Abstract

Background

There exists a need for prognostic tools for the early identification of COVID-19 patients requiring intensive care unit (ICU) admission and mortality. Here we investigated the association between a clinical (initial prehospital shock index (SI)) and biological (initial prehospital lactatemia) tool and the ICU admission and 30-day mortality among COVID-19 patients cared for in the prehospital setting.

Methods

We retrospectively analysed COVID-19 patients initially cared for by a Paris Fire Brigade advanced (ALS) or basic life support (BLS) team in the prehospital setting between 2020, March 08th and 2020, May 30th. We assessed the association between prehospital SI and prehospital lactatemia and ICU admission and mortality using logistic regression model analysis after propensity score matching with Inverse Probability Treatment Weighting (IPTW) method. Covariates included in the IPTW propensity analysis were: age, sex, body mass index (BMI), initial respiratory rate (iRR), initial pulse oximetry without (SpO2i) and with oxygen supplementation (SpO2i.O2), initial Glasgow coma scale (GCSi) value, initial prehospital SI and initial prehospital lactatemia.

Results

We analysed 410 consecutive COVID-19 patients [254 males (62%); mean age, 64 ± 18 years].

Fifty-seven patients (14%) deceased on the scene, of whom 41 (72%) were male and were significantly older (71 ± 12 years vs. 64 ± 19 years; P 〈10−3).

Fifty-three patients (15%) were admitted in ICU and 39 patients (11%) were deceased on day-30.

The mean prehospital SI value was 1.5 ± 0.4 and the mean prehospital lactatemia was 2.0 ± 1.7 mmol.l−1.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis on matched population after IPTW propensity analysis reported a significant association between ICU admission and age (adjusted Odd-Ratio (aOR), 0.90; 95% confidence interval (95%CI): 0.93–0.98;p = 10−3), SpO2i.O2 (aOR, 1.10; 95%CI: 1.02–1.20;p = 0.002) and BMI (aOR, 1.09; 95% CI: 1.03–1.16;p = 0.02). 30-day mortality was significantly associated with SpO2i.O2 (aOR, 0.92; 95% CI: 0.87–0.98;p = 0.01 P < 10−3) and GCSi (aOR, 0.90; 95% CI: 0.82–0.99;p = 0.04).

Neither prehospital SI nor prehospital lactatemia were associated with ICU admission and 30-day mortality.

Conclusion

Neither prehospital initial SI nor lactatemia were associated with ICU admission and 30-day mortality among COVID-19 patients initially cared for by a Paris Fire Brigade BLS or ALS team. Further prospective studies are needed to confirm these preliminary results.

1. Introduction

Since March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 disease to be a worldwide pandemic (1). Although the overall mortality rate is low ([2], [3], [4], [5]), to date, COVID-19 has caused ~5 500,000 deaths worldwide, half of which are in Europe. COVID-19 is caused by infection with SARS-CoV-2 (6), and ~ 25% of patients suffer a severe form of this disease (2).

The most severe form of COVID-19 involves acute respiratory failure (ARF) due to hypoxia and hypoxemia. We previously reported that dyspnea is the main symptom requiring prehospital treatment by the Paris Fire Brigade prehospital emergency service, basic life support (BLS) and/or advanced life support (ALS) team (7). One peculiarity of respiratory SARS-CoV-2 infection is the presentation of a low respiratory rate (RR) increase despite severe hypoxemia reflected by low pulse oximetry (SpO2) of variable depth depending on the stage of the disease, along with a lack of functional signs and respiratory distress signs (6,7) named “happy hypoxia” by Dhont al. (8).

The COVID-19 pandemic poses a risk of an inadequate ratio between needs (patients with severe COVID-19 ARF requiring intensive care unit (ICU) admission) and resources (available medical ventilator devices). Thus, the development of simple tool for early severity assessment is useful to optimise the prehospital sorting between emergency departments (EDs) or ICU admission. In this objective, the shock index (SI), which is calculated as the ratio between heart rate and systolic blood pressure (9), is a simple clinical tool, and lactatemia is a simple biological tool validated (10) and available in the prehospital setting allowing early severity assessment of trauma and sepsis (11,12). These clinical and biological tools could be useful to physicians for the decision-making process using evidenced based medicine knowledge without being polluted by the spread of fake news about COVID-19 (13).

In this study, we investigated the association between a clinical (initial prehospital SI) and biological (initial prehospital lactatemia) tool and the ICU admission and 30-day mortality among COVID-19 patients cared for by a Paris Fire Brigade BLS/ALS team in the prehospital setting.

2. Methods

2.1. Design, setting, and participants

As previously described (7), the prehospital Paris Fire Brigade emergency medical system is a 2-tiered response system—comprising a BLS tier served by 200 teams of 3–5 professional rescuers deployed from 77 stations, and an ALS tier served by 44 ambulance teams, each including an emergency physician, a nurse, and a driver (14). Emergency calls are assessed by a dispatch center operator, who may decide to send a BLS and/or ALS team based on the clinical history and symptoms reported by the patient or a witness. Once rescue teams have arrived on the scene, the emergency physician examines the patient, and then the patient can either be left on the scene, admitted to the ED, or admitted directly to the ICU, depending on the level of criticality.

We performed a retrospective observational study that included patients who required intervention by a Paris Fire Brigade BLS or ALS team between 2020, March 08th and 2020, May 30th. No exclusion criteria were applied.

2.2. Ethical considerations

This retrospective study was approved by the French ethics committee Ouest III on 2020/04/08 (Ref: 20.04.30 / SI CNRIPH 20.03.30.62742).

2.3. Data collection

To minimize the bias in data abstraction (15), data collection was performed by a single investigator (EB) using a previously established standardized abstraction template. From BLS/ALS prehospital reports, we retrieved the patients' demographic characteristics (age, gender, height and weight), initial (i.e., at the first contact) prehospital vital sign values [systolic, diastolic and mean blood pressure (SBPi, DBPi, MBPi), heart rate (HRi), pulse oximetry without (SpO2i) and with oxygen supplementation (SpO2i.O2), respiratory rate (RRi), temperature, and Glasgow coma scale (GCSi)], administered prehospital treatments (oxygen modality), the means of transport used for admission to hospital and in-hospital service admission (ICU or ED).

Prehospital SI was defined by the initial, i.e., first, assessment ratio between heart rate and systolic blood pressure (SI=HR/SBP) (9,16). Prehospital blood lactatemia assessed by a validated point of care device (9) was retrieved from prehospital reports. We also recorded the date of suspected contamination, the date of first symptoms, and the date of contact. The COVID-19 diagnosis was established after transfer to hospital, and prehospital diagnosis was based on a bundle of arguments: clinical signs and recent contact with a COVID-19 patient.

2.4. Statistical analyses

Results are expressed as mean and standard deviation for quantitative parameters with a normal distribution, as median and interquartile range [Q1–Q3] for parameters with a non-gaussian distribution, and as absolute value and percentage for qualitative parameters.

To reduce the potential effect of cofounders, we performed a propensity score analysis with the Inverse Probability Treatment Weighting (IPTW) method without weight truncation. Covariates included in the IPTW propensity analysis were: age, sex, body mass index (BMI), iRR, SpO2i and SpO2i.O2, GCSi value, initial prehospital SI and initial prehospital lactatemia. Results are expressed with adjusted Odds Ratio (aOR) with 95% confidence interval (95%CI). All analyses were performed using R 4.0.4 (http://www.R-project.org; the R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

3. Results

3.1. Population characteristics

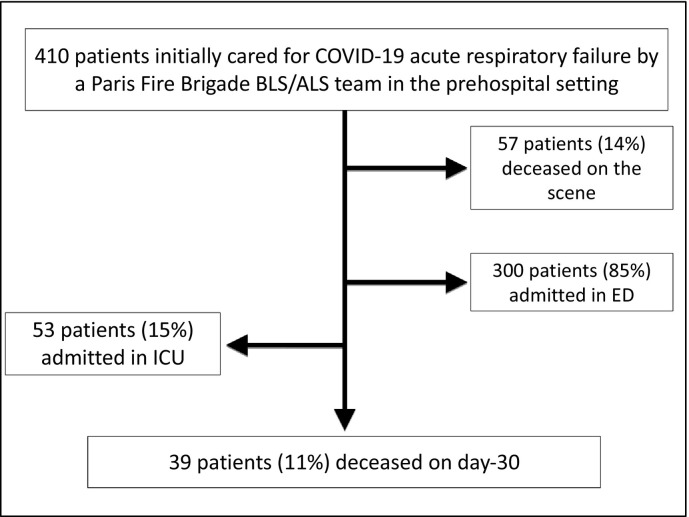

Between 2020, March 08th and 2020, May 30th, 410 consecutive patients suffering from COVID-19 were attended to by a prehospital Paris Fire Brigade ALS team. The mean age was 64 ± 18 years, and 254 patients (62%) were male. A total of 57 patients (14%) were deceased on the scene, of whom 41 (72%) were male. The deceased patients were significantly older than the alive patients (71 ± 12 years vs. 64 ± 19 years; P < 10−3). Fifty-three patients (15%) were admitted in ICU. Thirty-nine patients (11%) were deceased on day-30, e.g., after hospital admission (Fig. 1 ). Table 1 summarizes the populations' demographic and prehospital clinical characteristics.

Fig. 1.

Patient flowchart.

Table 1.

Populations' demographic and prehospital clinical characteristics

| Overall population (n = 410) |

In-ICU admission (n = 53) |

30-day mortality (n = 39) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 64 ± 18 | 60 ± 14 | 71 ± 12 |

| Male gender | 254 (62%) | 38 (72%) | 29 (74%) |

| BMI (kg.m−2) | 31 ± 7 | 33 ± 7 | 31 ± 4 |

| SBPi (mmHg) | 129 ± 25 | 129 ± 26 | 119 ± 27 |

| DBPi (mmHg) | 75 ± 16 | 73 ± 17 | 69 ± 15 |

| MBPi (mmHg) | 93 ± 17 | 91 ± 18 | 85 ± 17 |

| HRi (beats.min−1) | 92 ± 21 | 99 ± 21 | 87 ± 23 |

| SI | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 1.4 ± 0.5 |

| Lactatemia (mmol.l−1) | 2.0 ± 1.7 | 2.1 ± 1.7 | 2.2 ± 2.0 |

| RRi (movements.min−1) | 26 [20−31] | 30 [26–32] | 30 [24–38] |

| SpO2i (%) | 93 [84–97] | 85 [80–92] | 77 [73–83] |

| SPO2i.O2 (%) | 95 [91–97] | 96 [93–98] | 90 [85–95] |

| Temperature (°C) | 37.2 [36.6–38.0] | 36.8 [36–38.1] | 14 [3–15] |

| Glasgow coma scale | 15 [14–15] | 15 [15–15] | 14 [3–15] |

| ALS hospital transport | 167 (41%) | 53 (100%) | 29 (74%) |

| Chest intubation | 21 (5%) | 21 (100%) | 9 (23%) |

| ICU admission | 53 (15%) | – | 14 (36%) |

| ED admission | 300 (85%) | – | 25 (64%) |

| 30-day-mortality | 39 (11%) | 14 (26%) | – |

SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, MBP mean blood pressure, HR heart rate, RR respiratory rate, SI Shock Index (HRi/SBPi), GCS Glasgow coma scale, ICU intensive care unit, ED emergency department, BMI body mass index. Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation for quantitative parameters with normal distribution, as median [interquartile range] for quantitative parameters with non-gaussian distribution, and as absolute value (percentage) for qualitative parameters.

P values correspond to the univariate odds ratio between prehospital intubation and no prehospital intubation patients, and P values of <0.05 are presented in bold.

3.2. Main measurements

In the overall population, the mean prehospital SI value was 1.5 ± 0.4 and the mean prehospital lactatemia was 2.0 ± 1.7 mmol.l−1.

3.2.1. ICU admission

Multivariate logistic regression analysis on matched population after IPTW propensity analysis reported a significant association with: age (aOR, 0.90; 95%CI: 0.93–0.98;p = 10−3), SpO2i.O2 (aOR, 1.10; 95%CI: 1.02–1.20;p = 0.002) and BMI (aOR, 1.09; 95% CI: 1.03–1.16;p = 0.02) but not with prehospital SI (aOR, 4.30; 95% CI: 0.79–23.90;p = 0.089) and/or prehospital lactatemia (aOR, 1.14; 95% CI: 0.89–1.43;p = 0.29).

3.2.2. 30-day mortality

Multivariate logistic regression analysis on matched population after IPTW propensity analysis reported a significant association with: SpO2i.O2 (aOR, 0.92; 95%CI: 0.87–0.98;p = 0.01 P < 10−3) and GCSi (aOR, 0.90; 95% CI: 0.82–0.99;p = 0.04) but not with prehospital SI (aOR, 0.65; 95%CI: 0.11–3.52;p = 0.626) and/or prehospital lactatemia (aOR, 0.87; 95% CI: 0.68–1.08;p = 0.246).

4. Discussion

In this retrospective analysis of 410 COVID-19 patients cared for by a prehospital Paris Fire Brigade BLS/ALS team, we observed that neither prehospital initial shock index nor prehospital lactatemia are associated with ICU admission and 30-day mortality among COVID-19 patients.

Early medical assessment of patients with COVID-19 is crucial in the triage decision-making process for the optimal orientation between the ICU and the ED. Apart from diagnosis, the real challenge for the prehospital emergency service is to quickly assess sepsis severity in order to orient the patients in the pre-hospital setting to the appropriate facility (ED or ICU). The objective is to avoid both under-triage and over-triage (17,18).

With sepsis, since 2016, the “sepsis 3” conference and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ruled that early severity assessment is a priority to improve the survival rate (19). Briefly, patients without severity criteria are referred to a hospital ward, whereas sicker patients or those at risk of deterioration required ICU level of care.

SI is a simple clinical tool aiming to assess the degree of hypovolemia used for hemorrhagic and infectious shock (16) with a threshold ≥1.0 associated with poorer outcome in case of acute circulatory failure (20).

In order to facilitate appropriate triage severity assessment, because of the lack of clinical signs specifity, scores were developed to improve screening performances. For example, SOFA (21) and qSOFA (22) scores are recognized scores for sepsis. Contrary to sepsis severity evaluation based on medical history and clinical signs ([22], [23], [24]), the clinical evaluation of severity in patients with COVID-19 is more difficult because of the “happy hypoxia” clinical presentation (8).

For sepsis diagnosis and severity assessment, biomarkers, especially lactatemia, improve sensitivity and specificity. In this study, we report that lactatemia is not useful for COVID-19 severity assessment because of low association with ICU admission requirement and mortality.

This study presents some limitations that should be considered. The study was conducted in France where the prehospital system allows early triage in the prehospital setting. Because the French EMS delivery model is very different that many U.S. systems, our results are not directly transposable to another country with a different EMS delivery model even if prehospital SI calculation and lactic acid assessment don't require a physician presence. The results cannot be transferred to paediatric patients because they were obtained from adult patients. Because our study was completed relatively early in the pandemic, we cannot assume that our results are time consistent because of different SARS CoV-2 variants and inpatient treatment improvement. Our study population consisted of suspected COVID-positive based on clinical signs and symptoms and patient contacts, not a PCR (polymerase chain reaction) COVID test result. The PCR test was necessary to confirm that COVID-19 was partly involved in the patient's death. From a methodological point of view, this study is retrospective and is unable to conclude with precision the link between mortality subsequent to COVID-19 and prehospital SI and lactatemia. Moreover, SI increase may be decreased by beta-blocker therapy.

5. Conclusion

Prehospital initial SI and prehospital lactatemia are not associated with ICU admission and 30-day mortality among COVID-19 patients initially cared for by a Paris Fire Brigade BLS or ALS team. These preliminary data suggest that SI and lactatemia are not useful to identify ARF COVID-19 patients. However, further prospective studies are needed to confirm these preliminary results.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This retrospective analysis was approved by the French ethics committee Ouest III on 2020/04/08 (Ref: 20.04.30 / SI CNRIPH 20.03.30.62742).

Consent for publication

The ethical committee considered that consent of patients was waived for participation in this retrospective observational study.

Availability of data and material

yes, on reasonable request.

Funding

None.

Authors' contributions

RJ, EB, YD, KB, MS, AA, FL, DJ, BP and ST collected data.

RJ and DJ analysed data.

RJ drafted the manuscript.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors' information

Romain Jouffroy, Elise Brami, Yann Daniel, Kilian Bertho, Marine Scannavino, Amandine Abriat, Frederic Lemoine, Daniel Jost, Bertrand Prunet, Stéphane Travers - Paris Fire Brigade, Emergency Medicine dpt, 1 place Jules Renard, 75017 Paris – France.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Romain Jouffroy: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Elise Brami: Data curation. Marine Scannavino: Data curation. Yann Daniel: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. Kilian Bertho: Data curation. Amandine Abriat: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. Marina Salomé: Project administration, Methodology. Sabine Lemoine: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Daniel Jost: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Project administration, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Bertrand Prunet: Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Conceptualization. Stéphane Travers: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the Paris Fire Brigade Basic and Advanced Life Support Teams for their daily engagement during the pandemic.

References

- 1.World Health Organization WHO director-general's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19. 2020. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 11 March.

- 2.Onder G., Rezza G., Brusaferro S. Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(18):1775–1776. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rajgor D.D., Lee M.H., Archuleta S., Bagdasarian N., Quek S.C. The many estimates of the COVID-19 case fatality rate. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(7):776–777. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30244-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verity R., Okell L.C., Dorigatti I., Winskill P., Whittaker C., Imai N., et al. Estimates of the severity of coronavirus disease 2019: a model-based analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(6):669–677. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30243-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu Z., McGoogan J.M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rothan H.A., Byrareddy S.N. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. J Autoimmun. 2020;109 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jouffroy R., Jost D., Prunet B. Prehospital pulse oximetry: a red flag for early detection of silent hypoxemia in COVID-19 patients. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):313. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03036-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dhont S., Derom E., Van Braeckel E., Depuydt P., Lambrecht B.N. The pathophysiology of ‘happy’ hypoxemia in COVID-19. Respir Res. 2020;21(1):198. doi: 10.1186/s12931-020-01462-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berger T., Green J., Horeczko T., Hagar Y., Garg N., Suarez A., et al. Shock index and early recognition of sepsis in the emergency department: pilot study. West J Emerg Med. 2013;14(2):168–174. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2012.8.11546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leguillier T., Jouffroy R., Boisson M., Boussaroque A., Chenevier-Gobeaux C., Chaabouni T., et al. Lactate POCT in mobile intensive care units for septic patients? A comparison of capillary blood method versus venous blood and plasma-based reference methods. Clin Biochem. 2018;55:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2018.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Regnier M.A., Raux M., Le Manach Y., Asencio Y., Gaillard J., Devilliers C., et al. Prognostic significance of blood lactate and lactate clearance in trauma patients. Anesthesiology. 2012;117(6):1276–1288. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318273349d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jouffroy R., Leguillier T., Gilbert B., Tourtier J.P., Bloch-Laine E., Ecollan P., et al. Pre-hospital lactatemia predicts 30-day mortality in patients with septic shock-preliminary results from the LAPHSUS study. J Clin Med. 2020;9(10) doi: 10.3390/jcm9103290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orso D., Federici N., Copetti R., Vetrugno L., Bove T. Infodemic and the spread of fake news in the COVID-19-era. Eur J Emerg Med. 2020;27(5):327–328. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adnet F., Lapostolle F. International EMS systems: France. Resuscitation. 2004;63(1):7–9. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gearing R.E., Mian I.A., Barber J., Ickowicz A. A methodology for conducting retrospective chart review research in child and adolescent psychiatry. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;15(3):126–134. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allgower M., Burri C. Shock index. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1967;92(43):1947–1950. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1106070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohr N.M., Wu C., Ward M.J., McNaughton C.D., Richardson K., Kaboli P.J. Potentially avoidable inter-facility transfer from veterans health administration emergency departments: a cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):110. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-4956-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoder A., Bradburn E.H., Morgan M.E., Vernon T.M., Bresz K.E., Gross B.W., et al. An analysis of overtriage and undertriage by advanced life support transport in a mature trauma system. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020;88(5):704–709. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singer M., Deutschman C.S., Seymour C.W., Shankar-Hari M., Annane D., Bauer M., et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315(8):801–810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rady M.Y., Nightingale P., Little R.A., Edwards J.D. Shock index: a re-evaluation in acute circulatory failure. Resuscitation. 1992;23(3):227–234. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(92)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vincent J.L., Moreno R., Takala J., Willatts S., De Mendonca A., Bruining H., et al. The SOFA (Sepsis-related organ failure assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the working group on Sepsis-related problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22(7):707–710. doi: 10.1007/BF01709751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ait-Oufella H., Bige N., Boelle P.Y., Pichereau C., Alves M., Bertinchamp R., et al. Capillary refill time exploration during septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40(7):958–964. doi: 10.1007/s00134-014-3326-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ait-Oufella H., Lemoinne S., Boelle P.Y., Galbois A., Baudel J.L., Lemant J., et al. Mottling score predicts survival in septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37(5):801–807. doi: 10.1007/s00134-011-2163-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jouffroy R., Saade A., Tourtier J.P., Gueye P., Bloch-Laine E., Ecollan P., et al. Skin mottling score and capillary refill time to assess mortality of septic shock since pre-hospital setting. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37(4):664–671. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2018.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

yes, on reasonable request.