Abstract

BACKGROUND

Official recommendations differ regarding tympanostomy-tube placement for children with recurrent acute otitis media.

METHODS

We randomly assigned children 6 to 35 months of age who had had at least three episodes of acute otitis media within 6 months, or at least four episodes within 12 months with at least one episode within the preceding 6 months, to either undergo tympanostomy-tube placement or receive medical management involving episodic antimicrobial treatment. The primary outcome was the mean number of episodes of acute otitis media per child-year (rate) during a 2-year period.

RESULTS

In our main, intention-to-treat analysis, the rate (±SE) of episodes of acute otitis media per child-year during a 2-year period was 1.48±0.08 in the tympanostomy-tube group and 1.56±0.08 in the medical-management group (P = 0.66). Because 10% of the children in the tympanostomy-tube group did not undergo tympanostomy-tube placement and 16% of the children in the medical-management group underwent tympanostomy-tube placement at parental request, we conducted a per-protocol analysis, which gave corresponding episode rates of 1.47±0.08 and 1.72±0.11, respectively. Among secondary outcomes in the main analysis, results were mixed. Favoring tympanostomy-tube placement were the time to a first episode of acute otitis media, various episode-related clinical findings, and the percentage of children meeting specified criteria for treatment failure. Favoring medical management was children’s cumulative number of days with otorrhea. Outcomes that did not show substantial differences included the frequency distribution of episodes of acute otitis media, the percentage of episodes considered to be severe, and antimicrobial resistance among respiratory isolates. Trial-related adverse events were limited to those included among the secondary outcomes of the trial.

CONCLUSIONS

Among children 6 to 35 months of age with recurrent acute otitis media, the rate of episodes of acute otitis media during a 2-year period was not significantly lower with tympanostomy-tube placement than with medical management. (Funded by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders and others; ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT02567825.)

NEXT TO THE COMMON COLD, ACUTE otitis media is the most frequently diagnosed illness in children in the United States. Caused predominantly by Streptococcus pneumoniae and nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae, acute otitis media is also the leading indication for antimicrobial treatment in children.1 Recurrent acute otitis media — conventionally defined as at least three episodes in 6 months, or at least four episodes in 12 months with at least one episode within the preceding 6 months2 — is the principal indication for tympanostomy-tube placement, the most frequently performed operation in children after the newborn period.3 In 2006, the most recent year with available data, 667,000 U.S. children younger than 15 (and mainly younger than 3) years of age underwent tympanostomy-tube placement.

Supporting the performance of tympanostomy-tube placement for recurrent acute otitis media has been the commonplace observation, after surgery, of acute otitis media–free periods of varying duration. Counterbalancing this view have been the cost of tympanostomy-tube placement; risks and possible late sequelae of anesthesia in young children4; the possible occurrence of refractory tube otorrhea,5 tube blockage, premature extrusion, or dislocation of the tube into the middle-ear cavity; various structural tympanic-membrane sequelae6,7; and the possible development of mild conductive hearing loss.7 Finally, tempering support for surgery is the progressive reduction in the incidence of acute otitis media that usually accompanies a child’s increasing age.

Previous trials of tympanostomy-tube placement for recurrent acute otitis media, most conducted before the introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, have given mixed results and were limited, variously, by small sample size, uncertain validity of diagnoses of acute otitis media determining trial eligibility, short periods of follow-up, and substantial attrition of participants.8–11 Official recommendations regarding tympanostomy-tube placement for children with recurrent acute otitis media differ — an otolaryngologic guideline recommends the procedure for children with recurrent acute otitis media, provided that middle-ear effusion is present in at least one ear12; a contemporaneous pediatric guideline discusses tympanostomy-tube placement as an “option [that] clinicians may offer.”2 Given these uncertainties, we undertook the present trial involving children 6 to 35 months of age who had a history of recurrent acute otitis media2 to determine whether tympanostomy-tube placement, as compared with medical management (comprising episodic antimicrobial treatment, with the option of tympanostomy-tube placement in the event of treatment failure, as defined below), would result in a greater reduction in the children’s rate of recurrence of acute otitis media during the ensuing 2-year period.

METHODS

TRIAL SETTING AND ORGANIZATION

We conducted this trial between December 2015 and March 2020 at UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh and affiliated practices; Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, D.C.; and Kentucky Pediatric and Adult Research in Bardstown, Kentucky. The protocol, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org, was approved by the institutional review board at each site; written informed consent was obtained from a parent of each enrolled child.

The authors vouch for the completeness and accuracy of the data. The trial entailed no agreements with outside entities. All the authors attest that the trial was performed in accordance with the final versions of the protocol and the statistical analysis plan (available with the protocol).

PARTICIPANTS

Children 6 to 35 months of age were eligible to participate if they met specified criteria for having had recurrent acute otitis media, as described above,2 and provided that at least one of the qualifying episodes of acute otitis media had been confirmed by a trial clinician. After the children’s enrollment, to authenticate episodes of acute otitis media evaluated by trial clinicians, we required a history of acute symptoms that parents rated with a score of 2 or higher on the five-item Acute Otitis Media Severity of Symptom (AOM-SOS) scale, version 4.0 (with scores ranging from 0 to 10 and higher scores indicating greater severity of symptoms),13 and the presence of either middle-ear effusion with specified combinations of otalgia, tympanic-membrane bulging, and tympanic-membrane erythema or purulent otorrhea. For episodes managed by nontrial clinicians, we required documentation of at least one AOM-SOS scale symptom and findings of either tympanic-membrane bulging or purulent otorrhea. We excluded children who had undergone tympanostomy-tube placement, adenoidectomy, or tonsillectomy or who had a chronic illness, a congenital anomaly that increased the risk of otitis media (e.g., cleft palate), otitis media with effusion in both ears of at least 3 months’ duration, or sensorineural hearing loss.

RANDOMIZATION

We stratified children according to age (6 to 11 months, 12 to 23 months, or 24 to 35 months) and according to their exposure or nonexposure to at least three children for at least 10 hours per week. At each trial site, within each stratum, we randomly assigned children in blocks of four to either undergo tympanostomy-tube placement or receive nonsurgical medical management, with the option of tympanostomy-tube placement in the event of treatment failure. Assignments were conducted at a University of Pittsburgh data center and were revealed after enrollment, owing to the impossibility of blinding. Tympanostomy-tube placement was usually performed within 2 weeks; Teflon Armstrong-type tympanostomy tubes were inserted in both ears.7

FOLLOW-UP

After randomization, we scheduled children’s assessments at 8-week intervals. We asked parents to bring children for evaluation if the children had any respiratory symptoms for at least 5 days and to bring children within 48 hours if they had any symptom suggestive of acute otitis media or had received a diagnosis of acute otitis media at a nontrial site.

EXAMINATION AND ASSESSMENT

Assessments were conducted by trial clinicians who had successfully completed an otoscopic validation program.14 We categorized episodes of acute otitis media as probably severe or probably nonsevere on the basis of parents’ reports, as described below.2,15 When episodes occurred, we obtained a nasopharyngeal specimen (or in children older than 24 months of age, a throat swab) for culture. We provided parents a text link to an electronic diary to record on a daily basis their child’s symptoms as specified in the AOM-SOS scale and also any instance of protocol-defined diarrhea (≥3 watery stools on 1 day or ≥2 watery stools on 2 consecutive days) or of diaper dermatitis resulting in topical antifungal treatment. We counted a span of illness as constituting two discrete episodes of acute otitis media if symptoms and signs persisted for or recurred at least 17 days after the start of antimicrobial treatment.16

At each visit, we recorded all use of other health care resources. Periodically at nonillness visits, we obtained nasopharyngeal or throat specimens for culture. We also completed the Otitis Media–6 Survey,17 which assesses children’s quality of life, and the Caregiver Impact Questionnaire, which assesses the effect of children’s illness on parents18 (see the Supplementary Appendix, available at NEJM.org). At the end-of-trial visit, we asked parents to score their level of satisfaction with their child’s treatment assignment.

TREATMENT

In children with tympanostomy tubes in place, the occurrence of otorrhea accompanied by at least one AOM-SOS scale symptom (except immediately postoperatively) was considered to be indicative of acute infection. In those children, we obtained a specimen for culture from the tube lumen when possible and treated the children with 5 drops of 0.3% ofloxacin (Floxin) ototopically twice daily for 10 days. When otorrhea persisted beyond 7 days, we prescribed amoxicillin–clavulanate, as described below for children in the medical-management group, followed on occasion by alternative, culture-directed antimicrobial treatment. Tubes that were extruded within 6 months were replaced if the child subsequently had at least two episodes of acute otitis media within 3 months; beyond 6 months, tubes were reinserted if, after extrusion, episodes recurred at a rate sufficient to be characterized as recurrent acute otitis media.

Children in the medical-management group who had episodes of acute otitis media were treated with oral amoxicillin—clavulanate at a dose of 90 mg of amoxicillin and 6.4 mg of clavulanate per kilogram of body weight per day for 10 days. When response appeared to be inadequate, children received ceftriaxone at a dose of 75 mg per kilogram intramuscularly, repeated in 48 hours.

OUTCOME MEASURES

All outcome measures were prespecified. The primary measure was the mean number of episodes of acute otitis media per child-year (rate) during the 2-year follow-up period. Secondary measures were the percentage of children who had treatment failure, as defined below; the time to a first episode of acute otitis media; the frequency distribution of episodes; the percentage of episodes categorized as probably severe2,15; cumulative days per year with tube otorrhea, other symptoms of acute otitis media, or receipt of systemic antimicrobial treatment; the occurrence of protocol-defined diarrhea or of diaper dermatitis; antimicrobial resistance in nasopharyngeal and throat isolates obtained during follow-up; assessments of acute otitis media–related child and parent quality of life; parental satisfaction with the treatment assignment; and the use of other medical and nonmedical resources.

TREATMENT FAILURE

We defined treatment failure as the development of any of the following: in children in the medical-management group, recurrences of acute otitis media at the frequency originally required for trial entry, thereby resulting in referral for tympanostomy-tube placement, or receipt of tympanostomy-tube placement at parental request; and in all children, long cumulative periods of systemic antimicrobial treatment, persistent otorrhea, otitis media with effusion, tympanic-membrane perforation, or antimicrobial-associated protocol-defined diarrhea; acute otitis media–related hospitalization; or an untoward reaction to anesthesia. (Details are provided in the final version of the protocol.)

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

We estimated that enrolling 240 children would permit detection of a 33% lower rate of episodes of acute otitis media in the tympanostomy-tube group than in the medical-management group with a two-sided significance level of 0.05 and a power of at least 90%, assuming a mean rate of 1.5 episodes per year in the medical-management group and 25% attrition. The main analysis was based on the intention-to-treat principle. As described below, we also conducted a per-protocol analysis; in this analysis, from the start we excluded children assigned to undergo tympanostomy-tube placement who never underwent surgery, and subsequently for children in the medical-management group who for any reason underwent tympanostomy-tube placement, we censored data from that point forward. All analyses used two-sided tests and, where appropriate, included adjustment for trial site and stratification variables.

We used the chi-square test for comparisons regarding baseline characteristics of the children; generalized linear models to compare rates of occurrence of acute otitis media, to test for interactions between main effects, and to conduct analyses of treatment failure, side effects, and bacterial colonization; and one minus Kaplan–Meier survival estimates to plot the percentages of children who had an initial recurrence of acute otitis media over time. We used the Cox proportional-hazards model to compare hazard functions; generalized estimating equations to compare characteristics of episodes of acute otitis media, the use of medical and nonmedical resources, and antimicrobial resistance; and mixed models for analysis of days with specific outcomes over time, with weighting according to the length of follow-up, and for comparisons regarding responses on the Otitis Media–6 Survey and Caregiver Impact Questionnaire. To address missing data, we used multiple imputation for the primary outcome and performed sensitivity analyses for secondary outcomes. We conducted one interim analysis for efficacy after 120 children had completed follow-up; we conducted testing at two-sided significance levels of 0.005 and 0.048 at the interim and final analyses, respectively.

RESULTS

TRIAL POPULATION

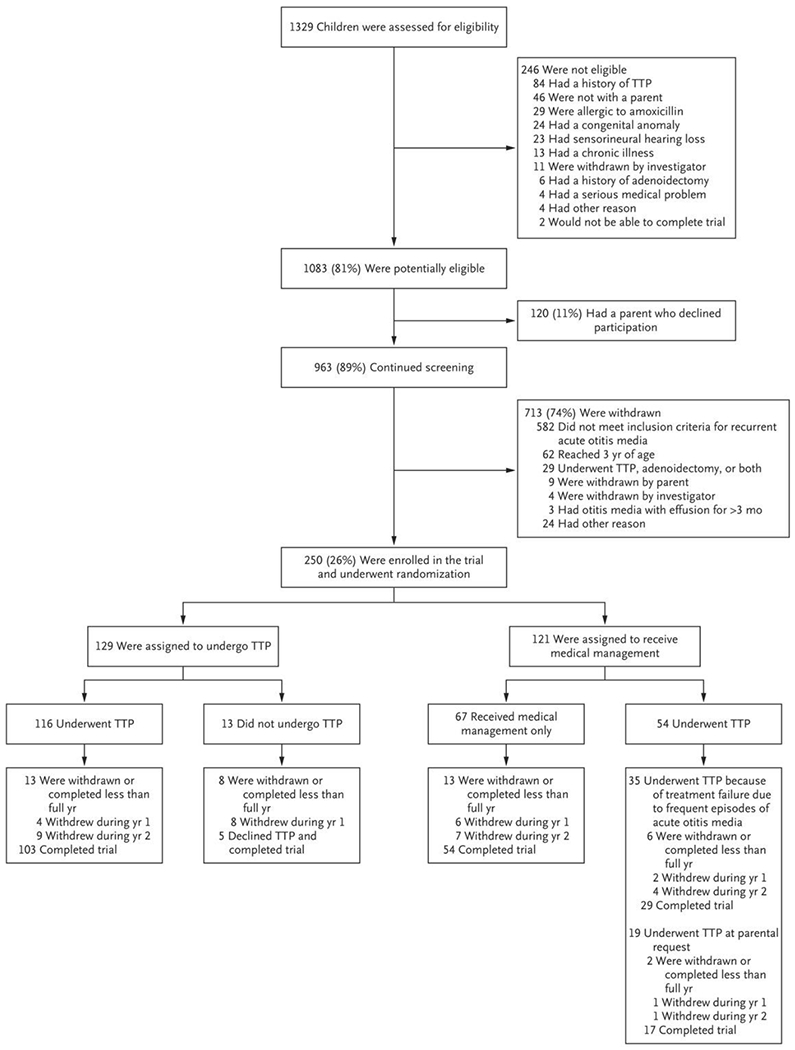

We screened 1329 children and enrolled 250. All the children had received pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Of the 250 children, 229 (92%) completed 1 year of follow-up and 208 (83%) completed 2 years of follow-up; the median duration was 1.96 years in each treatment group. Of 129 children assigned to the tympanostomy-tube group, 13 (10%) did not undergo tympanostomy-tube placement; of 121 assigned to the medical-management group, 54 eventually underwent tympanostomy-tube placement — 35 (29%) according to the trial protocol because of frequent recurrences of acute otitis media and 19 (16%) at parental request (Fig. 1). Selected sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the enrolled children are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1. Enrollment, Randomization, and Follow-up of Children in the Trial.

TTP denotes tympanostomy-tube placement.

Table 1.

Selected Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Children, According to Treatment Assignment.*

| Characteristic | Tympanostomy-Tube Group (N = 129) | Medical-Management Group (N = 121) | All Children (N = 250) |

|---|---|---|---|

| number of children (percent) | |||

| Site of enrollment† | |||

|

| |||

| Pittsburgh | 92 (71) | 91 (75) | 183 (73) |

|

| |||

| Washington, DC | 20 (16) | 16 (13) | 36 (14) |

|

| |||

| Bardstown, KY | 17 (13) | 14 (12) | 31 (12) |

|

| |||

| Age at enrollment | |||

|

| |||

| 6–11 mo | 46 (36) | 45 (37) | 91 (36) |

|

| |||

| 12–23 mo | 70 (54) | 67 (55) | 137 (55) |

|

| |||

| 24–35 mo | 13 (10) | 9 (7) | 22 (9) |

|

| |||

| Sex | |||

|

| |||

| Female | 42 (33) | 48 (40) | 90 (36) |

|

| |||

| Male | 87 (67) | 73 (60) | 160 (64) |

|

| |||

| Race‡ | |||

|

| |||

| White | 70 (54) | 70 (58) | 140 (56) |

|

| |||

| Black | 41 (32) | 42 (35) | 83 (33) |

|

| |||

| Asian | 3 (2) | 2 (2) | 5 (2) |

|

| |||

| Multiracial | 10 (8) | 7 (6) | 17 (7) |

|

| |||

| Other | 5 (4) | 0 | 5 (2) |

|

| |||

| Ethnic group‡ | |||

|

| |||

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 110 (85) | 111 (92) | 221 (88) |

|

| |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 19 (15) | 10 (8) | 29 (12) |

|

| |||

| Exposure to other children§ | |||

|

| |||

| No | 26 (20) | 22 (18) | 48 (19) |

|

| |||

| Yes | 103 (80) | 99 (82) | 202 (81) |

|

| |||

| Otitis media with effusion present at randomization¶ | |||

|

| |||

| No | 85 (66) | 71 (59) | 156 (62) |

|

| |||

| Yes | 44 (34) | 50 (41) | 94 (38) |

|

| |||

| Estimated risk of recurrences of acute otitis media‖ | |||

|

| |||

| Probably lesser | 63 (49) | 72 (60) | 135 (54) |

|

| |||

| Probably greater | 66 (51) | 49 (40) | 115 (46) |

Percentages may not total 100 because of rounding.

The institutions were UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, Children’s National Medical Center, and Kentucky Pediatric and Adult Research.

Race and ethnic group were reported by the parent.

Exposure to other children was defined as exposure to at least three children for at least 10 hours per week.

This condition was distinguished from acute otitis media.

Risk of recurrences of acute otitis media was categorized, with the use of a 16-point scale, as probably lesser (<8 points) or probably greater (≥8 points) on the basis of the following known or presumed risk factors: early age of onset of acute otitis media, numerous or frequent previous episodes of acute otitis media, receipt of multiple courses of antibiotic treatment (suggesting a higher risk of acute otitis media caused by resistant pathogens), eligibility for enrollment first evident during warm-weather months, parental characterization of previous episodes of acute otitis media as severe, eligibility for enrollment despite nonexposure to other young children, moderate or marked tympanic-membrane bulging during previous episodes of acute otitis media, most previous episodes of acute otitis media in both ears, and a high score on the Acute Otitis Media—Severity of Symptom scale during screening, at enrollment, or both. (Details are provided in the final version of the protocol.)

PRIMARY AND SECONDARY OUTCOMES

Most results that are presented in this report derive from the main, intention-to-treat analysis. Because 32 children had deviations from the trial protocol and 35 children in the medical-management group underwent protocol-directed tympanostomy-tube placement, we undertook an additional, per-protocol analysis for all outcomes. We report here only key results from that analysis.

Tables 2 and 3 and Figure 2 summarize findings with respect to the primary and secondary outcomes of the trial. The rate (±SE) of occurrence of acute otitis media per child-year during the 2-year follow-up period (primary outcome measure) was 1.48±0.08 in the tympanostomy-tube group and 1.56±0.08 in the medical-management group (risk ratio, 0.97; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.84 to 1.12; P = 0.66). In the per-protocol analysis, corresponding rates were 1.47±0.08 and 1.72±0.11, respectively (risk ratio, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.69 to 0.97).

Table 2.

Two-Year Primary and Secondary Outcomes, According to Treatment Assignment.*

| Outcome Measure or Child Characteristic | Tympanostomy-Tube (N = 129) | Medical-Management (N = 121) | All Children (N = 250) | Estimated Between-Group Difference (95% CI); P Value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two-year occurrence of episodes of acute otitis media | ||||

| No. of episodes; no. of child-yr‡ | 384; 259.5 | 378; 242.6 | 762; 502.1 | |

| Yr 1 and 2 combined — rate per child-yr§ | 1.48±0.08 | 1.56±0.08 | 1.52±0.08 | 0.97 (0.84 to 1.12); P = 0.66 |

| Yr 1 | 1.94±0.12 | 2.20±0.14 | 2.07±0.13 | |

| Yr 2 | 1.06±0.09 | 0.97±0.09 | 1.01±0.09 | |

| Frequency distribution of episodes of acute otitis media, yr 1 and 2 combined¶ | ||||

| No. of episodes — no. of children/total no. (%) | ||||

| 0 | 17/108 (16) | 12/100 (12) | 29/208 (14) | |

| 1 or 2 | 41/108 (38) | 41/100 (41) | 82/208 (39) | |

| 3 or 4 | 24/108 (22) | 29/100 (29) | 53/208 (25) | |

| ≥5 | 26/108 (24) | 18/100 (18) | 44/208 (21) | |

| Range — no. of episodes | 0 to 13 | 0 to 16 | 0 to 16 | |

| Estimated severity of episodes of acute otitis media — no. of episodes/total no.(%)‖ | ||||

| Probably nonsevere | 180/336 (54) | 168/333 (50) | 348/669 (52) | |

| Probably severe | 156/336 (46) | 165/333 (50) | 321/669 (48) | 0.91 (0.76 to 1.09) |

| Treatment failure — no. of children/total no. (%)** | ||||

| Had failure | 56/124 (45) | 74/120 (62) | 130/244 (53) | 0.73 (0.58 to 0.92) |

| Did not have failure | 68/124 (55) | 46/120 (38) | 114/244 (47) | |

| Total days with otitis-related symptoms or signs — no. of days per yr (range) | ||||

| Tube otorrhea | 7.96±1.10 (0 to 81) | 2.83±0.78 (0 to 76) | 5.44±0.70 (0 to 81) | 5.21 (2.60 to 7.82) |

| Other symptoms of acute otitis media | 2.00±0.29 (0 to 17) | 8.33±0.59 (0 to 35) | 5.11±0.38 (0 to 35) | −6.32 (−7.55 to −5.10) |

| Total days of antimicrobial treatment — no. of days per yr (range) | 8.76±0.94 (0 to 119) | 12.92±0.90 (0 to 56) | 10.80±0.67 (0 to 119) | −4.50 (−6.82 to −2.18) |

| Child and parent QOL assessments | ||||

| Score on the Otitis Media—6 Survey†† | 1.50±0.03 | 1.55±0.03 | 1.52±0.02 | −0.05 (−0.13 to 0.02) |

| Score on the Otitis Media—6 Survey — children’s overall QOL‡‡ | 8.45±0.07 | 8.37±0.07 | 8.42±0.05 | 0.06 (−0.13 to 0.24) |

| Score on the Caregiver Impact Questionnaire§§ | 10.82±0.53 | 10.93±0.55 | 10.87±0.38 | −0.04 (−1.55 to 1.47) |

| Score on the Caregiver Impact Questionnaire — caregivers’ overall QOL‡‡ | 8.55±0.06 | 8.50±0.06 | 8.53±0.04 | 0.03 (−0.14 to 0.20) |

| Parental satisfaction with treatment assignment¶¶ | 4.64±0.10 | 4.43±0.13 | 4.54±0.08 | 0.25 (−0.06 to 0.56) |

| Use of medical resources other than trial visits — no. of parent reports/no. of parental questionnaires (%)‖‖ | 738/1635 (45) | 672/1628 (41) | 1410/3263 (43) | 1.07 (0.98 to 1.18) |

| Use of nonmedical resources — no. of reported occurrences/no. of parental questionnaires (%)*** | ||||

| Missed work owing to child’s illness | 286/1635 (17) | 256/1628 (16) | 542/3263 (17) | 1.11 (0.88 to 1.41) |

| Special child care arrangements owing to child’s illness | 231/1635 (14) | 195/1628 (12) | 426/3263 (13) | 1.15 (0.89 to 1.48) |

Plus—minus values are means ±SE. Three additional secondary outcome measures — the occurrence of otorrhea, protocol-defined diarrhea, and medication-related diaper dermatitis — were also considered to be adverse events. CI denotes confidence interval, and QOL quality of life.

Estimates for rates and percentages are based on risk ratios; estimates for continuous outcomes are based on least-squares means. Estimates are adjusted for trial site, age at enrollment, and exposure or nonexposure to other children, unless noted otherwise. A P value is provided only for the primary outcome. There was no adjustment for multiple comparisons across the secondary outcomes; results are reported with point estimates and 95% confidence intervals. The confidence intervals are also not adjusted for multiple comparisons and should not be used to infer definitive treatment effects.

Values for the number of episodes are rounded to the nearest whole number. The measure “child-years” comprises both full-year and fractional-year experiences, the latter a consequence of withdrawal or loss to follow-up of some children. For each child with incomplete 2-year follow-up, we imputed the total number of episodes of acute otitis media using multivariate imputation by chained equations with 50 imputations. For the tympanostomy-tube group. 231.1 of the 259.5 child-years (89%) that are listed represented actual experience; corresponding values for the medical-management group were 222.6 of 242.6 child-years (92%). Values for the remaining child-years were imputed.

This was the primary outcome measure. The values shown reflect multivariate imputation. Before imputation, the values were 1.45±0.08 in the tympanostomy-tube group and 1.50±0.08 in the medical-management group.

Data were limited to children with at least 23 months of follow-up.

The current American Academy of Pediatrics clinical practice guideline regarding the management of acute otitis media refers to children with “severe signs or symptoms” as those with “moderate or severe otalgia or otalgia for at least 48 hours or temperature 39°C (102.2°F) or higher.”2 In an effort to simulate that definition, we used scores on two items of the five-item Acute Otitis Media Severity of Symptom (AOM-SOS) scale, version 4.0,13 in which parents are asked to rate symptoms, as compared with their child’s usual state, as “none,” “a little,” or “a lot,” with corresponding scores of 0. 1, and 2. We categorized episodes of acute otitis media as “probably severe” if the parent described the child as having had moderate or severe otalgia (“a lot” of ear tugging: i.e., a score of 2), a temperature 39°C or higher, or an AOM-SOS scale score of more than 6 (range, 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating greater severity of symptoms) on day 1.2,15

Protocol criteria for determination of treatment failure are described in the final version of the protocol. This analysis concerns 244 children with follow-up of any duration; 6 children were not evaluated beyond the enrollment visit. Of the children who had treatment failure, the failure was attributed to the occurrence of frequent episodes of acute otitis media in all 56 children in the tympanostomy-tube group and in 55 of the 74 children in the medical-management group. Of these 55 children, 35 underwent tympanostomy-tube placement and 20 did not. The mean time from randomization to tympanostomy-tube placement in these 35 children was 5.17 months. In the remaining 19 children, the episode-frequency criterion for treatment failure was not met, but treatment failure was instead ascribed to the children’s receipt of tympanostomy-tube placement at parental request. The mean time from randomization to tympanostomy-tube placement in these 19 children was 2.51 months. Seven of these 19 children had had no episodes of acute otitis media after randomization; were these 7 children to be excluded from the analysis, the risk of treatment failure would still be lower in the tympanostomy-tube group than in the medical-management group.

The Otitis Media—6 Survey was scored with the use of an ordinal response scale from 1 (no problem) to 7 (greatest problem).17

Children’s and parents’ overall quality of life was scored with the use of an ordinal response scale from 0 (worst quality of life) to 10 (best quality of life).

Scoring on the Caregiver Impact Questionnaire was expanded to a continuous response scale from 0 (no effect on caregiver) to 100 (greatest effect).18

Parental satisfaction with the child’s treatment assignment was assessed on a five-point scale, with higher numbers indicating greater satisfaction.

Shown is the number of parent reports that the child had seen any health care provider since the last trial visit. Eleven children in the tympanostomy-tube group and two in the medical-management group underwent a second tube-placement procedure at intervals ranging from 191 to 553 days after the first procedure. Eight children in the tympanostomy-tube group and two children in the medical-management group underwent adenoidectomy with or without tonsillectomy, procedures not contemplated in the trial protocol.

Shown is the number of instances in which parents reported missing work or the need for special child care arrangements for at least 1 day.

Table 3.

Adverse Events, According to Treatment Assignment.

| Adverse Event | Tympanostomy-Tube Group (N = 129) | Medical-Management Group (N = 121) | All Children (N = 250) | Risk Ratio (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of children (%) | No. of Events | No. of children (%) | No. of Events | No. of children (%) | No. of Events | ||

| Nonserious events | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Protocol-defined diarrhea* | 21 (16) | 43 | 34 (28) | 59 | 55 (22) | 102 | 0.67 (0.44–1.03) |

|

| |||||||

| Diaper dermatitis† | 25 (19) | 46 | 33 (27) | 56 | 58 (23) | 102 | 0.79 (0.51–1.22) |

|

| |||||||

| Tube otorrhea‡ | 94 (73) | 320 | 34 (28) | 119 | 128 (51) | 439 | 2.57 (1.91–3.48) |

|

| |||||||

| Otorrhea, not tube-associated | 0 | 0 | 8 (7) | 8 | 8 (3) | 8 | — |

|

| |||||||

| Serious events: miscellaneous§ | 3 (2) | 3 | 7 (6) | 8 | 10 (4) | 11 | 0.40 (0.11–1.52) |

Protocol-defined diarrhea was the occurrence of at least three watery stools on 1 day or at least two watery stools on 2 consecutive days.

Diaper dermatitis was defined as dermatitis resulting in topical antifungal treatment.

Three children in the tympanostomy-tube group and two in the medical-management group received placement of an ear wick in treating refractory tube otorrhea.

In the tympanostomy-tube group, there was one serious adverse event each involving intussusception, asthma exacerbation, and gastroenteritis. In the medical-management group, there were three serious adverse events involving asthma exacerbation and one serious adverse event each involving complex febrile seizure, respiratory insufficiency, bronchiolitis, dehydration, and protocol-defined diarrhea resulting in hospitalization.

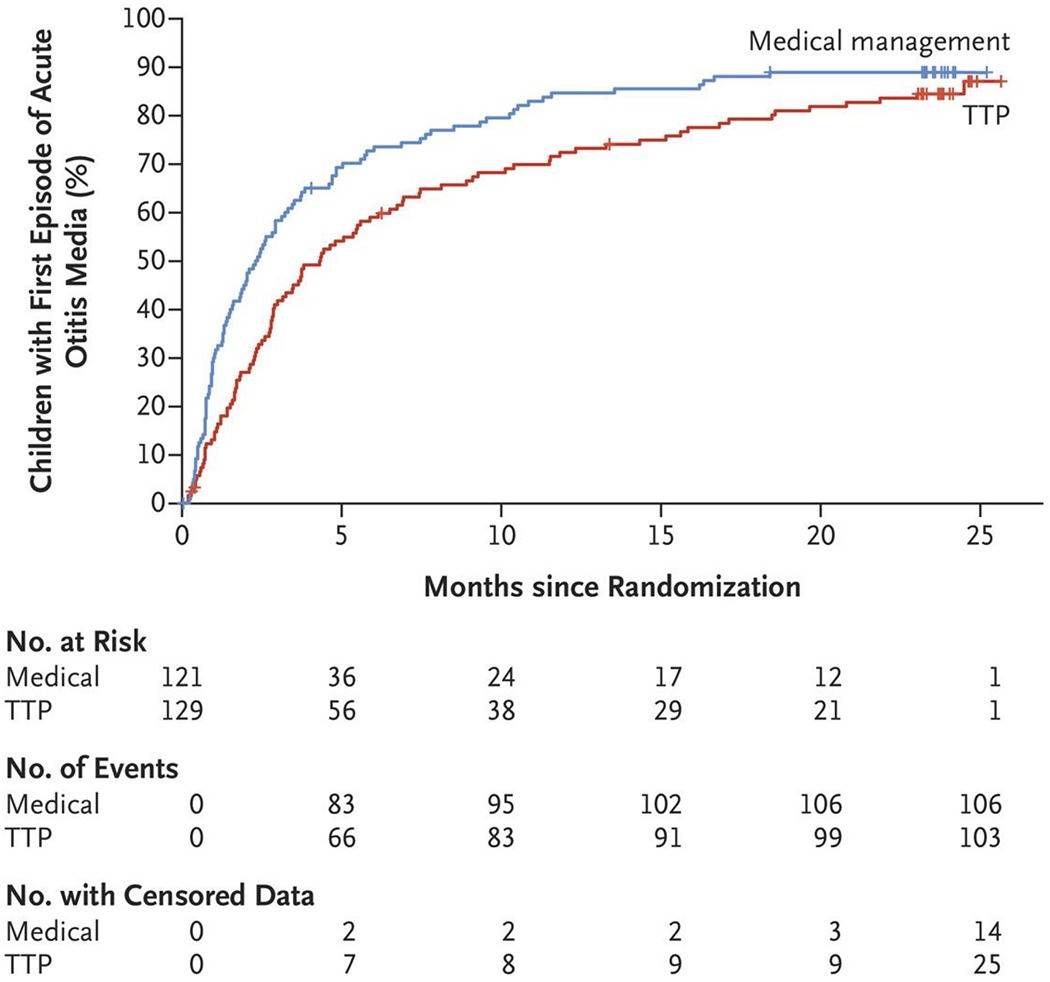

Figure 2. Time to First Recurrent Episode of Acute Otitis Media.

Shown are one minus Kaplan–Meier survival estimates of the cumulative percentage of children who had a recurrent episode of acute otitis media, according to trial group. The median time to a first occurrence of acute otitis media was longer in the tympanostomy-tube group than in the medical-management group (4.34 months vs. 2.33 months; hazard ratio, 0.68; 95% confidence interval, 0.52 to 0.90).

In each treatment group, the rate of occurrence of acute otitis media during the first follow-up year was approximately twice the rate during the second year. In the trial population overall, the rate among children 6 to 11 months of age at enrollment was 2.63 (95% CI, 1.79 to 3.88) times the rate among those 24 to 35 months of age at enrollment, and the rate among children 12 to 23 months of age at enrollment was 1.80 (95% CI, 1.22 to 2.63) times the rate among the older children (P<0.001 for the overall comparison). Rates appeared to be unrelated to the initial estimates of children’s risk of recurrences of acute otitis media (risk ratio, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.99 to 1.33), their degree of exposure to other children (risk ratio, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.82 to 1.20), or whether they had otitis media with effusion at trial entry (risk ratio, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.84 to 1.14) (data not shown).

Certain secondary outcome measures — namely, the occurrence of otorrhea, protocol-defined diarrhea, and medication-related diaper dermatitis — were also considered to be adverse events (Table 3). No substantial differences were apparent between treatment groups regarding the frequency distribution of episodes of acute otitis media, the percentage of episodes categorized as probably severe, the percentage of children who had protocol-defined diarrhea or medication-related diaper dermatitis, the extent of antimicrobial resistance among pathogens isolated from the nasopharynx or throat in the course of follow-up, measures of children’s quality of life and of the effect of children’s illness on parents, the use of medical and nonmedical resources, or parental satisfaction with the treatment assignment.

Among other secondary outcomes, the median time to a first occurrence of acute otitis media was longer in the tympanostomy-tube group than in the medical-management group (4.34 months vs. 2.33 months; hazard ratio, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.52 to 0.90) (Fig. 2). A smaller percentage of children in the tympanostomy-tube group than in the medical-management group met the criteria for treatment failure (45% vs. 62%; risk ratio, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.58 to 0.92), a difference largely attributable to receipt of tympanostomy-tube placement at parental request by the 19 children in the medical-management group in whom the episode-frequency criterion for treatment failure was not met. Children in the tympanostomy-tube group also had fewer days per year with otitis-related symptoms other than tube otorrhea than those in the medical-management group (mean, 2.00±0.29 days vs. 8.33±0.59 days), and they received systemic antimicrobial treatment for fewer days per year (mean, 8.76±0.94 days vs. 12.92±0.90 days). Children in the tympanostomy-tube group, however, had more days per year with tube otorrhea (mean, 7.96±1.10 days vs. 2.83±0.78 days). Per-protocol analyses of secondary outcomes yielded generally similar results.

In addition, we compared baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the 55 children in the medical-management group who met clinical criteria for treatment failure on the basis of continuing recurrent acute otitis media (regardless of whether they later underwent tympanostomy-tube placement) with the characteristics of the 46 children in that group with follow-up data who neither met the criteria nor underwent tympanostomy-tube placement at parental request. The subgroups differed significantly only with respect to the age at trial enrollment; the 55 children who eventually met treatment-failure criteria were generally younger.

BACTERIAL RESISTANCE

Regardless of whether a child’s nasopharynx or throat was colonized at enrollment with no pathogens, penicillin-susceptible pathogens only, or penicillin-nonsusceptible pathogens, we found no significant differences between the tympanostomy-tube group and the medical-management group in the percentage of children colonized with any penicillin-nonsusceptible pathogen at acute otitis media follow-up or routine follow-up visits. We also found no significant between-group differences in the percentages of isolates that were nonsusceptible or in conditional odds ratios (which serve as measures of community-wide effects of antimicrobial treatment on bacterial resistance19,20) (Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). Per-protocol analysis gave similar results.

DISCUSSION

In children 6 to 35 months of age with recurrent acute otitis media, we examined the efficacy of tympanostomy-tube placement as compared with medical management in reducing the subsequent occurrence of episodes of acute otitis media. In the intention-to-treat analysis of the trial, we found no significant difference between the tympanostomy-tube group and the medical-management group in the rate of episodes of acute otitis media during the ensuing 2-year period (primary outcome measure).

With respect to most secondary outcomes, we found no significant between-group differences. In particular, despite their greater use of antimicrobial treatment, we found no evidence of increased antimicrobial resistance among the many isolates obtained from the children in the medical-management group. Differences that we did find favoring children in the tympanostomy-tube group concerned the time to a first episode of acute otitis media, various clinical findings related to the occurrence of episodes, and the percentage of children meeting specified criteria for treatment failure; however, children in the medical-management group had fewer cumulative days with otorrhea.

Our trial has certain strengths: a diverse participant population in the age group most prone to recurrences of acute otitis media, otoscopic diagnoses by validated otoscopists, pretrial confirmation in each child of at least one episode of acute otitis media, a standardized protocol for treating episodes, validated scales for rating the severity of symptoms and functional outcomes, monitoring for antimicrobial resistance, follow-up of children for 2 full years, and modest attrition. A trial limitation stems from receipt of tympanostomy tubes, for differing reasons and at differing times, by certain children in the medical-management group, thereby complicating the task of analysis.

In this trial involving children 6 to 35 months of age, all of whom had received pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, we found that tympanostomy-tube placement was not superior to medical management in reducing the rate of episodes of acute otitis media during the ensuing 2-year period.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by a grant (U01 DC013995-01A1) from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders and by the University of Pittsburgh Clinical and Translational Science Award (UL1RR024153 and UL1TR000005) from the National Center for Research Resources, now at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health.

Dr. Hoberman reports owning stock in Kaizen Bioscience, holding patent 9,636,007 B2 on a method and apparatus for aiding diagnosis of otitis media by classifying tympanic-membrane images, and holding patent 9,987,257 B2 on pediatric oral-suspension formulation of amoxicillin—clavulanate potassium and the method for use, licensed to Kaizen Bioscience; and Dr. Martin, receiving consulting fees from Merck. No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

We thank the many UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh house officers, the General Academic Pediatrics faculty and nurses who referred children to the trial, and Kris Daw, R.N., Marcia Pope, R.N., and Radhika Joshi, C.C.R.P., who helped follow children in the trial; Howard E. Rockette, Ph.D., for advice on the design of the trial; Chung-Chou H. Chang, Ph.D., for her advice on the analysis of the data; Marian G. Michaels, M.D., M.P.H., the independent safety monitor; Eugene D. Shapiro, M.D., David Tunkel, M.D., Donald Miller, M.D., Stephen J. Gange, Ph.D., and Louis Vernacchio, M.D., the members of the external data and safety monitoring board; Steven Hirschfeld, M.D., Ph.D., and Bracie Watson, Ph.D., of the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders for their leadership and administrative support; and the children and their families for their generosity and cooperation in participating in this trial.

Footnotes

The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders or the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

A data sharing statement provided by the authors is available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

A Quick Take is available at NEJM.org

REFERENCES

- 1.Finkelstein JA, Raebel MA, Nordin JD, Lakoma M, Young JG. Trends in outpatient antibiotic use in 3 health plans. Pediatrics 2019;143(1):e20181259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lieberthal AS, Carroll AE, Chonmaitree T, et al. The diagnosis and management of acute otitis media. Pediatrics 2013;131(3):e964–e999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cullen KA, Hall MJ, Golosinskiy A. Ambulatory surgery in the United States, 2006. Natl Health Stat Report 2009;(11):1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCann ME, Soriano SG. Does general anesthesia affect neurodevelopment in infants and children? BMJ 2019;367:l6459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ah-Tye C, Paradise JL, Colborn DK. Otorrhea in young children after tympanostomy-tube placement for persistent middle-ear effusion: prevalence, incidence, and duration. Pediatrics 2001;107:1251–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kay DJ, Nelson M, Rosenfeld RM. Meta-analysis of tympanostomy tube sequelae. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2001;124:374–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnston LC, Feldman HM, Paradise JL, et al. Tympanic membrane abnormalities and hearing levels at the ages of 5 and 6 years in relation to persistent otitis media and tympanostomy tube insertion in the first 3 years of life: a prospective study incorporating a randomized clinical trial. Pediatrics 2004;114(1):e58–e67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gonzalez C, Arnold JE, Woody EA, et al. Prevention of recurrent acute otitis media: chemoprophylaxis versus tympanostomy tubes. Laryngoscope 1986;96:1330–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gebhart DE. Tympanostomy tubes in the otitis media prone child. Laryngoscope 1981;91:849–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casselbrant ML, Kaleida PH, Rockette HE, et al. Efficacy of antimicrobial prophylaxis and of tympanostomy tube insertion for prevention of recurrent acute otitis media: results of a randomized clinical trial. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1992;11:278–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kujala T, Alho O-P, Luotonen J, et al. Tympanostomy with and without adenoidectomy for the prevention of recurrences of acute otitis media: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2012;31:565–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenfeld RM, Schwartz SR, Pynnonen MA, et al. Clinical practice guideline: tympanostomy tubes in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2013;149:Suppl 1:S1–S35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shaikh N, Rockette HE, Hoberman A, Kurs-Lasky M, Paradise JL. Determination of the minimal important difference for the acute otitis media severity of symptom scale. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2015;34(3):e41–e43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaleida PH, Ploof DL, Kurs-Lasky M, et al. Mastering diagnostic skills: Enhancing Proficiency in Otitis Media, a model for diagnostic skills training. Pediatrics 2009;124(4):e714–e720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoberman A, Paradise JL, Rockette HE, et al. Treatment of acute otitis media in children under 2 years of age. N Engl J Med 2011;364:105–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leibovitz E, Greenberg D, Piglansky L, et al. Recurrent acute otitis media occurring within one month from completion of antibiotic therapy: relationship to the original pathogen. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2003;22:209–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenfeld RM, Goldsmith AJ, Tetlus L, Balzano A. Quality of life for children with otitis media. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1997;123:1049–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boruk M, Lee P, Faynzilbert Y, Rosenfeld RM. Caregiver well-being and child quality of life. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2007;136:159–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lipsitch M Measuring and interpreting associations between antibiotic use and penicillin resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Clin Infect Dis 2001;32:1044–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samore MH, Lipsitch M, Alder SC, et al. Mechanisms by which antibiotics promote dissemination of resistant pneumococci in human populations. Am J Epidemiol 2006;163:160–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.