Abstract

Information release is an important way for governments to deal with public health emergencies, and plays an irreplaceable role in promoting epidemic prevention and control, enhancing public awareness of the epidemic situation and mobilizing social resources. Focusing on the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic in China, this investigation chose 133 information release accounts of the Chinese government and relevant departments at the national, provincial, and municipal levels, including Ministries of the State Council, Departments of Hubei Province Government, and Bureaus of Wuhan Government, covering their portals, apps, Weibos, and WeChats. Then, the characteristics such as scale, agility, frequency, originality, and impact of different levels, departments, and channels of the information releases by the Chinese government on the COVID-19 epidemic were analyzed. Finally, the overall situation was concluded by radar map analysis. It was found that the information release on the COVID-19 epidemic was coordinated effectively at different levels, departments, and channels, as evidenced by the complementarity between channels, the synergy between the national and local governments, and the coordination between departments, which guaranteed the rapid success of the epidemic prevention and control process in China. This investigation could be a reference for epidemic prevention and control for governments and international organizations, such as the World Health Organization (WHO), during public health emergencies, e.g. the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: COVID-19, information release, public health emergency, Chinese government

1. Introduction

Since 2000, there have been six major international public health emergencies (Zhang, Zhao, Huang, & Glanzel, 2020). Among these emergencies, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has brought challenges bigger than ever. According to worldometers.info, as of April 23, 2020, 2.6 million confirmed COVID-19 cases have been reported globally in 212 countries and regions (Worldmeters, 2020). It has become the most serious natural and human disaster since the Second World War. For the first time, many countries have taken measures to maintain or limit social distance. As one of these symbolic measures, Wuhan, the largest city in Central China, imposed a historic 76-day travel restriction on the city to seal the city with a population of 10 million so as to stop the spread of virus. As one of 212 countries to report the COVID-19 epidemic outbreak, China has achieved a rapid and amazing success on COVID-19 epidemic prevention. Extracted from a continuous record of important events during the COVID-19 epidemic in China maintained by the Southern Metropolis Daily (Southern Metropolis Daily, 2020), the key events of the COVID-19 epidemic prevention in China from the perspective of government information release are listed in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Key Events of COVID-19 Epidemic Prevention in China

| Date | Key event |

|---|---|

| December 27, 2019 | 4 suspicious cases were reported at the Wuhan Center for Disease Control & Prevention (WHCDCP) |

| December 29, 2019 | Health Commission of Hubei Province (HCHB) and Wuhan Municipal Health Commission (WHMHC) started several epidemiological investigations |

| January 8, 2020 | Novel coronavirus (later named as COVID-19 by the World Health Organization) was confirmed as the pathogen of the epidemic by the National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China (NHCC) |

| January 15, 2020 | The novel coronavirus pneumonia diagnosis and treatment plan (trial version 1) was released by NHCC |

| January 20, 2020 | NHCC released its 1st announcement that COVID-19 was included under Class B of infectious diseases in the Infectious Disease Prevention Act of P R China, and the prevention measures of Class A infectious diseases were adopted |

| January 22, 2020 | The People's Government of Hubei Province (GOV.HUBEI) initiated emergency response to public health emergencies |

| January 23, 2020 | The Government of Wuhan (GOV.WUHAN) released its 1st announcement, which imposed a travel restriction on the city. A total of 830 confirmed cases of COVID-19 were reported in China, including 549 in Hubei Province and 495 in Wuhan (NHCC) |

| January 25, 2020 | The State Council, the People's Republic of China (GOV.CN) set up a leading group to deal with the epidemic situation in China |

| February 2, 2020 | GOV.HUBEI announced segregation of all suspected patients; 2829 newly confirmed cases in China on this day, including 2103 in Hubei Province (NHCC) |

| March 2, 2020 | NHCC announced that the rapid rise of COVID-19 epidemic in China was under control; 125 newly confirmed cases in China on this day, including 114 in Hubei Province (NHCC) |

| March 11, 2020 | GOV.HUBEI announced the reopening of Hubei Province; 15 newly confirmed cases in China on this day, including 8 in Hubei Province (NHCC) |

| March 31, 2020 | NHCC announced that the spread of COVID-19 epidemic in China was basically blocked; 35 newly imported cases and 1 native case on this day (NHCC) |

| April 8, 2020 | GOV.HUBEI removed all travel restrictions on Wuhan; a total of 81865 confirmed cases were reported in China (NHCC) |

Although China has achieved rapid success in COVID-19 epidemic prevention, most countries and regions are still struggling with the COVID-19 pandemic. In this process, China has carried out timely cooperation with WHO and other countries around the world, and the WHO Health Emergencies Program and its networks such as the Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network (GOARN) and the Public Health Emergency Operations Centre Network (EOC-NET) provided the basic platforms for cooperation. The iconic announcements of WHO include the following:

-

–

January 5, 2020 – reporting the recent cases of pneumonia of unknown cause in Wuhan, China;

-

–

January 31, 2020 – declaring the COVID-19 epidemic outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC);

-

–

February 24, 2020 – announcing that the COVID-19 epidemic in China has passed its peak; and

-

–

March 12, 2020 – declaring the COVID-19 epidemic a pandemic.

While actively cooperating with WHO, China is also committed to promoting the rapid development of direct cooperation among countries. Till March 20, 2020, the Chinese government has announced assistance to 82 countries and international organizations. The G20 virtual summit on COVID-19 held on March 26, 2020, shows that active international cooperation against the COVID-19 pandemic has become a popular international viewpoint. This requires governments to give full play to their leading role in epidemic prevention and control. Accordingly, it is urgent for governments to give full play to their leading role in the prevention and control of the COVID-19 pandemic.

More importantly, during the COVID-19 pandemic, prominent “infodemic” phenomena were constantly observed. Infodemic means that too much information (some accurate and some not) makes it difficult for people to find trustworthy information sources and reliable guidance, which may even cause harm to people's health (WHO, 2020). Typical infodemic in the COVID-19 pandemic includes the following: many people on social media think that “healthy people don’t need to wear masks” or “the mask can be sterilized by boiling or spraying alcohol”; and the recent rumor that “5G causes COVID-19” (Andy, 2020). Therefore, it is vital to ensure that authoritative and correct information fills the information vacuum in the period of the COVID-19 pandemic. Hence, the Director of WHO, General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, said that right information is the best protection against COVID-19 (Xinhuanet.com, 2020) and launched a new platform – the WHO Information Network for Epidemics (EPI-WIN) – to overcome the infodemic on COVID-19 (Zarocostas, 2020). The Chinese government also announced “to release authoritative information in a multilevel and high-density manner, respond to the concerns of the people, enhance timeliness, pertinence and professionalism, guide the people to increase confidence and firm confidence” (Xi, 2020).

Particularly, it is a big challenge for different levels and different departments of the government to collaborate and release authoritative information in a high-density manner. First, COVID-19 is caused by a new and cunning virus, which is difficult to identify and diagnose effectively in the clinic, and the disease is characterized by strong infectivity and high death rate (Huang et al., 2020). Furthermore, in big cities, the disaster caused by the COVID-19 epidemic may lead to a series of secondary and derivative disasters (Li, Lu, Jin, & Li, 2020), which poses a big challenge to the coordination of multiple government departments and their ability to respond. Fortunately for China, the good performance of the Chinese government's multilevel and multidepartment information release has played a key role in the rapid control of the COVID-19 epidemic in China. In recent years, China's government information release has made great progress. The Regulation of the People's Republic of China on the Release of Government Information came into force in 2008 (The State Council, the People's Republic of China, 2020), which has greatly promoted the authoritative information release of governments at all levels and all departments, and in turn, this has cultivated in Chinese people the habit of using authoritative information to resist the infodemic. Furthermore, the wide application of apps, as well as services such as Weibo (a Twitter-like service in China) and WeChat (a Facebook-like service in China), which promote and facilitate access and interaction in e-government (Weerakkody, Elhaddadeh, Alsobhi, Shareef, & Dwivedi, 2013), have greatly expanded the channels of government information release. To some extent, the ideal government information release has been the key to the rapid success of China's COVID-19 epidemic prevention, compared with most countries in the world still fighting domestic COVID-19 epidemic.

In order to provide the government information release experience of China to WHO and other governments for reference, this investigation aims to systematically analyze the information release strategy of the Chinese government and relevant departments at the national, provincial, and municipal levels, including Ministries of the State Council, Departments of Hubei Province Government, and Bureaus of Wuhan Government, covering their portals, apps, Weibos, and WeChats, so as to reveal the panorama of different levels, departments, and channels of information release on COVID-19 epidemic considering the five characteristics of scale, agility, frequency, originality, and impact of information release.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Information Release

With the advent of informatization, the network communication channels that people can use have become real time and diversified. Online information release is becoming increasingly popular. Usually, the information releasing agent is the government, an enterprise, or an individual. Personal information release mainly focuses on online public opinion (Sun et al., 2018), while enterprise information release focuses on corporate management (Qian, & Anderson, 2020). But online information release is especially important for governments to respond to public emergencies. On the one hand, government information release can deepen international cooperation and international data sharing (Abella, Ortiz-De-Urbina-Criado, & De-Pablos-Heredero, 2019). On the other hand, government information release can increase government control and improve capability to respond to public emergencies (Jha et al., 2018).

To a great extent, information channels determine the speed and effectiveness of dissemination of the released information. Common information release channels considered in the study include portals, social media, and apps. The portal is a much-authoritative channel for information release. Usually, virus-related information in a pandemic is released through the portals (Zhao et al., 2020). Next, with the popularity of social media, channels such as Twitter, Weibo, and WeChat – with massive number of users – have become key channels for information release. Zhang, Sheu and Zhang (2018) studied how five major library and information science (LIS) professional organizations in the United States use Twitter to release information for interaction. Kim, Lee, Shin and Yang (2017) studied the impact of travel information on the decisions made by users and marketers released on Weibo. Wang et al. (2020) studied the applicability of WeChat Official Account to release health information, but there were still problems identified, such as difficulty in tracing information sources and poor information quality. In the case of the apps, existing applications are generally based on interactive functions; therefore, researchers mainly focus on information services of apps (Hsu et al., 2016), but few have investigated information release.

To analyze the characteristics of information release, scholars mainly focus on its timeliness, influence, and release frequency (Gilmour, Miyagawa, Kasuga, & Shibuya, 2016; Savoia, Lin, & Viswanath, 2017). Especially, in public emergencies, studies show that early information release can serve as an early warning. In the 2015–2016 Latin American Zika virus outbreak, McGough, Brownstein, Hawkins and Santillana (2017) used information released by Google searches, Twitter microblogs, and the HealthMap digital surveillance system to track and predict suspected cases 3 weeks before the official case data were released and thereby produced predictions of weekly suspected cases for five countries. Meanwhile, information release is for the public, and its influence varies according to the release channel, time, and content. During public emergencies, social media such as Weibo and WeChat provide information sharing and real-time updating within a large population, so the government should make better use of social media to release real and authoritative information in a timely manner to positively influence public opinion (Ruiu, 2020; Yu, Li, & Tang, 2017). In addition, some scholars have studied the frequency, scale, and originality of information release on Weibo during emergencies (Zhou, Li, & Huang, 2015; Zhang, & Wang, 2015) and identified its advantages (content neutrality and originality, stage-adaptive release frequency) and disadvantages (imbalance of response speed and information volume). Fu et al. (2016) also researched the frequency of tweets related to the Zika virus in English and Spanish since 2016 to explore public responses.

On the whole, there have been many studies on information release, and with the rise of social media, the channels for information release are diverse; at the same time, the government has strengthened e-government service in social media. In terms of the characteristic scale, the timeliness, influence, and frequency of information release can reflect the situation of public emergencies and enable the public and the government to carry out effective response measures. However, few studies have conducted a comprehensive analysis of the scale, time, frequency, originality, and influence of information release.

2.2. Government Information Release in Public Emergencies

The spread of infodemic causes great harm to the society. Especially in public health emergencies, a large amount of disordered and distorted information has exacerbated people's panic and even affected people's health. Therefore, it is very important to study government information release in public emergencies. The release of authoritative government information can alleviate public opinion and improve government credibility (Miller, 2016). It can also regulate the negative emotions of people (Zhang, Wang, & Zhu, 2019; Sun et al., 2018) and help them actively and effectively respond to the harm caused by emergencies.

In existing research works on government information release channels for public emergencies, social media such as Weibo and Twitter accounted for the major portion. Fu et al. (2016) studied the information about the Zika virus released on Twitter and reported the trend of virus information on Twitter based on content analysis. Li, Liu and Li (2020) conducted empirical research on information about 101 major Chinese public emergencies released on Weibo from 2010 to 2017, indicating that if netizens trust the government and the media, they were more likely to make cooperative decisions. Some researchers focused on the design of apps for responding to public emergencies (Pereira, Estevez, & Fillottrani, 2018; Bassi, Arfin, John, & Jha, 2020). WeChat and portals were rarely researched as government information release channels for public emergencies. But in emergencies, especially public health emergencies, the government releases authoritative information through multiple channels, and there is a lack of research at present to discuss the government information release from the perspective of multichannel complementarity.

In public emergencies, the governments at all levels need to coordinate and cooperate to effectively respond to the situation. Taking the United States as an example, during the incident involving the presence of excessive lead concentration in the water supply in Flint, Michigan, Nukpezah (2017) showed that the municipal government sought help from the state government after declaring a state of public health emergency and requested the federal government to authorize the use of resources to supplement the state and local response and restoration work. In other words, while the lower-level government seeks help from the higher-level government, the higher-level government offers necessary support to the lower-level government. For example, in order to effectively cope with the COVID-19 pandemic in China, the national public health management department issued the highest level of emergency response, and the provincial and local governments released information under the guidance of the State Council, organized and coordinated public health treatments, and gathered emergency materials and facilities (Bao, Sun, Meng, Shi, & Lu, 2020). However, research on government information release at multiple levels is insufficient. In public health emergencies, information cooperation at the different levels of a government helps to assess the spread and control the outbreak. Sun, Chen and Viboud (2020) evaluated the trend of the pandemic and the extent of outbreaks across China based on news reports released by Chinese national and local health departments on COVID-19. The information link between the higher-level and the lower-level governments made the tracking and evaluation of the pandemic situation clearer and more effective. But, at present, few scholars have conducted research on the synergy of the information release at multiple levels of a government in a national management system.

In the process of government information release during public emergencies, the coordination role of various departments and agencies is very important, too. For example, during the 2012 Gumi chemical spill in South Korea, Jung and Park (2016) used the webometric approach to collect data and announcements released by various departments and agencies, and the results showed that a lack of interorganization communication of risk and the absence of accurate hazard assessments performed by the principal agencies, such as the Ministry of Environment and the National Emergency Management Agency, led to the subordinate departments failing to respond in terms of hazard operations, population protection, and time management, causing huge harm to residents’ lives. When a public health emergency occurs, the centers for disease control have strong relation with the speed of its spread, and the information they release plays a key role in disease tracking and prediction. For example, considering the Ebola outbreak in 2014, Kott and Limaye (2016) studied the use of news media to release risk-related information by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC); and Crook, Glowacki, Suran, Harris and Bernhardt (2016) studied the conversations released by the US CDC on Twitter to mitigate public panic. However, at present, research on multidepartment information release is not comprehensive, considering that the occurrence of serious public emergencies will surely attract the attention of most departments. Hence, it is necessary to conduct a comprehensive study on the coordination role of information release by related departments in public emergencies.

To sum up, many studies focus on government information release in public emergencies; among these, the research on government information release in public health emergencies often focuses on information released by relevant agencies or departments through a single channel to explore the characteristics of the timeliness, influence, and frequency of government information release. Meanwhile, in emergency crisis management, multilevel government cooperation is very important, but the characteristics of government information release at all levels also need attention. At present, in the context of public health emergencies, few studies have comprehensively studied ① government information release on portals, microblogs of governments, and apps channels and ② information release from the perspective of hierarchical cooperation and departmental coordination. Therefore, this research covers four main channels of government information release and 16 departments related to COVID-19 based on the authoritative documents of the State Council; in addition, the study analyzes the scale, agility, frequency, originality, and impact characteristics of the Chinese government's information release on COVID-19 at three levels, including Ministries of the State Council, Departments of Hubei Province Government, and the Bureaus of Wuhan Government.

3. Research Objects and Data Collection

Government information release refers to the use of various channels, carriers, and media to transmit government information, government work, social services, and other information according to specific government and public needs, so as to give full play to the administrative and service functions of the government, which can effectively guarantee the citizens’ right to know and participate in and discuss politics, in addition to improving the transparency and credibility of government work (Hu, Li, & Tan, 2019). Currently, China's government information release relies heavily on government portals, mobile government affairs clients (such as government apps) (Zhang, Yuan, & Duan, 2019), and microblogs of government (such as government Weibo, government WeChat official account, which is also named as WeChat in this article for convenience) (Feng, Ma, & Jiang, 2019), which rapidly provide government information and government services and have become an effective channel for real-time interaction between the government and the people; so, we choose these three channels for the analysis of government information release.

The authoritative documents on the epidemic situation are generally released on the official portal GOV.CN; so, we collected 39 authoritative documents in its special column on the epidemic situation, “Joint prevention and control mechanism documents of the State Council”, up to March 11, 2020 (The State Council, the People's Republic of China, 2020), and four graduate students manually analyzed the departments involved in these documents. In the process, we found that although the Center for Disease Control & Prevention is just a bureau in the Health Commission department at all levels, it is very important for epidemic prevention and control; furthermore, it has its own information release channels, and so, it would be better to list it separately to better understand the information release of the Chinese government. Finally, 16 government departments and bureaus are mentioned in the 39 authoritative documents, namely, the People's Government, the Health Commission, Civil Affairs, Disease Control and Prevention, Human Resources and Social Security, Transportation, Education, Industry and Information Technology, Agriculture and Rural Affairs, Medical Products, Commerce, Public Security, Finance, Market Regulation, Justice, and Science and Technology. In order to better reflect the government information release in response to the COVID-19 epidemic at all levels of the government, we collected the information release data in the government portals, apps, and Weibos/WeChats about the COVID-19 epidemic of these sixteen departments at three different levels of the Ministries of the State Council, Departments of the Hubei Province Government, and the Bureaus of Wuhan Government.

Further investigation revealed that the Medical Products Administration of Wuhan was merged into the Wuhan Market Regulation Bureau (WHMRB) (Wuhan Municipal Government, 2019); so, a total of 47 government departments are included. Regarding the government apps and government Weibos/WeChats, some departments have not adopted these channels for government information release; so, we finally collected information release data from a total of 47 government departments, as shown in Table 2 , and 133 research objects (Table A1 in Appendix) from different channels. We take one document or information released by a research object as a data record, or a release.

Table A1.

The 133 Research Objects in This Investigation

| Level | Department/portal | App | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| National | 中华人民共和国中央人民政府 | 国务院 | 中国政府网 | 中国政府网 |

| 中华人民共和国国家卫生健康委员会 | 健康中国 | 健康中国 | 健康中国 | |

| 中华人民共和国民政部 | 中华人民共和国民政部 | 民政微语 | 中国民政 | |

| 中国疾病预防控制中心 | / | 疾控科普 | 中国疾控动态 | |

| 中华人民共和国人力资源和社会保障部 | 掌上12333* | / | 人力资源与社会保障部 | |

| 中华人民共和国交通运输部 | 交通运输部 | 中国交通 | 交通运输部 | |

| 中华人民共和国教育部 | 教育部 | 微言教育 | 微言教育 | |

| 中华人民共和国工业和信息化部 | / | 工信微报 | 工信微报 | |

| 中华人民共和国农业农村部 | / | / | / | |

| 国家药品监督管理总局 | 中国药品监督 | 中国药品监督 | 中国药闻 | |

| 中华人民共和国商务部 | 商务部网站# | 商务微新闻 | 商务微新闻 | |

| 中华人民共和国公安部 | 公安110@ | 中国警方在线 | 中国警方在线 | |

| 中华人民共和国财政部 | 财政部 | / | 财政部 | |

| 国家市场监督管理总局 | 登记注册身份验证 @ | 市说新语 | 市说新语 | |

| 中华人民共和国司法部 | 司法部 | 司法部 | 司法部 | |

| 中华人民共和国科学技术部 | / | 锐科技 | 锐科技 | |

| Provincial | 湖北省人民政府 | 湖北省政府# | 湖北发布 | 湖北省人民政府网 |

| 湖北省卫生健康委员会 | / | / | 健康湖北 | |

| 湖北省民政厅 | 鄂汇办# | / | 湖北民政 | |

| 湖北省疾病预防控制中心 | 湖北省疾控中心# | / | 湖北疾控 | |

| 湖北省人力资源和社会保障厅 | / | / | 湖北人社 | |

| 湖北省交通运输厅 | / | / | 湖北交通 | |

| 湖北省教育厅 | / | / | 湖北省教育厅 | |

| 湖北省经济和信息化厅 | / | 湖北省经信厅政务微博 | 湖北省经济和信息化厅 | |

| 湖北省农业农村厅 | 湖北省农业农村厅 * | 湖北省农业农村厅 | 湖北省农业农村厅 | |

| 湖北省药品监督管理局 | / | 湖北药品监管 | 楚天药闻 | |

| 湖北省商务厅 | / | / | 湖北省商务厅 | |

| 湖北省公安厅 | 网上公安局 * | 平安湖北 | 平安湖北 | |

| 湖北省财政厅 | / | 湖北财政 | ||

| 湖北省市场监督管理局 | 湖北省市场监管 | 湖北省市场监督管理局 | ||

| 湖北省司法厅 | 司法部 * | 湖北省司法厅 | 湖北省司法厅 | |

| 湖北省科学技术厅 | / | / | / | |

| Municipal | 武汉市人民政府 | 云上武汉 * | 武汉发布 | 武汉发布 |

| 武汉市卫生健康委员会 | 健康武汉 | 健康武汉官微 | 健康武汉官微 | |

| 武汉市民政局 | 武汉民政 | 武汉民政 | 武汉民政 | |

| 武汉市疾病预防控制中心 | 武汉人社 @ | 武汉疾控 | 武汉疾控 | |

| 武汉市人力资源和社会保障局 | / | 武汉人社 | 武汉人力资源和社会保障 | |

| 武汉市交通运输局 | / | 武汉交通运输 | 武汉交通 | |

| 武汉市教育局 | / | 武汉教育 | / | |

| 武汉市经济和信息化局 | / | 武汉市经信局 | 武汉经信 | |

| 武汉市农业农村局 | / | 武汉农业农村 | 武汉农业农村 | |

| 武汉市商务局 | / | 武汉和谐商务 | / | |

| 武汉市公安局 | 武汉公安 @ | 平安武汉 | 平安武汉 | |

| 武汉市财政局 | / | 武汉财政 | 武汉财政 | |

| 武汉市市场监督管理局(药品监督管理局) | / | 武汉市场监督 | / | |

| 武汉市国司法局 | 司法局 * | / | 武汉司法 | |

| 武汉市科学技术局 | 江城网 * | / | 武汉科技创新 |

Notes. ①The portal has the same name as the department.

② On behalf of the department, it has not opened the government affairs information release.

③ Apps with three situations, including ineffective access caused by installation, operation, or authorization; presence of external links, and extending business services are excluded, including 15 completely excluded apps.

Represents the ineffective access of the app caused by installation, operation, or authorization, n=7.

Represents all the contents of the apps being externally linked to their official portals, and there is no app page, n=4.

Represents that this is a business service-oriented app, n=4.

Table 2.

Names of Government Departments and Bureaus Included in the Study

| Level | Department name | Abbreviation |

|---|---|---|

| Ministries of the State Council | The State Council, the People's Republic of China | GOV.CN |

| National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China | NHCC | |

| Ministry of Civil Affairs of the People's Republic of China | MCAC | |

| Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention | CCDCP | |

| Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security of the People's Republic of China | MHRSSC | |

| Ministry of Transport of the People's Republic of China | MTC | |

| Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China | MEC | |

| Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of the People's Republic of China | MIITC | |

| Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People's Republic of China | MARAC | |

| National Medical Products Administration | NMPA | |

| Ministry of Commerce of the People's Republic of China | MCC | |

| The Ministry of Public Security of the People's Republic of China | MPSC | |

| Ministry of Finance of the People's Republic of China | MFC | |

| State Administration for Market Regulation | SAMR | |

| Ministry of Justice of the People's Republic of China | MJC | |

| Ministry of Science and Technology of the People's Republic of China | MSTC | |

| Departments of Hubei Province Government | The Peoples Government of Hubei Province | GOV.HUBEI |

| Health Commission of Hubei Province | HCHB | |

| Department of Civil Affairs of Hubei Province | DCAHB | |

| Hubei Province Center for Disease Control and Prevention | HBCDCP | |

| Human Resources and Social Security Department of Hubei Province | HRSSDHB | |

| Department of Transportation of Hubei Province | DTHB | |

| Hubei Provincial Department of Education | HBDE | |

| Department of Economy and Information Technology of Hubei Province | DEITHB | |

| Department of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of Hubei Province | DARAHB | |

| Medical Products Administration of Hubei Province | MPAHB | |

| Department of Commerce of Hubei Province | DCHB | |

| Department of Public Security of Hubei Province | DPSHB | |

| Hubei Provincial Department of Finance | HBDF | |

| Department of Market Regulation of Hubei Province | DMRHB | |

| Department of Justice of Hubei Province | DJHB | |

| Science and Technology Department of Hubei Province | STDHB | |

| Bureaus of Wuhan Government | The Government of Wuhan | GOV.WUHAN |

| Wuhan Municipal Health Commission | WHMHC | |

| Wuhan Civil Affairs Bureau | WHCAB | |

| Wuhan Center for Disease Control & Prevention | WHCDCP | |

| Wuhan Municipal Human Resources and Social Security Bureau | WHMHRSSB | |

| Wuhan Transport Bureau | WHTB | |

| Wuhan Education Bureau | WHEB | |

| Wuhan Economy and Information Technology Bureau | WHEITB | |

| Wuhan Agriculture and Rural Affairs Bureau | WHARAB | |

| Wuhan Commerce Bureau | WHCB | |

| Wuhan Public Security Bureau | WHPSB | |

| Wuhan Finance Bureau | WHFB | |

| Wuhan Market Regulation Bureau | WHMRB | |

| Wuhan Justice Bureau | WHJB | |

| Wuhan Science and Technology Bureau | WUSTB |

Notes. The Center for Disease Control & Prevention is not a department but just a bureau of the Health Commission department at all levels. But because it is very important for epidemic prevention and control, it often appears in the 39 authoritative documents of GOV.CN. Moreover, it has its own information release channels. Hence, we list it separately.

3.1. Government Portal

Government portals are responsible for the transmission of government information, government affairs, social services, and other information (Song, Guan, Zhang, Yang, & Wang, 2018). Each of the 47 government departments surveyed owns a government portal. Among them, Industry and Information Technology was renamed to DEITHB at Hubei Province (People.cn. 2020) and WHEITB (Wuhan municipal government, 2019) at Wuhan.

Because the COVID-19 epidemic is highly serious and has caused much concern, most government portals have special columns on the COVID-19, with some government portals having more than one. Thus, the 25 government departments have set up 33 epidemic columns. Among these, 15 are at the level of Ministries of the State Council (except MTC), eight are at the level of Departments of Hubei Province Government (GOV.HUBEI, HCHB, HBCDCP, DEITHB, DARAHB, HBDF, DJHB, and STDHB), and two are at the level of Bureaus of Wuhan Government (WHMHC and WHCDCP). COVID-19 special columns are available in other government departments, except the Ministry of Transport. The government portals in Hubei and Wuhan have fewer special columns about COVID-19. And most of the information about the epidemic is released in the “Notices” and the “Key Points” columns. Therefore, the data in this investigation mainly come from the epidemic columns in the portal of Ministries of the State Council and partly from the epidemic columns and the information in the “Notices” and “Key Points” in the Departments of Hubei Province Government and Bureaus of Wuhan Government.

3.2. Government App

Government app is a service platform integrating new technologies, and it is more personalized and precise in dissemination of information and business services (Song et al., 2018). We searched for information about the government app on its portal and searched for the names of the 47 government departments in the main platforms on the Chinese Internet; the first is Huawei application market and Tencent application treasure. If there was no related information, then we searched for the relevant department app in Baidu, Sogou, and 360 search engines. Finally, it was found that among the 47 government departments investigated, there were 25 official apps, including 12 at the Ministries of the State Council level (except CCDCP MIITC, MARAC and MSTC), six government apps at the Departments of Hubei Province Government level (including GOV.HUBEI, DARAHB, DCAHB, HBCDCP, DPSHB, and DJHB), seven at the Bureaus of Wuhan Government level (including GOV.WUHAN, WHMHC, WHCAB, WHMHRSSB, WHPSB, WHJB and WUSTB).

Then, apps with three situations, such as ineffective access caused by installation, operation, or authorization; having external links; and extending business services were excluded (15 completely and 2 partially excluded). Those completely excluded were as follows:

-

①

Seven ineffective visits, namely, MHRSSC, DARAHB, DPSHB, DJHB, GOV.WUHAN, WHJB, and WUSTB.

-

②

All the contents of four apps that were externally linked to their official portals and that had no app page, namely, MCC, GOV.HUBEI, HBCDCP, and DCAHB.

-

③

Four business service-oriented apps, SAMR, MPSC, WHMHRSSB, and WHPSB. The two partially excluded ones were MCAC and MJC, because some of their content was not externally linked from their official portals, and this investigation excluded their external link contents.

Therefore, this investigation studied 10 government apps in total.

3.3. Government Weibo

As the number of social media users has increased, government departments have opened government Weibo accounts to release information, spread images, and provide public services (Bai, & Zhang, 2017). By searching the names of 47 government departments and searching the government Weibo information on their portals, we found that 34 of the 47 government departments own government Weibo accounts: 13 are at the Ministries of the State Council (except MHRSSC, MARAC, and MFC); the seven government departments under Departments of Hubei Province Government are GOV.HUBEI, DEITHB, DARAHB, MPAHB, DPSHB, DMRHB, and DJHB. There are 14 government departments in the Bureaus of Wuhan Government, and only the Justice Department does not own a government Weibo account. However, the Weibo account “Innovation Wuhan” of the WHEITB has been cancelled; so, this investigation collected 33 government Weibo accounts in total with information related to the COVID-19 epidemic.

3.4. Government WeChat

Due to the rapid development of mobile Internet and smart phones, the channels of government affairs communication have come to the era of “double micro” in China. And with the high popularity of WeChat, government WeChat plays a more prominent role in the access to Chinese government information and related businesses (Wang et al., 2018). We searched for the names of the investigated 47 government departments in WeChat and searched for government WeChat information on government portals. Finally, it was found that there were 42 government WeChat accounts for the 47 government departments; 15 are in Ministries of the State Council (except MARAC), 15 are in the Departments of Hubei Province Government (except STDHB), and 13 are in the Bureaus of Wuhan Government (except WHEB and WHMRB). Among them, the certification of “Healthy Hubei” is for the Hubei Health and Family Planning Education Center, but the official portal of the Hubei Health Committee also officially points to this account. Therefore, we take “Healthy Hubei” as the acquiescent government WeChat of WHMHC. The statistics on the government information release accounts of different channels and different levels are shown in Table 3 .

Table 3.

Statistics of Government Information Release Accounts

| Level | Portal | App | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ministries of the State Council | 16 | 8 | 13 | 15 | 52 |

| Departments of the Hubei Province Government | 16 | 0 | 7 | 15 | 38 |

| Bureaus of the Wuhan Government | 15 | 2 | 13 | 13 | 43 |

| Total | 47 | 10 | 33 | 43 | 133 |

In terms of channels, there are 47 government portals in this investigation, which cover all departments. And there are 43 government WeChat accounts, except MARAC in Ministries of the State Council, STDHB in the Departments of Hubei Province Government, and WHEB and WHMRB in the Bureaus of Wuhan Government. Compared to government portals and WeChat, there are only 33 government Weibo accounts. Especially in the Departments of Hubei Province Government, government Weibo accounts are less than half (n=7). Regarding the government apps, only 10 apps were included. In fact, seven government apps were ineffective when visited, all the contents of another four apps were externally linked to their government portals, and there were four business service-oriented apps. Consequently, this investigation did not cover the data of these 15 apps.

In terms of levels, the Ministries of the State Council own most government information release accounts (n=52). There are three channels covering almost all government departments except the app channel. However, the number of government information release accounts in the Departments of Hubei Province Government was the least (n=38), mainly because all the apps of the Departments of Hubei Province Government were not included in this investigation, and there were fewer departments in the Hubei Province's own government Weibo accounts (n=7). As for the Bureaus of Wuhan Government (n=43), except for only two apps, the departments basically own their government information release accounts in other channels.

4. COVID-19 Information Release Characteristics of Chinese Government and Departments

This investigation reveals the behavior rules of government information release and its impact by examining five dimensions of the characteristics of the 133 government information release accounts. It can be seen from the relevant research cited in Section 2 that the five characteristics of scale, agility, frequency, originality, and impact have a great influence on government information release. Specifically, the total number of releases can reflect how much the government information releaser scores on the scale of COVID-19 epidemic (Savoia et al., 2017), the first release date can reflect the agility of government information releaser on providing information on the COVID-19 epidemic (Ruiu, 2020), the daily release volume can reflect the frequency of release of COVID-19 epidemic information by the government information releaser (thus avoiding the influence of time) (Zhou, Li, & Huang., 2015), the originality rating can reflect the originality of the released government information (Fu et al. 2016), and the influence ranking can reflect to what extent the government information released will affect the work on COVID-19 epidemic prevention and control (Gilmour et al., 2016). Therefore, this investigation mainly analyzes the characteristics of information release by the Chinese government about the COVID-19 epidemic in terms of the five dimensions of scale, agility, frequency, originality, and impact. The definitions and measures of the characteristics are shown in Table 4 .

Table 4.

Definitions and Measures of the Characteristics

| Characteristics | Measures | Definitions |

|---|---|---|

| Scale | Total number of releases | The total number of all relevant information released by the government information releaser |

| Agility | First release date | The time when the first relevant information was released by the government information releaser |

| Frequency | Daily release volume | The daily release volume of relevant information released by the government information releaser |

| Originality | Originality rating | The proportion of original information released by the government information releaser |

| Impact | Influence ranking | The ranking of influence of government information releaser on the public, to be calculated according to different channels |

4.1. Scale

The measure of scale is the total number of releases, i.e., the total number of all relevant information released by the government information releaser in this event, which reflects the attention of the government information releaser toward the event and is also an important measure of the content production capacity of the government information releaser (An & Tao, 2019). Generally speaking, the higher the number of releases, the higher is the government's attention to and participation in the event. Table 5 shows the number of information releases by different departments at different levels in various channels.

Table 5.

Total Number of Information Releases by Various Departments in Different Channels

| Department | Portal | App | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GOV.CN | 890 | 1222 | 833 | 401 | 3346 |

| NHCC | 2412 | 5356 | 1660 | 1788 | 11216 |

| MCAC | 1026 | 367 | 275 | 490 | 2158 |

| CCDCP | 378 | / | 219 | 189 | 786 |

| MHRSSC | 292 | / | / | 96 | 388 |

| MTC | 274 | 232 | 909 | 339 | 1754 |

| MEC | 329 | 109 | 396 | 132 | 966 |

| MIITC | 509 | / | 481 | 420 | 1410 |

| MARAC | 61 | / | / | / | 61 |

| NMPA | 527 | 81 | 385 | 435 | 1428 |

| MCC | 472 | / | 270 | 198 | 940 |

| MPSC | 1042 | / | 2047 | 29 | 3118 |

| MFC | 151 | 177 | / | 246 | 574 |

| SAMR | 1217 | / | 815 | 502 | 2534 |

| MJC | 380 | 83 | 474 | 445 | 1382 |

| MSTC | 670 | / | 69 | 349 | 1088 |

| GOV.HUBEI | 4201 | / | 1340 | 1468 | 7009 |

| HCHB | 2196 | / | / | 650 | 2846 |

| DCAHB | 77 | / | / | 187 | 264 |

| HBCDCP | 287 | / | / | 124 | 411 |

| HRSSDHB | 42 | / | / | 122 | 164 |

| DTHB | 118 | / | / | 27 | 145 |

| HBDE | 12 | / | / | 173 | 185 |

| DEITHB | 167 | / | 35 | 24 | 226 |

| DARAHB | 701 | / | 116 | 132 | 949 |

| MPAHB | 295 | / | 122 | 364 | 781 |

| DCHB | 95 | / | / | 15 | 110 |

| DPSHB | 85 | / | 896 | 282 | 1263 |

| HBDF | 252 | / | / | 188 | 440 |

| DMRHB | 65 | / | 4 | 18 | 87 |

| DJHB | 1798 | / | 41 | 245 | 2084 |

| STDHB | 188 | / | / | / | 188 |

| GOV.WUHAN | 669 | / | 3594 | 1485 | 5748 |

| WHMHC | 863 | 278 | 334 | 22 | 1497 |

| WHCAB | 97 | 4 | 8 | 35 | 144 |

| WHCDCP | 326 | / | 27 | 9 | 362 |

| WHMHRSSB | 24 | / | 11 | 1 | 36 |

| WHTB | 243 | / | 233 | 306 | 782 |

| WHEB | 61 | / | 496 | / | 557 |

| WHEITB | 10 | / | 0 | 9 | 19 |

| WHARAB | 18 | / | 83 | 9 | 110 |

| WHCB | 113 | / | 1 | 0 | 114 |

| WHPSB | 9 | / | 118 | 176 | 303 |

| WHFB | 8 | / | 0 | 2 | 10 |

| WHMRB | 3 | / | 2 | / | 5 |

| WHJB | 26 | / | / | 334 | 360 |

| WUSTB | 10 | / | / | 32 | 42 |

| Total | 23689 | 7909 | 16294 | 12498 | 60390 |

Note. The bold values in Table 5 are the largest number or the total number in each channel.

From the perspective of channels, there are differences between them. The total number of information releases by microblogs of the government (Weibo + WeChat) was the highest (n=28792). When Weibo and WeChat were viewed separately, the total number of portal releases was the highest (n=23689), but the average number of app releases was the most (n=791). Specifically, the department with the highest number of release on portals (mean=504.02, median=252.00, standard deviation [SD]=780.18) was GOV.HUBEI (n=4201). Among the apps (mean=790.90, median=204.50, SD=1641.38), NHCC (n=5356) was the dominant department. This is related to the fact that many government apps are mainly positioned for business management. The department with the highest number of releases on government Weibo (mean=493.76, median=233, SD=750.57) was GOV.WUHAN (n=3594), and NHCC (1788) had the highest number on government WeChat (mean=290.65, median=187, SD=397.14). In addition, compared with portal, apps, and Weibo, the average number of releases on WeChat was fewer than the overall average number.

From the perspective of levels, there are differences between the levels too. Not only the total number of releases (n=33149) on the Ministries of the State Council, but also its average (n=637), was the highest. Among the Ministries of the State Council (mean=637.48, median=390.50, SD=842.72), the maximum number of releases was on the app owned by NHCC (n=5356), and the minimum was on WeChat owned by MPSC (n=29). Among the Departments of Hubei Province Government (mean=451.37, median=149.50, SD=812.41), the maximum number of releases was on the portal owned by GOV. HUBEI (n=4021), and the minimum was on the Weibo owned by DMRHB (n=4). Among the Bureaus of Wuhan Government (mean=234.63, median=26, SD=595.43), the maximum number of releases was on the Weibo owned by GOV.WUHAN (n=3594), and the minimum was on the Weibo owned by WHEITB and WHFB and on WeChat owned by WHCB (n=0). The maximum number of releases owned by the Bureaus of Wuhan Government was 3594, with a median value of 26, much smaller than the number in the other two levels, which indicates that the number of releases by the Bureaus of Wuhan Government was concentrated on a small value. Paired t-test was conducted for the total number of releases at different levels. At the 95% confidence interval, P (China national level * Hubei provincial level)=0.137>0.05; so, there was no significant difference between the Ministries of the State Council and the Departments of Hubei Province Government in terms of the scale. P (China national level * Wuhan municipal level)=0.049<0.05, and P (Hubei provincial level * Wuhan municipal level)=0.029<0.05; accordingly, there was a significant difference between Ministries of the State Council and the Bureaus of Wuhan Government, as well as between the Departments of Hubei Province Government and the Bureaus of Wuhan Government.

From the perspective of departments, the main epidemic prevention and control work is promoted by the People's Government and the Health Commission, while 14 other departments work together closely. The People's Government released the most (n=16103), followed by the Health Commission (n=15559), and even the least two departments – Human Resources and Social Security – released 588 articles related to the epidemic. The average number released by all departments was 3774.38, and the median number was 1958.50, indicating that all departments participate in the epidemic prevention and control work actively. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed for the total number of releases by different departments. At the 95% confidence interval, P=0.004<0.05; so, there were significant differences in terms of the scale for the different departments.

4.2. Agility

The measure of the agility is the time of first release or the first response time, i.e., the time when the government information releaser releases the first relevant information about the event (Zhou, Li, & Huang, 2019). Generally, the date is the minimum unit of time measurement, so it can also be the first release date. The earlier the first release date, the sooner the government information releaser has grasped the emergency information, and provided feedback within a short time after receiving the relevant information. And the faster response rate also shows that the releaser is more sensitive to the emergency information and quicker to respond. This research analyzes the first release date of various government information releasers from different channels, levels, and departments. What should be noted is that the amount of government information release about COVID-19 in the WHEITB and WHFB Weibo accounts and the WHCB WeChat account is zero; so, it is not calculated in the value of all the first release dates.

4.2.1. First Release Date in Different Channels

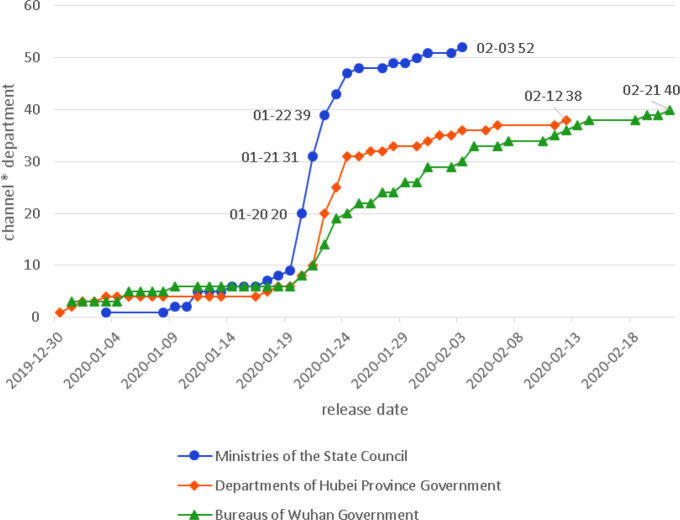

The analysis of the first release date of the different channels can reflect the agility of the government information release in different channels. Figure 1 shows the curve for the cumulative number of Level * Department for the first release date in each channel.

Figure 1.

Cumulative number of Level * Department first release date in each channel.

Overall, microblogs of government channels, especially Weibo, have the highest agility, while portals and apps are relatively slow. In terms of the first release date in each channel, the earliest is on the portal (December 30, 2019, HCHB); Weibo (December 31, 2019, GOV.WUHAN) and WeChat (December 31, 2019, GOV. HUBEI, GOV.WUHAN, WHMHC) followed closely, which showed the convenience and timeliness of microblogs of the government. It should be noted that among the portals of the Ministries of the State Council, the earliest release date is relatively late, except for the CCDCP. The main reason is that most data of the portals of the Ministries of the State Council are collected from the columns of COVID-19, but the columns are usually created only when the epidemic is quite serious; hence, the first release date on the portals of the Ministries of the State Council may be earlier in fact. For example, on the portal of GOV.CN, the earliest release time is 2020-01-20, and the released information is “Xi makes important instructions on the outbreak of COVID-19 epidemic”, but the first release date in the epidemic column is 2020-01-25 (The State Council, the People's Republic of China, 2020). The app is the last (January 5, 2020, WHMHC); this is mainly because the app generally pushes links to authoritative portals, so there is an uncertain lag.

A phenomenon about the intensive first release date is worth noting. Starting from January 20, the number of first release date for all departments in all channels has increased sharply (the slope is quite large). On this day, the Chinese government released a lot of news. It was also the day that COVID-19 was included under Class B of infectious diseases in the Infectious Disease Prevention Act of P R China. This shows that various departments operating in accordance with relevant laws and regulations have responded in a timely manner and have a high degree of agility in responding to government news and disseminating information on outbreaks through various channels.

As of February 4, all apps have released COVID-19 news. For Weibo, the date is February 13, the portal's date is February 19, and WeChat's release is on February 21. Considering the different numbers of departments included in each channel, we think that the curve growth trend before and after January 20 is more indicative of agility. It can be seen that the Weibo curve grows faster before January 20, and more departments release information; then after January 20, the curves of Weibo and WeChat reach a steady state quickly. Therefore, whether they release government news or not, the agility of microblogs of government in responding to the epidemic is relatively high.

4.2.2. First Release Date of Different Levels

The different levels’ first release date can reflect the agility of the different levels of the government in responding to relevant events. Figure 2 shows the cumulative number of Channel * Department curve for the first release date of each level.

Figure 2.

Cumulative number of Channel * Department first release date of each level.

For the first release date, the Departments of Hubei Province Government was the earliest (December 30, 2019), and the Bureaus of Wuhan Government was second (December 31, 2019). The Ministries of the State Council released just a little later, on January 3, 2020. This reflects that the agility of the three levels of the government in responding to the epidemic is relatively high. Paired t-test was performed for the first release dates of different levels. At the 95% confidence interval, P(China national level * Hubei provincial level)=0.307>0.05; so there was no significant difference between the first release dates of the Ministries of the State Council and the Departments of Hubei Province Government. P(China national level * Wuhan municipal level)=0.035<0.05, and P(Hubei provincial level * Wuhan municipal level)=0.001<0.05, so there was a significant difference between the Ministries of the State Council and the Bureaus of Wuhan Government, as well as between the Departments of Hubei Province Government and the Bureaus of Wuhan Government.

In general, before January 20, the Departments of Hubei Province Government and the Bureaus of Wuhan Government showed high agility in detecting the epidemic situation, and after January 20, the Ministries of the State Council were more agile in responding to the epidemic. The intensive release time at the Ministries of the State Council level is January 20, January 21, and January 22, and the number is 20, 31, and 39, respectively. The Departments of Hubei Province Government level and the Bureaus of Wuhan Government level are just 1-2 days behind. Since China has included COVID-19 under Class B of infectious diseases on January 20, this indicates that the overall agility of the three levels of government in responding to a confirmed epidemic is relatively high.

As of February 3, 52 Channel * Department domains of the Ministries of the State Council have all released information; as of February 12, a total of 38 Channel * Department of the Departments of Hubei Province Government have all released information; and as of February 21, 40 Channel * Department domains of the Bureaus of Wuhan Government have all released information. Meanwhile, after January 20, it is mainly the departments other than the Health Commission that released the first information. Furthermore, it is obvious that the level of the Ministries of the State Council is earlier than the level of the Departments of Hubei Province Government, and the Departments of Hubei Province Government level is earlier than the Bureaus of Wuhan Government level after January 20. This shows that it is very important to launch multisectoral assistance at every government level from top to bottom to respond to a confirmed epidemic quickly.

4.2.3. First Release Date of Different Departments

The first release date of different departments can reflect the agility of government information release of different departments in response to relevant events. Figure 3 shows the cumulative number of Channel * Department curve of the first release date of each department.

Figure 3.

Cumulative number of Channel * Level first release date of each department.

Overall, all departments of the Chinese government are very agile in responding to the COVID-19 epidemic. The first release time of the Health Commission is the earliest (December 30, 2019), which indicates that the outbreak of COVID-19 is a public health event related to the Health Commission. The People's Government is closely behind (December 31, 2019), which also shows that the People's Government plays a direct leadership role in responding to a suspected epidemic outbreak.

In particular, it is worth noting that all departments began to release information before the “Travel restriction” in Wuhan on January 23. Considering that China only included COVID-19 under Class B of infectious diseases on January 20, it means that all relevant departments responded to the outbreak within 3 days, and all the departments as a whole showed a very high agility in responding to the confirmed epidemic outbreak.

One-way ANOVA was performed for the first release date of different departments. At the 95% confidence interval, P=0.003<0.05; thus, there were significant differences in the first release date of different departments.

4.3. Frequency

The measure of frequency is the daily release volume, i.e., the number of daily releases by government information releasers during the event (Trimble & Ceja, 2013; Wang, Wei, Yang, Zhong, & Wang, 2015). The number of daily information releases can directly reflect the frequency of government information releases during the whole event. Furthermore, the frequency of government information release may be different for different channels, levels, and departments.

4.3.1. Daily Release Volume in Different Channels

The daily release volume in different channels can reflect the frequency of responding to relevant events by the departments at all government levels in these channels. Figure 4 shows the daily release volume curves of different channels.

Figure 4.

Daily release volumes in different channels.

Overall, the frequency of the portals is the highest (307.65 per day). Weibo (214.39 per day) and WeChat (164.45 per day) are relatively close to each other, while the frequency of the app (111.39 per day) is relatively low. Initially, all channels were not so active until January 20, which is related to the fact that the COVID-19 epidemic has not been confirmed. Then, from January 20 to January 30, the frequency of all channels increased rapidly. It is worth noting that the GOV.CN set up a leading group on January 25 to deal with the epidemic situation, which led to a significant improvement in the frequency of all channels. Finally, after January 30, the frequency of each channel fluctuates within a certain range; at the same time, the curve fluctuations of the four channels are similar and have a certain coupling relationship. For example, all the curves simultaneously show a trough on February 9 and then turn up to a clear peak because of two important information releases on February 10. One is that the logistics services across the country resume operation thoroughly, and the other is that the sealing-off measure is adopted for all the districts of Hubei Province.

It should be noted that the information released by some portals does not present a clear time. For example, the portal of GOV.CN has two topics: the Question authority response; and Epidemic prevention and control knowledge base; so, these data are not included in the daily release volume. If these data were included, the daily release volume of portals would be higher, but because the daily release volume of portals is much higher than that of other channels, it would not change the conclusion of this investigation.

4.3.2. Daily Release Volume of Different Levels

The daily release volume of different levels can reflect the frequency of all departments in a specific level of government responding to relevant events in different channels. Figure 5 shows the daily release volume curves of different levels.

Figure 5.

Daily release volume of different levels.

Overall, the frequency of the Ministries of the State Council level is the highest (454.10 per day), and the Departments of Hubei Province Government level (222.75 per day) and the Bureaus of Wuhan Government level (132.75 per day) are relatively close. The Bureaus of Wuhan Government have slightly higher frequency than the Departments of Hubei Province Government in the early stage, but the situation is opposite in the later stages. One-way ANOVA was performed for the daily release volume of different levels. At the 95% confidence interval, P=0.000<0.05; so, there were significant differences in the daily release volume of different levels.

Specifically, the frequency of all three levels before January 20 was not high, and the Bureaus of Wuhan Government level were relatively active. But the frequency of all levels increased rapidly since January 20 because of the first announcement of NHCC. After January 30, the daily release volume of the Ministries of the State Council level varied between 500 and 900, while the daily release volume of the Departments of Hubei Province Government level changed between 250 and 463 and the Bureaus of Wuhan Government level stabilized around 200. The obvious differences in the daily release volume show that although Wuhan is the core of China's COVID-19 epidemic, most of the confirmed cases of COVID-19 in China are also in Wuhan (50008 out of 81802, as on April 8, 2020). The frequency of the Ministries of the State Council level is extremely important for the effective prevention and control of COVID-19 epidemic. Considering the failure of government responses to the COVID-19 epidemic in the United States (Maicol, 2020), we suggest that it is not a good choice to rely on local governments to solve problems by themselves.

4.3.3. Daily Release Volume of Different Departments

The daily release volume of different departments can reflect the frequency of information release of different government departments in relation to relevant events. Figure 6 shows the daily release volume curves of different departments.

Figure 6.

Daily release volume of different departments.

Overall, all government departments, according to their specific scope of responsibilities, have a very high frequency in terms of epidemic prevention and control. One-way ANOVA was performed for the daily release volume of different departments. At the 95% confidence interval, P=0.000<0.05; so, there were significant differences in the daily release volume of different departments. Specifically, the daily release volumes of the People's Government (211.88 per day) and the Health Commission (202.06 per day) are very high. In addition, the daily release volume of Public Security (82.18 per day) is a little higher than for other departments, such as Justice (52.41 per day), Market Regulation (48.63 per day), Civil Affairs (45.82 per day), and Transport (45.44 per day), and the minimum value is seen for Human Resources and Social Security, viz., 10.69 per day, still relatively high for a government department. It needs to be emphasized that although the absolute volume of daily release among different departments varies greatly, considering that government departments often correspond to their specific areas respectively and the correlation between their responsibilities and epidemic situation varies greatly, the results reflect that their daily release volume greatly matches the correlation between their responsibilities and epidemic prevention and control. Therefore, it can be inferred that all government departments show a relatively high frequency matching their responsibilities in epidemic prevention and control.

4.4. Originality

The originality mainly refers to the original creativity of the government information releaser, which can be measured by the originality rating of the released information (Rocchi & Resca, 2018). The originality rating is the proportion of original information released by the government information releaser. On the one hand, it reflects the productivity of original content by the government information releaser, and on the other hand, it also indirectly reflects the degree of attention of the releaser to the event. In this investigation, the originality of the information depends on whether the source of released information is the releaser. Specifically, there is a source or author tag on the portals/apps and “repost Weibo” tag on Weibo; so, it is easy to judge the originality in these three channels. It should be noted that WeChat forbids crawlers from accessing their data corresponding to the originality rate; so, this investigation uses the Systematic Sampling method to extract 10% of these WeChat data. In a few cases, the total number of releases in the government WeChat accounts is low (<30), so we extracted all data. Then, six senior college students manually identified whether the extracted data were original. Table 6 shows the originality rates of different government departments in different channels.

Table 6.

Originality Rates of Departments for Various Channels (%)

| Department | Portal | App | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GOV.CN | 84.83 | 31.42 | 96.04 | 68.29 |

| NHCC | 32.92 | 0.00 | 99.34 | 1.68 |

| MCAC | 20.37 | 0.00 | 99.27 | 62.00 |

| CCDCP | 37.30 | / | 98.17 | 42.11 |

| MHRSSC | 35.96 | / | / | 30.00 |

| MTC | 0.36 | 0.00 | 97.14 | 100.00 |

| MEC | 4.26 | 0.00 | 97.98 | 64.29 |

| MIITC | 15.72 | / | 93.97 | 0.00 |

| MARAC | 100.00 | / | / | / |

| NMPA | 4.93 | 45.68 | 98.96 | 20.45 |

| MCC | 26.06 | / | 100.00 | 10.00 |

| MPSC | 4.03 | / | 94.72 | 93.75 |

| MFC | 60.93 | 35.59 | / | 0.00 |

| SAMR | 8.13 | / | 89.94 | 45.10 |

| MJC | 22.37 | 0.00 | 99.79 | 22.22 |

| MSTC | 3.13 | / | 63.77 | 0.00 |

| GOV.HUBEI | 4.38 | / | 72.99 | 16.33 |

| HCHB | 14.62 | / | / | 19.70 |

| DCAHB | 33.77 | / | / | 10.53 |

| HBCDCP | 42.16 | / | / | 99.19 |

| HRSSDHB | 4.76 | / | / | 30.77 |

| DTHB | 35.59 | / | / | 22.22 |

| HBDE | 75.00 | / | / | 5.56 |

| DEITHB | 34.73 | / | 22.86 | 29.17 |

| DARAHB | 15.98 | / | 100.00 | 71.43 |

| MPAHB | 63.05 | / | 89.34 | 40.54 |

| DCHB | 11.58 | / | / | 43.75 |

| DPSHB | 10.59 | / | 79.80 | 17.24 |

| HBDF | 18.25 | / | / | 21.05 |

| DMRHB | 27.69 | / | 100.00 | 65.22 |

| DJHB | 4.28 | / | 82.93 | 12.00 |

| STDHB | 56.91 | / | / | / |

| GOV.WUHAN | 7.62 | / | 93.04 | 6.71 |

| WHMHC | 9.15 | 36.33 | 99.40 | 33.33 |

| WHCAB | 100.00 | 0.00 | 12.50 | 25.00 |

| WHCDCP | 27.61 | / | 100.00 | 55.56 |

| WHMHRSSB | 91.67 | / | 81.82 | 100.00 |

| WHTB | 6.17 | / | 95.71 | 9.68 |

| WHEB | 14.75 | / | 96.77 | / |

| WHEITB | 80.00 | / | 0.00 | 100.00 |

| WHARAB | 94.44 | / | 72.29 | 44.44 |

| WHCB | 28.32 | / | 100.00 | 0.00 |

| WHPSB | 11.11 | / | 75.42 | 11.11 |

| WHFB | 87.50 | / | 0.00 | 100.00 |

| WHMRB | 100.00 | / | 50.00 | / |

| WHJB | 100.00 | / | / | 5.88 |

| WUSTB | 90.00 | / | / | 50.00 |

| Total | 18.76 | 7.40 | 92.25 | 31.07 |

Note. Total originality rate = the number of original information releases in the channel/the total number of information releases in the channel.

From the perspective of channels, the originality rating in Weibo (mean=80.42%, median=94.73%, SD=29.74%) is very high, while that in WeChats (mean=37.36%, median=29.17%, SD=32.17%%) and portals (mean=37.51%, median=27.61%, SD=33.68%) is relatively low, and the originality rating of apps is the lowest (mean=14.90%, median=0.00%, SD=19.55%). Specifically, because the information released on Weibo is mainly short text content, rather than formal official documents, most of the information is original (total=92.25%). A lot of information released on WeChat comes from portals and other media, so the total originality rating is not high (total=31.07%), which reveals the biggest difference between Weibo and WeChat. What is interesting is that portal is a very special channel. Although the portal originality rates of GOV. CN (84.83%), MARAC (100%), WHCAB (100%), WHMRB (100%), and WHJB (100%) are very high, the originality is relatively low in total (total=18.76%), and the standard deviation (SD=33.68%) of portal's originality rating is the largest, which implies that these department portals play different collaborative roles in COVID-19 information release. Consequently, since some portals usually forward authoritative information released by other departments’ portals, the originality rate of most portals is low (median=27.61%). In addition, the portal, with its smallest originality rate of 3.13% from MSTC, is a unique channel in that it does not just forward information, which is in line with the authority of the portals of the various departments and means that the mutual support between departments is very comprehensive. As for the apps, the survey found that almost all content of apps is forwarded from the authoritative information released by government portals (median=0.00%). The highest originality rate of apps is only 45.68% from NMPA, and there are six apps with originality rate of 0%, just reproducing the content of portals; so, the total originality rate of the apps is very low (total=7.40%).

From the perspective of levels, the Bureaus of Wuhan Government level shows the highest originality rate (mean=53.57%, median=50.00%, SD=39.77%), followed by the Ministries of the State Council level (mean=45.44%, median=35.78%, SD=39.13%), and the Departments of Hubei Province Government level is slightly lower (mean=39.63%, median=29.97%, SD=30.41%). Paired t-test was performed on the originality rate of different levels, and P(China national level * Wuhan municipal level)=0.228>0.05 at the 95% confidence interval; so there was no significant difference between the originality rate of Ministries of the State Council and Bureaus of Wuhan Government. P(China national level * Hubei provincial level)=0.03<0.05, and P(Hubei provincial level * Wuhan municipal level)=0.004<0.05; so, there was a significant difference in originality rate between Ministries of the State Council and Departments of Hubei Province Government, as well as between the Departments of Hubei Province Government and the Bureaus of Wuhan Government. It is worth noting that, compared with the lower high originality rate characteristic of the Ministries of the State Council level (median=35.78%) and the Departments of Hubei Province Government level (median=29.97%), half of the originality rates are higher in the Bureaus of Wuhan Government level (median=50.00%). This implies that most Bureaus of Wuhan Government at the anti-epidemic forefront often need to make the latest releases through multiple channels according to the specific situation. And most Ministries of the State Council and Departments of Hubei Province Government often forward the information released by other departments. Therefore, in epidemic prevention and control, it is necessary to pay attention to the coordination of first-line information release and subsequent forwarding work.

From the perspective of departments, the originality rate reflects the departments’ collaborative roles in epidemic prevention and control. The Industry and Information Technology (mean=71.23%, median=72.29%, SD=31.53%), the Disease Control and Prevention (mean=62.76%, median=48.86%, SD=31.06%) and the Market Regulation (mean=60.76%, median=57.61%, SD=34.17%) departments present the top three originality rates. And these departments have the characteristics of being responsible for releasing information in specific fields. The lowest originality rate is shown by the Health Commission (mean=34.65%, median=26.31%, SD=36.43%), Justice (mean=38.83%, median=22.22%, SD=42.51%), and Finance (mean=40.42%, median=28.32%, SD=38.44%). The originality rate of the different departments was analyzed by one-way ANOVA. At the 95% confidence interval, the result was P=0.83>0.05. Therefore, there was no significant difference in the starting date of different departments. And these departments often synthesize multidepartmental information or have increased cross-cooperation with other departments during the COVID-19 epidemic. It should be emphasized that the difference in functions between the Disease Control and Prevention and the Health Commission are often neglected by news media and the general public, but they play quite different roles in epidemic prevention and information release.

4.5. Impact

The impact mainly refers to the influence ranking of the government information releaser, and the influence ranking of the releaser in a Public Health Emergency can be understood as the effective dissemination of and feedback on the information released (Zhang, Xu, & Xiao, 2014). We do not specifically calculate the influence of the government portals because most government portals do not present the feedback data of users. Similarly, some apps do not present behavioral data such as the number of readings, sharing, collecting, and likes; we consistently use the number of downloads as the evaluation index to judge app influence. The influence of government Weibo is generally evaluated by the sum number of forwards, comments, and likes, while the influence of government WeChat is generally evaluated by the sum number of readings, likes, and comments (Mei, Zhong, & Yang, 2015).

In terms of channels, government WeChat has the highest influence, followed by Weibo, portal, and app. It should be noted that different channels have different evaluation criteria, and it is difficult to quantitatively compare them. For the apps, they are evaluated by the number of downloads. For Weibo and WeChat, the measure is user interactions, i.e., the total number of forwards, comments, and likes; and the total number of reading, likes, and comments, respectively. So, considering the difference between their evaluations, we deduce the influence of different channels through the number of government accounts and the number of users in each channel.

Up to September 2019, WeChat had 1.15 billion monthly active accounts (Wx-pai, 2019), while Weibo had 497 million (Weibo, 2019). Meanwhile, according to the data we collected, the total number of readings, likes, and comments in WeChat (160,478,432) is much higher than the total number of forwards, comments, and likes in Weibo (17,952,424); so the influence of WeChat should be higher than that of Weibo. At the same time, China has a total of 15,143 government portals, while the number of government Weibos is 139,000 (China Internet Network Information Center, 2019). Weibo has an interactive function, but portals generally do not provide interactive functionality, so the influence of Weibo should be higher than that of the portal. From the perspective of scale, the number of releases on the portals is much higher than that on the apps. Meanwhile, it is pointed out in “The statistical report on the development of the Internet in China” that the development of the government apps is still relatively slow (China Internet Network Information Center, 2019); so, the influence of portals should be higher than that of apps. Therefore, it is very important for the government to make use of new media channels such as Weibo and WeChat, to expand the actual impact of information release and enhance its practical influence in epidemic prevention and control.

In terms of levels, we evaluate their influence ranking by the sum of user interaction data of Weibo and WeChat. In general, the influence of Ministries of the State Council (122,663,232) far exceeds that of Departments of Hubei Province Government (30,328,552) and Bureaus of Wuhan Government (25,439,072), while the influence of Departments of Hubei Province Government is close to that of Bureaus of Wuhan Government. Therefore, in epidemic prevention and control, National governments should strengthen their transmission work to maximize the influence of important authoritative information initially released at the provincial and municipal levels so as to effectively promote the release effect and coordinate the epidemic prevention and control with a larger scope.

In terms of departments, generally, the influence of the People's Government (68,739,628) and the Health Commission (64,922,043) is very high. The influence of 14 other departments is relatively low, but their cumulative influence is quite considerable (44,769,185). On the one hand, it shows that the People's Government and the Health Commission must act as the most important information release departments in epidemic prevention and control, and all important information releases should be forwarded through these two departments to enhance their influence. It can be seen from the above analysis using characteristics such as scale and originality that the Chinese government has effectively used the influence of these two departments. On the other hand, it is important to pay attention to other departments’ special function in information release and the superposition effect in epidemic prevention and control. It can also be illustrated from the originality ratings of these departments. At the same time, it is suggested that information related to the special responsibility of one department must be released through this department first, and then it should be forwarded through the People's Government and or the Health Commission in epidemic prevention and control.

5. Overall COVID-19 Information Release Situation of Chinese Government and Departments

Based on the analysis of the characteristics of COVID-19 information release, we used radar maps to further analyze the overall situation of COVID-19 information release of different channels, levels, and departments in China, and the measures of the five characteristics studied above were normalized to the range 0–5 to carry out this multidimensional comprehensive analysis.