Abstract

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is an established part of the treatment algorithm for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-related acute respiratory distress syndrome. An intense inflammatory response may cause an imbalance in the coagulation cascade making both thrombosis and bleeding common and notable features of the clinical management of these patients. Large observational and retrospective studies provide a better understanding of the pathophysiology and management of bleeding and thrombosis in COVID-19 patients requiring ECMO. Clinically significant bleeding, including intracerebral hemorrhage, is an independent predictor of mortality, and thrombosis (particularly pulmonary embolism) is associated with mortality, especially if occurring with right ventricular dysfunction. The incidence of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia is higher than the general patient cohort with acute respiratory distress syndrome or other indications for ECMO. The use of laboratory parameters to predict bleeding or thrombosis has a limited role. In this review, the authors discuss the complex pathophysiology of bleeding and thrombosis observed in patients with COVID-19 during ECMO support, and their effects on outcomes.

Keywords: COVID-19, ARDS, ECMO, Bleeding, Thrombosis

THE INFLAMMATORY STATE ASSOCIATED WITH COVID-19 may amplify the proinflammatory effect of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO).1, 2, 3 The clinical consequences of this are bleeding, along with other disorders of coagulation, including thrombosis. Coagulation function and assessment is complicated additionally by patients receiving anticoagulation to ensure circuit patency. ECMO has become an established part of the treatment algorithm for the acute respiratory distress syndrome,4 , 5 including patients with COVID-19. In contrast to COVID-19 patients not receiving ECMO, bleeding is more prevalent in ECMO patients.2 , 6 Recent studies investigating the role of therapeutic anticoagulation in patients not receiving ECMO with severe COVID-19 pneumonitis have demonstrated an increase in bleeding complications.7 In this review the authors aim to present and discuss the most recent studies on this subject and assess the impact of bleeding and thrombosis on outcomes, including mortality.

Search strategy

The authors searched MEDLINE (Medline Industries, LP.) and EMBASE (Elsevier) from the commencement date through to the beginning of January 2022, for the following search terms (in the title or abstract): “ECMO,” “extracorporeal membrane oxygenation,” “COVID-19,” “coronavirus disease 2019,” “COVID-19 coagulopathy,” “thrombosis,” “hemorrhage,” and “coagulopathy,” in isolation and in combination without restrictions. A mixture of free text and subject headings mapped to the thesaurus to ensure a thorough search of the selected databases were used. In addition, the authors searched for bibliographic references of relevant articles in order to identify relevant studies to be included in this narrative review.

Pathophysiology

COVID-19 is a multisystem disorder with a prominent respiratory component. The commonest route of infection by SARS-CoV-2 is via the respiratory tract with entry into pneumocytes via the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) angiotensin coneting enzyme 2 receptors.8 ACE 2 receptors also are found in the gastrointestinal system, heart, and kidney; hence the pathologic effects of infection are common in these sites as well. 3 Endocytosis of the virus receptor complex results in widespread endotheliopathy and pulmonary vascular microthrombosis.2 , 6 , 9 Clinically, in combination with COVID-19–related pneumonia, this may result in hypoxemia potentially requiring supplemental oxygen, noninvasive forms of mechanical ventilation, invasive mechanical ventilation, or ECMO support.

ECMO support is associated with a biomaterial-induced inflammatory response associated with the activation of coagulative and inflammatory cascades.10 The levels of proinflammatory cytokines rise rapidly with resultant leukocyte activation, which in severe forms may result in endothelial injury and micro-circulation disruption. 10

The overarching coagulation state in patients receiving ECMO support is initially prothrombotic and this state tends to predominate for the time spent on ECMO support, hence the need for continuous anticoagulation in most cases. There have been reports where the entire ECMO journey has been carried out without the need for anticoagulation.11 , 12 Anticoagulant processes such as the effect of acquired von Willebrand disease, loss of platelet glycoprotein IIc and IIIb receptors, fibrinolysis, and oxygenator sequestration of micro-thrombi may contribute to bleeding. In most instances, the predominant state remains prothrombotic.13 A contrasting clinical picture, where bleeding tendency features as the predominant coagulation state may be encountered in intense inflammatory states (eg, COVID-19 or severe bacterial sepsis). As a result, an increased incidence of clinically significant bleeding occurred in these states.9 , 14

Hemorrhage

The earliest reports from Wuhan, China, on patients with COVID-19 pneumonitis managed with ECMO suggested a bleeding rate of 14% (3 out of 21 patients) without demonstrable coagulopathy in the study cohort.15 In particular, only 1 patient (4.7%) developed intracranial hemorrhage. This is congruent with the report from the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) registry, where in the initial months of the pandemic, central nervous system hemorrhage occurred in 6% of patients receiving ECMO for COVID-19.16 A review of 83 patients with COVID-19 pneumonitis managed with ECMO from Paris spanning a similar period to May 2020 demonstrated a 5% intracranial bleeding rate; however, the overall rate of massive hemorrhage was significantly higher (42%)17 (Table 1 ). The rate of intracranial bleeding was notably higher than the bleeding rate reported in the ECMO to Rescue Lung Injury in Severe ARDS (EOLIA) trial (2%).17 , 18 This has been attributed to higher dose anticoagulation regimens, SARS-CoV-2-associated vasculitis, and micro-bleeds associated with critical illness.

Table 1.

Studies Describing Bleeding and Thrombosis and Mortality in COVID-19 Patients Receiving veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

| Study | All Bleeding (%) | ICH (%) | All Thrombosis (%) | Pulmonary Embolism (%) | Ischemic Stroke (%) | Association with Mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schmidt et al.17 | 42 | 5 | N/A | 19 | 1 | N/A |

| Biancari et al.26 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 13.6 | 14.4 | PE: p = 0.079####Ischemic stroke: p = 0.146 |

| Shaefi et al.28 | 27.9 | 4.2 | 22.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | Bleeding: p < 0.001####Thrombosis: p = 0.23####PE: p = 0.26 |

| Arachchillage et al.1 | 30.9 | 10.5 | 53.3 | 29.6 | 3.9 | Bleeding: HR 3.87 (2.10-7.23)####PE: HR 1.63 (0.94-3.04)####ICH: HR 5.97 (2.36-15.04) |

| Garfield et al.27 | N/A | 20.8 | N/A | 69.8 | 11.3 | N/A |

| Doyle et al.19 | N/A | 16 | N/A | 37 | N/A | N/A |

NOTE. Figures in brackets represent the 95% confidence interval.

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; ICH, intracranial hemorrhage; N/A, not provided in the study data; p, p value; PE, pulmonary embolism.

An observational study from the United Kingdom looking at patients in the same period, where anticoagulation had been managed within a tight range (anti-Xa levels 0.3-0.5), showed an overall numerically lower bleeding rate (30.9%). However, the rates of intracranial hemorrhage were considerably higher (10.5%), a finding associated with a 5.97-fold increase in mortality.1 This suggests that the development of intracranial hemorrhage could be related in part to SARS-CoV-2-related vasculitis and inflammation rather than anticoagulation; however, their effects may be synergistic. A study comparing the bleeding and thrombosis rates between patients with COVID-19 and influenza pneumonitis who had similar characteristics and required ECMO support showed similar rates of intracerebral hemorrhage (16% v 14%).19

It would be plausible to hypothesize that intracranial hemorrhage may be related, at least in part, to the degree of inflammation associated with the viral infection, which is phenotypically expressed most in the sickest COVID-19 patients, a cohort that may be over-represented by those receiving ECMO. It is also plausible that the added inflammatory effect from being exposed to an extracorporeal circuit and the required anticoagulation would further amplify this effect. This hypothesis is supported by the lack of evidence of a reduction in bleeding rates when intravenous heparin anticoagulation is compared with alternative forms of systemic anticoagulation (eg, argatroban) both in COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 cohorts managed with ECMO.20 , 21 The impact of intracranial bleeding on mortality also was demonstrated in a recent analysis of the ELSO registry including all patients receiving ECMO for respiratory failure before the COVID-19 pandemic. Most of the patients had nonviral pneumonia (26.9%) with viral pneumonia constituting 20.6% of patients. Bleeding was associated strongly with in-hospital mortality with intracranial bleeding having the highest association with mortality (odds ratio 5.71 [4.02-8.09]).22

A recent review of the ELSO registry sought to identify the risk factors for bleeding in patients receiving veno-venous ECMO for respiratory failure from all causes.23 Factors such as pre-ECMO cardiac arrest, surgical cannulation, a greater degree of precannulation hypoxemia, severe metabolic and lactic acidosis, high respiratory rate with mechanical ventilation, pre-ECMO surgery, and shock were predictive of bleeding. These parameters were included in a prediction model to aid the identification of patients at risk of bleeding. In the context of COVID-19, the limitation of this model is that data on anticoagulation, laboratory results, and transfusion were not included, and the model could not account for the weighting of the cause of respiratory failure on the various clinical variables described in predicting bleeding. The model does suggest that the patients with risk factors that would be expected to increase bleeding risk are, in fact, more likely to bleed.23

Thrombosis

The prevalence of thrombosis in COVID-19 has been described extensively in the literature. The incidence of thrombosis has been reported to be between 20% and 30% in hospitalized patients,6 , 24 , 25 most of which is diagnosed as pulmonary embolism. In the context of ECMO support, pulmonary embolism could contribute to the physiological deterioration of the patient necessitating ongoing need for ECMO support or it may complicate the ECMO run.

During the first wave of the pandemic, an analysis of COVID-19 patients managed with ECMO in the United Kingdom showed a thrombosis incidence of 63% with the majority of patients presenting with isolated pulmonary embolism (29.6%).1 The development of pulmonary embolism was associated independently with mortality.1 In a French retrospective review undertaken also during the initial wave of COVID-19, the most prevalent thrombotic complication was found to be pulmonary embolism (19%).17 A similar trend has been demonstrated in other studies with the incidence being as high as 69.8% in one report.19 , 26, 27, 28 (Table 1). It is difficult to ascertain whether the pulmonary embolism in these studies developed before or after ECMO support was initiated. The comparative rate of pulmonary embolism in non-COVID 19 patients receiving ECMO is also difficult to ascertain. Data on the incidence and impact of pulmonary embolism was not collected in the EOLIA study.18

These findings align with recent reports describing the impact of right ventricular failure on COVID-19 outcomes.29 , 30 It is very likely that in addition to hypoxemia and hypercarbia, the added burden of pulmonary embolism in selected patients increases the afterload on the right ventricle despite optimal respiratory (veno-venous) ECMO support and ultra-lung protective ventilatory settings.

The ELSO registry in the first wave of the pandemic showed the rate of oxygenator failure was 9%.16 Oxygenator failure is most often attributed to the development of thrombi and hence this likely was driven by a thrombogenic process occurring in the ECMO circuit despite full anticoagulation.31 The above referenced reviews of patients in the United Kingdom and France found an incidence of ECMO circuit related thrombosis of 9.9%1 and 4%,17 respectively. The occurrence of ECMO circuit thrombosis was not found to be associated with increased mortality.1

Compared with adult respiratory ECMO cases in the year before the pandemic, the rates of complications associated with ECMO circuit thrombosis were similar once normalized for time on ECMO (which is longer in the COVID-19 patients).22 , 32 This is observational data does not account for changes in anticoagulation practices, which were known to have changed at many centers. Thrombosis rates per hour of ECMO are the same despite higher levels of anticoagulation in the COVID-19 cohort, suggesting a higher propensity for thrombosis. There is no evidence to definitively support this notion.

It has been reported recently that the incidence of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is higher in the context of COVID-19 disease managed with ECMO than in patients supported with ECMO for other indications. The reported incidence of HIT during ECMO in patients with COVID-19 is 10.52% (compared with 0.36%-7.8%33, 34, 35, 36 in the general non-COVID-19 ECMO cohorts) with 62.5% presenting with thrombosis.1 This may be an underestimate given the difficulties of diagnosing HIT in this context, with several other plausible causes of thrombocytopenia possible.37 A higher incidence of HIT is likely to be contributory to the increased incidence of thrombosis.

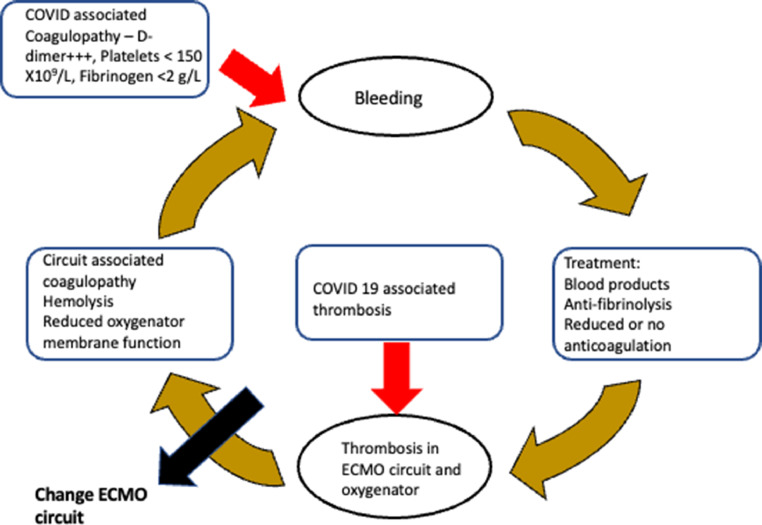

ECMO circuit thrombosis or failure creates challenges, especially if it is associated with significant bleeding. The interventions required to control bleeding such as transfusion of blood products and use fibrinolytics are likely to increase the clot burden in the ECMO circuit. Clots in the circuit would worsen the coagulopathy, cause hemolysis,38 and gas exchange in the membrane oxygenator would be impaired. This creates a vicious circle, which may necessitate the need to change the ECMO circuit. This is a complex and critical intervention that should be carried out by an experienced team after weighing the risks and benefits.38

Biochemical and Hematological Predictors of Coagulopathy

Many of the hallmark laboratory features of COVID-19 are reflective of a hyper-inflammatory state. 39 There is raised ferritin, C-reactive protein, white blood cell count, lymphopenia, raised fibrinogen, and elevated D-dimer. 39

A clinical phenotype characterized by increased bleeding tendency has been described and named COVID-19–associated coagulopathy. This is characterized by a 3- to 4-fold rise in D-dimer, a modest rise in prothrombin time, and thrombocytopenia (<150 × 109/L). These parameters have been associated with increased need for critical care and increased mortality rates among patients with COVID-19.40 , 41

Patients with severe COVID-19 presenting with low fibrinogen or overt disseminated intravascular coagulation have been found to have poor outcomes. C-reactive protein, white cell count, platelet count, prothrombin time, fibrinogen, and D-dimer are often recommended for inclusion as a key part of the laboratory profile required to assess COVID-19 patients.41

In one study, there was a strong association between thrombosis and a raised lactase dehydrogenase level.1 This is likely to be reflective of acute tissue damage and diffuse alveolar damage associated with COVID-19.

In the context of ECMO support with concurrent use of intravenous unfractionated heparin, ECMO-associated thrombin generation, cyto-trauma, and inflammation, it becomes more difficult to correctly ascribe any coagulation derangement seen to one specific etiology. 1 , 14 , 18 , 42

Patients presenting with laboratory features of COVID-19–associated coagulopathy either before or early during ECMO support would be expected to be more prone to developing clinically significant bleeding complications. Recent studies have yet to demonstrate this and associations with mortality have not been shown conclusively.1 , 17 The influence of COVID-19–associated coagulopathy is likely to act synergistically with the hyperinflammatory state associated with COVID-19 and ECMO to produce clinically significant bleeding and thrombosis.

Assessment and Management Recommendations

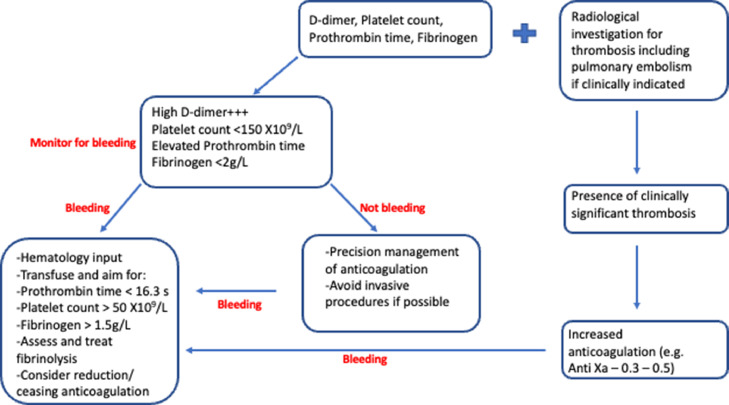

Given the clinical complexity and paucity of good quality evidence, firm conclusive recommendations are not available. Extrapolating from current knowledge data and experience, patients with COVID-19 receiving ECMO who are either bleeding or are at risk of bleeding, should undergo assessment of serum levels of D-dimer, prothrombin time, platelet count, and fibrinogen40 before and at clinically indicated intervals after initiation of ECMO support (Fig 1 ).

Fig 1.

Proposed algorithm for managing thrombosis and bleeding in COVID-19 patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

A low threshold is recommended to investigate pulmonary embolism and thrombosis in other anatomic regions as clinically indicated. Patients with thrombotic or embolic events should be managed appropriately with either increased heparin anticoagulation (eg, target anti-Xa levels 0.3-0.5) or, in the context of HIT or severe heparin resistance, alternative agents such as direct thrombin inhibitors (eg, argatroban).36

Pulmonary embolism occurring with hypotension, metabolic acidosis, and cardiogenic shock may be indicative of the presence of significant right ventricular dysfunction. Echocardiography in this context would be useful to guide management.43 Where right ventricular support is required, consideration should be given to ECMO configurations that would provide mechanical right ventricular support (eg, veno-venous arterial ECMO or veno-pulmonary arterial ECMO).44 , 45

Patients identified with COVID-19–associated coagulopathy should be assessed regularly for bleeding—this should be considered when planning for any surgical procedures (eg, percutaneous tracheostomy, thoracotomy, or chest drain insertion).

Patients with active bleeding should receive appropriate blood product replacement aiming for a platelet count >50 × 109/L, fibrinogen levels >1.5 g/L, and prothrombin time <16.3 seconds.40 The multidisciplinary management of the severely bleeding COVID-19 ECMO patient should include expert hematology input, where needed. In addition, close monitoring of the function and patency of the ECMO circuit should be carried out at regular intervals. This should include monitoring of oxygenator transmembrane pressure, oxygen transfer across the oxygenator membrane, as well as serum LDH and plasma free hemoglobin.38 This would facilitate the consideration of circuit-related coagulopathy occurring synergistically with COVID-19–associated coagulopathy for which an exchange of the ECMO circuit may be indicated (Fig 2 ).

Fig 2.

Vicious circle of bleeding and ECMO circuit thrombosis. ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Conclusions

The impact of bleeding and thrombosis on COVID-19 patients receiving ECMO is considerable and continues to be a major clinical feature of managing these patients, especially in those who do not survive. Expert manipulation and management of coagulation is required to reduce the impact on patient-centered outcomes. Future research should be directed at identifying the predictors of bleeding and thrombosis, as well as markers of prognosis in these patients, along with the selection of agents to improve coagulation management in this context.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

References

- 1.Arachchillage DJ, Rajakaruna I, Scott I, et al. Impact of major bleeding and thrombosis on 180-day survival in patients with severe COVID-19 supported with veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in the United Kingdom: A multicentre observational study. Br J Haematol. 2022;196:566–576. doi: 10.1111/bjh.17870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel BV, Arachchillage DJ, Ridge CA, et al. Pulmonary angiopathy in severe COVID-19: Physiologic, imaging, and hematologic observations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202:690–699. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202004-1412OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kowalewski M, Fina D, Słomka A, et al. COVID-19 and ECMO: The interplay between coagulation and inflammation - a narrative review. Crit Care. 2020;24:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02925-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abrams D, Ferguson ND, Brochard L, et al. ECMO for ARDS: From salvage to standard of care? Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7:108–110. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30506-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacLaren G, Fisher D, Brodie D. Treating the most critically ill patients with COVID-19: The evolving role of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. JAMA. 2022;327:31–32. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.22580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klok FA, Kruip MJHA, van der Meer NJM, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thrombo Res. 2020;191:145–147. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The REMAP-CAP, ACTIV-4a, and ATTACC Investigators Therapeutic anticoagulation with heparin in critically ill patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:777–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2103417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li W, Moore MJ, Vasllieva N, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature. 2003;426:450. doi: 10.1038/nature02145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yusuff H, Zochios V, Brodie D. Thrombosis and coagulopathy in COVID-19 patients requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. ASAIO J. 2020;66:844–846. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000001208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Millar JE, Fanning JP, McDonald CI, et al. The inflammatory response to extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO): A review of the pathophysiology. Crit Care. 2016;20:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1570-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryu KM, Chang SW. Heparin-free extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in a patient with severe pulmonary contusions and bronchial disruption. Clin Exp Emerg Med. 2018;5:204. doi: 10.15441/ceem.17.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee YY, Baik HJ, Lee H, et al. Heparin-free veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in a multiple trauma patient: A case report. Medicine. 2020;99:e19070. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000019070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doyle AJ, Hunt BJ. Current understanding of how extracorporeal membrane oxygenators activate haemostasis and other blood components. Front Med. 2018;5:352. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Masi P, Hékimian G, Lejeune M, et al. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome is a major contributor to COVID-19-associated coagulopathy: Insights from a prospective, single-center cohort study. Circulation. 2020;142:611–614. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.048925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang X, Cai S, Luo Y, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for coronavirus disease 2019-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome: A multicenter descriptive study. Crit Care Med. 2020:1289–1295. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barbaro RP, MacLaren G, Boonstra PS, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for COVID-19: Evolving outcomes from the international Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Registry. Lancet. 2021;398:1230–1238. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01960-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmidt M, Hajage D, Lebreton G, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome associated with COVID-19: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:1121–1131. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30328-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Combes A, Hajage D, Capellier G, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1965–1975. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doyle AJ, Hunt BJ, Sanderson B, et al. A comparison of thrombosis and hemorrhage rates in patients with severe respiratory failure due to coronavirus disease 2019 and influenza requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Crit Care Med. 2021;49:E663–E672. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fisser C, Winkler M, Malfertheiner MV, et al. Argatroban versus heparin in patients without heparin-induced thrombocytopenia during venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: A propensity-score matched study. Crit Care. 2021;25:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03581-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sattler LA, Boster JM, Ivins-O'Keefe KM, et al. Argatroban for anticoagulation in patients requiring venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in coronavirus disease 2019. Crit Care Explor. 2021;3:e0530. doi: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nunez JI, Gosling AF, O’Gara B, et al. Bleeding and thrombotic events in adults supported with venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: An ELSO registry analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2022;48(2):213–224. doi: 10.1007/s00134-021-06593-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Willers A, Swol J, van Kuijk SMJ, et al. HEROES V-V—HEmorRhagic cOmplications in Veno-Venous extracorporeal life support—development and internal validation of multivariable prediction model in adult patients. Artif Organs. 2022;46:932–952. doi: 10.1111/aor.14148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poissy J, Goutay J, Caplan M, et al. Pulmonary embolism in patients with COVID-19: Awareness of an increased prevalence. Circulation. 2020;142:184–186. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Middeldorp S, Coppens M, van Haaps TF, et al. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1995–2002. doi: 10.1111/jth.14888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Biancari F, Mariscalco G, Dalén M, et al. Six-month survival after extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe COVID-19. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2021;35:1999–2006. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2021.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garfield B, Bianchi P, Arachchillage D, et al. Six month mortality in patients with COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 viral pneumonitis managed with veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. ASAIO J. 2021;67:982–988. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000001527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaefi S, Brenner S, Gupta S, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in patients with severe respiratory failure from COVID-19. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47:208–221. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06331-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.ASAIO 66th Annual Conference June 2021 Conference Abstract Outcomes Of Covid-19 Patients With Right Ventricular Dysfunction Supported On Extra-corporeal Life Support Available at: https://asaio.org/conference/program/2021/COVID3-1.cgi. Accessed: 21st January 2022

- 30.Moody WE, Mahmoud-Elsayed HM, Senior J, et al. Impact of right ventricular dysfunction on mortality in patients hospitalized with COVID-19, according to race. CJC Open. 2021;3:91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.cjco.2020.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steiger T, Philipp A, Hiller KA, et al. Different mechanisms of oxygenator failure and high plasma von Willebrand factor antigen influence success and survival of venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.2021 Adult and Paediatric ECMO Anticoagulation Guidelines Available at: https://www.elso.org/Registry/InternationalSummary/Reports.aspx. Accessed: 21st January 2022

- 33.Sokolovic M, Pratt AK, Vukicevic V, et al. Platelet count trends and prevalence of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia in a cohort of extracorporeal membrane oxygenator patients. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:e1031–e1037. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kimmoun A, Oulehri W, Sonneville R, et al. Prevalence and outcome of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia diagnosed under veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: A retrospective nationwide study. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44:1460–1469. doi: 10.1007/s00134-018-5346-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glick D, Dzierba AL, Abrams D, et al. Clinically suspected heparin-induced thrombocytopenia during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Crit Care. 2015;30:1190–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.2021 Adult and Paediatric ECMO Anticoagulation Guidelines Available at: https://journals.lww.com/asaiojournal/Citation/9000/2021_ELSO_Adult_and_Pediatric_Anticoagulation.98078.aspx. Accessed: 21st January 2022

- 37.Lippi G, Plebani M, Henry BM. Thrombocytopenia is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections: A meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;506:145–148. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zakhary B, Vercaemst L, Mason P, et al. How I approach membrane lung dysfunction in patients receiving ECMO. Crit Care. 2020;24:1–4. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03388-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thachil J, Tang N, Gando S, et al. ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1023–1026. doi: 10.1111/jth.14810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tang N, Li D, Wang X, et al. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:844–847. doi: 10.1111/jth.14768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lebreton G, Schmidt M, Ponnaiah M, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation network organisation and clinical outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic in Greater Paris, France: A multicentre cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9:851–862. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00096-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bleakley C, Singh S, Garfield B, et al. Right ventricular dysfunction in critically ill COVID-19 ARDS. Int J Cardiol. 2021;327:251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.11.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tatooles AJ, Mustafa AK, Alexander PJ, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for patients with COVID-19 in severe respiratory failure. JAMA Surg. 2020;155:990–992. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.3950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kapur NK, Esposito ML, Bader Y, et al. Mechanical circulatory support devices for acute right ventricular failure. Circulation. 2017;136:314–326. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.025290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]