Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Restoration of the bone defects caused by infection or disease remains a challenge in orthopedic surgery. In recent studies, scaffold-free engineered tissue with a self-secreted extracellular matrix has been proposed as an alternative strategy for tissue regeneration and reconstruction. Our study aimed to engineer and fabricate self-assembled osteogenic and scaffold-free tissue for bone regeneration.

METHODS:

Osteogenic scaffold-free tissue was engineered and fabricated using fetal cartilage-derived progenitor cells, which are capable of osteogenic differentiation. They were cultured in osteogenic induction environments or using demineralized bone powder for differentiation. The fabricated tissue was subjected to real-time qPCR, biochemical, and histological analyses to estimate the degree of in vitro osteogenic differentiation. To demonstrate bone formation in an in vivo environment, scaffold-free tissue was transplanted into the dorsal subcutaneous site of nude mice. Bone development was monitored postoperatively over 8 weeks by the observation of calcium deposition in the matrix.

RESULTS:

In the in vitro experiments, engineered osteogenically induced scaffold-free tissue demonstrated three-dimensional morphological characteristics, and sufficient osteogenic differentiation was confirmed through the quantification of specific osteogenic gene markers expressed and calcium accumulation within the matrix. Following the evaluation of differentiation efficacy, in vivo experiments revealed distinct bone formation, and that blood vessels had penetrated the fabricated tissue.

CONCLUSION:

The novel engineering of scaffold-free tissue with osteogenic potential can be used as an optimal bone graft substitute for bone regeneration.

Keywords: Bone regeneration, Osteogenesis, Fetal cartilage-derived progenitor cells, Scaffold-free tissue engineering

Introduction

Most bones develop from the endochondral ossification (ECO), in which cartilage undergoes hypertrophy and is replaced with mineralized bone [1]. Bone has the ability to self-heal under normal conditions through soft and hard callus formation and remodeling process that interact with the extracellular matrix (ECM), growth factors, and osteoprogenitor cells [2]. However, healing may not be effective or fail in the presence of injuries, defects, or metabolic influence; for instance, osteomyelitis, disease, trauma, tumor resection, and osteoporosis surgical intervention is then generally required [3]. Currently, in clinical treatments, autografting is performed as a standard treatment to repair bone and has a low risk of rejection. However, additional open surgery is needed to harvest the grafts, donor site morbidity, and limitation in harvesting sufficient bone quantity for use [4]. While allogeneic and xenogeneic decellularized grafts are easily used, osteogenic potential can be impeded by issues such as the elimination of cellular components by immune reactions, disease transmission risk, and considerable expense [5]. For these reason, bone healing and regeneration have remained challenging clinical problems. To overcome these issues, new technologies have been developed for combining engineered bone tissue with existing cells, growth factors, and scaffold to promote bone regeneration [6].

The ideal bone substitute for use in tissue engineering possesses osteogenic properties that are osteoconductive, osteoinductive, and that can promote neovascularization [7]. The field is divided into scaffold-based and scaffold-free engineering. The combination of scaffold-based technology with growth factors can promote both osteoconductive and inductive signals [8]. Also, cells were needed to produce the bone; thus, they are loaded onto scaffolds which form an osteogenic environment and interact with the elements require for bone regeneration. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have been widely used in most studies because of their differentiation potential [9–11]. However, although they are able to treat bone defects, their effectiveness is limited by uneven cell distribution in the scaffold, which induces cell necrosis at the core; due to insufficient nutrient transport, unmanageable interactions leading to cell mortality, and unstable scaffold degradation, causing inflammation and immune response in vivo [12, 13].

Recently, the engineering of scaffold-free tissue has become an alternative strategy to overcome the limitations of scaffold-based tissue engineering. Cell sheet technology has been applied as a form of scaffold-free tissue engineering, in various tissue regeneration applications, such as for bone, hearts, and eyes [14–16]. The cell sheet structure formed from a self-secreted matrix can be used as a natural scaffold, better mimicking native tissue to avoid the side effects associated with artificially manufactured biomaterial scaffolds [17, 18]. Although cohesive cell-cell and cell-ECM interactions enhance tissue regeneration, their morphological characteristics and thinness mean their applicability to hard tissue regeneration limited by inappropriate mechanical properties and the necessity for additional scaffolding to maintain their structure [19]. In further studies on cell sheet-based techniques, the engineering of scaffold-free tissue has been suggested for tissue repair applications [20, 21]. Scaffold-free tissues are fabricated by the serial processing of primary cultured cells in high densities and subsequent culturing in three-dimensional (3D) self-assembled pellets [22]. The cells grown in in vitro 3D environments reveal proliferation and differentiation characteristics close to in vivo conditions [23]. Engineered tissues has no size or shape restrictions and can be plasticity applied directly to treatment sites, minimizing any gaps between graft and host tissue, thus potentially improving integration and promoted tissue regeneration [24]. In addition, 3D engineered tissue possess the microstructural characteristics of cells and have ECM interactions similar to native tissue, which can promote specific differentiation [25]. The scaffold-free tissue engineered, which has these advantages, has been previously studied in relation to cartilage repair; however, in this study, we applied it as osteogenically for bone regeneration.

In several studies, the osteo-induction of cell sheets or 3D micro pellets cultured in osteogenic media have exhibited significantly better osteogenic differentiation than non-osteo-induction material cultured in regular media, with comparable culturing [26]. Bone powder has been used as a biomaterial for the promotion of osteogenic differentiation [27, 28]. It is composed of organic factors such as collagen, proteoglycan, residual calcium, and bone morphogenic proteins, which are known as osteoconductive and inductive materials that accelerate osteogenesis. Demineralized bone powder is widely used in bone regeneration research, and combined with natural polymers such as fibrin, collagen, and gelatin as a moldable bone graft; with common application in dental and orthopedic treatments [29–31].

Our previous study has revealed that, in accordance with ECO bone formation theory, fetal cartilage-derived progenitor cells (FCPCs) possess stem cell characteristics, low oncogenic activity, and good proliferation [32]. FCPC-derived scaffold-free tissue has been successfully engineered tissue and fabricated following the process described in [22]. Engineered scaffold-free tissue with osteogenic potential can be used as a bone regeneration graft at sites with spatial defects. We compare the osteogenic potential of engineered osteo-induction tissue obtained via a novel scaffold-free method and an established osteo-induction material method, which relied on mixing cells with bone powder. The resulting tissue was transplanted at dorsal subcutaneous sites in nude mice, to compare the extent of in vivo and in vitro osteogenesis.

Materials and methods

FCPCs culture and osteogenic differentiation

Fetal cartilage-derived progenitor cell (FCPC) experiments were conducted in accordance with institutional review board regulations (IRB No. 200820-1A). FCPCs were cultured in high-glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; GE, Healthcare, Boston, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA), 1% antibiotic-antimycotic (AA; Gibco), and 5 ng/ml recombinant human FGF (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). When cells attained 80% confluence, 0.5% Trypsin-EDTA (Gibco) was used to detach the cells and they were replated. The culture dishes were incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Passage 4 FCPCs were used to examine and compare osteogenic differentiation capacity against the human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs; ATCC®) that are normally used in differentiation research. FCPCs and BM-MSCs were seeded at 5000 cells/cm2 in plates and after confluence at 70%, they were cultured in osteogenic induction medium DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS, 1% AA, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), 50 µg/ml ascorbate-2 phosphate (Sigma), and 100 nM dexamethasone (Sigma). After 2 and 3 weeks of culture, cells were washed with Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline without calcium and magnesium (D-PBS; WELGENE Inc., Daegu, Korea) and fixed in 70% cold ethanol for 1 h. The samples were then stained with 40 mM alizarin red S (Sigma) solution to determine mineralized deposition. Subsequently, the staining solution was removed, and excess stain was washed away with D-PBS. To quantify the degree of mineralization, the dye was extracted with 10% cetylpyridinium chloride (Sigma), and intensities was measured at 540 nm.

Fabrication of FCPCs-engineered scaffold-free tissue

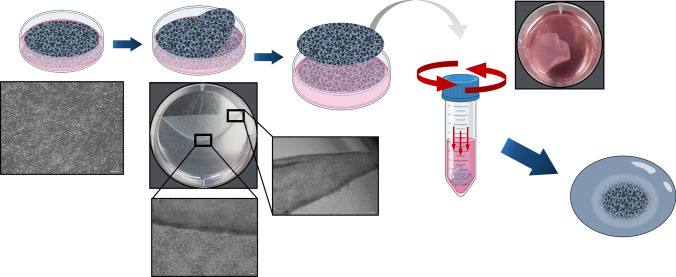

The engineered tissue was fabricated according to a previously published protocol [33]. Briefly, 2×105 cells/cm2 FCPCs were cultured in a high-density monolayer with chondrogenic medium comprising DMEM with 1.25 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA; Millipore, MA, USA), 100 µg/ml sodium pyruvate (Sigma), insulin-transferrin-selenium (ITS; Gibco), 40 µg/ml L-proline (Sigma), 50 µg/ml ascorbate-2 phosphate and 100 nM dexamethasone. They were incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 until fully confluent as a thin membrane. Subsequently, the membranes were detached from the plate using a cell lifter and transferred to individual tubes filled with 10 ml of the prepared medium. The tubes were centrifuged at 100 × g for 20 min to crumple the membrane into a pellet. The cells were incubated in a humidified atmosphere and then transferred to a 6-well culture plate (Fig. 1). The medium was changed every 3 days for 1, 2, and 4 weeks of culturing. The engineered tissue was divided into three groups: (1) scaffold-free tissue cultured in standard medium (DMEM, 5% FBS, and 1% AA), designated as normal-tissue; (2) scaffold-free tissue cultured in osteogenic induction medium, designated as osteo-tissue; and (3) the method of mixing 1 cc scaffold-free tissue with 0.2 mg demineralized bone powder (InduCera, Oscotec, Korea), before culturing in osteogenic medium, designated as osteo/BP-tissue.

Fig. 1.

The fabrication process for the engineered scaffold-free tissue. 2 × 105 cells/cm2 of FCPCs were cultured in high density monolayer. After created thin membrane, they were detached from the dish by cell lifter and centrifuge them to make pellet structural tissue

Cell viability and cytotoxicity in 3D environment

Fluorescence staining was performed using a live/dead cell viability assay kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) to confirm cell viability during culture in a 3D environment, as opposed to monolayer cell culture. Each group of engineered tissue was soaked in saline consisting of calcein-AM (green fluorescence for live cells) and EthD-1 (red for dead cells) for staining. After 1 h of staining, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (DUKSAN Pure Chemical, Korea) and cryo-sectioned into 5 µm sections. Finally, the obtained specimens were observed under a fluorescence microscope (Axio-Observer 5; Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) to obtain counts of living and dead cells.

The cytotoxicity of the treated bone powder was assessed using a WST assay (EZ-cytox, DoGenBio, Seoul, Korea). Normal-tissue was mixed with 1, 3, 5, and 10 mg of bone powder per engineered tissue and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2. The absorbance of the generated formazan was measured at 450 nm, following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Real time qPCR analysis

RNA from the engineered tissue was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), according to the standard protocol. 1 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using a cDNA synthesis kit (CellSafe, Yongin, Korea). To assess the degree of osteogenic differentiation per period, specific primers such as type I collagen (COL1A1), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx2), and osteopontin (OPN) were used for PCR amplification. The primer sequences are listed in Table 1. 1x SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems Inc., Carlsbad, CA, USA) was mixed with each of the specific primers, and cDNA was prepared. Gene expression levels were normalized to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as an internal control and measured using the comparative method.

Table 1.

Information on the primers used for Real Time qPCR

| Genes | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| Col I | 5′ GTA ATG CCC CCT CCC GTT GT 3′ | 5′ CGG GAG GTC TTG GTG GTT TTG 3′ |

| ALP | 5′ GGA TGT TAC CGA GAG CGA GAG 3′ | 5′ TTC AGT TCC GGT AGG AGG GT 3′ |

| Runx2 | 5′ TGT CCA CAG AAG TGC TCC AG 3′ | 5′ CTC ATC ACA CTG GGG TTG TG 3′ |

| OPN | 5′ CTC CAG TTG TCC CCA CAG TAG 3′ | 5′ AGT CAG AAC CAT CAG GTG TGT 3′ |

| GAPDH | 5′ CCT GCA CCA CCA ACT GCT TA 3′ | 5′ CCC ATT CCC CAG CTC TCA TAC 3′ |

Osteogenic differentiation analysis

Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity was measured using a colorimetric assay based on the conversion of p-NPP into p-nitrophenol (p-NP). After 1, 2, and 4 weeks of culturing, three groups of engineered tissues were lysed with 1% Triton X-100 (Sigma) with 25 mM sodium carbonate buffer, and the supernatant was obtained by centrifugation at 1700 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. In a 96-well plate, 25 µl of cell lysate was added to 50 µl of ALP yellow substrate (Sigma). The plate was incubated for 30 min in the dark, and the reaction was stopped with 3 M NaOH. The activation of the group was measured using a microplate reader absorbance at 405 nm. The amount of p-NP was normalized to the protein concentration in each fabricated tissue and the reaction time. The protein concentration was quantified by Bradford protein assay using a Bradford assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

The calcium concentration in the engineered tissue was measured using a calcium colorimetric assay kit (Sigma), to estimate cell differentiation. Three groups of engineered tissues were lysed with lysis buffer (RIPA; Rockland, PA, USA) for 1, 2, and 4 weeks. The cell lysate was treated with 90 μl chromogenic agent with 60 μl of calcium assay buffer following the manufacturer’s protocol, and the reaction was incubated at room temperature for 10 min. Subsequently, calcium ion concentration in the tissue was measured at 575 nm using a microplate reader.

Each group of engineered tissue was cultured in their respectively assigned treatments for several weeks, and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde overnight without decalcification to determine mineralization. The sections were embedded in paraffin and cut into 5 μm thick sections. Sectioned slides were subjected to deparaffinization and serial hydration before staining. The sections were stained with alizarin red s and von Kossa following the standard protocol. 2% alizarin red s solution was prepared with ddH2O at pH 4.6, and stained with red sticking to calcium ions. In addition, von Kossa staining was performed with 1% sliver nitrate (Sigma) in UV light for 1 h to substitute the calcium with silver ions, and as the silver ions reacted to the UV light, they were replaced with dark brown metallic silver. The cells were then counterstained with 0.1% nuclear fast red (Sigma). The stained sections were observed under a microscope.

Surgical procedure for transplantation

All surgical experiments were performed with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Pukyong National University (PKNUIACUC-2021-17). Before implantation, each group of the engineered tissues, normal, osteo, osteo/BP-tissues were cultured in each conditioning medium for 2 weeks in vitro. The engineered tissues were transplanted into 6-weeks-old male athymic nude mice (Koatech, Korea). The mice were anesthetized using isoflurane, and a subcutaneous incision was made on their backs, to create a dermal space for grafting the tissues. Each mouse was grafted with three sets of the engineered tissues, distributed both sagittally and transversely, and the wounds were primarily closed with sutures. The surgical procedure was performed under sterile conditions. The mice were sacrificed, and the grafted engineered tissues were removed for analysis at 2, 4, and 8 weeks post-transplantation.

FCPCs-engineered tissue for bone regeneration in vivo

After harvesting the transplanted the tissues at 2 and 8 weeks, to estimate the degree of bone formation, the compressive strength of the tissue was measured using a universal testing machine (UTM; LR5K Plus, LLOYD instruments, Bognor Regis, UK). The samples were positioned on the bottom plate of the machine and compressed at a speed 0.1 mm/min. The machine was stopped automatically after moving the distance between the top to bottom plate. The compressive strength was calculated using the maximum load and volume of the samples (n = 5).

Calcium accumulation in in vivo transplanted tissues was measured using a calcium colorimetric assay kit (Sigma). At 2, 4, and 8 weeks post-operation, each group of tissue was lysed with RIPA buffer to obtain the cell lysate. Following the manufacturer’s protocol, the cell lysate was mixed with a chromogenic reagent and calcium assay buffer. They were normalized to the protein concentration in each engineered tissue using the Bradford protein assay. The calcium concentration was measuring by the absorbance at 575 nm using a microplate reader.

Histological examination

Transplanted tissues from 2- and 8-weeks post-operation were harvested from the mice and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h. They were embedded in paraffin and sectioned into 5 μm. Before staining, slides were incubated at 60 °C overnight, cleared in xylene (DUKSAN), and dehydrated. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), alizarin red s and von Kossa to observe the calcium and mineral deposition interior matrix of the tissue, which indicated formation of the bone. Photomicrographs were obtained from the stained sections.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical significance was determined using Students’ t-test after analysis of variance (ANOVA). One-way ANOVA was used to analyze the results among different groups and at each time points. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. In the figure, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 indicate analysis between each time point of the same group, #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, and ###p < 0.001 indicate analysis between groups at the same time point.

Results

Comparison of osteogenic differentiation abilities of FCPCs

Alizarin red s staining was used to determine and compare the osteogenic differentiation of FCPCs with human bone marrow MSCs in vitro. The microscope images of the cells stained at 3 weeks showed noticeable differences in calcium deposition between FCPCs and MSCs (Fig. 2A) at every stage of osteogenesis. The intensity of the extracted dye was also significantly higher in FCPCs (780.7 ± 21%) than in BM-MSCs (638 ± 77%) (Fig. 2B). The measured value of a control group of each cell that cultured with DMEM, 10% FBS, and 1% AA was used for comparison of mineralization.

Fig. 2.

Compare of osteogenic differentiation of fetal cartilage-derived progenitor cells (FCPCs) and MSCs in vitro. A To determine the osteogenic differentiation of the cells, the degree of the extracellular matrix (ECM) mineralization was examined by alizarin red s staining. B For the quantitative analysis, extracted the dye and measured the intensity absorbance at 540 nm. **p < 0.01 indicate significant difference between FCPCs and MSCs (Scale bars = 50 μm)

Fabrication of the FCPCs scaffold-free engineered tissue

The shape of the engineered tissue during culture was disk-type, and they grew larger in volume over time (Fig. 3A). The engineered tissues that were cultured in osteogenic medium groups were larger than normal, due to the ascorbic acid added to the medium to promote the synthesis of collagenic ECM components (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Characteristics of engineered scaffold-free tissue. A Morphological differences between engineered tissue. Gross observation of FCPC derived tissue on days 7, 14, 28 after conditioning. Normal-tissue, Osteo-tissue, Osteo/BP-tissue. B Size and volume were measured in Image J. C Viability of the cells in engineered tissue was determined by live/dead assay. The cell viability during in 3D culture environments and live cells were stained into green (scale bar = 100 µm). D WST assay was performed to confirm the cytotoxicity of bone powder in FCPCs over 24 h, following dosage of various amounts of bone powder. Data was normalized to the untreated control group. **p < 0.01 indicates significant differences with the control group

In contrast to cells in a monolayer, 3D environment cell culture induces hypoxia and necrosis in interior cells because nutrients and oxygen cannot be homogenously assessed. The cultured tissues form each period were cut into 5 µm sections; living cells were stained green, and dead cells were stained red (Fig. 3C). The result revealed not only cell viability in the 3D environment, but also cell proliferation, as the culture duration increased. Figure 3C depicts the increases in cell densities with culture duration.

A WST assay was conducted to determine an appropriate amount of bone powder that would not affect cell survival. The results indicated that 1 mg of bone powder did not result in cytotoxicity, compared to 3, 5, and 10 mg treatment groups (Fig 3D). Thus, 1 mg of bone powder per engineered tissue was used to cultivate osteo/BP-tissue groups.

Expression of the osteogenic gene markers

Real-time qPCR analysis was performed for further analysis of osteogenic phenotypes. The group type and culture duration resulted in different levels of gene expression (Fig. 4). The expression of type I collagen, which was revealed in the proliferative phase of osteoprogenitors, gradually decreased as differentiation proceeded. However, the differences were not statistically significant (P > 0.05). In addition, the early osteoblast marker ALP was expressed at 1 week, indicating that differentiation rapidly initiated. Osteopontin which was identified at the mature osteoblast-induced mineralization phase, was expressed in week-4 differentiated groups. It has been reported that engineered osteogenic induction tissue has the potential for bone formation after 4 weeks for culturing.

Fig. 4.

Comparison between osteo-tissue and osteo/BP-tissue expressions of bone-related genes. Real-time qPCR analysis showed that the mRNA expression of Col I and ALP after 1 week of culturing, and OPN was expressed after 4 weeks of culturing. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 indicated significant differences between each time point, and #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, and ###p < 0.001 indicated significant differences between the samples

Differentiation ability of the FCPCs-engineered tissue

Three groups of FCPC-derived engineered tissues were cultured in the conditioned medium without exogenous growth factors and scaffolds. The engineered tissues were characterized by osteogenic differentiation corresponding to in vitro culture duration.

The ALP activity assay was performed after 1, 2, and 4 weeks of culturing (Fig. 5A). ALP is an early marker for osteoblastic differentiation and has been shown to differentiate into pre-osteoblasts. Both engineered tissues, which were cultured in osteogenic medium, showed slight statistical difference at 1 week. In addition, after 4 weeks of culturing in osteo-induction medium, activation was significantly higher than that in the normal-tissue.

Fig. 5.

Osteogenic differentiation of engineered tissue. Assay of the ALP activity and calcium concentration to determine osteogenic differentiation. Each group of tissues was cultured for 1, 2, and 4 weeks respectively in their assigned culture treatments. A ALP activity was measured using the p-nitrophenyl phosphate assay and indicated enormous increases in differentiation over time. B After 4 weeks, calcium accumulation significantly increased in the osteo-tissue group. Data were normalized by total protein content. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 indicated significant differences between each time point, and #p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, and ###p < 0.001 indicated significant differences with normal-tissue. Histological analysis was conducted with: C alizarin red s; and D von Kossa staining. Stained week-4 tissue from both osteo-tissue groups presented notable differences with other groups. Bone powder and mineralized matrix were stained red by alizarin red S and dark brown by von Kossa. (Scale bars = 50 μm)

The calcium concentration in the tissue was quantified using a colorimetric assay (Fig. 5B). The engineered osteo-tissue from 4 weeks, showed significantly higher calcium accumulation than the other conditioning groups. Calcium deposition in the ECM showed strong correlation with ALP activation.

Also, calcium mineralization in the interior of differentiated tissue was observed using histological analysis with alizarin red s and von Kossa staining (Fig. 5C, D). There was no significant difference between any of the groups after 1 and 2 weeks of culturing. However, at 4 weeks, both the stains of the osteo-tissue groups exhibited calcium deposition, observed as red and dark brown coloration, which indicated that differentiated osteoblasts had been activated to mineralized ECM.

Formation of bone tissue in vivo

As shown in Fig. 6A, all groups of transplanted tissues showed notable changes in volume compared to before transplantation. The results of the compressive test indicated that in vitro osteogenically induced engineered tissue showed a high level of compression resistance before transplantation, compared to the normal-tissue. In particular, the osteo-tissue group exhibited a two-fold increase in stiffness at 8 weeks after transplantation. This result indicated that bone had begun to form in the tissue (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Formation of bone tissue in vivo. A Morphological characteristics of in vivo transplanted engineered tissue. The gross image indicated notable sized differences between before and after transplanting the FCPC-derived engineered tissues. Normal-tissue, Osteo-tissue, Osteo/BP-tissue. Size was measured using Image J. B To determine the mechanical strength of engineered tissue grafted in vivo. The compression test was performed after 2 and 8 weeks post-transplanting, and osteo-tissue groups demonstrated increased stiffness. C Calcium accumulation in the transplanted engineered tissue. After transplanted each group of tissue for 2, 4, and 8 weeks, each tissue treatment group was harvested and examined to quantify calcium ion concentration. Calcium accumulation then measured using a colorimetric assay; after 8 weeks, the transplanted osteo-tissue group exhibited significantly increase than other groups. Data were normalized with protein concentration. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 indicate significantly different between duration of transplanted and ##p < 0.01 and ###p < 0.001 indicate significant differences with the normal-tissue

Engineered tissues were analyzed for calcium concentration after 2, 4, and 8 weeks (Fig. 6C). The results showed that 8 weeks osteo-tissue at expressed a different level of calcium accumulation than the normal. The osteo/BP-tissue was not statistically different, but a plot of the measurements indicated that calcium did appear to increase over time, after transplantation.

After transplantation, the specimens were harvested from the back of the subcutaneous tissue and histological analysis was performed on the excised tissue. H&E staining revealed that several spaces had been created in the engineered osteogenic induction tissue, which indicated that blood vessels had penetrated into the tissues, in contrast to the normal. Moreover, the hypertrophy of cartilage cells was observed in the normal-tissue (Fig. 7A). Alizarin red s and von Kossa staining indicated calcium deposition in the newly formed bone. In the osteo-tissue group, after 2 weeks of transplantation, ossification and osteoblast lining were apparent. By 8 weeks, some osteoblasts had become trapped inside bony pockets (lacunae), where they had differentiated into osteocytes and induced the formation of a mineralized matrix (Fig. 7B, C).

Fig. 7.

Histological analysis performed on transplanted engineered tissue. A H&E staining was carried out to visualize cell morphology and constructed ECM. After 2 weeks, transplant groups appeared to slightly proceed towards ossification. After 8 weeks, osteo-tissue indicated increasing osteoid formation with ongoing mineralization. The mineralization in transplanted engineered tissue was confirmed by B alizarin red s and C von Kossa staining. Staining the osteo-tissue group using both these stains after 8 weeks presented notable mineralization, compared to the other groups. Also, after 2 weeks, osteo-tissue presented osteoid formation. The black arrows indicated osteoid and differentiated osteocyte in lacunae. The red arrow indicates the penetration of blood vessels into engineered tissue matrix (Scale bar = 50 µm)

Discussion

3D cell culture grafting is an emerging strategy being developed in bone tissue engineering. Such tissue can interact with osteogenic progenitor cells, ECM, and growth factors, which play an important role in successful bone formation [34]. Various types of biomaterials used in scaffold-based bone tissue engineering exhibit both osteoinductive and conductive properties [35]. However, transplanted scaffolds may induce partial tissue inflammation and cell necrosis from to inadequate access to nutrients and oxygen [36, 37]. Therefore, 3D scaffold-free technology has recently been introduced as a promising method for tissue engineering [38, 39]. Scaffold-free tissue can be engineered using self-assembly methods in 3D culture environments, and the technique has already been successfully demonstrated in cartilage repair applications [23, 40]. In this study, we confirmed that a high density of FCPCs can be used to engineer 3D tissue with osteogenic potential, without the use of artificial scaffolds. The resulting osteogenic induction tissue expressed a osteoblastic key marker and produced calcified depositions in the matrix interior.

The 3D cultured engineered scaffold-free tissue with ECM generated from progenitor cells was a significant factor that influenced the regulation of cell behavior and functions [23]. The ECM contains many bioactive molecules necessary for cell and tissue homeostasis, such as cell-cell junctions, adhesion molecules, growth factor receptors, and ion channels, which supports cell survival and mediates direct adhesion to target organs [41]. Moreover, cell-ECM interactions can affect cell functions through receptor-mediated signaling, and the ECM regulates the mobilization of differentiation and growth factors; thus modulating cell proliferation and controlling cell phenotype [42]. It was shown that culturing in 3D microenvironments formed multiple layers of cells with large amounts of cell components such as ribosomes, vesicles, and mitochondria; that induced and activated high levels of metabolic activity and protein synthesis, resulting in decisively beneficial effects on proliferation and differentiation, similar to that observed in situ [43].

In the process of fabrication osteo/BP-tissue, physical force was applied to mix bone powder with engineered tissue that had already formed complete cell-cell and cell-ECM interactions. Cell matrix contact was disrupted by this mixing process, negatively influencing on the differentiation of cells and subsequent osteogenesis. For this reason, despite the initial expectation that bone powder will accelerate osteogenesis, bone formation in osteo/BP-tissue was observed to take slightly longer than osteo-tissue, in both in vitro and in vivo analyses (Figs. 4, 5, 6, 7).

The results of the study showed that osteogenically induced engineered tissue has the potential to form bone, and osteo-tissue demonstrated faster osteogenic differentiation capacity than osteo/BP-tissue. This finding was supported by histological analysis; both alizarin red s and von Kossa showed positive differences in calcium deposition in the ECM of the tissue (Figs. 5, 7). The results of biochemical analysis with ALP activity reaction and calcium concentration (Fig. 5 A, B) were also consistent with the results of previous histological assays. These results were supported by real time qPCR analysis, which showed several key markers related to osteoblast differentiation over time (Fig. 4). Osteoprogenitor cells were expressed as type I collagen in the early stages of differentiation into osteoblasts, and the mature phase mineralized the matrix expression of OPN. These results suggest that engineered tissues that were cultured both in vitro and in vivo not only undergo osteoblast differentiation, but also create mineralized matrix for bone formation.

In addition, the histological assay showed that 8 weeks post-transplantation normal-tissue (without osteogenic induction) expressed endochondral ossification factors that underwent cartilage cell hypertrophy prior to ossification. In other osteogenically induced engineered tissues, calcification occurs in internal tissue sites, similarly to endochondral ossification. Defects in intramembranous ossification were at risk of avascular necrosis and degradation, that vascular network was not simultaneously engineered due to cells underwent direct differentiation [44]. Therefore, FCPC-derived engineered tissues were exposed to chondrogenic and osteogenic media, thereby mimicking endochondral ossification phenomenon, which secrete more proteoglycan and a collagen-rich matrix. This would yield more robust bone formation than cultured osteogenic medium alone.

In conclusion, the study demonstrated that engineered scaffold-free tissue with osteogenic induction could undergo a differentiation phase in a 3D culture environment without any exogenous growth factors. The advantage of the engineered tissue, which was pre-cultured in an osteogenic induction environment, is that it can be transplanted with the capacity for osteogenesis without disrupting cell matrices and interactions, and thus, accelerate osteogenic differentiation. The engineered tissue generated bone-like mineralized matrix in vitro and ossified in vivo. This suggests that the osteogenic potential of engineered scaffold-free tissue, which is plasticity and flexibility, can be applied as a novel graft tissue for filling defective segmental bone sites, for bone regeneration and restoration.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by a National Research Foundation (NRF) Grant (2019M3E5D1A02070861).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical statement

The cell (FCPCs) experiments were conducted with the approval of the Institutional Review Board of Inha University (IRB No. 200820-1A). All surgical experiments were performed under the approval by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Pukyong National University (IACUC approval No. PKNUIACUC-2021–17).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Setiawati R, Rahardjo P. Bone development and growth. In: Yang H, editor. Osteogenesis and bone regeneration. IntechOpen Limited. London; 2019. Chapter 1.

- 2.Schindeler A, Mcdonald MM, Bokko P, Little DG. Bone remodeling during fracture repair: The cellular picture. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2008;19:459–66. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Salgado AJ, Oliveira JT, Pedro AJ, Reis RL. Adult stem cells in bone and cartilage tissue engineering. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2006;1:345–364. doi: 10.2174/157488806778226803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dimitriou R, Mataliotakis GI, Angoules AG, Kanakaris NK, Giannoudis PV. Complications following autologous bone graft harvesting from the iliac crest and using the RIA: a systematic review. Injury. 2011;42:S3–S15. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dimitriou R, Jones E, Mcgonagle D, Giannoudis PV. Bone regeneration: current concepts and future directions. BMC Med. 2011;9:66. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang D, Tare RS, Yang LY, Williams DF, Ou KL, Oreffo RO. Biofabrication of bone tissue: approaches, challenges and translation for bone regeneration. Biomaterials. 2016;83:363–382. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janicki P, Schmidmaier G. What should be the characteristics of the ideal bone graft substitute? Combining scaffolds with growth factors and/or stem cells. Injury. 2011;42:S77–S81. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henkel J, Woodruff MA, Epari DR, Steck R, Glatt V, Dickinson IC, et al. Bone regeneration based on tissue engineering conceptions—a 21st century perspective. Bone Res. 2013;1:216–248. doi: 10.4248/BR201303002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Futrega K, Mosaad E, Chambers K, Lott W, Clements J, Doran MJC, et al. Bone marrow-derived stem/stromal cells (BMSC) 3D microtissues cultured in BMP-2 supplemented osteogenic induction medium are prone to adipogenesis. Cell Tissue Res. 2018;374:541–553. doi: 10.1007/s00441-018-2894-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu T, Zhang H, Yu W, Yu X, Li Z, He L. The combination of concentrated growth factor and adipose-derived stem cell sheet repairs skull defects in rats. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2021;18:905–913. doi: 10.1007/s13770-021-00371-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang G, Kim YN, Kim H, Lee BK. Effect of Human Umbilical Cord Matrix-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells on Bisphosphonate-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw. Tissue Eng Regen Med 2021;18:975–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Singhatanadgit W, Varodomrujiranon M. Osteogenic potency of a 3-dimensional scaffold-free bonelike sphere of periodontal ligament stem cells in vitro. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Radiol. 2013;116:e465–e472. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2012.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muschler GF, Nakamoto C, Griffith LG. Engineering principles of clinical cell-based tissue engineering. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:1541–1558. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200407000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang J, Yamato M, Kohno C, Nishimoto A, Sekine H, Fukai F, et al. Cell sheet engineering: recreating tissues without biodegradable scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2005;26:6415–6422. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamato M, Akiyama Y, Kobayashi J, Yang J, Kikuchi A, Okano T. Temperature-responsive cell culture surfaces for regenerative medicine with cell sheet engineering. Prog Polym Sci. 2007;32:1123–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2007.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamada N, Okano T, Sakai H, Karikusa F, Sawasaki Y, Sakurai Y. Thermo-responsive polymeric surfaces; control of attachment and detachment of cultured cells. Makromolekulare Chemie Rapid Comm. 1990;11:571–576. doi: 10.1002/marc.1990.030111109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akahane M, Nakamura A, Ohgushi H, Shigematsu H, Dohi Y, Takakura Y. Osteogenic matrix sheet-cell transplantation using osteoblastic cell sheet resulted in bone formation without scaffold at an ectopic site. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2008;2:196–201. doi: 10.1002/term.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ebihara G, Sato M, Yamato M, Mitani G, Kutsuna T, Nagai T, et al. Cartilage repair in transplanted scaffold-free chondrocyte sheets using a minipig model. Biomaterials. 2012;33:3846–3851. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu D, Wang Z, Wang J, Geng Y, Zhang Z, Li Y, et al. Development of a micro-tissue-mediated injectable bone tissue engineering strategy for large segmental bone defect treatment. Stem Cell Res Therapy. 2018;9:331. doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-1064-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jin CZ, Choi BH, Park SR, Min BH. Cartilage engineering using cell-derived extracellular matrix scaffold in vitro. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010;92:1567–1577. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yasui Y, Ando W, Shimomura K, Koizumi K, Ryota C, Hamamoto S, et al. Scaffold-free, stem cell-based cartilage repair. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2016;7:157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin RL, Park SR, Choi BH, Min BH. Scaffold-free cartilage fabrication system using passaged porcine chondrocytes and basic fibroblast growth factor. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:1887–1895. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Handschel JG, Depprich RA, Kübler NR, Wiesmann HP, Ommerborn M, Meyer U, et al. Prospects of micromass culture technology in tissue engineering. Head Face Med. 2007;3:4. doi: 10.1186/1746-160X-3-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ando W, Tateishi K, Hart DA, Katakai D, Tanaka Y, Nakata K, et al. Cartilage repair using an in vitro generated scaffold-free tissue-engineered construct derived from porcine synovial mesenchymal stem cells. Biomaterials. 2007;28:5462–5470. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schon BS, Hooper GJ, Woodfield TB. Modular tissue assembly strategies for biofabrication of engineered cartilage. Annals Biomed Eng. 2017;45:100–114. doi: 10.1007/s10439-016-1609-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Inagaki Y, Uematsu K, Akahane M, Morita Y, Ogawa M, Ueha T, et al. Osteogenic matrix cell sheet transplantation enhances early tendon graft to bone tunnel healing in rabbits. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:842192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Chen B, Lin H, Wang J, Zhao Y, Wang B, Zhao W, et al. Homogeneous osteogenesis and bone regeneration by demineralized bone matrix loading with collagen-targeting bone morphogenetic protein-2. Biomaterials. 2007;28:1027–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huber E, Pobloth AM, Bormann N, Kolarczik N, Schmidt-Bleek K, Schell H, et al. Demineralized bone matrix as a carrier for bone morphogenetic protein-2: burst release combined with long-term binding and osteoinductive activity evaluated in vitro and in vivo. Tissue Eng Part A. 2017;23:1321–1330. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2017.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shirai M, Yamamoto R, Chiba T, Komatsu K, Shimoda S, Yamakoshi Y, et al. Bone augmentation around a dental implant using demineralized bone sheet containing biologically active substances. Dental Mater J. 2016;35:470–478. doi: 10.4012/dmj.2016-026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaban LB, Mulliken JB, Glowacki J. Treatment of jaw defects with demineralized bone implants. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1982;40:623–626. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(82)90109-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mulliken JB, Glowacki J. Induced osteogenesis for repair and construction in the craniofacial region. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1980;65:553–560. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198005000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi WH, Kim HR, Lee SJ, Jeong N, Park SR, Choi BH, et al. Fetal cartilage-derived cells have stem cell properties and are a highly potent cell source for cartilage regeneration. Cell Transplant. 2016;25:449–461. doi: 10.3727/096368915X688641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park SR, Oh HJ, Truong MD, Kim M, Choi JY, et al. Engineered cartilage utilizing fetal cartilage-derived progenitor cells for cartilage repair. Sci Rep. 2020;10:5722. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-62580-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giannoudis PV, Einhorn TA, Marsh D. Fracture healing: the diamond concept. Injury. 2007;38:S3–S6. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(08)70003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nerem RM, Sambanis A. Tissue engineering: from biology to biological substitutes. Tissue Eng. 1995;1:3–13. doi: 10.1089/ten.1995.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kneser U, Kaufmann PM, Fiegel HC, Pollok JM, Kluth D, Herbst H, et al. Long-term differentiated function of heterotopically transplanted hepatocytes on three-dimensional polymer matrices. J Biomed Mater Res. 1999;47:494–503. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4636(19991215)47:4<494::AID-JBM5>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holy CE, Shoichet MS, Davies JE. Engineering three-dimensional bone tissue in vitro using biodegradable scaffolds: investigating initial cell-seeding density and culture period. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;51:376–382. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(20000905)51:3<376::AID-JBM11>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen G, Qi Y, Niu L, Di T, Zhong J, Fang T, et al. Application of the cell sheet technique in tissue engineering. Biomed Rep. 2015;3:749–757. doi: 10.3892/br.2015.522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pirraco RP, Obokata H, Iwata T, Marques AP, Tsuneda S, Yamato M, et al. Development of osteogenic cell sheets for bone tissue engineering applications. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:1507–1515. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Lise AM, Stringa E, Woodward WA, Mello MA, Tuan RS. Embryonic limb mesenchyme micromass culture as an in vitro model for chondrogenesis and cartilage maturation. Developmental biology protocols. Methods Mol Biol. 2000;137:359–75. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Lundberg JO. Nitrate transport in salivary glands with implications for NO homeostasis. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:13144–13145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210412109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosso F, Giordano A, Barbarisi M, Barbarisi A. From cell–ECM interactions to tissue engineering. J Cell Physiol. 2004;199:174–180. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gerber I, Ap Gwynn I. Differentiation of rat osteoblast-like cells in monolayer and micromass cultures. Eur Cell Mater. 2002;3:19–30. doi: 10.22203/eCM.v003a03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu Y, Kuang B, Rothrauff BB, Tuan RS, Lin H. Robust bone regeneration through endochondral ossification of human mesenchymal stem cells within their own extracellular matrix. Biomaterials. 2019;218:119336. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]