This cohort study investigates the frequency of COVID-19 booster vaccination among individuals with schizophrenia in Israel compared with those without schizophrenia.

Key Points

Question

Do individuals with schizophrenia receive the booster vaccination to the same extent as do individuals without schizophrenia?

Findings

In this cohort study of 34 797 individuals with schizophrenia and matched controls, individuals with schizophrenia were less likely to be vaccinated with the COVID-19 booster vaccine, and gaps in vaccination remained the largest for the first vaccination. Time to reach vaccination was significantly longer for the group with schizophrenia but primarily with the first vaccine and to a smaller extent with the booster vaccine.

Meaning

Study results suggest that for individuals with schizophrenia, the main barrier to COVID-19 vaccination was during the initiation phase.

Abstract

Importance

Individuals with schizophrenia are at higher risk for severe COVID-19 illness and mortality. Previous reports have demonstrated vaccination gaps among this high-risk population; however, it is unclear whether these gaps have continued to manifest with the booster dose.

Objective

To assess gaps in first, second, and booster vaccinations among individuals with schizophrenia.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This was a matched, controlled, retrospective cohort study conducted in November 2021, and included follow-up data from March 2020, to November 2021. The study used the databases of Clalit Health Services, the largest health care management organization in Israel. Individuals with a diagnosis of schizophrenia at the onset of the pandemic and matched controls were included in the analysis.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Rates of first, second, and booster vaccinations and time to reach vaccination.

Results

The study included 34 797 individuals (mean [SD] age, 50.8 [16.4] years; 20 851 men [59.9%]) with schizophrenia and 34 797 matched controls (mean [SD] age, 50.7 [16.4] years; 20 851 men [59.9]) for a total of 69 594 individuals. A total of 6845 of 33 045 individuals (20.7%) with schizophrenia were completely unvaccinated, compared with 4986 of 34 366 (14.5%) in the control group (odds ratio [OR], 0.65; 95% CI, 0.62-0.67, P < .001). Once vaccinated, no significant differences were observed in the uptake of the second vaccine. Gaps emerged again with the booster vaccine, with 18 469 individuals (74.7%) with schizophrenia completing the booster, compared with 21 563 (77.9%) in the control group (OR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.80-0.87, P < .001). Kaplan-Meier analyses indicated significant differences in time to reach vaccination, although gaps were lower compared with those reported in the first vaccination (log-rank test, 601.99 days; P < .001 for the first vaccination, compared with log-rank test, 81.48 days, P < .001 for the booster). Multivariate Cox regression analyses indicated that gaps in the first and booster vaccine were sustained even after controlling for demographic and clinical variables (first vaccine: hazard ratio [HR], 0.80; 95% CI, 0.78-0.81; P < .001 and booster: HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.87-0.90; P < .001) but were not significant for the second vaccine.

Conclusions and Relevance

Results of this cohort study of Israeli adults found lower rates of COVID-19 vaccination among individuals with schizophrenia compared with a control group without schizophrenia, especially during the vaccine initiation phase. Countries worldwide should adopt strategies to mitigate the persistence of vaccination gaps to improve health care for this vulnerable population.

Introduction

Individuals with schizophrenia are one of the most vulnerable groups at risk for a severe course of COVID-19 infection.1,2 Although such a risk calls for immediate preventive strategies, recent studies have suggested that individuals with schizophrenia and psychotic disorders are either vaccinated to a lesser extent or tend to decline COVID-19 vaccination to a greater extent, compared with the general population.3,4 Nonetheless, to the best of our knowledge, no study has thus far examined whether these gaps were sustained with the launch of national booster plans worldwide or whether they differ from those reported in the first and second vaccination. In this study, we explored vaccination trends among individuals with schizophrenia since the onset of Israel's vaccination plan in December 2020 and up to 3 months after the launch of the booster vaccine plan by July 2021. Based on previous reports,3 we hypothesized that gaps between individuals with schizophrenia and the general population would continue to emerge with the booster vaccine.

Methods

Data Source and Study Population

This cohort study was approved by the Clalit Health Services institutional review board, and a waiver of informed consent was granted owing to the use of deidentified patient data. Patient data were obtained from the databases of Clalit Health Services, which is the largest of 4 operating health care organizations to provide health care to all of Israel’s citizens5 and includes service provision to more than 50% of the country’s population.6 Data on race and ethnicity were not collected as these are not common terms used in Israel. The databases are regularly updated with clinical information from medical facilities. The algorithms used to develop the chronic registry were previously validated by its developers.7 Data for the current study were mined at the end of November 2021. All individuals with an active diagnosis of schizophrenia at the onset of the pandemic were extracted and matched randomly to age and sex controls with no diagnosis of schizophrenia. Matching was performed at a 1:1 ratio. Schizophrenia diagnosis was based on registration by a senior psychiatrist or when listed on a psychiatric hospital discharge letter.3,8 The diagnosis was previously examined for its validity and found to be 94% accurate.9 The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines.

Statistical Analyses

Univariate logistic regressions were used to assess gaps in the frequency of each vaccination. Estimated projections of the cumulative probability were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier analysis. The log-rank test was used to estimate differences in survival time. Hazard ratios (HRs) were calculated to assess incidence rates while adjusting for demographic and clinical risk factors previously associated with vaccination uptake,10 including socioeconomic status, sector (ie, population group), marital status, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and ischemic heart disease. Significance level was set at P < .05, and all P values were 2-sided. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software, version 25 (SPSS).

Results

The study included 34 797 individuals (mean [SD] age, 50.8 [16.4] years; 20 851 men [59.9%]; 13 946 women [40.1%]) with schizophrenia and 34 797 matched controls (mean [SD] age, 50.7 [16.4] years; 20 851 men [59.9%]; 13 946 women [40.1%]) for a total of 69 594 individuals. Compared with the control group, individuals with schizophrenia were more likely to be from a low (odds ratio [OR], 1.97; 95% CI, 1.88-2.06) or medium (OR, 1.93; 95% CI, 1.85-2.02; P < .001) socioeconomic status, more likely to be from the Ultraorthodox Jewish population (OR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.41-1.73; P < .001), less likely to belong to the Arab population (OR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.62-0.68; P < .001), and less likely to be married (OR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.19-0.20; P < .001). Compared with the control group, individuals with schizophrenia were more likely to have diabetes (OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.57-1.69; P < .001), hypertension (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.00-1.07; P = .03), hyperlipidemia (OR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.35-1.43; P < .001), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (OR, 2.45; 95% CI, 2.26-2.66; P < .001), obesity (OR, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.59-1.70; P < .001), and to smoke (OR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.57-1.66; P < .001), and were less likely to be diagnosed with ischemic heart disease (OR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.75-0.85; P < .001) (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Study Sample (N = 69 594).

| Characteristic | No. (%) | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schizophrenia | Control | |||

| No. | 34 797 | 34 797 | NA | NA |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 50.77 (16.43) | 50.67 (16.41) | NA | NA |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 20 851 (59.9) | 20 851 (59.9) | NA | NA |

| Female | 13 946 (40.1) | 13 946 (40.1) | NA | NA |

| Socioeconomic status (high)a | ||||

| Low | 15 386 (44.2) | 13 794 (39.7) | 1.97 (1.88-2.06) | <.001 |

| Medium | 14 464 (41.6) | 13 240 (38.0) | 1.93 (1.85-2.02) | <.001 |

| High | 4209 (12.1) | 7453 (21.4) | 1 [Reference] | |

| Sector (general)a | ||||

| Arab | 4386 (12.6) | 6343 (18.2) | 0.65 (0.62-0.68) | <.001 |

| Ultraorthodox | 1034 (3.0) | 626 (1.8) | 1.56 (1.41-1.73) | <.001 |

| General | 29 377 (84.4) | 27 828 (80.0) | 1 [Reference] | |

| Marital status (married)a | ||||

| Married | 7380 (21.2) | 19 903 (57.2) | 0.20 (0.19-0.20) | <.001 |

| Other | 27 417 (78.8) | 14 894 (42.8) | ||

| Smokingb | 18 499 (53.2) | 14 336 (41.2) | 1.62 (1.57-1.66) | <.001 |

| Obesity | 12 118 (34.8) | 8532 (24.5) | 1.64 (1.59-1.70) | <.001 |

| Diabetes | 8032 (23.1) | 5406 (15.5) | 1.63 (1.57-1.69) | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 7855 (22.6) | 7611 (21.9) | 1.04 (1.00-1.07) | .03 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 17 229 (49.5) | 14 374 (41.3) | 1.39 (1.35-1.43) | <.001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 2092 (6.0) | 883 (2.5) | 2.45 (2.26-2.66) | <.001 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 2187 (6.3) | 2187 (6.3) | 0.80 (0.75-0.85) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio.

Reference group is specified in parentheses. Socioeconomic status levels are determined by the Central Bureau of Statistics in Israel.

Reference group is not having the disease.

Individuals with schizophrenia were significantly less likely to be vaccinated with the first vaccine, with 6845 of 33 045 unvaccinated individuals (20.7%) in the schizophrenia group, compared with 4986 of 34 366 (14.5%) in the control group (OR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.62-0.67; P < .001) (Table 2). Once receiving the first vaccination, no significant differences in uptake of the second vaccination were found (OR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.95-1.10; P = .43). Of those receiving the second vaccination, significant differences were again found between the groups (OR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.80-0.87; P < .001), with 18 469 of 24 738 individuals (74.7%) completing the third vaccination in the schizophrenia group, compared with 21 563 of 27 695 (77.9%) in the control group.

Table 2. Odds Ratio (OR) (95% CI) and Significance of Differences in Frequencies of Vaccinations Across the First, Second, and Booster Dosesa.

| Vaccination | No. (%) | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schizophrenia | Control | |||

| No. | 33 045 | 34 366 | NA | NA |

| First vaccination | ||||

| Vaccinated | 26 200 (79.3) | 29 380 (85.5) | 0.65 (0.62-0.67) | <.001 |

| Not vaccinated | 6845 (20.7) | 4986 (14.5) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Second vaccination | ||||

| Completed 2 vaccinations | 24 738 (94.4) | 27 695 (94.3) | 1.02 (0.95-1.10) | .43 |

| Did not continue to second vaccination | 1462 (5.6) | 1685 (5.7) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Booster/third vaccination | ||||

| Completed 3 vaccinations | 18 469 (74.7) | 21 563 (77.9) | 0.83 (0.80-0.87) | <.001 |

| Did not receive booster | 6269 (25.3) | 6132 (22.1) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio.

Deceased individuals (n = 2183 [3.1%]) were excluded from this analysis.

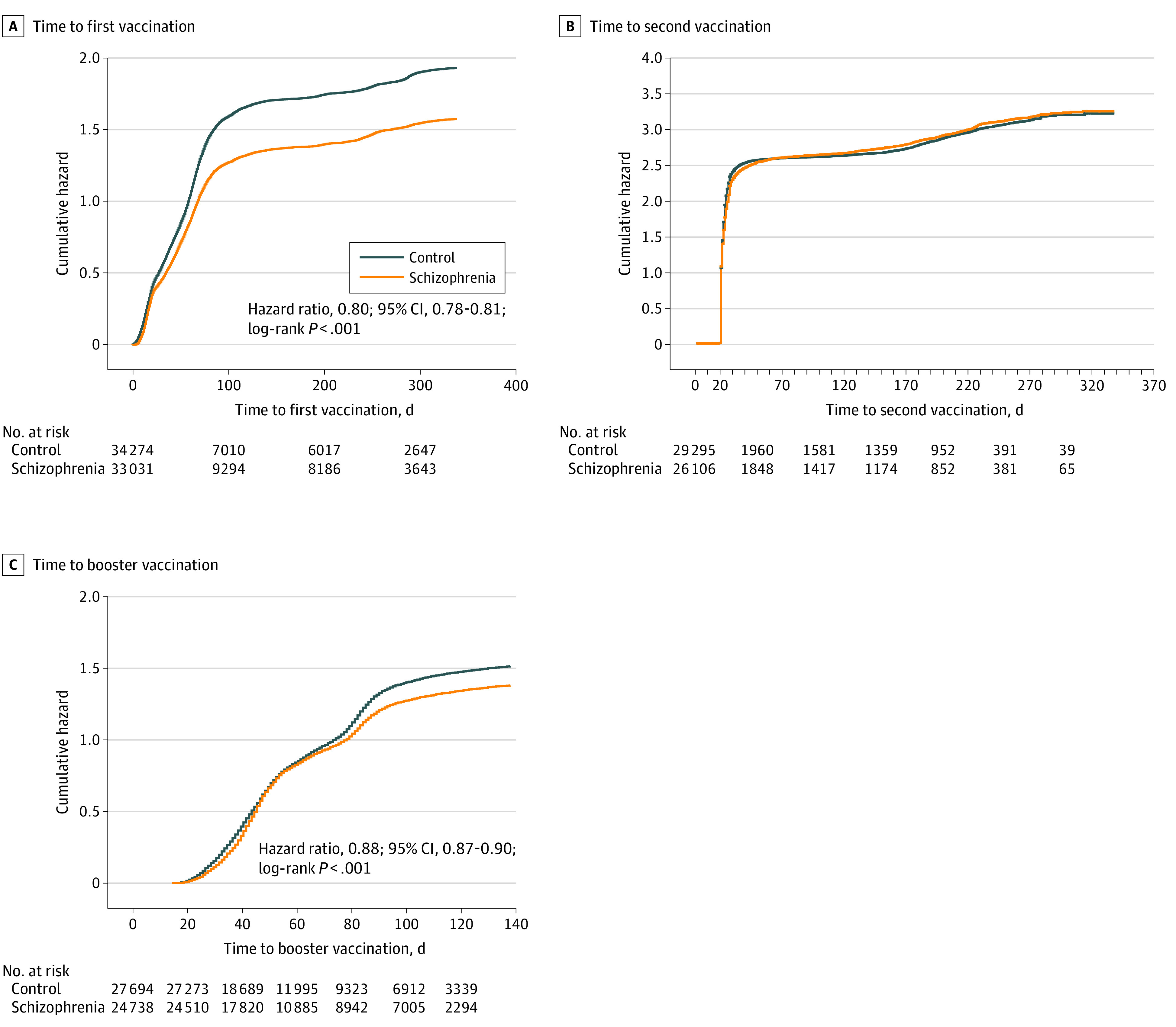

Kaplan-Meier analyses (Figure) indicated that time to vaccination was longer for the schizophrenia group, with a mean (SE) survival time of 115.61 (2.32) days, compared with 89.38 (0.62) days in the control group. Median (IQR) time was 49 (18-194) days in the schizophrenia group and 40 (16-76) days for the control group (log-rank test, 601.99; P < .001). Among those receiving the first vaccination, time to second vaccination was slightly shorter among the schizophrenia group, with a mean (SE) time of 40.65 (0.43) days, compared with 42.02 (0.45) days in the control group, and with the same median (IQR) time of 21 (21-22) days across the 2 groups (log-rank test, 6.00; P = .004). Among those receiving 2 vaccinations, time to booster vaccination was longer in the schizophrenia group, with a mean (SE) of 73.49 (0.31) days, compared with 70.21 (0.27) days in the control group and with a median (IQR) time of 51 (38-51) days in the schizophrenia group, compared with 50 (35-99) days in the control group (log-rank test, 81.48; P < .001).

Figure. Kaplan-Meier Curves for the Cumulative Probability of Being Vaccinated Among Individuals With Schizophrenia and Controls .

Figure panels represent time to first (A), second (B), and booster (C) vaccination.

Proportional hazard analyses indicated that individuals with schizophrenia presented a lower probability to be vaccinated with the first vaccine after controlling for demographic and clinical characteristics (HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.78-0.81; P < .001). No significant differences in probability to be vaccinated with the second dose were found between the groups after adjustment (HR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.96-1.00; P = .06). For the booster vaccination, individuals with schizophrenia presented a lower probability to be vaccinated, even after adjustment (HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.87-0.90; P < .001).

Discussion

The findings reported in this cohort study suggest that vaccination gaps were significant and persistent. Only a few studies have thus far examined vaccination coverage among individuals with severe mental illness. The OpenSAFELY collaborative group reported that vaccination coverage was substantially lower among individuals with severe mental illness in the UK.11 Nonetheless, a recent study4 from the UK reported that individuals with severe mental illness were significantly more likely to be vaccinated, although they also presented higher odds of declining vaccinations, particularly individuals with psychotic disorders. Additional studies are needed to further assess these cross-cultural differences and how they relate to governmental policies.

Individuals with schizophrenia completed the second vaccination to the same extent as did the control group. These findings may be associated with the regimen of vaccine administration in Israel, which was based on 2 doses of the BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) messenger RNA COVID-19 vaccine, spaced 21 days apart.12 As all individuals receiving first vaccination were instructed to complete the second dose of vaccination at 21 days, it is possible that these instructions facilitated its completion.

Individuals with schizophrenia were less likely to be vaccinated with the booster shot. The reemergence of gaps may be associated with the debate regarding the necessity of the booster13 and may suggest that challenges to vaccination among this population are located in the initiation phase. Several solutions have been offered to mitigate barriers to vaccination, such as the provision of education by a health care professional and of transportation to clinics.14 These solutions should be considered for both first and booster vaccinations. Current prioritization efforts are not sufficient to close the gaps in preventive care for people with mental illness,15 and novel preventive strategies should be developed to narrow these gaps.

Limitations

Study limitations include the inability to control for COVID-19 variants and severity of the mental disorder. Future studies should also explore causal factors which may have led to the observed gaps, such as access to preventive medicine and factors related to communication, transportation, and stigma.

Conclusions

This cohort study of Israeli adults found lower rates of COVID-19 vaccination among individuals with schizophrenia compared with a control group without schizophrenia and that the main barrier to COVID-19 vaccination was during the initiation phase. Countries worldwide should adopt strategies to mitigate the persistence of vaccination gaps in order to improve health care for this vulnerable population.

References

- 1.Fond G, Nemani K, Etchecopar-Etchart D, et al. Association between mental health disorders and mortality among patients with COVID-19 in 7 countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(11):1208-1217. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.2274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vai B, Mazza MG, Delli Colli C, et al. Mental disorders and risk of COVID-19-related mortality, hospitalisation, and intensive care unit admission: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(9):797-812. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00232-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tzur Bitan D. Patients with schizophrenia are undervaccinated for COVID-19: a report from Israel. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(2):300-301. doi: 10.1002/wps.20874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hassan L, Sawyer C, Peek N, et al. COVID-19 vaccination uptake in people with severe mental illness: a UK-based cohort study. World Psychiatry. 2022;21(1):153-154. doi: 10.1002/wps.20945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ministry of Health . Israel National Health Insurance Law. Article in Hebrew. Accessed January 28, 2022. https://www.health.gov.il/LegislationLibrary/Bituah_01.pdf

- 6.Ministry of Health . Annual report of health care–providing companies for 2018. Article in Hebrew. Accessed January 28, 2022. https://www.health.gov.il/PublicationsFiles/dochHashvaatui2018.pdf

- 7.Rennert G, Peterburg Y. Prevalence of selected chronic diseases in Israel. Isr Med Assoc J. 2001;3(6):404-408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tzur Bitan D, Krieger I, Kridin K, et al. COVID-19 prevalence and mortality among schizophrenia patients: a large-scale retrospective cohort study. Schizophr Bull. 2021;47(5):1211-1217. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbab012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tzur Bitan D, Krieger I, Berkovitch A, Comaneshter D, Cohen A. Chronic kidney disease in adults with schizophrenia: a nationwide population-based study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2019;58:1-6. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2019.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tzur Bitan D, Kridin K, Cohen AD, Weinstein O. COVID-19 hospitalisation, mortality, vaccination, and postvaccination trends among people with schizophrenia in Israel: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(10):901-908. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00256-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curtis HJ, Inglesby P, Morton CE, et al. Trends and clinical characteristics of COVID-19 vaccine recipients: a federated analysis of 57.9 million patients’ primary care records in situ using OpenSAFELY. medRxiv. Preprint posted online April 9, 2021. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.01.25.21250356v3.full [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Haas EJ, Angulo FJ, McLaughlin JM, et al. Impact and effectiveness of mRNA BNT162b2 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 infections and COVID-19 cases, hospitalisations, and deaths following a nationwide vaccination campaign in Israel: an observational study using national surveillance data. Lancet. 2021;397(10287):1819-1829. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00947-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burki T. Booster shots for COVID-19-the debate continues. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(10):1359-1360. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00574-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warren N, Kisely S, Siskind D. Maximizing the uptake of a COVID-19 vaccine in people with severe mental illness: a public health priority. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(6):589-590. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.4396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Picker LJ. Closing COVID-19 mortality, vaccination, and evidence gaps for those with severe mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(10):854-855. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00291-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]