Abstract

Background

While guidelines recommend that children with asthma should receive asthma education, it is not known if education delivered in the home is superior to usual care or the same education delivered elsewhere. The home setting allows educators to reach populations (such as the economically disadvantaged) that may experience barriers to care (such as lack of transportation) within a familiar environment.

Objectives

To perform a systematic review on educational interventions for asthma delivered in the home to children, caregivers or both, and to determine the effects of such interventions on asthma‐related health outcomes. We also planned to make the education interventions accessible to readers by summarising the content and components.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register of trials, which includes the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, AMED and PsycINFO, and handsearched respiratory journals and meeting abstracts. We also searched the Education Resources Information Center database (ERIC), reference lists of trials and review articles (last search January 2011).

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials of asthma education delivered in the home to children, their caregivers or both. In the first comparison, eligible control groups were provided usual care or the same education delivered outside of the home. For the second comparison, control groups received a less intensive educational intervention delivered in the home.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently selected the trials, assessed trial quality and extracted the data. We contacted study authors for additional information. We pooled dichotomous data with fixed‐effect odds ratio and continuous data with mean difference (MD) using a fixed‐effect where possible.

Main results

A total of 12 studies involving 2342 children were included. Eleven out of 12 trials were conducted in North America, within urban or suburban settings involving vulnerable populations. The studies were overall of good methodological quality. They differed markedly in terms of age, severity of asthma, context and content of the educational intervention leading to substantial clinical heterogeneity. Due to this clinical heterogeneity, we did not pool results for our primary outcome, the number of patients with exacerbations requiring emergency department (ED) visit. The mean number of exacerbations requiring ED visits per person at six months was not significantly different between the home‐based intervention and control groups (N = 2 studies; MD 0.04; 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐0.20 to 0.27). Only one trial contributed to our other primary outcome, exacerbations requiring a course of oral corticosteroids. Hospital admissions also demonstrated wide variation between trials with significant changes in some trials in both directions. Quality of life improved in both education and control groups over time.

A table summarising some of the key components of the education programmes is included in the review.

Authors' conclusions

We found inconsistent evidence for home‐based asthma educational interventions compared to standard care, education delivered outside of the home or a less intensive educational intervention delivered at home. Although education remains a key component of managing asthma in children, advocated in numerous guidelines, this review does not contribute further information on the fundamental content and optimum setting for such educational interventions.

Plain language summary

Home‐based educational interventions for families of children with asthma

Asthma is a common childhood illness causing wheezing, coughing and difficulty in breathing. Guidelines on the care of children with asthma recommend that children and families should receive education on how to manage their condition. The current review looked at 12 studies with a total of 2342 children comparing asthma education received at home with either usual care or a less intensive home‐based education programme. Eleven out of 12 trials were conducted in North America, within urban or suburban settings involving socioeconomically disadvantaged families. A table summarising some of the key components of the education programmes is presented in the review.

The included studies varied in the characteristics of children (e.g. age, severity of asthma), the education delivered and the way each outcome was reported. This made it difficult to compare the results and provide overall conclusions and we did not pool results for most of the outcomes. There was also diversity in the findings of the individual trials. We were able to combine the results of two studies reporting the average number of emergency department visits per child, which was not different at six months between the home education group and the group receiving the usual care. Only one trial contributed to our other primary outcome, exacerbations (flare‐ups) requiring a course of oral corticosteroids. Hospital admissions also demonstrated wide variation between trials with significant changes in some trials in both directions. Quality of life improved in both education and control groups over time.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Education versus control for children with asthma.

| Education versus control for children with asthma | ||||||

| Patient or population: children with asthma Settings: Intervention: education versus control | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Education versus control | |||||

| Exacerbations leading to emergency department visits | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 985 (8 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3,4 | There was too much clinical heterogeneity to pool this outcome |

| Mean exacerbations requiring a course of oral corticosteroids | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 500 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3,4 | There was too much clinical heterogeneity to pool this outcome |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Downgraded two because there was so much heterogeneity in the study populations; we decided not to pool this outcome

2 Downgraded one due to limitation in populations which were predominantly North American socioeconomically disadvantaged children

3 We did not downgrade for indirectness because we felt that there were several reasonably sized RCTS for this outcome. That we did not pool is reflected in downgrading for inconsistency.

4 We did not downgrade for publication bias as most of the trials reported minimal difference in the outcomes of children in the intervention/control groups and therefore we do not think that trials showing no evidence of treatment effect are less likely to be published than others.

Summary of findings 2. Education versus other home‐based education for children with asthma.

| Education versus other home‐based education for children with asthma | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with children with asthma Settings: Intervention: education versus other home‐based education | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Education versus other home‐based education | |||||

| Exacerbations leading to ED visits | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 181 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | There was only one trial contributing to this outcome so we were unable to pool |

| Mean exacerbations requiring a course of oral corticosteroids | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 193 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | There was only one trial contributing to this outcome so we were unable to pool |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; ED: Emergency Department | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Downgraded one due to limitation in populations which were predominantly North American socioeconomically disadvantaged children. 2We did not downgrade for publication bias as most of the trials reported minimal difference in the outcomes of children in the intervention/control groups and therefore we do not think that trials showing no evidence of treatment effect are less likely to be published than others. 3 We downgraded one for imprecision as only one trial contributed to this outcome.

Background

Description of the condition

Asthma is a chronic condition affecting the airways causing wheezing, coughing and difficulty in breathing. It is the most common chronic condition affecting children and is estimated to affect over 300 million people worldwide (GINA 2008). Although a cure does not currently exist, symptoms can be controlled.

Asthma impacts on sufferers' quality and enjoyment of life. They may be less able to undertake strenuous activities and often display increased levels of depression and anxiety (Clayton 2005). Asthma places a financial burden on both the patient and the state from direct medical costs and reduced productivity resulting from days lost at work or school (Wu 2007).

People across the international spectrum of economic development are affected (de Oliveira 1999). Low socioeconomic groups experience higher levels of asthma morbidity (British Guideline on the Management of Asthma; de Oliveira 1999). In addition, people from minority groups have poorer asthma outcomes and typically make more asthma‐related visits to emergency departments (Bailey 2009).

Description of the intervention

Asthma education extends beyond simply providing information. It aims to integrate knowledge, improve self management and produce behaviour change. Education is recommended as an integral part of asthma management (NAEPP 2007; British Guideline on the Management of Asthma; GINA 2008). Education can be delivered to individuals or groups in a number of ways, such as personalised action plans, computer/video games, internet‐enabled packages, role play, problem‐solving, lectures, workshops and booklets. Education may be delivered by a variety of instructors including clinicians, nurses, other allied health professionals and community health workers.

How the intervention might work

Specific components of education interventions may affect behaviour change by:

reinforcing basic information about asthma to embed understanding;

emphasising adherence to prescribed long‐term controller medication;

emphasising the importance of avoiding environmental triggers;

providing self monitoring techniques to help patients identify and respond appropriately to worsening asthma;

providing written action plans to help patients respond correctly to exacerbations; and

improving communication between patients and clinicians.

There are existing reviews showing benefits of education. Wolf 2002 conducted a large systematic review showing that asthma education aimed at two to 18 year olds gave modest improvements in airflow and self efficacy and modest reductions in days off school and emergency department visits. Bhogal 2006 showed that symptom‐based written action plans are better than peak flow‐based ones for preventing acute care visits in children. Gibson 2002 showed that peak flow or symptom‐based self monitoring, coupled with regular medical review and a written action plan led to improved health outcomes in adults. Boyd 2009 showed that asthma education aimed at children and their carers who have attended the emergency department for acute exacerbations resulted in fewer subsequent visits to the emergency department and hospital admissions.

Why it is important to do this review

Education programmes delivered outside of the home may be poorly attended due to a lack of transportation or childcare for siblings. Children with asthma from low‐income families may be more likely to experience such barriers to care. These children also tend to have more severe disease and morbidity at baseline and may derive additional benefit from educational interventions (Brown 2002). Some education programmes attempt to capture a wider audience by employing school‐based delivery, but this does not address obstacles to attendance by caregivers and preschool children. Home‐based education offers an alternative solution to improving access to education.

Asthma education delivered in the home is distinct from that delivered in clinics or schools in factors relating to the educator, the family members receiving it and the environment. Community health workers may provide the education. Although their expertise in asthma management may not be as extensive as that of health professionals, the families may be more responsive to these workers who often share the same socioeconomic status, language and/or culture. Interventions at home could be delivered to additional family members. They may feel more relaxed at home and therefore be more receptive to ideas (Shelledy 2009). Additionally, it provides an opportunity for educators to offer case‐specific guidance on improvements to the living environment (Bryant‐Stephens 2008).

Wolf 2002 recommended that self management education should be routinely used as part of standard asthma therapy in children. This review included a heterogeneous group of education programmes provided in multiple settings. The current review will focus on trials involving asthma education delivered at home to children and/or their caregivers. It will also provide an updated review of home‐based education, which was recommended for young children in the most recent asthma guidelines from the United States (NAEPP 2007) but with a limited quality of evidence (level C).

Objectives

To assess the effects of educational interventions for asthma, delivered in the home to children, their parents or both, on asthma‐related outcomes.

To make the education interventions accessible to readers by summarising the content and components.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled clinical trials (RCTs). We planned to include quasi‐randomised trials (e.g. participants allocated by day of week or hospital number).

Types of participants

We included children and adolescents between two and 18 years of age with an existing diagnosis of asthma. We also included trials with children aged one to two years old if the majority of the children were older than two. We accepted both doctor‐diagnosed asthma or asthma identified against objective criteria for asthma symptoms.

Types of interventions

Inclusion criteria

We included any type of self management education programme delivered in the home of the child or adolescent. We included self management programmes delivered to children, their parents or both. We only included interventions aimed at changing behaviour including one or more of the following methods: providing information about asthma symptoms, medication and inhaler technique; symptom or lung function monitoring; provision or development of personalised action plan; development of coping strategies; improving communication between clinician and patient.

We included control groups that received either usual care, waiting list or a less intensive education programme than the intervention arm, such as information only. We analysed data from usual care control groups separately from those who received a less intensive home‐based educational intervention.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded education that provided only information with no face‐to‐face education programmes, e.g. just giving the child or parent a booklet, smoking cessation programmes for parents and education interventions delivered to physicians, nurses or other healthcare providers rather than the child or carer. We excluded programmes primarily aimed at, and providing, environmental modification (i.e. provision of vacuum cleaners with high‐efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters, HEPA air purifiers, ventilation fans, remediation of mould‐contaminated carpet or wallboard, professional pest control, roach or rodent traps, anti‐allergy mattress or pillow covers) to reduce exposure to indoor allergens. Although this kind of environmental remediation may have a positive effect on asthma outcomes, these studies tend to focus on remediation with education as a secondary measure and may be better addressed as a separate review rather than as a subgroup of this review. We did not exclude trials based on language.

Types of outcome measures

Outcome measures were not a criterion for exclusion in the review.

Primary outcomes

Exacerbations leading to emergency department visits.

Exacerbations requiring a course of oral corticosteroids.

Secondary outcomes

Functional health status (quality of life, days of restricted activity, nights of disturbed sleep, day symptoms).

Days off school or caregiver days off work.

Exacerbations leading to hospitalisations.

Lung function (FEV1 (forced expiratory volume in one second) and PEF (peak expiratory flow)).

Withdrawals from intervention or usual care.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We identified trials using the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register of trials, which is derived from systematic searches of bibliographic databases including the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, AMED and PsycINFO, and handsearched respiratory journals and meeting abstracts (please see the Airways Group search methods for further details). We searched all records in the Specialised Register coded as 'AST' using the following terms:

educat* or train* or instruct* or teach* or taught or coach* or learn* or behav* or self‐monitor* or "self monitor*" or self‐manag* or "self manag*" or self‐car* or "self car*" or patient‐cent* or "patient cent*" or patient‐focus* or "patient focus*" or "management plan*" or "management program*"

In addition, we searched the Education Resources Information Center database (ERIC) using the terms home* AND asthma*, reference lists of trials and review articles. The latest search was January 2011.

We searched both databases from the date of their inception and there was no restriction on the basis of language.

Searching other resources

We reviewed reference lists of all primary studies and review articles for references to additional studies. We contacted authors of identified trials where possible and asked them to identify other published and unpublished studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

One review author (EJW) went through the search to remove references clearly unrelated to the scope of the review based on title alone. Two review authors (EJW and PL for Airways Register search; EJW and MH for ERIC search) independently examined the titles and abstracts of the remaining reports. We retrieved the full text of the potentially relevant references and assigned each reference to a study identifier. Two of authors (EJW, PL) independently compared each study against inclusion criteria and we resolved discrepancies by consensus.

Data extraction and management

We extracted information from each study for the following characteristics.

Design (design, total duration study, number of study centres and location, withdrawals, date of study).

Participants (N, mean age, age range, gender, asthma severity, diagnostic criteria, baseline lung function, sociodemographics, caregivers' education, ethnicity, inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria).

Interventions (total number of intervention and control groups. For each intervention or control group: treatment, programme topics, setting, session type, number of sessions, session length, educator, time span of intervention, self management strategy, educational strategy, instructional methods/tools, additional information and net treatment, incentives, cost).

Outcomes (outcomes specified and collected, time points reported).

Aims.

Risk of bias.

Two authors (EJW, MH or PL) extracted data from the studies and resolved any discrepancies by discussion and consensus, or by consulting a third party where necessary. For each trial, one author (EJW or PL) transferred data from data collection forms into Review Manager 5.1 and this was checked by the other.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed risk of bias in included studies as high, low or unclear using the Cochrane Collaboration's 'Risk of bias' tool and the following headings: 1) sequence generation; 2) allocation concealment; 3) blinding; 4) incomplete outcome data; 5) selective outcome reporting; 6) other bias.

Unit of analysis issues

Studies that compare two types of education intervention with a control may yield important comparison results between two education types (Wolf 2002). We therefore entered both intervention arms separately in the meta‐analyses and split the control group in half (to avoid double‐counting) rather than combining the two arms (Higgins 2008).

Dealing with missing data

We requested additional data including missing numerical data and information required for the risk of bias assessment from trialists.

Analyses based on change scores were preferred, but we used final values where change scores were not available.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We reported heterogeneity using the I2 statistic and descriptively by examining the clinical characteristics of the population and interventions.

Assessment of reporting biases

We reported the proportion of participants contributing to each outcome in comparison to the total number randomised. We intended to examine funnel plots but there were insufficient trials.

Data synthesis

We planned to combine dichotomous data using the Mantel‐Haenszel fixed‐effect odds ratio using 95% confidence intervals. We planned to combine continuous data with either mean difference (MD) or standardised mean difference (SMD) using a fixed‐effect model and 95% confidence intervals.

We presented absolute differences in a 'Summary of findings' table for the primary outcomes which we produced using GRADE methodology.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to investigate heterogeneity based on the following predefined subgroups.

Children (2 to 12) versus adolescents (12 to 18).

Mild/moderate versus severe asthma.

Short time frame trials < 6 months versus long time frame > 6 months.

Physician or nurse versus community health worker.

We planned to apply a test for interaction between subgroup estimates (Altman 2003).

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to assess the sensitivity of our primary outcomes to the degree of risk of bias. We planned to compare the results of fixed and random‐effects models. If combining change scores and final value scores we planned to look at baseline imbalance.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

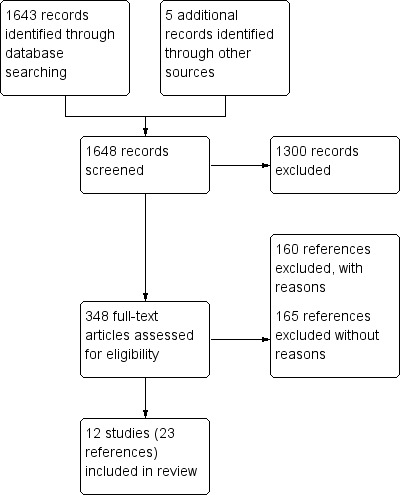

The search of the Airways Register returned 1584 references. We discarded 487 references that were clearly not relevant to the review question on the basis of title alone. We examined the remaining 1097 references. There were 130 initial disagreements which were resolved through discussion. We retrieved 235 full‐text documents in total identified from the search. We identified five references from contacting authors and reference lists of included studies. We contacted the author of an abstract who identified the full text which was in press (Seid 2010). We contacted the author of a www.clincaltrial.gov entry who informed us that the trial had been published in full (Galbreath 2008) and one study that had previously been excluded on the basis of title and abstract was identified from a previous review (Gorelick 2006). We imported these 348 references into Review Manager 5.1, grouped the references into studies and discarded duplicate references, although these groupings evolved during the process of data extraction. Ultimately we identified 12 unique studies for inclusion. A PRISMA diagram can be found in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

The search in the ERIC database returned 59 references. Six studies were identified as potentially eligible. Three of these had been returned by the Airways Register search, whilst the other three were ultimately excluded.

Included studies

There were 12 included randomised controlled trials reporting data on children who had received education delivered in the home. There were a total of 2342 participants. Full details can be found in Characteristics of included studies. Key characteristics of the participants and education programme content are summarised in Table 3.

1. Summary of characteristics of included studies.

| Study | No./length sessions, where | Educator | Programme length (follow‐up time) |

% severe (how identified) (inclusion criteria relating to HCU/meds) |

Mean age (range) |

Social indicators (education status refers to caregiver) |

Basic education1, printed materials and homework | Medication/ inhaler technique | Self management | Monitoring2 or telecare | Written action plan | Trigger ID/ environmental | Other |

|

Brown 2002 N = 101 |

8 x 90‐minute home weekly, USA |

Nurse | < 6 months (12 months) | 4 (as per medication regimen) (Healthcare visit for asthma in past year and on daily asthma medication) |

4.2 (1 to 7) | Low‐income families < high school 28%, high school qualification 50%, > high school 22% 90% African American |

√√ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Wee Wheezers | |

|

Brown 2006 N = 137 |

1 x clinic, 1 x home, USA |

Nurse | < 6 months (6 months) | 37 (NHLBI) (Moderate to severe asthma or had visited the ED in the past year) |

< 18 | < high school 18%, high school qualification 32%, > high school 50% 30% African American, 59% White |

√ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Stressed monitoring and self evaluation | |

|

Butz 2006 N = 221 |

6 x 1‐hour home, USA |

Nurse | 6 months (12 months) | 14 (NAEPP) (regular nebuliser use and ED visit/hospitalisation in past year) |

4.5 (2 to 9) | Low‐income families < high school 24%, high school qualification 28%, > high school 38% on MedicAid 80% African American 89% |

√ | √ | √ | √ | √ | * The control group receive a home visit education programme and the additional intervention for the intervention group is a nebuliser‐based intervention. nebuliser group only: Wee Wheezers, A+ Asthma Club Program |

|

| Butz 2010 | 4 x 30 to 45 minutes home, accompanied to primary care clinic visits x 6 months, USA | Nurse/health educator | 8 weeks (12 months) | 13 (NHLBI) >= 1 asthma ED visits or hospitalisation in preceding year |

8.0 (6 to 12) | Caregiver education < high school graduate 32.0%; high school graduate or more education 68.0% Income < USD 20,000: 57.1%; >= USD 20,000: 42.9% |

√√ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Asthma communication education based on Chronic Care Model and other communication concepts | |

|

Dolinar 2000 N = 56 |

1 x 2‐hour home, Canada |

Principal investigator (nurse) | < 6 months (3 months) | 'Stable asthma' with a diagnosis for over 6 months. Those presenting with an acute exacerbation were excluded. | 5 (1 to 10) | High school 38%, college/university 63% Family income < CAD 20,000 (Cdn) 13% |

√√ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Air Force Asthma | |

| Fisher 2009 | 2 x home, biweekly telephone calls x 3 months, then monthly USA |

3 African American women from same neighbourhoods as participants | 2 years (2 years) | Not specified but recruited after hospitalisation | 4.9 (2 to 8) | No high school diploma 33%, high school qualification 40%, some college 23%, college graduate 4% | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Transtheoretical Model (behaviour change strategy) |

|

Galbreath 2008 N = 473 |

4 x home at 1, 2, 3 and 6 months, 6 to 7 telephone sessions, USA |

Registered nurses for education over the phone and 24 hour hotlines. Pulmonary therapist |

6 (12 months) | 31 (NAEPP) 48 (GINA 2002) (ED visit or hospitalisation or 4 x GP visits or 6+ canisters of beta‐agonist or diagnosis of moderate‐severe asthma in past year) |

9.5 (5 to 17) | Medicaid or SCHIP 56%, black/other 18%, white 15%, Hispanic 68% | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

|

Gorelick 2006 N = 352 |

1 x 60 minutes home then 5 x 30 minutes home, plus several telephone calls over 6 months USA |

Case manager (nurse or social worker) | 6 months (6 months) | 14 (NAEPP) (current ED visit for asthma, treated with 1 inhaled bronchodilator, and history of physician diagnosed asthma or wheezing treated with beta‐agonists) |

6.8 (2 to 18) | 60% public insurance black 69%, white 21%, Latino 8% |

√√ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Fight Asthma Milwaukee (FAM) Allies Coalition |

|

Kamps 2008 N = 15 |

6 x 1 hour weekly home, USA |

Licensed psychologists or masters‐level psychology graduate students | < 6 months (12 months) | Moderate to severe persistent (NHLBI) (Prescribed ICS) |

9 (7‐12) | Half of participants recruited from urban and half from suburban areas Intervention: high school qualification mothers 0% fathers 14%, some college mothers100% fathers 86%; control: no high school diploma mothers 50% fathers 57%, high school qualification mothers 25 fathers 14%, some college mothers 25 fathers 29%. 20% African American, 53% European American, 27% Hispanic American |

√√ | √ | √ | √ | √ | * The control group also receive a standard comprehensive education programme based on Air Wise programme and they watched Clubhouse Kids Learn About Asthma. The Clubhouse Kids Learn Asthma More intense group received a behavioural management technique intervention to improve adherence to corticosteroids. Unique barriers to adherence were identified and discussed and written solutions were provided. |

|

|

Mitchell 1986 N = 368 |

6 x 1 hour monthly home, New Zealand |

Community child health nurse | 6 months (18 months) | Children who had been admitted to hospital for asthma (Patients who had been discharged from hospital in the past year) |

5.8 (2 to 14) | European children significantly more advantaged than Polynesian children | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

|

Otsuki 2009 ABC N = 250 (total) |

5 x 30 to 40 minutes home, USA |

Trained asthma educators | < 6 months (18 months) | Physician diagnosed asthma, 2 x ED visits or 1 x hospitalisations in the preceding year and on asthma controller medications | 7.14 (2 to 12) | Medicaid 89%, caregiver completed high school 69% 98% African American |

√√ | √ | √ discussed strategies | √ | Identification of barriers to health care and discussion of beliefs and concerns | ||

| Otsuki 2009 AMF | 5 x 30 to 40 minutes home, USA |

Trained asthma educators | < 6 months (18 months) | " | 6.83 (2 to 12) | Medicaid 89%, caregiver completed high school 69% 98% African American |

√√ | √ | √ | √ electronic medication/ feedback monitors | √ | Identification of barriers to health care and discussion of beliefs and concerns. Goal‐setting, reinforcement of adherence goals and importance of rewards | |

|

Seid 2010 N = 252 (total) |

5 x 45 to 60 minutes, weekly, USA |

Bilingual, bicultural bachelors educated asthma home visitors | < 6 months (9 months) | 33 | 7.37 (2 to 14) | 85% from subsidised community clinics (most low‐income) No diploma 73%, high school graduate 8%, > college19% Hispanic 83%, white 4%, black, 8% |

√√ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Seid 2010 problem solving | 6 x 45 to 60 minutes, weekly, USA |

Bilingual, bicultural masters educated asthma home visitors | < 6 months (9 months) |

33 | 7.37 (2 to 14) | " | √√ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Problem‐solving skill training, rapport building |

1. Basic education on concepts of asthma

2. Monitoring of asthma management by a health professional or electronic device

ED: Emergency Department; ICS: inhaled corticosteroid; NAEPP: National Asthma Education and Prevention Program; NHLBI: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute guidelines; SCHIP: State Children's Health Insurance Program administered by the United States Department of Health and Human Services that matches funds to states for health insurance to families with children. Designed to cover uninsured children in families with incomes that are modest but too high to qualify for Medicaid.

Setting and populations

Ten studies took place in the USA (Brown 2002; Butz 2006; Gorelick 2006; Brown 2006; Galbreath 2008; Kamps 2008; Fisher 2009; Otsuki 2009; Butz 2010; Seid 2010), one in Canada (Dolinar 2000) and one in New Zealand (Mitchell 1986). The latter study divided the population into two ethnic groups; Polynesian and European children (Mitchell 1986). Patients were recruited mostly from the Emergency Department (ED) in four studies (Brown 2006; Gorelick 2006; Otsuki 2009; Butz 2010), mostly outpatient clinics in five studies (Dolinar 2000; Brown 2002; Butz 2006; Kamps 2008; Seid 2010) and following a hospital admission in two studies (Mitchell 1986; Fisher 2009). One study recruited patients by various methods including referrals, reviewing patient lists and the media (Galbreath 2008). Eleven of the studies were conducted between 2000 to 2010, while one was much older (Mitchell 1986). The studies varied in size from 15 to 316 participants.

Seven studies reported participants with a range of asthma severity from mild to severe, with the latter group varying from 4% to 37% (Brown 2002; Butz 2006; Brown 2006; Gorelick 2006; Galbreath 2008; Butz 2010; Seid 2010). Kamps 2008 enrolled participants with moderate to severe asthma, while Dolinar 2000 described the participants as having stable asthma. The Mitchell 1986 cohort had frequent asthma attacks and Otsuki 2009 enrolled patients prescribed an asthma controller medication. All studies included patients who had a health care utilisation visit in the past year (either ED or hospitalisation), except Dolinar 2000 who excluded patients with an exacerbation requiring a visit to the ED in the previous year. A table of control group rates for ED visits and hospitalisations provides an indicator of severity and can be found in Table 4.

2. Control group event rates.

| Study | Control group risk EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT VISITS | Control group risk HOSPITALISATIONS (period reported, from baseline) |

| Brown 2006 | 38% (0 to 6 months) | ‐ |

| Butz 2006 | 47% (0 to 6 months) | 13% (0 to 6 months) |

| Dolinar 2000 | 10% (0 to 6 months) | ‐ |

| Fisher 2009 | 54% (0 to 2 years) | 59% (0 to 2 years) |

| Gorelick 2006 | 38% (0 to 6 months) | ‐ |

| Mitchell 1986 Europeans | 5% (0 to 6 months) | 21% (6 months) 16% (6 to 18 months) |

| Mitchell 1986 Polynesians | 13% (0 to 6 months) | 27% (6 months) 33% (6 to 18 months) |

| Otsuki 2009 | ‐ | 17% (6 months) 12% (12 to 18 months) |

| Seid 2010 | 15% (3 to 9 months) | 8% (3 to 9 months) |

The trials enrolled participants with a range of age groups. Three trials included infants less than two years which was outside of the inclusion criteria for this review. However, we included them as the majority of participants would have been over two years (Dolinar 2000; Brown 2002; Brown 2006). The majority of participants were children (up to 12 years old) rather than teenagers (12 to 18 years old).

The studies were predominantly conducted in urban or suburban settings involving vulnerable populations. The exceptions were Dolinar 2000 where the majority of families were above the low‐income level in Canada and Mitchell 1986 who recruited and analysed data for European and Polynesian children separately, since the Polynesian children were previously reported to have lower socioeconomic status and differences in asthma management and outcomes (Mitchell 1981; Mitchell 1984). Eight studies reported high levels of participants on Medicaid or public insurance (Brown 2002; Butz 2006; Gorelick 2006; Galbreath 2008; Fisher 2009; Otsuki 2009; Butz 2010; Seid 2010) or attending subsidised community clinics (Seid 2010). Eight studies included greater than 50% participants from ethnic minorities (Brown 2002; Butz 2006; Gorelick 2006; Galbreath 2008; Fisher 2009; Otsuki 2009; Butz 2010; Seid 2010), one study was conducted in a predominantly white population (Brown 2006) while the remaining three trials did not report the ethnic groups of participants.

Interventions

A summary of the educational interventions for each study is displayed in Table 3. Eight studies included four to six‐weekly to monthly home visits that generally lasted 30 to 60 minutes each (Mitchell 1986; Butz 2006; Gorelick 2006; Galbreath 2008; Kamps 2008; Otsuki 2009; Butz 2010; Seid 2010), one study delivered eight home visits lasting 90 minutes (Brown 2002), while another three studies only had one or two home visits (Dolinar 2000; Brown 2006; Fisher 2009). Three studies (Gorelick 2006; Galbreath 2008; Fisher 2009) included additional telephone sessions. The educator who provided the home sessions assisted in one or more primary care clinic visits in two studies (Brown 2006; Butz 2010).

The shortest follow‐up was three months (Dolinar 2000) followed by two trials with six months follow‐up (Brown 2006; Gorelick 2006), while the remaining nine studies collected follow‐up data for nine to 24 months from initial enrolment.

Five studies employed nurses to deliver asthma education (Mitchell 1986; Dolinar 2000; Brown 2002; Brown 2006; Butz 2006) and four studies involved either nurses, social workers or health educators (Gorelick 2006; Fisher 2009; Otsuki 2009; Butz 2010). Galbreath 2008 used nurses for the telephonic intervention and employed pulmonary therapists for the home visits, while Kamps 2008 employed licensed psychologists or master's level psychology students. Seid 2010 provided in‐home asthma education through bachelor’s level, bilingual, bicultural home visitors, and the problem‐skills training intervention component was delivered by bilingual and bicultural bachelor’s or master’s level health educators.

All programmes provided basic education on the concepts of asthma, such as pulmonary anatomy and physiology as well as the disease process. Six of the studies provided printed materials (such as booklets) and/or homework to complete after the educational sessions (Dolinar 2000; Brown 2002; Gorelick 2006; Kamps 2008; Otsuki 2009; Seid 2010). All programmes reviewed asthma medications along with inhaler technique and reviewed strategies for self management of the disease. One study used electronic devices to provide objective feedback to inform patients and families on medication adherence (adherence monitoring arm of Otsuki 2009), while another study kept track of nebuliser use electronically to measure study outcomes (Butz 2006). Galbreath 2008 provided active disease monitoring and management via scheduled telephone calls and access to a 24‐hour hotline. Written action plans were reviewed and/or provided in 10 out of 12 studies (Dolinar 2000; Brown 2002; Butz 2006; Brown 2006; Gorelick 2006; Galbreath 2008; Fisher 2009; Otsuki 2009; Butz 2010; Seid 2010). All but one study (Otsuki 2009) specifically mentioned educational interventions that reviewed asthma triggers, measures to reduce environmental allergens or both.

Most interventions were based on already‐existing asthma educational programmes, some founded on theories of learning. Brown 2002 used the Wee Wheezers programme (Wilson 1996b), developed using principles of social learning theory by a team of paediatricians, pulmonologists, psychologists, public health educators and educational video specialists. Brown 2002 modified the scripts and handouts to make them culturally appropriate and target low‐literacy level parents. Butz 2006 also made use of Wee Wheezers as well as the A+ Asthma Club Programme (Schneider 1997), the latter of which uses the PRECEDE (Predisposing, Reinforcing, Enabling Constructs in Educational Diagnosis and Evaluation) planning model. Additional programmes included the Air Force Asthma Program developed by the Ontario Lung Association (Dolinar 2000), the National Jewish Asthma Disease Management Program and Pulmonary Therapies LLC programme (Galbreath 2008), the Fight Asthma Milwaukee Allies (Gorelick 2006), and the Air Wise Program and The Clubhouse Kids Learn Asthma interactive computer program (Kamps 2008). Butz 2010 designed an asthma communication education programme based on the chronic care model (Wagner 2001; Bodenheimer 2002) and other studies examining clinician‐parent‐child communication (Halterman 2001; Tates 2001). The community health workers in Fisher 2009 used the Transtheoretical Model to assess participants' readiness for change and adopted asthma management behaviours accordingly. They also used a "nondirective supportive style" in their interactions. Kamps 2008 used behaviour management techniques to promote adherence, specifically the Exchange Program for Improving Medication Adherence (Rapoff 1999). Similarly, Seid 2010 employed problem‐solving skill training based on a concept by D'Zurilla (D'Zurilla 1971; D'Zurilla 1986) and a protocol previously tested on mothers of children with cancer (Varni 1999). Seid 2010 based the care co‐ordination component of their intervention on the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation's Allies Against Asthma community health worker model (Friedman 2006). The NHLBI guidelines were explicitly stated as the basis of asthma management in five trials (Brown 2002; Brown 2006; Galbreath 2008; Fisher 2009; Seid 2010), while the Air Wise Program used in Kamps 2008 was affiliated with the NHLBI.

Three studies involved two intervention and one control group (Gorelick 2006; Otsuki 2009; Seid 2010). All intervention groups were included in this review except the intensive primary care linkage arm of the Gorelick 2006 trial, since there was no home education component.

Control groups

Control groups received routine care in nine trials, which may have involved asthma education but not provided in the home setting (Mitchell 1986; Dolinar 2000; Brown 2002; Brown 2006; Gorelick 2006; Galbreath 2008; Fisher 2009; Otsuki 2009; Seid 2010) and form the basis of the first comparison in this review. The remaining three studies provided controls with home‐based general asthma education, while providing additional education for specific therapies or skills in the intervention group (nebuliser therapy education, asthma communication education and strategies to improve adherence to inhaled corticosteroids for Butz 2006, Butz 2010 and Kamps 2008, respectively). These three studies form the basis of our second comparison of education versus a less intensive educational intervention.

Compliance

The full intervention was delivered to over 70% of participants in all trials except Brown 2006 in which 39% of adults and children completed the programme.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes of the trials varied. For Brown 2006, it was time to first relapse for asthma (ED or unscheduled visit for asthma). Butz 2010 defined caregiver reported symptom days and nights over the past 30 days as the primary outcome; Butz 2006 looked at asthma severity, number of ED visits and medication usage (email communication with author); Dolinar 2000 used parental coping, caregiver perception of change and quality of life; Fisher 2009 reported hospitalisations at 12 months; Galbreath 2008 chose time to first asthma‐related events, quality of life and rates of healthcare utilisation; Gorelick 2006 used proportion of patients experiencing an ED visit over six months; Kamps 2008 reported adherence to inhaled corticosteroids using an electronic monitor (MDILog); Otsuki 2009 chose ED visits; and Seid 2010 measured health‐related quality of life. Two studies did not define primary outcomes (Mitchell 1986; Brown 2002).

For full details of outcomes reported in each study, see Characteristics of included studies.

We obtained additional data from three trialists (Butz 2006; Gorelick 2006; Butz 2010).

Aims

The overall aims of the studies varied (Table 5), testing different interventions to improve various outcomes (listed in the section above).

3. Aims of studies.

| Study | Aims |

| Mitchell 1986 | In New Zealand readmission rates are higher in Polynesian children than in European children. The study was designed to find out if community child health nurses in the patients home could reduce school absenteeism, encourage visits to the GP and reduce the number of readmissions to hospital and teach parents when and how to seek medical help for an attack not responding to usual treatment. |

| Dolinar 2000 | Does home‐based education resource influence parental coping, perception of asthma change and quality of life? |

| Brown 2002 | "A home‐based program may be the most developmentally appropriate and ecologically valid methods of delivering asthma education to low income inner city families". Wanted to evaluate efficacy in terms of parental participation and effectiveness in terms of decreasing morbidity and increasing the caregiver's quality of life and asthma management skills. |

| Butz 2006 | "Low‐income minority children have disproportionately high morbidity and mortality rates" and "tend to rely on hospital emergency rooms as primary source of asthma care". Therefore aimed to decrease ED visits/hospital admissions by helping parents understand when the child's asthma was worsening and train them specifically in home nebuliser use. |

| Gorelick 2006 | Evaluated the impact of educating children in the emergency department and then following up with home‐based education interventions compared to standard care alone. |

| Brown 2006 | A "structured comprehensive asthma education program delivered by an experienced asthma nurse educator within a local asthma coalition would be an effective method of reducing asthma relapse in patients who had moderate‐sever persistent asthma." |

| Galbreath 2008 | A telephonic and home‐visiting asthma education delivered by a respiratory therapist designed to decrease healthcare utilisation and generate cost savings. |

| Kamps 2008 | Designed to increase adherence to asthma treatment regimens. |

| Otsuki 2009 | To evaluate a feedback of electronically monitored adherence and education programme in reducing ED visits ad asthma mediation adherence, symptoms, hospitalisations and courses of oral steroids. |

| Fisher 2009 | Hypothesised that "community health workers may help reduce disproportionate asthma health burden among children from low‐income families". Used a non‐professional asthma coach to try and reduce rehospitalisation. |

| Seid 2010 | Problem‐solving may be useful in helping families, especially lower socioeconomic status families improve their asthma management behaviours to improve quality of life. |

| Butz 2010 | Hypothesised that a programme designed to improve clinician‐caregiver communication would be associated with reduced symptom days and nights and increased compliance with appropriate controller medication in inner‐city children. |

ED: Emergency Department

Excluded studies

We recorded the reasons for exclusion of 160 studies after retrieving the full‐text documents (see Characteristics of excluded studies). We excluded 26 studies aimed primarily at environmental remediation or which supplied participants with allergen‐reducing materials (such as mattress encasings and HEPA (high‐efficiency particulate air) filters); 25 studies conducted on adults; 66 studies delivering the education outside the home; 12 studies providing education primarily via multimedia but without face‐to‐face; in‐person education delivered in the home; three studies delivering an exercise‐based intervention; three studies providing a low‐intensity information‐only intervention; one study using a self help kit; one study involving a decision‐making programme aimed at reducing substance misuse; three studies aimed at education physicians or nurses; and one study for multiple reasons (randomisation not described, location of education delivered not specified, no extractable data and unable to contact the study author). Nineteen studies were not randomised controlled trials.

There was one potentially eligible trial identified that is still ongoing (Rand 2006)

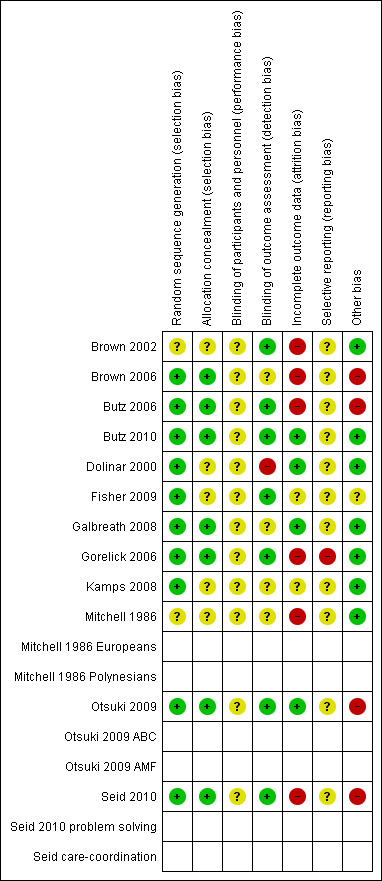

Risk of bias in included studies

Full details of risk of bias judgements can be found in Characteristics of included studies. Graphical representations of our judgements of the risk of bias can be found in Figure 2.

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Ten studies reported full details of adequate sequence generation and we judged them to be of low risk of bias (Dolinar 2000; Butz 2006; Brown 2006; Gorelick 2006; Galbreath 2008; Kamps 2008; Fisher 2009; Otsuki 2009; Butz 2010; Seid 2010). Two studies were reported as randomised, but gave no description of the methods used and we therefore judged them to be at unclear risk of bias (Mitchell 1986; Brown 2002).

Seven studies were low risk of bias with full details of allocation sequence concealment reported (Brown 2006; Butz 2006; Gorelick 2006; Galbreath 2008; Otsuki 2009; Butz 2010; Seid 2010). The author confirmed allocation concealment in one study (Butz 2006). There were insufficient details for the remaining five studies for us to reach a firm conclusion so we judged them to be at unclear risk of bias (Mitchell 1986; Dolinar 2000; Brown 2002; Kamps 2008; Fisher 2009).

Blinding

The nature of the intervention precludes the possibility of blinding patients or the educator and therefore all the studies were judged to be at unclear risk of performancebias. However, it is possible to blind the people who collected or analysed the data. We judged seven studies to be at low risk of bias with respect to blinding of data collectors (Brown 2002; Butz 2006; Gorelick 2006; Fisher 2009; Otsuki 2009; Butz 2010; Seid 2010). Three studies did not describe blinding, so we judged them to be at unclear risk of bias (Mitchell 1986; Brown 2006; Kamps 2008). Dolinar 2000 was high risk of bias as it was described as non‐blinded. The lack of blinding would likely have a greater impact on the more subjective outcomes (e.g. quality of life) than more objective measures (e.g. ED visits).

Incomplete outcome data

We judged four studies to be at low risk of bias due to incomplete outcome data as indicated by withdrawals/losses to follow‐up in Table 6 (Dolinar 2000; Galbreath 2008; Otsuki 2009; Butz 2010). Butz 2010 and Dolinar 2000 had similar losses to follow‐up in both education and control groups, Galbreath 2008 obtained comprehensive health care utilisation data for 99% of participants and Otsuki 2009 had consistent losses to follow‐up across treatment arms which averaged around 10%. We judged six studies to be at high risk of bias with respect to incomplete outcome data (Mitchell 1986; Brown 2002; Brown 2006; Butz 2006; Gorelick 2006; Seid 2010). Brown 2002 had a high number of withdrawals from the treatment arm (n = 6) compared to none on the control arm, Butz 2006 had unbalanced losses of pharmacy records, Brown 2006 had 21% lost to follow‐up in the intervention group at six months compared to six percent in the control group, Gorelick 2006 reported the baseline characteristics of those lost to follow‐up or with incomplete data (22%) but there were more lost in the treatment versus the control group, while Seid 2010 had high and unbalanced losses to follow‐up and refusal to comply, which we assume was related to the nature of the interventions. Mitchell 1986 did not mention how many people contributed data, so we judged this to be at a high risk of bias. The remaining two studies were at unclear risk of bias (Kamps 2008; Fisher 2009). Fisher 2009 unbalanced follow‐up survey data but reviewed hospital records for all patients. The risk of bias was unclear because records were only available from one hospital in the city, albeit the latter was where the majority of admissions likely occurred. Kamps 2008 was a small pilot study with poor follow‐up, so although the losses were balanced between arms, the reported data were on limited participants.

4. Completers/ withdrawals.

| Study | % completed full education programme | Partial completion | Completed no sessions | Lost to follow‐up | Withdrawals |

| Brown 2002 | 71% | 11% | 7% | ‐ | 11% |

| Brown 2006 | 38%* | 9% received only clinic visit* 15% received only home visit* |

39%* | Intervention group 21%

Control group 6% (reported for children) |

Not reported * these data are from both adults and children |

| Butz 2006 | Most completed | ‐ | ‐ | Nebuliser: 14% excluded from follow‐up (10% no pharmacy data, 2% died, 3% lost). SAE 23% excluded (18% no pharmacy data, 1% died, 4% lost) | Not reported |

| Butz 2010 | ‐ | More intense group received mean 3.29 out of 4 visits Control received mean 2.27 out of 3 visits |

‐ | More intense group 17% Control group 14% |

Not reported |

| Dolinar 2000 | 100% | ‐ | ‐ | 5% | 0 |

| Fisher 2009 | ‐ | ‐ | 4% (no substantive contact) | Hospitalisations available for all participants. 83% completed surveys |

Not reported |

| Galbreath 2008 | 70% completed at least 80% of the intervention ‐ although this was for adults and children | ‐ | ‐ | 35% | 2 |

| Gorelick 2006 | Average of 4 (out of 6) home visits per patient (average of 2 missed visits per patient); average 2.3 calls per patient | 72% had at least 1 home visit | ‐ | 22% | |

| Kamps 2008 | 100% | ‐ | ‐ | 2 months 33% 6 months 60% 12 months 67% |

3 |

| Mitchell 1986 | 68% | 26% | 6% | Not reported | Not reported |

| Otsuki 2009 | ABC 71%; AMF 63% | ‐ | ‐ | ˜10% | 1 person deceased in each group |

| Seid 2010 | 67% completed all 5 visits | Completed 4.0 (CC) and 3.8 (CC + PST) visits on average | ‐ | CC intervention: 20% lost (7% refused), PST intervention 32% lost (19% refused) | PST 19% and CC 6% "refused" |

ABC: Asthma Basic Care AMF: Adherence Monitoring with Feedback SAE: serious adverse event PST: problem‐solving skill training

For consideration of the number of patients withdrawing and those lost to follow‐up, please see Effects of interventions and Characteristics of included studies.

Selective reporting

We judged 11 studies to be at unclear risk of bias for selective outcome reporting since there was no published protocol (Mitchell 1986; Dolinar 2000; Brown 2002; Butz 2006; Brown 2006; Galbreath 2008; Kamps 2008; Otsuki 2009; Fisher 2009; Seid 2010; Butz 2010). Five trials (Butz 2006; Galbreath 2008; Otsuki 2009; Butz 2010; Seid 2010) were registered in clinicaltrials.gov but all had one or more secondary outcomes in the protocols that were not reported in the final publications, and were therefore deemed unclear risk of bias. The final study (Gorelick 2006) measured hospital admissions but did not report this in the results and the trialists were unable to provide these data through correspondence. We therefore judged Gorelick 2006 at high risk of selective reporting bias.

Other potential sources of bias

The main additional source of bias identified in these studies was recall bias for outcomes where the patient or parent had to report the number of events experienced over time. We judged seven studies to be at low risk of recall bias (Mitchell 1986; Dolinar 2000; Brown 2002; Gorelick 2006; Galbreath 2008; Kamps 2008; Butz 2010). Dolinar 2000 and Kamps 2008 only reported outcomes that by their nature have to be measured by self report and we therefore judged them to be at low risk of bias. Four studies reviewed medical records for healthcare utilisation (Mitchell 1986; Brown 2002; Galbreath 2008; Butz 2010) while Gorelick 2006 collected both self reported ED visits as well as those in their computerised tracking system. We judged Fisher 2009 to be an unclear risk, once again due to the retrieval of hospitalisations from one hospital only. We judged four studies to be at high risk of bias for outcomes that were self reported, but could have been verified (e.g. ED visits, hospitalisations; Butz 2006; Brown 2006; Otsuki 2009; Seid 2010). Otsuki 2009 compared self reported adherence to pharmacy records for inhaled corticosteroid usage and showed that the self reports overestimated adherence compared to pharmacy records, which highlights the potential for recall bias in these situations and the need for collecting accurate data where possible.

Effects of interventions

Home‐based education versus usual care or a less intensive, non‐home‐based education

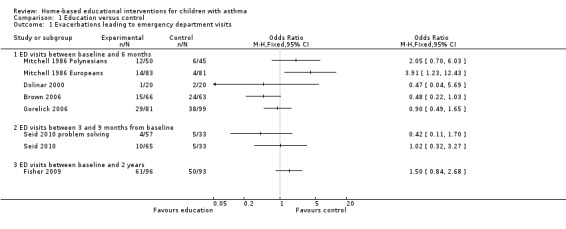

Primary outcome: Exacerbations leading to Emergency Department (ED) visits

Six studies involving 985 patients reported the number of patients with one or more asthma exacerbations resulting in ED visit(s) (Mitchell 1986; Dolinar 2000; Brown 2006; Gorelick 2006; Fisher 2009; Seid 2010). The studies were not pooled due to heterogeneity in the study populations, outcome definitions, follow‐up time and differences in the control group event rate (Table 4). Brown 2006 reported unscheduled urgent visits to a physician office and ED visits for asthma as a single outcome and Fisher 2009 reported the subset of ED visits that did not result in hospitalisations. Three studies measured outcomes at six months (Mitchell 1986; Brown 2006; Gorelick 2006), one reported data at three months (Dolinar 2000) and one at 24 months (Fisher 2009). Only one study (Mitchell 1986) showed a significant effect favouring controls over the intervention for the European children subgroup (Analysis 1.1). Seid 2010 reported the number of patients experiencing asthma exacerbations at three months and nine months from baseline. Seid 2010 also reported odds ratios for patients with ED visits adjusted for the baseline level of the outcome and covariates (including age, race/ethnicity, Spanish language and mother's education), which were not significant for either of the intervention groups compared to controls.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Education versus control, Outcome 1 Exacerbations leading to emergency department visits.

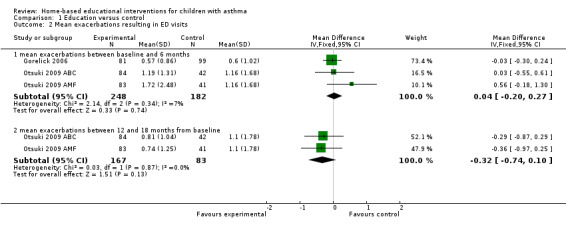

Three studies involving 525 patients reported the mean number of acute visits for asthma (Brown 2002; Gorelick 2006; Otsuki 2009). The pooled data for two studies on 430 people at six months was not statistically significant (mean difference (MD) 0.04; 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐0.20 to 0.27; Analysis 1.2). Brown 2002 reported only means without standard deviations and incorporated ED and clinic visits for acute asthma as a single outcome, so we could not pool these data. Although there was a significant decrease over time in the mean number of acute asthma visits at 12 months in both groups, there was no significant net treatment effect. Otsuki 2009 reported mean ED visits in the previous six months at six‐month intervals from 0 to 18 months of follow‐up. At 18 months, the results (for the previous six months) revealed no significant difference between either intervention groups (basic asthma education or intervention with additional adherence monitoring with feedback) and the control group. However, the authors analysed the decrease in ED visits over the entire 18‐month period, and showed that the rate of decrease in ED visits over time was faster in both the combined treatment groups and the adherence feedback group alone than the control group (Otsuki 2009).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Education versus control, Outcome 2 Mean exacerbations resulting in ED visits.

Galbreath 2008 reported an adjusted annual asthma exacerbation rate per patient leading to ED visits showing no significant difference between groups.

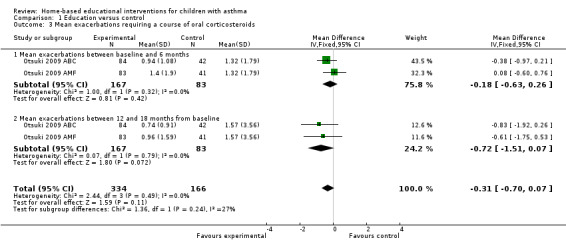

Primary outcome: Exacerbations requiring oral corticosteroids (OCS)

One study involving 250 patients reported the mean number of exacerbations requiring a course of oral corticosteroids every six months from baseline to 18 months (Otsuki 2009). At six and 18 months, the pooled results for the two intervention arms (basic education and adherence monitoring) were not statistically significant (MD ‐0.18; 95% CI ‐0.63 to 0.26 and MD ‐0.72; 95% CI ‐1.51 to 0.07 respectively; Analysis 1.3). However, the authors once again demonstrated that the rates of decrease in mean courses of OCS over 18 months follow‐up were faster for either intervention groups compared to usual care (Otsuki 2009). Galbreath 2008 reported no statistically significant difference in the number of oral corticosteroid bursts, but the numbers were not provided to allow pooling of results.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Education versus control, Outcome 3 Mean exacerbations requiring a course of oral corticosteroids.

Secondary outcome: Quality of life

Five studies on 727 participants measured quality of life (Dolinar 2000; Brown 2002; Gorelick 2006; Galbreath 2008; Seid 2010). Given the difference in instrument scores and missing data in some trials, we present a narrative synthesis below.

Three studies involving 331 patients used the Paediatric Asthma Caregiver's Quality of Life Questionnaire (PACQLQ) to assess quality of life (Dolinar 2000; Brown 2002; Galbreath 2008). Juniper et al developed both the PACQLQ (Juniper 1996a) and Paediatric Quality of Life Questionnaire (PAQLQ; Juniper 1996b), which were validated as evaluative and discriminative instruments for children seven to 17 years old. The PAQLQ contains 23 items in the domains of activity limitation, symptoms and emotional function, administered to the child (Juniper 1996b) while the PACQLQ contains 13 items concerning activity limitations and emotional function administered to the caregiver (Juniper 1996a). Brown 2002 reported improvement in scores among the caregivers of both intervention and control arms. However an intervention effect was only noted in the younger patient subgroup (one to three years old). The remaining two studies failed to show a significant effect of the intervention as measured by the PACQLQ (Dolinar 2000; Galbreath 2008) although in Galbreath 2008 the quality of life improved over time in all groups.

Galbreath 2008 also administered the PAQLQ to children. Galbreath 2008 reported no statistically significant group differences in the quality of life scores at follow‐up (adjusted for baseline differences in demographics; P = 0.40), although quality of life improved from baseline in both groups. Seid 2010 reported overall health‐related quality of life in 165 children using the PedsQL Total (23 items on physical and psychosocial health) administered to the parent and, if applicable, the child. Seid 2010 also reported quality of life using the PedsQL Asthma (28 items on asthma symptoms, treatment problems, worry and communication) administered to the parent and, if applicable, the child. There was no statistically significant difference in the primary outcome PedsQL Total for parent‐reported symptom scores for control versus either intervention groups at three months. At nine months, there was no statistically significant difference between control versus the care co‐ordination intervention, but there was a statistically significant difference in control versus care co‐ordination with additional problem‐solving skills training in the PedsQL Total administered to parents (adjusted MD 4.05; 95% CI 0.63 to 7.4).

Gorelick 2006 had parents/caregivers complete the Integrated Therapeutics Group Child Asthma Short Form (ITG‐CASF), containing 10 items specific to asthma, at baseline and six months. This tool was previously validated for use in the ED (Gorelick 2004). The mean change in scores from baseline improved in both intervention and control groups but the difference between groups was not statistically significant.

Secondary outcome: Symptoms

Four studies involving 711 participants reported information relating to asthma symptoms, but we were unable to pool data for this outcome due to missing data, the heterogeneity of tools used to measure symptoms and underlying differences in the control group exacerbation rate (Table 4) (Brown 2002; Galbreath 2008; Otsuki 2009; Seid 2010). Brown 2002 reported the mean for asthma symptom score (using a sub‐scale of the PAQLQ) and the mean symptom‐free days. Although follow‐up analyses were able to show that there was a benefit for symptoms and symptom‐free days in the younger children (one to three years old) and not in the older children, overall there was no treatment effect on either outcome.

Galbreath 2008 measured symptom scores using the Lara Asthma Symptom Scale (LASS) and stated that symptom scores decreased over time in all groups, but did not show a significant treatment effect. Otsuki 2009 measured caregiver reports of symptoms every six months (baseline, 6, 12 and 18 months), calculating the mean asthma symptoms in the previous 30 days. None of the mean values for symptom scores were different at each time point between either intervention groups versus controls, but Otsuki 2009 reported differences in the rate of improvement in symptoms over time for the asthma basic care versus control group ‐ the intervention improving faster than the control group over the first 12 months. Using ordinal scales, Seid 2010 reported the percentage of children experiencing daytime symptoms (< twice a week, three to six times a week and every day) and night‐time symptoms (< once/week, > once/week) at baseline, three months and nine months after baseline. The odds ratios adjusted for baseline levels and covariates showed no significant different between either intervention groups compared with controls for daytime symptoms, but statistically improved night‐time symptoms at three months but not nine months for the care co‐ordination/problem‐solving skills group compared to controls (odds ratio (OR) 0.33; 95% CI 0.13 to 0.82; Seid 2010).

Secondary outcome: Night‐time awakening

No study reported night‐time awakening.

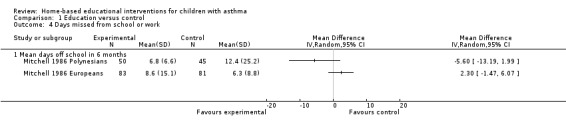

Secondary outcome: Days missed from school

One study with 259 participants reported no statistically significant difference between groups in the number of school days missed (Mitchell 1986; Analysis 1.4). One study combining 239 adults and children reported on days missed from school or work, also showing no group difference (Brown 2006).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Education versus control, Outcome 4 Days missed from school or work.

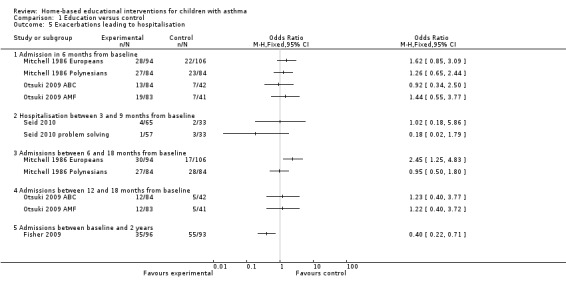

Secondary outcome: Hospitalisations

Five studies on 1012 participants reported the number of patients experiencing one or more hospitalisations (Mitchell 1986; Dolinar 2000; Fisher 2009; Otsuki 2009; Seid 2010). However, the data were not combined due to clinical heterogeneity and follow‐up periods (Analysis 1.5). Fisher 2009 demonstrated reduced hospitalisations at 24 months in the intervention group in (OR 0.4; 95% CI 0.22 to 0.71) and the Europeans in Mitchell 1986 had increased admissions between six and 18 months (OR 2.45; 95% CI 1.25 to 4.83). All the other studies reported no group difference. None of the patients in Dolinar 2000 had a hospital admission.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Education versus control, Outcome 5 Exacerbations leading to hospitalisation.

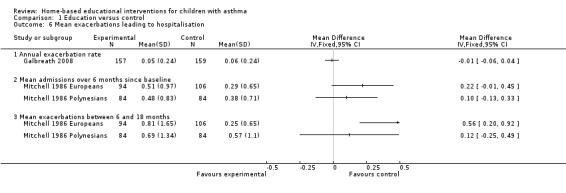

Two studies on 569 participants reported the mean hospitalisations, although we did not pool due to heterogeneity (Mitchell 1986; Galbreath 2008). Mitchell 1986 had heterogeneity between study populations so we did not to pool this outcome (Analysis 1.6). Mitchell 1986 reported mean hospital admissions at both six months and between six and 18 months. Only the European children showed a significant effect favouring controls in the latter time period. Galbreath 2008 reported no significant treatment effect for the adjusted rates of hospital admissions per patient per year.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Education versus control, Outcome 6 Mean exacerbations leading to hospitalisation.

Secondary outcome: Lung function

No studies reported this outcome.

Education versus another type of home‐based education

Three studies reported on a home‐based education intervention compared to another, less intensive type of home‐based education as a control group (Butz 2006; Kamps 2008; Butz 2010).

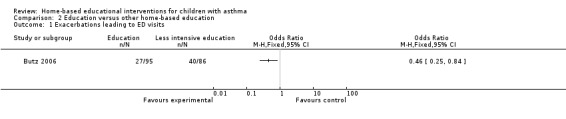

Primary outcome: Exacerbations leading to ED visits

Butz 2006 showed fewer patients in the nebuliser‐targeted education group (27/95) reporting at least one ED visit at six months compared to the less intensive education group (40/86), which was a statistically significant (OR 0.46; 95% CI 0.25 to 0.84; Analysis 2.1). Butz 2010 reported no statistically significant difference between groups for the decrease in mean number of ED visits at 12 months.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Education versus other home‐based education, Outcome 1 Exacerbations leading to ED visits.

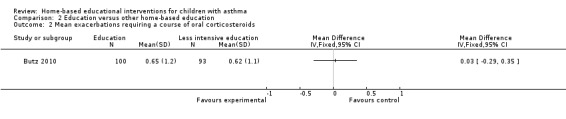

Primary outcome: Exacerbations requiring oral corticosteroids (OCS)

Butz 2006 reported no statistical differences between intervention and control groups for the mean number of oral corticosteroid prescriptions at 12 months. Butz 2010 reported no significant differences for the mean number of oral corticosteroids filled at 12 months (Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Education versus other home‐based education, Outcome 2 Mean exacerbations requiring a course of oral corticosteroids.

Secondary outcome: Quality of life

Kamps 2008 measured physical function and psychosocial health with the generic PedsQL and asthma‐related quality of life with the PedsQL Asthma Module (with sections on asthma symptoms, treatment problems, worry, and communication) administered to both child and caregiver. No significant treatment effects were observed using repeated measures analyses of covariance and pooled time series analysis using data from baseline (n = 15), two (n = 10), six (n = 6) and 12 months (n = 5) (Kamps 2008).

Secondary outcome: Symptoms

Kamps 2008 measured caregiver‐reported and child‐reported asthma symptoms using PedsQL Asthma Module and found no significant difference in treatment effect at baseline and two, six and 12 months. Repeated‐measures ANCOVAS did not yield significant interactions or main effects for symptom scores. Butz 2010 reported no statistically significant differences between groups for the decrease in mean number of symptoms during both the day and at night measured with a Likert‐type scale at 12 months. We did not pool the data due to differences in measurement tools.

Secondary outcome: Night‐time awakening

No study reported this outcome.

Secondary outcome: Days missed from school

No study reported this outcome.

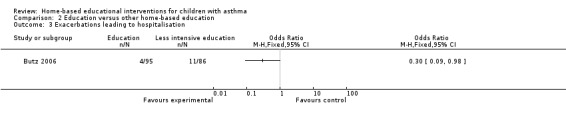

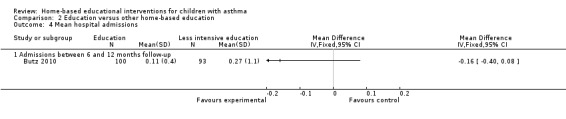

Secondary outcome: Hospitalisations

A single study on 181 participants reported the number of patients experiencing at least one hospitalisation for the previous six months at 12 months follow‐up (Butz 2006).There were fewer hospitalisations in the group receiving the additional nebuliser use training compared to the less intensive education, which was a statistically significant difference (OR 0.30; 95% CI 0.09 to 0.98; Analysis 2.3). Butz 2010 reported no difference in the mean number of hospitalisations at 12 months (Analysis 2.4).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Education versus other home‐based education, Outcome 3 Exacerbations leading to hospitalisation.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Education versus other home‐based education, Outcome 4 Mean hospital admissions.

Secondary outcome: Lung function

Kamps 2008 did not report any significant differences in lung function (FEF (forced expiratory flow) 25% to 75%) using repeated measures analyses of covariance and pooled time series analysis at two months (n = 10), six months (n = 6) and 12 months (n = 6).

Cost

Galbreath 2008 reported the cost of the four home visits to be USD 206 and USD 531 for the telephonic intervention, totaling USD 737 per participant.

Withdrawals

We decided not to pool these data due to heterogeneity in the trial design (such as the number of education sessions) and reporting of the number of withdrawals. Instead we created Table 6 to reflect the number of patients who completed all or some of the education, patients lost to follow‐up and those who withdrew. This table should be viewed and interpreted with caution. Each study had its own definition of completing the programme and in some case people may have missed some sessions yet still be registered as completing the programme. The programmes also varied in number of sessions.

Subgroup analysis

We were unable to perform any of the prespecified subgroup analyses due to the lack of studies. Even if we had more included studies, performing subgroup analysis would be unwise due to the heterogeneity in the studies. We could not subgroup by age as most studies were on two to 12 year olds, except for three studies which included a range of ages spanning childhood and adolescence (Brown 2006; Gorelick 2006; Galbreath 2008). None of the studies could be divided into mild/moderate versus severe as all included children had a range of asthma severities. Fisher 2009 was the only intervention running for longer than six months. We had planned to subgroup by physician or nurse versus community health worker. However, all studies employed nurses combined with either a social worker, a trained health educator or a pulmonary therapist, except Fisher 2009 who employed a community health worker, Kamps 2008 who used a psychologist or a psychology graduate student, Otsuki 2009 an asthma educator, and Seid 2010 who employed bilingual, bicultural graduate asthma visitors.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We included 2342 patients from 12 trials in this review. Of these, eleven trials were conducted in North America. Ten studies were in urban or suburban settings involving vulnerable populations. We summarised the components of the home‐based educational interventions in Table 3. We were unable to pool many of the outcomes due to clinical heterogeneity of the populations, interventions and timing of outcome assessment. The control event rates for Emergency Department (ED) visits and hospitalisations were quite different between trials. It is possible that trials with a higher control group event rate (poorly controlled asthma) would more likely achieve a decrease in admissions/ED visits, leading to difficulties in pooling (see Table 4 and further discussion below). Overall the effect of home‐based education is heavily dependent on the context of the trial (including but not limited to; aims of study, focus of the education, characteristics of the population) so deriving and interpreting average outcomes across these studies is not meaningful.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Implementation, feasibility and applicability of home‐based educational interventions

Many of the included studies tested commercially‐available asthma educational interventions covering similar programme topics, although these were delivered differently and with different emphasis on components of education. These studies showed that while home‐based interventions are feasible, additional resources and trained personnel are required, which may not be easily applied in real‐world settings, especially without adequate financial support. None of the studies analysed cost‐effectiveness. Economic data may strengthen the case for such interventions to be included in policy and healthcare budgets, concurrent with more evidence supporting clinical effectiveness. Administrators and policy‐makers may want to consider whether children with asthma and their caregivers are able to attend asthma clinics to receive education or whether some families can only be reached by visiting their home.

Our review also draws attention to another issue pertaining to the feasibility of interventions: the ability to retain participants. Although the participants who provided follow‐up data generally completed most of the education sessions, there appeared to be a higher attrition rate in the education group compared to the control groups in almost half of the trials. While high and unbalanced withdrawal rates are common in trials with high demands on participants' time, unbalanced withdrawal rates may also provide a biased indication of the effectiveness of home‐based education, depending on whether the intervention retained children who were more or less likely to benefit than those who dropped out.