Abstract

The ErmB macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B (MLS) resistance determinant from Clostridium difficile 630 contains two copies of an erm(B) gene, separated by a 1.34-kb direct repeat also found in an Erm(B) determinant from Clostridium perfringens. In addition, both erm(B) genes are flanked by variants of the direct repeat sequence. This genetic arrangement is novel for an ErmB MLS resistance determinant.

Clostridium difficile is the causative agent of antibiotic-associated diarrhea and pseudomembranous colitis, diseases generally associated with exposure to antibiotics. The antibiotics most commonly involved include clindamycin, cephalosporins, and ampicillin (2); however, virtually all antibacterial agents have been implicated.

Erythromycin is a member of the macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B (MLS) group of protein synthesis inhibitors (11, 16). In many bacterial species (4, 6, 11, 12), MLS resistance is mediated by erm genes, which encode 23S RNA methylases. Numerous erm genes have been characterized and divided into distinct classes based on their sequence similarity (19). The most widely distributed of these classes of Erm determinants is the Erm B/AM class, which has recently been renamed as the ErmB class (19), the erm genes belonging to this class now being referred to as erm(B) genes (19).

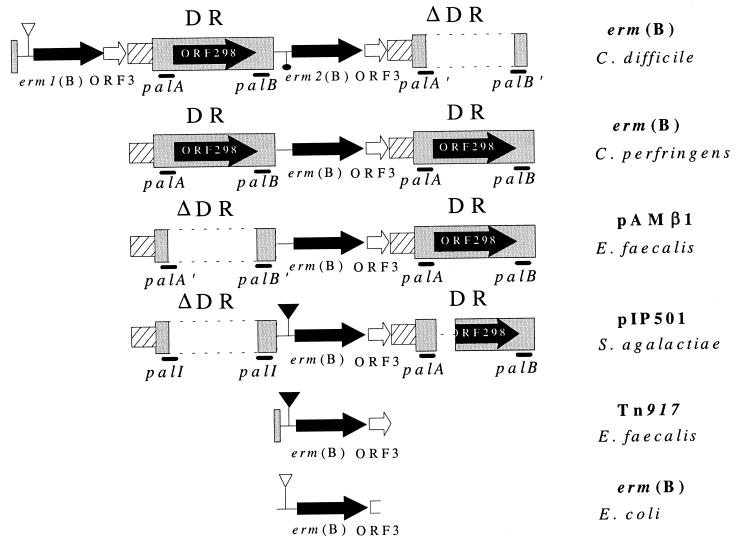

ErmB determinants have been detected in both Clostridium perfringens (3) and C. difficile (9, 21). The C. perfringens determinant is located on a large mobilizable plasmid, pIP402, and consists of an erm(B) gene (previously ermBP) flanked by 1.34-kb direct repeat (DR) sequences (4) (Fig. 1). Each DR contains an open reading frame (ORF), ORF298, the putative product of which has similarity to ParA and Soj proteins, which are involved in plasmid and chromosomal partitioning (8, 23). ORF298 is flanked by the highly palindromic repeated sequences of palA and palB (4).

FIG. 1.

Comparative genetic organization of the Erm(B) determinants from C. difficile, C. perfringens (4), Enterococcus faecalis (pAMβ1) (14), Streptococcus agalactiae (pIP501) (18), E. faecalis (Tn917) (24), and Escherichia coli (6). The approximate extent and organization of the determinants are shown schematically and are not necessarily to scale. Regions of nucleotide sequence similarity are indicated by the same shading. The solid arrows indicate the individual ORFs and their respective direction of transcription. The approximate location of the palindromic sequences (palA and palB) is indicated by the boldface lines below the shaded boxes. The palA′, palB′, and palI sequences represent the portions of the C. perfringens erm(B)-derived palA and palB homologues that are present at the ends of the deletion in these variants of the DR sequence. Functional and nonfunctional leader peptide sequences are indicated by solid and open triangles respectively. The promoter deletion upstream of the C. difficile erm2(B) gene is indicated by the solid oval. The region of pIP501 for which no sequence data are available is indicated by a single broken line. This comparison varies slightly from the previously published figure (Fig. 2 in reference 4).

Hybridization analysis of erythromycin-resistant C. difficile strains has also revealed the presence of erm(B) genes (previously ermZ or ermBZ) (9, 21). The objective of our studies was to examine the genetic organization of the ErmB determinant from C. difficile 630. This strain (28) was grown at 37°C in an anaerobic glove chamber (Coy Laboratories; 80% N2, 10% H2, 10% CO2) in BHIS medium (25) supplemented with erythromycin (50 μg/ml) or rifampin (20 μg/ml). C. perfringens CP592 (5) was grown anaerobically on nutrient agar (20) containing erythromycin (50 μg/ml). Recombinant strains were derivatives of Escherichia coli DH5α (Bethesda Research Laboratories, Inc.) and were grown in 2YT medium (17) containing erythromycin (150 μg/ml).

Cloning experiments (22) utilized the low-copy-number E. coli plasmid vector pWSK29 (27). Small-scale plasmid DNA isolation was performed by a modified mini alkaline-lysis–polyethylene glycol precipitation procedure (Applied Biosystems). DNA sequencing was carried out with the ABI Prism Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction kit on an Applied Biosystems 373 DNA sequencer. DNA was prepared from both C. difficile and C. perfringens by dye buoyant density gradient ultracentrifugation at 260,000 × g for 20 h at 20°C (1).

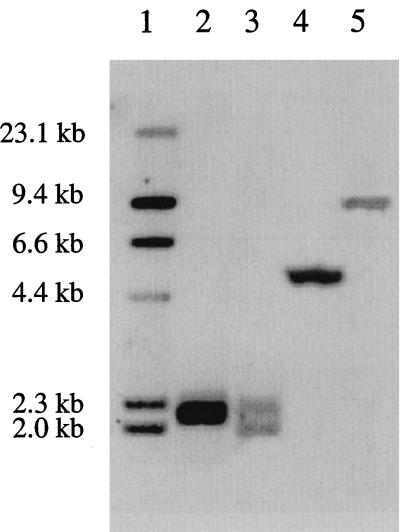

To determine the size of the C. difficile 630 fragment carrying the erm(B) gene, chromosomal DNA samples (10 μg) were digested with Sau3A or HindIII and separated by electrophoresis on 0.8% agarose. Southern blots (26) were probed at high stringency with a 688-bp erm(B)-specific digoxigenin-labelled probe prepared by PCR with the primers 2980 (5′AATAAGTAAACAGGTAACGTT 3′) and 2981 (5′GCTCCTTGGAAGCTGTCAGTAG 3′). A single hybridizing 9.7-kb HindIII band was observed (Fig. 2) after washing at high stringency and probe detection with CDP-Star (Boehringer-Mannheim). However, after Sau3A digestion, two hybridizing bands of 2.0 and 2.3 kb were evident (Fig. 2). In contrast, with DNA from C. perfringens CP592, only single hybridizing bands were detected with each enzyme (Fig. 2). The presence of two hybridizing Sau3A bands in strain 630 DNA suggested that either there were two erm(B) genes separated by less than 9.7 kb, or there was a single erm(B) gene which contained an internal Sau3A site that was not present in the erm(B) gene from C. perfringens.

FIG. 2.

Southern hybridization analysis. Analysis of C. difficile 630 (lanes 3 and 5) and C. perfringens CP592 (lanes 2 and 4) DNA with an erm(B)-specific probe. DNA was digested with either Sau3A (lanes 2 and 3) or HindIII (lanes 4 and 5). Digoxigenin-labelled λcI857HindIII standards are shown (lane 1).

The 9.7-kb HindIII fragment from strain 630 was cloned into pWSK29, and the erm(B) gene region of the recombinant plasmid, pJIR1594, was completely sequenced on both strands across all restriction sites. Sequence analysis revealed that this ErmB determinant had a novel genetic organization. Two identical copies of the erm(B) gene were present, which we have designated as erm1(B) and erm2(B) (Fig. 1). The genes had 99% sequence identity to the erm(B) gene from C. perfringens and greater than 97% sequence identity to all other erm(B) genes. In addition, the two genes were separated by a single complete copy of the DR sequence that is found on either side of the C. perfringens erm(B) gene and in association with most of the other erm(B) genes (Fig. 1).

Upstream of erm2(B) was an apparent deletion that removed the erm(B) promoter. It is therefore unlikely that the erm2(B) gene is expressed; however, expression from an upstream promoter such as the erm1(B), ORF3, or ORF298 promoters cannot be ignored.

Upstream of erm1(B) was a potential erm leader peptide sequence, a potential promoter, and 75 bp of the DR sequence (Fig. 1). Leader peptide sequences are commonly found upstream of inducible erm genes (7). The leader peptide gene region contains a number of inverted repeats and leads to the regulation of erm expression by translational attenuation (15). Based on the similarity of the upstream region of other erm genes to the leader peptide sequence upstream of erm(C), several other erm genes, including some erm(B) genes, have been proposed to be regulated by translational attenuation. Examination of constitutive erm genes showed that the leader peptide sequence was either absent or was mutated and nonfunctional (10, 15). Analysis of the leader peptide sequence upstream of erm1(B) indicated that it was similar to nonfunctional leader peptides. Therefore, induction experiments were carried out to determine whether erythromycin resistance was constitutively or inducibly expressed in strain 630. The results showed that when the cells were subcultured from medium that did not contain erythromycin, the same growth rate was observed in the presence or absence of erythromycin (data not shown), suggesting that the erm1(B) leader peptide is not functional in strain 630 and that erythromycin resistance is constitutively expressed.

Downstream of both erm1(B) and erm2(B) was ORF3, which is found in the same position in virtually all ErmB determinants (13) (Fig. 1). Further downstream of erm2(B) was a variant of the DR sequence. This variant contained a deletion that had removed ORF298 and another deletion that appeared to have removed the last 75 bp of the DR sequence. This region was identical to the 75 bp of the DR found upstream of erm1(B), suggesting that other recombination events may also have occurred.

Comparative analysis (Fig. 1) of the various ErmB determinants revealed that the C. difficile 630 determinant is the only member of this class which has two erm structural genes. In addition, almost all of the erm(B) genes are flanked by complete or deleted (ΔDR) variants of the DR sequence. None of these variants are identical, each deletion apparently having occurred at a slightly different location. Therefore, it is likely that homologous recombination events involving the palA and palB sequences are responsible for the deletions, rather than site-specific recombination events.

The only erm(B) gene that is flanked by two complete copies of the DR sequence is from C. perfringens. We previously postulated that this determinant represents the ErmB progenitor and that the other determinants have arisen through homologous recombination events which remove part of the DR sequences (4). We propose that the evolution of the C. difficile determinant may have involved a duplication of the putative progenitor determinant with subsequent recombination events, which resulted in two erm(B) genes separated by a complete copy of the DR sequence.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The GenBank accession number of the DNA sequence of the C. difficile ErmB determinant is AF109075.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council for research support.

K.A.F. was the recipient of an Australian Postgraduate Award.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abraham L J, Rood J I. Molecular analysis of transferable tetracycline resistance plasmids from Clostridium perfringens. J Bacteriol. 1985;161:636–640. doi: 10.1128/jb.161.2.636-640.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartlett J G. Antimicrobial agents implicated in Clostridium difficile toxin associated diarrhea or colitis. Johns Hopkins Med J. 1981;149:6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berryman D I, Rood J I. Cloning and hybridization analysis of ermP, a macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B resistance determinant from Clostridium perfringens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:1346–1353. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.8.1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berryman D I, Rood J I. The closely related ermB-ermAM genes from Clostridium perfringens, Enterococcus faecalis (pAMβ1), and Streptococcus agalactiae (pIP501) are flanked by variants of a directly repeated sequence. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1830–1834. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.8.1830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brefort G, Magot M, Ionesco H, Sebald M. Characterization and transferability of Clostridium perfringens plasmids. Plasmid. 1977;1:52–66. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(77)90008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brisson-Noël A, Arthur M, Courvalin P. Evidence for natural gene transfer from gram-positive cocci to Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:1739–1745. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.4.1739-1745.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dubnau D, Monod M. The regulation and evolution of MLS resistance. Banbury Rep. 1986;24:369–387. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Easter C L, Schwab H, Helinski D R. Role of the parCBA operon of the broad-host-range plasmid RK2 in stable plasmid maintenance. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6023–6030. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.22.6023-6030.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hächler H, Berger-Bächi B, Kayser F H. Genetic characterization of a Clostridium difficile erythromycin-clindamycin resistance determinant that is transferable to Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987;31:1039–1045. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.7.1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamimiya S, Weisblum B. Translational attenuation control of ermSF, an inducible resistance determinant encoding rRNA N-methyltransferase from Streptomyces fradiae. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:1800–1811. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.4.1800-1811.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.LeClerq R, Courvalin P. Bacterial resistance to macrolide, lincosamide, and streptogramin antibiotics by target modification. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1267–1272. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.7.1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.LeClerq R, Courvalin P. Intrinsic and unusual resistance to macrolide, lincosamide, and streptogramin antibiotics in bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1273–1276. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.7.1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lyras D, Rood J I. Transposable genetic elements and antibiotic resistance determinants from Clostridium perfringens and Clostridium difficile. In: Rood J, McClane B, Songer J, Titball R, editors. The clostridia: molecular biology and pathogenesis. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1997. pp. 73–92. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin B, Alloing G, Mejean V, Claverys J-P. Constitutive expression of erythromycin resistance mediated by the ermAM determinant of plasmid pAM-beta-1 results from deletion of 5′ leader peptide sequences. Plasmid. 1987;18:250–253. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(87)90068-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mayford M, Weisblum B. The ermC leader peptide: amino acid alterations leading to differential efficiency of induction by macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B antibiotics. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3772–3779. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.7.3772-3779.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Menninger J R. Functional consequences of binding macrolides to ribosomes. J Mol Biol. 1985;16:23–24. doi: 10.1093/jac/16.suppl_a.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pujol C, Ehrlich S, Janniere L. The promiscuous plasmids pIP501 and pAMβ1 from Gram-positive bacteria encode complementary resolution functions. Plasmid. 1994;31:100–105. doi: 10.1006/plas.1994.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roberts M C, Sutcliffe J, Courvalin P, Jensen L B, Rood J I, Seppala H. Nomenclature for macrolide and macrolide-lincosamide Streptogramin B antibiotic resistance determinants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2823–2830. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.12.2823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rood J I. Transferable tetracycline resistance in Clostridium perfringens strains of porcine origin. Can J Microbiol. 1983;29:1241–1246. doi: 10.1139/m83-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rood J I, Cole S T. Molecular genetics and pathogenesis of Clostridium perfringens. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:621–648. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.4.621-648.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharpe M E, Errington J. The Bacillus subtilis soj-spoOJ locus is required for a centromere-like function involved in prespore chromosome partitioning. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:501–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shaw J H, Clewell D B. Complete nucleotide sequence of macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B-resistance transposon Tn917 in Streptococcus faecalis. J Bacteriol. 1985;164:782–796. doi: 10.1128/jb.164.2.782-796.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith C J, Markowitz S M, Macrina F L. Transferable tetracycline resistance in Clostridium difficile. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1981;19:997–1003. doi: 10.1128/aac.19.6.997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Southern E M. Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. J Mol Biol. 1975;98:503–517. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang R F, Kushner S R. Construction of versatile low-copy-number vectors for cloning, sequencing and gene expression in Escherichia coli. Gene. 1991;100:195–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wüst J, Hardegger U. Transferable resistance to clindamycin, erythromycin, and tetracycline in Clostridium difficile. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1983;23:784–786. doi: 10.1128/aac.23.5.784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]