Abstract

Congenital Heart Disease (CHD), malformations of the heart present at birth, is the most common class of life-threatening birth defect (Hoffman (1995) [1], Gelb (2004) [2], Gelb (2014) [3]). A major research challenge is to elucidate the genetic determinants of CHD and mechanistically link CHD ontogeny to a molecular understanding of heart development. Although the embryonic origins of CHD are unclear in most cases, dysregulation of cardiovascular lineage specification, patterning, proliferation, migration or differentiation have been described (Olson (2004) [4], Olson (2006) [5], Srivastava (2006) [6], Dunwoodie (2007) [7], Bruneau (2008) [8]).Cardiac differentiation is the process whereby cells become progressively more dedicated in a trajectory through the cardiac lineage towards mature cardiomyocytes. Defects in cardiac differentiation have been linked to CHD, although how the complex control of cardiac differentiation prevents CHD is just beginning to be understood. The stages of cardiac differentiation are highly stereotyped and have been well-characterized (Kattman et al. (2011) [9], Wamstad et al. (2012) [10], Luna-Zurita et al. (2016) [11], Loh et al. (2016) [12], DeLaughter et al. (2016) [13]); however, the developmental and molecular mechanisms that promote or delay the transition of a cell through these stages have not been as deeply investigated. Tight temporal control of progenitor differentiation is critically important for normal organ size, spatial organization, and cellular physiology and homeostasis of all organ systems (Raff et al. (1985) [14], Amthor et al. (1998) [15], Kopan et al. (2014) [16]). This review will focus on the action of signaling pathways in the control of cardiomyocyte differentiation timing. Numerous signaling pathways, including the Wnt, Fibroblast Growth Factor, Hedgehog, Bone Morphogenetic Protein, Insulin-like Growth Factor, Thyroid Hormone and Hippo pathways, have all been implicated in promoting or inhibiting transitions along the cardiac differentiation trajectory. Gaining a deeper understanding of the mechanisms controlling cardiac differentiation timing promises to yield insights into the etiology of CHD and to inform approaches to restore function to damaged hearts.

Keywords: Cardiomyocyte, Differentiation, Cardiac progenitor, Cardiac regeneration, Developmental timing, Signaling, Wnt, Hedgehog, Fibroblast growth factor, Bone morphogenic protein, Insulin-like growth factor, Thyroid hormone, Hippo

1. Introduction

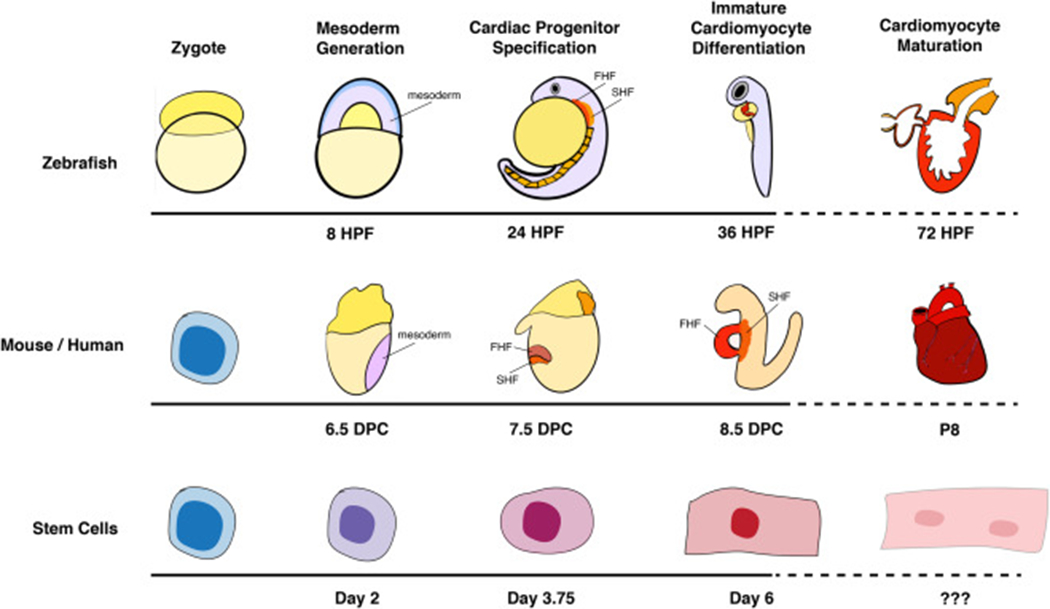

Cardiomyocyte differentiation follows a stereotypic pattern in all vertebrate animals, however, the timing of differentiation varies across model organisms (Fig. 1). Pluripotent cells within the embryonic mesoderm undergo a series of sequential stages of differentiation, from mesoderm to cardiac progenitor to immature cardiomyocyte to mature cardiomyocytes [5]. Progress along this differentiation trajectory is subject to regulation by many factors that bring about dynamic shifts in gene expression [10,12,13,17–19], histone remodeling [10,17,20] and global chromatin reorganization [21–23]. Decades of research have identified a kernel of co-expressed and essential lineage-determining transcription factors (TFs) that drives cardiac differentiation forward [8]. Mutations to components of this network lead to CHD and cardiomyopathy in both humans and most known animal models, underscoring the importance of transcriptional regulation for morphogenesis and function. The evolutionary conservation of this transcriptional network within Bilateria confirms the importance of intrinsic, pro-differentiation factors for the development of both simple and complex cardiac structures [5,24]. However, the progression of cells between subsequent stages of differentiation relies upon both positive and negative transcriptional control, which is, itself, often regulated by intercellular signaling mechanisms [25].

Fig. 1.

Cardiomyocyte differentiation timing varies across model systems. Researchers use a variety of model systems to study cardiomyocyte differentiation, including zebrafish and mouse embryos and in vitro models such as mouse or human embryonic stem cells (ESCs) or human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs). The broad stages of cardiomyocyte differentiation are shown, and the developmental timepoints at which select models transition from one differentiation stage to the next is noted. HPF, hours post-fertilization; DPC, days post-conception.

Beginning with the discovery of the embryonic second heart field (SHF) [26–28], the significance of extrinsic regulators that modulate the progress of cardiomyocyte differentiation began to be appreciated. The mammalian heart is generated primarily from two distinct pools of progenitors, entitled based on their order of differentiation. First heart field (FHF) cardiac progenitors are the first to differentiate and form the primitive heart tube, which functions to drive the circulatory system in the early embryo. SHF cardiac progenitors differentiate later and contribute cells to the heart throughout the course of cardiac development, eventually forming the atrial septum in the inflow tract and portions of the right ventricle and the pulmonary artery in the outflow tract [29–34]. Disruptions to SHF addition result in CHD, suggesting that appropriately delayed differentiation of the SHF is essential to the ontogeny of critical cardiac structures [35–39]. Importantly, while the pro-differentiation cardiogenic TF kernel is expressed in both the FHF and SHF, many of the factors that delay cardiomyocyte differentiation in SHF progenitors are also utilized in the development of non-cardiac tissues [40]. These signaling pathways interact with the cardiogenic kernel in complex interdependent but incompletely understood mechanisms to drive the tempo of cardiomyocyte differentiation [41–44]. These studies have shifted our understanding of cardiomyocyte differentiation from a linear, uninterrupted process to one under tight, push-pull temporal regulation, and have shed light on the etiologies of CHD that stems from aberrant cardiac differentiation timing.

The recent development of in vitro models of cardiac differentiation, including the use of mouse or human embryonic stem cells (ESC) and human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs), have also uncovered important positive and negative regulators of cardiac differentiation stage transitions (Fig. 1) [45–49]. These systems allow for fine-scale temporal dissection of isolated genetic and epigenetic regulatory events governing cardiac differentiation. Further, direct and indirect cardiac reprogramming experiments have established the sufficiency of transcriptional regulators to drive cardiac differentiation in vitro within a defined signaling environment and chromatin landscape [50–55]. The ability to easily modify the culture conditions used in these systems has helped illuminate mechanistic interactions between extrinsic signaling cues and intrinsic transcriptional regulators indispensable for the temporal control of cardiomyocyte differentiation [9,12,56–61].

Tight temporal control of cardiomyocyte differentiation timing is essential for the morphogenesis and physiologic function of the heart, and knowledge of this process is beginning to be leveraged in the search for regenerative cardiac therapies. While some studies on cardiac regeneration claimed to find evidence supporting the presence of cardiac stem cells resident in the adult heart [62,63], it is now clear that such stem cells are not present in appreciable numbers in the adult mammalian heart. Instead, recent studies demonstrating cardiac regeneration in mammalian hearts overwhelmingly point to the de-differentiation of mature cardiomyocytes as a more plausible mechanism governing regenerative potential [64–71]. Given these findings, the reactivation of developmental pathways in mature cardiomyocytes represents a promising avenue for improving mammalian cardiac regeneration [72]. Moving forward, a deeper understanding of the regulatory networks positively and negatively governing cardiac differentiation will be central to our understanding of normal heart development and physiology, the prevention of CHD and therapies for cardiac repair.

2. Temporal control of early cardiomyocyte differentiation

2.1. Cardiac mesoderm commitment

The earliest steps in cardiomyocyte differentiation involve the generation of mesoderm through inductive signaling events during gastrulation [73,74]. In vertebrates, this process begins during the initiation of gastrulation when the three embryonic germ layers are generated from undifferentiated cells by overriding the pluripotency gene network [75–77]. Following the induction of gastrulation, cells fated to become cardiomyocytes are among the first of the nascent mesoderm populations that migrate through the primitive streak [78–80]. Specification and migration of mesoderm precursors towards the anterior aspect of the embryo is directed by the movement of cells through the primitive streak, largely coordinated by the Wnt and Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF) signaling pathways, respectively [75,81–85].

The Wnt signaling pathway has a well-established role in mesoderm development, where it is required for primitive streak initiation, and disruptions to the Wnt signaling pathway result in deficits in mesoderm specification and subsequent cardiac defects. Mutations to the gene encoding the WNT3 ligand result in a failure to specify mesoderm [83], while hypomorphic alleles for the Wnt transcriptional coactivator, β-catenin, result in a specific absence of anterior mesoderm including cardiac fates [85]. The dosage and timing of Wnt signaling has also been shown to be critical for controlling the number of cardiac progenitors. In zebrafish and mouse, the cardiac fields expand when Wnt is exogenously activated during early gastrulation, but subsequent cardiac crescent formation is inhibited when Wnt is activated during later stages of gastrulation (Fig. 2) [86,87]. Conversely, treatment of embryos with the Wnt antagonist DKK1 abrogates the formation of the cardiac field when applied during gastrulation, but it expands the field when applied after gastrulation [86]. In cultured pluripotent stem cells, activation of the Wnt pathway is sufficient for mesoderm induction [88], yet it delays terminal cardiac differentiation from specified cardiac progenitors [87, 89]. Functional interactions between the Wnt transactivator β-catenin and SWI/SNF complex subunit BAF250a [90] and evolving SWI/SNF subunit inclusion during the course of cardiomyocyte differentiation [91] may underlie the time-sensitivity of Wnt signaling on cardiac differentiation.

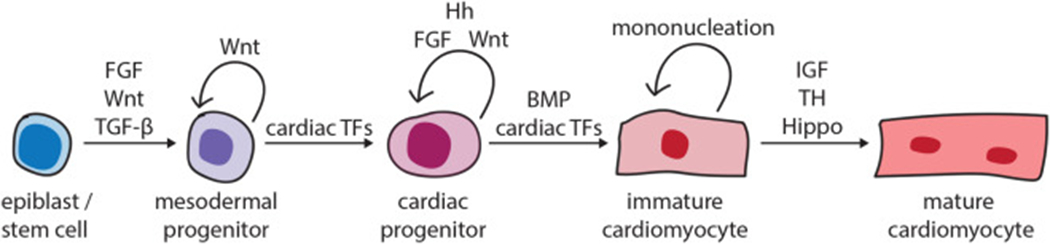

Fig. 2.

Overview of the signaling pathways that control cardiomyocyte differentiation timing. A schematic of the developmental stages that a cell transitions through during cardiomyocyte differentiation is shown from left to right. The pro-cardiac differentiation TFs or signaling pathways that promote the forward progression of a cell from one stage to the next are depicted with forward arrows. The factors that inhibit the transition of a cell to the next stage, and thus maintaining the current stage, are depicted with looped arrows. Generally, TGF-β/BMP signaling promotes the transition to the next differentiation stage, while Hh and FGF signaling inhibit or delay cardiomyocyte differentiation. The effects of Wnt signaling on cardiac differentiation timing are stage-dependent. FGF, Fibroblast Growth Factor; Hh, Hedgehog; BMP, Bone Morphogenetic Protein; IGF, Insulin-like Growth Factor; TF, transcription factor.

Cell migration plays a crucial role in cardiac fate determination. After mesoderm induction, cells fated for cardiac lineages migrate from the primitive streak to the anterior-ventral aspect of the embryo where they are specified and form the cardiac crescent [78]. The FGF pathway plays a key role in the deployment and directional migration of mesoderm precursors to the presumptive cardiac fields at the anterior aspect of the embryo (Fig. 2) [81,82]. Genetic disruption of the FGF pathway in mice results in phenotypes ranging from failure to initiate gastrulation in Fgf4 mutants [92] to severe reductions in anterior mesoderm derivatives, including absence or reduction of cardiac structures in Fgf8 and FgfR1 mutants [81,82]. Mechanistically, the FGF pathway has been shown to coordinate cell movements during gastrulation through both increased chemotaxis and extracellular matrix protein expression, including glycosaminoglycans [93–95]. Direct effects of FGF ligands on chemotaxis-mediated migration has also been observed in chicken embryo explants [95], suggesting that a primary role for early FGF signaling in cardiac development is to shepherd mesoderm cells to the anterior embryo where they subsequently receive inductive signals for cardiac lineage commitment. Additionally, a recent study has demonstrated that a Hedgehog (Hh)-FGF signaling axis promotes both cell migration during gastrulation and the acquisition of anterior mesoderm cell fates [96]. The mechanistic link between cell migration and cell fate determination during early development may be related to the strength and/or duration of cooperating signaling pathway activity. The coordinated timing of early signaling events thus ensures that a sufficient quantity of mesodermal cells is generated and allocated to the anterior pole of the developing embryo to form the early cardiac fields and cardiac crescent.

2.2. Cardiac progenitor specification

The mammalian cardiac crescent is comprised of two distinct populations of cardiac progenitors, the FHF and SHF. The lateral regions of the FHF then migrate to coalesce at the midline of the embryo to form the linear heart tube—leaving the SHF within the mesenchymal trunk of the embryo. Cells of the FHF are generated during early gastrulation and are the first to differentiate into functional cardiomyocytes to comprise the linear heart tube [97–99]. Since the discovery of the SHF [26–28], the characteristics that distinguish the two fields have been the subject of intense study. A recent genetic inducible fate map of nascent cardiac mesoderm cells in mice showed that SHF cells are already distinct from FHF progenitors by middle-to-late gastrulation [98]. Upon reaching the anterior pole of the embryo, SHF cardiac progenitors initially remain undifferentiated [40], and will later differentiation and contribute to cardiac structures in a sequential manner.

There is evidence that the final fate decisions during cardiac lineage determination are made after the migration of mesoderm into the signaling milieu at the anterior pole of the embryo. In mouse explant studies, cells originally fated to become cardiomyocytes can be induced to adopt non-cardiac fates by transplantation into the late primitive streak [78]. Conversely, cells that are not originally fated to form cardiac lineages can be induced to adopt a cardiac identity when transplanted to the early cardiac fields, implying the reception of a directive signal received by the cardiac fields [78]. The extraembryonic endoderm (ExE), which lies immediately anterior to the early heart fields, has been identified as a source of signals that control cardiomyocyte determination [98,100]. The early differentiation of FHF cardiac progenitors may rely on contact with the ExE [98,100]. In vitro studies using hiPSCs corroborate this, demonstrating that progenitors more rapidly differentiate into cardiomyocytes when co-cultured with ExE-like cells [101–103]. Endoderm-derived signals seem to promote cardiac differentiation by repressing progenitor-specific signaling pathways such as TGF-β and Wnt [57,86,104–106]. CER-1 and DKK1, which inhibit TGF-β and Wnt signaling, respectively [107–109], are expressed in the ExE proximal to the cardiac crescent and have proven roles in promoting cardiac differentiation [110,111]. In vitro, BMP and Wnt signaling contributes to differential specification of FHF and SHF progenitors [112]. On the other hand, retinoic acid signaling, which is differentially received across the anterior-posterior axis, has recently been shown to limit the number of early-differentiating FHF precursors in zebrafish [113]. It is likely that the proximity to, and length of exposure to, these signals have powerful influences in the rate of cardiac differentiation in vivo.

The completion of cardiac progenitor specification is heralded by co-expression of a deeply conserved kernel of genes encoding cardiac-specific TFs including Tbx5, Nkx2.5, and Gata4, among others, which subsequently drives the expression of genes required for terminal cardiomyocyte differentiation [5,114]. Unlike in Drosophila, where deletion of the Nkx2.5 ortholog, tinman, results in complete cardiac agenesis [115], the vertebrate cardiac gene network is redundant and mutation of a single gene rarely threatens to abrogate the specification of all cardiac progenitors. Singular deletions of Tbx5, Nkx2.5, or Gata4 result in morphological defects ranging from cardiac chamber mis-specification to cardia bifida, yet markers of terminal cardiac differentiation are still expressed in each case [116–120]. However, cardiac specification is dramatically disrupted in multi-gene knockout models involving the cardiac TFs. For example, Nkx2.5−/−; Tbx5−/− double-knockout mouse embryos, which demonstrate severely reduced expression of cardiomyocyte markers as well as cardiac agenesis [11]. Gata4−/−; Gata5−/− and Gata5−/−: Gata6−/− compound mutant mouse embryos also exhibit severe cardiac defects, as well as a reduction in the expression of other pro-differentiation cardiogenic TF-encoding genes, includingTbx20 and Mef2c [121]. Thus, while there exists some redundancy in the genes that comprise the cardiogenic TF kernel in vertebrates, the functionality of the entire kernel is required to ensure the transition from cardiac mesoderm to specified cardiac progenitor.

2.3. First Heart Field cardiomyocyte differentiation

Although individual cardiogenic TFs, including TBX5, have the capacity to directly activate expression of specific cardiac differentiation products, such as atrial natriuretic factor (Nppa) [122], the cardiogenic kernel TFs generally act both cooperatively and redundantly to promote terminal differentiation [123,124]. Recent work, for example, has shown that TBX5 and NKX2-5 cooperatively activate the transcription of early differentiation genes required for cardiac contraction, including Hcn4 and Myh7, in mouse ESC-derived cardiac progenitors (mESC-CPs) [11]. Interestingly, the onset of cardiomyocyte contraction in mESC-CPs lacking TBX5 was delayed relative to wild-type cells in these studies, while contraction occurred precociously in mESC-CPs lacking NKX2-5, suggesting a potentially antagonistic role for these TFs in the regulation of differentiation timing [11].

The hallmarks of cardiac differentiation, including sarcomeric gene expression, electrical excitation, and physical contraction, can be observed in differentiating cardiomyocytes as early as the cardiac crescent stage [125]. This timing coincides with the expression of Hcn4, which encodes a voltage-gated ion channel that is subsequently restricted to the developing pacemaker sinoatrial node and other components of the cardiac conduction system [100,126]. As the linear heart tube forms, spontaneous calcium oscillations and discrete contractile foci give way to a tissue characterized by the tight coupling of efficient calcium handling and the coordinated contraction of highly organized sarcomeres. Nascent cardiomyocytes in the linear heart tube next begin to express markers of regional identity, including those specific to the outflow tract, ventricles and atrioventricular canal, based on their relative positions adopted during gastrulation [97–99,127]. The establishment of these regional identities have consequences ranging from the localized expression of discrete cardiomyocyte transcriptional networks to differences in cardiomyocyte function and maturation potential [128]. It remains to be seen whether differences in cardiac maturation between FHF sub-populations are driven by differences in intrinsic TF networks, regional signaling, or physiologic cues from circulation.

3. Temporal control of late cardiomyocyte differentiation

The clearest distinction in differentiation timing of cardiomyocytes occurs between the FHF and the SHF. While the FHF begins the process of terminal differentiation, the majority of the SHF maintains cardiac progenitor gene expression [32]. The core cardiac TF kernel of TBX5, NKX2.5, and GATA4, required for the formation of the FHF, are also expressed in and required for SHF-derived heart structures. TBX5 and GATA4 are both required in the SHF for formation of the atrial septum [42,129], while NKX2.5 is required in the SHF for OFT development [43, 130]. The requirement of a pro-differentiation core cardiac TF expression kernel in both the FHF and SHF suggests that any distinction in the differentiation timing between the fields may be an extrinsic signal limited to the SHF. Given their SHF activity, several signaling pathways are likely key to understanding the mechanics governing the distinct tempo of cardiac differentiation between the two heart fields. In fact, many of the interactions between the cardiac TFs and signal-dependent TFs, described below, exhibit opposing forces balancing maintenance of the progenitor state and differentiation.

Several signaling pathways active in the SHF function to maintain the proliferative progenitor state, in opposition to the differentiation cues provided by the TF kernel (Fig. 2). Hh signaling has canonically been associated with maintenance of the proliferative state in numerous developmental contexts [131–133]. Mesodermal SHF progenitors receive SHH ligand from the adjacent pulmonary endoderm directing them to perpetuate proliferation [134], and the inhibition of Hh signaling has been shown to limit proliferation within SHF (Fig. 2) [134, 135]. Recent work has shown that Hh-dependent TFs within the SHF can indirectly regulate cell cycle control [129], suggesting a mechanism underlying the ability of Hh signaling to maintain the proliferative state of SHF. Hh signaling can also prevent the premature differentiation of cardiomyocyte progenitors in the SHF [136,137], although the underlying mechanism remains to be established.

Maintenance of the proliferative status of the SHF also relies on Wnt signaling, enacted via β-catenin TF activity [86,138–141]. However, when SHF progenitors begin to migrate into the heart tube, the repression of canonical Wnt/β-catenin is required for cardiac differentiation [142,143]. Studies addressing the mechanisms of canonical Wnt/β-catenin repression within the SHF have shown that expression of Hopx [142] and the non-canonical Wnt ligands, Wnt5a and Wnt11 [143] are required for this repression. Together, these studies indicate that control of Wnt signaling may be essential for the timing of cardiac differentiation within the SHF.

FGF signaling promotes SHF progenitor cell proliferation [43,144, 145]. Interestingly, the discovery of the SHF in mice and zebrafish was based on FGF ligand-expressing domains that were shown to be required for development of the arterial pole [26] or ventricles [146]. In murine models, loss of Fgf8 decreased proliferation and progenitor survival resulting in defects in the SHF-derived OFT [144,145,147]. Fgf10 also promotes SHF progenitor proliferation independent of cardiac specification, and coordinates with Fgf3 and Fgf8 in a dosage-sensitive manner to regulate OFT morphogenesis [43,148]. Fgf8/10 are activated by the SHF-expressed TF TBX1 [43,149], demonstrating a direct interplay between intrinsic cardiac transcriptional regulators and intercellular signaling pathways. Indeed, the expression of Fgf10 is tightly controlled by opposing positive and negative regulation from the progenitor-specific activity of TBX1 and ISL1 in the SHF and the cardiomyocyte-specific activity of NKX2–5 in the differentiating OFT, thereby restricting pro-proliferative signaling to the progenitor state [43]. Retinoic acid (RA) signaling antagonizes TBX1 function and restricts FGF and ISL1-mediated proliferation to the anterior aspect of the SHF [150–152], while priming the expression of atrial cardiomyocyte differentiation genes, such as Nppa, via TBX5 induction in the posterior SHF [120,151,153,154].

Not only does FGF signaling maintain the proliferative state of cardiac progenitors, it has also been implicated in the control of migration rate of SHF progenitors into the heart tube, therefore influencing the timing of their differentiation. In zebrafish, Fgf8 is upstream of cell adhesion molecule 4, Cadm4, which was shown to facilitate the deployment of SHF cells into the heart tube [155], suggesting a role for the extracellular matrix in SHF accretion. Other studies have also shown an association between the extracellular matrix and SHF migration. In mice, SHF progenitors express higher levels of Cdh2/N-CAD to prevent premature deployment and differentiation, thus allowing the SHF to maintain a proliferative state [156]. Additionally, new work has shown that Tbx1 also supports the expression of extracellular matrix proteins required for proper progenitor migration into the OFT and OFT elongation [157]. Interestingly, work in zebrafish has shown that increased expression of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (Mmp9), due to inappropriately high activity of the RA signaling pathway, disrupts the extracellular matrix environment leading to defects in SHF migration and addition to the heart [158]. Furthermore, SHF cells that failed to migrate into the heart adopted alternative fates, suggesting that migration was essential for engaging signaling environments that promoted cardiomyocyte differentiation. C-X-C chemokine receptors (CXCR2/4) expressed in the SHF are also important for progenitor accretion into the heart [112,159–161], and this pathway is known to be activated in the SHF by the cardiogenic TF NKX2-5 [162]. Together, these studies link the extracellular matrix and migratory signals to SHF progenitor state maintenance and morphogenetic behavior.

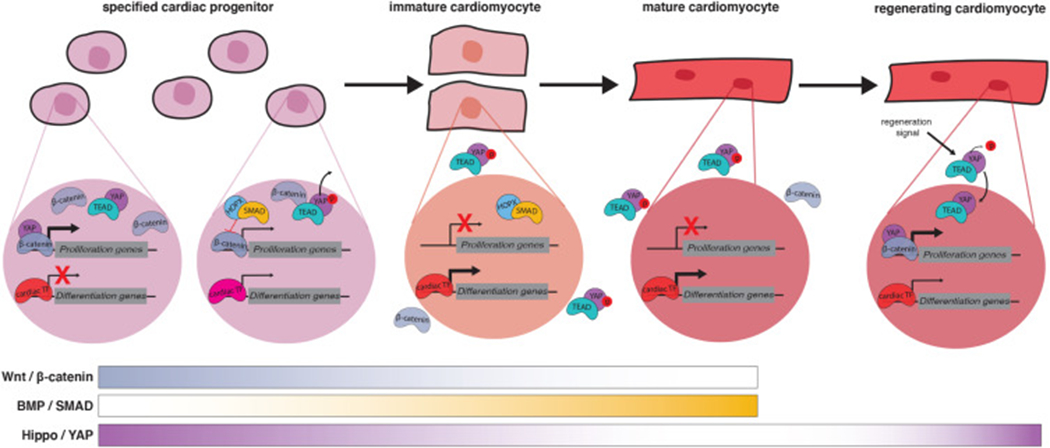

As SHF-derived cardiac progenitors migrate into the heart tube, they encounter high levels of Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP) pathway activity (Figs. 2 and 3), which opposes the progenitor-maintaining effects of the Hh, Wnt and FGF pathways. BMP2 and BMP4 are each individually sufficient to induce cardiac differentiation within the developing chick, even when ectopically expressed in non-cardiogenic mesoderm [163]. In zebrafish, there is a dose-dependent correlation between BMP levels and cardiomyocyte number [164]. Moreover, studies across numerous model organisms have established an important conserved role for BMP in inducing and maintaining Nkx2.5 expression to promote terminal cardiac differentiation [163,165,166]. BMP signaling activation in differentiating cardiomyocytes is coincident with Wnt signaling downregulation, mediated in part through the association of BMP SMAD TFs with the HOPX TF [142]. Thus, BMP signaling likely functions to oppose the progenitor-maintaining signaling pathways of the SHF to initiate terminal cardiomyocyte differentiation as cells enter the heart.

Fig. 3.

Evolving signaling and transcriptional networks during cardiac differentiation and regeneration. A differentiation trajectory, focused on the transitions occurring between the cardiac progenitor and mature cardiomyocyte stages, is shown from left to right. Cardiac progenitors, immature cardiomyocytes and mature cardiomyocytes all express cardiogenic transcription factors (TFs) that promote cardiac differentiation transitions and maintain the expression of cardiac differentiation products. Signaling pathway-dependent TFs are also active in the nucleus of differentiating progenitors and can facilitate, or counteract, the activity of the cardiogenic TFs. Examples of signal-dependent transcriptional regulation active during cardiomyocyte differentiation are shown. Early cardiac progenitors experience high levels of Wnt and Hippo signaling, and their TFs β-catenin and YAP facilitate the activation of pro-proliferation genes, a hallmark of the progenitor state. As cardiac progenitors begin to differentiate, β-catenin is inhibited by BMP signaling SMAD TFs and YAP is phosphorylated and shuttled out of the nucleus, resulting in the de-activation of proliferation genes and the preponderance of pro-differentiation gene expression. Re-activation of the Hippo pathway in terminally differentiated cardiomyocytes can increase their proliferation rate, thereby promoting cardiac regeneration after injury. BMP, Bone Morphogenetic Protein; YAP, Yes Associated Protein; TEAD, TEA Domain.

Thus, a combination of evolving exposure to signaling networks and changes to the extracellular matrix work in a coordinated fashion to control the rate of SHF differentiation (Figs. 2 and 3). It may therefore be unsurprising that recent work has also suggested that the timing of SHF addition to the heart tube is itself important for cardiac identity. SHF addition occurs at distinct intervals for SHF sub-populations that give rise to the different SHF-derived structures, such as the right ventricle, outflow tract and great arteries [167]. These findings imply that the timing of differentiation is a controlled process that leads to formation of distinct cardiac structures. Moreover, this work also implies a link to temporal regulation of cardiac region specification, which warrants further study. Together, layering a temporal gene expression map with gene regulatory networks will provide new insights into the signals that drive differentiation and the opposing signals that maintain the proliferative progenitor state and prevent premature differentiation.

4. Temporal control of postnatal cardiomyocyte differentiation

While contractile cardiomyocytes are found as early at 8.0 DPC (days post-conception) in the mouse embryo, terminal differentiation and complete cardiac maturation is not achieved until the postnatal period [127,168]. Cardiomyocyte maturation imbues adult cardiomyocytes with the structural, metabolic, and functional characteristics required for efficient contraction and coordinated electrical impulse conduction [127,169,170]. In rodents, the transformations required for maturation are enacted concurrently after birth, and maturation is complete after the first month of postnatal life [171,172]. Bulk and single-cell gene expression studies demonstrate that the expression of the pro-differentiation cardiogenic TF kernel remains largely unchanged throughout cardiac maturation, suggesting that it is unlikely to play a dominant role [11,13,17,173]. As the final step in cardiomyocyte differentiation, maturation occurs within a specific postnatal window, suggesting that its initiation and conclusion are instead likely governed by postnatal signaling mechanisms and is controlled by an interplay of structural, hormonal, and metabolic cues [170].

A robust capacity for proliferation is a hallmark of cardiomyocyte immaturity observed in embryonic and fetal hearts, and hyperplasia is responsible for the majority of prenatal cardiac growth [171]. In the developing heart, proliferation is incited and maintained in cardiomyocytes by several signaling pathways, including Insulin-like Growth Factor (IGF) signaling from the epicardium [174], and the mitogenic transcriptional activator Yes Associated Protein (YAP), a component of the Hippo signaling pathway which regulates organ size (Fig. 3) [175]. However, cardiomyocyte proliferation rates decrease dramatically during the first week after birth, heralding the onset of cardiac maturation [172,176]. Thereafter, a 40-fold increase in the size of the adult heart is achieved through hypertrophy, rather than proliferation [177].

Cell cycle exit after birth is triggered both by decreased mitotic signaling, including sequestration of YAP from the nucleus [178], and increased signaling that actively inhibits components of the cell cycle machinery. For example, p38 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase signaling inhibits the expression of genes encoding the cell cycle regulators Cyclin A and Cyclin B, and its activity is inversely correlated with postnatal cardiac growth in rats [179]. DNA damage signaling due to the oxidative stress response in postnatal cardiomyocytes is also essential for cell cycle exit [180], demonstrating an intimate linkage between maturation timing and shifting environmental contexts. While proliferation decreases dramatically in the postnatal heart, both mouse and human cardiomyocyte nuclei continue to synthesize new DNA without subsequent cell division, and thus diploid binucleation of the majority of mouse cardiomyocytes [171] and polyploid mononucleation of the majority of human cardiomyocytes [171,172,181,182] are hallmarks of cardiomyocyte maturation. Thyroid hormone (TH) and IGF-1 signaling in the neonatal period are known to promote increased binucleation of cardiomyocytes, and thyroidectomized sheep fetuses demonstrate reduced binucleation [115,183,184].

Maturing cardiomyocytes also undergo extensive metabolic remodeling, facilitated by a transition from anaerobic glycolysis to oxidative metabolism coincident with an increase in mitochondrial density beginning immediately after birth [185]. Environmental factors, such as increased oxygen and fatty acid availability and increased hemodynamic load after birth are thought to trigger this metabolic shift through activation of ligand-dependent nuclear receptor pathways, including the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) and TH signaling pathways, and ligand-independent nuclear receptor pathways such as the estrogen-related receptor (ERR) pathway [186–191]. Metabolic remodeling is not only a marker of cardiomyocyte maturation, multiple groups have shown that inhibition of mitochondrial function itself can disrupt cardiac differentiation, suggesting that cardiomyocyte maturation is dependent upon efficient conversion to oxidative metabolism [192–194].

Structurally, maturation of cardiomyocytes requires subcellular reorganization to ensure effective membrane depolarization, electrical impulse propagation and contraction. While cells exit the cell cycle, they concomitantly activate the expression of genes encoding the adult isoforms of sarcomeric proteins, including Titin (Ttn) [195–197], Troponin I (Tnni1-3) [198,199], and Myomesin (Myom1-3) [200]. The mechanisms that initiate sarcomere isoform switching are not yet well characterized, however IGF-1 [115] and TH treatment [183,184] are known to promote fetal to adult isoform switching, suggesting that the main neonatal regulators may be neurohormonal. Maturation is also characterized by increasing organization of sarcomeres and the sarcomeric reticulum [72,168]. Sarcomere alignment is also regulated by TH signaling [183,184] as well as by cell shape [201]. Further evidence that signaling through the cytoskeleton is essential for maturation is provided by studies demonstrating the importance of transverse tubule (T-tubule) formation. T-tubules are invaginations of the sarcolemma that optimize cardiomyocyte depolarization potential, and their malformation or disruption leads to altered calcium handling and arrhythmias [202–204]. T-tubule formation is a maturation hallmark first observed around 2 weeks after birth in rodents and is complete by one month after birth, making it one of the last events in the postnatal cardiac maturation process [205–207].

Efforts to generate fully mature cardiomyocytes in vitro through directed differentiation have been minimally successful, even in very long-term culture systems, likely due to the necessity of missing environmental inputs [168]. Indeed, transplantation of immature cardiomyocytes cultured in vitro into primate hearts permits the completion of the differentiation process and functional contribution to the adult heart [202,208]. Several groups have elicited improvements in cardiac maturation in vitro with modifications to attachment substrate stiffness [209,210], media compositions that include IGF or TH [211,212], substrate organization [213–215], electrical stimulation [216,217], and the combination of substrate organization and electrical stimulation [218]. For example, in vitro maturation can be achieved with exercise-induced contraction of cardiomyocytes after only 4 weeks in culture [61]. These results demonstrate that cell-ECM interactions and the mechanical loading experienced during muscular contractions are integral parts of functional maturation. In mice, however, the primitive heart tube begins contracting near 8.0 DPC, long before functional maturation, suggesting that the act of contracting itself is insufficient to complete cardiomyocyte maturation. However, the time-dependent signaling pathways that provoke these functional and structural changes in the postnatal period, as well as the downstream gene expression changes that enact them, are unknown.

Genomic and epigenomic analyses undertaken in actively maturing cardiomyocytes will shed light on the signaling pathways and regulators critical for the timing of this process. Interestingly, cardiac maturation is also enhanced by the presence of non-cardiomyocytes, implicating intercellular cross-talk between distinct cell types in the final stage of cardiac differentiation. While embryonic fibroblasts induce proliferation in cardiomyocytes through ECM-mediated paracrine signaling [219], numerous studies have shown that adult fibroblasts and endothelial cells promote cardiomyocyte maturation in vitro [220–224] and in the postnatal mouse heart [225]. Single cell analyses have revealed that alterations in fibroblast gene expression in the postnatal mouse heart impacts BMP signaling and correlates with cardiomyocyte maturation [226], demonstrating a continued role for BMP signaling in cardiomyocyte differentiation. This work supports consideration of interactions between the distinct cell lineages comprising the heart in the control of maturation and response to injury, both of which are intimately tied to regenerative potential [227].

5. Cardiac regeneration

Cardiac maturation in the mammalian heart, which is critical for adult heart function, depletes the cardiac progenitor pool, creating a barrier to cardiac regeneration. In contrast to the zebrafish heart, which maintains the capacity for cardiomyocyte regeneration into adulthood, the neonatal mouse heart is capable of full structural and functional regeneration only prior to postnatal day 7 (P7), after which regenerative capacity rapidly deteriorates [176]. This suggests that terminal mammalian cardiomyocyte maturation is a barrier to regeneration. Initial reports of a residual proliferative pool of cardiac progenitors capable of contributing to cardiac regeneration in the neonate have not been substantiated [62,228], and genetic fate mapping points instead to a differentiated myocyte source of regenerated cardiomyocytes in the neonatal mouse heart [69,176]. A thorough understanding of the cues controlling the transition of cardiac progenitors into mature cardiomyocytes is essential to our ability to harness the power of regeneration to repair cardiac defects or injuries. Current attempts to understand and improve cardiac regenerative potential utilize three very distinct approaches that nevertheless all center around knowledge of cardiac differentiation stage transitions to trigger re-entry of differentiated cardiomyocytes into an earlier stage of the differentiation process.

The first approach involves the mobilization of mitogenic developmental signaling pathways that reactivate proliferation in pre-existing, terminally differentiated cardiomyocytes located in the heart [229]. Fully mature cardiomyocytes under normal adult mammalian physiology exit the cell cycle and are therefore unable to replace damaged cardiomyocytes upon injury. Developmentally-active signaling pathways have been harnessed to force the re-initiation of cardiac proliferation. Reactivation of YAP, a mitogenic TF in the Hippo signaling pathway that is downregulated postnatally stimulates cardiomyocyte proliferation in adult infarcted hearts [230]. Remarkably, the patterning of adult cardiomyocytes remains intact, through an unknown mechanism [230]. Hippo signaling normally functions to inhibit Wnt signaling, attenuating cardiomyocyte proliferation and heart size [175]. Wnt signaling actively promotes cardiac progenitor proliferation in the FHF and SHF [86,142,231], and in injured adult zebrafish hearts [232,233], suggesting that it may represent a therapeutic target, provided its oncogenic potential can be restrained. However, it appears that Wnt/β-catenin signaling has a limited capacity to activate its progenitor target genes in adult cardiomyocytes thus failing to drive a strong proliferative response in injured hearts [234]. Inhibiting p38 MAP kinase signaling, which is activated during cardiac maturation, also improves regeneration [235]. IGF signaling, a driver of fetal cardiomyocyte proliferation, is required for zebrafish heart regeneration, suggesting that adult zebrafish may preserve the capacity for cardiac regeneration in part through the maintenance of developmental signaling pathways [236]. Neuregulin-1 (NRG1), signaling through the developmentally-expressed ERBB2, also improves cardiac function in zebrafish and mouse adult hearts post-injury [237–239], and there is evidence that this pathway may stimulate cardiomyocyte proliferation through interaction with the Hippo pathway [240]. In the regenerating zebrafish myocardium, expression of erbb2 is activated by another developmental signaling pathway, Notch, in the endocardium [241,242]. Hh signaling, which promoted proliferation and prevents premature differentiation of cardiomyocytes in the SHF [137] is essential for epicardial regeneration in zebrafish [243] and extends the window of myocardial regeneration in the mouse [244]. FGF signaling is also required for the survival of some cardiomyocytes during zebrafish cardiac regeneration [245], though most of its activity seems to be directed toward neovascularization [246,247]. In addition to the reactivation of developmental signaling pathways, cardiac regeneration can also be facilitated by inhibiting maturation stage signals. TH signaling promotes cardiac functional maturation, and inactivating this signaling pathway resulted in a prolonged regenerative window in mice [248]. All of these methods seek to trigger proliferation and regeneration in the adult heart by leveraging knowledge of signaling pathways that normally function to modulate cardiac progenitor differentiation timing in the developing embryo.

The potential of these signaling pathways to incite proliferation appears predicated on the potential for “dedifferentiation” of cardiomyocytes, as assessed by sarcomere disassembly and increased proliferation. Polyploidy has been identified as a barrier to this type of cardiomyocyte proliferation and regeneration [249,250]. An open question remains how developmental signaling pathway activation overcomes this barrier to force dedifferentiation and proliferation of polyploid cells, or whether instead proliferation and regeneration is only triggered in diploid cells. Interestingly, ECT2, a cytokinesis regulator whose impairment leads to polyploidy [250] is also a target of YAP [251] suggesting that Hippo signaling may control dedifferentiation and proliferation through direct control of the cell cycle. In at least some cases, the pro-regenerative effect of the NRG1 and IGF intercellular signaling pathways has been shown to be mediated through mono-nucleated cardiomyocytes [237,238,252]. Furthermore, the degree of regenerative capacity of mouse strains has been linked to the percentage of mononucleated cardiomyocytes [249]. This observation suggests that pausing cardiomyocyte differentiation prior to the terminal phase of multinucleation may provide a reservoir of immature myocytes that can be subsequently activated to divide and repair the heart via intercellular mitogenic signaling pathways.

A second approach to increasing regenerative efficiency involves the transplantation of in vitro derived cardiac progenitors or immature cardiomyocytes into the injured adult heart. Introduction of human ESC (hESC)-derived immature cardiomyocytes into a non-human primate model of myocardial ischemia caused improved physiologic function, although maturation of transplanted cells was incomplete [202]. Another group introduced immature myocardial patches made from hiPSCs into a porcine model of myocardial infarction [253]. The patches successfully engrafted into the host myocardium and improved regenerative capacity without contributing to arrhythmogenicity. These techniques take advantage of the signaling environment present in the adult heart to prompt the maturation and terminal differentiation of immature, in vitro-derived cardiomyocytes after they are transplanted into the heart, thus eliciting a cardiac repair process that may mimic normal cardiomyocyte maturation. The constituents of the signaling environment within the adult heart that elicit this maturation have yet to be defined.

Lastly, several groups are now attempting to repair the adult heart using developmental paradigms to bypass the signaling mechanisms controlling the timing of cardiac differentiation. Direct reprogramming of postnatal fibroblasts into cardiomyocytes, without the need for a cardiac progenitor, can be achieved through the introduction of a core set of cardiogenic TFs, including GATA4, MEF2C and TBX5 [50,254,255]. Fibroblasts transduced with these factors in vitro and then injected into the mouse heart trans-differentiated into cardiomyocytes. However, while in vitro reprogramming with these factors circumvents signal-dependent control of cardiac differentiation, it is clear that the signaling environment still plays a critical role in the subsequent maturation of reprogrammed cardiomyocytes, especially in terms of the epigenetic landscape [50]. In vivo reprogramming of non-myocytes in the injured mouse heart led to the differentiation of cardiomyocytes with a functionally mature phenotype [52,53], implying the presence of a yet to be identified, pro-maturation signal inherent in the heart that is required for full regenerative potential. While the positive signal remains elusive, TGF-β signaling impairs direct reprogramming potential of mammalian fibroblasts to cardiomyocytes, as its blockade is required for the epigenetic transformation enacted by the reprogramming cardiogenic TFs [256].

All of the above approaches to improve cardiac regeneration hold tremendous promise. Ultimately, however, the ability to optimally control cardiac regeneration will rely on the ability to both positively and negatively regulate the cardiac differentiation process to tightly control the number of regenerated cardiomyocytes produced. Lessons learned from developmental switches governing the timing of cardiomyocyte differentiation state transitions will inform our ability to activate, and de-activate, cardiac regeneration at the appropriate time.

6. Conclusion

A complete understanding of the pro- and anti-differentiation forces modulating cardiac differentiation timing is essential to the ultimate goals of understanding the etiologies of CHD and the basis of mammalian cardiac regeneration. Regulatory networks mediated by intercellular signaling pathways are required for all stages of cardiac differentiation and regeneration. Signaling pathway components represent some of the most amenable therapeutic targets, and the recurrent involvement of certain signaling pathways, including Wnt, Hippo and Hh, at multiple cardiac differentiation and regeneration stages suggests that a future focus on these pathways is warranted. The positive and negative differentiation factors that compose this cellular cross-talk in mice and humans are being elucidated [13,18,96,97,257–262]. Such studies will be key to unveiling the combined effects of signaling effectors and transcriptional regulators to promote the global restructuring that will likely be required for functional mammalian cardiac regeneration.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the NIH/NHLBI: R01 HL092153 (I.P.M), R01 HL124836 (I.P.M), R01 HL126509 (I.P.M), R01 HL147571 (I.P.M), NIH/NHLBI NRSA T32 HL007381-36/37 (M.R. and A.R.) and NIH/NHLBI F32 HL136168-01 (M.R.), AHA Postdoctoral Fellowship 17POST33670937 (M.R.) NIH/NHLBI F30 HL136200 (A.G.) and AHA Predoctoral Fellowship 17PRE33411203 (A.G.).

References

- [1].Hoffman JI, Incidence of congenital heart disease: II. Prenatal incidence, Pedia Cardiol. 16 (4) (1995) 155–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Gelb BD, Genetic basis of congenital heart disease, Curr. Opin. Cardiol 19 (2) (2004) 110–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Gelb BD, Chung WK, Complex genetics and the etiology of human congenital heart disease, Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med 4 (7) (2014), 013953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Olson EN, A decade of discoveries in cardiac biology, Nat. Med 10 (5) (2004) 467–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Olson EN, Gene regulatory networks in the evolution and development of the heart, Science 313 (5795) (2006) 1922–1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Srivastava D, Making or breaking the heart: from lineage determination to morphogenesis, Cell 126 (6) (2006) 1037–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Dunwoodie SL, Combinatorial signaling in the heart orchestrates cardiac induction, lineage specification and chamber formation, Semin. Cell Dev. Biol 18 (1) (2007) 54–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Bruneau BG, The developmental genetics of congenital heart disease, Nature 451 (7181) (2008) 943–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kattman SJ, Witty AD, Gagliardi M, Dubois NC, Niapour M, Hotta A, Ellis J, Keller G, Stage-specific optimization of activin/nodal and BMP signaling promotes cardiac differentiation of mouse and human pluripotent stem cell lines, Cell Stem Cell 8 (2) (2011) 228–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Wamstad JA, Alexander JM, Truty RM, Shrikumar A, Li F, Eilertson KE, Ding H, Wylie JN, Pico AR, Capra JA, Erwin G, Kattman SJ, Keller GM, Srivastava D,Levine SS, Pollard KS, Holloway AK, Boyer LA, Bruneau BG, Dynamic and coordinated epigenetic regulation of developmental transitions in the cardiac lineage, Cell 151 (1) (2012) 206–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Luna-Zurita L, Stirnimann CU, Glatt S, Kaynak BL, Thomas S, Baudin F, Samee MA, He D, Small EM, Mileikovsky M, Nagy A, Holloway AK, Pollard KS, Müller CW, Bruneau BG, Complex interdependence regulates heterotypic transcription factor distribution and coordinates cardiogenesis, Cell 164 (5) (2016) 999–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Loh KM, Chen A, Koh PW, Deng TZ, Sinha R, Tsai JM, Barkal AA, Shen KY, Jain R, Morganti RM, Shyh-Chang N, Fernhoff NB, George BM, Wernig G, Salomon R, Chen Z, Vogel H, Epstein JA, Kundaje A, Talbot WS, Beachy PA, Ang LT, Weissman IL, Mapping the pairwise choices leading from pluripotency to human bone, heart, and other mesoderm cell types, Cell 166 (2) (2016) 451–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].DeLaughter DM, Bick AG, Wakimoto H, McKean D, Gorham JM, Kathiriya IS, Hinson JT, Homsy J, Gray J, Pu W, Bruneau BG, Seidman JG, Seidman CE, Single-cell resolution of temporal gene expression during heart development, Dev. Cell 39 (4) (2016) 480–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Raff MC, Abney ER, Fok-Seang J, Reconstitution of a developmental clock in vitro: a critical role for astrocytes in the timing of oligodendrocyte differentiation, Cell 42 (1) (1985) 61–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Amthor H, Christ B, Weil M, Patel K, The importance of timing differentiation during limb muscle development, Curr. Biol 8 (11) (1998) 642–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kopan R, Chen S, Little M, Nephron progenitor cells: shifting the balance of self-renewal and differentiation, Curr. Top. Dev. Biol 107 (2014) 293–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].He A, Gu F, Hu Y, Ma Q, Ye LY, Akiyama JA, Visel A, Pennacchio LA, Pu WT, Dynamic GATA4 enhancers shape the chromatin landscape central to heart development and disease, Nat. Commun 5 (2014) 4907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Li G, Xu A, Sim S, Priest JR, Tian X, Khan T, Quertermous T, Zhou B, Tsao PS, Quake SR, Wu SM, Transcriptomic profiling maps anatomically patterned subpopulations among single embryonic cardiac cells, Dev. Cell 39 (4) (2016) 491–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Jia G, Preussner J, Chen X, Guenther S, Yuan X, Yekelchyk M, Kuenne C, Looso M, Zhou Y, Teichmann S, Braun T, Single cell RNA-seq and ATAC-seq analysis of cardiac progenitor cell transition states and lineage settlement, Nat. Commun 9 (1) (2018) 4877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Liu Q, Jiang C, Xu J, Zhao MT, Van Bortle K, Cheng X, Wang G, Chang HY, Wu JC, Snyder MP, Genome-wide temporal profiling of transcriptome and open chromatin of early cardiomyocyte differentiation derived from hiPSCs and hESCs, Circ. Res 121 (4) (2017) 376–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Paige SL, Thomas S, Stoick-Cooper CL, Wang H, Maves L, Sandstrom R, Pabon L, Reinecke H, Pratt G, Keller G, Moon RT, Stamatoyannopoulos J, Murry CE, A temporal chromatin signature in human embryonic stem cells identifies regulators of cardiac development, Cell 151 (1) (2012) 221–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Montefiori LE, Sobreira DR, Sakabe NJ, Aneas I, Joslin AC, Hansen GT, Bozek G, Moskowitz IP, McNally EM, Nóbrega MA, A promoter interaction map for cardiovascular disease genetics, Elife 7 (2018) 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Fields PA et al. , Dynamic reorganization of nuclear architecture during human cardiogenesis. bioRxiv, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- [24].Cui M, Wang Z, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN, Genetic and epigenetic regulation of cardiomyocytes in development, regeneration and disease, Development 145 (24) (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Davidson EH, Later embryogenesis: regulatory circuitry in morphogenetic fields, Development 118 (3) (1993) 665–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kelly RG, Brown NA, Buckingham ME, The arterial pole of the mouse heart forms from Fgf10-expressing cells in pharyngeal mesoderm, Dev. Cell 1 (3) (2001) 435–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Mjaatvedt CH, Nakaoka T, Moreno-Rodriguez R, Norris RA, Kern MJ, Eisenberg CA, Turner D, Markwald RR, The outflow tract of the heart is recruited from a novel heart-forming field, Dev. Biol 238 (1) (2001) 97–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Waldo KL, Kumiski DH, Wallis KT, Stadt HA, Hutson MR, Platt DH, Kirby ML, Conotruncal myocardium arises from a secondary heart field, Development 128 (16) (2001) 3179–3188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Dyer LA, Kirby ML, The role of secondary heart field in cardiac development, Dev. Biol 336 (2) (2009) 137–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Vincent SD, Buckingham ME, How to make a heart: the origin and regulation of cardiac progenitor cells, Curr. Top. Dev. Biol 90 (2010) 1–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Zaffran S, Kelly RG, New developments in the second heart field, Differentiation 84 (1) (2012) 17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kelly RG, The second heart field, Curr. Top. Dev. Biol 100 (2012) 33–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Francou A, Saint-Michel E, Mesbah K, Théveniau-Ruissy M, Rana MS, Christoffels VM, Kelly RG, Second heart field cardiac progenitor cells in the early mouse embryo, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1833 (4) (2013) 795–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kelly RG, Buckingham ME, Moorman AF, Heart fields and cardiac morphogenesis, Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med 4 (10) (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Yamagishi H, Maeda J, Uchida K, Tsuchihashi T, Nakazawa M, Aramaki M, Kodo K, Yamagishi C, Molecular embryology for an understanding of congenital heart diseases, Anat. Sci. Int 84 (3) (2009) 88–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Parisot P, Mesbah K, Théveniau-Ruissy M, Kelly RG, Tbx1, subpulmonary myocardium and conotruncal congenital heart defects, Birth Defects Res. A Clin. Mol. Teratol 91 (6) (2011) 477–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Chin AJ, Saint-Jeannet JP, Lo CW, How insights from cardiovascular developmental biology have impacted the care of infants and children with congenital heart disease, Mech. Dev 129 (5–8) (2012) 75–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Neeb Z, Lajiness JD, Bolanis E, Conway SJ, Cardiac outflow tract anomalies, Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Dev. Biol 2 (4) (2013) 499–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Francou A, Kelly RG, Properties of cardiac progenitor cells in the second heart field, in: Nakanishi T et al. (Eds.), Etiology and Morphogenesis of Congenital Heart Disease: From Gene Function and Cellular Interaction to Morphology, Tokyo, 2016, pp. 177–182. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Rochais F, Mesbah K, Kelly RG, Signaling pathways controlling second heart field development, Circ. Res 104 (8) (2009) 933–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Prall OW, Menon MK, Solloway MJ, Watanabe Y, Zaffran S, Bajolle F, Biben C, McBride JJ, Robertson BR, Chaulet H, Stennard FA, Wise N, Schaft D, Wolstein O, Furtado MB, Shiratori H, Chien KR, Hamada H, Black BL, Saga Y, Robertson EJ, Buckingham ME, Harvey RP, An Nkx2-5/Bmp2/Smad1 negative feedback loop controls heart progenitor specification and proliferation, Cell 128 (5) (2007) 947–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Xie L, Hoffmann AD, Burnicka-Turek O, Friedland-Little JM, Zhang K, Moskowitz IP, Tbx5-hedgehog molecular networks are essential in the second heart field for atrial septation, Dev. Cell 23 (2) (2012) 280–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Watanabe Y, Zaffran S, Kuroiwa A, Higuchi H, Ogura T, Harvey RP, Kelly RG, Buckingham M, Fibroblast growth factor 10 gene regulation in the second heart field by Tbx1, Nkx2-5, and Islet1 reveals a genetic switch for down-regulation in the myocardium, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109 (45) (2012) 18273–18280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Gibb N, Lazic S, Yuan X, Deshwar AR, Leslie M, Wilson MD, Scott IC, Hey2 regulates the size of the cardiac progenitor pool during vertebrate heart development, Development 145 (22) (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Murry CE, Keller G, Differentiation of embryonic stem cells to clinically relevant populations: lessons from embryonic development, Cell 132 (4) (2008) 661–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Meganathan K, Sotiriadou I, Natarajan K, Hescheler J, Sachinidis A, Signaling molecules, transcription growth factors and other regulators revealed from in-vivo and in-vitro models for the regulation of cardiac development, Int. J. Cardiol 183 (2015) 117–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].van den Berg CW, Okawa S, Chuva de Sousa Lopes SM, van Iperen L, Passier R, Braam SR, Tertoolen LG, del Sol A, Davis RP, Mummery CL, Transcriptome of human foetal heart compared with cardiomyocytes from pluripotent stem cells, Development 142 (18) (2015) 3231–3238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Lee JH, Protze SI, Laksman Z, Backx PH, Keller GM, Human pluripotent stem cell-derived atrial and ventricular cardiomyocytes develop from distinct mesoderm populations, Cell Stem Cell 21 (2) (2017) 179–194 e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Yoshida Y, Yamanaka S, Induced pluripotent stem cells 10 years later: for cardiac applications, Circ. Res 120 (12) (2017) 1958–1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Ieda M, Fu JD, Delgado-Olguin P, Vedantham V, Hayashi Y, Bruneau BG, Srivastava D, Direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into functional cardiomyocytes by defined factors, Cell 142 (3) (2010) 375–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Jayawardena TM, Egemnazarov B, Finch EA, Zhang L, Payne JA, Pandya K, Zhang Z, Rosenberg P, Mirotsou M, Dzau VJ, MicroRNA-mediated in vitro and in vivo direct reprogramming of cardiac fibroblasts to cardiomyocytes, Circ. Res 110 (11) (2012) 1465–1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Qian L, Huang Y, Spencer CI, Foley A, Vedantham V, Liu L, Conway SJ, Fu JD, Srivastava D, In vivo reprogramming of murine cardiac fibroblasts into induced cardiomyocytes, Nature 485 (7400) (2012) 593–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Song K, Nam YJ, Luo X, Qi X, Tan W, Huang GN, Acharya A, Smith CL, Tallquist MD, Neilson EG, Hill JA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN, Heart repair by reprogramming non-myocytes with cardiac transcription factors, Nature 485 (7400) (2012) 599–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Liu Z, Wang L, Welch JD, Ma H, Zhou Y, Vaseghi HR, Yu S, Wall JB, Alimohamadi S, Zheng M, Yin C, Shen W, Prins JF, Liu J, Qian L, Single-cell transcriptomics reconstructs fate conversion from fibroblast to cardiomyocyte, Nature 551 (7678) (2017) 100–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Kuppusamy KT, Jones DC, Sperber H, Madan A, Fischer KA, Rodriguez ML, Pabon L, Zhu WZ, Tulloch NL, Yang X, Sniadecki NJ, Laflamme MA, Ruzzo WL, Murry CE, Ruohola-Baker H, Let-7 family of microRNA is required for maturation and adult-like metabolism in stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112 (21) (2015) E2785–E2794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Dubois NC, Craft AM, Sharma P, Elliott DA, Stanley EG, Elefanty AG, Gramolini A, Keller G, SIRPA is a specific cell-surface marker for isolating cardiomyocytes derived from human pluripotent stem cells, Nat. Biotechnol 29 (11) (2011) 1011–1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Prinz RD, Willis CM, van Kuppevelt TH, Klüppel M, Biphasic role of chondroitin sulfate in cardiac differentiation of embryonic stem cells through inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, PLoS One 9 (3) (2014) 92381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Birket MJ, Ribeiro MC, Verkerk AO, Ward D, Leitoguinho AR, den Hartogh SC, Orlova VV, Devalla HD, Schwach V, Bellin M, Passier R, Mummery CL, Expansion and patterning of cardiovascular progenitors derived from human pluripotent stem cells, Nat. Biotechnol 33 (9) (2015) 970–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Rao J, Pfeiffer MJ, Frank S, Adachi K, Piccini I, Quaranta R, Araúzo-Bravo M, Schwarz J, Schade D, Leidel S, Schöler HR, Seebohm G, Greber B, Stepwise clearance of repressive roadblocks drives cardiac induction in human ESCs, Cell Stem Cell 18 (4) (2016) 554–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Shen N, Knopf A, Westendorf C, Kraushaar U, Riedl J, Bauer H, Pöschel S, Layland SL, Holeiter M, Knolle S, Brauchle E, Nsair A, Hinderer S, Schenke-Layland K, Steps toward maturation of embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes by defined physical signals, Stem Cell Rep. 9 (1) (2017) 122–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Ronaldson-Bouchard K, Ma SP, Yeager K, Chen T, Song L, Sirabella D, Morikawa K, Teles D, Yazawa M, Vunjak-Novakovic G, Advanced maturation of human cardiac tissue grown from pluripotent stem cells, Nature 556 (7700) (2018) 239–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Beltrami AP, Barlucchi L, Torella D, Baker M, Limana F, Chimenti S, Kasahara H, Rota M, Musso E, Urbanek K, Leri A, Kajstura J, Nadal-Ginard B, Anversa P, Adult cardiac stem cells are multipotent and support myocardial regeneration, Cell 114 (6) (2003) 763–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Bollini S, Smart N, Riley PR, Resident cardiac progenitor cells: at the heart of regeneration, J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol 50 (2) (2011) 296–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Oh H, Bradfute SB, Gallardo TD, Nakamura T, Gaussin V, Mishina Y, Pocius J, Michael LH, Behringer RR, Garry DJ, Entman ML, Schneider MD, Cardiac progenitor cells from adult myocardium: homing, differentiation, and fusion after infarction, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100 (21) (2003) 12313–12318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Murry CE, Soonpaa MH, Reinecke H, Nakajima H, Nakajima HO, Rubart M, Pasumarthi KB, Virag JI, Bartelmez SH, Poppa V, Bradford G, Dowell JD, Williams DA, Field LJ, Haematopoietic stem cells do not transdifferentiate into cardiac myocytes in myocardial infarcts, Nature 428 (6983) (2004) 664–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Balsam LB, Wagers AJ, Christensen JL, Kofidis T, Weissman IL, Robbins RC, Haematopoietic stem cells adopt mature haematopoietic fates in ischaemic myocardium, Nature 428 (6983) (2004) 668–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Nygren JM, Jovinge S, Breitbach M, Säwén P, Röll W, Hescheler J, Taneera J, Fleischmann BK, Jacobsen SE, Bone marrow-derived hematopoietic cells generate cardiomyocytes at a low frequency through cell fusion, but not transdifferentiation, Nat. Med 10 (5) (2004) 494–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Garbern JC, Lee RT, Cardiac stem cell therapy and the promise of heart regeneration, Cell Stem Cell 12 (6) (2013) 689–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Senyo SE, Steinhauser ML, Pizzimenti CL, Yang VK, Cai L, Wang M, Wu TD, Guerquin-Kern JL, Lechene CP, Lee RT, Mammalian heart renewal by pre-existing cardiomyocytes, Nature 493 (7432) (2013) 433–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Zhou B, Wu SM, Reassessment of c-Kit in cardiac cells: a complex interplay between expression, fate, and function, Circ. Res 123 (1) (2018) 9–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Maliken BD, Molkentin JD, Undeniable evidence that the adult mammalian heart lacks an endogenous regenerative stem cell, Circulation 138 (8) (2018) 806–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Galdos FX, Guo Y, Paige SL, VanDusen NJ, Wu SM, Pu WT, Cardiac regeneration: lessons from development, Circ. Res 120 (6) (2017) 941–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Brand T, Heart development: molecular insights into cardiac specification and early morphogenesis, Dev. Biol 258 (1) (2003) 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Kimelman D, Mesoderm induction: from caps to chips, Nat. Rev. Genet 7 (5) (2006) 360–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Winnier G, Blessing M, Labosky PA, Hogan BL, Bone morphogenetic protein-4 is required for mesoderm formation and patterning in the mouse, Genes Dev. 9 (17) (1995) 2105–2116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Lu CC, Brennan J, Robertson EJ, From fertilization to gastrulation: axis formation in the mouse embryo, Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev 11 (4) (2001) 384–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Tam PP, Loebel DA, Gene function in mouse embryogenesis: get set for gastrulation, Nat. Rev. Genet 8 (5) (2007) 368–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Tam PP, Parameswaran M, Kinder SJ, Weinberger RP, The allocation of epiblast cells to the embryonic heart and other mesodermal lineages: the role of ingression and tissue movement during gastrulation, Development 124 (9) (1997) 1631–1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Lawson KA, Meneses JJ, Pedersen RA, Clonal analysis of epiblast fate during germ layer formation in the mouse embryo, Development 113 (3) (1991) 891–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Parameswaran M, Tam PP, Regionalisation of cell fate and morphogenetic movement of the mesoderm during mouse gastrulation, Dev. Genet 17 (1) (1995) 16–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Sun X, Meyers EN, Lewandoski M, Martin GR, Targeted disruption of Fgf8 causes failure of cell migration in the gastrulating mouse embryo, Genes Dev. 13 (14) (1999) 1834–1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Ciruna B, Rossant J, FGF signaling regulates mesoderm cell fate specification and morphogenetic movement at the primitive streak, Dev. Cell 1 (1) (2001) 37–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Liu P, Wakamiya M, Shea MJ, Albrecht U, Behringer RR, Bradley A, Requirement for Wnt3 in vertebrate axis formation, Nat. Genet 22 (4) (1999) 361–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Beppu H, Kawabata M, Hamamoto T, Chytil A, Minowa O, Noda T, Miyazono K, BMP type II receptor is required for gastrulation and early development of mouse embryos, Dev. Biol 221 (1) (2000) 249–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Haegel H, Larue L, Ohsugi M, Fedorov L, Herrenknecht K, Kemler R, Lack of beta-catenin affects mouse development at gastrulation, Development 121 (11) (1995) 3529–3537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Ueno S, Weidinger G, Osugi T, Kohn AD, Golob JL, Pabon L, Reinecke H, Moon RT, Murry CE, Biphasic role for Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in cardiac specification in zebrafish and embryonic stem cells, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104 (23) (2007) 9685–9690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Naito AT, Shiojima I, Akazawa H, Hidaka K, Morisaki T, Kikuchi A, Komuro I, Developmental stage-specific biphasic roles of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in cardiomyogenesis and hematopoiesis, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103 (52) (2006) 19812–19817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Burridge PW, Matsa E, Shukla P, Lin ZC, Churko JM, Ebert AD, Lan F, Diecke S, Huber B, Mordwinkin NM, Plews JR, Abilez OJ, Cui B, Gold JD, Wu JC, Chemically defined generation of human cardiomyocytes, Nat. Methods 11 (8) (2014) 855–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Dohn TE, Waxman JS, Distinct phases of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling direct cardiomyocyte formation in zebrafish, Dev. Biol 361 (2) (2012) 364–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Lei I, Tian S, Chen V, Zhao Y, Wang Z, SWI/SNF component BAF250a coordinates OCT4 and WNT signaling pathway to control cardiac lineage differentiation, Front. Cell Dev. Biol 7 (2019) 358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Hota SK, Johnson JR, Verschueren E, Thomas R, Blotnick AM, Zhu Y, Sun X, Pennacchio LA, Krogan NJ, Bruneau BG, Dynamic BAF chromatin remodeling complex subunit inclusion promotes temporally distinct gene expression programs in cardiogenesis, Development 146 (2019) 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Tanaka S, Kunath T, Hadjantonakis AK, Nagy A, Rossant J, Promotion of trophoblast stem cell proliferation by FGF4, Science 282 (5396) (1998) 2072–2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Ciruna B, Rossant J, FGF signaling regulates mesoderm cell fate specification and morphogenetic movement at the primitive streak, Dev. Cell 1 (1) (2001) 37–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Sun X, Meyers EN, Lewandoski M, Martin GR, Targeted disruption of Fgf8 causes failure of cell migration in the gastrulating mouse embryo, Genes Dev. 13 (14) (1999) 1834–1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Yang X, Dormann D, Münsterberg AE, Weijer CJ, Cell movement patterns during gastrulation in the chick are controlled by chemotaxis mediated by positive and negative FGF4 and FGF8, Dev. Cell 3 (3) (2002) 425–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Guzzetta A, Koska M, Rowton M, Sullivan KR, Jacobs-Li J, Kweon J, Hidalgo H, Eckart H, Hoffmann AD, Back R, Lozano S, Moon AM, Basu A, Bressan M, Pott S, Moskowitz IP, Hedgehog-FGF signaling axis patterns anterior mesoderm during gastrulation, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117 (27) (2020) 15712–15723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Lescroart F, Wang X, Lin X, Swedlund B, Gargouri S, Sànchez-Dànes A, Moignard V, Dubois C, Paulissen C, Kinston S, Göttgens B, Blanpain C, Defining the earliest step of cardiovascular lineage segregation by single-cell RNA-seq, Science 359 (6380) (2018) 1177–1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Lescroart F, Chabab S, Lin X, Rulands S, Paulissen C, Rodolosse A, Auer H, Achouri Y, Dubois C, Bondue A, Simons BD, Blanpain C, Early lineage restriction in temporally distinct populations of Mesp1 progenitors during mammalian heart development, Nat. Cell Biol 16 (9) (2014) 829–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Bardot E, Calderon D, Santoriello F, Han S, Cheung K, Jadhav B, Burtscher I, Artap S, Jain R, Epstein J, Lickert H, Gouon-Evans V, Sharp AJ, Dubois NC, Foxa2 identifies a cardiac progenitor population with ventricular differentiation potential, Nat. Commun 8 (2017) 14428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Später D, Abramczuk MK, Buac K, Zangi L, Stachel MW, Clarke J, Sahara M, Ludwig A, Chien KR, A HCN4+ cardiomyogenic progenitor derived from the first heart field and human pluripotent stem cells, Nat. Cell Biol 15 (9) (2013) 1098–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Brown K, Doss MX, Legros S, Artus J, Hadjantonakis AK, Foley AC, eXtraembryonic ENdoderm (XEN) stem cells produce factors that activate heart formation, PLoS One 5 (10) (2010) 13446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Liu W, Brown K, Legros S, Foley AC, Nodal mutant eXtraembryonic ENdoderm (XEN) stem cells upregulate markers for the anterior visceral endoderm and impact the timing of cardiac differentiation in mouse embryoid bodies, Biol. Open 1 (3) (2012) 208–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Niakan KK, Schrode N, Cho LT, Hadjantonakis AK, Derivation of extraembryonic endoderm stem (XEN) cells from mouse embryos and embryonic stem cells, Nat. Protoc 8 (6) (2013) 1028–1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Yuasa S, Itabashi Y, Koshimizu U, Tanaka T, Sugimura K, Kinoshita M, Hattori D, Fukami S, Shimazaki T, Ogawa S, Okano H, Fukuda K, Transient inhibition of BMP signaling by Noggin induces cardiomyocyte differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells, Nat. Biotechnol 23 (5) (2005) 607–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Perea-Gomez A, Vella FD, Shawlot W, Oulad-Abdelghani M, Chazaud C, Meno C, Pfister V, Chen L, Robertson E, Hamada H, Behringer RR, Ang SL, Nodal antagonists in the anterior visceral endoderm prevent the formation of multiple primitive streaks, Dev. Cell 3 (5) (2002) 745–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Bachiller D, Klingensmith J, Kemp C, Belo JA, Anderson RM, May SR, McMahon JA, McMahon AP, Harland RM, Rossant J, De Robertis EM, The organizer factors Chordin and Noggin are required for mouse forebrain development, Nature 403 (6770) (2000) 658–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Piccolo S, Agius E, Leyns L, Bhattacharyya S, Grunz H, Bouwmeester T, De Robertis EM, The head inducer Cerberus is a multifunctional antagonist of Nodal, BMP and Wnt signals, Nature 397 (6721) (1999) 707–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Biben C, Stanley E, Fabri L, Kotecha S, Rhinn M, Drinkwater C, Lah M, Wang CC, Nash A, Hilton D, Ang SL, Mohun T, Harvey RP, Murine cerberus homologue mCer-1: a candidate anterior patterning molecule, Dev. Biol 194 (2) (1998) 135–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Bafico A, Liu G, Yaniv A, Gazit A, Aaronson SA, Novel mechanism of Wnt signalling inhibition mediated by Dickkopf-1 interaction with LRP6/Arrow, Nat. Cell Biol 3 (7) (2001) 683–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Hoshino H, Shioi G, Aizawa S, AVE protein expression and visceral endoderm cell behavior during anterior-posterior axis formation in mouse embryos: asymmetry in OTX2 and DKK1 expression, Dev. Biol 402 (2) (2015) 175–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Boulet AM, Capecchi MR, Signaling by FGF4 and FGF8 is required for axial elongation of the mouse embryo, Dev. Biol 371 (2) (2012) 235–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Andersen P, Tampakakis E, Jimenez DV, Kannan S, Miyamoto M, Shin HK, Saberi A, Murphy S, Sulistio E, Chelko SP, Kwon C, Precardiac organoids form two heart fields via Bmp/Wnt signaling, Nat. Commun 9 (1) (2018) 3140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Duong TB, Holowiecki A, Waxman JS, Retinoic acid signaling restricts the size of the first heart field within the anterior lateral plate mesoderm, Dev. Biol 473 (2021) 119–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Olson EN, Srivastava D, Molecular pathways controlling heart development, Science 272 (5262) (1996) 671–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Bodmer R, The gene tinman is required for specification of the heart and visceral muscles in Drosophila, Development 118 (3) (1993) 719–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Biben C, Weber R, Kesteven S, Stanley E, McDonald L, Elliott DA, Barnett L, Köentgen F, Robb L, Feneley M, Harvey RP, Cardiac septal and valvular dysmorphogenesis in mice heterozygous for mutations in the homeobox gene Nkx2-5, Circ. Res 87 (10) (2000) 888–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Granados-Riveron JT, Pope M, Bu’lock FA, Thornborough C, Eason J, Setchfield G, Ketley A, Kirk EP, Fatkin D, Feneley MP, Harvey RP, Brook JD, Combined mutation screening of NKX2-5, GATA4, and TBX5 in congenital heart disease: multiple heterozygosity and novel mutations, Congenit. Heart Dis 7 (2) (2012) 151–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Kuo CT, Morrisey EE, Anandappa R, Sigrist K, Lu MM, Parmacek MS, Soudais C, Leiden JM, GATA4 transcription factor is required for ventral morphogenesis and heart tube formation, Genes Dev. 11 (8) (1997) 1048–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Molkentin JD, Lin Q, Duncan SA, Olson EN, Requirement of the transcription factor GATA4 for heart tube formation and ventral morphogenesis, Genes Dev. 11 (8) (1997) 1061–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Bruneau BG, Nemer G, Schmitt JP, Charron F, Robitaille L, Caron S, Conner DA, Gessler M, Nemer M, Seidman CE, Seidman JG, A murine model of Holt-Oram syndrome defines roles of the T-box transcription factor Tbx5 in cardiogenesis and disease, Cell 106 (6) (2001) 709–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]