Abstract

In the cornea, the epithelial basement membrane (EBM) and corneal endothelial Descemet’s basement membrane (DBM) critically regulate the localization, availability and, therefore, the functions of transforming growth factor (TGF)β1, TGFβ2, and platelet-derived growth factors (PDGF) that modulate myofibroblast development. Defective regeneration of the EBM, and notably diminished perlecan incorporation, occurs via several mechanisms and results in excessive and prolonged penetration of pro-fibrotic growth factors into the stroma. These growth factors drive mature myofibroblast development from both corneal fibroblasts and bone marrow-derived fibrocytes, and then the persistence of these myofibroblasts and the disordered collagens and other matrix materials they produce to generate stromal scarring fibrosis. Corneal stromal fibrosis often resolves completely if the inciting factor is removed and the BM regenerates. Similar defects in BM regeneration are likely associated with the development of fibrosis in other organs where perlecan has a critical role in the modulation of signaling by TGFβ1 and TGFβ2. Other BM components, such as collagen type IV and collagen type XIII, are also critical regulators of TGF beta (and other growth factors) in the cornea and other organs. After injury, BM components are dynamically secreted and assembled through the cooperation of neighboring cells—for example, the epithelial cells and keratocytes for the corneal EBM and corneal endothelial cells and keratocytes for the corneal DBM. One of the most critical functions of these reassembled BMs in all organs is to modulate the pro-fibrotic effects of TGFβs, PDGFs and other growth factors between tissues that comprise the organ.

Keywords: Epithelial basement membrane, Basement membrane assembly, Regeneration, Laminins, Collagen type IV, Nidogens, Perlecan, Integrins, Dystroglycan, TGF beta, PDGF, KGF, HGF, Epithelial barrier function, Descemet’s membrane, Cornea

Introduction

Basement membranes (BMs) are sheetlike structures which associate with epithelial cells of the cornea, conjunctiva and skin, corneal endothelial cells, and endothelial cells of blood vessels [1–4]. They also surround muscle, fat and Schwann cells [1–4]. They often can be recognized morphologically by their characteristic appearances in transmission electron microscopy (TEM), indicating the presence of a mature basement membrane [5]. Although the actual appearance of lamina lucida and lamina densa in TEM may be an artifact of fixation [6], this classical morphology is indicative of a fully regenerated BM after injury [6–8]. BMs are recognized biochemically by their typical components—including laminins, nidogens, heparin sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) like perlecan and agrin, and collagen type IV [6] (Fig. 1). Most BMs are 50–100 µm thick, although specialized BMs, such as DBM, may be much thicker [9]. It will be useful to provide an overall summary of the components that contribute to the structure and function of BMs in all organs using the cornea as a paradigm.

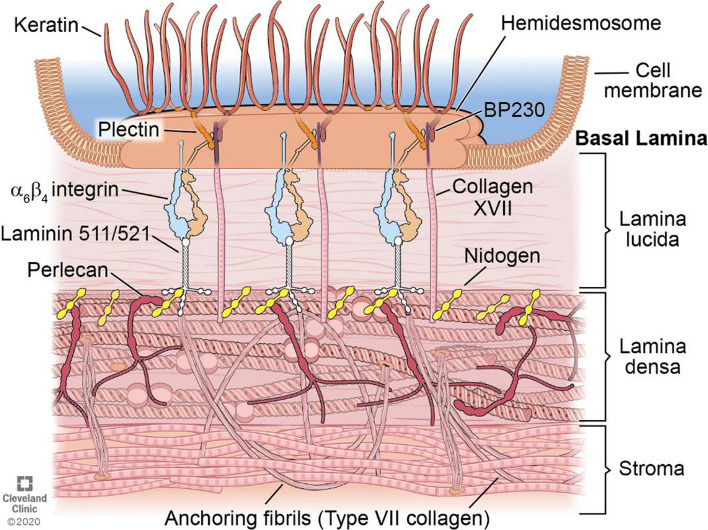

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the corneal EBM. The EBM underlies basal epithelial cells and overlies the stroma in the cornea connected by the hemidesmosome-anchoring filament complex. It is important to note there are other component molecules present in corneal EBM, such as collagen type IV, that are not included in this simplified diagram. HD hemidesmosome; BP230 bullous pemphigoid antigen 230. Reprinted with permission from Saikia et al. [79]

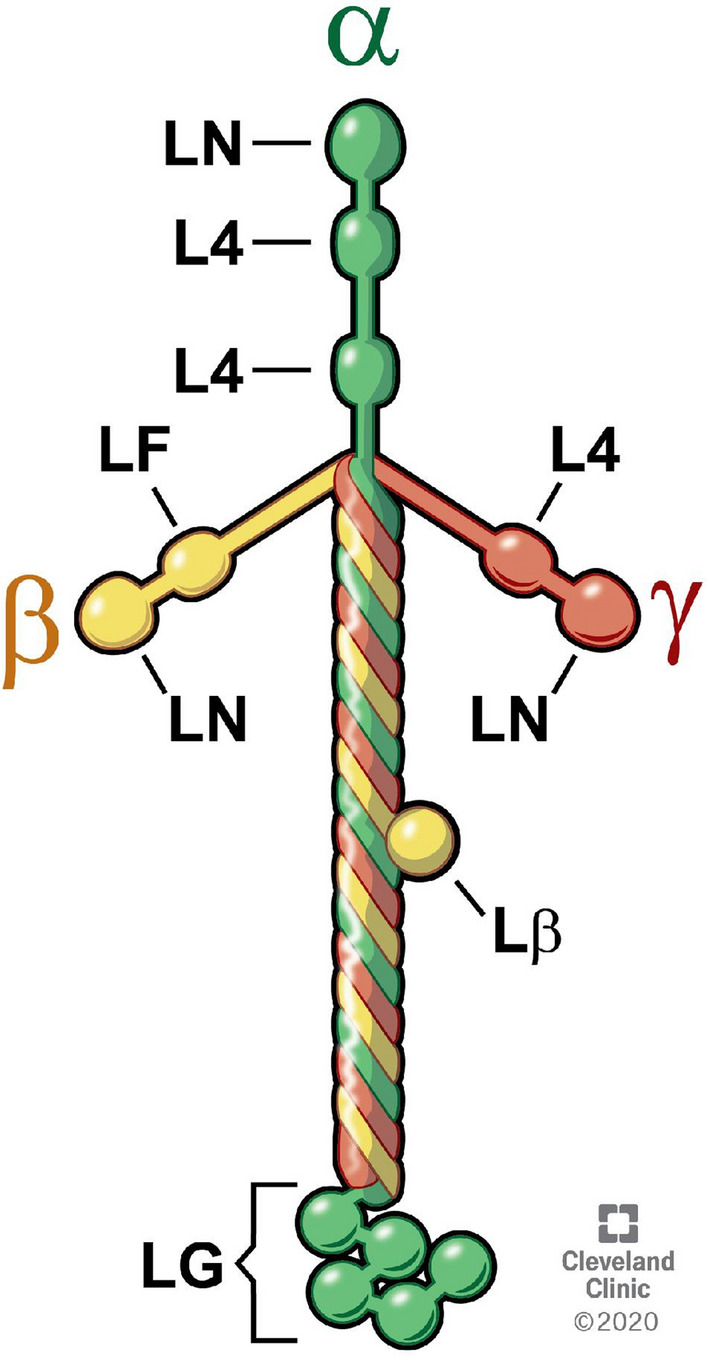

Laminins belong to a heterotrimer family, and each trimer is composed of one α, one β and one γ chain. Five α, three β and three γ chains that combine together to form over 15 laminin isoforms have been described in mice and humans [10, 11]. Laminin nomenclature uses Arabic numerals to identify the alpha, beta, and gamma chain numbers in the trimer [12]. For example, the laminin with the chain composition alpha-5 beta-2 gamma-1 is termed laminin-521. Certain laminins self-assemble and co-assemble to initiate the generation of mature BMs. Self- and/or co-polymerization is restricted to laminins containing “full-length” subunits (including α1, α2, α3B or α5, and β1 or β2, and γ1 or γ3) and is thought to occur while the laminin molecule is bound to receptors on the cell surface, including integrins and dystroglycan [1–3, 13, 14]. The cross-shape is characteristic of polymerizing laminins (Fig. 2), with the three short arms of the cross each derived from one of the α, β or γ chains, which interact with the short arms of adjacent laminin molecules in self-assembly and co-assembly [3]. The long arm of each laminin molecule is an alpha-helical coil of the α, β and γ chains, and the distal end of the long arm contains globular domains that are the major cell adhesion sites of the laminin molecules. Some laminins, such as 332, do not self-polymerize, but may be covalently linked to other laminins, such as 311 and 321 [15], and may be added to BMs needing strong attachment to hemidesmosomes, such as in the corneal epithelium [16]. Thus, immunohistochemistry for laminin 332 in the cornea shows it not only in the EBM, but also within the posterior epithelial layers (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Schematic of the structure of the typical heterotrimer laminin molecule (511, 512, or 111) with one α, β and γ chain. The three short arms of the cross-shaped molecule have a common domain structure and consist of laminin N-terminal (LN) domains through which the laminin molecule associates with surrounding laminins in the laminin network and L4 domains. The long arm of the laminin molecule (Lβ) is an alpha-helical coil of the α, β and γ chains. The α1 chain contains five laminin G-like (LG) domains that interact with cellular integrins and other receptors. Illustration by David Schumick, BS, CMI. Reprinted with the permission of the Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art & Photography, 2021

Fig. 3.

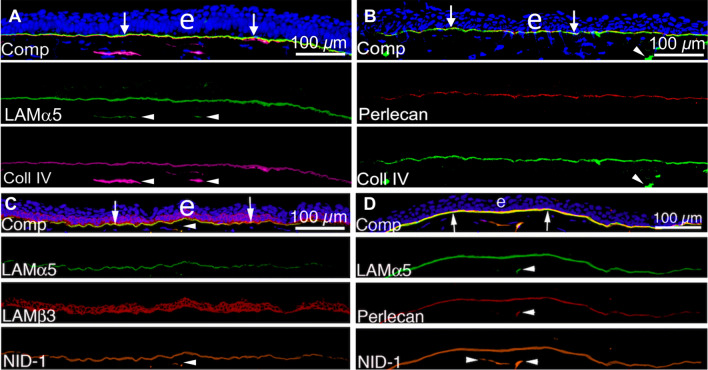

Localization of laminin alpha-5 (component in laminins 511/512), laminin beta-3 (component in laminin 332), perlecan, nidogen-1, and collagen type IV in unwounded corneal EBM. A Laminin alpha-5 and collagen type IV duplex IHC. B Perlecan and collagen type IV duplex IHC. C Laminin alpha-5, laminin beta-3, and nidogen-1 triplex IHC. D Laminin alpha-5, perlecan, and nidogen-1 triplex IHC. Comp is a composite of all components of each IHC with DAPI. Blue is DAPI-stained nuclei of all cells. (e) is the epithelium. Reprinted with permission from de Oliveira et al. [39]

Nidogens, also called entactins, are small glycoproteins that include two family members—nidogen-1 and nidogen-2 [17, 18]. Nidogen-1 and nidogen-2 are capable of interacting with several other extracellular matrix proteins—including laminins, perlecan, and collagen type IV [18, 19], and are, therefore, thought to stabilize the structure of the mature basement membrane containing these components (Fig. 3). Mice that lack expression of either nidogen-1 or nidogen-2 have normal life spans, and are relatively healthy and fertile [20, 21]. However, double knockouts of both nidogen-1 and nidogen-2 die before or just after birth and have multiple BM defects [22]. Thus, nidogen-1 and nidogen-2 can likely substitute for each other in BM assembly and function.

Heparin sulfate, chondroitin sulfate and dermatan sulfate are the three most prominent carbohydrate glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) associated with BMs [23]. These GAGs are complexed with a protein to form proteoglycans that are critical components in the structure and function of BMs [23, 24]. Perlecan (Fig. 3) and agrin are the two most common heparin sulfate proteoglycans found in most BMs [2, 26–29]. Perlecan consists of the core 470 kDa protein and three long chain (each approximately 70–100 kDa) GAGs that are most often heparin sulfate but also can be chondroitin sulfate [23]. Perlecan contains five distinct domains, including one region that is comprised of Ig-like repeats, that are sites of interaction with several other matrix molecules including nidogens, fibronectin, heparin, dystroglycan and collagen type IV [26]. Perlecan will be a focus of this review due to its critical function in modulating the localization of pro-fibrotic TGFβs. Agrin is another widely expressed BM proteoglycan that consists of an approximately 220 kDa core protein and two side chains that carry heparan sulfate and/or chondroitin sulfate [23]. Agrin is prominent in the neuromuscular junctions, muscular BMs, and glomerular BMs [23, 25]. Proteoglycans are not only structural components of BMs but also regulate biological functions, including filtration through basement membranes and the binding and function of growth factors and protease inhibitors [23].

Collagen type IV, the most abundant collagen of BMs (Fig. 3), is composed of six α chains named α1 to α6 that assemble into heterotrimers. Three major type IV collagens, each a heterotrimer, are present in different BMs [30–32]. The most common trimer consists of two α1 and one α2 chains and is a component in most BMs. The α3α4α5 and α5α5α6 heterotrimers have restricted distributions—notably in the eyes, renal glomeruli, neuromuscular junctions, and inner ears [30, 31]. The expression of collagen type IV isomers may vary topographically within the tissue of an organ, as has been elegantly demonstrated in the cornea [32]. The unique structure of collagen type IV contains segments that make it more flexible than other collagen types and capable of forming network sheets characteristic of BMs [33]. Nidogens and other BM components, including perlecan, bind to collagen type IV to crosslink the collagen type IV network to the laminin network in the mature BMs (Fig. 3). Collagen type IV has a critical role in binding TGFβ that will be discussed in greater detail later in this review.

While collagen type IV is the major collagen in most BMs, other collagens are often present, including collagen types VI, VII, XV, XVII, XVIII and XIX [34, 35], and the proportions of each of these collagens vary between BMs in different organs. These collagens likely participate in the organ-specific functions of BMs and some of these other collagens, for example collagen type XVIII, likely are involved in the modulation of TGFβ associated with fibrosis [36]. In addition, some BMs, especially BMs in blood vessels, contain collagen types I and III as prominent components [37].

Basement membrane modification and degradation, and the release and activation of TGFβ and other modulators

Injuries, infections, inflammatory processes, and some diseases are associated with the cellular release and/or activation of proteins that modify and/or degrade the extracellular matrix and basement membranes. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) that now number at least 25 are proteases that collectively can degrade all ECM proteins, including all the components of BMs, and have been extensively reviewed [38]. One hypothesis forwarded to explain defective perlecan incorporation into the EBM of fibrotic corneas that will be discussed later in this review is that excessive production and/or activation of MMPs degrades perlecan produced by corneal fibroblasts during EBM regeneration [39]. It’s become apparent, however, that another important function of MMP is the release and/or activation of cytokines, growth factors, chemokines, many of which—such as TGFβs—are stored as inactive pro-forms in BMs and other ECM [38, 40]. These activated modulators coordinate the cellular and immunological responses to injury. Since unneeded activation of the MMPs would be destructive, they are tightly modulated by transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation, tissue or cell type of release that controls localization, proteolytic activation of the pro-enzymes, and the activity of inhibitors, such as tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases (TIMPs) and non-specific protease inhibitors [41]. Many MMPs, including all membrane bound MMPs, are activated by furins, which are transmembrane serine proteinase in the trans-Golgi network [42]. The others can be activated in vitro by serine proteases, such as tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA), and plasminogen after its activation by cleavage to plasmin [38]. These MMP activators, and the MMPs themselves, can be produced by many cells, including tissue cells and immune cells (monocytes, lymphocytes, and macrophages) [43]. For example, in the cornea numerous MMPs and many of the activators are produced by each corneal cell type and invading inflammatory cells and are present in the tears of wounded corneas [44–47]. It remains unclear how the activities of the MMPs and their activators and inhibitors are orchestrated in injuries, infections, diseases in the cornea and other organs to degrade ECM and modulate regulatory factors [44]. There appears to be major overlap in functions since knockout models of MMPs, their activators and inhibitors commonly have little or no phenotype [38]. For example, collagen type IV can be degraded by gelatinases, stromelysins, matrilysins and macrophage metalloelastase [41].

ECM degradation by MMPs also releases non-covalently bound growth factors and cytokines and thereby increases their bioavailability at the site of injury or infection. A good example that is highly relevant to fibrosis is the release and activation of TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 after injury or infection or in diseases. An extensive review of this process and the many other activators of the TGFβs in the cornea and other organs was recently published [40]. Briefly, in the cornea, TGFβs produced by epithelial and endothelial cells, and present in tears and the aqueous humor, adhere to the corneal basement membranes and are maintained in latent inactive states by binding to the latency-associated peptide (LAP) [40, 48]. LAP itself is covalently bound to the fibrillin protein latent TGFβ binding proteins (LTBPs). ECM degradation after anterior corneal injury increases TGFβ production in corneal epithelial cells and in tears from the lacrimal glands [48]. MMPs and other proteases degrade the BMs and release the latent TGFβ complexes at the site of injury. Latent TGFβs are activated by numerous modulators, including matrix metalloproteinases (MMP)-2, -9, -13 and -14, calpains, cathepsins, serine proteases, and members of the ADAMTS (disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs) family, of which there are 19 members, as well as integrins such as αvβ6, thrombospondin-1, fibronectin isoforms, and fibulin-1c [40]. The regulatory processes involved in the release and activation of TGFβ, and other growth factors and cytokines that associate with BMs, such as platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), are highly complex and rather poorly characterized. However, MMPs, their activators and inhibitors, and BMs, contribute critically to this choregraphed function that is a key to the fibrosis process. BM modulation of growth factor localization and function is discussed further later in this review.

Assembly of basement membranes

BMs are produced in the early stages of embryonic development in all animals [49]. Genetic evidence pointed to a hierarchy in BM formation, with self- and co-polymerizing laminins like 511 and 512 acting as a scaffold for the recruitment of the other BM components [50]. Genetic ablation of either the γ1 or β1 chains was found to prevent laminin heterotrimer formation following BM assembly [51, 52].

Originally, it was thought that BMs formed spontaneously in a tissue due to the mere presence of their components in the extracellular space, since laminin and collagen type IV molecules can self-assemble in vitro [33]. The first evidence of self-assembly of BM components in vitro was obtained from studies on collagen type IV [53]. Grant et al. [54] showed that incubation of laminin, collagen type IV and heparin sulfate in vitro yielded BM like structures that were visible using TEM.

Collagen type IV forms polymers under physiological pH and temperature conditions, and lateral association of the molecule results in more complex networks of collagen type IV [55–57]. Oligomerization of collagen type IV begins at the C-terminus with dimer formation. Subsequently, four collagen type IV monomers interact with each other at their N-terminus to form a highly cross-linked network. The C-terminus interaction is stabilized by disulfide bonds that provide high mechanical stability. Similarly, laminin molecules are also capable of self-assembly in vitro in a calcium ion-dependent and concentration-dependent manner [58–60]. As was noted previously, the associations take place at the N-terminal domains of the short arms of laminin molecules [3, 60, 61]. The collagen type IV network and laminin networks are connected by the binding proteins nidogen-1 and nidogen-2, and heparin sulfate proteoglycans perlecan and agrin, which stabilize the network structures [3, 59, 62].

Numerous studies carried out on basement membrane assembly in vivo, however, suggested that the mere presence of BM components is not sufficient to form mature BMs in vivo. Studies on extracellular matrix proteins, cells, and genetically modified animals have revealed mechanisms of basement membrane self-assembly mediated by γ1 subunit-containing laminins—the best characterized being laminins 511, 521, and 3b11 [59]. Yurchenco [59] proposed the following model for BM assembly: (1) A γ1 subunit-containing laminin adheres to a competent cell surface, and polymerizes. (2) This is followed by laminin binding to the extracellular adaptor proteins nidogen-1, nidogen-2, perlecan, and agrin, and to other laminins, such as laminin 332, that cannot co-polymerize but which associate with extracellular matrix. (3) Assembly is completed by the linking of nidogen-1 and nidogen-2, and heparan sulfate proteoglycans perlecan and agrin, to type IV collagen, allowing it to form a secondary stabilizing network. The assembled or reassembled BM provides structural support, anchors the extracellular matrix to the cytoskeleton, and acts as a signaling platform and modulator to both the associated epithelium, endothelium or parenchyma, as well as the underlying stroma, dermis, or other associated extracellular matrix. Heterogeneity of function of BMs in different tissues is created, at least in part, by the myriad isoforms of laminins that vary in their ability to polymerize and to interact with other laminins, as well as integrins, dystroglycan, and other receptors expressed by associated cells. Cell surface receptors and localized proteolysis by matrix metalloproteases are also thought to be important in the BM assembly process [63].

Critical to understanding BM generation during development or regeneration after injury is that they are not produced merely by epithelial, endothelial, or parenchymal cells. In many organs examined to date, BMs are generated through the coordinated efforts of epithelial, endothelial, or parenchymal cells and neighboring fibroblastic cells which cooperate in the production of mature BMs [64–67]. In the cornea, for example, the corneal epithelium must heal for the epithelial BM to regenerate [68], but in organotypic cultures epithelial BM is not regenerated unless fibroblastic cells (corneal fibroblasts, but not myofibroblasts) are also present [69]. The components produced by the fibroblastic cells include but are likely not limited to perlecan, nidogens, collagen type IV, and some laminins [67, 70, 71].

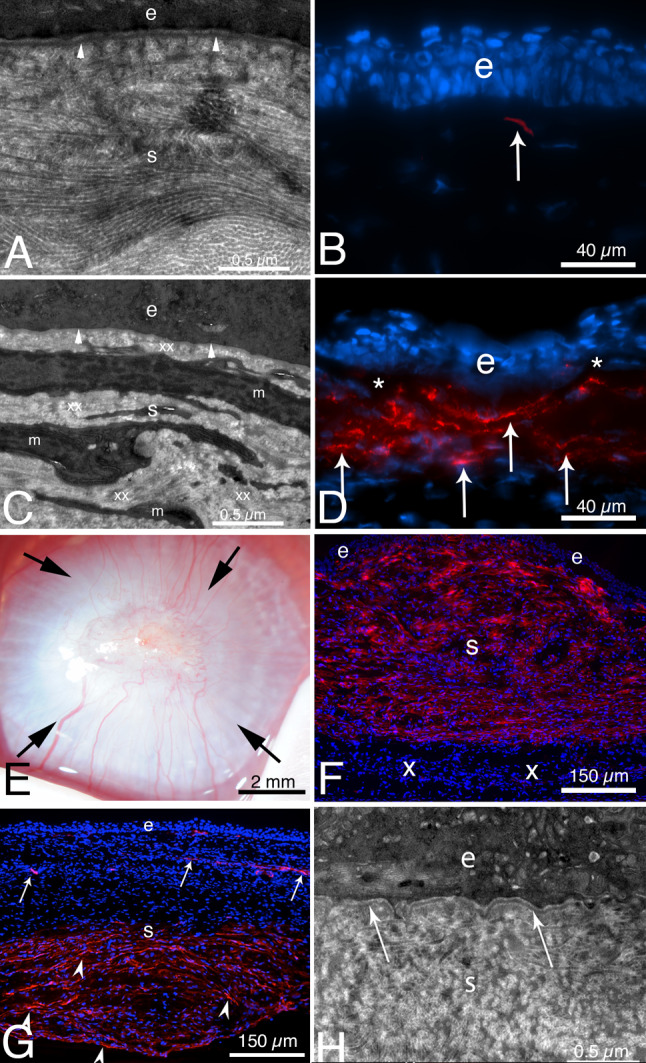

In the cornea (Fig. 4) after anterior injury or infection, defective regeneration of a mature EBM with lamina lucida and lamina densa (detected with TEM) after more severe injuries leads to the development of alpha-smooth muscle actin (SMA)-positive mature myofibroblasts from local keratocyte-derived fibroblasts and bone marrow-derived fibrocyte precursor cells [7–9, 72–74]. These different myofibroblasts all produce large amounts of disordered ECM that includes collagen type I, collagen type III, collagen type VII, and dozens of other matrix proteins [75], although many of these proteins are differentially expressed by the myofibroblasts that develop from different precursor cells [76]. A nascent EBM is formed (Fig. 5) after reproducible more severe injury (-9 diopter) excimer laser ablation photorefractive keratectomies (PRKs) of the stroma in rabbits, but disordered incorporation of some BM components, including perlecan (Figs. 5, 6) [48, 77], leads to defective BM modulation of pro-fibrotic growth factors such as TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 derived from the epithelium and tears that enter into the stroma at high and persistent levels to drive the development of the myofibroblast precursors, and maintain the viability of mature myofibroblasts once they develop (Fig. 7). Corneas that develop fibrosis after injury are also found to have high levels of collagen type IV in the nascent EBM, but also in the underlying anterior stroma (compare Fig. 5A, B) [39]. Currently, it remains unknown whether the collagen type IV that is localized to the stroma apart from the EBM [39], and also the DBM [78], after corneal injury is full-length molecules or, alternatively, functional fragments of collagen type IV [79] that retain the antigenic sites recognized by the detecting antibody.

Fig. 4.

TEM and alpha-smooth muscle actin (SMA) IHC after severe epithelial-stromal injury or Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis in rabbits. A From Torricelli et al. [72], at 1 month after reproducible moderate epithelial–stromal corneal injury (-4.5D photorefractive keratectomy [PRK] laser surgery) the epithelial BM has regenerated beneath the epithelium (e) with normal lamina lucida and lamina densa (arrowheads). Notice in the normal transparent stroma (s), the collagen fibrils are seen both tangentially and longitudinally in different areas and are regular in diameter and packing. B. IHC for SMA at 1 mo. after -4.5D PRK [80] revealed only a single myofibroblast (arrow) in the anterior stroma. C. At 1 month after severe epithelial–stromal corneal injury (-9D PRK surgery) [80], the cornea had dense scarring fibrosis (not shown) and TEM showed no discernable lamina lucida and lamina densa (arrowheads) beneath the epithelium (e). The anterior stroma (s) was packed with layers of myofibroblasts (m) and the surrounding stromal matrix (xx) produced by the myofibroblasts is disorganized with no regular packing of collagen fibrils. The myofibroblasts are themselves opaque [125]—as is the disordered stromal matrix they produce. D IHC for SMA at 1 month after severe injury (−9D PRK surgery) [80] showed large numbers of layered myofibroblasts (arrows) in the anterior stroma beneath the epithelium (e). * indicates artifactual dissociation of the epithelium from the anterior stroma that frequently occurs in corneas without a mature EBM. E From Marino et al. [7], at 1 month after severe Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection treated with tobramycin, the cornea has dense opacity from fibrosis (arrows) despite full healing of the epithelium. F IHC for SMA (red) reveals myofibroblasts filling the anterior 90% of the stroma (s) beneath the intact epithelium (e) [7]. In this cornea the infection was halted prior to destruction of DBM and the endothelium (not shown), and the posterior stroma (x) is hypercellular but doesn’t contain myofibroblasts. The epithelial BM in this cornea did not have lamina lucida and lamina densa (not shown). G At 2 months after severe Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection [7], most myofibroblasts have disappeared in the anterior half of the stroma beneath the epithelium (e) in this cornea. SMA + pericytes can be seen associated with neovascularization (arrows). Myofibroblasts (arrowheads) are present in the posterior half of the stroma of this cornea since the original infection destroyed DBM, and, therefore, TGFβ1 continuously enters the stroma from the aqueous humor to maintain myofibroblast viability in the posterior stroma [82, 83]. H TEM of the cornea in G at two months after Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis [7] showed that the epithelial BM has regenerated beneath the epithelium (e) with normal lamina lucida and lamina densa (arrows). A–D reprinted with permission from Torricelli et al. [72]. E–H reprinted with permission from Marino et al. [7]

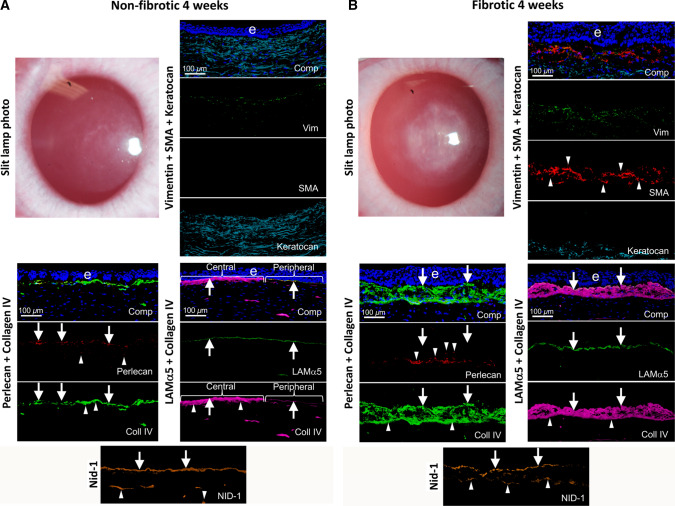

Fig. 5.

Non-fibrotic and fibrotic healing in corneas. Slit lamp photographs and IHC for cell markers vimentin (mesenchymal cells), SMA (myofibroblasts) and keratocan (keratocytes), as well as BM components laminin alpha-5, laminin beta-3, perlecan, nidogen-1, and collagen type IV at 4 weeks after PRK. A A cornea that did not develop scarring fibrosis after PRK laser surgery. Not mild “haze” attributable to corneal fibroblasts, but no myofibroblasts were present. Arrows indicate BM components incorporated into the EBM. Arrowheads indicate components detected in anterior stromal cells. B A cornea with scarring fibrosis at four weeks after PRK surgery had severe opacity corresponding to the area of laser ablation and multilayered SMA + myofibroblasts (arrowheads) in the anterior stroma. All fibrotic corneas had collagen type IV, laminin alpha-5, and nidogen-1 in the EBM (arrows) beneath the epithelium (e). Collagen type IV was present at higher levels both in the nascent EBM and underlying anterior stroma in fibrotic corneas compared to non-fibrotic corneas after PRK surgery (compare A and B) [39]. Perlecan, however, was absent from the “moth-eaten” EBM of these corneas (arrows). Anterior stromal myofibroblasts and extracellular vesicle-like structures contained perlecan (arrowheads), but it was not incorporated into the nascent EBM (see Fig. 6). Collagen type IV (arrowheads) and nidogen-1 (arrowheads) were present within and around anterior myofibroblasts of the fibrotic corneas at four weeks post-PRK. Comp is a composite of all components for each IHC and DAPI-stained nuclei of all cells (blue). Reprinted with permission from de Oliveira et al. [39]

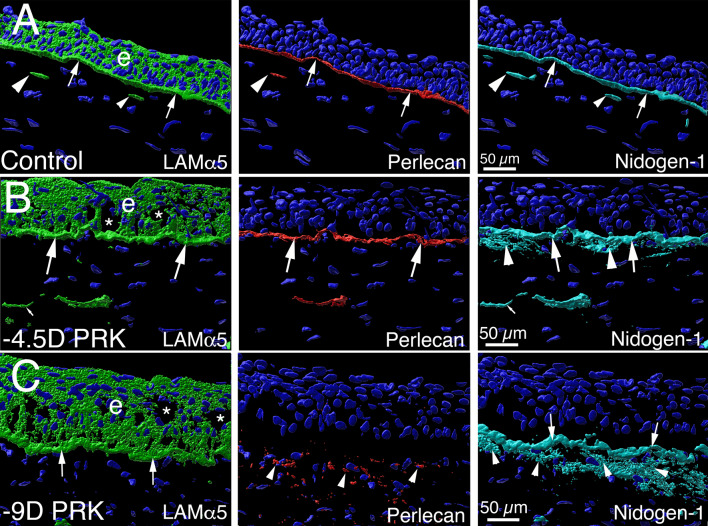

Fig. 6.

Defective perlecan incorporation into the EBM of injured corneas that develop scarring stromal fibrosis. Imaris 3D constructions of confocal microscopy images of triplex laminin alpha-5, perlecan and nidogen-1 IHC in the unwounded control corneas and corneas with moderate and severe epithelial-stromal injury from de Oliveira et al. [48]. A In an unwounded cornea, laminin alpha-5 (green) is detected in the epithelium (e), and in the EBM (arrows). Two DAPI-negative vesicles with laminin alpha-5 (arrowheads) are present in the subepithelial stroma adjacent to the EBM and likely were produced by keratocytes to contribute to maintenance of the EBM. Perlecan (red) is detected in the EBM (arrows), and also in vesicles in the anterior stroma (arrowhead). Nidogen-1 (blue gray) is a major component in the EBM (arrows) and is present in secretory vesicles in the subepithelial stroma (arrowheads). B In a cornea that had moderate epithelial-stromal injury (-4.5D excimer laser photorefractive keratectomy [PRK]) at one month after surgery that did not develop myofibroblasts or scarring stromal fibrosis (see Fig. 5A), the findings for laminin alpha-5, perlecan and nidogen-1 localization in the EBM were similar to the unwounded cornea (large arrows), except increased nidogen-1 (arrowheads) was present in the subepithelial stroma surrounding stromal keratocyte/corneal fibroblast cells. DAPI-negative vesicles (small arrows) in the anterior stroma contained one or more of the EBM components. C In a cornea that had more severe epithelial-stromal injury (-9D PRK), at 1 month after surgery there was greater stromal opacity and myofibroblasts (see Fig. 5B). Laminin alpha-5 and nidogen-1 (arrows) localization in the EBM was similar to that in the unwounded control cornea. Perlecan, however, was not detected in the EBM, even though it was present in the anterior stroma within and surrounding myofibroblasts (see Fig. 4D). Stromal nidogen-1 (arrowheads) was also present at high levels in the anterior stroma surrounding myofibroblasts. Blue is DAPI-stained nuclei in all panels. e is epithelium. * indicates artifactual defects in the epithelium which are often seen in PRK corneas that are cryo-sectioned in the first one–two months after surgery. Reprinted with permission from de Oliveira et al. [48]

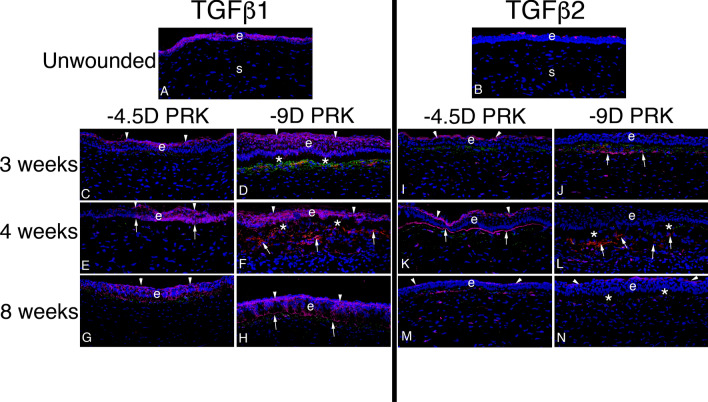

Fig. 7.

TGF beta-1 and TGF beta-2 localization in rabbit corneas with moderate injuries without stromal fibrosis and severe injuries with stromal fibrosis. Representative images are shown from a study in rabbits from de Oliveira et al. [48]. A In the unwounded epithelium (e), TGFβ1 (pink) was present in epithelial cells with higher localization in apical epithelium. Little TGFβ1 was present in stromal (s) cells where keratocytes predominate in unwounded corneas. B In the unwounded epithelium (e), TGFβ2 (pink) was restricted to the apical epithelial surface (from tears) with little production in epithelial cells themselves. Little, if any, TGFβ2 was present in stromal (s) cells. At time points from immediate wounded to 2 weeks (not shown, [see 48]), TGFβ1 was produced by epithelial cells and delivered from tears, while TGFβ2 was delivered in large amounts from tears. Some stromal cells also produced TGFβ1 and TGFβ2. All corneas C to N had triplex IHC for TGFβ1 or TGFβ2 (pink), vimentin (green), and the alpha-smooth muscle actin (SMA) marker for myofibroblasts (red). C At three weeks after moderate injury -4.5D PRK, apical localization (arrowheads) of TGFβ1 was already prominent and although there were some vimentin + cells (corneal fibroblasts, fibrocytes and their progeny) in the subepithelial stroma, there were no SMA + myofibroblasts in the stroma. D Conversely, at 3 weeks after severe injury -9D PRK, lower TGFβ1 localization to apical epithelium (arrowheads) was noted, and TGFβ1 was prominent throughout the epithelium and into the superficial stroma. Many vimentin + (green) cells were present in the subepithelial stroma (some of which had associated TGFβ1) and some of these myofibroblast precursor cells had become mature SMA + myofibroblasts (red). E At four weeks after moderate injury -4.5D PRK, apical localization of TGFβ1 (arrowheads) continued to be prominent and EBM TGFβ1 localization (arrows) was also noted. A few stromal cells, both vimentin + and vimentin− had TGFβ1 associated with them. There were no SMA + myofibroblasts in the stroma. F Conversely, in the four week -9D PRK corneas, TGFβ1 was prominent throughout the epithelium, with apical prominence (arrowheads), but without EBM localization. Many SMA + myofibroblasts (arrows) occupied the subepithelial stroma. Two four-month -4.5 D PRK corneas in this series (not shown) had an intermediate pattern of TGFβ1 localization [48] with little apical epithelial or EBM localization, and some SMA + myofibroblast development in the subepithelial stroma. G and H. At eight weeks after −4.5D or −9D PRK, respectively, apical epithelial (arrowheads) and EBM (arrows in H) TGFβ1 was prominent. SMA + myofibroblasts were no longer present in the subepithelial stroma (after likely undergoing apoptosis). I At three weeks after −4.5D PRK, there was prominent TGFβ2 in the apical epithelium (arrowheads). There were many vimentin + cells in the anterior stroma, but none were SMA + myofibroblasts. In the deeper stroma, some vimentin + and vimentin- cells had TGFβ2 associated with them. J At three weeks after −9D PRK, there was little apical epithelial localization of TGFβ2. Some vimentin + cells in the subepithelial stroma had developed into SMA + (red) myofibroblasts. A band of TGFβ2 (arrows) was localized posterior to the vimentin + cells in the stroma. K At four weeks after −4.5D PRK, apical epithelial (arrowheads) and EBM (arrows) TGFβ2 localization was prominent. No vimentin + cells in the subepithelial stroma had developed into SMA + myofibroblasts in the cornea shown. L At four weeks after –9D PRK, little epithelial TGFβ2 localization was detected. Note this does not necessarily indicate that TGFβ2 from tears was not passing through the epithelium, but that the lack of barrier in the apical epithelium or EBM did not produce an increase in TGFβ2 concentration to a detectible level. The subepithelial stroma had large numbers of SMA + myofibroblasts (arrows). In the deeper stroma, there are both vimentin + and vimentin− cells with associated TGFβ2. M, N At eight weeks after −4.5D or −9D PRK, respectively, apical epithelial TGFβ2 localization was prominent. No SMA + myofibroblasts remained in the subepithelial stroma in all corneas from both groups. Some subepithelial cells continued to have associated TGFβ2 in both groups. e is epithelium in all panels. Blue is DAPI-stained nuclei in all panels. *indicates epithelial dislocation from stroma during cryo-sectioning. Reprinted with permission from de Oliveira et al. [48]

There are several known factors that underlie defective regeneration of the EBM in the cornea, and the subsequent development of myofibroblasts and fibrosis, after anterior corneal injury. First, any epithelial defect must close within two to three weeks or scarring stromal fibrosis will invariably develop [68]. Thus, intact epithelium is an absolute requirement for EBM regeneration because the epithelium is the primary source of laminins that initiate EBM regeneration [59]. However, healing of the epithelium does not ensure regeneration of a mature EBM, and, in fact, the epithelium heals normally in most corneas that develop scarring fibrosis after PRK [8]. Another factor associated with defective EBM regeneration is stromal surface irregularity (often produced by microbial infections, trauma or some surgeries) that mechanically impedes regeneration of a continuous, mature EBM [80]. But corneas where the epithelium heals and the stromal surface is smooth may still have defective EBM regeneration and develop persistent myofibroblasts and fibrosis [72, 73]. Corneal fibroblastic cells (keratocytes and corneal fibroblasts) produce EBM components such as laminins, perlecan, nidogens, and collagen type IV [39, 48, 70, 71, 77], and cooperate with the epithelium in regeneration of the EBM [70, 77]. Depending on the type and severity of corneal injury, numerous anterior stromal keratocytes and corneal fibroblasts die by apoptosis and necrosis after microbial infection, trauma or surgery [81, 82]. A deficiency of keratocytes and corneal fibroblasts in proximity to the basal epithelium that contribute components to the nascent EBM, possibly via secretory vesicles (Fig. 6), is likely an important factor leading to defective EBM regeneration in corneas [7, 8, 83]. There are likely additional factors underling defective EBM regeneration in the cornea and other organs that have yet to be identified.

The corneal stromal fibrosis process associated with injuries, infections, or surgical complications of DBM and the corneal endothelium in the posterior cornea is similar to that in the anterior cornea, except TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 enter the posterior stroma from the aqueous humor and residual corneal endothelial cells [78, 84]. When DBM, which has perlecan and collagen type IV as major components, is injured or removed, TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 penetrate into the posterior stroma and drive the development of myofibroblasts from resident keratocytes/corneal fibroblasts and bone marrow-derived fibrocytes [78, 84]. The posterior corneal myofibroblasts (Fig. 4G), and the disordered extracellular matrix they produce, persist in the posterior stroma until the DBM is regenerated by the coordinated efforts of healed corneal endothelium and keratocytes/corneal fibroblasts [78]. Regeneration of the DBM cuts off the penetration of TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 requisite for myofibroblast persistence, resulting in apoptosis of the myofibroblasts. Keratocytes/corneal fibroblasts subsequently reabsorb and reorganize the disordered extracellular matrix produced by the myofibroblasts and can restore corneal transparency [78]. The corneal endothelium, especially in humans, however, has less proliferative potential than the corneal epithelium and the regeneration of DBM, therefore, tends to be slower [78]. Corneal endothelial transplantation surgery may facilitate the resolution of corneal fibrosis due to posterior corneal injuries.

More research into the role of injury and defective regeneration of BMs in fibrosis noted in other organs, such as the lung (idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, IPF), skin (hypertrophic scars in scleroderma), kidney (renal fibrosis) and heart (fibrosis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and following myocardial infarction), should focus on BM modulation of the localization and activity of pro-fibrotic growth factors such as TGFβ [83]. Defective BM regeneration has also been noted in Drosophila melanogaster larval epidermis with scar-like lesions and could provide an excellent model to study these associations [85]. Thus, injury and defective BM regeneration may underlie fibrotic disorders and diseases in the organs of all animals.

Laminin network interactions with cell surface receptors

Laminins are secreted heterotrimeric proteins composed of α, β and γ subunits that bind to receptors and lipids at the cell surface. The long arm of the laminin molecules interacts with integrins (prominently α3β1, α6β1, α7β1, and α6β4 and dystroglycan via five LG domains at the c-terminus [59]. Perlecan may also provide a bridge between the laminin network and the cell surface. A network of cross-linked collagen type IV is laid parallel to the laminin network in the regenerated BM [59].

Cell surface receptor integrins bind to the LG1-3 regions of laminin [86–89], while dystroglycan, heparin sulfate and sulphated glycolipids bind to the LG4–5 region [90–92]. Integrins are transmembrane proteins that mediate adhesion of cells to the extracellular matrix. Integrins also interact with intracellular signaling proteins, like RAS/ERK, through their intracellular domains. The importance of integrins in BM assembly was confirmed in mice that lacked the α3 integrin subunit and had aberrant and disorganized BMs [93, 94]. Also, a deficiency of β1 integrins in teratoma interferes with BM assembly [95]. Brakebusch and coworkers [96] deleted the β1 integrin gene in the basal cells of the epidermis and found it produced defects in the BM at the interfollicular dermal–epidermal junction. Thus, integrins likely play a critical organizational role in the process of BM formation during development or regeneration after injury, and this function appears to be predominantly one of β1-integrins since disruption or mutation of integrin α6β4 did not produce obvious BM damage [97, 98].

Dystroglycan, a widely expressed laminin receptor, is composed of two subunits (α and β) and is activated by proteolytic cleavage [99]. The highly glycosylated α subunit binds to extracellular matrix components and the transmembrane β subunit bridges dystroglycan to the cell cytoskeleton. Dystroglycan knockout mice die during the early embryonic period with a ruptured Reichert’s membrane [100]. Studies suggested that dystroglycan is an important organizer of laminin molecules at the cell surface [101, 102]. Experiments with anti-sense dystroglycan transfection found that myoblasts subsequently did not accumulate laminin at their surfaces [103].

Thus, the binding of BM components to cell surface receptors is required to form and stabilize BMs. The importance of cell surface receptors in BM formation and stability in vivo was supported by studies that demonstrated the concentration dependence of laminin and collagen type IV self-assembly in vitro [2, 60, 104].

Laminin 332, which has only one LN domain, cannot self-polymerize or co-polymerize with other laminins, but associates with BMs (see Fig. 3). Laminin 332 is essential for epithelial-dermal adhesion [105, 106] and likely interacts with other laminins and other basement membrane components—especially in organs such as the cornea or skin where BMs have strong attachments to hemidesmosomes [15].

Maturation and stabilization of basement membranes

The collagen type IV knockout is lethal in mice between E10 and E11—due to a disruption of Reichert’s membrane—but tissues containing collagen type IV-deficient BMs appear normal prior to death [107]. Those authors considered incorporation of the collagen type IV network into BMs to be a maturation step that provides increased BM structural stability.

In addition to the direct laminin receptor interactions, there are many indirect linkages that bind laminins to cell surfaces. One such connection is provided by agrin, a heparin sulfate proteoglycan (HSPG) that is present in many BMs, especially in the neuromuscular junction [108]. Perlecan, the major HSPG of most BMs, can also provide a bridge between laminins and cell surfaces.

Nidogen-1 and nidogen-2 are important linker glycoproteins that bind the laminin γ1 chain in laminin networks, and also bind collagen type IV in that network, in addition to perlecan [109–112]. Studies showed that heparin sulfate complements this nidogen function in skin epidermal BM [113].

BM modulation of growth factor localization and function

The EBM in the cornea is important for epithelial adhesion to the underlying stroma and is involved in the proliferation and differentiation of the epithelium during homeostasis, as well as the epithelial healing response to injury [114]. DBM serves similar functions for the corneal endothelium [84]. Both of these BMs are important in separating their associated epithelial or endothelial tissues from the adjacent stroma and thereby maintaining the normal morphology and function of the cornea.

Severe injury and defective regeneration of the EBM [7, 8, 39, 48, 72, 73] (Fig. 7) or injury to DBM [82, 83] leads to the development of stromal myofibroblasts from both keratocyte- and bone marrow-derived precursor cells. The lack of either mature corneal BM leads to penetration of TGFβ1, TGFβ2, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and possibly other modulators, to sustained levels necessary to drive the development and persistence of mature myofibroblasts and maintain the fibrosis they produce until the BMs are regenerated or replaced surgically [4]. In normal unwounded corneas (Fig. 7), these pro-fibrotic growth factors are present in large amounts in the epithelium, tears and aqueous humor and are inhibited from entering the stroma by these BMs [39, 48]. Specific components of the BMs bind pro-fibrotic growth factors and prevent their passage into the stroma—including perlecan (binds PDGF AA, and PDGF BB), collagen type IV (binds TGFβ1 and TGFβ2) [115], and nidogen-1/2 (binds PDGF AA and PDGF BB) [96–99]. Perlecan also produces a high negative charge due to its three heparan sulfate side chains [40, 116–118], and, therefore, provides a non-specific barrier to TGFβ penetration through either the EBM or DBM into the corneal stroma. Other components of BMs, such as collagen type XVIII, which is a heparin sulfate side chain-containing proteoglycan, likely also modulate the localization and possibly activation of heparin-binding growth factors [119, 120]. Thus, it is the molecular composition of the BMs, and the structure and function of their components, that have critical roles in modulating normal corneal homeostasis and the cellular responses to injuries when they occur. It follows that the intact and mature corneal BMs are essential for maintaining homeostatic stromal keratocyte (the normally quiescent fibroblastic cells of the unwounded corneal stroma) differentiation and function.

Importantly, this growth factor modulatory function of the EBM in the cornea is bidirectional. Thus, components of the EBM also bind the heparin-binding growth factors hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and keratinocyte growth factor (KGF, also termed FGF-7) that are produced by keratocytes, and at higher levels after injury by corneal fibroblasts, to modulate the proliferation, motility, differentiation, and apoptosis of the overlying epithelial cells [121, 122]. Once HGF passes through the EBM and binds its cognate receptor expressed on corneal epithelial cells, signals are transmitted from the receptor to the MAPK cascade via the receptor-Grb2/Sos complex to the Ras pathway and via protein kinase C [123], that ultimately stimulate the motility and proliferation of the epithelial cells. In addition to inhibiting terminal differentiation [123], HGF receptor activation protects the corneal epithelial cells from apoptosis via a PI-3K/Akt/Bad pathway [124]. KGF, after passage through the EBM, activates many of these same signaling pathways [123, 124], but KGF also was shown to inhibit p53, retinoblastoma, caspases, and p27(kip) functions in apoptosis, as well as cell cycle arrest, and thereby promote the expression of cell cycle progressing molecules for longer duration [125]. The combined effect of signaling by HGF and KGF that is sustained when EBM structure and function is defective is to trigger epithelial hyperplasia and hypertrophy that are often noted after injuries such as PRK surgery (see Fig. 5B). Thus, regeneration of normal BMs structure and function is critical for restoration of normal epithelial and stromal tissue morphology in the cornea after injury. This same principal is likely true in other organs such as skin, lungs, and kidneys.

Conclusions

BMs are highly organized extracellular matrices that serve as adhesive structures for associated epithelial, endothelial and parenchymal cells, but also have critical roles in the development and maintenance of organ structure. They are signaling platforms that modulate the motility, proliferation and differentiation of attached cells through integrin and other receptor interactions. Their components are critical modulators of the localization and activity of growth factors, including TGFβ1, TGFβ2, PDGF, HGF and KGF, that thereby orchestrate responses to injuries.

Author contributions

SEW conceived of and wrote this review article.

Funding

VR180066 (SEW) from the Department of Defense, EY025585 from the National Eye Institute, and Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, NY.

Availability of data and materials

NA.

Code availability

NA.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The author does not have any commercial or proprietary interests in the subject matter of this review article.

Ethics approval

All animal experiments described in this review had Cleveland Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and/or U.S Army Animal Care and Use Committee approval. All human studies had Investigational Review Board approval.

Consent to participate

NA.

Consent for publication

NA.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sasaki T, Fässler R, Hohenester E. Laminin: the crux of basement membrane assembly. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:959–963. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200401058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yurchenco PD, O’Rear J. Supramolecular organization of basement membranes. In: Rohrbach DH, Timpl R, editors. Molecular and cellular aspects of basement membranes. San Diego: Academic Press; 1993. pp. 20–47. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hohenester E, Yurchenco PD. Laminins in basement membrane assembly. Cell Adh Migr. 2013;7:56–63. doi: 10.4161/cam.21831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson SE. Coordinated modulation of corneal scarring by the epithelial basement membrane and Descemet's basement membrane. J Refract Surg. 2019;35:506–516. doi: 10.3928/1081597X-20190625-02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martinez-Hernandez A, Amenta PS. The basement membrane in pathology. Lab Invest. 1983;48:656–677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miosge N. The ultrastructural composition of basement membranes in vivo. Histol Histopathol. 2001;16:1239–1248. doi: 10.14670/HH-16.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marino GK, Santhiago MR, Santhanam A, Lassance L, Thangavadivel S, Medeiros CS, Bose K, Tam KP, Wilson SE. Epithelial basement membrane injury and regeneration modulates corneal fibrosis after pseudomonas corneal ulcers in rabbits. Exp Eye Res. 2017;161:101–105. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marino GK, Santhiago MR, Santhanam A, Lassance L, Thangavadivel S, Medeiros CS, Torricelli AAM, Wilson SE. Regeneration of defective epithelial basement membrane and restoration of corneal transparency. J Ref Surg. 2017;33:337–346. doi: 10.3928/1081597X-20170126-02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saikia P, Medeiros CS, Thangavadivel S, Wilson SE. Basement membranes in the cornea and other organs that commonly develop fibrosis. Cell Tissue Res. 2018;374:439–453. doi: 10.1007/s00441-018-2934-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schymeinsky J, Nedbal S, Miosge N, Pöschl E, Rao C, Beier DR, Skarnes WC, Timpl R, Bader BL. Gene structure and functional analysis of the mouse nidogen-2 gene: nidogen-2 is not essential for basement membrane formation in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:6820–6830. doi: 10.1128/mcb.22.19.6820-6830.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Engel J. Structure and function of laminin. In: Rohrbach DH, editor. Molecular and cellular aspects of basement membranes. San Diego: Academic Press; 1993. pp. 147–176. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aumailley M, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Carter WG, Deutzmann R, Edgar D, Ekblom P, Engel J, Engvall E, Hohenester E, Jones JC, Kleinman HK, Marinkovich MP, Martin GR, Mayer U, Meneguzzi G, Miner JH, Miyazaki K, Patarroyo M, Paulsson M, Quaranta V, Sanes JR, Sasaki T, Sekiguchi K, Sorokin LM, Talts JF, Tryggvason K, Uitto J, Virtanen I, von der Mark K, Wewer UM, Yamada Y, Yurchenco PD. A simplified laminin nomenclature. Matrix Biol. 2005;24:326–332. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen MW, Jacobson C, Yurchenco PD, Morris GE, Carbonetto S. Laminin-induced clustering of dystroglycan on embryonic muscle cells: comparison with agrin-induced clustering. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:1047–1058. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.5.1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colognato H, Yurchenco PD. The laminin α2 expressed by dystrophic dy2j mice is defective in its ability to form polymers. Curr Biol. 1999;9:1327–1330. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)80056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Champliaud MF, Lunstrum GP, Rousselle P, Nishiyama T, Keene DR, Burgeson RE. Human amnion contains a novel laminin variant, laminin 7, which like laminin 6, covalently associates with laminin 5 to promote stable epithelial-stromal attachment. J Cell Biol. 1996;132:1189–1198. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.6.1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walko G, Castañón MJ, Wiche G. Molecular architecture and function of the hemidesmosome. Cell Tissue Res. 2015;360:529–544. doi: 10.1007/s00441-014-2061-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mayer U, Timpl R. Nidogen, a versatile binding protein of basement membranes. In: Yurchenco PD, Birk DE, Mecham RP, editors. Extracellular Matrix Assembly and Structure. San Diego: Academic Press; 1994. pp. 389–416. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kohfeld E, Sasaki T, Gohring W, Timpl R. Nidogen-2: a new basement membrane protein with diverse binding properties. J Mol Biol. 1998;282:99–109. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mann K, Deutzmann R, Aumailley M, Timpl R, Raimondi L, Yamada Y, Pan T-C, Conway D, Chu ML. Amino acid sequence of mouse nidogen, a multidomain basement membrane protein with binding activity for laminin, collagen IV and cells. EMBO J. 1989;8:65–72. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03349.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murshed M, Smyth N, Miosge N, Karolat T, Krieg M, Paulsson M, Nischt R. The absence of nidogen 1 does not affect murine basement membrane formation. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:7007–7012. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.18.7007-7012.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shibuya H, Okamoto O, Fujiwara S. The bioactivity of transforming growth factor-beta1 can be regulated via binding to dermal collagens in mink lung epithelial cells. J Dermatol Sci. 2006;41:187–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bader BL, Smyth N, Nedbal S, Miosge N, Baranowsky A, Mokkapati S, Murshed M, Nischt R. Compound genetic ablation of nidogen 1 and 2 causes basement membrane defects and perinatal lethality in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:6846–6856. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.15.6846-6856.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Timpl R. Proteoglycans of basement membranes. EXS. 1994;70:123–144. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-7545-5_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iozzo RV. Basement membrane proteoglycans: from cellar to ceiling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:646–656. doi: 10.1038/nrm1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Groffen AJ, Ruegg MA, Dijkman H, van de Velden TJ, Buskens CA, van den Born J, Assmann KJ, Monnens LA, Veerkamp JH, van den Heuvel LP. Agrin is a major heparan sulfate proteoglycan in the human glomerular basement membrane. J Histochem Cytochem. 1998;46:19–27. doi: 10.1177/002215549804600104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Costell M, Gustafsson E, Aszódi A, Mörgelin M, Bloch W, Hunziker E, Addicks K, Timpl R, Fässler R. Perlecan maintains the integrity of cartilage and some basement membranes. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:1109–1122. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.5.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hassel JR, Gehron Robey P, Barrach HJ, Wilczeck J, Rennard SI, Martin GR. Isolation of heparan sulfate-containing proteoglycan from basement membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:4494–4498. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.8.4494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noonan D, Hassel JR. Proteoglycans of basement membranes. In: Rohrback DH, editor. Molecular and cellular aspects of basement membranes. San Diego: Academic Press; 1993. pp. 189–210. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Denzer AJ, Gesemann M, Schumacher B, Ruegg MA. An amino-terminal extension is required for the secretion of chick agrin and its binding to extracellular matrix. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:1547–1560. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.6.1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hudson BG, Reeders ST, Tryggvason K. Type IV collagen: structure, gene organization and role in human diseases. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:26033–26036. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)74270-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khoshnoodi J, Pedchenko V, Hudson BG. Mammalian collagen IV. Microsc Res Tech. 2008;71:357–370. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ljubimov AV, Burgeson RE, Butkowski RJ, Michael AF, Sun TT, Kenney MC. Human corneal basement membrane heterogeneity: topographical differences in the expression of type IV collagen and laminin isoforms. Lab Invest. 1995;72:461–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quondamatteo F. Assembly, stability and integrity of basement membrane in vivo. Histochem J. 2002;34:369–381. doi: 10.1023/a:1023675619251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gatseva A, Sin YY, Brezzo G, Van Agtmael T. Basement membrane collagens and disease mechanisms. Essays Biochem. 2019;63:297–312. doi: 10.1042/EBC20180071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Calvo AC, Moreno L, Moreno L, Toivonen JM, Manzano R, Molina N, de la Torre M, López T, Miana-Mena FJ, Muñoz MJ, Zaragoza P, Larrodé P, García-Redondo A, Osta R. Type XIX collagen: a promising biomarker from the basement membranes. Neural Regen Res. 2020;15:988–995. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.270299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kato T, Chang JH, Azar DT. Expression of type XVIII collagen during healing of corneal incisions and keratectomy wounds. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:78–85. doi: 10.1167/iovs.01-1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cotrufo M, De Santo L, Della Corte A, Di Meglio F, Guerra G, Quarto C, Vitale S, Castaldo C, Montagnani S. Basal lamina structural alterations in human asymmetric aneurismatic aorta. Eur J Histochem. 2005;49:363–370. doi: 10.4081/964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Löffek S, Schilling O, Franzke CW. Series "matrix metalloproteinases in lung health and disease": Biological role of matrix metalloproteinases: a critical balance. Eur Respir J. 2011;38:191–208. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00146510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Oliveira RC, Sampaio LP, Shiju TM, Santhiago MR, Wilson SE. Epithelial basement membrane regeneration after PRK-induced epithelial-stromal injury in rabbits: fibrotic vs. non-fibrotic corneal healing. J Ref Surg. 2022;38:50–60. doi: 10.3928/1081597X-20211007-02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilson SE. TGF beta -1, -2 and -3 in the modulation of fibrosis in the cornea and other organs. Exp Eye Res. 2021;207:108594. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2021.108594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Visse R, Nagase H. Matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases: structure, function, and biochemistry. Circ Res. 2003;92:827–839. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000070112.80711.3D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakayama K. Furin: a mammalian subtilisin/Kex2p-like endoprotease involved in processing of a wide variety of precursor proteins. Biochem J. 1997;327(Pt 3):625–635. doi: 10.1042/bj3270625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caley MP, Martins VL, O'Toole EA. Metalloproteinases and wound healing. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2015;4:225–234. doi: 10.1089/wound.2014.0581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sivak JM, Fini ME. MMPs in the eye: emerging roles for matrix metalloproteinases in ocular physiology. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2002;21:1–14. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(01)00015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Geanon JD, Tripathi BJ, Tripathi RC, Barlow GH. Tissue plasminogen activator in avascular tissues of the eye: a quantitative study of its activity in the cornea, lens, and aqueous and vitreous humors of dog, calf, and monkey. Exp Eye Res. 1987;44:55–63. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(87)80025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sugioka K, Mishima H, Kodama A, Itahashi M, Fukuda M, Shimomura Y. Regulatory mechanism of collagen degradation by keratocytes and corneal inflammation: the role of urokinase-type plasminogen activator. Cornea. 2016;35(Suppl 1):S59–S64. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tervo T, Tervo K, van Setten GB, Virtanen I, Tarkkanen A. Plasminogen activator and its inhibitor in the experimental corneal wound. Exp Eye Res. 1989;48:445–449. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(89)80012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Oliveira RC, Tye G, Sampaio LP, Shiju TM, Dedreu J, Menko AS, Santhiago MR, Wilson SE. TGFβ1 and TGFβ2 proteins in corneas with and without stromal fibrosis: delayed regeneration of epithelial barrier function and the epithelial basement membrane in corneas with stromal fibrosis. Exp Eye Res. 2021;202:108325. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2020.108325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schittny JC, Yurchenco PD. Basement membranes: molecular organization and function in development and disease. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1989;1:983–988. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(89)90069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li S, Edgar D, Fässler R, Wadsworth W, Yurchenco PD. The role of laminin in embryonic cell polarization and tissue organization. Dev Cell. 2003;4:613–624. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00128-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miner JH, Li C, Mudd JL, Go G, Sutherland AE. Compositional and structural requirements for laminin and basement membranes during mouse embryo implantation and gastrulation. Development. 2004;131:2247–2256. doi: 10.1242/dev.01112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smyth N, Vatansever HS, Murray P, Meyer M, Frie C, Paulsson M, Edgar D. Absence of basement membranes after targeting the LAMC1 gene results in embryonic lethality due to failure of endoderm differentiation. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:151–160. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.1.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yurchenco PD, Furthmayr H. Self-assembly of basement membrane collagen. Biochemistry. 1984;23:1839–1850. doi: 10.1021/bi00303a040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grant DS, Leblond CP, Kleinmann HK, Inoue S, Hassell J. The incubation of laminin, collagen IV and heparan sulfate proteoglycan at 35◦C yields basement membrane-like structures. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:1567–1574. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.4.1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yurchenco PD, Ruben GC. Basement membrane structure in situ: evidence for lateral associations in the type IV collagen network. J Cell Biol. 1987;105:2559–2568. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.6.2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yurchenco PD, Schittny JC. Molecular architecture of basement membranes. FASEB J. 1990;4:1577–1590. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.4.6.2180767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yurchenco PD, O'Rear JJ. Basal lamina assembly. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1994;6:674–681. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Paulsson M. The role of Ca2+ binding in the self-aggregation of laminin-nidogen complexes. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:5425–5430. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)60734-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yurchenco PD. Integrating activities of laminins that drive basement membrane assembly and function. Curr Top Membr. 2015;76:1–30. doi: 10.1016/bs.ctm.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yurchenco PD, Tsilibary EC, Charonis AS, Furthmayr H. Laminin polymerization in vitro. Evidence for a two-step assembly with domain specificity. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:7636–7644. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(17)39656-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yurchenco PD, Cheng YS, Colognato H. Laminin forms an independent network in basement membranes. J Cell Biol. 1992;117:1119–1133. doi: 10.1083/jcb.117.5.1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dziadek M. Role of laminin-nidogen complexes in basementmembrane formation during embryonic development. Experientia. 1995;51:901–913. doi: 10.1007/BF01921740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Timpl R, Brown JC. Supramolecular assembly of basement membranes. BioEssays. 1996;18:123–32. doi: 10.1002/bies.950180208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Marnkovich MP, Keene DR, Rimberg CS, Burgeson RE. Cellular origin of the dermal-epidermal basement membrane. Dev Dyn. 1993;197:255–267. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001970404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Breitkreutz D, Mirancea M, Schmidt C, Beck R, Werner U, Stark H-J, Gerl M, Fusenig NE. Inhibition of basement membrane formation by a nidogen-binding laminin gamma1-chain fragment in human skin-organotypic co-cultures. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:2611–2622. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Simon-Assmann P, Bouziges F, Arnold C, Haffen K, Kedinger M. Epithelial-mesenchymal interactions in the production of basement membrane components in the gut. Development. 1988;102:339–347. doi: 10.1242/dev.102.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Torricelli AAM, Marino GK, Santhanam A, Wu J, Singh A, Wilson SE. Epithelial basement membrane proteins perlecan and nidogen-2 are up-regulated in stromal cells after epithelial injury in human corneas. Exp Eye Res. 2015;134:33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2015.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wilson SE, Medeiros CS, Santhiago MR. Pathophysiology of corneal scarring in persistent epithelial defects after PRK and other corneal injuries. J Ref Surg. 2018;34:59–64. doi: 10.3928/1081597X-20171128-01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shiju TM, de Oliveira RC, Wilson SE. 3D in vitro corneal models: a review of current technologies. Exp Eye Res. 2020;200:108213. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2020.108213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Santhanam A, Marino GK, Torricelli AAM, Wilson SE. EBM regeneration and changes in EBM component mRNA expression in the anterior stroma after corneal injury. Mol Vis. 2017;23:39–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Santhanam A, Torricelli AAM, Wu J, Marino GK, Wilson SE. Differential expression of epithelial basement membrane components nidogens and perlecan in corneal stromal cells in vitro. Mol Vis. 2015;21:1318–1327. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Torricelli AAM, Singh V, Agrawal V, Santhiago MR, Wilson SE. Transmission electron microscopy analysis of epithelial basement membrane repair in rabbit corneas with haze. Invest Ophth Vis Sci. 2013;54:4026–4033. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Torricelli AAM, Singh V, Santhiago MR, Wilson SE. The corneal epithelial basement membrane: structure, function and disease. Invest Ophth Vis Sci. 2013;54:6390–6400. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lassance L, Marino GK, Medeiros CS, Thangavadivel S, Wilson SE. Fibrocyte migration, differentiation and apoptosis during the corneal wound healing response to injury. Exp Eye Res. 2018;170:177–187. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2018.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Karsdal MA, Nielsen SH, Leeming DJ, Langholm LL, Nielsen MJ, Manon-Jensen T, Siebuhr A, Gudmann NS, Rønnow S, Sand JM, Daniels SJ, Mortensen JH, Schuppan D. The good and the bad collagens of fibrosis—their role in signaling and organ function. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2017;121:43–56. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2017.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Saikia P, Crabb JS, Dibbin LL, Juszczak MJ, Willard B, Jang GF, Shiju TM, Crabb JW, Wilson SE. Quantitative proteomic comparison of myofibroblasts derived from bone marrow and cornea. Sci Rep. 2020;10:16717. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-73686-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Saikia P, Thangavadivel S, Lassance L, Medeiros CS, Wilson SE. IL-1 and TGF-β modulation of epithelial basement membrane components perlecan and nidogen production by corneal stromal cells. Invest Ophth Vis Sci. 2018;59:5589–5598. doi: 10.1167/iovs.18-25202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sampaio LP, Shiju TM, Hilgert GSL, de Oliveira RC, DeDreu J, Menko AS, Santhiago MR, Wilson SE. Descemet's membrane injury and regeneration, and posterior corneal fibrosis, in rabbits. Exp Eye Res. 2021;213:108803. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2021.108803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kisling A, Lust RM, Katwa LC. What is the role of peptide fragments of collagen I and IV in health and disease? Life Sci. 2019;228:30–34. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Netto MV, Mohan RR, Sinha S, Sharma A, Dupps W, Wilson SE. Stromal haze, myofibroblasts, and surface irregularity after PRK. Exp Eye Res. 2006;82:788–797. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wilson SE, He Y-G, Weng J, Li Q, McDowall AW, Vital M, Chwang EL. Epithelial injury induces keratocyte apoptosis: hypothesized role for the interleukin-1 system in the modulation of corneal tissue organization and wound healing. Exp Eye Res. 1996;62:325–328. doi: 10.1006/exer.1996.0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mohan RR, Hutcheon AEK, Choi R, Hong J-W, Lee J-S, Mohan RR, Ambrósio R, Zieske JD, Wilson SE. Apoptosis, necrosis, proliferation, and myofibroblast generation in the stroma following LASIK and PRK. Exp Eye Res. 2003;76:71–87. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(02)00251-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wilson SE, Marino GK, Torricelli AAM, Medeiros CS. Corneal fibrosis: injury and defective regeneration of the epithelial basement membrane. A paradigm for fibrosis in other organs? Matrix Biol. 2017;64:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Medeiros CS, Saikia P, de Oliveira RC, Lassance L, Santhiago MR, Wilson SE. Descemet's membrane modulation of posterior corneal fibrosis. Invest Ophth Vis Sci. 2019;60:1010–1020. doi: 10.1167/iovs.18-26451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ramos-Lewis W, LaFever KS, Page-McCaw A. A scar-like lesion is apparent in basement membrane after wound repair in vivo. Matrix Biol. 2018;74:101–120. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2018.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nishiuchi R, Takagi J, Hayashi M, Ido H, Yagi Y, Sanzen N, Tsuji T, Yamada M, Sekiguchi K. Ligand-binding specificities of laminin-binding integrins: a comprehensive survey of laminin-integrin interactions using recombinant alpha3beta1, alpha6beta1, alpha7beta1 and alpha6beta4 integrins. Matrix Biol. 2006;25:189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Deutzmann R, Aumailley M, Wiedemann H, Pysny W, Timpl R, Edgar D. Cell adhesion, spreading and neurite stimulation by laminin fragment E8 depends on maintenance of secondary and tertiary structure in its rod and globular domain. Eur J Biochem. 1990;191:513–522. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb19151.x?sid=nlm:pubmed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ido H, Harada K, Futaki S, Hayashi Y, Nishiuchi R, Natsuka Y, Li S, Wada Y, Combs AC, Ervasti JM, Sekiguchi K. Molecular dissection of the a-dystroglycan- and integrin-binding sites within the globular domain of human laminin-10. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:10946–10954. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313626200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ido H, Nakamura A, Kobayashi R, Ito S, Li S, Futaki S, Sekiguchi K. The requirement of the glutamic acid residue at the third position from the carboxyl termini of the laminin c chains in integrin binding by laminins. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:11144–11154. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609402200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ott U, Odermatt E, Engel J, Furthmayr H, Timpl R. Protease resistance and conformation of laminin. Eur J Biochem. 1982;123:63–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1982.tb06499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Smirnov SP, McDearmon EL, Li S, Ervasti JM, Tryggvason K, Yurchenco PD. Contributions of the LG modules and furin processing to laminin-2 functions. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:18928–18937. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201880200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gee SH, Blacher RW, Douville PJ, Provost PR, Yurchenco PD, Carbonetto S. Laminin-binding protein 120 from brain is closely related to the dystrophin associated glycoprotein, dystroglycan, and binds with high affinity to the major heparin binding domain of laminin. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:14972–14980. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)82427-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kreidberg JA, Donovan MJ, Goldstein SL, Rennke H, Shepherd K, Jones RC, Jaenisch R. Alpha 3 beta 1 integrin has a crucial role in kidney and lung organogenesis. Development. 1996;122:3537–3547. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.11.3537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.DiPersio CM, Hodivala-Dilke K, Jaenisch R, Kreidberg JA, Hynes RO. α3β1 integrin is required for normal development of the epidermal basement membrane. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:729–742. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.3.729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sasaki T, Forsberg E, Bloch W, Addicks K, Fassler R, Timpl R. Deficiency of β1 integrins in teratoma interferes with basement membrane assembly and laminin-1 expression. Exp Cell Res. 1998;238:70–81. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Brakebusch C, Grose R, Quondamatteo F, Ramirez A, Jorcano JL, Pirro A, Svensson M, Herken R, Sasaki T, Timpl R, Werner S, Fässler R. Skin and hair follicle integrity is crucially dependent on beta 1 integrin expression on keratinocytes. EMBO J. 2000;19:3990–4003. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.15.3990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Vidal F, Aberdam D, Miquel C, Christiano AM, Pulkkinen L, Uitto J, Ortonne P, Meneguzzi G. Integrin β4 mutations associated with junctional epidermolysis bullosa with pyloric atresia. Nat Genetics. 1995;10:229–234. doi: 10.1038/ng0695-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dowling J, Yu QC, Fuchs E. β4 integrin is required for hemidesmosome formation, cell adhesion and cell survival. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:559–572. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.2.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Timpl R. Proteoglycans of basement membranes. Experientia. 1993;49:417–427. doi: 10.1007/BF01923586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Williamson RA, Henry MD, Daniels KJ, Hrstka RF, Lee JC, Sunada Y, Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya O, Campbell KP. Dystroglycan is essential for early embryonic development: disruption of Reichert’s membrane in Dag1-null mice. Hum Mol Gen. 1997;6:831–841. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.6.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Henry MD, Campbell KP. A role of dystroglycan in basement membrane assembly. Cell. 1998;95:859–870. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81708-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Henry MD, Satz J, Brakebusch C, Costell M, Gustafsson E, Fassler R, Campbell KP. Distinct roles for dystroglycan, β1-integrin and perlecan in cell surface laminin organization. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:1137–1144. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.6.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Montanaro F, Lindenbaum M, Carbonetto S. α-dystroglycan is a laminin receptor involved in extracellular matrix assembly on myotubes and muscle cell viability. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:1325–1340. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.6.1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kalb E, Engel J. Binding and calcium-induced aggregation of laminin onto lipid bilayers. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:19047–19052. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)55170-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Pulkkinen L, Christiano AM, Airenne T, Haakana H, Tryggvason K, Uitto J. Mutations in the gamma 2 chain gene (LAMC2) of kalinin/laminin 5 in the junctional forms of epidermolysis bullosa. Nat Genet. 1994;6:293–298. doi: 10.1038/ng0394-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pulkkinen L, Christiano AM, Gerecke DR, Wagman DW, Burgeson RE, Pittelkow MR, Uitto J. A homozygous nonsense mutation in the beta 3 gene of laminin 5 (LAMB3) in Herlitz junctional epidermolysis bullosa. Genomics. 1994;24:257–360. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Pöschl E, Schlötzer-Schrehardt U, Brachvogel B, Saito K, Ninomiya Y, Mayer U. Collagen IV is essential for basement membrane stability but dispensable for initiation of its assembly during early development. Development. 2004;131:1619–1628. doi: 10.1242/dev.01037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bezakova G, Rüegg MA. New insights into the roles of agrin. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:295–308. doi: 10.1038/nrm1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Fox JW, Mayer U, Nischt R, Aumailley M, Reinhardt D, Wiedemann H, Mann K, Timpl R, Krieg T, Engel J. Recombinant nidogen consists of three globular domains and mediates binding of laminin to collagen type IV. EMBO J. 1991;10:3137–3146. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04875.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hopf M, Göhring W, Ries A, Timpl R, Hohenester, Crystal structure and mutational analysis of a perlecan binding fragment of nidogen-1. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:634–640. doi: 10.1038/89683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Mayer U, Nischt R, Pöschl E, Mann K, Fukuda K, Gerl M, Yamada Y, Timpl R. A single EGF-like motif of laminin is responsible for high affinity nidogen binding. EMBO J. 1993;12:1879–1885. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05836.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Pozzi A, Yurchenco PD, Iozzo RV. The nature and biology of basement membranes. Matrix Biol. 2017;57–58:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2016.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Behrens DT, Villone D, Koch M, Brunner G, Sorokin L, Robenek H, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Bruckner P, Hansen U. The epidermal basement membrane is a composite of separate laminin- or collagen IV-containing networks connected by aggregated perlecan, but not by nidogens. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:18700–18709. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.336073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Gumbiner BM. Cell adhesion: the molecular basis of tissue architecture and morphogenesis. Cell. 1996;84:345–357. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81279-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Paralkar VM, Vukicevic S, Reddi AH. Transforming growth factor beta type 1 binds to collagen IV of basement membrane matrix: implications for development. Dev Biol. 1991;143:303–308. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(91)90081-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Iozzo RV, Zoeller JJ, Nystrom A. Basement membrane proteoglycans: modulators par excellence of cancer growth and angiogenesis. Mol Cells. 2009;27:503–513. doi: 10.1007/s10059-009-0069-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Gohring W, Sasaki T, Heldin CH, Timpl R. Mapping of the binding of platelet-derived growth factor to distinct domains of the basement membrane proteins BM-40 and perlecan and distinction from the BM-40 collagen-binding epitope. Eur J Biochem. 1998;255:60–66. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2550060.x?sid=nlm:pubmed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wilson SE. Interleukin-1 and transforming growth factor beta: Commonly opposing, but sometimes supporting, master regulators of the corneal wound healing response to injury. Invest Ophth Vis Sci. 2021;62:8. doi: 10.1167/iovs.62.4.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ruoslahti E, Yamaguchi Y. Proteoglycans as modulators of growth factor activities. Cell. 1991;64:867–869. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90308-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Schlessinger J, Lax I, Lemmon M. Regulation of growth factor activation by proteoglycans: what is the role of the low affinity receptors? Cell. 1995;83:357–360. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Wilson SE, Walker JW, Chwang EL, He Y-G. Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), keratinocyte growth factor (KGF), their receptors, FGF receptor-2, and the cells of the cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1993;34:2544–2561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Wilson SE, He Y-G, Weng J, Zeiske JD, Jester JV, Schultz GS. Effect of epidermal growth factor, hepatocyte growth factor, and keratinocyte growth factor, on proliferation, motility, and differentiation of human corneal epithelial cells. Exp Eye Res. 1994;59:665–678. doi: 10.1006/exer.1994.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Liang Q, Mohan RR, Chen L, Wilson SE. Signaling by HGF and KGF in corneal epithelial cells: Ras/MAP kinase and Jak-STAT pathways. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:1329–1338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]