Abstract

Background:

The evidence base for understanding hospice use among persons with dementia is almost exclusively based on individuals with a primary terminal diagnosis of dementia. Little is known about whether comorbid dementia influences hospice use patterns.

Objective:

To estimate the prevalence of comorbid dementia among hospice enrollees and its association with hospice use patterns.

Design:

Pooled cross-sectional analysis of the nationally representative Health and Retirement Study (HRS) linked to Medicare claims.

Subjects:

Fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries in the United States who enrolled with hospice and died between 2004 and 2016.

Measurements:

Dementia was assessed using a validated survey-based algorithm. Hospice use patterns were enrollment less than or equal to three days, enrollment greater than six months, hospice disenrollment, and hospice disenrollment after six months.

Results:

Of 3123 decedents, 465 (14.9%) had a primary hospice diagnosis of dementia and 943 (30.2%) had comorbid dementia and died of another illness. In fully adjusted models, comorbid dementia was associated with increased odds of hospice enrollment greater than six months (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 1.52, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.11–2.09) and hospice disenrollment following six months of hospice (AOR = 2.55, 95% CI: 1.43–4.553). Having a primary diagnosis of dementia was associated with increased odds of hospice enrollment greater than six months (AOR = 2.62, 95% CI: 1.86–3.68), hospice disenrollment (AOR = 1.82, 95% CI: 1.32–2.51), and hospice disenrollment following six months of hospice (AOR = 4.31, 95% CI: 2.37–7.82).

Conclusion:

Approximately 45% of the hospice population has primary or comorbid dementia and are at increased risk for long hospice enrollment periods and hospice disenrollment. Consideration of the high prevalence of comorbid dementia should be inherent in hospice staff training, quality metrics, and Medicare Hospice Benefit policies.

Keywords: comorbidity, dementia, end of life, health services research, hospice

Introduction

Persons with a primary diagnosis of dementia and their families have increasingly enrolled with hospice to receive interdisciplinary support at the end of life. As of 2018, an estimated 16% of hospice enrollees have dementia as their primary terminal diagnosis.1 Yet numerous studies indicate that the Medicare Hospice Benefit (MHB) is a poor fit for those with dementia.2–9 The MHB was envisioned primarily for the care of people with advanced cancer and thus key elements of the benefit are not optimal for those with a primary diagnosis of dementia. For example, MHB eligibility requires a life expectancy of six months or less, and yet prognosis in the setting of dementia is notoriously unpredictable.10–13 Even for persons with a primary diagnosis of dementia who enroll with hospice, their patterns of hospice use include high rates of hospice disenrollment, very long enrollment periods, and high rates of disenrollment after long enrollment periods.2,4–6

Our understanding of hospice use among those with dementia, however, is almost exclusively based on individuals with a primary terminal diagnosis of dementia. This is because an individual's primary hospice diagnosis is required for Medicare payment and is thus reliably included on Medicare hospice claims. Little is known about hospice use patterns for those with comorbid dementia whose primary hospice diagnosis is another illness, including cancer or heart failure. This is a significant omission, given an estimated 41% of all Medicare decedents are suffering from early- or late-stage dementia.14 We hypothesize that although MHB enrollment is based on a patient's primary terminal illness, comorbid dementia adds substantial complexity to both prognosis (and thus eligibility for hospice) as well as care decisions. Very long hospice enrollment periods for those with comorbid dementia may indicate that although the patient/family has extensive home-based care needs and comfort-focused goals of care, their prognosis may be more than six months. Similarly, hospice disenrollment may indicate that individuals with comorbid dementia need additional home-based support, but hospice may not have been the right mix of services. In addition to these possible direct impacts, comorbid dementia may also influence care decisions in differential ways specific to a person's primary terminal illness or socioeconomic circumstances.

To address this gap, we use data from the nationally representative Health and Retirement Study (HRS)15 to examine differences in hospice use patterns between those with comorbid dementia and those with a primary hospice diagnosis of dementia. Use of HRS data also enables the examination of socioeconomic characteristics and functional impairment that are often omitted from existing studies.

Methods

Study sample and data sources

The HRS is a national longitudinal study of adults 51 years of age and older in the contiguous United States funded by the National Institute on Aging (grant number NIA U01AG009740) and the Social Security Administration and conducted by the University of Michigan since 1992. Serial interviews are done every two years and response rates for each interview wave have exceeded 86%. These interviews include detailed questions on the participant's demographic and social characteristics, functional and cognitive status, medical information, caregiving needs and hours of support, and financial information. The HRS also completes post-death interviews with a knowledgeable proxy. HRS obtains consent from respondents with fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare to link to their Medicare Claims data.

Our sample comprised HRS participants who died between 2004 and 2016 and who received hospice care (n = 8813). To have 2 years of complete Medicare claims data, we excluded respondents younger than 67 years at the time of death (n = 589) and persons without linked FFS Medicare claims (n = 905). In addition, we excluded persons missing key data elements from a post-death interview (n = 401) or final core interview before death (n = 284). Of the remaining 6634 decedents, our final sample included 3123 decedents who enrolled with hospice.

Measures

Dementia status

Following established methods, we assessed all subjects' probability of dementia using a clinically validated algorithm, which models probability of dementia on individuals' responses to a battery of cognitive and functional measures and demographic data drawn from the last available HRS survey assessment, on average 12 months before death.16–18 A primary hospice diagnosis of dementia was identified from the Medicare hospice claims. Subjects identified as having dementia (based on probability score >0.5), but who did not have dementia as a primary hospice diagnosis, were categorized as having comorbid dementia. All other subjects were classified as not having dementia.

Hospice use patterns

We identified length of hospice enrollment and hospice disenrollment from the Medicare hospice claim file defined as follows: enrollment three or fewer days before death, enrollment greater than six months, disenrollment from hospice, and disenrollment from hospice after six months.

Patient characteristics

We obtained the following demographic measures from HRS: age at last core interview, gender, education, race, and ethnicity. We also assessed the following time-variant measures at the final core interview before death: marital status, requiring assistance with at least one of six Activity of Daily Living (ADL), self-rated health, Medicaid status, count of self-reported comorbidities, presence of a helper with any Instrumental Activity of Daily Living (IADL) or ADL, and net worth. We identified nursing home residence from the post-death exit interview. We identified the primary hospice diagnosis from the Medicare hospice claims and categorized as dementia, cancer, heart failure, and other (which includes all other possible diagnoses, the most common being chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, and stroke).

Analysis

In this pooled cross-sectional study, we examined bivariate relationships between dementia status (primary hospice diagnosis of dementia, comorbid dementia, and no dementia) and each of our hospice use patterns using chi-squared tests and t-tests, as appropriate. We used multivariable logistic regression to estimate adjusted odds ratios (AORs) between dementia status and each outcome controlling for age, race, ethnicity, sex, education, marital status, ADL impairment, self-rated health, Medicaid, nursing home resident, primary diagnoses, and year of interview. We excluded net worth from the multivariable models due to its moderate positive correlation (r = 0.43) with Medicaid status. We excluded presence of a helper with any IADL or ADL from the multivariable models due to its strong positive correlation with having at least one ADL (r = 0.75). We examined potential interaction effects of specific primary hospice diagnoses (cancer and heart failure) and comorbid dementia, as well as interaction effects of dementia and low socioeconomic status (as measured by education and Medicaid eligibility). We estimated the predicted probability of each hospice use pattern adjusting for all measured covariates.

We performed analyses using Stata software, version 16 (StataCorp). All analyses were adjusted using survey weights to account for the complex survey design and sampling approach. All reported p-values are two sided with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant. This study was approved by the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai's Institutional Review Board.

Results

Our sample consisted of 3123 decedents who used hospice, among whom 14.9% had a primary hospice diagnosis of dementia, 30.2% had comorbid dementia, and 54.9% had no dementia. Compared to those without dementia, those with comorbid dementia tended to be significantly older and more likely to be non-Hispanic black or Hispanic, more likely to have not graduated from high school, and more likely to report poor/fair self-reported health (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Medicare Decedents Who Enrolled with Hospice, by Dementia Status, 2004–2016

| Total Sample N = 3123 | Dementia status |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary hospice diagnosis of dementia N = 465 | Comorbid dementia N = 943 | No dementia N = 1715 | ||

| Age (mean, standard deviation) | 82.8 (7.2) | 85.5** (7.0) | 86.8** (7.3) | 79.9 (7.8) |

| Race | ||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 11.5 | 14.0** | 15.5** | 8.7 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 6.0 | 7.7** | 7.4** | 4.7 |

| Female | 58.6 | 69.9** | 65.1** | 52.0 |

| Education | ** | ** | ||

| Less than high school | 31.3 | 33.3 | 42.4 | 24.5 |

| High school degree | 52.2 | 50.3 | 46.6 | 55.8 |

| Some college | 2.8 | 2.6 | 1.9 | 3.3 |

| College degree | 8.3 | 8.4 | 4.7 | 10.3 |

| Graduate degree | 5.5 | 5.4 | 4.5 | 6.1 |

| Unmarried | 61.9 | 70.3** | 71.4** | 54.3 |

| Low net worth | 23.1 | 32.7** | 32.6** | 15.2 |

| Self-rated health | ** | ** | ||

| Poor/fair | 62.6 | 67.2 | 68.1 | 58.3 |

| Good | 23.0 | 19.8 | 20.5 | 25.1 |

| Very good/excellent | 14.4 | 12.9 | 11.4 | 16.5 |

| ADL impairment | 47.6 | 76.3** | 73.7** | 25.5 |

| Medicaid eligible | 18.6 | 27.5** | 28.4** | 11.0 |

| Any helper(s) | 61.7 | 88.4** | 88.8** | 39.7 |

| Comorbidities | * | ** | ||

| 0 | 5.1 | 3.6 | 4.0 | 6.0 |

| 1–3 | 65.6 | 67.1 | 58.3 | 69.2 |

| 4 or more | 29.3 | 29.3 | 37.7 | 24.8 |

| Nursing home resident | 43.2 | 67.3** | 55.4** | 29.9 |

| Primary hospice diagnosis | ||||

| Cancer | 31.3 | 0.0** | 18.3** | 47.0 |

| Heart failure | 10.0 | 0.0** | 12.9 | 11.1 |

| Other | 43.7 | 0.0** | 68.7** | 41.9 |

p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 compared to the no dementia group.

Low net worth is defined as those in the lowest quartile for net worth (adjusted to 2012 dollars).

Comorbidities: measured as self-reported diagnosis of cancer, lung disease, heart condition, CHF, stroke, memory disease, hypertension, diabetes, and psychiatric condition.

ADL, Activity of Daily Living.

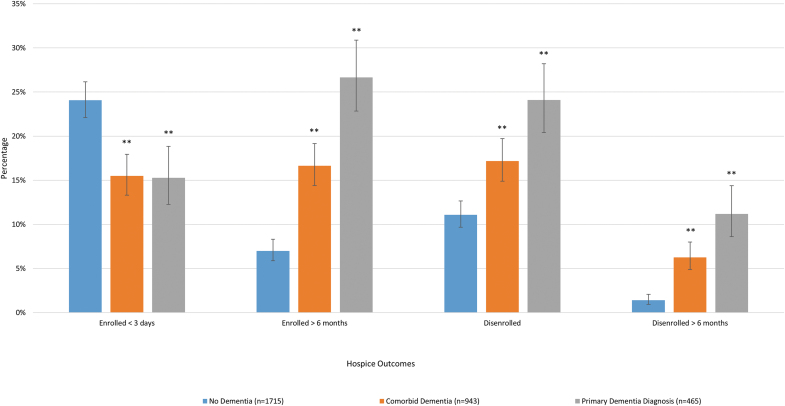

The overall mean and median lengths of hospice enrollment were 83.5 and 16.0 days, respectively. For those with a primary hospice diagnosis of dementia, mean and median lengths of hospice enrollment were 167.8 and 39.0 days; for those with comorbid dementia, 103.5 and 23.0 days; and for those without dementia, 49.7 and 12.0 days. A total of 20.5% of our sample had hospice care for three or fewer days and 12.8% had hospice care for more than six months. Hospice disenrollment at any time point was 14.9% and disenrollment following more than six months with hospice care was 4.3% (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Title: Hospice Use Patterns By Dementia Status, 2004–2016 Source: authors' analyses of HRS data for FFS Medicare beneficiaries in the United States, who enrolled with hospice and died between 2004 and 2016. **p < 0.01 in comparison to the no dementia group. FFS, fee for service; HRS, Health and Retirement Study. Color image is available online.

In adjusted analyses, those with comorbid dementia had higher odds than those with no dementia of enrolling with hospice for more than six months (AOR = 1.52; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.11–2.09), and hospice disenrollment following six months with hospice (AOR = 2.55; 95% CI: 1.43–4.53) and lower odds of three or fewer days in hospice (AOR = 0.73; 95% CI: 0.56–0.94) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics Associated with Hospice Use Patterns, N = 3123

| Enrollment ≤3 days |

Enrollment >6 months |

Hospice disenrollment |

Hospice disenrollment After 6 months |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |||||

| Dementia status | ||||||||

| Primary hospice diagnosis of dementia | 0.73 (0.53–1.00) | * | 2.62 (1.86–3.68) | ** | 1.82 (1.32–2.51) | ** | 4.31 (2.37–7.82)** | |

| Comorbid dementia | 0.73 (0.56–0.94) | * | 1.52 (1.11–2.09) | ** | 1.19 (0.89–1.58) | 2.55 (1.43–4.53)** | ||

| No dementia | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Age | 1.00 (0.98–1.01) | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | 1.01 (0.98–1.04) | ||||

| Race | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.00 (0.74–1.36) | 1.09 (0.77–1.54) | 1.60 (1.18–2.17) | ** | 1.46 (0.87–2.47) | |||

| White/other | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Hispanic ethnicity | 0.92 (0.61–1.39) | 0.62 (0.37–1.06) | 0.96 (0.61–1.50) | 1.01 (0.47–2.15) | ||||

| Female | 0.66 (0.54–0.80) | ** | 1.22 (0.94–1.60) | 1.03 (0.81–1.31) | 1.34 (0.85–2.11) | |||

| Education | ||||||||

| More than high school | 1.19 (0.96–1.48) | 0.90 (0.70–1.17) | 1.01 (0.79–1.28) | 0.89 (0.58–1.36) | ||||

| Less than high school | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Unmarried | 1.15 (0.93–1.41) | 1.12 (0.84–1.48) | 1.04 (0.80–1.33) | 1.07 (0.66–1.74) | ||||

| Self-rated health | ||||||||

| Poor/fair | 0.84 (0.69–1.03) | 1.90 (1.44–2.51) | ** | 1.43 (1.12–1.81) | ** | 2.26 (1.37–3.72)** | ||

| Good/very good/excellent | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| ADL impairment | 0.80 (0.64–0.99) | * | 2.19 (1.63–2.93) | ** | 1.26 (0.98–1.62) | 2.31 (1.35–3.93)** | ||

| Medicaid eligible | 1.14 (0.87–1.48) | 1.24 (0.93–1.66) | 1.42 (1.09–1.86) | * | 1.14 (0.73–1.80) | |||

| Comorbidities | ||||||||

| 4+ | 1.06 (0.67–1.69) | 0.88 (0.45–1.69) | 0.78 (0.47–1.30) | 0.77 (0.26–2.30) | ||||

| 1–3 | 1.29 (0.84–1.99) | 1.02 (0.54–1.92) | 0.73 (0.46–1.18) | 0.93 (0.32–2.68) | ||||

| 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Nursing home resident | 1.08 (0.89–1.33) | 1.04 (0.82–1.33) | 1.09 (0.87–1.37) | 1.05 (0.70–1.56) | ||||

| Year | 1.00 (0.98–1.03) | 1.05 (1.01–1.08) | ** | 0.96 (0.93–0.99) | ** | 1.03 (0.98–1.09) | ||

p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

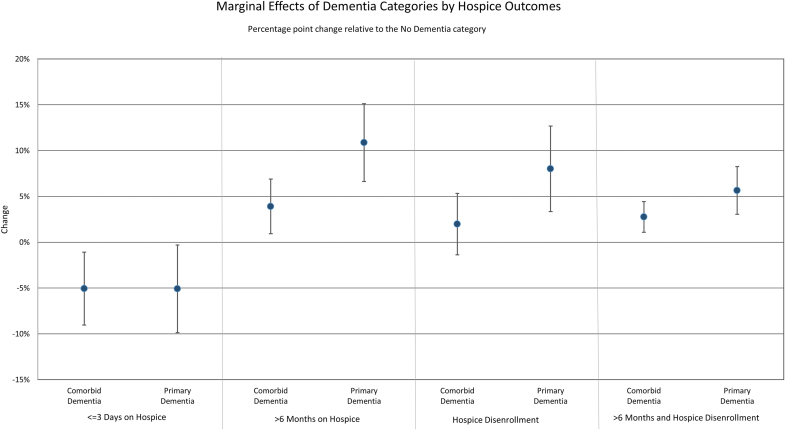

With the exception of very short hospice enrollment periods (≤3 days), the differences in the predicted probabilities of each outcome were twice as large for those with a primary hospice diagnosis of dementia (vs. no dementia) than for those with comorbid dementia (vs. no dementia). For example, the predicted probability of hospice disenrollment for those with a primary diagnosis of dementia was 20.8%, those with comorbid dementia was 14.7%, and those without dementia was 12.7% (resulting in marginal differences compared to those without dementia of 8.1% and 2.0% points, respectively) (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Title: Marginal Effect of Dementia on Hospice Use Patterns, 2004–2016 Source: authors' analyses of HRS data for FFS Medicare beneficiaries in the United States, who enrolled with hospice and died between 2004 and 2016. This figure depicts the difference in the adjusted probability of each hospice use pattern in comparison to those without dementia. Color image is available online.

Interaction effects between comorbid dementia and socioeconomic status and comorbid dementia and heart failure were not significantly associated with study outcomes. Interaction effects between comorbid dementia and cancer were not significantly associated with enrollment greater than six months, hospice disenrollment, or hospice disenrollment after six months, but were associated with higher likelihood of hospice enrollment for three or fewer days before death (AOR = 1.81; CI: 1.05–3.10) (results not shown).

Discussion

This is the first national study of which we are aware to estimate the prevalence of comorbid dementia among hospice enrollees. We found that almost one-third of individuals who enroll with hospice are suffering from comorbid dementia, while dying of another serious illness. Given the significant challenges of caring for individuals with dementia as they approach the end of life,10,19–22 our findings have important implications for both hospice teams and MHB policies.

Numerous studies and reports indicate that ∼15% of individuals enrolled with hospice have dementia as the primary terminal diagnosis.1,2 Our findings confirm this proportion with terminal dementia and add that approximately one-third have comorbid dementia, revealing that upwards of 45% of the hospice population has dementia. Because persons with dementia (those with either terminal or comorbid dementia) often have care needs and a trajectory of decline that are distinct from other serious illnesses, these findings have important implications for hospice teams. Specifically, most persons with dementia have significant need for assistance with basic daily activities and managing behavioral symptoms, and for caregiver support.20,23 Hospice teams may need additional dementia-focused training themselves to build this expertise. Caregivers also may benefit from targeted education for managing behavioral symptoms and guidance for strategies to cope with caregiver strain. And while pain management is often as critical for persons with dementia as it is for persons with cancer at end of life, persons with dementia may require different assessment tools for measuring pain and other symptoms. Furthermore medications frequently used in hospice, such as antipsychotics, may be contraindicated or require tailored protocols for use in persons with dementia.24,25

Some hospices have begun developing dementia-specific practices and programs to accommodate persons with dementia,9,26 yet how widely these programs are employed and their effectiveness are unknown. Researchers and policy makers could address these gaps by collecting data on dementia-specific practices in hospices, mandating that hospice staff undergo training in dementia care, and requiring that hospices collect dementia-specific quality measures. For example, the Family Evaluation of Hospice Care (FEHC) survey27 that is sent to bereaved family members of hospice enrollees could include an item about whether the hospice recipient had dementia at the time of death and whether the hospice provided dementia-specific counseling and treatments.

We also found that those with comorbid dementia have similar patterns of hospice use as those with a primary hospice diagnosis of dementia, although the magnitude of effects differs. This suggests that having dementia significantly influences decisions regarding hospice enrollment and disenrollment for people with and without another life-limiting illness. Patients with comorbid dementia have an ∼4% point higher probability (CI: 0.01–0.07) of hospice enrollment over six months compared to those without dementia, rising to a 10% point higher probability (CI: 0.07–0.16) for those with a principal diagnosis of dementia.

There are a few possible reasons why hospice use patterns are similar in direction, but different in magnitude between those with comorbid versus primary dementia. One reason is that the presence of a comorbid dementia diagnosis may strongly influence a person's goals of care and lead them to enroll in hospice earlier in the course of another disease, compared to others without dementia.28 Challenges with accurate prognostication in the setting of dementia can also lead to earlier hospice enrollment.11 When dementia is present, in addition to another terminal illness, a person's prognosis may be shorter or more predictable, and thus, providers may be more likely to refer these individuals to hospice. In both the case of primary and comorbid dementia, hospice may be viewed as providing care assistance for the many care needs of persons with dementia, which are otherwise poorly met by existing benefits, even when there is prognostic uncertainty. For hospice organizations, there have been financial incentives to enroll those with a primary diagnosis of dementia, whose longer period of enrollment and lower acuity result in increased profit margins.29–32 More research is needed to understand the reasons underlying our observed hospice use patterns in comorbid and primary dementia, particularly from the perspective of patients, families, and providers.

From a policy perspective, increased use of hospice by those with a primary hospice diagnosis of dementia and the associated longer average lengths of stay are central to the debate regarding increasing costs of the MHB program.3 In recent years, Medicare has implemented a number of policy and payment changes to try to contain costs, essentially by discouraging initial or continued enrollment of persons with dementia. For example, as part of the Affordable Care Act, Medicare began requiring that hospices have a “face-to-face” encounter with each hospice beneficiary to assess continued hospice eligibility at the beginning of the third benefit period (i.e., at six months following hospice enrollment) and at the beginning of every benefit period thereafter. Similarly, 2016 Hospice Payment Reform was specifically designed to de-incentivize long hospice enrollment periods by reducing payments to hospices after 60 days on service.33 Given our finding that both those with a primary hospice diagnosis of dementia and comorbid dementia are more likely to have hospice enrollment periods longer than six months, this acts as a specific barrier to remaining enrolled with hospice for persons with dementia.

Although payment reform policies may reduce Medicare hospice expenditures and reduce enrollment of marginally eligible persons with dementia by some profit-motivated hospices, it is important to ensure that these changes do not result in more burdensome transitions for persons with dementia and that persons with dementia still have access to high-quality end-of-life care. The end-of-life experience is often very stressful for persons with dementia and their caregivers,19 who face significant challenges navigating hospice services in conjunction with a complex array of health and long-term care services. Given our finding that persons with a primary diagnosis of dementia are more likely to experience disenrollment from hospice, which fragments care and leaves patients and families scrambling,34 policy makers should weigh the costs and benefits of policies that may restrict initial or continuing enrollment in hospice for persons with a primary diagnosis of dementia.

These considerations are especially important, given the fact that other services to support persons with dementia who are approaching end of life and their caregivers are still often piecemeal, insufficient, or not available nationwide.35 Although alternatives to the hospice model for end-of-life care such as home-based serious illness care and dementia care management programs have grown in recent years,36,37 these programs still serve relatively few persons with dementia.38 The MHB, on the other hand, is a well-established, well-recognized model of care with high utilization by persons with dementia. As federal regulation and payment policies for hospice continue to evolve, regulators should consider approaches that maintain access to hospice for persons with dementia and work to integrate hospice into emerging alternative care models to better meet the needs of persons with dementia and their caregivers.

A limitation to this study is that we used Medicare hospice claims data to identify individuals with a primary hospice diagnosis of dementia. Using Medicare claims to identify individuals with dementia has the potential for misdiagnosis by providers entering the claim, including missed diagnoses and incorrectly attributed diagnoses.39 However, a number of studies have found that using Medicare claims to identify dementia has relatively robust sensitivity and specificity.40,41 In our case, we only used Medicare claims data to identify individuals with a primary hospice diagnosis of dementia and used the HRS data to identify people with comorbid dementia. Because there are strict criteria for designating dementia as a primary hospice diagnosis42 (e.g., stage 7C on the FAST Scale, weight loss, and/or aspiration pneumonia as some key criteria), it is less likely that these individuals are mis-specified compared to other approaches to identifying individuals with dementia using Medicare claims. In addition, our use of the HRS algorithm to identify those with comorbid dementia may have either missed or incorrectly identified those with comorbid dementia. However, the HRS algorithm was validated against a gold-standard neuropsychiatric assessment within the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study16,18 finding sensitivity of 78% and specificity of 90%.16 This method closely approximates current guidelines for clinical diagnosis of dementia.43

Conclusion

Almost half of the hospice patient population suffers from dementia, underscoring the need for hospice organizations and regulators to ensure that hospice care is tailored to the needs of persons with dementia and their caregivers. As federal regulation and payment policies for hospice continue to evolve, regulators must move beyond punitive approaches that may restrict access to hospice for persons with dementia and consider the integration of hospice into emerging care models to better meet the needs of people both dying with and from dementia.

Sponsor's Role

Funders played no role in the study's design, methods, data collection, analysis, and preparation of the article.

Authors' Contributions

All authors were involved in the study concept and design. All authors were involved in analysis and interpretation of data. All authors were involved in preparation of article.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

NIA R01AG054540 and NIA K24AG062785 (Kelley); NINR R01 NR018462 and NIA K07 AG060270 (Aldridge); Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center; KL2 TR001870 and National Palliative Care Research Center Career Development Award (Hunt); and NIA PO1 AG066605 (Aldridge, Kelley).

References

- 1. National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. NHPCO Facts and Figures: Hospice Care in America. https://www.nhpco.org/wp-content/uploads/NHPCO-Facts-Figures-2020-edition.pdf (Accessed December 15, 2020).

- 2. De Vleminck A, Morrison RS, Meier DE, Aldridge MD: Hospice care for patients with dementia in the United States: A longitudinal cohort study. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2018;19:633–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aldridge MD, Bradley EH: Epidemiology and patterns of care at the end of life: Rising complexity, shifts in care patterns and sites of death. Health Aff (Millwood) 2017;36:1175–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Miller SC, Lima J, Gozalo PL, Mor V: The growth of hospice care in U.S. nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:1481–1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Miller SC, Lima JC, Mitchell SL: Hospice care for persons with dementia: The growth of access in US nursing homes. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2010;25:666–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Miller SC, et al. : Hospice care for patients with dementia. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007;34:7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Unroe KT, Meier DE: Quality of hospice care for individuals with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013;61:1212–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Luth EA, Russell DJ, Brody AA, et al. : Race, ethnicity, and other risks for live discharge among hospice patients with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020;68:551–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Harrison KL, Allison TA, Garrett SB, et al. : Hospice staff perspectives on caring for people with dementia: A multisite, multistakeholder study. J Palliat Med 2020;23:1013–1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. : The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1529–1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mitchell SL, Miller SC, Teno JM, et al. : Prediction of 6-month survival of nursing home residents with advanced dementia using ADEPT vs hospice eligibility guidelines. JAMA 2010;304:1929–1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Luchins DJ, Hanrahan P, Murphy K: Criteria for enrolling dementia patients in hospice [see comments]. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997;45:1054–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Luchins DJ, Hanrahan P: What is appropriate health care for end-stage dementia? J Amer Geriatr Soc 1993;41:25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Aldridge MD, Ornstein KA, McKendrick K, et al. : Trends in residential setting and hospice use at the end of life for medicare decedents. Health Aff (Millwood) 2020;39:1060–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Health and Retirement Study: Produced and distributed by the University of Michigan with funding from the National Institute on Aging (grant number NIA U01AG009740) and the Social Security Administration. Ann Arbor, MI, 2002–2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hurd MD, Martorell P, Delavande A, et al. : Monetary costs of dementia in the United States. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1326–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kelley AS, McGarry K, Gorges R, Skinner JS: The burden of health care costs for patients with dementia in the last 5 years of life. Ann Intern Med 2015;163:729–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Plassman B, Langa K, Fisher G, et al. : Prevalence of dementia in the United States: The aging, demographics, and memory study. Neuroepidemiology 2007;29:125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vick JB, Ornstein KA, Szanton SL, et al. : Does caregiving strain increase as patients with and without dementia approach the end of life? J Pain Symptom Manage 2019;57:199–208 e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. van der Steen JT: Dying with dementia: What we know after more than a decade of research. J Alzheimers Dis 2010;22:37–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Malhotra C, Hazirah M, Tan LL, et al. : Family caregiver perspectives on suffering of persons with severe dementia: A qualitative study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2021;62:20–27.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sachs GA, Shega JW, Cox-Hayley D: Barriers to excellent end-of-life care for patients with dementia. J Gen Intern Med 2004;19:1057–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ellis-Smith C, Evans CJ, Murtagh FE, et al. : Development of a caregiver-reported measure to support systematic assessment of people with dementia in long-term care: The Integrated Palliative care Outcome Scale for Dementia. Palliat Med 2017;31:651–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. While C, Jocelyn A: Observational pain assessment scales for people with dementia: A review. Br J Commun Nurs 2009;14:438., 439–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015;63:2227–2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Brody AA, Guan C, Cortes T, Galvin JE: Development and testing of the Dementia Symptom Management at Home (DSM-H) program: An interprofessional home health care intervention to improve the quality of life for persons with dementia and their caregivers. Geriatr Nurs 2016;37:200–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Connor SR, Teno J, Spence C, Smith N: Family evaluation of hospice care: Results from voluntary submission of data via website. J Pain Symptom Manage 2005;30:9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Griffiths AW, Ashley L, Kelley R, et al. : Decision-making in cancer care for people living with dementia. Psychooncology 2020;29:1347–1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wachterman MW, Marcantonio ER, Davis RB, McCarthy EP: Association of hospice agency profit status with patient diagnosis, location of care, and length of stay. JAMA 2011;305:472–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Aldridge Carlson MD, Barry CL, Cherlin EJ, et al. : Hospices' enrollment policies may contribute to underuse of hospice care in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:2690–2698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Aldridge MD, Schlesinger M, Barry CL, et al. : National hospice survey results: For-profit status, community engagement, and service. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:500–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Aldridge MD, Canavan M, Cherlin E, Bradley EH: Has hospice use changed? 2000–2010 Utilization patterns. Med Care 2015;53:95–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. MedPac: Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy: Chapter 12: Hospice Services, Washington DC, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wladkowski SP: Dementia caregivers and live discharge from hospice: What happens when hospice leaves? J Gerontol Soc Work 2017;60:138–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shuman SB, Hughes S, Wiener JM, Gould E: Research on care needs and supportive approaches for persons with dementia. RTI International, 2017. US Department of Health and Human Services, https:/aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/research-care-needs-and-supportive-approaches-persons-dementia.

- 36. Jennings LA, Turner M, Keebler C, et al. : The effect of a comprehensive dementia care management program on end-of-life care. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67:443–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Major-Monfried H, DeCherrie LV, Wajnberg A, et al. : Managing pain in chronically ill homebound patients through home-based primary and palliative care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2019;36:333–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Harrison KL, Leff B, Altan A, et al. : What's happening at home: A claims-based approach to better understand home clinical care received by older adults. Med Care 2020;58:360–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhu CW, Ornstein KA, Cosentino S, et al. : Misidentification of dementia in medicare claims and related costs. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018;67:269–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Taylor DH Jr., Fillenbaum GG, Ezell ME: The accuracy of medicare claims data in identifying Alzheimer's disease. J Clin Epidemiol 2002;55:929–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Taylor DH Jr., Ostbye T, Langa KM, et al. : The accuracy of Medicare claims as an epidemiological tool: The case of dementia revisited. J Alzheimers Dis 2009;17:807–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Local Coverage Determination: Hospice Alzheimer's Disease & Related Disorders (L34567); https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/lcd-details.aspx?LCDId=34567. (Accessed July 15, 2021).

- 43. McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. : The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dementia 2011;7:263–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]