Abstract

Background:

For faculty in academic health sciences, the balance between research, education, and patient care has been impeded by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. This study aimed to identify personal and professional characteristics of faculty to understand the impact of the pandemic on faculty and consequent policy implications.

Methods:

A 93-question survey was sent to faculty at a large urban public university and medical center. Demographic, family, and academic characteristics, work distribution and productivity before and during the pandemic, stress, and self-care data information were collected. Latent class analysis (LCA) was performed to identify classes of faculty sharing similar characteristics. Comparisons between latent classes were performed using analysis of variance and chi-square analyses.

Results:

Of 497 respondents, 60% were women. Four latent classes of faculty emerged based on six significant indicator variables. Class 1 individuals were more likely women, assistant professors, nontenured with high work and home stress; Class 2 faculty were more likely associate professors, women, tenured, who reported high home and work stress; Class 3 faculty were more likely men, professors, tenured with moderate work, but low home stress; and Class 4 faculty were more likely adjunct professors, nontenured, and had low home and work stress. Class 2 reported significantly increased administrative and clinical duties, decreased scholarly productivity, and deferred self-care.

Conclusions:

The pandemic has not affected faculty equally. Early and mid-career individuals were impacted negatively from increased workloads, stress, and decreased self-care. Academic leaders need to acknowledge these differences and be inclusive of faculty with different experiences when adjusting workplace or promotion policies.

Keywords: academic faculty, COVID-19 pandemic, work–life balance, health sciences, gender, latent class analysis

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has led to a significant and unprecedented disruption of all facets of our lives.1 Academic faculty were directly affected by the stay-at-home order, impacting research work, teaching, and service responsibilities, thereby altering any balance of work–life previously achieved.2 For many academic faculty in the health sciences, work demands shifted away from research to accommodate remote instruction and clinical care.

Several studies have documented the loss in scholarly productivity by women faculty in academia during the pandemic.3,4 Within 4 months of the pandemic, the proportion of female to male authorship in medical journals dropped, the gap increased from 23% to 55%.3 Women faculty with young children reported a decrease in first author submissions compared to the period before the pandemic; men reported no change in scholarly metrics.4 DeGruyter reported that 57% of academic book and journal authors reported spending less time on primary research than expected (2020).5

Yet, some subgroups of faculty in the health sciences experienced increased academic productivity during the pandemic.6,7 For example, original submissions to neurosurgery, stroke neurology, and neurointerventional surgery journals increased by 43% in 2020, suggesting some shifts in workload during the pandemic led to more time for scholarship for some academics.7

During the pandemic, many academic faculty in the health sciences faced a change in research productivity and the added stress. Nearly 70% of US faculty reported feeling stressed in 2020 compared to 32% in 2019.8 During the pandemic, academic faculty, particularly those with caregiver responsibilities, were more likely to consider reducing their hours or leaving the workforce.6 They were also required to shift their “work-work balance” between education, research, and patient care and were more likely to worry about career trajectory.6.9,10 Frontline health care workers experienced more stress and burnout than did those not caring for patients with COVID-19.11,12 Persistent job stress can lead to less engagement with activities of self-care such as exercise and sleep that help with recovery.13

The effect of the pandemic on health sciences faculty has been extremely heterogeneous, making policy decision-making challenging. Academic policy makers have focused primarily on gender to address inequities, yet same gender faculty have differentially been impacted in terms of scholarly productivity. Other characteristics may also play a role. Our goal was to explore patterns in faculty characteristics that impact scholarly productivity and stress to provide insights to academic and clinical decision makers.

Methods

Study design

A cross-sectional survey was conducted among faculty at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC), a large urban public university, comprising 16 academic schools and colleges. Faculty from the health sciences (Applied Health Sciences, Dentistry, Medicine, Nursing, Pharmacy, Public Health, and Social Work) completed an online survey of 93 questions through faculty university listservs. Email invitations and reminders were sent four times between September and November 2020. The study was deemed exempt by the UIC Office for the Protection of Research Subjects.

Survey instrument

The survey collected information on demographic and academic characteristics, and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on work and home life. Change in work productivity and stress level was assessed using eight questions adapted from the Association of American Universities Data Exchange (AAUDE) Faculty Survey.14 The pandemic-related questions were adapted from the New York Times National Survey Division of Labor with permission from Morning Consult (Chicago, IL).15 Stress associated with home activities, housework, care of children or others, personal health, and financial obligations, as well as changes in sleep, diet, exercise, use of mental health services, and emotional social support were assessed. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at UIC.16,17

Analyses

Respondents who were not faculty, those who did not indicate rank or gender, and those who completed less than 50% of the survey were excluded from analyses. Sex was used as a proxy if respondents did not indicate their gender (n = 3). Surveys with missing responses to stress questions (n = 14) were omitted from latent class analysis (LCA). To ensure anonymity, affiliation data were collected at the College level and any demographic group with fewer than five responses was merged into a larger category. The general characteristics of the respondents were compared to those of the overall faculty population at our institution, which are publicly available.18

Descriptive analyses

Responses to stress-related questions were recorded on a 5-item Likert scale (Supplementary Table S1). Responses of “Much more stressful” or “More stressful” were coded as 1, while any other response, including “Non-Applicable,” was coded as 0. These values were summed into composite work stress and home stress scores derived from 8 statements related to work activities (range 0–8) and 5 statements related to home activities (range 0–5).

Individuals with composite stress scores of 0 to 1 were considered “low stress.” Those with composite scores of ≥2 (i.e., two or more responsibilities reported as “more stressful”) were considered “high stress” for work- or home-related stress, respectively. These cutoffs were the result of a receiver operating curve analysis and were the ones for which statistical differences between women and men were maximal.

The distributions of personal, family, and professional characteristics are presented as frequencies and compared by chi-square tests between faculty by gender. Median stress levels are presented as violin plots and differences analyzed by Mann–Whitney rank sum test. Data were analyzed using SAS 9.4 software (Cary, NC). p-Values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Bayesian latent class analysis

LCA was performed using Latent Gold (v.5.1, Statistical Innovations, Arlington MA).19,20 Dichotomized stress indicators were entered along with gender, academic rank, having children 12 years of age and younger, and tenure status, into the LCA with 1–5 class models. Academic rank was grouped into five categories: lecturer/instructor, assistant professor, associate professor, professor, and adjunct/visiting. Tenure status was classified as tenured, not tenured, but on tenure track, and not on tenure track. LCA models were assessed for fit using the following indices: Bayesian information criterion, Akaike Information Criterion, and log likelihood.21

The relative time dedicated to different work activities (education, research, and clinical) was described by percent full time equivalent. These time allocations were compared among respondents by their latent class assignment using analysis of variance with post hoc Tukey testing. Chi-square test was used to compare the distribution of respondents' perceived change in week-work time allocation, self-care, positive and negative aspect of education, research, and clinical productivity during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Results

Respondent characteristics

Of the 562 respondents, 65 were excluded, leaving 497 respondents for analysis (Fig. 1). The summary of the respondents' personal, family, and professional characteristics is shown in Table 1. The majority of respondents self-identified as women (60%), white (79%), and married and/or cohabiting (79%). Women respondents were younger (median age: 46 years) than men (54 years). More women were either childless or had only one child in the household (59%) than men who most often lived in households with two children (41%). More women were assistant professors (41% vs. 21% for men), while only 17% were professors (vs. 34% men). More women were not on the tenure track (60% vs. 53% for men) and fewer were tenured (29% vs. 39% for men).

FIG. 1.

Flow chart of respondents with inclusions and exclusions. Of the 562 respondents, 4 did not indicate their sex or gender, and 5 had incomplete surveys, and were excluded. An additional 56 respondents were excluded due to nonfaculty status, leaving 497 respondents included in our statistical analyses. Of these, 299 (60%) were women and 198 (40%) were men. The Bayesian LCA was conducted on surveys from 483 faculty due to exclusion of 14 respondents who did not fully complete the stress questions. LCA, latent class analysis.

Table 1.

Baseline Personal, Family, and Professional Characteristics Stratified by Gender for the Total Analytical Sample (n = 497)

| Characteristic | Total n = 497 | Women n = 299 | Men n = 198 | ANOVA or chi square p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yearsb | 49 [40–61] | 46 [38–58] | 54 [43–65] | <0.001 |

| Racec,d | ||||

| Black | 21 (4.2) | 17 (5.7) | 4 (2.0) | 0.157 |

| White | 392 (78.9) | 231 (77.3) | 161 (81.3) | |

| Asian | 49 (9.9) | 28 (9.4) | 21 (10.6) | |

| Othere | 32 (6.5) | 22 (7.4) | 10 (5.1) | |

| Ethnicityc,d | ||||

| Hispanic | 39 (7.9) | 23 (7.8) | 16 (8.1) | 0.887 |

| Non-Hispanic | 454 (92.1) | 273 (92.2) | 181 (91.9) | |

| Marital statusc,d | ||||

| Single | 58 (11.7) | 39 (13.0) | 19 (9.6) | 0.221 |

| Married or cohabitating | 394 (79.3) | 229 (76.6) | 165 (83.3) | |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 41 (8.3) | 28 (9.5) | 13 (6.6) | |

| Spouse/partner is a frontline or essential workerc,d | ||||

| Yes | 87 (17.5) | 46 (15.4) | 41 (20.7) | 0.261 |

| No | 307 (61.8) | 183 (61.2) | 124 (62.6) | |

| Number of children in householdc,d | ||||

| No child | 166 (33.4) | 112 (37.4) | 54 (27.3) | <0.001 |

| 1 child | 80 (16.1) | 63 (21.1) | 17 (8.6) | |

| 2 children | 170 (34.2) | 89 (29.8) | 81 (40.9) | |

| 3 children | 52 (10.5) | 23 (7.7) | 29 (14.6) | |

| 4+ children | 23 (4.6) | 10 (3.3) | 13 (6.6) | |

| Age range of youngest childc | ||||

| 0–4 years | 82 (16.5) | 54 (18.1) | 28 (14.1) | 0.168 |

| 5–12 years | 73 (14.7) | 41 (13.7) | 32 (16.2) | |

| 13–17 years | 42 (8.5) | 26 (8.7) | 16 (8.1) | |

| 18–23 years | 40 (8.0) | 19 (6.3) | 21 (10.6) | |

| 24 years or older | 83 (16.7) | 41 (13.7) | 42 (21.2) | |

| No children in household or no response | 177 (35.6) | 118 (39.5) | 59 (29.8) | |

| Currently caring for or managing care for an aging and/or ill parent, spouse/partnerc,d | ||||

| Yes | 86 (17.3) | 59 (19.7) | 27 (13.6) | 0.083 |

| No | 410 (82.5) | 240 (80.3) | 170 (85.9) | |

| Current rankc | ||||

| Lecturer/instructor | 39 (7.9) | 25 (8.4) | 14 (7.1) | <0.001 |

| Assistant professor | 163 (32.8) | 121 (40.5) | 42 (21.2) | |

| Associate professor | 131 (26.4) | 78 (26.1) | 53 (26.8) | |

| Professor | 120 (24.1) | 52 (17.4) | 68 (34.3) | |

| Adjunct/visiting | 44 (8.9) | 23 (7.7) | 21 (10.6) | |

| Tenured statusc,d | ||||

| Tenured | 162 (32.6) | 84 (28.1) | 78 (39.4) | 0.016 |

| On tenure track, not tenured | 49 (9.9) | 35 (11.7) | 14 (7.1) | |

| Not on tenure track | 284 (57.1) | 179 (59.9) | 105 (53.0) | |

| Full time statusc,d | ||||

| Yes | 405 (81.5) | 247 (82.6) | 158 (79.8) | 0.384 |

| No | 91 (18.3) | 51 (17.1) | 40 (20.2) | |

| Degree(s)c,d | ||||

| Clinical degreef | 141 (28.4) | 85 (28.4) | 56 (28.3) | 0.863 |

| Nonclinical degree onlyg | 333 (67.1) | 201 (67.4) | 132 (66.7) | |

| Dual degreeh | 22 (4.4) | 12 (4.0) | 10 (5.1) | |

| School/college of primary appointmentc,d | ||||

| Applied health sciences and public health | 38 (7.7) | 29 (9.8) | 9 (4.5) | 0.049 |

| Dentistry, nursing, pharmacy | 66 (13.3) | 42 (14.1) | 24 (12.1) | |

| Medicine | 231 (46.7) | 141 (47.5) | 90 (45.4) | |

| Social work or other college | 160 (32.3) | 85 (28.6) | 75 (37.9) | |

p-values <0.05 are shown in bold font.

Data shown as median [interquartile range] and analyzed by Mann Whitney rank sum test.

Data shown as n (%) and analyzed by chi square test.

Totals do not add up due to missing values.

Includes Native American or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander.

Clinical degree: DDS, DMD, DO, MD, or PharmD.

Nonclinical degree: PhD, DrPH, EdD, or any master's degree or other degree.

Dual degree: Clinical degree plus a PhD or masters.

ANOVA, analysis of variance.

There was no difference in the proportions of men and women who had a spouse/partner as a frontline or essential worker, cared for an aging or ill family member, worked full time, or had advanced clinical degrees. Compared to general faculty characteristics at our academic institution, the surveyed sample had a higher representation of women (60% vs. 48%) and a lower representation of tenure-track faculty (10% vs. 14%).

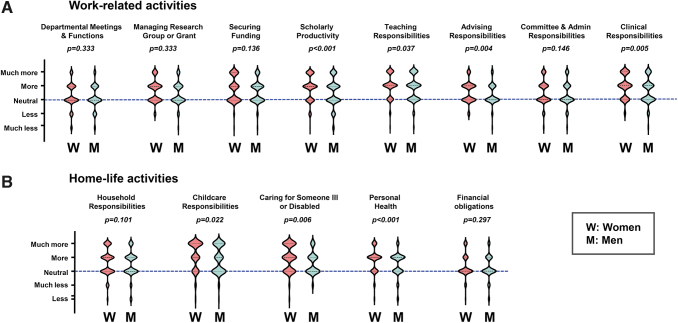

Most faculty reported increases in stress levels during the pandemic, with 73% of faculty classified as “high stress” for work-related activities and 60% as “high stress” for home-life activities (Supplementary Table S2 and Supplementary Fig. S1). Women reported more stress than men with respect to scholarly productivity, teaching, advising, and clinical responsibilities (Fig. 2A). There were no significant differences reported related to stress from department meetings, managing a research group or grant, or securing research funding. Women reported more stress with respect to childcare, other dependent responsibilities, and their personal health (Fig. 2B). There were no differences by gender with respect to managing household responsibilities or financial obligations.

FIG. 2.

Violin plots showing the distribution in respondents by change in stress level compared to prepandemic period for (A) eight work-related and (B) five home-life related activities. The contour of the plots represents the probability density function computed using the kernel density estimation (KDE) method. The interrupted line represents neutrality—no change in stress level from before the COVID pandemic. COVID, coronavirus disease.

Latent class analysis for shared pattern extraction

A four-class model was identified as the most parsimonious solution compared to one-, two-, three-, and five-class models (for details, see Supplementary Table S3). The significant indicators (work stress, home stress, gender, academic rank, tenure status, and having at least one child age 12 and younger), which define this 4-class model, are shown in Table 2. Age, marital status, type of academic degree (clinical vs. nonclinical), caring for elderly dependents, or having a household partner as essential worker were among the variables that did not yield significant results.

Table 2.

Final Demographic, Academic, and Stress Variables Entered in the Latent Class Analysis with Their Contribution to the Final 4-Class Model (n = 483)

| Variables | Total faculty n = 483 | Class 1 n = 181 | Class 2 n = 95 | Class 3 n = 125 | Class 4 n = 82 | ANOVA or chi square p-valuea | Wald statisticb G-K θ-bc p-valued |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic variables | |||||||

| Age, yearse | 49 [40–60] | 40 [35–48] | 47 [43–51] | 60 [53–67] | 59 [43–66] | <0.0001 | ns |

| Genderf | 27.181 | ||||||

| Women | 291 (60.3) | 138 (76.2) | 62 (65.3) | 55 (44.0) | 36 (43.9) | <0.0001 | 0.084 |

| Men | 192 (39.7) | 43 (23.8) | 33 (34.7) | 70 (56.0) | 46 (56.1) | 5.4 × 10−6 | |

| Marital statusf | |||||||

| Single | 57 (11.9) | 29 (16.2) | 4 (4.2) | 9 (7.3) | 15 (18.3) | 0.020 | ns |

| Married or cohabitating | 383 (79.8) | 138 (77.1) | 81 (85.3) | 104 (83.9) | 60 (73.2) | ||

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 40 (8.3) | 12 (6.7) | 10 (10.5) | 11 (8.9) | 7 (8.5) | ||

| Children ≤12f | 28.312 | ||||||

| Yes | 151 (31.3) | 83 (45.9) | 53 (55.8) | 6 (4.8) | 9 (11.0) | <0.0001 | 0.173 |

| No | 332 (68.7) | 98 (54.1) | 42 (44.2) | 119 (95.2) | 73 (89.0) | 3.1 × 10−6 | |

| Academic variables | |||||||

| Academic rankf | |||||||

| Lecturer/instructor | 39 (8.1) | 27 (14.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (14.6) | <0.0001 | 48.888 |

| Assistant professor | 159 (32.9) | 144 (79.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | 14 (17.1) | 0.4684 | |

| Associate professor | 126 (26.1) | 0 (0.0) | 83 (87.4) | 19 (15.2) | 24 (29.3) | 2.2 × 10−6 | |

| Professor | 117 (24.2) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (12.6) | 105 (84.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Visiting/adjunct | 42 (8.7) | 10 (5.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 32 (39.0) | ||

| Degreef | |||||||

| Clinical degreeg | 138 (28.6) | 60 (33.1) | 32 (34.0) | 21 (16.8) | 25 (30.5) | <0.0001 | ns |

| Nonclinical degreeh | 323 (67.0) | 117 (64.6) | 59 (62.8) | 90 (72.0) | 57 (69.5) | ||

| Dual degreei | 21 (4.4) | 4 (2.2) | 3 (3.2) | 14 (11.2) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Tenure trackf | |||||||

| Tenured | 159 (32.9) | 1 (0.6) | 55 (57.9) | 103 (82.4) | 0 (0.0) | <0.0001 | 24.700 |

| On tenure track, not tenured | 48 (9.9) | 46 (25.4) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.408 | |

| Not on tenure track | 276 (57.1) | 134 (74.0) | 39 (41.0) | 21 (16.8) | 82 (100.0) | 3.9 × 10−4 | |

| Stress-related variables | |||||||

| Work-related stress | 35.353 | ||||||

| Highj | 356 (73.7) | 167 (92.3) | 94 (99.0) | 84 (67.2) | 11 (13.4) | <0.0001 | 0.366 |

| Low | 127 (26.3) | 14 (7.7) | 1 (1.0) | 41 (32.8) | 71 (86.6) | 1.0 × 10−7 | |

| Home-related stress | 35.671 | ||||||

| Highj | 289 (59.8) | 138 (76.2) | 90 (94.7) | 37 (29.6) | 24 (29.3) | <0.0001 | 0.257 |

| Low | 194 (40.2) | 43 (23.8) | 5 (5.3) | 88 (70.4) | 58 (70.7) | 8.8 × 10−8 | |

Class 1: high work stress, high home stress, more likely to be women, assistant professors, and not tenured, and more likely to have a child 12 years of age and younger; Class 2: high work stress, high home stress, more likely to be women, associate professors, and tenured, and more likely to have children 12 years of age and younger; Class 3: moderate work stress, low home stress, more likely to be men, professors, and tenured, and less likely to have a child 12 years of age and younger; Class 4: low work stress, low home stress, more likely to be men and adjunct or visiting professor, less likely to be tenured, and less likely to have a child 12 years of age and younger.

p-values <0.05 are shown in bold font.

Wald statistic values are provided to assess the statistical significance of each nominal parameter to the LCA model. A nonsignificant associated LCA p-value means that the variable does not discriminate between the clusters in a statistically significant way and can be excluded to keep the model parsimonious.

Goodman Kruskal tau-b coefficient (G-Kθ) is a more general coefficient of association between two nominal variables. The closer G-Kθ is to 1 the higher the association and the contribution of the respective indicator in discriminating between latent clusters of the final model.

Wald statistic-associated p-value.

Data shown as median [interquartile range] and compared by Kruskal Wallis ANOVA.

Data shown as n (%) and compared by chi square test.

Clinical degree: DDS, DMD, DO, MD, or PharmD.

Nonclinical degree: PhD, DrPH, EdD, or any master's degree or other degree.

Dual degree: Clinical degree plus a PhD or Masters.

High stress individuals answered as “much more stressful” or “more stressful” to two or more of the questions in the group.

LCA, latent class analysis.

Membership of respondents for the four-class solution was as follows: Class 1: 35% (n = 181), Class 2: 22% (n = 95), Class 3: 24% (n = 125), and Class 4: 19 (n = 82). The mean probability of membership for each class was 0.91, 0.92, 0.85, and 0.88, respectively, suggesting clear distinctions among the four subgroups of respondents: a respondent grouped into a particular class had a high probability of belonging to that class, and no other. Figure 3 illustrates the profile of faculty based on the significant indicators defining each class, as listed below:

FIG. 3.

Profile plot of the 4-cluster model solution of the LCA applied to the 483 respondents in the study, who completed the stress questions. The x-axis lists the discriminative indicators with their modal characteristic for which the probability level expected to manifest in each of the four latent clusters is displayed on the y-axis. The interrupted line marks the 50% probability level.

Class 1 respondents reported high work and home stress, and were more likely to be women, assistant professors, and not tenured, and to have a child 12 years of age and younger.

Class 2 respondents reported high work and home stress, and were more likely to be women, associate professors, and tenured, and to have a child 12 years of age and younger.

Class 3 respondents reported moderate work stress, but lower home stress, and were more likely to be men, professors, and tenured, and less likely to have a child 12 years of age and younger.

Class 4 respondents reported lower work and home stress, and were more likely to be men, adjunct or visiting professors, and not tenured, and less likely to have a child 12 years of age and younger.

LCA results

Differences in time allocation pre-COVID

There were significant differences in how faculty in the four latent classes spent their time working before the pandemic (for details, see Supplementary Table S4). Class 4 devoted less time to grants and advising compared with the other three classes. They devoted more time to clinical and teaching responsibilities compared to Classes 2 and Class 3, but not compared to Class 1, and spent less time writing articles than Class 2. Class 2 spent a significantly higher proportion of work time dedicated to committee and administrative responsibilities, compared to Classes 1 and 4. but not compared to Class 3.

Differences in time spent on department meetings, remote work, and other responsibilities before the pandemic did not reach significance. Classes 1 and 2 differed in allocation of effort regarding committee and administrative responsibilities. Class 1 was significantly different from Class 3 in managing research grants, teaching responsibilities, and clinical responsibilities. Class 2 did not differ from Class 3 in any of the categories.

Changes to time allocation and research productivity during the COVID-19 pandemic

Statistically significant changes to effort allotted to departmental meetings and functions (p = 0.013), grant development and submission (p = 0.002), scholarly productivity (p < 0.001), committee and/or administrative responsibilities (p < 0.001), and clinical work (p < 0.001) were reported among the four classes (for details, see Supplementary Table S5). Specifically, 54.7% of Class 2 faculty reported a decrease in scholarly productivity. The classes did not differ in changes to percent time allocated to managing a research group, grant, or laboratory, teaching, or advising, suggesting that within the constraints of each class, these activities were less likely to shift during the pandemic.

Research productivity as measured by the number of articles planned or submitted also differed by class. Class 3 respondents planned more articles (2.13 ± 0.15) compared with Class 4 and submitted more articles (1.74 ± 0.16) compared to Classes 1, 2 and 4 (for details, see Supplementary Table S6).

Differences in self-care during-COVID-19

There were significant differences in self-care characteristics with respect to sleep, diet, exercise, and use of mental health and emotional support services among the four classes (Table 3). Increased sleep disturbance was reported by the majority of faculty in Class 1 (61.9%) and Class 2 (63.8%), while most faculty in Class 3 (45.6%) and Class 4 (50.0%) reported no change in sleep. More faculty in Class 1 (51.4%) and Class 2 (48.9%) reported a disturbance in their diet compared to Class 3 (27.2%) and Class 4 (28.1%). A decrease in exercise was reported by the majority of faculty in all 4 classes, with 61.9%, 58.5%, 45.6%, and 41.5% for Class 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. No significant change was reported in the self-care domains of mental health services and emotional support from friends, family, and colleagues.

Table 3.

Distribution of Faculty by Perceived Changes to Self-Care During Coronavirus Disease by Latent Class Assignment (n = 483)

| Self-care characteristics | Class 1 n = 181 | Class 2 n = 95 | Class 3 n = 125 | Class 4 n = 82 | Chi square p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleepb,c | |||||

| Disturbed | 112 (61.9) | 60 (63.8) | 56 (44.8) | 28 (34.1) | <0.001 |

| No change | 52 (28.7) | 32 (34.1) | 57 (45.6) | 41 (50.0) | |

| Improved | 17 (9.4) | 2 (2.1) | 12 (9.6) | 13 (15.9) | |

| Dietb,c | |||||

| Disturbed | 93 (51.4) | 46 (48.9) | 34 (27.2) | 23 (28.1) | <0.001 |

| No change | 54 (29.8) | 37 (39.4) | 57 (45.6) | 38 (46.3) | |

| Improved | 34 (18.8) | 11 (11.7) | 34 (27.2) | 20 (24.4) | |

| Exerciseb,c | |||||

| Decreased | 112 (61.9) | 55 (58.5) | 57 (45.6) | 34 (41.5) | <0.001 |

| No change | 20 (11.0) | 22 (23.4) | 33 (26.4) | 25 (30.5) | |

| Increased | 49 (27.1) | 16 (17.0) | 35 (28.0) | 23 (28.0) | |

| Use of mental health servicesb,c | |||||

| Increased | 24 (13.3) | 12 (12.8) | 1 (0.8) | 3 (3.6) | <0.001 |

| No change | 143 (79.0) | 79 (84.0) | 116 (92.8) | 75 (91.5) | |

| Decreased | 14 (7.7) | 2 (2.1) | 5 (4.0) | 3 (3.7) | |

| Emotional support from friends, colleagues, familyb,c | |||||

| Decreased | 56 (30.9) | 32 (34.0) | 32 (25.6) | 12 (14.6) | <0.001 |

| No change | 69 (38.1) | 38 (40.4) | 61 (48.8) | 56 (68.3) | |

| Increased | 56 (30.9) | 23 (24.5) | 31 (24.8) | 14 (17.1) | |

Class 1: high work stress, high home stress, more likely to be women, assistant professors, not tenured, and more likely to have a child 12 years of age and younger; Class 2: high work stress, high home stress, more likely to be females, associate professors, tenured, and more less likely to have a child 12 years of age and younger; Class 3: moderate work stress, low home stress, more likely to be men, professors, tenured, and less likely to have a child 12 years of age and younger; Class 4: low work stress, low home stress, more likely to be males and adjunct or visiting professor, less likely to be tenured, and less likely to have a child 12 years of age and younger.

p-values <0.05 are shown in bold font.

Totals do not add up due to missing values.

Data presented as n (%) and analyzed by chi square.

Discussion

With the novel use of LCA, we found four distinct faculty profiles that were differentially impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Class 1 and Class 2 faculty (more likely to be assistant and associate professors, women with young children) were more likely to have high work and home stress, changes in work–work balance, and disturbances in self-care. Conversely, Class 3 faculty (more likely to be professors, men without young children) reported moderate work stress and low home stress. Class 4 faculty reporting low work and home stress were less likely to be tenured and without young children. The significance of the classes was validated by their differences in work commitments before and during the pandemic along with changes in productivity.

Although self-care variables were not used as indicators in the LCA models, the differences in self-care between classes mirror the self-reported stress levels and provide further validation to our latent class classification.

Our study examines the interplay between home and work demands, reported stress, academic productivity, and self-care of faculty in the health sciences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Reported changes in scholarly productivity were different among the four classes. While the number of articles planned were the same for Classes 1, 2 and 3, the number of articles submitted was significantly greater for Class 3, who were mostly older, tenured professors without young children or a clinical degree. Changes in administrative and clinical responsibilities were also different among the classes.

Similar to previously published work, we found stress levels were high for both men and women during the COVID-19 pandemic, with women reporting greater levels of stress with respect to work and home responsibilities.4,10,22–25 However, rather than focus on gender alone, our study aimed to provide insight about some of the additional factors that contributed to the faculty members' experiences of and challenges during the pandemic. The disruption caused by the pandemic put even greater pressure on the tenure clock for academic promotion, which is dependent on innovative research, producing publications, and securing grant funding. Therefore, to require the same level of research and tenure expectations will perpetuate and increase the disparity between faculty with care responsibilities of children, aging parents, and ill or disabled dependents and those who do not.

Unless labor contribution policies (i.e., authorship standards) are changed, or time frames extended, those members most affected by the pandemic may experience burnout and even depart from the workforce.26 This winnowing effect may impact not only women but also faculty with diverse gender, ethnic, religious, and socioeconomic backgrounds.27

Our study highlights the need for academic health centers to incorporate best practices from other academic settings. Our research supports the recommendations in the Chronicle of Higher Education for policies that take into account caregiving by providing flexibility in how and where work is accomplished and the need for institutions to modify promotion standards and/or provide flexibility in the timing of promotion.28 Policies need to foster equitable faculty growth and development by incorporating broader indicators of academic productivity that accounts for academic rank, administrative, clinical, and caretaking responsibilities and how faculty with different responsibilities at home and work were impacted by the pandemic. Service and administrative tasks and activities that required extra time and energy during the pandemic should be valued equitably for promotion and tenure.

Among these, COVID vitae supplements detailing on supplemental activities during the pandemic have been proposed.29 Tenure clock extension policies should be made opt out instead of opt in. Importantly, the impact of such policies needs to be tracked by faculty characteristics such as the ones uncovered by this study. As a result of our research, UIC has introduced policies related to the pandemic, but not before this survey was conducted. In fact, the results of this study and subsequent follow-up studies are actively informing the leadership on implementation of new policies.

We suggest that academic leadership use research evidence to guide promotion and tenure policies. Our study shows that faculty in leadership positions are likely to be among those in Class 3, and more likely to be men with lower work and home stress compared to Class 1 and Class 2 faculty. For those in Class 3, work activities remained stable, and their article production increased. Disturbances in self-care activities and high stress levels, potential precursors to burnout, were most prominent for faculty in Classes 1 and 2. Policies that address faculty well-being and work satisfaction are essential to retention and promotion and need to be included to ensure equity across faculty.30 The mental and physical strain of the pandemic have the capacity to fuel already high rates of faculty burnout. We risk losing faculty at junior ranks and further contributing to the culling effect in senior ranks.

Our survey spotlights a large urban university, with respondents comprising both academic and clinical faculty from a broad range of disciplines from the health sciences. The generalizability of our findings may be limited as our respondents were a convenience sample and subject to nonresponse bias. Although the proportion of 12% underrepresented minorities in our sample aligns if not exceeds the current representation in academia,31 the impact of race or ethnicity could not be an adequately explored part of this study. Also, the productivity information was not confirmed with objective measures and was solely based on individual perception. However, the strength of this study is the use of LCA, which led us to highlight characteristics that may explain the heterogeneity in how academic faculty have been affected by the pandemic.

Conclusions

We demonstrate the need for academic leaders to evaluate how their faculty were affected by the pandemic. Our analysis illustrates that academic faculty are a heterogeneous workforce of individuals with different demographics, home/work stresses, varying proportions of contributions to the clinical, service, and research realms, and methods for self-care. To effectively support their faculty, academic leaders need to acknowledge these differences and be inclusive of faculty with different experiences when adjusting workplace or promotion policies. Future analyses should seek to recognize the long-term sequela of the pandemic on work–life balance, productivity, and faculty career trajectories.

Data Availability

The survey and the raw data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable written request.

Ethics Approval

Ethics approval was granted by Institutional Review Board of University of Illinois at Chicago as noted in Methods.

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Supplementary Material

Authors' Contributions

P.K.-S.: conceptualization and design of the study, development of the survey, interpretation of data, writing of article, and final approval of submission. B.M.: conceptualization and design of the study, development of the survey and REDCap database, interpretation of data, writing of article, and final approval of submission. R.P.: analysis and interpretation of the data, editing of the article for important intellectual content, and final approval submission. L.E..: design of the study, development of the survey, interpretation of data and editing of the article for important intellectual content, and final approval submission.

B.J.R.: design of the study, development of the survey, interpretation of data and editing of the article for intellectual content, and final approval submission. I.A.B.: conceptualization and design of the study, analysis of the data, interpretation of findings, editing of the article for intellectual content, and final approval submission. H.M.W.: conceptualization and design of the study, preparation and submission of the IRB, development of the survey, interpretation of data, writing of article, and final approval submission.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors have no competing interests, personal financial interests, or other competing conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Information

This work was supported by the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC)‘s Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women's Health (BIRCWH) grant K12HD101373 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Office of Research on Women's Health (ORWH). The REDCap database used in this project was made possible through the UIC Clinical and Translational Sciences (CCTS) funded by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Grant UL1TR002003.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Czeisler MÉ, Tynan MA, Howard ME, et al. Public attitudes, behaviors, and beliefs related to COVID-19, stay-at-home orders, nonessential business closures, and public health guidance—United States, New York City, and Los Angeles, May 5–12, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:751–758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Flaherty C. Faculty Home Work. Inside Higher Ed, 2020. Available at: https://www.insidehighered.com/print/news/2020/03/24/working-home-during-covid-19-proves-challenging-faculty-members Accessed April 9, 2021.

- 3. Andersen JP, Nielsen MW, Simone NL, Lewiss RE, Jagsi R. COVID-19 medical papers have fewer women first authors than expected. Elife 2020;9:e58807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Krukowski RA, Jagsi R, Cardel MI. Academic productivity differences by gender and child age in science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and medicine faculty during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2021;30:341–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. de Gruyter W GmbH. Available at: https://blog.degruyter.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Locked-Down-Burned-Out-Publishing-in-a-pandemic_Dec-2020.pdf Accessed April 9, 2021.

- 6. Delaney RK, Locke A, Pershing ML, et al. Experiences of a health system's faculty, staff, and trainees' career development, work culture, and childcare needs during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e213997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lee JE, Mohanty A, Albuquerque FC, et al. Trends in academic productivity in the COVID-19 era: Analysis of neurosurgical, stroke neurology, and neurointerventional literature. J Neurointerv Surg 2020;12:1049–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gewin V. Pandemic burnout is rampant in academia. Nature 2021;591:489–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sarma S, Usmani S. COVID-19 and physician mothers. Acad Med 2021;96:e12–e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Misra J, Lundquist JH, Templer A. Gender, work time, and care responsibilities among faculty. Sociol Forum 2012;27:300–323. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Feingold JH, Peccoralo L, Chan CC, et al. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on frontline health care workers during the pandemic surge in New York City. Chronic Stress (Thousand Oaks) 2021;5:2470547020977891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kannampallil TG, Goss CW, Evanoff BA, Strickland JR, McAlister RP, Duncan J. Exposure to COVID-19 patients increases physician trainee stress and burnout. PLoS One 2020;15:e0237301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Conroy DA, Hadler NL, Cho E, et al. The effects of COVID-19 stay-at-home order on sleep, health, and working patterns: A survey study of US health care workers. J Clin Sleep Med 2021;17:185–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Association of American Universities Data Exchange, 2020. About AAUDE. Available at: http://aaude.org Accessed March 24, 2021.

- 15. Miller CC. Nearly Half of Men Say They Do Most of the Home Schooling. 3 Percent of Women Agree. New York Times, 2020. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/06/upshot/pandemic-chores-homeschooling-gender.html Accessed March 28, 2021.

- 16. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 2019;95:103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. University of Illinois at Chicago Office of Institutional Research Faculty Staff Dashboards, 2021. Available at: https://oir.uic.edu/data/faculty-staff-data/faculty-staff-dashboards/ Accessed March 24, 2021.

- 19. Vermunt JK, Magidson J. Latent class models for classification. Comput Stat Data Anal 2003;41:531–537. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vermunt JK, Magidson J. Latent GOLD 2.0 user's guide. Belmont, MA: Statistical Innovations, Inc., 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Burnham KP, Anderson DR. Multimodel Inference: Understanding AIC and BIC in model selection. Sociol Methods Res 2004;33:261–304. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gabster BP, van Daalen K, Dhatt R, Barry M. Challenges for the female academic during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2020;395:1968–1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Deryugina T, Shurchkov O, Stearns JE. COVID-19 Disruptions disproportionately affect female academics NBER Working Paper No. 2836. 0 January 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Halley MC, Mathews KS, Diamond LC, et al. The intersection of work and home challenges faced by physician mothers during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: A mixed-methods analysis. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2021;30:514–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Woitowich NC, Jain S, Arora VM, Joffe H. COVID-19 threatens progress toward gender equity within academic medicine. Acad Med 2021;96:813–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Alon T, Doepke M, Olmstead-Rumsey J, Tertilt M. The Impact of COVID-19 on Gender Equality, NBER Working paper No. 26947. 2020;DOI: 10.3386/w26947. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Carr PL, Gunn C, Raj A, Kaplan S, Freund KM. Recruitment, promotion, and retention of women in academic medicine: How institutions are addressing gender disparities. Womens Health Issues 2017;27:374–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Petit E. Faculty members are suffering burnout. These strategies could help. The chronicle of higher education, 2021. Available at: https://www.chronicle.com/article/faculty-members-are-suffering-burnout-so-some-colleges-have-used-these-strategies-to-help Accessed March 10, 2021.

- 29. Arora VM, Wray CM, O'Glasser AY, Shapiro M, Jain S. Leveling the playing field: Accounting for academic productivity during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hosp Med 2021;16:120–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Warner ET, Carapinha R, Weber GM, Hill EV, Reede JY. Faculty promotion and attrition: The importance of coauthor network reach at an academic medical center. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31:60–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bennett CL, Salinas RY, Locascio JJ, Boyer EW. Two decades of little change: An analysis of U.S. medical school basic science faculty by sex, race/ethnicity, and academic rank. PLoS One 2020;15:e0235190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The survey and the raw data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable written request.