Abstract

Microglia, the innate immune cells of the brain, have recently been removed from the position of mere sentinels and promoted to the role of active sculptors of developing circuits and cells. Alongside their functions in normal brain development, microglia coordinate sexual differentiation of the brain, a set of processes which vary by region and endpoint like that of microglia function itself. In this review, we highlight the ways microglia are both targets and drivers of brain sexual differentiation. We examine the factors that may drive sex differences in microglia, with a special focus on how changing microenvironments in the developing brain dictate microglia phenotypes and discuss how their diverse functions sculpt lasting sex-specific changes in the brain. Finally, we consider how sex-specific early life environments contribute to epigenetic programming and lasting sex differences in microglia identity.

Keywords: behavior, brain development, epigenetics, microglia, sex differences, sexual differentiation

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Brain development requires a complex sequence of events that coordinates numerous physiological processes and cell types in a time- and region-dependent manner. Microglia are necessary for proper brain development; these dynamic innate immune cells rapidly detect and respond to the diverse environmental cues of the developing brain. In this way, microglia both shape and are shaped by the developmental trajectory of the brain, making them indispensable for the formation of healthy neural circuitry and behavior.

In addition to facilitating normal brain development, microglia are essential for sexual differentiation of the brain, as demonstrated in the rat. Sexual differentiation occurs during a critical period in perinatal development and establishes life-long sex differences in both brain and behavior. Microglia display markedly different phenotypes between males and females in several brain regions during this critical period and carry out a number of functions to coordinate the development of sex-specific circuitry. As such, microglia are a point of convergence between sexual differentiation and immune function and therefore likely candidates to mediate the sex differences in clinical prevalence of a number of developmental neuropsychiatric disorders. These disorders include autism spectrum disorders and early-onset schizophrenia, both of which are characterized by immune dysregulation, suggesting that the normal functions that microglia carry out in brain development may be disrupted in conditions of dysfunction (see McCarthy, Nugent, & Lenz, 2017 for review). To better understand how developmental processes may go awry and manifest as a disorder, it is important to know how microglia shape healthy brain development, and perhaps more importantly, how they shape development similarly or differently in males and females.

In this issue of Glia, we present coordinated reviews on sex differences in microglia function. The purpose is to identify the emerging questions surrounding microglia, sex differences, and brain development. While the review by Bordt, Ceasrine, and Bilbo in this issue focuses on intrinsic factors that contribute to microglia identity and function (i.e., chromosomal complement, ontogeny, heterogeneity, and metabolic programming), our review focuses on how the changing landscape of the developing brain influences (and programs) microglia identity and function (i.e., hormonal contributions, bidirectional communication between microglia and their microenvironment) throughout the lifespan.

2 |. SEXUAL DIFFERENTIATION OF THE BRAIN

Sexual differentiation is a process by which the brain develops male- or female-typical characteristics. These characteristics are established early in development, are enduring, and ensure that an organism’s behavior (e.g., mating, parenting, etc.) matches its gonadal phenotype to promote reproductive success. In mammals, this is accomplished by a combination of intrinsic (e.g., sex chromosome) and extrinsic (e.g., hormone exposure, environment) factors (see McCarthy, de Vries, & Forger, 2017 for review).

Sexual differentiation begins in embryonic development and occurs largely as a result of sex determination: The process by which an organism’s genetic sex determines its gonadal sex. Sex determination depends on sex chromosome composition which, in mammals, is either XX (for females) or XY (for males). The Y chromosome, which is paternally transmitted to the offspring, contains the Sry gene that initiates a cascade of events leading to the formation of testes from the bipotential gonad (Goodfellow & Lovell-Badge, 1993; Koopman, Gubbay, Vivian, Goodfellow, & Lovell-Badge, 1991). In the absence of Sry, as for genetic females, the bipotential gonad will develop into ovaries (Eggers & Sinclair, 2012).

As the testes mature during the later stages of embryonic development, they begin to produce testosterone. This prenatal “androgen surge” is transient, starting between embryonic days (E) 16–18 in the rodent and concluding just after birth (Konkle & McCarthy, 2011; Weisz & Ward, 1980). Once in the brain, circulating testosterone binds directly to androgen receptors or is locally aromatized into estradiol (in specific regions expressing the aromatase enzyme) where it can then bind to estrogen receptors (ERα and ERβ). Both androgen and estrogen receptors act as transcription factors that, upon binding their ligands, translocate to the nucleus to affect gene transcription (O’Malley & Tsai, 1992). Steroid receptors can also indirectly influence gene expression by altering the epigenome by recruiting or impacting DNA-modifying enzyme activity or histone-modifying enzymes (Foulds et al., 2013; McKenna & O’Malley, 2002; Nugent et al., 2015; Perissi & Rosenfeld, 2005; Yi et al., 2015).

By influencing the transcriptional profile of the developing brain, gonadal hormones are able to impart their “organizational” effects. That is, early life hormone exposure serves to program further brain development and modify circuitry that is necessary for the expression of sex-specific behaviors later in life. At maturity (i.e., postpuberty), the reintroduction of gonadal hormones can then “activate” this circuitry, which allows for the expression of these behaviors. Collectively, this is known as the organizational/activational hypothesis (Phoenix, Goy, Gerall, & Young, 1959). Essential to this hypothesis is the notion that developmental hormone exposure occurs during a “critical period”—a time during which the brain is especially sensitive to the influence of hormones. In rodent models, the fact that the critical period extends into postnatal life allows for easier manipulation of sex-specific brain development. By administering exogenous testosterone to female pups shortly after birth (to mimic the prenatal androgen surge), the developing female brain and later-life behavior can be masculinized independent of sex chromosome complement or gonadal phenotype. Outside of this critical period (after the first postnatal week in rodents), the brain can no longer be organized by hormone exposure (McCarthy, Herold, & Stockman, 2018).

Both testosterone and estradiol (enzymatically converted from testosterone) are capable of imparting organizational effects on the brain, but the mechanism by which this happens differs greatly across region and behavioral circuit (McCarthy, de Vries, & Forger, 2017; Zuloaga, Puts, Jordan, & Breedlove, 2008). In males, exposure to both steroid hormones initiates the parallel processes of masculinization (development of the male-typical phenotype) and defeminization (repression of the female-typical phenotype). Alternatively, the developing female brain undergoes feminization (development of the female-typical phenotype) which, while far less studied than masculinization, appears to be equally as active, as it requires the prevention of masculinization via epigenetic regulation (Nugent et al., 2015). Thus, while females do not experience the same surge in gonadal hormones as males do, the female brain engages in mechanisms to ensure the appropriate development of female-typical behavior while preventing the development of male-typical behavior.

However, not all sexual differentiation is due to gonadal hormones. Every cell within the body differs in their X and Y chromosomal complement, and this will invariably affect the way the brain develops between the sexes (Arnold, 2017). Chromosomal-sex-specific gene expression is detectable in the developing mouse brain as early as E10.5, prior to the maturation of the testes and the onset of prenatal androgen production (Dewing, Shi, Horvath, & Vilain, 2003). This sex-chromosomal gene expression has relevance for many brain endpoints; for example, Sry expression within the male substantia nigra regulates tyrosine hydroxylase expression in dopaminergic neurons (Dewing et al., 2006) and expression of Sts, a sex-linked gene encoding steroid sulfatase, is believed to regulate aggressive behavior via modulation of GABA(A) receptor activity (Nicolas et al., 2001). In the context of immune function, both the X chromosome and, to a lesser extent, the Y chromosome harbor a large number of immune-regulatory genes (Case et al., 2013; Fish, 2008). Thus, sexual differentiation of the brain is the result of cooperativity between both chromosomal and hormonal influences, each system putting pressure on the other across a rapidly changing developmental timeline containing critical and sensitive periods.

There are many sex-typical behaviors (e.g., mating, parenting, aggression, etc.) and multiple mechanisms mediating the development of sexually differentiated brain circuitry. However, no single brain is unitarily “male” or “female”; accordingly, understanding how brain development occurs in males and females is not as simple as this dichotomous view between the sexes would have it seem (Joel & Fausto-Sterling, 2016). Brain development, particularly as it pertains to sexual differentiation, is influenced by a number of factors that range from genetic to environmental (McCarthy & Arnold, 2011). As a result, the final product is a mosaic brain that contains parts both male and female and is a culmination of experiences beginning in utero and lasting into adulthood.

3 |. MICROGLIA SHAPE SEX-DEPENDENT AND SEX-INDEPENDENT BRAIN DEVELOPMENT

Microglia progenitors, derived from the embryonic yolk sac, colonize the brain early in development (approximately E9.5 in the rodent), before neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes are differentiated (Alliot, Godin, & Pessac, 1999; Ginhoux et al., 2010; Schulz et al., 2012; Kierdorf et al., 2013). As the brain matures, the microglia population correspondingly expands via a combination of migration and proliferation (Ajami, Bennett, Krieger, Tetzlaff, & Rossi, 2007; Swinnen et al., 2013). By the end of the third postnatal week in the rodent—when much of early brain development is done—microglia will have tiled throughout the brain and attained their adult phenotype of highly ramified, surveillant cells (Davalos et al., 2005; Nikodemova et al., 2015; Nimmerjahn, Kirchhoff, & Helmchen, 2005). The timing of their entry and development within the brain places microglia in a particularly unique position of influence. As brain macrophages, microglia possess an array of tools specifically tuned to sense neural activity and immediately respond to changes in the brain (Davalos et al., 2005; Dissing-Olesen et al., 2014; Fontainhas et al., 2011; Hickman et al., 2013; Kettenmann, Hanisch, Noda, & Verkhratsky, 2011; Li, Du, Liu, Wen, & Du, 2012; Nimmerjahn et al., 2005; Pocock & Kettenmann, 2007; Wake, Moorhouse, Jinno, Kohsaka, & Nabekura, 2009). Thus, they are perfectly poised to respond to as well as direct or guide the rapidly developing brain.

Microglia function and phenotype differ by brain region across time and are largely determined by their local environment (Table 1; Ayata et al., 2018; Böttcher et al., 2019; De Biase et al., 2017; Doorn et al., 2015; Grabert et al., 2016; Masuda et al., 2019; O’Koren et al., 2019; Stowell et al., 2018). During early development, microglia may promote neural proliferation and cell survival by secreting pro-proliferative cytokines (Antony, Paquin, Nutt, Kaplan, & Miller, 2011; Arnó et al., 2014; Morgan, Taylor, & Pocock, 2004; Shigemoto-Mogami et al., 2014; Ueno et al., 2013), while later they may prune superfluous cells by inducing apoptosis and targeted phagocytosis (Ashwell, 1990; Cunningham et al., 2013; Ferrer, Bernet, Soriano, del Rio, & Fonseca, 1990; Marín-Teva et al., 2004; Sierra et al., 2010; VanRyzin et al., 2019; Wakselman et al., 2008). Similarly, microglia facilitate axonal outgrowth and ensure appropriate synaptic connectivity by both promoting and pruning excess synapses (Ji et al., 2013; Lenz et al., 2013; Lim et al., 2013; Miyamoto et al., 2016; Pont-Lezica et al., 2014; Schafer et al., 2012; Squarzoni et al., 2014; Tremblay, Lowery, & Majewska, 2010).

TABLE 1.

Many of the developmental mechanisms by which sex differences are established are also developmental functions modulated by microglia

Abbreviations: AVPV, anteroventral periventricular nucleus; BNST, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis; POA, preoptic area; SDN, sexually dimorphic nucleus; VMN, ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus.

These developmental microglia functions are evolutionarily conserved, found in species ranging from fruit fly and zebrafish to mammals (Casano, Albert, & Peri, 2016; Mazaheri et al., 2014; Sears, Kennedy, & Garrity, 2003; Xu, Wang, Wu, Jin, & Wen, 2016), and facilitate the development of neural circuitry and behavior. Life-long impairment of microglia via mutation of key signaling pathways results in delayed neural circuit maturation and produces learning and social behavior deficits in mature animals (Hoshiko et al., 2012; Paolicelli et al., 2011; Rogers et al., 2011; Zhan et al., 2014). Similarly, transient microglia depletion during postnatal development induces lasting deficits across a number of behavioral domains ranging from fear and anxiety to social and reproductive behaviors, in both a sex-dependent and sex-independent manner (Nelson & Lenz, 2017; VanRyzin, Yu, Perez-Pouchoulen, & McCarthy, 2016).

The majority of developmental processes that require microglia are also sexually differentiated endpoints, including cell proliferation, cell death and survival, and synaptic pruning and synaptogenesis (Table 1). In the rat, microglia themselves are also sexually dimorphic, as sex differences in microglia number, morphology, and function in the developing brain have been reported across many brain regions (Lenz et al., 2013; Schwarz, Sholar, & Bilbo, 2012; VanRyzin et al., 2019). These parallel findings indicate microglia are both targets and drivers of sexual differentiation (VanRyzin, Pickett, & McCarthy, 2018).

4 |. WHAT MAKES A MALE OR FEMALE MICROGLIA?

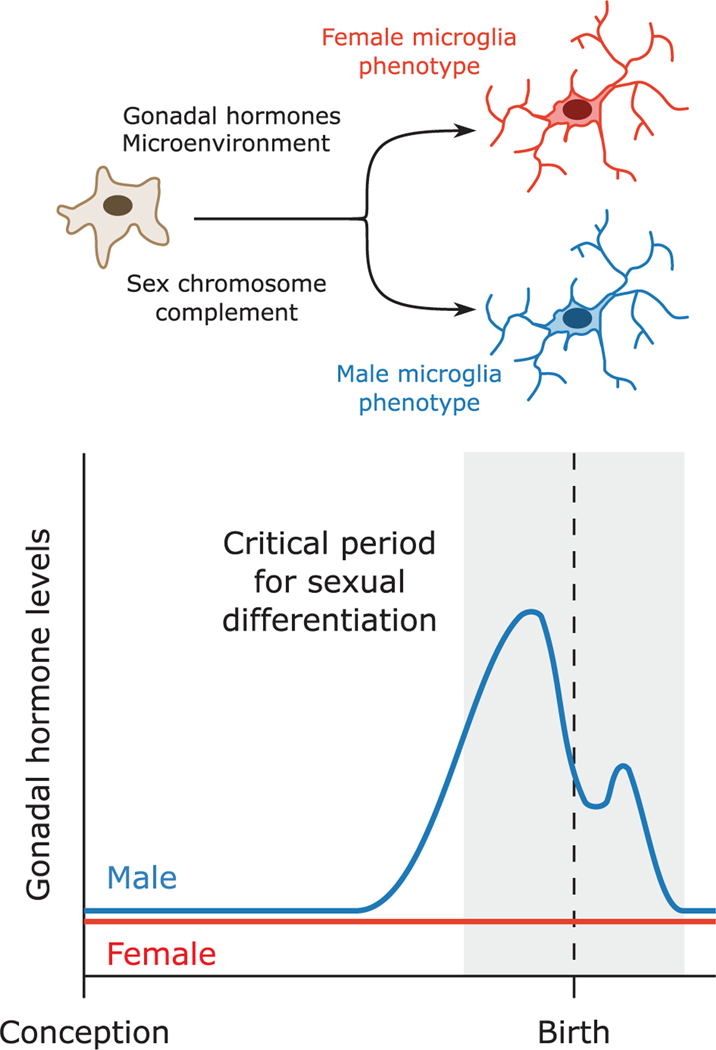

To understand how microglia sculpt sex differences in the brain, it is important to first consider how sex differences in microglia phenotype and function arise. In the developing brain, there are three primary factors that may influence sex-specific microglia phenotype: Sex chromosome complement, gonadal hormone exposure, and microenvironmental signals (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Sexual differentiation and microglia. Sexual differentiation of the brain is largely driven by a male-specific increase in gonadal hormone levels in perinatal development. The onset of hormone exposure defines the beginning of the critical period for sexual differentiation, during which microglia also begin to display sex differences in phenotype and function. These differences may arise from a combination of sex chromosome complement, gonadal hormone exposure, and hormone-induced changes in microenvironmental signals

At the most fundamental level, the main difference between male and female microglia is their chromosome complement (XX for females, XY for males), and the implications for how this may impact microglia function are significant (reviewed in Bordt et al. 2019 in this issue). However, many microglia sex differences are only observable shortly after the prenatal androgen surge and can be modulated by exogenous hormone exposure, implicating gonadal hormones as central to microglia diversity (Lenz et al., 2013; Schwarz et al., 2012; Van-Ryzin et al., 2019).

This implied heterogeneity begs two primary questions: Do hormones act directly on microglia to produce sex differences? Or do hormones act indirectly by modulating microenvironments that impart sex differences in microglia identity and function? In adult animals, microglia express ERα, and estrogens are thought to suppress the production of cytokines (Villa, Vegeto, Poletti, & Maggi, 2016). In contrast, microglial hormone receptor expression is extremely low or undetectable during the early postnatal period (Crain, Nikodemova, & Watters, 2013; Lenz et al., 2013; Sierra, Gottfried-Blackmore, Milner, McEwen, & Bulloch, 2008; Turano, Lawrence, & Schwarz, 2017), suggesting that hormones are unlikely to have a direct modulatory effects on microglia function during this time. Moreover, the sex differences in microglia are unique for each brain region in which they are found, suggesting there is not a unitary response to steroid hormones, but instead a response to the unique local environment in which the microglia reside.

Nearly every facet of microglia—survival, colonization, development, and identity—is shaped by environmentally derived cues (Bennett et al., 2018). Secreted factors, such as colony-stimulating factor 1 and interleukin-34, are necessary for microglia viability (Elmore et al., 2014; Erblich, Zhu, Etgen, Dobrenis, & Pollard, 2011; Greter et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2012; Wei et al., 2010), and other factors, such as transforming growth factor-beta, promote their maturation into an adult phenotype (Bohlen et al., 2017; Butovsky et al., 2014). Microglia colonization is influenced by a number of developmental phenomena—maturation of cell surface markers and secreted factors, progenitor cell proliferation, and apoptosis—in a brain-region- and time-dependent manner (Arnó et al., 2014; Ashwell, 1990; Eyo, Miner, Weiner, & Dailey, 2016; Ferrer et al., 1990; Hoshiko et al., 2012; Lelli et al., 2013; Mosher et al., 2012; Perry, Hume, & Gordon, 1985; Smolders et al., 2017). Together, these environmental signals serve to coordinate the timing of microglia entry and function in parallel with the maturation of specific brain regions. Many of these same developmental phenomena differ by sex in various brain regions in the rat (Table 1), and in several of these regions, microglia number also differs by sex during the critical period for sexual differentiation (Schwarz et al., 2012). Thus, the onset of prenatal hormone exposure initiates a cascade of events that fundamentally change the landscape of the developing brain in a region-dependent manner. Microglia sense these changes and adopt sex-specific phenotypes as a result.

The response to local cues is exemplified in the developing preoptic area (POA) where, in males, testosterone is locally aromatized to estradiol and causes POA-resident mast cells—another immune cell type—to degranulate and release histamine (Lenz et al., 2018). Estradiol-induced histamine release occurs during the critical period and is essential for appropriate sexual differentiation of the developing POA. In response to local histamine release, microglia in the male POA are predictably more amoeboid than in females (Lenz et al., 2013). When female pups are masculinized with exogenous estradiol or treated with compounds to induce mast cell degranulation, their microglia phenotype is correspondingly masculinized (i.e., more amoeboid) compared to control females (Lenz et al., 2013, 2018). As microglia in the neonatal rat POA do not express ERα (Lenz et al., 2013), sex differences in microglia phenotype must be driven by sex differences in the local microenvironment.

Similarly, microglia in the developing rat amygdala respond to sexually dimorphic environmental cues in order to regulate their function. The prenatal androgen surge leads to an increase in the endocannabinoid tone of the male amygdala which lasts for several days—well after testosterone levels have normalized between the sexes (Krebs-Kraft, Hill, Hillard, & McCarthy, 2010). During this same time, the elevated endocannabinoid tone in males drives microglia to become more phagocytic than in females, and the female microglia phenotype can be masculinized (made more phagocytic) by administering testosterone or cannabinoid receptor agonists. By 1 week of life, the critical period is closed and microglia reach a basal level of phagocytosis that is equivalent in males and females (VanRyzin et al., 2019).

In both the POA and amygdala, prenatal hormone exposure induces changes in their respective microenvironments, and it is these microenvironmental signals that drive sex differences in microglia phenotype. The role of hormones, in these cases, is not to directly influence the microglia, but to induce a change in the microenvironment to which the microglia respond accordingly. This is highlighted by the fact that microglia phenotype can be altered independently of sex chromosome or hormonal exposure simply by mimicking the microenvironmental signals. In this way, regional sex differences in brain development coordinate the local microglia population, each region affecting microglia differently during this critical period of development.

5 |. HOW DO MICROGLIA SCULPT LASTING SEX DIFFERENCES IN THE BRAIN?

Many, if not all, of the reported sex differences in microglia morphology and function are transient and evident only during development—lasting at most a few days following birth. Yet, these sex differences have profound and largely permanent effects on the developing brain.

In the POA, microglia integrate sexually dimorphic environmental cues within a very restricted window during early postnatal development to sculpt the synaptic connectivity required for male sex behavior (Figure 2a). The male-specific increase in histamine activates microglial histamine receptors and increases the production of prostaglandin-E2 (PGE2). Microglia-derived PGE2 is necessary and sufficient to drive the process of spinogenesis on developing neurons (Lenz et al., 2013, 2018). By the end of the critical period, male POA neurons will have twice as many dendritic spines, and presumably excitatory synapses, as female neurons, and this synaptic patterning is necessary for the expression of male-typical copulatory behavior in adulthood (Amateau & McCarthy, 2002, 2004; Lenz et al., 2013). Any perturbation of this system, either by affecting microglia (i.e., inhibition or depletion) or by altering the environmental cues that drive microglial PGE2 production (i.e., gonadal hormones, mast cell stabilizing drugs, prenatal allergic inflammation) permanently masculinizes female or impairs male rat sex behavior (Lenz et al., 2013, 2018; Lenz, Pickett, Wright, Galan, & McCarthy, 2019; Van-Ryzin et al., 2016).

FIGURE 2.

Masculinization of the developing preoptic area and medial amygdala. Distinct sexual differentiation processes also involve distinct microglia mechanisms to sculpt individual brain regions during this critical period of development. (a) Within the preoptic area (POA) of males, local conversion of testosterone to estradiol induces POA-resident mast cells to release histamine. Mast cell signaling to microglia triggers an amoeboid phenotype and increases the production of prostaglandin E2, which through a complex signal transduction pathway, increases the density of dendritic spines on POA neurons. In adulthood, masculinization of the POA allows for the expression of male-typical sex behavior. (b) In the medial amygdala of males, testosterone increases the endocannabinoid tone, which promotes microglia phagocytosis. Phagocytic microglia engulf newborn cells that would otherwise develop into astrocytes. As juveniles, a reduction in the astrocyte population of the medial amygdala is necessary for male-typical rough-and-tumble play

Sex differences in microglia function during development also organize lasting changes in the architecture of the medial amygdala, a region responsible for integrating conspecific social information and mediating a sex difference in juvenile rat play behavior (Figure 2b). Microglia are more phagocytic in males than females, as a result of the higher endocannabinoid tone, for the first few days of life. During this time, phagocytic microglia actively engulf viable newborn cells—cells that would otherwise have differentiated into astrocytes. By selectively culling the developing astrocyte population in males, microglia program a sex difference in juvenile rough-and-tumble play behavior. More astrocytes survive this postnatal window in females, which corresponds to lower neuronal activity in the medial amygdala and less frequent and vigorous play behavior as juveniles. Blocking phagocytosis allows more astrocytes to survive in the male amygdala and a corresponding reduction in social play to that normally observed in females (VanRyzin et al., 2019).

Microglia not only organize the circuitry required for the expression of sex-typical social play, but they also reorganize brain circuitry in a sex-specific manner to reduce play at the end of the juvenile period. By pruning dopamine D1 receptor-containing synapses in the nucleus accumbens selectively in males, microglia promote the natural decline in play behavior by rats as the animal transitions into puberty (Kopec, Smith, Ayre, Sweat, & Bilbo, 2018).

6 |. HOW MIGHT SEXUAL DIFFERENTIATION PROGRAM LATER-LIFE MICROGLIA FUNCTION AND SEX DIFFERENCES?

In the previous sections, we highlighted the ways sex differences in developmental microglia phenotypes are programmed by sex differences in the developing brain microenvironments. These sex differences in microglia are short-lived and drive the process of sexual differentiation. While many of these developmental processes are indirectly driven by hormone exposure, the question still remains: Can differential developmental hormone exposure directly program lasting sex differences in adult microglia function?

In the rat, adult microglia exhibit a number of sex differences: Colonization and cell density, morphology, electrophysiological properties, gene expression, and response to inflammatory stimulus (Guneykaya et al., 2018; Hanamsagar et al., 2017; Schwarz et al., 2012; Villa et al., 2018). While the mechanism underlying many of these sex differences has yet to be determined, there is compelling evidence to suggest they have developmental origins. For example, microglia isolated from the healthy adult mouse brain have sex-specific transcriptomes, and these sex differences are independent of circulating hormones (i.e., estrogen or testosterone). When microglia are depleted in the brain of one sex and replaced with microglia from the opposite sex, the transplanted microglia engage in normal function yet still retains the transcriptomic signature of their genetic sex. While these results would suggest that sex-specific features of adult microglia might be the result of sex chromosome composition, the same group demonstrated that masculinizing female pups with exogenous hormone also masculinizes their adult microglia gene expression (Villa et al., 2018). These results indicate that microglia, much like the developing brain, are subject to hormonally mediated sexual differentiation and that early hormone exposure can program lasting differences in microglia function.

7 |. HOW ARE ADULT MICROGLIA SEX DIFFERENCES ESTABLISHED AND MAINTAINED?

Epigenetic programming is one possible mechanism by which the developing microenvironment is able to “imprint” microglia maturation and identity (Amit, Winter, & Jung, 2016; Netea et al., 2016). Microglia-specific deletion of the histone deacetylases HDAC1 and 2 prior to birth impairs microglia development, reduces cell number, and induces lasting alterations in adult microglia morphology (Datta et al., 2018). Moreover, heterogeneity in adult microglia function is driven by signals from the microenvironment and maintained by epigenetic regulation (Ayata et al., 2018).

The mechanism by which epigenetic programming occurs may differ by sex. Both the X and Y chromosomes contain a number of epigenetic regulatory genes, and in some cases, these are differentially expressed in male and female brains. The Y-linked histone lysine demethylase KDM6C (or UTY) is expressed only in males, while the X-linked homologue KDM6A (or UTX) is expressed at higher levels in females (Xu, Deng, & Disteche, 2008; Xu, Deng, Watkins, & Disteche, 2008). Even though males and females both possess an X chromosome, UTX is one of a handful of genes that escape X inactivation—the epigenetic silencing of the second X chromosome copy in females (Greenfield et al., 1998). Thus, even components of the epigenetic machinery are expressed in a sex-specific manner, and this may have significant impact on the way male or female microglia integrate signals derived from the environment and influence their phenotype later in life.

Similarly, the process of sexual differentiation may impart sex-specific epigenetic signatures in the developing microenvironment, which then impart sex-specific effects on microglia function. In the developing POA, and in parallel to the male-specific–microglia-driven PGE2 cascade necessary for masculinization, DNA methylation in females represses the expression of several immunomodulatory genes, including cytokines and chemokines (Nugent et al., 2015). Female-specific immune suppression acts to keep the POA-resident microglia from initiating an errant inflammatory cascade that might induce masculinization, while in males, the genome of the developing POA is permissive and allows for microglia-mediated inflammatory signaling to drive masculinization. This mechanism of dual regulation might be necessary for highly sensitive developmental endpoints during critical periods, a point highlighted by the observation that a single injection of PGE2 at birth is sufficient to induce masculinization of POA neurons and adult sexual behavior in female rats (Wright & McCarthy, 2009).

When do adult microglia begin to express sex-specific phenotypes? In the mouse, embryonic microglia exhibit minimal sex differences in gene expression at the onset of the prenatal androgen surge (Thion et al., 2018), and their developmental trajectory does not differ until well after the second postnatal week (Hanamsagar et al., 2017) suggesting that, at least in the mouse, sex differences may not manifest until after much of early brain development is complete. Much more research is needed to better identify the timing of these events and whether the emergence of adult microglia sex differences coincides with the developmental/adult microglia phenotypic switch. It may be that the transition from a highly plastic phenotype during development to a sexually differentiated adult phenotype is the product of epigenetic regulation (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

A model for understanding microglia sex differences. Sex differences in microglia phenotypes are first apparent during the critical period for sexual differentiation of the brain. At the end of the critical period, sex differences in microglia phenotype often disappear and re-emerge in adulthood, likely in response to the onset of gonadal hormones and new microenvironmental signals during puberty. In parallel, hormones and microenvironmental signals may epigenetically program male and female microglia (blue and red dotted lines) during early development, generating sex differences that manifest later in life

8 |. CONCLUSIONS AND UNANSWERED QUESTIONS

The compilation of current evidence reveals a pivotal role for microglia in establishing sex differences in the developing brain, as well as exhibiting sex differences themselves. The precise mechanism and the endpoints are region-specific and to-date, unique. Steroid hormones derived from the fetal gonad and brain are primary drivers of microglia sex differences but this seems more likely to be indirect, via changes in the local microenvironment to which the microglia respond. Despite these substantial advances, a number of questions remain.

8.1 |. Are microglia involved in other brain regions that undergo sexual differentiation?

Several other brain regions exhibit robust sex differences in cell genesis, cell death, or synaptic connectivity (Table 1), and while microglia function has yet to be examined in many of these regions, they may play a role in the development of these sex differences. For example, females have lower rates of hippocampal cell genesis shortly after birth (Bowers et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2008). During this time, microglia are also more phagocytic in the female hippocampus, and their phagocytic cups colabel for the neural progenitor marker Sox2 (Nelson et al., 2017), suggesting, but not yet demonstrating, that phagocytosis may explain the lower levels of female hippocampal neurogenesis.

8.2 |. Which signals regulate sex differences in microglia colonization?

Microglia colonization and population expansion occurs over a relatively long time in development. Beginning with their initial invasion into the brain around E9.5, the microglia population does not reach its adult size until much later in life. Sex differences in microglia colonization could impact the way the brain develops due to differing number of microglia available to carry out developmental functions. Research is needed to understand the signals that govern sex differences in microglia colonization and population expansion and can provide insight as to whether these differences are the result of sex differences in regional brain development or the result of differential microglia maturation.

8.3 |. How do early life events alter the development and expression of sex-specific microglia phenotypes later in life?

Due to their heightened responsiveness to local environmental signals across their developmental trajectory, microglia are particularly sensitive to the impact of extrinsic cues during the perinatal window. Prenatal high fat diet (Bilbo & Tsang, 2010), prenatal exposure to air pollution (Bolton et al., 2017; Bolton, Auten, & Bilbo, 2014), intrauterine inflammation (Makinson et al., 2017), early life experience or stress (Delpech et al., 2016; Diz-Chaves, Astiz, Bellini, & Garcia-Segura, 2013; Diz-Chaves, Pernía, Carrero, & Garcia-Segura, 2012; Gómez-González & Escobar, 2010; Schwarz, Hutchinson, & Bilbo, 2011), and early life bacterial infection (Bland et al., 2010) all have lasting impact on offspring microglia, affecting activation or number, expression of inflammatory cytokines, and/or the interactions microglia have with other cell types in the brain. Several of these endpoints are sex-specific; for example, the absence of a maternal microbiome disrupts the development of embryonic male microglia and induces lasting alterations in adult female microglia function (Thion et al., 2018). Additionally, prenatal exposure to diesel exhaust particles alters microglia morphology and increases microglia–neuron interactions at postnatal Day 30 in males but not females (Bolton et al., 2017). This sex-specific vulnerability to insult may be reflective of a difference in microglia maturation. Male and female microglia mature throughout the lifespan at different rates, and this trajectory can be altered in a sex-specific manner by exogenous inflammatory stimuli (Hanamsagar et al., 2017). Consequently, depending on the timing of an insult, microglia development may be specifically derailed in one sex and have lasting consequences for adult function.

When questioning how early life events can enduringly impact microglia phenotype it is essential to consider the microenvironment and the possibility that changes to cells in the vicinity of the microglia might actually be the sight of epigenetic or other programming. In this scenario, other cells would indirectly modify microglial function. The number of nearby astrocytes and the activity of neighboring neurons impact microglial morphology, and thereby presumably activation (De Biase et al., 2017), and the response to inflammation induced by LPS administration is different when neurons are present versus when microglia are isolated in pure cultures (Turano et al., 2017). We know that sexual differentiation is highly region specific and involves distinct mechanisms in neurons and astrocytes, thus it is plausible that changes within these cells lock in responses of local microglia to create a coordinated micro-network.

8.4 |. Are we missing essential information about developing microglia and their relevance to sexual differentiation?

Developmental microglia are unique, characterized by functional and transcriptional heterogeneity across developmental “epochs” (Bennett et al., 2016; Hammond et al., 2019; Li et al., 2019; Matcovitch-Natan et al., 2016). Rather than an “immature”, “transitory”, or “pre” microglia state that passively matures into an adult phenotype, developmental microglia are distinct, actively engaging in a different set of functions than adult microglia. Such diversity may be reflective of these cells fulfilling the current “needs” of their developing local environments. By necessity, developmental microglia must be fully equipped to fulfill diverse roles and respond to a multitude of environmental signals (growth factors, neurotransmitters, etc.), because the landscape for which they are responsible for sculpting and guiding is changing. However, microglia cannot be simply categorized based on one parameter. Morphological sex differences may reflect region-specific differences in maturation, or they may reflect microglia function. Even then, microglia function cannot be so easily binned into pro- or anti-inflammatory classifications (Ransohoff, 2016), as many microglia co-express markers of both during development (Crain et al., 2013; Lenz et al., 2013). Viewing developmental microglia from the traditional lens of “adult microglia” may lead to misinterpretation or failure to recognize important features because they do not fit our expectations.

As brain development concludes, epigenetic programming within mature microenvironments likely narrows the responsibilities of resident microglia by stabilizing the newly sculpted circuitry or closing a critical period. In these more homogenous and stable environments, microglia become more specified, losing their multipotential developmental functions in favor of attaining an adult phenotype better suited to modulating neuronal activity/connectivity and surveying the environment within their particular brain region. At this time, sex differences in adult microglia phenotype may manifest, programmed from early life hormone exposure or epigenetic programming, or driven by a new set of microenvironmental signals from the adult brain. It behooves us to consider how the regional microenvironment impacts microglia function, and vice versa, in both development and adulthood to gain a more complete understanding of how sex differences in brain and behavior are established and maintained.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health F31NS093947 to L.A.P., R01MH52716 and R01DA039062 to M.M.M.

Funding information

National Institutes of Health, Grant/Award Numbers: F31NS093947, R01DA039062, R01MH52716

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

REFERENCES

- Ajami B, Bennett JL, Krieger C, Tetzlaff W, & Rossi FM (2007). Local self-renewal can sustain CNS microglia maintenance and function throughout adult life. Nature Neuroscience, 10, 1538–1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alliot F, Godin I, & Pessac B. (1999). Microglia derive from progenitors, originating from the yolk sac, and which proliferate in the brain. Brain Research. Developmental Brain Research, 117, 145–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amateau SK, & McCarthy MM (2002). A novel mechanism of dendritic spine plasticity involving estradiol induction of prostaglandin-E2. The Journal of Neuroscience, 22, 8586–8596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amateau SK, & McCarthy MM (2004). Induction of PGE2 by estradiol mediates developmental masculinization of sex behavior. Nature Neuroscience, 7, 643–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amit I, Winter DR, & Jung S. (2016). The role of the local environment and epigenetics in shaping macrophage identity and their effect on tissue homeostasis. Nature Immunology, 17, 18–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antony JM, Paquin A, Nutt SL, Kaplan DR, & Miller FD (2011). Endogenous microglia regulate development of embryonic cortical precursor cells. The Journal of Neuroscience, 89, 286–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai Y, Sekine Y, & Murakami S. (1996). Estrogen and apoptosis in the developing sexually dimorphic preoptic area in female rats. Neuroscience Research, 25, 430–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnó B, Grassivaro F, Rossi C, Bergamaschi A, Castiglioni V, Furlan R, … Muzio L. (2014). Neural progenitor cells orchestrate microglia migration and positioning into the developing cortex. Nature Communications, 5, 5611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold AP (2017). A general theory of sexual differentiation. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 95, 291–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashwell K. (1990). Microglia and cell death in the developing mouse cerebellum. Brain Research. Developmental Brain Research, 55, 219–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayata P, Badimon A, Strasburger HJ, Duff MK, Montgomery SE, Loh YE, … Schaefer A. (2018). Epigenetic regulation of brain-region specific microglia clearance activity. Nature Neuroscience, 21, 1049–1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett FC, Bennett ML, Yaqoob F, Mulinyawe SB, Grant GA, Hayden Gephart M, … Barress BA (2018). A combination of ontogeny and CNS environment establishes microglial identity. Neuron, 98, 1170–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett ML, Bennett FC, Liddelow SA, Ajami B, Zamanian JL, Fernhoff NB, … Barres BA (2016). New tools for studying microglia in the mouse and human CNS. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113, E1738–E1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilbo SD, & Tsang V. (2010). Enduring consequences of maternal obesity for brain inflammation and behavior of offspring. The FASEB Journal, 24, 2104–2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland ST, Beckley JT, Young S, Tsang V, Watkins LR, Maier SF, & Bilbo SD (2010). Enduring consequences of early-life infection on glial and neural cell genesis within cognitive regions of the brain. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 24, 329–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleier R, Byne W, & Siggelkow I. (1982). Cytoarchitectonic sexual dimorphisms of the medial preoptic and anterior hypothalamic areas in Guinea pig, rat, hamster, and mouse. The Journal of Comparative Neurology, 43, 234–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohlen CJ, Bennett FC, Tucker AF, Collins HY, Mulinyawe SB, & Barres BA (2017). Diverse requirements for microglial survival, specification, and function revealed by defined-medium cultures. Neuron, 94, 759–773.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton JL, Auten RL, & Bilbo SD (2014). Prenatal air pollution exposure induces sexually dimorphic fetal programming of metabolic and neuroinflammatory outcomes in adult offspring. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 37, 30–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton JL, Marinero S, Hassanzadeh T, Natesan D, Belliveau C, Mason SN, … Bilbo SD (2017). Gestational exposure to air pollution alters cortical volume, microglial morphology, and microglia-neuron interactions in a sex-specific manner. Frontiers in Synaptic Neuroscience, 31, 9–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böttcher C, Schlickeiser S, Sneeboer MAM, Kunkel D, Knop A, Paza E, … Priller J. (2019). Human microglia regional heterogeneity and phenotypes determined by multiplexed single-cell mass cytometry. Nature Neuroscience, 22, 78–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers JM, Waddell J, & McCarthy MM (2010). A developmental sex difference in hippocampal neurogenesis is mediated by endogenous oestradiol. Biology of Sex Differences, 1, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butovsky O, Jedrychowski MP, Moore CS, Cialic R, Lanser AJ, Gabriely G, … Weiner HL (2014). Identification of a unique TGF-β-dependent molecular and functional signature in microglia. Nature Neuroscience, 17, 131–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casano AM, Albert M, & Peri F. (2016). Developmental apoptosis mediates entry and positioning of microglia in the zebrafish brain. Cell Reports, 16, 897–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case LK, Wall EH, Dragon JA, Saligrama N, Krementsov DN, Moussawi M, … Teuscher C. (2013). The Y chromosome as a regulatory element shaping immune cell transcriptomes and susceptibility to autoimmune disease. Genome Research, 23, 1474–1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung WC, Swaab DF, & DeVries GJ (2000). Apoptosis during sexual differentiation of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis in the rat brain. Journal of Neurobiology, 43, 234–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson J, & Herbison AE (2006). Postnatal development of kisspeptin neurons in mouse hypothalamus; sexual dimorphism and projections to gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Endocrinology, 147, 5817–5825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crain JM, Nikodemova M, & Watters JJ (2013). Microglia express distinct M1 and M2 phenotypic markers in the postnatal and adult central nervous system in male and female mice. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 91, 1143–1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CL, Martínez-Cerdeño V, & Noctor SC (2013). Microglia regulate the number of neural precursor cells in the developing cerebral cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience, 33, 4216–4233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta M, Staszewski O, Raschi E, Frosch M, Hagemeyer N, Tay TL,… Prinz M. (2018). Histone deacetylases 1 and 2 regulate microglia function during development, homeostasis, and neurodegeneration in a context-dependent manner. Immunity, 48, 514–529.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davalos D, Grutzendler J, Yang G, Kim JV, Zuo Y, Jung S, … Gan WB (2005). ATP mediates rapid microglial response to local brain injury in vivo. Nature Neuroscience, 8, 752–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis EC, Popper P, & Gorski RA (1996). The role of apoptosis in sexual differentiation of the rat sexually dimorphic nucleus of the preoptic area. Brain Research, 734, 10–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Biase LM, Schuebel KE, Fusfeld ZH, Jair K, Hawes IA, Cimbro R, … Bonci A. (2017). Local cues establish and maintain region-specific phenotypes of basal ganglia microglia. Neuron, 95, 341–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries GJ, Buijs RM, & Swaab DF (1981). Ontogeny of the vasopressinergic neurons of the suprachiasmatic nucleus and their extrahypothalamic projections in the rat brain—Presence of a sex difference in the lateral septum. Brain Research, 218, 67–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delpech JC, Wei L, Hao J, Yu X, Madore C, Butovsky O, & Kaffman A. (2016). Early life stress perturbs the maturation of microglia in the developing hippocampus. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 57, 79–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewing P, Chiang CW, Sinchak K, Sim H, Fernagut PO, Kelly S, … Vilain E. (2006). Direct regulation of adult brain function by the male-specific factor SRY. Current Biology, 16, 415–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewing P, Shi T, Horvath S, & Vilain E. (2003). Sexually dimorphic gene expression in mouse brain precedes gonadal differentiation. Brain Research. Molecular Brain Research, 118, 82–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dissing-Olesen L, LeDue JM, Rungta RL, Hefendehl JK, Choi HB, & MacVicar BA (2014). Activation of neuronal NMDA receptors triggers transient ATP-mediated microglial process outgrowth. The Journal of Neuroscience, 34, 10511–10527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diz-Chaves Y, Astiz M, Bellini MJ, & Garcia-Segura LM (2013). Prenatal stress increases the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and exacerbates the inflammatory response to LPS in the hippocampal formation of adult male mice. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 28, 196–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diz-Chaves Y, Pernía O, Carrero P, & Garcia-Segura LM (2012). Prenatal stress causes alterations in the morphology of microglia and the inflammatory response of the hippocampus of adult female mice. Journal of Neuroinflammation, 9, 2094–2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doorn KJ, Brevé JJ, Drukarch B, Boddeke HW, Huitiniga I, Lucassen PJ, & van Dam AM (2015). Brain region-specific gene expression profiles in freshly isolated rat microglia. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 9, 84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggers S, & Sinclair A. (2012). Mammalian sex determination—Insights from humans and mice. Chromosome Research, 20, 215–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmore MR, Najafi AR, Koike MA, Dagher NN, Spangenberg EE, Rice RA, … Green KN (2014). Colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor signaling is necessary for microglia viability, unmasking a microglia progenitor cell in the adult brain. Neuron, 82, 380–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erblich B, Zhu L, Etgen AM, Dobrenis K, & Pollard JW (2011). Absence of colony stimulation factor-1 receptor results in loss of microglia, disrupted brain development and olfactory deficits. PLoS One, 6, e26317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyo UB, Miner SA, Weiner JA, & Dailey ME (2016). Developmental changes in microglial mobilization are independent of apoptosis in the neonatal mouse hippocampus. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 55, 49–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer I, Bernet E, Soriano E, del Rio T, & Fonseca M. (1990). Naturally occurring cell death in the cerebral cortex of the rat and removal of dead cells by transitory phagocytes. Neuroscience, 39, 451–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish EN (2008). The x-files in immunity: Sex-based differences predispose immune responses. Nature Reviews. Immunology, 8, 737–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontainhas AM, Wang M, Liang KJ, Chen S, Mettu P, Damani M, … Wong WT (2011). Microglial morphology and dynamic behavior is regulated by ionotropic glutamatergic and GABAergic neurotransmission. PLoS One, 25, e15973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulds CE, Feng Q, Ding C, Bailey S, Hunsaker TL, Malovannaya A, … O’Malley BW (2013). Proteomic analysis of coregulators bound to ERα on DNA and nucleosomes reveals coregulator dynamics. Molecular Cell, 51, 185–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frade JM, & Barde YA (1998). Microglia-derived nerve growth factor causes cell death in the developing retina. Neuron, 20, 35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginhoux F, Greter M, Leboeuf M, Nandi S, See P, Gokhan S, … Merad M. (2010). Fate mapping analysis reveals that adult microglia derive from primitive macrophages. Science, 330, 841–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-González B, & Escobar A. (2010). Prenatal stress alters microglia development and distribution in postnatal rat brain. Acta Neuropathologica, 119, 303–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow PN, & Lovell-Badge R. (1993). SRY and sex determination in mammals. Annual Review of Genetics, 27, 71–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorski RA, Gordon JH, Shryne JE, & Southam AM (1978). Evidence for a morphological sex difference within the medial preoptic area of the rat brain. Brain Research, 16, 333–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorski RA, Harlan RE, Jacobson CD, Shryne JE, & Southam AM (1980). Evidence for the existence of a sexually dimorphic nucleus in the preoptic area of the rat. The Journal of Comparative Neurology, 15, 529–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotsiridze T, Kang N, Jacob D, & Forger NG (2007). Development of sex differences in the principal nucleus of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis of mice: Role of Bax-dependent cell death. Developmental Neurobiology, 67, 355–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould E, Westlind-Danielsson A, Frankfurt M, & McEwen BS (1990). Sex differences and thyroid hormone sensitivity of hippocampal pyramidal cells. The Journal of Neuroscience, 10, 996–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabert K, Michoel T, Karavolos MH, Clohisey S, Baillie JK, Stevens MP, … McColl BW (2016). Microglial brain region-dependent diversity and selective regional sensitivities to aging. Nature Neuroscience, 19, 504–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield A, Carrel L, Pennisi D, Philippe C, Quaderi N, Siggers P, … Koopman P. (1998). The UTX gene escapes X inactivation in mice and humans. Human Molecular Genetics, 7, 737–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greter M, Lelios I, Pelczar P, Hoeffel G, Price J, Leboeuf M, … Becher B. (2012). Stroma-derived interleukin-34 controls the development and maintenance of langerhans cells and the maintenance of microglia. Immunity, 37, 1050–1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guneykaya D, Ivanov A, Hernandez DP, Haage V, Wojtas B, Meyer N, … Wolf SA (2018). Transcriptional and translational differences of microglia from male and female brains. Cell Reports, 24, 2273–2783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond TR, Dufort C, Dissing-Olesen L, Giera S, Young A, Wysoker A, … Stevens B. (2019). Single-cell RNA sequencing of microglia throughout the mouse lifespan and in the injured brain reveals complex cell-state changes. Immunity, 50, 253–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanamsagar R, Alter MD, Block CS, Sullivan H, Bolton JL, & Bilbo SD (2017). Generation of a microglial developmental index in mice and in humans reveals a sex difference in maturation and immune reactivity. Glia, 65, 1504–1520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman SE, Kingery ND, Ohsumi TK, Borowsky ML, Wang LC, Means TK, & El Khoury J. (2013). The microglial sensome revealed by direct RNA sequencing. Nature Neuroscience, 16, 1896–1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshiko M, Arnoux I, Avignone E, Yamamoto N, & Audinat E. (2012). Deficiency of the microglial receptor CX3CR1 impairs postnatal functional development of thalamocortical synapses in the barrel cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience, 32, 15106–15111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson CD, & Gorski RA (1981). Neurogenesis of the sexually dimorphic nucleus of the preoptic area in the rat. The Journal of Comparative Neurology, 196, 519–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji K, Adgul G, Wollmuth LP, & Tsirka SE (2013). Microglia actively regulate the number of functional synapses. PLoS One, 8, e56293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joel D, & Fausto-Sterling A. (2016). Beyond sex differences: New approaches for thinking about variation in brain structure and function. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 371, 20150451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato Y, Nakashima S, Maekawa F, & Tsukahara S. (2012). Involvement of postnatal apoptosis on sex difference in number of cells generated during late fetal period in the sexually dimorphic nucleus of the preoptic area in rats. Neuroscience Letters, 516, 290–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettenmann H, Hanisch UK, Noda M, & Verkhratsky A. (2011). Physiology of microglia. Physiological Reviews, 91, 461–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kierdorf K, Erny D, Goldmann T, Sander V, Schulz C, Perdiguero EG, … Prinz M. (2013). Microglia emerge from erythromyeloid precursors via Pu.1- and Irf8-dependent pathways. Nature Neuroscience, 16, 273–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konkle AT, & McCarthy MM (2011). Developmental time course of estradiol, testosterone, and dihydrotestosterone levels in discrete regions of male and female rat brain. Endocrinology, 152, 223–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopman P, Gubbay J, Vivian N, Goodfellow P, & Lovell-Badge R. (1991). Male development of chromosomally female mice transgenic for Sry. Nature, 351, 117–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopec AM, Smith CJ, Ayre NR, Sweat SC, & Bilbo SD (2018). Microglial dopamine receptor elimination defines sex-specific nucleus accumbens development and social behavior in adolescent rats. Nature Communications, 9, 3769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs-Kraft DL, Hill MN, Hillard CJ, & McCarthy MM (2010). Sex difference in cell proliferation in developing rat amygdala mediated by endocannabinoids has implications for social behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107, 20535–20540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lelli A, Gervais A, Colin C, Chéret C, Ruiz de Almodovar C, Carmeliet P, … Mallat M. (2013). The NADPH oxidase Nox2 regulates VEGFR1/CSF-1R-mediated microglial chemotaxis and promotes early postnatal infiltration of phagocytes in the subventricular zone of the mouse cerebral cortex. Glia, 61, 1542–1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz KM, Nugent BM, Haliyur R, & McCarthy MM (2013). Microglia are essential to masculinization of brain and behavior. The Journal of Neuroscience, 33, 2761–2772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz KM, Pickett LA, Wright CL, Davis KT, Joshi A, & McCarthy MM (2018). Mast cells in the developing brain determine adult sexual behavior. The Journal of Neuroscience, 38, 8044–8059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz KM, Pickett LA, Wright CL, Galan A, & McCarthy MM (2019). Prenatal allergen exposure perturbs sexual differentiation and programs lifelong changes in adult social and sexual behavior. Scientific Reports, 9, 4837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Cheng Z, Zhou L, Darmanis S, Neff NF, Okamoto J, …Barres BA (2019). Developmental heterogeneity of microglia and brain myeloid cells revealed by deep single-cell RNA sequencing. Neuron, 101, 207–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Du XF, Liu CS, Wen ZL, & Du JL (2012). Reciprocal regulation between resting microglial dynamics and neuronal activity in vivo. Developmental Cell, 23, 1189–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim SH, Park E, You B, Jung Y, Park AR, Park SG, & Lee JR (2013). Neuronal synapse formation induced by microglia and interleukin 10. PLoS One, 8, e81218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makinson R, Lloyd K, Rayasam A, McKee S, Brown A, Barila G, … Reyes TM (2017). Intrauterine inflammation induces sex-specific effects on neuroinflammation, white matter, and behavior. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 66, 277–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marín-Teva JL, Dusart I, Colin C, Gervais A, van Rooijen N, & Mallat M. (2004). Microglia promote the death of developing Purkinje cells. Neuron, 41, 535–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda T, Sankowski R, Staszewski O, Böttcher C, Amann L, Scheiwe C, … Prinz M. (2019). Spatial and temporal heterogeneity of mouse and human microglia at single-cell resolution. Nature, 566, 7744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matcovitch-Natan O, Winter DR, Giladi A, Vargas Aguilar S, Spinrad A, Sarrazin S, … Amit I. (2016). Microglia development follows a stepwise program to regulate brain homeostasis. Science, 353, aad8670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto A, & Arai Y. (1986). Male-female difference in synaptic organization of the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus in the rat. Neuroendocrinology, 42, 232–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazaheri F, Breus O, Durdu S, Haas P, Wittbrodt J, Gilmour D, & Peri F. (2014). Distinct roles for BAI1 and TIM-4 in the engulfment of dying neurons by microglia. Nature Communications, 5, 4046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy MM, & Arnold AP (2011). Reframing sexual differentiation of the brain. Nature Neuroscience, 14, 677–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy MM, de Vries GJ, & Forger NG (2017). Sexual differentiation of the brain: A fresh look at mode, mechanisms, and meaning. In Pfaff DW & Joels M. (Eds.), Hormones, brain and behavior (pp. 3–32). Cambridge, MA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy MM, Herold K, & Stockman SL (2018). Fast, furious and enduring: Sensitive vs critical periods in sexual differentiation of the brain. Physiology & Behavior, 187, 13–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy MM, Nugent BM, & Lenz KM (2017). Neuroimmunology and neuroepigenetics in the establishment of sex differences in the brain. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 18, 471–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna NJ, & O’Malley BW (2002). Combinatorial control of gene expression by nuclear receptors and coregulators. Cell, 108, 465–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MA, Vician L, Clifton DK, & Dorsa DM (1989). Sex differences in vassopressin neurons in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis by in situ hybridization. Peptides, 10, 615–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto A, Wake H, Ishikawa AW, Eto K, Shibata K, Murakoshi H, … Nabekura J. (2016). Microglia contact induces synapse formation in developing somatosensory cortex. Nature Communications, 7, 12540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mong JA, Glaser E, & McCarthy MM (1999). Gonadal steroids promote glia differentiation and alter neuronal morphology in the developing hypothalamus in a regionally specific manner. The Journal of Neuroscience, 19, 1464–1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan SC, Taylor DL, & Pocock JM (2004). Microglia release activators of neuronal proliferation mediated by activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase, phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/Akt and deltanotch signalling cascades. Journal of Neurochemistry, 90, 89–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosher KI, Andres RH, Fukuhara T, Bieri G, Hasegawa-Moriyama M, He Y, … Wyss-Coray T. (2012). Neural progenitor cells regulate microglia functions and activity. Nature Neuroscience, 15, 1485–1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami S, & Arai Y. (1989). Neuronal death in the developing sexually dimorphic periventricular nucleus of the preoptic area in the female rat: Effect of neonatal androgen treatment. Neuroscience Letters, 102, 185–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson LH, & Lenz KM (2017). Microglia depletion in early life programs persistent changes in social, mood-related, and locomotor behavior in male and female rats. Behavioural Brain Research, 316, 279–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson LH, Warden S, & Lenz KM (2017). Sex differences in microglial phagocytosis in the neonatal hippocampus. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 64, 11–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netea MG, Joosten LA, Latz E, Mills KH, Natoli G, Stunnenberg HG, … Xavier RJ (2016). Trained immunity: A program of innate immune memory in health and disease. Science, 352, aaf1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas LB, Pinoteau W, Papot S, Routier S, Guillaumet G, & Mortaud S. (2001). Aggressive behavior induced by the steroid sulfatase inhibitor COUMATE and by DHEAS in CBA/H mice. Brain Research, 20, 216–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikodemova M, Kimyon RS, De I, Small AL, Collier LS, & Watters JJ (2015). Microglial numbers attain adult levels after undergoing a rapid decrease in cell number in the third postnatal week. Journal of Neuroimmunology, 278, 280–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimmerjahn A, Kirchhoff F, & Helmchen F. (2005). Resting microglial cells are highly dynamic surveillants of brain parenchyma in vivo. Science, 308, 1314–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nugent BM, Wright CL, Shetty AC, Hodes GE, Lenz KM, Mahurkar A, … McCarthy MM (2015). Brain feminization requires active repression of masculinization via DNA methylation. Nature Neuroscience, 18, 690–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Koren EG, Yu C, Klingeborn M, Wong AYW, Prigge CL, Mathew R, … Saban DR (2019). Microglial function is distinct in different anatomical locations during retinal homeostasis and degeneration. Immunity, 50, 723–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley BW, & Tsai MJ (1992). Molecular pathways of steroid receptor action. Biology of Reproduction, 46, 163–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paolicelli RC, Bolasco G, Pagani F, Maggi L, Scianni M, Panzanelli P,… Gross CT (2011). Synaptic pruning by microglia is necessary for normal brain development. Science, 333, 1456–1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkhurst CN, Yang G, Ninan I, Savas JN, Yates JR, Lafaille JJ, … Gan WB (2013). Microglia promote learning-dependent synapse formation through brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Cell, 155, 1596–1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perissi V, & Rosenfeld MG (2005). Controlling nuclear receptors: The circular logic of cofactor cycles. Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology, 6, 542–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry VH, Hume DA, & Gordon S. (1985). Immunohistochemical localization of macrophages and microglia in the adult and developing mouse brain. Neuroscience, 15, 313–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phoenix CH, Goy RW, Gerall AA, & Young WC (1959). Organizing action of prenatally administered testosterone propionate on the tissues mediating mating behavior in the female Guinea pig. Endocrinology, 65, 369–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinos H, Collado P, Rodríguez-Zafra M, Rodríguez C, Segovia S, & Guillamón A. (2001). The development of sex differences in the locus coeruleus of the rat. Brain Research Bulletin, 56, 73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pocock JM, & Kettenmann H. (2007). Neurotransmitter receptors on microglia. Trends in Neurosciences, 30, 527–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pont-Lezica L, Beumer W, Colasse S, Drexhage H, Versnel M, & Bessis A. (2014). Microglia shape corpus callosum axon tract fasciculation: Functional impact of prenatal inflammation. The European Journal of Neuroscience, 39, 1551–1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raisman G, & Field PM (1971). Sexual dimorphism in the preoptic area of the rat. Science, 20, 731–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raisman G, & Field PM (1973). Sexual dimorphism in the neuropil of the preoptic area of the rat and its dependence on neonatal androgen. Brain Research, 17, 1–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransohoff RM (2016). A polarizing question: Do M1 and M2 microglia exist? Nature Neuroscience, 19, 987–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid SNM, & Juraska JM (1992). Sex differences in neuron number in the binocular area of the rat visual cortex. The Journal of Comparative Neurology, 321, 448–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers JT, Morganti JM, Bachstetter AD, Hudson CE, Peters MM, Grimmig BA, … Gemma C. (2011). CX3CR1 deficiency leads to impairment of hippocampal cognitive function and synaptic plasticity. The Journal of Neuroscience, 31, 16241–16250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer DP, Lehrman EK, Kautzman AG, Koyama R, Mardinly AR, Yamasaki R, … Stevens B. (2012). Microglia sculpt postnatal neural circuits in an activity and complement-dependent manner. Neuron, 74, 691–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz C, Gomez Perdiguero E, Chorro L, Szabo-Rogers H, Cagnard N, Kierdorf K, … Pollard JW (2012). A lineage of myeloid cells independent of Myb and hematopoietic stem cells. Science, 336, 86–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz JM, Hutchinson MR, & Bilbo SD (2011). Early-life experience decreases drug-induced reinstatement of morphine CPP in adulthood via microglial-specific epigenetic programming of anti-inflammatory IL-10 expression. The Journal of Neuroscience, 31, 17835–17847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz JM, Sholar PW, & Bilbo SD (2012). Sex differences in microglial colonization of the developing rat brain. Journal of Neurochemistry, 120, 948–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sears HC, Kennedy CJ, & Garrity PA (2003). Macrophage-mediated corpse engulfment is required for normal drosophila CNS morphogenesis. Development, 130, 3557–3565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigemoto-Mogami Y, Hoshikawa K, Goldman JE, Sekino Y, & Sato K. (2014). Microglia enhance neurogenesis and oligodendrogenesis in the early postnatal subventricular zone. The Journal of Neuroscience, 34, 2231–2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra A, Encinas JM, Deudero JJ, Chancey JH, Enikolopov G, Overstreet-Wadiche LS, … Maletic-Savatic M. (2010). Microglia shape adult hippocampal neurogenesis through apoptosis-coupled phagocytosis. Cell Stem Cell, 7, 483–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra A, Gottfried-Blackmore A, Milner TA, McEwen BS, & Bulloch K. (2008). Steroid hormone receptor expression and function in microglia. Glia, 56, 659–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simerly RB, Swanson LW, & Gorski RA (1985). Reversal of the sexually dimorphic distribution of serotonin-immunoreactive fibers in the medial preoptic nucleus by treatment with perinatal androgen. Brain Research, 340, 91–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolders SM, Swinnen N, Kessels S, Arnauts K, Smolders S, Le Bras B, … Brône B. (2017). Age-specific function of α5β1 integrin in microglial migration during early colonization of the developing mouse cortex. Glia, 65, 1072–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squarzoni P, Oller G, Hoeffel G, Pont-Lezica L, Rostaing P, Low D, … Garel S. (2014). Microglia modulate wiring of the embryonic forebrain. Cell Reports, 8, 1271–1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowell RD, Wong EL, Batchelor HN, Mendes MS, Lamantia CE, Whitelaw BS, & Majewska AK (2018). Cerebellar microglia are dynamically unique and survey Purkinje neurons in vivo. Developmental Neurobiology, 78, 627–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumida H, Nishizuka M, Kano Y, & Arai Y. (1993). Sex differences in the anteroventral periventricular nucleus of the preoptic area and in the related effects of androgen in prenatal rats. Neuroscience Letters, 151, 41–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinnen N, Smolders S, Avila A, Notelaers K, Paesen R, Ameloot M, … Rigo JM (2013). Complex invasion pattern of the cerebral cortex by microglial cells during development of the mouse embryo. Glia, 61, 150–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thion MS, Low D, Silvin A, Chen J, Grisel P, Schulte-Schrepping J, … Garel S. (2018). Microbiome influences prenatal and adult microglia in a sex-specific manner. Cell, 172, 500–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobet SA, & Fox TO (1989). Sex- and hormone-dependent antigen immunoreactivity in developing rat hypothalamus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 86, 382–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay ME, Lowery RL, & Majewska AK (2010). Microglia interactions with synapses are modulated by visual experience. PLoS One, 8, e100527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turano A, Lawrence JH, & Schwarz JM (2017). Activation of neonatal microglia can be influenced by other neural cells. Neuroscience Letters, 657, 32–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno M, Fujita Y, Tanaka T, Nakamura Y, Kikuta J, Ishii M, & Yamashita T. (2013). Layer V cortical neurons require microglial support for survival during postnatal development. Nature Neuroscience, 16, 543–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vainchtein ID, Chin G, Cho FS, Kelley KW, Miller JG, Chien EC, … Molofsky AV (2018). Astrocyte-derived interleukin-33 promotes microglial synapse engulfment and neural circuit development. Science, 359, 1269–1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanRyzin JW, Marquardt AE, Argue KJ, Vecchiarelli HA, Ashton SE, Arambula SE, … McCarthy MM (2019). Microglial phagocytosis of newborn cells is induced by endocannabinoids and sculpts sex differences in juvenile rat social play. Neuron, 102, 435–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanRyzin JW, Pickett LA, & McCarthy MM (2018). Microglia: Driving critical periods and sexual differentiation of the brain. Developmental Neurobiology, 78, 580–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanRyzin JW, Yu SJ, Perez-Pouchoulen M, & McCarthy MM (2016). Temporary depletion of microglia during the early postnatal period induces lasting sex-depending and sex-independent effects on behavior in rats. eNeuro, 3(6), ENEURO.0297–16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villa A, Gelosa P, Catiglioni L, Cimino M, Rizzi N, Pepe G, … Maggi A. (2018). Sex-specific features of microglia from adult mice. Cell Reports, 23, 3501–3511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villa A, Vegeto E, Poletti A, & Maggi A. (2016). Estrogens, neuroinflammation, and neurodegeneration. Endocrine Reviews, 37, 372–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wake H, Moorhouse AJ, Jinno S, Kohsaka S, & Nabekura J. (2009). Resting microglia directly monitor the functional state of synapses in vivo and determine the fate of ischemic terminals. The Journal of Neuroscience, 29, 3974–3980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakselman S, Béchade C, Roumier A, Bernard D, Triller A, & Bessis A. (2008). Developmental neuronal death in hippocampus requires the microglial CD11b integrin and DAP12 immunoreceptor. The Journal of Neuroscience, 28, 8138–8143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton NM, Sutter BM, Laywell ED, Levkoff LH, Kearns SM, Marshall GP, … Steindler DA (2006). Microglia instruct subventricular zone neurogenesis. Glia, 54, 815–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Szretter KJ, Vermi W, Gilfillan S, Rossini C, Cella M, … Colonna M. (2012). IL-34 is a tissue-restricted ligand of CSF1R required for the development of Langerhans cells and microglia. Nature Immunology, 13, 753–760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei S, Nandi S, Chitu V, Yeung Y-G, Yu W, Huang M, … Stanley ER (2010). Functional overlap but differential expression of CSF-1 and IL-34 in their CSF-1 receptor-mediated regulation of myeloid cells. Journal of Leukocyte Biology, 88, 495–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinhard L, di Bartolomei G, Bolasco G, Machado P, Schieber NL, Neniskyte U, … Gross C. (2018). Microglia remodel synapses by presynaptic trogocytosis and spine head filopodia induction. Nature Communications, 9, 1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinhard L, Neniskyte U, Vadisiute A, di Bartolomei G, Aygün N, Riviere L, … Gross C. (2018). Sexual dimorphism of microglia and synapses during mouse postnatal development. Developmental Neurobiology, 78, 648–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz J, & Ward IL (1980). Plasma testosterone and progesterone titers of pregnant rats, their male and female fetuses, and neonatal offspring. Endocrinology, 106, 306–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright CL, & McCarthy MM (2009). Prostaglandin E2-induced masculinization of brain and behavior requires protein kinase a, AMPA/kainate, and metabotropic glutamate receptor signaling. The Journal of Neuroscience, 29, 13274–13282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu MV, Manoli DS, Fraser EJ, Coats JK, Tollkuhn J, Honda S, … Shah NM (2009). Estrogen masculinizes neural pathways and sex-specific behaviors. Cell, 139, 61–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Deng X, & Disteche CM (2008). Sex-specific expression of the X-linked histone demethylase gene Jarid1c in brain. PLoS One, 3, e2553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Deng X, Watkins R, & Disteche CM (2008). Sex-specific differences in expression of histone demethylases Utx and Uty in mouse brain and neurons. The Journal of Neuroscience, 28, 4521–4527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Wang T, Wu Y, Jin W, & Wen Z. (2016). Microglia colonization of developing zebrafish midbrain is promoted by apoptotic neuron and lysophosphatidylcholine. Developmental Cell, 38, 214–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi P, Wang Z, Feng Q, Pintilie GD, Foulds CE, Lanz RB, … O’Malley BW (2015). Structure of a biologically active estrogen receptor-coactivator complex on DNA. Molecular Cell, 57, 1047–1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan Y, Paolicelli RC, Sforazzini F, Weinhard L, Bolasco G, Pagani F, … Gross CT (2014). Deficient neuron-microglia signaling results in impaired functional brain connectivity and social behavior. Nature Neuroscience, 17, 400–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JM, Konkle AT, Zup SL, & McCarthy MM (2008). Impact of sex and hormones on new cells in the developing rat hippocampus: A novel source of sex dimorphism? The European Journal of Neuroscience, 27, 791–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]