Abstract

Background:

During the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic raging around the world, the effectiveness of respiratory support treatment has dominated people’s field of vision. This study aimed to compare the effectiveness and value of high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) with noninvasive ventilation (NIV) for COVID-19 patients.

Methods:

A comprehensive systematic review via PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane, Scopus, WHO database, China Biology Medicine Disc (SINOMED), and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) databases was conducted, followed by meta-analysis. RevMan 5.4 was used to analyze the results and risk of bias. The primary outcome is the number of deaths at day 28. The secondary outcomes are the occurrence of invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV), the number of deaths (no time-limited), length of intensive care unit (ICU) and hospital stay, ventilator-free days, and oxygenation index [partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2)/fraction of inhaled oxygen (FiO2)] at 24 h.

Results:

In total, nine studies [one randomized controlled trial (RCT), seven retrospective studies, and one prospective study] totaling 1582 patients were enrolled in the meta-analysis. The results showed that the incidence of IMV, number of deaths (no time-limited), and length of ICU stay were not statistically significant in the HFNC group compared with the NIV group (ps = 0.71, 0.31, and 0.33, respectively). Whereas the HFNC group performed significant advantages in terms of the number of deaths at day 28, length of hospital stay and oxygenation index (p < 0.05). Only in the ventilator-free days did NIV show advantages over the HFNC group (p < 0.0001).

Conclusion:

For COVID-19 patients, the use of HFNC therapy is associated with the reduction of the number of deaths at day 28 and length of hospital stay, and can significantly improve oxygenation index (PaO2/FiO2) at 24 h. However, there was no favorable between the HFNC and NIV groups in the occurrence of IMV. NIV group was superior only in terms of ventilator-free days.

Keywords: coronavirus disease 2019, high-flow nasal cannula, noninvasive ventilation

Introduction

The outbreak of novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has caused untold harm and challenges to people in more than 200 countries and territories around the world. To this day, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) continues to ravage the planet, with more than 270 million people infected with COVID-19 worldwide. 1 Pneumonia caused by SARS-CoV-2 differs from community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) and hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP)/ventilator-associated pneumonia in that it is highly transmissible from person to person and can even infect people asymptomatically.2,3 Patients with severe COVID-19 can trigger acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS),4,5 which can progress to acute respiratory failure (ARF), manifested by severe hypoxemia and dyspnea. What’s more, hypoxemia is associated with more rapid disease progression and higher mortality. Currently, the choice of ventilation support treatment for patients with COVID-19 is particularly important.

Traditionally, when encountering severe respiratory diseases, medical staff would first think of invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV), because years of experience have shown that it is a potential intervention to save the lives of acute patients. However, years of clinical experience have taught us that IMV is a risk factor for the development of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP). 6 Long-term IMV is a major risk factor for patients with hospital-acquired infections, which may worsen the patient’s condition and is associated with a high mortality rate in hospital. 7 Noninvasive ventilation (NIV) can reduce intubation rate in COVID-19 patients with ARF, shorten length of stay, and reduce in-hospital mortality. NIV is the delivery of a specific flow of fresh gas to the lungs without an invasive endotracheal airway. It can both give a certain flow of oxygen alone via a nasal cannula or a face mask and can also be connected to a ventilator and used in combination with the PEEP (positive end-expiratory pressure) or CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure) mode of the ventilator to give the patient noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV) support. 8 Although oxygen flow is limited to no more than 15 l/min with conventional NIV equipment, the high flow nasal cannula (HFNC) is a relatively new respiratory support technology that serves as an alternative to standard oxygen therapy by delivering an air/oxygen mixer and connecting to the nasal cannula via an actively heated humidifier. It provides adequate heated and humidified medical gases at a flow rate of 15–70 l/min via the nasal route, provides positive airway pressure effect, and reduces anatomic dead space, respiratory rate, and work of breathing.9,10 Therefore, HFNC is considered to have several physiological advantages compared with other standard oxygen therapies. 11 In actual clinical practice, the physician can choose different forms of respiratory support depending on the patient’s condition, such as noninvasive mechanical ventilation (NIMV), HFNC, helmet ventilation, and IMV. Individualized ventilation support treatment for COVID-19 patients is of great significance to avoid endotracheal intubation, reduce the mortality of intensive care unit (ICU) patients, and improve the prognosis of patients.

The fact that COVID-19 will continue to exist and expand its impact has been recognized by experts around the world. According to our data search, the amount of meta-analysis that compares the ventilation strategies of COVID-19 patients is very limited. Therefore, it is essential to compare the various ventilation treatment strategies suitable for patients with COVID-19. On this premise, we conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis, with the purpose of comparing HFNC with NIV and exploring which one can better reduce the occurrence of IMV and the death at 28 days of COVID-19 patients.

Methods

Search strategy

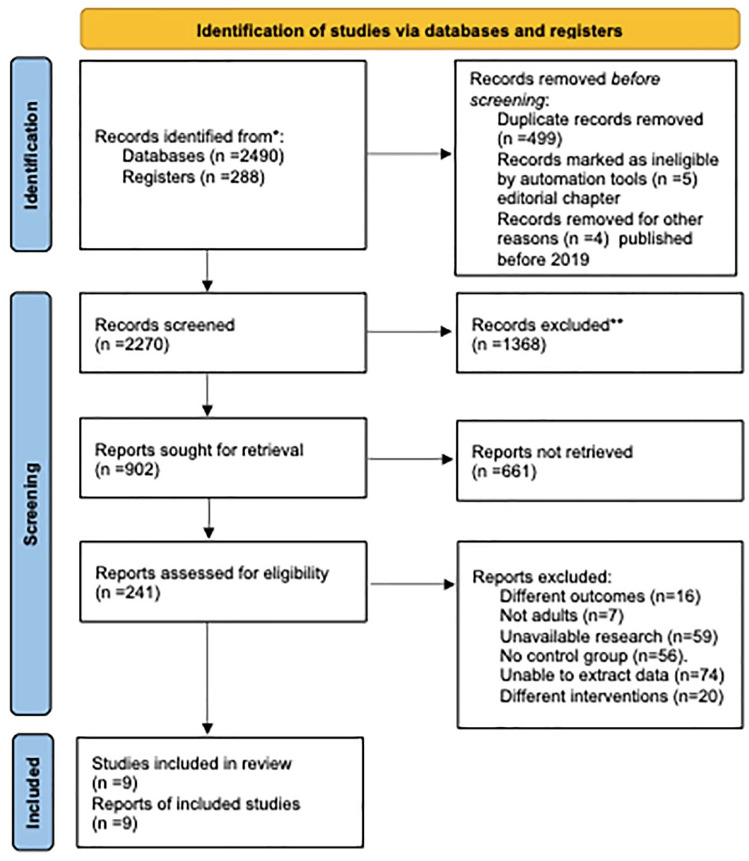

This systematic review and meta-analysis was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. We followed the PRISMA checklist to complete the current meta-analysis. To identify studies comparing the efficacy of HFNC with conventional oxygen therapy in COVID-19 patients, two investigators (Y.W.H. and X.W.) systematically searched PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane, Scopus, WHO database, China Biology Medicine Disc (SINOMED), and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) databases for relevant articles published before 20 October 2021. The whole retrieval process is shown in Figure 1. The search terms are as follows: ((High-flow Nasal Cannula OR HFNC OR High flow nasal cannula therapy OR nasal high flow OR high flow nasal therapy OR high flow oxygen therapy OR high flow therapy OR HFNO OR high flow nasal oxygen [Title/Abstract])) AND (2019-nCoV OR nCoV-2019 OR novel Coronavirus 2019 OR SARS-CoV-2 OR COVID-19 OR coronavirus OR coronavirus covid-19 OR nCoV OR corona virus [Title/Abstract]). For different databases, we will use different search formulas to avoid omissions.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of search strategy and included studies.

Study selection

The retrieved literature was managed using EndNote X9 (Thomson Reuters, NY, USA). After excluding duplicates and nonclinical studies, we (Y.W.H., N.L., and X.H.Z.) screened the literature for titles, abstracts, and keywords, respectively. In this process, we rated the studies by using the starring feature of EndNote X9. Two investigators marked the studies with low relevance as ‘one star’, the controversial research that required two investigators to re-screen them marked as ‘two or three stars’, and the undoubted study is ‘four or five stars’. The studies with one star can be excluded at once by a single investigator, two or three stars’ studies need extra evaluation by all the investigators, and the research with four or five stars can be included in this meta-analysis. We used the modified methodological index for nonrandomized studies (MINORS) score12,13 to evaluate the quality of nonrandomized controlled trials (NRCTs) and excluded studies with a total score of ⩽12. Finally, two researchers identified the included literature based on the full text. When the results of the two researchers diverged, the opinion of a researcher (W.H.M.) was used to reach a consensus. Figure 1 includes a screening process to illustrate the number of studies that we exclude at each stage.

Eligibility criteria

For the inclusion of this systematic review and meta-analysis, studies had to meet the following criteria: randomized controlled trials (RCTs), observational cohort studies, or retrospective studies that compare the efficacy of HFNC with conventional oxygenation therapy in the patients with COVID-19. There was no restriction in terms of the type of conventional oxygenation therapy. Excluded studies had the following characteristics: case reports or case series, guidelines, expert consensus, animal experiments, protocol, reviews, meta-analysis, conference abstract, letters, comments, experiences, survey, and clinical trials with different observational indicators.

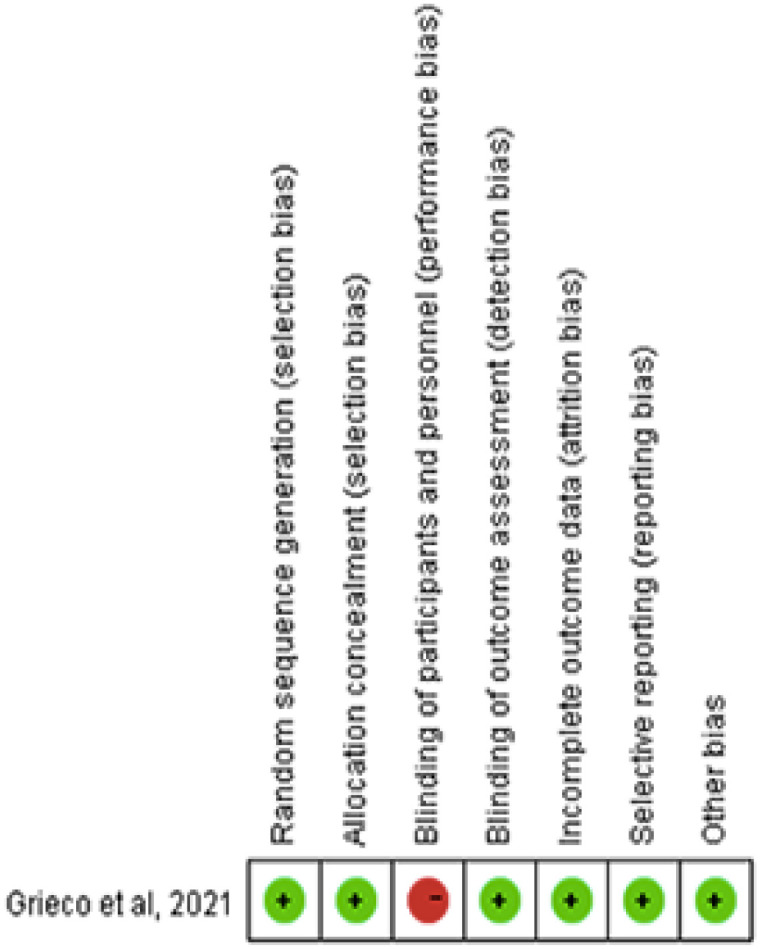

Risk of bias assessment

Three investigators (Y.W.H., N.L., and X.H.Z.) used the Cochrane collaboration tool to assess the risk of bias of studies. This information was recorded and evaluated in RevMan 5.4 (Review Manager, Versio 5.4, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014). The risk of bias summary is shown in Figure 2. When researchers disagree on the biased analysis of the same study, another researcher (W.H.M.) will make the decision.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors’ judgments about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Data extraction

Three investigators independently extracted the relevant information and data. All differences are double-checked, and W.H.M. was responsible for handling different points of view. According to the modified MINORS score, we will analyze the data included in the NRCT and complete the quality assessment (Table 1). We extracted the following data based on the characteristics of the included studies – groups, nationals, type of hospital, ages, gender, body mass index (BMI), and comorbidities – and summarized in Table 2. And also, we extracted the intervention characteristics of studies in Table 3.

Table 1.

Modified MINORS score of all eligible NRCT.

| Author | Year | Consecutive patients | Prospective data collection | Reported endpoints | Unbiased outcome evaluation | Appropriate controls | Contemporary groups | Groups equivalent | Sample size | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teng et al. 14 | 2020 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 12 |

| Bonnet et al. 15 | 2021 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 14 |

| Sayan et al. 16 | 2021 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 13 |

| Hansen et al. 17 | 2021 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 15 |

| Burnim et al. 18 | 2022 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 12 |

| Jarou et al. 19 | 2021 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 14 |

| Kabak et al. 20 | 2021 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 12 |

| Duan et al. 21 | 2020 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 13 |

MINORS, methodological index for nonrandomized studies; NRCT, nonrandomized controlled trial.

Only studies with scores ⩾12 can be included in the meta-analysis.

Table 2.

Evaluated patients’ characteristics (n = 9).

| Source National |

Type of hospital | Group: n | Ages | Female/male | BMI (kg/m2) | Comorbidity (DM/HT/CHD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teng et al.

14

China |

A tertiary care medical center | HFNC: 60 | Mean (SD): 56.6 (3.0) | 4/8 | NR | (3/7/1) |

| NIV: 60 | Mean (SD): 53.5 (5.5) | 3/7 | NR | (3/4/0) | ||

| Bonnet et al.

15

France |

NR | HFNC: 76 | Median (IQR): 60 (52–67) | 14/62 | Median (IQR): 29 (25–33) | (24/37/NR) |

| NIV: 62 | Median (IQR): 60 (51–67) | 12/50 | Median (IQR): 27 (26–33) | (19/19/NR) | ||

| Sayan et al.

16

Turkey |

NR | HFNC: 32 | Mean (SD): 63.3 (12.1) | 7/17 | Mean (SD): 26.5 (2.6) | (3/6/2) |

| NIV: 32 | Mean (SD): 69.5 (12.3) | 6/13 | Mean (SD): 26.5 (3.2) | (5/12/3) | ||

| Hansen et al.

17

America |

A tertiary care medical center | HFNC: 30 | Mean (SD): 68.6 (12.5) | 9/21 | Mean (SD): 32.2 (8.1) | (9/16/1) |

| NIV: 62 | Mean (SD): 68.3 (11.9) | 25/37 | Mean (SD): 31.4 (9.8) | (27/45/13) | ||

| Grieco et al.

22

Italy |

NR | HFNC: 55 | Median (IQR): 63 (55–69) | 9/46 | Median (IQR): 28 (26–31) | (10/33/NR) |

| NIV: 54 | Median (IQR): 66 (57–72) | 12/42 | Median (IQR): 27 (26–30) | (13/24/NR) | ||

| Burnim et al.

18

America |

Five hospitals of the JHHS | HFNC: 423 | Median (IQR): 64 (10.2) | 190/233 | Median (IQR): 29.6 (4.9) | (216/288/215) |

| NIV: 423 | Median (IQR): 65 (13) | 181/242 | Median (IQR): 29.3 (4.8) | (181/273/219) | ||

| Jarou et al.

19

America |

A large, urban, quaternary, academic medical center and level I trauma center | HFNC: 95 | Median (IQR): 63 (57–76) | 47/48 | Median (IQR): 30.8 (24.9–38.0) | (45/83/NR) |

| NIV: 28 | Median (IQR): 69 (57.8–73) | 12/16 | Median (IQR): 31.9 (29.8–38.8) | (15/20/NR) | ||

| Kabak et al.

20

Turkey |

NR | HFNC: 26 | Mean (SD): 62.30 (15.73) | 7/19 | NR | (3/16/3) |

| NIV: 28 | Mean (SD): 65.28 (13.32) | 11/17 | NR | (7/16/2) | ||

| Duan et al.

21

China |

Four tertiary care medical centers | HFNC: 23 | Mean (SD): 65 (14) | 11/12 | NR | (4/6/NR) |

| NIV: 13 | Mean (SD): 50 (14) | 1/12 | NR | (0/3/NR) |

BMI, body mass index; CHD, coronary heart disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; HFNC, high-flow nasal cannula; HT, hypertension; IQR, interquartile range; JHHS, Johns Hopkins Health System; NIV, noninvasive ventilation; NR, no record; SD, standard deviation.

Table 3.

Evaluated intervention characteristics (n = 9).

| Source | Concomitant medications | Group | Oxygen therapy apparatus | Oxygenation strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teng et al. 14 | NR | HFNC | Optiflow PT101AZ (Fisher & Paykel Healthcare, Auckland, New Zealand) | Temperature: 37°C Flow rate: 50 l/min Oxygen concentration: 50% SpO2: above 93% Duration of continuous treatment: 72 h |

| NIV | Nasal catheters or common masks (including Venturi and oxygen storage masks) | Flow rate: 5 l/min SpO2: above 93% Duration of continuous treatment: 72 h |

||

| Bonnet et al. 15 | Catecholamine, antiviral agents, immunomodulator therapy | HFNC | Oxygen was passed through a heated humidifier (MR850 and AIRVO 2, Fisher & Paykel Healthcare) and applied continuously through large-bore binasal prongs | Flow rate: 60 l/min FiO2: 1.0 at initiation SpO2: above 92%. Position: supine |

| NIV | Non-rebreather face masks | Flow rate: 6 l/min or more SpO2: above 92%. |

||

| Sayan et al. 16 | Prophylactic anticoagulation therapy | HFNC | NR | Temperature: 31–37°C Flow rate: 30–60 l/min FiO2: 40–90% SpO2: above 93% Treatment was applied continuously at the beginning; intermittent application was started after P/F >250 and clinical well-being occurred |

| NIV | Reservoir masks | Flow rate: 6–15 l/min SpO2: above 93% |

||

| Hansen et al. 17 | Convalescent plasma, hydroxychloroquine, steroids, tocilizumab, statin, azithromycin | HNFC | PM5200 air-oxygen blender (Precision Medical, Northampton, PA, USA) | Flow rate: 20–600 l/min FiO2: 21–100% SpO2: above 92% |

| NIV | Non-rebreather masks or reservoir nasal cannula | Flow rate: 10–150 l/min | ||

| Grieco et al. 22 | Dexamethasone, remdesivir | HFNC | Fisher & Paykel Healthcare | Temperature: 37°C or 34°C Flow rate: 600 l/min FiO2: 40–90% SpO2: 92–98% After 48 h, weaning from high-flow oxygen was allowed if the FiO2 ⩽40% and the RR ⩽25 breaths/min |

| NIV | Helmet NIV with pressure support mode | PEEP: 10–12 cm H2O SpO2: 92–98% After 48 h, weaning from helmet ventilation was allowed if the FiO2 ⩽40% and the RR ⩽25 breaths/min |

||

| Burnim et al. 18 | Hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin, corticosteroids, remdesivir | HFNC | NR | NR |

| NIV | NR | NR | ||

| Jarou et al. 19 | NR | HFNC | NR | Flow rate: 40 l/min at initiation, 60 l/min after

titration FiO2: 100% RR: ⩾30 breaths/min SpO2: 92–96% |

| NIV | Nasal cannula | Flow rate: ⩾6 l/min | ||

| Kabak et al. 20 | Wide-spectrum antibiotics, low-molecular-weight heparin, low-dose steroids, high-dose vitamin C, vitamin D, and tocilizumab or anakinra | HFNC | NR | NR |

| NIV | Non-rebreather masks and nasal cannula | NR | ||

| Duan et al. 21 | NR | HFNC | NR | Temperature: 31–37°C Flow rate: 30–60 l/min SpO2: above 93% |

| NIV | Face masks | CPAP or PEEP: 4 cm H2O Initial inspiratory pressure: 8–10 cm H2O SpO2: above 93% |

CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; FiO2, fraction of inhaled oxygen; HFNC, high-flow nasal cannula; NIV, noninvasive ventilation; NR, no record; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure; P/F, partial oxygen pressure/fraction of oxygen saturation; RR, respiratory rate; SpO2, peripheral arterial oxygen saturation.

Outcomes

The primary outcome is the number of deaths at day 28. The secondary outcomes are the occurrence of IMV, the number of deaths (no time-limited), length of ICU and hospital stay, ventilator-free days, and oxygenation index [partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2)/fraction of inhaled oxygen (FiO2)] at 24 h.

Statistical analysis

RevMan 5.4 computer software was used for all data analysis in this study. For all the dichotomous data that need to be analyzed, we chose to report odds ratio (OR). And for continuous variables, the mean and standard deviation (SD) should be reported. If the median and interquartile range (IQR) are reported in the study, it can be converted into the mean and SD through formulas.

RevMan 5.4 also reported the heterogeneity of the data while producing the forest plot. For heterogeneity test p < 0.05 or I 2 > 50%, we choose random-effects model. When the heterogeneity test p > 0.05 or I 2 < 50%, the fixed-effects model is often selected. The fixed-effects model is used when the results of heterogeneity between subgroups are consistent, and the random-effects model is used when the results of heterogeneity are inconsistent. If the heterogeneity test result I 2 > 80%, we need to perform a sensitivity analysis on the data to exclude studies with significant heterogeneity.

Results

The protocol for this review has been published in Prospero, and the registration number is CRD42021289413.

Literature search findings

We searched six databases with a total of 2778 studies (PubMed: 772, Embase: 693, Web of Science: 898, Scopus: 155, Cochrane: 238, WHO: 22). Two researchers used EndNote X9 to remove 499 duplicate studies and 5 editorial chapters. Since COVID-19 cases have been gradually reported from December 2019, our search time is defined as December 2019 until now, and 4 studies beyond the limitation have been removed. Three researchers (Y.W.H., N.L., and X.H.Z.) reviewed the titles and abstracts, and checked the full text of 241 studies. Finally, nine studies were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis. The search and screening process is shown in Figure 1.

Risk of bias assessment and study quality

Since only one RCT can be retrieved, the inclusion criteria of this study are not limited to prospective studies. We use the MINORS to evaluate the quality of NRCT based on the researches of Vinuela et al. 23 and Slim et al. 12 Each item can get 0–2 points, and we will include studies with scores ⩾12 points into the meta-analysis. The modified MINORS score of all eligible NRCT is shown in Table 1. For the only RCT, we assessed its risk of bias as described in the Cochrane handbook. Only performance bias is evaluated as high risk (Figure 2).

Study and patient characteristics

In nine studies, 1582 patients were included in the meta-analysis. The investigators extracted the characteristics of the patients in the included studies, containing groups, nationals, type of hospital, ages, gender, BMI, and comorbidity (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and coronary heart disease), in Table 2. In the study of Jarou et al., 19 the number of patients in the NIV group was less than 30. In the study of Kabak et al. 20 and Duan et al., 21 the number of patients in both groups was less than 30. The data of four studies are reported using median (IQR). During the meta-analysis process, we converted median (IQR) to mean (SD) according to the method proposed in Wan et al. 24

Intervention characteristics

The researchers extracted intervention characteristics of included studies; the main content are the oxygenation strategy and concomitant medications of the NIV and HFNC groups (Table 3). Only the study of Burnim et al. 18 did not show a specific oxygenation strategy, while the study of Kabak et al. 20 only proposed the use of non-rebreather masks and nasal cannula as a ventilation strategy for NIV. In three studies,14,17,20 the NIV group used a mask or nasal cannula for ventilation. Bonnet et al., 15 Sayan et al., 16 and Duan et al. 21 used masks for ventilation, and Jarou et al. 19 used nasal catheters. In particular, in the study of Grieco et al., 22 helmet ventilation was used for COVID-19 patients in the NIV group.

Meta-analysis and synthesis

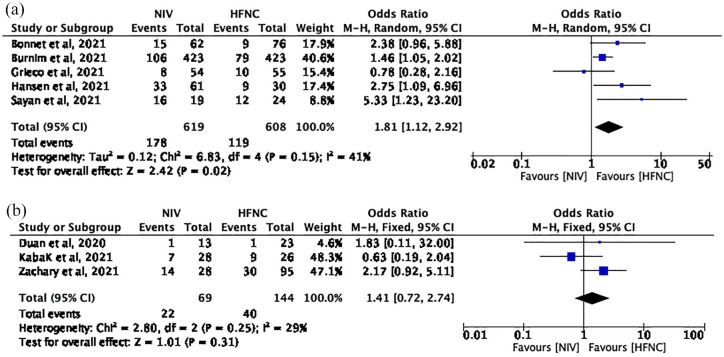

Number of deaths at day 28

Five studies with 1227 patients (NIV group: 619; HFNC group: 608) reported the number of deaths at day 28. The pooled mean difference (MD) (95% confidence interval, CI) was 1.62 (1.24, 2.14) units, I 2 = 41% (Figure 3(a)). Using a fixed-effects model, these results reached statistical significance (p = 0.0005) and favored HFNC group.

Figure 3.

(a) The number of deaths at day 28 and (b) the number of deaths (no time-limited).

Number of deaths (no time-limited)

Three studies with 213 patients (NIV group: 69; HFNC group: 144) reported the number of deaths. The pooled MD (95% CI) was 1.41 (0.72, 2.74) units, I2 = 29% (Figure 3(b)). Using a fixed-effects model, the result is not statistically significant (p = 0.31).

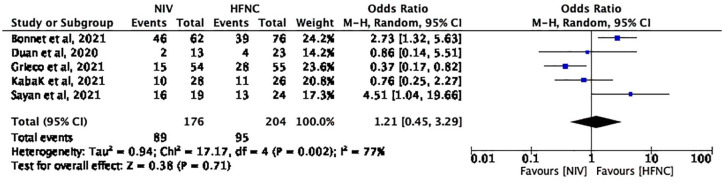

Occurrence of IMV

Five studies with 380 patients (NIV group: 176; HFNC group: 204) reported the occurrence of IMV. The pooled MD (95% CI) was 1.21 (0.45, 3.29) units, I2 = 77% (Figure 4). Using a random-effects model, the result is not statistically significant (p = 0.71).

Figure 4.

The occurrence of IMV.

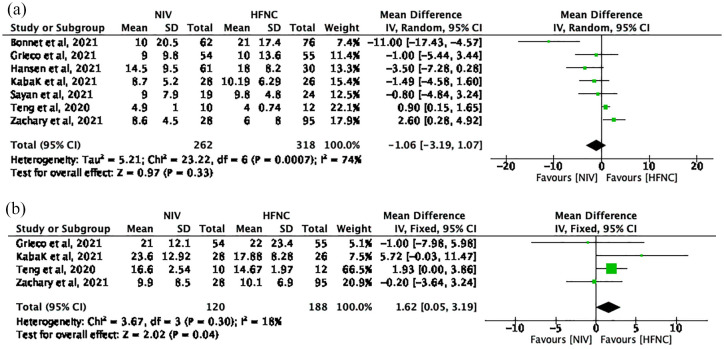

Length of ICU stay

Seven studies with 580 patients (NIV group: 262; HFNC group: 318) reported the length of ICU stay. The pooled MD (95% CI) was –1.06 (–3.19, 1.07) units, I2 = 74% (Figure 5(a)). Using a random-effects model, the result is not statistically significant (p = 0.33).

Figure 5.

(a) The length of ICU stay and (b) the length of hospital stay.

Length of hospital stay

Four studies with 308 patients (NIV group: 120; HFNC group: 188) reported the length of hospital stay. The pooled MD (95% CI) was 1.62 (0.05, 3.19) units, I2 = 18% (Figure 5(b)). Using a fixed-effects model, these results reached statistical significance (p = 0.04) and favored HFNC group.

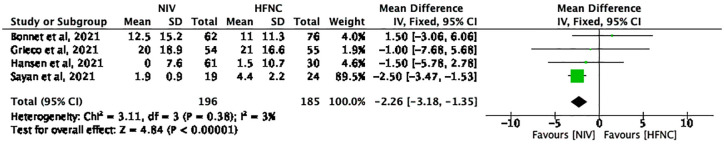

Ventilator-free days

Four studies with 381 patients (NIV group: 196; HFNC group: 185) reported the ventilator-free period (days). The pooled MD (95% CI) was –2.26 (–3.18, –1.35) units, I2 = 3% (Figure 6). Using a fixed-effects model, these results reached statistical significance (p < 0.00001) and favored NIV group.

Figure 6.

The ventilator-free days.

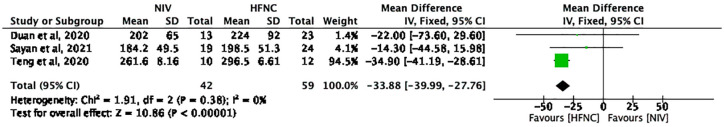

Oxygenation index (PaO2/FiO2) at 24 h

Three studies with 101 patients (NIV group: 42; HFNC group: 59) reported the oxygenation index (PaO2/FiO2) at 24 h. The pooled MD (95% CI) was –34.76 (–41.00, –28.51) units, I2 = 0% (Figure 7). Using a fixed-effects model, these results reached statistical significance (p < 0.00001) and favored HFNC group.

Figure 7.

The oxygenation index (PaO2/FiO2) at 24 h.

Discussion

Three years have passed since the outbreak of COVID-19, which has shown the world how frightening and aggressive it can be. Early epidemiological studies5,25,26 stated that 8.2% of cases suffer from rapid and progressive respiratory failure, similar to ARDS. In most severe cases, patients with COVID-19 require high probability of needing IMV, which is associated with high mortality. 4 Therefore, patients often need different degrees of noninvasive respiratory support treatment to maintain the arterial partial pressure of oxygen at a normal level. Our systematic review and meta-analysis yielded one RCT and eight high-quality NRCTs to evaluate the efficacy of different NIV strategies in the patients with COVID-19. By comparing the HFNC group with the NIV group, we found that the HFNC group was significantly better than NIV concerning the number of deaths at day 28, length of hospital stay, and oxygenation index at 24 h. The comparison between the HFNC and NIV groups was not statistically significant in terms of the incidence of IMV, number of deaths (no time-limited), and length of ICU stay. NIV group was superior only for the outcome of ventilator-free days.

How to improve patients’ survival rate, reduce the occurrence of IMV, and improve the prognosis of patients are the questions that always have been discussed since the outbreak of the COVID-19. Severe COVID-19 patients usually undergo ARF. Therefore, the use of various NIMV methods to maintain the patient’s FiO2 at a high level has become the global consensus.27,28 NIV is an oxygen therapy modality that emerged in the 1990s of the last world. 29 Esteban et al. 30 conducted a nested comparative study in 349 ICUs in 23 countries, and found out that NIV usage rate increased from 4% in 1998 to 11% in 2004. As NIV has long been in widespread clinical use, it has become the favorable option for ventilation support treatment of patients with COVID-19. 31 However, the shortcomings of NIV were also quickly exposed. An RCT carried out by Lemiale et al. 32 found out that early use of NIV did not reduce 28-day mortality in immunocompromised patients with ARF. With conventional equipment for NIV, oxygen flow is limited to no more than 15 l/min and FiO2 is often unstable, which make less effective than expected. 33 This is what made HFNC therapy received considerable attention when it was introduced in the 2000s as a respiratory support treatment for patients with severe respiratory failure. By providing a constant gas flow rate of up to 70 l/min, 34 HFNC can improve the ability to flush the dead space of the upper airway better than NIV and reduce the patient’s work of breathing.35,36 In a prospective study, Parke et al. 37 found that HFNC therapy could produce low levels of positive airway pressure, approximating the effect of PEEP. Despite the many advantages of HFNC as outlined above, there are two sides to the coin. Too much reliance on HFNC can lead to delayed intubation and increase mortality. 38 In the past 3 years, the shortage of ventilators following the outbreak of COVID-19 has led to a wider clinical use of this therapy. As you know, COVID-19 is transmitted mainly by respiratory droplets/aerosols. 39 The World Health Organization (WHO) 40 issued a guideline on 28 January 2020 recommending contact precautions for droplets from COVID-19 patients and warning against the routine use of HFNC or any potentially aerosol-generating methods. Hence, the adverse effects of HFNC therapy on intubation delays and the HFNC aerosol transmission remain important unresolved issues of high clinical relevance.

What bothers us most is the high mortality of COVID-19 patients. Both the NIV and HFNC have been demonstrated to significantly reduce mortality and enhance the prognosis of patients. Thus, we used the number of deaths at day 28 as the primary outcome of our meta-analysis. According to our analysis of five included studies, we can easily find a significant reduction in the number of deaths at day 28 in COVID-19 patients using HFNC as ventilation treatment [OR = 1.62, 95% CI = (1.24, 2.14), p = 0.0005]. In a large retrospective cohort study conducted by Burnim et al., 18 they concluded from an analysis of 423 cases in each of the HFNC and NIV groups that HFNC therapy was significantly associated with a reduced risk of the number of deaths at day 28 in a secondary analysis excluding COVID-19 patients who were intubated within 6 h of admission. This trend was most pronounced in patients with a PaO2/FiO2 ratio of less than 200. Sayan et al. 16 directly pointed out that administration of HFNC in respiratory failure secondary to COVID-19 pneumonia reduces short-term mortality compared with NIV (50% versus 84.2%; p < 0.019). In the article, Sayan et al. mentioned to a 2015 multicenter RCT designed by Frat et al. 41 to investigate the role of HFNC in patients with acute hypoxic respiratory failure. Frat draws his conclusion that HFNC significantly reduced mortality in patients with hypoxic respiratory failure in the ICU compared with NIV, especially in patients with PaO2/FiO2 ratio below 200. The study by Hansen et al. 17 reported that there was no statistically significant difference in short-term mortality between HFNC and NIV (30% versus 53.2%; p = 0.05). The retrospective study performed by Bonnet et al. 15 found out that mortality at day 28 did not significantly differ between HFNC group and NIV group (12% versus 24%; p = 0.17). Although two included retrospective articles concluded that HFNC was not statistically significant in reducing the number of deaths on day 28, interestingly, the authors of two articles were simultaneously discussing the statistical bias that was caused due to the small sample size included. Therefore, we cannot deny the effective role of HFNC in reducing short-term mortality in patients with COVID-19.

Investigating the effect of different NIV treatments on reducing the occurrence of IMV is also a necessary outcome of importance for patients with COVID-19. We included five studies to analyze which of HFNC and NIV was more meaningful to reduce the occurrence of IMV. Unfortunately, the results we made comparing HFNC with NIV were not statistically significant [OR = 1.21, 95% CI = (0.45, 3.29), p = 0.71]. This result is identical to a meta-analysis performed by Zhao et al. 9 in 2017, who investigated whether HFNC was superior to NIV in adult patients with ARF. Among the five studies, Bonnet et al. 15 drew his conclusion that HFNC for ARF due to COVID-19 is associated with a lower rate of IMV. In the NIV group, 46/62 (74%) of patients eventually received IMV while in the ICU, compared with 39/76 (51%) in the HFNC group (p = 0.007). Nevertheless, an RCT designed by Grieco et al. 22 revealed that the occurrence of IMV was significantly lower in the NIV group than in the HFNC group (30% versus 51%; p = 0.03). The inconsistent effect of different ventilation strategies on the occurrence of IMV in COVID-19 patients caused our analysis of this outcome to be not statistically significant. In the above article, we discussed the possible risk of aerosol transmission of the virus from HFNC. Although the risk is negligible, it may make health care professionals more cautious about treating patients with HFNC. The results are therefore skewed toward the HFNC group. What’s more, the relationship between prone position and HFNC has been previously documented,42,43 and the prone position was found to optimize the perceived benefits of HFNC. The irregular use of the awake prone position leads to a reduction in the validity of HFNC, which in turn leads to biased results.

Our study found that HFNC also has obvious advantages over NIV in terms of reducing the length of hospital stay [mean difference = 1.62, 95% CI = (0.05, 3.19), p = 0.04] and oxygenation index at 24 h [mean difference = –33.88, 95% CI = (–39.99, –27.76), p < 0.00001]. Oxygenation index (PaO2/FiO2) is the most used index to assess oxygenation and disease severity in patients with acute ARDS, with less than 200 mmHg elevating ARDS. 44 The fact that patients with COVID-19 in the HFNC group were able to increase their oxygenation index suggests that HFNC has a more significant effect on improving oxygenation and patient prognosis compared with NIV, whereas, in our meta-analysis, the comparison of HFNC with NIV was not statistically significant in terms of the length of ICU stay [mean difference = –1.06, 95% CI = (–3.19, 1.07), p = 0.33] and number of deaths (no time-limited) [OR = 1.41, 95% CI = (0.72, 2.74), p = 0.31]. More relevant studies are needed to explore those in the future.

Interestingly, the NIV group has a significant advantage over the HFNC only in the aspect of ventilator-free days [mean difference = –2.26, 95% CI = (–3.18, –1.35), p < 0.00001]. There was no significant difference between HFNC and NIV in terms of the occurrence of IMV, length of ICU stay, and the number of long-term deaths, both of which resulted in a corresponding reduction in intubation rates and improved long-term prognosis.

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to explore efficacy and value of these two types of oxygen strategies for patients with COVID-19. This study was created through an extensive search, iterative screening, and data extraction. We provide a comprehensive overview of the comparison between HFNC and NIV, with the aim of evaluating its true efficacy and benefit to patients by including thorough various assessment criteria. Meanwhile, we have taken into account the potential limitations of this meta-analysis. First, despite an extensive literature search, the limited number of relevant RCTs led to the inclusion of only one RCT and eight high-quality NRCTs. Although they passed the quality assessment, this may affect the accuracy of the results. Furthermore, COVID-19 patients in the eight included studies had different reasons for receiving ventilation therapy. Some of the studies included COVID-19 patients with ARF, and some have ARDS. Patients with different medical backgrounds receiving the same ventilation treatment may cause bias in the study outcomes. Finally, the timing of treatment as well as the pattern of treatment also vary between HFNC and NIV, which further increases heterogeneity.

Conclusion

For COVID-19 patients, the use of HFNC therapy is associated with the reduction of the number of deaths at day 28 and length of hospital stay, and can significantly improve oxygenation index (PaO2/FiO2) at 24 h. However, there was no favorable option in the comparison between the HFNC and NIV groups in the occurrence of IMV. NIV group was superior only for the outcome of ventilator-free days. Large samples and high-quality clinical studies are still needed to evaluate different ventilation strategies for patients with COVID-19.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tar-10.1177_17534666221087847 for High-flow nasal cannula versus noninvasive ventilation in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis by Yuewen He, Na Liu, Xuhui Zhuang, Xia Wang and Wuhua Ma in Therapeutic Advances in Respiratory Disease

Footnotes

Author contributions: Yuewen He: Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Writing – original draft.

Na Liu: Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology.

Xuhui Zhuang: Data curation; Investigation; Writing – original draft.

Xia Wang: Investigation; Methodology.

Wuhua Ma: Supervision; Writing – review & editing.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Wuhua Ma  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4078-5100

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4078-5100

Contributor Information

Yuewen He, Department of Anesthesiology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, Guangzhou, P.R. China.

Na Liu, Weihai Municipal Affiliated Hospital of Shandong University, Weihai, China.

Xuhui Zhuang, Department of Anesthesiology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, Guangzhou, P.R. China.

Xia Wang, Department of Anesthesiology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, Guangzhou, P.R. China.

Wuhua Ma, Department of Anesthesiology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, 12 Jichang Road, Guangzhou, Guangdong 510405, P.R. China.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. COVID-19 weekly epidemiological update, edition 62. Geneva: World Health Organization, 19 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Johansson MA, Quandelacy TM, Kada S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 transmission from people without COVID-19 symptoms. JAMA Netw Open 2021; 4: e2035057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gao Z, Xu Y, Sun C, et al. A systematic review of asymptomatic infections with COVID-19. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2021; 54: 12–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA 2020; 323: 1061–1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020; 395: 497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Oliveira J, Zagalo C, Cavaco-Silva P. Prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Rev Port Pneumol 2014; 20: 152–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Goligher EC, Ferguson ND, Brochard LJ. Clinical challenges in mechanical ventilation. Lancet 2016; 387: 1856–1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mas A, Masip J. Noninvasive ventilation in acute respiratory failure. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2014; 9: 837–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhao H, Wang H, Sun F, et al. High-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy is superior to conventional oxygen therapy but not to noninvasive mechanical ventilation on intubation rate: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care 2017; 21: 184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nishimura M. High-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy in adults: physiological benefits, indication, clinical benefits, and adverse effects. Respir Care 2016; 61: 529–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rochwerg B, Einav S, Chaudhuri D, et al. The role for high flow nasal cannula as a respiratory support strategy in adults: a clinical practice guideline. Intensive Care Med 2020; 46: 2226–2237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, et al. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J Surg 2003; 73: 712–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zeng X, Zhang Y, Kwong JS, et al. The methodological quality assessment tools for preclinical and clinical studies, systematic review and meta-analysis, and clinical practice guideline: a systematic review. J Evid Based Med 2015; 8: 2–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Teng XB, Shen Y, Han MF, et al. The value of high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy in treating novel coronavirus pneumonia. Eur J Clin Invest 2021; 51: e13435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bonnet N, Martin O, Boubaya M, et al. High flow nasal oxygen therapy to avoid invasive mechanical ventilation in SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia: a retrospective study. Ann Intensive Care 2021; 11: 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sayan İ, Altınay M, Çınar AS, et al. Impact of HFNC application on mortality and intensive care length of stay in acute respiratory failure secondary to COVID-19 pneumonia. Heart Lung 2021; 50: 425–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hansen CK, Stempek S, Liesching T, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients receiving high flow nasal cannula therapy prior to mechanical ventilation in COVID-19 respiratory failure: a prospective observational study. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci 2021; 11: 56–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Burnim MS, Wang K, Checkley W, et al. The effectiveness of high-flow nasal cannula in coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia: a retrospective cohort study. Crit Care Med 2022; 50: e253–e262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jarou ZJ, Beiser DG, Sharp WW, et al. Emergency department-initiated high-flow nasal cannula for COVID-19 respiratory distress. West J Emerg Med 2021; 22: 979–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kabak M, Çil B. Feasibility of non-rebreather masks and nasal cannula as a substitute for high flow nasal oxygen in patients with severe COVID-19 infection. Acta Medica Mediterr 2021; 37: 949–954. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Duan J, Chen B, Liu X, et al. Use of high-flow nasal cannula and noninvasive ventilation in patients with COVID-19: a multicenter observational study. Am J Emerg Med 2021; 46: 276–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Grieco DL, Menga LS, Cesarano M, et al. Effect of helmet noninvasive ventilation vs high-flow nasal oxygen on days free of respiratory support in patients with COVID-19 and moderate to severe hypoxemic respiratory failure: the HENIVOT randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2021; 325: 1731–1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vinuela EF, Gonen M, Brennan MF, et al. Laparoscopic versus open distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and high-quality nonrandomized studies. Ann Surg 2012; 255: 446–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, et al. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014; 14: 135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Torres-Castro R, Vasconcello-Castillo L, Alsina-Restoy X, et al. Respiratory function in patients post-infection by COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pulmonology 2021; 27: 328–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ñamendys-Silva SA. ECMO for ARDS due to COVID-19. Heart Lung 2020; 49: 348–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cinesi Gómez C, Peñuelas Rodríguez Ó, Luján Torné M, et al. Clinical consensus recommendations regarding non-invasive respiratory support in the adult patient with acute respiratory failure secondary to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Med Intensiva (Engl Ed) 2020; 44: 429–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pfeifer M, Ewig S, Voshaar T, et al. [Position paper for the state of the art application of respiratory support in patients with COVID-19 – German Respiratory Society]. Pneumologie 2020; 74: 337–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hillberg RE, Johnson DC. Noninvasive ventilation. N Engl J Med 1997; 337: 1746–1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Esteban A, Ferguson ND, Meade MO, et al. Evolution of mechanical ventilation in response to clinical research. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008; 177: 170–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Winck JC, Ambrosino N. COVID-19 pandemic and non invasive respiratory management: every Goliath needs a David. An evidence based evaluation of problems. Pulmonology 2020; 26: 213–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lemiale V, Mokart D, Resche-Rigon M, et al. Effect of noninvasive ventilation vs oxygen therapy on mortality among immunocompromised patients with acute respiratory failure: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015; 314: 1711–1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lee CC, Mankodi D, Shaharyar S, et al. High flow nasal cannula versus conventional oxygen therapy and non-invasive ventilation in adults with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure: a systematic review. Respir Med 2016; 121: 100–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gotera C, Díaz Lobato S, Pinto T, et al. Clinical evidence on high flow oxygen therapy and active humidification in adults. Rev Port Pneumol 2013; 19: 217–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Möller W, Celik G, Feng S, et al. Nasal high flow clears anatomical dead space in upper airway models. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2015; 118: 1525–1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Möller W, Feng S, Domanski U, et al. Nasal high flow reduces dead space. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2017; 122: 191–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Parke R, McGuinness S, Eccleston M. Nasal high-flow therapy delivers low level positive airway pressure. Br J Anaesth 2009; 103: 886–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kang BJ, Koh Y, Lim CM, et al. Failure of high-flow nasal cannula therapy may delay intubation and increase mortality. Intensive Care Med 2015; 41: 623–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wiersinga WJ, Rhodes A, Cheng AC, et al. Pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA 2020; 324: 782–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. World Health Organization. Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infection is suspected: interim guidance. Geneva: World Health Organization, 28 January 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Frat JP, Thille AW, Mercat A, et al. High-flow oxygen through nasal cannula in acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 2185–2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Coppo A, Bellani G, Winterton D, et al. Feasibility and physiological effects of prone positioning in non-intubated patients with acute respiratory failure due to COVID-19 (PRON-COVID): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med 2020; 8: 765–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ding L, Wang L, Ma W, et al. Efficacy and safety of early prone positioning combined with HFNC or NIV in moderate to severe ARDS: a multi-center prospective cohort study. Crit Care 2020; 24: 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Villar J, Blanco J, del Campo R, et al. Assessment of PaO2/FiO2 for stratification of patients with moderate and severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. BMJ Open 2015; 5: e006812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tar-10.1177_17534666221087847 for High-flow nasal cannula versus noninvasive ventilation in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis by Yuewen He, Na Liu, Xuhui Zhuang, Xia Wang and Wuhua Ma in Therapeutic Advances in Respiratory Disease