Abstract

Treatment of EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with mutation-selective third generation EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs) such as osimertinib has achieved remarkable success in the clinic. However, the immediate challenge is the emergence of acquired resistance, limiting the long-term remission of patients. This study suggests a novel strategy to overcome acquired resistance to osimertinib and other third generation EGFR-TKIs through directly targeting the intrinsic apoptotic pathway. We found that osimertinib, when combined with Mcl-1 inhibition or Bax activation, synergistically decreased the survival of different osimertinib-resistant cell lines, enhanced the induction of intrinsic apoptosis, and inhibited the growth of osimertinib-resistant tumor in vivo. Interestingly, the triple- combination of osimertinib with Mcl-1 inhibition and Bax activation exhibited the most potent activity in decreasing the survival and inducing apoptosis of osimertinib-resistant cells and in suppressing the growth of osimertinib-resistant tumors. These effects were associated with increased activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway evidenced by augmented mitochondrial cytochrome C and Smac release. Hence, this study convincingly demonstrates a novel strategy for overcoming acquired resistance to osimertinib and other 3rd generation EGFR-TKIs by targeting activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway through Mcl-1 inhibition, Bax activation or both, warranting further clinical validation of this strategy.

Keywords: EGFR inhibitors, osimertinib, acquired resistance, apoptosis, Mcl-1, Bax, lung cancer

Introduction

Lung cancer, which consists of over 80% non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), remains the leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide 1. Although targeted therapy of NSCLC with activating EGFR mutations has achieved favorable clinical outcomes, drug resistance to early-generation epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs) such as gefitinib, erlotinib and afatinib is inevitable within 14 months due to the acquisition of EGFR resistance mutations such as T790M 2, 3. Accordingly, osimertinib (AZD9291), almonertinib (Ameile; HS-10296) and other third generation EGFR-TKIs designed to target EGFR T790M mutation have been developed.

As an irreversible EGFR-TKI, osimertinib is selective for both T790M as well as common activating EGFR mutations including exon 19 deletion (19Del) and exon 21 L858R point mutation 3, 4. Aside from being a second-line remedy to T790M related resistance, osimertinib has become a standard first-line option for the treatment of advanced NSCLC with activating EGFR mutations based on its successes in clinical trials 5, 6. Nevertheless, as with other EGFR-TKIs, drug resistance to osimertinib is inevitable whether being used as a first-line or second-line medication, resulting in tumor progression and eventual treatment failure 4, 7. Therefore, developing strategies to overcome acquired drug resistance to osimertinib is imperative for the purpose of achieving long-term NSCLC survival in the clinic.

Myeloid cell leukemia 1 (Mcl-1) is a member of Bcl-2 protein family that negatively regulates the intrinsic mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. It has also been suggested to be involved in the pathogenesis of multiple malignances, including lung cancer. Accordingly, several Mcl-1 inhibitors including S63845, AZD5991 and APG3526 have been developed as potential cancer therapeutic agents 8, 9. Our previous study has shown that Mcl-1 degradation plays a major role in inducing apoptotic cell death by osimertinib, a key mechanism accounting for osimertinib’s therapeutic efficacy 10. Once acquiring resistance, Mcl-1 is no longer downregulated by osimertinib, representing a possible mechanism contributing to the acquisition of osimertinib resistance 10.

Bax is a major pro-apoptotic protein that is also recognized as a potential cancer therapeutic target, since it initiates intrinsic apoptosis when segregated from its binding protein Mcl-1, resulting in cytochrome C (Cyt C) and Smac release from the mitochondria followed by the activation of caspase cascades and apoptosis 11, 12. Accordingly, several small molecule Bax activators or agonists including CYD-2-11 have been developed as potential cancer therapeutics 11, 13, 14. CYD-2-11, an in-house developed Bax agonist, was proven to be effective against the growth of NSCLC cells or tumors through directly activating intrinsic apoptosis 13, 14.

Considering activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway as a key mechanism accounting for the therapeutic efficacy of osimertinib, and inability to induce apoptosis as a mechanism underlying acquired resistance to osimertinib 10, we reasonably hypothesized that activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway through directly inhibiting Mcl-1, activating Bax, or both might sensitize osimertinib-resistant cells to osimertinib, achieving the goal of overcoming acquired resistance to osimertinib and even other third generation EGFR-TKIs. Hence, this study focused on testing this novel strategy. We found that both Mcl-1 inhibitors and Bax agonist, when combined with osimertinib, effectively or synergistically decreased survival and enhanced apoptosis of different osimertinib-resistant cell lines, resulting in significantly enhanced anti-tumor activity of osimertinib in vivo. In addition, the three-drug combination of osimertinib, Mcl-1 inhibitor and CYD-2-11 exhibited very effective activity again the growth of osimertinib-resistant cells and tumors including induction of apoptosis. Hence, our findings suggest a novel and effective strategy to overcome acquired resistance to osimertinib and possibly other third generation EGFR-TKIs, warranting the future clinical validation of this therapeutic strategy.

Results

Mcl-1 inhibition synergizes with osimertinib or almonertinib to decrease the survival of osimertinib-resistant cells with enhanced induction of apoptosis.

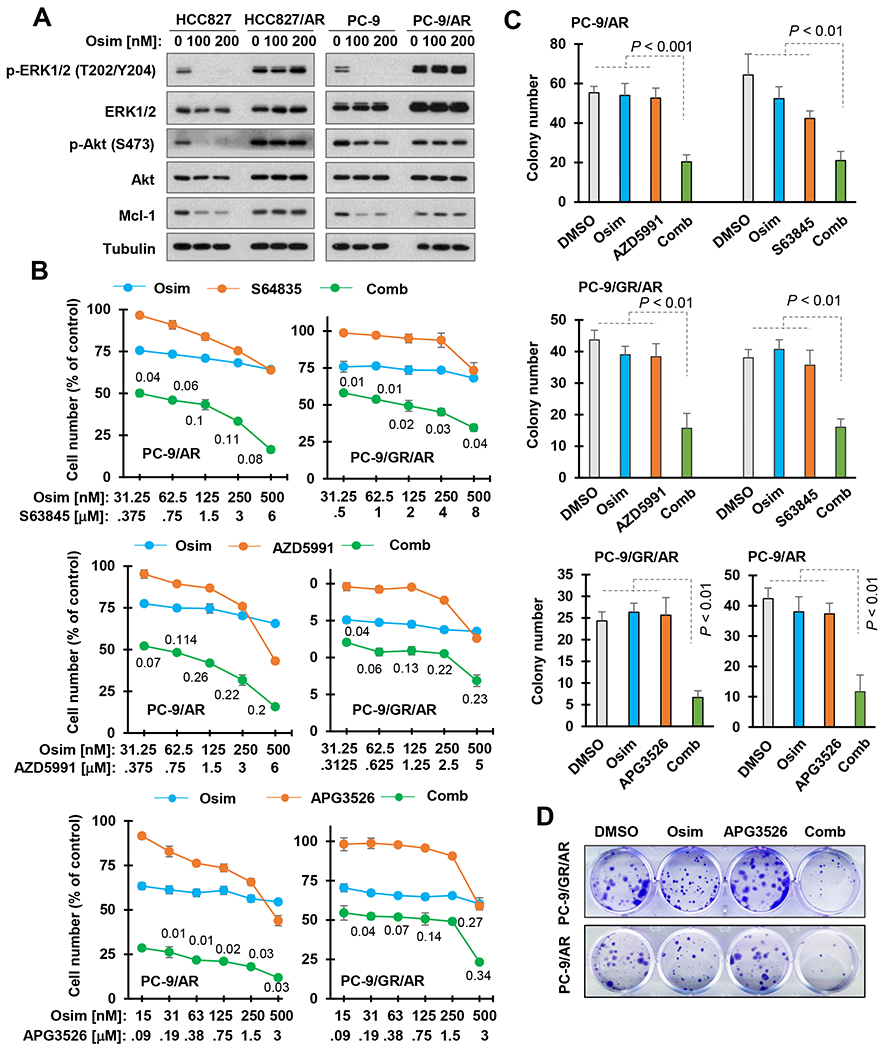

Osimertinib at the tested conditions effectively decreased the levels of p-ERK and p-Akt, two well-known events downstream of EGFR, accompanied with Mcl-1 reduction in sensitive HCC827 and PC-9 cells, but not in the corresponding osimertinib-resistant cell lines derived from them (Fig. 1A), confirming our previous findings 10. We then determined whether direct inhibition of Mcl-1 with an Mcl-1 inhibitor in combination with osimertinib exerts enhanced effect on decreasing the survival of EGFR mutant (EGFRm) NSCLC cell lines with acquired osimertinib resistance, including PC9-AR (resistant to osimertinib with unknown mechanism), PC-9/GR/AR (resistant to erlotinib due to EGFR T790M mutation and then to osimertinib) and HCC827/AR (resistant to osimertinib due to MET amplification) 15. To this end, we used 3 different Mcl-1 inhibitors including S63845, AZD5991 and APG3526 8, 9 to avoid potential off-target effects and generate robust findings. The combination of osimertinib with either of the 3 tested Mcl-1 inhibitors was much more potent than each agent alone in decreasing the survival of both PC-9/AR and PC-9/GR/AR cell lines, with combination indexes (CIs) CIs far below 1 (Fig. 1B), indicating synergistic effects. Similar results were also generated in HCC827/AR cells (Fig. S1A). However, the combination of osimertinib with either S63845 or APG3526 minimally enhanced the effect of decreasing the survival of PC-9/3M (engineered cell line with expression of EGFR 19del, T790M and C797S triple mutations) cells (Fig. S1B). The colony formation assay, which allows long-term repeated treatments, also demonstrated the significantly enhanced effects of the combinations on suppressing colony formation and growth of both PC-9/AR and PC-9/GR/AR cells in comparison with each single agent alone (Figs. 1B and C). Furthermore, we transiently knocked down Mcl-1 expression using Mcl-1 siRNA in PC-9/AR cells and then exposed the cells to osimertinib. We found that genetic inhibition of Mcl-1 by gene knockdown also sensitized the tested osimertinib-resistant cell line to osimertinib (Fig. S2), consistent with the date generated with different Mcl-1 inhibitors as discussed above.

Fig. 1. The combination of osimertinib with an Mcl-1 inhibitor synergistically decreases the survival of osimertinib-resistant cell lines (B-D), which are resistant to Mcl-1 modulation by osimertinib (A).

A, The given cell lines were exposed to the indicated concentrations of osimertinib (Osim) for 8 h before being harvested for Western blot analysis. B, The given osimertinib-resistant cell lines seeded in 96-well plates were treated with varied concentrations of tested agents alone or in combination as indicated. After 72 h, cell numbers were estimated with the SRB assay. Data are means ± SDs of triplicate determinations. The numbers in the graphs are CIs. C and D, The given cell lines in 24-well plates were repeatedly treated with DMSO, 200 nM osimertinib, 500 nM Mcl-1 inhibitor or osimertinib plus Mcl-1 inhibitor every 3 days. After 10 days, the plates were fixed and stained. Data are means ± SDs of triplicate wells.

Almonertinib, a newly approved 3rd generation EGFR-TKI in China, selectively and effectively decreased the survival of EGFRm NSCLC cell lines (e.g., PC-9 and HCC827) as osimertinib did. Osimertinib-resistant cell lines were also insensitive to almonertinib (Fig. S3), indicating cross-resistance. Hence, we further tested the effects of almonertinib combined with Mcl-1 inhibition using either S63845 or AZD5991 on the growth of osimertinib-resistant cells. Similarly, these combinations also synergistically decreased the survival of osimertinib-resistant cell lines (Fig. S4).

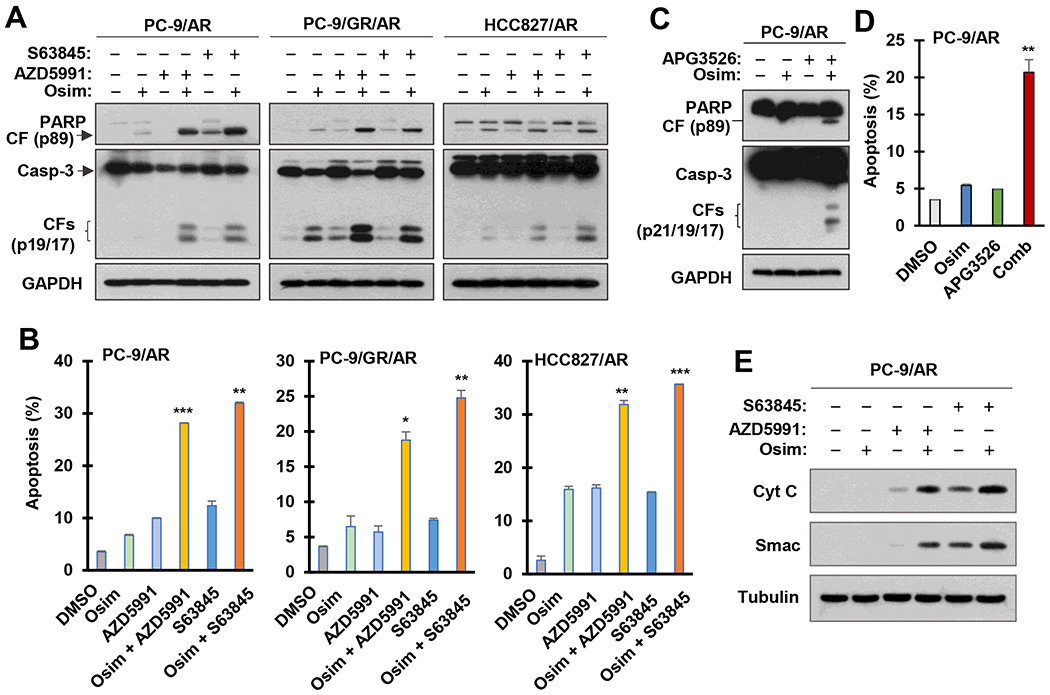

We then determined whether Mcl-1 inhibition synergizes with osimertinib to augment induction of apoptosis in osimertinib-resistant cells. We found that the levels of cleaved PARP and caspase-3 in either of the tested osimertinib-resistant cell lines exposed to the combination of osimertinib with S63845 or AZD5991 were much higher than those in the cells treated with either agent alone (Fig. 2A). In agreement, the highest proportions of annexin V-positive cells (apoptotic cells) were detected in these resistant cell lines exposed to the combination of osimertinib with S63845 or AZD5991 and were significantly higher than those in cells treated with either single agent alone (Fig. 2B). Similar results were generated with the combination of osimertinib and APG3526 (Fig. 2C and D). Moreover, we determined whether the combinations indeed enhance activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway by detecting cytosolic release of Cyt C and Smac from mitochondria. As expected, the cytosolic levels of both Cyt C and Smac were much higher in PC-9/AR cells exposed to the combination of osimertinib with S63845 or AZD5991 than in the cells treated with either single agent (Fig. 2E), indicating enhanced activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway. Consistently, Mcl-1 knockdown in PC-9/AR cells also sensitized the cells to undergo apoptosis induced by osimertinib (Fig. S2). Collectively, we concluded that the combination of osimertinib with Mcl-1 inhibition augments the induction of intrinsic apoptosis in osimertinib-resistant cell lines.

Fig. 2. The combination of osimertinib with an Mcl-1 inhibitor augments the induction of apoptosis (A-D) with enhanced mitochondrial release of Cyt C and Smac (E).

A and B, The tested cell lines were exposed to DMSO, 200 nM osimertinib (Osim), 3 μM (PC-9/AR) or 5 μM (PC-9/GR/AR and HCC827/AR) AZD5991 or S63845, and their respective combinations as indicated for 24 h (PC-9/AR) or 48 h (PC-9/GR/AR and HCC827/AR). C and D, PC-9/AR cells were treated with DMSO, 200 nM osimertinib, 2 μM APG3526 and the combination of osimertinib and APG3526 for 24 h (C) or 72 h (D). Western blotting was used to detect the indicated proteins (A and C) and annexin V staining/flow cytometry was used to measure apoptosis (B and D). Data are means ± SDs of duplicate determinations (B and D). E, PC-9/AR cells were exposed to DMSO, 200 nM osimertinib, 3 μM APG3526 and the combination of osimertinib and APG3526 for 10 h. Cytosolic fractions were then prepared followed by Western blotting for the detection of the indicated proteins.

Osimertinib combined with a Bax activator synergistically decreases the survival of osimertinib-resistant cells through enhanced induction of apoptosis.

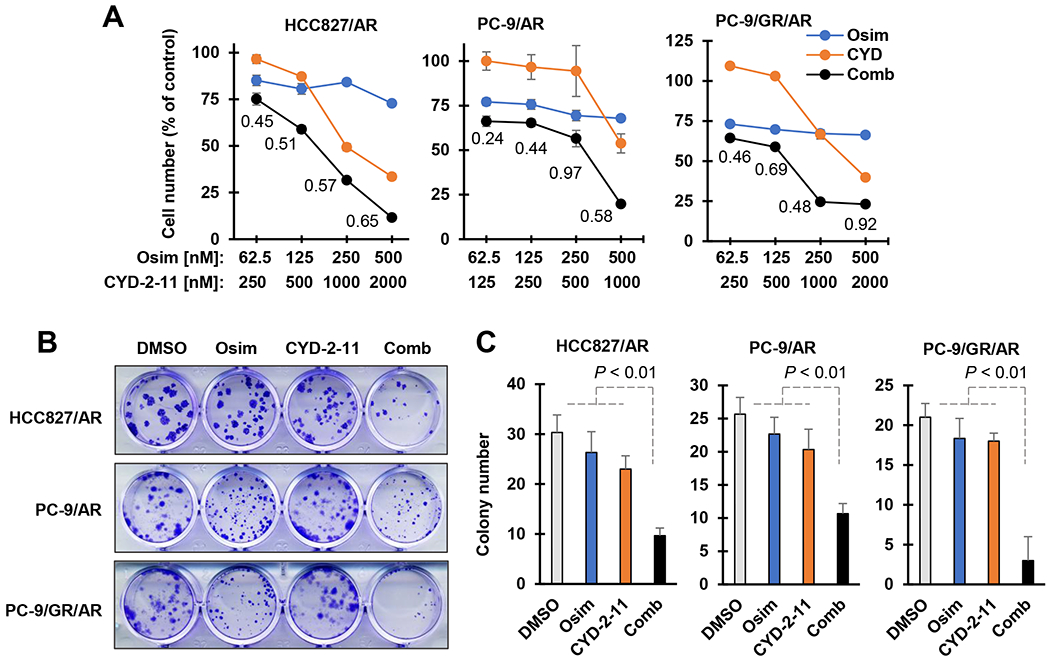

Since Mcl-1 inhibition results in the induction of apoptosis through Bax or Bak activation 9, we plausibly asked whether direct activation of Bax achieves a similar outcome in terms of enhancing osimertinib-induced apoptosis in osimertinib-resistant cells. Hence, we determined the effects of osimertinib combined with CYD-2-11, an in-house developed Bax activator 13, 14, on the growth of osimertinib-resistant cells and induction of apoptosis. As presented in Fig. 3A, the combination of osimertinib with CYD-2-11 was more active than either agent alone in decreasing the survival of three osimertinib-resistant cell lines, PC-9/AR, PC-9/GR/AR and HCC827/AR, with CIs of < 1 (Fig. 3A). Consistently, the clear long-term effects of the combination on colony formation and growth of these resistant cell lines were also observed, i.e., the combination significantly inhibited the formation and growth of osimertinib-resistant cell colonies, while either single agent had little or no effect (Fig. 3B and C). Moreover, the combination of CYD-2-11 with almonertinib was also more effective than either single agent in suppressing colony formation and growth of the same osimertinib-resistant cell lines, PC-9/AR, PC-9/GR/AR and HCC827/AR cells (Fig. S5).

Fig. 3. The combination of osimertinib with a Bax activator synergistically decreases the survival of osimertinib-resistant cell lines.

A, The tested osimertinib-resistant cell lines seeded in 96-well plates were exposed to varied concentrations of tested agents alone or in combination as indicated for 72 h. Cell numbers were estimated with the SRB assay. Data are means ± SDs of triplicate determinations. The numbers in the graphs are CIs. B and C, The tested cell lines in 24-well plates were repeatedly treated with DMSO, 200 nM osimertinib (Osim), 200 nM (PC-9/AR and PC-9/GR/AR) or 300 nM (HCC827/AR) CYD-2-11 (CYD) or osimertinib combined with CYD-2-11 every 3 days. After 10 days, the plates were fixed and stained. Data are means ± SDs of triplicate wells.

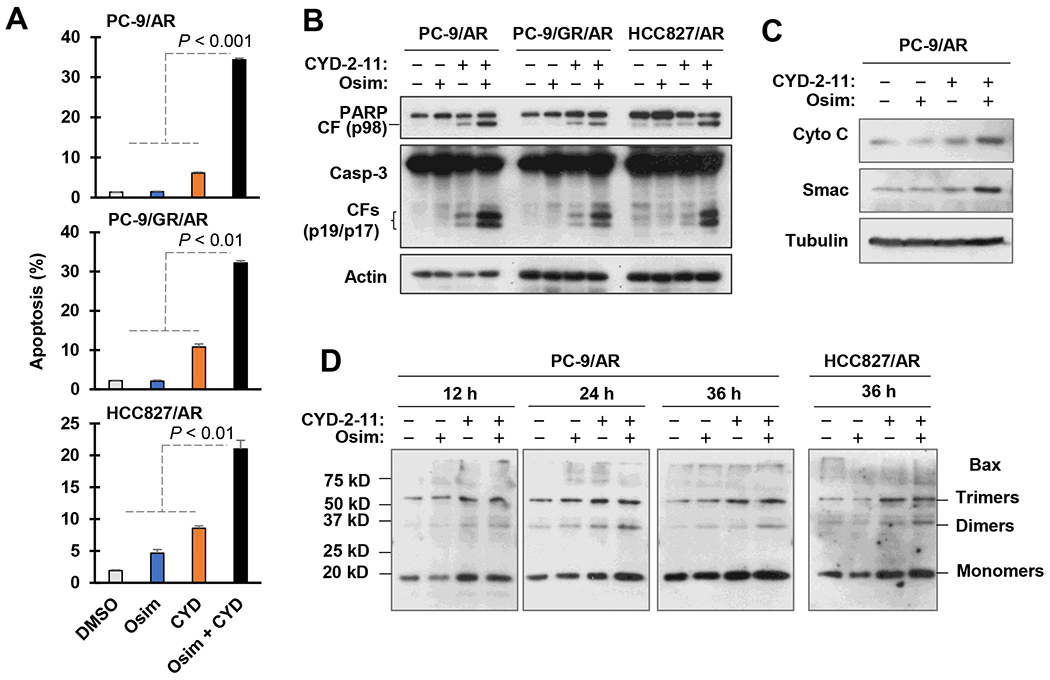

We next determined whether the combination of osimertinib and CYD-2-11 enhances apoptosis, thereby augmenting the decrease in survival of osimertinib-resistant cells. Indeed, the CYD2-11 and osimertinib combination was significantly more effective than each single agent in increasing annexin V-positive cell populations (Fig. 4A) and cleaved amounts of both caspase-3 and PARP (Fig. 4B) in all three tested osimertinib-resistant cell lines (PC-9/AR, PC-9/GR/AR and HCC827/AR). Furthermore, enhanced mitochondrial release of Cyt C and Smac into the cytosol was visualized in cells receiving the combination treatment compared to CYD-2-11 or osimertinib treatment alone (Fig. 4C). These results together clearly indicate that the combination of CYD-2-11 and osimertinib enhances intrinsic apoptosis in osimertinib-resistant cells. We also determined whether CYD-2-11 indeed activates Bax in these osimertinib-resistant cell lines through detection of Bax oligomerization in mitochondria. In addition to monomers, Bax trimers and dimers were upregulated in both PC-9/AR and HCC827/AR cells exposed to CYD-2-11 or its combination with osimertinib (Fig. 4D), indicating the ability of CYD-2-11 to activate mitochondrial Bax. In short, combining a Bax activator with osimertinib synergistically decreases the survival of osimertinib-resistant cell lines by enhancing the induction of intrinsic apoptosis.

Fig. 4. The combination of osimetrtinib with a Bax activator enhances induction of apoptosis (A and B), mitochondrial release of Cyt C and Smac (C) and Bax oligomerization (D).

A and B, The tested cell lines were exposed to DMSO, 200 nM osimertinib (Osim), 1 μM (PC-9/AR and PC-9/GR/AR) or 2 μM (HCC827/AR) CYD2-11 (CYD), and their combinations as indicated for 48 h followed by the annexin V staining/flow cytometry to assay apoptosis (A) and Western blotting to detect the indicated proteins (B). Data in A are means ± SDs of duplicate determinations. C, PC-9/AR cells were exposed to DMSO, 200 nM osimertinib, 1 μM CYD-2-11 and the combination of osimertinib and CYD-2-11 for 16 h. Cytosolic fractions were then prepared followed by Western blotting to detect the indicated proteins. D, The tested cell lines were exposed to DMSO, 200 nM osimertinib, 1 μM (PC-9/AR) or 2 μM (HCC827/AR) CYD-2-11 and the combination of osimertinib and CYD-2-11 for varied times as indicated. Mitochondrial fractions were prepared and crosslinked followed by Western blotting for detection of Bax.

Osimertinib combined with Mcl-1 inhibition and Bax activation causes lethality of osimertinib-resistant cells.

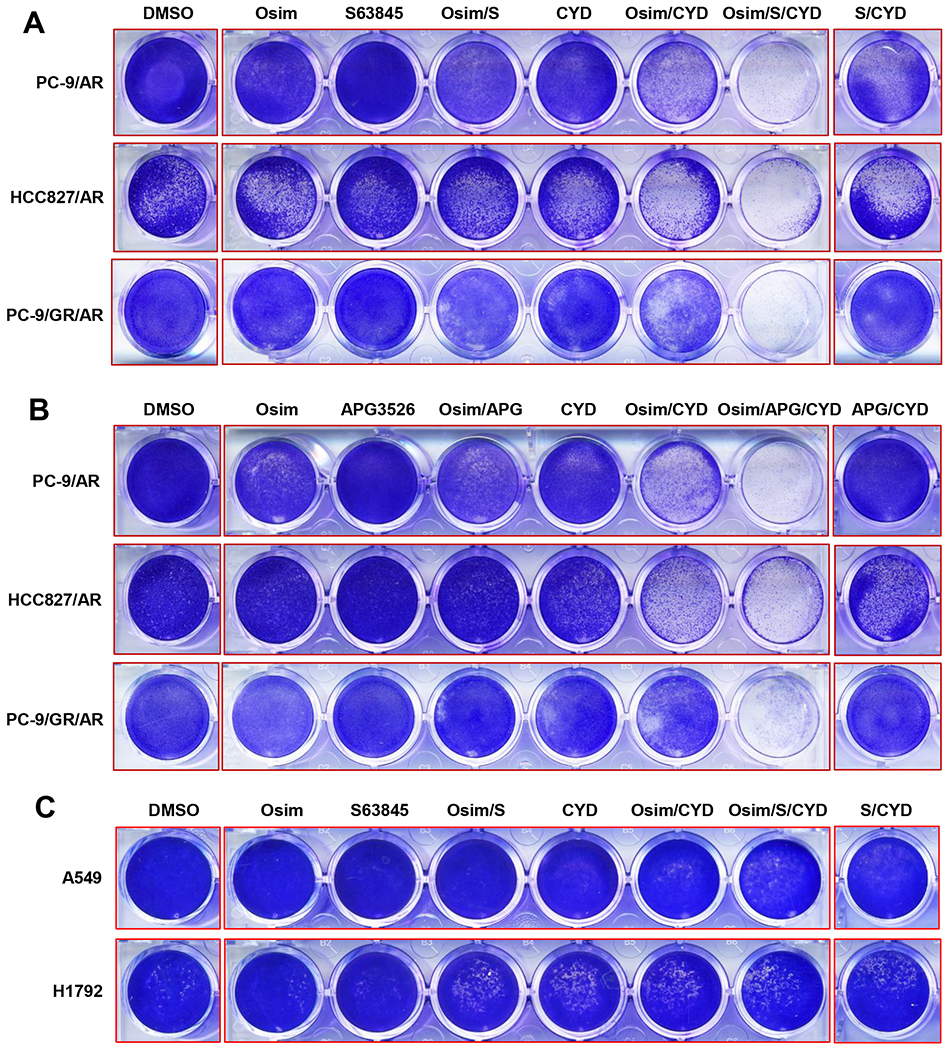

Based on the results derived from our two-drug combination treatments, we speculated that the combination of osimertinib with a Mcl-1 inhibitor and a Bax activator simultaneously should also be promising in terms of enhancing activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway. Therefore, we tested the effects of three-drug combinations (i.e., osimertinib/S63845/CYD-2-11 and osimertinib/APG3526/CYD-2-11) using the Mcl-1 inhibitor and CYD-2-11 at much lower concentrations than were used in the above two-drug combinations. In addition to certain effects observed from two-drug combinations, the three-drug treatments (i.e., osimertinib/S63845/CYD-2-11 and osimertinib/APG3526/CYD-2-11) remarkably eliminated the vast majority of osimertinib-resistant cells, in PC-9/AR, PC-9/GR/AR and HCC827/AR cell lines (Fig. 5A and B). Time-course analysis showed that the apparent effect of the triple-combination on suppressing the growth of the tested cell lines was observed at 48 h post treatment and became very clear at 72 h and 96 h (Fig. S6A). Unfortunately, the triple-combination was not very effective in PC-9/3M cells albeit with some weak effects (Fig. S6B).

Fig. 5. The three-drug combination of osimertinib, CYD-2-11 and an Mcl-1 inhibitor is lethal to osimertinib-resistant EGFRm NSCLC cell lines (A and B), but not to NSCLC cell lines with wild-type EGFR (C).

The tested cell lines in 24-well plates were exposed to DMSO, 200 nM osimertinib (Osim), 600 nM CYD-2-11 (CYD), 3 μM S63845 (S), 2 μM APG3526 (APG) or the indicated combinations. After 96 h, the cells were fixed and stained. Representative staining from triplicate wells in each treatment is shown.

To examine the toxicity of the triple-combination regimen, we examined the effects of osimertinib/S63845/CYD-2-11 combination on the growth of A549 and H1792 cell lines, both of which harbor wild-type EGFR, and found that both two-drug and three-drug combinations did not cause enhanced growth inhibition in these cell lines (Fig. 5C). Therefore, the three-drug combination did not affect the growth of NSCLC cells with wild-type EGFR. We also conducted a similar experiment by replacing osimertinib with erlotinib and generated similar results: the triple-combination of erlotinib/S63845/CYD-2-11 enhanced the effect on suppressing the growth of PC-9/AR cells, but did not do so in A549 and H1792 cells (Fig. S7). Collectively, these results suggest that the triple-combination regimen is preferentially lethal to osimertinib-resistant cells with mutant EGFR.

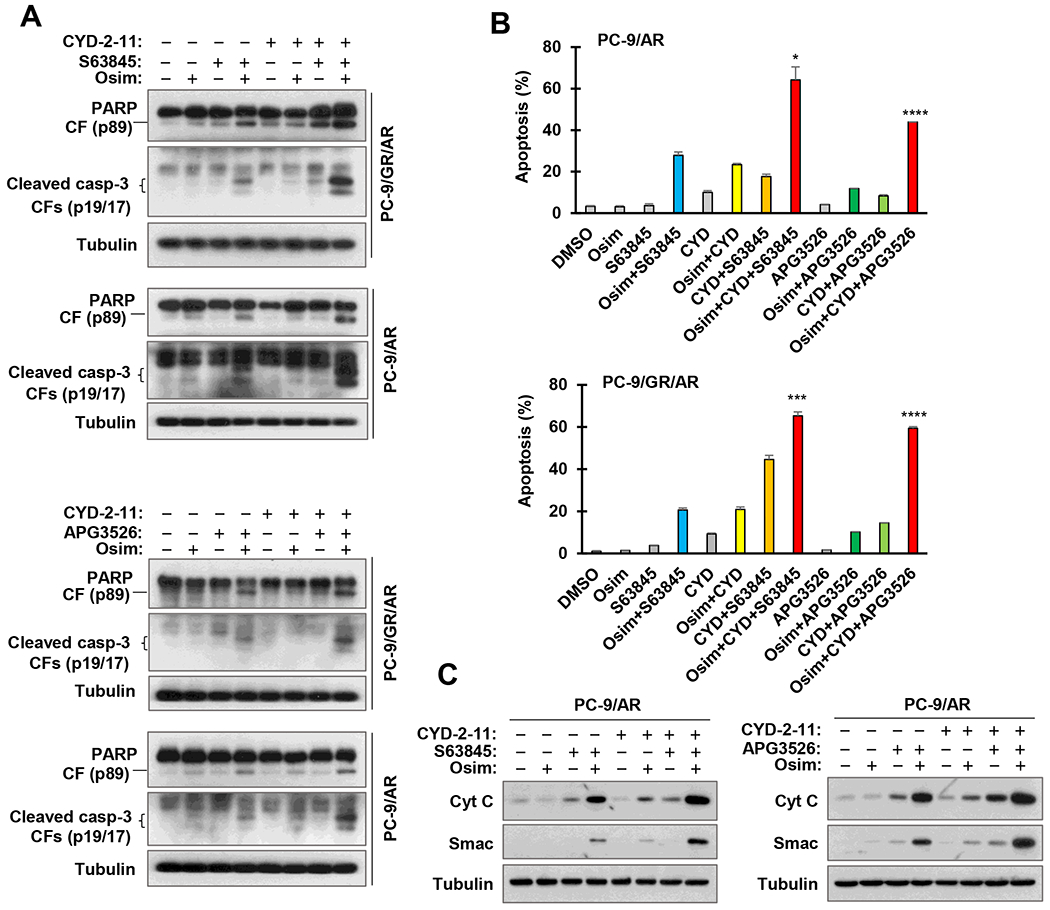

We next determined the effects of the triple-combination regimens on induction of apoptosis in osimertinib-resistant cell lines. In comparison with two-drug combinations, the triple-combination of osimertinib with CYD-2-11 plus S63845 or APG3526 exerted the most potent effects on increasing the levels of cleaved PARP and caspase-3 (Fig. 6A) and annexin V-positive cell populations (Fig. 6B) in both PC-9/AR and PC-9/GR/AR cells. In agreement, these three-drug treatments also resulted in the most potent induction of mitochondrial release of Cyt C and Smac into the cytosol in osimertinib-resistant cells compared with other treatment groups (Fig. 6C). It appears that the combination of osimertinib with Mcl-1 inhibition and Bax activation augments the activation of intrinsic apoptosis in osimertinib-resistant cells.

Fig. 6. The three-drug combination of osimertinib, CYD-2-11 and an Mcl-1 inhibitor is more effective than either two-drug combination in inducing apoptosis (A and B) including mitochondrial release of Cyt C and Smac (C) in osimertinib-resistant NSCLC cells.

A and B, The tested cell lines were exposed to DMSO, 200 nM osimertinib (Osim), 600 nM CYD-2-11 (CYD), 2 μM S63845 or APG3526 and the indicated combinations. After 24 h (A) or 48 h (B), the cells were harvested for detection of the indicated proteins with Western blotting (A) and apoptosis with annexin V stainig/flow cytometry (B). Data presented in B are means ± SDs of duplicate determinations. *, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; and ****, P < 0.0001 at least compared with either of the two-drug combinations. C, PC-9/AR cells were exposed to DMSO, 200 nM osimertinib, 2 μM S63845 or APG3526 and the indicated combinations for 24 h. Cytosolic fractions were prepared and used for detection of the given proteins using Western blotting.

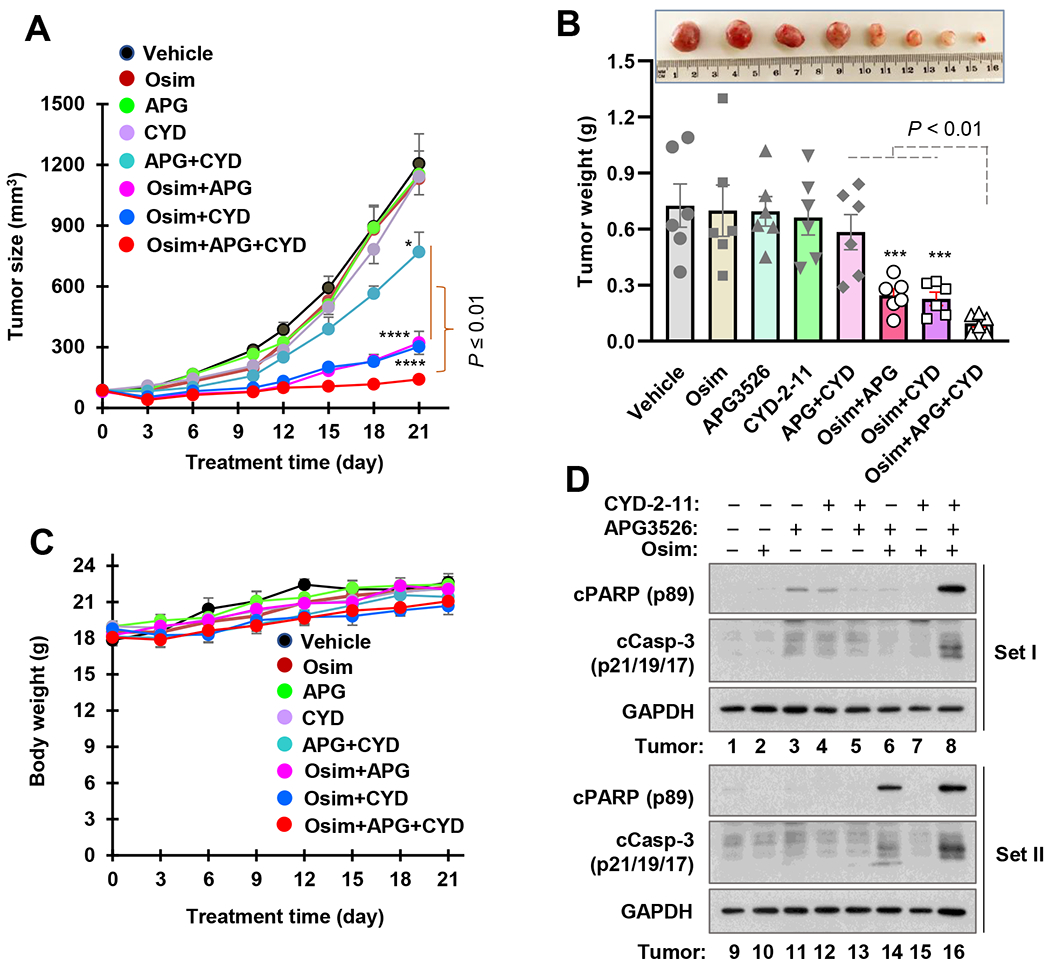

Osimertinib combined with Mcl-1 inhibition, Bax activation or both augments therapeutic efficacy against osimertinib-resistant tumors in vivo.

Following these promising in vitro findings, we then conducted in vivo studies to assess the therapeutic efficacy of the triple-combination in comparison with the two-drug combinations using PC-9/AR xenografts in nude mice. Consistent with the effects in vitro, tumor growth was significantly suppressed when osimertinib was combined with either APG3526 or CYD-2-11, whereas each single agent had limited or no inhibitory effect on the growth of PC-9/AR tumors. However, osimertinib in combination with both CYD-2-11 and APG3526 showed the greatest efficacy against the growth of PC-9/AR tumors, which were significantly smaller than those treated with osimertinib combined with either CYD-2-11 or APG3526 in terms of both tumor volume and weight (Fig. 7A and B). Under the tested conditions, mouse body weights in both two-drug and three-drug combination groups were not significantly reduced compared with vehicle control or single agent groups (Fig. 7C), indicating the safety or tolerability of these combination regimens. Furthermore, we also detected cleaved PARP and capase-3 in resected tumors selected randomly from two mice in each group. As shown in Fig. 7D, levels of both cleaved PARP and caspase 3 were clearly highest primarily in tumors receiving the three-drug combination treatment, but were low or absent in other treatment groups, suggesting enhanced induction of apoptosis in vivo by the triple combination treatment.

Fig. 7. The combination of osimertinib with an Mcl-1 inhibitor, a Bax activator, or particularly with both, exerts enhanced effects against the growth of osimertinib-resistant xenografts in nude mice (A and B) and on induction of apoptosis (D) without enhancing toxicity (C).

Mice carrying PC-9/AR xenografts (n = 6) were treated with the indicated agents either alone or in combination as detailed in “Materials and Methods”. Tumor sizes and mouse body weights were recorded every 3 days (A and B) . Tumor weights were recorded at the end of treatment after sacrificing the mice (C). Tumors in set I and set II (D) were composed of different tumors from each group.

Discussion

Apoptosis is known to be a major form of cancer cell death during cancer therapy 16–18. Accordingly, targeting the induction of apoptosis has long been considered to be a promosing cancer therapeutic strategy 19–23. In this regard, agents that target Bcl-2 family members such as Bcl-1, Mcl-1 and Bax have been actively developed, some of which have been approved or evaluated in clinical trials for the potential treatment of cancer 9, 24. The current study aimed to restore the sensitivity of EGFRm NSCLC cells with acquired resistance to osimertinib in order to achieve the goal of overcoming osimertinib acquired resistance by directly targeting activation of the intrisic apoptotic pathway through Mcl-1 inhibition, Bax activation or both. Our results show that the combination of osimertinib with an Mcl-1 inhibitor or Bax activator synergistically decreased the survival of different osimertinib-resistant cell lines through augmenting the induction of mitochondrial Cyt C and Smac release and apoptosis. Moreover, the triple-combination of osimertinib with Mcl-1 inhibition and Bax activation resulted in an even greater decrease in cell survival and increase in apoptosis, including mitochondrial release of Cyt C and Smac, than caused by either two-drug combination in osimertinib-resistant cells. These effects were confirmed in in vivo xenograft tumor models. Hence, the current study provides convincing preclinical evidence in support of targeting apoptosis using Bcl-2 family-targeting agents as a potential strategy for overcoming acquired resistance to osimertinib. The potential limitation of this strategy is its weak activivty against osimertinib resistant cells carrying the EGFR C797S mutation given that these combinations exerted only limited effects in decreasing the survival of PC-9/3M cells. Fortunately, the C797S mutation rate is low (< 5%) in resistant cases post first-line treatment with osimertinib 7.

In this study, we also tested the efficacy of almonertinib, another 3rd generation EGFR-TKI that is approved for use in China, against the growth of NSCLC cell lines including those with acquired resistance to osimertinib, in comparison with osimertinib. Both agents effectively decreased the survival of EGFRm NSCLC cells with weak activities against NSCLC cell lines with wild-type EGFR. Moreover, all tested osimertinib-resistant EGFRm NSCLC cell lines showed cross-resistance to almonertinib, indicating that both drugs share the same target specificity. Consistently, the combination of almonertinib with Mcl-1 inhibition or Bax activation also enhanced killing effects against osimertinib-resistant cell lines. Therefore, targeting apoptosis using Bcl-2 family-targeting agents should also be a potential strategy for overcoming acquired resistance to almonertinib and other similar third generation EGFR-TKIs.

While maintaining enhanced apoptosis-inducing activity in different osimertinib-resistant cell lines, the concentrations of both Mcl-1 inhibitors and Bax activator in the triple-combination were sub-optimal and even lower than those used in two-drug combinations. Importantly, both two-drug and three-drug combinations tested in this study were ineffective in decreasing the survival of human NSCLC cell lines with wild-type EGFR. Given the unique profiles of osimertinib and almonertinib as EGFR mutation-selective TKIs, it is plausible that targeting the activation of intrinsic apoptosis with Mcl-1 inhibiton, Bax activation or both primarily restores the response of osimertinib-resistant EGFRm NSCLC cell lines or tumors to osimertinib or almonertinib. We can also reasonably propose that these combinations will have minimal or no toxicity to normal cells or tissues that lack mutant EGFR. Indeed, these combinations, while showing enhanced effects against the growth of osimertinib-resistant tumors in mice, did not significantly reduce the body weights of mice, suggesting their favorable tolerability in vivo. Interestingly, even erlotinib, when combined with the tested Mcl-1 inhibitor and Bax activatior, also potently enhanced the effect of decreasing the survival of osimertinib resistant cells, while exerting limited effects against other NSCLC cells with WT EGFR, suggesting a preferential effect against osimertinib-resistant EGFRm NSCLC cells. It is possible that erlotinib at the tested concentration or condition still preferentially binds to and inhibits mutated EGFR. Nonetheless, our results presented in this study warrant the future evaluation of these combination strategies in the clinic.

The development of acquired resistance to osimertinib or other 3rd generation EGFR-TKIs is largely due to the inability of the therapy to eliminate all cancer cells, leading to the expansion of surviving cells into resistant populations after acquisition of additional resistance features (e.g., resistance target mutations). Therefore, aiming to eliminate resistant cancer cells through targeting the activation of cell death mechanisms such as apoptosis offers an effective way to treat EGFRm NSCLC in order to achive long-term remission. We believe that eliminating intrinsically resistant cell clones existing in the sensitive EGFRm cell population during the initial treatment (e.g., with osimertinib) is a logical and effective strategy to avoid or delay the emergence of acquired resistance to osimertinib and other 3rd generation EGFR-TKIs. This can be achieved by targeting the activation of apoptotic pathways, e.g., with the strategy explored in this study using Bcl-1 family-targeting agents. In this way, we may expect a long-term remission of patients with EGFRm NSCLC after targeted therapy with osimertinib or other third generation EGFR-TKI. Effort in this direction is underway in the lab.

In summary, the current study has provided strong preclinical support for a logical and effective therapeutic strategy to overcome acquired resistance to osimertinib and other 3rd generation EGFR-TKIs by targeting activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway through Mcl-1 inhibition, Bax activation or both. Future clinical validation of this strategy is thus warranted.

Materials and methods

Reagents.

Osimertinib and erlotinib were the same as previously described 10. Almonertinib was purchased from Advanced ChemBlocks Inc (Burlingame, CA). S63845 (MIK665) and AZD5991 were purchased from Selleckchem (Houston, TX). APG3526 was provided by Ascentage Pharm (Rockville, MD). CYD-2-11 was developed in house by Dr. Xingming Deng’s group as described previously 13, 14. Digitonin and bismaleimidohexane (BMH) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and ThermoFischer Scientific (Waltham, MA), respectively. Antibody against Cyt C (sc-13156) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, Texas). Smac/Diablo antibody (#15108) was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). The remaining antibodies used in this study were described previously 10, 25.

Cell lines and cell culture.

The osimertinib-resistant cell-lines, PC-9/AR, PC-9/GR/AR, PC-9/3M and HCC827/AR, other lung cancer cell lines and their culture conditions were the same as described previously 10, 15, 25. These cell lines have not been authenticated recently.

Cell survival and apoptosis assays.

Cells were seeded into 96-well plates followed by treatment with the tested agents within 24 h. Cell numbers were estimated after 72 h with sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay as described previously 26. CI calculations for drug interaction were conducted using CompuSyn software (ComboSyn, Inc; Paramus, NJ). Flow cytometry-based apoptotic assay was performed with an annexin V/7-AAD kit purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The cleavage of PARP and caspase-3 as an additional indicator of apoptosis was detected using Western blotting.

Western blot analysis.

The preparation of whole-cell protein lysates and the procedures for Western blotting were the same as previously described 10, 25.

Mcl-1 knockdown with siRNA.

The control and Mcl-1 siRNAs and transfection were essentially the same as described in our previous study 27.

Cyt C and Smac release assay.

Cells were collected and re-suspended with cold PBS 3 times. Then, the cytosolic proteins were released from mitochondria in the cells by merging the pellets into digitonin-based hypotonic lysis buffer (20 nM HEPES/KOH, pH 7.4, 100 nM sucrose, 50 mM KCL, 0.025% digitonin and 1% protease inhibitor) for 5 min as described in a previous study 28. After centrifugation of the lysates at 13,000 g for 5 min, supernatants and pellets (membrane fraction) were collected and subjected to Western blotting for detection of Cyt C and Smac.

Mitochondrial isolation and Bax oligomerization assay.

The membrane fractions collected after final centrifugation as described in the above Cyt C and Smac release assay were incubated in BMH-based crosslinking buffer (20 mM HEPES/KOH, pH 7.0, 100 mM sucrose, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl and 0.5 mM BMH) for 60 min at room temperature 13. Thereafter, the samples with loading buffer were boiled for 5 min before being loaded onto SDS-PAGE gels for detection of oligomerized Bax using Western blotting.

Colony formation assays.

Cells were seeded in 12-well cell culture plates, incubated overnight, and then exposed to different agents with three replicate wells for each treatment. Cell colonies were stained with crystal violet as described previously 10, 25 at the end of treatment.

Animal xenograft and treatments.

Animal studies were conducted with approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Emory University as we did previously 10, 25. Nude mice bearing PC-9/AR xenografts were divided randomly into 8 groups for the following treatments: vehicle control (10% DMSO, 40% PEG300, 5% tween 80 and 45% saline; og and ip, daily), osimertinib (10 mg/kg, og, daily), APG3526 (10 mg/kg, og, daily), CYD-2-11 (20 mg/kg, ip, daily), the respective two-drug concurrent combinations, and the three-drug concurrent combination. Caliper measurements were used to quantify tumor volumes (V) with the formula V= π (length × width2)/6) every three days. Mouse body weights were also recorded every three days. At the endpoint of the study, the mice were weighed and euthanized with CO2 asphyxia. Subsequently, the tumors were resected, weighed and stored in liquid nitrogen.

Statistical analysis.

Two-sided unpaired Student’s t-tests were applied to analyze significant differences between two groups. One-way ANOVA tests were conducted to value differences among multiple groups using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Results were considered statistically significant when P values were less than 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. A. Hammond in our department for editing the manuscript.

This work was supported by Emory University Winship Cancer Institute lung cancer pilot fund (to SYS), NIH/NCI SPORE P50 CA217691 (to XD) and a research fund from Ascentage Pharma (to SYS).

TKO, SSR and SYS are Georgia Research Alliance Distinguished Cancer Scientists.

Competing interest statement

TKO is on consulting/advisory board for Novartis, Celgene, Lilly, Sandoz, Abbvie, Eisai, Takeda, Bristol-Myers Squibb, MedImmune, Amgen, AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim. SSR is on consulting/advisory board for AstraZeneca, BMS, Merck, Roche, Tesaro and Amgen. YZ and DF are full-time employees and equity shareholders of Ascentage Pharma. SYS received a research fund from Ascentage Pharma. Other authors disclose that they have no potential conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations:

- NSCLC

non-small cell lung cancer

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- EGFRm

EGFR mutant

- EGFR-TKIs

EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors

- Cyt C

cytochrome C

- SRB

sulforhodamine B

- CI

combination index

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians; 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shah R, Lester JF. Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors for the Treatment of EGFR Mutation-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Clash of the Generations. Clinical lung cancer 2020; 21: e216–e228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carlisle JW, Ramalingam SS. Role of osimertinib in the treatment of EGFR-mutation positive non-small-cell lung cancer. Future oncology 2019; 15: 805–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piper-Vallillo AJ, Sequist LV, Piotrowska Z. Emerging Treatment Paradigms for EGFR-Mutant Lung Cancers Progressing on Osimertinib: A Review. J Clin Oncol 2020: JCO1903123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramalingam SS, Vansteenkiste J, Planchard D, Cho BC, Gray JE, Ohe Y et al. Overall Survival with Osimertinib in Untreated, EGFR-Mutated Advanced NSCLC. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soria JC, Ohe Y, Vansteenkiste J, Reungwetwattana T, Chewaskulyong B, Lee KH et al. Osimertinib in Untreated EGFR-Mutated Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leonetti A, Sharma S, Minari R, Perego P, Giovannetti E, Tiseo M. Resistance mechanisms to osimertinib in EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer 2019; 121: 725–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Negi A, Murphy PV. Development of Mcl-1 inhibitors for cancer therapy. European journal of medicinal chemistry 2021; 210: 113038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang H, Guo M, Wei H, Chen Y. Targeting MCL-1 in cancer: current status and perspectives. J Hematol Oncol 2021; 14: 67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shi P, Oh YT, Deng L, Zhang G, Qian G, Zhang S et al. Overcoming Acquired Resistance to AZD9291, A Third-Generation EGFR Inhibitor, through Modulation of MEK/ERK-Dependent Bim and Mcl-1 Degradation. Clin Cancer Res 2017; 23: 6567–6579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walensky LD. Targeting BAX to drug death directly. Nat Chem Biol 2019; 15: 657–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pogmore JP, Uehling D, Andrews DW. Pharmacological Targeting of Executioner Proteins: Controlling Life and Death. J Med Chem 2021; 64: 5276–5290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xin M, Li R, Xie M, Park D, Owonikoko TK, Sica GL et al. Small-molecule Bax agonists for cancer therapy. Nature communications 2014; 5: 4935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li R, Ding C, Zhang J, Xie M, Park D, Ding Y et al. Modulation of Bax and mTOR for Cancer Therapeutics. Cancer Res 2017; 77: 3001–3012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zang H, Qian G, Zong D, Fan S, Owonikoko TK, Ramalingam SS et al. Overcoming acquired resistance of epidermal growth factor receptor-mutant non-small cell lung cancer cells to osimertinib by combining osimertinib with the histone deacetylase inhibitor panobinostat (LBH589). Cancer 2020; 126: 2024–2033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cotter TG. Apoptosis and cancer: the genesis of a research field. Nat Rev Cancer 2009; 9: 501–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fesik SW. Promoting apoptosis as a strategy for cancer drug discovery. Nat Rev Cancer 2005; 5: 876–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zimmermann KC, Green DR. How cells die: apoptosis pathways. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001; 108: S99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fulda S Apoptosis pathways and their therapeutic exploitation in pancreatic cancer. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine 2009; 13: 1221–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Penn LZ. Apoptosis modulators as cancer therapeutics. Curr Opin Investig Drugs 2001; 2: 684–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rowinsky EK. Targeted induction of apoptosis in cancer management: the emerging role of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptor activating agents. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 9394–9407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schulze-Bergkamen H, Krammer PH. Apoptosis in cancer--implications for therapy. Semin Oncol 2004; 31: 90–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun SY, Hail N Jr., Lotan R. Apoptosis as a novel target for cancer chemoprevention. J Natl Cancer Inst 2004; 96: 662–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang L, Lu Z, Zhao X. Targeting Bcl-2 for cancer therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 2021; 1876: 188569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shi P, Oh YT, Zhang G, Yao W, Yue P, Li Y et al. Met gene amplification and protein hyperactivation is a mechanism of resistance to both first and third generation EGFR inhibitors in lung cancer treatment. Cancer Lett 2016; 380: 494–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun SY, Yue P, Dawson MI, Shroot B, Michel S, Lamph WW et al. Differential effects of synthetic nuclear retinoid receptor-selective retinoids on the growth of human non-small cell lung carcinoma cells. Cancer Res 1997; 57: 4931–4939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zong D, Gu J, Cavalcante GC, Yao W, Zhang G, Wang S et al. BRD4 levels determine the response of human lung cancer cells to BET degraders that potently induce apoptosis through suppression of Mcl-1. Cancer Res 2020; 80: 2380–2393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hasenjager A, Gillissen B, Muller A, Normand G, Hemmati PG, Schuler M et al. Smac induces cytochrome c release and apoptosis independently from Bax/Bcl-x(L) in a strictly caspase-3-dependent manner in human carcinoma cells. Oncogene 2004; 23: 4523–4535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.