Abstract

Ensuring that racial and ethnic minority women are involved in breast cancer research is important to address well-documented current disparities in cancer incidence, stages of diagnosis, and mortality rates. This study used a novel interactive focus group method to identify innovative communication strategies for recruiting women from two minority groups—Latinas and Asian Americans—into the Komen Tissue Bank, a specific breast cancer biobank clinical trial. Through activities that employed visual interactive tools to facilitate group discussion and self-reflection, the authors examined perspectives and motivations for Asian American women (N = 17) and Latinas (N = 14) toward donating their healthy breast tissue. Findings included three themes that, while common to both groups, were unique in how they were expressed: lack of knowledge concerning breast cancer risks and participation in clinical research, cultural influences in BC risk thinking, and how altruism relates to perceived personal connection to breast cancer. More significantly, this study illuminated the importance of using innovative methods to encourage deeper, more enlightened participation among underrepresented populations that may not arise in a traditional focus group format. The findings from this study will inform future health communication efforts to recruit women from these groups into clinical research projects like the Komen Tissue Bank.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Asian American, Hispanic, Latina, Novel methods, Focus group

The Susan G. Komen Tissue Bank at the IU Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center (hereafter referred to as Komen Tissue Bank or KTB) is the only biobank in the world that collects healthy breast tissue to be used as normal controls in breast cancer (BC) research. Significant barriers exist to collecting tissue from a racially and ethnically diverse sample of the population, thus limiting appropriate representation of subpopulations like1Hispanic or Latina (H or L) [1], or Asian women in clinical trials (CTs). The purpose of this study is to employ novel, interactive methods to help illuminate communication approaches that might be more successful in recruiting H or Ls and/or Asian women to participate in CTs like the KTB.

Distinctions in biology and genetics impact the efficacy of treatment Kraschel and Roberts [2] and susceptibility to disease [3] of H or L and Asian women; however, through no fault of their own, encouraging these groups’ increased participation can present a challenge. Therefore, we employed novel methods to facilitate deep exploration of the perspectives of Asian and H or L women regarding donating healthy breast tissue to the Komen Tissue Bank, and specifically, to examine the effectiveness of potential KTB recruitment communication for women of these two minority groups.

Typically, focus groups today still use the traditional methods and remain consistent with the description delivered by Ref. [4]; who defined them as a form of qualitative research method in which an interviewer asks research participants specific questions about a topic or an issue in a group discussion. Consisting typically of 6–12 people, focus groups emphasize interaction among group members, encouraging the exchange of ideas and sharing of unique experiences and points of view [4]. However, it can be challenging for a focus group facilitator to inspire participants to involve themselves in an interactive, open discourse, therefore successfully avoiding a session consisting of participation only from the more confident and vocal in the group [5]. This can particularly occur when the cultural background of the group members may encourage reservation and caution, as is often the case with many Asian populations. In these cases, adopting novel methods and thinking “outside the box” could be very helpful [6]. Novel, interactive focus groups capitalize on otherwise less attainable group interaction [7], and can lead to a better understanding of attitudes, behaviors, and contexts from many points of view.

1. Asian and H or L participation in research and clinical trials

There has been extensive work examining why individuals from minoritized populations may be hesitant or unwilling to participate in CTs. For example, fear (of new treatments, expenses, adverse side effects, and decision-making, among others) is a known barrier to CT participation in Latinx communities [[8], [9], [10]]. Byrne et al. [10] also reported that lack of knowledge about research studies was more prevalent among H or Ls than other groups. H or Ls demonstrate noticeable tendencies toward altruism, equal to that of whites [9,11] suggesting that if this group had more information and received education and reassurance regarding their fears, their participation rates might increase. H or Ls tend to receive late-stage BC diagnoses, a phenomenon they share with Asian women [9]. Overall incidence of BC is lower in Asian countries than in the United States [12]; consequently, these women do not focus much attention on BC. Asian women have a general perception that their cancer risk is low in comparison to White women [13]; however, research shows BC risk measurably escalates when women emigrate from Asian countries to the United States [14,15], and Asian women in the United States are experiencing swiftly escalating BC incidence [16].

Until the Komen Tissue Bank was founded as a CT in 2007, there was no known repository in the world for normal breast tissue [17]. The KTB—still the only biobank of its kind in existence—collects, annotates, and stores healthy breast tissue and blood samples from women with no evidence of cancer and makes them available to researchers around the world to use as normal controls in BC research projects [18]. Ongoing efforts to recruit H or L and Asian women to the study have not resulted in adequate sample representation of these targeted groups. The current study employs novel communication approaches to help illuminate possibly effective outreach methods to encourage H or L and/or Asian women to participate in the KTB and similar CTs.

2. Methods

The research team, consisting of health communication, pharmaceutical, and medical scholars with high levels of expertise, collaborated with Research Jam, Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute's Patient Engagement Core, an interdisciplinary group of researchers with experience in patient engagement, human-centered design research, participatory design, and communication design. Research Jam assists individual investigators by engaging stakeholders in a human-centered design approach to data collection, analysis, synthesis, and solution development [[19], [20]].

2.1. Participants and recruitment

We recruited participants for this study through several channels, including: sending email invitations to social and business associates; posting fliers in the student center, labs, and research buildings of a large Midwestern university; reaching out to Asian and H or L affinity groups (groups of people connected through the same organization who are aligned through a similar interest or purpose; e.g., cultural, racial, or ethnic causes or heritage) at two large local companies to request assistance in recruiting their members; and sending participation invitation emails to the students and staff of a large Midwestern university who possessed an Asian or H or L surname. The recruitment email contained a simple explanation of the criteria for participation, the subject matter, and the date and location of the focus group meeting. Females 18 years of age or older who self-identified as Asian or H or L were eligible for the study. Participants were required to speak and understand English. A small number of participants (two in the Asian group and one in the H or L group) were previous donors but described themselves as having very little knowledge about the KTB itself. Although thousands of emails were distributed to university students and staff, the response rate was very low, resulting in the decision to hold only one session for each minority group. Prospective participants contacted the study team by email to express interest in participating or to ask more questions, which were answered in full.

Seventeen women (N = 17) ranging in age from 21 to 48 attended the Asian focus group session. They represented varied cultural, racial, and ethnic backgrounds (see Table 1). The thirteen women (N = 13) who attended the H or L session ranged in age from 25 to 58, and were of Mexican, Spanish, Puerto Rican, Colombian, or Salvadoran descent. Other demographic information including age, country of birth, marital status, and average number of children is depicted in Table 1. Most of the women had little to no knowledge of the KTB before participating in the session.

Table 1.

Participant demographics.

| HISPANICS/LATINAS (N = 13) | ASIAN AMERICANS (N = 17) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (mean, SD in years) | 38.4 (12.0) | 28.2 (7.3) |

| Ethnicity | Mexican- 8 (62%) | Chinese- 4 (24%) |

| Mexican/Spanish- 2 (15%) | Malaysian- 4 (24%) | |

| Puerto Rican- 1 (8%) | Japanese- 3 (18%) | |

| Colombian- 1 (8%) | Indian- 3 (18%) | |

| Salvadoran- 1 (8%) | Thai- 1 (6%) | |

| Korean- 1 (6%) | ||

| Indonesian- 1 (6%) | ||

| Birth Country | USA- 9 (69%) | USA- 4 (24%) |

| Mexico- 3 (23%) | China- 4 (24%) | |

| Puerto Rico- 1 (8%) | Malaysia- 4 (24%) | |

| India- 2 (12%) | ||

| Thailand- 1 (6%) | ||

| Indonesia- 1 (6%) | ||

| USSR- 1 (6%) | ||

| Marital Status | Single- 2 (15%) | Single- 10 (59%) |

| Married- 10 (77%) | Married- 6 (35%) | |

| Divorced- 1 (8%) | Divorced- 0% | |

| Prefer not to say- 0% | Prefer not to say- 1 (6%) | |

| Children (mean, SD) | 0.84 (1.14) | 0.18 (0.53) |

Note. For ease of understanding, all percentages have been rounded to the nearest whole number, creating a possibility of totals slightly higher than 100.

Each session lasted for two and a half hours, including a 30-min break for a catered lunch to prevent fatigue, as suggested by Tracy [21]. Sessions were audio-recorded, and one member of the study team took photographs during the session to document different activities. All study procedures were approved by the university's IRB before beginning the project. As participants arrived, a research team member gave them an informed consent document to read, which included a request to indicate their preference for how their photograph and recorded audio could be used (no restrictions, only if de-identified, or not at all). Participants were encouraged to ask questions after reading the informed consent document. After their questions were answered, the participants signed the form and were given a copy to keep.

2.2. Data collection

Research Jam assisted in the development of an interactive session based on participatory design methods. Participatory design is a practice that uses specially designed tools to enable non-designers (in this case, the participants) to share expertise and/or co-design solutions to a design challenge [22]. The session methodology encouraged participants to both “say,” meaning speak their thoughts, and “make,” meaning express their thoughts through creative activity. Deep thoughts and needs can be hard to understand and articulate. By incorporating both of these methods, we were better able to uncover what the participants could easily understand and articulate, as well as what was difficult for them to express [23]. First, the participants completed a demographic questionnaire asking about their race/ethnicity, place of birth, marital and parental status, and familiarity with the KTB. Next, the participants took part in four guided activities—labeled here as “tools”—specifically designed to allow for both verbal and written participation and they were sequenced to gradually work up to more demanding participation methods like group discussion. The tools used were called “Motivator Cards,” “Opinion Storyboards,” “Motivator Mad Libs,” and “People Cards.” More information about each of these activities follows.

2.2.1. Tool #1 – motivator cards

This activity served both as a warm-up and as a method for divulging potential motivations for participation in activities that, although unrelated to the study challenge, might also be motivations for donating breast tissue. Each participant introduced herself and shared something that she had felt motivated to do recently. For example, a participant may have felt motivated to finally clean the kitchen floor, or may have started to train for a marathon, or may have found the courage to ask a friend for a favor. Each participant was then asked why she felt motivated to do that activity, and all answers were written on a flip chart, and later copied onto index cards by a research team member.

2.2.2. Tool #2 – Opinion Storyboards

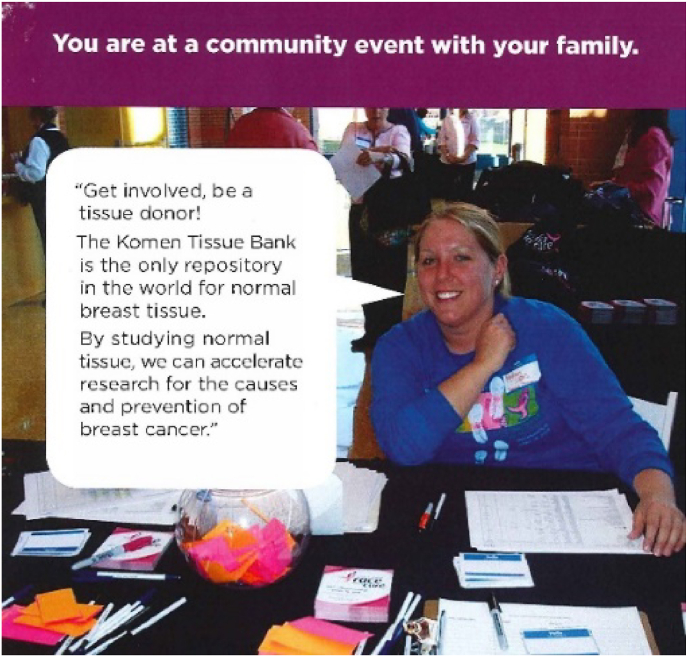

Storyboards are a long-standing method used in a diverse assortment of practices to facilitate the visual promotion of ideas [24]. Each participant was given a 15-page, 8 ½” X 11″ booklet-sized storyboard of the KTB breast tissue donation process, along with a red and a green pen. The storyboard contained pictures of people speaking to the reader through dialogue bubbles, as well as screenshots of different parts of the KTB brochure and some highlighted text choices from the website and printed materials. As an example, the first page contained a picture of a White woman sitting behind an information table, smiling, and saying, “Get involved, be a tissue donor! The Komen Tissue Bank is the only repository in the world for normal breast tissue. By studying normal tissue, we can accelerate research for the causes and prevention of breast cancer.” (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Sample Opinion Storyboard page.

We asked the participants to individually read the storyboard, to use the green pen to mark things they found to be positive and that encouraged them to consider donation, and to use the red pen for things that dissuaded them from donating. This allowed participants to learn more about the KTB at their own pace and reflect on the content independently before hearing the thoughts of others. Following their individual review of the storyboard booklet, the group was then led in a page-by-page discussion about the items they marked, identifying recruitment motivators and barriers. These additional motivators were also written on index cards and added to the motivator cards from the first exercise. The women were then given lunch.

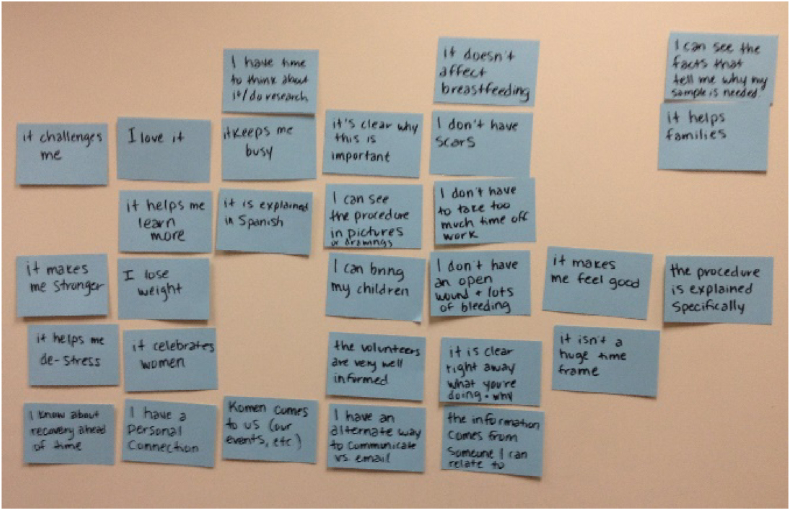

2.2.3. Tool #3 – Motivator Mad Libs

Following lunch, the women were introduced to the Motivator Mad Libs activity, a tool inspired by the popular game of Mad Libs®. The motivators and discussion topics that were captured on index cards in Tool #1 (Motivator Cards) and Tool #2 (Opinion Storyboards) had been taped to the wall (see Fig. 2). The participants were asked to work as a group to categorize all the motivator cards as either a potential motivator for donating breast tissue or not.

Fig. 2.

Motivator cards.

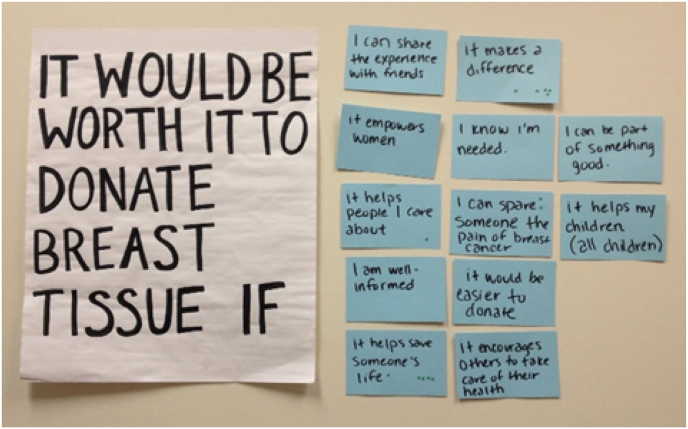

Meanwhile, a sentence that read, “It would be worth it to donate breast tissue if _______” was written on a large poster-sized sticky note and hung on the wall (see Fig. 3). Participants were then asked to choose the motivators they thought best completed the sentence. A research team member placed the “winning” cards on the wall next to the sentence. Next, each woman was given two round, green stickers and asked to “vote” for two of the winning motivators that she felt best completed the sentence for her personally, by placing a green sticker next to her top two choices. Peterson and Barron [5] posit that sticky notes and sticky dots should be staples in a qualitative researcher's toolkit because using them effectively reduces reluctance to engage and helps generate outcomes owned by the entire group. Through this method, the top motivators for breast tissue donation for each group were identified.

Fig. 3.

Motivator mad libs.

2.2.4. Tool #4 – People Cards

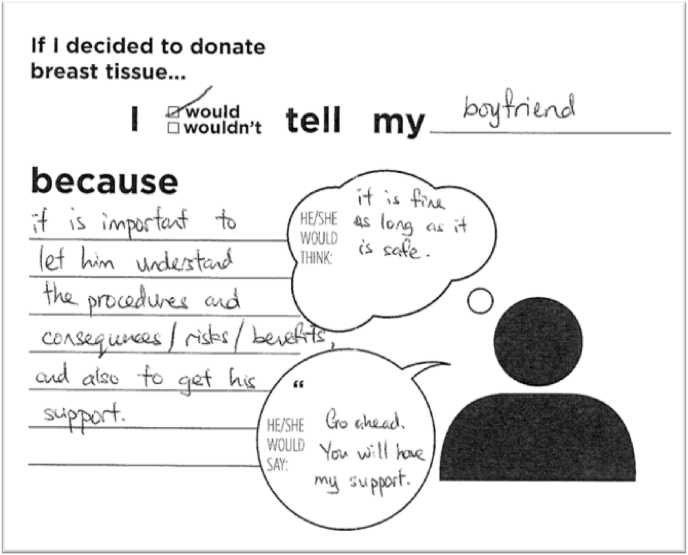

The final activity, the People Cards exercise, was designed by Research Jam and uses storytelling techniques to encourage writing based on the participants' own experiences. This tool incorporates concept generation for the purpose of understanding [22]. Each woman was given three “People Cards” and told to write the names of three people whose opinions they most valued on the blank line at the top of each card–one person per card. They were then told to unfold the card so that the hidden side was revealed. Once it was fully open, the People Card read, “If I decided to donate breast tissue … I (would) or (would not) tell my [person whose opinion was valued] because _________” (see Fig. 4). There were also two additional prompts the women were asked to complete. They read, “He/She would think _______,” and “He/She would say _______.” This activity was developed to better understand these specific populations’ potential normative and cultural influences affecting breast tissue donation. It helped further explore not only the participants' attitudes, but also the attitudes of their loved ones. Participants were then asked to share if they were comfortable doing so. Once all the People Cards were collected, the session concluded. The researcher thanked the participants, and all were given a $25 gift card and dismissed.

Fig. 4.

Sample people card.

2.3. Data analysis

The first, second, fifth, and eighth authors have noted expertise in designing and conducting focus groups. The first (representing the KTB) and fifth (representing Research Jam) authors were present at the focus groups. The remaining authors were able to access the transcriptions and recordings of the sessions. Coding and thematic analysis was performed separately by researchers representing the KTB and those representing Research Jam, using the methods described in the next paragraph.

The researchers collected, catalogued, and categorized all data from the written activities; the demographic questionnaires; the handwritten researcher notes; and the professional transcript of the session dialogue (see Table 2). All digital data was stored on a secure server and physical data generated during the sessions were kept in locked file cabinets. We derived findings by studying all data from verbal (both requested verbal activity participation and natural conversational discourse between activities) and written input, as well as the collected documents and images from the sessions. Using Excel, we sorted all of the data from the activities into separate spreadsheets and tables, labeled by the tool that had been used to gather the information. Each group (the KTB and Research Jam) submitted a report, and the full group of authors worked together to reach a consensus on themes and subthemes.

Table 2.

Explanation and illustrations of focus group activities.

| Name of Activity | Description of Activity | Data Emerging from Activity | What Did Data Look Like? | Example of Data Analysis | Main Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opinion Storyboards | Designated feelings and suggestions on pages showing KTB literature and situations | Desire for knowledge of everything to expect from pre-signup to recovery | Participants used green (good) and red (bad) pens to show feelings, and wrote comments to clarify. |  |

Participants want detailed knowledge of the science involved in donation. |

| Motivator Mad Libs | Answers entered into the sentence “It would be worth it to donate breast tissue if _____.” | Actual, comfortable dialogue; support of need for knowledge; selfish altruism | Motivators gleaned from dialogue were transferred to cards, then participants chose (as a group) which ones applied most here. |  |

Participants may be more willing to donate if they knew they could help their family or community. |

| People Cards | Outlining whom participants would/would not tell about donating, and why. | Lack of personal experience with breast cancer, least likely to talk to mothers about donating. | Participants completed individual cards with their choices of people and reasons. |  |

Participants show a marked lack of personal connection to breast cancer. |

| Discussion | Constant discussion throughout participation in the activities. | Lack of faith in donation being handled responsibly, lack of knowledge of breast cancer incidence, especially after migration to US. | Transcription of dialogue recorded throughout the session. |  |

Details and support for data derived from activities. Concern about pain from procedure not a priority. |

We applied thematic analysis to the data as described by Braun and Clarke [25] to identify distinctive categories and themes. This method of thematic analysis comprises of six steps. First, all of the data described above was read and re-read, and each piece of data or separate thought was systematically coded. Examples of codes included “want to help family,” and “cultural influences.” All codes were subsequently grouped into more general themes such as “altruism” and “cultural identity.” Data was continually reviewed, and all themes and codes were checked within the larger context of the data set to ensure that no meaning was lost and no false generalizations were made. We continually made changes to themes to make sure that they were specific and used precise language, and then included these themes in our final analysis [25].

3. Findings

The complex, resonant findings of this study are attributable to the novel data-gathering procedures used and revolve around three main themes: a need for knowledge about BC and the tissue donation process, the important role of cultural influences on tissue donation, and differences in altruistic outlook and perceived connection to BC. These themes are common to both minority groups but are observed and interpreted uniquely within the context of their racial/ethnic heritage.

3.1. Knowledge is essential to motivation

Despite the broad age range and particular races and ethnicities represented in both sessions, there was evidence of a universal need for highly detailed information among participants. The women's questions and comments covered a litany of topics, including general information about the procedure for donating breast tissue, explanation of medical terminology, and clarification of unfamiliar vocabulary (see Table 3). Participants from both groups had several questions about the science involved in the procedure and the reasoning behind collecting healthy breast tissue, though there were clear differences in the weight placed on certain topics.

Table 3.

Hispanic/Latina and Asian Americans’ need for detailed knowledge about the tissue donation process.

| HISPANICS/LATINAS |

ASIAN AMERICANS |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CODE | RESPONSES | QUOTE(S) | CODE | RESPONSES | QUOTE(S) |

| Education about recovery or post-op | 5 (38%) | “Am I going to be able to exercise? Am I going to be able to lift my child … recovery time and symptoms are missing and they're important.” “I wanted to know more if there are any complications like risk of infection.” |

Education about consent process | 4 (24%) | “So there's not a consent that has all this info, these risks, these potential risks and stuff?” “… want to know as much information as possible, even beyond what the informed consent.” |

| Education about effect on breast-feeding | 2 (15%) | “After you do this, can you continue to breastfeed or does it affect – I was going to ask, does this affect my milk supply? Milk ducts? Anything going on because I'm going to breastfeed my future kids.” | Education about cosmetic effect | 4 (24%) | “… is it going to disfigure my breast? Is it going to leave me lopsided?” “… putting into perspective how much of tissue you actually have and how much is actually taken.” |

3.2. The role of cultural influences

The women in both groups expressed their questions and concerns about breast tissue donation through the lenses of their respective cultural influences (see Table 4). Among these concerns were fear of stigma for breaking Asian cultural norms, the ability to participate in H or L cultural norms such as breastfeeding post-donation, and both groups’ varying beliefs about altruism. As before, though both groups were influenced by cultural factors, the manifestation of these factors differed greatly.

Table 4.

Hispanic and Asian Americans’ cultural perspectives on tissue donation.

| HISPANICS/LATINAS |

ASIAN AMERICANS |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CODE | RESPONSES | QUOTE(S) | CODE | RESPONSES | QUOTE(S) |

| Cultural norms | 7 (54%) | “… it is about community, it is about family.” “… motivated by doing some craft things like little cards for my family in Mexico.” “Latinas are more wanting to think in terms of family.” |

Distrust or lack of familiarity | 6 (35%) | “There's a lot of like religious, but also cultural stigmas to giving something of your body for research.” “I think in the US it's very common to have blood drives and like tissue drives and more common than other countries, but I mean my family in Japan have no idea what I mean.” “And then there's like the black market of trading blood and tissues and some people like, those poor people, leaving the wage to actually do that for a living. So although they call it donation on the surface, but you know, it's just a cover up for their trading." |

| Seeing own people or hearing own language |

7 (54%) |

“I would put a Hispanic or an Asian woman here so they could identify with them." “I imagine you're translating this into Spanish, right?” “It'll get grandma or my mom to do it if this in Spanish.” |

|||

| HISPANICS/LATINAS | ASIAN AMERICANS | ||||

| CODE |

RESPONSES |

QUOTE(S) |

CODE |

RESPONSES |

QUOTE(S) |

| Race and ethnicity are important | 5 (38%) | “The only piece that is missing for me is, if you're targeting specifically Latinas and Asians include it … just say, get involved, we need women like you. So that would make me feel needed.” | Cultural norms | 6 (35%) | “When I told my mother that I donated breast tissue and she's like why? Why would you do this? You know, why would you put yourself through that?” |

| Do something good | 8 (62%) | “We need to be kind to each other, and for that reason I would do it” “This is something I could do also to help and it doesn't cost me anything.” “The fact that you feel that you are part of something positive, something good is important to me.” |

Helping family or friends | 3 (18%) | “I have a personal connection that would be the highest rank for me.” “My family or really close friends, if it helps them then yeah I'll consider it." |

Some H or L participants continually referenced culturally strong bonds with family, and even mentioned that they like to “stick together,” “keep to themselves,” and “not get involved” in outside interests. Another H or L participant spoke of her family's collective resistance to mammograms. They considered their breasts to be “personal and delicate,” and they were fearful about exposing them to harm. How hard would it be to push against these cultural norms and do something their families resist?

These sentiments were echoed in the Asian group. One participant, a young Japanese woman, believed that, while she would be willing to donate her tissue, she would struggle to go through with it because her grandmother who lives in Japan would be markedly upset. Women in the Asian group also spoke of the stigma attached to going against the grain of what was considered acceptable behavior.

3.3. Contrast in perceived breast cancer connection

On the surface, the data reviewed in this theme points to how the impact of others affects participants’ perspectives toward breast tissue donation (see Table 5). H or L and Asian women perceived different connections to breast cancer, which in turn influenced their potential motivations for tissue donation. Here again, the unique methodology applied in this study yielded data that was both broad and deep, and allowed for more comprehensive consideration about possible implications for targeted recruitment. In the People Cards activity, several H or L participants shared that they had family members who had developed BC, and that they wanted to be good role models for their children. Facilitating groups of family members to interact with each other on this topic might encourage a more accepting view of healthy breast tissue donation. A different approach may be advisable for the Asian group, who did not disclose that they knew anyone with a history of breast cancer and were surprised by the statistics around increased risk of BC for Asian women the longer they lived in the United States. During the Motivator Mad Libs activity, they indicated by vote that they might be more likely to donate if they “had a personal connection.”

Table 5.

Hispanic and Asian Americans’ perceived connections to BC.

| HISPANICS/LATINAS |

ASIAN AMERICANS |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CODE | RESPONSES | QUOTE(S) | CODE | RESPONSES | QUOTE(S) |

| Personal connection | 6 (46%) | “You never know when [BC] is going to affect you, but at some point, it will.” “Breast cancer can hit me at any time.” “A month later her mom was diagnosed with breast cancer. Two weeks after that, her aunt was diagnosed with breast cancer.” “My sister died of breast cancer young …” “His mother was affected by breast cancer.” |

Personal connection | 2 (24%) | “Asian families usually do not have a close relative going through the problems associated with breast cancer, so we don't really get to see the pain involved.” |

Several times during the session, the H or Ls expressed that it is important to be kind and to help others. They considered it important to teach their children this outlook as well. On the other hand, although they chose “it helps women all over the world” as one of their top-voted Motivator cards, the Asian session members expressed comparatively lower levels of altruism toward strangers or the broader community.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was twofold: to examine perspectives of H or Ls and Asian women regarding donation of healthy breast tissue for BC research, and to explore the use of novel research methods to improve the depth of the resulting data, with the goal of improving the effectiveness of communication with and recruitment of these groups.

It is important to discuss these groups’ sizes and their potential impact on the findings. Some researchers have found that smaller focus group sizes are desirable. For example [26], suggest groups of five-eight participants for sensitive or personal topics, and groups of 9–12 members when working with consumer topics. However, these authors also preface these guidelines by stating “the most workable size depends on the background of the participants, the complexity of the topic, and the expertise of the moderator” [26]; p. 510). While the focus group sizes in the current study are larger than is sometimes recommended, we noticed no adverse repercussions on their ability to participate. In fact, the larger group sizes may even have participated to a feeling of belonging in all the group members, and encouraged them to speak up and better share their thoughts and ideas. Women in both groups expressed their enjoyment in having been part of the experience, and appreciation at having been heard.

While there were some similarities across the two racial/ethnic groups included in this study, key differences were also found. Overall, while findings did show evidence of the potential for successful recruitment of Asian women to the KTB study, the path is currently blocked by misperceptions and insufficient knowledge. Ironically, having knowledge is something this group prioritizes. The H or L participants, however, though they clearly also retain hesitations and concerns about healthy tissue donation, display evidence that the cultural barriers blocking them from KTB participation are perhaps more surmountable than those of the Asian group. Implications of these findings are more fully discussed in the following paragraphs.

4.1. What knowledge is needed?

Both the Asian and the H or L group members displayed a clear desire for knowledge about all aspects of health-related topics, indicating that informed consent focused on the purpose for CT research is a particularly important aspect to consider for recruiting women from these groups. Members of the Asian group universally agreed that all available information about breast tissue donation was necessary and helpful. Yet, it became apparent during discussion that the Asian women were seemingly unaware that their BC risk rate is sharply rising while those of other groups fall, and that after a prolonged stay in the United States, their risk rate rivals that of White women [27]. Asian women's clear cultural differences further contribute to their knowledge gap. The main focus of the H or L group regarding their need for knowledge revolved around general information. The use of Opinion Storyboards allowed H or Ls to note their lack of representation in KTB recruitment materials and to verbalize other details (such as a desire for Spanish-language text) that could have been overlooked without this novel visual activity. Comparable to the Asian group, the H or L women were not aware of how BC affects them, or how their ethnicity could affect their BC risk rate. It was clear with both groups that more detailed information from the KTB was essential.

4.2. The importance of altruism

The presence of altruism is perhaps the most important characteristic of cultural heritage to consider when recruiting women to the KTB study, or to any other CT involving little-to-no immediate personal gain to the participant. Possessing altruistic tendencies can be especially valuable when the participant knows no one who is sick but donates simply to help others. As found in this study, and as has been well-documented in other work [28,29], H or Ls have a deep-rooted sense of altruism generally, and the current study group members were well aware of their personal connections to BC. This was particularly evident in the People Cards activity wherein participants frequently noted that they would share their KTB participation with people in their lives who knew someone affected by breast cancer. Research shows that as the BC incidence in Asian women is steadily rising, these women are quite likely to have personal connections to BC [27]. However, they may not know about these connections, and likely will not learn about them until the cultural barriers of personal privacy and stigma are penetrated [12,30]. This was clear throughout all the interactive study methods as well as in the dialogue transcription.

4.3. Novel methodology equals better focus groups

An important secondary “finding” of this study is that the use of a novel focus group methodology resulted in rich data and strong participation by all members of each session, as evidenced in the aforementioned examples. Novelty is not necessarily restricted to new methods but can also signify adjustments or improvements to tested research methods and creating new ways of doing things that are grounded in the pursuit of improving a feature of the research process [[6], [31]]. For example, a novel research environment could help put individuals at ease who suffer from introversion, lack of confidence, or other limiting concerns [32]. Additionally, applications of novel focus group methodologies such as holding sessions online [32,33] or using journaling and photo-elicitation [34] have been used to successfully elicit richer, more complete data. Although some of the individual activities (e.g., sticky notes) have certainly been previously adopted in focus group research [5], the current study's primary reliance on the combination of activities as communication tools for the entire session validates its claim to novelty.

In addition to providing rich data, this novel interactive design addresses many of the hesitations and limitations scholars have shared about traditional focus groups. By beginning the focus group session with pre-determined interview questions, as commonly done in standard focus groups, participants are denied an icebreaker or warmup, and therefore are not afforded the time or opportunity to find unifying ground with each other [35]. The current study shows that these concerns can be minimized with the use of a participatory session. The interactive nature of this novel methodology provided participants the opportunity to find similarities beyond those that made them eligible for the study (their gender and race) as soon as the session began. During the icebreaker, participants met others and shared experiences and commonalities before addressing the more sensitive topic of breast tissue donation [36], providing an opportunity for bonding that allowed for more open, honest discussions of individuals’ attitudes.

Often, when employing traditional focus group methods, participants may perceive that their contributions are not meaningful, and therefore demonstrate hesitation to voice their thoughts and opinions [37]. Although our participants voluntarily joined this study, some may naturally be more soft-spoken or shy. The individual writing activities allowed more reticent group members to still contribute and gave participants an opportunity to reflect upon their thoughts before speaking them aloud. This study's novel, participatory methodology allowed for questions and topics to arise that may not have originally been discussed or included in a pre-established interview guide by the researcher.

4.4. Limitations

It is a limitation of this study that, while the participants represent a mathematically wide range (based on the sample size) of Asian and H or L subgroups, this work does not contain a large representation of every subculture of these groups. Also, for purposes of increasing the number of older and younger generation members, as well as for strengthening the numbers of the different cultural groups, holding additional sessions would be beneficial.

5. Conclusions

Fox et al. posited that “[q]ualitative researchers who use novel methodological approaches should be prepared to engage in a process of reflection and reflexivity” so that the experience is transparent, and the method is shown to be sound (2007, p. 539). In this case, a unique method was created for us to engage with women who are not often included in either social scientific or BC research. Through the incorporation of novel, human-centered design methods and a mixed theoretical approach, we found that interactive, participatory focus groups are an important improvement upon the traditional focus group, and we hope others working with underserved groups consider these tactics.

Understanding how H or Ls and Asian women feel about tissue donation and how to encourage the behavior is important because their participation in medical research of this kind will lead to increased knowledge about why they get BC the way they do. It is important to note that the intent of this work is not necessarily to identify generalizable findings, but rather to gain insights to better engage with these populations, as well as to consider using these tools as the needs/resources allow for continued engagement and/or participation. The novel methodology used in this study could prove to be a means of eliciting further information about motivations not only for these group members’ participation in tissue donation, but also in other types of preventive and clinical BC research.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The preparation of this article was supported in part by Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences, Institute (UL1TR002529 from the National Institutes of Health). The authors wish to acknowledge the additional members of Research Jam—Dustin Lynch and Helen Sanematsu—as well as Elaine Cuevas of PResNet for their individual contributions to this work.

Biography

Katherine E. Ridley-Merriweather is the corresponding author for this manuscript. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to her. This project was funded, in part, with support from the Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences, Institute (UL1TR002529 from the National Institutes of Health). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

A 2018 survey by the Pew Research Center revealed that 54% of Hispanics have no preference between “Hispanic” and “Latino.” In consideration of this information, and in an effort to be as inclusive as possible, all uses of either “Hispanic” or “Latina” will read “Hispanic or Latina,” abbreviated “H or L.”

Contributor Information

Katherine E. Ridley-Merriweather, Email: keridley@iupui.edu.

Katharine J. Head, Email: headkj@iupui.edu.

Stephanie M. Younker, Email: steyounk@iu.edu.

Madeline D. Evans, Email: madgibs@iu.edu.

Courtney M. Moore, Email: crtnymre@iu.edu.

Deidre S. Lindsey, Email: dlindsey@horizonpharma.com.

Cynthia Y. Wu, Email: cywu@iu.edu.

Sarah E. Wiehe, Email: swiehe@iu.edu.

References

- 1.Pew Research Center Final topline - latinos concerned about place in America under trump. 2018. https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2018/10/Pew-Research-Center_Latinos-Concerned-About-Place-in-America-Under-Trump-TOPLINE_2018-10-25.pdf

- 2.Kraschel K.L., Roberts W.J. Reflecting America’s patient population—the need for diversity in clinical trials. AHLA Connect. 2014:28–32. [Google Scholar]

- 3.James R.D., Yu J.-H., Henrikson N.B., Bowen D.J., Fullerton S.M. Strategies and stakeholders: minority recruitment in cancer genetics research. Publ. Health Genom. 2008;11(4):241–249. doi: 10.1159/000116878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong L.P. Focus group discussion: a tool for health and medical research. Singap. Med. J. 2008;49(3):256–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peterson E.R., Barron K.A. How to get focus groups talking: new ideas that will stick. Int. J. Qual. Methods. 2007;6(3):140–144. doi: 10.1177/160940690700600303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fields Z. Innovative research methodology. In market research methodologies: multi-method and qualitative approaches. IGI Global. 2015:58–70. doi: 10.4018/978-1-4666-6371-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brotherson M.J. Interactive focus group interviewing: a qualitative research method in early intervention. Top. Early Child. Spec. Educ. 1994;14(1):101–118. doi: 10.1177/027112149401400110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quinn G.P., McIntyre J., Gonzalez L.E., Antonia T.M., Antolino P., Wells K.J. Improving awareness of cancer clinical trials among Hispanic patients and families: audience segmentation decisions for a media intervention. J. Health Commun. 2013;18(9):1131–1147. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2013.768723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernard-Davila B., Aycinena A.C., Richardson J., Gaffney A.O., Koch P., Contento I., Greenlee H. Barriers and Facilitators to Recruitment to a culturally based dietary intervention among urban hispanic breast cancer survivors. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities. 2015;2(2):244–255. doi: 10.1007/s40615-014-0076-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Byrne M.M., Tannenbaum S.L., Glück S., Hurley J., Antoni M. Participation in cancer clinical trials: why are patients not participating? Med. Decis. Making. 2014;34(1):116–126. doi: 10.1177/0272989X13497264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.London L., Hurtado-de-Mendoza A., Song M., Nagirimadugu A., Luta G., Sheppard V.B. Motivators and barriers to Latinas' participation in clinical trials: the role of contextual factors. Contemp. Clin. Trials. 2015;40:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2014.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Cancer Society Cancer facts & figures. American cancer society. 2020. https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/cancer-facts-figures-2020.html [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Nguyen G.T., Shungu N.P., Niederdeppe J., Barg F.K., Holmes J.H., Armstrong K., Hornik R.C. Cancer-related information seeking and scanning behavior of older Vietnamese immigrants. J. Health Commun. 2010;15(7):754–768. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.514034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu T.-Y., Bancorft J., Guthrie B. An integrative review on breast cancer screening practice and correlates among Chinese, Korean, Filipino, and Asian Indian American women. Health Care Women Int. 2005;26(3):225–246. doi: 10.1080/07399330590917780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yip C.H. Humana Press; 2009. Breast Cancer in Asia. Cancer Epidemiology; pp. 51–64. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu A.H., Mimi C.Y., Tseng C.-C., Stanczyk F.Z., Pike M.C. Dietary patterns and breast cancer risk in Asian American women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009;89(4):1145–1154. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sherman M.E., Figueroa J.D., Henry J.E., Clare S.E., Rufenbarger C., Storniolo A.M. The susan G. Komen for the cure Tissue Bank at the IU Simon cancer center: a unique resource for defining the “molecular histology” of the breast. Cancer Prev. Res. 2012;5(4):528–535. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Komen Tissue Bank Susan G. Komen® Tissue Bank at the IU Simon cancer center. 2020. http://komentissuebank.iu.edu/

- 19.Moore C.M., Wiehe S.E., Lynch D.O., Claxton G.E., Landman M.P., Carroll A.E., Musey P.I. Methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus eradication and decolonization in children study (part 1): development of a decolonization toolkit with patient and parent advisors. J. Participat. Med. 2020;12(2):e14974. doi: 10.2196/14974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mueller E.L., Cochrane A.R., Moore C.M., Jenkins K.B., Bauer N.S, Wiehe S.E. Assessing needs and experiences of preparing for medical emergencies among children with cancer and their caregivers. J. Pediatr. Hematol./Oncol. 2020;42(8):e723–e729. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000001826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tracy S.J. John Wiley & Sons; 2012. Qualitative Research Methods: Collecting Evidence, Crafting Analysis, Communicating Impact. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanders E.B.-N., Brandt E., Binder T. Paper Presented at the Proceedings of the 11th Biennial Participatory Design Conference. 2010. A framework for organizing the tools and techniques of participatory design. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanders E.B.-N. Helsinki University of Art and Design; 1999. Postdesign and Participatory Culture. Proceedings of Useful and Critical: the Position of Research in Design. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watson A.D. Design thinking for life. Art Educ. 2015;68(3):12–18. doi: 10.1080/00043125.2015.11519317. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krueger R.A., Casey M.A. In: Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation. Newcomer K.E., Hatry H.P., Wholey J.S., editors. vol. 3. Wiley & Sons; 2015. Focus group interviewing; pp. 378–403. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gomez S.L., Von Behren J., McKinley M., Clarke C.A., Shariff-Marco S., Cheng I., Glaser S.L. Breast cancer in Asian Americans in California, 1988–2013: increasing incidence trends and recent data on breast cancer subtypes. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2017:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4229-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.George S., Duran N., Norris K. A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to minority research participation among African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders. Am. J. Publ. Health. 2014;104(2):e16–e31. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.López-Anuarbe M., Cruz-Saco M.A., Park Y. More than altruism: cultural norms and remittances among Hispanics in the USA. J. Int. Migrat. Integrat. 2016;17(2):539–567. doi: 10.1007/s12134-015-0423-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Im E.O., Yi J.S., Kim H., Chee W. A technology-based information and coaching/support program and self-efficacy of Asian American breast cancer survivors. Res. Nurs. Health. 2020:37–46. doi: 10.1002/nur.22059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor C., Coffey A. Cardiff University; 2008. Innovation in qualitative research methods: possibilities and challenges.http://orca.cf.ac.uk/78184/1/wp121.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fox F.E., Morris M., Rumsey N. oing synchronous online focus groups with young people: methodological reflections. Qual. Health Res. 2007;17(4):539–547. doi: 10.1177/1049732306298754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trell E.-M., Van Hoven B. Making sense of place: exploring creative and (inter) active research methods with young people. Fennia Int. J. Geogr. 2010;188(1):91–104. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Creswell J.W. SAGE Publications; Los Angeles: 2013. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design : Choosing Among Five Approaches. c2013. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mu B., Navarrete A., Alaraj J. 2016 3rd International Conference on Education, Language, Art and Inter-cultural Communication (ICELAIC 2016) Atlantis Press; 2016, December. How to use artistic strategies to attenuate cultural conflicts and communication barriers taking” A cup of stories” project as an example. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cross R., Warwick-Booth L. Using storyboards in participatory research. Nurse Res. 2016;23(3):8–12. doi: 10.7748/nr.23.3.8.s3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodriguez K.L., Schwartz J.L., Lahman M.K., Geist M.R. Culturally responsive focus groups: reframing the research experience to focus on participants. Int. J. Qual. Methods. 2011;10(4):400–417. doi: 10.1177/160940691101000407. [DOI] [Google Scholar]