Abstract

Background:

Pregnancy is a motivating factor to quit smoking, but many women relapse postpartum. The underlying mechanisms and the necessary duration of breastfeeding that provide long-term protection against postpartum smoking relapse are unknown.

Aims:

We aimed to examine (1) associations of smoking cessation with breastfeeding initiation and duration; (2) necessary breastfeeding duration to reduce or prevent risk of postpartum smoking relapse.

Methods:

In this cohort study, we recruited 55 mothers, either smoking or have quit smoking, who recently delivered their baby from the Greater Buffalo area, NY, USA.

Results:

Quitters had a higher breastfeeding initiation rate (73.7% versus 30.8%; p = 0.029) and breastfed longer (p < 0.024) than nonquitters. Mothers who never breastfed relapsed quicker than mothers who did (p = 0.039). There was a 28% reduction in smoking relapse at 12 months postpartum for every month longer of breastfeeding duration (confounder-adjusted hazard ratio, 0.72 [95% confidence interval, 0.55–0.94]; p = 0.014). The estimated smoking relapse risk was 60.0% for nonbreastfeeding, 22.4% for 3 months of breastfeeding, 8.4% for 6 months of breastfeeding, and 1.2% for 12 months of breastfeeding.

Conclusion:

Smoking cessation was associated with increased breastfeeding initiation and duration. Smoking relapse risk decreased with longer breastfeeding duration, and 12 months of breastfeeding may help to prevent smoking relapse. An integrated intervention of maternal smoking cessation and breastfeeding promotion is promising to enhance both behaviors.

Keywords: smoking cessation, breastfeeding, public health, smoking relapse, maternal and child health

Introduction

Pregnancy is a common motivation for women to quit smoking, as maternal smoking during pregnancy is associated with adverse health outcomes such as stunted fetal development, preterm delivery, and fetal death.1 Although about half of pregnant smokers quit by the third trimester,2 many relapse within 6 months postpartum.3 Therefore, prevention of postpartum smoking relapse is a public health priority.

Research supports bidirectional associations between smoking and breastfeeding. On the one hand, smoking mothers are less likely to initiate breastfeeding than nonsmokers, and are at higher risk for early weaning.3 On the other hand, breastfeeding is associated with decreased risk of postpartum smoking relapse.1 However, most studies in this field are limited by uncertain temporality, not using objective smoking measurements, not examining reciprocal associations within the same study population, and unclear mechanisms. In addition, previous studies have not identified the necessary duration of breastfeeding that will provide long-term protection against postpartum smoking relapse.1

Therefore, within prospectively prebirth cohorts that followed the same women and their infants from pregnancy up to 1 years postpartum, we aimed to examine (1) the associations of smoking cessation with breastfeeding initiation and duration, which could help to identify the underlying mechanisms; (2) the necessary breastfeeding duration to substantially reduce or prevent the risk of postpartum smoking relapse.

Materials and Methods

Research design

The design was a prospective longitudinal cohort study. The study was approved from our institutions IRB (IRB no: MODCR00004754 A pilot study of maternal smoking in lactation and infant weight-for-length gain; approval date: September 21, 2015). We reported study details based on the guidelines in the STROBE statement (Supplementary Data).

Sample

Eligible participants were screened at the time of their delivery. Inclusion criteria were participants must either be currently smoking or have quit smoking, they must be >18 years old, and have had a live birth in the past week. Our convenient sample size was 55 participants from local OBGYN clinics and our Smoking Cessation clinic in the Greater Buffalo area, NY, USA. We paid the participants $15 for completing the survey and another $15 for completing the visit.

Measurement

Smoking-related measures

We measured smoking status by self-report and biochemical tests. At each study visit, participants reported the daily number of cigarettes smoked since the previous visit. We used the NicAlert to measure urine cotinine (metabolite of nicotine), which reflects nicotine exposure in the past several days with high validity.4 Current smoking abstinence was confirmed if urine cotinine was <100 ng/mL. Smoking cessation during pregnancy was defined as nonsmoking for 7 consecutive days before delivery (7-day point prevalence). If a participant self-reported data different than what showed up on the cotinine test, we used the results from the cotinine test over the self-report. Among quitters during pregnancy, timing of postpartum smoking relapse was defined as the first day after returning to smoking for 7 consecutive days in the postpartum period.

Breastfeeding-related measures

Within the first 7 days after delivery, we measured breastfeeding initiation by asking participants the question, “Did you ever breastfeed or try to breastfeed your new baby?” with two choices (Yes versus No). A “Yes” response was defined as breastfeeding initiation. In monthly subsequent postpartum surveys, participants updated their breastfeeding status by answering the question, “Was your baby breastfed at all in the past 7 days?” with two choices (Yes versus No). We also asked detailed questions about the breast feeding itself such as “About how long does an average breastfeeding last?” with the choices “Less than 10 minutes,” “10 to 19 minutes,” “20 to 29 minutes,” “30 to 39 minutes,” “40 to 49 minutes,” and “50 or more minutes.”

We also asked “In an average 24-hour period, what is the longest time for you, the mother, between breastfeedings or expressing milk? Please count the time from the start of one breastfeeding or expressing session to the start of the next. Please think of time between feedings during both night and day to find the longest time.” Accordingly, we defined breastfeeding duration as the latest month before weaning. Self-reported breastfeeding status was subject to bias especially over-reporting due to social desirability.

Covariate measures

Based on the literature and prior knowledge, we considered some key sociodemographic, pregnancy, and smoking characteristics as covariates. At enrollment, participants reported race (non-Hispanic Caucasian, non-Hispanic black, and other), age (≤24, 25–29, and ≥30 years), education (high school or lower, some college or vocational training, and completed a 2- or 4-year degree), employment (working full- or part-time, and not working), marital status (married and not married), daily number of cigarettes (1–4, 5–9, and ≥10), quitting status (quitter and nonquitter), gestation age at enrollment (1–13 weeks, 14–27 weeks, and ≥28 weeks), family annual income (<$5,000, $5,000–$11,999, $12,000–$24,999, and ≥$25,000), mother's annual income (<$5,000, $5,000–$15,999, and ≥$16,000), and prepregnancy body mass index (BMI) in kg/m2.

Data collection

Participants were expected to do 13 monthly postpartum visits starting within the first 2 weeks after the delivery date. They completed surveys and biochemical tests such as the Covita Micro+ Smokerlyzer to measure breath carbon monoxide and the NicAlert to measure urine cotinine (metabolite of nicotine). At the screening visit we explained the study and received consent from the participants.

Data analysis

We conducted data analysis in SAS 9.4 and set the significant level α as 0.05. We addressed missing data for breastfeeding duration and smoking relapse by using the last-observation-carried-forward method.5 We reported mean and standard deviation for continuous variables (breastfeeding duration), whereas n and % for categorical variables (smoking status and breastfeeding initiation).

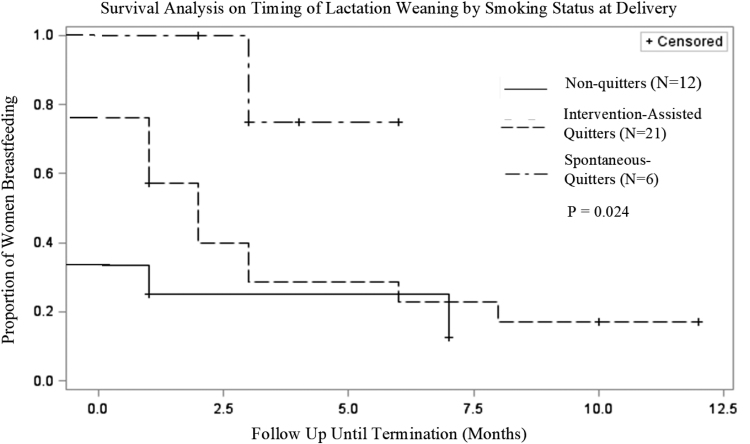

Aim 1—Associations of smoking cessation during pregnancy with breastfeeding-related outcomes. We conducted a log-rank test and used a Kaplan–Meier curve (PROC LIFETEST) to compare breastfeeding duration stratified by those who did not quit, those who quit with help from smoking cessation counselors (intervention-assisted) and those who quit spontaneously.

Aim 2—Associations of breastfeeding practices and postpartum smoking relapse. Among participants who quit during or before pregnancy and had postpartum follow-up data (n = 39), we conducted a log-rank test and used a Kaplan–Meier curve (PROC LIFETEST) to compare timing of smoking relapse by breastfeeding initiation status. We used a Cox proportional hazard model (PROC PHREG) to examine the association between breastfeeding duration and the timing of postpartum smoking relapse, adjusting for educational attainment (a strong confounder for smoking and breastfeeding). Hazard ratios (HRs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated from the Cox model.

Based on the HR, we estimated the risk of postpartum smoking relapse using the approach described in literature.6 We evaluated the hazard proportionality with postpartum time by testing the interaction term between each predictor and postpartum time. None of the interaction terms were significant (all two-tailed p-value >0.05).

Results

Sample characteristics

The average postpartum follow-up duration for the combined sample was 6.26 months. Among 55 eligible participants in our analytic sample, 43.6% were non-Hispanic black, 38.2% were non-Hispanic Caucasian, and 18.2% had other races; 49.1% were >30 years; 40.0% had a high school or lower level of education; 49.1% were workers; 45.5% were married; 47.3% smoked 1–4 cigarettes per day at enrollment or before quitting; 78.2% were smoking abstinent at delivery; 17.3% had a gestation age at enrollment of 28 weeks or greater; 40.0% had a family income of $25,000 or greater; 41.8% had 3 or more live births; 32.1% had a smoking partner; and 30.9% were underweight (BMI <18.5 kg/m2) or had a normal weight (18.5 ≤ BMI ≤24.9) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic, Pregnancy, and Smoking Characteristics of Study Population

| Characteristica | n (%)/mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Total | 55 (100%) |

| Race | |

| Non-Hispanic Caucasian | 21 (38.2) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 24 (43.6) |

| Other | 10 (18.2) |

| Age, years | 29.6 ± 5.5 |

| ≤24 | 12 (21.8) |

| 25–39 | 16 (29.1) |

| ≥30 | 27 (49.1) |

| Education | |

| Less than seventh grade to high school | 22 (40.0) |

| Some college or vocational training | 16 (29.1) |

| Completed a 2- or 4-year degree | 17 (30.9) |

| Employment | |

| Working full- or part-time | 27 (49.1) |

| Unemployed | 16 (29.1) |

| Raising children full-time | 9 (16.4) |

| Full- or part-time student | 3 (5.5) |

| Married | 25 (45.5) |

| No. of cigarettes a day at baselineb | 5.8 ± 5.1 |

| 1–4 | 26 (47.3) |

| 5–9 | 19 (34.6) |

| 10+ | 10 (18.2) |

| Smoking abstinence at delivery | 43 (78.2) |

| Gestation age at enrollment, weeks | 19.0 ± 8.6 |

| ≤13 | 15 (28.9) |

| 14–27 | 28 (53.9) |

| ≥28 | 9 (17.3) |

| Family income, USD | |

| <5,000 | 18 (32.7) |

| 5,000–11,999 | 7 (12.7) |

| 12,000–24,999 | 8 (14.6) |

| ≥25,000 | 22 (40.0) |

| Mother's annual income, USD | |

| <5,000 | 23 (43.4) |

| 5,000–15,999 | 12 (22.6) |

| ≥16,000 | 18 (34.0) |

| Number of previous live births | |

| None | 8 (14.6) |

| 1–2 | 24 (43.6) |

| 3 or more | 23 (41.8) |

| Having children ≤12 months old | 16 (29.1) |

| Current use of alcohol | 1 (1.8) |

| Marijuana use during this pregnancy | 16 (29.1) |

| Partner's smoking status | |

| Smoker | 27 (50.9) |

| Nonsmoker | 17 (32.1) |

| No partner | 9 (17.0.0) |

| Pregnancy BMI, kg/m2 | 28.6 ± 7.4 |

| Underweight or normal | 17 (30.9) |

| Overweight | 18 (32.7) |

| Obese | 20 (36.4) |

For some characteristics, the sum of categories was less than the total sample size due to missing data.

Baseline for smoking study is before intervention and baseline for breastfeeding study is before quitting.

BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation; USD, United States dollars.

Associations between smoking cessation during pregnancy and breastfeeding outcomes

After delivery, all 6 of the mothers who quit, 16 of the 21 mothers who quit with help of smoking cessation counselors, and 4 of the 12 mothers who did not quit, initiated breastfeeding. There was a significant difference in breastfeeding initiation between spontaneous quitters and nonquitters (p < 0.001) as well as between mothers who quit with help of smoking cessation counselors and mothers who did not quit (p = 0.027). There was a significant difference in timing of breastfeeding termination between spontaneous quitters and nonquitters (p = 0.018), and marginal difference between mothers who quit with help of smoking cessation counselors quitters and mothers who did not quit (p = 0.152) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Survival analysis on timing of lactation weaning by smoking status at delivery.

Associations between breastfeeding practices and postpartum smoking relapse

At birth and every subsequent postpartum month, participants who were still breastfeeding had a lower risk of smoking relapse later than participants who were not breastfeeding at that time (Fig. 2). The Kaplan–Meier curve and log-rank test showed that participants who never breastfed relapsed quicker than participants who ever breastfed (p = 0.039).

FIG. 2.

Survival analysis on timing of relapse based on breastfeeding initiation.

In the Cox proportional hazard model among the 27 quitters with postpartum follow-up data, there was a 28% reduction in smoking relapse for every month longer of breastfeeding duration (crude HR, 0.72 [95% CI, 0.54–0.92]; p = 0.009) (Table 2). After adjusting for maternal education (the only significant confounder), this association remained almost unchanged (confounder-adjusted HR, 0.72 [95% CI, 0.55–0.94]; p = 0.014). The estimated risk of postpartum smoking relapse at 12 months was 60.0% for never breastfeeding, 43.4% for 1 month of breastfeeding, 22.4% for 3 months of breastfeeding, 8.4% for 6 months of breastfeeding, and 1.2% for 12 months of breastfeeding (Fig. 3).

Table 2.

Cox Regression on Associations Between Breastfeeding and Risk of Smoking Relapse by 12 Months Postpartum (n = 55)

| Postpartum smoking relapse by 12 months postpartum |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude |

Adjusted |

|||

| HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | |

| Model 1 | ||||

| Ever breastfeeding | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.32 (0.10–1.00) | 0.0482 | 0.53 (0.15–1.88) | 0.329 |

| Education | ||||

| Less than seventh grade to high school | 4.48 (0.92–21.82) | 0.063 | ||

| Some college or vocational training | 2.7 (0.49–14.99) | 0.255 | ||

| Completed a 2- or 4-year college degree | Reference | |||

| Study | ||||

| Smoking cessation study | 2.22 (0.54–9.11) | 0.270 | ||

| Breastfeeding study | Reference | |||

| Model 2 | ||||

| Breastfeeding duration, months | 0.72 (0.56–0.92) | 0.009 | 0.73 (0.55–0.98) | 0.039 |

| Education | ||||

| Less than seventh grade to high school | 5.60 (1.10–28.62) | 0.038 | ||

| Some college or vocational training | 2.42 (0.45–13.06) | 0.305 | ||

| Completed a 2- or 4-year college degree | Reference | |||

| Study | ||||

| Smoking cessation study | 1.19 (0.25–5.66) | 0.823 | ||

| Breastfeeding study | Reference | |||

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

FIG. 3.

Predicted risk of smoking relapse at 12 months by breastfeeding duration.

Discussion

In this study, we prospectively followed women throughout pregnancy and postpartum to determine how their smoking status would impact breastfeeding initiation and duration. We also analyzed if breastfeeding could reduce the risk of postpartum smoking relapse among ex-smokers. We found smoking cessation was associated with increased breastfeeding initiation and duration. Furthermore, breastfeeding for 6 months was associated with a large reduction in risk of postpartum smoking relapse, whereas breastfeeding for 12 months might prevent smoking relapse. Our novel results provide evidence supporting an integrated intervention to promote smoking cessation and breastfeeding to enhance both behaviors.

Effect of smoking cessation on breastfeeding initiation

In line with previous studies, we found quitters had a higher breastfeeding initiation due to higher breastfeeding intention and removal of smoking-related lactation inhibition after quitting smoking. For example, a previous study found that breastfeeding intention was higher among smokers who were considering quitting than those who were not.6 This intention could be attributed to the thought process that ex-smokers might believe their breast milk would not be contaminated by harmful tobacco metabolites (e.g., nicotine) anymore and thus feeling safer to breastfeed.7,8

In addition, in a previous research study it was found that nicotine decreases the level of prolactin in maternal blood, which is responsible for lactation.9 As a result, smoking cessation would lead to decrease in nicotine, which in return would increase the release of prolactin to a normal level, thus promoting intention of lactation in mothers.

Effect of smoking cessation on breastfeeding duration

As we hypothesized, nonquitters weaned off breastfeeding earlier than quitters. This difference could be due to the low amount of milk production in smokers compared with nonsmokers.9,10 Specifically, the bitter taste and smell of nicotine11 along with low-fat concentration (∼19% lower)10 in the breast milk of smoking mothers may cause infants' aversion toward distasteful breast milk. This aversion may lead to lower infant sucking pressure during breastfeeding, which along with nicotine-exposure-related lower sucking frequency12 can reduce the infant's ability to empty maternal breasts, subsequently disturb maternal secretion of lactation hormones, and eventually decrease milk production.10 In addition, the perceived infant aversion may make mothers turn to formula to satisfy the infant and subsequently wean off breastfeeding earlier.

Effect of breastfeeding duration on postpartum smoking relapse

Consistent with previous research,1,3 we found breastfeeding was associated with a lower risk of postpartum smoking relapse. This protective effect of breastfeeding may be attributed to breastfeeding-related increase in oxytocin, a milk ejection hormone as response to infant suckling nipples.13 Research has shown oxytocin is linked to decreased anxiety and depression,14,15 two negative emotions that can trigger smoking relapse.16

A unique contribution of our study to the science was identifying how long breastfeeding is needed to prevent smoking relapse, a critical research gap in this field. Our results suggested a 28% decrease in the risk of smoking relapse for every subsequent month a mother breastfeeds. The estimated risk of smoking relapse at 12 months decreased largely from 60.0% for never breastfeeding to 8.4% with 6 months of breastfeeding, and was almost eliminated (1.2%) with 12 months of breastfeeding. Our finding was consistent with a previous study showing breastfeeding for >6 months was associated with smoking abstinence <2 years.3 It also supports that ex-smokers can get additional benefits from adhering to the current recommendation of breastfeeding for at least 12 months by the American Academy of Pediatrics.17

Limitations and strengths

Our study had several important limitations. First, our analytic sample was relatively small and was recruited only from one geographic area (Western New York), which might limit the generalizability of our findings. Second, retrospective self-reported breastfeeding status was subject to recall bias, especially over-reporting due to social desirability. Finally, there was a considerable amount of missing data due to loss to follow-up or not filling out surveys at certain months, which might threaten the accuracy of our results.

One of the strengths of our study was the prospective study design with follow-up from pregnancy up to 1 year postpartum, which allowed us to collect data repeatedly and reduce recall bias. Second, smoking abstinence was objectively verified by two biochemical tests. Third, we considered a full spectrum of breastfeeding measures, including initiation and duration, however not exclusivity.

Conclusion

Our research suggested that smoking cessation during pregnancy was associated with increased breastfeeding initiation and duration. Risk of postpartum smoking relapse decreased with longer breastfeeding duration. Breastfeeding for 6 months may largely reduce risk of postpartum smoking relapse, whereas breastfeeding for 12 months may help to prevent postpartum smoking relapse. An integrated intervention of maternal smoking cessation and breastfeeding promotion is promising to enhance both behaviors, and thus improve maternal and child health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the administrative support from Teresa Quattrin, Vanessa Barnabei, Faye Justicia-Linde and Aimée Gomlak, as well as the assistance on recruitment by the staff in the Kaleida Health OB/GYN Centers, the Sisters of Charity Hospital of Buffalo, the Buffalo Prenatal–Perinatal Network, and other local OB/GYN clinics.

Authorship Confirmation Statement

All coauthors have reviewed and approved of the article before submission.

Disclosure Statement

A.I., M.H., L.S., J.I., and M.G.K. completed the student research and X.W. was the advisor. The authors declare that they have nothing to disclose and no conflict of interest.

Funding Information

This study was supported in part through Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) Pilot Study support from National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant UL1TR001412; R21 exploratory research support from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), NIH grant R21HD091515; and seed funding from the Department of Pediatrics, State University of New York at Buffalo (all awarded to X.W.). X.W.'s time effort was also supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under R40MC31880 entitled “Socioeconomic disparities in early origins of childhood obesity and body mass index trajectories” (PI, X.W.).

The information, content, and/or conclusions are those of the author, and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by NIH, HRSA, HHS, or the U.S. Government. The sponsors had no role in writing the article or the decision to submit it for publication.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Orton S, Coleman T, Coleman-Haynes T, et al. Predictors of postpartum return to smoking: A systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res 2018;20:665–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rockhill KM, Tong VT, Farr SL, et al. Postpartum smoking relapse after quitting during pregnancy: Pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system, 2000–2011. J Womens Health 2016;25:480–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Logan CA, Rothenbacher D, Genuneit J. Postpartum smoking relapse and breast feeding: Defining the window of opportunity for intervention. Nicotine Tob Res 2017;19:367–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gaalema DE, Higgins ST, Bradstreet MP, et al. Using NicAlert strips to verify smoking status among pregnant cigarette smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend 2011;119:130–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zwiener I, Blettner M, Hommel G. Survival analysis: Part 15 of a series on evaluation of scientific publications. Dtsch Ärztebl Int 2011;108:163–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Haslam C, Lawrence W, Haefeli K. Intention to breastfeed and other important health-related behaviour and beliefs during pregnancy. Family Pract 2003;20:528–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Goldade K, Nichter M, Nichter M, et al. Breastfeeding and smoking among low-income women: Results of a longitudinal qualitative study. Birth Iss Perin Care 2008;35:230–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Carswell AL, Ward KD, Vander Weg MW, et al. Prospective associations of breastfeeding and smoking cessation among low-income pregnant women. Matern Child Nutr 2018;14:e12622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Napierala M, Mazela J, Merritt TA, et al. Tobacco smoking and breastfeeding: Effect on the lactation process, breast milk composition and infant development. A critical review. Environ Res 2016;151:321–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hopkinson JM, Schanler RJ, Fraley JK, et al. Milk production by mothers of premature infants: Influence of cigarette smoking. Research Support, U.S. Gov't, Non-P.H.S. Pediatrics 1992;90:934–938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mennella JA, Beauchamp GK. Smoking and the flavor of breast milk. N Engl J Med 1998;339:1559–1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Martin DC, Martin JC, Streissguth AP, et al. Sucking frequency and amplitude in newborns as a function of maternal drinking and smoking. Curr Alcohol 1979;5:359–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Organization WH. Infant and young child feeding. In: Infant and Young Child Feeding: Model Chapter for Textbooks for Medical Students and Allied Health Professionals. 2009. WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Heinrichs M, Baumgartner T, Kirschbaum C, et al. Social support and oxytocin interact to suppress cortisol and subjective responses to psychosocial stress. Biol Psychiatry 2003;54:1389–1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Windle RJ, Shanks N, Lightman SL, et al. Central oxytocin administration reduces stress-induced corticosterone release and anxiety behavior in rats. Endocrinology 1997;138:2829–2834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Leventhal AM, Piper ME, Japuntich SJ, et al. Anhedonia, depressed mood, and smoking cessation outcome. J Consult Clin Psychol 2014;82:122–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pediatrics AAo. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. American Academy of Pediatrics, Work Group on Breastfeeding. Breastfeed Rev J 1998;6:31–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.