Abstract

Objectives:

Since 2006, the U.S. human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination program has led to decreases in HPV infections caused by high-risk vaccine-targeted HPV types (HPV16/18). We assessed differences in high-risk HPV prevalence by cervical cytology result among 20–24-year-old persons participating in routine cervical cancer screening in 2015–2017 compared to 2007.

Methods:

Residual routine cervical cancer screening specimens were collected from 20–24-year-old members of two integrated healthcare delivery systems as part of a cross-sectional study and were tested for 37 HPV types. Cytology results and vaccination status (≥1 dose) were extracted from medical records. Cytology categories were normal, atypical squamous cells of undefined significance (ASCUS), low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (SIL; LSIL), or high-grade SIL/atypical squamous cells cannot exclude high-grade SIL (HSIL/ASC-H). Prevalences of HPV categories (HPV16/18, HPV31/33/45/52/58, HPV35/39/51/56/59/66/68) were estimated by cytology result for 2007 and 2015–2017.

Results:

Specimens from 2007 (n=4046) were from unvaccinated participants; 4574 of 8442 (54.2%) specimens from 2015–2017 were from vaccinated participants. Overall, HPV16/18 positivity was lower in 2015–2017 compared to 2007 in all groups: HSIL/ASC-H, 16.0% vs 69.2%; LSIL, 5.4% vs 40.1%; ASCUS, 5.0% vs 25.6%; normal, 1.3% vs 8.1%. HPV31/33/45/52/58 prevalence was stable for all cytology groups; HPV35/39/51/56/59/66/68 prevalence increased among LSIL specimens (53.9% to 65.2%) but remained stable in other groups.

Conclusions:

Prevalence of vaccine-targeted high-risk HPV types 16/18 was dramatically lower in 2015–2017 than 2007 across all cytology result groups while prevalence of other high-risk HPV types was mainly stable, supporting vaccine impact with no evidence of type replacement.

Keywords: human papillomavirus, HPV vaccine, vaccination, cervical cancer screening, prevalence, cervical cytology

Précis:

Among persons screened for cervical cancer, prevalence of vaccine-targeted high-risk HPV16/18 was dramatically lower in 2015–2017 than 2007 across all cytology result groups.

INTRODUCTION

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted infection1 and causes anogenital warts and several types of cancer, including cervical, vaginal, vulvar, anal, penile, and oropharyngeal cancers.2 In 2006, a quadrivalent HPV vaccine was licensed for U.S. females, protecting against HPV 6 and 11, types that cause nearly all cases of anogenital warts, and HPV 16 and 18, types that cause >70% of HPV-attributable cancers.3 Routine vaccination was recommended at ages 11–12 years with catch-up vaccination through age 26 years. In 2015, a 9-valent HPV vaccine (9vHPV) protecting against five additional oncogenic, or high-risk, types (HPV 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58) was recommended; by the end of 2016, this vaccine was the only vaccine available in the United States.4

In the United States, decreases in HPV infections,5 anogenital wart incidence,6 and cervical precancers7 have been seen since the start of the national vaccination program in 2006. We have previously demonstrated substantial vaccine impact between 2007 and 2015–2016 on vaccine-type HPV prevalence among persons aged 20–29 years receiving routine cervical cancer screening from an integrated healthcare delivery system (IHDS).8 In the present analysis using residual liquid-based cytology specimens from 20–24-year-old persons screened for cervical cancer participating in two IHDSs, we describe changes in the prevalence of high-risk HPV by cervical cytology result comparing HPV prevalence in 2015–2017 to 2007.

METHODS

Sample collection

Methods for sample size determination and collection of consecutive residual liquid cytology specimens from persons aged 20–24 years undergoing routine cervical cancer screening at two IHDSs (Kaiser Permanente Northwest [KPNW] and Kaiser Permanente Northern California [KPNC]) have been described in detail previously.8–11 In brief, specimens were collected in two periods, during 2007 and 2015–2017. In 2007, the sampling target from each site was approximately 2000 specimens from unvaccinated persons. In the later period, the sampling target was 1000 specimens from each site for 2015, and 1000 specimens from KPNW and 2000 from KPNC per year for both 2016 and 2017. Samples collected in 2007 from KPNC were in Digene Specimen Transport Medium (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and frozen and shipped on dry ice to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for HPV testing. All other samples were residual SurePath (TriPath Imaging, Burlington, NC, USA) samples stored at ambient temperature then shipped to the CDC. This cross-sectional study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at both KPNC and KPNW. The study used residual specimens; informed consent was not required. The Institutional Review Board at CDC approved the 2007 data collection; later years were given a determination of non-engagement.

Laboratory methods

Laboratory methods have been described in detail previously.9 In brief, the Research Use Only Linear Array HPV Genotyping Test (Roche Molecular Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) was used to provide type-specific results for 37 HPV types: HPV6/11/16/18/26/31/33/35/39/40/42/45/51/52/53/54/55/56/58/59/61/62/64/66/67/68/69/70/71/72/73/81/82/83/84/89/IS39. Specimens that were HPV negative and failed to amplify the positive control (β globin) were excluded from analysis (<0.1% of specimens).

Statistical methods

HPV vaccination status (receipt of ≥1 dose) at the time of specimen collection was obtained from administrative and electronic health records; percent vaccinated was calculated for 2015–2017, but not for 2007 as all specimens in 2007 were from unvaccinated persons. We described the distribution of cervical cytology results detected using liquid-based cytology in each sampling period (2007 and 2015–2017) and by vaccination status in 2015–2017. Cytology results were extracted from the electronic medical records and laboratory testing databases at each participating site and classified as normal, atypical squamous cells of undefined significance (ASCUS), low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL), atypical squamous cells cannot exclude high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (ASC-H), or high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL). Samples with no available cytology result and those classified as atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance (AGUS) were excluded from analysis (<0.1% of sampled specimens). HSIL and ASC-H were combined due to the small number of these outcomes. The percent of each cytology type in 2015–2017 was compared with the percent in 2007 using Chi-square tests.

We also described prevalence of the following four HPV type categories in each period by cytology result: HPV 16/18, five additional 9vHPV types (HPV 31/33/45/52/58), other high-risk HPV (HPV 35/39/51/56/59/66/68), and any high-risk HPV (HPV 16/18/31/33/35/39/45/51/52/56/58/59/66/68). Categories were not mutually exclusive; a specimen may be positive for more than one category. For each cytology result, the prevalence of each HPV type category in 2015–2017 was compared to the prevalence in 2007 using Fisher’s Exact tests due to the small number of some outcomes. Among specimens positive for at least one high-risk HPV type, we describe the number of positive high-risk types; number of positive high-risk types was categorized as positive for 1 type, 2 types, 3 types, or ≥4 types.

All data management and statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (2013, Cary, NC, USA). An alpha level of .05 was used for all statistical tests.

Role of funding source

This work was funded by the CDC. Funding for data collection and subject matter expertise was provided by CDC to KPNW and KPNC. CDC performed all specimen testing, statistical analyses, and initial manuscript preparation. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission; the corresponding author (RML) had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

RESULTS

A total of 12,505 samples were collected from persons aged 20–24 years participating in routine cervical cancer screening. Of those, nine had inadequate HPV typing results, three were missing or had inadequate cytology results, one had inadequate typing and cytology results, and four had AGUS as their cytology result and were excluded, resulting in a final sample size for this analysis of 12,488. The 4046 specimens from 2007 were from unvaccinated persons. In 2015–2017, 4574 of 8442 (54.2%) specimens were from vaccinated persons.

The proportion of specimens with a normal cytology result decreased from 93.4% in 2007 to 87.3% in 2015–2017 while the proportions of the other three categories increased (Table 1). The largest increase was in the percent with an ASCUS result, which increased from 2.1% to 6.4%. There were smaller increases for LSIL (4.1% to 5.8%) and HSIL/ASC-H (0.3% to 0.6%). In 2015–2017, the proportion with each cytology result differed by 0.1% between unvaccinated and vaccinated participants (data not shown).

Table 1.

Distribution of cytology results among 20–24-year-old participants, 2007 and 2015–2017

| N (column %) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Cytology result | 2007 | 2015–2017 |

| Normal | 3780 (93.4%) | 7370 (87.3%)** |

| ASCUS | 86 (2.1%) | 537 (6.4%)** |

| LSIL | 167 (4.1%) | 485 (5.8%)** |

| HSIL/ASC-H | 13 (0.3%) | 50 (0.6%)* |

| Total | 4046 (100%) | 8442 (100%) |

p-value <0.05 from Chi-square test comparing percents in 2007 and 2015–2017

p-value <0.0001 from Chi-square test comparing percents in 2007 and 2015–2017

ASCUS, atypical squamous cells of undefined significance; LSIL, low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions; HSIL, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions; ASC-H, atypical squamous cells, cannot exclude high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion.

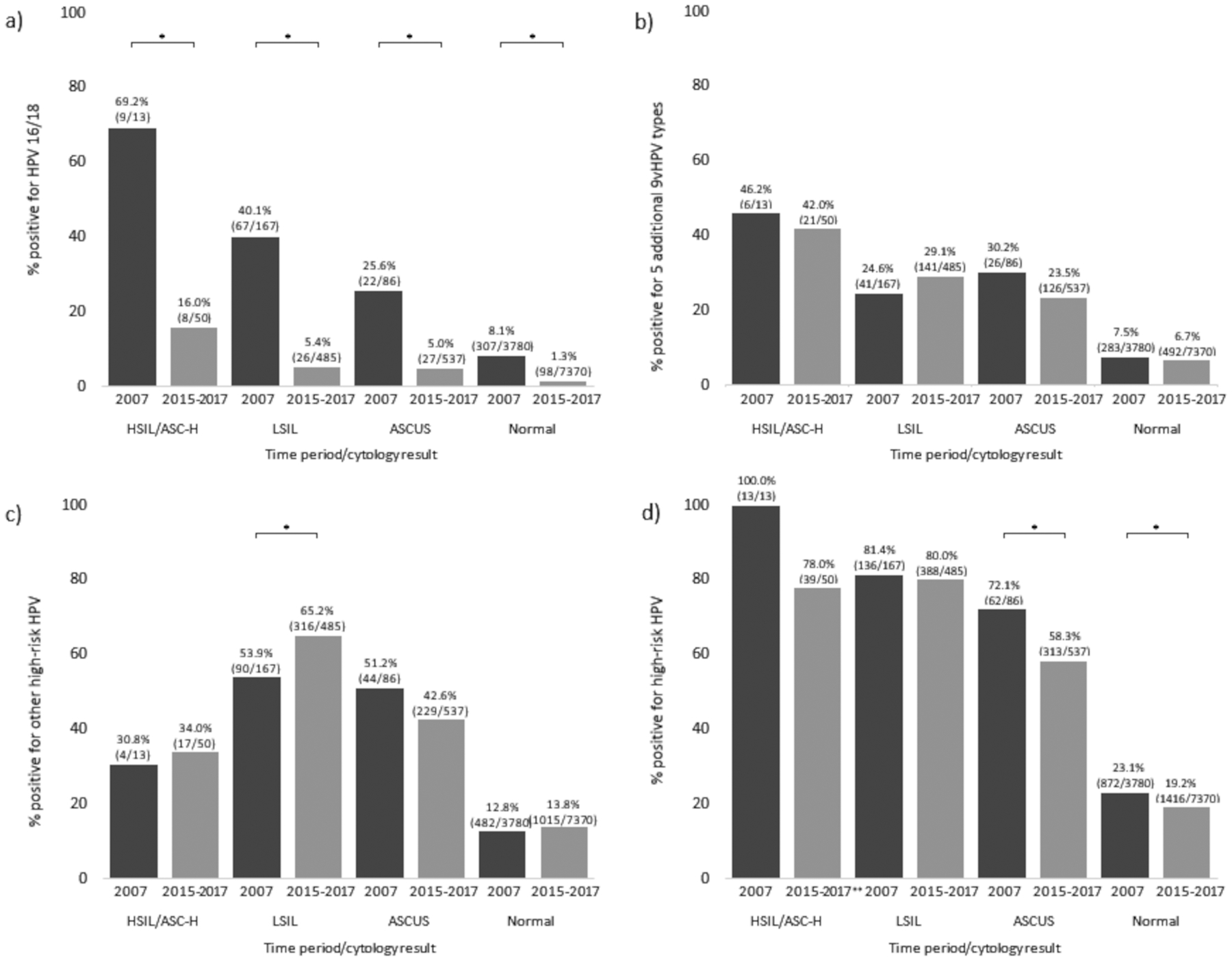

Compared to 2007, the proportion positive for HPV 16/18 was significantly lower in 2015–2017 across all cytology categories (all p-values <0.001; Figure 1, panel a). The proportion of specimens positive for HPV 16/18 decreased from 69.2% to 16.0% among those with HSIL/ASC-H cytology, 40.1% to 5.4% among those with LSIL, 25.6% to 5.0% among those with ASCUS, and 8.1% to 1.3% among those with normal cytology. The proportion of specimens testing positive for the additional five types in 9vHPV did not change significantly in any of the cytology groups (all p-values >0.1; Figure 1, panel b). The proportion testing positive for other high-risk HPV increased from 53.9% to 65.2% in specimens with LSIL cytology (p-value = 0.01) but remained stable in specimens with HSIL/ASC-H, ASCUS, and normal cytology (all p-values >0.1; Figure 1, panel c). Over 50% of specimens with abnormal cytology (ASCUS, LSIL, or HSIL/ASC-H) were positive for any high-risk HPV in both time periods; among specimens with normal cytology, approximately 20% were positive for any high-risk HPV (Figure 1, panel d). Any high-risk HPV prevalence was lower in 2015–2017 compared to 2007 for specimens with ASCUS and normal cytology.

Figure 1:

Prevalence of high-risk HPV categories by cytology result among 20–24-year-old participants, 2007 and 2015–2017, a) HPV 16/18, b) 5 additional 9vHPV types, c) other high-risk HPV, d) any high-risk HPV.

ASCUS, atypical squamous cells of undefined significance; LSIL, low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions; HSIL, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions; ASC-H, atypical squamous cells, cannot exclude high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion.

HPV 16/18, 5 additional 9vHPV types (HPV 31/33/45/52/58), other high-risk HPV (HPV 35/39/51/56/59/66/68), and any high-risk HPV (HPV 16/18/31/33/35/39/45/51/52/56/58/59/66/68).

*Significant difference in prevalence between 2007 and 2015–2017 using Fisher’s Exact test (p-value <0.05)

Numbers in parentheses represent number of specimen positive for the relevant HPV category/total number of specimens in the relevant cytologic outcome-time period group.

**Among HSIL specimens that were negative for high-risk HPV, specimens were positive for the following types: three were positive for HPV 53 and HPV 73, one for HPV 67, one for HPV 82 and HPV 89, one for HPV 64 and HPV 89, one for HPV 61 and HPV 82, and one for HPV82. Three were negative for all 37 HPV types.

Multiple high-risk type infections were common; among specimens positive for at least one high-risk HPV type (n = 1083 in 2007; n = 2156 in 2015–2017), 32.4% in 2007 and 30.2% in 2015–2017 were positive for more than one high-risk type (Table 2). The number of positive high-risk types varied by cytology result. Among specimens positive for high-risk HPV, a lower proportion of LSIL were positive for only a single type (47.1% in 2007, 57.0% in 2015–2017) than other cytology categories. Among those with normal cytology, 71.8% in 2007 and 75.1% in 2015–2017 were positive for only a single type. For all abnormal cytology results among high-risk HPV positive specimens, the percent with a single type infection was higher in 2015–2017 compared to 2007 (i.e., fewer specimens had multiple type infections in 2015–2017).

Table 2:

Distribution of number of high-risk HPV types detected among specimens positive for at least one high-risk HPV type by cytology result, 2007 and 2015–2017

| Specimens positive, n (row %) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 (n = 1083) |

2015–2017 (n = 2156) |

||||||||

| Number of high-risk types | Number of high-risk types | ||||||||

| Cytology result | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4+ | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4+ | |

| Normal | 626 (71.8) | 178 (20.4) | 48 (5.5) | 20 (2.3) | 1063 (75.1) | 278 (19.6) | 61 (4.3) | 14 (1.0) | |

| ASCUS | 35 (56.5) | 14 (22.6) | 9 (14.5) | 4 (6.5) | 195 (62.3) | 78 (24.9) | 28 (9.0) | 12 (3.8) | |

| LSIL | 64 (47.1) | 46 (33.8) | 16 (11.8) | 10 (7.4) | 221 (57.0) | 122 (31.4) | 29 (7.5) | 16 (4.1) | |

| HSIL/ASC-H | 7 (53.9) | 5 (38.5) | 1 (7.7) | 0 | 26 (66.7) | 10 (25.6) | 3 (7.7) | 0 | |

| Total | 732 (67.6) | 243 (22.4) | 74 (6.8) | 34 (3.1) | 1505 (69.8) | 488 (22.6) | 121 (5.6) | 42 (2.0) | |

ASCUS, atypical squamous cells of undefined significance; LSIL, low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions; HSIL, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions; ASC-H, atypical squamous cells, cannot exclude high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion.

Note: The following number of specimens were HPV negative by cytology result and year - 2007: 2520 Normal, 11 ASCUS, 10 LSIL, 0 HSIL/ASC-H; 2015–2017: 4964 Normal, 122 ASCUS, 26 LSIL, 3 HSIL/ASC-H. The following numbers of specimens were positive for non-high-risk HPV types only - 2007: 388 Normal, 13 ASCUS, 21 LSIL, 0 HSIL/ASC-H; 2015–2017: 990 Normal, 102 ASCUS, 71 LSIL, 8 HSIL/ASC-H.

DISCUSSION

Approximately 10 years after the national HPV vaccination program was introduced, dramatic decreases in the prevalence of HPV 16/18 were seen in specimens from participants aged 20–24 years receiving routine cervical cancer screening at two IHDSs. Among specimens with a cytology result of HSIL/ASC-H, the cytological results most predictive of detection of high grade cervical precancers, the percent of specimens positive for HPV 16/18 significantly decreased from 69% to 16%. The substantial declines observed in HPV 16/18 in high grade cytological outcomes combined with stable prevalence of other oncogenic types suggest a future reduction in progression to invasive cervical cancer.

Similar to our data, prior research has consistently shown HPV 16/18 prevalence increases with severity of cytology grade.12–14 Our 2007 data are similar to observations from a U.S. study conducted prior to the implementation of the national vaccination program.14 Among a sample of women with a median age of 25 years, HPV 16 and HPV 18 prevalences increased with cytology grade severity; prevalences of HPV 16 and HPV 18 were 29.8% and 12.5% among those with LSIL and 57.8% and 11.1% among those with HSIL; our HPV 16/18 prevalence was 40% among those with LSIL and 69% among those with HSIL/ASC-H. Prevalence estimates from our study were substantially lower in 2015–2017 than in 2007; however, increases in HPV 16/18 prevalence with cytology severity were still observed. Our data, as well as other data, also show that multiple type infections are common overall and more common among those with abnormal than normal cytology results.13, 14

HPV 16 is the most carcinogenic HPV type; abnormal cytological outcomes caused by HPV 16 are more likely to progress to cervical cancer than are outcomes due to other HPV types.15 The significant reduction in HPV 16/18 positive specimens reflects substantial vaccine impact in this population. In previously published analyses, we reported ecologic vaccine impact, vaccine effectiveness, and evidence of herd effects from vaccination among persons in their 20s attending these IHDSs using prevalence data regardless of cytologic result.8 Similarly, in the present report, we also found that prevalence of vaccine-targeted types decreased dramatically. Additionally, in nearly all comparisons, prevalence of other high-risk types did not increase, suggesting it is very unlikely type replacement is occurring. In the later time period (2015–2017), specimens were also positive for a smaller number of high-risk types.

The increases that we found in the proportion of specimens with an abnormal cytology result may be due to changes in screening recommendations. Prior to 2012, routine cervical cancer screening was recommended for women who have been sexually active.16 In 2012, the routine recommendation was updated, and screening of women aged 20 years or younger was not recommended.17 This change likely resulted in a slightly older sample during 2015–2017 compared to 2007, when persons aged 20 years were more likely to be included in the study, and may have resulted in a sample of participants with more abnormal cytology. Among persons who received cervical cancer screening, rates of high-grade histological outcomes are substantially higher among persons aged 21–24 years compared to those aged 18–20 years.18 One limitation of the present study is the lack of demographic data, including exact age, for the participants in 2007. We were unable to determine if there were differences in the age distribution of the samples as 5-year age group and study site were the only demographic variables available for the first time period.9, 11

Our 2015–2017 data indicate 20% of specimens from persons with normal cytology results were positive for at least one high-risk HPV type included in clinical HPV screening tests. Our assay is more sensitive than some clinical HPV tests and may overestimate the percent of persons who would be recommended for clinical follow-up.19 Nevertheless, these results highlight the need to evaluate triage options to balance sensitivity with the need to minimize follow-up testing.

This study is subject to a few limitations. First, specimens were collected from persons receiving routine cervical cancer screening attending an IHDS. This sample may not be representative of persons who receive routine screening in other settings or who do not receive routine screening. Second, we lack demographic information for the earlier sampling era as noted above. Third, there were site-specific differences in the laboratory methods used during 2007.9 In 2015–2017, both sites used the same methods; changes in methodology may have affected temporal differences.

In summary, comparing 2015–2017 with 2007, there were dramatic decreases in the proportion of specimens within all cytologic categories that were positive for HPV 16/18, which cause 70% of HPV-attributable cancers. These decreases occurred while prevalence of other high-risk types largely remained stable, suggesting type replacement is likely not occurring. These data add to other research demonstrating impact of HPV vaccination program in the United States.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Judy Donald, Kristine Bennett, Sarah Vertrees, Ceilidh Nichols, and Charlie Chao for help with data and/or specimen collection; Sonya Patel and Krystle Love for technical expertise in HPV testing; Eileen Dunne for work on the first phase of this project.

Financial support:

This work was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Conflicts of interest:

ALN has received research funding from Pfizer, Takeda, MedImmune, and Merck for unrelated studies. NPK has received research funding from Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi Pasteur, Novartis, MedImmune, Pfizer, and Protein Sciences (now Sanofi Pasteur) for unrelated studies. SW has received research funding from GlaxoSmithKline for an unrelated study. None of the other authors have potential conflicts of interest to declare.

ABBREVIATIONS

- 9vHPV

9-valent HPV vaccine

- AGUS

atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance

- ASC-H

atypical squamous cells cannot exclude high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions

- ASCUS

atypical squamous cells of undefined significance

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- HPV

human papillomavirus

- HSIL

high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions

- IHDS

integrated healthcare delivery system

- KPNC

Kaiser Permanente Northern California

- KPNW

Kaiser Permanente Northwest

- LSIL

low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions

- SIL

squamous intraepithelial lesions

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

IRB status: Approved at Kaiser Permanente Northwest and Kaiser Permanente Northern California, Determination of non-engagement at Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

References:

- 1.Kreisel KM, Spicknall IH, Gargano JW, et al. Sexually transmitted infections among US women and men: prevalence and incidence estimates, 2018. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2020;48(4):208–214. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Senkomago V, Henley SJ, Thomas CC, Mix JM, Markowitz LE, Saraiya M. Human papillomavirus-attributable cancers - United States, 2012–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Aug 23 2019;68(33):724–728. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6833a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, Lawson HW, Chesson H, Unger ER. Quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. Mar 23 2007;56(Rr-2):1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meites E, Szilagyi PG, Chesson HW, Unger ER, Romero JR, Markowitz LE. Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Aug 16 2019;68(32):698–702. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6832a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenblum HG, Lewis RM, Gargano JW, Querec TD, Unger ER, Markowitz LE. Declines in prevalence of human papillomavirus vaccine-type infection among females after introduction of vaccine - United States, 2003–2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Mar 26 2021;70(12):415–420. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7012a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flagg EW, Torrone EA. Declines in anogenital warts among age groups most likely to be impacted by human papillomavirus vaccination, United States, 2006–2014. Am J Public Health. Jan 2018;108(1):112–119. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2017.304119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McClung NM, Gargano JW, Park IU, et al. Estimated number of cases of high-grade cervical lesions diagnosed among women - United States, 2008 and 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Apr 19 2019;68(15):337–343. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6815a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Markowitz LE, Naleway AL, Lewis RM, et al. Declines in HPV vaccine type prevalence in women screened for cervical cancer in the United States: evidence of direct and herd effects of vaccination. Vaccine. Jun 27 2019;37(29):3918–3924. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.04.099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunne EF, Klein NP, Naleway AL, et al. Prevalence of HPV types in cervical specimens from an integrated healthcare delivery system: baseline assessment to measure HPV vaccine impact. Cancer Causes Control. Feb 2013;24(2):403–7. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-0085-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunne EF, Naleway A, Smith N, et al. Reduction in human papillomavirus vaccine type prevalence among young women screened for cervical cancer in an integrated US healthcare delivery system in 2007 and 2012–2013. J Infect Dis. Dec 15 2015;212(12):1970–5. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Markowitz LE, Naleway AL, Klein NP, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccine effectiveness against HPV infection: evaluation of one, two, and three doses. J Infect Dis. Mar 2 2020;221(6):910–918. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guan P, Howell-Jones R, Li N, et al. Human papillomavirus types in 115,789 HPV-positive women: A meta-analysis from cervical infection to cancer. Int J Cancer. 2012;131(10):2349–2359. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wheeler CM, Hunt WC, Cuzick J, et al. A population-based study of human papillomavirus genotype prevalence in the United States: baseline measures prior to mass human papillomavirus vaccination. Int J Cancer. Jan 1 2013;132(1):198–207. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wentzensen N, Schiffman M, Dunn T, et al. Multiple human papillomavirus genotype infections in cervical cancer progression in the study to understand cervical cancer early endpoints and determinants. Int J Cancer. Nov 1 2009;125(9):2151–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.International Agency for Research on Cancer. Biological agents. Volume 100 B. A review of human carcinogens. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2012;100(Pt B):1–441. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for cervical cancer: recommendations and rationale. Am J Nurs. Nov 2003;103(11):101–2, 105–6, 108–9. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moyer VA. Screening for cervical cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. Jun 19 2012;156(12):880–91, w312. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-12-201206190-00424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gargano JW, Park IU, Griffin MR, et al. Trends in high-grade cervical lesions and cervical cancer screening in 5 States, 2008–2015. Clin Infect Dis. Apr 8 2019;68(8):1282–1291. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phillips S, Garland SM, Tan JH, Quinn MA, Tabrizi SN. Comparison of the Roche Cobas(®) 4800 HPV assay to Digene Hybrid Capture 2, Roche Linear Array and Roche Amplicor for detection of high-risk human papillomavirus genotypes in women undergoing treatment for cervical dysplasia. J Clin Virol. Jan 2015;62:63–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2014.11.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]