Abstract

Forward genetics begins with a biological phenotype, and attempts to identify genetic changes that influence that phenotype. These changes can be induced in a selected group of genes, for instance, by using using libraries of cDNAs, shRNAs, CRISPR guide RNAs, or genetic suppressor elements (GSEs), or randomly throughout the genome, by using chemical or insertional mutagens, with each approach creating distinct genetic changes. The Validation-Based Insertional Mutagenesis (VBIM) strategy utilizes modified lentiviruses as insertional mutagens, placing strong promoters throughout the genome. Generating libraries of millions of cells which carry one or a few VBIM promoter insertions is straightforward, allowing selection of cells in which over expression of VBIM-driven RNAs or proteins promote the phenotype of interest. VBIM-driven RNAs may encode full-length proteins, truncated proteins (which may have wild-type, constitutive, or dominant-negative activity), or antisense RNAs that can disrupt gene expression. The diversity of VBIM-driven changes allows for the identification of both gain-of-function and loss-of-function mutations a single screen. Additionally, VBIM can target any genomic locus, regardless of whether it is expressed in the cells under study or known to have a biological function, allowing for true whole-genome screens without the complication and cost of constructing, maintaining, and delivering a comprehensive library. Here, we review the VBIM strategy and discuss examples in which VBIM has been successfully used in diverse screens to identify novel genes or novel functions for known genes. In addition, we discuss considerations for transitioning the VBIM strategy to in vivo screens. We hope that other laboratories will be encouraged to use the VBIM strategy to identify genes that influence their phenotypes of interest.

Keywords: forward genetics, insertional mutagenesis, lentiviral vectors, cell libraries, in vivo screens, drug resistance

INTRODUCTION

Forward genetics begins with a biological phenomenon or characteristic, and seeks to associate a specific genetic change, induced randomly by any number of methods, with that phenomenon. Forward genetics has been used to uncover novel genes in diverse biological systems, including bacteria, fungi, roundworms, flies, fish, mice, and mouse and human cell cultures to uncover genes involved in development, cell death and survival, proliferation, and mechanisms of resistance to therapies, among others.

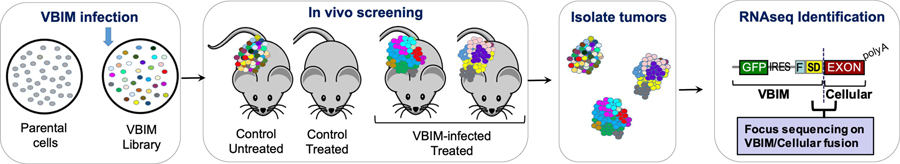

There are three major steps in a typical forward genetic screen: (1) create random genetic changes, (2) apply a selective pressure or screen to isolate mutants in which the biological phenomenon of interest has been altered, and (3) identify, confirm, and characterize the nature of the genetic change within the mutant cells. Regarding step 1, mutations can be induced throughout the genome by using chemical mutagens (N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea, ICR 191) or insertional mutagens (retroviruses, transposons). More selective alterations can be achieved upon delivery of libraries of cDNAs, siRNA/shRNAs, CRISPR guide RNAs, or genetic suppressor elements (GSEs), with each approach creating distinct genetic changes (Figure 1). Each method has advantages and disadvantages that should be considered when developing a forward genetics screen or selection, including the biological question being assessed, the model system, the desired types of mutations, and the budget and scale of the proposed selection or screen. Intrigued by the rich history of insertional mutagenesis in gene discovery, we developed the Validation-Based Insertional Mutagenesis (VBIM) strategy for use in forward genetic experiments (Lu et al., 2009).

Figure 1. Overview of forward genetics screening protocols.

In screens using human or mouse cells, genetic changes can be induced by chemical mutagens, insertional mutagens, or delivery of libraries of cDNAs, shRNAs, or CRISPR-sgRNAs. Following mutagenesis, each cell in the library has a unique genetic change. The cell libraries can be screened for a mutant phenotype, in which rare mutations allowed some cells to survive, thrive, and grow when most other cells are eliminated from the population. The mutation can be identified, and the list of candidate genes can be prioritized and characterized using traditional reverse genetic approaches. Following infection with the VBIM lentiviruses, integration can result in a number of possible alterations (see “VBIM insertion” insert). Examples shown include: (i) insertion in or near the endogenous promoter, potentially causing the over expression of a full-length RNA that may give rise to a full-length protein (if in a coding region) or a full-length lncRNA (if in a non-coding gene); (ii) insertion within an intron of a coding or non-coding gene in the sense orientation, resulting in a truncated RNA that could encode a truncated protein or lncRNA (which may have normal, constitutive, or dominant-negative activity); and (iii) insertion within an intron of a coding or non-coding gene in the antisense orientation, probably reducing efficient transcription from the endogenous promoter. Other possible integrations, such as those in intergenic regions or repetitive transcribed elements, are not shown.

The strategy uses modified lentiviuses to place strong promoters throughout the genome, which then act as insertional mutagens (Figure 1). There are a number of advantages to using the VBIM method over chemical mutagens and library-based approaches. First, insertional mutagens can utilize the entirety of the genome. This is increasingly important as advances in deep-sequencing technologies have revealed an unexpected genomic diversity, beyond the protein coding regions. For example, interrogation of more than 7,000 RNA-seq data sets from human tumors, normal tissues, and cell lines revealed that, in addition to the 2% of the genome that is devoted to protein coding regions, nearly 80% of the genome is transcribed into RNA (Iyer et al., 2015). The nearly 400,000 transcripts identified in this study were assembled into a “consensus human transcriptome”, encompassing more than 91,000 expressed genes. Approximately 60,000 of these genes were classified as long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs); nearly 80% of these lncRNA had not been previously annotated. While chemical mutagens also allow screening of the entire genome, library-based approaches (cDNA, shRNA, CRISPR, GSEs) lack most of the expressed genes described in the study above. Strategies like VBIM could thus help identify how these recently appreciated non-coding RNAs influence biological phenotypes commonly assessed using forward genetic screens. A second advantage of the VBIM strategy is that a single screen or selection can identify both gain-of-function and loss-of-function mutations, whereas library-based screens can only identify either gain- or loss-of-function mutations in each screen. The reason for this is rooted in the diverse types of genetic changes that can be induced following VBIM integration. The strong VBIM promoter can induce the expression of RNAs encoding a full-length RNA or protein, or expression of an alternative RNA or truncated protein (which may have wild-type, constitutive, or dominant-negative activity). Additional mutations include antisense insertions that could disrupt gene expression or produce an antisense RNA (Figure 1). Third, screening with VBIM-lentiviruses is simple and straightforward, and can be performed in nearly any research laboratory that uses standard lentiviruses. There is no need to construct, purchase, or maintain complex genome-wide libraries (cDNA, shRNA, CRISPR, GSEs), putting forward genetic screening approaches in the hands of most researchers. Finally, the VBIM approach has enhanced the efficiency of insertional mutagenesis protocols by allowing investigators to validate that the mutant phenotype is dependent on the inserted promoter’s activity, by either excising or silencing the VBIM-promoter from mutant cells and re-testing the mutant to determine whether the phenotype has reverted to normal. The ability to convincingly show that an identified mutant is dependent on the inserted VBIM promoter’s activity minimizes the wasteful pursuit of spontaneous mutants.

In this review, we discuss the VBIM strategy and the important factors one should consider if interested in setting up a VBIM screen. We also discuss discoveries made by using the approach, and how advances in the method facilitate new screening modalities, such as screens conducted in animal models. While we focus here on the use of forward genetic approaches in mammalian cell culture models, especially human and mouse cell lines, to discover genes that influence cancer cell biology and responses to cancer therapies, the discussion is relevant for anyone interested in forward genetic screening.

THE VBIM STRATEGY

Components of the VBIM Lentiviruses.

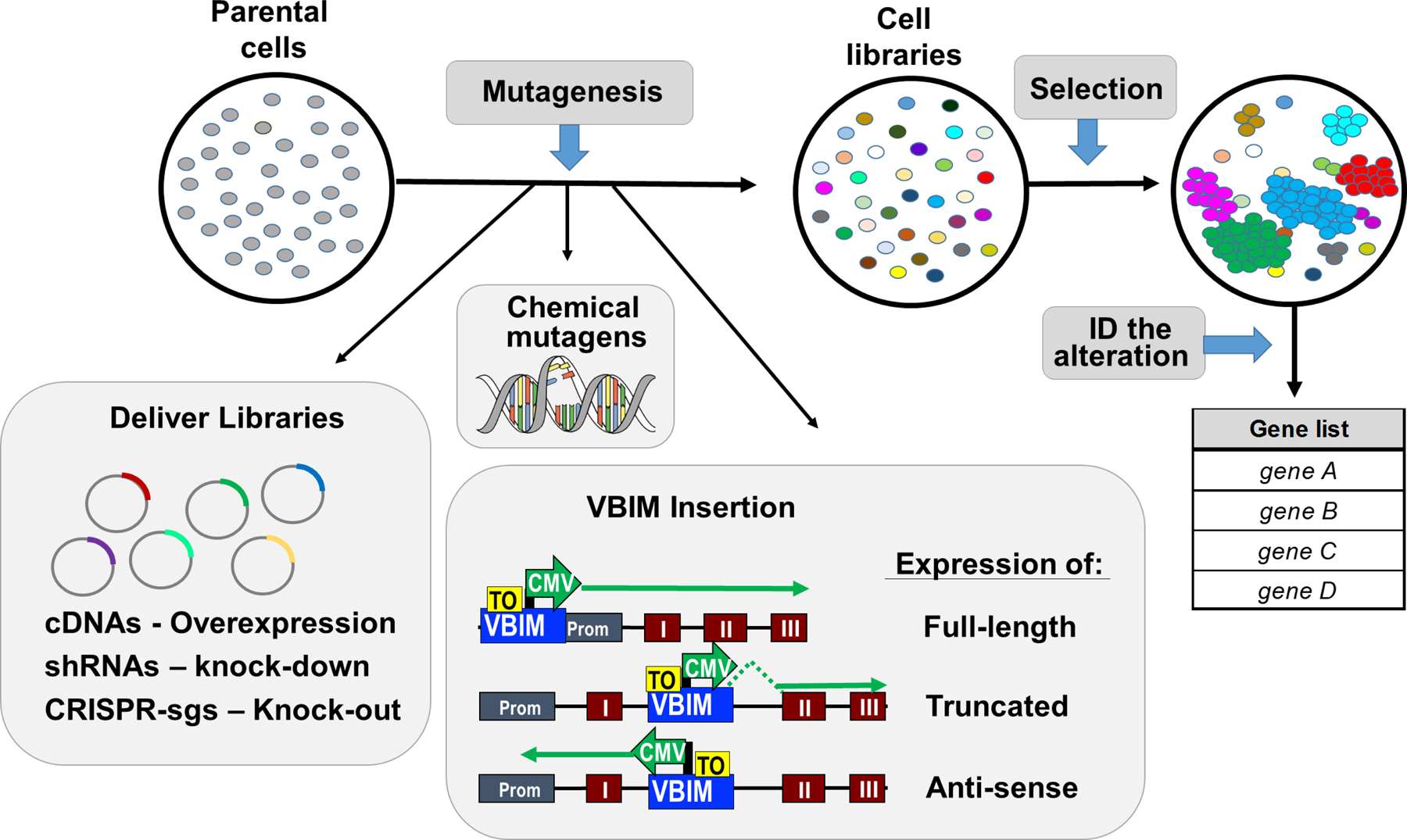

The VBIM strategy utilizes a modified lentiviral (LV) backbone developed to act as an insertional mutagen (Figure 2A). The use of VSV-G pseudotyped lentiviruses to deliver the mutagenic VBIM promoter allows infection of most species and cell types, whether they are proliferating or not. Figures 2B and 2C illustrate an integrated VBIM provirus and the products of promoter-mediated transcription and translation. A full-length CMV promoter was chosen for VBIM because it is highly active in most cell types and maintains fairly stable expression over time. However, the VBIM vector is designed so that the CMV promoter can be easily exchanged for another promoter if the CMV promoter is less active or problematic in a specific biological system. Because the LTRs are self-inactivating (they have no promoter activity), and because the polyadenylation signals have also been deleted, transcription initiated from the integrated VBIM CMV promoter reads through the viral sequence into the neighboring cellular genome (Lu et al., 2009). Importantly, the activity of the CMV promoter can be regulated by introducing the binding of the TR-KRAB fusion protein to an upstream tet-operator (TO) element. In this case, and in the absence of doxycycline, TR-KRAB is highly repressive, shutting off CMV promoter activity (Figure 2D). In the presence of doxycycline, TR-KRAB is inactivated and unable to bind the TO and repress the CMV promoter; thus, the CMV is fully functional. In addition, LoxP sites in the LTRs of the integrated VBIM provirus permit Cre-mediated removal of the VBIM provirus, leaving behind only 238 nucleotides of presumably inert LTR sequence (depending on the location of the VBIM insertion) (Figure 2E). By silencing or removing the inserted CMV promoter, one can validate that the mutant phenotype is dependent on the inserted VBIM promoter, preventing further analysis of spontaneous mutants that are inherent in most screens.

Figure 2. Components of the VBIM lentiviruses.

Illustration of the VBIM lentiviral vector backbone (A) and the components of the VBIM provirus, following integration into the infected cells genome (B). The 3’ self-inactivating (SIN) LTR was mutated to delete the viral polyadenylation signal (denoted by *) and a LoxP site was included. Following infection of target cells, reverse transcription copies the self-inactivating 3’LTR, such that the provirus LTRs integrated in the genome have no promoter activity and no polyadenylation signal; also, the entire VBIM cassette is flanked by LoxP sites. Transcription from the integrated VBIM CMV promoter creates an RNA that includes the GFP (green fluorescent protein) cDNA, an IRES (internal ribosome entry site), a FLAG epitope tag, and a splice donor that results in splicing of the VBIM RNA (GFP-IRES-FLAG-SD) into downstream exons. (C) If the VBIM integration occurs in an intron, the CMV-driven RNA results in a VBIM/cellular mRNA fusion that encodes GFP and, if the targeted gene is coding, a FLAG-tagged cellular protein; if the VBIM insertion is not in a coding region or occurs in the antisense orientation, only GFP would be expressed. (D) Addition of TR-KRAB, a tetracycline/doxycycline-regulated protein, allows for regulated expression of the VBIM CMV promoter and the VBIM/cellular mRNA and encoded proteins. (E) Upon addition of Cre recombinase, all but 238 nucleotides of the VBIM provirus will be deleted, leaving only a SIN LTR with no promoter or polyadenylation signal. (F) Three different reading frames of FLAG-SD were created as separate constructs, VBIM-SD1, VBIM-SD2, and VBIM-SD3, differing by 1 nucleotide each (note the purple T, TT, or TTT). The FLAG epitope is embedded just upstream of the splice donor site, so that one of the VBIM-SD reading frames can properly splice into each splice acceptor to give rise to a potential FLAG-tagged fusion protein. An example of a VBIM-SD1 insertion into intron 7 of FRK (Fyn-related Kinase) demonstrates how splicing would create an in-frame FLAG fusion with the C-terminus of the FRK protein (encoding FRK 338–512). VBIM-SD2 and VBIM-SD3 would splice properly with exon 8 of FRK, but would be out-of-frame with the FRK C-terminus. See text for details.

Downstream of the CMV promoter are a number of functional elements. The most important one is an unpaired splice donor (SD) site, which directs splicing of the CMV-driven VBIM RNA to a downstream exon to create a VBIM/cellular mRNA fusion (Figures 2C & 2E; (Lu et al., 2009)). An internal GFP (green fluorescent protein) reporter gene is immediately downstream of the CMV promoter, and an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) downstream of GFP allows the translation of a cellular protein (either full length or truncated) encoded by the VBIM/cellular RNA fusion protein. A FLAG epitope is embedded just upstream of the splice donor site, to allow epitope tagging of any protein encoded by the cellular exons located 3’ of the insertion site (Figures 2C & 2E). When taken together, a VBIM integration into the genome, and the resulting transcription from the CMV promoter, create an RNA that includes the GFP cDNA, an IRES, a FLAG epitope, and a splice donor, in addition to the cellular genetic material located 3’ of the VBIM insertion. If insertion occurs in an intron of a coding or non-coding gene, the VBIM RNA (GFP-IRES-FLAG) will splice into downstream exons to create VBIM/cellular fusion RNAs. Three different reading frames of FLAG-SD are present in separate constructs, called VBIM-SD1, 2, and 3, so that each splice acceptor site in the genome can potentially function to allow the synthesis of a FLAG-tagged fusion protein (if integration occurs in a coding region). As an example, we show a VBIM-SD1 insertion into intron 7 of FRK (Fyn-related Kinase), which results in the proper splicing into exon 8 to encode a FLAG-tagged FRK truncation encoding amino acids 328–512; insertion of VBIM-SD2 or 3 would be out-of-frame with the C-terminal of FRK (Figure 2E)

Creation of VBIM mutations in a population of cells

Millions of cells can be readily infected with the VBIM lentiviruses to generate a library in which most cells incorporate one or more unique insertions (Figure 1). In terms of the types of mutations the VBIM-lentiviruses create, prior studies have identified that lentiviruses integrate throughout genes, usually avoiding promoter regions. This property contrasts with another commonly used insertional mutagen, murine leukemia viruses (MLV), which tends to preferentially target promoters (G. P. Wang, Ciuffi, Leipzig, Berry, & Bushman, 2007; Wu, Li, Crise, & Burgess, 2003). Based on these findings, we hypothesized that lentiviruses would result in greater numbers of VBIM integrations throughout gene bodies rather than near gene promoters, increasing the potential for gene truncations (when in the sense orientation) and gene disruptions (when in the antisense orientation), compared to MLV mutagenesis. This has largely held true in the screens we have performed thus far, as discussed below.

Regarding the number of integrations one should aim for in a screen, studies of lentiviral integrations again provide insight. We expect that ~75% of the VBIM-lentivirus integrations will occur within genes. Based on this, we estimate that about 120,000 VBIM integrations are needed to target each of the ~91,000 human genes once. As stated above, this estimate includes both coding and non-coding RNAs, which contain introns and exons and are processed similarly to protein-coding genes ((Iyer et al., 2015). However, one would want to ensure that each gene is targeted many times, because different integration events in the same gene will give rise to different, and perhaps unique, products, only some of which may confer a phenotype when expressed at a high level. For instance, VBIM insertion in or around an endogenous promoter region could cause increased expression of an RNA encoding either a full-length or nearly full-length protein, which retains wild-type function. Alternatively, insertion into the center of a gene could create a truncated protein (if inserted in the sense orientation), which may have wild-type, constitutive, or dominant-negative activity (Figure 1). Finally, integration of the CMV promoter in an antisense orientation (directed towards the endogenous promoter) may disrupt expression from the gene it is inserted into, and may also create an antisense transcript that disrupts translation of the RNA product of the unaltered allele. We generally set up screens by planning for ~50X genome coverage, involving ~6 million (120,000 × 50) VBIM integrations, if using human cells. We note, however, that some of our novel discoveries were made by using comparatively small libraries. For example, the discovery of FAM83 oncogenes discussed below was made by screening only ~360,000 integrations in a pilot experiment (R. Cipriano et al., 2012). Thus, we do not expect that genome saturation will be required to identify novel genes in a screen or selection. Rather, we recommend greater coverage if it is feasible within the proposed model system to identify all potential genes involved in the biology of interest.

From our experience, we recommend using a larger number of independent VBIM libraries, with fewer cells, rather than a smaller number of larger libraries. For a genome screen of ~6 million VBIM integrations, as described above, the use of 20 independent libraries, each harboring 300,000 VBIM integrations, is preferable to 3 independent pools harboring 2 million VBIM integrations each. Imagine that the screen of 6 million integrations yields 10 VBIM-driven mutants, or one mutant per every 600,000 integrations tested. With 20 independent libraries, one can be certain that each positive library (those that produce the mutant phenotype) has at least 1 VBIM-driven mutation that is independent from mutations in the other libraries. In this example, if 10 of the libraries are positive, there will be at least 10 independent mutants. In contrast, if you use 3 independent libraries harboring 2 million VBIM integrations each, then all 3 libraries are expected to be positive, but you would be unaware of whether you had identified 3 mutants (1 per library) or 10 mutants (3+ per library). Finally, we have typically controlled viral titers so that each cell has between 1–2 VBIM integrations, as fewer integrations make identification of VBIM-altered gene in the mutants more manageable. However, if needed, titers can be increased to increase the number of integrations within each cell, so that a greater number of VBIM integrations can be screened using fewer cells. For example, 6 million integrations could be assessed in a library size of 6 million cells (with 1 VBIM integration/cell) or 600,000 cells (with 10 VBIM integrations/cell). The caveat of using increasing number of integrations per cell is that all VBIM-driven mutations identified would need to be assessed to be certain which one caused the phenotypic change.

Screening for a mutant phenotype

Following the development of the VBIM libraries, a selective pressure of choice is applied to the populations, and the cells that survive and/or continue to thrive are isolated for further characterization; the variant cells are called mutants. As described in detail below, we have performed a number of diverse screens/selections in cultured cancer cells using the VBIM approach, including screening an NFkB reporter cell line, selection for resistance to taxanes and tamoxifen in breast cancer cells, selection for resistance to erlotinib or fractionated ionizing radiation in lung cancer cells, selection for resistance to quinacrine in colorectal cancer cells, selection for the transformation of mammary epithelial cells by anchorage-independent growth, and selection for escape from metastatic dormancy in organotypic culture. In most of these examples, individual clones were isolated after selection, and the CMV-promoter dependence was validated by using TR-KRAB regulation and/or Cre-mediated excision. Then, the insertion sites were identified. More recently, we have performed a selection for resistance to immune checkpoint inhibition in vivo using animal models, taking advantage of high-throughput sequencing capabilities to identify VBIM insertion sites. Some of the unique variables that should be considered when moving a forward genetics screen into animal models in vivo are discussed below.

Identifying the VBIM-targeted gene

Each VBIM integration into the genome can be mapped using classical insertion site mapping techniques, such as inverse PCR or splinkerette-mediated PCR of genomic DNA, as previously described (R. Cipriano et al., 2012) One of the advantages of the insertional mutagens over chemical mutagenesis is that insertional mutagens tag the genetic sequences they have altered, making identification of the targeted genes generally straightforward. In addition to tagging the genomic location, each successful VBIM insertion also gives rise to a VBIM/cellular gene fusion RNA originating from the CMV promoter. Therefore, one can readily identify the target gene(s) from the sequence of cellular RNA that is connected to the known VBIM sequence (Figures 2C & 2E). Cloning VBIM/cellular fusion RNAs was originally performed using nested RT-PCR with VBIM-specific and anchored poly(T) primers (De, Dermawan, & Stark, 2014) but, more recently, we have used RNA-Seq to identify and map VBIM insertion sites. Standard paired-end 150 bp high throughput sequencing with Illumina NovaSeq 6000 or a similar platform is sufficient to identify VBIM-linked transcripts. Sequencing reads can be filtered for those containing the VBIM sequence, and the unknown sequences fused at the VBIM-splice donor can be identified using bioinformatic tools, such as Nucleotide BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool). Based on the BLAST output, the orientation of the VBIM insertion can be mapped and a prediction made about the potential outcome of the insertion, as described above and in Figure 3 (i.e. the VBIM RNA encodes a full-length protein, truncated protein, antisense mRNA, etc.). When examining an individual mutant, RNA-seq will identify all possible VBIM/cellular fusions within the mutant, as well as their relative abundance. Once the insertion sites are identified and the products predicted, mutations can be modeled and validated in naïve cells. For instance, the VBIM-driven products (full-length or truncated) can be expressed in naïve cells, and the treatment and selection repeated, to validate the involvement of the VBIM/cellular fusion product in the phenotype. Conversely, if an anti-sense RNA is predicted, then an shRNA or CRISPR/Cas9 knock-out can be established and tested in naïve cells. If there are multiple predicted VBIM insertions in the same mutant, then selected candidate genes would need to be prioritized based on expression level or other factors, or each candidate would need to be tested individually. Once a gene has been identified as a novel regulator of the phenotype of interest, classical reverse genetic approaches are utilized to determine its mechanism of action.

Figure 3. Identification of VBIM-targeted genes by RNA-Seq.

(A and B) RNA-Seq data from individual clones or populations of selected cells can be filtered for those containing known VBIM RNA sequences (depicted as blue regions of the RNA-seq reads) and the attached cellular sequence identified using Nucleotide BLAST. (C) The mutation can be predicted based on the identified cellular sequences. For example, when VBIM RNA-seq reads are attached to an exon of a coding or non-coding gene, the insertion would be predicted to be in the preceding intron, as shown for the VBIM-SD1 insertion into intron 7 of FRK (Fyn-related Kinase), also shown in Figure 2F.

DISCOVERIES MADE USING THE VBIM STRATEGY

Successful use of the VBIM strategy has identified novel regulators of diverse biological phenotypes, ranging from cancer biology (oncogene discovery and regulation, metastatic outgrowth, therapeutic resistance), to virus infection and to cholesterol synthesis pathways. As predicted, VBIM-driven mutations have been identified that encode full-length proteins, truncated proteins with wild-type activity or dominant-negative activity, and antisense insertions that disrupt gene expression. Here, we describe the models assessed using VBIM and the discoveries made.

Novel NFkB regulatory mechanisms

Constitutive NFκB activation is associated with a number of pathological conditions, including inflammation and cancer, and is well known to be involved in tumor angiogenesis and invasiveness (Tabruyn & Griffioen, 2008). Loss of the normal regulation of NFκB is a major contributor to the deregulated growth, resistance to apoptosis, and propensity to metastasize observed in many different cancers (W. Wang, Nag, & Zhang, 2015). We used VBIM to identify negative regulators of NFκB-mediated transcription in an NFkB reporter cell line. The F-box leucine repeat rich protein 11 (FBXL11), a lysine demethylase, was identified in this screen as a potent negative regulator of NFκB. To firmly establish the negative regulatory effect of FBXL11, we stably overexpressed this protein in naïve cells and transfected them transiently with a κB-luciferase reporter, finding that highly expressed FBXL11 decreased NFκB activity (Lu et al., 2009). This discovery led to the companion finding that the protein lysine methyltransferase NSD1 is a positive regulator of NFκB: high levels of NSD1 activate NFκB and reverse the inhibitory effect of FBXL11, whereas reduced expression of NSD1 decreases NF-κB activation. We determined that lysine residues K218 and K221 of p65 are methylated upon activation of NF-κB and demethylated by FBXL11. Methylation of K218 and K221 plays an important functional role in cell proliferation and colony formation in colon cancer cells (Lu et al., 2010). In summary, the use of the VBIM methodology led to the discovery of novel regulatory mechanisms for a highly important transcription factor responsible for regulating transcription programs in normal biology and numerous pathologies.

Identification of novel mechanisms of resistance to cancer therapies

Resistance to therapy remains a major barrier to the successful treatment of cancer. Increased expression of a single protein, often mediated by gene amplification, is a common mechanism of drug resistance in cancer (Matsui, Ihara, Suda, Mikami, & Semba, 2013; Ohshima et al., 2017). VBIM can be used to mimic this phenomenon by generating rare cells in a population in which a single protein that mediates resistance is highly expressed, in this case, due to CMV promoter insertion, and the selection of these cells at drug concentrations that kill non-resistant cells is straightforward. We have used this approach successfully in several different cancer types to identify novel resistance mechanisms to therapeutics, including erlotinib, taxanes, tamoxifen, quinacrine, and fractionated ionizing radiation (Bose & Ma, 2021; DeMichele, Yee, & Esserman, 2017).

The systemic therapy of breast cancer has seen many advances over the last few decades, with the introduction of taxanes, including paclitaxel and docetaxel (De Laurentiis et al., 2008). Taxanes, widely used in adjuvant and neoadjuvant therapeutic approaches in breast cancer, bind to microtubules to stabilize and prevent depolymerization, disrupting mitotic spindle formation, thus inhibiting cell division and leading to cell death. While taxanes are extremely successful in establishing cures or durable responses in breast cancer, drug resistance, manifested by relapse and tumor progression, remains a major challenge (DeMichele et al., 2017). To understand mechanisms underlying taxane resistance in breast cancer, we used VBIM to identify proteins whose overexpression confers resistance, discovering that increased expression of the kinesin KIFC3 confers resistance to docetaxel in triple negative breast cancer cells (De, Cipriano, Jackson, & Stark, 2009). Kinesins are motor proteins that transport cargoes along microtubule tracks (Hirokawa, Noda, Tanaka, & Niwa, 2009). KIFC3, and other kinesins such as KIFC1 and KIF5A, oppose the microtubule-stabilizing effect of docetaxel, and thus confer resistance to the drug (De et al., 2009). Consistent with clinical relevance of this mechanism, we showed that elevated kinesin expression correlates with specific taxane resistance in basal-like breast cancer patients (De et al., 2009; Tan et al., 2012).

Tamoxifen, a widely used modulator of the estrogen receptor (ER), targets ER-positive breast cancer preferentially. We used VBIM to find that expression of a dominant-negative (DN) truncated form of the protein ZIP, a subunit of the HDAC1 NuRD complex, confers resistance to tamoxifen in luminal breast cancer cells (Zhu et al., 2020). The mechanism by which the VBIM-driven DN-ZIP regulates tamoxifen resistance appears to involve upregulation of JAK/STAT3 activity (Zhu et al., 2020), as ZIP normally suppresses JAK2 activity to prevent STAT3 phosphorylation. Consistently, increased expression of wild-type ZIP inhibited the expression of genes whose products mediate tamoxifen resistance, thereby sensitizing cells to tamoxifen. In patients with ERα-positive breast cancer in which tamoxifen was used as an adjuvant treatment, higher ZIP expression was shown to correlate with a better prognosis, supporting the idea that ZIP expression may be a biomarker for predicting responses to estrogen receptor modulators (Zhu et al., 2020).

The same approach has been applied to a number of additional targeted cancer therapies. For example, in a screen in colon cancer cells for overexpressed proteins leading to resistance to quinacrine, a pleiotropic antimalarial compound that is also reported to target the histone chaperone FACT, the tyrosine kinase FER was identified. Elevated FER expression activates NFκB, which was otherwise found to be suppressed by quinacrine (Guo & Stark, 2011). Similarly, we found that the constitutive activation of NFκB in several cancer cell lines is decreased following EGFR inhibition (by genetic knockdown or using the ATP-site directed catalytic inhibitor erlotinib), indicating that EGFR is an important mediator of NFκB activation in cancer cells. To explore the molecular mechanisms connecting EGFR and NFkB, a screen for erlotinib resistance in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells was performed using the VBIM strategy. We identified that VBIM-driven expression of Son of Sevenless 1 (SOS1), a mediator of EGF-dependent pathways that facilitate cell growth and survival, increases NFκB activation, resulting in erlotinib resistance. In this way, SOS1 contributes to NFκB activation in cancer (De et al., 2014).

We identified two VBIM-driven proteins that confer resistance to ionizing radiation (IR) in NSCLC cells (De, Holvey-Bates, Mahen, Willard, & Stark, 2021). In this experiment, VBIM libraries were exposed to 3 rounds of IR, with expansion of the surviving cells after each round. VBIM-targeted RNAs were identified by high-throughput RNA-seq of the pooled RNAs from the entire surviving population, rather the individual mutants. Out of 143 million total reads, about 2000 contained the vector sequence fused to cellular RNAs. All VBIM-tagged sequences of more than 15 nucleotides were aligned to the human Ref-seq database. Two VBIM/cellular RNA fusions were substantially enriched in the resistant populations following selection: nicotinamide phosphoribosyl transferase (NAMPT) and the ubiquitin E3 ligase FBXO22, representing about 25% and 8% of the total VBIM/cellular RNA fusions identified in the resistant population, respectively. NAMPT is the rate-limiting enzyme in NAD biosynthesis, and NAMPT inhibitors enhance sensitivity to IR in cancer (Zerp, Vens, Floot, Verheij, & van Triest, 2014), indicating that VBIM-mediated overexpression of NAMPT probably mediates resistance to DNA damage. The VBIM-FBXO22 RNA encodes a truncated C-terminal fragment that was predicted to act in a dominant negative fashion. Consistently, increased expression of a cDNA encoding full-length FBXO22 significantly reduced cell survival in response to DNA damaging agents such as ionizing radiation and cisplatin (De et al., 2021). Further studies of NAMPT and FBXO22 are currently underway, but the results obtained so far highlight (i) the potential of using RNA-seq to identify VBIM/cellular RNA fusions from complex populations and (ii) the benefits of the VBIM strategy in identifying both gain-of-function and loss-of-function mutations in the same screen.

Identification of a novel oncogene family

The identification of genes involved in tumorigenesis can help discover new targeted therapeutics; such discoveries can be greatly facilitated by using phenotype-based forward genetic screens. The VBIM strategy was used to identify FAM83B (Family with Sequence Similarity 83, member B) as a novel oncoprotein capable of promoting the transformation of immortalized human mammary epithelial cells (HMEC), using anchorage-independent growth (AIG) in soft agar as the selective pressure (R. Cipriano et al., 2012). We found that VBIM-driven FAM83B was sufficient to promote HMEC transformation, similar to mutant RAS (R. Cipriano et al., 2012). The FAM83B gene was originally annotated as a RefSeq gene and included as a member of a hypothetical protein family (FAM83: FAMily with sequence similarity 83), based on the presence of an amino-terminal Domain of Unknown Function (DUF1669) conserved among a family of 8 FAM83 members. In addition to transforming cells itself, FAM83B participates in EGFR- and RAS-driven oncogenic transformation by facilitating the activation of MAPK and PI3K pathways. Elevated expression of FAM83B increases basal EGFR phosphorylation and downstream effector activation, resulting in resistance to a number of therapies targeting these pathways, including the EGFR, RAF, PI3K, AKT, and mTOR targeted therapies (Rocky Cipriano et al., 2013). FAM83B expression is elevated in a number of human cancers, including breast, bladder, testis, ovary, thyroid, and lung cancers (R. Cipriano et al., 2012). Importantly, genetic ablation of FAM83B in breast and colon cancer cells significantly suppressed tumor cell growth and in vivo tumorigenicity (R. Cipriano et al., 2012). Growth suppression upon FAM83B ablation was coupled with decreased CRAF, PI3K, and AKT membrane localization, and subsequent suppression of activating phosphorylations of both ERK1/2 and AKT (R. Cipriano et al., 2012). In parallel to our discovery of FAM83B, the Bissell laboratory identified FAM83A using a retroviral cDNA library screen for genes that confer resistance to an EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) in tumorigenic mammary epithelial cells. Together, subsequent studies determined that the N-terminal DUF1669 domain of FAM83A and FAM83B, which is conserved amongst the 8 FAM83 proteins, is responsible for inducing cellular transformation (R. Cipriano et al., 2014). All five FAM83 members tested to date (FAM83A-E), which lack any significant homology beyond the DUF1669 and vary greatly in size ranging from 434–1179 amino acids, are capable of inducing transformation. Finally, expression studies revealed that the FAM83 members are not only elevated in a wide variety of cancers, but in many instances, multiple FAM83 paralogs show increased expression (Bartel, Parameswaran, Cipriano, & Jackson, 2016). We envision that future studies will involve identifying the unique function of each FAM83 protein, and the development of new strategies to therapeutically target both the conserved and unique oncogenic properties of FAM83 proteins.

Understanding how cells escape from metastatic dormancy

In some cases, the VBIM integration may simply disrupt gene expression rather than produce a dominant VBIM-driven product, as was the case recently reported by Robinson and colleagues, who used VBIM to identify drivers of advanced metastatic disease in breast cancer (Robinson et al., 2020). They used a metastatic murine cell line (D2.OR) that can intravasate from the mammary gland and spread to the lungs. However, D2.OR cells become dormant once they reach the lungs (Robinson et al., 2020). Using VBIM, we sought to determine which mechanisms could drive exit from dormancy and promote macro-metastasis. The original selection was performed using 3-dimensional (3D) cultures, since D2.OR cells do not grow in 3D cultures unless they escape from dormancy. Those cells that grew in 3D culture were then validated in vivo. An antisense VBIM insertion was identified in the gene encoding SLX4-interacting protein (SLX4IP). In this case, the VBIM insertion into one allele was sufficient to reduce the expression of SLX4IP by ~50% and allow cells to escape dormancy. In naïve cells, shRNA-mediated reduction of SLX4IP increased the expression of the telomerase reverse transcriptase subunit (TERT) and the formation of the core telomerase holoenzyme. In contrast, elevated SLX4IP expression promoted the alternative lengthening of telomeres (ALT). Thus, this discovery led to a new understanding of how SLX4IP regulates telomere maintenance mechanisms and how those mechanisms contribute to metastatic dormancy.

Additional VBIM discoveries

In addition to our own discoveries, other laboratories have used VBIM to identify genes involved in driving diverse phenotypes. These include (i) elevated expression of MITF (Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor) from a screen of melanoma cells treated with the ERK inhibitor SCH772984 (Muller et al., 2014); (ii) a C-terminal truncated variant of SREBP-2 and an N-terminal truncated catalytic domain of HMG-CoA reductase from a screen for genes involved in cholesterol biosynthesis (Jiang et al., 2014); and an insertion in the antisense orientation that repressed expression of nuclear pore component NUP214, identifying its role in enterovirus infection (B. Wang, Zhang, & Zhao, 2013). In these studies, VBIM lentiviruses have been used to identify both previously uncharacterized genes/proteins, as well as new functions for known genes/proteins. As outlined in Figure 2, diverse VBIM-induced mutations, including the expression of full-length, truncated, and antisense RNAs as drivers have sparked these impactful discoveries.

LIMITATIONS OF THE VBIM STRATEGY

The discoveries discussed above highlight the immense value of the VBIM strategy. While using the VBIM strategy in numerous screens, however, we have identified some relatively minor challenges. First, while we generally consider insertional mutagenesis by retroviruses to be random, studies of integration preferences have identified that most viruses integrate more frequently within actively transcribed regions, probably due to the relaxed or condensed structures of chromatin in active versus inactive genes (G. P. Wang et al., 2007). This finding suggests that silent genes will be less susceptible to viral integration and, therefore, under-represented in a screen, while active genes will be over-represented. In part, this is why we recommend that a screen involve ~50X genome coverage, as even untranscribed genes would be targeted to some degree by a saturating number of VBIM integrations.

A second limitation stems from challenges in our ability to predict how VBIM mutations result in a mutant phenotype in some cases. For example, when a VBIM insertion creates a truncated protein, it can be difficult to predict whether this variant protein has wild-type or dominant-negative function, or whether the insertion simply disrupts protein expression from the allele. In some cases, existing literature can guide prediction, but in others, one would need to test (i) the VBIM-driven cDNA (cloned from the original mutant), (ii) the full-length cDNA, (iii) and an shRNA or CRISPR knock-out, all in parallel. In this example, the impact of the VBIM mutation can be solved by testing each possibility; it is just that more effort will be needed to confirm the hit. In other cases, for example, when the VBIM insertion occurs in an intergenic region, we have yet to find a satisfying resolution. In part, this reflects our limited understanding of the genome beyond the 2% that codes for proteins, which is also reflected in the databases used to identify VBIM insertion sites. In cases where the gene of interest cannot be clearly identified, we often remove those insertions from our candidate lists, despite the possibility that the VBIM insertion may be regulating an unknown genetic element to cause the mutant phenotype. In this way, libraries of cDNAs, shRNAs, CRISPR-guides, and GSEs can have an advantage, as identifying what was delivered to the mutant cells pinpoints the causative genetic event.

Finally, each screen performed using the VBIM strategy is on a genome-wide scale. In contrast, libraries of cDNAs, shRNAs, CRISPR-guides, and GSEs can be sub-divided into discrete categories (kinome, epigeneome, cell cycle regulators, etc.), allowing more focused hypotheses to be tested with relative ease. Depending on the question one is trying to address, such approaches may have greater merit than a whole genome screen. Thus, depending on the research question, one needs to evaluate the available methodologies and decide on the technique that best aligns with the desired outcome. For our goals, the VBIM strategy has been invaluable, as we have made an important discovery in every screen we have performed to date, as noted above.

CONSIDERATIONS FOR MOVING VBIM INTO ANIMAL MODELS

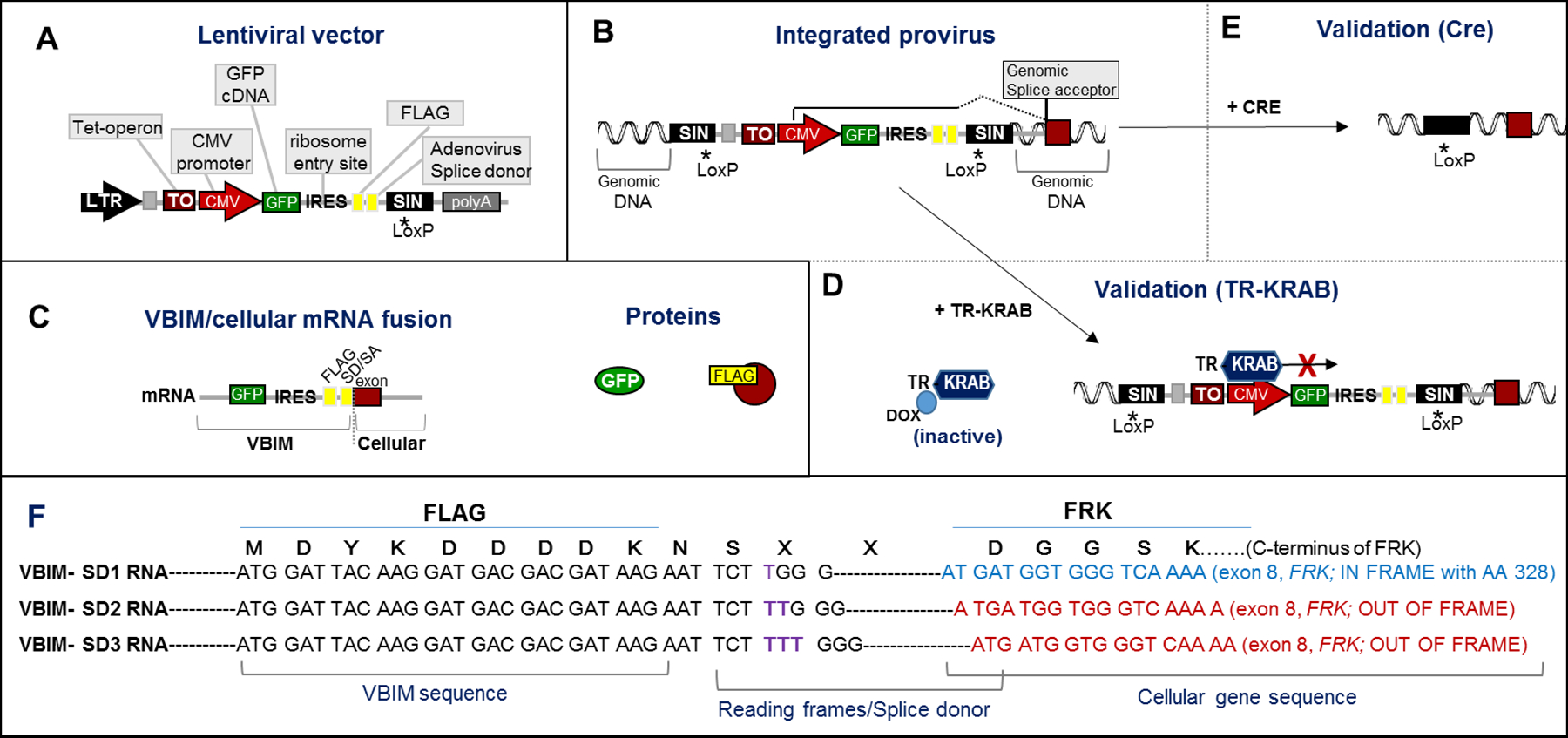

Most of the discoveries made using VBIM have focused on cancer biology and cancer therapeutics using cultured cells. As we contemplated how VBIM screens could be improved, we sought to perform screens in vivo using animal models. For some biological phenomenon, using animal models rather than isolated cell systems would be highly beneficial, if not required. For example, screening for resistance to immune-activating therapies that require the complex interplay of various immune cells and cancer cells would need to be performed in vivo. While many modes of immunotherapy have been described, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) that target inhibitory receptor-ligand interactions between immune cells and tumor cells (anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1), or immune cells and antigen-presenting cells (anti-CTLA4), are now known to have an impressive clinical impact in some cancers (reviewed in (Sharma, Hu-Lieskovan, Wargo, & Ribas, 2017)). These receptor-ligand interactions that normally restrain our immune system from damaging our tissues (i.e. checkpoints) are ultimately hijacked by cancer cells to help them avoid anti-tumor immune responses. To illustrate the value forward genetics screens can have in this field, recent in vivo CRISPR screens have identified a number of factors altering the sensitivity to immunotherapy (Interferon signaling: Stat1, Jak1, Ifngr2, Ifngr1, Jak2, Ptpn2, ASF1A) and T-cell-mediated killing (Dhx37, Lyn, and Odc1) (Dong et al., 2019; Li et al., 2020; Manguso et al., 2017). We posited that the VBIM strategy would provide a complementary avenue for screening in vivo, especially with the success of using RNA-seq to identify VBIM insertion sites, which alleviates previous requirements of cloning individual resistant cells Figure 4 (and referenced by (De et al., 2021)). Here, we discuss a number of important considerations that we encountered as we prepared and completed an in vivo VBIM screen (unpublished).

Figure 4. Schematic of in vivo VBIM selection.

Following the generation of VBIM libraries, cells injected into mice can be selected. In the case of selection for resistance to standard-of-care or experimental therapeutics, the experimental considerations (drug dosage and timing, cell number, VBIM integration numbers, etc.) need to create substantial differences in tumor growth kinetics when comparing sensitive and resistant cells/tumors. Pilot experiments examining controls that consist of cells expressing a known resistance gene or a mixture of resistant cells with sensitive cells at known frequencies should provide convincing tumor growth differences. During the screen, control cells infected with a non-mutagenic lentivirus should be included to assess therapeutic efficiency; tumors in VBIM-infected tumors should be consistently larger than control tumors. Following selection, RNA-seq for VBIM-tagged RNAs will identify genes that have been targeted within the resistant populations, with relative RNA expression correlating with relative enrichment (i.e. genes that are most frequently represented within the RNA-seq data are stronger candidates to induce resistance than genes with fewer reads).

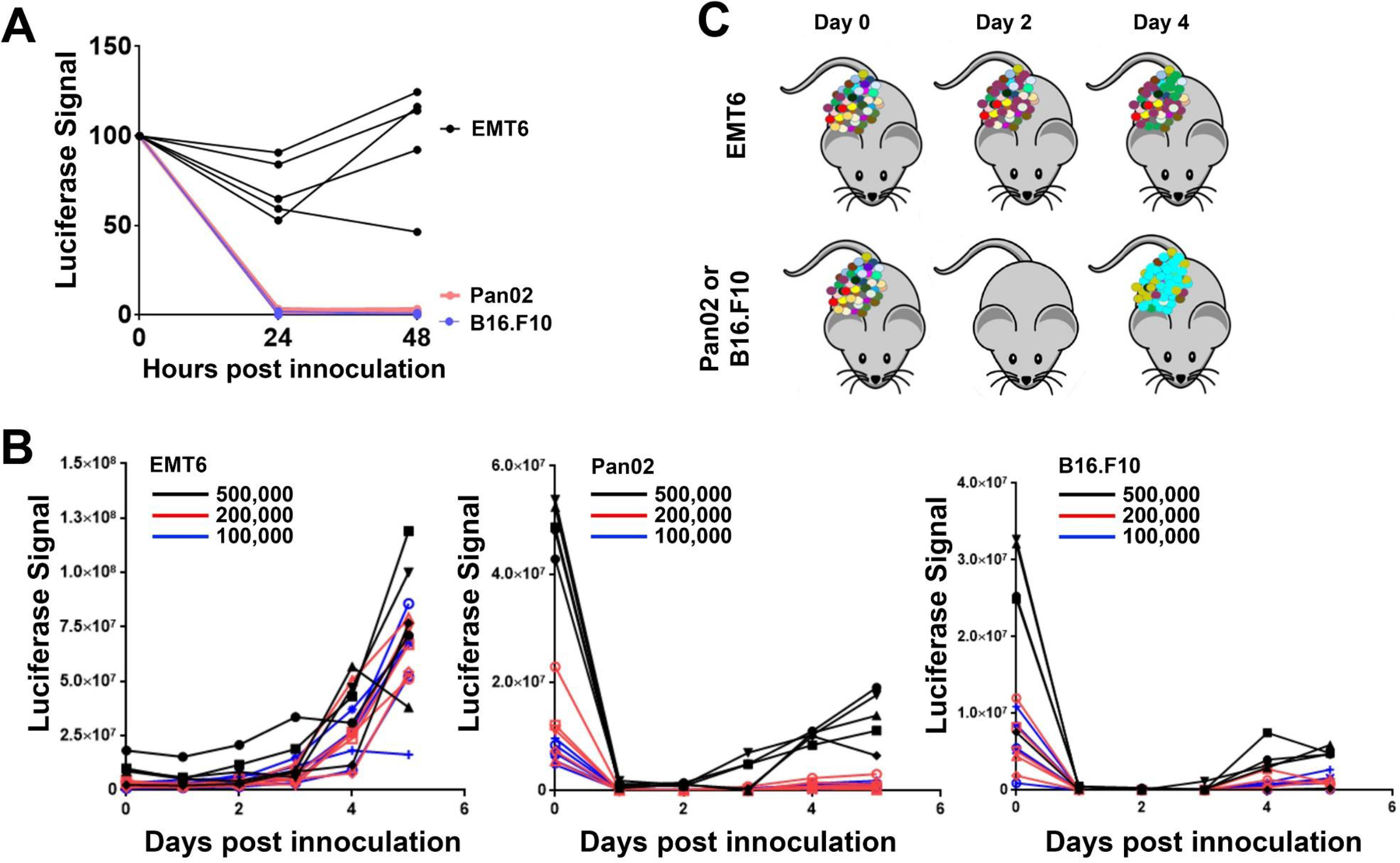

Choosing a model for an in vivo screen

As we began developing protocols to search for VBIM-induced genetic changes that promote resistance to ICIs, we selected three potential cell lines with reported ICI sensitivities (Pan02 pancreatic cancer cells, B16.F10 melanoma cells, and EMT6 breast cancer cells). As with all forward genetics screens, the model and phenotype chosen for study need to be carefully chosen and the parameters of the screen, carefully defined. We soon recognized that an important consideration that can be prohibitive for in vivo screens is the potential “drop-out” rate of the cell model when cells are injected in vivo. As an example, we labeled each cell line with luciferase. When injected into syngeneic mice, the luciferase signal generated from Pan02 and B16.F10 cells was abolished 24 hours after injection, despite eventual outgrowth of the tumor (Figure 5). In contrast, the loss of luciferase signal following injection of EMT6 cells was as little as 5% (and at most 50%). These findings suggested that EMT6 cells would retain a greater level of VBIM-library diversity following transplantation in vivo, when compared to Pan02 and B16.F10 cells. Knowing the degree of cell drop out after introduction to the in vivo environment is a critical factor for full-genome screening. If 90% or more of the library diversity is lost after injecting the cells but before adding the therapy of choice, the degree of genome coverage (i.e. the number of VBIM integrations that will be screened) will be severely diminished, resulting in an incomplete screen. Similarly, in some models, increasing the number of inoculated cells does not increase tumor development (size or timing) in a linear way (Nguyen et al., 2014), suggesting that injecting more cells may also negatively impact the diversity of the VBIM libraries. Undoubtedly, a balance must be struck between the number of VBIM-infected cells injected (and by extension, the number of VBIM integrations) and the loss of potential diversity due to stochastic drop out.

Figure 5. Assessing tumor cell loss in vivo.

Murine triple negative breast cancer (EMT6), pancreatic cancer (Pan02), and melanoma (B16.F10) cell lines were used to assess the potential loss of diversity (i.e. drop-out) of each line following inoculation in vivo. Infections of 100,000, 200,000, or 500,000 cells into either Balb/c (EMT6) or C57bl/6 mice (Pan02 and B16.F10) are shown; 5 tumors were assessed for each cell line and each cell number, with each injection represented as an individual growth curve. In vivo tumor growth was monitored 1–6 days after inoculation using bioluminescence (luciferase signal for each tumor is plotted). (A) The luminescence signal from 500,000 cells/injection at time 0 (immediately after injection) and after 24 or 48 hours indicates that the number of luciferase-positive Pan02 and B16.F10 cells is drastically reduced at these times; EMT6 populations remain more stable after inoculation. (B) The luminescence signal for all 3 cell numbers/injections are plotted. (C) Extrapolation of the data from the luminescence to illustrate library complexity in a VBIM screen indicates that the initial diversity of the VBIM libraries would be better maintained in the EMT6 models. The Pan02 and B16.F10 models show a dramatic, stochastic reduction of cell number following injection, suggesting that a dramatic loss of VBIM diversity would occur. Such a large loss of library complexity would make a suitable genetic screen in these cells challenging.

Choosing the right selection parameters

Selection conditions should be clearly identified and tested empirically prior to beginning an in vivo experiment in an animal model. Variables that may influence any in vivo selection include drug dosage, and frequency and duration of therapy. Optimal treatment protocols can generally be found in the literature for each model, but should be confirmed in each laboratory by using mixtures of sensitive and resistant cells. For example, in preparation for our ICI screen, we initially assessed our mutant detection limit by mixing ICI resistant cells within ICI sensitive cells at fixed ratios (1:100, 1:500, 1:1,000, 1:5,000 and 1:500,000) and assessing whether resistant tumors developed following treatment. We determined that a dilution of resistant to sensitive cells at a mixture of 1:5,000 was sufficient to produce a resistant tumor following ICI therapy. This information is important, as it relates to the number of VBIM integrations that can be represented in a pool of cells initially injected to create the tumors for treatment/selection. Ideally, a developing tumor should show steady growth from the time of injection until the time of treatment.

The size and number of libraries to be screened also need careful consideration. As mentioned above, we recommend using a larger number of independent VBIM libraries with fewer cells, rather than fewer libraries with more cells. Our current in vivo ICI screen is unpublished as we prepare this review, but RNA-seq data from the resistant tumors we have collected thus far is confirming the potential value of identifying VBIM insertions based on RNA-seq reads (Figure 3). For example, examining 109 insertion sites from 18 tumors, we identified that 75% of the insertions were within a gene (62% in a coding gene and 13% in a lncRNA). Seventy-five percent of the gene integrations were in the sense orientation, while 25% were in the anti-sense orientation. Moreover, insertions were spread out across the gene bodies, as predicted based on studies of lentiviral integrations (G. P. Wang et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2003). Twenty-two percent of all integrations were in intergenic regions. These data suggest that RNA-seq can identify VBIM insertions that are antisense or in non-coding regions that should not, presumably, create a polyadenylated mRNA. We are cautious in this interpretation, because we have not confirmed that the intergenic VBIM/cellular fusion RNAs identified represent the actual insertion site rather than splicing into a cryptic splice acceptor sequence elsewhere in the genome. We are currently validating and assessing the VBIM-targeted genes identified in our ICI resistance screen, and look forward to identifying, in the near future, the genes involved in regulating ICI response.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Forward genetic screens have taken many forms, and been performed in many models. The numerous examples listed above provide evidence that the VBIM method has become an important tool for identifying novel proteins involved in the biology of cancer cells and their responses to therapeutic agents. This review discusses the many advantages of the VBIM strategy with the hope that other researchers will find the approach applicable to their phenotypes of interest. As we look toward future uses of the VBIM strategy, we are focusing on merging the VBIM method with high-throughput RNA sequencing and informatics to allow more complex screens to be performed in increasingly relevant, in vivo models. In our opinion, additional in vivo screens of high value will include those searching for additional mechanisms of resistance to therapy, even repeating screens that have already been performed in cultured cells previously, as distinct context-dependent interactions in the tumor microenvironment are likely to be important factors not yet sufficiently interrogated (Qu et al., 2019). Identifying novel therapeutic targets that can induce resistance to current standard-of-care therapies will undoubtedly remain an unmet clinical need (DeMichele et al., 2017). We propose that the use of VBIM in vivo is a valuable way to identify the next generation of targets for therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant P01CA062220 to G.R. Stark and by Department of Defense grant W81XWH-18-1-0552 and National Institutes of Health grant R01CA252224 to M.W. Jackson.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT:

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

LITERATURE CITED

- Bartel CA, Parameswaran N, Cipriano R, & Jackson MW (2016). FAM83 proteins: Fostering new interactions to drive oncogenic signaling and therapeutic resistance. Oncotarget, 7(32), 52597–52612. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose R, & Ma CX (2021). Breast Cancer, HER2 Mutations, and Overcoming Drug Resistance. N Engl J Med, 385(13), 1241–1243. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr2110552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipriano R, Graham J, Miskimen KL, Bryson BL, Bruntz RC, Scott SA, . . . Jackson MW (2012). FAM83B mediates EGFR- and RAS-driven oncogenic transformation. J Clin Invest, 122(9), 3197–3210. doi: 10.1172/JCI60517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipriano R, Miskimen KL, Bryson BL, Foy CR, Bartel CA, & Jackson MW (2014). Conserved oncogenic behavior of the FAM83 family regulates MAPK signaling in human cancer. Mol Cancer Res, 12(8), 1156–1165. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-13-0289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipriano R, Miskimen KLS, Bryson BL, Foy CR, Bartel CA, & Jackson MW (2013). FAM83B-mediated activation of PI3K/AKT and MAPK signaling cooperates to promote epithelial cell transformation and resistance to targeted therapies. Oncotarget, 4(5), 729–738. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3742833/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Laurentiis M, Cancello G, D’Agostino D, Giuliano M, Giordano A, Montagna E, . . . De Placido S (2008). Taxane-based combinations as adjuvant chemotherapy of early breast cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Clin Oncol, 26(1), 44–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.3787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De S, Cipriano R, Jackson MW, & Stark GR (2009). Overexpression of kinesins mediates docetaxel resistance in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res, 69(20), 8035–8042. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De S, Dermawan JK, & Stark GR (2014). EGF receptor uses SOS1 to drive constitutive activation of NFkappaB in cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 111(32), 11721–11726. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1412390111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De S, Holvey-Bates EG, Mahen K, Willard B, & Stark GR (2021). The ubiquitin E3 ligase FBXO22 degrades PD-L1 and sensitizes cancer cells to DNA damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 118(47). doi: 10.1073/pnas.2112674118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMichele A, Yee D, & Esserman L (2017). Mechanisms of Resistance to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med, 377(23), 2287–2289. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr1711545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong MB, Wang G, Chow RD, Ye L, Zhu L, Dai X, . . . Chen S (2019). Systematic Immunotherapy Target Discovery Using Genome-Scale In Vivo CRISPR Screens in CD8 T Cells. Cell, 178(5), 1189–1204 e1123. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.07.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo C, & Stark GR (2011). FER tyrosine kinase (FER) overexpression mediates resistance to quinacrine through EGF-dependent activation of NF-kappaB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 108(19), 7968–7973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105369108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirokawa N, Noda Y, Tanaka Y, & Niwa S (2009). Kinesin superfamily motor proteins and intracellular transport. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 10(10), 682–696. doi: 10.1038/nrm2774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer MK, Niknafs YS, Malik R, Singhal U, Sahu A, Hosono Y, . . . Chinnaiyan AM (2015). The landscape of long noncoding RNAs in the human transcriptome. Nat Genet, 47(3), 199–208. doi: 10.1038/ng.3192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W, Tang JJ, Miao HH, Qu YX, Qin J, Xu J, . . . Song BL (2014). Forward genetic screening for regulators involved in cholesterol synthesis using validation-based insertional mutagenesis. PLoS One, 9(11), e112632. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Huang Q, Luster TA, Hu H, Zhang H, Ng WL, . . . Wong KK (2020). In Vivo Epigenetic CRISPR Screen Identifies Asf1a as an Immunotherapeutic Target in Kras-Mutant Lung Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Discov, 10(2), 270–287. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-0780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T, Jackson MW, Singhi AD, Kandel ES, Yang M, Zhang Y, . . . Stark GR (2009). Validation-based insertional mutagenesis identifies lysine demethylase FBXL11 as a negative regulator of NFkappaB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 106(38), 16339–16344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908560106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T, Jackson MW, Wang B, Yang M, Chance MR, Miyagi M, . . . Stark GR (2010). Regulation of NF-kappaB by NSD1/FBXL11-dependent reversible lysine methylation of p65. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 107(1), 46–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912493107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manguso RT, Pope HW, Zimmer MD, Brown FD, Yates KB, Miller BC, . . . Haining WN (2017). In vivo CRISPR screening identifies Ptpn2 as a cancer immunotherapy target. Nature, 547(7664), 413–418. doi: 10.1038/nature23270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui A, Ihara T, Suda H, Mikami H, & Semba K (2013). Gene amplification: mechanisms and involvement in cancer. Biomol Concepts, 4(6), 567–582. doi: 10.1515/bmc-2013-0026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller J, Krijgsman O, Tsoi J, Robert L, Hugo W, Song C, . . . Peeper DS (2014). Low MITF/AXL ratio predicts early resistance to multiple targeted drugs in melanoma. Nat Commun, 5, 5712. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen LV, Cox CL, Eirew P, Knapp DJ, Pellacani D, Kannan N, . . . Eaves CJ (2014). DNA barcoding reveals diverse growth kinetics of human breast tumour subclones in serially passaged xenografts. Nat Commun, 5, 5871. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohshima K, Hatakeyama K, Nagashima T, Watanabe Y, Kanto K, Doi Y, . . . Yamaguchi K (2017). Integrated analysis of gene expression and copy number identified potential cancer driver genes with amplification-dependent overexpression in 1,454 solid tumors. Sci Rep, 7(1), 641. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00219-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Y, Dou B, Tan H, Feng Y, Wang N, & Wang D (2019). Tumor microenvironment-driven non-cell-autonomous resistance to antineoplastic treatment. Mol Cancer, 18(1), 69. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-0992-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson NJ, Morrison-Smith CD, Gooding AJ, Schiemann BJ, Jackson MW, Taylor DJ, & Schiemann WP (2020). SLX4IP and telomere dynamics dictate breast cancer metastasis and therapeutic responsiveness. Life Sci Alliance, 3(4). doi: 10.26508/lsa.201900427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma P, Hu-Lieskovan S, Wargo JA, & Ribas A (2017). Primary, Adaptive, and Acquired Resistance to Cancer Immunotherapy. Cell, 168(4), 707–723. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.01.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabruyn SP, & Griffioen AW (2008). NF-kappa B: a new player in angiostatic therapy. Angiogenesis, 11(1), 101–106. doi: 10.1007/s10456-008-9094-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan MH, De S, Bebek G, Orloff MS, Wesolowski R, Downs-Kelly E, . . . Eng C (2012). Specific kinesin expression profiles associated with taxane resistance in basal-like breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 131(3), 849–858. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1500-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Zhang X, & Zhao Z (2013). Validation-based insertional mutagenesis for identification of Nup214 as a host factor for EV71 replication in RD cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 437(3), 452–456. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.06.101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GP, Ciuffi A, Leipzig J, Berry CC, & Bushman FD (2007). HIV integration site selection: analysis by massively parallel pyrosequencing reveals association with epigenetic modifications. Genome Res, 17(8), 1186–1194. doi: 10.1101/gr.6286907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Nag SA, & Zhang R (2015). Targeting the NFkappaB signaling pathways for breast cancer prevention and therapy. Curr Med Chem, 22(2), 264–289. doi: 10.2174/0929867321666141106124315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Li Y, Crise B, & Burgess SM (2003). Transcription start regions in the human genome are favored targets for MLV integration. Science, 300(5626), 1749–1751. doi: 10.1126/science.1083413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerp SF, Vens C, Floot B, Verheij M, & van Triest B (2014). NAD(+) depletion by APO866 in combination with radiation in a prostate cancer model, results from an in vitro and in vivo study. Radiother Oncol, 110(2), 348–354. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.10.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu N, Zhang J, Du Y, Qin X, Miao R, Nan J, . . . Yang J (2020). Loss of ZIP facilitates JAK2-STAT3 activation in tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 117(26), 15047–15054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1910278117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.