Abstract

Our aim is to selectively deliver 9-(2-phosphonylmethoxyethyl)adenine (PMEA) to parenchymal liver cells, the primary site of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. Selective delivery is necessary because PMEA, which is effective against HBV in vitro, is hardly taken up by the liver in vivo. Lactosylated reconstituted high-density lipoprotein (LacNeoHDL), a lipid particle that is specifically internalized by parenchymal liver cells via the asialoglycoprotein receptor, was used as the carrier. PMEA could be incorporated into the lipid moiety of LacNeoHDL by attaching, via an acid-labile bond, lithocholic acid-3α-oleate to the drug. The uptake of the lipophilic prodrug (PMEA-LO) by the liver was substantially increased after incorporation into LacNeoHDL. Thirty minutes after injection of [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL into rats, the liver contained 68.9% ± 7.7% of the dose (free [3H]PMEA, <5%). Concomitantly, the uptake by the kidney was reduced to <2% of the dose (free [3H]PMEA, >45%). The hepatic uptake of PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL occurred mainly by parenchymal cells (88.5% ± 8.2% of the hepatic uptake). Moreover, asialofetuin inhibited the liver association by >75%, indicating uptake via the asialoglycoprotein receptor. The acid-labile linkage in PMEA-LO, designed to release PMEA during lysosomal processing of the prodrug-loaded carrier, was stable at physiological pH but was hydrolyzed at lysosomal pH (half-life, 60 to 70 min). Finally, subcellular fractionation indicates that the released PMEA is translocated to the cytosol, where it is converted into its active diphosphorylated metabolite. In conclusion, lipophilic modification and incorporation of PMEA into LacNeoHDL improves the biological fate of the drug and may lead to an enhanced therapeutic efficacy against chronic hepatitis B.

Chronic hepatitis B is a serious liver disease caused by an infection of the parenchymal liver cell with the hepatitis B virus (HBV) and may lead to liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (6). Presently, alpha interferon and lamivudine (Epivir-HBV) are the only approved therapeutic agents for chronic hepatitis B. However, alpha interferon is only effective in 30 to 40% of the treated patients and provokes a number of dose-dependent side effects (37). Although lamivudine displays good efficacy in chronically HBV-infected patients (23), emergence of lamivudine resistance has been reported, and this jeopardizes the prospects of long-term treatment (21, 24). Therefore, the development of alternative therapies for chronic hepatitis B remains imperative.

A promising candidate drug is 9-(2-phosphonylmethoxyethyl)adenine (PMEA; adefovir), an acyclic nucleoside phosphonate analog which inhibits the replication of HBV in vitro and in vivo (29, 39). Moreover, recent studies indicate that HBV DNA polymerase mutants that are resistant to lamivudine triphosphate remained sensitive to diphosphorylated PMEA (38). Unfortunately, intravenously injected PMEA accumulates primarily in the kidneys, whereas only a limited amount is taken up by the liver, the primary site of HBV infection (27). Also, the orally bioavailable Bis(POM)-PMEA prodrug is hydrolyzed to free PMEA during transport from the gastrointestinal tract to the circulation and thus has the same unfavorable disposition characteristics as PMEA (2, 15, 34). The high level of uptake of PMEA by the kidneys may result in nephrotoxicity, as has been shown for the related nucleoside phosphonates (S) - 1 - (3 - hydroxy - 2 - phosphonylmethoxypropyl)cytosine [(S)-HPMPC; cidofovir] and (S)-9-(3-hydroxy-2-phosphonylmethoxypropyl)adenine [(S)-HPMPA] (11, 35). Selective delivery of PMEA to parenchymal liver cells may lower the level of renal uptake of the drug and may concomitantly improve its therapeutic efficacy against chronic hepatitis B.

Because of its unique localization and abundant expression on parenchymal liver cells (3), the asialoglycoprotein receptor represents an attractive target for selective delivery of drugs to this cell type. The asialoglycoprotein receptor specifically recognizes ligands with exposed galactose and N-acetylgalactosamine residues (32). The ligands are rapidly internalized and transported to the lysosomal compartment. Reconstituted high-density lipoprotein (NeoHDL), a synthetic particle composed of lipids and isolated high-density lipoprotein (HDL) apoproteins, can be selectively targeted to the asialoglycoprotein receptor by lactosylation of the apoproteins (33). Lactosylated NeoHDL (LacNeoHDL) can accommodate substantial amounts of lipophilic (pro)drugs in its lipid moiety without interfering with the receptor-mediated recognition of the lactosylated apoproteins. This makes LacNeoHDL an attractive carrier for specific delivery of anti-HBV agents to parenchymal liver cells. PMEA is, however, too hydrophilic for incorporation into the lipid moiety of LacNeoHDL and needs to be derivatized with a lipophilic residue to enable incorporation.

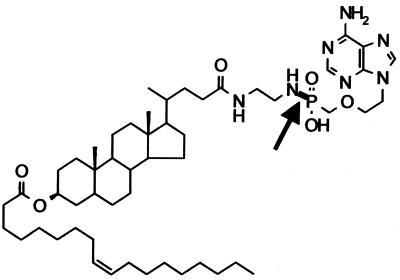

Recently, we synthesized a lipophilic prodrug of PMEA (PMEA-LO) by conjugating the drug with lithocholic acid-3α-oleate using ethylenediamine as a spacer (Fig. 1) (18). The linkage between PMEA and the spacer is acid labile, which ensures the release of PMEA once the prodrug is delivered to the acidic lysosomes in the target cell. PMEA-LO readily incorporates into LacNeoHDL without appreciably affecting the physicochemical properties of the carrier (18). In the present study, we examined in rats whether the lipophilic modification of PMEA and the subsequent incorporation of the prodrug into LacNeoHDL increases the uptake of the drug by parenchymal liver cells and reduces its renal uptake. Furthermore, we determined the intracellular routing and metabolic fate of PMEA-LO in the liver.

FIG. 1.

Structure of PMEA-LO (the acid-labile phosphonamidate bond is indicated by an arrow).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

PMEA and its mono- and diphosphoryl metabolites were synthesized as described in detail earlier (19, 20). [adenine-2,8-3H]PMEA (0.33 Ci/mmol) was purchased from Moravek Biochemicals (Brea, Calif.). The synthesis and purification of PMEA-LO and [3H]PMEA-LO have been described in detail elsewhere (18). Egg yolk phosphatidylcholine (98%) was from Fluka (Buchs, Switzerland). Cholesteryl oleate (97%) was obtained from Janssen (Beersse, Belgium). Bovine serum albumin (fraction V) was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.). Lactosylated HDL apoproteins were prepared as described previously (18). Ketamine (100 mg/ml; HCl salt) was from Eurovet (Bladel, The Netherlands). Hypnorm (0.315 mg of fentanyl citrate per ml and 10 mg of fluanisone per ml) and Thalamonal (0.05 mg of fentanyl per ml and 2.5 mg of droperidol per ml) were from Janssen-Cilag Ltd. (Saunderton, England). Emulsifier Safe, Hionic Fluor, and Monophase S scintillation cocktails were obtained from Packard (Downers Grove, Ill.). Asialofetuin was prepared as described earlier (9). All other reagents were of analytical grade.

Preparation and characterization of [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL.

[3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL was prepared essentially as described earlier for NeoHDL (31). [3H]PMEA-LO (0.5 mg, 10 to 35 dpm/ng) was cosonicated at 49 to 52°C with 3.6 mg of egg yolk phosphatidylcholine and 1.8 mg of cholesteryl oleate. The sonication was stopped after 30 min and the temperature was lowered to 42°C. Sonication was continued for 30 min, and 6 mg of lactosylated HDL apoproteins dissolved in 1 ml of 4 M urea was added in 10 equal portions over the first 10 min. The resulting particles were purified by gel permeation chromatography with a Superose 6 column (1.6 by 50 cm) eluted with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer [pH 7.4] containing 0.15 M NaCl) containing 1 mM EDTA. The prodrug-loaded particles were passed through a Millipore filter (pore size, 0.45 μm) and were stored at 4°C until use. The chemical composition and size of [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL were determined as described in detail earlier (18). Before each experiment with animals, [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL was dialyzed against PBS.

Determination of release of [3H]PMEA from [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL in vitro.

To examine the release of [3H]PMEA under different pH conditions, [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL was dissolved in PBS containing 1 mM EDTA to a concentration of 8 to 30 μg of [3H]PMEA-LO per ml. Aliquots of 82.5 μl were mixed with either 17.5 μl of 0.1 M sodium citrate (pH 4.4; final pH, 4.7) or 17.5 μl of 0.1 M sodium phosphate (pH 7.4). To study the release in plasma, 25 μl of [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL dissolved in PBS containing 1 mM EDTA (26 μg of [3H]PMEA-LO per ml) was mixed with 75 μl of freshly isolated rat plasma. All mixtures were incubated at 37°C, and at the indicated times, 50-μl samples were analyzed by gel permeation chromatography with a SMART system equipped with a Superose 6 PC 3.2/30 column (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden). The column was eluted with PBS containing 0.01% sodium azide at a flow rate of 50 μl/min. Fractions of 100 μl were collected and counted for 3H radioactivity. Particle-associated [3H]PMEA-LO and free [3H]PMEA eluted at 1.2 to 1.7 and 2.0 to 2.4 ml, respectively (18).

Experimental animals.

Male Wistar rats (weight, between 192 and 242 g; Broekman Instituut BV, Someren, The Netherlands) were used. The animals received humane care and were handled in compliance with the guidelines issued by the Dutch authorities. Animals were anesthetized prior to the experiments by subcutaneous injection of a cocktail containing ketamine-HCl, fentanyl, droperidol, and fluanisone (75, 0.04, 1.1, and 0.75 mg/kg of body weight, respectively).

Determination of clearance from plasma and distribution in tissue of [3H]PMEA and [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL.

Rats were anesthetized as described above, and the abdomen was opened. [3H]PMEA (50 μg/kg of body weight) or [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL (10 μg of [3H]PMEA/kg of body weight) was injected via the vena penis or vena cava inferior. At the indicated times, blood samples of 0.2 to 0.3 ml were taken from the vena cava inferior and were collected in heparinized tubes. The samples were centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 2 min, and the plasma was assayed for 3H radioactivity. The total amount of radioactivity in plasma was calculated by using the following equation: plasma volume (in milliliters) = (0.0291 × body weight [in grams]) + 2.54 (8). At the indicated times, liver lobules were tied off and excised. At the end of the experiment, the remainder of the liver and some other tissues were removed. The amount of liver tissue tied off successively did not exceed 15% of the total liver mass. The radioactivity in the liver at each time point was calculated from the radioactivities and weights of the liver samples. The radioactivities in liver and other tissues were corrected for the radioactivity in plasma present in the tissue at the time of sampling (12).

Determination of distribution of [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL over liver cells.

Rats were anesthetized and injected with [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL (20 μg of [3H]PMEA/kg of body weight) as described above. The liver was perfused at 60 min after injection, and parenchymal, Kupffer, and endothelial cells were isolated from the liver as described in detail earlier (28). Before separation of the cells, a liver lobule was tied off and was excised to determine the total uptake by the liver. The contributions of the various liver cell types to the total hepatic uptake were calculated as described previously (28).

Determination of the intracellular fate of [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL.

Rats were anesthetized and injected with [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL (15 μg of [3H]PMEA/kg of body weight) as described above. Five hours later, the rats were anesthetized again, and the liver was perfused with ice-cold 0.25 M sucrose containing 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4). A liver lobule was tied off, excised, and homogenized in cold (−80°C) methanol. The homogenate was subsequently centrifuged at 16,000 × g, filtered (pore size, 0.45 μm), and injected in a high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) system equipped with a Partisil 10 SAX column (250 by 4.6 mm). After injection of the sample, the column was washed for 10 min with 10 mM NH4H2PO4 (pH 3.5), followed by a linear gradient of 10 to 1,000 mM NH4H2PO4 (pH 3.5) (20 min). Finally, the column was isocratically eluted for 10 min with 1,000 mM NH4H2PO4 (pH 3.5; flow rate, 1 ml/min). Fractions of 1 ml were collected and assayed for radioactivity. PMEA, monophosphorylated PMEA (PMEAp), and diphosphorylated PMEA (PMEApp) were used as standards (these compounds eluted at 11.0, 26.0, and 35.2 min, respectively). The remainder of the liver was divided into subcellular fractions as described previously (17). In brief, the liver was dispersed in two volumes of sucrose–Tris-HCl buffer (see above) by using a homogenizer of the Potter-Elvehjem type. Fractions enriched in nuclei, mitochondria, lysosomes, and microsomes were obtained by collecting pellets obtained after subjecting the homogenate to consecutive centrifugation steps of 5 min at 1,200 × g, 5 min at 6,300 × g, 15 min at 17,600 × g, and 30 min at 210,000 × g, respectively. The final supernatant was the cytosol fraction. The fractions were assayed for radioactivity, protein, and the activities of marker enzymes as described in detail earlier (17).

Determination of protein concentrations.

The protein concentrations in the cell suspensions and subcellular fractions were determined by the method of Lowry et al. (25) by using bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Determination of radioactivity.

The radioactivity in all samples was counted in a Packard Tri-Carb 1500 liquid scintillation counter (Packard). The radioactivities in samples obtained by chromatography with the SMART system and HPLC and plasma samples were counted directly in Emulsifier Safe or Hionic Fluor. Tissue samples were processed with a Packard Tri-Carb 306 sample oxidizer, and the radioactivity in tissue samples was subsequently counted in Monophase S. Samples of cell suspensions and subcellular fractions were first digested with 10 M NaOH, and the radioactivity was then counted in Hionic Fluor.

RESULTS

Preparation and characterization of [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL.

[3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL was prepared by an established method for the preparation of (prodrug-loaded) NeoHDL (31, 33). In brief, [3H]PMEA-LO was cosonicated with egg yolk phosphatidylcholine, cholesteryl oleate, and lactosylated HDL apoproteins, and the resulting particles were purified by gel permeation chromatography. The chemical composition of the prodrug-loaded carrier is given in Table 1. The particles contained a substantial amount of PMEA-LO: 2.6% ± 0.3% of the total weight (approximately 5% of the lipid moiety). The mean diameter of the particles, as determined by gel permeation chromatography, was 11.0 ± 0.3 nm (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM] for four preparations). From its composition and size and assuming an HDL-like density (1.137 g/ml), it can be calculated that each particle contains approximately 13 lipophilic PMEA prodrug molecules.

TABLE 1.

Chemical composition of [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDLa

| Component | Composition (% [wt/wt]) |

|---|---|

| Protein | 35.5 ± 4.1 |

| Egg yolk phosphatidylcholine | 33.7 ± 2.7 |

| Cholesteryl oleate | 16.0 ± 0.9 |

| Lactose | 12.1 ± 1.1 |

| [3H]PMEA-LO | 2.6 ± 0.3 |

The chemical composition of [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL was determined as described previously (18). Values are expressed as the means ± SEMs for four different preparations.

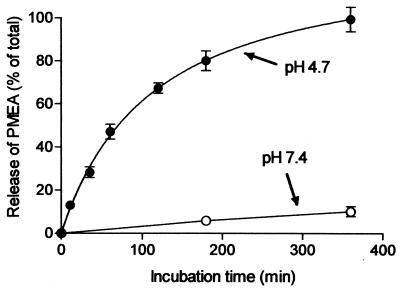

Acid-induced release of [3H]PMEA from [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL.

To become pharmacologically active, it is crucial that PMEA is released from the prodrug-loaded carrier. We therefore chose to include a phosphonamidate bond in the PMEA prodrug (Fig. 1). The bond is acid labile and should trigger the release of PMEA once the complex is exposed to the acidic environment of the lysosomes. The release of [3H]PMEA from the prodrug-loaded carrier was studied by incubating [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL at 37°C at pH 4.7, the ambient pH in the lysosomal compartment (26), and at pH 7.4, the pH in the circulation. The released [3H]PMEA was separated from the prodrug-loaded carrier by subjecting the samples to gel permeation chromatography. Figure 2 shows that [3H]PMEA was rapidly released from the NeoHDL carrier when it was incubated at pH 4.7. After 6 h of incubation, the release of [3H]PMEA from the prodrug-loaded carrier was almost complete. In contrast, no appreciable release of [3H]PMEA was observed when the prodrug-loaded carrier was incubated at pH 7.4, even after 6 h at 37°C. Moreover, when the complex was incubated for 3 h at 37°C in rat plasma, only 5.0% ± 0.6% (mean ± SEM; n = 3) of the [3H]PMEA was released. These findings indicate that PMEA will remain associated with LacNeoHDL within the circulation but will be rapidly released from the prodrug-loaded carrier during lysosomal processing.

FIG. 2.

Release of [3H]PMEA from [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL at lysosomal pH. [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL was incubated at pH 4.7 (●) and 7.4 (○) at 37°C. At the indicated times, samples were chromatographically analyzed for released [3H]PMEA as described in Materials and Methods. The amounts of [3H]PMEA released are expressed as a percentage of the total radioactivity analyzed. Values are means ± SEMs for three individual experiments.

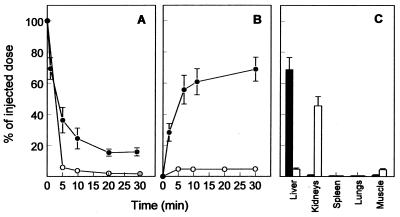

Clearance from plasma and distribution in tissue of [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL and [3H]PMEA.

The effect of the lipophilic modification of PMEA and the subsequent incorporation of PMEA-LO into LacNeoHDL on the biological fate of the drug was determined in rats. In Fig. 3, the clearance from plasma and distribution in tissue of [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL is compared to that of [3H]PMEA. After intravenous injection of [3H]PMEA, radioactivity was extremely rapidly cleared from the circulation (>90% of the dose was cleared in 10 min). The LacNeoHDL-associated 3H-labeled prodrug was also rapidly cleared after intravenous injection, albeit at a slightly lower rate (>75% of the dose was cleared in 10 min). The uptake of the drug by the liver, however, was increased substantially after lipophilic modification and incorporation into LacNeoHDL. Thirty minutes after injection of [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL, approximately 70% of the injected dose was found to be associated with the liver, whereas <5% of the injected radiolabeled free drug was recovered in the liver. This increase in liver association was accompanied by an almost complete reduction of uptake by the kidneys. Less than 2% of the injected dose of the LacNeoHDL- associated [3H]-prodrug was recovered in the kidneys, whereas >45% of free [3H]PMEA was recovered in the kidneys. When the concentrations (in nanograms per gram [fresh weight]) in the liver and kidneys are compared, ratios of the amounts of free PMEA and carrier-associated PMEA in the liver to those in the kidneys (liver/kidney ratio) can be calculated (0.02 and 10), respectively.

FIG. 3.

Clearance from plasma and distribution in tissue of [3H]PMEA and [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL. Rats were intravenously injected with [3H]PMEA (50 μg/kg of body weight; open circles and open bars) or [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL (10 μg of [3H]PMEA/kg of body weight; closed circles and closed bars). At the indicated times, the amounts of radioactivity in plasma (A) and liver (B) were determined. At 30 min ([3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL) or 40 min ([3H]PMEA) after injection, the amount of radioactivity in the indicated tissues (C) was determined. Values represent means ± SEMs for three rats.

Liver cell distribution of [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL.

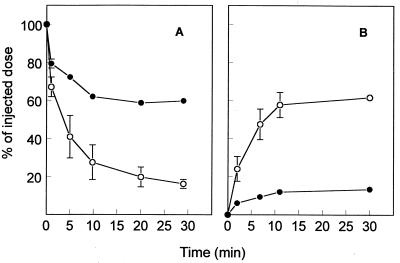

To determine which liver cell type is responsible for the hepatic accumulation of LacNeoHDL-associated PMEA-LO, rats were injected with [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL, and 1 h later the liver cell distribution was determined. Parenchymal liver cells accounted for 88.5% ± 8.2% of the total liver uptake, whereas only 10.2% ± 8.2% and 1.3% ± 0.1% could be attributed to Kupffer cells and endothelial cells, respectively (means ± individual variations for two rats). To ascertain that the asialoglycoprotein receptor is responsible for the uptake by parenchymal liver cells, asialofetuin was used as a specific competitor (36). Preinjection with asialofetuin almost completely inhibited uptake of [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL by the liver (Fig. 4B). Thirty minutes after injection, <15% of the injected dose could be recovered in the liver, whereas >60% could be recovered after preinjection with PBS. The inhibition was accompanied by a substantial increase in the level of radioactivity in plasma (Fig. 4A). The levels of uptake by other tissues, such as the kidneys, lungs, and spleen, remained unaltered (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Effect of asialofetuin on the clearance from plasma and liver association of [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL. Rats were intravenously injected with [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL (10 μg of [3H]PMEA/kg of body weight). One minute prior to injection of the radiolabeled ligand, the animals received asialofetuin (50 mg/kg of body weight; ●) or PBS (○) by intravenous injection. At the indicated times, the amounts of radioactivity in plasma (A) and liver (B) were determined. Values represent means ± SEMs for three rats.

Intracellular fate of [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL.

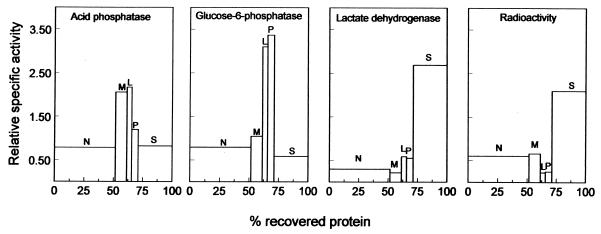

PMEA can exert its therapeutic activity against HBV only when it is delivered to the cytosol, where it can be converted to the active diphosphorylated form. To assess the potential therapeutic effectiveness of LacNeoHDL-associated PMEA-LO, it is therefore essential to monitor the intracellular fate of the prodrug in the liver. To this end, rats were injected with [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL. Five hours later (when 51% of the dose is in the liver), a liver lobule was removed for metabolite analysis (see below), and the remainder of the liver was perfused and subsequently subjected to a subcellular fractionation (17). Figure 5 shows the distribution patterns of the radioactivity and marker enzymes. The distribution pattern of the radioactivity strongly resembles that of the cytosolic marker lactate dehydrogenase, whereas the lysosomal marker acid phosphatase and the microsomal marker glucose-6-phosphatase show clearly different distributions. This finding indicates that [3H]PMEA (metabolites) are localized in the cytosol. The subcellular distribution of the radiolabeled PMEA (metabolites) remained unchanged for up to 24 h after injection (when 4% of the dose is in the liver).

FIG. 5.

Distribution patterns of radioactivity and marker enzymes over subcellular fractions of the liver after injection of [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL. Rats were intravenously injected with [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL (15 μg of [3H]PMEA/kg of body weight). Five hours later, the liver was perfused with ice-cold 0.25 M sucrose containing 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) and was divided into subcellular fractions by differential centrifugation, as described earlier (17). The fractions were assayed for radioactivity, protein content, and the activities of marker enzymes; recoveries were >85%. Blocks from left to right represent nuclear (N), mitochondrial (M), lysosomal (L), microsomal (P), and cytosolic (S) fractions. The relative protein concentration is given on the x axis. The y axis represents the relative specific activity (percentage of total activity recovered divided by percentage of total protein recovered).

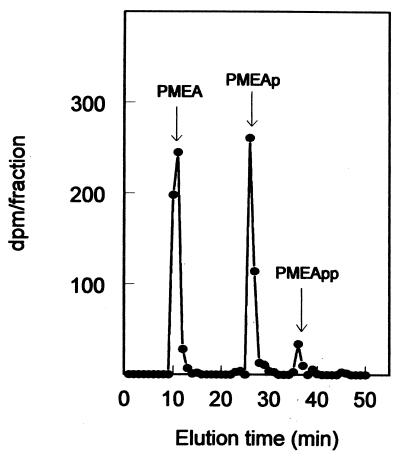

To verify the identities of the radiolabeled compounds in the cytosol, the liver lobule taken before the liver perfusion was extracted and analyzed by anion-exchange chromatography for the presence of [3H]PMEA (metabolites). The HPLC chromatogram, given in Fig. 6, shows the presence of two major metabolites and the minor metabolite concurred with those of PMEA, PMEAp, and PMEApp, respectively. Thus, our results indicate that, as required, targeting of the PMEA prodrug to the liver leads to the appearance of its pharmacologically active metabolite in the cytosol.

FIG. 6.

Anion-exchange chromatographic analysis of the radioactivity in a liver extract after injection of [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL. Five hours after intravenous injection of [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL (15 μg of [3H]PMEA/kg of body weight) into rats, a liver lobule was homogenized in cold (−80°C) methanol. The homogenate was centrifuged, filtered, and analyzed by anion-exchange HPLC as described in Materials and Methods. Fractions of 1 ml were collected and assayed for radioactivity. The elution times of unlabeled PMEA, PMEAp, and PMEApp standards are indicated by arrows.

DISCUSSION

Recently, we synthesized an acid-labile lipophilic conjugate of lithocholic acid-3α-oleate and PMEA using ethylenediamine as the spacer (18). The prodrug, designated PMEA-LO, readily associated with LacNeoHDL without appreciably affecting the physicochemical properties of the particle. LacNeoHDL is a lipid particle that is specifically taken up by parenchymal liver cells via the asialoglycoprotein receptor (33), and it was designed as a carrier for the selective delivery of lipophilic (pro)drugs to these cells. In the present study, we characterized the biological fate of LacNeoHDL-associated PMEA-LO in rats.

In agreement with a previous study (27), free [3H]PMEA was hardly taken up by the liver and was primarily found to be associated with the kidneys. The liver/kidney ratio, calculated from the concentrations of PMEA in tissue, was 0.02. Chemical modification of PMEA and subsequent association with LacNeoHDL markedly altered the distribution of the drug in tissue. Most of the administered dose (approximately 70%) was found to be associated with the liver, whereas <2% was recovered in the kidneys. The liver/kidney ratio, calculated from the concentrations of the carrier-associated prodrug in tissue, was 10. This value is 500 times greater than that found after injection of free PMEA. Besides the asialoglycoprotein receptor on parenchymal liver cells, Kupffer cells also express a galactose-recognizing receptor which may be involved in the enhanced uptake of PMEA by the liver (22). Analysis of the contributions of the various liver cell types to the hepatic uptake showed that PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL is primarily taken up by parenchymal liver cells. The involvement of the parenchymal liver cells was further confirmed by using asialofetuin, a substrate specific for the asialoglycoprotein receptor (36), as a competitor. Preinjection with asialofetuin almost completely blocked the uptake of PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL by the liver, indicating that the asialoglycoprotein receptor is involved in the uptake. The preferential uptake of PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL by parenchymal liver cells can be explained by the size-dependent recognition characteristics of the galactose particle receptor on Kupffer cells (7). Only galactose-exposing particles larger than 15 nm display a sufficiently high affinity toward the receptor. Apparently, [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL (size, approximately 11 nm) is sufficiently small to circumvent uptake by Kupffer cells.

As the proper intracellular processing of the LacNeoHDL-associated PMEA-LO is crucial for provoking a therapeutic effect, we studied the intracellular fate of the prodrug. Binding of a ligand, like PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL, to the asialoglycoprotein receptor is coupled to transport to the lysosomes. The phosphonamidate bond in PMEA-LO was designed to be stable at neutral pH and to be hydrolyzed at acidic pH. Indeed, PMEA remained associated with its carrier during in vitro incubation of PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL at pH 7.4 and in rat plasma. This ensures that the complete drug-carrier complex remains available for uptake during circulation. In contrast, at pH 4.7 (the ambient pH in lysosomes [26]) a rapid hydrolysis was found, indicating that in the lysosomal compartment PMEA will be rapidly released from the carrier. The released PMEA, a negatively charged molecule, must cross the lysosomal membrane to reach the cytosol, the intracellular site of HBV replication. The subcellular fractionation experiment indicates that at 5 h after injection of [3H]PMEA-LO-loaded LacNeoHDL, the radioactivity (that of PMEA and its metabolites) was primarily located in the cytosol. This result demonstrates that PMEA is able to cross the lysosomal membrane. The exact mechanism is not entirely understood, but a likely mechanism may be simple passive diffusion of uncharged PMEA, present in minor amounts (∼0.2%) in the lysosomal compartment. Once in the cytosol (pH 7.4), the translocated PMEA is rapidly deprotonated and the existing concentration gradient between lysosomes and cytosol is maintained. A similar explanation was recently proposed for the lysosomal release of (S)-HPMPC in Vero cells (14). Alternative mechanisms for transport across the lysosomal membrane may involve facilitated or active transport. Cihlar et al. (13) reported that transport of PMEA across the plasma membrane in HeLa S3 cells is protein mediated, and Balzarini et al. (5) also found evidence for a PMEA transport molecule on murine leukemia L1210 cells. Moreover, it was found that the renal and hepatic uptake of (S)-HPMPA and the renal uptake of (S)-HPMPC proceed via a probenicid-sensitive anion transporter present in the plasma membrane (10, 16). However, thus far no reports have suggested the presence of lysosomal anion-nucleotide transporters. Recently, the existence of a nucleoside transport system in the lysosomal membrane has been described (30). However, involvement of this system in PMEA transport seems unlikely, because nucleotides were reported to be unable to inhibit the nucleoside transport.

To exert its anti-HBV activity, cytosolic PMEA must be phosphorylated to its diphosphate metabolite. At 5 h after injection, we could indeed identify the diphosphorylated (PMEApp) metabolite in the liver extract, in addition to PMEA and monophosphorylated PMEA (PMEAp). This finding indicates that phosphorylation of PMEA to its metabolites does take place in parenchymal liver cells. The small amount of PMEApp is in accordance with results reported by Naesens et al. (27). At 60 min after injection, those investigators could detect only small amounts of PMEAp (<10% of the total amount of PMEA) and could not detect any PMEApp in kidney and liver extracts. The findings of Naesens et al. (27) and ourselves suggest that phosphorylation occurs at a relatively low rate. The small amounts of the phosphorylated PMEA metabolites recovered may, on the other hand, reflect the experimental limitations. We observed that during the processing of tissue samples the phosphorylated PMEA metabolites are rapidly dephosphorylated and that extreme care must be taken to attenuate dephosphorylation. Therefore, the recovered amounts of PMEAp and PMEApp may be (much) lower than the amounts actually present in the tissues, which leads to underestimation of the degree of phosphorylation to the active metabolite.

The intracellular half-life of PMEA (and its metabolites) in the parenchymal liver cell is, on the basis of the association with the liver at 30 min, 5 h, and 24 h, estimated to be 5 to 6 h. This value is in good agreement with the reported half-life of approximately 5 h for PMEA, PMEAp, and PMEApp in Vero cells (1), although a longer half-life (16 to 18 h) has also been reported for PMEApp in MT4 cells (4).

We calculated from our data a cytosolic concentration of total PMEA (including metabolites) of approximately 2 μM at 5 h after injection. Even higher levels should easily be reached by higher and/or more frequent dosing. Using a quantitative human HBV DNA polymerase assay, Xiong et al. (38) calculated an inhibition constant (Ki) value for PMEApp of 0.1 μM. The cytosolic levels of PMEA and its metabolites that can be attained by our carrier-mediated approach should therefore be sufficiently high to inhibit HBV replication.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that lipophilic modification of PMEA and its subsequent incorporation into LacNeoHDL results in a dramatically increased uptake of the drug by parenchymal liver cells. The kidney association of the drug is substantially reduced. After transport to the lysosomes, PMEA is rapidly released from the carrier and readily enters the cytosol, where the drug is phosphorylated to the active metabolite PMEApp. The dramatically improved biological fate of PMEA holds great promise that the present carrier-mediated approach may lead to a more effective therapy for chronic hepatitis B.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grant 902-21-150 from the Dutch Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) and grant 349-3363 from the Foundation of Technical Sciences (STW).

REFERENCES

- 1.Aduma P, Connelly M C, Srinivas R V, Fridland A. Metabolic diversity and antiviral activities of acyclic nucleoside phosphonates. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;47:816–822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Annaert P, Van Gelder J, Naesens L, De Clercq E, Van den Mooter G, Kinget R, Augustijns P. Carrier mechanisms involved in the transepithelial transport of bis(POM)-PMEA and its metabolites across Caco-2 monolayers. Pharm Res. 1998;15:1168–1173. doi: 10.1023/a:1011923420719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashwell G, Harford J. Carbohydrate-specific receptors of the liver. Ann Rev Biochem. 1982;51:531–554. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.51.070182.002531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balzarini J, Hao Z, Herdewijn P, Johns D G, De Clercq E. Intracellular metabolism and mechanism of anti-retrovirus action of 9-(2-phosphonylmethoxyethyl)adenine, a potent anti-human immunodeficiency virus compound. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:1499–1503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.4.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balzarini J, Hatse S, Naesens L, De Clercq E. Selection and characterization of murine leukemia L1210 cells with high-level resistance to the cytostatic activity of the acyclic nucleoside phosphonate 9-(2-phosphonylmethoxyethyl)adenine (PMEA) Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1402:29–38. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(97)00143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beasley R P. Hepatitis B virus. The major etiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 1988;61:1942–1956. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19880515)61:10<1942::aid-cncr2820611003>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biessen E A, Bakkeren H F, Beuting D M, Kuiper J, Van Berkel T J. Ligand size is a major determinant of high-affinity binding of fucose- and galactose-exposing (lipo)proteins by the hepatic fucose receptor. Biochem J. 1994;299:291–296. doi: 10.1042/bj2990291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bijsterbosch M K, Duursma A M, Bouma J M, Gruber M. The plasma volume of the Wistar rat in relation to the body weight. Experientia. 1981;37:381–382. doi: 10.1007/BF01959874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bijsterbosch M K, Van Berkel T J. Lactosylated high density lipoprotein: a potential carrier for the site-specific delivery of drugs to parenchymal liver cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1991;41:404–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bijsterbosch M K, Smeijsters L J, Van Berkel T J. Disposition of the acyclic nucleoside phosphonate (S)-9-(3-hydroxy-2-phosphonylmethoxypropyl)adenine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1146–1150. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.5.1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bischofberger N, Hitchcock M J, Chen M S, Barkhimer D B, Cundy K C, Kent K M, Lacy S A, Lee W A, Li Z H, Mendel D B, Smee D F, Smith J L. 1-[((S)-2-Hydroxy-2-oxo-1,4,2-dioxaphosphorinan-5-yl)methyl] cytosine, an intracellular prodrug for (S)-1-(3-hydroxy-2-phosphonylmethoxypropyl)cytosine with improved therapeutic index in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2387–2391. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.10.2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caster W O, Simon A B, Armstrong W D. Evans Blue space in tissues of the rat. Am J Physiol. 1955;183:317–321. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1955.183.2.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cihlar T, Rosenberg I, Votruba I, Holy A. Transport of 9-(2-phosphonomethoxyethyl)adenine across plasma membrane of HeLa S3 cells is protein mediated. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:117–124. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.1.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Connelly M C, Robbins B L, Fridland A. Mechanism of uptake of the phosphonate analog (S)-1-(3-hydroxy-2-phosphonylmethoxypropyl)cytosine (HPMPC) in Vero cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 1993;46:1053–1057. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90670-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cundy K C, Fishback J A, Shaw J-P, Lee M L, Soike K F, Visor G C, Lee W A. Oral bioavailability of the antiretroviral agent 9-(2-phosphonylmethoxyethyl)adenine (PMEA) from three formulations of prodrug Bis(pivaloyloxymethyl)-PMEA in fasted male cynomolgus monkeys. Pharm Res. 1994;11:839–843. doi: 10.1023/a:1018925723889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cundy K C, Petty B G, Flaherty J, Fisher P E, Polis M A, Wachsman M, Lietman P S, Lalezari J P, Hitchcock M J, Jaffe H S. Clinical pharmacokinetics of cidofovir in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1247–1252. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.6.1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Duve C, Pressman B C, Gianetto R, Wattiaux R, Appelmans F. Tissue fractionation studies. 6. Intracellular distribution patterns of enzymes in rat liver tissue. Biochem J. 1955;60:604–617. doi: 10.1042/bj0600604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Vrueh R L, Rump E T, Sliedregt L A, Biessen E A, Van Berkel T J, Bijsterbosch M K. Synthesis of a lipophilic prodrug of 9-(2-phosphonylmethoxyethyl)adenine (PMEA) and its incorporation into a hepatocyte-specific lipidic carrier. Pharm Res. 1999;16:1179–1185. doi: 10.1023/a:1018933126885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoard D E, Ott D G. Conversion of mono and oligodeoxyribonucleotides to 5′-triphosphates. J Am Chem Soc. 1965;87:1785–1788. doi: 10.1021/ja01086a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holy A, Rosenberg I. Synthesis of 9-(2-phosphonylmethoxyethyl)adenine and related compounds. Collect Czech Chem Commun. 1987;52:2801–2809. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Honkoop P, Niesters H G, De Man R A, Osterhaus A D, Schalm S W. Lamivudine resistance in immunocompetent chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 1997;26:1393–1395. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(97)80476-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kolb-Bachofen V, Schlepper-schafer J, Vogell W, Kolb H. Electronmicroscopic evidence for a asialoglycoprotein receptor on Kupffer cells: localization of lectin-mediated endocytosis. Cell. 1982;29:859–866. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90447-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lai C L, Ching C K, Tung K M, Li E, Young J, Hill A, Wong C Y, Dent J, Wu P C. Lamivudine is effective in surpressing hepatitis B virus DNA in Chinese hepatitis B surface antigen carriers: a placebo-controlled trial. Hepatology. 1997;25:241–244. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ling R, Multimer D, Ahmed M, Boxall E H, Elias E, Dusheiko G M, Harrison T J. Selection of mutations in the hepatitis B virus polymerase during therapy of transplant recipients with lamivudine. Hepatology. 1996;24:711–713. doi: 10.1002/hep.510240339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lowry O H, Rosebrough N J, Farr A L, Randall R J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Myers B M, Tietz P S, Tarara J E, LaRusso N F. Dynamic measurements of the acute and chronic effects of lysosomotropic agents on hepatocyte lysosomal pH using flow cytometry. Hepatology. 1995;22:1519–1526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naesens L, Balzarini J, De Clercq E. Pharmacokinetics in mice of the anti-retrovirus agent 9-(2-phosphonylmethoxyethyl)adenine. Drug Metab Dispos. 1992;20:747–752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagelkerke J F, Barto K P, Van Berkel T J. In vivo and in vitro uptake and degradation of acetylated low density lipoprotein by rat liver endothelial, Kupffer and parenchymal liver cells. J Biol Chem. 1983;263:12221–12227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nicoll A J, Colledge D L, Toole J J, Angus P W, Smallwood R A, Locarnini S A. Inhibition of duck hepatitis B virus replication by 9-(2-phosphonylmethoxyethyl)adenine, an acyclic phosphonate nucleoside analogue. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:3130–3135. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.12.3130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pisoni R L, Thoene J G. Detection and characterization of a nucleoside transport system in human fibroblast lysosomes. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:4850–4856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pittman R C, Glass C K, Atkinson D, Small D M. Synthetic high density lipoprotein particles. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:2435–2442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rensen P C, De Vrueh R L, Van Berkel T J. Targeting hepatitis B therapy to the liver: clinical pharmacokinetic considerations. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1996;31:131–155. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199631020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schouten D, van der Kooij M, Muller J, Pieters M N, Bijsterbosch M K, Van Berkel T J. Development of lipoprotein-like lipid particles for drug targeting: neo-high density lipoproteins. Mol Pharmacol. 1993;44:486–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shaw J-P, Louie M S, Krishnamurthy V V, Arimilli M N, Jones R J, Bidgood A M, Lee W A, Cundy K C. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of selected prodrugs of PMEA in rats. Drug Metab Dispos. 1997;25:362–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smeijsters L J, Nieuwenhuijs H, Hermsen R C, Dorrestein G M, Franssen F F, Overdulve J P. Antimalarial and toxic effects of the acyclic nucleoside phosphonate (S)-9-(3-hydroxy-2-phosphonylmethoxypropyl)adenine in Plasmodium berghei-infected mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1584–1588. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.7.1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Berkel T J, Dekker C J, Kruijt J K, Van Eijk H G. The interaction in vivo of transferrin and asialotransferrin with liver cells. Biochem J. 1987;243:715–722. doi: 10.1042/bj2430715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong D K, Cheung A M, O'Rourke K, Naylor C D, Detsky A S, Heathcote J. Effect of alpha-interferon treatment in patients with hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:312–323. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-4-199308150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xiong X, Flores C, Toole J J, Gibbs C S. Mutations in hepatitis B DNA polymerase associated with resistance to lamivudine do not confer resistance to adefovir in vitro. Hepatology. 1998;28:1669–1673. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yokota T, Mochizuki S, Konno K, Mori S, Shigeta S, De Clercq E. Inhibitory effects of selected antiviral compounds on human hepatitis B virus DNA synthesis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:394–397. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.2.394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]