Abstract

Amphotericin B derivatives, such as MS-8209, have been evaluated as a therapeutic approach to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. We show that MS-8209, like amphotericin B, increases tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) mRNA expression and TNF-α production and consequently HIV replication in human macrophages. These effects confirm the pharmacological risk associated with the administration of amphotericin B or its derivatives to HIV-infected patients.

Macrophages and related cells play a key role in pathological events, particularly in inflammatory processes associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease. They are a major target cell for HIV, and proinflammatory monokines such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) increase HIV type 1 (HIV-1) gene expression and replication, via intracellular activation and autocrine and paracrine pathways (5, 14, 19). MS-8209 is a water-soluble derivative of amphotericin B (AmB) of lower cellular and animal toxicity and greater solubility than the parent compound (13). MS-8209 exhibits antiretroviral activity in mitogen-activated CD4+ T lymphocytes infected in vitro with HIV-1 (4, 11). MS-8209 exerts its antiviral action by inhibiting HIV entry into cells after CD4-gp120 interactions (13). AmB provokes marked overexpression of TNF-α in murine and human macrophages (10, 15, 17). In view of the deleterious effects of TNF-α on HIV replication, it was therefore of interest to investigate the possible effects of MS-8209 on TNF-α synthesis and HIV replication in macrophages.

We obtained human macrophages by 7-day differentiation of freshly isolated monocytes. Monocytes were separated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells using countercurrent centrifugal elutriation. Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, and 1% triantibiotic mixture (penicillin, neomycin, and streptomycin). Cell culture medium was endotoxin free, as shown by the Limulus amebocyte lysate test. To study the effects of MS-8209 on TNF-α synthesis, monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM) were exposed to various concentrations of MS-8209 (0, 5, and 10 μM) for 24 h, during which TNF-α was measured in cell supernatants by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and its mRNA was quantified by reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) (1). To investigate the effects of MS-8209 on HIV replication, 1 million MDM were infected in vitro with 10,000 50% tissue culture infective doses of either the reference macrophage-tropic HIV-1/Ba-L strain or the primary HIV-1-DAS isolate. TNF-α and viral replication were measured throughout the culture in cell supernatants by ELISA and by dosing RT activity, respectively, as previously described (7). In these last experiments, cell culture medium and MS-8209 (0, 1, 5, and 10 μM) were renewed twice a week.

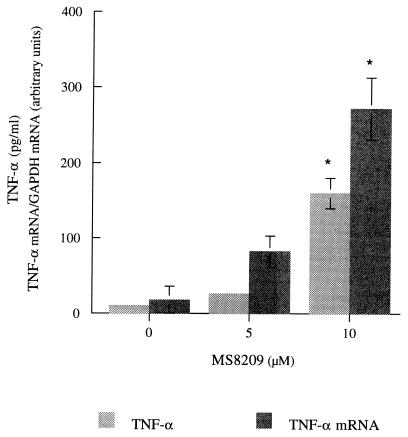

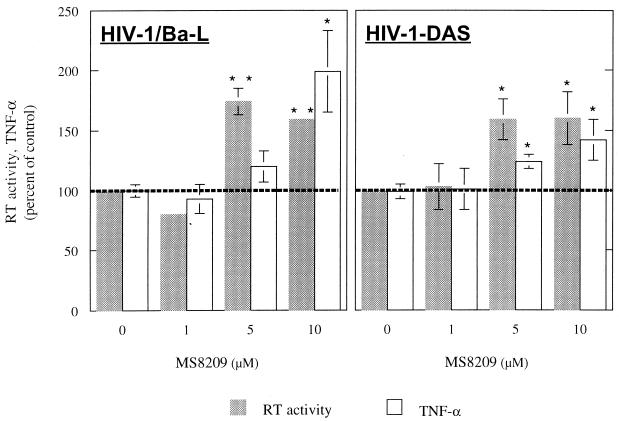

MS-8209 dose dependently increased TNF-α synthesis and TNF-α mRNA expression during the first 24 h of MDM treatment (Fig. 1). In long-term experiments, a dose-dependent increase in TNF-α synthesis was also observed in response to MS-8209. HIV-1/Ba-L and -DAS replicated efficiently in our MDM cultures (7). The significant increase in HIV-1 replication induced by 5 and 10 μM MS-8209 was correlated with the overexpression of TNF-α (Fig. 2) but unlike the increase in TNF-α synthesis was not dose dependent, suggesting that it was only a consequence of TNF-α and not of its concentration. Similar results were observed with cells isolated from a second blood donor and another AmB derivative (MS-1191 [data not shown]). Furthermore, we have previously described the increase in HIV-1/Ba-L replication associated with the overexpression of TNF-α in in vitro-infected MDM treated with dapsone (8). Increased mortality was suspected for HIV-infected patients receiving dapsone as prophylaxis for Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia and toxoplasmic encephalitis (16).

FIG. 1.

TNF-α mRNA expression and TNF-α production in uninfected MDM treated for 24 h with MS-8209. RNAs were quantified using a noncompetitive RT-PCR (1), and the cytokine was detected in cell culture supernatants by ELISA (Immunotech, Luminy, France). Results are expressed as the means ± standard deviations of three different culture wells. This experiment was performed using cells from one given donor, and identical results were observed with cells isolated from a second donor. Data were analyzed using an unpaired t test (Statview microcomputer software; Abacus Concept Inc., Berkeley, Calif.). Differences were considered to be significant at P < 0.01 (∗∗) or P < 0.05 (∗). GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

FIG. 2.

RT activity and TNF-α in culture supernatants of MDM treated with 1, 5, and 10 μM MS-8209. MDM were treated throughout the culture and infected either with the reference macrophage-tropic HIV-1/Ba-L strain or with the primary macrophage-tropic HIV-1-DAS isolate (10,000 50% tissue culture infective doses). HIV replication was assessed throughout the culture by the assay of RT activity using the RetroSys kit (Innovagen, Lund, Sweden). TNF-α was measured in cell culture supernatants of uninfected MDM by ELISA. Each point is the mean ± standard deviation of results from three different culture wells. This experiment was performed using cells from one given cell donor, and identical results were observed with cells from a second blood donor. Data were analyzed using an unpaired t test. Differences were considered to be significant at P < 0.01 (∗∗) or P < 0.05 (∗).

These results obtained with AmB derivatives are consistent with previously published data showing an increase in TNF-α synthesis after exposure of murine and human macrophages to AmB (10, 15, 17) and TNF-α-induced enhancement of HIV replication (19). Like AmB, its derivatives may have contrasting effects on the cell population studied, i.e., macrophages or T cells (4). In vivo use of AmB derivatives could therefore be unsuccessful in HIV infection. More particularly, the enhancement of HIV replication in MDM could account for the relative inefficiency of MS-8209 in simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) mac251-infected macaques, especially since our SIVmac251 isolate infects cells of the macrophage lineage (unpublished data). Moreover, this TNF-α overexpression could explain the deleterious or beneficial effects of AmB observed for other infections. Elevated intracranial pressure is a sometimes-fatal adverse reaction in HIV-infected patients treated with AmB for cryptococcal meningitis (18), and TNF-α amplifies contraction of cerebral arteries (9). Low intracellular catalase levels exacerbate AmB-related toxicity and interfere with AmB's efficacy in mice infected with the bacterium Listeria monocytogenes (2). As TNF-α increases the synthesis of superoxide dismutase, which produces the substrate of catalase, i.e., hydrogen peroxide, high hydrogen peroxide levels may exceed catalase's capacity and have effects similar to those of low catalase levels.

It is likely that the effects of AmB derivatives are mediated by NF-κB, a transcription factor of the NF-κB–Rel family which regulates the expression of numerous cellular genes, particularly those involved in the inflammatory response, such as TNF-α (3), and of HIV provirus through its binding sites in the HIV long terminal repeat promoter (6). Even though the role of other IκB proteins remains unclear, NF-κB is activated by TNF-α and a pathogenic agent such as HIV using this activation pathway. Its specific inhibitor subunit IκBα is phosphorylated, the cytoplasmic NF-κB–IκB complex is then disrupted, and NF-κB is translocated into the nucleus, where it can bind to its specific binding sites. By enhancing HIV replication and TNF-α synthesis in cells of macrophage lineage, AmB derivatives could induce neurological disorders in HIV-infected patients. The neuropathogenesis of HIV infection is governed by HIV replication in mononuclear phagocytes, the production of viral and cellular components mediating inflammation and neurotoxicity, and neuronal injury and death. TNF-α participates in inflammation and induces neuronal apoptosis through the platelet activating factor (12).

Although the precise mode of action of AmB and its derivatives is not well understood, our study confirms that they interfere with the macrophage activation state and its ability to produce proinflammatory cytokines and should be used carefully in management of HIV-infected patients.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Centre de Transfusion Sanguine des Armées (CTSA; Clamart, France) and the Service de Cytaphérèse de l'Hôpital Saint-Louis (Paris, France).

This work was supported by the Agence Nationale de Recherches sur le SIDA (ANRS; Paris, France), the Institut de Formation Supérieure Biomédicale (IFSBM; Villejuif, France), the Association pour la Recherche en Neurovirologie (ARN; Griselles, France), the Association Claude Bernard (Paris, France), the Association Naturalia-Biologia (Paris, France), and the Ministère de l'Education Nationale, de la Recherche et de la Technologie (Action Concertée 10, Paris, France).

REFERENCES

- 1.Benveniste O, Martin M, Villinger F, Dormont D. Techniques for quantification of cytokine mRNAs. Cytokines Cell Mol Ther. 1998;4:207–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brajtburg J, Elberg S, Kobayashi G S, Medoff G. Toxicity and induction of resistance to Listeria monocytogenes infection by amphotericin B in inbred strains of mice. Infect Immun. 1986;54:303–307. doi: 10.1128/iai.54.2.303-307.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brennan P, O'Neill L A J. Effects of oxidants and antioxidants on nuclear factor κB activation in three different cell lines: evidence against a universal hypothesis involving oxygen radicals. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1260:167–175. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(94)00186-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cefai D, Hadida F, Jung M, Debré P, Vernin J G, Seman M. MS-8209, a new amphotericin B derivative that inhibits HIV-1 replication in vitro and restores T-cell activation via the CD3/TcR in HIV-infected CD4+ cells. AIDS. 1991;5:1453–1461. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199112000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clayette P, Dereuddre-Bosquet N, Martin M, Fretier P, Dormont D. Effects of RP55778, a tumor necrosis factor alpha synthesis inhibitor, on antiviral activity of dideoxynucleosides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:875–877. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.4.875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeLuca C, Kwon H, Pelletier N, Wainberg M A, Hiscott J. NF-kappaB protects HIV-1-infected myeloid cells from apoptosis. Virology. 1998;244:27–38. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dereuddre-Bosquet N, Clayette P, Martin M, Benveniste O, Fretier P, Jaccard P, Vaslin B, Lebeaut A, Dormont D. Lack of interleukin-10 expression in monocyte-derived macrophages in response to in vitro infection by HIV type 1 isolates. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1997;13:961–966. doi: 10.1089/aid.1997.13.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duval X, Clayette P, Dereuddre-Bosquet N, Fretier P, Martin M, Salmon-Céron D, Gras G, Vildé J L, Dormont D. Dapsone and HIV-1 replication in primary cultures of lymphocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages. AIDS. 1997;11:943–944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leseth K H, Adner M, Berg H K, White L R, Aasly J, Edvinsson L. Cytokines increase endothelin ETB receptor contractile activity in rat cerebral artery. Neuroreport. 1999;10:2355–2359. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199908020-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Louie A, Baltch A, Franke M, Smith R, Gordon M. Comparative capacity of four antifungal agents to stimulate murine macrophages to produce tumor necrosis factor alpha: an effect that is attenuated by pentoxifylline, liposomal vesicles, and dexamethasone. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1994;34:975–987. doi: 10.1093/jac/34.6.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magierowska-Jung M, Cefai D, Marrakchi H, Chieze F, Agut H, Huraux J M, Seman M. In vitro determination of antiviral activity of MS-8209, a new amphotericin B derivative, against primary isolates of HIV-1. Res Virol. 1996;147:313–318. doi: 10.1016/0923-2516(96)82289-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perry S W, Hamilton J A, Tjoelker L W, Dbaibo G, Dzenko K A, Epstein L G, Hannun Y, Whittaker J S, Dewhurst S, Gelbard H A. Platelet-activating factor receptor activation. An initiator step in HIV-1 neuropathogenesis. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:17660–17664. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.28.17660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pleskoff O, Seman M, Alizon M. Amphotericin B derivative blocks human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry after CD4 binding: effect on virus-cell fusion but not on cell-cell fusion. J Virol. 1995;69:570–574. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.1.570-574.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poli G, Kinter A, Justement J, Kerhrl J, Bressler P, Stanley S, Fauci A. Tumor necrosis factor alpha function in an autocrine manner in the induction of human immunodeficiency virus expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:782–785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.2.782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rogers D P, Jenkins J K, Chapman S W, Ndebele K, Chapman B A, Cleary J D. Amphotericin B activation of human genes encoding for cytokines. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1726–1733. doi: 10.1086/314495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salmon-Céron D, Fontbonne A, Saba J, May T, Raffi F, Chidiac C, Patey O, Aboulker J P, Schwartz D, Vildé J L. Lower survival in AIDS patients receiving dapsone compared with aerosolized pentamidine for secondary prophylaxis of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:656–664. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.3.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tokuda Y, Tsuji M, Yamazaki M, Kimura S, Abe S, Yamaguchi H. Augmentation of murine tumor necrosis factor production by amphotericin B in vitro and in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:2228–2230. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.10.2228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Horst C M, Saag M S, Cloud G A, Hamill R J, Graybill J R, Sobel J D, Johnson P C, Tuazon C U, Kerkering T, Moskovitz B L, Powderly W G, Dismukes W E. Treatment of cryptococcal meningitis associated with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group and AIDS Clinical Trials Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:15–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199707033370103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vyakarnam A, McKeating J, Meager A, Beverley P. Tumor necrosis factor (α, β) induced by HIV-1 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells potentiate virus replication. AIDS. 1990;4:21–27. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199001000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]