Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this integrative review is to examine the literature on vaccine hesitancy among American healthcare workers during the COVID-19 vaccine rollout.

Methods

A review of quantitative literature on acceptance, intention, refusal, or hesitation to accept the COVID-19 vaccine was conducted, searching in PubMed, Cumulative Index for Nursing and Allied Health Literature, PsycINFO, and Web of Science. Because of the immediacy of the topic, research letters were included in addition to articles. The 18 publications were appraised for quality using the Critical Appraisal Checklist for Cross-Sectional Studies by the Center for Evidence-Based Management.

Results

Estimates of vaccine hesitancy among healthcare workers were similar to the general population. The literature indicates demographic characteristics associated with vaccine hesitancy, including being younger, female, Black, Hispanic, or Latinx. However, examination of the demographic data also points to gaps in the understanding and implications of those characteristics. The newness or perceived rush of vaccine development and implementation were the most cited sources for hesitancy.

Conclusion

The studies in this review give clear areas of need for translational research on dissemination and implementation relating to the correlational data, including in areas of comorbid, diasporic, and reproductive health concerns. However, with the gravity of the pandemic and quick arrival of the COVID-19 vaccine happening in the midst of an infodemic, adjunctive interventions could be warranted to combat hesitancy.

Keywords: COVID-19, Vaccine hesitancy, Vaccine acceptance, Healthcare workers

Introduction

For over 2 years, healthcare workers (HCWs) around the globe have been providing care and services during the COVID-19 pandemic, putting themselves at an increased risk for contracting the potentially deadly disease.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 In the same month that the battle against COVID-19 began, the US Department of Health and Human Services issued a statement about accelerating the development and production of vaccines under Operation Warp Speed (OWS).6 OWS had the distinct goal of speed without sacrificing safety. Development was synergized by large funding streams, previous middle east respiratory syndrome (MERS), severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and RNA vaccine research, the ability of researchers to run multiple trials, and advances in manufacturing.7 The goal of OWS was subsequently attained within the first year of the pandemic by two vaccines granted emergency use authorization (EUA) by the Food and Drug Administration on December 11, 2020.8, 9, 10, 11

Eight days before the EUAs, the centers for disease control and prevention (CDC's) Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended that HCWs be among the first Americans offered vaccination under the EUAs, citing “early protection of healthcare personnel is critical.”12 Approximately 17.5 million Americans belong to this category13 and have become subject to vaccination mandates.

General population hesitancy regarding the COVID-19 vaccine has been correlated with being female, Black, and younger. Additional correlates could include lower educational attainment, rural or geographic residence, prior vaccination hesitancy, and lower perceived risk of COVID-19.14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 Furthermore, a perceived rush over vaccine development and approval, as well as concerns over safety and efficacy has plagued public health campaigns.14 , 16 , 18 , 19 Saliently, the spread of mis- and dis-information, culminating in an infodemic, has underscored the COVID-19 pandemic and vaccine development.20 , 21 America has seen a relatively large distribution of misleading or false information surrounds the pandemic and vaccine rollout, and more than one-third of mis- or dis-information regarding the COVID-19 vaccine was related to vaccine development during the year of the rollout.22 , 23 The unprecedented nature of the virus and subsequent vaccine development, as well as the nature of the infodemic in which it has been unfolding, differentiates COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy from vaccine hesitancy around long-standing vaccines. Yet, despite the differences in context, vaccines remain the most effective way to curb the spread of infectious disease. With so many Americans employed in the healthcare sector, implications for COVID-19 spread among HCWs, their patients, and communities at large are substantial. Thus, the purpose of this integrative review is to synthesize and examine the quantitative literature specific to HCWs’ hesitancy surrounding the rollout of the COVID-19 vaccine.

Methods

This review was guided by Whittemore and Knafl (2005) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.24 , 25 Critical appraisal was conducted with the Critical Appraisal Checklist for Cross-Sectional Studies26 (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Center for evidence-based management: critical appraisal checklist for cross-sectional study.

| Appraisal questions | 1. Did the study address a clearly focused question/issue? | 2. Is the research method (study design) appropriate for answering the research question? | 3. Is the method of selection of the subjects (employees, teams, divisions, organizations) clearly described? | 4. Could the way the sample was obtained introduce (selection) bias? | 5. Was the sample of subjects representative with regard to the population to which the findings will be referred? | 6. Was the sample size based on pre-study considerations of statistical power? | 7. Was a satisfactory response rate achieved? | 8. Are the measurements (questionnaires) likely to be valid and reliable? | 9. Was the statistical significance assessed? | 10. Are confidence intervals given for the main results? | 11. Could there be confounding factors that haven't been accounted for? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abohelwa27 | Yes | Can't Tell | Can't Tell | Yes | Can't Tell | No | 0.27 | Can't Tell | No | No | Yes |

| Ciardi28 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Can't Tell | No | 0.1 | Yes | Yes | Yes (for some) | Yes |

| Famuyiro29 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Can't Tell | No | 0.82 | Yes | Yes | Yes (for some) | Yes |

| Fotenot30 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can't Tell | Yes | No | 0.21 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Halbrook31 | Yes | Yes | Can't Tell | Can't Tell | Can't Tell | No | NR | Can't Tell | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Kuter32 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can't Tell | Can't Tell | No | 0.345 | Can't Tell | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Pacella33 | Yes | Yes | Can't Tell | Yes | Can't Tell | No | NR | Can't Tell | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Parente34 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can't Tell | Yes | No | 0.18 | Can't Tell | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Shaw35 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can't Tell | No | 0.55 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Shekhar36 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can't Tell | No | NR | Can't Tell | Yes | No | Yes |

| Unroe37 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can't Tell | Yes | No | 0.33 | Can't Tell | Yes | Yes (for some) | Yes |

| Letters | |||||||||||

| Fossen38 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | – | – | – | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Gadoth39 | Yes | Yes | Can't Tell | Yes | Can't Tell | No | 0.57 | Can't Tell | No | Yes | Yes |

| Grumbach40 | Yes | Yes | Can't Tell | Can't Tell | Yes | No | NR | Can't Tell | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Kociolek41 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can't Tell | No | 0.63 | Can't Tell | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Meyer42 | Yes | Yes | Can't Tell | Can't Tell | Yes | No | 0.685 | Can't Tell | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Pamplona43 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | – | – | – | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Schrading44 | Yes | Yes | Can't Tell | Yes | Can't Tell | No | NR | Can't Tell | No | No | Yes |

Note. NR = not reported.

The literature search was conducted in July 2021 using the Cumulative Index for Nursing and Allied Health Literature via EBSCO, Medline via PubMed, Web of Science, and PsycINFO. Databases were searched for “COVID-19 vaccine,” and alternate terms of “Coronavirus” and “Sars-CoV-2,” paired with keywords such as “acceptance,” “intention,” “hesitancy,” “attitude,” “uptake,” “confidence,” and “refusal.” Relevant search terms for the population of interest, “healthcare workers,” included “health personnel,” “healthcare provider,” “health professional,” and “nurse.” Truncation was used when possible.

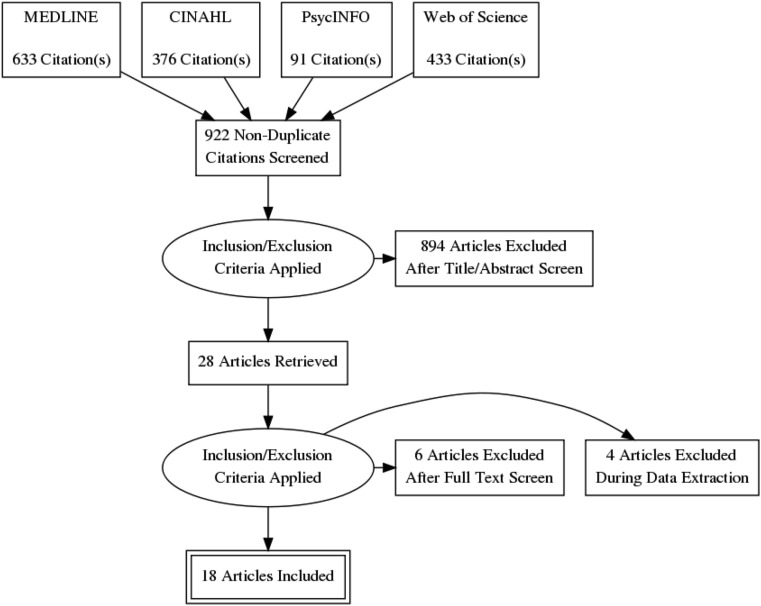

Inclusion criteria were left purposely broad to include all types of HCWs and facilities. Data collection conducted on American HCWs in or after 2020 was the primary inclusion criteria based on the United States’ unique social and healthcare landscape. The American pandemic response, which included OWS and timely access to vaccines, focused on HCWs as a primary class of vaccine recipients. Letters were included based on the immediacy of the topic, offering comprehensive coverage as data was emergent. A total of 1533 records were obtained. After duplicate removal, 922 citations were screened, 28 went to full-text review, and 18 are included in this review (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram of article selection.

Results

Of the 18 studies, 11 were peer-reviewed articles27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37 and seven were research letters.38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44 All 18 published data from cross-sectional surveys collected over short periods on participants gained from non-probability sampling frames. All studies gave a snapshot of vaccination acceptance or intention and refusal or hesitancy among their sample. Correlational trends were most often given as odds ratios. Most asked additional questions, but less than half the publications reported using trialed or validated questionnaires. Surveys included reasons for hesitancy and safety or efficacy perceptions.

The largest sample size was 16,292 participants,42 the smallest 81,27 and the median 1600.40 , 44 The shortest study was 3 days in length,37 with most completed in 2 weeks to a month. An exception was Halbrook et al.,31 with data collected at three time points from September 2020 to February 2021. Of the studies reporting response rates, the lowest was 10%,28 and the highest was 82%.29 The oldest data collection was done in August 2020,34 and seven collected data in December of 2021, the month of the EAUs29, 30, 31, 32 , 35 , 40 , 42 (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Publication summaries.

| Author/Pub Info | Aims | Sample - Setting, Time of data collection, and considerations | Results | Vaccine hesitancy or attitudes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abohelwa, M. et al.27 Primary authors discipline: Medicine Article |

To understand residents and fellows’ attitudes toward vaccination and record any side-effects after vaccination | 81 residents and fellows South March 2021 |

77 (95.1%) accepted 3 (3.7%) refused Other findings: All 77 vaccinated reported pain at the injection site and headache in 49.4% |

78 (96.3%) of the sample reported that they supported vaccination |

| Ciardi, F. et al.28 Primary authors discipline: Medicine Article |

This study was conducted about attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination among healthcare workers at a public hospital in New York City during the beginning of COVID-19 vaccination | 428 hospital workers∗ ∗physicians (28.5%), nurses (21.96%) Northeast December 2020 to January 2021 |

274 (64%) accepted 38 (8.9%) intended 116 (27%) refused Statistically significant correlations Gender: Males < hesitant Age: Older (65+) < hesitant Race: Asian least hesitant, Black most hesitant Ethnicity: Hispanic > hesitancy Other significant associations: Role within hospital, use of PPE, and perceived personal risk |

The most predictive factors were prior vaccine attitudes and concern with the speed of testing and approval of the vaccines |

| Famuyiro, T. B. et al.29 Primary authors discipline: Medicine Article |

To assess the readiness for vaccine uptake among HCWs at three community-based, university-affiliated health centers | 205 community-based workers∗ ∗physicians (40.5%), other clinical staff (44.4%) South December 2020 |

110 (54%) immediate intention 56 (27%) waiting 36 (18%) had no intention Statistically significant correlations: Gender: Males < hesitant Age: Older (65+) < hesitant Race: Asian least hesitant Black > hesitant than White Ethnicity: Hispanic > hesitant than White Other significant associations: moderate-risk perception < hesitance than those with low-risk perception |

Most physicians (83%) and residents (81%) expressed more enthusiasm to receive the vaccine once it became available compared with other clinical staff (nurses, medical assistant, clinical technician, etc.; 31%) |

| Fontenot, H.B. et al.30 Primary authors discipline: Nursing Article |

To assess the intentions of licensed nurses in the State of Hawaii to obtain a COVID-19 vaccine and identify factors that are associated with nurses’ intention to vaccinate | 423 nurses West December 2020 |

221 (52%) intended 118 (27.9%) waiting 84 (19.9%) had no intention Statistically significant correlations: Age: Older (50+) < hesitant |

The strongest predictors of any level of intention were greater positive attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination and lower concerns related to COVID-19 vaccine safety |

| Fossen, M. C. et al.38 Primary authors discipline: Nursing Letter |

Examined vaccination rates of hospital workers by age, gender, department, and race to determine in which groups vaccine hesitancy was highest | 3401 hospital workers South March 2021 |

2245 (71%) accepted 976 (29%) refused Statistically significant correlations: Age: Older (50+) < hesitant Race: Black > hesitancy than White Other significant associations: Working in a clinical department < hesitancy |

|

| Gadoth, A. et al.39 Primary authors discipline: Public Health Letter |

To understand general vaccine acceptance and specific attitudes toward forthcoming coronavirus vaccines among HCWs in Los Angeles, California | 540 healthcare workers∗ ∗prescribing clinicians 37.2%, registered nurses 38.3% West September to October 2020 |

179 (33%) immediate intention 354 (65.6%) waiting 7 (1.3%) had no intention Correlations (p values unknown): Age: Older (51+) < hesitant Race: Asian > hesitant than White Ethnicity: Hispanic > hesitant Other findings: Prescribing clinicians exhibited 20–30% less hesitant than other HCWs |

46.9% of questioned the efficacy of vaccine Fast-tracking regulatory procedures and a lack of transparency were primary rationales for refusal or delay |

| Grumbach, K. et al.40 Primary authors discipline: Medicine Letter |

Investigated COVID-19 vaccine intentions among racially and ethnically diverse samples of HCW and the general population | 1803 healthcare workers∗ ∗physicians, APPs and registered nurses (76.7%) West November 2020 to January 2021 |

1507 (83.6%) intended Statistically significant correlations: Race: White was least hesitant Asian > hesitant Black > hesitant (most hesitant) Multiple/other > hesitant Ethnicity: Hispanic > hesitant |

Black, Latinx, and Asian respondents reported less confidence in vaccine efficacy, less trust in companies making the vaccine, and more worry that government rushed the approval process |

| Halbrook, M. et al.31 Primary authors discipline: Public Health Article |

The primary outcome of interest was COVID-19 vaccination intent and vaccine uptake among HCW | 858 healthcare workers∗ ∗Advanced degree (59.8%) West September 2020 to February 2021 |

281 (32.8%) intended at survey 1 566 (68.8%) intended/accepted at survey 2 823 (96%) accepted at survey 3 Statistically significant correlations: Age: Older (50+) < hesitant Race∗: Black > hesitancy than White Asian > hesitant than Black and White ∗This relationship is seen with intention but not uptake Other significant associations: Educational attainment was associated with intention and uptake |

Among HCWs refusing the vaccine reasons included not having enough information or belief that the vaccine could infect them with COVID-19 |

| Kociolek, L. et al.41 Primary author's discipline: Medicine Letter |

Assessing frequency of vaccine hesitancy, characteristics of those reporting vaccine hesitancy, specific concerns, and communication preferences among hospital workers | 4448 hospital workers Midwest December 2020–January 2021 |

368 (8.6%) accepted 2559 (59.8%) intended 810 (18.9%) hesitant Statistically significant correlations: Gender: Males < hesitant Race: Black > hesitant than non-Black Ethnicity: Hispanic > hesitant Other significant associations: Hesitancy was associated with less concern about personal risk of severe COVID-19 and (three times) more prevalent in those with high-risk medical conditions. |

Concerns reported were vaccine safety related to novelty and speed of the clinical development process |

| Kuter, B. J. et al.32 Primary author's discipline: Public Health Article |

To understand attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines… to obtain a better understanding of how hospital employees, both in clinical and non-clinical positions, perceive the new COVID-19 vaccines and their intention to be vaccinated | 12,034 hospital workers Northeast November to December 2020 |

7492 (63.7%) intended 4368 (36.3%) hesitant Statistically significant correlations: Gender: Males < hesitant Age: Older (65+) < hesitant Race: Black > hesitant than White Asian < hesitant Ethnicity: Hispanic > hesitant Other significant associations: Less hesitancy in those with up-to-date vaccinations, good-excellent self-reported health and no direct patient contact |

Over 80% of vaccine hesitant reported concerns over side-effects and vaccines’ newness 78% of hesitant reported not knowing enough of about the vaccine 33% questioned efficacy and 25% were concerned about getting COVID-19 from the vaccine |

| Meyer, M. N. et al.42 Primary author's discipline: Bioethics Letter |

To assess their intentions to [receive a COVID-19 vaccination], and understand reasons for hesitancy among HCW | 16,292 healthcare workers Northeast December 2020 |

9015 (55.3%) intended 7277 (44.6%) hesitant Significant associations: Patient-facing employees were less hesitant than those who do not interact with patients |

90.3% of vaccine hesitant reported concerns about unknown risks of the vaccines, 44.3% reported they wanted to wait until others’ vaccine experiences are known, and 21.1% reported that they do not trust the rushed FDA process. |

| Pacella-LaBarbara, M. et al.33 Primary author's discipline: Health psychology Article |

To determine vaccine intent/uptake, perceived COVID-19 vulnerability, and factors associated with vaccine intent/uptake. | 475 emergency department and EMS workers Mid-Atlantic January 2021 |

337 (79%) accepted or intended 98 (21%) had no intention Statistically significant correlations: Gender: Males < hesitant Other significant associations: Those with a history of COVID-19 infection had lower intention Those with an advanced degree had higher intention/uptake (zero physicians reported no intention) |

Those with a higher perceived COVID-19 vulnerability had higher rates of intention or uptake |

| Pamplona, G. M. et al.43 Primary author's discipline: Unknown Letter |

To report dialysis staff vaccination acceptance and hesitancy rates from four Renal Research Institute dialysis clinics and a home dialysis program located in New York, New York. | 157 community-based healthcare workers Northeast January 2021 |

115 (73.2%) accepted 6 (3.8%) hesitant 36 (23%) waiting/unknown intent Other findings: Reasons for delay included: recent COVID-19 infection, leave of absence from work, and pregnancy or breastfeeding |

|

| Parente, D. J. et al.34 Primary author's discipline: Medicine Article |

To evaluate HCW willingness to become vaccinated against COVID-19 and identified barriers/facilitators to vaccine uptake among all personnel at a large academic medical center in the Midwest | 3347 healthcare workers Midwest August 2020 |

1241 (37%) intended 1764 (52%) waiting 331 (10%) had no intention Statistically significant correlations: Gender: Males < hesitant Race: Black > hesitant than White Other significant associations: Prior influenza vaccination, increased concern about COVID-19, and postgraduate education were associated with vaccine acceptance |

Barriers to vaccination included concerns about long-term side-effects (57.1%), safety (n = 55.0%), efficacy (37.1%), and risk-to-benefit ratio (31.0%) |

| Schrading, W. A. et al.44 Primary author's discipline: Medicine Letter |

To describe differences in vaccination rates among various types of ED HCP at US academic medical centers and reasons for declining vaccination | 1321 Emergency Department hospital workers∗ ∗physicians/APP 49.4%, registered nurses 25.75% Multiple US regions January 2021 |

Results: 1136 (86%) received vaccine Correlations (p value unknown): Non-Hispanic Black HCWs had the lowest vaccine acceptance rate Other findings: Physicians and APPs had the lowest refusal rate (5.5% of 674), compared with nurses (22.3% of 345) and non-clinical HCWs (23.5% of 302) Vaccinated recipients planned to use the same amount of PPE at work as well as in public |

The primary reason for declining a COVID-19 vaccine was concern about vaccine safety (45.4%) |

| Shaw, J. et al.35 Primary author's discipline: Medicine Letter |

To provide a snapshot of vaccination attitudes in order to identify areas of concern that would impinge on COVID-19 vaccination program planning and implementation | 5287 hospital workers North East November to December 2020 |

3032 (57.5%) intended 2245 (42.5%) hesitant Statistically significant correlations: Gender: Males < hesitant Age: Older (65+) < hesitant Race: Asian least hesitant Black > hesitant than White Other significant associations: 80.4% of physicians and scientists intended to get vaccinated, compared with 51.4% of allied health professionals and 41.2% of nurses More non–care providers indicated they would take the vaccine if offered |

Vaccine safety, potential adverse events, efficacy, and speed of vaccine development dominated concerns listed by participants |

| Shekhar, R. et al.36 Primary author's discipline: Medicine Article |

To assess the attitude of HCWs toward COVID-19 vaccination | 3479 healthcare workers ∗professional or graduate degree 32.5%, Multiple regions October–November 2020 |

1247 (36%) intended 1953 (56%) waiting 279 (8%) had no intention Statistically Significant Correlations Gender: Males < hesitant Age: Older (60+) < hesitant Race: Asian least hesitant Black > hesitant than White Ethnicity: Hispanic > hesitant Other significant associations: HCWs working in rural areas had more hesitancy Direct medical care providers, those with professional or doctoral degrees and those with prior flu vaccination had higher intention |

Safety (69%), effectiveness (69%), and speed of development/approval (74%) were noted as the most common concerns regarding COVID-19 vaccination in our survey |

| Unroe, K. T. et al.37 Primary author's discipline: Medicine Article |

To plan for coronavirus infectious disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine distribution, the Indiana Department of Health surveyed nursing home and assisted living facility staff. | 8243 long-term care staff Midwest November 2020 |

3704 (45%) intended 2001 (24%) waiting 2523 (31%) had no intention Statistically significant correlations: Gender: Males < hesitant Age: Older (60+) < hesitant Race: Black > hesitant Other significant associations: Clinical care staff, including nurse aides and nurses in clinical roles, were less likely than dietary, housekeeping, and administrative staff to report willingness to receive the vaccine Nurses providing direct clinical care were −5 percentage points less likely to indicate a willingness to take the vaccine than nurse aides or similar role |

Concerns about side-effects was the primary reason for vaccine hesitancy (70%) other non-mutually exclusive reasons given were health concerns (34%), questioning the effectiveness (20%), and religious reasons (12%). In addition, 23% of respondents provided other reasons they would be unwilling to receive the vaccine such as concerns it is “too new,” a lack of trust, the need for more research, or it was too political |

FDA, Food and Drug Administration; HCW, healthcare workers.

The publications included a total sample population of 62,728 HCWs. Two articles focused on specific occupational roles of medical doctors27 or nurses.30 Apart from those exceptions, occupational totals were reported too diversely to synthesize effectively. One study was conducted in long-term care facility,37 and two studies were conducted in community-based care settings.29 , 43 The remaining 16 were conducted entirely in, or included, hospital settings. Eleven studies were multisite,29, 30, 31 , 33 , 34 , 36, 37, 38, 39, 40 , 44 with three being multistate.33 , 36 , 44 More than half of the study populations came from the Northeast; however, all regions of the United States were represented.

Sample demographics

Of the studies that reported on gender (N = 46,279), 75.8% of those sampled were female. Three studies27 , 42 , 43 do not include any information on race (N = 16,530; 81, 16,292, and 157, respectively). For the total sample that reported race (N = 46,198), approximately 65.2% were White, which may be further underreported because Kociolek et al.41 queried race as Black or non-Black, which excludes 3866 participants. Similarly, Pacella-LaBarbara et al.33 classify race as White and non-White; however, the sample size was significantly smaller (N = 475), and the population was identified as 95% White. Hispanic or Latinx participation was either included as a classification within race or classified as a separate category of ethnicity. Five publications30 , 31 , 33 , 35 , 38 did not report on Hispanic or Latinx participation at all (N = 10,084). Of the studies reporting ethnicity as a category within race, the overall samples were 1.8% Hispanic or Latinx.28 , 29 , 32 , 40 , 44 Of those separating out ethnicity, Hispanic or Latinx identity was reported for 25.8% of the sampled population (N = 19,886); however, approximately 41% of the sample was not reported,30 , 31 , 33, 34, 35, 36, 37 , 39 , 41 making accurate assessment impossible.

Age was reported in a variety of ways, except for the two letters in which age was not reported.42 , 43 Two articles33 , 35 reported the mean age of participants as 40 and 42.5, respectively. Most participants’ age (N = 26,357) was reported by two articles32 , 37 and two letters40 , 41 using a cutoff of 40 years. Participants were almost evenly distributed, with 51% being aged <40 years, 45.3% being >40 years, and 3.7% of data were unreported (Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Demographic variables of study participants.

| Gender | N = 46,279 |

| Female | 35,084 |

| Male | 9716 |

| Not reported | 1479 |

| Age | N = 36,693 |

| <40 | 16,883 |

| >40 | 14,695 |

| <45 | 2571 |

| >45 | 1487 |

| Not reported | 1057 |

| Race | N = 46,198 |

| White | 30,114 |

| Black | 3947 |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 758 |

| Asian | 2316 |

| Other | 3452 |

| Not reported | 5611 |

| Ethnicity | N = 19,886 |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 5134 |

| Non-Hispanic/Latinx | 6607 |

| Not reported | 8145 |

Vaccination data

Overall, 68.8% (N = 42,284) of the sample population indicated they had or would receive a COVID-19 vaccine. Almost half the studies28, 29, 30 , 33 , 34 , 36 , 37 , 39 included an option for future vaccination intention, ranging from specific timeframes (e.g. within 30 days) to simply “sometime in the future” or to “wait and see.” Acceptance or immediate intention ranged in studies from 33% to 95%, with a median of approximately 63%. Those that either reported they would or did refuse or, if given the option, were unsure they would get the vaccine, was 31.2% (N = 19,199). If separated out, 18.8% refused, and 12.4% were unsure. If separating out positive intention, 15% of those given the option reported wanting to wait for vaccination. The number of missing or not reported answers for the total sample was 1245 or approximately 2%.

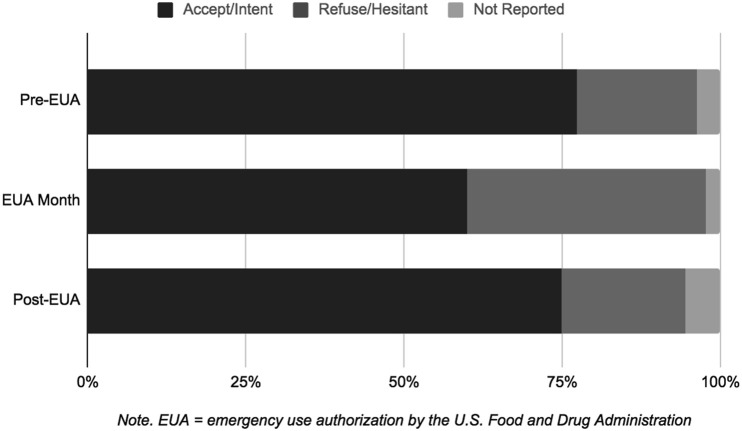

Data stratified by EUA date exhibit temporal variations in intention (Fig. 2 ). Of studies with data collection before the EAU month of December 2020 (N = 16,467), 77.3% of the sample report positive intention, 19.1% refusing, and 3.6% of the data are not reported. Of the data collected during the month of the EUA (N = 36,902), 59.9% reported positive intention, 37.7% were unsure or refusing, and 2.4% of the data were unreported. For the data collected after the EUA month, (N = 11,075) 73.6% reported vaccination, 1.2% had positive intentions for future vaccination, 15.7% refused, and 3.9% were unsure, with 5.6% of the sample was unreported. Data stratified by EUA date may indicate positive intention was at its lowest, both in the crude and adjusted ratios, during EUA passages in December.

Fig. 2.

Vaccine acceptance/intention vs refusal/hesitance by EUA.

Correlational findings

Most correlational findings associated sociodemographic characteristics, with vaccine hesitancy, namely, gender, race/ethnicity, age, and education, whereas other factors, such as safety, perceived risk, and prior vaccination, were also explored. Eleven studies compared gender with vaccine hesitancy and found that females had greater hesitancy than males,28 , 29 , 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 , 41 with two studies also referencing lower intent than non-binary counterparts.33 , 35 However, Halbrook et al.31 noted that while females had higher levels of hesitation, they actually had statistically significantly higher rates of vaccination acceptance than their male counterparts.

Thirteen studies reported on the correlations of hesitancy with race and/or ethnicity.28 , 29 , 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37 , 39, 40, 41 , 44 The majority cited more hesitancy among Black and/or Hispanic participants compared with their White counterparts. The data were split on hesitancy among Asian participants, with three studies reporting higher hesitancy31 , 39 , 40 and four reporting less hesitancy28 , 32 , 35 , 36 than their White counterparts. Ten studies examined correlations of age.28 , 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39 , 41 Two of the 10 reported no statistically significant differences,34 , 41 whereas the other eight associated younger age with more hesitancy.

Of six articles that explored education, 531, 32, 33, 34 , 36 affirmed that lower educational status correlated with higher hesitancy. Studies reporting on occupations of physicians, or advanced practice providers, correlated the roles with lower rates of hesitation or refusal.28 , 29 , 35 , 39 , 44 Notably, in the study of 8243 long-term care staff, nurses were found to be more hesitant than nursing aides by 5 percentage points, and Ciardi et al.28 found nurses and patient care associates to have the most hesitancy by profession.

Perceived risk was discussed in two ways: perceived occupational risk (exposure to infected patients) and perceived personal risk of infection (including comorbidities, self-reported health status, or concern over COVID-19 severity). Nine articles reported on perceived risk in some sense; however, the results were mixed.28, 29, 30 , 32, 33, 34, 35, 36 , 41 Three articles, comprising 20,800 participants, almost all from the Northeast (83%), reported that providing patient care correlated with higher hesitancy.32 , 35 , 36 Two articles of small sample size, varied location, and setting type reported perceived lower risk was statistically significantly associated with more hesitancy.29 , 33 Parente et al.34 found no statistically significant difference between vaccine acceptance and providing patient care or self-reported health in their study of 3347 workers, whereas Kocioleck et al.41 reported low levels of perceived risk, as well as having self-reported high-risk medical conditions were correlated with more hesitancy in their midwestern sample (N = 4277). Similarly, Kuter et al.32 found that self-reported poor/fair health status correlated with higher hesitancy (N = 12,034).

Twelve articles reported on safety concerns over vaccination within their samples.30 , 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37 , 39, 40, 41, 42 , 44 Safety concerns ranged from the rapidity of development to adverse reactions, long-term side-effects, and efficacy. Additional issues around politicization of the vaccines and/or a lack of trust in or transparency by the government or companies making the vaccines were reported by six publications.33 , 36 , 37 , 39 , 40 , 42 The most frequently cited reasons for hesitancy or refusal appeared to be the newness or perceived rush of development, and EUA, as well as the potential for side-effects.

Four articles examined prior vaccination status and concurred prior hesitancy or refusal correlated with hesitancy or refusal of COVID-19 vaccination.28 , 32 , 34 , 36 Two studies reported on geographic differences found those living in rural areas had more hesitancy.32 , 36

Discussion

The findings of this review reflected a group of timely publications regarding the COVID-19 vaccination rollout with a particularly at-risk occupational group, HCWs. Overall, we found that estimates of vaccine hesitancy among HCWs were similar to the general population. Demographic characteristics associated with vaccine hesitancy included being younger, female, Black, Hispanic, or Latinx; however, examination of the demographic data also points to gaps in the understanding and implications of those characteristics. Furthermore, the newness or perceived rush of vaccine development and implementation were the most cited sources for hesitancy.

The urgency to disseminate data on the topic is demonstrated by the number of letters included, despite their inability to provide rigorous details as articles can. As all samples were convenient, and one was a snowball, all had the potential for selection or response bias and constraints on generalizability because of their non-probability sampling structures. Over- or under-representation of responder subgroups, including by vaccination status or intentionality, may influence the robustness or magnitude of observed correlations. Overall, no study adequately addressed sample size justification, three studies included information on their reference population, and just one study tried to categorize and account for non-response bias (Table 1). Furthermore, lack of standardization is apparent in the data reporting above.

On the surface, the data presented from the 18 studies in this review echo the trends observed in the US adult population, citing higher hesitancy among those that are female, younger, Black, or Hispanic/Latinx. However, how race and ethnicity are reported and how studies manage missing data may alter the reporting of resulting correlations.45 Within the overall sample, race and ethnicity had the highest rate of undisclosed data out of the variables. The divergence of data regarding Asian participant's hesitancy may be related to more granular details regarding country of origin. Such data are necessary when Filipino nurses make up roughly 4% of the nursing workforce and share a disproportionate amount of COVID-19 cases and death, along with their Black counterparts.46 Furthermore, no research included information on foreign-born workers, who currently make up 4.1 million workers in the healthcare and social assistance industry.47

In addition, the lack of female-specific concerns as well as the role nursing could play in the vaccine discourse should also be examined. The data upheld that females have greater hesitancy; however, Halbrook et al.31 posit that they then have a higher rate of vaccination acceptance. Ciardi et al.28 posit in the discussion that intention is lower for women of any age, which questions the importance of fertility and childbearing in vaccine decision-making. Of the postvaccine rollout literature, Pamplona et al.43 and Schrading et al.44 were the only publications to report refusal based on the discrete variables of fertility, pregnancy, or breastfeeding. Given that more than 70% of the HCW population is female, more than half of childbearing age, lack of these data warrants future study.

It is noteworthy that the clinical trials of vaccines did not include pregnant or lactating women.48 However, all major reproductive health organizations recommend pregnant women receive the vaccine.49 As HCWs are majority female, these concerns must be included in the discourse, even if to rule out their influence. This may be even more salient as concerns over vaccine development and approvals were indicated as a primary reason for hesitancy, especially within the female population.

Similarly, nursing is predominantly female, the largest sector of the healthcare industry at roughly four million workers, and consistently voted the most trusted profession.50 , 51 Yet nursing is largely absent from the scholarly discourse around vaccination hesitancy. Only two publications had a nurse as lead author,30 , 38 and an additional two disclosed having a nurse as a non-primary author.37 , 41 Furthermore, nurses have higher rates of hesitancy than their medical counterparts. In March of 2021, 30% of nurses had not been vaccinated.52 Of those reporting refusals, half indicated concerns about information scarcity and vaccine development and approvals. Currently, the American Nurses Association reports approximately 11% of nurses remain hesitant and 42% are against mandates.53 As mandates are rising in prevalence, vaccination or termination laws have the potential to exacerbate staffing shortages,54 which could impact care provision and the well-being of nursing staff.

The studies in this review give clear areas of need within the discourse, including comorbid, diasporic, and reproductive health concerns. Anecdotally, worries about pregnancy persist despite vaccine recommendations from credible sources, such as the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, American College of Nurse-Midwives, and Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine49 and research to the contrary, indicating rather that infection with the COVID-19 virus poses a higher risk than vaccination.55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60 Translational research on dissemination and implementation is a priority area for those focused on worker health.3

Global populations are increasingly subject to mis- and dis-information with the use of social media and communication apps. The COVID-19 infodemic21 or ubiquity of information, including false and misleading information, can influence health behaviors, including vaccine intention.20 , 61, 62, 63 In the climate of the pan- and info-demics, America is marching toward mandates as the Supreme Court upheld the Biden administration mandate for HCWs.64 However, it is unclear if vaccination mandates will extend beyond a yearly requirement, including booster doses, how many HCWs would resign rather than be vaccinated or how many may be covered by religious or medical exemptions. The effects of mandates on HCW employment, and potentially worker shortages, may not be felt immediately.

Mandates may be seen as an efficient and socially just way to increase vaccination65 and America is not alone in pursuing them, with other countries, including Germany, France, and Italy, mandating HCW vaccination.66 , 67 Vaccination Injury Compensation Programs (VICP)are available in 16 European nations, Canada, and Australia, some regardless of COVID-19 vaccination mandates.68 Given that fear of side-effects was present in the literature as a source of hesitancy, such safeguards are justified and necessary. Currently, the US does have a VICP; however, it has not been extended to COVID-19 vaccinations. The United States has a Countermeasure Injury Compensation Program, but it is not as expansive or easy to apply to as VICP.69

An alternate to vaccine mandates could include the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) and testing measures; however, under the current mandate, employers are not required to pay for testing. This may target the vaccine hesitant, as the additional cost of frequent testing could prove substantial and unsustainable.69 Other adjunctive alternatives could be explored, such as the use of spatial modeling to guide vaccination efforts through geographic targeting.70 Specific targeting, based on correlational data may be further enhanced by the concept of nudging interventions, which may include incentives, reminders, and reframing information dissemination.71 , 72

Conclusion

HCWs continue to battle the COVID-19 crisis and exhibit vaccination hesitancy. Correlates of hesitancy among HCWs appear to mimic correlates found in the general population, but additional areas of investigation could give further clarity to the complex nature of vaccine hesitancy. This review of the literature was impacted by the asynchronicity of data reporting, which made comparisons difficult and limited the synthesis of information. The gravity of the pandemic and the quick arrival of the COVID-19 vaccine is happening concurrently with an infodemic, in which large amounts of mis- or dis-information are being spread and to which HCWs may not be immune. Implications of findings may evolve as trends shift in vaccination and acceptance. The United States could look to policies of other nations as well as alternative interventions to combat hesitancy as an adjunct to mandates.

Author statements

Ethical approval

None sought.

Funding

This research was funded, in part, by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health grant #T42 OH 008422.

Competing interests

None declared.

References

- 1.Washington State Department of Health and Washington State Department of Labor and Industries . 2020 Dec. COVID-19 confirmed cases by industry sector.https://www.doh.wa.gov/Portals/1/Documents/1600/coronavirus/data-tables/IndustrySectorReport.pdf Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nguyen L.H., Drew D.A., Graham M.S., Joshi A.D., Guo C.-G., Ma W., et al. Risk of COVID-19 among front-line health-care workers and the general community: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2020 Sep;5(9) doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30164-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Research goals. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/about/strategicplan/immheal.html.

- 4.Burrer S.L., de Perio M.A., Hughes M.M., Kuhar D.T., Luckhaupt S.E., McDaniel C.J., et al. Characteristics of health care personnel with COVID-19 - United States, February 12-April 9, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 Apr 17;69(15):477–481. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32298247/ Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harrison R. COVID-19: occupational health issues for health care personnel. UpToDate. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/covid-19-occupational-health-issues-for-health-care-personnel/abstract/19.

- 6.US Department of Health and Human Services . 2020 Jun. Fact sheet: explaining operation warp speed.https://www.nihb.org/covid-19/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Fact-sheet-operation-warp-speed.pdf Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ball P. The lightning-fast quest for COVID vaccines - and what it means for other diseases. Nature. 2021 Jan 1;589(7840):16–18. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-03626-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baden L.R., el Sahly H.M., Essink B., Kotloff K., Frey S., Novak R., et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021 Feb 4;384(5) doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Polack F.P., Thomas S.J., Kitchin N., Absalon J., Gurtman A., Lockhart S., et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020 Dec 31;383(27) doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hinton D. 2020 Dec. Pfizer BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine emergency use letter of authorization.https://www.fda.gov/media/144412/download Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hinton D. 2020 Dec. Moderna COVID-19 vaccine emergency use letter of authorization.https://www.fda.gov/media/144636/download Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dooling K., McClung N., Chamberland M., Marin M., Wallace M., Bell B.P., et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices' (ACIP) interim recommendation for allocating initial supplies of COVID-19 vaccine — United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 Dec 11;69(49) doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6949e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.US Bureau of Labor Statistics . 2020. Employed persons by detailed industry, sex, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity.https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat18.pdf Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fisher K.A., Bloomstone S.J., Walder J., Crawford S., Fouayzi H., Mazor K.M. Attitudes toward a potential SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Dec 15;173(12) doi: 10.7326/M20-3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khubchandani J., Sharma S., Price J.H., Wiblishauser M.J., Sharma M., Webb F.J. COVID-19 Vaccination hesitancy in the United States: a rapid national assessment. J Community Health. 2021 Apr 3;46(2) doi: 10.1007/s10900-020-00958-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kreps S., Prasad S., Brownstein J.S., Hswen Y., Garibaldi B.T., Zhang B., et al. Factors associated with US adults' likelihood of accepting COVID-19 vaccination. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Oct 20;3(10) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.25594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malik A.A., McFadden S.M., Elharake J., Omer S.B. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the US. EClinicalMedicine. 2020 Sep;26 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pogue K., Jensen J.L., Stancil C.K., Ferguson D.G., Hughes S.J., Mello E.J., et al. Influences on attitudes regarding potential COVID-19 vaccination in the United States. Vaccines. 2020 Oct 3;8(4) doi: 10.3390/vaccines8040582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reiter P.L., Pennell M.L., Katz M.L. Acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine among adults in the United States: how many people would get vaccinated? Vaccine. 2020 Sep;38(42) doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.08.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bridgman A., Merkley E., Loewen P.J., Owen T., Ruths D., Teichmann L., et al. The causes and consequences of COVID-19 misperceptions: understanding the role of news and social media. Harvard Kennedy School Misinf Rev [Internet] 2020 Jun 18;1(3) https://misinforeview.hks.harvard.edu/article/the-causes-and-consequences-of-covid-19-misperceptions-understanding-the-role-of-news-and-social-media/ Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization. Infodemic. Available from: World Health Organization.

- 22.Islam M.S., Kamal A.H.M., Kabir A., Southern D.L., Khan S.H., Murshid Hasan S.M., et al. COVID-19 vaccine rumors and conspiracy theories: the need for cognitive inoculation against misinformation to improve vaccine adherence. PLoS One. 2021 May 1;16(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Islam M.S., Sarkar T., Khan S.H., Kamal A.H.M., Murshid Hasan S.M., Kabir A., et al. COVID-19–related infodemic and its impact on public health: a global social media analysis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020 Oct 7;103(4):1621–1629. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whittemore R., Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005 Dec;52(5) doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Page M.J., McKenzie J.E., Bossuyt P.M., Boutron I., Hoffmann T.C., Mulrow C.D., et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021 Dec 29;10(1) doi: 10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Center for Evidence based Management . 2014. Critical appraisal checklist for cross-sectional study.https://www.cebma.org/wp-content/uploads/Critical-Appraisal-Questions-for-a-Cross-Sectional-Study-july-2014.pdf Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abohelwa M., Elmassry M., Abdelmalek J., Payne D., Nugent K. 2019 Novel Coronavirus vaccination among post-graduate residents and fellows. J Prim Care Community Health. 2021 Jan 31;12 doi: 10.1177/21501327211022978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ciardi F., Menon V., Jensen J.L., Shariff M.A., Pillai A., Venugopal U., et al. Knowledge, attitudes and perceptions of COVID-19 vaccination among healthcare workers of an inner-city hospital in New York. Vaccines. 2021 May 17;9(5) doi: 10.3390/vaccines9050516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Famuyiro T.B., Ogunwale A., des Bordes J., Raji M. COVID-19: perceived infection risk and barriers to uptake of Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines among community healthcare workers. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021 Jul 15:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s40615-021-01093-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fontenot H.B., Mattheus D., Lim E., Michel A., Ryan N., Davis K.F., et al. Assessing licensed nurses COVID-19 vaccine attitudes and intentions: a cross-sectional survey in the state of Hawaii. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2021 Nov 2;17(11):3933–3940. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1947097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Halbrook M., Gadoth A., Martin-Blais R., Gray A.N., Kashani S., Kazan C., et al. Longitudinal assessment of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and uptake among frontline medical workers in Los Angeles, California. Clin Infect Dis. 2022 Apr 9;74(7):1166–1173. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuter B.J., Browne S., Momplaisir F.M., Feemster K.A., Shen A.K., Green-McKenzie J., et al. Perspectives on the receipt of a COVID-19 vaccine: a survey of employees in two large hospitals in Philadelphia. Vaccine. 2021 Mar;39(12) doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pacella-LaBarbara M.L., Park Y.L., Patterson P.D., Doshi A., Guyette M.K., Wong A.H., et al. COVID-19 vaccine uptake and intent among emergency healthcare workers. J Occup Environ Med. 2021 Oct;63(10) doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000002298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parente D.J., Ojo A., Gurley T., LeMaster J.W., Meyer M., Wild D.M., et al. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination among health system personnel. J Am Board Fam Med. 2021 May 4;34(3) doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2021.03.200541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shaw J., Stewart T., Anderson K.B., Hanley S., Thomas S.J., Salmon D.A., et al. Assessment of US healthcare personnel attitudes towards Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination in a large university healthcare system. Clin Infect Dis. 2021 Nov 16;73(10):1776–1783. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shekhar R., Sheikh A.B., Upadhyay S., Singh M., Kottewar S., Mir H., et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among health care workers in the United States. Vaccines. 2021 Feb 3;9(2) doi: 10.3390/vaccines9020119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Unroe K.T., Evans R., Weaver L., Rusyniak D., Blackburn J. Willingness of long-term care staff to receive a COVID-19 vaccine: a single state survey. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021 Mar 13;69(3) doi: 10.1111/jgs.17022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fossen M.C., Bethany M.D., Modak S.R., Parris S.M., Modak R.M. Who's vaccinated? A closer look at healthcare workers' coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and demographics. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2021 May 3:1–2. doi: 10.1017/ice.2021.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gadoth A., Halbrook M., Martin-Blais R., Gray A., Tobin N.H., Ferbas K.G., et al. Cross-sectional assessment of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among health care workers in Los Angeles. Ann Intern Med. 2021 Jun;174(6) doi: 10.7326/M20-7580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grumbach K., Judson T., Desai M., Jain V., Lindan C., Doernberg S.B., et al. Association of race/ethnicity with likeliness of COVID-19 vaccine uptake among health workers and the general population in the San Francisco Bay area. JAMA Intern Med. 2021 Jul 1;181(7) doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kociolek L.K., Elhadary J., Jhaveri R., Patel A.B., Stahulak B., Cartland J. Coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine hesitancy among children's hospital staff: a single-center survey. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2021 Jun 9;42(6) doi: 10.1017/ice.2021.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meyer M.N., Gjorgjieva T., Rosica D. Trends in health care worker intentions to receive a COVID-19 vaccine and reasons for hesitancy. JAMA Netw Open. 2021 Mar 23;4(3) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.5344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pamplona G.M., Sullivan T., Kotanko P. COVID-19 vaccination acceptance and hesitancy in dialysis staff: first results from New York City. Kidney Int Rep. 2021 Apr;6(4) doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2021.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schrading W.A., Trent S.A., Paxton J.H., Rodriguez R.M., Swanson M.B., Mohr N.M., et al. Vaccination rates and acceptance of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination among U.S. emergency department health care personnel. Acad Emerg Med. 2021 Apr 15;28(4) doi: 10.1111/acem.14236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoon P., Hall J., Fuld J., Mattocks S.L., Lyons B.C., Bhatkoti R., et al. Alternative methods for grouping race and ethnicity to monitor COVID-19 outcomes and vaccination Coverage. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021 Aug 13;70(32) doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7032a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.National Nurses United . 2020 Sep. Sins of omission: how government failures to track Covid-19 data may have led to more than 1,700 health care worker deaths and jeopardize public health.https://www.nationalnursesunited.org/sites/default/files/nnu/documents/0920_Covid19_SinsOfOmission_Data_Report.pdf Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 47.American Immigration Council . 2021. Immigrants in the United States.https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/immigrants-in-the-united-states Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stafford I.A., Parchem J.G., Sibai B.M. The coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine in pregnancy: risks, benefits, and recommendations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021 May;224(5) doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine . 2021 Jul. COVID-19 vaccination if you Are pregnant or breastfeeding.https://i7g4f9j6.stackpathcdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/02141531/COVID-vaccine-_Patients_JULY-29-2021_final.pdf Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rosseter R. 2019 Apr. Nursing fact sheet.https://www.aacnnursing.org/news-Information/fact-sheets/nursing-fact-sheet Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gaines K. 2021 Jan 19. Nurses ranked most trusted profession for 19 years in a row.https://nurse.org/articles/nursing-ranked-most-honest-profession/ Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 52.McClendon S., Proctor K. 2021. New survey of 13K U.S. nurses: findings indicate urgent need to educate nurses about COVID-19 vaccines.https://www.nursingworld.org/news/news-releases/2020/new-survey-of-13k-u.s.-nurses-findings-%20indicate-urgent-need-to-educate-nurses-about-COVID-19-vaccines/ Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 53.Proctor K., Levine Z. 2021 Aug. New survey data: nurses recommend Covid-19 vaccines.https://www.nursingworld.org/news/news-releases/2021/ew-survey-data--nurses-recommend-covid-19-vaccines/ Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 54.McClendon S., Proctor K. 2021 Sep. ANA urges US Department of Health and Human Services to declare nurse staffing shortage a national crisis.https://www.nursingworld.org/news/news-releases/2021/ana-urges-us-department-of-health-and-human-services-to-declare-nurse-staffing-shortage-a-national-crisis/ Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schaler L., Wingfield M. COVID-19 vaccine — can it affect fertility? Ir J Med Sci (1971 -) 2021 Oct 15:1–3. doi: 10.1007/s11845-021-02807-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ciapponi A., Bardach A., Mazzoni A., Alconada T., Anderson S.A., Argento F.J., et al. Safety of components and platforms of COVID-19 vaccines considered for use in pregnancy: a rapid review. Vaccine. 2021 Sep;39(40) doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Theiler R.N., Wick M., Mehta R., Weaver A.L., Virk A., Swift M. Pregnancy and birth outcomes after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2021 Nov;3(6) doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2021.100467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zauche L.H., Wallace B., Smoots A.N., Olson C.K., Oduyebo T., Kim S.Y., et al. Receipt of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines and risk of spontaneous abortion. N Engl J Med. 2021 Oct 14;385(16) doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2113891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wainstock T., Yoles I., Sergienko R., Sheiner E. Prenatal maternal COVID-19 vaccination and pregnancy outcomes. Vaccine. 2021 Oct;39(41) doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Joseph N.T., Rasmussen S.A., Jamieson D.J. The effects of COVID-19 on pregnancy and implications for reproductive medicine. Fertil Steril. 2021 Apr;115(4) doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Neely S., Eldredge C., Sanders R. Health information seeking behaviors on social media during the COVID-19 pandemic among American social networking site users: survey study. J Med Internet Res. 2021 Jun 11;23(6) doi: 10.2196/29802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Loomba S., de Figueiredo A., Piatek S.J., de Graaf K., Larson H.J. Measuring the impact of COVID-19 vaccine misinformation on vaccination intent in the UK and USA. Nat Human Behav. 2021 Mar 5;5(3) doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Neely S.R., Eldredge C., Ersing R., Remington C. Vaccine hesitancy and exposure to misinformation: a survey analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2022 Jan;37(1):179–187. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-07171-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Supreme Court of the United States . 2022 Jan 13. 595 U. S. (2022) 21A240 Biden v. Missouri.https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/21pdf/21a240_d18e.pdf Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hagan K., Forman R., Mossialos E., Ndebele P., Hyder A.A., Nasir K. COVID-19 vaccine mandate for healthcare workers in the United States: a social justice policy. Expet Rev Vaccine. 2021 Jan;21(1):37–45. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2022.1999811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wise J. Covid-19: France and Greece make vaccination mandatory for healthcare workers. BMJ. 2021 Jul 14;374:n1797. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Paterlini M. Covid-19: Italy makes vaccination mandatory for healthcare workers. BMJ. 2021 Apr 6;373:n905. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.D'Errico S., Zanon M., Concato M., Peruch M., Scopetti M., Frati P., et al. “First Do No Harm”. No-fault compensation program for COVID-19 vaccines as feasibility and wisdom of a policy instrument to mitigate vaccine hesitancy. Vaccines. 2021 Sep 30;9(10) doi: 10.3390/vaccines9101116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.van Tassel K., Shachar C., Hoffman S. Covid-19 vaccine injuries — preventing nnequities in compensation. N Engl J Med. 2021 Mar 11;384(10) doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2034438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mollalo A., Tatar M. Spatial modeling of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the United States. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Sep 8;18(18) doi: 10.3390/ijerph18189488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Reñosa M.D.C., Landicho J., Wachinger J., Dalglish S.L., Bärnighausen K., Bärnighausen T., et al. Nudging toward vaccination: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health. 2021 Sep 30;6(9) doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pennycook G., McPhetres J., Zhang Y., Lu J.G., Rand D.G. Fighting COVID-19 misinformation on social media: experimental evidence for a scalable accuracy-nudge intervention. Psychol Sci. 2020 Jul 30;31(7) doi: 10.1177/0956797620939054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]