Abstract

The planar cell polarity (PCP) signaling pathway is a potent developmental regulator of directional cell behaviors such as migration, asymmetric division and morphological polarization that are critical for shaping the body axis and the complex three-dimensional architecture of tissues and organs. PCP is considered a noncanonical Wnt pathway due to the involvement of Wnt ligands and Frizzled family receptors in the absence of the beta-catenin driven gene expression observed in the canonical Wnt cascade. At the heart of the PCP mechanism are protein complexes capable of generating molecular asymmetries within cells along a tissue-wide axis that are translated into polarized actin and microtubule cytoskeletal dynamics. PCP has emerged as an important regulator of developmental, homeostatic and disease processes in the respiratory system. It acts along other signaling pathways to create the elaborately branched structure of the lung by controlling the directional protrusive movements of cells during branching morphogenesis. PCP operates in the airway epithelium to establish and maintain the orientation of respiratory cilia along the airway axis for anatomically directed mucociliary clearance. It also regulates the establishment of the pulmonary vasculature. In adult tissues, PCP dysfunction has been linked to a variety of chronic lung diseases such as cystic fibrosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension, stemming chiefly from the breakdown of proper tissue structure and function and aberrant cell migration during regenerative wound healing. A better understanding of these (impaired) PCP mechanisms is needed to fully harness the therapeutic opportunities of targeting PCP in chronic lung diseases.

Introduction

The planar cell polarity (PCP) signaling pathway is part of the larger Wnt pathway family. Wnt pathways comprise a group of critical, highly conserved signal transduction pathways that are fundamental to development, homeostasis and disease in all tissues, including the lung [1,2]. Three main pathways are recognized: 1. the canonical or beta-catenin-dependent pathway (Wnt/β-cat), 2. the noncanonical Wnt/calcium pathway, and 3. the noncanonical Wnt/PCP pathway [3], the latter being the focus of this review. Wnt cascades are usually initiated by the binding of a secreted Wnt ligand to a Frizzled (Fzd) family receptor, which leads to the activation of its intracellular binding partner Dishevelled (Dvl, Figure 1A). In the canonical Wnt/β-cat program, Wnt binding leads to the cytoplasmic stabilization and nuclear entry of the β-cat effector to turn on target gene expression. Noncanonical pathways do not involve a β-cat dependent transcriptional output [4]. The Wnt/calcium pathway controls intracellular calcium levels via calcium release from the endoplasmic reticulum [5]. PCP signaling regulates directional cell behaviors such as migration, division and morphological polarization via the cytoskeleton [6]. The presence of 19 WNTs and 10 FZDs in humans and mice highlights the complexity of potential signal cascades and outcomes [3]. While canonical and noncanonical pathways were once thought to be strictly separated with dedicated ligands and receptors [3], it now appears that cells can switch between modes in a context-dependent manner [7,8].

Figure 1. Canonical Wnt vs. PCP signaling pathways and the airway epithelial PCP mechanism.

(A) Schematic outline of the canonical Wnt/β-catenin and the noncanonical PCP pathways, highlighting shared and unique components and signaling outcomes. The noncanonical Wnt/PCP schematic illustrates the asymmetric localization and interaction of core PCP complexes at the apical junctions between neighboring cells. (B) A conserved PCP signaling imparts morphological polarity to Drosophila wing epithelial cells (top) and human airway epithelial cells (bottom) along the proximal-distal tissue axis through the asymmetric localization and function of the core PCP proteins, which is directly responsible for the lateral placement of wing hairs in the fly and the directional movement of cilia in the airways, respectively. (C) In individual multiciliated cells, the proximal orientation of cilia is achieved by linking the ciliary layer to the proximal side cell cortex occupied by the Fzd and Dvl core PCP proteins via PCP-regulated microtubules. In Vangl1 mutant cells the asymmetric Fzd domain fails to form and cilia do not planar polarize. Schematics of mammalian airway epithelial cells in B and C summarize findings from Vladar et al. [60].

PCP is best known as a developmental regulator of polarized tissue morphogenesis involved in the hair follicle and cochlear hair cell orientation and convergent extension during neural tube closure [9-11]. However, it also carries out homeostatic roles in adult organs, including the lung [12,13] and is accordingly involved in diseases affecting these tissues [14]. The most completely elucidated PCP signaling mechanism is for its namesake process — the polarization of cells along the proximal-distal plane of an epithelial sheet, orthogonal to their apical-basal axis (Figure 1B). It remains best understood in Drosophila, where it controls the uniform orientation of cuticular hairs and bristles along epithelial surfaces [14] (Figure 1B). These planar polarized structures emerge following the establishment of molecular asymmetries at the apical cell cortex along the proximal-distal tissue axis within cells by the so called ‘core’ PCP proteins. This core cassette consists of the Frizzled receptor and its cytoplasmic binding partners Dishevelled and Diego, the transmembrane protein Van Gogh and its binding partner Prickle, and the Flamingo protocadherin. Molecular asymmetry is imparted by the segregation of the core PCP proteins into two complexes (Frizzled, Dishevelled, Diego and Flamingo vs. Van Gogh, Prickle and Flamingo) that occupy opposing membrane domains at the proximal and distal side adherens junctions of the cell (Figure 1A,B). The asymmetric membrane domains are established and maintained by heterotypic interaction between the two complexes across adjacent cell membranes, which propagates asymmetry from cell to cell, coordinating the polarity of neighbors (Figure 1A,B). Downstream of the core cassette, the planar polarization of cellular structures is carried out by effector proteins acting on the actin and microtubule cytoskeletons. Core PCP localization and activity in epithelial cells depends on robust apical-basal polarity, thus the loss of regulators such as the Van Gogh binding partner and core PCP effector Scribble (SCRIB in humans) also leads to PCP phenotypes [15-17]. See Table 1 for a list of Drosophila epithelial PCP factors and their known or putative mammalian counterparts.

Table 1.

PCP proteins in Drosophila and mammals

|

Drosophila name |

Mammalian name (human/mouse symbol) | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core PCP proteins | Van Gogh | VANGL Planar Cell Polarity Protein 2 (VANGL2/Vangl2) VANGL Planar Cell Polarity Protein 1 (VANGL1/Vangl1) |

four-pass transmembrane protein |

| Prickle | Prickle Planar Cell Polarity Protein 1 (PRICKLE1/Prickle1) Prickle Planar Cell Polarity Protein 2 (PRICKLE2/Prickle2) Prickle Planar Cell Polarity Protein 3 (PRICKLE3/Prickle3) Prickle Planar Cell Polarity Protein 4 (PRICKLE4/Prickle4) |

membrane associated protein; Van Gogh binding partner | |

| Frizzled | Frizzled Class Receptor 3 (FZD3/Fzd3) Frizzled Class Receptor 6 (FZD6/Fzd6) |

four-pass transmembrane protein; Wnt family receptor | |

| Dishevelled | Dishevelled Segment Polarity Protein 1 (DVL1/Dvl1) Dishevelled Segment Polarity Protein 2 (DVL2/Dvl2) Dishevelled Segment Polarity Protein 3 (DVL3/Dvl3) |

membrane associated protein; Frizzled binding partner | |

| Diego | Ankyrin Repeat Domain 6 (ANKRD6/Ankrd6) Inversin (INVS/Invs) |

membrane associated protein; Frizzled binding partner | |

| Flamingo | Cadherin EGF LAG Seven-Pass G-Type Receptor 1 (CELSR1/Celsr1) Cadherin EGF LAG Seven-Pass G-Type Receptor 2 (CELSR2/Celsr2) Cadherin EGF LAG Seven-Pass G-Type Receptor 3 (CELSR3/Celsr3) |

nonclassical cadherin; Frizzled and Van Gogh binding partner | |

| Upstream proteins & Wnt ligands | Fat | FAT Atypical Cadherin 1 (FAT1/Fat1) FAT Atypical Cadherin 2 (FAT2/Fat2) FAT Atypical Cadherin 3 (FAT3/Fat3) FAT Atypical Cadherin 4 (FAT4/Fat4) |

atypical cadherin protein; Dachsous binding partner; Four-jointed substrate |

| Dachsous | Dachsous Cadherin-Related 1 (DCHS1/Dcsh1) Dachsous Cadherin-Related 2 (DCHS2/Dcsh2) |

cadherin-related protein | |

| Four-jointed | Four-Jointed Box Kinase 1 (FJX1/Fjx1) | Golgi resident kinase | |

| Wingless | Wnt Family Member 1 (WNT1/Wnt1) | Wnt family secreted ligand; not known to regulate vertebrate PCP | |

| Wnt4 | Wnt Family Member 9A/B (WNT9A/B / Wnt9a/b) | Wnt family secreted ligand; known to regulate vertebrate PCP | |

| Wnt5 | Wnt Family Member 5A/B (WNT5A/B / Wnt5a/b) | Wnt family secreted ligand; known to regulate vertebrate PCP | |

| no ortholog | Wnt Family Member 4 (WNT4/Wnt4) | Wnt family secreted ligand; proposed to regulate vertebrate PCP | |

| Downstream effector proteins | Inturned | Inturned Planar Cell Polarity Protein (INTU/Intu) | guanine nucleotide exchange factor; ciliogenesis |

| Fuzzy | Fuzzy Planar Cell Polarity Protein (FUZ/Fuz) | regulator | |

| Fritz | WD Repeat Containing Planar Cell Polarity Effector (WDPCP/Wdpcp) | cytoplasmic WD40 repeat protein; ciliogenesis regulator | |

| no ortholog | Cilia And Flagella Associated Protein 126 (CFAP126/Cfap126) | ciliogenesis regulator; also known as Flattop | |

| Scribble | Scribble Planar Cell Polarity Protein (Scrib/SCRIB) | scaffolding protein; apical-basal polarity regulator; Vangl binding partner |

Vertebrates express multiple isoforms of core PCP protein homologs, which have tissue-specific regulation with both distinct and overlapping functions [6]. Mechanistic conservation with flies is supported by asymmetric core PCP protein localization in multiple tissues including the cochlear, nodal, kidney tubule and airway epithelium [6] (Figure 1B). Vertebrate PCP is also active in nonepithelial cells, for example in migrating neurons or mesenchymal cells [6]. Due to their wide-spread developmental expression, mutations in Vangl1 or Vangl2 (Van Gogh homologs) produce laterality [18], neural tube closure [19], neuronal [20], renal [21], cardiac [22] and auditory [23] defects in mice. VANGL1 and VANGL2 mutations in humans are associated with spina bifida [24,25], while PRICKLE1 and PRICKLE2 mutations are associated with epilepsy [20].

Upstream cues that impart directionality to the core PCP mechanism, in particular potential Wnt ligand(s) involved in PCP, remain a topic of intense investigation. In the Drosophila wing epithelium, both the canonical Wnt ligand Wingless (human homolog, WNT1) and Wnt4 (human homolog, WNT9A/B) are required for PCP [26]. Several Wnts, notably Wnt5a, have been proposed to regulate the pathway in the cochlear epithelium and in the embryonic node based on knockout mouse studies [27-29]. While Wnt gradients have been observed in these tissues [27], it has yet to be firmly established that Wnts provide an instructive as opposed to a permissive signal for PCP. Direct binding between a Wnt ligand and the asymmetrically localized Fzd receptor has also not been shown. Additionally, in flies, another set of PCP proteins comprised of the protocadherins Fat and Dachsous and the Four-jointed kinase are thought to act upstream of and provide global directional input to the core cassette [30]. Multiple mammalian homologs of these proteins exist [31] and Dachsous1 and Fat4 have been implicated in PCP in the kidney epithelium [32,33], but mechanistic studies are lagging.

This review focuses exclusively on the role of PCP signaling events in the developmental, homeostatic and disease processes of the lung. It is important to note that PCP signaling has been used somewhat inconsistently in the vertebrate literature to describe a variety of mechanisms involving cytoskeletal or transcriptional regulation downstream of a purported noncanonical Wnt cascade. We define PCP as mechanisms that involve the core PCP proteins [6] as this highly conserved cassette is directly responsible for creating the cellular asymmetries that drive polarized behaviors. Processes where the involvement of the core PCP proteins is suspected, but not demonstrated are included as unspecified noncanonical mechanisms.

Developmental branching morphogenesis depends on PCP and other noncanonical pathways

The highly polarized and elaborately branched architecture of the respiratory system is critical for the gas exchange and airway clearance functions of the lung. This architecture is achieved by iterative distal branching and outgrowth of the bronchial tree [34]. The branching pattern is stereotyped and emerges in response to a complex developmental program that integrates epithelial and mesenchymal signals from multiple pathways. Growth and branching depend on the precise coordination of proliferation and polarized cell behaviors such as migration, oriented division and cell shape changes [34]. Canonical Wnt signaling is a critical regulator of the proliferative expansion of cells during branching [35]. The requirement for PCP in branching morphogenesis is based on the presence of hypoplastic distal lungs with fewer and less elaborately branched airways in mice mutant for the Vangl2 (Van Gogh homolog) and Celsr1 (Flamingo homolog) core PCP proteins [36]. See Table 2 for a list of mouse mutants and lung phenotypes. Celsr1 and Vangl2 are localized to epithelial cell membranes in the bronchial tree and are strongly enriched at branch points. The actin cytoskeleton fails to polarize at the apical surface in epithelial cells and at the cell cortex in mesenchymal cells in Celsr1 and Vangl2 mutant lungs during branching, consistent with PCP modulating the cytoskeleton (Figure 2). Branching defects also exist following the inhibition of Rho kinase [36], an important downstream PCP effector that modulates actin dynamics. The actin motor Non-muscle myosin IIA, a target of Rho kinase activity localizes to budding airway tips and stalks and its pharmacological inhibition blocked branching [37]. Non-muscle myosin IIA has both actin cross-linking and contractile properties to control cell shape and motility [38], and may be a critical target of PCP in the branching program. Ptk7, an inactive tyrosine kinase that is thought to act as noncanonical Wnt co-receptor has similar distal lung phenotypes and shows genetic interaction with core PCP mutants in lung development [39,40], but its precise role in the lung is untested.

Table 2.

PCP mouse mutants and phenotypes

| Human disease | PCP pathway dysfunction | Evidence | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (emphysema) | VANGL2 and SCRIB expression is down-regulated in lung tissue | qRT-PCR analysis with lung tissue | Poobalasingam et al. [13] |

| single nucleotide polymorphism associated with VANGL2 shows interactive effect with smoking on lung function | expression quantitative trait loci analysis | ||

| single nucleotide polymorphism within CELSR1 in females | genome-wide association study with female individuals | Hardin et al. [83] | |

| WNT4 expression is up-regulated in lung tissue | microarray and qRT-PCR analysis with isolated primary airway epithelial cells | Heijink et al. [85]; Durham et al. [86] | |

| WNT5A expression is up-regulated in lung tissue | qRT-PCR and Western blot analysis with lung tissue | Baarsma et al. [84] | |

| increased posttranslationally modified WNT5A in lung tissue | Western blot analysis with lung tissue | ||

| Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis | VANGL1, CELSR1 and SCRIB expression is up-regulated in airway epithelial cells | RNA sequencing of isolated airway epithelial cells | Gokey et al. [77] |

| mislocalization of VANGL1 and SCRIB at apical airway epithelial cell cortex | immunofluorescence localization in isolated airway epithelial cells | ||

| Asthma | single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with genomic region containing FZD3 and FZD6 | genome-wide association study with asthmatic individuals | Barreto-Luis et al. [78] |

| Cystic fibrosis | mislocalization of VANGL1 and PRICKLE2 at apical airway epithelial cell cortex | immunofluorescence localization in airway tissues and primary cultures | Vladar et al. [12] |

| Chronic rhinosinusitis | mislocalization of VANGL1 and PRICKLE2 at apical airway epithelial cell cortex | immunofluorescence localization in airway tissues and primary cultures | Vladar et al. [12] |

| WDPCP expression is up-regulated in sinonasal epithelium | qRT-PCR analysis with sinonasal epithelium | Ma et al. [79] | |

| WNT4 expression is up-regulated in sinonasal epithelium | microarray and qRT-PCR analysis and immunofluorescence localization with sinonasal tissue | Böscke et al. [76] | |

| Idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension | DVL1, DAAM1, RAC1, RHOA and ROCK expression is up-regulated in pulmonary arteries | qRT-PCR analysis with laser-microdissected pulmonary arteries and immunolabeling of endothelial cells | Laumanns et al. [92] |

| FZD7 and CDC42 expression is decreased in pericytes | qRT-PCR and Western blot analysis with isolated primary pericytes | Yuan et al. [88] | |

| WNT5A expression is decreased in endothelial cells | qRT-PCR and Western blot analysis with isolated primary endothelial cells |

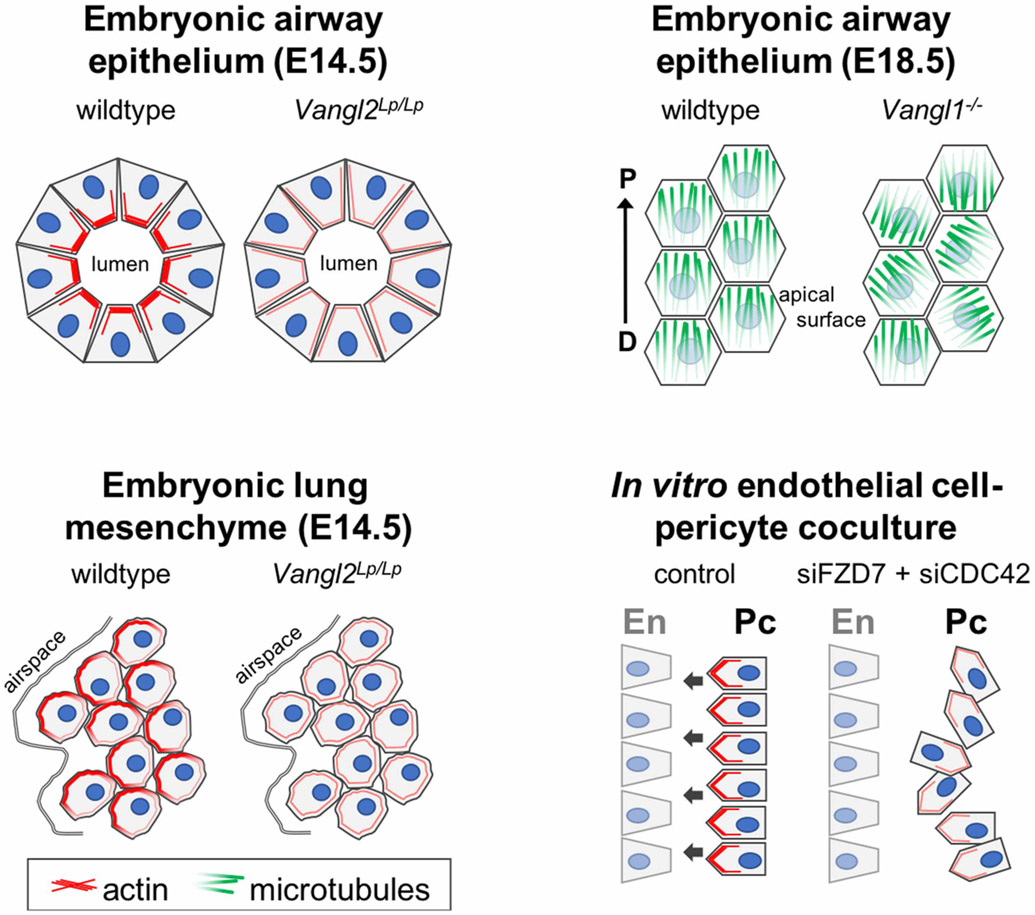

Figure 2. PCP regulates directional cell behaviors through polarized cytoskeletal organization.

During embryonic branching morphogenesis, PCP regulates the accumulation of actin bundles under the luminal cell surface in airway epithelial cells, as indicated by the lack of actin enrichment in Vangl2Lp/Lp airway epithelial cell surfaces (top left). At the same time, mesenchymal cells display a polarized cortical actin network (bottom left), which is absent from Vangl2Lp/Lp lungs, schematics adapted from Yates et al. [36]. Post-branching, PCP establishes a proximal-distal (P-D) oriented microtubule cytoskeleton under the apical cell surface in airway epithelial cells, which is responsible for the proximal directed orientation of motile cilia (top right), however in Vangl1−/− epithelia, the microtubules are not P-D aligned, schematic adapted from Vladar et al. [60]. PCP controls the efficient directional migration of pericytes (Pc) towards pulmonary endothelial cells (En) in an in vitro assay of angiogenesis by establishing a polarized actin cytoskeleton (bottom right), as indicated by the loss of actin enrichment in pericytes depleted of FZD7 and CDC42 using RNA interference (siFZD7 + siCDC42), schematic adapted from Yuan et al. [95].

Upstream cues that provide directional input for core PCP-driven polarized cell behaviors during branching remain unknown, although Wnt ligands are attractive candidates. Multiple Wnts are expressed in both the epithelial and mesenchymal compartments of the developing lung and have been implicated in proliferative and polarized morphogenetic events through canonical and noncanonical pathways during organogenesis [41-43]. Epithelial deletion of Wntless, a G-protein coupled receptor indispensable for Wnt secretion [44] interferes with branching morphogenesis and distal lung development, whereas mesenchymal deletion does not impact branching [45]. Furthermore, epithelial Wnts are thought to act through a noncanonical program as canonical Wnt activation is insufficient to rescue the branching phenotype of the epithelial Wntless mutants [45]. Wnt5a, considered to be the prototypical noncanonical ligand [4], has emerged as a critical regulator of lung development [43]. Wnt5a is expressed both in the epithelium and the mesenchyme from the onset of lung formation, with a concentration at the tip and surrounding the branching airways [43]. Mutants display expanded and abnormally branched distal airways characterized by cellular overgrowth and lack of alveolar maturation accompanied by excessive proliferation [43]. Conversely, epithelial overexpression of Wnt5a leads to reduced branching [46]. Fgf, Bmp and Shh signaling are altered in the Wnt5a mutants, indicating signaling cross-talk among these pathways [46,47]. Wnt5a is thought act in a noncanonical manner in distal morphogenesis, as it requires the noncanonical co-receptor Ror2 [48], and its overexpression does not lead to β-cat activation [47]. Mutants in Wnt4, a ligand that has been shown to act both canonically and noncanonically in the kidney [49,50], breast [51] and male and female sexual [52] development, also have hypoplastic lungs as well as abnormal tracheal cartilage ring formation [53]. This raises the possibility that multiple Wnts act to pattern and shape the airway axis during development.

Whether Wnt4 or Wnt5a provide upstream input for PCP signaling in branching remains untested. The involvement of Wnt5a in PCP is supported by the short and wide trachea [43] in Wnt5a mouse mutants, which is reminiscent of the tissue axis elongation phenotypes seen in some developmental PCP mutants [54-56]. However, unlike the epithelial PCP-driven convergent extension movements and oriented cell divisions that narrow and lengthen kidney tubules [57,58], tracheal elongation was shown to depend on mesenchymally secreted Wnt5a controlling the alignment of smooth muscle cells surrounding the developing airway epithelium [59].

PCP signaling is essential for establishing and maintaining airway epithelial structure and function

PCP continues to operate in the developing airway epithelium after its roles in distal branching. The best studied PCP mechanism in the lung controls the proximal-distal orientation of cilia in multiciliated cells to achieve concerted, directional motility, a fundamental requirement for mucociliary clearance [60] (MCC, Figure 1B,C). The epithelium of the conducting airways is patchwork of multiciliated and secretory cells at the luminal surface with an underlying population of basal stem cells [2]. Multiciliated cells project hundreds of cilia from the apical surface [61]. Cilia form during embryogenesis; and due to PCP signaling, their initially unco-ordinated motility is gradually refined for directional and concerted postnatal MCC [60,62].

Anatomically directed MCC depends on uniform cilium orientation within individual cells, among neighboring cells, and along the tissue axis. Airway cilia are oriented by a conserved core PCP mechanism that involves the establishment of asymmetric membrane domains comprised of Frizzled, Dishevelled and Celsr (Flamingo homolog) at the proximal (oral) side and the Vangl, Prickle and Celsr on the distal side adherens junctions in every airway epithelial cell [60]. These asymmetric domains provide a proximal-distal polarity to each cell and through intercellular interactions propagate this polarization along the epithelium (Figure 1B). To acquire proximal directed motility, cilia are oriented toward the proximal PCP core protein membrane domain (containing Frizzled, Dishevelled and Celsr) by PCP-dependent, polarized microtubules that interact with the proximal apical junctions and the base of cilia [60] (Figures 1C, 2). PCP is established prior to multiciliated cell formation [60], thus cilia form in an already planar polarized cell. This mechanism appears to be highly conserved as similar steps have been shown to orient cilia in the multiciliated mammalian oviduct and ependyma [63] and the embryonic frog skin [64]. In situ hybridization shows that Wnts, including Wnt5a and Wnt4 are expressed in the airway epithelium during PCP acquisition and impact ciliary orientation (Vladar et al., manuscript in preparation).

Select PCP proteins also regulate the formation of cilia in multiciliated cells [65]. Dishevelled [66] and the PCP downstream effector homologs Inturned [67], Fuzzy [67], Wdpcp [68] (Fritz in flies) and Flattop [69] have been shown to control the docking of the ciliary basal body to the apical cell surface during ciliogenesis by organizing the apical cytoskeleton network. Celsr mutant mice also display ciliary docking defects [70], however Vangl mutants do not share this phenotype [60]. Since PCP proteins act on the cytoskeleton, it is possible that these phenotypes reflect defects in polarized actin and/or microtubule dynamics, but mechanisms and the relationship between ciliogenesis and ciliary orientation needs further elucidation.

The developmental PCP program that first orients airway cilia for MCC remains active postnatally and in the adult airway epithelium [12,60]. This is in marked contrast with other planar polarized tissues like the cochlear and kidney tubule epithelia [58,71], where PCP is down-regulated after its developmental functions. Airway PCP maintenance involves the expression of additional asymmetrically localized core components specifically in multiciliated cells such as Prickle2, a Vangl binding partner in the distal airway side PCP domain [60] (Figure 1B). This suggests that continued PCP signaling is required to maintain ciliary orientation, possibly by ongoing signaling to the cytoskeleton to stabilize or reinforce the orientation of rapidly beating cilia. Core PCP membrane domains and ciliary orientation are efficiently reestablished after injury [60,72], thus PCP signaling may also remain active in anticipation of frequent epithelial regeneration. Finally, PCP has also been shown to have non-ciliated cell functions. The loss of core PCP components leads to diminished airway epithelial barrier function [12]. Adherens junctional integrity is critical to barrier capacity, and the loss of Vangl2 at the adherens junctions has been shown to disrupt E-cadherin, its chief structural and functional component, in renal epithelial cells [73]. Moreover, Vangl1 and Prickle2 mutant primary airway epithelial cells exhibit defects in directional cell migration during regeneration [12]. Core PCP proteins expressed in migrating cells control directional movement by localizing asymmetrically to cellular protrusions and promoting polarized cytoskeletal dynamics [74,75].

The requirement of PCP for MCC and barrier function, the two chief functions of the airway epithelium, as well as its regeneration, indicate that this pathway is a critical regulator of airway epithelial development and homeostasis. Not surprisingly, core PCP defects were found in a variety of chronic inflammatory airway diseases such as cystic fibrosis (CF), chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS), idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and asthma [12,76-78]. See Table 3 for a list human nonmalignant respiratory diseases and associated PCP defects. Although these conditions have diverse etiologies and distinct disease phenotypes, they all involve detrimental structural and functional changes termed remodeling in the airway epithelium. Remodeling is brought on by cycles of infection, injury and aberrant repair in a chronic inflammatory environment, and is the key driver of symptoms and disease progression [2]. Remodeled airways have defective MCC and barrier and regenerative capacity, all functions controlled by PCP signaling. Consistently, a novel asthma susceptibility locus has been identified near a cluster of Wnt signaling genes that contain FZD3 and FZD6 [78], the Fzd family receptors involved in the airway PCP mechanism for ciliary orientation [60]. Abnormal PCP protein expression and localization were reported in CF (mislocalized VANGL1 and PRICKLE2) [60], CRS (mislocalized VANGL1 and PRICKLE2; increased WDPCP and WNT4 expression) [12,76,79] and IPF (mislocalized VANGL1 and SCRIB; increased VANGL1, CELSR1 and SCRIB expression) [77] airway epithelium, and were linked to inflammatory signaling. CRS is also characterized by exaggerated canonical Wnt signaling [76]. Wnt/β-cat signaling is critical for the early establishment and differentiation of the airway epithelium [80]. Interestingly, prolonged ectopic activation of canonical Wnt signaling blocks PCP [76]. Given the shared molecular components (ex. Frizzled and Dishevelled proteins) between the two pathways, Wnt/β-cat may need to be down-regulated in adult tissues to make these factors available to operate in PCP signaling. Although more mechanistic studies are required, these data suggest that PCP signaling is critical for airway health, and PCP defects may drive epithelial dysfunction in a variety of chronic airway diseases.

Table 3.

Involvement of PCP in nonmalignant human lung disease

| Gene (human symbol) |

Role in PCP | Mouse mutant line | Viability | Lung phenotype | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vangl1 (VANGL1) | core PCP protein | Vangl1CKO | viable | misoriented airway cilia | Vladar et al. [60] |

| Vangl1Gt | viable | misoriented airway cilia | Vladar et al. [60] | ||

| Vangl2 (VANGL2) | core PCP protein | Vangl2 Lp | E18.5 lethal | hypoplastic lungs with fewer branches; thickened interstitial mesenchyme; defective sacculation | Yates et al. [21,36] |

| Vangl2 Lp | E18.5 lethal | misoriented airway cilia | Vladar et al. [60] | ||

| Vangl2Lp heterozygote | viable | airspace enlargement; tissue damage reminiscent of emphysema | Poobalasingam et al. [13] | ||

| Prickle2 (PRICKLE2) | core PCP protein | Prickle2 germline knockout | viable | misoriented airway cilia | Vladar et al. [12] |

| Celsr1 (CELSR1) | core PCP protein | Celsr1 Crsh | E18.5 lethal | hypoplastic lungs with fewer branches; thickened interstitial mesenchyme; defective sacculation | Yates et al. [21,36] |

| Flattop (CFAP126) | putative PCP effector | Fltp germline knockout | viable | ciliogenesis defect due to undocked basal bodies | Gegg et al. [69] |

| Fuzzy (FUZ) | putative PCP effector | Fuz Gt1(neo) | E18.5 lethal | hypoplastic lungs | Gray 2009 [81] |

| Ptk7 (PTK7) | putative noncanonical co-receptor | Chuzhoi | E18.5 lethal | hypoplastic lungs with fewer branches; thickened interstitial mesenchyme; defective sacculation | Paudyal et al. [39] |

| Wntless (WLS) | Wnt secretion regulator | WlsShhCre (epithelial deletion) | P0 lethal | hypoplastic lungs with fewer branches; thickened interstitial mesenchyme; disrupted pulmonary endothelial differentiation | Cornett et al. [45] |

| WlsDermo1Cre (mesenchymal deletion) | E14.5 lethal | lung abnormalities not observed at E14.5 | Cornett et al. [45] | ||

| Wnt4 (WNT4) | Wnt family ligand | Wnt4 germline knockout | E18.5 lethal | hypoplastic lungs; defective cartilage formation | Caprioli et al. [53] |

| Wnt5a (WNT5A) | Wnt family ligand | Wnt5a germline knockout | P0 lethal | short and wide trachea; abnormally branched distal airways; thickened interstitial mesenchyme; defective sacculation; endothelial cell and capillary disorganization | Li et al. [43] |

| SpC-Wnt5a (epithelial overexpression) | viable | reduced epithelial branching | Li et al. [46] | ||

| Wnt5aDermo1Cre (mesenchymal deletion) | not reported | abnormally polarized smooth muscle cells along trachea | Kishimoto et al. [59] | ||

| Wnt5aECKO (endothelial deletion) | viable | Fewer pulmonary microvessels with decreased muscularization and pericyte coverage | Yuan et al. [88] |

PCP and noncanonical Wnt signaling in the adult alveolar epithelium and parenchymal lung disease

Emphysema, one of the diseases that comprises chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) involves progressive and permanent destruction of parenchymal lung tissue [82]. PCP and noncanonical Wnt signaling has been shown to play a central role in the disruption of alveolar homeostasis and the maladaptive endogenous tissue regeneration response that underlies this disease [1]. While Vangl2 homozygous lethal mutant mice contain lungs with severe developmental morphogenetic defects [36], the lungs of the viable heterozygous animals exhibit many of the hallmarks of tissue damage reminiscent of emphysema [13]. These include an abnormal macrophage profile and elevated levels of elastin and the Mmp12 elastin-modifying enzyme. The expression of VANGL2 and its binding partner SCRIB are also down-regulated in emphysematous human lungs [13]. VANGL2 disruption leads to impaired directional migration and delayed wound repair via disrupted actin dynamics in a human alveolar epithelial cell line, a defect shared with PCP mutant airway epithelial cells [12]. WNT5A was proposed as a noncanonical ligand upstream of PCP as exogenous WNT5A greatly accelerates wound closure in the same assay. Finally, a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) near VANGL2 was shown to have an interactive effect with smoking, the major environmental and behavioral risk factor for emphysema [82], on lung function [13]. Similarly, a SNP within the VANGL binding partner CELRS1 gene was found to be associated with COPD among females [83]. These data indicate that compromised PCP signaling may set the stage for disease via disruption of the homeostatic and regenerative functions of the adult lung.

Multiple studies reported that both WNT4 and WNT5A levels are increased in COPD lungs compared with healthy tissues [84-86]. Treatment of immortalized airway epithelial cells with recombinant WNT4 was shown to increase the release of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines alone and additively with cigarette smoke extract exposure, suggesting that it may be involved in the development of airway inflammation in COPD [85,86]. WNT4 was also shown to not activate beta-catenin dependent signaling [85] suggesting that it acts as a noncanonical ligand. Elevated fibroblast-derived Wnt5a was shown to inhibit regeneration and differentiation of alveolar epithelial cells, which is alleviated by reducing Wnt5a expression [84]. Wnt5a is posttranslationally modified in COPD and increased Wnt5a in diseased tissues suppresses canonical Wnt signaling [84]. It is not clear whether these Wnts exert their effects through the PCP pathway, but it is interesting to speculate that switching between Wnt/β-cat and PCP or other noncanonical pathways is a universal feature of Wnt-driven developmental and disease processes. Further investigation is needed to delineate the molecular details of these important mechanisms.

Noncanonical Wnt signaling in pulmonary vascular development and IPAH

The airway tree and airspaces are intimately associated with the pulmonary vasculature and develop interdependently due to extensive epithelial-endothelial interactions [87]. Wnt signaling contributes to this as endothelial deletion of Wntless leads to the clustering of endothelial cells and a lack of vascular tubule formation during early development [45]. This is likely attributed to a Wnt5a secretion defect as similar endothelial cell and capillary disorganization is observed in Wnt5a mutants in both mouse and chick lungs [43,47]. Here also, Wnt5a was shown to act through the Ror2 co-receptor [48], although the signaling mechanisms are not yet established. In vitro, Wnt5a regulates endothelial cell migration via noncanonical Wnt signaling that involves a downstream JNK kinase and Wnt/Calcium pathway. Wnt5a was also shown to regulate VEGF expression [47], a critical factor in vascular development. Wnt5a is also expressed and secreted in extracellular vesicles by endothelial cells [88]. Exosomal Wnt5a is critical for the recruitment, motility and polarity of pericytes, which interact with endothelial cells to promote pulmonary angiogenesis via a noncanonical program downstream of Fzd7 [88,89].

Idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH) is a fatal disease that comprises sustained vasoconstriction with underlying hypertrophy of pulmonary vascular tissues and thrombosis within the pulmonary artery [90,91]. The PCP pathway has been proposed to be critically involved in the regulation of vascular remodeling in IPAH. Whole transcriptome gene expression profiling first identified an aberrant PCP signature in microdissected IPAH pulmonary arteries [92]. These studies showed that the noncanonical ligand WNT11, the Frizzled receptor binding partner Dishevelled (Dvl), and downstream actin cytoskeleton regulators, Daam1, Rock, RhoA, and Rac1 are strongly up-regulated in IPAH. Expression was confirmed by immunolabeling in the endothelial layer [92]. A separate study did not confirm the presence of WNT11 in pulmonary arteries, but demonstrated that Dvl2 and Daam1 are also present in the surrounding smooth muscle cells [93]. Importantly, the PCP signature was not present in a mouse model of IPAH that a involves repeated intratracheal injection of Stachybotrys chartarum, although the model shows the diminished bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling characteristic of the disease [94]. More studies are needed to address the lack of PCP dysfunction in this model.

Developmental studies demonstrated that endothelial cell-pericyte interactions, which are critical for angiogenesis also depend on PCP signaling. This relationship is disrupted in IPAH and may drive the vessel loss in the disease [95]. Pericytes isolated from IPAH tissues are not able to associate with and support the growth of microvascular endothelial tubes in culture. This stems from a defect in the polarized migration of pericytes towards the endothelium, which was shown to derive from an inability to activate PCP signaling through Fzd7 and the downstream factor Ccd42, a key regulator of cell polarity, and to organize a polarized actin cytoskeleton [95] (Figure 2). FZD7 and CDC42 expression is decreased in IPAH pericytes, but restoration of both genes improved endothelial cell-pericyte association and the formation of larger vascular networks [95]. WNT5A, an important upstream regulator of the endothelial-pericyte interaction during angiogenesis is strongly reduced in human IPAH tissues [88]. Wnt5a mutant mice have pulmonary hypertension with fewer pulmonary microvessels with decreased muscularization and pericyte coverage [88]. Thus, Wnt5a driven PCP signaling is thought to contribute to IPAH by reducing the viability of newly formed vessels. The role of Wnt11 was not investigated.

Conclusions and outlook

PCP signaling has been established as an important regulator of cell polarization and migration in virtually all critical compartments of the respiratory system. It is essential to establish, maintain and regenerate proper tissue structure for optimal function. Importantly, aberrant PCP activation has also been documented in a growing number of lung diseases, possibly as a regenerative response gone awry in the presence of environmental or inflammatory insults. This raises the possibility that modulating or modifying PCP activity is a valuable therapeutic goal. Achieving this goal will require a finer delineation of both core PCP and general noncanonical Wnt mechanisms and the relationships between them in the lung. Identification of the pertinent Wnt ligand and Fzd receptor and co-receptor pairs and the relationship between Wnt ligand binding and the core PCP proteins will be critical to this endeavor. The identity and nature of upstream directional cues that instruct the asymmetric localization and activity of the core PCP cassette also remain unknown. Wnt5a has emerged as a critical regulator of noncanonical signaling in pulmonary development and disease, thus the development of strategies that can mimic or restore Wnt5a production is an important goal.

Perspectives.

PCP is a potent regulator of directional cell behaviors, including migration, oriented division and morphological polarization via cytoskeletal organization to build and shape the lung and other organs and tissues during development. Compelling evidence points to a role for PCP in adult tissue maintenance and for PCP dysfunction in a variety of diseases.

PCP controls development and homeostasis in the airway, alveolar and vascular compartments of the lung through its ability to regulate cell migration and polarization via the cytoskeleton to establish and maintain proper tissue structure for optimal function. PCP dysfunction in a variety of pulmonary diseases likely represents a regenerative response gone awry in the presence of environmental or inflammatory insults.

Mechanistic studies using animal and cell culture models are needed to clarify the role of PCP in health and to evaluate it as a therapeutic target in lung disease.

Funding

E.K.V. is supported by a Boettcher Early Career Investigator award.

Abbreviations

- BMP

bone morphogenetic protein

- CF

cystic fibrosis

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CRS

chronic rhinosinusitis

- Dvl

Dishevelled

- Fzd

Frizzled

- IPAH

idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension

- IPF

idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- MCC

mucociliary clearance

- PCP

planar cell polarity

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- Vangl2

Van Gogh-like2

- Wnt/β-cat

Beta-catenin-dependent pathway

Footnotes

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests associated with the manuscript.

References

- 1.Baarsma HA and Konigshoff M (2017) ‘WNT-er is coming’: WNT signalling in chronic lung diseases. Thorax 72, 746–759 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-209753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beers MF and Morrisey EE (2011) The three R’s of lung health and disease: repair, remodeling, and regeneration. J. Clin. Invest 121, 2065–2073 10.1172/JCI45961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nusse R and Clevers H (2017) Wnt/β-catenin signaling, disease, and emerging therapeutic modalities. Cell 169, 985–999 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xiao Q, Chen Z, Jin X, Mao R and Chen Z (2017) The many postures of noncanonical Wnt signaling in development and diseases. Biomed. Pharmacother 93, 359–369 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.06.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De A (2011) Wnt/Ca2+ signaling pathway: a brief overview. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. (Shanghai) 43, 745–756 10.1093/abbs/gmr079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vladar EK, Antic D and Axelrod JD (2009) Planar cell polarity signaling: the developing cell’s compass. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 1, a002964 10.1101/cshperspect.a002964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mikels AJ and Nusse R (2006) Purified Wnt5a protein activates or inhibits beta-catenin-TCF signaling depending on receptor context. PLoS Biol. 4, e115 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Voloshanenko O, Gmach P, Winter J, Kranz D and Boutros M (2017) Mapping of Wnt-Frizzled interactions by multiplex CRISPR targeting of receptor gene families. FASEB J. 31, 4832–4844 10.1096/fj.201700144R [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo N, Hawkins C and Nathans J (2004) Frizzled6 controls hair patterning in mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A 101, 9277–9281 10.1073/pnas.0402802101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ueno N and Greene ND (2003) Planar cell polarity genes and neural tube closure. Birth Defects Res. C Embryo Today 69, 318–324 10.1002/bdrc.10029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ezan J and Montcouquiol M (2013) Revisiting planar cell polarity in the inner ear. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol 24, 499–506 10.1016/j.semcdb.2013.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vladar EK, Nayak JV, Milla CE and Axelrod JD (2016) Airway epithelial homeostasis and planar cell polarity signaling depend on multiciliated cell differentiation. JCI Insight 1, e88027 10.1172/jci.insight.88027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poobalasingam T, Yates LL, Walker SA, Pereira M, Gross NY, Ali A et al. (2017) Heterozygous Vangl2(Looptail) mice reveal novel roles for the planar cell polarity pathway in adult lung homeostasis and repair. Dis. Model. Mech 10, 409–423 10.1242/dmm.028175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodrich LV and Strutt D (2011) Principles of planar polarity in animal development. Development 138, 1877–1892 10.1242/dev.054080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Montcouquiol M, Rachel RA, Lanford PJ, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA and Kelley MW (2003) Identification of Vangl2 and Scrb1 as planar polarity genes in mammals. Nature 423, 173–177 10.1038/nature01618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walsh GS, Grant PK, Morgan JA and Moens CB (2011) Planar polarity pathway and Nance-Horan syndrome-like 1b have essential cell-autonomous functions in neuronal migration. Development 138, 3033–3042 10.1242/dev.063842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Courbard JR, Djiane A, Wu J and Mlodzik M (2009) The apical/basal-polarity determinant Scribble cooperates with the PCP core factor Stbm/Vang and functions as one of its effectors. Dev. Biol 333, 67–77 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.06.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Antic D, Stubbs JL, Suyama K, Kintner C, Scott MP and Axelrod JD (2010) Planar cell polarity enables posterior localization of nodal cilia and left-right axis determination during mouse and Xenopus embryogenesis. PLoS ONE 5, e8999 10.1371/journal.pone.0008999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murdoch JN, Doudney K, Paternotte C, Copp AJ and Stanier P (2001) Severe neural tube defects in the loop-tail mouse result from mutation of Lpp1, a novel gene involved in floor plate specification. Hum. Mol. Genet 10, 2593–2601 10.1093/hmg/10.22.2593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tao H, Manak JR, Sowers L, Mei X, Kiyonari H, Abe T et al. (2011) Mutations in prickle orthologs cause seizures in flies, mice, and humans. Am. J. Hum. Genet 88, 138–149 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yates LL, Papakrivopoulou J, Long DA, Goggolidou P, Connolly JO, Woolf AS et al. (2010) The planar cell polarity gene Vangl2 is required for mammalian kidney-branching morphogenesis and glomerular maturation. Hum. Mol. Genet 19, 4663–4676 10.1093/hmg/ddq397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramsbottom SA, Sharma V, Rhee HJ, Eley L, Phillips HM, Rigby HF et al. (2014) Vangl2-regulated polarisation of second heart field-derived cells is required for outflow tract lengthening during cardiac development. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004871 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang J, Mark S, Zhang X, Qian D, Yoo S-J, Radde-Gallwitz K et al. (2005) Regulation of polarized extension and planar cell polarity in the cochlea by the vertebrate PCP pathway. Nat. Genet 37, 980–985 10.1038/ng1622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kibar Z, Salem S, Bosoi CM, Pauwels E, De Marco P, Merello E et al. (2011) Contribution of VANGL2 mutations to isolated neural tube defects. Clin. Genet 80, 76–82 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01515.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kibar Z, Torban E, McDearmid JR, Reynolds A, Berghout J, Mathieu M et al. (2007) Mutations in VANGL1 associated with neural-tube defects. N. Engl. J. Med 356, 1432–1437 10.1056/NEJMoa060651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu J, Roman AC, Carvajal-Gonzalez JM and Mlodzik M (2013) Wg and Wnt4 provide long-range directional input to planar cell polarity orientation in Drosophila. Nat. Cell Biol 15, 1045–1055 10.1038/ncb2806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Minegishi K, Hashimoto M, Ajima R, Takaoka K, Shinohara K, Ikawa Y et al. (2017) A Wnt5 activity asymmetry and intercellular signaling via PCP proteins polarize node cells for left-right symmetry breaking. Dev. Cell 40, 439–52 e4 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qian D, Jones C, Rzadzinska A, Mark S, Zhang X, Steel KP et al. (2007) Wnt5a functions in planar cell polarity regulation in mice. Dev. Biol 306, 121–133 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao B, Ajima R, Yang W, Li C, Song H, Anderson MJ et al. (2018) Coordinated directional outgrowth and pattern formation by integration of Wnt5a and Fgf signaling in planar cell polarity. Development 145, dev163824 10.1242/dev.163824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matis M and Axelrod JD (2013) Regulation of PCP by the Fat signaling pathway. Genes Dev. 27, 2207–2220 10.1101/gad.228098.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fulford AD and McNeill H (2019) Fat/Dachsous family cadherins in cell and tissue organisation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol 62, 96–103 10.1016/j.ceb.2019.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saburi S, Hester I, Fischer E, Pontoglio M, Eremina V, Gessler M et al. (2008) Loss of Fat4 disrupts PCP signaling and oriented cell division and leads to cystic kidney disease. Nat. Genet 40, 1010–1015 10.1038/ng.179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mao Y, Mulvaney J, Zakaria S, Yu T, Morgan KM, Allen S et al. (2011) Characterization of a Dchs1 mutant mouse reveals requirements for Dchs1-Fat4 signaling during mammalian development. Development 138, 947–957 10.1242/dev.057166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schittny JC (2017) Development of the lung. Cell Tissue Res. 367, 427–444 10.1007/s00441-016-2545-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moura RS, Carvalho-Correia E, daMota P and Correia-Pinto J (2014) Canonical Wnt signaling activity in early stages of chick lung development. PLoS ONE 9, e112388 10.1371/journal.pone.0112388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yates LL, Schnatwinkel C, Murdoch JN, Bogani D, Formstone CJ, Townsend S et al. (2010) The PCP genes Celsr1 and Vangl2 are required for normal lung branching morphogenesis. Hum. Mol. Genet 19, 2251–2267 10.1093/hmg/ddq104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Plosa EJ, Gooding KA, Zent R and Prince LS (2012) Nonmuscle myosin II regulation of lung epithelial morphology. Dev. Dyn 241, 1770–1781 10.1002/dvdy.23866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pecci A, Ma X, Savoia A and Adelstein RS (2018) MYH9: structure, functions and role of non-muscle myosin IIA in human disease. Gene 664, 152–167 10.1016/j.gene.2018.04.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paudyal A, Damrau C, Patterson VL, Ermakov A, Formstone C, Lalanne Z et al. (2010) The novel mouse mutant, chuzhoi, has disruption of Ptk7 protein and exhibits defects in neural tube, heart and lung development and abnormal planar cell polarity in the ear. BMC Dev. Biol 10, 87 10.1186/1471-213X-10-87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu X, Borchers AG, Jolicoeur C, Rayburn H, Baker JC and Tessier-Lavigne M (2004) PTK7/CCK-4 is a novel regulator of planar cell polarity in vertebrates. Nature 430, 93–98 10.1038/nature02677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller MF, Cohen ED, Baggs JE, Lu MM, Hogenesch JB and Morrisey EE (2012) Wnt ligands signal in a cooperative manner to promote foregut organogenesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A 109, 15348–15353 10.1073/pnas.1201583109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lako M, Strachan T, Bullen P, Wilson DI, Robson SC and Lindsay S (1998) Isolation, characterisation and embryonic expression of WNT11, a gene which maps to 11q13.5 and has possible roles in the development of skeleton, kidney and lung. Gene 219, 101–110 10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00393-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li C, Xiao J, Hormi K, Borok Z and Minoo P (2002) Wnt5a participates in distal lung morphogenesis. Dev. Biol 248, 68–81 10.1006/dbio.2002.0729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Das S, Yu S, Sakamori R, Stypulkowski E and Gao N (2012) Wntless in Wnt secretion: molecular, cellular and genetic aspects. Front. Biol. (Beijing) 7, 587–593 10.1007/s11515-012-1200-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cornett B, Snowball J, Varisco BM, Lang R, Whitsett J and Sinner D (2013) Wntless is required for peripheral lung differentiation and pulmonary vascular development. Dev. Biol 379, 38–52 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.03.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li C, Hu L, Xiao J, Chen H, Li JT, Bellusci S et al. (2005) Wnt5a regulates Shh and Fgf10 signaling during lung development. Dev. Biol 287, 86–97 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.08.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Loscertales M, Mikels AJ, Hu JK, Donahoe PK and Roberts DJ (2008) Chick pulmonary Wnt5a directs airway and vascular tubulogenesis. Development 135, 1365–1376 10.1242/dev.010504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Minami Y, Oishi I, Endo M and Nishita M (2010) Ror-family receptor tyrosine kinases in noncanonical Wnt signaling: their implications in developmental morphogenesis and human diseases. Dev. Dyn 239, 1–15 10.1002/dvdy.21991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lyons JP, Mueller UW, Ji H, Everett C, Fang X, Hsieh J-C et al. (2004) Wnt-4 activates the canonical beta-catenin-mediated Wnt pathway and binds Frizzled-6 CRD: functional implications of Wnt/beta-catenin activity in kidney epithelial cells. Exp. Cell Res 298, 369–387 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.04.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kispert A, Vainio S and McMahon AP (1998) Wnt-4 is a mesenchymal signal for epithelial transformation of metanephric mesenchyme in the developing kidney. Development 125, 4225–4234 PMID:9753677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shan J, Jokela T, Peltoketo H and Vainio S (2009) Generation of an allele to inactivate Wnt4 gene function conditionally in the mouse. Genesis 47, 782–788 10.1002/dvg.20566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jeays-Ward K, Dandonneau M and Swain A (2004) Wnt4 is required for proper male as well as female sexual development. Dev. Biol 276, 431–440 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.08.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Caprioli A, Villasenor A, Wylie LA, Braitsch C, Marty-Santos L, Barry D et al. (2015) Wnt4 is essential to normal mammalian lung development. Dev. Biol 406, 222–234 10.1016/j.ydbio.2015.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wallingford JB and Harland RM (2002) Neural tube closure requires dishevelled-dependent convergent extension of the midline. Development 129, 5815–5825 10.1242/dev.00123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang Y and Nathans J (2007) Tissue/planar cell polarity in vertebrates: new insights and new questions. Development 134, 647–658 10.1242/dev.02772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ybot-Gonzalez P, Savery D, Gerrelli D, Signore M, Mitchell CE, Faux CH et al. (2007) Convergent extension, planar-cell-polarity signalling and initiation of mouse neural tube closure. Development 134, 789–799 10.1242/dev.000380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lienkamp SS, Liu K, Karner CM, arroll TJ, Ronneberger O, Wallingford JB et al. (2012) Vertebrate kidney tubules elongate using a planar cell polarity-dependent, rosette-based mechanism of convergent extension. Nat. Genet 44, 1382–1387 10.1038/ng.2452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kunimoto K, Bayly RD, Vladar EK, Vonderfecht T, Gallagher AR and Axelrod JD (2017) Disruption of core planar cell polarity signaling regulates renal tubule morphogenesis but is not cystogenic. Curr. Biol 27, 3120–31 e4 10.1016/j.cub.2017.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kishimoto K, Tamura M, Nishita M, Minami Y, Yamaoka A, Abe T et al. (2018) Synchronized mesenchymal cell polarization and differentiation shape the formation of the murine trachea and esophagus. Nat. Commun 9, 2816 10.1038/s41467-018-05189-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vladar EK, Bayly RD, Sangoram AM, Scott MP and Axelrod JD (2012) Microtubules enable the planar cell polarity of airway cilia. Curr. Biol 22, 2203–2212 10.1016/j.cub.2012.09.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brooks ER and Wallingford JB (2014) Multiciliated cells. Curr. Biol 24, R973–R982 10.1016/j.cub.2014.08.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Francis RJ, Chatterjee B, Loges NT, Zentgraf H, Omran H and Lo CW (2009) Initiation and maturation of cilia-generated flow in newborn and postnatal mouse airway. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol 296, L1067–L1075 10.1152/ajplung.00001.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Guirao B, Meunier A, Mortaud S, Aguilar A, Corsi J-M, Strehl L et al. (2010) Coupling between hydrodynamic forces and planar cell polarity orients mammalian motile cilia. Nat. Cell Biol 12, 341–350 10.1038/ncb2040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mitchell B, Stubbs JL, Huisman F, Taborek P, Yu C and Kintner C (2009) The PCP pathway instructs the planar orientation of ciliated cells in the Xenopus larval skin. Current Biology 19, 924–929 10.1016/j.cub.2009.04.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wallingford JB and Mitchell B (2011) Strange as it may seem: the many links between Wnt signaling, planar cell polarity, and cilia. Genes Dev. 25, 201–213 10.1101/gad.2008011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Park TJ, Mitchell BJ, Abitua PB, Kintner C and Wallingford JB (2008) Dishevelled controls apical docking and planar polarization of basal bodies in ciliated epithelial cells. Nat. Genet 40, 871–879 10.1038/ng.104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Park TJ, Haigo SL and Wallingford JB (2006) Ciliogenesis defects in embryos lacking inturned or fuzzy function are associated with failure of planar cell polarity and Hedgehog signaling. Nat. Genet 38, 303–311 10.1038/ng1753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cui C, Chatterjee B, Lozito TP, Zhang Z, Francis RJ, Yagi H et al. (2013) Wdpcp, a PCP protein required for ciliogenesis, regulates directional cell migration and cell polarity by direct modulation of the actin cytoskeleton. PLoS Biol. 11, e1001720 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gegg M, Böttcher A, Burtscher I, Hasenoeder S, Van Campenhout C, Aichler M et al. (2014) Flattop regulates basal body docking and positioning in mono- and multiciliated cells. eLife 3, e03842 10.7554/eLife.03842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tissir F, Qu Y, Montcouquiol M, Zhou L, Komatsu K, Shi D et al. (2010) Lack of cadherins Celsr2 and Celsr3 impairs ependymal ciliogenesis, leading to fatal hydrocephalus. Nat. Neurosci 13, 700–707 10.1038/nn.2555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Montcouquiol M, Sans N, Huss D, Kach J, Dickman JD, Forge A et al. (2006) Asymmetric localization of Vangl2 and Fz3 indicate novel mechanisms for planar cell polarity in mammals. J. Neurosci 26, 5265–5275 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4680-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vladar EK, Lee YL, Stearns T and Axelrod JD (2015) Observing planar cell polarity in multiciliated mouse airway epithelial cells. Methods Cell Biol. 127, 37–54 10.1016/bs.mcb.2015.01.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nagaoka T, Inutsuka A, Begum K, Bin hafiz K and Kishi M (2014) Vangl2 regulates E-cadherin in epithelial cells. Sci. Rep 4, 6940 10.1038/srep06940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Davey CF, Mathewson AW and Moens CB (2016) PCP signaling between migrating neurons and their planar-polarized neuroepithelial environment controls filopodial dynamics and directional migration. PLoS Genet. 12, e1005934 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Love AM, Prince DJ and Jessen JR (2018) Vangl2-dependent regulation of membrane protrusions and directed migration requires a fibronectin extracellular matrix. Development 145, dev165472 10.1242/dev.165472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Böscke R, Vladar EK, Könnecke M, Hüsing B, Linke R, Pries R et al. (2017) Wnt signaling in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol 56, 575–584 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0024OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gokey JJ, Sridharan A, Xu Y, Green J, Carraro G, Stripp BR et al. (2018) Active epithelial hippo signaling in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. JCI Insight 3, 98738 10.1172/jci.insight.98738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Barreto-Luis A, Corrales A, Acosta-Herrera M, Gonzalez-Colino C, Cumplido J, Martinez-Tadeo J et al. (2017) A pathway-based association study reveals variants from Wnt signalling genes contributing to asthma susceptibility. Clin. Exp. Allergy 47, 618–626 10.1111/cea.12883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ma Y, Sun Y, Jiang L, Zuo K, Chen H, Guo J et al. (2017) WDPCP regulates the ciliogenesis of human sinonasal epithelial cells in chronic rhinosinusitis. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 74, 82–90 10.1002/cm.21351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Malleske DT, Hayes D Jr, Lallier SW, Hill CL and Reynolds SD (2018) Regulation of human airway epithelial tissue stem cell differentiation by β-catenin, P300, and CBP. Stem Cells 36, 1905–1916 10.1002/stem.2906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gray RS, Abitua PB, Wlodarczyk BJ, Szabo-Rogers HL, Blanchard O, Lee I et al. (2009) The planar cell polarity effector Fuz is essential for targeted membrane trafficking, ciliogenesis and mouse embryonic development. Nat. Cell. Biol 11, 1225–1232 10.1038/ncb1966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Agusti A and Hogg JC (2019) Update on the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N. Engl. J. Med 381, 1248–1256 10.1056/NEJMra1900475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hardin M, Cho MH, Sharma S, Glass K, Castaldi PJ, McDonald M-L et al. (2017) Sex-based genetic association study identifies CELSR1 as a possible chronic obstructive pulmonary disease risk locus among women. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol 56, 332–341 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0172OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Baarsma HA, Skronska-Wasek W, Mutze K, Ciolek F, Wagner DE, John-Schuster G et al. (2017) Noncanonical WNT-5A signaling impairs endogenous lung repair in COPD. J. Exp. Med 214, 143–163 10.1084/jem.20160675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Heijink IH, de Bruin HG, van den Berge M, Bennink LJC, Brandenburg SM, Gosens R et al. (2013) Role of aberrant WNT signalling in the airway epithelial response to cigarette smoke in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 68, 709–716 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-201667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Durham AL, McLaren A, Hayes BP, Caramori G, Clayton CL, Barnes PJ et al. (2013) Regulation of Wnt4 in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. FASEB J. 27, 2367–2381 10.1096/fj.12-217083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Woik N and Kroll J (2015) Regulation of lung development and regeneration by the vascular system. Cell. Mol. Life Sci 72, 2709–2718 10.1007/s00018-015-1907-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yuan K, Shamskhou EA, Orcholski ME, Nathan A, Reddy S, Honda H et al. (2019) Loss of endothelium-derived Wnt5a is associated with reduced pericyte recruitment and small vessel loss in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation 139, 1710–1724 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.037642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.de Jesus Perez VA, Alastalo TP, Wu JC, Axelrod JD, Cooke JP, Amieva M et al. (2009) Bone morphogenetic protein 2 induces pulmonary angiogenesis via Wnt-β-catenin and Wnt-RhoA-Rac1 pathways. J. Cell Biol 184, 83–99 10.1083/jcb.200806049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tuder RM, Marecki JC, Richter A, Fijalkowska I and Flores S (2007) Pathology of pulmonary hypertension. Clin. Chest Med 28, 23–42 10.1016/j.ccm.2006.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Vonk-Noordegraaf A, Haddad F, Chin KM, Forfia PR, Kawut SM, Lumens J et al. (2013) Right heart adaptation to pulmonary arterial hypertension: physiology and pathobiology. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol 62, D22–D33 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Laumanns IP, Fink L, Wilhelm J, Wolff J-C, Mitnacht-Kraus R, Graef-Hoechst S et al. (2009) The noncanonical WNT pathway is operative in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol 40, 683–691 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0153OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yanai S, Wakayama M, Nakayama H, Shinozaki M, Tsukuma H, Tochigi N et al. (2017) Implication of overexpression of dishevelled-associated activator of morphogenesis 1 (Daam-1) for the pathogenesis of human Idiopathic Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (IPAH). Diagn. Pathol 12, 25 10.1186/s13000-017-0614-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Shimodaira K, Okubo Y, Ochiai E, Nakayama H, Katano H, Wakayama M et al. (2012) Gene expression analysis of a murine model with pulmonary vascular remodeling compared to end-stage IPAH lungs. Respir. Res 13, 103 10.1186/1465-9921-13-103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yuan K, Orcholski ME, Panaroni C, Shuffle EM, Huang NF, Jiang X et al. (2015) Activation of the Wnt/planar cell polarity pathway is required for pericyte recruitment during pulmonary angiogenesis. Am. J. Pathol 185, 69–84 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.09.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]