Abstract

Introduction:

Proper positioning and attachment play a key role in exclusive breastfeeding. Whereas incorrect breastfeeding techniques lead to poor milk transfer and early discontinuation of breastfeeding.

Objectives:

1. To assess the breastfeeding techniques among postnatal mothers and to identify the factors associated with improper positioning and poor attachment. 2. To prioritize the action points to improve the poor breastfeeding practices according to the viewpoint of the staff nurses.

Materials and Methods:

A hospital-based mixed-methods study was carried out in Puducherry for 6 months. In quantitative phase, 99 postnatal mothers were interviewed consecutively and breastfeeding techniques were observed based on Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative and Integrated Management of Neonatal and Childhood Illness guidelines. In qualitative phase, 45 staff nurses ranked the action points to improve the poor breastfeeding practices. Bivariate and multivariate analyses were employed. Mean rank and Kendalls' Concordance Coefficient were calculated for the ranked data.

Results:

About 28.3% and 27.3% of mothers demonstrated improper positioning and poor attachment, respectively. Young mothers, housewives, <10 days old infants, and failure to receive breastfeeding counseling were associated with poor breastfeeding techniques. Poster displays, healthcare workers' training, targeted counseling, and assistance were the priority action points suggested by the staff nurses.

Conclusion:

Maternal age, maternal occupation, infants' age, and breastfeeding counseling influenced breastfeeding techniques. The prioritized action points need to be implemented to achieve the level of Baby Friendly Hospital.

Keywords: Attachment, breastfeeding, positioning, postnatal, practices

INTRODUCTION

Positioning is a technique in which ”the infant is held in relation to the mothers' body” whereas attachment refers to “whether the infant has enough areola and breast tissue in the mouth.”[1] Proper positioning and good attachment play a significant role in initiating and sustaining exclusive breastfeeding.[2,3] On the other hand, improper breastfeeding techniques contribute to poor milk transfer and nutritional deficiencies in infants.[4] Even though breastfeeding practice is almost universal among Indian mothers, incorrect techniques often lead to early discontinuation of breastfeeding and resorting to formula feeding.[5] Hence, it was recommended to assess the problems in breastfeeding and render appropriate counseling on positioning and attachment.[6]

Previous studies had shown that young mothers with no formal education, primigravidas, and those hailing from a nuclear family required more lactation support in the early postnatal period.[7,8] Nowadays, as there are more number of institutional deliveries,[9] the healthcare professionals should take this opportunity to assess and educate mothers about the breastfeeding techniques at the point of discharge. Henceforth, the current study was put forward with the following objectives.

Objectives

To assess the breastfeeding techniques among postnatal mothers and to identify the factors associated with improper positioning and poor attachment

To prioritize the action points to improve the poor breastfeeding practices according to the viewpoint of the staff nurses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

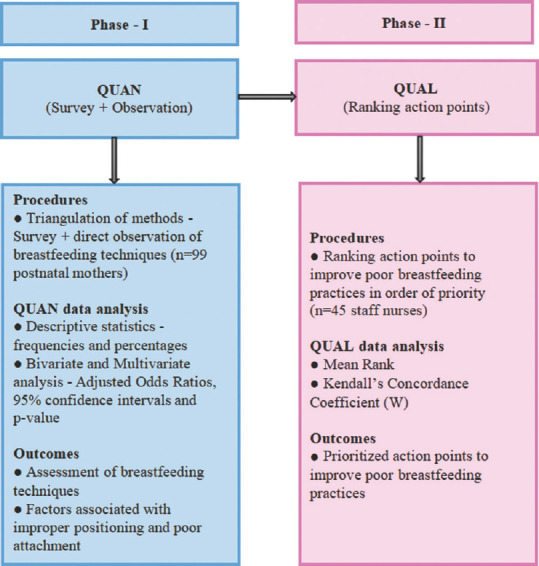

This hospital-based study was undertaken in the postnatal ward and pediatric outpatient department (OPD) in a tertiary-care hospital in Puducherry. A sequential mixed methods design[10] was employed where the quantitative component (survey + observation) was used to assess the breastfeeding techniques and the qualitative component (ranking) was used to prioritize the action points to improve poor breastfeeding practices [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Visual diagram showing sequential mixed methods study design

After obtaining approval from the Research Committee and Institutional Ethics Committee (Approval number: 108/2019), we executed this study for 6 months (January 2020 to June 2020).

Phase I: (Survey + Observation)

Considering 10% of the mothers failed to maintain proper breastfeeding techniques,[11] sample size was calculated as 82 using Open_Epi 3.01 software (AG Dean, KM Sullivan, MM Soe. Open Source Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health; Atlanta, GA, USA) with 6.5% absolute precision and 95% confidence interval. Assuming nonresponse in 15–17 mothers, the final sample size was 99. All postnatal mothers and their infants were included consecutively till the sample size was achieved.

A structured questionnaire was developed based on previous literature and Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) guidelines.[12] The checklist for direct observation of positioning and attachment was based on the Integrated Management of Neonatal and Childhood Illness (IMNCI) guidelines.[6] The questionnaire was checked by the guide, co-guide, and medical social workers for the suitability of the content in capturing the objectives.

After obtaining an informed consent, a single trained female investigator interviewed the mothers after ward rounds and observed the breastfeeding techniques ensuring adequate privacy and following COVID-19 appropriate behaviors. Each of the observation components was given a score of zero or one. An overall score of one to three indicated improper positioning/poor attachment and an overall score of four denoted proper positioning/good attachment.

The data were entered into Epi_Info 7.1.5.0 software (Centre for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, Georgia, US) and analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences 24 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). Bivariate and multivariate analyses[13,14] were used to determine the factors associated with poor breastfeeding techniques. The multiple coefficient of determination (R2) was employed as the goodness-of-fit statistic for the model and statistical significance was fixed at 5% (P < 0.05).

Phase II: (Ranking action points)

Based on the multivariate analysis findings and previous literature, we devised a questionnaire containing 12 action points to improve the poor breastfeeding practices. After obtaining an informed consent, we self-administered the questionnaire to all 45 staff nurses in obstetrics (n = 26) and pediatrics (n = 19) department and asked them to rank in order of their priority without any restriction.

The ranked data were analyzed in SPSS software (version 24). Mean rank was determined for each action point and the overall agreement in the ranking was calculated using Kendalls' Concordance Coefficient (W).[15]

RESULTS

Among 99 postnatal mothers who were currently breastfeeding, the mean age of the mothers was 28.1 ± 5.6 (standard deviation) years. Nearly 57 (57.6%) mothers were homemakers and 94 (94.9%) mothers received formal education. About 64 (64.6%) mothers inhabited urban areas and 65 (65.7%) mothers were from the above poverty line. Almost 57 (57.6%) mothers were multigravidas and 67 (67.7%) mothers had normal vaginal deliveries. Majority 68 (68.7%) infants were <10 days old. Less than half 46 (46.5%) mothers made four or more visits to the healthcare facility and during their visits, 57 (57.6%) mothers received breastfeeding counseling. Interestingly, 67 (67.7%) mothers possessed adequate knowledge on breastfeeding.

Table 1 shows that overall 28 (28.3%) mothers maintained improper positioning and 27 (27.3%) infants had poor attachment. In positioning, 28 (28.3%) infants' head and body were poorly supported and 27 (27.3%) mothers' maintained minimum skin-to-skin contact with their infants. While, in attachment, 27 (27.3%) infants' chin were not touching their mothers' breast and 23 (23.2%) mothers were observed to be having less area of areola visible above the infants' mouth.

Table 1.

Assessment of direct observation of breastfeeding techniques among postnatal mothers (n=99)

| Direct observation of breastfeeding techniques | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Improper positioning maintained while breastfeeding | 28 (28.3) |

| Infant did not turn towards the mother | 2 (2.0) |

| Infant’s nose close to the mother’s body | 24 (24.2) |

| No/minimum skin to skin contact with infant while feeding | 27 (27.3) |

| Infant’s head and body poorly supported | 28 (28.3) |

| Poor attachment while breastfeeding | 27 (27.3) |

| Mouth not wide open | 14 (14.1) |

| Lower lip turned inwards | 14 (14.1) |

| No/less areola visible above than below the mouth | 23 (23.2) |

| Chin not touching the breast | 27 (27.3) |

Table 2 depicts that mothers <30 years had higher odds of maintaining improper positioning (adjusted odds ratio AOR: 10.6; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.4–46.7; P = 0.002) and poor attachment (AOR: 10.9; 95% CI: 2.4–50.2; P = 0.002). Besides, nonworking mothers showed higher odds of improper positioning (AOR: 9.0; 95% CI: 2.0–39.6; P = 0.004) and poor attachment (AOR: 7.2; 95% CI: 1.7–31.0; P = 0.008). Notably, infants <10 days old were predictors for improper positioning (AOR: 10.0; 95% CI: 1.5–65.3; P = 0.016) and poor attachment (AOR: 9.0; 95% CI: 1.3–63.9; P = 0.028). In addition, failure to receive breastfeeding counselling were associated with improper positioning (AOR: 4.7; 95% CI: 1.0–21.2; P = 0.045) and poor attachment (AOR: 6.5; 95% CI: 1.4–30.8; P = 0.018). The Nagelkerke pseudo-R2 value for the final model was 55% for positioning and 53.2% for attachment.

Table 2.

Determinants of improper positioning and poor attachment maintained during breastfeeding among postnatal mothers in multivariate analysis (n=99)

| Variables | Total (n) | Positioning | Attachment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| Improper positioning, n (%) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Poor attachment,n (%) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | ||

| Mother’s age (years) | |||||

| <30 | 49 | 22 (44.9) | 10.6 (2.4-46.7)* | 21 (42.9) | 10.9 (2.4-50.2)* |

| >30 | 50 | 6 (12.0) | 1 | 6 (12.0) | 1 |

| Mother’s occupation | |||||

| Not working | 57 | 23 (40.3) | 9.0 (2.0-39.6)* | 22 (38.6) | 7.2 (1.7-31.0)* |

| Working | 42 | 5 (11.9) | 1 | 5 (11.9) | 1 |

| Infant’s age (days) | |||||

| <10 | 68 | 26 (38.2) | 10.0 (1.5-65.3)* | 25 (36.8) | 9.0 (1.3-63.9)* |

| >10 | 31 | 2 (6.4) | 1 | 2 (6.4) | 1 |

| Breastfeeding counselling | |||||

| Not received | 42 | 17 (40.5) | 4.7 (1.0-21.2)* | 17 (40.5) | 6.5 (1.4-30.8)* |

| Received | 57 | 11 (19.3) | 1 | 10 (17.5) | 1 |

*P<0.05. OR: Odds ratio, CI: Confidence interval

In Table 3, as suggested by the staff nurses, poster displays in wards and OPDs, annual training for healthcare workers, counseling targeting the young and illiterate mothers, assisting those who have problems in maintaining proper positioning and attachment, and counseling focusing the initial 10 days after delivery were the priority action points to improve poor breastfeeding practices. Kendalls' Concordance Coefficient (W) was 0.3 and it implies a weak agreement in ranking.

Table 3.

Mean rank of action points to improve poor breastfeeding practices among postnatal mothers (n=45)

| Action points | Mean rank |

|---|---|

| Displaying posters on proper breastfeeding positioning and attachment in the wards and OPDs | 3.0 |

| Conducting annual training for the healthcare workers involved in breastfeeding counseling | 3.1 |

| Breastfeeding counseling should focus more on the young mothers | 5.7 |

| Breastfeeding counseling should focus more on the illiterate mothers | 5.7 |

| Assisting postnatal mothers who have problems in maintaining proper positioning and attachment | 6.4 |

| Breastfeeding counseling is crucial in the initial 10 days after delivery | 6.7 |

OPDs: Outpatient departments

DISCUSSION

In the present study, about 28.3% and 27.3% of mothers failed to demonstrate proper positioning and good attachment respectively. Distinctively, factors such as mothers' age, mothers' occupation, infants' age, and breastfeeding counseling were associated with breastfeeding techniques. Poster displays, healthcare workers' training, counseling focusing on young and illiterate mothers in the early postnatal period, and assisting mothers who have difficulty in maintaining proper breastfeeding techniques were the priority action points to improve the poor breastfeeding practices.

We found that 28.3% of mothers demonstrated improper positioning and 27.3% infants showed poor attachment. In contrast, in Chennai, a hospital-based cross-sectional study showed that more than half of the mothers demonstrated incorrect breastfeeding techniques.[5] Likewise, a facility-based cohort study in Delhi found that 88.5% of mothers had problems in positioning and attachment.[4] The prior antenatal counseling in our hospital would have incorporated sufficient knowledge in breastfeeding techniques during postnatal period and hence in comparison to other studies across India we had a lesser proportion of mothers with poor breastfeeding techniques.

Our study showed that mothers <30 years were associated with improper positioning and poor attachment. This could be explained by the fact that young mothers lack adequate experience in breastfeeding.[8,16] Similarly, a cross-sectional study in Delhi found that young mothers demonstrated poor breastfeeding techniques.[7] Likewise, in Gujarat, a community-based assessment highlighted that maternal age and parity influenced positioning and attachment.[11] Hence, there is a dire need to educate and assist the young mothers and primigravidas in maintaining proper breastfeeding techniques.

Notably, nonworking mothers emerged as significant predictors for incorrect breastfeeding techniques. Nonworking mothers on account of lower levels of education failed to seek health information on breastfeeding.[8] In comparison to our study, previous studies exhibited a significant association between lower maternal education and poor breastfeeding techniques but did not show any association between maternal occupation and breastfeeding techniques.[7,17] Consequently, both maternal education and occupation should be targeted in counseling.

In our study, mothers with infants <10 days old failed to demonstrate proper breastfeeding techniques. Young infants have less physical and psychological maturity to attach to the breasts properly.[8] Goyal et al. in a hospital-based study showed that poorer attachment and suckling were common in early neonatal period, preterm babies, and low birth weight babies.[18] In Gujarat, a community-based assessment showed a significant association between preterm and low birth weight babies and poor breastfeeding techniques but did not show any association between infants' age and breastfeeding techniques.[11] Unlike other studies, as we have excluded infants in neonatal intensive care unit we could not demonstrate any significant findings in relation to prematurity and low birth weight. Thus, mothers needed more support in the early postnatal period with special attention to preterm and low birth weight babies.

Notably, failure to receive breastfeeding counseling played a pivotal role in improper breastfeeding techniques. In Nagpur, a cross-sectional study highlighted the importance of health education and support to the lactating mothers.[19] As stated by our staff nurses, in order to make the counseling more effective, periodic training should be offered to the healthcare workers. De Jesus et al. in a systematic review found that healthcare professionals' training would be effective in improving breastfeeding practices.[20] Further, counseling should target the young illiterate mothers in the early postnatal period and render support to those who have problems in maintaining proper breastfeeding techniques.

The present study not only captured the factors influencing poor breastfeeding techniques but also prioritized the key action points to improve the poor breastfeeding practices. The questionnaire was developed in alignment with the standard guidelines such as BFHI and IMNCI. Errors due to self-reported findings were minimized by observation of the breastfeeding techniques. As data collection was done by a single trained investigator, observers' bias was minimized. Since it was a cross-sectional assessment of positioning and attachment, temporality could not be established. Being a single-centric facility-based study, the findings cannot be generalized in varied settings.

CONCLUSION

Our study found that factors such as young mothers, homemakers, young infants, and failure to receive breastfeeding counseling influenced poor breastfeeding techniques. As recommended by the staff nurses, poster displays, healthcare workers' training, targeted counseling, and assistance were the prioritized action points to improve the poor breastfeeding practices. Further, in order to achieve the level of Baby Friendly Hospital, these action points should be implemented by the healthcare professionals in the Obstetrics and Paediatrics department at the point of discharge.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We would like to acknowledge all the staff nurses in the obstetrics and pediatrics department and the postnatal mothers for their valuable support and co-operation in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Neonatal Coordinating Group. Neonatology Clinical Guidelines King Edward Memorial/Princess Margaret Hospitals. NICCU Clinical Guidelines; 2014. [Last accessed on 2020 Dec 20]. Available from: http://www.kemh.health.wa.gov.au/services/nccu/guidelines/documents/MonitoringAndObservationFrequencyGuidelines.pdf .

- 2.Mulder PJ. A concept analysis of effective breastfeeding. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2006;35:332–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dongre AR, Deshmukh PR, Rawool AP, Garg BS. Where and how breastfeeding promotion initiatives should focus its attention? A study from rural Wardha. Indian J Community Med. 2010;35:226–9. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.66865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suresh S, Sharma KK, Saksena M, Thukral A, Agarwal R, Vatsa M. Predictors of breastfeeding problems in the first postnatal week and its effect on exclusive breastfeeding rate at six months: Experience in a tertiary care centre in Northern India. Indian J Public Health. 2014;58:270–3. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.146292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aswathaman N, Sajjid M, Kamalarathnam CN, Seeralar AT. Assessment of Breastfeeding Position and Attachment (ABPA) in a tertiary care centre in Chennai, India: An observational descriptive cross-sectional study. Int J Contemp Pediatr. 2018;5:2209–16. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. Students' Handbook for Integrated Management of Neonatal and Childhood Illness (IMNCI. Country Office for India: World Health Organization. 2003. [Last accessed on 2020 Dec 20]. Available from: https://www.jknhm.com .

- 7.Parashar M, Singh S, Kishore J, Patavegar BN. Breastfeeding attachment and positioning technique, practices and knowledge of related issues among mothers in a resettlement colony of Delhi. Infant Child Adolesc Nutr. 2015;20:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Degefa N, Tariku B, Bancha T, Amana G, Hajo A, Kusse Y, et al. Breast feeding practice: Positioning and attachment during breast feeding among lactating mothers visiting health facility in Areka Town, Southern Ethiopia. Int J Pediatr. 2019;2019:8969432. doi: 10.1155/2019/8969432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Family Health Survey-4 Publications – Reports; 2016. [Last accessed on 2020 Dec 20]. Available from: http://rchiips.org/nfhs/NFHS-4Report.shtml .

- 10.Cresswell JW, Clark VL. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. 3rd ed. Los Angeles: SAGE Publication Ltd; 2009. pp. 71–5. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prajapati AC, Chandwani H, Rana B, Sonaliya KN. A community based assessment study of positioning, attachment and suckling during breastfeeding among 0-6 months aged infants in rural area of Gandhinagar district, Gujarat, India. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2016;3:1921–6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Implementation Guidance. Protecting, Promoting and Supporting Breastfeeding in Facilities providing Maternity and Newborn Services: The Revised Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative; 2018. [Last accessed on 2020 Dec 20]. Available from: https://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/infantfeeding/bfhiimplementation-2018.pdf .

- 13.Rosner B. Fundamentals of Biostatistics. 8th ed. United States: Cengage Learning; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saha I, Paul B. Essentials of Biostatistics. 2nd ed. Kolkata: Academic Publishers; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gearhart A, Booth DT, Sedivec K, Schauer C. Use of Kendall's coefficient of concordance to assess agreement among observers of very high resolution imagery. Geocarto Int. 2013;28:517–26. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tiruye G, Mesfin F, Geda B, Shiferaw K. Breastfeeding technique and associated factors among breastfeeding mothers in Harar city, Eastern Ethiopia. Int Breastfeed J. 2018;13:5. doi: 10.1186/s13006-018-0147-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chouhan Y, Siddharth R, Sakalle S, Mahawar P, Bhaskar P, Gupta D, et al. A cross-sectional study to assess breastfeeding positioning and attachment among mother infant pairs in Indore. Ann Community Health. 2020;8:31–6. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goyal RC, Banginwar AS, Ziyo F, Toweir AA. Breastfeeding practices: Positioning, attachment (latch-on) and effective suckling – A hospital-based study in Libya. J Family Community Med. 2011;18:74–9. doi: 10.4103/2230-8229.83372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thakre SB, Thakre SS, Ughade SM, Golawar S, Thakre AD, Kale P. The breastfeeding practices: The positioning and attachment initiative among the mothers of rural Nagpur. J Clin Diagn Res. 2012;6:1215–8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Jesus PC, de Oliveira MI, Fonseca SC. Impact of health professional training in breastfeeding on their knowledge, skills, and hospital practices: A systematic review. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2016;92:436–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2015.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]