Abstract

Objectives

To assess the prevalence, risk factors and psychological impact of infertility among females. This review summarises the available evidence, effect estimates and strength of statistical associations between infertility and its risk factors.

Study design

Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data sources

MEDLINE, CINAHL and ScienceDirect were searched through 23 January 2022.

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria involved studies that reported the psychological impact of infertility among women. We included cross-sectional, case–control and cohort designs, published in the English language, conducted in the community, and performed at health institution levels on prevalence, risk factors and psychological impact of infertility in women.

Data extraction and synthesis

Two reviewers independently extracted and assess the quality of data using the Joanna Briggs Institute Meta-Analysis. The outcomes were assessed with random-effects model and reported as the OR with 95% CI using the Review Manager software.

Results

Thirty-two studies with low risk of bias involving 124 556 women were included. The findings indicated the overall pooled prevalence to be 46.25% and 51.5% for infertility and primary infertility, respectively. Smoking was significantly related to infertility, with the OR of 1.85 (95% CI 1.08 to 3.14) times higher than females who do not smoke. There was a statistical significance between infertility and psychological distress among females, with the OR of 1.63 (95% CI 1.24 to 2.13). A statistical significance was noted between depression and infertility among females, with the OR of 1.40 (95% CI 1.11 to 1.75) compared with those fertile.

Conclusions

The study results highlight an essential and increasing mental disorder among females associated with infertility and may be overlooked. Acknowledging the problem and providing positive, supportive measures to females with infertility ensure more positive outcomes during the therapeutic process. This review is limited by the differences in definitions, diagnostic cut points, study designs and source populations.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42021226414.

Keywords: Public health, Maternal medicine, PRIMARY CARE, Reproductive medicine, MENTAL HEALTH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Meta-analysis of studies according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.

Joanna Briggs Institute Meta-Analysis for assessing the quality of included studies.

Only studies with a low risk of bias were included in the analyses.

Heterogeneity and subgroup analyses were performed.

The search was restricted to English-language articles only.

Introduction

Infertility is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the inability to conceive after 1 year (or longer) of unprotected intercourse.1 It is classified as primary or secondary. Primary infertility is denoted for those women who have not conceived previously.2 In secondary infertility, there is at least one conception, but it fails to repeat.2 In 2002, the WHO estimated that infertility affects approximately 80 million people in all parts of the world.3 It affects 10%–15% of couples in their lifetime.4 5 The prevalence of infertility is concerned, it is high (up to 21.9%): primary infertility at 3.5% and secondary infertility at 18.4%.6 It is generally accepted that infertility rates are not estimated correctly. The reasons could hinder the measurement of the prevalence, imperfect measurement methods, and unknown kinds of infertility resulting from cultural biases.7

Infertility is a multidimensional stressor requiring several kinds of emotional adjustments.4 It is associated with dysfunction in sexual relationships, anxiety, depression, difficulties in marital life and identity problems.8 The impact of infertility may be long-lasting, even beyond the initial period of childlessness has passed.9 10 In the general population, major depression is two to three times as common among women as among men.11 In the United States, the 12-month prevalence of any mood disorder is 14.1% in females and 8.5% in males, whereas any anxiety disorder is 22.6% in females and 11.8% in males.12 Thus, depression is one of the most common negative emotions associated with infertility,13 14 which the local social and cultural context may influence.

Determining the psychological impact of infertility among women worldwide provides a better assessment than discrete primary studies. Identifying this impact helps gain a clear understanding of the issue and serves as a basis for an appropriate preventive strategy. In addition, it applies to primary prevention that could potentially prevent conditions affecting adverse psychological well-being. We aimed to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis on infertility among females with regard to its pooled prevalence, risk factors and psychological impact in observational studies conducted worldwide. This review will summarise the available evidence, effect estimates, and strength of statistical associations between infertility and its risk factors.

Materials and methods

Study design and search strategy

A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies were conducted to assess the psychological impact of infertility among women. The study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.15

A systematic search was performed in MEDLINE (PubMed), CINAHL (EBSCOhost) and ScienceDirect. The search was done using text words such as “infertility,” “prevalence,” “risk factor,” “psychology,” “mental,” “quality of life,” “anxiety, “depression” and “stress.” The search terms were flexible and tailored to various electronic databases (online supplemental file). All studies published from the inception of these databases until 23 January 2022 were retrieved to assess their eligibility for inclusion in this study. The search was restricted to full-text and English-language articles. To find additional potentially eligible studies, reference lists of included citations were cross-checked.

bmjopen-2021-057132supp001.pdf (14KB, pdf)

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria involved studies that reported the psychological impact of infertility among women. Studies with cross-sectional, case-control and cohort designs, published in the English language, conducted in the community, and performed at health institution levels were included. Case series/reports, conference papers, proceedings, articles available only in an abstract form, editorial reviews, letters of communication, commentaries, systematic reviews and qualitative studies were excluded.

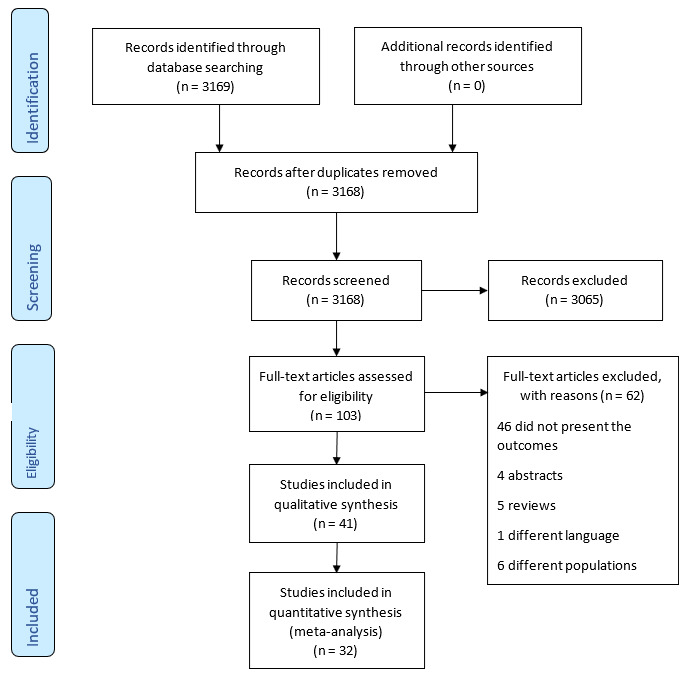

Study selection and screening

All records identified by our search strategy were exported to the EndNote software. Duplicate articles were removed. Two independent reviewers screened the titles and abstracts of the identified articles. The full text of eligible studies was obtained and read thoroughly to assess their suitability. A consensus discussion was held in the event of a conflict between the two reviewers, and a third reviewer was consulted. The search method is presented in the PRISMA flow chart showing the studies that were included and excluded with reasons for exclusion (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing the included studies for systemic review and meta-analysis on the prevalence, risk factors and psychological impact of infertility among women.

Quality assessment and bias

A critical appraisal was undertaken to assess data quality using the Joanna Briggs Institute Meta-Analysis for cross-sectional, case–control and cohort studies.16 Two reviewers performed bias assessments independently. The risk of bias was considered low when more than 70% of the answers were ‘yes,’ moderate when 50%–69% of the answers were ‘yes,’ and high when up to 49% of the answers were ‘yes’. Studies that showed a high and moderate risk of bias were excluded from the review.

Data extraction process

Two reviewers independently extracted data using the NVivo software (V.12). The process included the first author, publication year, study location, study design and setting, study population, sample size, psychological impact, infertility definition and data in calculating effect estimates for psychological impact.

Result synthesis and statistical analysis

The outcomes were reported as the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). The analysis was performed using the Review Manager software (V.5.4; Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark). A random-effects model was employed to pool data. The I2 statistic was used to assess heterogeneity, with a guide as outlined: 0%–40% might not be important; 30%–60% may represent moderate heterogeneity; 50%–90% may represent substantial heterogeneity, and 75%–100% may represent considerable heterogeneity.17 A subgroup analysis was performed based on countries (developed and developing) and comorbidity (presence and absence of comorbidity) if an adequate number of studies were available. Funnel plots were used to assess publication bias if indicated.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

A total of 3169 articles were retrieved through an electronic search using different search terms. Forty-eight duplicate records were removed. Of the 3168 articles screened for eligibility, 3065 were excluded by their title and abstract evaluation. The full text of 103 articles was searched. Subsequently, 62 articles were excluded: 46 did not present the main outcomes, 6 were performed in different populations, 5 were review articles, 4 had only abstracts and 1 was published in a non-English language (figure 1). A total of 41 studies underwent quality assessment, of which nine had moderate and high risk of bias.

Finally, 32 studies with low risk of bias were explored in the review: 22 were cross-sectional, 8 were case–control and 2 were cohort studies. Different countries were involved. Five studies were conducted in Iran,18–22 four in Turkey,23–26 three in Italy,27–29 three in America,30–32 three in Sweden,33–35 two in India,36 37 two in the Netherlands,38 39 one in Finland,9 two in Africa,40 41 one in Saudi Arabia,42 one in Japan,43 two in China44 45 one in Pakistan46 and two in Greece.47 48 The smallest sample size was 87,47 and the largest was 98 320.39 Overall, this study included 124 556 women (table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of research articles included in this systemic review and meta-analysis of infertility (n=32)

| No | Authors | Study area | Study design | Sample size | Female infertility | Quality assessment (%) |

| 1 | Aggarwal et al, 201336 | India | Cross-sectional | 500 | 267 | 87.5 |

| 2 | Albayrak and Günay, 200723 | Kayseri, Turkey | Cross-sectional | 300 | 150 | 87.5 |

| 3 | Biringer et al, 201533 | North Trondelag, Sweden | Cross-sectional | 12 584 | 1696 | 100 |

| 4 | Klemetti et al, 20109 | Finlad | Cross-sectional | 2291 | 239 | 100 |

| 5 | Bakhtiyar et al, 201918 | Lorestan, Iran | Case control | 720 | 180 | 70 |

| 6 | Alhassan et al, 201440 | Ghana | Cross-sectional | 100 | 100 | 87.5 |

| 7 | Alosaimi et al, 201542 | Riyadh, Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional | 406 | 206 | 100 |

| 8 | Matsubaya et al, 200143 | Tokai, Japan | Cross-sectional | 182 | 101 | 87.5 |

| 9 | Açmaz et al, 201324 | Kayseri, Turkey | Cross-sectional | 133 | 86 | 87.5 |

| 10 | Bai et al, 201944 | Ningxia province, China | Cross-sectional | 740 | 380 | 100 |

| 11 | Bazarganipour et al, 201319 | Kashan, Iran | Cross-sectional | 300 | 238 | 100 |

| 12 | Begum and Hasan, 201446 | Karachi, Pakistan | Cross-sectional | 120 | 60 | 87.5 |

| 13 | Volgsten et al, 200835 | Sweden | Cross-sectional | 825 | 122 | 88.9 |

| 14 | Bringhenti et al, 199727 | Italy | Cross-sectional | 179 | 122 | 87.5 |

| 15 | Lansakara and Wickramasinghe, 201137 | Colombo, Sri Lanka | Cross-sectional | 354 | 177 | 87.5 |

| 16 | Noorbala et al, 200920 | Tehran, Iran | Cross-sectional | 300 | 150 | 87.5 |

| 17 | Salih Joelsson et al, 201734 | Sweden | Cross-sectional | 3583 | 468 | 100 |

| 18 | Aydin et al, 201525 | Istanbul, Turkey | Cross-sectional | 88 | 88 | 87.5 |

| 19 | Tarlatzis et al, 199347 | Greece | Cohort | 87 | 69 | 81.8 |

| 20 | Ramezan et al, 200421 | Tehran, Iran | Cross-sectional | 370 | 370 | 87.5 |

| 21 | Aarts et al, 201138 | Netherlands | Cross-sectional | 472 | 472 | 87.5 |

| 22 | Baldur et al, 201339 | Denmark | Cohort | 98 320 | 44 773 | 100 |

| 23 | Diamond et al, 201731 | United states | Cross-sectional | 1594 | 1594 | 87.5 |

| 24 | Downey and McKinney, 199230 | New York City | Case control | 201 | 118 | 80 |

| 25 | Fassino et al, 200228 | Italy | Case control | 172 | 172 | 90 |

| 26 | Guz et al, 200326 | Turkey | Case control | 100 | 50 | 80 |

| 27 | Omani et al, 201722 | Tehran, Iran | Cross-sectional | 312 | 149 | 100 |

| 28 | Salomão et al, 201832 | Brazil | Case control | 280 | 140 | 80 |

| 29 | Sbaragli et al, 200829 | Siena, Italy | Case control | 302 | 82 | 100 |

| 30 | Akalewold et al, 202241 | Ethiopia | Cross-sectional | 409 | 66 | 100 |

| 31 | Kleanthi et al, 202148 | Greece | Case control | 177 | 90 | |

| 32 | Peng et al, 202145 | China | Case control | 450 | 100 |

The quality assessment was performed based on the Joanna Briggs Institute Meta-Analysis for cross-sectional, case–control and cohort studies.

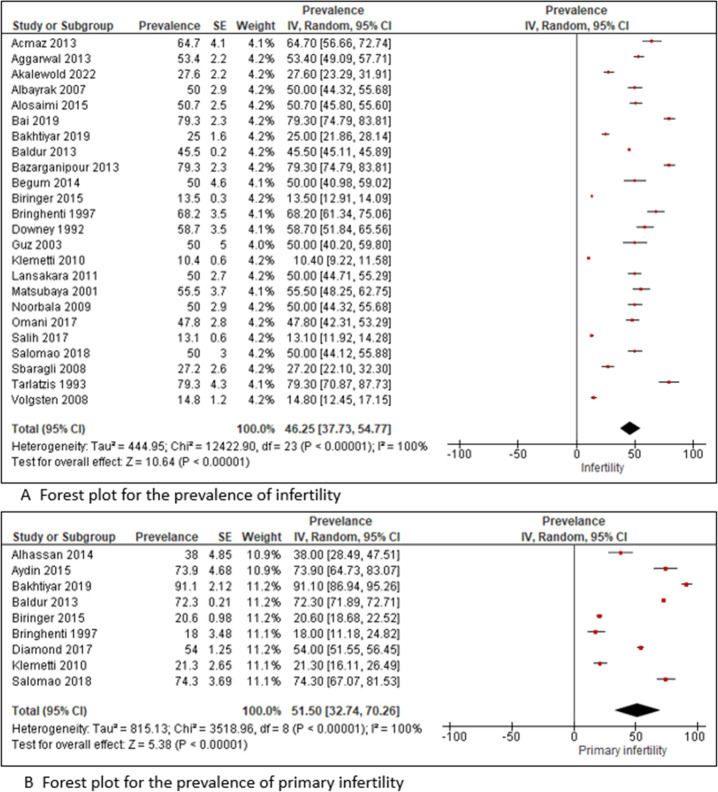

Prevalence

Of the included studies, 20 were conducted in a hospital-based setting, 49 23 33 37 in a community-based setting and 218 46 in both hospital-based and community-based settings. A slight difference in the prevalence of infertility was observed in the review. A lower prevalence (10.4%) of infertility9 was observed in a community-based setting, and a higher prevalence (79.3%)44 47 was noted in a hospital-based setting. The overall pooled prevalence of infertility was 46.25% (95% CI 37.73% to 54.77%; I2=100%). Twenty-four articles were included for the estimation of pooled prevalence of infertility among females (figure 2). The funnel plot was asymmetry with smaller studies and lower prevalence being missing on the left side. The results of the assessment of bias based on the funnel plot asymmetry were not shown but available on request. Out of this, nine were used for the estimation of pooled prevalence of primary infertility.

Figure 2.

Forest plot depicting the prevalence of infertility. IV, inverse variance.

The overall pooled prevalence of primary infertility was 51.5% (95% CI 32.74% to 70.26%; I2=100%) (figure 1). The lowest prevalence (18%) of primary infertility was reported in a hospital-based study,27 and the highest prevalence (91.1%) was observed in both community- and hospital-based studies conducted in Iran18 (figure 2).

Risk factors of infertility

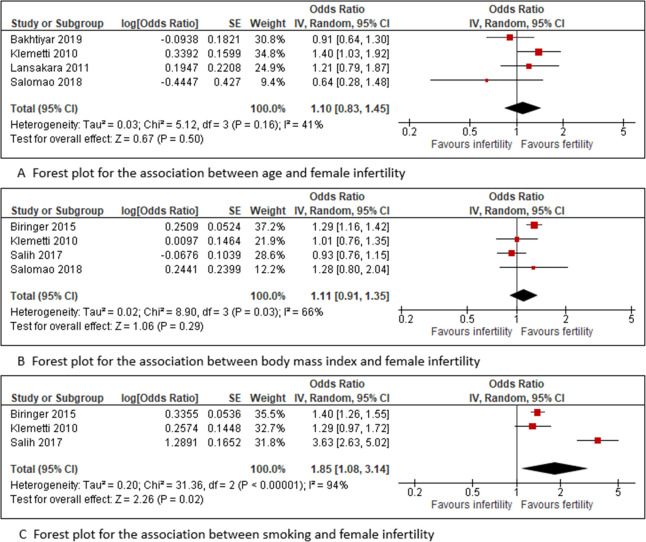

In this study, risk factors such as age, body mass index (BMI), smoking and family income were evaluated for their association with infertility. Five studies were included to assess age older than 35 years as a risk factor for infertility regarding the association between age and infertility among females.9 18 32 37 The pooled meta-regression analysis showed no significant difference in the occurrence of infertility in females aged 35 years or older compared with those younger than 35 years, with the odds being 1.10 (95% CI 0.83 to 1.45; I2=41%). Similarly, there was no association between BMI and infertility in four studies,9 32–34 with odds of 1.11 (95% CI 0.91 to 1.36; I2=66%). However, smoking was found to be significantly related to infertility in three studies,9 33 34 with the odds being 1.85 (95% CI 1.08 to 3.14; I2=94%) times higher compared with those who do not smoke (figure 3). There was no difference observed (OR 0.85; 95% CI 0.59 to 1.23; I2=34%) regarding the association between low income and infertility in five studies.9 20 24 37 46

Figure 3.

Forest plot depicting the risk factors associated with infertility. IV, inverse variance.

The psychological impact of infertility

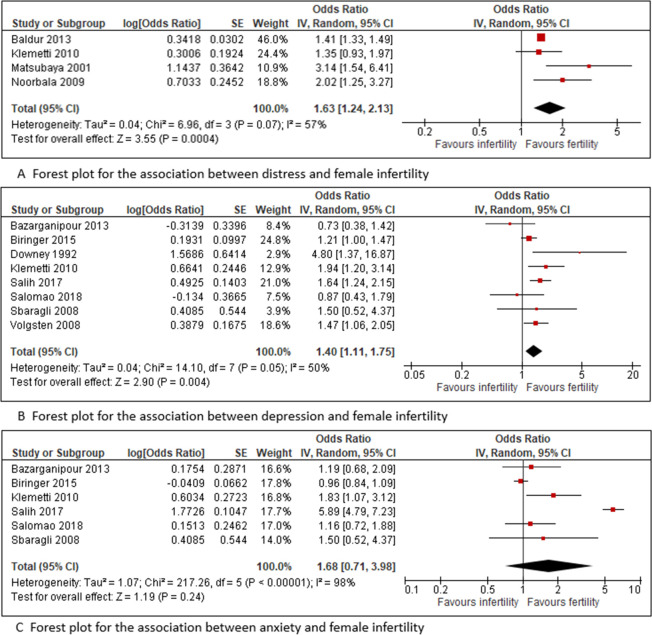

In this study, psychological impact—including distress, depression and anxiety—was evaluated. Four studies were included to assess the distress caused by infertility.9 20 39 43 The pooled meta-regression analysis showed a statistical significance between infertility and psychological distress among females, with the odds being 1.63 (95% CI 1.24 to 2.13; I2=57%) (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Forest plot depicting the psychological impact of infertility. IV, inverse variance.

Eight studies were included to assess the association between depression and infertility among females.9 19 29 30 32–35 Four studies showed significant9 30 34 35 associations, and four showed no significant19 29 32 33 associations. The pooled meta-regression analysis showed a statistical significance between depression and infertility among females, with the odds being 1.40 (95% CI 1.11, 1.75; I2=50%) compared with those fertile. However, there was no association between anxiety and infertility in the six studies,9 19 29 32–34 with a pooled meta-regression analysis of OR of 1.68 (95% CI 0.71, 3.98; I2=98%) (figure 4).

Discussion

Infertility is a worldwide public health agenda affecting an individual’s personal, social and economic life and the family as a whole. This study was conducted to determine the pooled prevalence and risk factors of infertility among females. In this meta-analysis, the pooled prevalence of infertility and primary infertility among females was 45.85% (95% CI 37.12% to 54.57%) and 51.5% (95% CI 32.74% to 70.26%), respectively. The prevalence of infertility among females in this study is higher than in a review conducted in 2007 (between 3.5% and 16.7%).49 It is because most of the sample size for the research articles in this meta-analysis is from an infertility clinic. Regarding primary infertility, it is similar to a review in Africa at 49.9% (95% CI 41.34% to 58.48%).50

Various risk factors were assessed in terms of their association with infertility among females. Age was not found to be associated with infertility; however, a study on a sample comprising 7172 couples showed that the odds of being diagnosed with unexplained and tubal factor infertility are almost twice as high in women older than 35 years as those younger than 30 years.51 There was no association noted between BMI and infertility among females. Vahratian and Smith52 found that a large proportion of females seeking medical help to become pregnant are obese, and the risk of infertility is three times higher in those obese than nonobese.53 Smoking is a crucial risk factor for females, and it shows that females who smoke have a 1.8 times higher risk of developing infertility than those who do not. One study pointed toward a significant association with a 60% increase in the risk of infertility among females who smoke cigarettes.54 A meta-analysis identified the pertinent literature available from 1966 through late 1997 and reported an OR of 1.60 for infertility among females who smoke compared with those who do not across all study designs.54

Infertility among females has a vast impact on psychological distress. In the current study, females with infertility have a 1.6 times higher risk of being psychologically distressed than those fertile. This is similar to a study in Taiwan,55 which found that 40.2% of the females with infertility suffer from mental disorders. A review of studies conducted in many countries suggested that women endure the major burdens caused by infertility and experience intense anxiety from being blamed for their failure to give birth.56 Infertility also contributes to the risk of having depression, with females suffering from infertility having a 1.4 times higher chance of being depressed, whereas other studies showed 67.0%57 and 35.3%58 of women with infertility were depressed. Recent research has shown that prevalence can range from 11%35 to 27%55 and 73%.57 Another study in Sweden35 reported that major depression was the most common disorder among couples suffering from infertility, with a prevalence of 10.9% in females and 5.1% in males. It shows that infertility increases the risk of depression. Therefore, it should be considered a serious warning and given a particular focus.

The risk of anxiety in females with infertility is also high. A meta-analysis by Kiani and Simbar59 showed a pooled prevalence of 36.17% (95% CI 22.47% to 49.87%) among females having anxiety because of infertility. In another systematic review, Sawyer et al60 reported a 14.8% prevalence of anxiety in females with infertility and a prevalence of 14.0% among women in their prenatal and postnatal periods. In most societies, having a child is closely related to a woman’s identity. Being a mother is equated with being female,59 which results in high levels of stress and a sense of worthlessness in those childless.61 In addition, a female who cannot conceive is at risk of social insecurity and becomes anxious because she foresees a future with no child to take care of them in old age or case of illness.62

Strengths and limitations

This study showed the prevalence of infertility worldwide and the risk of psychological problems among such females, including studies from different countries. It also focused on the quantitative aspect of the problem to get a better view of the intervention.

However, this study is not without limitations. The differences in definitions, diagnostic cut points, study designs, and source populations make performing a meta-analysis on infertility difficult. On the contrary, there are diverse instruments to determine psychological distress, depression and anxiety that make comparing results difficult. Another limitation was the use of various instruments to assess psychological problems in the general population. None of the tools was developed specifically to investigate the incidence of factors concerning females. Although the risk factors identified in this review are not new, calling attention to the psychological impact of infertility is worthwhile.

Conclusions

This study identified that the risk of psychological distress among females with infertility is 60% higher than that among the general population. Furthermore, the risks of anxiety and depression are 60% and 40% times higher, respectively. These results highlight an important and increasing mental disorder among females that may be overlooked. Psychological distress should concern attending physicians and should be assessed to avoid any unwanted events from happening. Acknowledging the problem and taking positive, supportive measures to help females with infertility ensure more positive outcomes during the therapeutic process.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Madam Nurul Azurah Mohd Roni, a librarian from Hamdan Tahir Library, for her assistance with the database searches.

Footnotes

Contributors: Conceptualisation, NHNH, MNN and ISB; methodology, NHNH, MNN and ISB; validation MNN and NHNH; formal analysis, MNN and NANMA; investigation, NANMA; resources, MNN and NHNH; data curation, NHNH and NANMA; writing of original draft preparation and NANMA; writing of review and editing, NHNH, MNN, ISB and NANMA; visualisation, NHNH, MNN and ISB; project administration, NHNH; all authors have read and agreed to the published version. MNN is the guarantor for this review.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.WHO . Global prevalence of infertility, infecundity and childlessness. World Health Organization, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larsen U. Research on infertility: which definition should we use? Fertil Steril 2005;83:846–52. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.11.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO . The world health report 2002: reducing risks promoting healthy life. World Health Organization, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greil AL. Infertility and psychological distress: a critical review of the literature. Soc Sci Med 1997;45:1679–704. 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00102-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wasser SK, Sewall G, Soules MR. Psychosocial stress as a cause of infertility. Fertil Steril 1993;59:685–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tahir F, Shahab M, Afzal M. Male reproductive health: an important segment towards improving reproductive health of a couple. Population Research and Policy Development in Pakistan 2004:227–48. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daar AS, Merali Z. Infertility and social suffering: the case of art in developing countries 2002;21. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson KM, Sharpe M, Rattray A, et al. Distress and concerns in couples referred to a specialist infertility clinic. J Psychosom Res 2003;54:353–5. 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00398-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klemetti R, Raitanen J, Sihvo S, et al. Infertility, mental disorders and well-being--a nationwide survey. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2010;89:677–82. 10.3109/00016341003623746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.King RB. Subfecundity and anxiety in a nationally representative sample. Soc Sci Med 2003;56:739–51. 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00069-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kessler RC. Epidemiology of women and depression. J Affect Disord 2003;74:5–13. 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00426-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. results from the National comorbidity survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994;51:8–19. 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Asadi JN, Hussein ZB. Depression among infertile women in Basrah, Iraq: prevalence and risk factors. J Chin Med Assoc 2015;78:673–7. 10.1016/j.jcma.2015.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peterson BD, Sejbaek CS, Pirritano M, et al. Are severe depressive symptoms associated with infertility-related distress in individuals and their partners? Hum Reprod 2014;29:76–82. 10.1093/humrep/det412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:264–9. 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aromataris E, Munn Z. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. The Joanna Briggs Institute. Available: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global

- 17.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J. Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.1, 2020. Available: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

- 18.Bakhtiyar K, Beiranvand R, Ardalan A, et al. An investigation of the effects of infertility on women's quality of life: a case-control study. BMC Womens Health 2019;19:114. 10.1186/s12905-019-0805-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bazarganipour F, Ziaei S, Montazeri A, et al. Psychological investigation in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2013;11:141. 10.1186/1477-7525-11-141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noorbala AA, Ramezanzadeh F, Abedinia N, et al. Psychiatric disorders among infertile and fertile women. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2009;44:587–91. 10.1007/s00127-008-0467-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramezanzadeh F, Aghssa MM, Abedinia N, et al. A survey of relationship between anxiety, depression and duration of infertility. BMC Womens Health 2004;4:334–7. 10.1186/1472-6874-4-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Omani Samani R, Maroufizadeh S, Navid B, et al. Locus of control, anxiety, and depression in infertile patients. Psychol Health Med 2017;22:44–50. 10.1080/13548506.2016.1231923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Albayrak E, Günay O. State and trait anxiety levels of childless women in Kayseri, Turkey. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 2007;12:385–90. 10.1080/13625180701475665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Açmaz G, Albayrak E, Acmaz B, et al. Level of anxiety, depression, self-esteem, social anxiety, and quality of life among the women with polycystic ovary syndrome. ScientificWorldJournal 2013;2013:851815. 10.1155/2013/851815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aydın S, Kurt N, Mandel S, et al. Female sexual distress in infertile Turkish women. Turk J Obstet Gynecol 2015;12:205. 10.4274/tjod.99997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guz H, Ozkan A, Sarisoy G, et al. Psychiatric symptoms in Turkish infertile women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 2003;24:267–71. 10.3109/01674820309074691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bringhenti F, Martinelli F, Ardenti R, et al. Psychological adjustment of infertile women entering IVF treatment: differentiating aspects and influencing factors. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1997;76:431–7. 10.3109/00016349709047824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fassino S, Pierò A, Boggio S, et al. Anxiety, depression and anger suppression in infertile couples: a controlled study. Hum Reprod 2002;17:2986–94. 10.1093/humrep/17.11.2986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sbaragli C, Morgante G, Goracci A, et al. Infertility and psychiatric morbidity. Fertil Steril 2008;90:2107–11. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.10.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Downey J, McKinney M. The psychiatric status of women presenting for infertility evaluation. Am J Orthopsychiatry 1992;62:196–205. 10.1037/h0079335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diamond MP, Legro RS, Coutifaris C, et al. Sexual function in infertile women with polycystic ovary syndrome and unexplained infertility. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;217:191.e1–91.e19. 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.04.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salomão PB, Navarro PA, Romão APMS, et al. Sexual function of women with infertility. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet 2018;40:771–8. 10.1055/s-0038-1673699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Biringer E, Howard LM, Kessler U, et al. Is infertility really associated with higher levels of mental distress in the female population? results from the North-Trøndelag health study and the medical birth registry of Norway. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 2015;36:38–45. 10.3109/0167482X.2014.992411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salih Joelsson L, Tydén T, Wanggren K, et al. Anxiety and depression symptoms among sub-fertile women, women pregnant after infertility treatment, and naturally pregnant women. Eur Psychiatry 2017;45:212–9. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Volgsten H, Skoog Svanberg A, Ekselius L, et al. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in infertile women and men undergoing in vitro fertilization treatment. Hum Reprod 2008;23:2056–63. 10.1093/humrep/den154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aggarwal RS, Mishra VV, Jasani AF. Incidence and prevalence of sexual dysfunction in infertile females. Middle East Fertil Soc J 2013;18:187–90. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lansakara N, Wickramasinghe AR, Seneviratne HR. Feeling the blues of infertility in a South Asian context: psychological well-being and associated factors among Sri Lankan women with primary infertility. J Women Health 2011;51:383–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aarts JWM, van Empel IWH, Boivin J, et al. Relationship between quality of life and distress in infertility: a validation study of the Dutch FertiQoL. Hum Reprod 2011;26:1112–8. 10.1093/humrep/der051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baldur-Felskov B, Kjaer SK, Albieri V, et al. Psychiatric disorders in women with fertility problems: results from a large Danish register-based cohort study. Hum Reprod 2013;28:683–90. 10.1093/humrep/des422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alhassan A, Ziblim AR, Muntaka S. A survey on depression among infertile women in Ghana. BMC Womens Health 2014;14:42. 10.1186/1472-6874-14-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Akalewold M, Yohannes GW, Abdo ZA, et al. Magnitude of infertility and associated factors among women attending selected public hospitals in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health 2022;22:11. 10.1186/s12905-022-01601-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alosaimi FD, Altuwirqi MH, Bukhari M, et al. Psychiatric disorders among infertile men and women attending three infertility clinics in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med 2015;35:359–67. 10.5144/0256-4947.2015.359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matsubayashi H, Hosaka T, Izumi S, et al. Emotional distress of infertile women in Japan. Hum Reprod 2001;16:966–9. 10.1093/humrep/16.5.966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bai C-F, Sun J-W, Li J, et al. Gender differences in factors associated with depression in infertility patients. J Adv Nurs 2019;75:3515–24. 10.1111/jan.14171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peng M, Wen M, Jiang T, et al. Stress, anxiety, and depression in infertile couples are not associated with a first IVF or ICSI treatment outcome. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021;21:725. 10.1186/s12884-021-04202-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Begum BN, Hasan S. Psychological problems among women with infertility problem: a comparative study. J Pak Med Assoc 2014;64:1287–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tarlatzis I, Tarlatzis BC, Diakogiannis I, et al. Psychosocial impacts of infertility on Greek couples. Hum Reprod 1993;8:396–401. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a138059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kleanthi G, Maria G, Alexithymia MG. Alexithymia, stress and depression in infertile women: a case control study. Mater Sociomed 2021;33:70–4. 10.5455/msm.2021.33.70-74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boivin J, Bunting L, Collins JA, et al. International estimates of infertility prevalence and treatment-seeking: potential need and demand for infertility medical care. Hum Reprod 2007;22:1506–12. 10.1093/humrep/dem046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abebe MS, Afework M, Abaynew Y. Primary and secondary infertility in Africa: systematic review with meta-analysis. Fertil Res Pract 2020;6:20. 10.1186/s40738-020-00090-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maheshwari A, Hamilton M, Bhattacharya S. Effect of female age on the diagnostic categories of infertility. Hum Reprod 2008;23:538–42. 10.1093/humrep/dem431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vahratian A, Smith YR. Should access to fertility-related services be conditional on body mass index? Hum Reprod 2009;24:1532–7. 10.1093/humrep/dep057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rich-Edwards JW, Goldman MB, Willett WC, et al. Adolescent body mass index and infertility caused by ovulatory disorder. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1994;171:171–7. 10.1016/0002-9378(94)90465-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Augood C, Duckitt K, Templeton AA. Smoking and female infertility: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod 1998;13:1532–9. 10.1093/humrep/13.6.1532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen T-H, Chang S-P, Tsai C-F, et al. Prevalence of depressive and anxiety disorders in an assisted reproductive technique clinic. Hum Reprod 2004;19:2313–8. 10.1093/humrep/deh414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bokaie M, Simbar M, Yassini-Ardekani SM. Social factors affecting the sexual experiences of women faced with infertility: a qualitative study. Koomesh 2018;20. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guerra D, Llobera A, Veiga A, et al. Psychiatric morbidity in couples attending a fertility service. Hum Reprod 1998;13:1733–6. 10.1093/humrep/13.6.1733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alimohamadi Y, Mehri A, Sepandi M. The prevalence of depression among Iranian infertile couples: an update systematic review and meta-analysis. Middle East Fertil Soc J 2020;25:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kiani Z, Simbar M. Infertility's hidden and evident dimensions: a concern requiring special attention in Iranian Society. Iran J Public Health 2019;48:2114. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sawyer A, Ayers S, Smith H. Pre- and postnatal psychological wellbeing in Africa: a systematic review. J Affect Disord 2010;123:17–29. 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Batool SS, de Visser RO. Psychosocial and contextual determinants of health among infertile women: a cross-cultural study. Psychol Health Med 2014;19:673–9. 10.1080/13548506.2014.880492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gerrits T, Van Rooij F, Esho T, et al. Infertility in the global South: raising awareness and generating insights for policy and practice. Facts Views Vis Obgyn 2017;9:39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-057132supp001.pdf (14KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.