Abstract

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is one of the prevalent neurological disorder which is drawing increased attention over the past few decades. Major risk factors for PTSD can be categorized into environmental and genetic factors. Among the genetic risk factors, polymorphisms in the catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) gene is known to be associated with the risk for PTSD. In the present study, we analysed the impact of deleterious single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the COMT gene conferring risk to PTSD using computational based approaches followed by molecular dynamic simulations. The data on COMT gene associated with PTSD were collected from several databases including Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) search. Datasets related to SNP were downloaded from the dbSNP database. To study the structural and dynamic effects of COMT wild type and mutant forms, we performed molecular dynamics simulations (MD simulations) at a time scale of 300 ns. Results from screening the SNPs using the computational tools SIFT and Polyphen-2 demonstrated that the SNP rs4680 (V158M) in COMT has a deleterious effect with phenotype in PTSD. Results from the MD simulations showed that there is some major fluctuations in the structural features including root mean square deviation (RMSD), radius of gyration (Rg), root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) and secondary structural elements including α-helices, sheets and turns between wild-type (WT) and mutant forms of COMT protein. In conclusion, our study provides novel insights into the deleterious effects and impact of V158M mutation on COMT protein structure which plays a key role in PTSD.

Keywords: Catechol-O-Methyltransferase (COMT), Molecular dynamic simulations (MD simulations), Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), Molecular modelling, Mutation

1. Introduction

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a chronic psychiatric disorder known to be prevalent in high-income countries with an estimated lifetime prevalence of around 7.8%(Kessler et al., 1995). According to National Comorbidity Survey, women are more than twice likely to have PTSD with a prevalence percentage being 10.4 compared to men with a prevalence percentage of 5 at some point in their lives(Kessler et al., 1995). It is demonstrated to be a strong comorbid factor with other lifetime DSM–III–R disorders. Some of the major symptoms of this disorder include intrusive recollection, emotional numbness, nightmares, hyperarousal, and disturbed sleep(El-Solh et al., 2018).

Previously, several studies showed different genes and their respective single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with PTSD. Among the genes, catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) is a significant enzyme involved in the metabolism of catechol-like compounds including catecholamines, catechol estrogens, and L-dopa(Nissinen and Mannisto, 2010). It catalyzes the transfer of a methyl group from S-adenosylmethionine to catecholamines such as neurotransmitters dopamine, epinephrine, and norepinephrine..

COMT is an important phase II enzyme involved in the metabolism of catecholamines, catecholestrogens, L-dopa, and other drugs with catechol structure(Nissinen and Mannisto, 2010). Inhibitors of COMT represent a new class of drugs in the treatment of hypertension, asthma, and Parkinson’s disease(Tai and Wu, 2002). COMT is encoded by the gene COMT on chromosome 22q11.2. It enzymatically inactivates the catecholamine neurotransmitters, such as epinephrine, norepinephrine, and dopamine, through 3-O-methylation of the benzene ring(Witte and Floel, 2012). COMT exists in two forms including a soluble form (S-COMT) located in the cytosol and a membrane-bound form (MB-COMT) that is anchored to the rough endoplasmic reticulum. Among these two forms, S-COMT predominates in most tissues while MB-COMT is predominant in the brain(Ma et al., 2014). It has been shown that hydroxyestradiol is a substrate for the COMT and that COMT transmethylates hydroxyestradiol into 2-methoxyestradiol (2-ME) (Kanasaki et al., 2017). Decreased COMT transcript levels are known to be associated with the epigenetic changes in breast cancer (Wu et al., 2019). Additionally, 2-ME has anti-inflammatory and anti-osteoporotic effects(Stubelius et al., 2012). Thus, COMT may play a role in the regulation of inflammation. Previous studies from our laboratory have shown that PTSD patients exhibit enhanced inflammation(Bam et al., 2016a, 2016b, 2017; Chitrala et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2014). It is for this reason that in the present study, we analysed the impact of Val158Met mutation induced by deleterious SNP in COMT conferring risk to PTSD. Further, several studies have used the molecular dynamic (MD) simulations to show the impact of the mutation on the protein (Gupta et al., 2020; Junaid et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020) and specifically on COMT protein using computational approaches (Cao et al., 2014; Govindasamy et al., 2019; Kanaan et al., 2008; Magarkar et al., 2018; Orlowski et al., 2011; Patel et al., 2018; Patra et al., 2016; Rutherford and Daggett, 2009; Yang et al., 2019). In the present study, we utilized a similar computational approach to elucidate the impact of Val158Met on the COMT protein.

2. Methods

2.1. Data mining

Extensive data mining search for genes and SNPs associated with PTSD was performed using online available medical research databases including OMIM (Amberger et al., 2009), Medline(Xuan et al., 2007), PubMed and other multidisciplinary bibliographic databases(Gasparyan et al., 2013) (search was conducted in September 2017).

2.2. SNP datasets

The SNP information for COMT gene was downloaded from the dbSNP (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/, access date: May 8, 2018) (Sherry et al., 2001), a database that currently classifies nucleotide sequence variations into 99.77% of single nucleotide substitutions, 0.21% of small insertion/deletion polymorphisms, 0.02% of invariant regions of sequence, 0.001% of microsatellite repeats, <0.001% of named variants and <0.001% of uncharacterized heterozygous assays (Sherry et al., 2001). The frequency data for respective missense SNPs present in COMT gene was obtained from the 1000 Genomes Project (phase I) (http://www.1000genomes.org) (Genomes Project et al., 2012) which is a publicly available database. The variant format file (phase 3) in 1000 Genomes project corresponding to the 22nd chromosome contains the frequencies for SNPs recognized in the genome of 2504 individuals from 32 populations obtained by different dense SNP genotype data methods with a predominant component of ancestry divided into five major super-population types. These include African (AFR) (661 samples), American (AMR) (347 samples), East Asian (EAS) (504 samples), European (EUR) (503 samples) and South Asian (SAS) (489 samples).

2.3. Prediction of deleterious SNPs in COMT

To evaluate and analyse the potential functional impact of missense SNPs in COMT gene, we have utilized the following database servers i) ‘Sorting Tolerant From Intolerant’ (SIFT) ii) ‘Polymorphism Phenotyping v2’ (Polyphen-2). SIFT is an algorithm that uses sequence homology to predict the potential impact of amino acid substitutions on protein function and frameshifting indels(Hu and Ng, 2012). SIFT has been widely used to study the effects of missense mutations in several human studies such as Genetics, Cancer, Mendelian and infectious diseases as well as several other species studies such as agricultural plants, rats, canines and Arabidopsis(Sim et al., 2012). SIFT scores the position of the amino acid substitutions in a protein which affect the protein function with a normalized probability <0.05 as deleterious and those with a normalized probability ≥0.05 as tolerated(Ng and Henikoff, 2001 (Ng and Henikoff, 2003). We have submitted dbSNP id for our analysis to SIFT web server. PolyPhen-2 is a tool to calculate the potential impact of amino acid substitutions on protein structure and function in human proteins by using ng physical and comparative methods. Some of the major functions it performs include annotation of SNPs, mapping the coding SNPs to gene transcripts, extracting the annotations and structure related attributes for protein sequences, and building the conservation profiles followed by estimating the probability of a missense mutation being damaging or not by combing all these properties. It integrates the annotations from UCSC Genome Browserhuman genome and MultiZ multiple alignments for vertebrate genomes. It employs machine-learning classification for high-quality multiple protein sequence alignment pipeline and a prediction(Adzhubei et al., 2013). For our analysis, we used WHESS.db which is a quick accessible interface for precomputed set in PolyPhen-2 predictions(Adzhubei et al., 2013). We submitted dbSNP id for analysing the impact of missense mutations in COMT gene using Polyphen-2 sever.

2.4. MD simulations

The crystal Structure of human Catechol O-Methyltransferase with bound S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), 3,5-dinitrocatechol (DNC), Magnesium (Mg2+) and Potassium (K+) ion (PDB ID: 3BWM) (Rutherford et al., 2008) was used as a beginning structure for our MD simulations. All the ligands and all the crystal water molecules were removed from the protein before it was subjected to simulations. The resultant structure was subjected to 1000 steps of energy minimization to minimize the energies including torsional, electrostatic and van der Waals for the resultant structures in vacuo. The structure for V158M mutation was generated using pymol. For performing MD simulations, we used GROMACS 5.1.4 package(Van Der Spoel et al., 2005). We solvated the system by explicitly adding flexible TIP3P water model by embedding in a cubic box with walls being located at a distance of 10 Å from all protein atoms. To neutralize the total charge of the system we added the Cl counter ions. For the force field, we used the OPLS-AA (Optimized Parameters for Liquid Simulations; AA stands for all-atom) potential set (Murzyn et al., 2013). Each solvated structure was subjected to energy minimization for 50000 steps of steepest descent minimization terminating when maximum force is found smaller than 1000 kJ/mol‒1/nm‒1. After energy minimization, the system was subjected to an equilibration at constant temperature of 300K and pressure of 1 bar with a time step of 2 fs and non-bonded pair list updated every 5 steps under the conditions of position restraints for heavy atoms and LINCS constraints(Hess et al., 1997) for all bonds. Constant temperature conditions were maintained using a Berendsen thermostat. We used the particle mesh Ewald summation method to calculate the electrostatic interaction. Finally, performed two (WT, V158M) 300 nano seconds MD simulations.

2.5. Analysis of trajectories from molecular dynamic simulations

Deviations in structures of native and mutant proteins were computed using the built in functions of GROMACS package such as g_rmsf, g_rms and g_gyrate. We employed a cut-off radius of 0.35 nm among donor and acceptor to compute the average number of hydrogen bonds (protein–solvent intermolecular) using g_hbond parameter. The density maps were calculated using g_densmap function whereas the respective average values of the output from simulation data generated during the MD simulations was plotted using the g_analyze parameter of GROMACS package. We used the GRACE software (http://plasma-gate.weizmann.ac.il/Grace/) for plotting the respective graphs.

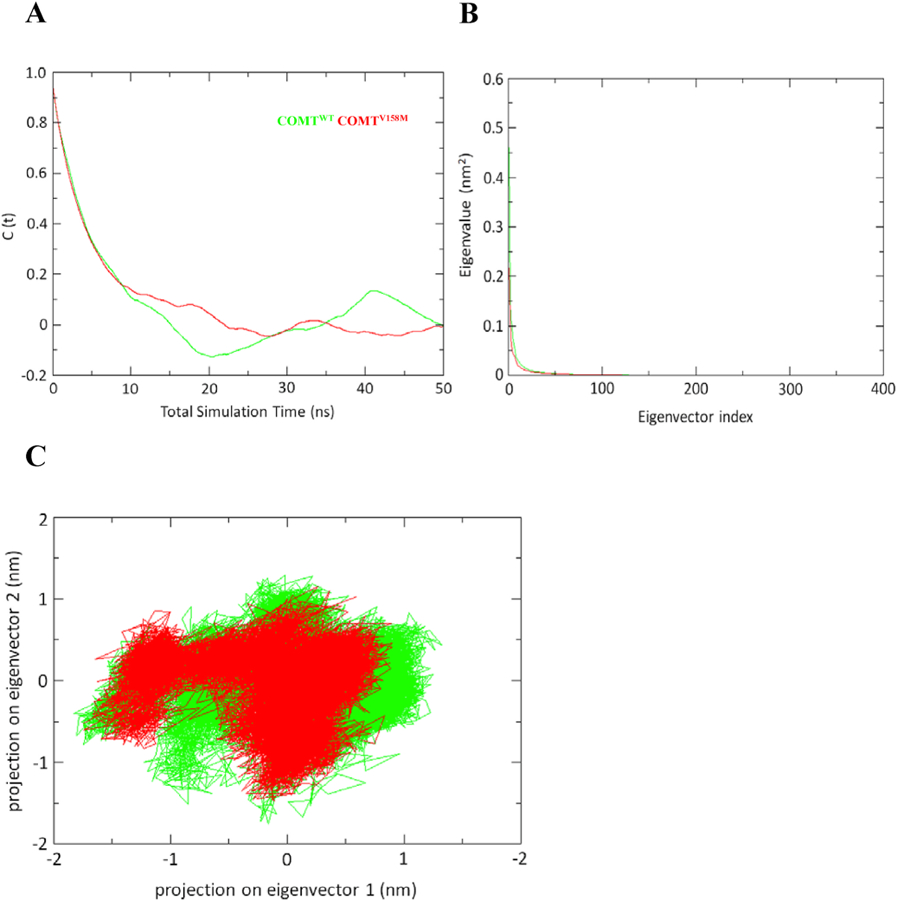

2.6. Analysis of principal components

Essential dynamics (ED) was used to analyse the global motion in the simulations, according to the steps described in the GROMACS software package (Van Der Spoel et al., 2005). ED also called as covariance or principle component analysis isolates the respective correlated motions of a protein thereby allowing us to recognize the motions that are most essential to its activity. In general, ED is used to characterize the large scale collective motions of a protein. In our study, the Cα atoms trajectory was used to construct the covariance matrices in WT and MT simulations. Previously it has been shown that covariance matrices contain all the evidence to describe sufficient large concerted motion of a protein [32]. Gromacs utilities such as g_covar, g_anaeig were used to analyse their respective trajectories.

2.7. Computing specifications

All MD simulations performed in the present study was done using High Performance Computing cluster at University of South Carolina and Comet XSEDE cluster facility at Xsede high performance computing resource portal. Calculations such as ensemble analysis, trajectory analysis and other calculations related to this study was performed on a local computer.

2.8. Statistical analysis

All the statistical procedures related to the present study was performed using Microsoft Office Excel and Graph-Pad Prism 6.01 software.

3. Results

3.1. Study selection

A data search using the specific keywords “Post-traumatic stress disorder,” “single nucleotide polymorphism,” “disease,” and “missense SNPs” was performed. An additional search on the bibliographic database search engines with the same and additional keywords such as “clinical trials”, “immune system”, “inflammation” and “therapy” was also performed. Results from our search showed some of the SNPs that are risk factors for PTSD (Table 1). Among the genes that showed risk towards PTSD as shown in Table 1, we selected COMT for our study.

Table 1.

List of Single nucleotide polymorphisms in genes associated with PTSD.

| dbSNP ID | Gene symbol | Mutation | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| rs4680 | Catechol-o-methyltransferase (COMT) | Val158Met | Winkler et al. (2016) |

| rs324420 | Human fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) gene | Pro129Thr | Spagnolo et al. (2016) |

| rs6779753 | Neuroligin1(NLGN1) | – | Kilaru et al. (2016) |

| rs6602398 | Interleukin 2 receptor subunit alpha (IL2RA) | – | Powers et al. (2016) |

| rs159572 | Ankyrin repeat domain 55(ANKRD55) | – | Stein et al. (2016) |

| rs17228616 | Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | – | Lin et al. (2016) |

| rs7208505 | Spindle and kinetochore associated complex subunit 2 (SKA2) | – | Sadeh et al. (2016) |

| rs1360780, rs9470080 | FK506 binding protein 5 (FKBP5) | – | Castro-Vale et al. (2016); Fani et al. (2016); Scheuer et al. (2016) |

| rs6295 | 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 1A (HTR1A) | – | Donaldson et al. (2016) |

| rs10144436 | Dicer 1, ribonuclease III (DICER1) | – | Wingo et al. (2015) |

| rs1799923 | Cholecystokinin (CCK) | – | Badour et al. (2015) |

| rs1042357, rs10852889 | Arachidonate 12-lipoxygenase, 12S type (ALOX12) | – | Miller et al. (2015) |

| rs2075652 | Dopamine receptor D2 (DRD2) | – | Duan et al. (2015) |

| rs7208505 | Spindle and kinetochore associated complex subunit 2 (SKA2) | – | Sadeh et al. (2016) |

| rs12898919 | Cholinergic receptor nicotinic alpha 5 subunit (CHRNA5) | – | Kimbrel et al. (2015) |

| rs2242446 | Solute carrier family 6 member 2 (SLC6A2) | – | Pietrzak et al. (2015) |

| rs1130864 | C-reactive protein (CRP) | – | Michopoulos et al. (2015) |

| rs10739062 | Solute carrier family 1 member 1(SLC1A1) | – | Zhang et al. (2014) |

| rs2400707 | Adrenoceptor beta 2 (ADRB2) | – | Liberzon et al. (2014) |

| rs2134655, rs201252087, rs4646996, rs9868039 | Dopamine receptor D3 (DRD3) | – | Wolf et al. (2014) |

| rs4790904 | Protein Kinase C Alpha (PRKCA) | – | Liu et al. (2013) |

| rs363276 | Solute carrier family 18 member A2 (SLC18A2) | – | Solovieff et al. (2014) |

| rs2267715, rs2284218 | Corticotropin releasing hormone receptor 2 (CRHR-2) | – | Wolf et al. (2013) |

| rs6265 | Brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) | Val66Met | Rakofsky et al. (2012) |

| rs12944712 | Corticotropin releasing hormone receptor 1 (CRHR1) | – | Amstadter et al. (2011) |

| rs2267735 | ADCYAP receptor type I (ADCYAP1R1) | – | Ressler et al. (2011) |

| rs4606 | Regulator of G protein signalling 2 (RGS2) | – | Amstadter et al. (2009) |

3.2. Frequency and distribution of SNPs in COMT gene

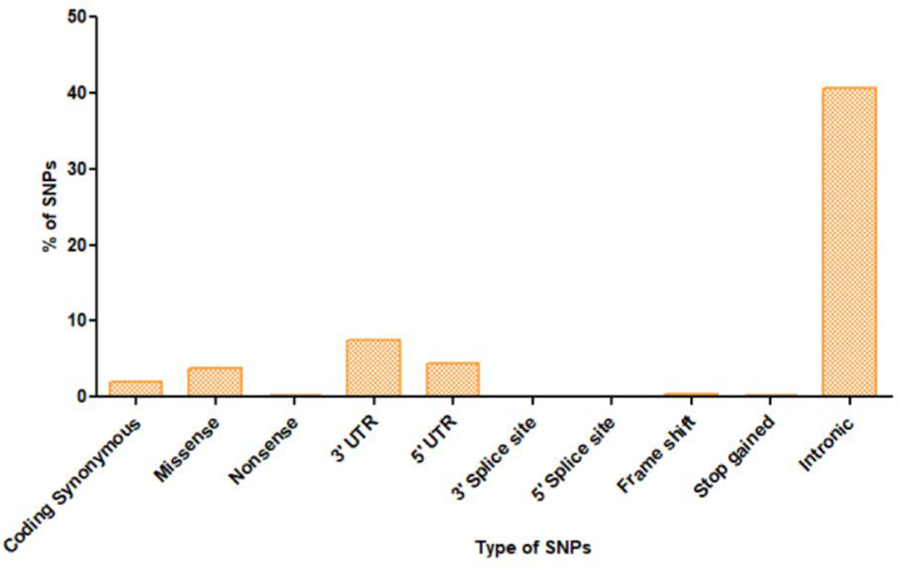

Among the 7771 SNPs of COMT gene validated and deposited in dbSNP, 159 are coding synonymous, 295 are missense, 18 are nonsense, 579 are 3′ UTR, 336 are 5′ UTR, 4 are 3′ splice site, 5 are 5′ splice site, 28 are frameshift, 18 are stop gained and 3155 are intronic variants. The distribution of SNPs in coding synonymous, missense, nonsense, 3′ UTR, 5′ UTR, 3′ splice site, 5′ splice site, frameshift, stop gained and intronic regions of COMT gene is shown in Fig. 1. Information about the rate distribution of all missense SNPs in COMT gene that were obtained from the1000 Genomes Project is represented in the Additional File 1: Table S1.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of SNPs in COMT gene. Represents the distribution of coding synonymous (2.04%), missense (3.79%), nonsense (0.23%), 3′ UTR (7.45%), 5′ UTR (4.32%), 3′ splice site (0.05%), 5′ splice site (0.06%), frame shift (0.36%), stop gained (0.23%) and intronic (40.59%) SNPs in COMT gene.

3.3. Deleterious missense SNPs in COMT gene

Among the 295 missense SNPs from dbSNP, 12 SNPs showed scores predicted with SIFT server. Among these 12 SNPs that were scored by the SIFT server, we found five as deleterious with a tolerance index score of less than or equal to 0.05. Among these predicted deleterious SNPs, two were highly deleterious with a tolerance index score of 0.00 using orthologues and homologues in the protein alignment and the remaining three were deleterious with a tolerance index score of 0.05, 0.01 and 0.02 using orthologues and homologues in the protein alignment respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Functionally significant missense SNPs in COMT predicted using the SIFT Server.

| dbSNP ID | Amino acid change | Nucleotide change | Protein ID | Tolerance Index |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Using orthologues in the Protein alignment | Using homologues in the Protein alignment | ||||

| rs4680 | V158M | A/G | NP_000745 | 0.05 | 0.07 |

| rs6267 | A72S | A/G/T | NP_000745 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| rs6270 | C34S | C/G | NP_000745 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| rs4986871 | A146V | C/T | NP_000745 | 0.09 | 0 |

| rs5031015 | A102T | A/G | NP_000745 | 0.57 | 0.32 |

| rs11544670 | L9F | G/T | NP_000745 | 0 | 0 |

| rs13306279 | P199L | C/T | NP_000745 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| rs13306281 | V92M | A/G | NP_000745 | 0.12 | 0 |

| rs45593642 | R14L | A/C | NP_006431 | 0.23 | 0.34 |

| rs61910731 | V100L | A/C/G/T | NP_000745 | 1 | 1 |

| rs75012854 | N39D | A/G | NP_000745 | 0.23 | 0.3 |

| rs76452330 | D94N | A/G | NP_000745 | 0.18 | 0.08 |

We have submitted the 12 SNPs that showed scoring using orthologues and homologues in the protein alignment by SIFT server to Polyphen-2 to assess their respective functional significance in allele replacement. Results form Polyphen-2 prediction showed SNPs, rs4680 and rs6267 as possibly damaging, SNPs rs13306279, rs13306281 and rs4986871 also as probably damaging whereas the other SNPs rs6270, rs5031015, rs11544670, rs45593642, rs61910731, rs75012854 and rs76452330 as benign (Table 3). Overall, results showed that five SNPs (rs4680, rs6267, rs4986871, rs13306279, rs13306281) were predicted to be deleterious or probably/possibly damaging using SIFT and Polyphen-2 servers. Results from our literature search showed that SNP rs4680 (V158M) is linked with PTSD associated functional outcome following mild traumatic brain injury (Table 1) (Winkler et al., 2016) and other mechanisms (Deslauriers et al., 2018; Hayes et al., 2017; Winkler et al., 2016). Therefore, we selected this SNP for further analysis.

Table 3.

Functionally significant SNPs predicted using the Polyphen-2 server.

| dbSNP ID | Amino acid change | Nucleotide change | HDivPred | HDiv Prob | HvarPred | HvarProb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs4680 | V158M | A/G | Possibly damaging | 0.608 | Benign | 0.072 |

| rs6267 | A72S | A/G/T | Possibly damaging | 0.743 | Possibly damaging | 0.507 |

| rs6270 | C34S | C/G | Benign | 0.009 | Benign | 0.001 |

| rs4986871 | A146V | C/T | Probably damaging | 0.995 | Probably damaging | 0.951 |

| rs5031015 | A102T | A/G | Benign | 0.031 | Benign | 0.007 |

| rs11544670 | L9F | G/T | Benign | 0.062 | Benign | 0.023 |

| rs13306279 | P199L | C/T | Probably damaging | 0.999 | Probably damaging | 0.913 |

| rs13306281 | V92M | A/G | Probably damaging | 1 | Probably damaging | 0.984 |

| rs45593642 | R14L | A/C | Benign | 0 | Benign | 0 |

| rs61910731 | V100L | A/C/G/T | Benign | 0.003 | Benign | 0.003 |

| rs75012854 | N39D | A/G | Benign | 0.222 | Benign | 0.039 |

| rs76452330 | D94N | A/G | Benign | 0.104 | Benign | 0.04 |

3.4. Impact of deleterious missense SNP on COMT protein

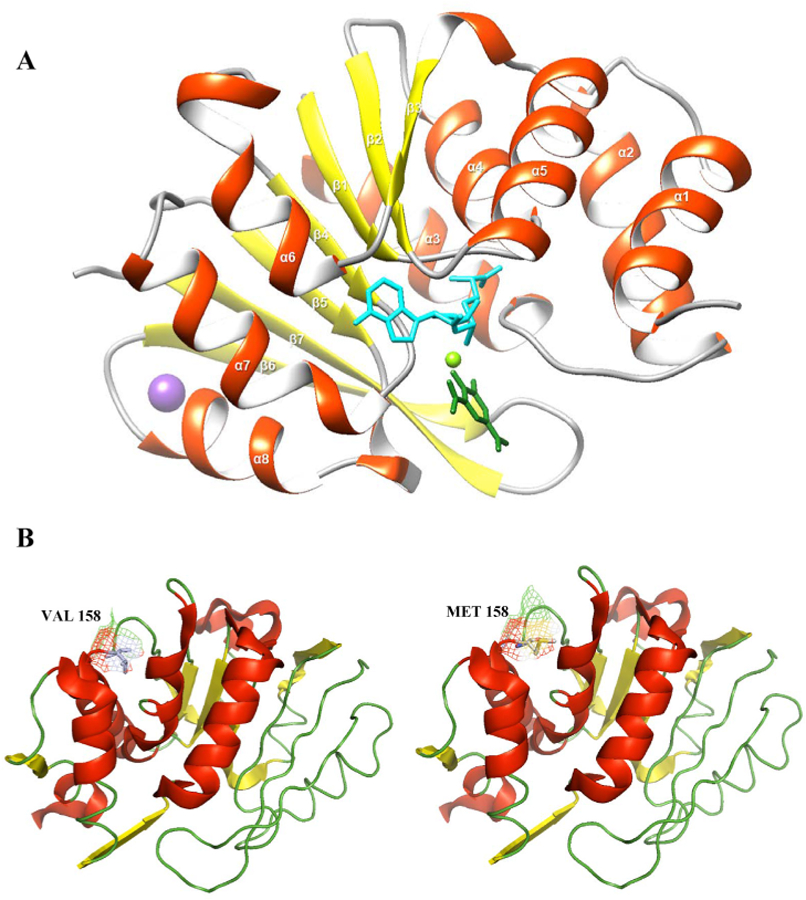

The crystal structure of human COMT consists of a seven-stranded β-sheet core (3↑2↑1↑4↑5↑7↓6↑) sandwiched between two sets of α-helices i.e., (helices α1–α5 on one side and helices α6–α8 on the other side) (PDB ID: 3BWM) (Fig. 2A) (Rutherford et al., 2008). The three-dimensional structure of COMT shows S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), Mg2+ and the inhibitor 3,5-dinitrocatechol (DNC) bound to the superficial clefts on the protein surface (Fig. 2A). Respective interactions of SAM, Mg2+, and the DNC inhibitor were provided in Additional File 2: Fig. S1. The structural features of COMT that are elucidated based on crystallography, can provide sufficient knowledge about the loss-of-function induced by the mutations. The function of a protein primarily depends on its dynamic nature. Though the static structure of a protein estimated using techniques such as crystallography is useful for understanding the loss of function, it doesn’t provide any details regarding its dynamic properties. To bridge this gap, we performed MD simulations (300 ns) to investigate the dynamic nature of COMT protein with respect to loss-of-function mutation V158M induced by themissense SNP rs4680 in COMT protein. We have generated the native and mutant forms (Fig. 2B) of the COMT structure and subjected them to 300 ns MD simulations each.

Fig. 2.

Structure of COMT. a) Cartoon structure of the human COMT structure (PDB ID: 3BWM). Helices shown in deep orange color, flat ribbons, strands shown in yellow, and coils shown in deep gray color. Ligand S-adenosyl-L-methionine co-substrate (SAM) shown in cyan, Potassium shown in purple ball, 3,5-Dinitrocatechol (DNC) is shown in green, Magnesium shown in green ball. Visualization of these structures was performed using UCSF Chimera. b) Upper panel represents the WT COMT whereas lower panel represents the mutant V158M COMT protein with helices shown in red color, strands shown in yellow and coils shown in green color cartoon. Visualization of these structures was performed using pymol. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

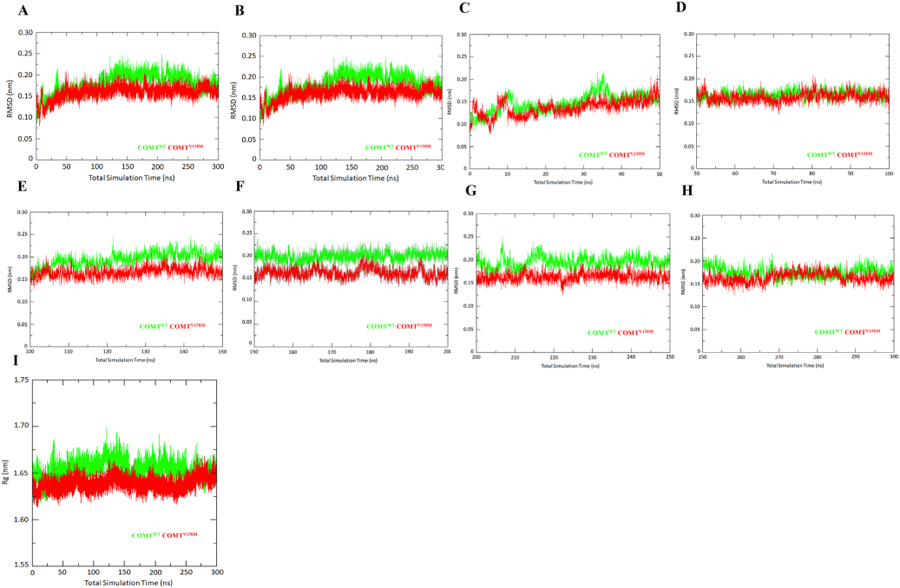

To analyse the average distance between the selected atoms of superimposed biomolecules, thereby assessing the closeness between three-dimensional structures and to measure the differences in movement between native and variant backbones, we have conducted the root mean-square deviation (RMSD) analysis. RMSD is generally used to determine the stability of the protein relative to its conformation based on the deviations produced during its simulation. The smaller the deviation, the greater is the stability of the protein structure. We have calculated the RMSD value for the backbone and C-alpha atoms of the native and WT type COMT protein during the 300 ns simulation to examine for stability. From the results of the RMSD simulation of backbone and C-alpha atoms through 300 ns simulation shown in Fig. 3A and B it can be noticed that the wild type COMT protein showed equilibrium after 100 ns in backbone (Fig. 3A) and C-alpha (Fig. 3B) atoms. However, fluctuations were visible throughout simulation with the structure preserving at a level of 0.20 nm after 100 ns. In the case of the V158M mutant, equilibration was shown around 75 ns and the system continued stable until 250 ns at 0.15 nm during the course of simulation in the backbone (Fig. 3A) and C-alpha (Fig. 3B). The RMSD simulation demonstrated that the V158M mutant retained overall stability during the course of simulation while the wild type exhibited more fluctuations. In case of backbone atoms, the RMSDs of both WT and MT showed non-equilibration during the first 50 ns simulation (Fig. 3C) whereas they showed equilibration during 50–100 (Figs. 3D), 100–150 (Figs. 3E), 150–200 (Figs. 3F), 200–250 (Figs. 3G), 250–300 (Fig. 3H) ns simulation. Results showed that there is less fluctuation/deviation in the MT RMSDs compared to the WT COMT structure during the 30–40 (Figs. 3C), 100–150 (Figs. 3E), 150–200 (Figs. 3D), 200–250 (Figs. 3E), 250–300 (Fig. 3F) ns simulation. These results suggested that V158M can influence the stability of the backbone and C-alpha in the COMT protein (Fig. 3A–H).

Fig. 3.

RMSDs and Rg are shown for native and V158M mutant COMT. a) RMSD of backbone atoms during total 300 ns b) RMSD of Cα atoms during total 300 ns. RMSD of backbone atoms during c) 0–50 ns d) 50–100 ns e) 100–150 ns f) 150–200 ns g) 200–250 ns h) 250–300 ns molecular dynamic simulation i) Rg of backbone atoms during 300 ns molecular dynamic simulation.

The radius of gyration (Rg) is a measure to denote the mass-weighted RMSD of a cluster of atoms from their shared center of mass thereby suggesting the global dimension of the protein of interest. It represents the measure of compactness or density of the protein conformation during the course of simulations. To calculate the compactness of the native and mutant COMT protein structures during the simulation, we have calculated the Rg for the C-alpha residues. Results from the Rg value show a clear difference between the WT and MT structures during 300 ns simulation (Fig. 3I) averaging around 1.66 nm for WT and 1.63 nm for the MT. During the first 50 ns simulation, time both WT and MT showed fluctuations (Fig. S2a) followed by a steady-state during the 50–100 (Additional File 3: Fig. S2B), 100–150 (Additional File 3: Fig. S2C), 150–200 (Additional File 3: Fig. S2D), 200–250 (Additional File 3: Fig. S2E), 250–300 (Additional File 3: Fig. S2F) ns simulation. Overall, these results suggested that the V158M mutation affects the structural compactness of the protein and thus affects the folding of COMT protein (Fig. 3I).

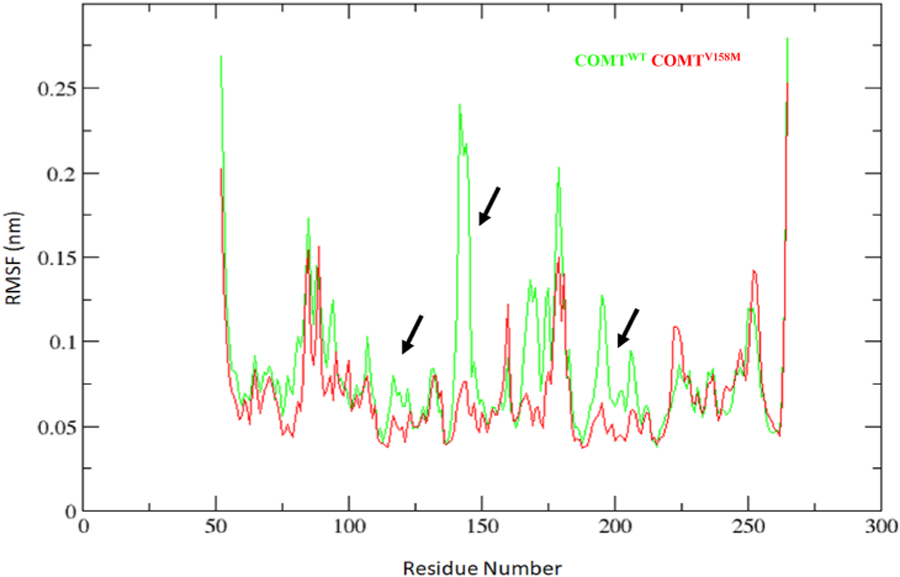

One of the novel criteria in MD simulations is to measure the amino acid residue fluctuation during the simulation as it can show the behaviour of the different residues in complexes on an average. Root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) is one such measure that fulfils this aspect by evaluating the internal fluctuation of one chain and compares it with the counter chain within the same complex. Results from RMSF analysis showed that the mutation influences the RMSF of the residues 100–150 (α5, α6, α7, β3, β4 strands) and 175–225 (α7, β6, β7 strands) (Fig. 4). To interpret the cohesiveness within the protein, the RMSF of WT was compared with the RMSF of MT COMT and a linear trend line was drawn to emphasize the divergence in these two proteins (Additional File 4: Fig. S3). Results showed a significant difference in the RMSF of the MT compared to the WT (Additional File 4: Fig. S3). Overall, our results suggested that the V158M mutation effects can have an influence on the conformation of α5, α6, α7 helices, β3, β4, β6, β7 strands and other residues of the COMT protein(Galzitskaya et al., 2008).

Fig. 4.

RMSF of the Cα atoms of native and mutant COMT vs. time. Native is shown in green; V158M mutant form of COMT is shown in red color. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

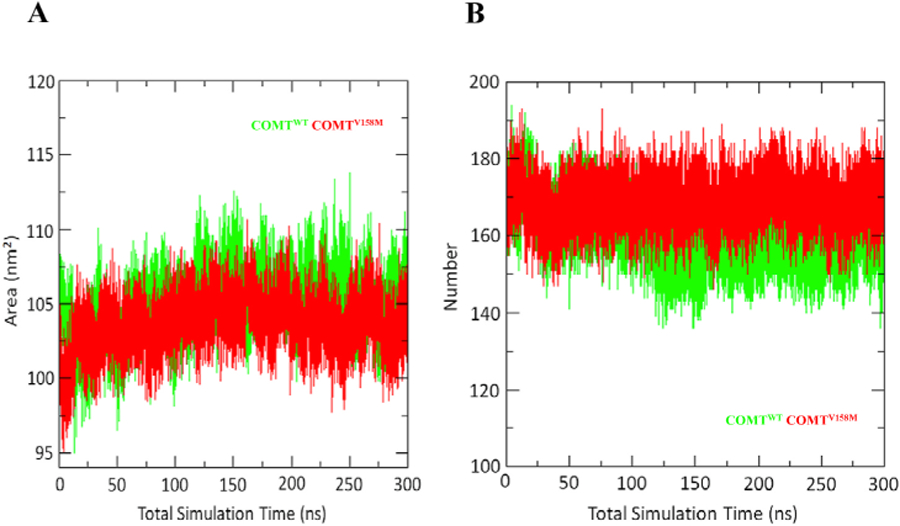

Solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) is nothing but an area calculated by the probe rolling on the surface of a protein(N et al., 2016). During MD simulations, SASA of the molecules is calculated by using a sphere of water molecules(Gerlt et al., 1997). Usually, it is key in maintaining stability of the protein and acts as a driving force for protein folding(Berhanu and Hansmann, 2012; Miller et al., 1987; Street and Mayo, 1998). Calculation of SASA is extremely useful in the energetic analysis of the biomolecules(Wei et al., 2017). We have calculated the SASA for both the WT and MT COMT proteins. Results from Fig. 5A, showed that the wild-type COMT has a higher SASA with an average of 105.07 nm2 compared to the mutant with an average of 103.65 nm2 during the 300 ns simulation. Overall, these results suggested that the V158M mutation induces a change in the surface of COMT protein due to amino acid residue change from accessible area to buried region. Calculating the non-covalent bonds such as van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonds, and electrostatic interactions are important in measuring the binding affinity between protein and ligand molecules. Among the non-covalent bonds, hydrogen bonds are the most significant and specific interactions in recognizing the biological processes(N et al., 2016). Fig. 5B depicts the number of protein-solvent intermolecular hydrogen bonds involved in WT and MT COMT proteins. Results from the calculation of number of protein-solvent intermolecular hydrogen bonds showed an on average higher amount of interactions in the MT compared to the WT (Fig. 5B). These results suggested that V158M mutation induces a change in the conformation of residues in alpha and beta helices which lead to an average higher number of protein-solvent intermolecular hydrogen bonds in COMT protein.

Fig. 5.

A) Solvent accessible surface area during total 300 ns B) Average number of protein-solvent intermolecular H-bonds during total 300 ns. Native is shown in green; V158M mutant form of COMT is shown in red color. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

The change in local reorientation of a protein backbone segment moving from one conformation to another can be analysed by measuring the internal rotational correlation functions (RCFs). It is a measure of average correlations of unit vector with its initial orientation after time in molecular frame of a protein being studied(Cote et al., 2010). We have calculated the RCF during the last 100 ns of trajectory utilizing the second order Legendre polynomial (P2) of NH bond vector (a) and a nonlinear curve fitted with two parameters in a model-free approach for both WT and MT COMT proteins. Results from RCF analysis showed a gradual decrease in the RCF throughout the first half, which can be assigned to fast internal motion for both WT and MT. However, in second half, WT demonstrated a rapid decrease in RCF, while during the remaining period, the MT showed a stabilized RCF (Fig. 6A). On an average, the C(t) rotational correlation time value was lower for the wild type compared to the mutant COMT protein (Fig. 6A). These results confirmed that V158M mutation induces a local reorientation of a segment of the backbone of COMT protein moving it from one conformation to another.

Fig. 6.

Rotational correlation function (RCF) of the NH bond vector and Principal component analysis of COMT. a) The RCF was calculated for the last 100 ns of the trajectory using the second order Legendre polynomial (P2) of the NH bond vector (a) and a nonlinear curve fitted with the two parameters in a model-free approach b) The eigenvalues plotted against the corresponding eigenvector indices obtained from the Cα covariance matrix constructed from the total MD trajectory c) Projection of the motion of the COMT WT and mutant in the phase space along the first two principal eigenvectors.

In general, principal component analysis is a method which filters out all the locally confined fluctuations and vibrational motions generated during the simulations. To determine confined fluctuation and structural motions of the WT and MT structures during the simulation, we have performed the Essential Dynamics (ED) analysis. Results from the ED analysis showing the eigenvalues plotted against equivalent eigenvector index for first 10 modes of motion at various trajectory lengths during the simulations for WT and MT COMT protein is shown in Fig. 6B. Results showed only a less number of eigenvectors with significant eigenvalues for both WT and MT COMT during the simulation time indicating that most of the internal motions were confined to a little dimension in the crucial subspace (Fig. 6B). Spectrum of eigenvalues in Fig. 6B showed some major fluctuations that were confined to first two eigenvectors. Therefore, we have plotted the projection of trajectories in WT and MT COMT protein during the simulation in phase space along first two principal components PC1 and PC2 at 300 K in Fig. 6C. Results from the projection of the trajectories on the plane defined by the first and second eigenvectors (Fig. 6C) indicates that the WT has a wider conformational basin than the MT COMT protein. These results suggest that V158M mutation induces decrease in flexibility in the collective motion of the COMT protein.

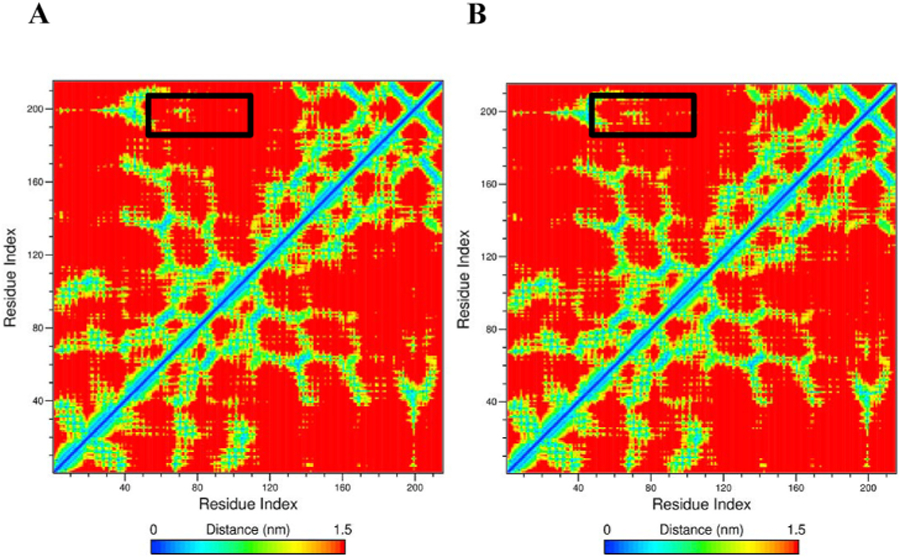

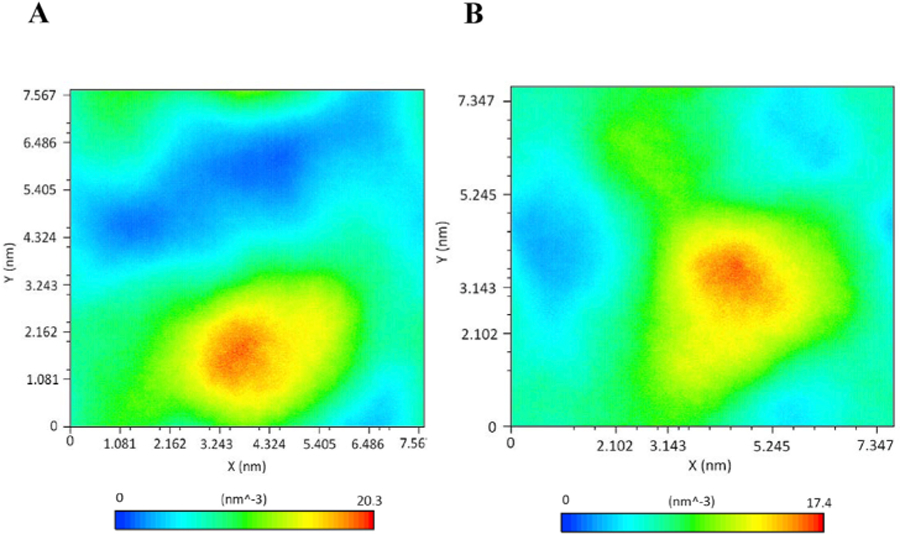

Further, to investigate and analyse the effect of V158M mutations on extent of correlation motions, we calculated the cross-correlation matrices of Cα atom fluctuations for WT and MT COMT proteins during the simulation time and plotted in Fig. 7A and B. Regions that are highly positive and associated with strong correlated motions for specific residues were shown in red and yellow color whereas low regions that are indicative for strong anticorrelation in the specific residue movements were shown in blue color (Fig. 7A and B). Results show that on an average, comparing with WT, MT had a decrease in the extent of correlated and anticorrelated motions in the residues (Fig. 7A and B). Our results showed major differences between the WT and the MT around the residue indices 40 to 120. This result suggests that the V158M mutation influence the conformation of nearby residues in the COMT protein. Further, one of the observations that can be derived from MD trajectories is density functions such as mass or number densities. The profiles derived from the density can be connected to the experimental observables (Nagle and Wiener, 1989). g_densmap command in GROMACS is one such parameter which computes the 2D number-density maps and creates planar and axial-radial density maps. We have calculated the density distribution of atoms using g_densmap and plotted in Fig. 8 to examine if the V158M mutation has triggered any major alterations in the orientation and distribution of atoms. Results showed that distribution of all atoms in the V158M significantly diverged from WT COMT protein (Fig. 8A and B) suggesting that V158M mutation induces a deleterious effect on the COMT protein. Overall, there was a major change in the atom density observed in the MT compared to the WT COMT protein (Fig. 8A and B).

Fig. 7.

Contact map for residues in WT and mutant COMT. Distance matrices consisting of the smallest distance between residue pairs and the number of different atomic contacts between residues over the whole trajectory for a) wild type COMT and b) V158M mutant COMT.

Fig. 8.

Number density plot of COMT during 300 ns MD Simulations. a) wild type COMT and b) V158M mutant COMT.

4. Discussion

The Human Genome Project lead to a path allowing the identification of SNPs that modify amino acid sequence and protein function. Numerous SNPs are now excellent biomarkers for allelic based studies targeting the variance in the outcome or prevalence of several neurological disorders(Dardiotis et al., 2010; Davidson et al., 2015; Diaz-Arrastia and Baxter, 2006). To predict the SNPs in the genes conferring risk to PTSD, we performed literature search in the bibliographic public domain database/search engines. Our results from literature search from previous studies on SNPs in genes such as COMT, FAAH, NLGN1, IL2RA, ANKRD55, AChE, SKA2, FKBP5, HTR1A, DICER1, CCK, ALOX12, DRD2, SKA2, CHRNA5, SLC6A2, CRP, SLC1A1, ADRB2, DRD3, PRKCA, SLC18A2, CRHR-2, BDNF, CRHR1, ADCYAP1R1 and RGS2 showed risk towards PTSD (Table 1). Among these genes shown in Table 1, we selected COMT for our study.

The Val158Met SNP is a common functional variant of COMT. While the valine variant metabolizes dopamine at a four-fold higher rate than that of methionine, the latter is highly expressed in the brain, thereby leading to a significant decrease in functional enzyme activity(Schacht, 2016). Thus, this low rate of catabolism by the methionine allele results in increased expression of dopamine in the synapses in the prefrontal cortex(Schacht, 2016). It has been well established that the polymorphism leading to Val158Met mutation affects dopamine signalling and thereby cognition and emotional processes, including schizophrenia and depression(Schacht, 2016) which are comorbidity factors in PTSD. In addition, because of the decrease in enzymatic activity in Val158Met variant, there is increased accumulation of carcinogenic endogenous catechol estrogens which may increase risk of carcinogenesis(Sak, 2017).

COMT is also known to play a role in the immune system. Previous reports showed that genetic polymorphisms regulating RBC COMT activity may also regulate the level of human lymphocyte COMT activity (Sladek-Chelgren and Weinshilboum, 1981). It is known that estrogens disrupt the growth and control of the immune system by decreasing the variation of T and B cells as well as T-cell dependent inflammation. Among the estrogens, the most potent estrogen, 17β-estradiol (E2) conversion into 2-methoxyestradiol (2-ME) via 2-hydroxyestradiol requires the enzyme COMT(Stubelius et al., 2012). 2-ME has been previously demonstrated to facilitate anti-inflammatory properties(Kanasaki et al., 2017). A previous study showed that homozygous deletion of COMT (COMT‒/‒) leads to the development of preeclampsia, a condition that includes inflammation(Kanasaki et al., 2008). It is known to have a role in regulating and maintaining the immune system(Stubelius et al., 2012). Because we have previously shown that in PTSD, there is enhanced inflammation(Bam et al., 2016a, 2016b, 2017; Chitrala et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2014), combined with the fact that COMT is a key enzyme in regulating the immune system and having a biological role in several neurological disorders, we selected this gene for our analysis.

A previous report showed that genetic variations in COMT are known to affect the mRNA, protein, and enzyme activity in postmortem human brain(Chen et al., 2004). Therefore, initially we analysed the deleterious single nucleotide polymorphisms in conferring risk to PTSD. We searched the human variants in COMT using dbSNP database. Results from our dbSNP database search showed a higher percentage of SNPs in intronic (40.59%) followed by 3′ UTR (7.45%), 5′ UTR (4.32%), missense (3.79%), coding synonymous (2.04%), frame shift (0.36%), nonsense (0.23%), stop gained (0.23%) and 3′ splice site (0.05%) in human COMT gene (Fig. 1). Among the SNPs, missense SNPs play a key role in several neurological disorders based on Genome Wide Association Studies(Pal and Moult, 2015). Therefore, we selected missense SNPs for our study. To predict the deleterious nature of missense SNPs, we used SIFT and Polyphen-2 servers. Results showed that five SNPs (rs4680, rs6267, rs4986871, rs13306279, rs13306281) predicted as deleterious by both SIFT (Table 1) and Polyphen-2 (Table 2) servers.

Among the predicted deleterious SNPs by both SIFT and Polyphen-2, SNP rs4680 a common coding SNP with Val158Met(Chen et al., 2004) allele is reported to be related with PTSD and functional consequence following mild traumatic brain injury in Caucasian subjects(Winkler et al., 2016). Therefore, we selected Val158Met mutation induced by this SNP for our study. To examine the impact of V158M on the COMT protein structure, we used the crystal structure of human COMT from PDB (PDB ID: 3BWM) (Fig. 2A) (Rutherford et al., 2008) which is comprised of a seven-stranded β-sheet core (3↑2↑1↑4↑5↑7↓6↑) sandwiched between two sets of α-helices. To elucidate the impact of this V158M on the COMT protein, we replaced Val at 158th position with Met and subjected to MD simulations (Fig. 2B). In the present study, we are interested in studying the impact of V158M mutation on the COMT protein and we are not interested in elucidating the enzyme activity of the COMT. Therefore, we have removed all the ligands and the crystal water molecules from the protein before it was subjected to simulations.

To check the impact of V158M on the stability of COMT protein, we analysed the RMSD of backbone (Fig. 3A, C-H), C-alpha atoms (Fig. 3B) and Rg of backbone atoms (Fig. 3H) in both WT and MT COMT proteins during 300 ns simulations. Results showed that V158M induces the stability of backbone and C-alpha, structural compactness thereby affecting the fold of COMT protein. To check the impact of V158M on the secondary structure and solvent accessibility, we calculated RMSF (Fig. 4), SASA (Fig. 5A) and protein-solvent intermolecular hydrogen bonds (Fig. 5B). Results showed that V158M influences the conformation secondary structure elements α5, α6, α7 helices, β3, β4, β6, β7 strands, orientational change in the protein surface and the amount of intermolecular hydrogen bonds in COMT protein.

To check the impact of V158M on the local reorientation in conformation, structural motion, extent of correlation motion and atomic distribution of COMT protein, we analysed the RCFs (Fig. 6A), ED (Fig. 6B), first two principal components PC1 and PC2 at a temperature 300 K (Fig. 6C), cross-correlation matrices of the Cα atom fluctuations (Fig. 7A and B) and number density plot (Fig. 8A and B) in both WT and MT COMT proteins during 300 ns simulations. Results showed that V158M induces a local reorientation, decrease in flexibility in the collective motion, conformation of nearby residues and atom density distribution in the COMT protein.

In general, the accuracy of any molecular simulations depends upon mainly the availability of experimental structure or having a good homology model for an initial condition. Overall, the simulation studies design is heavily influenced by the availability of experimental structures (Hollingsworth and Dror, 2018). The main strength of our study is that all the MD simulations performed in the study were designed based on the experimentally derived X-ray diffraction crystal structure of human Catechol O-Methyltransferase (PDB ID: 3BWM). Further, only few studies have been proposed on the COMT role in PTSD and our study is the first and foremost to study the impact of V158M on COMT protein using MD simulations. The results presented in our study is based on the COMT experimental structure available in humans and we will overcome these limitations by extending these studies to other species in future.

5. Conclusions

Although several studies have been reported on many variations that have been identified in the COMT gene, the potential structural and functional impact of many of them have not been analysed yet. Among the SNPs, COMT gene Val158Met mutations play a predominant role in several human disorders. The results reported in this study elucidate the role of deleterious mutations in COMT which may provide useful information for the design of COMT mutant-based therapeutic strategies against PTSD. Further, the results from our study provide a framework for future studies to analyse how this Val158Met mutation impacts on COMT inhibitors such as entacapone and tolcapone which are used in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. In conclusion, data shown here enhance further, the understanding of COMT activity and forms a beginning point for the studying the impact of variations on the COMT gene. Further, functional analyses are essential to elucidate the biological mechanisms of impact of Val158Met mutation on the COMT protein.

Supplementary Material

Funding source

The funders had no role in collection of the data, designing the study, analysis and interpretation of the data, or writing the report details.

Funding

The present study was supported in part by NIH grant R01AI129788, TUFCCC/HC Regional Comprehensive Cancer Health Disparity Partnership, Award Number U54 CA221704(5) from the National Cancer Institute of National Institutes of Health (NCI/NIH).

Footnotes

Availability of data and materials

The simulation data generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.03.048.

References

- Adzhubei I, Jordan DM, Sunyaev SR, 2013. Predicting functional effect of human missense mutations using PolyPhen-2. Curr. Protocols Human Genetics Chap 7. Unit 7 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amberger J, Bocchini CA, Scott AF, Hamosh A, 2009. McKusick’s online mendelian inheritance in man (OMIM). Nucleic Acids Res 37, D793–D796. Database issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amstadter AB, Koenen KC, Ruggiero KJ, Acierno R, Galea S, Kilpatrick DG, Gelernter J, 2009. Variant in RGS2 moderates posttraumatic stress symptoms following potentially traumatic event exposure. J. Anxiety Disord 23 (3), 369–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amstadter AB, Nugent NR, Yang BZ, Miller A, Siburian R, Moorjani P, Haddad S, Basu A, Fagerness J, Saxe G, Smoller JW, Koenen KC, 2011. Corticotrophin-releasing hormone type 1 receptor gene (CRHR1) variants predict posttraumatic stress disorder onset and course in pediatric injury patients. Dis. Markers 30 (2–3), 89–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badour CL, Hirsch RL, Zhang J, Mandel H, Hamner M, Wang Z, 2015. Exploring the association between a cholecystokinin promoter polymorphism (rs1799923) and posttraumatic stress disorder in combat veterans. J. Anxiety Disord 36, 78–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bam M, Yang X, Zhou J, Ginsberg JP, Leyden Q, Nagarkatti PS, Nagarkatti M, 2016a. Evidence for epigenetic regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, interleukin-12 and interferon gamma, in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from PTSD patients. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. : Off. J. Soc. NeuroImmune Pharmacol 11 (1), 168–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bam M, Yang X, Zumbrun EE, Zhong Y, Zhou J, Ginsberg JP, Leyden Q, Zhang J, Nagarkatti PS, Nagarkatti M, 2016b. Dysregulated immune system networks in war veterans with PTSD is an outcome of altered miRNA expression and DNA methylation. Sci. Rep 6, 31209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bam M, Yang X, Zumbrun EE, Ginsberg JP, Leyden Q, Zhang J, Nagarkatti PS, Nagarkatti M, 2017. Decreased AGO2 and DCR1 in PBMCs from War Veterans with PTSD leads to diminished miRNA resulting in elevated inflammation. Transl. Psychiatry 7 (8), e1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berhanu WM, Hansmann UH, 2012. Side-chain hydrophobicity and the stability of Abeta(1)(6)(−)(2)(2) aggregates. Protein Sci. : Publ. Protein Soc 21 (12), 1837–1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Chen ZJ, Jiang HD, Chen JZ, 2014. Computational studies of the regioselectivities of COMT-catalyzed meta-/para-O methylations of luteolin and quercetin. J. Phys. Chem. B 118 (2), 470–481.s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Vale I, van Rossum EF, Machado JC, Mota-Cardoso R, Carvalho D, 2016. Genetics of glucocorticoid regulation and posttraumatic stress disorder–What do we know? Neurosci. BioBehav. Rev 63, 143–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Lipska BK, Halim N, Ma QD, Matsumoto M, Melhem S, Kolachana BS, Hyde TM, Herman MM, Apud J, Egan MF, Kleinman JE, Weinberger DR, 2004. Functional analysis of genetic variation in catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT): effects on mRNA, protein, and enzyme activity in postmortem human brain. Am. J. Hum. Genet 75 (5), 807–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitrala KN, Nagarkatti P, Nagarkatti M, 2016. Prediction of possible biomarkers and novel pathways conferring risk to post-traumatic stress disorder. PloS One 11 (12), e0168404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote Y, Senet P, Delarue P, Maisuradze GG, Scheraga HA, 2010. Nonexponential decay of internal rotational correlation functions of native proteins and self-similar structural fluctuations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 107 (46), 19844–19849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dardiotis E, Fountas KN, Dardioti M, Xiromerisiou G, Kapsalaki E, Tasiou A, Hadjigeorgiou GM, 2010. Genetic association studies in patients with traumatic brain injury. Neurosurg. Focus 28 (1), E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson J, Cusimano MD, Bendena WG, 2015. Post-traumatic brain injury: genetic susceptibility to outcome. Neuroscientist : Rev. J. Bringing Neurobiol. Neurol. Psychiatr 21 (4), 424–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deslauriers J, Acheson DT, Maihofer AX, Nievergelt CM, Baker DG, Geyer MA, Risbrough VB, Marine Resiliency Study T, 2018. COMT val158met polymorphism links to altered fear conditioning and extinction are modulated by PTSD and childhood trauma. Depress. Anxiety 35 (1), 32–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Arrastia R, Baxter VK, 2006. Genetic factors in outcome after traumatic brain injury: what the human genome project can teach us about brain trauma. J. Head Trauma Rehabil 21 (4), 361–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson ZR, le Francois B, Santos TL, Almli LM, Boldrini M, Champagne FA, Arango V, Mann JJ, Stockmeier CA, Galfalvy H, Albert PR, Ressler KJ, Hen R, 2016. The functional serotonin 1a receptor promoter polymorphism, rs6295, is associated with psychiatric illness and differences in transcription. Transl. Psychiatry 6, e746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Z, He M, Zhang J, Chen K, Li B, Wang J, 2015. Assessment of functional tag single nucleotide polymorphisms within the DRD2 gene as risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder in the Han Chinese population. J. Affect. Disord 188, 210–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Solh AA, Riaz U, Roberts J, 2018. Sleep Disorders in Patients with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Chest [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fani N, King TZ, Shin J, Srivastava A, Brewster RC, Jovanovic T, Bradley B, Ressler KJ, 2016. Structural and functional connectivity in posttraumatic stress disorder: associations with Fkbp5. Depress. Anxiety 33 (4), 300–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galzitskaya OV, Bogatyreva NS, Ivankov DN, 2008. Compactness determines protein folding type. J. Bioinf. Comput. Biol 6 (4), 667–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasparyan AY, Ayvazyan L, Kitas GD, 2013. Multidisciplinary bibliographic databases. J. Kor. Med. Sci 28 (9), 1270–1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genomes Project C, Abecasis GR, Auton A, Brooks LD, DePristo MA, Durbin RM, Handsaker RE, Kang HM, Marth GT, McVean GA, 2012. An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature 491 (7422), 56–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlt JA, Kreevoy MM, Cleland W, Frey PA, 1997. Understanding enzymic catalysis: the importance of short, strong hydrogen bonds. Chem. Biol 4 (4), 259–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindasamy H, Magudeeswaran S, Poomani K, 2019. Identification of novel flavonoid inhibitor of Catechol-O-Methyltransferase enzyme by molecular screening, quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics and molecular dynamics simulations. J. Biomol. Struct. Dynam 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gupta MK, Gouda G, Donde R, Vadde R, Behera L, 2020. In silico characterization of the impact of mutation (LEU112PRO) on the structure and function of carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 8 in Oryza sativa. Phytochemistry 175, 112365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes JP, Logue MW, Reagan A, Salat D, Wolf EJ, Sadeh N, Spielberg JM, Sperbeck E, Hayes SM, McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP, Verfaellie M, Stone A, Schichman SA, Miller MW, 2017. COMT Val158Met polymorphism moderates the association between PTSD symptom severity and hippocampal volume. J. Psychiatr. Neurosci. : J. Psychiatr. Neurosci 42 (2), 95–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess B, Bekker H, Berendsen HJC, Fraaije JGEM, 1997. LINCS: a linear constraint solver for molecular simulations 1 18 (12), 1463–1472. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingsworth SA, Dror RO, 2018. Molecular dynamics simulation for all. Neuron 99 (6), 1129–1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Ng PC, 2012. Predicting the effects of frameshifting indels. Genome Biol 13 (2), R9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junaid M, Li CD, Li J, Khan A, Ali SS, Jamal SB, Saud S, Ali A, Wei DQ, 2020. Structural insights of catalytic mechanism in mutant pyrazinamidase of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Biomol. Struct. Dynam 1–23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kanaan N, Ruiz Pernia JJ, Williams IH, 2008. QM/MM simulations for methyl transfer in solution and catalysed by COMT: ensemble-averaging of kinetic isotope effects. Chem. Commun (46), 6114–6116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanasaki K, Palmsten K, Sugimoto H, Ahmad S, Hamano Y, Xie L, Parry S, Augustin HG, Gattone VH, Folkman J, Strauss JF, Kalluri R, 2008. Deficiency in catechol-O-methyltransferase and 2-methoxyoestradiol is associated with preeclampsia. Nature 453 (7198), 1117–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanasaki M, Srivastava SP, Yang F, Xu L, Kudoh S, Kitada M, Ueki N, Kim H, Li J, Takeda S, Kanasaki K, Koya D, 2017. Deficiency in catechol-o-methyltransferase is linked to a disruption of glucose homeostasis in mice. Sci. Rep 7 (1), 7927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB, 1995. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the national comorbidity Survey. Arch. Gen. Psychiatr 52 (12), 1048–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilaru V, Iyer SV, Almli LM, Stevens JS, Lori A, Jovanovic T, Ely TD, Bradley B, Binder EB, Koen N, Stein DJ, Conneely KN, Wingo AP, Smith AK, Ressler KJ, 2016. Genome-wide gene-based analysis suggests an association between Neuroligin 1 (NLGN1) and post-traumatic stress disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 6, e820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimbrel NA, Garrett ME, Dennis MF, Liu Y, Patanam I, Workgroup VM, Ashley-Koch AE, Hauser MA, Beckham JC, 2015. Effect of genetic variation in the nicotinic receptor genes on risk for posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry Res 229 (1–2), 326–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Hamilton KJ, Perera L, Wang T, Gruzdev A, Jefferson TB, Zhang AX, Mathura E, Gerrish KE, Wharey L, Martin NP, Li JL, Korach KS, 2020. ESR1 mutations associated with EIS change conformation of ligand receptor complex and alter transcriptome profile. Endocrinology 161 (6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberzon I, King AP, Ressler KJ, Almli LM, Zhang P, Ma ST, Cohen GH, Tamburrino MB, Calabrese JR, Galea S, 2014. Interaction of the ADRB2 gene polymorphism with childhood trauma in predicting adult symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder. JAMA Psychiatr 71 (10), 1174–1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin LY, Sidani JE, Shensa A, Radovic A, Miller E, Colditz JB, Hoffman BL, Giles LM, Primack BA, 2016. Association between Social Media Use and Depression among U.S. Young Adults. Depress. Anxiety 33 (4), 323–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Rimmler J, Dennis MF, Ashley-Koch AE, Hauser MA, Mid-Atlantic Mental Illness Research, E., Clinical Center, W., Beckham JC, 2013. Association of Variant rs4790904 in Protein Kinase C Alpha with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in a U.S. Caucasian and African-American Veteran Sample. J. Depress. Anxiety 2 (1), S4001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Z, Liu H, Wu B, 2014. Structure-based drug design of catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibitors for CNS disorders. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol 77 (3), 410–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magarkar A, Parkkila P, Viitala T, Lajunen T, Mobarak E, Licari G, Cramariuc O, Vauthey E, Rog T, Bunker A, 2018. Membrane bound COMT isoform is an interfacial enzyme: general mechanism and new drug design paradigm. Chem. Commun 54 (28), 3440–3443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michopoulos V, Rothbaum AO, Jovanovic T, Almli LM, Bradley B, Rothbaum BO, Gillespie CF, Ressler KJ, 2015. Association of CRP genetic variation and CRP level with elevated PTSD symptoms and physiological responses in a civilian population with high levels of trauma. Am. J. Psychiatr 172 (4), 353–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S, Lesk AM, Janin J, Chothia C, 1987. The accessible surface area and stability of oligomeric proteins. Nature 328 (6133), 834–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW, Wolf EJ, Sadeh N, Logue M, Spielberg JM, Hayes JP, Sperbeck E, Schichman SA, Stone A, Carter WC, Humphries DE, Milberg W, McGlinchey R, 2015. A novel locus in the oxidative stress-related gene ALOX12 moderates the association between PTSD and thickness of the prefrontal cortex. Psychoneuroendocrinology 62, 359–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murzyn K, Bratek M, Pasenkiewicz-Gierula M, 2013. Refined OPLS all-atom force field parameters for n-pentadecane, methyl acetate, and dimethyl phosphate. J. Phys. Chem. B 117 (51), 16388–16396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- N N, C GP, Chakraborty C, V K, D TK, V B, R S, Lu A, Ge Z, Zhu H, 2016. Mechanism of artemisinin resistance for malaria PfATP6 L263 mutations and discovering potential antimalarials: an integrated computational approach. Sci. Rep 6, 30106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagle JF, Wiener MC, 1989. Relations for lipid bilayers. Connection of electron density profiles to other structural quantities. Biophys. J 55 (2), 309–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng PC, Henikoff S, 2001. Predicting deleterious amino acid substitutions. Genome Res 11 (5), 863–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng PC, Henikoff S, 2003. SIFT: predicting amino acid changes that affect protein function. Nucleic Acids Res 31 (13), 3812–3814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nissinen E, Mannisto PT, 2010. Biochemistry and pharmacology of catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibitors. Int. Rev. Neurobiol 95, 73–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlowski A, St-Pierre JF, Magarkar A, Bunker A, Pasenkiewicz-Gierula M, Vattulainen I, Rog T, 2011. Properties of the membrane binding component of catechol-O-methyltransferase revealed by atomistic molecular dynamics simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 115 (46), 13541–13550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal LR, Moult J, 2015. Genetic basis of common human disease: insight into the role of missense SNPs from genome-wide association studies. J. Mol. Biol 427 (13), 2271–2289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel CN, Georrge JJ, Modi KM, Narechania MB, Patel DP, Gonzalez FJ, Pandya HA, 2018. Pharmacophore-based virtual screening of catechol-o-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibitors to combat Alzheimer’s disease. J. Biomol. Struct. Dynam 36 (15), 3938–3957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patra N, Ioannidis EI, Kulik HJ, 2016. Computational investigation of the interplay of substrate positioning and reactivity in catechol O-methyltransferase. PloS One 11 (8), e0161868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak RH, Sumner JA, Aiello AE, Uddin M, Neumeister A, Guffanti G, Koenen KC, 2015. Association of the rs2242446 polymorphism in the norepinephrine transporter gene SLC6A2 and anxious arousal symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 76 (4), e537–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers A, Almli L, Smith A, Lori A, Leveille J, Ressler KJ, Jovanovic T, Bradley B, 2016. A genome-wide association study of emotion dysregulation: Evidence for interleukin 2 receptor alpha. J. Psychiatr. Res 83, 195–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakofsky JJ, Ressler KJ, Dunlop BW, 2012. BDNF function as a potential mediator of bipolar disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder comorbidity. Mol. Psychiatr 17 (1), 22–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ressler KJ, Mercer KB, Bradley B, Jovanovic T, Mahan A, Kerley K, Norrholm SD, Kilaru V, Smith AK, Myers AJ, Ramirez M, Engel A, Hammack SE, Toufexis D, Braas KM, Binder EB, May V, 2011. Post-traumatic stress disorder is associated with PACAP and the PAC1 receptor. Nature 470 (7335), 492–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford K, Daggett V, 2009. A hotspot of inactivation: the A22S and V108M polymorphisms individually destabilize the active site structure of catechol O-methyltransferase. Biochemistry 48 (27), 6450–6460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford K, Le Trong I, Stenkamp RE, Parson WW, 2008. Crystal structures of human 108V and 108M catechol O-methyltransferase. J. Mol. Biol 380 (1), 120–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh N, Wolf EJ, Logue MW, Hayes JP, Stone A, Griffin LM, Schichman SA, Miller MW, 2016. Epigenetic variation at Ska2 predicts suicide phenotypes and internalizing psychopathology. Depress. Anxiety 33 (4), 308–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sak K, 2017. The Val158Met polymorphism in COMT gene and cancer risk: role of endogenous and exogenous catechols. Drug Metab. Rev 49 (1), 56–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schacht JP, 2016. COMT val158met moderation of dopaminergic drug effects on cognitive function: a critical review. Pharmacogenomics J 16 (5), 430–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuer S, Ising M, Uhr M, Otto Y, von Klitzing K, Klein AM, 2016. FKBP5 polymorphisms moderate the influence of adverse life events on the risk of anxiety and depressive disorders in preschool children. J. Psychiatr. Res 72, 30–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherry ST, Ward MH, Kholodov M, Baker J, Phan L, Smigielski EM, Sirotkin K, 2001. dbSNP: the NCBI database of genetic variation. Nucleic Acids Res 29 (1), 308–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim NL, Kumar P, Hu J, Henikoff S, Schneider G, Ng PC, 2012. SIFT web server: predicting effects of amino acid substitutions on proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 40, W452–W457. Web Server issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sladek-Chelgren S, Weinshilboum RM, 1981. Catechol-o-methyltransferase biochemical genetics: human lymphocyte enzyme. Biochem. Genet 19 (11–12), 1037–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solovieff N, Roberts AL, Ratanatharathorn A, Haloosim M, De Vivo I, King AP, Liberzon I, Aiello A, Uddin M, Wildman DE, Galea S, Smoller JW, Purcell SM, Koenen KC, 2014. Genetic association analysis of 300 genes identifies a risk haplotype in SLC18A2 for post-traumatic stress disorder in two independent samples. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology 39 (8), 1872–1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spagnolo PA, Ramchandani VA, Schwandt ML, Kwako LE, George DT, Mayo LM, Hillard CJ, Heilig M, 2016. FAAH gene variation moderates stress response and symptom severity in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder and comorbid alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 40 (11), 2426–2434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MM, Hrusch CL, Gozdz J, Igartua C, Pivniouk V, Murray SE, Ledford JG, Marques Dos Santos M, Anderson RL, Metwali N, Neilson JW, Maier RM, Gilbert JA, Holbreich M, Thorne PS, Martinez FD, von Mutius E, Vercelli D, Ober C, Sperling AI, 2016. Innate immunity and Asthma risk in Amish and Hutterite Farm Children. N. Engl. J. Med 375 (5), 411–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Street AG, Mayo SL, 1998. Pairwise calculation of protein solvent-accessible surface areas. Folding Des 3 (4), 253–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubelius A, Wilhelmson AS, Gogos JA, Tivesten A, Islander U, Carlsten H, 2012. Sexual dimorphisms in the immune system of catechol-O-methyltransferase knockout mice. Immunobiology 217 (8), 751–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai CH, Wu RM, 2002. Catechol-O-methyltransferase and Parkinson’s disease. Acta Med. Okayama 56 (1), 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Spoel D, Lindahl E, Hess B, Groenhof G, Mark AE, Berendsen HJ, 2005. GROMACS: fast, flexible, and free. J. Comput. Chem 26 (16), 1701–1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei S, Brooks CL 3rd, Frank AT, 2017. A rapid solvent accessible surface area estimator for coarse grained molecular simulations. J. Comput. Chem 38 (15), 1270–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingo AP, Almli LM, Stevens JS, Klengel T, Uddin M, Li Y, Bustamante AC, Lori A, Koen N, Stein DJ, Smith AK, Aiello AE, Koenen KC, Wildman DE, Galea S, Bradley B, Binder EB, Jin P, Gibson G, Ressler KJ, 2015. DICER1 and microRNA regulation in post-traumatic stress disorder with comorbid depression. Nat. Commun 6, 10106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler EA, Yue JK, Ferguson AR, Temkin NR, Stein MB, Barber J, Yuh EL, Sharma S, Satris GG, McAllister TW, Rosand J, Sorani MD, Lingsma HF, Tarapore PE, Burchard EG, Hu D, Eng C, Wang KK, Mukherjee P, Okonkwo DO, Diaz-Arrastia R, Manley GT, Investigators T-T, 2016. COMT Val(158)Met polymorphism is associated with post-traumatic stress disorder and functional outcome following mild traumatic brain injury. J. Clin. Neurosci. : Off. J. Neurosurg. Soc. Australasia 35, 109–116.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte AV, Floel A, 2012. Effects of COMT polymorphisms on brain function and behavior in health and disease. Brain Res. Bull 88 (5), 418–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf EJ, Harrington KM, Clark SL, Miller MW, 2013. Sample Size Requirements for Structural Equation Models: An Evaluation of Power, Bias, and Solution Propriety. Educ. Psychol. Meas 76 (6), 913–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf EJ, Mitchell KS, Logue MW, Baldwin CT, Reardon AF, Aiello A, Galea S, Koenen KC, Uddin M, Wildman D, Miller MW, 2014. The dopamine D3 receptor gene and posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Trauma Stress 27 (4), 379–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Odwin-Dacosta S, Cao S, Yager JD, Tang WY, 2019. Estrogen down regulates COMT transcription via promoter DNA methylation in human breast cancer cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 367, 12–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xuan W, Wang P, Watson SJ, Meng F, 2007. Medline search engine for finding genetic markers with biological significance. Bioinformatics 23 (18), 2477–2484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Mehmood R, Wang M, Qi HW, Steeves AH, Kulik HJ, 2019. Revealing quantum mechanical effects in enzyme catalysis with large-scale electronic structure simulation. Reaction chem. Eng 4 (2), 298–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Sheerin C, Mandel H, Banducci AN, Myrick H, Acierno R, Amstadter AB, Wang Z, 2014. Variation in SLC1A1 is related to combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Anxiety Disord 28 (8), 902–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Nagarkatti P, Zhong Y, Ginsberg JP, Singh NP, Zhang J, Nagarkatti M, 2014. Dysregulation in microRNA expression is associated with alterations in immune functions in combat veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. PloS One 9 (4), e94075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.