J.F., Smith D.M. Heat-induced gelation of chicken pectoralis major myosin and β-lactoglobulin. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2001;49:1587–1594. doi: 10.1021/jf000774z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Du H., Zhang J., Wang S., Manyande A., Wang J. Effect of high-intensity ultrasonic treatment on the physicochemical, structural, rheological, behavioral, and foaming properties of pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata Duch.)-seed protein isolates. LWT. 2022;155 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin H.-F., Lu C.-P., Hsieh J.-F., Kuo M.-I. Effect of ultrasonic treatment on the rheological property and microstructure of tofu made from different soybean cultivars. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2016;37:98–105. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mason T.J., Chemat F., Ashokkumar M. In: Power Ultrasonics. Gallego-Juárez J.A., Graff K.F., editors. Woodhead Publishing; Oxford: 2015. 27 - Power ultrasonics for food processing; pp. 815–843. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xiong W., Wang Y., Zhang C., Wan J., Shah B.R., Pei Y., Zhou B., Li J., Li B. High intensity ultrasound modified ovalbumin: Structure, interface and gelation properties. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2016;31:302–309. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheng Y., Donkor P.O., Ren X., Wu J., Agyemang K., Ayim I., Ma H. Effect of ultrasound pretreatment with mono-frequency and simultaneous dual frequency on the mechanical properties and microstructure of whey protein emulsion gels. Food Hydrocolloids. 2019;89:434–442. [Google Scholar]