Abstract

Upfront resection is becoming a rarer indication for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, as biologic behavior and natural history of the disease has boosted indications for neoadjuvant treatments. Jaundice, gastric outlet obstruction and acute cholecystitis can frequently complicate this window of opportunity, resulting in potentially deleterious chemotherapy discontinuation, whose resumption relies on effective, prompt and long-lasting management of these complications. Although therapeutic endoscopic ultrasound (t-EUS) can potentially offer some advantages over comparators, its use in potentially resectable patients is primal and has unfairly been restricted for fear of potential technical difficulties during subsequent surgery. This is a narrative review of available evidence regarding EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy, gastrojejunostomy and gallbladder drainage in the bridge-to-surgery scenario. Proof-of-concept evidence suggests no influence of t-EUS procedures on outcomes of eventual subsequent surgery. Moreover, the very high efficacy-invasiveness ratio over comparators in managing pancreatic cancer-related symptoms or complications can provide a powerful weapon against chemotherapy discontinuation, potentially resulting in higher subsequent resectability. Available evidence is discussed in this short paper, together with technical notes that might be useful for endoscopists and surgeons operating in this scenario. No published evidence supports restricting t-EUS in potential surgical candidates, especially in the setting of pancreatic cancer patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Bridge-to-surgery t-EUS deserves further prospective evaluation.

Keywords: Endosonography, Gastrojejunostomy, Choledochoduodenostomy, Gallbladder drainage, Pancreatic cancer, Pancreatic surgery

Core Tip: Despite the increase of a subset of patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy, therapeutic endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has been unfairly restricted in potentially resectable patients. However, to date, no evidence suggests any influence of therapeutic EUS procedures on difficulty or outcomes of eventual subsequent surgery. Conversely, proof-of-concept papers have described uncomplicated surgery following EUS-guided gallbladder drainage, choledochoduodenostomy and gastrojejunostomy. Available evidence and technical notes are collected in this review. Due to the very high efficacy-invasiveness ratio of therapeutic EUS procedures, potentially resulting in less chemotherapy discontinuation, we believe that their use should not be restricted in the bridge-to-surgery scenario while implementing its prospective evaluation.

INTRODUCTION

Jaundice, gastric outlet obstruction and acute cholecystitis (AC) can frequently complicate the clinical course of patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC)[1]. Rapid, effective and long-lasting management of these events remains crucial to allow chemotherapy initiation or continuation. Traditional endoscopic or percutaneous palliation of these events may carry some limitations: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) fails in up to 5%-10% of cases. Duodenal stenting is burdened by frequent symptoms recurrence. Percutaneous cholecystostomy (PT-GBD) is prone to tube dislodgement and cholecystitis recurrence[2-4]. Therapeutic EUS (t-EUS) is showing increasing potential in overcoming some of these limitations. However, EUS-guided procedures have been conventionally restricted to inoperable patients, for fear of interference with eventual surgery.

In an era in which upfront resection of PDAC is decreasing in favor of a more frequent use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, this prudential limitation might result in a significant subset of patients being excluded from the potential advantages of t-EUS[5]. The aim of this narrative review was to discuss available evidence on outcomes of t-EUS in the bridge-to-surgery scenario.

METHODS

A literature search was performed regarding EUS-guided biliary drainage, EUS-guided gastrojejunostomy (EUS-GJ) and EUS-guided gallbladder drainage (EUS-GBD) in the bridge-to-surgery scenario up to July 2020. Available evidence was discussed in this narrative review, together with technical considerations and suggestions useful for endoscopists and surgeons operating in this setting. No original data are presented in the manuscript, and therefore Institutional Review Board approval was not required. Anonymized pictures are included from patients who have signed a specific written informed consent.

CLINICAL SCENARIO

In the combined treatment plan of PDAC, surgery is theoretically the only curative option, but only approximate 20% of patients are surgical candidates at diagnosis, the remaining being metastatic or locally unresectable[6].

Even in resectable disease, increasing knowledge of PDAC biology has expanded criteria for neoadjuvant chemotherapy to control potential micrometastases and select the best surgical candidates[5,7,8]. Therefore, half of PDAC patients, with resectable, borderline resectable or locally advanced tumor, will start a chemo (radio) therapeutic regimen, being eventually considered for subsequent surgery in case of stable disease or partial response. This “window of opportunity” where cancer behavior is ascertained can last 6 mo or more. During this time symptoms need to remain palliated through minimally invasive procedures, providing long-term efficacy with low risk of dysfunction/ recurrence, to optimize tolerance of oncological treatments.

POTENTIAL ADVANTAGES OF THERAPEUTIC EUS PROCEDURES OVER ALTERNATIVES

EUS is gaining ground in palliation of cancer symptoms, where the least possible invasiveness allows non-delayed oncological treatments, potentially leading to increased survival and prolonged time to quality of life deterioration. Biliary drainage might be required in more than half of patients with PDAC[9]. The gold standard approach (ERCP) might fail in up to 5%-10% of cases, as the papilla might be unreachable or cannulation may fail[2].

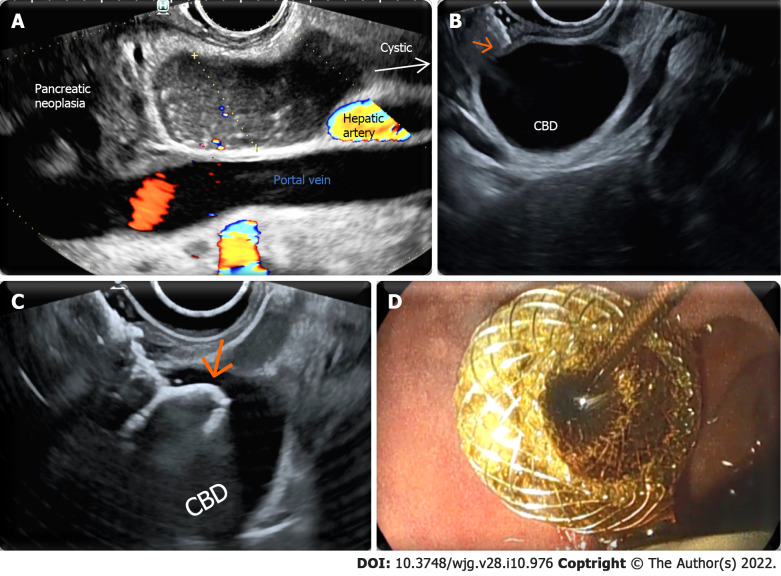

EUS-guided biliary drainage has an established role when ERCP fails, avoiding morbidity of percutaneous drainage[10]. Electrocautery-enhanced lumen apposing metal stents have improved simplicity and safety of EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy (EUS-CD; Figure 1) to such an extent that this procedure is being proposed as an upfront alternative to ERCP in distal malignant obstruction, with the potential to reduce the rate of post-ERCP acute pancreatitis[11,12].

Figure 1.

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided choledochoduodenostomy. A: Endosonographic identification of a window for endoscopic ultrasound-guided choledochoduodenostomy in a potentially resectable patient. The common bile duct (CBD) is evaluated from liver hilum to the neoplasia. A spot without intervening vessels is chosen as close as possible to the neoplasia; the caliber of the CBD is evaluated in the direction of the operative channel of the endoscope (yellow dotted line); B: The tip (arrow) of the electrocautery-enhanced lumen apposing metal stent is visibly in touch with the duodenal wall adjacent to a dilated CBD; C: The electrocautery-enhanced lumen apposing metal stent has passed through duodenal and biliary walls, and the distal flange (arrow) has been released inside the CBD; D: The proximal flange has been released inside the bulb with successful drainage of bile flow at the end of the procedure.

Although surgical gastrojejunostomy has shown better long-term results for gastric outlet obstruction, endoscopic placement of duodenal self-expandable metal stents is conventionally used as a first-line treatment[3]. This minimally invasive technique harbors some limitations, as it may provide suboptimal relief with high risk of gastric outlet obstruction recurrence[6].

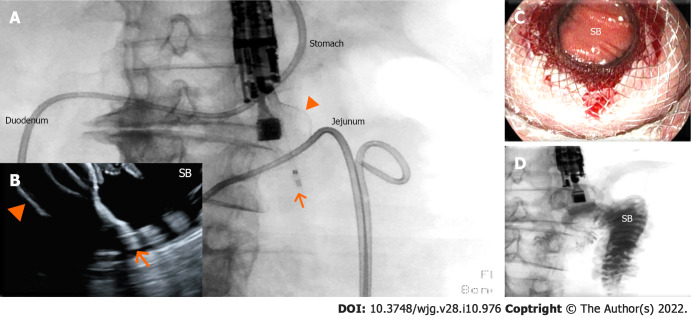

EUS-GJ is currently investigated as an alternative to both enteral stenting and surgical bypass. Placement of an electrocautery-enhanced lumen apposing metal stent between the stomach and proximal jejunum results in a large (2 cm) surgical-like anastomosis at a significant distance from the tumor. This minimally invasive procedure (Figure 2) may avoid both adverse events of surgery and the risk of primary failure, recurrence and re-interventions following enteral stenting[13-15].

Figure 2.

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastrojejunostomy. A and B: The small bowel has been distended with saline infusion through a nasojejunal tube. The dilated jejunal loop has been identified through the gastric wall by endosonography and has been accessed through a 20 mm enhanced lumen apposing metal stent (arrow: tip of the catheter; arrowhead: distal flange); under fluoroscopic (A) and endosonographic (B) guidance, demonstrating the opening of the distal flange (arrowhead) inside the small bowel (SB); C: The proximal flange of the electrocautery-enhanced lumen apposing metal stent has been released and dilated, and the SB can be visualized through the lumen apposing metal stent; D: Contrast injected through the nasojejunal tube can be aspirated through the lumen apposing metal stent inside the stomach.

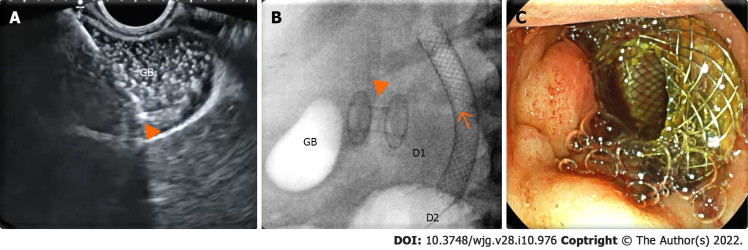

Even if rarer, AC can also complicate the clinical history of PDAC patients, due to a neoplastic infiltration of the cystic duct, eventually worsened by other palliative maneuvers, such as the placement of a self-expandable biliary metal stent[16-18]. When surgical cholecystectomy is undesirable or unfeasible, EUS-GBD (Figure 3) has demonstrated its advantages over PT-GBD, resulting in equal technical success, paired with reduced 30-d and 1-year risk of adverse events, reintervention rates and AC recurrence[4]. Moreover, the large-diameter fistula between the gallbladder and the gastrointestinal tract allows for subsequent endoscopic clearance of gallstones, potentially offering a definitive solution for AC[19]. All these advantages might be even more valuable in the setting of patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy since a long-lasting, effective, minimally invasive palliation of cancer symptoms might result in reduced chemotherapy discontinuation and potentially to more frequent resectability.

Figure 3.

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder drainage. A: Endosonographic view of the delivery system (arrowhead) of the enhanced lumen apposing metal stent inside a distended gallbladder (GB) full of sludge; B: Radioscopic view of the lumen apposing metal stent (arrowhead) released between the gallbladder and duodenal bulb [D1; biliary stent (arrow) released in the second duodenal portion (D2)]; C: Endoscopic view of the proximal flange of the lumen apposing metal stent inside the duodenal bulb.

EXISTING EVIDENCE ON SURGERY AFTER THERAPEUTIC EUS

To date there is limited experience on surgery following t-EUS, which is confined to cholecystectomy after EUS-GBD and a small series of pancreaticoduodenectomy after EUS-CD. As for cholecystectomy after EUS-GBD, a retrospective multicentric case-control study analyzed outcomes of subsequent cholecystectomy in 34 patients previously undergoing EUS-GBD with LAMS vs PT-GBD[20]. The study showed no influence of previous drainage modality in technical success, rate of conversion to open laparotomy or post-surgical adverse events, further showing a reduced operative time in the EUS-GBD cohort and a significantly higher number of interval procedures between PT-GBD and cholecystectomy due to plastic catheter maintenance or dislodgement.

Fabbri et al[21] described 5 patients undergoing pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy after EUS-CD with 100% technical success and no biliary/duodenal fistula. In a recent study, Gaujoux et al[22] described 21 patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy after EUS-CD with electrocautery-enhanced lumen apposing metal stents: all surgeries were successful, without any postoperative biliary fistula or stricture or tumor recurrence at the hepaticojejunostomy site.

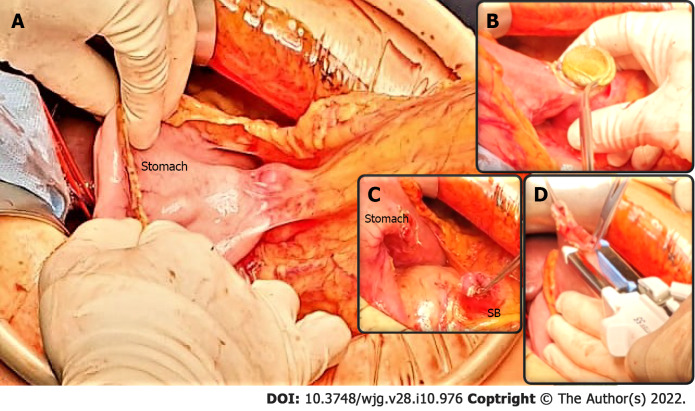

We recently published the first pancreaticoduodenectomy following EUS-guided double bypass. Surgical identification and disconnection of EUS-GJ was easy and fast and subsequent hepaticojejunostomy and gastrojejunostomy uncomplicated[23].

ENDOSCOPIC TRICKS FOR EUS-GUIDED PROCEDURES IN POTENTIALLY RESECTABLE PATIENTS

Endoscopists involved in t-EUS may wonder whether the technical approach to EUS-CD should change when treating potentially resectable patients. In our opinion, two principles must be kept in mind in this specific setting: EUS-CD should be performed: (1) Through the bulb; and (2) As far away from the hilum as possible. Although no evidence exists on the impact of these technical variables, a “distal” EUS-CD will allow more space for bile duct transection and hepaticojejunostomy (Figure 1A). Regarding EUS-CD location, a transbulbar (instead of transgastric) window nullifies the theoretical risk of tumor seeding since the bulb falls within surgical resection margins.

As for EUS-GJ, theoretical constraints are broader than the millimetric evaluation during EUS-CD. The EUS-GJ site must be kept as close as possible to the ligament of Treitz, in the first jejunal loop, to sacrifice a limited amount of jejunum during reconstruction. In our experience, this is obtained by careful evaluation of fluoroscopy during nasojejunal tube insertion. As previously described, we believe that puncture of the colon or too distant a loop can be avoided relying on EUS-guided transgastric visualization of the nasojejunal tube and fluid flow inside the jejunum[24]. For all these reasons, we never place the tip of the nasojejunal tube too far from the ligament of Treitz. Finally, in case both procedures are required, we have no concern in performing them during the same sedation, but we believe that sequence matters[24]. EUS-GJ must be performed first, as an effective gastroenteric conduit is fundamental for successful transluminal biliary drainage. Conversely, if EUS-GJ proves technically unfeasible, a correctly placed EUS-CD may be rendered dysfunctional, resulting in subsequent cholangitis[25].

As for EUS-GBD with LAMS, one important consideration might regard the site for drainage. If EUS-GBD is performed in a patient who is potentially a candidate to a pancreaticoduodenectomy, a transduodenal route for drainage makes the fistula lie within the resection margins of subsequent surgery. In all other kinds of surgeries (including simple cholecystectomy), a surgical revision of a cholecystogastrostomy is technically simpler than a cholecystoduodenostomy, and therefore the endoscopist should predilect a transgastric route when feasible. Moreover, all the attempts to reduce LAMS-related trauma must be pursued to avoid additional inflammatory reactions that might complicate surgery. We suggest the systematic placement of a short coaxial double-pigtail plastic stent inside the LAMS to avoid food impaction and to protect the contralateral wall from mechanical trauma, a lesson learnt from the management of peripancreatic fluid collections[26]. Furthermore, as described also in the setting of peripancreatic fluid collections, a longer stent indwelling might predispose to a higher risk of adverse events, and therefore we propose a systematic removal of the LAMS within 4 wk in case surgery must be postponed beyond this interval[27].

SURGICAL TRICKS FOR PANCREATICODUODENECTOMY FOLLOWING EUS-GUIDED DOUBLE BYPASS

T-EUS is not a contraindication for PD. Usually the GJ anastomosis is performed between the posterior gastric wall and the fourth duodenal portion/first jejunal loop. As the first part of the resection we suggest identifying the EUS-GJ anastomosis (Figure 4), to open it with diathermic coagulation and to remove the LAMS. At this stage, the gastric wall defect can be closed using staplers, whereas small bowel will be resected as part of the pancreaticoduodenectomy. With this technique, a classic pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy is achievable. As a second stage, we suggest performing a retrograde cholecystectomy in order to reach the common bile duct at the liver hilum. At this point, a proper lymphadenectomy of the liver hilum is performed, and the hepatic artery, portal vein and common bile duct are isolated and encircled with vessel loops. The common bile duct should be cut above the cystic duct’s confluence, and EUS-CD will therefore remain within resection margins and removed simultaneously.

Figure 4.

Pancreaticoduodenectomy following endoscopic ultrasound-guided double bypass. A: The endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastrojejunostomy site is easily identified and a stable gastrojejunal anastomosis is visible (underlined by blue curves) between the stomach and the small bowel (SB); B-C: The endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastrojejunostomy site is opened with diathermic coagulation, the lumen apposing metal stent is removed (B), and the anastomosis cut (C); D: The SB is prepared for gastroenteric anastomosis, while the gastric defect will be closed using staplers. A classic pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy is achievable.

In the case of former EUS-GBD, the approach will depend on the site of drainage and the type of surgery. If the patient is a candidate to a pancreaticoduodenectomy and the gallbladder was drained through the duodenum, the fistula remains within resection margins. In the case that the gallbladder was drained transgastric, the fistula can be transected as described for EUS-GJ. The gastric wall defect can be closed either using staplers or using suture with eventual omental protection.

CONCLUSION

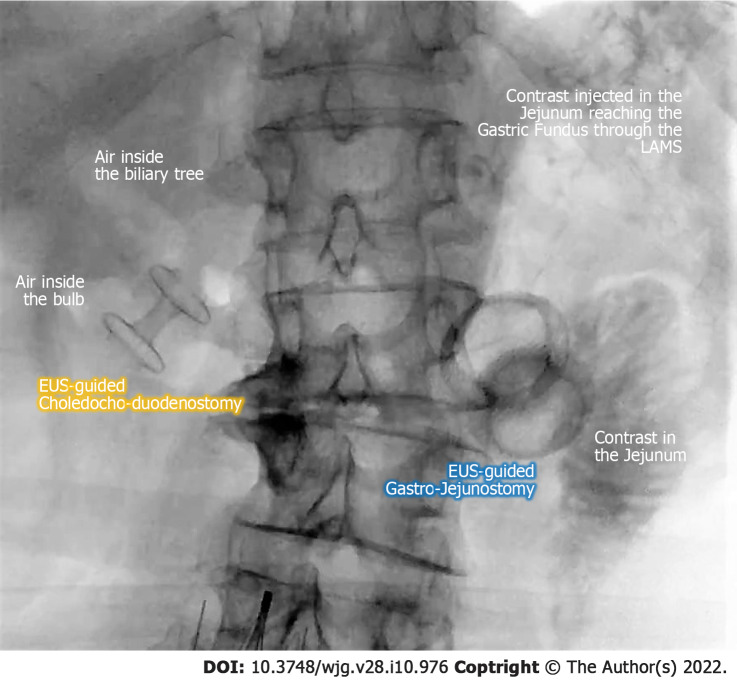

Upfront resection is becoming a rarer indication in PDAC patients, as biologic behavior and natural history of the disease has boosted indications for neoadjuvant treatment. An effective chemotherapy, capable of carrying the patient to eventual surgery, greatly depends on an effective and long-lasting palliation of disease-related gastrointestinal symptoms and complications. While conventional endoscopic/percutaneous palliation carries intrinsic disadvantages, t-EUS may overcome these limitations, without apparently increasing technical difficulty or complicating subsequent surgery. For all these reasons we believe that t-EUS should not be restricted in the bridge-to-surgery scenario while deserving further prospective evaluation in this setting (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Fluoroscopic final image of an endoscopic ultrasound-guided double bypass with choledochobulbostomy and gastrojejunostomy. EUS: Endoscopic ultrasound; LAMS: Lumen apposing metal stent.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: Michiel Bronswijk has consultancy agreements with Prion Medical and Taewoong. Schalk van der Merwe holds the Cook Medical and Boston Scientific chair in Interventional Endoscopy and holds consultancy agreements with Cook Medical, Pentax and Olympus. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest relevant for this article.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: August 20, 2021

First decision: October 2, 2021

Article in press: February 15, 2022

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Li CG, Yoshizawa T S-Editor: Wu YXJ L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wu YXJ

Contributor Information

Giuseppe Vanella, Pancreatobiliary Endoscopy and EUS Division, Pancreas Translational & Clinical Research Center, IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Vita-Salute San Raffaele University, Milan 20132, Italy.

Domenico Tamburrino, Pancreatic Surgery Unit, Pancreas Translational & Clinical Research Center, IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Vita-Salute San Raffaele University, Milan 20132, Italy.

Gabriele Capurso, Pancreatobiliary Endoscopy and EUS Division, Pancreas Translational & Clinical Research Center, IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Vita-Salute San Raffaele University, Milan 20132, Italy.

Michiel Bronswijk, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University Hospital Gasthuisberg, University of Leuven, Leuven 3000, Belgium; Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Imelda Hospital, Bonheiden 2820, Belgium.

Michele Reni, Department of Medical Oncology, Pancreas Translational & Clinical Research Center, IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan 20132, Italy.

Giuseppe Dell'Anna, Pancreatobiliary Endoscopy and EUS Division, Pancreas Translational & Clinical Research Center, IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Vita-Salute San Raffaele University, Milan 20132, Italy.

Stefano Crippa, Pancreatic Surgery Unit, Pancreas Translational & Clinical Research Center, IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Vita-Salute San Raffaele University, Milan 20132, Italy.

Schalk Van der Merwe, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University Hospital Gasthuisberg, University of Leuven, Leuven 3000, Belgium.

Massimo Falconi, Pancreatic Surgery Unit, Pancreas Translational & Clinical Research Center, IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Vita-Salute San Raffaele University, Milan 20132, Italy.

Paolo Giorgio Arcidiacono, Pancreatobiliary Endoscopy and EUS Division, Pancreas Translational & Clinical Research Center, IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Vita-Salute San Raffaele University, Milan 20132, Italy. arcidiacono.paologiorgio@hsr.it.

References

- 1.National Health Service (NHS) Symptoms of pancreatic cancer. Reviewed May 2020, [cited 29 November 2020]. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/pancreatic-cancer/symptoms/

- 2.Olsson G, Enochsson L, Swahn F, Andersson B. Antibiotic prophylaxis in ERCP with failed cannulation. Scand J Gastroenterol . 2021;56:336–341. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2020.1867894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeurnink SM, Steyerberg EW, van Hooft JE, van Eijck CH, Schwartz MP, Vleggaar FP, Kuipers EJ, Siersema PD Dutch SUSTENT Study Group. Surgical gastrojejunostomy or endoscopic stent placement for the palliation of malignant gastric outlet obstruction (SUSTENT study): a multicenter randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc . 2010;71:490–499. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teoh AYB, Kitano M, Itoi T, Pérez-Miranda M, Ogura T, Chan SM, Serna-Higuera C, Omoto S, Torres-Yuste R, Tsuichiya T, Wong KT, Leung CH, Chiu PWY, Ng EKW, Lau JYW. Endosonography-guided gallbladder drainage vs percutaneous cholecystostomy in very high-risk surgical patients with acute cholecystitis: an international randomised multicentre controlled superiority trial (DRAC 1) Gut . 2020;69:1085–1091. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tempero MA, Malafa MP, Chiorean EG, Czito B, Scaife C, Narang AK, Fountzilas C, Wolpin BM, Al-Hawary M, Asbun H, Behrman SW, Benson AB, Binder E, Cardin DB, Cha C, Chung V, Dillhoff M, Dotan E, Ferrone CR, Fisher G, Hardacre J, Hawkins WG, Ko AH, LoConte N, Lowy AM, Moravek C, Nakakura EK, O'Reilly EM, Obando J, Reddy S, Thayer S, Wolff RA, Burns JL, Zuccarino-Catania G. Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma, Version 1.2019. J Natl Compr Canc Netw . 2019;17:202–210. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2019.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Veldhuisen E, van den Oord C, Brada LJ, Walma MS, Vogel JA, Wilmink JW, Del Chiaro M, van Lienden KP, Meijerink MR, van Tienhoven G, Hackert T, Wolfgang CL, van Santvoort H, Groot Koerkamp B, Busch OR, Molenaar IQ, van Eijck CH, Besselink MG Dutch Pancreatic Cancer Group and International Collaborative Group on Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer. Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer: Work-Up, Staging, and Local Intervention Strategies. Cancers (Basel) . 2019;11 doi: 10.3390/cancers11070976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haeno H, Gonen M, Davis MB, Herman JM, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Michor F. Computational modeling of pancreatic cancer reveals kinetics of metastasis suggesting optimum treatment strategies. Cell . 2012;148:362–375. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oba A, Ho F, Bao QR, Al-Musawi MH, Schulick RD, Del Chiaro M. Neoadjuvant Treatment in Pancreatic Cancer. Front Oncol . 2020;10:245. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma C, Eltawil KM, Renfrew PD, Walsh MJ, Molinari M. Advances in diagnosis, treatment and palliation of pancreatic carcinoma: 1990-2010. World J Gastroenterol . 2011;17:867–897. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i7.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharaiha RZ, Khan MA, Kamal F, Tyberg A, Tombazzi CR, Ali B, Tombazzi C, Kahaleh M. Efficacy and safety of EUS-guided biliary drainage in comparison with percutaneous biliary drainage when ERCP fails: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc . 2017;85:904–914. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Han SY, Kim SO, So H, Shin E, Kim DU, Park DH. EUS-guided biliary drainage vs ERCP for first-line palliation of malignant distal biliary obstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep . 2019;9:16551. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-52993-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teoh A, EUS - Guided Choledocho-duodenostomy Versus ERCP With Covered Metallic Stents in Patients With Unresectable Malignant Distal Common Bile Duct Strictures. A Multi-centred Randomised Controlled Trial. [Accessed 29 November 2020]. In ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): U.S. National Library of Medicine. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03000855 . ClinicalTrial.gov Identifier: NCT03000855. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Bronswijk M, Vanella G, van Malenstein H, Laleman W, Jaekers J, Topal B, Daams F, Besselink MG, Arcidiacono PG, Voermans RP, Fockens P, Larghi A, van Wanrooij RLJ, Van der Merwe SW. Laparoscopic vs EUS-guided gastroenterostomy for gastric outlet obstruction: an international multicenter propensity score-matched comparison (with video) Gastrointest Endosc . 2021;94:526–536.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2021.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ge PS, Young JY, Dong W, Thompson CC. EUS-guided gastroenterostomy vs enteral stent placement for palliation of malignant gastric outlet obstruction. Surg Endosc . 2019;33:3404–3411. doi: 10.1007/s00464-018-06636-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khashab MA, Bukhari M, Baron TH, Nieto J, El Zein M, Chen YI, Chavez YH, Ngamruengphong S, Alawad AS, Kumbhari V, Itoi T. International multicenter comparative trial of endoscopic ultrasonography-guided gastroenterostomy vs surgical gastrojejunostomy for the treatment of malignant gastric outlet obstruction. Endosc Int Open . 2017;5:E275–E281. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-101695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takinami M, Murohisa G, Yoshizawa Y, Shimizu E, Nagasawa M. Risk factors for cholecystitis after stent placement in patients with distal malignant biliary obstruction. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci . 2020;27:470–476. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jung JH, Park SW, Hyun B, Lee J, Koh DH, Chung D. Identification of risk factors for obstructive cholecystitis following placement of biliary stent in unresectable malignant biliary obstruction: a 5-year retrospective analysis in single center. Surg Endosc . 2021;35:2679–2689. doi: 10.1007/s00464-020-07694-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cao J, Peng C, Ding X, Shen Y, Wu H, Zheng R, Wang L, Zou X. Risk factors for post-ERCP cholecystitis: a single-center retrospective study. BMC Gastroenterol . 2018;18:128. doi: 10.1186/s12876-018-0854-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rimbaş M, Crinò SF, Rizzatti G, La Greca A, Sganga G, Larghi A. EUS-guided gallbladder drainage: Where will we go next? Gastrointest Endosc . 2021;94:419–422. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2021.03.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saumoy M, Tyberg A, Brown E, Eachempati SR, Lieberman M, Afaneh C, Kunda R, Cosgrove N, Siddiqui A, Gaidhane M, Kahaleh M. Successful Cholecystectomy After Endoscopic Ultrasound Gallbladder Drainage Compared With Percutaneous Cholecystostomy, Can it Be Done? J Clin Gastroenterol . 2019;53:231–235. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fabbri C, Fugazza A, Binda C, Zerbi A, Jovine E, Cennamo V, Repici A, Anderloni A. Beyond palliation: using EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy with a lumen-apposing metal stent as a bridge to surgery. a case series. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis . 2019;28:125–128. doi: 10.15403/jgld.2014.1121.281.eus. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gaujoux S, Jacques J, Bourdariat R, Sulpice L, Lesurtel M, Truant S, Robin F, Prat F, Palazzo M, Schwarz L, Buc E, Sauvanet A, Taibi A, Napoleon B. Pancreaticoduodenectomy following endoscopic ultrasound-guided choledochoduodenostomy with electrocautery-enhanced lumen-apposing stents an ACHBT - SFED study. HPB (Oxford) . 2021;23:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vanella G, Tamburrino D, Dell'Anna G, Petrone MC, Crippa S, Falconi M, Arcidiacono PG. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastrojejunostomy does not prevent pancreaticoduodenectomy after long-term symptom-free neoadjuvant treatment. Endoscopy . 2021 doi: 10.1055/a-1408-1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bronswijk M, van Malenstein H, Laleman W, Van der Merwe S, Vanella G, Petrone MC, Arcidiacono PG. EUS-guided gastroenterostomy: Less is more! VideoGIE . 2020;5:442. doi: 10.1016/j.vgie.2020.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bronswijk M, Vanella G, Van der Merwe S. Double EUS bypass: same sequence, different reasons. VideoGIE . 2021;6:282. doi: 10.1016/j.vgie.2021.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Puga M, Consiglieri CF, Busquets J, Pallarès N, Secanella L, Peláez N, Fabregat J, Castellote J, Gornals JB. Safety of lumen-apposing stent with or without coaxial plastic stent for endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of pancreatic fluid collections: a retrospective study. Endoscopy . 2018;50:1022–1026. doi: 10.1055/a-0582-9127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bang JY, Navaneethan U, Hasan MK, Sutton B, Hawes R, Varadarajulu S. Non-superiority of lumen-apposing metal stents over plastic stents for drainage of walled-off necrosis in a randomised trial. Gut . 2019;68:1200–1209. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-315335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]