Abstract

Ljungan virus (LV), a Parechovirus of the Picornavirus family, first isolated from a bank vole at the Ljungan river in Sweden, has been implicated in the risk for autoimmune type 1 diabetes. An assay for neutralizing Ljungan virus antibodies (NLVA) was developed using the original 87–012 LV isolate. The goal was to determine NLVA titres in incident 0–18 years old newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes patients (n=67) and school children controls (n=292) from Jämtland county in Sweden. NLVA were found in 41 of 67 (61 %) patients compared to 127 of 292 (44 %) controls (P=0.009). In the type 1 diabetes patients, NLVA titres were associated with autoantibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase (GADA) (P=0.023), but not to autoantibodies against insulin (IAA) or islet antigen-2 (IA-2A). The NLVA assay should prove useful for further investigations to determine levels of LV antibodies in patients and future studies to determine a possible role of LV in autoimmune type 1 diabetes.

Keywords: Ljungan Virus, Type 1 diabetes, human pathogen, neutralization assay, beta cell autoimmunity, glutamic acid decarboxylase autoantibodies

INTRODUCTION

Ljungan virus (LV), first isolated from a bank vole (Myodes glareolus) by the river Ljungan in Northern Sweden, was defined as a Parechovirus in the family Picornaviridae [1, 2]. The isolation of the 87–012 virus was followed by characterization of several different LV strains from humans, voles, other rodents, and birds [3–8]. However, it is unclear to what extent LV infection in humans causes symptoms characteristic of Parechovirus. LV from bank voles was proposed as a possible trigger of disease [9] or islet autoimmunity in both bank voles and humans [10–14]. Studies of possible associations between autoimmune diabetes and LV in humans suggested that the virus was transmitted from bank voles [14, 15]. LV in blood samples from humans and rodents was detected by PCR and prior exposure by LV antibodies (LVA) using the LV 145SLG strain in target cells [16]. In addition, recent data from Finland suggests that human-to-human transmission cannot be ruled out [17].

The aim of the present study was to establish a neutralizing LV antibody (NLVA) assay and to determine levels of NLVA in previously reported newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes children and healthy controls [11]. We also wanted to determine if the levels of NLVA correlated with LVA detected in a radiobinding assay (RBA) [11] or LV peptide antibodies detected in a suspension multiplex immunoassay (SMIA) [13]. Finally, we asked if NLVA were related to any of the autoantibodies against glutamic acid decarboxylase (GADA), islet antigen-2 (IA-2A), and three different isoforms of the ZnT8 transporter (ZnT8A).

METHODS

Study population

All children were from the Jämtland County in Sweden as reported previously [11] and represented 67 newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes children and 292 controls (Table 1). A blood sample was obtained at the time of diagnosis in patients consecutively diagnosed between June 2005 and November 2010. Blood samples from healthy school children were obtained during April, October and November of 2009, May, November and December of 2010 and in January, 2011 [11]. There was insufficient quantities of five samples from type 1 diabetes patients and three from controls of the previously reported analysis. These samples were not included in the comparisons between NLVA and LVA by RBA as well as LV peptide antibodies by SMIA [11, 13]. Samples from individuals with documented LV infection were not available as positive controls.

Table 1.

Type 1 diabetes patients and controls from the Jämtland county in Sweden

| Characteristics | Controls | Type 1 diabetes patients |

|---|---|---|

| n=292 | n=67 | |

| Age (years) median (range) | 14.1 (12.7, 15.0) | 10.0 (1.0, 17.9) |

| Sex | ||

| Males n (%) | 136 (46.6 %) | 33 (49.3 %) |

| Females n (%) | 156 (53.4 %) | 34 (50.7 %) |

Cell and virus culture

Ljungan virus, strain 87–012 was originally isolated from a bank vole, Myodes glareolus by the Ljungan River in the Medelpad County, Sweden [1]. Virus was titrated using the 50% cell culture infectious dose (CCID50) titration method [18]. Briefly, virus dilutions of 10−6 to 10−9 were added in triplicate to Vero-P cells in 96-well cell culture plates. The cytopathic effect (CPE) was determined on day 5, and CCID50titre was calculated according the Kärber formula. Titres were expressed by averaging the results of three independent tests [18].

Detection of Neutralizing Ljungan virus antibodies

The Ljungan virus neutralization antibody (NLVA) assay was developed based on the standard poliovirus neutralizing antibody assay [18]. The method has also been used for Enterovirus D-68 neutralizing antibodies [19]. The assay was performed on 96-well cell culture plates (Corning Inc., Corning, NY). Each serum was tested in triplicate with each plate containing four test sera at a starting dilution of 1 : 8 with subsequent twofold serial dilutions, the highest dilution being 1 : 1024. At each dilution, 25 microlitres of serum was mixed with 25 microlitres of Minimum Essential Medium (MEM) containing 100 CCID50 of LV strain 87–012. The virus-serum mixture was incubated for 3 h at 37 °C at 5 % (v/v) CO2. Then 100 microlitres of Vero cell suspension at concentration 3.0×105 cells per millilitre was added to each well and incubated for 7 days. Plates were stained with a solution of 0.05 % crystal violet solution, and scanned at an optical density of 570 nm using a Victor X4 (Perkin Elmer).

Our assay contained the following internal controls. First, one plate contained a known positive control that previously had shown positive results for Ljungan virus antibodies [13]. Second, a back-titration plate served as an additional control to ensure that the concentration of the virus used in the assays was accurate. Lastly, a cell control plate was used to ensure the viability of the Vero-P cells.

Analysis of islet autoantibodies

Autoantibodies against glutamic acid decarboxylase (GADA), islet antigen-2 (IA-2A), insulin (IAA) and ZnT8 variants (ZnT8-Arginine (ZnT8RA), ZnT8-Tryptophan (ZnT8WA), and ZnT8-Glutamine (ZnT8QA)) were determined as described [20, 21].

Statistical analysis

Proportions of NLVA positives and negatives between groups were compared by calculating unadjusted odds ratios (OR) and their associated 95 % confidence intervals (95 % CI) using exact methods. The null hypothesis of no difference in NLVA positivity between groups was tested using chi-squared test. The cumulative distribution functions (CDF) between type 1 diabetes patients and controls were compared using a bootstrap version of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (KSboot) that allows for ties [22]. There were many ties between the distributions on their lower and upper ends due to lower and upper detection limits. We used 10 000 bootstrap samples for the KSboot test. P-values ≤0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS statistical software (version 20, SPSS Inc. IBM, Chicago, Illinois, US) and R (r-project.org) version 3.6.0, and R packages ggplot2 and epiDisplay.

RESULTS

Neutralizing Ljungan Virus Antibodies in patients and controls

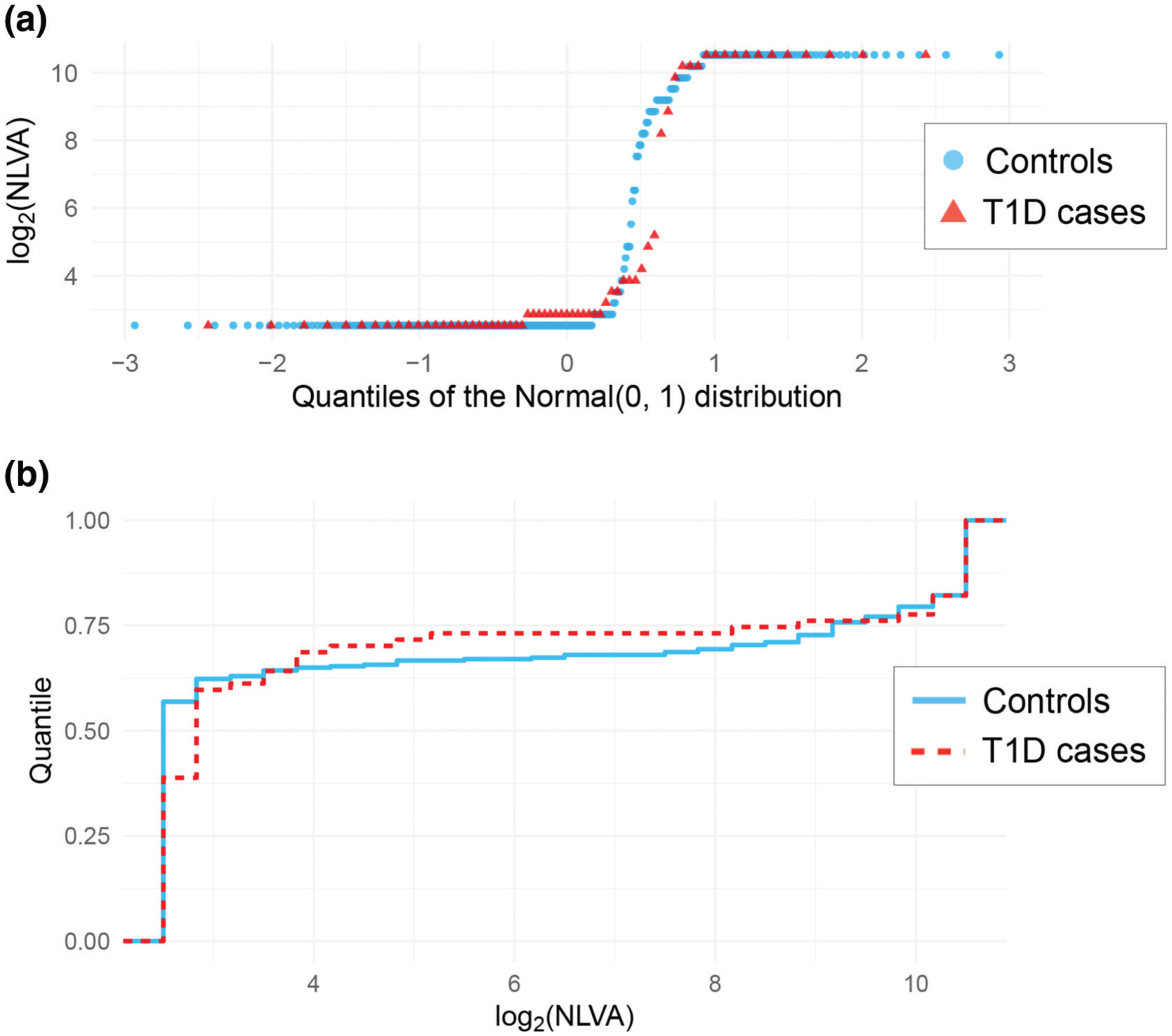

NLVA were detected in 127 of 292 (43 %) controls and in 41 of 67 (61 %) type 1 diabetes patients (P=0.009). The NLVA positivity was neither associated with age at diagnosis nor gender (data not shown). The NLVA titres, expressed on a log2 scale, ranged between 2.5 and 10.5, with values above 2.5 log2 considered positive. These two values correspond to the lower and upper detection limits, respectively. When comparing the distributions of NLVA titres in controls and type 1 diabetes patients, the detection limits result in ties at the lower and upper ends of the distributions (Fig. 1). Despite that, when we compare their cumulative distribution functions, there is evidence suggesting that the distribution of NLVA titres in controls differs from that in type 1 diabetes patients (P=0.017). NLVA were related to autoantibodies against glutamic acid decarboxylase (GADA) (P=0.016) but not to autoantibodies against insulin (IAA), islet antigen-2 (IA-2A) or any of the three isoforms of zinc transporter 8 (ZnT8A) (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Distributions of the log-transformed neutralizing Ljungan virus antibodies (NLVA) binding levels among type 1 diabetes cases (n=67) and controls (n=292). (a) Shows the quantiles of each of these distributions compared to the quantiles of the Normal (0, 1) distribution (red triangles for T1D cases, blue circles for controls). (b) Shows the cumulative distribution for T1D cases (red dashed line) and controls (blue solid line). There are many ties due to the lower and upper detection limits, but there is evidence that the distributions are different between T1D cases and controls (p-value=0.017).

Table 2.

The odds ratio (OR) estimates and their 95 % confidence intervals (95 % CI) of the association between neutralizing Ljungan virus antibodies (NLVA) and six islet autoantibodies. The p-values are based on a chi-squared test

| NLVA | OR (95 % CI) p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | |||

| GADA | Negative | 16 | 13 | 3.45 (1.23, 9.63) P=0.016 |

| Positive | 10 | 28 | ||

| IAA | Negative | 16 | 29 | 0.66 (0.23, 1.87) P=0.435 |

| Positive | 10 | 12 | ||

| IA-2A | Negative | 9 | 8 | 2.18 (0.71, 6.68) P=0.166 |

| Positive | 17 | 33 | ||

| ZnT8RA | Negative | 11 | 16 | 1.15 (0.42, 3.11) P=0.789 |

| Positive | 15 | 25 | ||

| ZnT8WA | Negative | 12 | 23 | 0.67 (0.25, 1.80) P=0.427 |

| Positive | 14 | 18 | ||

| ZnT8QA | Negative | 15 | 28 | 0.63 (0.23, 1.75) P=0.378 |

| Positive | 11 | 13 | ||

NLVA and HLA genotype

Titres of NLVA were not found to be associated with any of the HLA DQ2/8, DQ8/X, DQ2/2, DQ2/X and DQX/X genotypes in patients or controls.

NLVA compared to RBA LVA and SMIA

The samples in the present study were previously analysed for LVA by radiobinding assay (RBA) [11] and by suspension multiplex immunoassay (SMIA) performed with five different LV peptides and 22 virus peptides [13]. NLVA were not found to be associated with the LVA tested by RBA neither in the controls, nor in the type 1 diabetes patients (data not shown). NLVA were associated with SMIA against the LVVP1 31–60 peptide (LV VP1 31–60A) in the control subjects (P=0.029) but not in the type 1 diabetes patients (P=0.898).

DISCUSSION

A neutralization test for Ljungan virus antibodies (LVA) was successfully established using an assay format previously developed to detect neutralizing antibodies against poliovirus [18]. An important observation was that vero cells were readily infected by the LV strain 87–012 and that cytopathic effects were effectively detected. This made it possible to clearly detect NLVA above a negative threshold of 2.5 log2.

To our knowledge, this is the first study of NLVA based on the LV strain 87–012. In our previous studies, using the same samples as in the present study, we used RBA to detect LVA and demonstrated that levels of LVA fluctuated with season and were associated with type 1 diabetes incidence rate, thus suggesting that past exposure to LV may be associated with the disease [11]. LVA was also detected by RBA in bank voles with diabetes [14] as well as in bank voles captured in the wild [10] but such sera are yet to be tested for NLVA. One of the strengths of the present study was that the NVLA results were consistent with earlier analyses of LVA by RBA and SMIA (12). The proportion of NLVA positives was comparable to the proportion of LV antibody positives: 27.6 % LVA detected in the RBA and 28.4 % LV-VP1_31–60A using the SMIA method [13]. In all the samples, LVA and LV-VP1_31–60A were both positive in 11 % (38 of 359) and both negative in 55 % (196 of 359). In the type 1 diabetes samples, LVA and LV-VP1_31–60A were both positive in 21 % (14 of 67) and both negative in 39 % (26 of 67). In general, neutralizing virus antibodies provide reliable evidence for a prior virus infection [18, 23, 24]. The positive correlation between NVLA positives and SMIA LV-VP1_31–60A positives suggests that children have been exposed to LV. In our study, a total of n=359 children were tested for NLVA. NLVA were detected in n=168 (47 %) of those children, suggesting that exposure to LV in that region of Sweden is not uncommon and comparable to Finland [25].

A weakness in the present study is that the controls and the type 1 diabetes patient samples were not collected at the same time. Thus, our data does not allow us to study if there is an association between NVLA and seasonal variation. It is also noted that the time period for the patients (2005–2011) and controls do not overlap. A potential secular variation in infection can therefore not be excluded. Another weakness is that the controls were older than the patients. As such, future investigations need to take into account that exposure may vary by age.

An additional weakness is the possibility that the NLVA may cross-react with antibodies induced by other Ljungan virus infections. A total of five strains of LV (now referred to as Parechovirus B) are reported: LV strains 87–012 (genotype 1), 145SL (genotype 2), M1146 (genotype 3), 64–7855 (genotype 4) and Fuz1 (genotype 5) [7, 26] (https://www.picornaviridae.com/sg4/parechovirus/parechovirus.htm). The amino acid sequence in the VP1 capsid protein was found to vary extensively between the different LV strains [27]. As the single 87–012 strain was tested, we can only speculate to what extent there might be cross-reactive neutralizing antibodies. Without knowing the neutralizing antibody epitopes, it cannot be excluded that amino acid variations could exist in regions of the protein not accessible to antibodies. Additional studies would need to be conducted with specific monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies to resolve this issue.

In our previous investigation we tested VP peptides from LV representing amino acid residues 31–60 and 568–597, in addition to three peptides of the polyprotein [28]. Only the VP31–60 correlated with the LV RBA [28]. Further studies of VP peptides from different LV genotypes may reveal a potential cross reactivity between LV antibodies.

In a study from southern Sweden, LVA levels in a younger group of type 1 diabetes patients were found to be associated with high-risk HLA DQ2/8, 8/8 and 8/X genotypes, and with insulin autoantibodies (IAA) [12]. In the present study, the proportion of NLVA positive subjects was higher in type 1 diabetes patients compared to controls. We did not observe an association between NLVA positivity and HLADQ2/8, DQ8/X, DQ2/2, DQ2/X or DQX/X genotypes in type 1 diabetes patients.

The association between NLVA positivity and GADA may be interpreted as evidence that LV could be a trigger of beta cell autoimmunity (etiological agent) as has been suggested for other viruses [29, 30]. Recent data in TEDDY [31–33] and Diabetes Prediction and Prevention (DIPP) [34] studies suggest that the type 1 diabetes aetiology is related to the appearance of either IAA or GADA as the first appearing autoantibody. The incidence rate of IAA-first peaks at 1–3 years of age and declines thereafter, while that of GADA-first reaches a plateau at 3 years of age without a decline [35, 36]. Coxsackievirus has previously been reported to accelerate the pathogenesis of beta cell loss leading to a clinical onset of diabetes [37]. We interpret our findings to indicate LV may have a similar effects as those observed with coxsackievirus. It can therefore not be excluded that LV may be a trigger of a first appearing islet autoantibody to mark an induction of islet autoimmunity. Longitudinal studies from birth as reported for coxsackie B virus serology in the Finnish DIPP study [38] and virome sequencing in the TEDDY study [30] would be needed to explore the possibility that LV may be added to the list of potential virus contributing to islet beta cell autoimmunity. Parechovirus 1–6 were found in the stool samples but their frequency did not differ in the nested case control study [30]. Studies in children followed from birth will be needed to determine whether early exposure to LV plays a role in triggering either IAA-first, GADA-first, both, or neither. It cannot be excluded that LV may contribute to accelerate the pathogenic process resulting in diabetes [37]. In Finnish children there was no association between LV and human parechovirus antibodies detected by immunofluorescence and clinical onset of type 1 diabetes [25].

We conclude from the present study that NLVA is readily detected in both patient and control sera. These findings provide evidence for human infection with LV.

Furthermore, NLVA were also found to be associated with GADA in the type 1 diabetes patients. Recent data from the DIPP study in Finland suggests that the virome may contain a number of virus elements that may potentially be linked to, or are, the triggering event [39]. The present method to detect NLVA should prove useful for the analysis of blood samples taken from children followed from birth in studies such as DIPP, Diabetes Autoimmunity Study on the Young (DAISY), BABYDIAB, and TEDDY, prior to the first appearing beta cell autoantibody. The question whether LV could be, or is, an etiological trigger of beta cell autoimmunity remains to be answered.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and healthy controls for donating blood samples. We also thank William Weldon for facilitating the visit by Annika Lundstig to the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC in Atlanta, GA. Early versions of the manuscript were kindly reviewed by Dr William Osborne.

Funding information

This study was financially supported by grants awarded to Annika Lundstig by the following foundations: The Swedish Child Diabetes Foundation, Stiftelsen Olle Engkvist Byggmästare, Sydvästra Skånes Diabetesförening, Lisa and Johan Grönbergs Stiftelse, Lunds Revisorer, Sven Mattssons Stiftelse, The Family Ernfors Fund and HKH Kronprinsessan Lovisas förening för barnasjukvård / Stiftelsen Axel Tielmans Minnesfond. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Abbreviations:

- BABYDIAB

study on children born to parents with type 1 diabetes

- DAISY

diabetes autoimmunity study on the young

- DIPP

The type 1 diabetes prediction and prevention study

- GADA

glutamic acid decarboxylase

- IA-2A

autoantibodies against islet antigen-2

- IAA

autoantibodies against insulin

- LV

Ljungan virus

- LVA

Ljungan virus antibodies

- NLVA

neutralizing Ljungan virus antibodies

- RBA

radiobinding assay

- SMIA

suspension multiplex immunoassay

- TEDDY

the environmental determinants of diabetes in the young

- ZnT8QA

ZnT8-Glutamine

- ZnT8RA

zink transporter ZnT8-Arginine

- ZnT8WA

ZnT8-Tryptophan

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical statement

All samples were obtained after informed consent from patients and parents. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden.

References

- 1.Niklasson B, Kinnunen L, Hornfeldt B, Horling J, Benemar C. A new picornavirus isolated from bank voles (Clethrionomys glareolus). Virology 1999;255:86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johansson S, Niklasson B, Maizel J, Gorbalenya AE, Lindberg AM. Molecular analysis of three Ljungan virus isolates reveals a new, close-to-root lineage of the Picornaviridae with a cluster of two unrelated 2A proteins. J Virol 2002;76:8920–8930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johansson ES, Niklasson B, Tesh RB, Shafren DR, Travassos da Rosa AP. Molecular characterization of M1146, an American isolate of Ljungan virus (LV) reveals the presence of a new LV genotype. J Gen Virol 2003;84:837–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Niklasson B, Hultman T, Kallies R, Niedrig M, Nilsson R. The BioBreeding rat diabetes model is infected with Ljungan virus. Diabetologia 2007;50:1559–1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hauffe HC, Niklasson B, Olsson T, Bianchi A, Rizzoli A. Ljungan virus detected in bank voles (Myodes glareolus) and yellow-necked mice (Apodemus flavicollis) from Northern Italy. J Wildl Dis 2010;46:262–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salisbury AM, Begon M, Dove W, Niklasson B, Stewart JP. Ljungan virus is endemic in rodents in the UK. Arch Virol 2014;159:547–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitake H, Fujii Y, Nagai M, Ito N, Okadera K. Isolation of a sp. nov. Ljungan virus from wild birds in Japan. J Gen Virol 2016;97:1818–1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fevola C, Rossi C, Rosso F, Girardi M, Rosà R, et al. Geographical distribution of LJUNGAN virus in small mammals in Europe. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2020;20:692–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niklasson B, Hornfeldt B, Lundman B. Could myocarditis, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, and Guillain-Barre syndrome be caused by one or more infectious agents carried by rodents? Emerg Infect Dis 1998;4:187–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warvsten A, Bjornfors M, Arvidsson M, Vaziri-Sani F, Jonsson I. Islet autoantibodies present in association with Ljungan virus infection in bank voles (Myodes glareolus) in northern Sweden. J Med Virol 2017;89:24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nilsson A-L, Lagerquist E, Lynch KF, Lernmark A, Rolandsson O. Temporal variation of Ljungan virus antibody levels in relation to islet autoantibodies and possible correlation to childhood type 1 diabetes. Opn Pediatr Med J 2009;3:61–66. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nilsson AL, Vaziri-Sani F, Andersson C, Larsson K, Carlsson A. Relationship between Ljungan virus antibodies, HLA-DQ8, and insulin autoantibodies in newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes children. Viral Immunol 2013;26:207–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nilsson AL, Vaziri-Sani F, Broberg P, Elfaitouri A, Pipkorn R. Serological evaluation of possible exposure to Ljungan virus and related parechovirus in autoimmune (type 1) diabetes in children. J Med Virol 2015;87:1130–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niklasson B, Heller KE, Schonecker B, Bildsoe M, Daniels T. Development of type 1 diabetes in wild bank voles associated with islet autoantibodies and the novel ljungan virus. Int J Exp Diabesity Res 2003;4:35–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niklasson B Current views on Ljungan virus and its relationship to human diabetes. J Med Virol 2011;83:1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaaskelainen AJ, Kolehmainen P, Voutilainen L, Hauffe HC, Kallio-Kokko H. Evidence of Ljungan virus specific antibodies in humans and rodents. J Med Virol 2013;85:2001–2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jaaskelainen AJ, Voutilainen L, Lehmusto R, Henttonen H, Lappalainen M. Serological survey in the Finnish human population implies human-to-human transmission of Ljungan virus or antigenically related viruses. Epidemiol Infect 2016;144:1278–1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weldon WC, Oberste MS, Pallansch MA. Standardized methods for detection of poliovirus antibodies. Methods Mol Biol 2016;1387:145–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harrison CJ, Weldon WC, Pahud BA, Jackson MA, Oberste MS. Neutralizing antibody against enterovirus D68 in children and adults before 2014 outbreak, Kansas City, Missouri, USA. Emerg Infect Dis 2019;25:585–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delli AJ, Vaziri-Sani F, Lindblad B, Elding-Larsson H, Carlsson A. Zinc transporter 8 autoantibodies and their association with SLC30A8 and HLA-DQ genes differ between immigrant and Swedish patients with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes in the Better Diabetes Diagnosis study. Diabetes 2012;61:2556–2564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaziri-Sani F, Delli AJ, Elding-Larsson H, Lindblad B, Carlsson A. A novel triple mix radiobinding assay for the three ZnT8 (ZnT8-RWQ) autoantibody variants in children with newly diagnosed diabetes. J Immunol Methods 2011;371:25–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abadie A Bootstrap tests for distributional treatment effects in instrumental variable models. J Am Stat Assoc 2002;97:284–292. [Google Scholar]

- 23.CK Y, Chen CC, Chen CL, Wang JR, Liu CC. Neutralizing antibody provided protection against enterovirus type 71 lethal challenge in neonatal mice. J Biomed Sci 2000;7:523–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Westerhuis BM, Benschop KSM, Koen G, Claassen YB, Wagner K, et al. Human memory B cells producing potent cross-neutralizing antibodies against human parechovirus: Implications for prevalence, treatment, and diagnosis. J Virol 2015;89:7457–7464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jääskeläinen AJ, Nurminen N, Kolehmainen P, Smura T, Tauriainen S, et al. No association between Ljungan virus seropositivity and the beta-cell damaging process in the finnish type 1 diabetes prediction and prevention study cohort. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2019;38:314–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tolf C, Gullberg M, Johansson ES, Tesh RB, Andersson B. Molecular characterization of a novel Ljungan virus (Parechovirus; Picornaviridae) reveals a fourth genotype and indicates ancestral recombination. J Gen Virol 2009;90:843–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tolf C, Gullberg M, Ekstrom JO, Jonsson N, Michael Lindberg A. Identification of amino acid residues of Ljungan virus VP0 and VP1 associated with cytolytic replication in cultured cells. Arch Virol 2009;154:1271–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nilsson AL, Vaziri-Sani F, Broberg P, Elfaitouri A, Pipkorn R. Serological evaluation of possible exposure to Ljungan virus and related parechovirus in autoimmune (type 1) diabetes in children. J Med Virol 2015;87:1130–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hyoty H Viruses in type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes 2016;17:56–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vehik K, Lynch KF, Wong MC, Tian X, Ross MC. Prospective virome analyses in young children at increased genetic risk for type 1 diabetes. Nat Med 2019;25:1865–1872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krischer JP, Lynch KF, Schatz DA, Ilonen J, Lernmark A. The 6 year incidence of diabetes-associated autoantibodies in genetically at-risk children: the TEDDY study. Diabetologia 2015;58:980–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krischer JP, Liu X, Å L, Hagopian WA, Rewers MJ. The influence of type 1 diabetes genetic susceptibility regions, age, sex, and family history on the progression from multiple autoantibodies to type 1 diabetes: A TEDDY study report. Diabetes 2017;66:3122–3129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krischer JP, Liu X, Vehik K, Akolkar B, Hagopian WA, et al. Predicting islet cell autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes: An 8-year TEDDY study progress report. Diabetes Care 2019;42:1051–1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ilonen J, Hammais A, Laine AP, Lempainen J, Vaarala O. Patterns of beta-cell autoantibody appearance and genetic associations during the first years of life. Diabetes 2013;62:3636–3640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krischer JP, Liu X, Lernmark A, Hagopian WA, Rewers MJ. The influence of type 1 diabetes genetic susceptibility regions, age, sex, and family history to the progression from multiple autoantibodies to type 1 diabetes: a TEDDY study report. Diabetes 2017;66:3122–3129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krischer JP, Lynch KF, Lernmark Å, Hagopian WA, Rewers MJ, et al. Genetic and environmental interactions modify the risk of diabetes-related autoimmunity by 6 years of age: The TEDDY study. Diabetes Care 2017;40:1194–1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stene LC, Oikarinen S, Hyoty H, Barriga KJ, Norris JM. Enterovirus infection and progression from islet autoimmunity to type 1 diabetes: the Diabetes and Autoimmunity Study in the Young (DAISY). Diabetes 2010;59:3174–3180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sioofy-Khojine AB, Lehtonen J, Nurminen N, Laitinen OH, Oikarinen S. Coxsackievirus B1 infections are associated with the initiation of insulin-driven autoimmunity that progresses to type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 2018;61:1193–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao G, Vatanen T, Droit L, Park A, Kostic AD. Intestinal virome changes precede autoimmunity in type I diabetes-susceptible children. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017;114:E6166–E6175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]