Key Points

Question

Is lithium treatment for bipolar disorder associated with a decrease in risk of osteoporosis?

Findings

This cohort study of 22 912 patients with bipolar disorder and 114 560 reference individuals from the general population in Denmark who were followed up for a total of 1 213 695 person-years found that bipolar disorder was associated with an increase in risk of osteoporosis and that treatment with lithium was associated with a decrease in risk of osteoporosis in a cumulative dose-response–like manner. Conversely, treatment with antipsychotics, valproate, and lamotrigine was not associated with a reduction in risk of osteoporosis.

Meaning

Lithium treatment was associated with a reduction in risk of osteoporosis; these findings warrant further investigation.

This cohort study evaluates the use of lithium in treating osteoporosis in individuals with bipolar disorder.

Abstract

Importance

Osteoporosis, a systemic skeletal disorder associated with substantial morbidity and mortality, may be particularly common among individuals with bipolar disorder. Lithium, a first-line mood-stabilizing treatment for bipolar disorder, may have bone-protecting properties.

Objective

To evaluate if treatment with lithium is associated with a decrease in risk of osteoporosis among patients with bipolar disorder.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective cohort study included 22 912 adults from the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register who received an initial diagnosis of bipolar disorder in the period from January 1, 1996, to January 1, 2019. For each patient with bipolar disorder, 5 age- and sex-matched individuals were randomly selected from the general population as reference individuals. Individuals with bipolar disorder prior to January 1, 1996, those with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder prior to being diagnosed with bipolar disorder, and those with osteoporosis prior to the index date were excluded. Of the 114 560 reference individuals included, 300 were diagnosed with bipolar disorder during follow-up and were censored from the reference group from the date of diagnosis forward. For patients with bipolar disorder, treatment periods with lithium, antipsychotics, valproate, and lamotrigine were identified. Analyses were performed between January 2021 and January 2022.

Exposures

Bipolar disorder and treatment with lithium, antipsychotics, valproate, and lamotrigine.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was osteoporosis, identified via hospital diagnoses and prescribed medications. First, incidence of osteoporosis was compared between patients with bipolar disorder and reference individuals (earliest start of follow-up at age 40 years) using Cox regression. Subsequently, incidence of osteoporosis for patients receiving treatment with lithium, antipsychotics, valproate, and lamotrigine, respectively, was compared with that of patients who were not treated with these medications.

Results

A total of 22 912 patients with bipolar disorder (median [IQR] age, 50.4 [41.2-61.0] years; 12 967 [56.6%] women) and 114 560 reference individuals (median [IQR] age, 50.4 [41.2-61.0] years; 64 835 [56.6%] women) were followed up for 1 213 695 person-years (median [IQR], 7.68 [3.72-13.24] years). The incidence of osteoporosis per 1000 person-years was 8.70 (95% CI, 8.28-9.14) among patients and 7.90 (95% CI, 7.73-8.07) among reference individuals, resulting in a hazard rate ratio (HRR) of 1.14 (95% CI, 1.08-1.20). Among patients with bipolar disorder, 8750 (38.2%) received lithium, 16 864 (73.6%) received an antipsychotic, 3853 (16.8%) received valproate, and 7588 (33.1%) received lamotrigine (not mutually exclusive). Patients with bipolar disorder treated with lithium had a decrease in risk of osteoporosis (HRR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.53-0.72) compared with patients not receiving lithium. Treatment with antipsychotics, valproate, and lamotrigine was not associated with reduced risk of osteoporosis.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this study, bipolar disorder was associated with an increase in risk of osteoporosis, and lithium treatment was associated with a decrease in risk of osteoporosis. These findings suggest that bone health should be a priority in the clinical management of bipolar disorder and that the potential bone-protective properties of lithium should be subjected to further study, both in the context of bipolar disorder and in osteoporosis.

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a common chronic systemic skeletal disorder associated with substantial morbidity and mortality.1,2 While advanced age and female sex are the main characteristics associated with risk of osteoporosis at the population level, there are several additional risk factors at the individual level.1,2 Recent evidence suggests that bipolar disorder may be such a risk factor.3,4,5

Bipolar disorder is a severe mental illness characterized by recurrent manic, hypomanic, depressive, and mixed episodes, which affects 1% to 2% of the population worldwide.6,7 While manic and hypomanic episodes are defining for the disorder, it is the depressive episodes that account for the main burden of illness,8,9,10 and depression is considered to be an important risk factor for poor bone health and osteoporosis, possibly mediated by lifestyle factors, such as poor diet and lack of physical activity or exercise.11,12 Accordingly, a recent meta-analysis3 suggested that individuals with bipolar disorder are at elevated risk of fractures. Two small cross-sectional studies have found lower bone mineral density among 61 drug-naive newly diagnosed patients with bipolar disorder compared with healthy control individuals4 and a high prevalence of osteopenia (50%) and osteoporosis (12.5%) among 16 elderly inpatients with bipolar disorder, respectively.5 However, there is a lack of adequately powered longitudinal studies on the associations among bipolar disorder, its pharmacological treatment, and osteoporosis.

A wide range of medications may affect the risk of osteoporosis.1,13 Lithium, a cornerstone in the pharmacological treatment of bipolar disorder since the 1950s14,15 that remains widely used,6,16 is of interest in this regard. While some small observational studies have indicated that treatment with lithium is associated with reduced risk of fractures, others point to negative or neutral effects of lithium on bone mass density.17,18,19,20,21,22 That lithium could potentially have a beneficial effect on bone structure is supported mechanistically by animal studies demonstrating that lithium stimulates bone formation through activation of β-catenin via inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3β.20,21 If lithium also stimulates bone formation to a substantial degree in humans, it may protect individuals with bipolar disorder receiving lithium treatment against development of osteoporosis. However, we are not aware of any longitudinal studies having addressed this possibility. A potential explanation for this gap in the literature is that such studies require data from a period in which treatment for bipolar disorder is ongoing and the risk of osteoporosis is present. As treatment for bipolar disorder is often initiated in young adulthood while osteoporosis is a disease predominantly affecting elderly individuals,1,2 such data are rare.

To clarify associations among bipolar disorder, its pharmacological treatment, and the risk of osteoporosis—and the potentially protective effect of lithium on the risk of developing osteoporosis in particular—we designed a nationwide longitudinal register-based study addressing the following sequential research questions. Is the risk of osteoporosis elevated among individuals with bipolar disorder compared with age- and sex-matched individuals from the general population? Among patients with bipolar disorder, is treatment with lithium associated with a decrease in risk of developing osteoporosis?

Methods

Data Sources

This study was based on data from nationwide Danish registers. Every legal resident in Denmark receives a unique personal registration number, either at birth or when becoming a legal resident on immigration. The unique personal registration number enables data linkage across registers at the level of the individual.23 In the present study, we used the following registers: the Danish Civil Registration System, which contains information on vital status23; the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register and the Danish National Patient Register, which contain information on all inpatient contacts to Danish hospitals since 1994 as well as all outpatient and emergency department contacts since 1995, including diagnoses registered in accordance with the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10)24,25,26; and the Danish National Prescription Registry, which contains information on all prescriptions redeemed at Danish pharmacies since 1995, registered in accordance with the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) coding system managed by the World Health Organization.27,28

The use of deidentified register data for the purpose of this study was approved by Statistics Denmark and the Danish Health Data Authority. No further ethical approval is required for register-based research in Denmark. The project is registered with the Danish Data Protection Agency.

Study Populations

Incidence of Osteoporosis

Our first aim was to compare the incidence of osteoporosis among individuals with bipolar disorder with that among reference individuals from the general population. We used the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register to identify all individuals with bipolar disorder (at the time of their first ICD-10 diagnosis of bipolar disorder) in the period from January 1, 1996, to January 1, 2019. Individuals registered with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder prior to January 1, 1996, as well as individuals registered with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder prior to being diagnosed with bipolar disorder were excluded (ICD-10 codes are presented in eTable 1 in the Supplement). We defined the index date as either the date of incident bipolar disorder (for those having received the incident bipolar disorder diagnosis on or after their 40th birthday) or the 40th birthday (for those having received the incident bipolar disorder diagnosis before their fortieth birthday). This was done to focus on a period in which the risk of osteoporosis was present.1 Via the Danish National Patient Register and the Danish National Prescription Registry, we excluded individuals that had a hospital contact leading to a diagnosis of osteoporosis or redeemed a prescription for a medication used in the treatment of osteoporosis prior to the index date (ICD-10 and ATC-codes used to operationalize osteoporosis are presented in eTable 1 in the Supplement). For each individual with bipolar disorder, we used the Danish Civil Registration System to match 5 randomly selected reference individuals from the entire Danish population on index date, birth year, and sex. Reference individuals were without bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and osteoporosis up until the index date (defined as for the individuals with bipolar disorder). Of 114 560 reference individuals, 300 were diagnosed with bipolar disorder during follow-up, resulting in them being censored from the reference groups on the date of the diagnosis and followed up as patients with bipolar disorder from that date.

Lithium Treatment and the Risk of Developing Osteoporosis

To investigate how treatment with lithium, as well as other drugs with mood-stabilizing properties, is associated with the risk of developing osteoporosis, we focused on the patients with bipolar disorder described above and identified all prescriptions for lithium, any antipsychotic, valproate, and lamotrigine they had redeemed after the index date (ATC codes are presented in eTable 1 in the Supplement), as antipsychotics, lamotrigine, and valproate are also routinely used in the treatment of bipolar disorder.6

Definition of Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis was defined either by a diagnosis of osteoporosis following an inpatient or outpatient hospital contact with osteoporosis with pathological fracture, osteoporosis without pathological fracture or osteoporosis in other disease or by redemption of a prescription for a medication used in the treatment of osteoporosis (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Thereby, we aimed to cover all diagnosed and treated cases of osteoporosis in Denmark, from less severe (ie, redeemed prescriptions, including those from all general practitioners in Denmark) to more severe (ie, requiring hospital contact).

Statistical Analysis

Association Between Bipolar Disorder and Osteoporosis

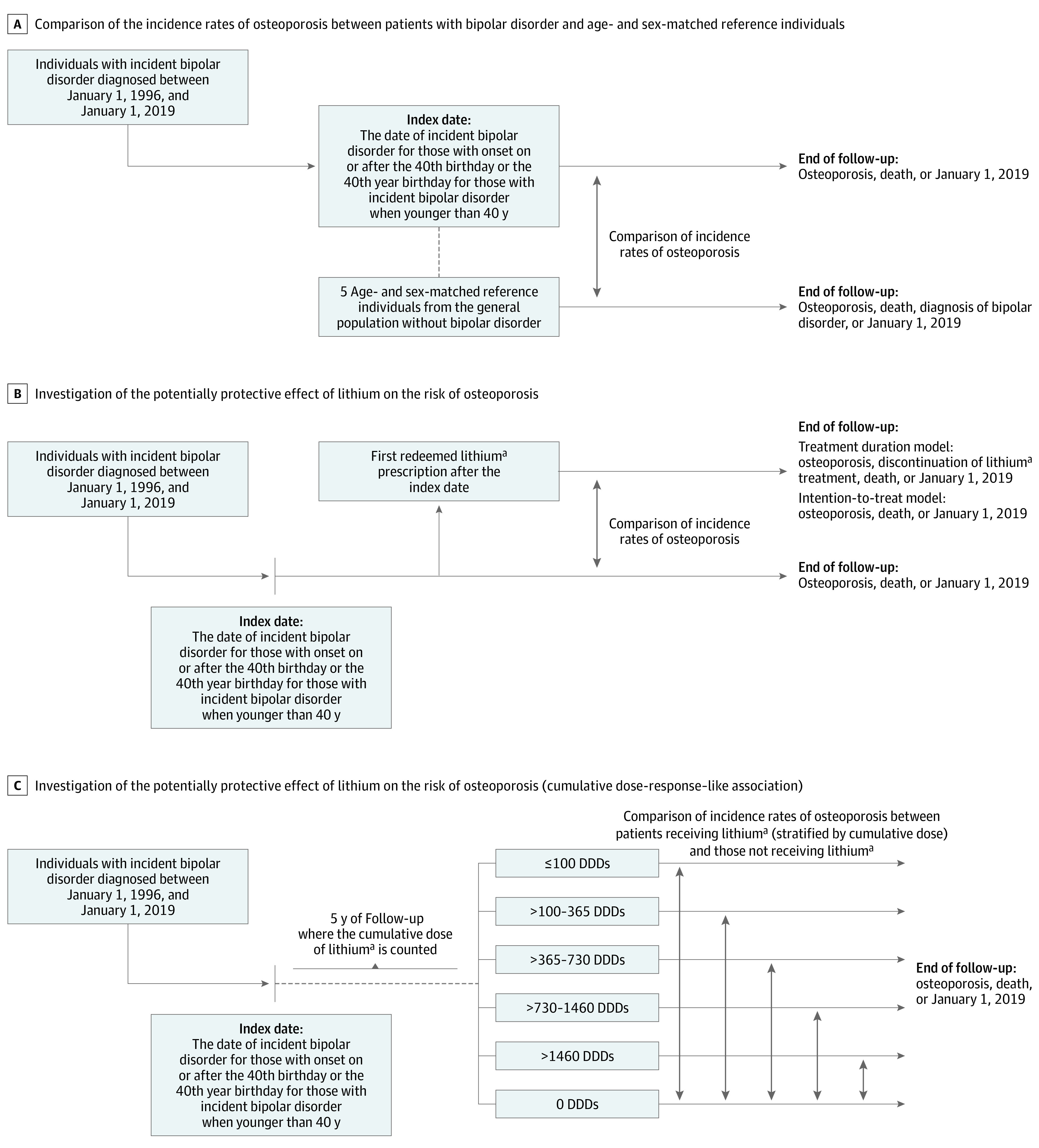

We followed up the individuals with bipolar disorder from the index date and the age- and sex-matched reference individuals from the general population from the matched date until death, January 1, 2019, or development of osteoporosis (or date of bipolar disorder diagnosis for the reference individuals), whichever came first. We estimated incidence rates of osteoporosis per 1000 person-years of follow-up and used Cox proportional hazard regression to compare the incidence rates of osteoporosis between individuals with bipolar disorder and the matched reference individuals. For an illustration of this analysis, see Figure 1A. We also plotted cumulative incidence proportions (Aalen-Johansen curves) for osteoporosis. To understand (post hoc) whether our finding of an increased cumulative incidence proportion for osteoporosis among the reference individuals compared with the patients with bipolar disorders in the late stages of follow-up was likely because of healthy survivor bias (substantial mortality among those with bipolar disorder resulting in selective survival of healthy individuals with a beneficial prognosis with regard to risk of developing osteoporosis), we repeated the Cox proportional hazard regression described above using death as outcome. Furthermore, we conducted 2 sensitivity analyses stratifying on incident and prevalent bipolar disorder and restricting the outcome to osteoporosis with pathological fracture (ICD-10 code M80) (eMethods in the Supplement).

Figure 1. Illustrations of the Design (The Cohorts Used in the Follow-up Analyses).

DDD indicates defined daily dose.

aThe analyses were repeated after replacing lithium with antipsychotics, valproate and lamotrigine, respectively. The analyses on these drugs were performed in the same way as the analyses on lithium.

Lithium Treatment of Bipolar Disorder and the Risk of Developing Osteoporosis

We compared the incidence rate of osteoporosis between patients with bipolar disorder that redeemed a lithium prescription and patients with bipolar disorder that did not redeem a lithium prescription using Cox proportional hazards regression. To avoid survival bias, patients that initiated lithium treatment were considered unexposed from the index date until they redeemed the first lithium prescription. Thereby, we accounted for the fact that the time to initiation of lithium treatment represents unexposed survival time, which could lead to immortal time bias if not treated correctly. We used 2 different models to assess the effect of lithium on the risk of osteoporosis. The first model took treatment duration into account and followed up the patients with bipolar disorder from the date of the first redeemed lithium prescription after the index date until lithium discontinuation (defined as 6 months after the last redeemed lithium prescription), osteoporosis, death, or January 1, 2019, whichever came first. The second model used an intention-to-treat approach in which patients with bipolar disorder were followed up from the date of the first redeemed lithium prescription until osteoporosis, death, or January 1, 2019, whichever came first (Figure 1B).

Because use of corticosteroids, presence of chronic somatic diseases, and low weight are known to negatively affect bone health and sedative medications increase the risk of fractures, which may lead to detection of osteoporosis,1,2 we included the following covariates in the Cox regression: redemption of at least 1 prescription for a systemic corticosteroid and redemption of at least 1 prescription for a sedative medication (ie, benzodiazepines or hypnotics),27 the Charlson Comorbidity Index that covers 19 chronic diseases,29 and any eating disorder diagnosis (yes or no).24 Here, the redeemed prescriptions stemmed from the year leading up to the index date, while the diagnostic codes stemmed from in- and outpatient contacts at Danish hospitals in the two years leading up to the index date (see the specific ICD-10 and ATC codes in eTable 1 in the Supplement). The association between lithium treatment and osteoporosis was quantified by the unadjusted hazard rate ratio (HRR), a partly adjusted HRR (adjusted for age and sex), and a fully adjusted HRR (adjusted for age, sex, Charlson Comorbidity Index, use of corticosteroids and sedative medication, and eating disorder). As there are substantial sex differences in the incidence of osteoporosis,1,2 we repeated the analyses after stratifying by sex. Sensitivity analyses stratifying on incident and prevalent bipolar disorder and restricting the outcome to osteoporosis with pathological fracture (ICD-10 code M80) are described in the eMethods in the Supplement.

Subsequently, we estimated whether lithium affected the risk of osteoporosis in a dose-response–like manner. For this analysis, we identified all patients with bipolar disorder with an index date in the period from January 1, 1996, to January 1, 2010. In the period from the index date and 5 years forward, the cumulative dose of lithium was calculated using the following formula: dose × number of pills per package / defined daily dose (DDD).28 Patients who died or developed osteoporosis in this 5-year period were excluded. The remaining patients were followed up until osteoporosis, death, or January 1, 2019, whichever came first. The incidence rate of osteoporosis among patients with bipolar disorder receiving lithium treatment was then compared with that of patients with bipolar disorder who did not receive lithium treatment in the period from the index date and 5 years forward. This comparison was made using Cox proportional hazards regression adjusted for age, sex, Charlson Comorbidity Index, use of corticosteroids and sedative medication, and eating disorder, stratified according to the cumulative dose (≤100 DDDs, >100-365 DDDs, >365-730 DDDs, >730-1460 DDDs, and >1460 DDDs). The potential cumulative dose-response association was assessed using the log-rank test (Figure 1C). These analyses were repeated after stratifying by sex.

Finally, all analyses regarding the effect of lithium were repeated while replacing lithium (as exposure) with antipsychotics, valproate, and lamotrigine, respectively (ATC codes in eTable 1 in the Supplement). The lithium, antipsychotics, valproate, and lamotrigine groups were not mutually exclusive, as patients with bipolar disorder are often treated with 2 or more of these drugs concomitantly.6

For all Cox proportional hazards regression analyses, the proportional hazards assumption was confirmed by comparing the log-log survival functions (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). The analyses were conducted using Stata version 15 (StataCorp) via remote access to servers at Statistics Denmark. Tests were 2-sided and significance was set at P < .05.

Results

Characteristics of the Study Population

We identified 22 912 individuals with incident bipolar disorder diagnosed in the period from January 1, 1996, to January 1, 2019 (median [IQR] age, 50.4 [41.2-61.0] years; 12 967 [56.6%] women), and 114 560 reference individuals (median [IQR] age, 50.4 [41.2-61.0] years; 64 835 [56.6%] women). Rates of comorbidities and medication use were higher among patients with bipolar disorder compared with reference individuals. See Table 1 for characteristics of patients and reference individuals and eTable 2 in the Supplement for sex-stratified characteristics.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the Bipolar Disorder Cohort and the Age- and Sex-Matched Reference Cohort.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference individuals (N = 114 560) | Individuals with bipolar disorder, including stratification by treatment | |||||

| Overall (N = 22 912) | Lithium (n = 8750) | Antipsychotics (n = 16 864) | Valproate (n = 3853) | Lamotrigine (n = 7588) | ||

| Age, median (IQR), y | 50.4 (41.2-61.0) | 50.4 (41.2-61.0) | 51.1 (42.9-60.5) | 51.3 (42.8-61.5) | 51.1 (43.0-61.1) | 48.4 (41.1-56.9) |

| Female | 64 835 (56.6) | 12 967 (56.6) | 4942 (56.5) | 9734 (57.7) | 2150 (55.8) | 4636 (61.1) |

| Male | 49 725 (43.4) | 9945 (43.4) | 3808 (43.5) | 7130 (42.3) | 1703 (44.2) | 2952 (38.9) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | ||||||

| 0 | 106 627 (93.1) | 19 618 (85.6) | 7757 (88.7) | 14 380 (85.3) | 3321 (86.2) | 6711 (88.4) |

| 1 | 6208 (5.4) | 2435 (10.6) | 791 (9.0) | 1845 (10.9) | 401 (10.4) | 693 (9.1) |

| 2 | 1725 (1.5) | 859 (3.7) | 202 (2.3) | 639 (3.8) | 131 (3.4) | 184 (2.4) |

| Type of Charlson Comorbidity | ||||||

| Acute myocardial infarction | 471 (0.4) | 150 (0.7) | 34 (0.4) | 104 (0.6) | 22 (0.6) | 34 (0.4) |

| Congestive heart failure | 559 (0.5) | 239 (1.0) | 44 (0.5) | 174 (1.0) | 45 (1.2) | 36 (0.5) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 614 (0.5) | 182 (0.8) | 55 (0.6) | 130 (0.8) | 29 (0.8) | 41 (0.5) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1104 (1.0) | 604 (2.6) | 171 (2.0) | 445 (2.6) | 124 (3.2) | 149 (2.0) |

| Dementia | 207 (0.2) | 191 (0.8) | 52 (0.6) | 152 (0.9) | 27 (0.7) | 33 (0.4) |

| Pulmonary disease | 1426 (1.2) | 681 (3.0) | 194 (2.2) | 518 (3.1) | 78 (2.0) | 178 (2.3) |

| Connective tissue disorder | 609 (0.5) | 191 (0.8) | 64 (0.7) | 153 (0.9) | 29 (0.8) | 55 (0.7) |

| Ulcer | 420 (0.4) | 210 (0.9) | 73 (0.8) | 168 (1.0) | 35 (0.9) | 56 (0.7) |

| Mild liver disease | 287 (0.3) | 226 (1.0) | 53 (0.6) | 168 (1.0) | 27 (0.7) | 55 (0.7) |

| Paraplegia | 63 (0.1) | 21 (0.1) | NAa | 14 (0.1) | NAa | NAa |

| Diabetes | 1264 (1.1) | 616 (2.7) | 185 (2.1) | 464 (2.8) | 106 (2.8) | 173 (2.3) |

| Diabetes with complication | 598 (0.5) | 259 (1.1) | 63 (0.7) | 198 (1.2) | 51 (1.3) | 66 (0.9) |

| Kidney disease | 339 (0.3) | 217 (0.9) | 46 (0.5) | 167 (1.0) | 49 (1.3) | 64 (0.8) |

| Solid tumor | 1815 (1.6) | 491 (2.1) | 161 (1.8) | 373 (2.2) | 73 (1.9) | 127 (1.7) |

| Leukemia | 55 (0) | 21 (0.1) | 7 (0.1) | 13 (0.1) | NAa | NAa |

| Lymphoma | 119 (0.1) | 38 (0.2) | 10 (0.1) | 27 (0.2) | 6 (0.2) | 9 (0.1) |

| Severe liver disease | 60 (0.1) | 54 (0.2) | 12 (0.1) | 39 (0.2) | NAa | 13 (0.2) |

| Metastatic tumor | 191 (0.2) | 60 (0.3) | 15 (0.2) | 44 (0.3) | NAa | 16 (0.2) |

| AIDS | 52 (0) | 31 (0.1) | NAa | 17 (0.1) | NAa | 9 (0.1) |

| Eating disorder | 5 (0) | 49 (0.2) | 12 (0.1) | 33 (0.2) | 7 (0.2) | 20 (0.3) |

| Prior medication | ||||||

| Systemic corticosteroids | 1543 (1.3) | 448 (2.0) | 173 (2.0) | 334 (2.0) | 68 (1.8) | 107 (1.4) |

| Sedatives | 11 523 (10.1) | 11 367 (49.6) | 4693 (53.6) | 9222 (54.7) | 2099 (54.5) | 3974 (52.4) |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Data not reported owing to small numbers.

Association Between Bipolar Disorder and Osteoporosis

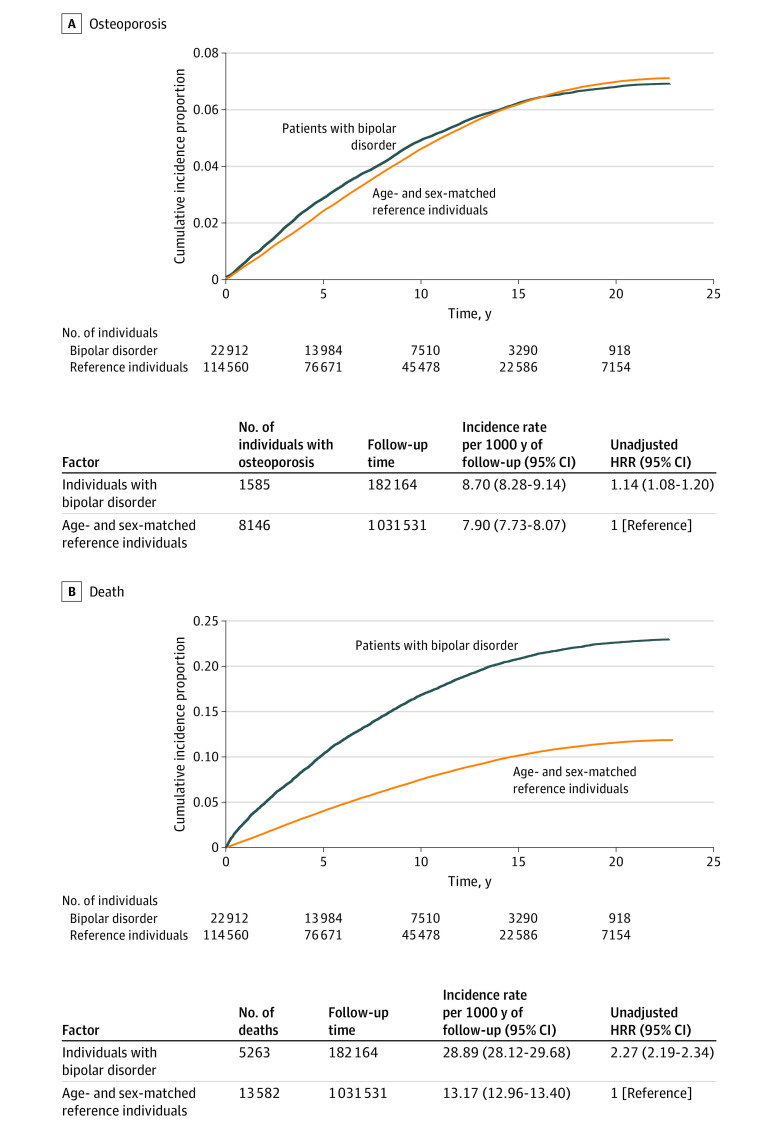

During the 1 213 695 person-years of follow-up (median [IQR] follow-up per person, 7.68 [3.72-13.24] years), 1585 of the patients with bipolar disorder and 8146 of the reference individuals developed osteoporosis according to the operationalization used in this study, corresponding to incidence rates of 8.70 (95% CI, 8.28-9.14) and 7.90 (95% CI, 7.73-8.07) per 1000 person-years, respectively, and an HRR of 1.14 (95% CI, 1.08-1.20). The analyses stratifying the cohort on incident and prevalent bipolar disorder yielded similar results (eTable 3 in the Supplement). The same was the case for the analysis using osteoporosis with pathological fracture as outcome (eTable 4 in the Supplement).

Figure 2A shows that the elevated incidence of osteoporosis among patients with bipolar disorder was particularly pronounced during the first approximately 15 years of follow-up, while the incidence was higher among reference individuals from approximately 16 years of follow-up and onwards. This finding is to be interpreted alongside the results of the post hoc analysis with death as outcome (Figure 2B), suggesting that the substantially increased mortality rate among patients with bipolar disorder may explain the osteoporosis incidence pattern (healthy survivor bias). Specifically, patients with bipolar disorder who remained alive more than 16 years after the initiation of follow-up represent a selected group (eg, healthy lifestyle) with a lower risk of osteoporosis compared with reference individuals that remained alive at this late stage of follow-up.

Figure 2. Aalen-Johansen Curves Showing Crude Cumulative Incidence of Osteoporosis and Death Among Patients With Bipolar Disorder and Age- and Sex-Matched Reference Individuals.

HRR indicates hazard rate ratio.

The results of the sex-stratified comparison of the incidence rate of osteoporosis among patients with bipolar disorder and reference individuals are available in eTable 5 in the Supplement. While the incidence rate was lower among male individuals, the association between bipolar disorder and osteoporosis was particularly pronounced among male individuals (HRR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.26-1.60) compared with female individuals (HRR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.01-1.13).

Lithium Treatment of Bipolar Disorder and the Risk of Developing Osteoporosis

Among patients with bipolar disorder, 8750 (38.2%) received lithium, 16 864 (73.6%) received an antipsychotic, 3853 (16.8%) received valproate, and 7588 (33.1%) received lamotrigine (not mutually exclusive). Characteristics of the patients with bipolar disorder receiving lithium, antipsychotics, valproate, and lamotrigine are shown in Table 1. The treatment overlaps are visualized in eFigures 2, 3, 4, and 5 in the Supplement.

Table 2 lists the results of the analyses investigating the association between lithium treatment of bipolar disorder and osteoporosis. Lithium treatment (compared with no lithium treatment) was associated with a substantial and statistically significant decrease in risk of osteoporosis. This decrease in risk was found both in the model taking treatment duration into account (HRR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.53-0.72) and in the intention-to-treat model (HRR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.71-0.87). Treatment with antipsychotics, valproate, and lamotrigine showed no material or statistically significant association with the risk of osteoporosis in the adjusted models. The analyses stratifying the cohort on incident and prevalent bipolar disorder yielded similar results (eTable 6 in the Supplement), as did the analyses using osteoporosis with pathological fracture as outcome (eTable 7 in the Supplement) and the sex-stratified analyses (eTable 8 in the Supplement).

Table 2. Association Between Lithium, Antipsychotic, Valproate, and Lamotrigine Treatment of Bipolar Disorder and the Risk of Osteoporosis.

| No. of cases of osteoporosis | Follow-up, y | Incidence rate per 1000 person-years (95% CI) | Hazard rate ratio (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Partly adjusteda | Fully adjustedb | ||||

| Lithium | ||||||

| Treatment duration modelc | 217 | 36 297 | 5.98 (5.23-6.83) | 0.65 (0.57-0.76)d | 0.60 (0.52-0.70)d | 0.62 (0.53-0.72)d |

| No lithium use | 972 | 107 142 | 9.07 (8.52-9.66) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Intention-to-treat modele | 613 | 75 022 | 8.17 (7.55-8.84) | 0.81 (0.73-0.90)d | 0.77 (0.69-0.85)d | 0.78 (0.71-0.87)d |

| No lithium use | 972 | 107 142 | 9.07 (8.52-9.66) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Antipsychotics | ||||||

| Treatment duration modelc | 438 | 48 883 | 8.96 (8.16-9.84) | 1.27 (1.10-1.45)d | 1.04 (0.91-1.19) | 1.01 (0.88-1.16) |

| No antipsychotic use | 402 | 55 561 | 7.24 (6.56-7.98) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Intention-to-treat modele | 1183 | 126 603 | 9.34 (8.83-9.89) | 1.19 (1.06-1.33) | 1.03 (0.91-1.15) | 1.00 (0.89-1.13) |

| No antipsychotic use | 402 | 55 561 | 7.24 (6.56-7.98) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Valproate | ||||||

| Treatment duration modelc | 126 | 10 653 | 11.83 (9.93-14.08) | 1.42 (1.19-1.71)d | 1.14 (0.95-1.38) | 1.17 (0.97-1.40) |

| No valproate use | 1292 | 156 083 | 8.28 (7.84-8.74) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Intention-to-treat modele | 293 | 26 082 | 11.23 (10.02-12.60) | 1.26 (1.11-1.44)d | 1.11 (0.98-1.27) | 1.13 (0.99-1.29) |

| No valproate use | 1292 | 156 083 | 8.28 (7.84-8.74) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Lamotrigine | ||||||

| Treatment duration modelc | 195 | 22 907 | 8.51 (7.40-9.80) | 1.04 (0.89-1.21) | 0.98 (0.84-1.14) | 0.99 (0.85-1.16) |

| No lamotrigine use | 1163 | 135 979 | 8.55 (8.08-9.06) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Intention-to-treat modele | 422 | 46 186 | 9.14 (8.31-10.05) | 1.03 (0.92-1.16) | 1.01 (0.90-1.13) | 1.01 (0.91-1.13) |

| No lamotrigine use | 1163 | 135 979 | 8.55 (8.08-9.06) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

Adjusted for age and sex.

Adjusted for age, sex, Charlson Comorbidity Index, use of systemic corticosteroids, use of sedative medication, and eating disorder diagnosis.

Participants were followed up until treatment discontinuation (6 mo after redemption of the last prescription), osteoporosis, death, or January 1, 2019, whichever came first.

Statistically significant results.

Participants were followed up until osteoporosis, death, or January 1, 2019, whichever came first.

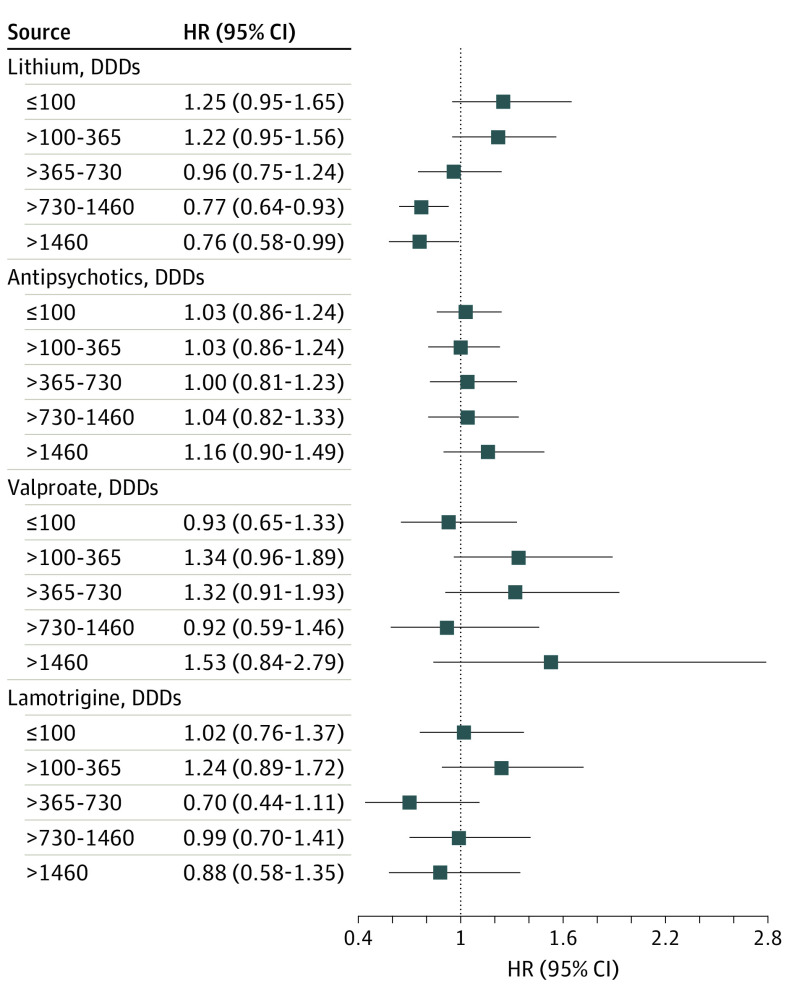

The results of the cumulative dose-response association analyses of lithium, antipsychotics, valproate, and lamotrigine are shown in Figure 3. Here, only lithium treatment corresponding to more than 2 years was associated with a statistically significant decrease in risk of osteoporosis. The higher the cumulative lithium dose, the greater the decrease in risk of osteoporosis (log-rank test P < .001). The sex-stratified analyses yielded similar results (eFigure 6 in the Supplement).

Figure 3. Association Between the Cumulative Dose of Lithium, Antipsychotics, Valproate, and Lamotrigine Treatment of Bipolar Disorder and the Risk of Osteoporosis.

The cumulative dose was calculated based on the period from the index date through the 5 years following. Patients were then followed up from the date 5 years after the index date until osteoporosis, death, or January 1, 2019, whichever came first. The incidence rates of osteoporosis were compared between patients who received treatment (corresponding to the cumulative doses outlined in the figure) and patients who did not, stratified by cumulative dose. The hazard rate ratios (HRR) were adjusted for age, sex, Charlson Comorbidity Index, use of systemic corticosteroids, use of sedative medication, and any eating disorder diagnosis. The P values for the log-rank tests of dose-response associations were as follows: lithium, P < .001; antipsychotics, P = .13; valproate, P = .13; and lamotrigine, P = .30. DDD indicates defined daily dose; HR, hazard ratio.

Discussion

In this nationwide study of 22 912 patients with bipolar disorder and 114 560 age- and sex-matched reference individuals followed up for 1 213 695 person-years, bipolar disorder was associated with an increase in risk of osteoporosis. This finding is consistent with prior reports of increase in risk of fractures,3 low bone mineral density, and osteopenia5 among patients with bipolar disorder. Furthermore, in this study, the association between bipolar disorder and osteoporosis was substantially more pronounced among men than among women. While the data available for the present study do not allow for exploration of this apparent effect modification by sex, it should be addressed in future studies.

We also found that treatment with lithium—unlike treatment with antipsychotics, valproate, and lamotrigine—was associated with a decrease in risk of osteoporosis. This resonates well with prior studies having suggested a potentially bone-protective effect of lithium,17,18 likely mediated by its activation of β-catenin via inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3β.20,21 In this regard, a recent whole-exome sequencing study identified AKAP11 (the gene encoding A-kinase anchoring protein 11) as associated with risk of bipolar disorder.30 At the protein level, AKAP11 interacts with glycogen synthase kinase-3β.31 Hence, the findings of this study are also plausible from a mechanistic perspective.

There are 2 main implications of the results of this study. First, the finding of elevated risk of osteoporosis in bipolar disorder adds to a growing body of evidence suggesting that bone health should be a priority in the clinical management of bipolar disorder.3,12 Specifically, guiding patients toward a lifestyle supporting bone health (no smoking, reduced alcohol consumption, healthy diet, and exercising) and monitoring bone density via dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry scans among those with additional risk factors seems warranted. Second, as new treatment modalities for osteoporosis are sorely needed,1,2 the potential bone protective effect of lithium should be subjected to further study. In this context, the results of an ongoing randomized clinical trial investigating whether lithium increases bone healing in patients with long bone fractures32 will be of great interest.

Limitations

There are limitations to this study. First, quantitative measures of bone health (eg, bone mineral density) were not available to us. However, by defining osteoporosis via hospital discharge diagnoses and prescribed medications, the study outcome should have clinical validity. Second, data on diagnoses assigned prior to the ICD-10 being adopted in Denmark (January 1, 1994) were not available for this study. Hence, the cohort of patients with bipolar disorder is not incident in the strict sense. However, we did ensure that patients were at least 2-year incident, as those registered with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder in the period from January 1, 1994, to December 31, 1995, were not included in the cohort. Third, it cannot be excluded from consideration that there is a healthy user bias associated with lithium treatment owing to the associated blood-testing regimen. On the other hand, as lithium is often used for prevention of manic episodes, patients treated with lithium may be more severely ill compared with those treated with antipsychotics, valproate, and lamotrigine, which would counter a healthy user bias. Fourth, data on pharmacological treatment during inpatient hospital stays are not available in the Danish registers, and this may have affected the calculations of treatment duration. Fifth, data on redemption of prescriptions from Danish pharmacies prior to 1995 are not available via the Danish National Prescription Registry. We therefore have no information on pharmacological treatment from that period. As such, exposure to pharmacological treatment prior to the inception of the Danish National Prescription Registry (eg, those considered as not taking lithium or other mood-stabilizers in the present study may in fact have a history of use [ie, misclassification]) is likely to have added noise in the detection of any true signals, like the apparent association between lithium and decrease in risk of osteoporosis. Sixth, there was a large overlap between the treatment cohorts (eFigures 2, 3, 4, and 5 in the Supplement), which likely also complicates signal detection because of potential interactions between the mood-stabilizing drugs, which may affect the risk of osteoporosis. Yet lithium stood out as the only treatment associated with a substantial and statistically significant decrease in risk of osteoporosis. Seventh, there is a risk of detection bias because bipolar disorder is associated with unintentional injuries33,34 that may increase the likelihood of pathologic fractures due to osteoporosis and their detection. Eighth, information on diet, exercise, alcohol consumption, and smoking, which—from a mediation perspective—is important in the context of osteoporosis, is not available in the Danish registers.

Conclusions

The results of this study suggest that individuals with bipolar disorder were at elevated risk of developing osteoporosis and that lithium treatment was associated with a reduction in this risk. These findings suggest that bone health should be a priority in the clinical management of bipolar disorder and that the potential bone-protective properties of lithium should be subjected to further study, both in the context of bipolar disorder and in osteoporosis.

eMethods. Description of sensitivity analyses

eTable 1. Definition of variables

eTable 2. Baseline characteristics of the cohort

eTable 3. Association between bipolar disorder and osteoporosis stratified by incident/prevalent bipolar disorder status

eTable 4. Association between bipolar disorder and osteoporotic fractures

eTable 5. Association between bipolar disorder and osteoporosis stratified by sex

eTable 6. Association between treatments of bipolar disorder and osteoporosis stratified by incident/prevalent bipolar disorder status

eTable 7. Association between treatments of bipolar disorder and osteoporotic fractures

eTable 8. Association between treatments of bipolar disorder and osteoporosis stratified by sex

eFigure 1. Log-log survival functions (time to osteoporosis) confirming proportional hazards

eFigure 2. Venn diagram showing the overlap between lithium treatment and other treatments

eFigure 3. Venn diagram showing the overlap between antipsychotic treatment and other treatments

eFigure 4. Venn diagram showing the overlap between lamotrigine treatment and other treatments

eFigure 5. Venn diagram showing the overlap between valproate treatment and other treatments

eFigure 6. Association between the duration of lithium, antipsychotic, valproate and lamotrigine treatment of bipolar disorder and the risk of osteoporosis stratified by sex

References

- 1.Compston JE, McClung MR, Leslie WD. Osteoporosis. Lancet. 2019;393(10169):364-376. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32112-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eastell R, O’Neill TW, Hofbauer LC, et al. Postmenopausal osteoporosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16069. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chandrasekaran V, Brennan-Olsen SL, Stuart AL, et al. Bipolar disorder and bone health: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2019;249:262-269. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li S, Qui Y, Teng Z, et al. Association between bipolar disorder and low bone mass: a cross-sectional study with newly diagnosed, drug-naïve patients. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:530. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo P, Wang S, Zhu Y, et al. Prevalence of osteopenia and osteoporosis and factors associated with decreased bone mineral density in elderly inpatients with psychiatric disorders in Huzhou, China. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2012;24(5):262-270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Köhler-Forsberg O, Gasse C, Hieronymus F, et al. Pre-diagnostic and post-diagnostic psychopharmacological treatment of 16 288 patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pedersen CB, Mors O, Bertelsen A, et al. A comprehensive nationwide study of the incidence rate and lifetime risk for treated mental disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(5):573-581. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kupka RW, Altshuler LL, Nolen WA, et al. Three times more days depressed than manic or hypomanic in both bipolar I and bipolar II disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9(5):531-535. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00467.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Behrendt-Moller I, Madsen T, Sorensen HJ, et al. Patterns of changes in bipolar depressive symptoms revealed by trajectory analysis among 482 patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2019;21(4):350-360. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(6):530-537. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.6.530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly RR, McDonald LT, Jensen NR, Sidles SJ, LaRue AC. Impacts of psychological stress on osteoporosis: clinical implications and treatment interactions. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:200. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cizza G, Primma S, Coyle M, Gourgiotis L, Csako G. Depression and osteoporosis: a research synthesis with meta-analysis. Horm Metab Res. 2010;42(7):467-482. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1252020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnston CB, Dagar M. Osteoporosis in older adults. Med Clin North Am. 2020;104(5):873-884. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2020.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cade JF. Lithium salts in the treatment of psychotic excitement. 1949. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(4):518-520. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20(2):97-170. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rhee TG, Olfson M, Nierenberg AA, Wilkinson ST. 20-Year trends in the pharmacologic treatment of bipolar disorder by psychiatrists in outpatient care settings. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(8):706-715. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.19091000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bolton JM, Metge C, Lix L, Prior H, Sareen J, Leslie WD. Fracture risk from psychotropic medications: a population-based analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28(4):384-391. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31817d5943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vestergaard P, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L. Reduced relative risk of fractures among users of lithium. Calcif Tissue Int. 2005;77(1):1-8. doi: 10.1007/s00223-004-0258-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu B, Wu Q, Zhang S, Del Rosario A. Lithium use and risk of fracture: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Osteoporos Int. 2019;30(2):257-266. doi: 10.1007/s00198-018-4745-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen Y, Whetstone HC, Lin AC, et al. Beta-catenin signaling plays a disparate role in different phases of fracture repair: implications for therapy to improve bone healing. PLoS Med. 2007;4(7):e249. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clément-Lacroix P, Ai M, Morvan F, et al. LRP5-independent activation of Wnt signaling by lithium chloride increases bone formation and bone mass in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(48):17406-17411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505259102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong SK, Chin KY, Ima-Nirwana S. The skeletal-protecting action and mechanisms of action for mood-stabilizing drug lithium chloride: current evidence and future potential research areas. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:430. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pedersen CB. The Danish civil registration system. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):22-25. doi: 10.1177/1403494810387965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mors O, Perto GP, Mortensen PB. The Danish psychiatric central research register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):54-57. doi: 10.1177/1403494810395825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmidt M, Schmidt SA, Sandegaard JL, Ehrenstein V, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. The Danish National Patient Registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:449-490. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S91125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization . The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Diagnostic Criteria for Research. World Health Organization; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pottegård A, Schmidt SAJ, Wallach-Kildemoes H, Sørensen HT, Hallas J, Schmidt M. Data resource profile: the Danish National Prescription Registry. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(3):798-798f. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization . ATC/DDD index 2022. Accessed April 24, 2021. https://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/

- 29.Charlson ME, Charlson RE, Peterson JC, Marinopoulos SS, Briggs WM, Hollenberg JP. The Charlson comorbidity index is adapted to predict costs of chronic disease in primary care patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(12):1234-1240. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palmer DS, Howrigan DP, Chapman SB, et al. Exome sequencing in bipolar disorder reveals shared risk gene AKAP11 with schizophrenia. medRxiv. Preprint posted March 26, 2021. doi: 10.1101/2021.03.09.21252930 [DOI]

- 31.Tanji C, Yamamoto H, Yorioka N, Kohno N, Kikuchi K, Kikuchi A. A-kinase anchoring protein AKAP220 binds to glycogen synthase kinase-3beta (GSK-3beta) and mediates protein kinase A-dependent inhibition of GSK-3beta. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(40):36955-36961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206210200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nam D, Balasuberamaniam P, Milner K, et al. Lithium for Fracture Treatment (LiFT): a double-blind randomised control trial protocol. BMJ Open. 2020;10(1):e031545. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen VC, Yang YH, Lee CP, et al. Risks of road injuries in patients with bipolar disorder and associations with drug treatments: a population-based matched cohort study. J Affect Disord. 2018;226:124-131. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.09.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Plana-Ripoll O, Pedersen CB, Agerbo E, et al. A comprehensive analysis of mortality-related health metrics associated with mental disorders: a nationwide, register-based cohort study. Lancet. 2019;394(10211):1827-1835. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32316-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Description of sensitivity analyses

eTable 1. Definition of variables

eTable 2. Baseline characteristics of the cohort

eTable 3. Association between bipolar disorder and osteoporosis stratified by incident/prevalent bipolar disorder status

eTable 4. Association between bipolar disorder and osteoporotic fractures

eTable 5. Association between bipolar disorder and osteoporosis stratified by sex

eTable 6. Association between treatments of bipolar disorder and osteoporosis stratified by incident/prevalent bipolar disorder status

eTable 7. Association between treatments of bipolar disorder and osteoporotic fractures

eTable 8. Association between treatments of bipolar disorder and osteoporosis stratified by sex

eFigure 1. Log-log survival functions (time to osteoporosis) confirming proportional hazards

eFigure 2. Venn diagram showing the overlap between lithium treatment and other treatments

eFigure 3. Venn diagram showing the overlap between antipsychotic treatment and other treatments

eFigure 4. Venn diagram showing the overlap between lamotrigine treatment and other treatments

eFigure 5. Venn diagram showing the overlap between valproate treatment and other treatments

eFigure 6. Association between the duration of lithium, antipsychotic, valproate and lamotrigine treatment of bipolar disorder and the risk of osteoporosis stratified by sex