Abstract

Objectives

To examine the numbers and patterns of patients presenting to an urban acute general hospital with acute mental health presentations and to further investigate any variation related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Design

Retrospective observational cohort study.

Setting

An urban acute general hospital in London, UK, comprising of five sites and two emergency departments. The hospital provides tertiary level general acute care but is not an acute mental health services provider. There is an inpatient liaison psychiatry service.

Participants

358 131 patients attended the emergency departments of our acute general hospital during the study period. Of these, 14 871 patients attended with an acute mental health presentation. A further 14 947 patients attending with a physical illness were also noted to have a concurrent recorded mental health diagnosis.

Results

Large numbers of patients present to our acute general hospital with mental health illness even though the organisation does not provide mental health services other than inpatient liaison psychiatry. There was some variation in the numbers and patterns of presentations related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Patient numbers reduced to a mean of 9.13 (SD 3.38) patients presenting per day during the first ‘lockdown’ compared with 10.75 (SD 1.96) patients per day in an earlier matched time period (t=3.80, p<0.01). Acute mental health presentations following the third lockdown increased to a mean of 13.84 a day.

Conclusions

Large numbers of patients present to our acute general hospital with mental health illness. This suggests a need for appropriate resource, staffing and training to address the needs of these patients in a non-mental health provider organisation and subsequent appropriate transfer for timely treatment. The COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting lockdowns have resulted in variation in the numbers and patterns of patients presenting with acute mental health illness but these presentations are not new. Considerable work is still needed to provide integrated care which addresses the physical and mental healthcare needs of patients presenting to acute and general hospitals.

Keywords: mental health, COVID-19, health policy, accident & emergency medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is a retrospective study.

The study examines a large number of patient care episodes.

Diagnostic coding is open to error in recording and interpretation.

There is implicit risk in using routinely collected data to evaluate a research question where the data may have not been collected for this specific purpose.

Introduction

There is a significant overlap in the mental and physical health needs for patients and for some time it has been an aspiration to offer integrated care. The National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death (NCEPOD) investigated and reported on the mental health needs of patients treated in acute general hospitals for physical illnesses in 2017 and made several recommendations.1 Key among these were that all hospital staff who have interaction with patients, including clinical, clerical and security staff, should receive training in mental health conditions in general hospitals. Training should be developed and offered across the entire career pathway from undergraduate to workplace-based continued professional development. The report also recommended that in order to overcome the divide between mental and physical healthcare, liaison psychiatry services should be fully integrated into general hospitals. The structure and staffing of the liaison psychiatry service should be based on the clinical demand both within working hours and out-of-hours so that they can participate as part of the multidisciplinary team. These recommendations have only been adopted in part in many places and still represent a challenge several years later.

The delivery of truly integrated assessment and care for patients presenting to acute general hospitals where mental health services are not normally provided requires careful planning and an understanding of the numbers and types of patients presenting. This is so that an assessment can be made as to what is required to meet their needs and to provide high-quality care and patient experience.

We undertook this study to examine the numbers and patterns of patients presenting to an urban acute general hospital with acute mental health presentations via the emergency department. This hospital does not provide any routine mental health services other than an inpatient liaison psychiatry service. We hypothesised that our study would confirm a large number of patients presenting with acute episodes of mental health conditions despite the fact that the hospital does not provide mental health services. We further hypothesised that our study would demonstrate increasing numbers of patients presenting in this way over time and that this might be representative of the situation more generally and beyond our organisation.

The period of our study included the first waves of the global COVID-19 pandemic and so we also examined whether there was any effect on the patterns and numbers of patient presentations as a result of the pandemic and the social restrictions associated with the mandated periods of social lockdown where normal mixing and social interaction were severely restricted. We hypothesised that the periods of the social lockdown would result in increasing numbers of patients presenting via the emergency department with acute mental health needs.

Methods

Data and setting

We conducted a retrospective observational cohort study of all patients presenting to an urban acute general hospital with an acute mental health illness presentation. Our hospital organisation is made up of five hospital sites served by two acute emergency departments. Presentations to both emergency departments were included. All hospital attendances, admissions and treatments are recorded and coded to form data for Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) and are also recorded in the electronic patient record (EPR).

We used the UK government website to confirm the dates of mandated social lockdown (L) periods.2 We included the three periods of national lockdown in the UK, which occurred during the study period.

Lockdown 1 (L1) was defined between 23 March 2020 and 15 June 2020. Lockdown 2 (L2) was defined between 5 November 2020 and 2 December 2020. Lockdown 3 (L3) was defined between 6 January 2021 and 12 April 2021. For analysis and comparison, we defined the periods between the statutory periods of lockdown to be ‘inter-lockdown’ (IL) periods. Inter-lockdown 1 (IL1) was therefore defined between 16 June 2020 and 4 November 2020. Inter-lockdown 2 (IL2) was defined between 3 December 2020 and 5 January 2021. Inter-lockdown 3 (IL3) was defined between 13 April 2021 and 30 June 2021, when the study period ended after the final national lockdown.

Numbers and patterns of presentation were examined longitudinally to identify trends. We also examined and compared data for lockdown (L) and inter-lockdown (IL) periods with matched time periods (MTPs) between March 2018 and June 2019 in order to examine for any effects related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Patients

We included all adult patients aged 18 years and older. We examined the hospital coding records and EPRs for all adult patients attending our emergency departments with an acute mental health presentation between 1 January 2018 and 30 June 2021. HES data and patient records were examined to collate demographic information, diagnosis, details of initial referral and treatment, waiting times and admission.

Statistical analysis

We analysed data using SPSS Statistics V.26.0. We present data as means with SD or median values with IQRs. We used the standard t-test, χ2 tests and analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc Tukey’s test to compare categorical and continuous data between MTPs.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in framing or designing this research question. As it is a retrospective cohort study, there was no patient impact. We did ask strategic lay forum members at our hospital to read and comment on our manuscript.

Results

Numbers of patients

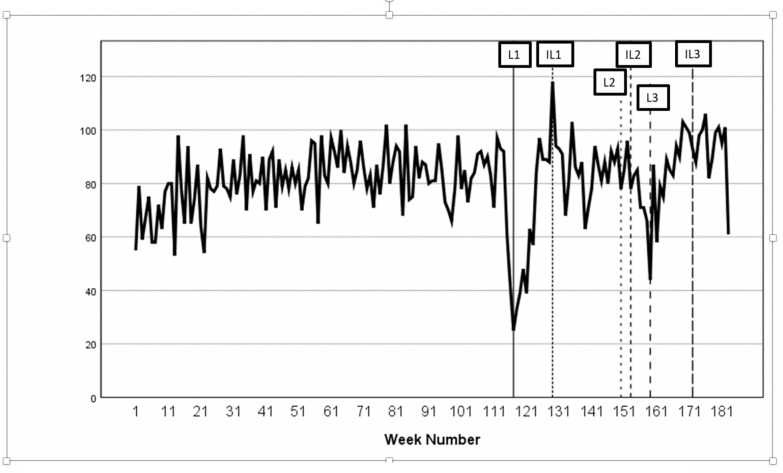

A total of 358 131 patients attended our emergency departments between 1 January 2018 and 30 June 2021. Of these, 14 871 patients (4.2%) presented to our emergency departments with an acute mental health diagnosis (figure 1). In addition, 14 947 patients (4.2%) who presented with a physical complaint also had a concurrent recorded mental health diagnosis.

Figure 1.

Mean number of presentations with acute mental health illness per week on 1 January 2018–30 June 2021. IL, inter-lockdown; L, lockdown.

Presentations

The numbers of patients presenting during the COVID-19 pandemic varied considerably. The numbers of patients presenting with acute mental health illness was at the lowest level during the first lockdown (L1) period (figure 2). When compared with an MTP in 2018, 761 patients presented acutely in L1 compared with 897 patients in MTP1 (figures 2 and 3). This represents a mean of 9.13 (SD 3.38) patients presenting per day during L1 compared with 10.75 (SD 1.96) patients per day during MTP1 (t=3.80, p<0.01).

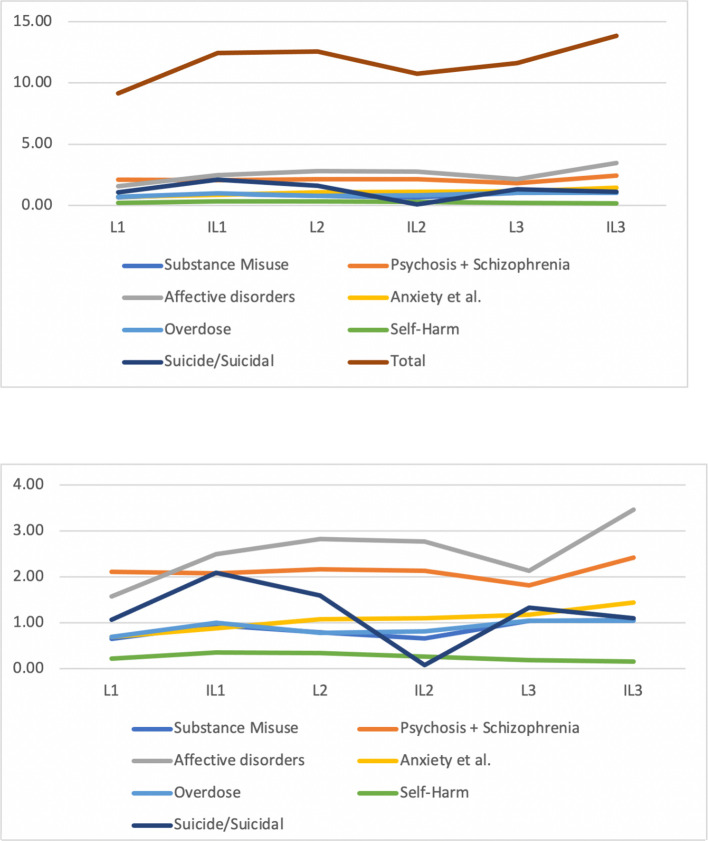

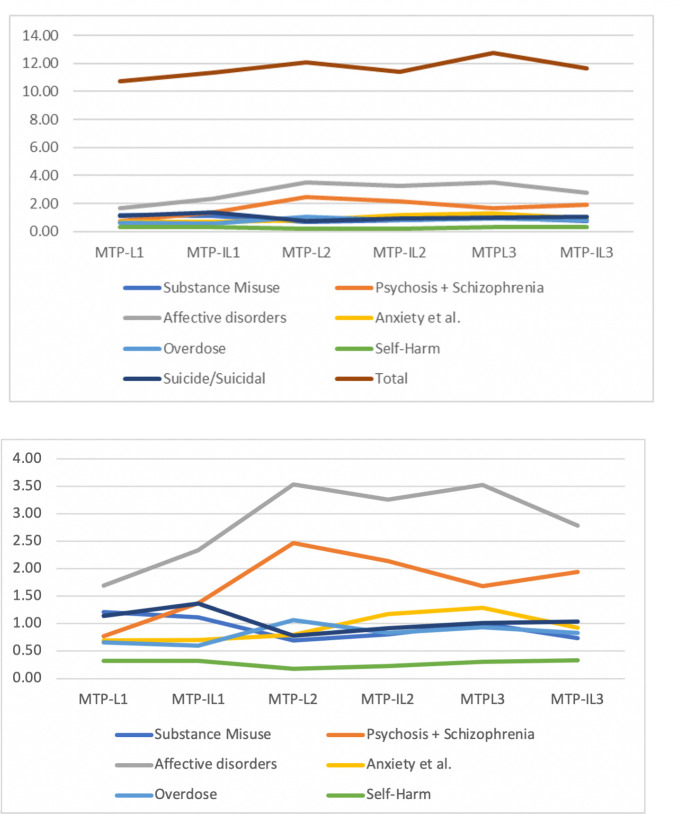

Figure 2.

Patterns of diagnosis and presentation. Mean presentations per day during the COVID-19 pandemic. IL, inter-lockdown; L, lockdown.

Figure 3.

Diagnosis patterns for acute mental health presentations on 1 January 2018–30 June 2021. IL, inter-lockdown; L, lockdown; MTP, matched time period.

Following the first lockdown, there was a significant increase in acute mental health presentations during IL1 compared with a MTP in 2018 (t=−5.34, p<0.01). There was a similar increase in acute mental health presentations following the third lockdown in IL3, with a mean 13.84 acute mental health presentations per day, which was significantly greater than the number of attendances for the MTP in 2019 (t=−10.79, p<0.01).

Age

The mean age of patients presenting to the department was 38.57 years (n=14 871, SD=15.041). There was no significant difference in the age of presentation when different time periods were compared (ANOVA, f=2.0357, p=0.0574).

Diagnoses and patterns of illness

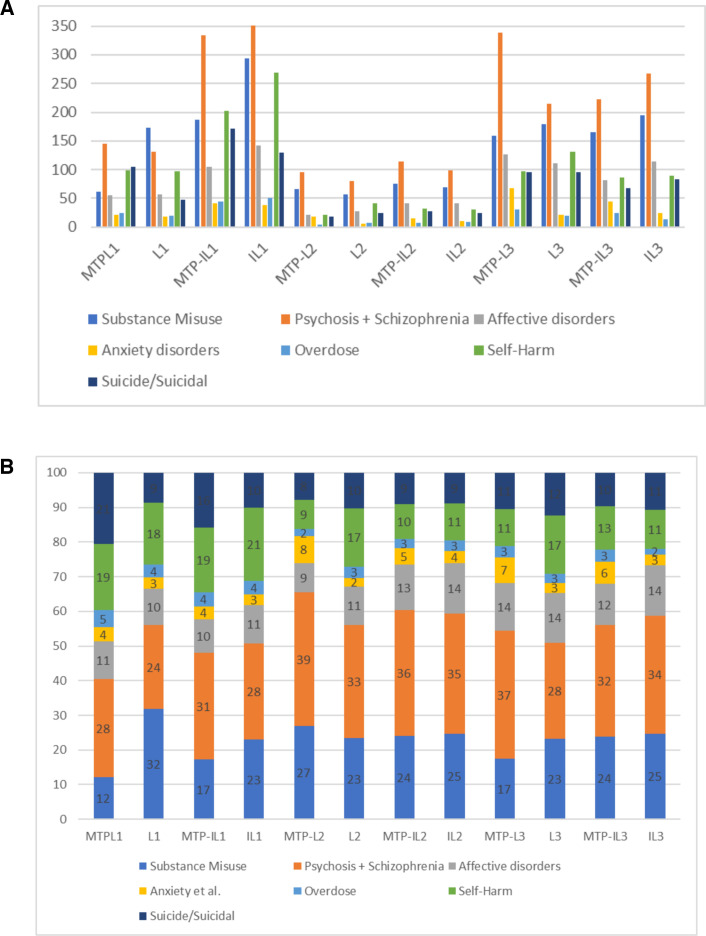

There was variation in the pattern of mental health illness presenting to our emergency departments (figure 4A, B). We noted a significant increase (t=−13.62, p<0.01) in patients presenting with psychosis in L1. There was a mean of 2.11 (SD 0.85) presentations of psychosis per day during L1 compared with a mean of 0.77 (SD 0.30) of such presentations during the respective MTP. In contrast, we saw a significant decrease in presenting rates of self-harm (t=−2.45, p=0.02) and substance misuse (t=6.28, p<0.01) per day in L1 when compared with the MTP.

Figure 4.

(A) Diagnosis for acute mental health presentations on 1 January 2018–30 June 2021. Raw number of admissions over each time period. (B) Diagnosis for acute mental health presentations on 1 January 2018–30 June 2021. Numbers expressed as a percentage of overall admissions for each time period. IL, inter-lockdown; L, lockdown; MTP, matched time period.

IL1 saw an increase in patients presenting with acute psychosis (t=−8.56, p<0.01), anxiety (t=−4.41, p<0.01), overdose (t=−11.7, p<0.01) and suicidal presentations (t=−7.34, p<0.01), compared with the respective MTP, while substance misuse presentations decreased (t=2.56, p=0.01). In L2, we recorded a continuing increase in patients attending with anxiety (t=−3.50, p<0.01), self-harm (t=−2.25, p=0.03) and suicidal presentations (t=−6.82, p<0.01), while presentations of overdoses (t=2.58, p=0.02) and affective disorders decreased (t=5.60, p<0.01). IL2 showed decreased rates of substance misuse, affective disorders and suicidal presentations.

Overall, the broad patterns and relative distributions of key diagnosis groups did not change when study periods (lockdown and inter-lockdown periods) were compared with MTPs (figures 2 and 3) except for during L1 when psychosis became the most common acute mental health diagnosis.

Emergency department assessment and outcome

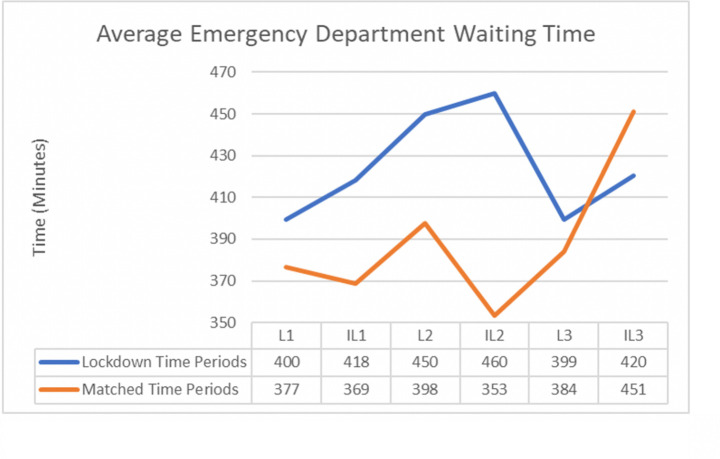

Patients attending with an acute mental health presentation spent a considerable amount of time in the emergency department before transfer was arranged to an appropriate inpatient mental health facility or they were assessed and discharged by the community mental health assessment team. Overall, the mean time spent in the department for these patients was 6 hours 52 min (n=14 871, SD=376.80) with no significant variation when lockdown and inter-lockdown periods were compared (figure 5).

Figure 5.

Waiting time in the emergency department for patients attending with acute mental health presentations on 1 January 2018–30 June 2021. IL, inter-lockdown; L, lockdown.

There were no significant differences in the proportions of patients being discharged directly or transferred to an inpatient mental healthcare facility from the emergency department during the lockdown and inter-lockdown periods.

Discussion

There was considerable concern during the COVID-19 pandemic that social isolation resulting from statutory lockdown periods would result in a considerable burden of mental health illness and morbidity.3 4 There are several reports that patients have been making increased self-reports of symptoms of anxiety, depression and other acute mental health disorders since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.5 6 The associated economic recession may also be an important factor.

There is longstanding evidence that patients with acute mental health illness present to the emergency departments of acute general hospitals1; illness is not always specifically identified as physical or mental, and the emergency department is identified as a place of safety where assessment and treatment can be started. Our study showed that considerable numbers of patients attend our emergency departments each week with acute mental health presentations. The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in some variations in the patterns of mental health illness that were seen; mental health presentations during the first lockdown period fell as did all non-COVID-19-related presentations in our emergency departments. The reasons for this are multifactorial and likely include reduced social movement during lockdown, as well as patient concern and fears about attending a hospital during a pandemic. These factors may mean that while the numbers presenting to the emergency department are reduced during the lockdown, this may under-represent the true level of mental health morbidity in the community that is simply not presenting to hospital during the pandemic. This is possibly one explanation for the rebound increase in acute mental health presentations seen following a lockdown in the inter-lockdown period.

Our study showed that 4% of patients attending our emergency departments had an acute mental health problem and 4% of patients, although attending for a physical health complaint, were known to have a concurrent mental health diagnosis. This supports the findings of the 2017 NCEPOD report and specifically the recommendations that there is a need for training and resource to equip staff in acute general hospitals to address the needs of patients presenting with mental health illness. In the years since the publication of the NCEPOD report, Treat as One. Bridging the gap between mental and physical healthcare in general hospitals, our findings suggest that there is still considerable work to do in order to achieve the standards and recommendations that it made.1

The fact that patients presenting with acute mental illness still suffer extended waiting times in the emergency department is indicative of this failing. Again, this is likely to be multifactorial and may represent delays in initial assessment or in the ability to exclude and treat physical illness appropriately. Patients attending the emergency department may need to have physical disease and illness excluded or treated before or concurrently with their mental health needs and this can take time. Extended waiting times may also reflect a lack of capacity to transfer patients to an appropriate mental healthcare facility for timely treatment. Mean waiting times in the emergency department of 6–7 hours do not suggest that mental and physical care are well integrated and may indicate that there are opportunities to improve the quality of care and the experience for these patients.

Our study has several limitations which include the retrospective nature of the study. Diagnoses were identified and confirmed from the electronic patient record and coding for patient episodes of care which are open to a degree of error in recording and interpretation. This potential for error was partly mitigated because acute mental health diagnoses were confirmed by a psychiatrist in the acute setting.

Conclusion

Patients present to acute general hospitals with both physical and mental health complaints. Our study shows that while the COVID-19 pandemic and the use of lockdowns may have had some impact on the patterns and specific mental health diagnoses that were seen in our emergency departments, the mental health workload and need in acute general hospitals is longstanding. This has not been substantially changed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our study does show that several years later, considerable work is still needed to provide integrated care which addresses the physical and mental healthcare needs of patients presenting to acute general hospitals. The recommendations of the National Confidential Enquiry into Postoperative Outcome and Death ‘Treat as One’ remain as valid and important today as they were in 2017.1

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @VFCFracClin

Contributors: All authors contributed to the study design. RA and JS conceived the study design. JC, RB and JB collected and analysed the data. JB undertook the statistical analysis. JC, RB, JB and JS contributed to the drafting and critical review of the manuscript. RA revised and edited the manuscript. All authors approved the final draft. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. RA is the guarantor of this study. JC, RB and JB contributed equally to this study and are recognised as joint first authors.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Anonymised data may be obtained on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.The National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death . ‘Treat as One. Bridging the gap between mental and physical healthcare in general hospitals’ [Internet], 2017. Available: https://www.ncepod.org.uk/2017report1/downloads/TreatAsOne_FullReport.pdf [Accessed 12 Oct 2021].

- 2.The Institute for Government . Timeline of UK government coronavirus lockdowns [Internet], 2021. Available: https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/charts/uk-government-coronavirus-lockdowns [Accessed 13 Oct 2021].

- 3.Luykx JJ, Vinkers CH, Tijdink JK. Psychiatry in times of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. JAMA Psychiatry 2020;77:1097. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheridan Rains L, Johnson S, Barnett P, et al. Early impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health care and on people with mental health conditions: framework synthesis of international experiences and responses. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2021;56:13–24. 10.1007/s00127-020-01924-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pierce M, Hope H, Ford T, et al. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. Lancet Psychiatry 2020;7:883–92. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jia R, Ayling K, Chalder T, et al. Mental health in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic: cross-sectional analyses from a community cohort study. BMJ Open 2020;10:e040620. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Anonymised data may be obtained on reasonable request to the corresponding author.