Abstract

Background:

Hybrid Closed-Loop (HCL) systems aid individuals with type 1 diabetes in improving glycemic control; however, sustained use over time has not been consistent for all users. This study developed and validated prognostic models for successful 12-month use of the first commercial HCL system based on baseline and 1- or 3-month data.

Methods and Materials:

Data from participants at the Barbara Davis Center (N = 85) who began use of the MiniMed 670G HCL were used to develop prognostic models using logistic regression and Lasso model selection. Candidate factors included sex, age, duration of diabetes, baseline hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), race, ethnicity, insurance status, history of insulin pump and continuous glucose monitor use, 1- or 3-month Auto Mode use, boluses per day, and time in range (TIR; 70–180 mg/dL), and scores on behavioral questionnaires. Successful use of HCL was predefined as Auto Mode use ≥60%. The 3-month model was then externally validated against a sample from Stanford University (N = 55).

Results:

Factors in the final model included baseline HbA1c, sex, ethnicity, 1- or 3-month Auto Mode use, Boluses per Day, and TIR. The 1- and 3-month prognostic models had very good predictive ability with area under the curve values of 0.894 and 0.900, respectively. External validity was acceptable with an area under the curve of 0.717.

Conclusions:

Our prognostic models use clinically accessible baseline and early device-use factors to identify risk for failure to succeed with 670G HCL technology. These models may be useful to develop targeted interventions to promote success with new technologies.

Keywords: Hybrid closed loop, Artificial pancreas, Type 1 diabetes, Predictive modeling, Pediatric diabetes

Introduction

Despite growing availability of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) pumps and continuous glucose monitors (CGMs), hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) values continue to rise across the United States type 1 diabetes population.1,2 Hybrid closed loop (HCL) artificial pancreas systems, which combine a CSII pump, CGM, and automated insulin dosing algorithm counter this trend by reducing hyperglycemic and hypoglycemic exposure.3–12 The Medtronic MiniMed 670G is the first HCL system approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration. This system uses Guardian Sensor 3 CGM values to automate basal insulin delivery but requires user input of grams of carbohydrates consumed for meal boluses. The system automates basal delivery while in Auto Mode but may exit to conventional Manual Mode due to sensor errors, maximum or minimum insulin delivery, sustained hyper- or hypoglycemia, or other system constraints.13

Remaining in Auto Mode generally requires entry of 2–4 blood glucose meter checks per day for sensor calibration and hyperglycemia correction.14 While this system significantly improves glycemic control in highly monitored and supported trials,4,6 several observational studies of its clinical use as part of routine care show decline and discontinuation of Auto Mode use across time.14–17

A prognostic model to predict which individuals are likely to disengage with this HCL technology could greatly aid providers in directing resources to support success with this technology. The methodology used to develop such a model could also be translatable to prognostic model development for other HCL systems, which would likely require their own models given differences in system designs. The purpose of this study was to develop a prognostic model for Medtronic 670G HCL discontinuation based on 12 months of HCL use from a prospective study.14,17 The model's performance was then tested for external validity against a previously published dataset.15 Variables related to demographic characteristics, baseline glycemic control, and device use within the first months of starting HCL were examined as predictors of success with device use at 12 months.

Materials and Methods

Participant data

Data from the Barbara Davis Center for Childhood Diabetes (BDC) pediatric clinic of persons starting the 670G system for their routine type 1 diabetes care were used to develop the prognostic model (development sample). Those starting the 670G system at this time included any child with public or private health insurance whose parents and providers mutually agreed would benefit from a HCL system. The clinic did not use any formal criteria to allow or exclude children 7+ years old from beginning the 670G system. Eligibility criteria for the development sample were youth and young adults aged 7 to 25 years with a clinical diagnosis of type 1 diabetes who received clinical care at the BDC and were prescribed a Medtronic 670G HCL system by their medical provider.

While the 670G was initially FDA approved for use in individuals aged 14 years and older, the observational trial included children as young as 7 years who were prescribed the 670G system off-label. Exclusion criteria were inability to read or speak English as questionnaires were only available in English. In addition to glycemic and demographic data participants completed the Hypoglycemia Fear Survey (HFS; Worry subscale)18–21 and the Problem Areas in Diabetes (PAID) questionnaire at each study visit.22–25 It should be noted that PAID uses different instruments for children (PAID-Peds) and adults (PAID) and that the distress measured by one tool is not directly comparable to the distress measured by the other.

All participants received standard training, which included 1–2 weeks of system use in Manual Mode followed by HCL training and transition to Auto Mode as previously described.26 Prospective data collection occurred during Manual Mode use (up to 14 days before starting Auto Mode), 1 month after starting Auto Mode (during a virtual visit), and during routine clinical follow-up, occurring approximately every 3 months during the first 12 months of Auto Mode use.14 Participants and/or their legal guardians provided consent and assent as age appropriate before study enrollment. The study was approved by the University of Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board. Participants were enrolled between September 2017 and May 2018 and followed for 12 months after enrollment.

Model performance was tested against a sample of participants who completed a prospective study at Stanford University Medical Center (validation sample). The Stanford study was a 1-year prospective observational study of both pediatric and adult participants with type 1 diabetes starting the 670G system between May 2017 and May 2018. The methods and primary analysis for this dataset are described by Lal et al.15

Outcomes

The primary outcome of interest was successful use of Auto Mode at 12 months after starting the 670G system. Auto Mode use was captured as a continuous percentage for the 2 weeks before the 12-month clinical follow-up visit, or the 9-month follow-up visit if no 12-month data were available. A total of 10 participants were missing 12-month Auto Mode data.

Successful Auto Mode use was predefined as ≥60% Auto Mode use, which was selected based on a pilot 3-month analysis by our group demonstrating that 670G users with HbA1c at or below goal (at that time <7.5% for children and <7.0% for adults) had >60% Auto Mode use, while those with HbA1c above goal had <50% Auto Mode use.27 The “successful HCL use” cutoff thus represents the Auto Mode percentage associated with having glycemic control below target for the 670G system. The 2-week window was chosen as 2 weeks of data review and is the standard lookback period for clinical care and the window recommended for CGM analysis by consensus guidelines.28

Prognostic factors

The following characteristics were considered to be potential prognostic factors for successful HCL use at 12 months: baseline HbA1c, age, sex, race, ethnicity, age at type 1 diabetes diagnosis, diabetes duration, insurance status, prior CSII use, prior CGM use, CGM use at 1 or 3 months after starting HCL, time in Auto Mode at 1 or 3 months after starting HCL, time in range (TIR; 70–180 mg/dL) at 1 or 3 months after starting HCL, number of boluses per day at 1 or 3 months after starting HCL, HFS worry subscale score, and PAID score.

The goal of model development was to test the ability of the model to predict HCL success based on the earliest prognostic factors, and therefore, initial model development only included the baseline and 1-month device-use metrics (CGM use, Auto Mode percentage, boluses per day, and TIR). In the development sample, 1-month data were obtained as part of early follow-up in the training protocol. However, in clinical care at many centers, it is common for patients to attend medical appointments every 3 months for routine diabetes follow-up. Thus, many practices would have 3-month post-HCL start follow-up data, but many did not have 1-month follow-up data. To account for this routine clinical data collection, we also evaluated a second model with 3-month HCL metrics.

HbA1c values were obtained from the electronic medical record and were measured with a point-of-care Siemens DCA Vantage Analyzer 2000 (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Elkhart, IN) calibrated every 3 months using International Federation of Clinical Chemistry reference standards. Sensor glucose data were obtained from the CareLink “Assessment and Progress Report” with TIR defined as 70–180 mg/dL.28,29 Age was captured as a continuous variable. The development sample had data available for baseline and Auto Mode follow-up at 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months. The validation sample used similar methods to the development sample although they did not capture data at 1-month and did not record CGM use at follow-up visits, only Auto Mode use.15

Statistical analyses

The sample size for this study was established to achieve 80% power to detect an area under curve (AUC) for the receiver operating curve (ROC) equal to 0.6 versus 0.5 under the null hypothesis. The study was not powered to make inference about the individual variables included in the predictive model.

Data were assessed for normality and potential outliers. Continuous variables were compared using t-tests or Kruskal-Wallis Rank Sum tests, and chi-squared or Fisher's exact tests were used for categorical variables.

Logistic regression was used to examine the associations between successful HCL use and baseline HbA1c, 1- or 3-month, HCL metrics, and demographic variables. A final multivariate model was selected using Lasso30 and the shrinkage parameter lambda was selected using 10-fold cross-validation in the R package glmnet.31 Lambda was chosen to produce the simplest possible model within 1 standard deviation of the minimum deviance obtained during cross-validation. Lasso model selection is based on minimizing prediction error, as opposed to a stepwise approach based on statistical significance. Thus, the Lasso model selection process sometimes retains variables that improve prediction accuracy but are not statistically significant after the inclusion of other covariates.

A sensitivity analysis was performed to evaluate whether interaction terms were retained by Lasso model selection, and whether comparing Hispanic participants to white participants impacted the final model (as opposed to comparing Hispanic to non-Hispanic). Because CGM use and TIR are highly correlated, a sensitivity analysis was also performed to evaluate each variable's inclusion separately, by comparing the AUC for the ROC.32

The predictive performance of the final model when fit to external data was evaluated using AUC for the ROC. In ROC analysis, the AUC is a measurement of the overall accuracy of the test, with a higher AUC demonstrating better predictive performance and AUC of 1 indicating perfect accuracy. A rough classification system for ROC AUC values is that 0.9–1.0 is excellent, 0.8–0.9 is good, 0.7–0.8 is fair, 0.6–0.7 is poor, and 0.5–0.6 is failure.32 The validation method used the predictor variables determined by the development sample with variable values and outcomes provided by the Stanford validation sample. The original model was not refit based on the validation cohort, as this would invalidate the independence of the external validation cohort from the original development cohort.

Results

Development of the prognostic model

The development sample consisted of 85 participants, 14.2 ± 3.7 years old with type 1 diabetes duration of 6.9 ± 4.0 years, and baseline HbA1c of 8.8% ± 1.7% (Table 1). Within this sample, 51.8% of participants were male. Race and ethnicity were primarily white (85.9%) and non-Hispanic (90.6%). At the final follow-up visit (12-month), 61 participants (71.8%) were in the Auto Mode failure group with mean Auto Mode use of 14.5% ± 18.9%, while 24 participants (26.7%) were in the Auto Mode success group with mean Auto Mode use of 79.3% ± 11.4%. Investigators initiated contact with study participants as part of the protocol and the median days between study contacts was 92 days with an interquartile range of 52–119 days.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics in the Development and Validation Samples

| BDC development sample (N = 85) | Stanford validation sample (N = 55) | |

|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 44 (51.8%) | 32 (58.2%) |

| Age (years) | 14.2 ± 3.7 | 26.5 ± 14.4 |

| Duration of type 1 diabetes (years) | 6.9 ± 4.0 | 14.4 ± 10.2 |

| Baseline HbA1c (%) | 8.8 ± 1.7 | 8.1 ± 1.5 |

| Race | ||

| White | 73 (85.9%) | 44 (80.0%) |

| Non-white | 12 (14.1%) | 11 (20.0%) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 8 (9.4%) | 3 (5.5%) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 77 (90.6%) | 52 (94.5%) |

| Insurance | ||

| Public | 13 (15.5%) | 2 (3.6%) |

| Private | 66 (78.6%) | 43 (78.2%) |

| Other | 5 (6.0%) | 10 (18.2%) |

| CSII pump history | ||

| ≤6 Months of prior use | 4 (4.7%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| >6 Months of prior use | 81 (95.3%) | 55 (100%) |

| CGM history | ||

| ≤6 Months of prior use | 19 (22.4%) | 2 (4.4%) |

| >6 Months of prior use | 66 (77.6%) | 43 (95.6%) |

| PAID score | ||

| Child PAID score | 36.1 ± 20.8 | — |

| Young adult PAID score | 20.5 ± 19.3 | — |

| HFS worry score | ||

| Child HFS worry score | 15.0 ± 9.5 | — |

| Young adult HFS worry score | 18.9 ± 15.0 | — |

| 1-Month CGM use (%) | 75.7 ± 21.4 | — |

| 1-Month time in Auto Mode (%) | 65.8 ± 25.4 | — |

| 1-Month TIR (%) | 60.4 ± 13.5 | — |

| 1-Month boluses per day (no.) | 6.4 ± 2.5 | — |

| 3-Month CGM use (%) | 63.3 ± 28.8 | — |

| 3-Month time in Auto Mode (%) | 51.0 ± 30.9 | 57.7 ± 34.9 |

| 3-Month TIR (%) | 59.4 ± 15.8 | 65.2 ± 13.0 |

| 3-Month boluses per day (no.) | 5.9 ± 2.2 | 6.5 ± 2.5 |

| Auto Mode use at final visit (%) | 32.8 ± 34.0 | 45.8 ± 39.6 |

| HCL success at final visit | 24 (28.2%) | 27 (49.1%) |

BDC, Barbara Davis Center for Childhood Diabetes; CGM, continuous glucose monitor; CSII, continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; HCL, hybrid closed-loop; HFS, hypoglycemia fear survey; PAID, problem areas in diabetes; TIR, time in range.

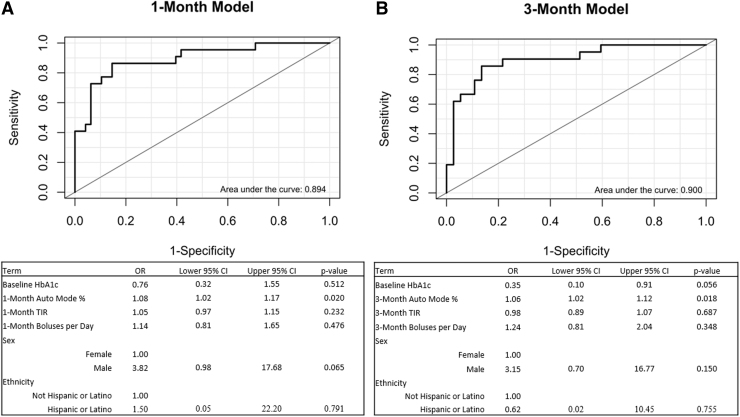

Univariate associations were examined between HCL success at 12 months and the prespecified list of candidate prognostic factors (Table 2). HCL success at 12 months was significantly associated with baseline HbA1c, 1-month CGM use, 1-month time in Auto Mode Use, 1-month TIR, 1-month boluses per day, 3-month CGM use, 3-month Auto Mode use, 3-month TIR, and 3-month boluses per day. The final prognostic model for the 1-month data included baseline HbA1c, 1-month Auto Mode use, 1-month TIR, 1-month boluses per day, sex, and ethnicity (Fig. 1A). This model demonstrated an AUC of 0.894. The 3-month model (Fig. 1B) included baseline HbA1c, 3-month Auto Mode use, 3-month TIR, 3-month boluses per day, sex, and ethnicity and demonstrated a similar AUC of 0.900.

Table 2.

Univariate Analysis of Hybrid Closed-Loop Success for Candidate Prognostic Factors in the Barbara Davis Center for Childhood Diabetes Development Sample

| HCL failure (n = 61) | HCL success (n = 24) | Total (n = 85) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 28 (45.9%) | 16 (66.7%) | 44 (51.8%) | 0.085 |

| Age (years) | 14.4 ± 3.6 | 13.5 ± 3.8 | 14.2 ± 3.7 | 0.298 |

| Duration of type 1 diabetes (years) | 7.1 ± 4.0 | 6.7 ± 4.2 | 7.0 ± 4.0 | 0.834 |

| Baseline HbA1c (%) | 9.1 ± 1.8 | 7.8 ± 0.9 | 8.8 ± 1.7 | <0.001 |

| Race | 0.337 | |||

| White | 51 (83.6%) | 22 (91.7%) | 73 (85.9%) | |

| Non-white | 10 (16.4%) | 2 (8.3%) | 12 (14.1%) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.527 | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 7 (11.5%) | 1 (4.2%) | 8 (9.4%) | |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 54 (88.5%) | 23 (95.8%) | 77 (90.6%) | |

| Insurance | 0.486 | |||

| Public | 11 (18.3%) | 2 (8.3%) | 13 (15.5%) | |

| Private | 46 (76.7%) | 20 (83.3%) | 66 (78.6%) | |

| Other | 3 (5.0%) | 2 (8.3%) | 5 (6.0%) | |

| Pump history | 0.322 | |||

| ≤6 Months of prior use | 2 (3.3%) | 2 (8.3%) | 4 (4.7%) | |

| >6 Months of prior use | 59 (96.7%) | 22 (91.7%) | 81 (95.3%) | |

| CGM history | 0.430 | |||

| ≤6 Months of prior use | 15 (24.6%) | 4 (16.7%) | 19 (22.4%) | |

| >6 Months of prior use | 46 (75.4%) | 20 (83.3%) | 66 (77.6%) | |

| PAID score | ||||

| Child PAID score | 36.9 ± 20.7 | 33.6 ± 21.7 | 36.1 ± 20.8 | 0.585 |

| Young adult PAID score | 25.5 ± 20.4 | 7.1 ± 5.6 | 20.5 ± 19.3 | 0.170 |

| HFS worry score | ||||

| Child HFS worry score | 15.9 ± 10.0 | 12.6 ± 7.9 | 15.0 ± 9.5 | 0.227 |

| Young adult HFS worry score | 22.6 ± 17.9 | 12.5 ± 5.4 | 18.9 ± 15.0 | 0.309 |

| 1-Month CGM use (%) | 68.8 ± 22.2 | 90.7 ± 7.6 | 75.7 ± 21.4 | <0.001 |

| 1-Month time in Auto Mode (%) | 57.5 ± 25.8 | 83.9 ± 11.1 | 65.7 ± 25.4 | <0.001 |

| 1-Month TIR (%) | 56.3 ± 12.7 | 69.4 ± 11.4 | 60.4 ± 13.5 | <0.001 |

| 1-Month boluses per day (no.) | 5.9 ± 2.5 | 7.4 ± 2.2 | 6.4 ± 2.5 | 0.015 |

| 3-Month CGM use (%) | 53.0 ± 29.0 | 83.5 ± 14.7 | 63.3 ± 28.8 | <0.001 |

| 3-Month time in Auto Mode (%) | 38.3 ± 28.2 | 75.9 ± 18.4 | 51.0 ± 30.9 | <0.001 |

| 3-Month TIR (%) | 54.1 ± 16.2 | 68.3 ± 10.3 | 59.4 ± 15.8 | <0.001 |

| 3-Month boluses per day (no.) | 5.2 ± 2.1 | 7.2 ± 1.9 | 5.9 ± 2.2 | <0.001 |

FIG. 1.

Predictive model with BDC data and prognostic parameters. (A) Model development with 1-month predictors. (B) Model development with 3-month predictors. BDC, Barbara Davis Center for Childhood Diabetes.

Using the 1-month data within the complete model (Fig. 1A), each 1% increase above average baseline HbA1c was associated with 24% reduced odds of HCL success. Each 10% increase above average time in Auto Mode at 1 month was associated with 80% increased odds of HCL success and each 10% increase above average TIR was associated with 50% increased odds of HCL success. Each additional bolus per day was associated with 14% increased odds of HCL success. Male sex was associated with a 3.82-fold (282%) increased odd of success compared to female sex, although with wide 95% confidence interval of 0.98 to 17.68 (−2% to 1,668%).

The Hispanic ethnicity was associated with 50% greater odds of HCL success when compared with those who did not identify as Hispanic. The same variables were retained by Lasso in the 3-month model as in the 1-month model (Fig. 1B). The final model formula is as follows, with p representing the odds of success. Beta coefficients are presented in Figure 1.

Assessment of diabetes distress via the PAID score did not demonstrate significant differences on univariate analysis between the HCL failure and HCL success groups for either the Child or Young Adult questionnaires. Assessment of hypoglycemia worry via the HFS Worry score did not demonstrate significant differences on univariate analysis between the HCL failure and HCL success groups for either the Child or Young Adult questionnaires. Neither the PAID nor the HFS scores were retained by Lasso in model development.

External validation of the prognostic model

The Stanford validation sample consisted of 55 participants, age 26.5 ± 14.4 years with type 1 diabetes duration of 14.4 ± 10.2 years and mean baseline HbA1c of 8.1% ± 1.5% (Table 1). Within this cohort, 58.2% of participants were male. Race, ethnicity, and insurance status were similar to the development sample. At the final follow-up visit, 28 participants (50.9%) were in the Auto Mode failure group with mean Auto Mode use of 8.7% ± 16.2% while 27 participants (49.1%) were in the Auto Mode success group with mean Auto Mode use of 82.1% ± 11.5%.

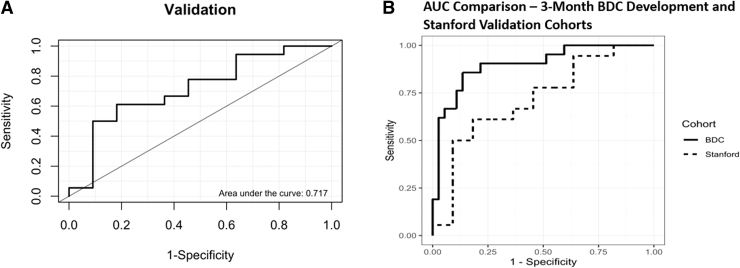

The area-under-the-curve for the external validation of the model using the 3-month data was acceptable at 0.717 (Fig. 2A). Comparison of the 3-month development and validation cohort AUC values is presented in Figure 2B.

FIG. 2.

Validation of predictive model with Stanford data using 3-month predictors. (A) Validation model area under the curve. (B) Area under the curve comparison between the BDC development cohort and Stanford validation cohort.

Discussion

This study describes the development and validation of prognostic models for successful use of a first-generation HCL system in real-world patients with type 1 diabetes. The model uses commonly available patient characteristics and device metrics, which allows for ready translation to clinical diabetes care. The model demonstrates good predictive ability using either 1- or 3-month data to evaluate 12-month success and was validated using an external sample. The model can thus be used with the earliest available clinical data to identify HCL users who are less likely to be successful using their new HCL system. A clinician could use a web-based application of this model with already present clinical data to identify patients at higher risk for HCL discontinuation and then allocate training and follow-up resources based on this prediction.

The prognostic model included the predictors of HbA1c, Auto Mode use, TIR, boluses per day, sex, and ethnicity. Data-driven inclusion of each of these metrics also makes sense from a mechanistic evaluation of what they represent in the context of type 1 diabetes care. HbA1c was associated with Auto Mode use in a 670G observational study by Akturk et al.33 and patients with the highest baseline HbA1c values had the greatest improvement in HbA1c with successful use of HCL.14 However, they were also the most likely to discontinue HCL use across time.14

The 1- or 3-month Auto Mode use effectively being predictive of 12-month Auto Mode use suggests that behaviors indicating successful device use across time are already present within the first few months of using a new system. The 1- or 3-month TIR likely serves as a mixture of baseline control and successful device use during the first few months. The number of boluses per day predicting 12-month Auto Mode use likely combines several factors. Increased manual bolusing likely correlates with increased engagement with diabetes care. The Auto Mode exits from too much basal delivery would also be reduced for the 670G with increased user-initiated boluses.

An interesting demographic finding was that males demonstrated about a fourfold better odds of Auto Mode success in the development cohort, while females demonstrated better success in the validation cohort. It is possible that this effect was age mediated. The interaction term for sex and age was not significant in subanalysis, although these analyses may have been underpowered to evaluate for this effect. It is notable that the 95% confidence intervals for both the 1- and 3-month models were very wide suggesting higher uncertainty around this predictor. While some observers may suggest removing the sex term from the model based on the discrepancy between its trend in the development and validation samples, such a change would violate the assumptions of the Lasso model development and contaminate the independence of the separate development and validation samples.

It is particularly notable that 670G users of Hispanic ethnicity had higher odds of HCL success compared with those not of Hispanic ethnicity. Type 1 diabetes exchange data have demonstrated lower rates34–36 of technology use among racial and ethnic minorities within the United States. It has been hypothesized that provider bias may be a driver of these disparities if providers do not believe that a certain group of patients is a “good candidate” for a given technology. This finding that Hispanic ethnicity is associated with improved odds of success with the 670G system further supports the growing body of evidence that device use should be promoted among groups currently under-utilizing type 1 diabetes technologies.

A number of hypothesized predictors did not strengthen the predictive value of the model. These included duration of diabetes, age, race, insurance status, prior history of pump use, and history of CGM use. It is possible that some of these factors were underpowered for inclusion in this analysis or that there is truly no effect between them and HCL success. It is nevertheless noteworthy that subjects with public insurance (primarily Medicaid) or from non-white backgrounds did not have increased odds of HCL failure. While these measures may have been underpowered, this finding argues for continued expansion of advanced technology use among the public insurance and minority patient groups with type 1 diabetes despite these groups traditionally having lower rates of technology use.1

Indeed, findings from a recent comparison between United States and European registry data demonstrate that technology use is at its lowest and HbA1c at its highest among the lowest socioeconomic groups, a finding which is worse in the United States than in Europe.35 It is also notable that duration of type 1 diabetes was not an included predictor for HCL success. Had patients with shorter diabetes duration been more likely to succeed with HCL, there may be concern that established habits get in the way of novel technology. Had patients with longer duration of diabetes been more likely to succeed, there may be concern that a certain duration of diabetes was necessary for HCL initiation.

Essentially all the participants in both cohorts had >6-month history of pump use, which limits the generalizability of this predictor. Most participants also had a history of prior CGM use, which is not reflective of the general diabetes population. As many participants used other CGM systems before starting the 670G, we were unable to capture the percent CGM use before beginning this system. It is notable, however, that practice patterns are changing with earlier introduction of CGM and HCL systems. The methods used in this analysis may be applied in the future to newer and emerging HCL systems.

We had also hypothesized that participants’ diabetes distress, as measured by the PAID score, and hypoglycemia fear scores, as measured by the HFS worry score, would be predictive of success with HCL. As HCL systems significantly lower hypoglycemia exposure, we hypothesized that participants with greater baseline HFS worry scores would see greater benefit from the technology and thus have higher rates of HCL success. Due to the burden associated with use of a first-generation HCL system, we hypothesized that participants with higher baseline diabetes distress would have lower rates of HCL success. That neither metric was included in the model may indicate that these existing tools do not capture proper characteristics for device use.

The splitting of the sample between PAID and PAID-peds tools, which are not able to be combined into a single measure for both age groups, could have also resulted in this measure being underpowered for both the adult and pediatric age groups. More technology-directed tools such as the INSPIRE measure will be evaluated in a future study.37

The identification of baseline and 1-month factors as predictors of 12-month HCL success establishes the necessary foundation for future implementation of approaches to promote HCL success. We would not advocate selecting certain populations for use of HCL and not “allowing” other populations access to advanced technologies. As demonstrated by the HbA1c predictive data, it appears that the greatest glycemic improvement is seen by the patients most likely to discontinue HCL. Beyond that, we can identify those individuals not achieving optimal HCL success within the first month (either as poor Auto Mode use or lower TIR) are those likely to disengage with the system by 1 year. This knowledge allows for implementation of additional educational, problem solving, or behavioral interventions to promote device success.

Such work will be the future of this study group as well as other investigations across the field. In particular, the next stage of this grant is investigating use of adapted behavioral family systems therapy to improve use of newer generation HCL systems.38 To help inform such efforts, we have developed a web-based application of these models, which allows users to input either 1- or 3-month data, depending on what is available. The application can be accessed through our team's website (https://bdcpantherdiabetes.org/). Different models will be developed for other HCL designs as we expect that predictors of success with the first generation HCL system (the 670G) will differ from those associated with success of subsequent HCL designs.

While no model has previously been developed for predictive success with HCL systems, other work has investigated prediction of use of diabetes technologies. A 2015 study by Neylon looked at use of a questionnaire-based tool to predict recommended usage of insulin pumps, CGMs, and sensor augmented pump (SAP) therapy.39 They found that male gender, lower baseline HbA1c, and two questionnaire items for blood sugar testing conflict were highly predictive of both pump and CGM success. Earlier work by this group investigated predictors of lower self-care and worse metabolic control and identified multiple-demographic, interpersonal, intrapersonal, and technology-specific factors as predictors.40 While gender was not identified in this analysis, number of blood glucose tests per day was identified as a technology-specific predictor.

Strengths of the study include the relatively large population of HCL users in both the development and validation cohorts, the 1-year follow-up period for both groups, and the robust methods of model development and validation. This study has notable weaknesses as well. The development cohort and validation cohort data were both generated at academic medical centers involved with development of the system under study and thus may have a higher degree of familiarity with the device than would be expected at other sites. Both centers utilized expert training and provider review of device settings before and shortly after starting the new system.

The amount of prior pump and CGM use in the populations studied was much higher than would be expected in the general T1D population. The development sample consisted of primarily children, while the validation sample consisted of primarily adults with an average age difference of +12.3 years for the validation cohort. Given this potential bias, it is reassuring that the validation cohort had such a large agreement with the development cohort.

The model was developed for the first generation HCL system with the original sensor algorithm. Given the large differences in system design between the 670G and newer and emerging systems, it seems very unlikely that this exact model will predict success for future system designs as these systems may provide automated correction boluses, use sensors that do not require calibration, and have a much lower rate of alarms and being “kicked out” of Auto Mode. The absence of automated correction boluses was very important for those with elevated glucose levels. For some participants, the burden of diabetes care was increased, not decreased, when using this system.

It was therefore not surprising that those entering the study with high HbA1c levels, who were already suboptimally performing diabetes tasks, had a higher failure rate when asked to do the additional tasks to keep this system functioning. Despite the differences between the design of this system and the designs of future systems, there are still several major lessons from this model. The most notable is that technology-use at 1 month was predictive of use at 12 months. This finding indicates that clinicians may wish to target aspects of subideal use (e.g., Auto Mode use and boluses per day), which can be identified early in the device-use history.

As new systems are developed and released, it will be important to reassess the definition of “successful system use.” Users may have their own goals and definitions for subjective success such as reduction in nocturnal alarms or reduced diabetes-related stress. Clinicians and payers are likely to have other glycemic-focused goals (e.g., meeting consensus targets for TIR, HbA1c, or some other consensus metric). Predictors of these different forms of success with future systems will require models specific to those goals and system designs. It may well be that those with the highest HbA1c levels will be the most successful as their diabetes tasks are decreased, and those with the lowest HbA1c levels may have difficulty letting go of their diabetes management to an external controller. Validation with future cohorts with newer generations of the technology will therefore be necessary.

Patients with high HbA1c levels should not be excluded from these systems since they may very well receive the biggest benefit and have sustained use of the systems. In fact, recent analysis of the Tandem Control-IQ system real-world data by Breton demonstrated sustained 95% time in automation over 12 months with this system.41 Further analysis of these data demonstrated large improvements in glycemic control for those with the highest baseline HbA1c values.42 Similar findings have been reported by our group for the 670G system when stratifying by baseline HbA1c.14 Despite these excellent findings for this system, almost half of users are still not seeing a TIR of greater than 70%. Thus, even next-generation systems may require additional supports to achieve optimal glycemic control.

Conclusion

In conclusion, a prognostic model is now available to assess the chances of successful use of the Medtronic 670G HCL technology at 12 months based on baseline and 1-month data. This prognostic model may be useful for tailoring interventions for individuals beginning technologies to promote long-term device success. Identification of persons requiring support to promote device success may help optimize provider resources and maximize improvements in diabetes care across a wide spectrum of patients.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the youth with type 1 diabetes and caregivers who participated in this study. We acknowledge Emily Boranian, Samantha Lange, Katelin Thivener, and Maria Rossick-Solis who assisted in recruitment and questionnaire administration for this study. The Stanford team thanks Saniya Kishnani for setting up the REDCap data collection system; Ruth Wu for performing data collection; Karen Barahona and Nora Arrizon-Ruiz for recruitment; the clinical diabetes educators for teaching and tracking pediatric patients: Barry Conrad, Jeannine Leverenz, Kristine Peterson, and Annette Chmielewski (all from Division of Endocrinology, Department of Pediatrics, Stanford University School of Medicine); and the adult endocrine nurse practitioners and diabetes educators Kathleen Judge and Leticia Wilke (Division of Endocrinology, Department of Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine). The REDCap platform services are made possible by the Stanford University School of Medicine Research Office.

Authors’ Contributions

G.P.F. wrote the article, assisted with data analysis, wrote the protocol, and obtained funding for the project. T.V. performed the data analysis, generated the tables and figures, and assisted with developing the article. C.B., L.H.M., R.P.W., K.A.D., and L.P. provided advice and feedback on the protocol, grant, data gathering, data analysis, and article development. R.P.W., K.A.D., and L.P. provided mentorship on the career development award. C.B. and L.H.M. were responsible for gathering the data and previous analysis of the data from this work.

For the Stanford data, R.A.L. provided the data used in this analysis. R.A.L, M.B., D.M.M., K.H., and B.B. helped recruit participants and reviewed and edited the article. R.A.L., M.B., D.M.M., K.H., B.B., and D.M.W. assisted in study design. D.M.W. wrote the original protocol, obtained Institutional Review Board approval, wrote the article, and reviewed and edited the article.

Author Disclosure Statement

G.P.F. has research funding from Medtronic, Dexcom, Abbott, Tandem, Insulet, Lilly, and Beta Bionics and has been a speaker/consultant/advisory board member for Medtronic, Dexcom, Abbott, Tandem, Insulet, Lilly, and Beta Bionics. L.H.M. has received speaking/consulting honoraria from Dexcom, Tandem, Clinical Sensors and Capillary Biomedical, and is a contracted trainer for Medtronic Diabetes. R.A.L. consults for Abbott Diabetes Care, Biolinq, Capillary Biomedical, Deep Valley Labs, Morgan Stanley, ProventionBio and Tidepool. D.M.M. has had research support from the NIH, JDRF, NSF, and the Helmsley Charitable Trust and his institution has had research support from Medtronic Diabetes, Dexcom, Insulet, Bigfoot Biomedical, Tandem, and Roche. D.M.M. has also consulted for Abbott, the Helmsley Charitable Trust, Sanofi, Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, Medtronic, and Insulet. K.H. has research support from Dexcom and consultant fees from Lifescan Diabetes Institute, Cecelia Health, and Cercacor. B.B. is on medical advisory boards for Convatec, Medtronic, and Tolerion, Inc., and has received research support from Medtronic, Tandem, Insulet Corporation, Dexcom, NIH (DP3-DK-104059, DP3 DK-101055, and DK-14024), Helmsley Charitable Trust, and JDRF. D.M.W. is on the advisory board for Tolerion, Inc., and has received research support from Dexcom, JDRF, and the NIH. R.P.W. has received research funding from Tandem, Dexcom, Eli Lilly, MannKind and the NIH and received honoraria from Tandem and Eli Lilly. The other authors report no duality of interest.

Funding Information

This research was supported by an NIH NIDDK K12 Award (K12DK094712) and a JDRF early career patient-oriented diabetes research award (5-ECR-2019-736-A-N) awarded to Dr. Forlenza. D.M.M. was supported by P30DK116074. R.A.L. was supported by the NIDDK (T32 DK007217, 1K12 DK122550, 1K23 DK122017) and Stanford Maternal and Child Health Research Institute.

References

- 1. Foster NC, Beck RW, Miller KM, et al. : State of type 1 diabetes management and outcomes from the T1D exchange in 2016–2018. Diabetes Technol Ther 2019;21:66–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Miller KM, Foster NC, Beck RW, et al. : Current state of type 1 diabetes treatment in the U.S.: updated data from the T1D exchange clinic registry. Diabetes Care 2015;38:971–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brown SA, Kovatchev BP, Raghinaru D, et al. : Six-month randomized, multicenter trial of closed-loop control in type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2019;381:1707–1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Garg SK, Weinzimer SA, Tamborlane WV, et al. : Glucose outcomes with the in-home use of a hybrid closed-loop insulin delivery system in adolescents and adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 2017;19:155–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bergenstal RM, Garg S, Weinzimer SA, et al. : Safety of a hybrid closed-loop insulin delivery system in patients with type 1 diabetes. JAMA 2016;316:1407–1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Forlenza GP, Pinhas-Hamiel O, Liljenquist DR, et al. : Safety evaluation of the MiniMed 670G system in children 7–13 years of age with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 2019;21:11–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Weisman A, Bai JW, Cardinez M, et al. : Effect of artificial pancreas systems on glycaemic control in patients with type 1 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of outpatient randomised controlled trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2017;5:501–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brown SA, Beck RW, Raghinaru D, et al. : Glycemic outcomes of use of CLC versus PLGS in type 1 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2020;43:1822–1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sherr J, Buckingham BA, Forlenza G, et al. : Safety and performance of the Omnipod hybrid closed-loop system in adults, adolescents, and children with type 1 diabetes over 5 days under free-living conditions. Diabetes Technol Ther 2020;22:174–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bekiari E, Kitsios K, Thabit H, et al. : Artificial pancreas treatment for outpatients with type 1 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2018;361:k1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tauschmann M, Thabit H, Bally L, et al. : Closed-loop insulin delivery in suboptimally controlled type 1 diabetes: a multicentre, 12-week randomised trial. Lancet 2018;392:1321–1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Benhamou PY, Franc S, Reznik Y, et al. : Closed-loop insulin delivery in adults with type 1 diabetes in real-life conditions: a 12-week multicentre, open-label randomised controlled crossover trial. Lancet Digit Health 2019;1:e17–e25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Saunders A, Messer LH, Forlenza GP: MiniMed 670G hybrid closed loop artificial pancreas system for the treatment of type 1 diabetes mellitus: overview of its safety and efficacy. Expert Rev Med Devices 2019;16:845–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Berget C, Messer LH, Vigers T, et al. : Six months of hybrid closed loop in the real-world: an evaluation of children and young adults using the 670G system. Pediatr Diabetes 2020;21:310–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lal RA, Basina M, Maahs DM, et al. : One year clinical experience of the first commercial hybrid closed-loop. Diabetes Care 2019;42:2190–2196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Messer LH, Berget C, Vigers T, et al. : Real world hybrid closed loop discontinuation: predictors and perceptions of youth discontinuing the 670G system in the first 6 months. Pediatr Diabetes 2020;21:319–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Berget C, Akturk HK, Messer LH, et al. : Real world performance of hybrid closed loop in youth, young adults, adults and older adults with type 1 diabetes: identifying a clinical target for hybrid closed loop use. Diabetes Obes Metab 2021;23:2048–2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gonder-Frederick L, Nyer M, Shepard JA, et al. : Assessing fear of hypoglycemia in children with Type 1 diabetes and their parents. Diabetes Manag (Lond) 2011;1:627–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Polonsky WH, Hessler D, Ruedy KJ, Beck RW: The impact of continuous glucose monitoring on markers of quality of life in adults with type 1 diabetes: further findings from the DIAMOND randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Care 2017;40:736–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Haugstvedt A, Wentzel-Larsen T, Aarflot M, et al. : Assessing fear of hypoglycemia in a population-based study among parents of children with type 1 diabetes—psychometric properties of the hypoglycemia fear survey—parent version. BMC Endocr Disord 2015;15:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gonder-Frederick LA, Schmidt KM, Vajda KA, et al. : Psychometric properties of the hypoglycemia fear survey-ii for adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2011;34:801–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Welch G, Weinger K, Anderson B, Polonsky WH: Responsiveness of the problem areas in diabetes (PAID) questionnaire. Diabet Med 2003;20:69–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Polonsky WH, Anderson BJ, Lohrer PA, et al. : Assessment of diabetes-related distress. Diabetes Care 1995;18:754–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Markowitz JT, Volkening LK, Butler DA, et al. : Re-examining a measure of diabetes-related burden in parents of young people with type 1 diabetes: the problem areas in diabetes survey—parent revised version (PAID-PR). Diabet Med 2012;29:526–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Markowitz JT, Volkening LK, Butler DA, Laffel LM: Youth-perceived burden of type 1 diabetes: problem areas in diabetes survey-pediatric version (PAID-Peds). J Diabetes Sci Technol 2015;9:1080–1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Berget C, Thomas SE, Messer LH, et al. : A clinical training program for hybrid closed loop therapy in a pediatric diabetes clinic. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2019:1932296819835183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Messer LH, Forlenza GP, Sherr JL, et al. : Optimizing hybrid closed-loop therapy in adolescents and emerging adults using the MiniMed 670G system. Diabetes Care 2018;41:789–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Battelino T, Danne T, Bergenstal RM, et al. : Clinical targets for continuous glucose monitoring data interpretation: recommendations from the international consensus on time in range. Diabetes Care 2019;42:1593–1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Danne T, Nimri R, Battelino T, et al. : International consensus on use of continuous glucose monitoring. Diabetes Care 2017;40:1631–1640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tibshirani R: Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. J R Stat Soc Ser B Methodol 1996;58:267–288. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Friedman J, Hastie T, Tibshirani R: Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent. J Stat Softw 2010;33:1–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Safari S, Baratloo A, Elfil M, Negida A: Evidence based emergency medicine; part 5 receiver operating curve and area under the curve. Emerg (Tehran) 2016;4:111–113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Akturk HK, Giordano D, Champakanath A, et al. : Long-term real-life glycaemic outcomes with a hybrid closed-loop system compared with sensor-augmented pump therapy in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2020;22:583–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Addala A, Hanes S, Naranjo D, et al. : Provider implicit bias impacts pediatric type 1 diabetes technology recommendations in the United States: findings from the gatekeeper study. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2021:19322968211006476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Addala A, Auzanneau M, Miller K, et al. : A decade of disparities in diabetes technology use and HbA(1c) in pediatric type 1 diabetes: a transatlantic comparison. Diabetes Care 2021;44:133–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Miller KM, Beck RW, Foster NC, Maahs DM: HbA1c levels in type 1 diabetes from early childhood to older adults: a deeper dive into the influence of technology and socioeconomic status on HbA1c in the T1D exchange clinic registry findings. Diabetes Technol Ther 2020;22:645–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Weissberg-Benchell J, Shapiro JB, Hood K, et al. : Assessing patient-reported outcomes for automated insulin delivery systems: the psychometric properties of the INSPIRE measures. Diabet Med 2019;36:644–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wysocki T, Harris MA, Buckloh LM, et al. : Randomized, controlled trial of behavioral family systems therapy for diabetes: maintenance and generalization of effects on parent-adolescent communication. Behav Ther 2008;39:33–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Neylon OM, Skinner TC, O'Connell MA, Cameron FJ: A novel tool to predict youth who will show recommended usage of diabetes technologies. Pediatr Diabetes 2016;17:174–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Neylon OM, O'Connell MA, Skinner TC, Cameron FJ: Demographic and personal factors associated with metabolic control and self-care in youth with type 1 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2013;29:257–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Breton MD, Kovatchev BP: One year real-world use of the control-IQ advanced hybrid closed-loop technology. Diabetes Technol Ther 2021;23:601–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Forlenza GP, Breton MD, Kovatchev B: Candidate selection for hybrid closed loop systems. Diabetes Technol Ther 2021;23:760–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]