Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by a recently discovered coronavirus called severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The disease affected well over a hundred million people all over the world and mortality rates were greater in the elderly population. The quick development of safe and effective vaccines represents an important step in the management of the ongoing pandemic and, so far, four vaccines have been approved by the European Medicines Agency, including mRNA (Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna) and adenovirus-based vaccines (AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson).

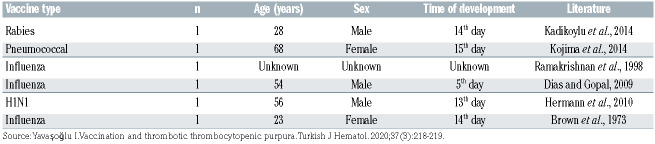

Immune-mediated thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) is a rare disease (annual incidence between 1.5 and 6.0 cases per million)1 characterized by microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia and ischemic end-organ injury due to microvascular plateletrich thrombi. The formation of microvascular thrombi is caused by a deficiency of ADAMTS13, a von Willebrand factor-cleaving protease, due to the presence of anti- ADAMTS13 autoantibodies.2 Cases of immune-mediated TTP following the administration of vaccines have been previously described and recently reviewed (Table 1).3 However, only one case of newly diagnosed immunemediated TTP following COVID-19 vaccination has been reported in the literature: it occurred in a 62-year-old female patient 37 days after receiving the adenovirusbased AstraZeneca vaccine.4 Additinoally, a case of immune-mediated TTP relapse was recently described in a 48-year-old female patient after the second dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine.5 Here we report two cases of immune-mediated TTP following the first dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. Informed consent was obtained from the patients regarding the report of their clinical scenarios.

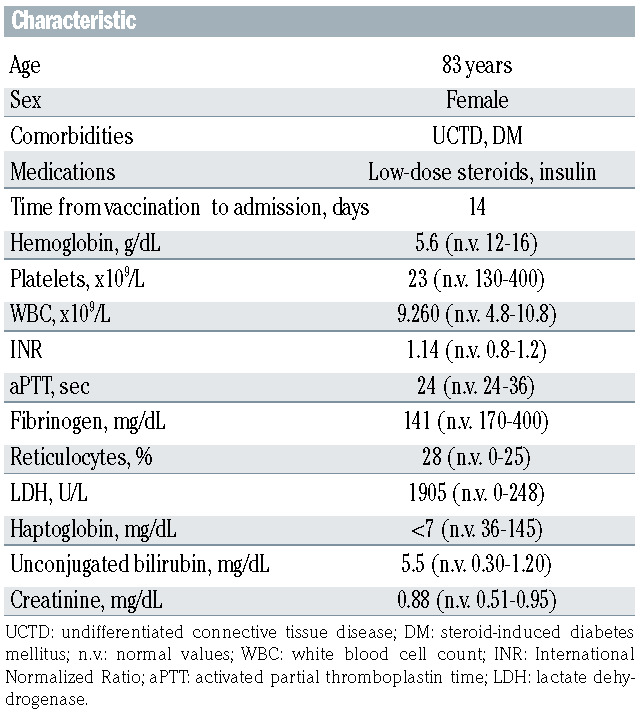

Case 1. In April 2021, an 83-year-old female patient was admitted to the emergency room with severe anemia and macrohematuria, in the absence of fever, neurological signs and renal impairment. On clinical examination, diffuse petechiae and venipuncture hematomas were observed. The patient suffered from undifferentiated connective tissue disease treated with low-dose steroids and steroid-induced diabetes mellitus. The woman had been administered the first dose of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine 14 days prior to the admission. One week before the admission, the patient was treated briefly at another center because of fatigue and the appearance of petechiae. A complete blood count revealed grade 3 anemia (hemoglobin 6.1 g/dL) and thrombocytopenia (platelet count 46x109/L), requiring transfusion support. However, the patient refused hospital admission and was discharged. Seven days later, on admission to our center, the complete blood count again showed severe anemia (hemoglobin 5.6 g/dL) and thrombocytopenia (platelet count 23x109/L) with a normal white blood cell count. Markers of hemolysis were present, including increased reticulocytes, increased lactate dehydrogenase (1905 U/L, normal values [n.v:] 0-248), increased unconjugated bilirubin (5.5 mg/dL, n.v: 0.30-1.20) and reduced haptoglobin (<7 mg/dL) (Table 2). Coagulation and renal function tests were within normal limits. Both direct and indirect antiglobulin tests were negative. Examination of a peripheral blood smear revealed an increased number of schistocytes (10% per field). The PLASMIC score (6 points) classified the patient as being at high risk of severe ADAMTS13 deficiency. 6 Tumor markers and infectious screening for hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, human immunodeficiency virus, cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus resulted negative. Autoimmunity screening revealed the presence of anti-nuclear antibodies (titer 1:640, n.v. <1:80). A rapid ADAMTS13 test was performed demonstrating markedly reduced activity (below 10%) with a high titer of anti- ADAMTS13 antibodies according to enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in serum (40 U/mL, n.v. 12-15), thus confirming the diagnosis of immune-mediated TTP. The patient was promptly started on intravenous methylprednisolone 1 mg/kg and daily sessions of plasma exchange in combination with the humanized antivon Willebrand factor nanobody, caplacizumab. Caplacizumab was administered intravenously at the dose of 10 mg before the first plasma-exchange, followed by 10 mg subcutaneous injections after each plasmaexchange. The patient was transfused with several units of concentrated red blood cells. After an initial clinical benefit with resolution of hematuria and early signs of hematologic recovery with a platelet count of 30x109/L, the patient died after only 2 days of treatment, probably due to a sudden cardiovascular event.

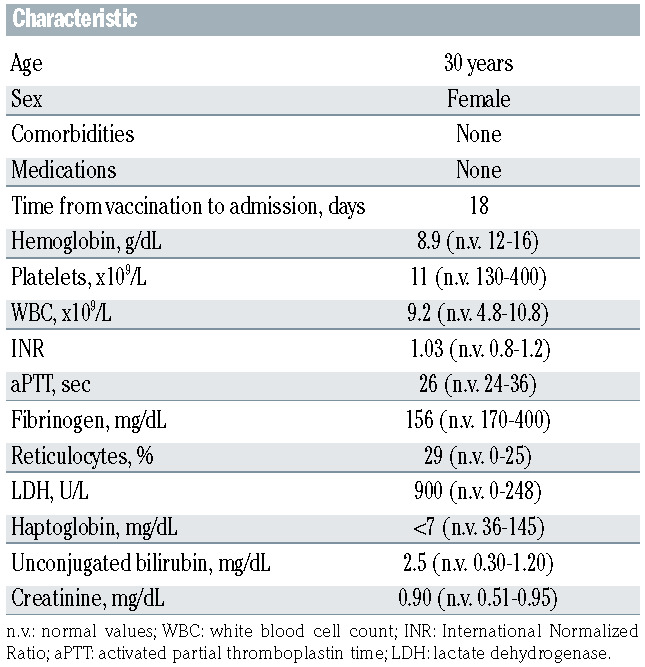

Case 2. In June 2021, a 30-year-old woman, a b-thalassemia carrier, was admitted to the emergency room because of the appearance of diffuse petechiae, intense headache and fatigue. The patient had received her first dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine 18 days before the admission. On admission, a complete blood count revealed the presence of anemia (hemoglobin 8.9 g/dL) and thrombocytopenia (platelet count 11x109/L), with a normal white blood cell count (9.2x109/L). Total body computed tomography was negative. A peripheral blood smear showed the presence of schistocytes (5-10% per field). Investigations for hemolysis were positive, while both direct and indirect Coombs tests were negative. Coagulation, hepatic and renal function tests were all within normal limits (Table 3). Tumor markers, autoimmune and infectious screening resulted negative. The PLASMIC score (6 points) classified the patient as high risk A rapid ADAMTS13 test revealed reduced activity (below 10%), while a high titer of anti-ADAMTS 13 antibodies was confirmed by ELISA (77.6 U/mL; n.v. 12-15). The woman was treated promptly with daily sessions of plasma exchange in combination with caplacizumab and intravenous methylprednisolone 1 mg/kg, and responded well to treatment. Her platelet count normalized on day 5 (platelet count, 158x109/L) with a hemoglobin value of 8.1 g/dL. Daily plasma exchange was continued for 8 consecutive days and she was discharged on day 8. On day 14 and on day 30 ADAMTS13 activity was 0 U/mL (n.v. 0.4-1.3), while anti- ADAMTS13 antibody titer progressively reduced, being 47 U/mL and 30 U/mL on day 14 and on day 30, respectively. The patient continued therapy with caplacizumab for 30 days after stopping daily plasma-exchange treatment.

Table 1.

Cases of immune-mediated thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura following the administration of vaccines.

Table 2.

Case 1: clinical and laboratory characteristics at diagnosis.

Table 3.

Case 2: clinical and laboratory characteristics at diagnosis.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of newly diagnosed immune-mediated TTP following the first dose of COVID-19 Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine. Immune-mediated TTP was not mentioned among the adverse events in the pivotal study leading to the approval of this vaccine.7 Given the immune origin of the TTP and the short latency period between the COVID- 19 vaccine and disease onset, a hypothesized temporal association is plausible. Although many cases of immune-mediated TTP following vaccinations have been reported previously, including those following influenza, pneumococcal, rabies and a recently published COVID- 19 adenovirus vector-based vaccines,3-8,10 the underlying mechanism is still unknown. In our first case, the patient also suffered from undifferentiated connective tissue disorder, an autoimmune disease that might have been a predisposing factor to post-vaccination TTP. In the literature, there is evidence of vaccine-induced autoimmunity, adjuvant-induced autoimmunity and antibody crossreaction in both experimental models as well as human patients.8 Furthermore, other cases of immune-mediated disease onset or its flare were described after COVID-19 vaccination,9-11 including cases of post-vaccination immune thrombocytopenic purpura.12,13 A lot of attention has recently been given to the thrombotic risk of COVID-19 vaccination. In particular, a new syndrome called vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT) following administration of the adenovirus- based vaccine AstraZeneca has been described. This syndrome is characterized by thrombosis at unusual sites, thrombocytopenia and the presence of high levels of antibodies to platelet factor 4 (PF4) in the absence of heparin treatment.14 In our cases, another disease characterized by an increased thrombotic risk developed following administration of an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. Furthermore, the clinical cases we have described confirm that even a single administration of vaccine can induce the development of autoimmune manifestations especially in predisposed subjects. The consequences of developing antibodies against ADAMTS13 can be very serious and even fatal. It is, therefore, always necessary to take a thorough history before the administration of COVID-19 vaccines, and careful clinical surveillance in the post-vaccine period must be taken into consideration in patients with autoimmune diseases or a clinical or family history leading to the suspicion of an autoimmune tendency.

References

- 1.Miesbach W, Menne J, Bommer M, et al. Incidence of acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura in Germany: a hospital level study. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2019;14(1):260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sukumar S, Lämmle B, Cataland SR. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. J Clin Med. 2021;10(3):536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yavaşoğlu I. Vaccination and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Turkish J Hematol. 2020;37(3):218-219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yocum A, Simon EL. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura after Ad26.COV2-S vaccination. Am J Emerg Med. 2021:441.e3-441.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sissa C, Al-Khaffaf A, Frattini F, et al. Relapse of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura after COVID-19 vaccine. Transfus Apher Sci. 2021:103145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oliveira DS, Lima TG, Benevides FLN, et al. Plasmic score applicability for the diagnosis of thrombotic microangiopathy associated with ADAMTS13-acquired deficiency in a developing country. Hematol Transfus Cell Ther. 2019;41(2):119-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020; 383(27):2603-2615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guimarães LE, Baker B, Perricone C, Shoenfeld Y. Vaccines, adjuvants and autoimmunity. Pharmacol Res. 2015;100:190-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watad A, De Marco G, Mahajna H, et al. Immune-mediated disease flares or new-onset disease in 27 subjects following mRNA/DNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Vaccines. 2021;9(5):435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ïremli BG, Şendur SN, Ünlütürk U. Three cases of subacute thyroiditis following SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: post-vaccination ASIA syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(9):2600-2605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Condorelli A, Markovic U, Sciortino R, Di Giorgio MA, Nicolosi D, Giuffrida G. Immune thrombocytopenic purpura cases following COVID-19 vaccination. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2021; 13(1):e2021047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Helms JM, Ansteatt KT, Roberts JC, et al. Severe, refractory immune thrombocytopenia occurring after SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. J Blood Med. 2021;12:221-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Candelli M, Rossi E, Valletta F, De Stefano V, Francheschi F. Immune thrombocytopenic purpura after SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Br J Haematol. 2021;194(3):547-549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cines DB, Bussel JB. SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(23):2254-2256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]